John Disbrowe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John DesboroughAlso spelt John Disbrowe and John Desborow (the latter in the

He avoided all participation in the trial of

He avoided all participation in the trial of

Indemnity and Oblivion Act

The Indemnity and Oblivion Act 1660 ( 12 Cha. 2. c. 11) was an act of the Parliament of England, the long title of which is "An Act of Free and Generall Pardon, Indemnity, and Oblivion". This act was a general pardon for everyone who had com ...

, section XLIII) (1608–1680) was an English soldier and politician who supported the parliamentary cause during the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

.

Life

He was the son of James Desborough ofEltisley

Eltisley is a village and civil parish in South Cambridgeshire, England, on the A428 road about east of St Neots and about west of the city of Cambridge. The population in 2001 was 421 people, falling slightly to 401 at the 2011 Census.

Hist ...

, Cambridgeshire

Cambridgeshire (abbreviated Cambs.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England and East Anglia. It is bordered by Lincolnshire to the north, Norfolk to the north-east, Suffolk to the east, Essex and Hertfor ...

, and of Elizabeth Hatley of Over

Over may refer to:

Places

*Over, Cambridgeshire, England

* Over, Cheshire, England

**Over Bridge

* Over, South Gloucestershire, Gloucestershire, England

* Over, Tewkesbury, Gloucestershire, England

* Over, Seevetal, Germany

Music

Albums

* ''Ov ...

in the same county. He was baptized on 13 November 1608. He was educated in law. On 23 June 1636 he married Jane, daughter of Robert Cromwell of Huntingdon

Huntingdon is a market town in the Huntingdonshire district of Cambridgeshire, England. The town was given its town charter by John, King of England, King John in 1205. It was the county town of the historic county of Huntingdonshire. Oliver C ...

and sister of Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

– the future Lord Protector

Lord Protector (plural: ''Lords Protector'') is a title that has been used in British constitutional law for the head of state. It was also a particular title for the British heads of state in respect to the established church. It was sometime ...

, at Eltisley.

He took an active part in the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

, and showed considerable military ability. In 1645, he was present as major in the engagement at Langport on 10 July, at Hambleton Hill on 4 August, and on 10 September he commanded the horse at the Storming of Bristol

The Storming of Bristol took place from 23 to 26 July 1643, during the First English Civil War. The Royalist army under Prince Rupert captured the important port of Bristol from its weakened Parliamentarian garrison. The city remained under ...

. Later he took part in the operations round Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

. In 1648, as colonel he commanded the forces at Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth ( ), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside resort, seaside town which gives its name to the wider Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. Its fishing industry, m ...

.

He avoided all participation in the trial of

He avoided all participation in the trial of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

in June 1649, being employed in the settlement of the west of England. He fought at Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engl ...

as major-general and nearly captured Charles II near Salisbury

Salisbury ( , ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and civil parish in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers River Avon, Hampshire, Avon, River Nadder, Nadder and River Bourne, Wi ...

.

After the establishment of the Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth of England was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when Kingdom of England, England and Wales, later along with Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland and Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, were governed as a republi ...

he was chosen, on 7 January 1652, a member of the committee for legal reforms. In 1653, he became a member of the Protectorate

The Protectorate, officially the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, was the English form of government lasting from 16 December 1653 to 25 May 1659, under which the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotl ...

council of state, and a commissioner of the treasury, and was appointed one of the four Generals at Sea and a commissioner for the army and navy. In 1654, he was made constable of St Briavel's Castle

St Briavels Castle (most likely named after Saint Brioc) is a moated Norman castle at St Briavels in the English county of Gloucestershire. The castle is noted for its huge Edwardian gatehouse that guards the entrance.

St Briavels Castle was or ...

in Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( , ; abbreviated Glos.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Herefordshire to the north-west, Worcestershire to the north, Warwickshire to the north-east, Oxfordshire ...

. During the Rule of the Major-Generals

The Rule of the Major-Generals, was a period of direct military government from August 1655 to January 1657, during Oliver Cromwell's Protectorate. England and Wales were divided into ten regions, each governed by a major-general who answered to ...

(1655–1656) he was appointed major-general over the south west. He had been nominated a member of the Barebones Parliament

Barebone's Parliament, also known as the Little Parliament, the Nominated Assembly and the Parliament of Saints, came into being on 4 July 1653, and was the last attempt of the English Commonwealth to find a stable political form before the inst ...

in 1653, and he was returned to the First Protectorate Parliament

The First Protectorate Parliament was summoned by the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell under the terms of the Instrument of Government. It sat for one term from 3 September 1654 until 22 January 1655 with William Lenthall as the Speaker of the H ...

of 1654 for Cambridgeshire, and to the Second Protectorate Parliament

The Second Protectorate Parliament in England sat for two sessions from 17 September 1656 until 4 February 1658, with Thomas Widdrington as the Speaker of the House of Commons (United Kingdom), Speaker of the House of Commons. In its first sess ...

in 1656 for Somerset

Somerset ( , ), Archaism, archaically Somersetshire ( , , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel, Gloucestershire, and Bristol to the north, Wiltshire to the east ...

shire. In the Second Parliament, he introduced the "Militia Bill" which was voted down by one hundred and twenty four votes to eighty eight. If passed it would have helped to finance the Army by imposing a ten per cent "Decimation Tax", on known Royalists.

In July 1657, he became a member of the Protector's Privy Council

The English Council of State, later also known as the Protector's Privy Council, was first appointed by the Rump Parliament on 14 February 1649 after the execution of King Charles I.

Charles's execution on 30 January was delayed for several hou ...

, and in 1658 he accepted a seat in Cromwell's Other House (House of Lords).

In spite of his near relationship to the Protectors family, he was one of the most violent opponents of the assumption by Cromwell of the royal title, and after the Protector's death, instead of supporting the interests and government of his nephew Richard Cromwell

Richard Cromwell (4 October 162612 July 1712) was an English statesman who served as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland from 1658 to 1659. He was the son of Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell.

Following his father ...

, he was, with Charles Fleetwood

Charles Fleetwood ( 1618 – 4 October 1692) was an English lawyer from Northamptonshire, who served with the Parliamentarian army during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A close associate of Oliver Cromwell, to whom he was related by marriage ...

, the chief instigator and organizer of the hostility of the army towards his administration, and forced Richard Cromwell by threats and menaces to dissolve his Third Protectorate Parliament

The Third Protectorate Parliament sat for one session, from 27 January 1659 until 22 April 1659, with Chaloner Chute and Thomas Bampfylde as the Speakers of the House of Commons. It was a bicameral Parliament, with an Upper House having a po ...

in April 1659. Desborough was chosen a member of the Council of State

A council of state is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head ...

by the restored Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament describes the members of the Long Parliament who remained in session after Colonel Thomas Pride, on 6 December 1648, commanded his soldiers to Pride's Purge, purge the House of Commons of those Members of Parliament, members ...

, and made colonel and governor of Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

, but presenting with other officers a seditious petition from the Army Council, on 5 October 1659, was about a week later dismissed. After the exclusion of the Rump Parliament from the Palace of Westminster by Fleetwood on 13 October, he was chosen by the officers a member of the new administration and commissary-general of the horse.

The new military government, however, rested on no solid foundation, and its leaders quickly found themselves without any influence. Desborough himself became an object of ridicule, his regiment even revolted against him, and on the return of the Rump he was ordered to quit London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

. At the Restoration he was excluded from the 1660 Indemnity and Oblivion Act

The Indemnity and Oblivion Act 1660 ( 12 Cha. 2. c. 11) was an act of the Parliament of England, the long title of which is "An Act of Free and Generall Pardon, Indemnity, and Oblivion". This act was a general pardon for everyone who had com ...

but not included in the clause of pains and penalties extending to life and goods, being therefore only incapacitated from public employment. Soon afterwards he was arrested on suspicion of conspiring to kill the king and queen, but was quickly liberated. Subsequently, he escaped to the Netherlands, where he engaged in republican intrigues. Accordingly, he was ordered home, in April 1666, on pain of incurring the charge of treason, and obeying was imprisoned in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

until February 1667, when he was examined before the council and set free.

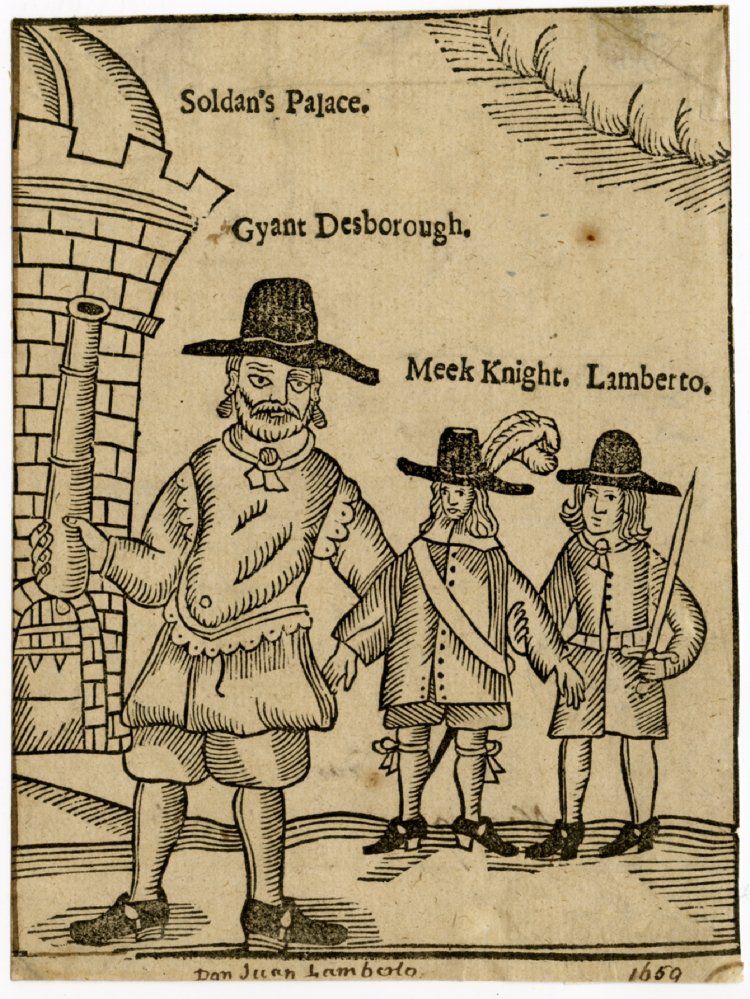

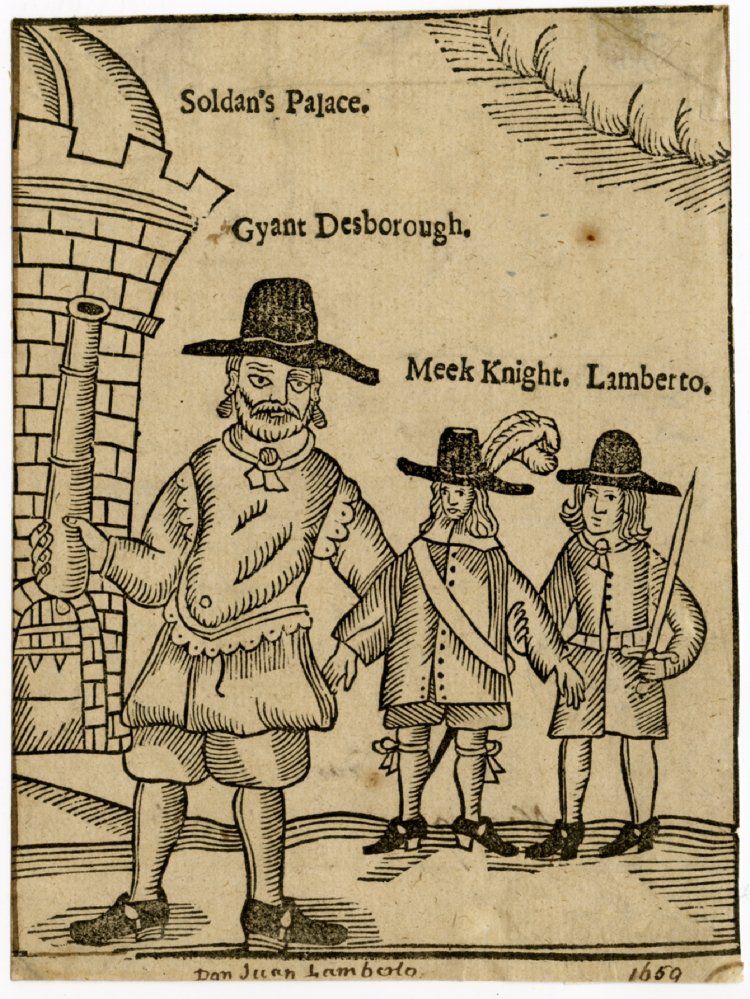

Desborough died in 1680. By his first wife, Cromwell's sister, he had one daughter and seven sons; he married a second wife in April 1658 whose name is unrecorded. Desborough was a good soldier and nothing more; and his only conception of government was by force and by the army. His rough person and manners are the constant theme of ridicule in the royalist ballads, and he is caricatured by Samuel Butler in ''Hudibras

''Hudibras'' () is a vigorous satirical poem, written in a mock-heroic style by Samuel Butler (1613–1680), and published in three parts in 1663, 1664 and 1678. The action is set in the last years of the Interregnum, around 1658–60, immediate ...

'' and in the ''Parable of the Lion and the Fox''.

Notes

References

Attribution: *Further reading

{{DEFAULTSORT:Desborough, John 1608 births 1680 deaths New Model Army generals English MPs 1653 (Barebones) English MPs 1654–1655 English MPs 1656–1658 Prisoners in the Tower of London People from South Cambridgeshire District Members of the Parliament of England (pre-1707) for Totnes Parliamentarian military personnel of the English Civil War Lords of the Admiralty Military personnel from Cambridgeshire Cromwell family Members of Cromwell's Other House