John C. H. Lee on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Clifford Hodges Lee (1 August 1887 – 30 August 1958) was a career US Army engineer, who rose to the rank of

Lee met with Major General Homer M. Groninger, the commander of the New York Port of Embarkation (POE), through which all troops and supplies for the ETO would be funnelled, and Lee and Larkin consulted with Lieutenant General James G. Harbord, who had commanded the SOS of the

Lee met with Major General Homer M. Groninger, the commander of the New York Port of Embarkation (POE), through which all troops and supplies for the ETO would be funnelled, and Lee and Larkin consulted with Lieutenant General James G. Harbord, who had commanded the SOS of the

Eisenhower was succeeded as commander of ETOUSA by Lieutenant General Frank M. Andrews on 4 February 1943. On Somervell's advice, Lee submitted a proposal to Andrews that he be named deputy theater commander for supply and administration, and that the theater G-4 branch be placed under him. This would have given Lee a status similar to that enjoyed by Somervell. Andrews rejected the proposal, but he did make some changes, moving part of SOS Headquarters to London while its operations staff remained in Cheltenham. Weaver was appointed Lee's deputy for operations. Andrews regarded Lee as "oppressively religious", and resolved to ask Marshall for his recall. Before he could do so, Andrews was killed in a plane crash in Iceland on 3 May, and was succeeded by Lieutenant General Jacob L. Devers, who agreed to abolish the theater G-4 and transfer its functions to Lee.

For the cross-channel attack, now postponed to 1944 and codenamed

Eisenhower was succeeded as commander of ETOUSA by Lieutenant General Frank M. Andrews on 4 February 1943. On Somervell's advice, Lee submitted a proposal to Andrews that he be named deputy theater commander for supply and administration, and that the theater G-4 branch be placed under him. This would have given Lee a status similar to that enjoyed by Somervell. Andrews rejected the proposal, but he did make some changes, moving part of SOS Headquarters to London while its operations staff remained in Cheltenham. Weaver was appointed Lee's deputy for operations. Andrews regarded Lee as "oppressively religious", and resolved to ask Marshall for his recall. Before he could do so, Andrews was killed in a plane crash in Iceland on 3 May, and was succeeded by Lieutenant General Jacob L. Devers, who agreed to abolish the theater G-4 and transfer its functions to Lee.

For the cross-channel attack, now postponed to 1944 and codenamed  The logistical arrangements for

The logistical arrangements for

Generals of World War II

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lee, John C. H. 1887 births 1958 deaths United States Army Corps of Engineers personnel People from Junction City, Kansas Military personnel from Kansas American military personnel of World War I Burials at Arlington National Cemetery United States Military Academy alumni Recipients of the Silver Star Recipients of the Legion of Merit Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Recipients of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal Honorary Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire American recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France) American recipients of the Croix de guerre (Belgium) Recipients of the Order of Agricultural Merit United States Army generals of World War II United States Army generals United States Army personnel of World War I

lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was norma ...

and commanded the Communications Zone (ComZ) in the European Theater of Operations

The European Theater of Operations, United States Army (ETOUSA) was a Theater (warfare), theater of Operations responsible for directing United States Army operations throughout the European theatre of World War II, from 1942 to 1945. It command ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

A graduate of the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

at West Point, New York

West Point is the oldest continuously occupied military post in the United States. Located on the Hudson River in New York (state), New York, General George Washington stationed his headquarters in West Point in the summer and fall of 1779 durin ...

, with the class of 1909, Lee assisted with various domestic engineering navigation projects as well as in the Panama Canal Zone, Guam and the Philippines. During World War I, he served on the Western Front on the staff of the 82d and 89th Divisions and earned promotions to major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

, lieutenant colonel and colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

as well as the Silver Star

The Silver Star Medal (SSM) is the United States Armed Forces' third-highest military decoration for valor in combat. The Silver Star Medal is awarded primarily to members of the United States Armed Forces for gallantry in action against a ...

Medal, the Army Distinguished Service Medal

The Distinguished Service Medal (DSM) is a military decoration of the United States Army that is presented to soldiers who have distinguished themselves by exceptionally meritorious service to the government in a duty of great responsibility. ...

and the Croix de Guerre

The (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awarded during World ...

from the French government.

After World War I, Lee served again in the Philippines, then became District Engineer of the Vicksburg District, responsible for flood control and navigation for a section of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

and its tributaries. During the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, he directed relief work, attempted to shore up the levees, and coordinated the evacuations of towns and districts. He then directed various engineer districts around Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania during the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

.

As World War II began, Lee received a promotion to brigadier general and command of the Pacific coast embarkation zones, then of the 2d Infantry Division

The 2nd Infantry Division (2ID, 2nd ID) ("Indianhead") is a formation of the United States Army. Since the 1960s, its primary mission has been the pre-emptive defense of South Korea in the event of an invasion from North Korea. Approximately 17 ...

. Promoted to command the Services of Supply

The Services of Supply or "SOS" branch of the Army of the USA was created on 28 February 1942 by Executive Order Number 9082 "Reorganizing the Army and the War Department" and War Department Circular No. 59, dated 2 March 1942. Services of Supp ...

in the European Theater of Operations after the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

, he helped support Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8–16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa whil ...

, the Allied invasion of Northwest Africa, and Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allies of World War II, Allied operation that launched the successful liberation of German-occupied Western Front (World War II), Western Europe during World War II. The ope ...

, the Allied invasion of Normandy. The Services of Supply were merged with the European Theater of Operations, United States Army

The European Theater of Operations, United States Army (ETOUSA) was a theater of Operations responsible for directing United States Army operations throughout the European theatre of World War II, from 1942 to 1945. It commanded Army Ground Forc ...

to form ComZ, which supported the advance across France and the Allied Invasion of Germany. Lee received many awards for his service from various Allied countries. A man of strong religious convictions, he urged that African-Americans be integrated into what was then a segregated Army.

Early life

John Clifford Hodges Lee was born inJunction City, Kansas

Junction City is a city in and the county seat of Geary County, Kansas, Geary County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population of the city was 22,932. Fort Riley, a major United States Army, U.S. ...

on August 1, 1887, the son of Charles Fenelon Lee and John Clifford Hodges. He had two siblings: an older sister, Katherine, and a younger sister, Josephine. Known as Clifford Lee during his teenage years, he graduated from Junction City High School in 1905, ranked second in his class. His high school success enabled him to compete in 1904 for a 1905 appointment to the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

from Representative Charles Frederick Scott without having to take the qualifying exam. He was selected as the first alternate, and planned to attend the Colorado School of Mines

The Colorado School of Mines (Mines) is a public research university in Golden, Colorado, United States. Founded in 1874, the school offers both undergraduate and graduate degrees in engineering, science, and mathematics, with a focus on ener ...

, but received the West Point appointment after the first choice resigned.

Lee graduated 12th in the class of 1909. His classmates included Jacob L. Devers, who was ranked 39th, and George S. Patton Jr., who was 46th. The top 15 ranking members of the class accepted commissions in the United States Army Corps of Engineers

The United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) is the military engineering branch of the United States Army. A direct reporting unit (DRU), it has three primary mission areas: Engineer Regiment, military construction, and civil wo ...

, into which Lee was commissioned as a second lieutenant on 11 June 1909.

Early military engineer career

Lee was sent toDetroit, Michigan

Detroit ( , ) is the List of municipalities in Michigan, most populous city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is situated on the bank of the Detroit River across from Windsor, Ontario. It had a population of 639,111 at the 2020 United State ...

from 12 September to 2 December 1909, then to the Panama Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone (), also known as just the Canal Zone, was a International zone#Concessions, concession of the United States located in the Isthmus of Panama that existed from 1903 to 1979. It consisted of the Panama Canal and an area gene ...

until May 1910, after which he was posted to Rock Island, Illinois

Rock Island is a city in Rock Island County, Illinois, United States, and its county seat. The population was 37,108 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Located at the confluence of the Rock River (Mississippi River tributary), Rock a ...

, where he worked on a project on the upper Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

, then in July 1910 to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, second-most populous city in Pennsylvania (after Philadelphia) and the List of Un ...

, to work on the Ohio River

The Ohio River () is a river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing in a southwesterly direction from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to its river mouth, mouth on the Mississippi Riv ...

locks. In August 1910 he went to Washington Barracks for further training at the Engineer School there. On graduation in October 1911, he reported to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where he was in charge of the engineer stables, corrals and shops with the 3d Engineer Battalion.

Promoted to first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a se ...

on 27 February 1912, Lee became an instructor for the Ohio National Guard

The Ohio National Guard comprises the Ohio Army National Guard and the Ohio Air National Guard. The commander-in-chief of the Ohio Army National Guard is the List of governors of Ohio, governor of the U.S. state of Ohio. If the Ohio Army Nation ...

, then returned to the 3d Battalion at Fort Leavenworth. In September and October 1912, he was aide de camp to the Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

, Henry L. Stimson. When the Chief of Staff of the United States Army

The chief of staff of the Army (CSA) is a statutory position in the United States Army held by a general officer. As the highest-ranking officer assigned to serve in the Department of the Army, the chief is the principal military advisor and a ...

, Major General Leonard Wood

Leonard Wood (October 9, 1860 – August 7, 1927) was a United States Army major general, physician, and public official. He served as the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, List of colonial governors of Cuba, Military Governor of Cuba, ...

, asked Lee what assignment he would like next, he requested return to his battalion, which was being deployed to Texas City, Texas

Texas City is a city in Galveston County, Texas, United States, on the southwest shoreline of Galveston Bay. Texas City is a deepwater port on Texas's Gulf Coast, as well as a petroleum-refining and petrochemical-manufacturing center. The popu ...

on the Mexican Border, where there were security concerns as a result of the Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution () was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from 20 November 1910 to 1 December 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It saw the destruction of the Federal Army, its ...

.

In October 1913, Lee and the 3d Engineer Battalion departed for the Western Pacific. He conducted topographical survey work on Guam

Guam ( ; ) is an island that is an Territories of the United States, organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. Guam's capital is Hagåtña, Guam, Hagåtña, and the most ...

from 23 October 1913 to 30 July 1914, and then in the Philippines, where he was Senior Topographical Inspector with the Philippine Department

The Philippine Department (Filipino: ''Kagawaran ng Pilipinas/Hukbong Kagawaran ng Pilipinas'') was a regular United States Army organization whose mission was to defend the Philippine Islands and train the Philippine Army. On 9 April 1942, duri ...

from December 1914 to October 1915. He commanded the Northern District on Luzon

Luzon ( , ) is the largest and most populous List of islands in the Philippines, island in the Philippines. Located in the northern portion of the List of islands of the Philippines, Philippine archipelago, it is the economic and political ce ...

from December 1914 to June 1915, and the Cagayan

Cagayan ( ), officially the Province of Cagayan (; ; ; isnag language, Isnag: ''Provinsia nga Cagayan''; ivatan language, Ivatan: ''Provinsiya nu Cagayan''; ; ), is a Provinces of the Philippines, province in the Philippines located in the Cag ...

District from July to September 1915. He returned to the United States in November 1915, and was assigned to the Wheeling District in Wheeling, West Virginia

Wheeling is a city in Ohio County, West Virginia, Ohio and Marshall County, West Virginia, Marshall counties in the U.S. state of West Virginia. The county seat of Ohio County, it lies along the Ohio River in the foothills of the Appalachian Mo ...

, where he was responsible for the completion of the No. 14 Dam on the Ohio River. Lee was promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

on 3 June 1916. For his thesis, he submitted the ''Manual for Topographers'' he had written in the Philippines.

In Wheeling, Lee met and married Sarah Ann Row. Reverend Robert E. L. Strider Sr., who later became the Bishop of the West Virginia

West Virginia is a mountainous U.S. state, state in the Southern United States, Southern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.The United States Census Bureau, Census Bureau and the Association of American ...

, conducted the ceremony at St. Matthew's Church in Wheeling on 24 September 1917. The couple's only child, John Clifford Hodges Lee Jr., was born on 12 July 1918 and would likewise become a career Army officer, serving in World War II and various domestic assignments, ending his career as Colonel leading the Office of Appalachian Studies, and dying in 1975.

World War I

Lee was appointed Wood's aide de camp on 23 April 1917, shortly after the United States formally declared war on Germany. Wood was offered commands in Hawaii and the Philippines, but turned them down in order to take command of the 89th Division, a newly-formed National Army division, atCamp Funston

Camp Funston is a U.S. Army training camp located on the grounds of Fort Riley, southwest of Manhattan, Kansas. The camp was named for Brigadier General Frederick Funston (1865–1917). It is one of sixteen such camps that were established at ...

, Kansas, in which Wood had been appointed to command. Lee, who was promoted to major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

on 5 August 1917 and lieutenant colonel on 14 February 1918, became the division's acting chief of staff and then assistant chief of staff.

On 18 February 1918, Lee departed for France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, where he studied at the Army General Staff College of the American Expeditionary Forces

The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) was a formation of the United States Armed Forces on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front during World War I, composed mostly of units from the United States Army, U.S. Army. The AEF was establis ...

(AEF) at Langres

Langres () is a commune in France, commune in northeastern France. It is a Subprefectures in France, subprefecture of the Departments of France, department of Haute-Marne, in the Regions of France, region of Grand Est.

History

As the capital ...

from 13 March to 30 May. Upon graduation he was assigned as the assistant chief of staff, or G-2, (intelligence officer) of the 82d Division. He was awarded the recently created Silver Star

The Silver Star Medal (SSM) is the United States Armed Forces' third-highest military decoration for valor in combat. The Silver Star Medal is awarded primarily to members of the United States Armed Forces for gallantry in action against a ...

for leading a patrol behind enemy lines on 12/13 July.

That month, the 89th Division reached France, albeit without Wood, who had been relieved of command on the eve of its departure for France and temporarily replaced by Brigadier General Frank L. Winn before Major General William M. Wright took over in September. On 18 July Lee returned to it as its Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3 (operations officer). He participated in the Battle of Saint-Mihiel

The Battle of Saint-Mihiel was a major World War I battle fought from 12 to 15 September 1918, involving the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) and 110,000 French troops under the command of General John J. Pershing of the United States again ...

, at the conclusion of which he became the division's chief of staff. He was promoted to colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

on 1 August 1918, and as such participated in the Meuse–Argonne offensive

The Meuse–Argonne offensive (also known as the Meuse River–Argonne Forest offensive, the Battles of the Meuse–Argonne, and the Meuse–Argonne campaign) was a major part of the final Allies of World War I, Allied Offensive (military), offe ...

which followed Saint-Mihiel.

For his service, he was awarded the Army Distinguished Service Medal

The Distinguished Service Medal (DSM) is a military decoration of the United States Army that is presented to soldiers who have distinguished themselves by exceptionally meritorious service to the government in a duty of great responsibility. ...

. His citation read:

Lee was also awarded the French Croix de Guerre

The (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awarded during World ...

, and was made an Officer of the French Legion of Honor

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and civil. Currently consisting of five classes, it was ...

.

Between the wars

After service atKoblenz

Koblenz ( , , ; Moselle Franconian language, Moselle Franconian: ''Kowelenz'') is a German city on the banks of the Rhine (Middle Rhine) and the Moselle, a multinational tributary.

Koblenz was established as a Roman Empire, Roman military p ...

in the Allied occupation of the Rhineland

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are call ...

, the 89th Division returned to Camp Funston in June 1919, where it was demobilized. Lee rejoined Wood as a staff officer at his Central Department Headquarters in Chicago. Lee reverted to his permanent rank of captain on 15 February 1920, but was promoted to major again the following day. He was Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3, of the new Chicago-based VI Corps Area which succeeded the Central Department, from August 1920 to April 1921. Lee was disappointed at the failure of Wood's quest for the Republican nomination in the 1920 presidential election, believing that Wood would have made a better president than the ultimate winner, Warren Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents w ...

.

Lee served a second tour of the Philippines as G-2 of the Philippine Department from September 1923 to July 1926. On returning to the United States, he was posted to Vicksburg, Mississippi

Vicksburg is a historic city in Warren County, Mississippi, United States. It is the county seat. The population was 21,573 at the 2020 census. Located on a high bluff on the east bank of the Mississippi River across from Louisiana, Vicksburg ...

, as the District Engineer. This coincided with the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, the most destructive river flood in the history of the United States. Over were flooded, 162,000 homes were damaged and 9,000 homes destroyed. Lee directed relief work, attempts to shore up the levees, and evacuations of towns and districts.

The United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

responded with the Flood Control Act of 1928

The Flood Control Act of 1928 (FCA 1928) (70th United States Congress, Sess. 1. Ch. 569, enacted May 15, 1928) authorized the United States Army Corps of Engineers to design and construct projects for the control of floods on the Mississippi Rive ...

, which provided for improved flood control measures. Lee supervised works on the Red River, Ouachita River

The Ouachita River ( ) is a river that runs south and east through the United States, U.S. U.S. state, states of Arkansas and Louisiana, joining the Tensas River to form the Black River (Louisiana), Black River near Jonesville, Louisiana. It i ...

and Yazoo River

The Yazoo River is a river primarily in the U.S. state of Mississippi. It is considered by some to mark the southern boundary of what is called the Mississippi Delta, a broad floodplain that was cultivated for cotton plantations before the Ame ...

. The legislation moved the headquarters of the Mississippi River Commission

The United States Army Corps of Engineers Mississippi Valley Division (MVD) is responsible for the Corps water resources programs within 370,000-square-miles of the Mississippi River Valley, as well as the watershed portions of the Red River ...

from St Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an Independent city (United States), independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Miss ...

to Vicksburg, where it was located at the center of the flood area but well above the level of the river. Lee directed the construction of the new headquarters facility, and of the Waterways Experiment Station there.

Lee attended the Army War College from September 1931 to June 1932, and then was Assistant Commandant of the Army Industrial College until January 1934. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel again on 1 December 1933. He was seconded to the Civil Works Administration until May 1934, when he became District Engineer of the Washington District, in charge of Potomac River

The Potomac River () is in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and flows from the Potomac Highlands in West Virginia to Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography D ...

watershed, northwestern Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula, including parts of the Ea ...

and the Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, water supply. He was then District Engineer of the Philadelphia District until April 1938, when he was made Division Engineer of the North Pacific Division, based in Portland, Oregon

Portland ( ) is the List of cities in Oregon, most populous city in the U.S. state of Oregon, located in the Pacific Northwest region. Situated close to northwest Oregon at the confluence of the Willamette River, Willamette and Columbia River, ...

. He was promoted to colonel again on 1 June 1938.

In 1938 Lee became an hereditary member of the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati

The Society of the Cincinnati is a lineage society, fraternal, hereditary society founded in 1783 to commemorate the American Revolutionary War that saw the creation of the United States. Membership is largely restricted to descendants of milita ...

.

World War II

Zone of the Interior

Promoted to brigadier general in theArmy of the United States

The Army of the United States was one of the four major service components of the United States Army. Today, the Army consists of the Regular Army, the Army National Guard of the United States, the Army National Guard while in the service of the ...

on 1 October 1940, Lee was commanding general of Pacific Ports of Embarkation, working out of Fort Mason

Fort Mason, in San Francisco, California is a former United States Army post located in the northern Marina District, alongside San Francisco Bay. Fort Mason served as an Army post for more than 100 years, initially as a coastal defense site a ...

, California. He was responsible for updating all Pacific ports for wartime, engineering the changes needed to transfer materiel and troops more efficiently from rail to ship. However, he was warned by the Chief of Staff of the United States Army

The chief of staff of the Army (CSA) is a statutory position in the United States Army held by a general officer. As the highest-ranking officer assigned to serve in the Department of the Army, the chief is the principal military advisor and a ...

, General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

George C. Marshall, that his tenure might be brief, and might soon be given another assignment, so he should select a deputy and train him to take over. Lee chose Colonel Frederick Gilbreath.

A sign that Lee was being considered for a command assignment was his being sent to Fort Benning

Fort Benning (named Fort Moore from 2023–2025) is a United States Army post in the Columbus, Georgia area. Located on Georgia's border with Alabama, Fort Benning supports more than 120,000 active-duty military, family members, reserve compone ...

, Georgia, for a refresher course on infantry tactics. Lee was designated as an observer at the Louisiana Maneuvers

The Louisiana Maneuvers were a series of major U.S. Army exercises held from August to September 1941 in northern and west-central Louisiana, an area bounded by the Sabine River to the west, the Calcasieu River to the east, and by the city of ...

in 1940 and 1941. During those maneuvers, the 2d Infantry Division

The 2nd Infantry Division (2ID, 2nd ID) ("Indianhead") is a formation of the United States Army. Since the 1960s, its primary mission has been the pre-emptive defense of South Korea in the event of an invasion from North Korea. Approximately 17 ...

had been disappointing, and Lee was ordered to assume command of it at Fort Sam Houston

Fort Sam Houston is a United States Army, U.S. Army post in San Antonio, Texas.

"Fort Sam Houston, TX • About Fort Sam Houston" (overview), US Army, 2007, webpageSH-Army. Known colloquially as "Fort Sam", it is named for the first president o ...

, Texas, and bring it up to standard. He replaced the commander of the 38th Infantry Regiment with Colonel William G. Weaver. Lee was concerned about the performance of the divisional artillery, and arranged for it to receive additional training at Fort Sill

Fort Sill is a United States Army post north of Lawton, Oklahoma, about 85 miles (137 km) southwest of Oklahoma City. It covers almost .

The fort was first built during the Indian Wars. It is designated as a National Historic Landmark a ...

, Oklahoma, which was where he was when he heard the news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941. At the tim ...

, which brought the United States into World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was norma ...

Lesley J. McNair was impressed with Lee's performance, and Lee was promoted to major general on 14 February 1942.

Bolero

In May 1942, the War Department considered the creation of a Services of Supply (SOS) organization in theEuropean Theater of Operations

The European Theater of Operations, United States Army (ETOUSA) was a Theater (warfare), theater of Operations responsible for directing United States Army operations throughout the European theatre of World War II, from 1942 to 1945. It command ...

(ETO) to handle the large volume of service troops and supplies being deployed to the United Kingdom for Operation Bolero

Operation Bolero was the commonly used reference for the code name of the United States military troop buildup in the United Kingdom during World War II in preparation for the initial cross-channel invasion plan known as Operation Roundup, to ...

, the buildup of US troops there for Operation Sledgehammer

Operation Sledgehammer was an Allies of World War II, Allied plan for a cross-English Channel, Channel invasion of Europe during World War II, as the first step in helping to reduce pressure on the Soviet Red Army by establishing a Western Front ( ...

, the proposed Allied invasion of France in 1942, and Operation Roundup, the larger follow up operation in 1943. Lee's name was put forward for the position of its commander by the Secretary of War, Stimson; the commander of United States Army Services of Supply (USASOS), Lieutenant General Brehon B. Somervell; and McNair, the commander of Army Ground Forces

The Army Ground Forces were one of the three autonomous components of the Army of the United States during World War II, the others being the Army Air Forces and Army Service Forces. Throughout their existence, Army Ground Forces were the la ...

. Marshall had already formed a positive impression of Lee when he had commanded the Pacific Ports of Embarkation, and decided to appoint him.

Lee arrived in Washington, D.C., on 5 May 1942, where he attended two weeks' of conferences about Bolero and the form of organization for the ETO SOS that Marshall and Somervell had in mind. They were determined that the organization of the SOS in the theaters of war should be identical to that of the USASOS in the United States. During World War I, this had not been the case, and the resultant overlapping and criss-crossing lines of communication had caused great confusion and inefficiency, both in Washington, D.C. and in Tours. Somervell instructed each chief in the USASOS to recommend the best two men in his branch, one of whom would accompany Lee, while the other remained in Washington, D.C. For his chief of staff, Lee chose Colonel Thomas B. Larkin

Lieutenant General Thomas Bernard Larkin (December 15, 1890 – October 17, 1968) was a military officer who served as the 32nd Quartermaster General (United States), Quartermaster General of the United States Army.

Early life

Larkin was born i ...

, who was promoted to brigadier general.

Lee met with Major General Homer M. Groninger, the commander of the New York Port of Embarkation (POE), through which all troops and supplies for the ETO would be funnelled, and Lee and Larkin consulted with Lieutenant General James G. Harbord, who had commanded the SOS of the

Lee met with Major General Homer M. Groninger, the commander of the New York Port of Embarkation (POE), through which all troops and supplies for the ETO would be funnelled, and Lee and Larkin consulted with Lieutenant General James G. Harbord, who had commanded the SOS of the American Expeditionary Force

The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) was a formation of the United States Armed Forces on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front during World War I, composed mostly of units from the United States Army, U.S. Army. The AEF was establis ...

during World War I. Harbord noted that he too had commanded the 2d Division before being given the SOS assignment. He recommended that Lee obtain a personal train. Harbord had been given one by the French in World War I and had found it invaluable.

Lee flew to the UK on 23 May 1942 with the nine staff who would form the nucleus of his new command. He found that the commander of the United States Forces in the British Isles (USAFBI), Major General James E. Chaney, had prepared a different plan for the organization of the ETO headquarters, one along the orthodox lines laid out in the '' Field Service Regulations'', with Brigadier General Donald A. Davison designated to command the SOS. But Marshall had selected Lee, and he had mandated that the new theater organization should be "along the general pattern of a command post with a minimum of supply and administrative services." Somervell and Major General Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

, the head of the Operations Division of the War Department General Staff, arrived in London on 26 May for discussions with Chaney about the organization of the ETO and the SOS. USAFBI officially became European Theater of Operations, United States Army

The European Theater of Operations, United States Army (ETOUSA) was a theater of Operations responsible for directing United States Army operations throughout the European theatre of World War II, from 1942 to 1945. It commanded Army Ground Forc ...

(ETOUSA) on 8 June, and Chaney was replaced by Eisenhower on 24 June.

Somervell and Lee conducted a whirlwind inspection tour of US depots and bases in England on a special train belonging to General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Sir Bernard Paget, the British Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces. This reminded Lee of Harbord's advice about the special train. They took up the matter with Lord Leathers, the British Minister of War Transport, who agreed to provide a small train. It had a car for Lee, two cars for his staff, a conference car, two flatcars for vehicles, and a dining car.

One of Lee's first concerns was to find a suitable location for his SOS headquarters. He found limited space at its initial location at No. 1 Great Cumberland Place in London, and decided to locate the headquarters in southern England where most base installations would be located. Brigadier General Claude N. Thiele, Lee's chief of administrative services, suggested Cheltenham

Cheltenham () is a historic spa town and borough adjacent to the Cotswolds in Gloucestershire, England. Cheltenham became known as a health and holiday spa town resort following the discovery of mineral springs in 1716, and claims to be the mo ...

, in Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( , ; abbreviated Glos.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Herefordshire to the north-west, Worcestershire to the north, Warwickshire to the north-east, Oxfordshire ...

, about west of London. The British War Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

administrative staff occupied of offices there, but were willing to return to their old London location. A regional organization was adopted on 20 July, with the UK divided into four base sections.

Torch

By the end of June 1942, there were 54,845 US troops in the UK, but a series of defeats inNorth Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

and on the Russian front, along with heavy losses from submarine attacks, convinced the British Chiefs of Staff that Sledgehammer would not be feasible. Instead, Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8–16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa whil ...

, an invasion of Northwest Africa, was substituted. This changed only the purpose of Bolero; over of stores and supplies still arrived in August, September, and October.

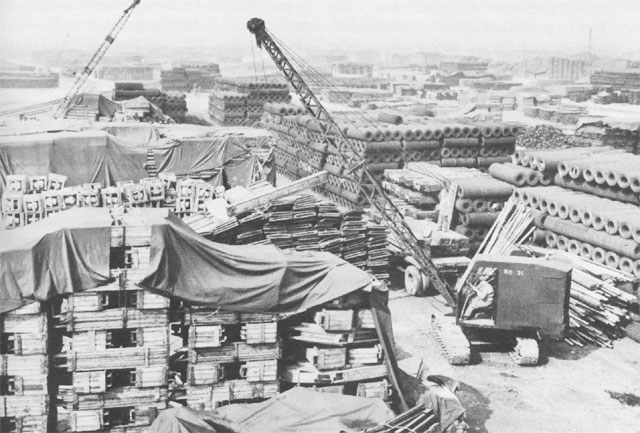

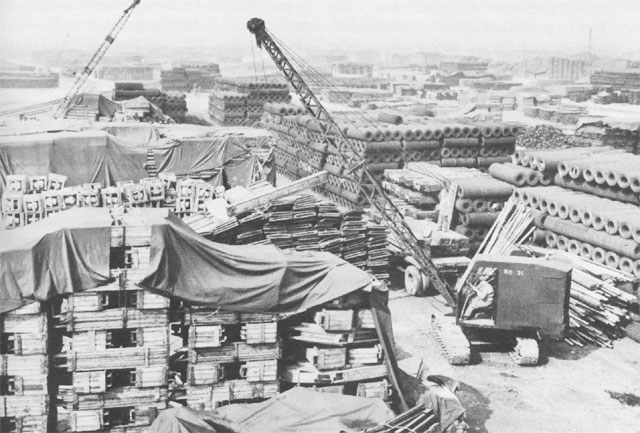

Although less than Somervell hoped, it was more than Lee's service units could cope with. Stores and supplies had to be cleared from the port areas as quickly as possible lest they become targets for German bombing raids. There was no time to build new depots, so they were shipped to British depots and warehouses. The Americans and British were unfamiliar with each other's procedures.

Priority had been given to shipping combat units, and service units made up only 21 percent of the theater's strength, which was insufficient. Nor were more units available in the United States; the mobilization program had also produced too few service units, and Somervell was forced to ship partly trained units in the hope that they could learn on the job. Perhaps 30 percent of the stores arrived with no markings indicating what they were, and 25 percent were merely marked by general type, such as medical or ordnance stores. Lee did not have enough personnel to sort, identify and catalog their contents. Soon vast quantities of stores and supplies could not be located.

In August it was discovered that most of the organizational equipment of the 1st Infantry Division, which was earmarked for Operation Torch, was still in the United States, and none of the hospitals earmarked for Torch arrived with their full equipment before October. Lee was initially optimistic that he could turn the situation around, but by September, there was no option but to request that USASOS re-ship stores that had already been despatched but could not be located if Torch was to be mounted on time. Eisenhower, who had been designated to command Torch, leaned on Lee, and withdrew his recommendation that Lee succeed him as commander of ETOUSA. Strenuous efforts were made, and by October Lee was able to report that the needs of Torch would be met.

The needs of Torch placed a heavy drain on the resources of Lee's command. There were 228,000 US troops in the UK in October, but 151,000 went to North Africa by the end of February 1943. The SOS also lost key officers, including Larkin. Some of supplies were shipped from the UK to North Africa between October 1942 and April 1943, while receipts totalled less than per month. Lee forcefully argued that preparations for Roundup should resume. He visited North Africa in January 1943 after taking a course as an air gunner so he would not be a useless passenger of the aircraft, and spoke to Patton and General Sir Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and the ...

about their supply situation.

Overlord

Eisenhower was succeeded as commander of ETOUSA by Lieutenant General Frank M. Andrews on 4 February 1943. On Somervell's advice, Lee submitted a proposal to Andrews that he be named deputy theater commander for supply and administration, and that the theater G-4 branch be placed under him. This would have given Lee a status similar to that enjoyed by Somervell. Andrews rejected the proposal, but he did make some changes, moving part of SOS Headquarters to London while its operations staff remained in Cheltenham. Weaver was appointed Lee's deputy for operations. Andrews regarded Lee as "oppressively religious", and resolved to ask Marshall for his recall. Before he could do so, Andrews was killed in a plane crash in Iceland on 3 May, and was succeeded by Lieutenant General Jacob L. Devers, who agreed to abolish the theater G-4 and transfer its functions to Lee.

For the cross-channel attack, now postponed to 1944 and codenamed

Eisenhower was succeeded as commander of ETOUSA by Lieutenant General Frank M. Andrews on 4 February 1943. On Somervell's advice, Lee submitted a proposal to Andrews that he be named deputy theater commander for supply and administration, and that the theater G-4 branch be placed under him. This would have given Lee a status similar to that enjoyed by Somervell. Andrews rejected the proposal, but he did make some changes, moving part of SOS Headquarters to London while its operations staff remained in Cheltenham. Weaver was appointed Lee's deputy for operations. Andrews regarded Lee as "oppressively religious", and resolved to ask Marshall for his recall. Before he could do so, Andrews was killed in a plane crash in Iceland on 3 May, and was succeeded by Lieutenant General Jacob L. Devers, who agreed to abolish the theater G-4 and transfer its functions to Lee.

For the cross-channel attack, now postponed to 1944 and codenamed Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allies of World War II, Allied operation that launched the successful liberation of German-occupied Western Front (World War II), Western Europe during World War II. The ope ...

, the service chiefs wanted 490,000 SOS troops. Devers trimmed this to 375,000, which would be 25 percent of the theater troop strength, a figure that was accepted by the War Department. The most acute shortages in 1943 were of engineer units to build new airbases, hospitals, supply depots and training facilities. As in 1942, Lee was forced to accept partly trained units. In the first four months of 1944, the number of SOS troops in the UK increased from 79,900 to 220,200. Some lessons had been learned from 1942. The New York POE started turning back incorrectly labelled cargo. In the first day this system went into operation, some 14,700 items were returned to the depots.

On 16 January 1944, Eisenhower returned to take control of the Allied forces for Overlord. His headquarters was designated Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). With SHAEF taking over the operational functions, ETOUSA was combined with SOS to create what would become the Communications Zone (Com Z) once operations commenced. A complicating factor was the creation of the First United States Army Group under Lieutenant General Omar N. Bradley

Omar Nelson Bradley (12 February 1893 – 8 April 1981) was a senior Officer (armed forces), officer of the United States Army during and after World War II, rising to the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He wa ...

, who sought to place logistical functions under his command.

Lee also conflicted with Eisenhower's chief of staff, Lieutenant General Walter B. Smith. While Eisenhower respected Lee's administrative talents, Smith resented Lee's position as deputy theater commander, which allowed Lee to bypass Eisenhower, and occasionally frustrate Smith's efforts to rein in the operational commanders like Bradley and Patton through logistics. Smith arranged for his own protégé, Major General Royal B. Lord, to be appointed as Lee's deputy.

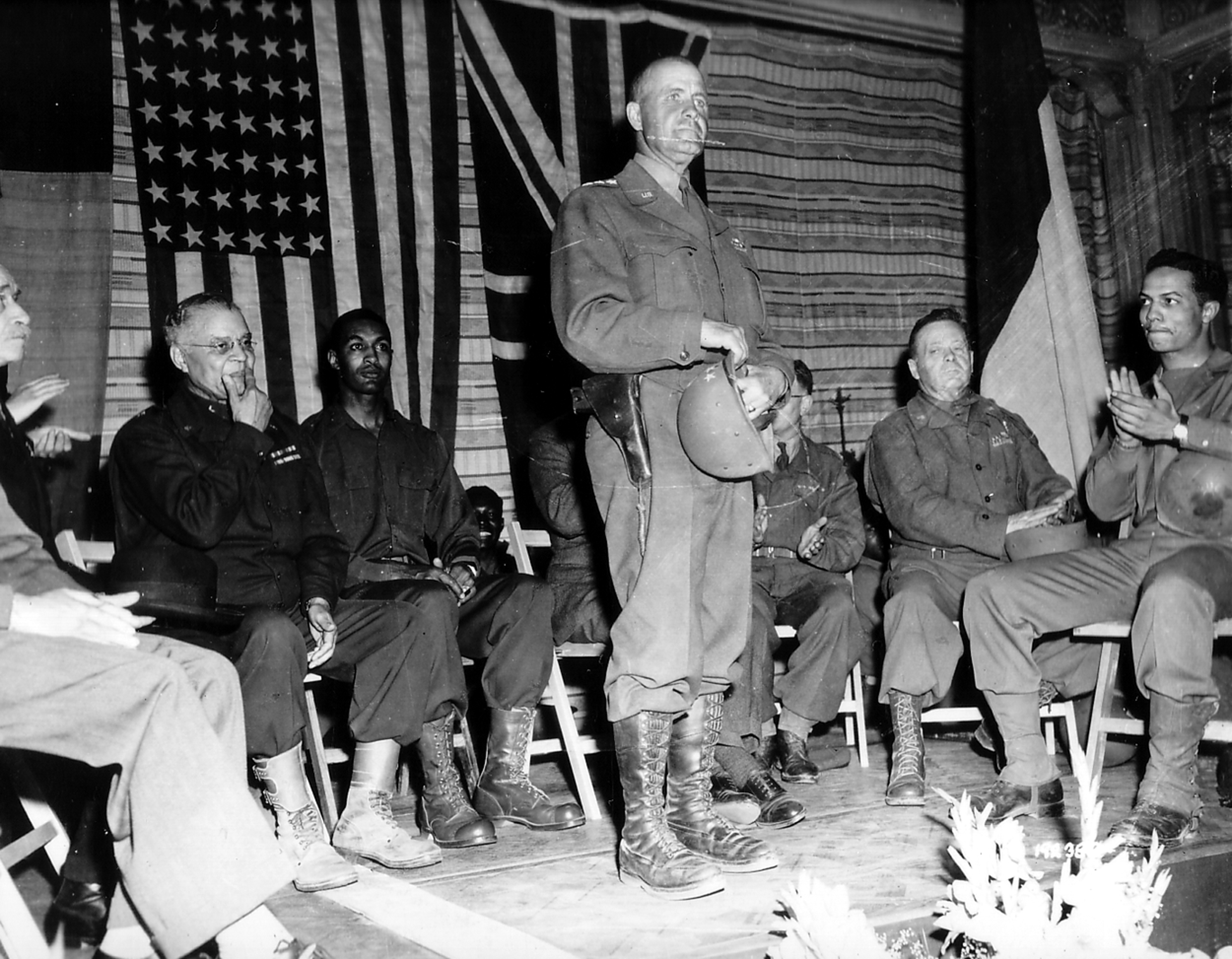

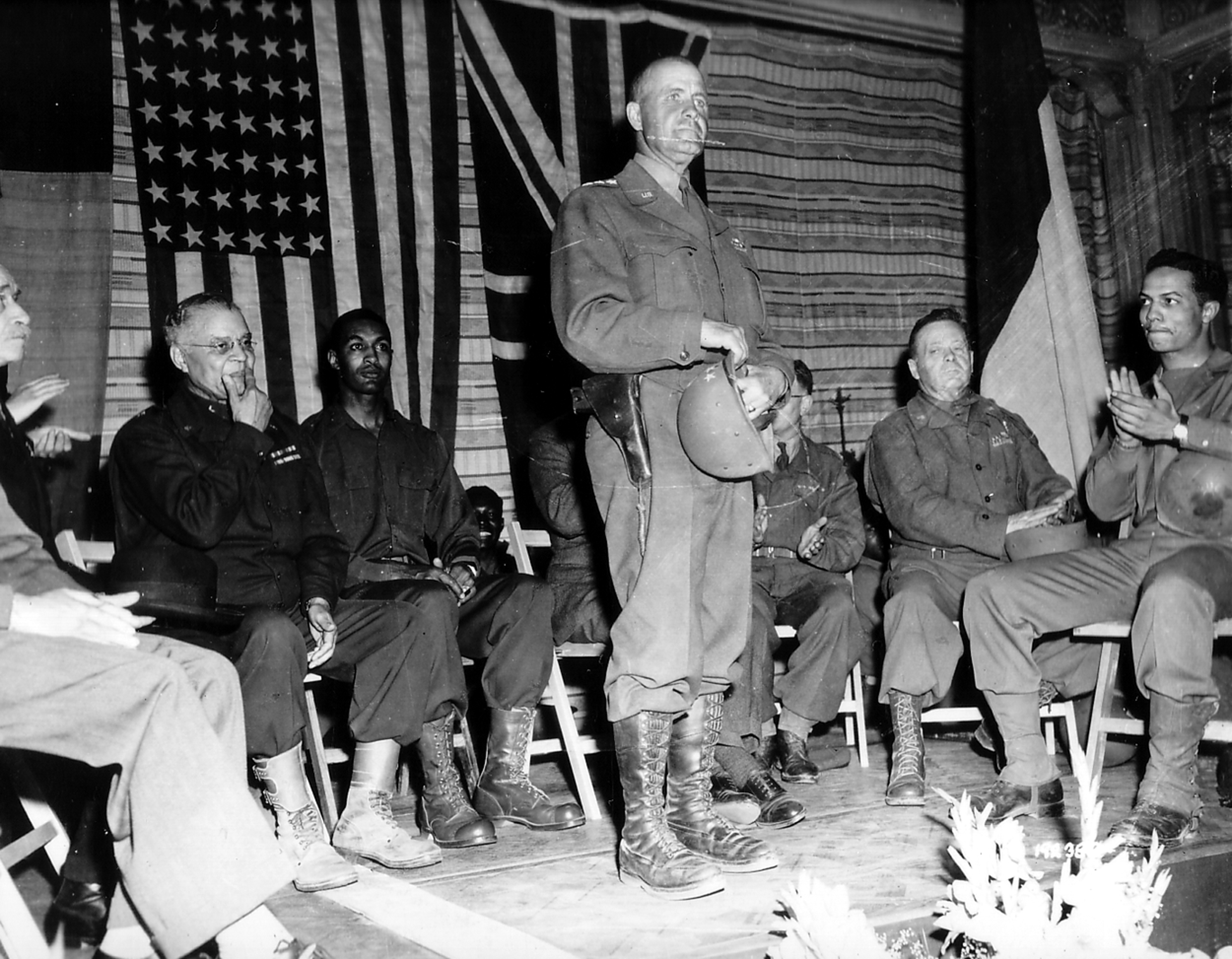

On 21 February 1944, Lee was promoted to lieutenant general, along with Courtney H. Hodges, Richard K. Sutherland and Raymond A. Wheeler. Lee began a curious habit of wearing his stars on both the back and front of his helmet, which added to his reputation as an eccentric. (A book about him was titled ''The General Who Wore Six Stars'' because of this habit; it was not that Lee earned an actual rank of 6-star general.) Lee was often called "Jesus Christ Himself" based on his initials. He was also known as "Court House" and "Church House" Lee.

The logistical arrangements for

The logistical arrangements for D-Day

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during the Second World War. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

proceeded well, although the initial advance was much slower than anticipated, and casualties and ammunition expenditure were high. In the lead up to Operation Cobra

Operation Cobra was an offensive launched by the First United States Army under Lieutenant General Omar Bradley seven weeks after the D-Day landings, during the Normandy campaign of World War II. The intention was to take advantage of the dis ...

, the breakout from Normandy, Com Z's Advance Section took over responsibility for the depots and installations in Normandy, except for the fuel dumps.

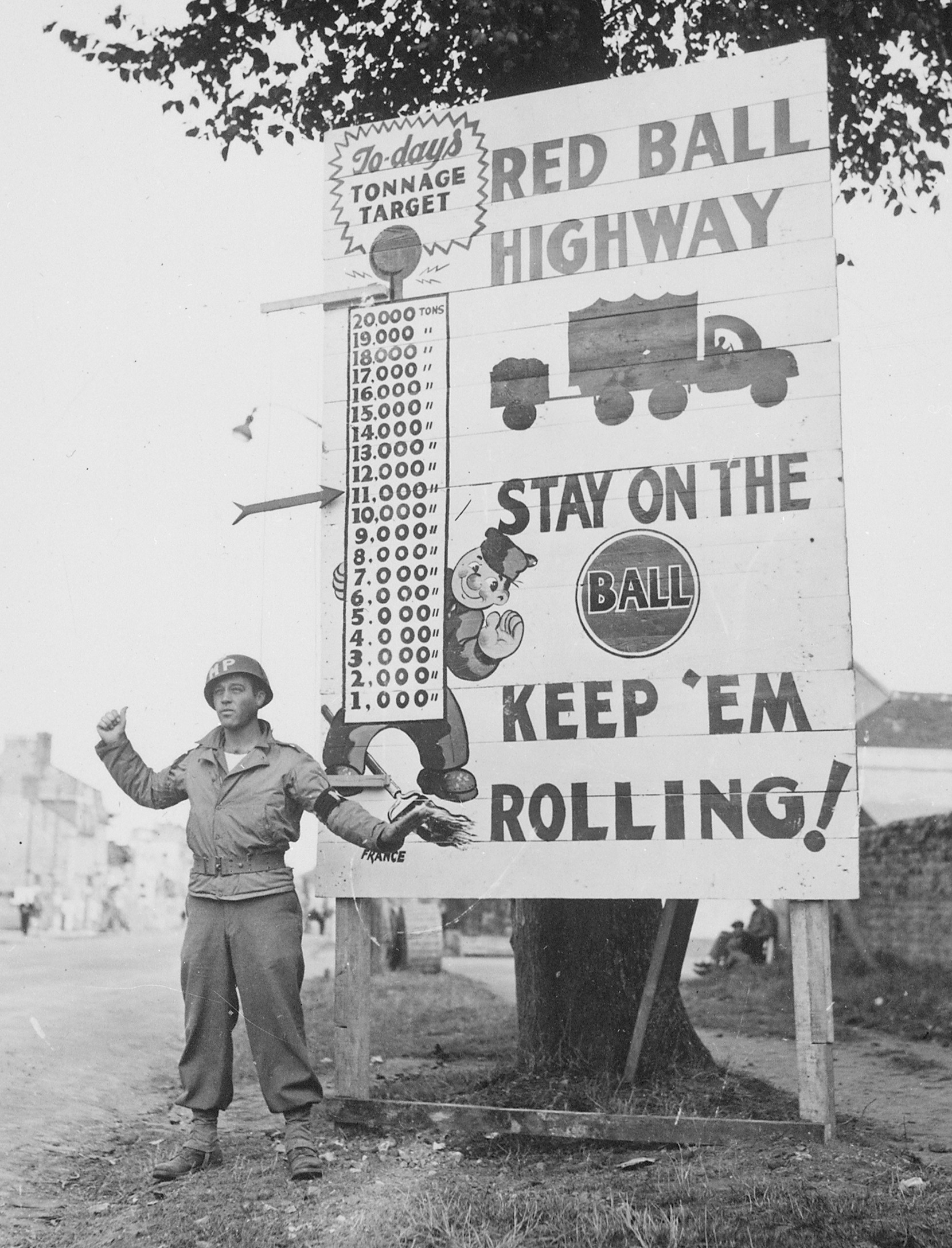

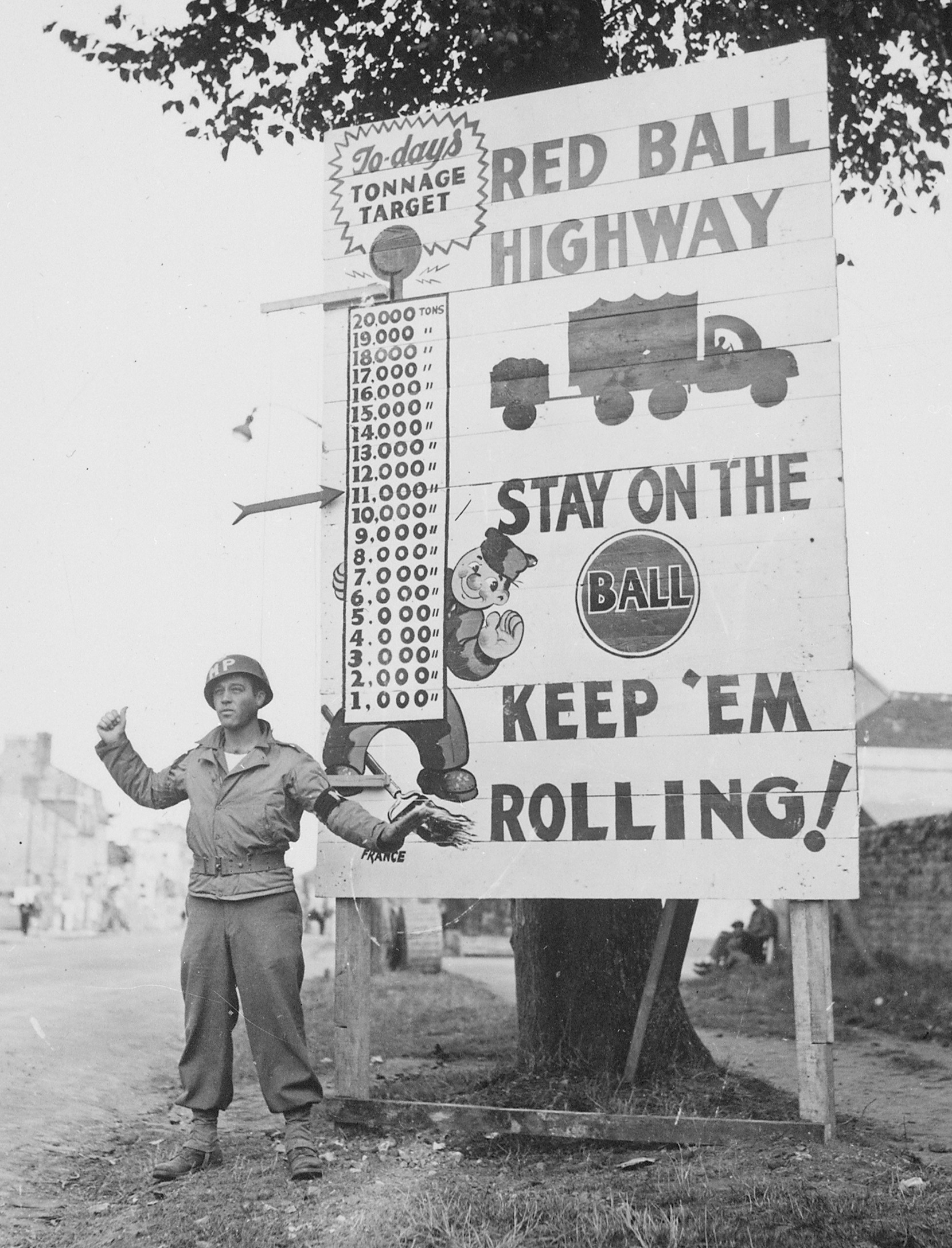

During the subsequent pursuit across France and Belgium the advance was much faster than forecast. There was no time to establish intermediate supply dumps. Lee improvised with the road transport, the Red Ball Express

The Red Ball Express was an American truck convoy system that supplied World War II allies, Allied forces moving through Europe after breaking out from the D-Day beaches in Normandy in the summer of 1944. To expedite cargo shipments to the fro ...

, but logistic support of the armies depended on the repair of the railroad system, and the development of ports. The original plans to use ports in Brittany were abandoned in favor of Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

in the south, and Le Havre

Le Havre is a major port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy (administrative region), Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the Seine, river Seine on the English Channel, Channe ...

and Antwerp

Antwerp (; ; ) is a City status in Belgium, city and a Municipalities of Belgium, municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of Antwerp Province, and the third-largest city in Belgium by area at , after ...

, which were captured by the British 21st Army Group

The 21st Army Group was a British headquarters formation formed during the Second World War. It controlled two field armies and other supporting units, consisting primarily of the British Second Army and the First Canadian Army. Established ...

.

In August, Com Z Headquarters moved from the UK to a camp at Valognes in France.

Although Eisenhower had expressed a desire that headquarters not be located in Paris, on 1 September Lee decided to move Com Z headquarters there. This involved the movement of 8,000 officers and 21,000 enlisted men from the UK and Valognes, and took two weeks to accomplish at a time when there were severe supply shortages. Eventually, Com Z occupied 167 hotels in Paris, the Seine Base Section headquarters occupied 129 more, and SHAEF occupied another 25. Lee established his own official residence in the Hotel George V. The front of the building was kept clear for his own vehicle. He justified the move to Paris on the grounds that Paris was the hub of France's road, rail and inland waterway communications networks. The logic was conceded, but the use of scarce fuel and transport resources at a critical time caused embarrassment.

During the German Ardennes Offensive

The Ardennes ( ; ; ; ; ), also known as the Ardennes Forest or Forest of Ardennes, is a region of extensive forests, rough terrain, rolling hills and ridges primarily in Belgium and Luxembourg, extending into Germany and France.

Geological ...

, Lee deployed service troops, particularly engineers to help delay the German advance while other Com Z troops shifted supply dumps in the path of the German advance to safer locations in the rear, thereby denying the Germans access to captured American fuel supplies. Some of fuel were moved.

Lee's challenge to army racial policy

During October, Bradley incurred very heavy casualties in fighting in theBattle of Aachen

The Battle of Aachen was a battle of World War II, fought by American and German forces in and around Aachen, Germany, between 12 September and 21 October 1944. The city had been incorporated into the Siegfried Line, the main defensive network ...

and the Battle of Hürtgen Forest

The Battle of Hürtgen Forest () was a series of battles fought from 19 September to 16 December 1944, between United States Armed Forces, American and Wehrmacht, German forces on the Western Front (World War II), Western Front during World War ...

in October and November. This resulted in a critical shortage of infantry replacements even before the crisis situation created by the Ardennes Offensive. Noting that casualties among newly arrived reinforcements greatly exceeded those among veterans, Lee tried to humanize the replacement depots, and suggested changing the name so that they sounded less like spare parts. Bradley opposed this, arguing for more substantial changes.

One source of infantry reinforcements was Com Z. Lee suggested that physically fit African-American soldiers in the Communications Zone, providing their jobs could be filled by limited-duty personnel, should be allowed to volunteer for infantry duty, and be placed in otherwise white units, without regard to a quota but on an as-needed basis. He wrote: "It is planned to assign you without regard to color or race".

Walter Bedell Smith disagreed with Lee's plan, writing to Eisenhower:

Reflecting the prevalent racial prejudices of most US Army officers at the time, Smith did not believe Black troops capable of combat duty. His opinion was that a one-for-one replacement should not be attempted; only replacements as full platoon

A platoon is a Military organization, military unit typically composed of two to four squads, Section (military unit), sections, or patrols. Platoon organization varies depending on the country and the Military branch, branch, but a platoon can ...

s of Black soldiers. As a result of the directive 2,500 volunteers were organized into 53 rifle platoons, and sent to the front, to be distributed as needed to companies. In the 12th Army Group they were attached to regiments, while in the 6th Army Group the platoons were grouped into companies

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of legal people, whether natural, juridical or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specifi ...

attached to the division. The former arrangement were generally better rated by the units they were attached to, because the Negro platoons had no company-level unit training.

Lee featured in the 1943 US Army training film '' A Welcome to Britain'', where he was involved in a sequence involving a British woman inviting a colored GI to tea. The narrator focused on Lee's family's background with the Confederacy and Lee took the opportunity to encourage American soldiers to treat black and white soldiers the same.

Post-war career

AfterVE Day

Victory in Europe Day is the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, 8 May 1945; it marked the official surrender of all German military operations ...

, the Communications Zone became Theater Service Forces, and Lee moved his headquarters to Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

in June 1945. In December 1945, he succeeded Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgway as Deputy Theater Commander and Commander, Mediterranean Theater of Operations

The Mediterranean Theater of Operations, United States Army (MTOUSA), originally called the North African Theater of Operations, United States Army (NATOUSA), was a military formation of the United States Army that supervised all U.S. Army for ...

, United States Army (MTOUSA) in Italy. He worked closely with the theater commander, British lieutenant general Sir William Duthie Morgan until January 1946, when Morgan was appointed the Army member of the British Joint Staff Mission in Washington, D.C.

Lee then became theater commander as well as MTOUSA commander. He was responsible for the maintenance and repatriation of hundreds of thousands of American service men and women, opened the Sicily–Rome American Cemetery and Memorial, and restored infrastructure of many of the nations surrounding the Mediterranean. The Allied Occupation of Italy ended when the Peace Treaty with Italy went into effect in September 1947, and Lee returned to the United States.

In August 1947 newspaper columnist Robert C. Ruark said General Lee misused enlisted men under his command in occupied Italy. Ruark vowed "I am going to blow a loud whistle on Lieutenant General John C. H. Lee", and published a series of articles critical of Lee's command, quoting several disgruntled soldiers. Some suggested Ruark was unhappy because a journalist's train had left him behind and Lee would not provide secondary transportation for him. Subsequently, Lee requested that his command be thoroughly investigated by the Office of the Inspector General

In the United States, Office of Inspector General (OIG) is a generic term for the oversight division of a List of federal agencies in the United States, federal or state agency aimed at preventing inefficient or unlawful operations within their p ...

. Lee and his command were exonerated in a report by Major General Ira T. Wyche, which was issued in October 1947.

Retirement and honors

After 38 years of active service, Lee retired from the army on 31 December 1947 at thePresidio of San Francisco

The Presidio of San Francisco (originally, El Presidio Real de San Francisco or The Royal Fortress of Saint Francis) is a park and former U.S. Army post on the northern tip of the San Francisco Peninsula in San Francisco, California, and is part ...

. He received many honors and awards for his services, including the Army Distinguished Service Medal

The Distinguished Service Medal (DSM) is a military decoration of the United States Army that is presented to soldiers who have distinguished themselves by exceptionally meritorious service to the government in a duty of great responsibility. ...

, the Navy Distinguished Service Medal

The Navy Distinguished Service Medal is a military decoration of the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps which was first created in 1919 and is presented to Sailors and Marines to recognize distinguished and exceptionally meritorio ...

, the Silver Star

The Silver Star Medal (SSM) is the United States Armed Forces' third-highest military decoration for valor in combat. The Silver Star Medal is awarded primarily to members of the United States Armed Forces for gallantry in action against a ...

, and the Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit (LOM) is a Awards and decorations of the United States military, military award of the United States Armed Forces that is given for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievemen ...

. Foreign awards included being made an honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding valuable service in a wide range of useful activities. It comprises five classes of awards across both civil and military divisions, the most senior two o ...

by the UK, and a Grand Officer of the Legion of Honor

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and civil. Currently consisting of five classes, it was ...

, Commander of the Order of Merit Maritime and a Commander of the Order of Merite Agricole by France, which also awarded him the Croix de Guerre

The (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awarded during World ...

for his WWI service.

Belgium made Lee a Grand Officer of the Order of the Crown and awarded him its Croix de Guerre

The (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awarded during World ...

. He received the Grand Cross of the Order of the Oak Crown

The Order of the Oak Crown (, , ) is an order (honour), order of the Luxembourg, Grand Duchy of Luxembourg.

History

The Order of the Oak Crown was established in 1841 by William II of the Netherlands, Grand Duke William II, who was also King o ...

and the Croix de Guerre

The (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awarded during World ...

from Luxembourg, which also made him a Grand Officer of the Order of Adolph of Nassau. Italy made him a Grand Cordon of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus

The Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus () (abbreviated OSSML) is a Roman Catholic dynastic order of knighthood bestowed by the royal House of Savoy. It is the second-oldest order of knighthood in the world, tracing its lineage to AD 1098, a ...

and a member of the Military Order of Italy, and he received the Papal Lateran Cross from the Vatican.

In addition, Lee was made an honorary member of the French Foreign Legion

The French Foreign Legion (, also known simply as , "the Legion") is a corps of the French Army created to allow List of militaries that recruit foreigners, foreign nationals into French service. The Legion was founded in 1831 and today consis ...

, the II Polish Corps, the Italian Bersaglieri and several Alpini

The Alpini are the Italian Army's specialist mountain infantry. Part of the army's infantry corps, the speciality distinguished itself in combat during World War I and World War II. Currently the active Alpini units are organized in two operati ...

Regiments. He was declared an honorary Citizen of Cherbourg

Cherbourg is a former Communes of France, commune and Subprefectures in France, subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French departments of France, department of Manche. It was merged into the com ...

in France, and Antwerp and Liège

Liège ( ; ; ; ; ) is a City status in Belgium, city and Municipalities in Belgium, municipality of Wallonia, and the capital of the Liège Province, province of Liège, Belgium. The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east o ...

in Belgium, was given the school tie of Cheltenham College

Cheltenham College is a public school ( fee-charging boarding and day school for pupils aged 13–18) in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England. The school opened in 1841 as a Church of England foundation and is known for its outstanding linguis ...

in England, and awarded an honorary doctor of law

A Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) is a doctoral degree in legal studies. The abbreviation LL.D. stands for ''Legum Doctor'', with the double “L” in the abbreviation referring to the early practice in the University of Cambridge to teach both canon law ...

degree from the University of Bristol

The University of Bristol is a public university, public research university in Bristol, England. It received its royal charter in 1909, although it can trace its roots to a Merchant Venturers' school founded in 1595 and University College, Br ...

.

Lee was an Episcopalian and kept a Bible with him at all times. He declined post-war invitations to serve as a corporate board executive, preferring to devote his life to service. In retirement he spent his last eleven years leading the Brotherhood of St. Andrew, a lay organization of the Episcopal Church, as executive vice president from 1948 to 1950, and then as its president.

Death and legacy

Lee's first wife Sarah died in a motor vehicle accident in 1939, and he remarried on 19 September 1945 to Eve Brookie Ellis, whom he also survived. He died inYork, Pennsylvania

York is a city in York County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. Located in South Central Pennsylvania, the city's population was 44,800 at the time of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of cities in ...

, on 30 August 1958, aged 71, and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is the largest cemetery in the United States National Cemetery System, one of two maintained by the United States Army. More than 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington County, Virginia.

...

beside his first wife.

There is a large portrait of General Lee in the West Point Club at the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

.

Reputation

In his wartime memoir, '' Crusade in Europe'', Eisenhower described Lee as: Official historian Roland G. Ruppenthal wrote: Stephen Ambrose wrote in '' Citizen Soldiers'':Decorations

Dates of rank

Notes

References

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Generals of World War II

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lee, John C. H. 1887 births 1958 deaths United States Army Corps of Engineers personnel People from Junction City, Kansas Military personnel from Kansas American military personnel of World War I Burials at Arlington National Cemetery United States Military Academy alumni Recipients of the Silver Star Recipients of the Legion of Merit Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Recipients of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal Honorary Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire American recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France) American recipients of the Croix de guerre (Belgium) Recipients of the Order of Agricultural Merit United States Army generals of World War II United States Army generals United States Army personnel of World War I