John Couch Adams on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Couch Adams ( ; 5 June 1819 – 21 January 1892) was a British mathematician and

Adams was born at Lidcot, a farm at Laneast, near

Adams was born at Lidcot, a farm at Laneast, near

Ten years later,

Ten years later,

link on this page

* * * * non.(1891–92) ''Journal of the British Astronomical Association'' 2: 196–197

''Lectures on the Lunar Theory''

London: Cambridge University Press *A collection, virtually complete, of Adams's papers regarding the discovery of Neptune was presented by Mrs Adams to the library of St John's College, see: Sampson (1904), and also: **"The collected papers of Prof. Adams", ''Journal of the British Astronomical Association'', 7 (1896–97) **''Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society'', 53 184; **''Observatory'', 15 174; **''

Biography on the St Andrews database

* * * * * Davor Krajnovic

John Couch Adams: mathematical astronomer, college friend of George Gabriel Stokes and promotor of women in astronomy

{{DEFAULTSORT:Adams, John Couch 1819 births 1892 deaths People from Launceston, Cornwall Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge 19th-century British astronomers 19th-century English mathematicians Lowndean Professors of Astronomy and Geometry Fellows of the Royal Society Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Neptune Scientists from Cornwall Recipients of the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society Recipients of the Copley Medal Senior Wranglers Methodist Church of Great Britain people Cornish Methodists 19th-century Methodists Honorary Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Academics of the University of St Andrews Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Presidents of the Royal Astronomical Society Members of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities Presidents of the Cambridge Philosophical Society

astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. Astronomers observe astronomical objects, such as stars, planets, natural satellite, moons, comets and galaxy, galax ...

. He was born in Laneast, near Launceston, Cornwall

Launceston ( , ; rarely spelled Lanson as a local abbreviation; ) is a town, ancient borough, and civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is west of the middle stage of the River Tamar, which constitutes almost the entire borde ...

, and died in Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

.

His most famous achievement was predicting the existence and position of Neptune

Neptune is the eighth and farthest known planet from the Sun. It is the List of Solar System objects by size, fourth-largest planet in the Solar System by diameter, the third-most-massive planet, and the densest giant planet. It is 17 t ...

, using only mathematics. The calculations were made to explain discrepancies with Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. It is a gaseous cyan-coloured ice giant. Most of the planet is made of water, ammonia, and methane in a Supercritical fluid, supercritical phase of matter, which astronomy calls "ice" or Volatile ( ...

's orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an ...

and the laws

Law is a set of rules that are created and are law enforcement, enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a Socia ...

of Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws of p ...

and Newton. At the same time, but unknown to each other, the same calculations were made by Urbain Le Verrier

Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier (; 11 March 1811 – 23 September 1877) was a French astronomer and mathematician who specialized in celestial mechanics and is best known for predicting the existence and position of Neptune using only mathematics. ...

. Le Verrier would send his coordinates to Berlin Observatory astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle, who confirmed the existence of the planet

A planet is a large, Hydrostatic equilibrium, rounded Astronomical object, astronomical body that is generally required to be in orbit around a star, stellar remnant, or brown dwarf, and is not one itself. The Solar System has eight planets b ...

on 23 September 1846, finding it within 1° of Le Verrier's predicted location. (There was, and to some extent still is, some controversy over the apportionment of credit for the discovery; see Discovery of Neptune.) Later, Adams explained the origin of meteor showers

A meteor shower is a celestial event in which a number of meteors are observed to radiate, or originate, from one point in the night sky. These meteors are caused by streams of cosmic debris called meteoroids entering Earth's atmosphere at extr ...

, which holds to the present day.

Adams was Lowndean Professor in the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

from 1859 until his death. He won the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

The Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society is the highest award given by the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS). The RAS Council have "complete freedom as to the grounds on which it is awarded" and it can be awarded for any reason. Past awar ...

in 1866. In 1884, he attended the International Meridian Conference

The International Meridian Conference was a conference held in October 1884 in Washington, D.C., in the United States, to determine a prime meridian for international use. The conference was held at the request of President of the United State ...

as a delegate for Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

.

A crater on the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). The Moon rotation, rotates, with a rotation period (lunar ...

is jointly named after him, Walter Sydney Adams and Charles Hitchcock Adams. Neptune's outermost known ring and the asteroid

An asteroid is a minor planet—an object larger than a meteoroid that is neither a planet nor an identified comet—that orbits within the Solar System#Inner Solar System, inner Solar System or is co-orbital with Jupiter (Trojan asteroids). As ...

1996 Adams are also named after him. The Adams Prize, presented by the University of Cambridge, commemorates his prediction of the position of Neptune. His personal library is held at Cambridge University Library.

Early life

Adams was born at Lidcot, a farm at Laneast, near

Adams was born at Lidcot, a farm at Laneast, near Launceston, Cornwall

Launceston ( , ; rarely spelled Lanson as a local abbreviation; ) is a town, ancient borough, and civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is west of the middle stage of the River Tamar, which constitutes almost the entire borde ...

, the eldest of seven children. His parents were Thomas Adams (1788–1859), a poor tenant farmer

A tenant farmer is a farmer or farmworker who resides and works on land owned by a landlord, while tenant farming is an agricultural production system in which landowners contribute their land and often a measure of operating capital and ma ...

, and his wife, Tabitha Knill Grylls (1796–1866). The family were devout Wesleyans who enjoyed music and among John's brothers, Thomas became a missionary, George a farmer, and William Grylls Adams, professor of natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

and astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

at King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV ...

. Tabitha was a farmer's daughter but had received a rudimentary education from John Couch, her uncle, whose small library she had inherited. John was intrigued by the astronomy books from an early age.

John attended the Laneast village school where he acquired some Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

and algebra

Algebra is a branch of mathematics that deals with abstract systems, known as algebraic structures, and the manipulation of expressions within those systems. It is a generalization of arithmetic that introduces variables and algebraic ope ...

. From there, he went, at the age of twelve, to Devonport, where his mother's cousin, the Rev. John Couch Grylls, kept a private school. There he learned classics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

but was largely self-taught in mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, studying in the Library of Devonport Mechanics' Institute and reading '' Rees's Cyclopædia'' and Samuel Vince's ''Fluxions''. He observed Halley's comet

Halley's Comet is the only known List of periodic comets, short-period comet that is consistently visible to the naked eye from Earth, appearing every 72–80 years, though with the majority of recorded apparitions (25 of 30) occurring after ...

in 1835 from Landulph and the following year started to make his own astronomical calculations, predictions and observations, engaging in private tutoring to finance his activities.

In 1836, his mother inherited a small estate at Badharlick and his promise as a mathematician induced his parents to send him to the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

. In October 1839 he entered as a sizar

At Trinity College Dublin and the University of Cambridge, a sizar is an Undergraduate education, undergraduate who receives some form of assistance such as meals, lower fees or lodging during his or her period of study, in some cases in retur ...

at St John's College, graduating B.A. in 1843 as senior wrangler and first Smith's prize

Smith's Prize was the name of each of two prizes awarded annually to two research students in mathematics and theoretical physics at the University of Cambridge from 1769. Following the reorganization in 1998, they are now awarded under the names ...

winner of his year.

Discovery of Neptune

In 1821, Alexis Bouvard had published astronomical tables of theorbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an ...

of Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. It is a gaseous cyan-coloured ice giant. Most of the planet is made of water, ammonia, and methane in a Supercritical fluid, supercritical phase of matter, which astronomy calls "ice" or Volatile ( ...

, making predictions of future positions based on Newton's laws of motion

Newton's laws of motion are three physical laws that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws, which provide the basis for Newtonian mechanics, can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body re ...

and gravitation

In physics, gravity (), also known as gravitation or a gravitational interaction, is a fundamental interaction, a mutual attraction between all massive particles. On Earth, gravity takes a slightly different meaning: the observed force b ...

. Subsequent observations revealed substantial deviations from the tables, leading Bouvard to hypothesise some perturbing body. Adams learnt of the irregularities while still an undergraduate and became convinced of the "perturbation" theory. Adams believed, in the face of anything that had been attempted before, that he could use the observed data on Uranus, and utilising nothing more than Newton's law of gravitation, deduce the mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

, position and orbit of the perturbing body. On 3 July 1841, he noted his intention to work on the problem.

After his final examination

An examination (exam or evaluation) or test is an educational assessment intended to measure a test-taker's knowledge, skill, aptitude, physical fitness, or classification in many other topics (e.g., beliefs). A test may be administered verba ...

s in 1843, Adams was elected fellow

A fellow is a title and form of address for distinguished, learned, or skilled individuals in academia, medicine, research, and industry. The exact meaning of the term differs in each field. In learned society, learned or professional society, p ...

of his college and spent the summer vacation in Cornwall calculating the first of six iterations. While he worked on the problem back in Cambridge, he tutored undergraduates, sending money home to educate his brothers, and even taught his bed maker to read.

Apparently, Adams communicated his work to James Challis, director of the Cambridge Observatory, in mid-September 1845, but there is some controversy as to how. On 21 October 1845, Adams, returning from a Cornwall vacation, without appointment, twice called on Astronomer Royal

Astronomer Royal is a senior post in the Royal Households of the United Kingdom. There are two officers, the senior being the astronomer royal dating from 22 June 1675; the junior is the astronomer royal for Scotland dating from 1834. The Astro ...

George Biddell Airy

Sir George Biddell Airy (; 27 July 18012 January 1892) was an English mathematician and astronomer, as well as the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics from 1826 to 1828 and the seventh Astronomer Royal from 1835 to 1881. His many achievements inc ...

in Greenwich

Greenwich ( , , ) is an List of areas of London, area in south-east London, England, within the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Greater London, east-south-east of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime hi ...

. Failing to find him at home, Adams reputedly left a manuscript of his solution, again without the detailed calculations. Airy responded with a letter to Adams asking for some clarification.

It appears that Adams did not regard the question as "trivial", as is often alleged, but he failed to complete a response. Various theories have been discussed as to Adams's failure to reply, such as his general nervousness, procrastination and disorganisation.

Meanwhile, Urbain Le Verrier

Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier (; 11 March 1811 – 23 September 1877) was a French astronomer and mathematician who specialized in celestial mechanics and is best known for predicting the existence and position of Neptune using only mathematics. ...

, on 10 November 1845, presented to the '' Académie des sciences'' in Paris a memoir on Uranus, showing that the preexisting theory failed to account for its motion. On reading Le Verrier's memoir, Airy was struck by the coincidence and initiated a desperate race for English priority in discovery of the planet. The search was begun by a laborious method on 29 July. Only after the discovery of Neptune on 23 September 1846 had been announced in Paris did it become apparent that Neptune had been observed on 8 and 12 August but because Challis lacked an up-to-date star-map it was not recognized as a planet.

A keen controversy arose in France and England as to the merits of the two astronomers. As the facts became known, there was wide recognition that the two astronomers had independently solved the problem of Uranus, and each was ascribed equal importance. However, there have been subsequent assertions that "The Brits Stole Neptune" and that Adams's British contemporaries retrospectively ascribed him more credit than he was due. But it is also notable (and not included in some of the foregoing discussion references) that Adams himself publicly acknowledged Le Verrier's priority and credit (not forgetting to mention the role of Galle) in the paper that he gave 'On the Perturbations of Uranus' to the Royal Astronomical Society in November 1846:

Adams held no bitterness towards Challis or Airy and acknowledged his own failure to convince the astronomical world:

Work style

His lay fellowship at St John's College came to an end in 1852, and the existing statutes did not permit his re-election. However, Pembroke College, which possessed greater freedom, elected him in the following year to a lay fellowship which he held for the rest of his life. Despite the fame of his work on Neptune, Adams also did much important work on gravitational astronomy and terrestrial magnetism. He was particularly adept at fine numerical calculations, often making substantial revisions to the contributions of his predecessors. However, he was "extraordinarily uncompetitive, reluctant to publish imperfect work to stimulate debate or claim priority, averse to correspondence about it, and forgetful in practical matters". It has been suggested that these aresymptom

Signs and symptoms are diagnostic indications of an illness, injury, or condition.

Signs are objective and externally observable; symptoms are a person's reported subjective experiences.

A sign for example may be a higher or lower temperature ...

s of Asperger syndrome

Asperger syndrome (AS), also known as Asperger's syndrome or Asperger's, is a diagnostic label that has historically been used to describe a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by significant difficulties in social interaction and no ...

which would also be consistent with the "repetitive behaviours and restricted interests" necessary to perform the Neptune calculations, in addition to his difficulties in personal interaction with Challis and Airy.

In 1852, he published new and accurate tables of the Moon's parallax

Parallax is a displacement or difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different sightline, lines of sight and is measured by the angle or half-angle of inclination between those two lines. Due to perspective (graphica ...

, which superseded Johann Karl Burckhardt's, and supplied corrections to the theories of Marie-Charles Damoiseau, Giovanni Antonio Amedeo Plana, and Philippe Gustave Doulcet.

He had hoped that this work would leverage him into the vacant post as superintendent of HM Nautical Almanac Office but John Russell Hind was preferred, Adams lacking the necessary ability as an organiser and administrator.

Lunar theory – Secular acceleration of the Moon

Since ancient times, theMoon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). The Moon rotation, rotates, with a rotation period (lunar ...

's mean rate of motion relative to the stars had been treated as being constant, but in 1695, Edmond Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, Hal ...

had suggested that this mean rate was gradually increasing. Later, during the eighteenth century, Richard Dunthorne estimated the rate as +10" (arcseconds/century2) in terms of the resulting difference in lunar longitude, an effect that became known as the ''secular acceleration of the Moon''. Pierre-Simon Laplace

Pierre-Simon, Marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French polymath, a scholar whose work has been instrumental in the fields of physics, astronomy, mathematics, engineering, statistics, and philosophy. He summariz ...

had given an explanation

An explanation is a set of statements usually constructed to describe a set of facts that clarifies the causes, context, and consequences of those facts. It may establish rules or laws, and clarifies the existing rules or laws in relation ...

in 1787 in terms of changes in the eccentricity of the Earth's orbit. He considered only the radial gravitational force on the Moon from the Sun

The Sun is the star at the centre of the Solar System. It is a massive, nearly perfect sphere of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core, radiating the energy from its surface mainly as visible light a ...

and Earth but obtained close agreement with the historical record of observations.

In 1820, at the insistence of the '' Académie des sciences'', Damoiseau, Plana and Francesco Carlini revisited Laplace's work, investigating quadratic and higher-order perturbing terms, and obtained similar results, again addressing only a radial, and neglecting tangential, gravitational force on the Moon. Hansen obtained similar results in 1842 and 1847.

In 1853, Adams published a paper showing that, while tangential terms vanish in the first-order theory of Laplace, they become substantial when quadratic terms are admitted. Small terms integrated in time come to have large effects and Adams concluded that Plana had overestimated the secular acceleration by approximately 1.66" per century.

At first, Le Verrier rejected Adams's results. In 1856, Plana admitted Adams's conclusions, claiming to have revised his own analysis and arrived at the same results. However, he soon recanted, publishing a third result different both from Adams's and Plana's own earlier work. Delaunay in 1859 calculated the fourth-order term and duplicated Adams's result leading Adams to publish his own calculations for the fifth, sixth and seventh-order terms. Adams now calculated that only 5.7" of the observed 11" was accounted for by gravitational effects. Later that year, Philippe Gustave Doulcet, Comte de Pontécoulant published a claim that the tangential force could have no effect though Peter Andreas Hansen, who seems to have cast himself in the role of arbitrator, declared that the burden of proof rested on Pontécoulant, while lamenting the need to discover a further effect to account for the balance. Much of the controversy centred around the convergence

Convergence may refer to:

Arts and media Literature

*''Convergence'' (book series), edited by Ruth Nanda Anshen

*Convergence (comics), "Convergence" (comics), two separate story lines published by DC Comics:

**A four-part crossover storyline that ...

of the power series expansion used and, in 1860, Adams duplicated his results without using a power series. Sir John Lubbock also duplicated Adams's results and Plana finally concurred. Adams's view was ultimately accepted and further developed, winning him the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

The Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society is the highest award given by the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS). The RAS Council have "complete freedom as to the grounds on which it is awarded" and it can be awarded for any reason. Past awar ...

in 1866. The unexplained drift is now known to be due to tidal acceleration

Tidal acceleration is an effect of the tidal forces between an orbiting natural satellite (e.g. the Moon) and the primary planet that it orbits (e.g. Earth). The acceleration causes a gradual recession of a satellite in a prograde orbit (satel ...

.

In 1858 Adams became professor of mathematics at the University of St Andrews

The University of St Andrews (, ; abbreviated as St And in post-nominals) is a public university in St Andrews, Scotland. It is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, oldest of the four ancient universities of Scotland and, f ...

, but lectured only for a session, before returning to Cambridge for the Lowndean professorship of astronomy and geometry. Two years later he succeeded Challis as director of the Cambridge Observatory, a post Adams held until his death.

Leonids

The greatmeteor shower

A meteor shower is a celestial event in which a number of meteors are observed to radiate, or originate, from one point in the night sky. These meteors are caused by streams of cosmic debris called meteoroids entering Earth's atmosphere at ext ...

of November 1866 turned his attention to the Leonids

The Leonids ( ) are a prolific annual meteor shower associated with the comet 55P/Tempel–Tuttle, Tempel–Tuttle, and are also known for their spectacular meteor storms that occur about every 33 years. The Leonids get their name from the loca ...

, whose probable path and period had already been discussed and predicted by Hubert Anson Newton

Hubert Anson Newton FRS HFRSE (19 March 1830 – 12 August 1896), usually cited as H. A. Newton, was an American astronomer and mathematician, noted for his research on meteors.

Biography

Newton was born at Sherburne, New York, and graduated ...

in 1864. Newton had asserted that the longitude of the ascending node, that marked where the shower would occur, was increasing and the problem of explaining this variation attracted some of Europe's leading astronomers.

Using a powerful and elaborate analysis, Adams ascertained that this cluster of meteors, which belongs to the Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Sola ...

, traverses an elongated ellipse in 33.25 years, and is subject to definite perturbations from the larger planets, Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus. These results were published in 1867.

Some experts consider this Adams's most substantial achievement. His "definitive orbit" for the Leonids coincided with that of the comet

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that warms and begins to release gases when passing close to the Sun, a process called outgassing. This produces an extended, gravitationally unbound atmosphere or Coma (cometary), coma surrounding ...

55P/Tempel-Tuttle and thereby suggested the, later widely accepted, close relationship between comets and meteors.

Later career

Ten years later,

Ten years later, George William Hill

George William Hill (March 3, 1838 – April 16, 1914) was an American astronomer and mathematician. Working independently and largely in isolation from the wider scientific community, he made major contributions to celestial mechanics and t ...

described a novel and elegant method for attacking the problem of lunar motion. Adams briefly announced his own unpublished work in the same field, which, following a parallel course had confirmed and supplemented Hill's.

Over a period of forty years, he periodically addressed the determination of the constants in Carl Friedrich Gauss

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss (; ; ; 30 April 177723 February 1855) was a German mathematician, astronomer, geodesist, and physicist, who contributed to many fields in mathematics and science. He was director of the Göttingen Observatory and ...

's theory of terrestrial magnetism. Again, the calculations involved great labour, and were not published during his lifetime. They were edited by his brother, William Grylls Adams, and appear in the second volume of the collected ''Scientific Papers''. Numerical computation of this kind might almost be described as his pastime. He calculated the Euler–Mascheroni constant, perhaps somewhat eccentrically, to 236 decimal places and evaluated the Bernoulli numbers up to the 62nd.

Adams had boundless admiration for Newton and his writings and many of his papers bear the cast of Newton's thought. In 1872, Isaac Newton Wallop, 5th Earl of Portsmouth, donated his private collection of Newton's papers to Cambridge University

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

. Adams and G. G. Stokes took on the task of arranging the material, publishing a catalogue in 1888.

The post of Astronomer Royal

Astronomer Royal is a senior post in the Royal Households of the United Kingdom. There are two officers, the senior being the astronomer royal dating from 22 June 1675; the junior is the astronomer royal for Scotland dating from 1834. The Astro ...

was offered him in 1881, but he preferred to pursue his teaching and research in Cambridge. He was British delegate to the International Meridian Conference

The International Meridian Conference was a conference held in October 1884 in Washington, D.C., in the United States, to determine a prime meridian for international use. The conference was held at the request of President of the United State ...

at Washington in 1884, when he also attended the meetings of the British Association at Montreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

and of the American Association at Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

.

Honours

* 1847 He is reputed to have been offered a knighthood onQueen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

's 1847 Cambridge visit but to have declined, either out of modesty, or fear of the financial consequences of such social distinction;

* 1847 Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

;

*1848 Copley medal

The Copley Medal is the most prestigious award of the Royal Society of the United Kingdom, conferred "for sustained, outstanding achievements in any field of science". The award alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the bio ...

of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

;

*1848 Adams Prize, founded by the members of St John's College, to be given biennially for the best treatise on a mathematical subject;

*1849 Elected Fellow of the Royal Society of London and Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

Fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (FRSE) is an award granted to individuals that the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Scotland's national academy of science and Literature, letters, judged to be "eminently distinguished in their subject". ...

;

*1851 and 1874 President of the Royal Astronomical Society

The Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) is a learned society and charitable organisation, charity that encourages and promotes the study of astronomy, planetary science, solar-system science, geophysics and closely related branches of science. Its ...

(1851–1853 and 1874–1876).

Family and death

After a long illness, Adams died at Cambridge on 21 January 1892 and was buried near his home in St Giles Cemetery, now the Parish of the Ascension Burial Ground in Cambridge. In 1863 he had married Miss Eliza Bruce (1827–1919), ofDublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

, who survived him, and is buried with him. His wealth at death was £32,434 (£2.6 million at 2003 prices).

Memorials

*Memorial inWestminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

with a portrait medallion, by Albert Bruce-Joy;

*A bust, by Joy in the hall of St John's College, Cambridge;

*Another youthful bust belongs to the Royal Astronomical Society;

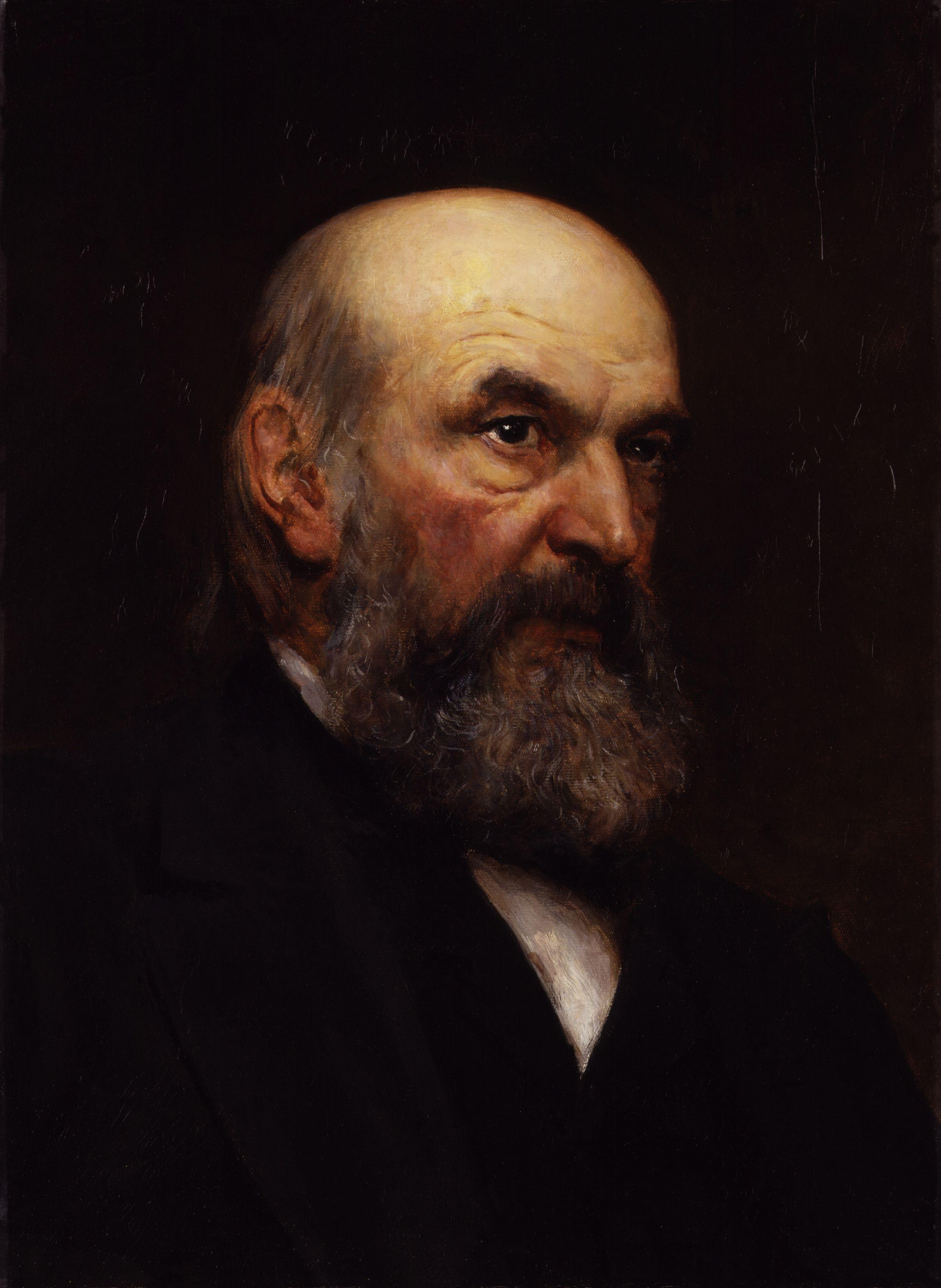

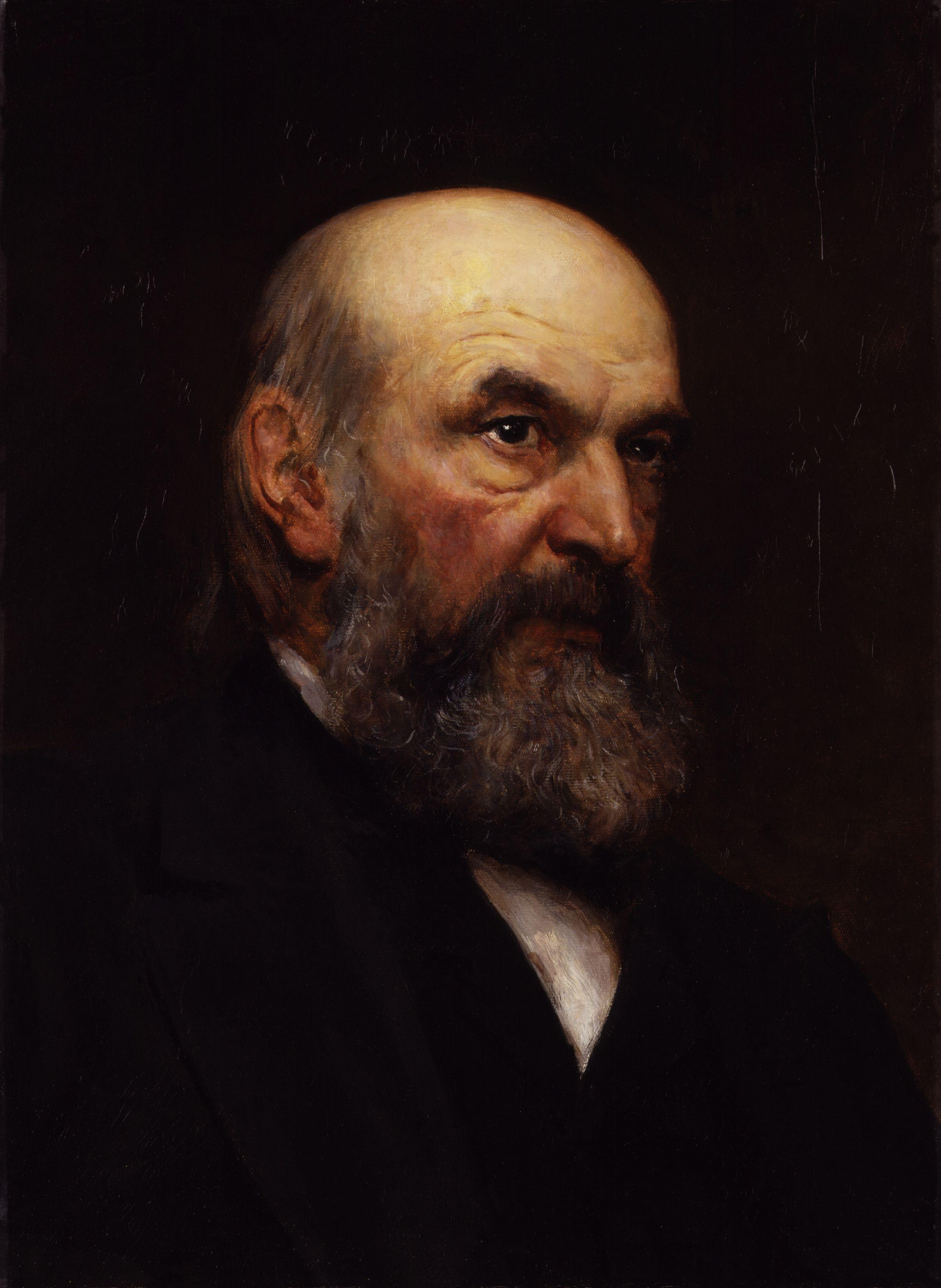

*Portraits by:

** Hubert von Herkomer in Pembroke College;

** Paul Raphael Montord in the combination room of St John's;

*A memorial tablet, with an inscription by Archbishop Benson, in Truro Cathedral;

* Passmore Edwards erected a public institute in his honour at Launceston, near his birthplace;

* Adams Nunatak, a nunatak

A nunatak (from Inuit language, Inuit ) is the summit or ridge of a mountain that protrudes from an ice field or glacier that otherwise covers most of the mountain or ridge. They often form natural pyramidal peaks. Isolated nunataks are also cal ...

on Neptune Glacier in Alexander Island

Alexander Island, which is also known as Alexander I Island, Alexander I Land, Alexander Land, Alexander I Archipelago, and Zemlja Alexandra I, is the largest island of Antarctica. It lies in the Bellingshausen Sea west of Palmer Land, Antarcti ...

in Antarctica, is named after him.

*Statue by Joy in Albert Square, Manchester

Albert Square is a public Town square, square in the centre of Manchester, England. It is dominated by its largest building, the Grade I listed Manchester Town Hall, a Gothic revival architecture, Victorian Gothic building by Alfred Waterhouse. ...

.

Obituaries

*''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'', 22 January 1892, p. 6 col. dlink on this page

* * * * non.(1891–92) ''Journal of the British Astronomical Association'' 2: 196–197

About Adams and the discovery of Neptune

* * fromProject Gutenberg

Project Gutenberg (PG) is a volunteer effort to digitize and archive cultural works, as well as to "encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks."

It was founded in 1971 by American writer Michael S. Hart and is the oldest digital li ...

*

*

*Doggett, L.E. (1997) "Celestial mechanics", in

*

*

*

*Harrison, H.M. (1994). ''Voyager in Time and Space: The Life of John Couch Adams, Cambridge Astronomer''. Lewes: Book Guild,

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* Lyttleton, Raymond Arthur, (1968) ''Mysteries of the Solar System'', Clarendon, Oxford, UK (1968), Chapter 7: The discovery of Neptune

By Adams

*Adams, J.C., ed. W.G. Adams & R. A. Sampson (1896–1900) ''The Scientific Papers of John Couch Adams'', 2 vols, London: Cambridge University Press, with a memoir by J.W.L. Glaisher: **Vol. 1 (1896) Previously published writings; **Vol. 2 (1900) Manuscripts including the substance of his lectures on the Lunar Theory. *Adams, J.C., ed. R.A. Sampson (1900''Lectures on the Lunar Theory''

London: Cambridge University Press *A collection, virtually complete, of Adams's papers regarding the discovery of Neptune was presented by Mrs Adams to the library of St John's College, see: Sampson (1904), and also: **"The collected papers of Prof. Adams", ''Journal of the British Astronomical Association'', 7 (1896–97) **''Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society'', 53 184; **''Observatory'', 15 174; **''

Nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

'', 34 565; 45 301;

**''Astronomical Journal'', No. 254;

**R. Grant, ''History of Physical Astronomy'', p. 168; and

**''Edinburgh Review

The ''Edinburgh Review'' is the title of four distinct intellectual and cultural magazines. The best known, longest-lasting, and most influential of the four was the third, which was published regularly from 1802 to 1929.

''Edinburgh Review'', ...

'', No. 381, p. 72.

*The papers were ultimately lodged with the Royal Greenwich Observatory and evacuated to Herstmonceux Castle

Herstmonceux Castle is a brick-built castle, dating from the 15th century, near Herstmonceux, East Sussex, England. It is one of the oldest significant brick buildings still standing in England. The castle was renowned for being one of the fi ...

during World War II. After the war, they were stolen by Olin J. Eggen and only recovered in 1998, hampering much historical research in the subject.

See also

* Intrigue at RAS and Cambridge Observatory from the biography of Richard Christopher CarringtonReferences

External links

*Biography on the St Andrews database

* * * * * Davor Krajnovic

John Couch Adams: mathematical astronomer, college friend of George Gabriel Stokes and promotor of women in astronomy

{{DEFAULTSORT:Adams, John Couch 1819 births 1892 deaths People from Launceston, Cornwall Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge 19th-century British astronomers 19th-century English mathematicians Lowndean Professors of Astronomy and Geometry Fellows of the Royal Society Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Neptune Scientists from Cornwall Recipients of the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society Recipients of the Copley Medal Senior Wranglers Methodist Church of Great Britain people Cornish Methodists 19th-century Methodists Honorary Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Academics of the University of St Andrews Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Presidents of the Royal Astronomical Society Members of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities Presidents of the Cambridge Philosophical Society