John Bingham (scientist) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Armor Bingham (January 21, 1815 – March 19, 1900) was an American politician who served as a Republican representative from

The following month, the capital fell into chaos as

The following month, the capital fell into chaos as

Bingham continued his career as a representative and was reelected to the 40th, 41st and 42nd Congresses. He served as chairman of the Committee on Claims from 1867 to 1869 and a member of the Committee on the Judiciary from 1869 to 1873.

Bingham continued his career as a representative and was reelected to the 40th, 41st and 42nd Congresses. He served as chairman of the Committee on Claims from 1867 to 1869 and a member of the Committee on the Judiciary from 1869 to 1873.

Guide to Research Collections

' where his papers are located.

"John Bingham and the 14th Amendment"

Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

and as the United States ambassador to Japan

The is the Ambassadors of the United States, ambassador from the United States of America to Japan.

History

Beginning in 1854 with the Convention of Kanagawa, use of gunboat diplomacy by Commodore (United States), Commodore Matthew C. Perry, ...

. In his time as a congressman, Bingham served as both assistant Judge Advocate General in the trial of the Abraham Lincoln assassination

On April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, was shot by John Wilkes Booth while attending the play ''Our American Cousin'' at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C. Shot in the head as he watched the play, Linc ...

and a House manager

An impeachment manager is a legislator appointed to serve as a prosecutor in an impeachment trial. They are also often called "House managers" or "House impeachment manager" when appointed from a legislative chamber that is called a "House of Repr ...

(prosecutor

A prosecutor is a legal representative of the prosecution in states with either the adversarial system, which is adopted in common law, or inquisitorial system, which is adopted in Civil law (legal system), civil law. The prosecution is the ...

) in the impeachment trial

An impeachment trial is a trial that functions as a component of an impeachment. Several governments utilize impeachment trials as a part of their processes for impeachment. Differences exist between governments as to what stage trials take place ...

of U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

. He was also the principal framer of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment (Amendment XIV) to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments. Considered one of the most consequential amendments, it addresses Citizenship of the United States ...

.

Early life and education

Born inMercer County, Pennsylvania

Mercer County is a County (United States), county in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 110,652. Its county seat is Mercer, Pennsylvania, Mercer, and ...

, where his carpenter and bricklayer father Hugh had moved after service in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

, Bingham attended local public schools. After his mother's death in 1827, his father remarried. John moved west to Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

to live with his merchant uncle Thomas after clashing with his new stepmother. He apprenticed

Apprenticeship is a system for training a potential new practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study. Apprenticeships may also enable practitioners to gain a license to practice in a regulate ...

as a printer for two years, helping to publish the ''Luminary'', an anti-Masonic

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

newspaper. He then returned to Pennsylvania to study at Mercer College and then studied law at Franklin College in New Athens, Harrison County, Ohio

Harrison County is a county located in the U.S. state of Ohio. As of the 2020 census, the population was 14,483, making it the fifth-least populous county in Ohio. Its county seat and largest village is Cadiz. The county is named for Genera ...

. There, Bingham befriended former slave Titus Basfield, who became the first African-American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

to graduate college in Ohio. They continued to correspond for many years.

Hugh and Thomas Bingham were longtime abolitionists who were both active in local politics. They initially allied with the Anti-Masonic Party

The Anti-Masonic Party was the earliest Third party (United States), third party in the United States. Formally a Single-issue politics, single-issue party, it strongly opposed Freemasonry in the United States. It was active from the late 1820s, ...

, led in Pennsylvania by Governor Joseph Ritner

Joseph Ritner (March 25, 1780 – October 16, 1869) was the eighth governor of Pennsylvania, and was a member of the Anti-Masonic Party. Elected governor during the 1835 Pennsylvania gubernatorial election, he served from 1835 to 1839.

Controv ...

and state representative Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was an American politician and lawyer who served as a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, being one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Histo ...

. Hugh became clerk of the Mercer County court and later a perennial Whig candidate in the county known for opposing war with Mexico. Matthew Simpson

Matthew Simpson (June 21, 1811 – June 18, 1884) was an American bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, elected in 1852 and based mainly in Philadelphia. During the Reconstruction Era after the Civil War, most evangelical denominations in ...

, Bingham's longtime friend since childhood, became a bishop in the Methodist Episcopal Church

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself nationally. In 1939, th ...

and urged President Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War, defeating the Confederate State ...

to issue the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the eff ...

. Following Lincoln's assassination, Simpson delivered a prayer at the White House and a funeral oration at the interment ceremony in Springfield, Illinois

Springfield is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Illinois. Its population was 114,394 at the 2020 United States census, which makes it the state's List of cities in Illinois, seventh-most populous cit ...

.

Early legal career

After graduation, Bingham returned toMercer, Pennsylvania

Mercer is a borough in Mercer County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. The population was 1,982 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Hermitage micropolitan area.

The community was named after Brigadier General Hugh Mercer. ...

, to read law with John James Pearson and William Stewart, and he was admitted to the Pennsylvania bar on March 25, 1840, and the Ohio bar by year's end. Bingham then returned to Cadiz, Ohio

Cadiz ( ) is a village in Harrison County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. The population was 3,051 at the 2020 census.

History

Cadiz was founded in 1803 at the junction of westward roads from Pittsburgh and Washington, Pennsylvania ...

, to begin his legal and political career. An active Whig, Bingham campaigned for President William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was the ninth president of the United States, serving from March 4 to April 4, 1841, the shortest presidency in U.S. history. He was also the first U.S. president to die in office, causin ...

. His uncle, Thomas, a prominent Presbyterian in the area, had served as associate judge in the Harrison County Court of Common Pleas from 1825 to 1839. The young lawyer's practice extended to Tuscarawas County, Ohio

Tuscarawas County ( ) is a county located in the northeastern part of the U.S. state of Ohio. As of the 2020 census, the population was 93,263. Its county seat is New Philadelphia. Its name is a Delaware Indian word variously translated as "o ...

, and its seat, New Philadelphia. In 1846, Bingham won his first election as district attorney for Tuscarawas County, serving from 1846 to 1849.

Early political career

Bingham's political activity continued despite the Whig Party's decline. Campaigning as candidate of theOpposition Party

In politics, the opposition comprises one or more political parties or other organized groups that are opposed to the government (or, in American English, the administration), party or group in political control of a city, region, state, coun ...

, he was elected to the 34th Congress, representing the 21st congressional district. In Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, he roomed at the same boarding house as did fellow Ohio representative Joshua Giddings Joshua Giddings may refer to:

* Joshua Reed Giddings (1795–1864), American attorney, politician, and abolitionist

* Joshua Giddings (cyclist) (born 2003), British track and road cyclist

{{hndis, Giddings, Joshua ...

, a prominent abolitionist whom Bingham admired. Voters reelected Bingham to the 35th Military units

*35th Fighter Wing, an air combat unit of the United States Air Force

*35th Infantry Division (United States), a formation of the National Guard since World War I

*35th Infantry Regiment (United States), a regiment created on 1 July 1 ...

, 36th and 37th Congresses as a Republican. However, the district was one of two Ohio districts eliminated in the redistricting following the census of 1860. Bingham thus ran for reelection in what became the 16th district. Known for his abolitionist views, he lost to Democratic peace candidate Joseph W. White, and thus failed to return for the 38th Congress, in part because Union soldiers (mostly Republican-leaning) who were away from home fighting in the war were not allowed to vote by mail in Ohio. Nonetheless, the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

appointed Bingham as one of the managers of impeachment proceedings against West Hughes Humphreys

West Hughes Humphreys (August 26, 1806 – October 16, 1882) was the 3rd Attorney General of Tennessee and a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee, the United States District Court ...

.

During the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, Bingham strongly supported the Union and became known as a Radical Republican

The Radical Republicans were a political faction within the Republican Party originating from the party's founding in 1854—some six years before the Civil War—until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reconstruction. They ca ...

. President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

appointed him Judge Advocate

Judge-advocates are military lawyers serving in different capacities in the military justice systems of different jurisdictions.

Australia

The Australian Army Legal Corps (AALC) consists of Regular and Reserve commissioned officers that prov ...

of the Union Army with the rank of major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

during his hiatus from Congress, and Bingham briefly became solicitor of the United States Court of Claims

The Court of Claims was a federal court that heard claims against the United States government. It was established in 1855, renamed in 1948 to the United States Court of Claims (), and abolished in 1982. Then, its jurisdiction was assumed by the n ...

in 1865. Bingham's judge advocate service was exceptional in the sense that he was a prosecutor or appellate reviewer in three significant military trials. He oversaw critical aspects of the trials of General Fitz John Porter in 1863, Surgeon General

Surgeon general (: surgeons general) is a title used in several Commonwealth countries and most NATO nations to refer either to a senior military medical officer or to a senior uniformed physician commissioned by the government and entrusted with p ...

William Hammond in 1864 and the military commission trial of the Lincoln assassination conspirators in 1864.

United States House of Representatives

Bingham defeated incumbent congressman Joseph Worthington White in the next congressional election. For this election, Ohio had changed its law and now allowed soldiers away from home to vote by mail. Bingham returned to serve in the39th Congress

The 39th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C., from March 4, 1865 ...

, which first met on March 4, 1865.

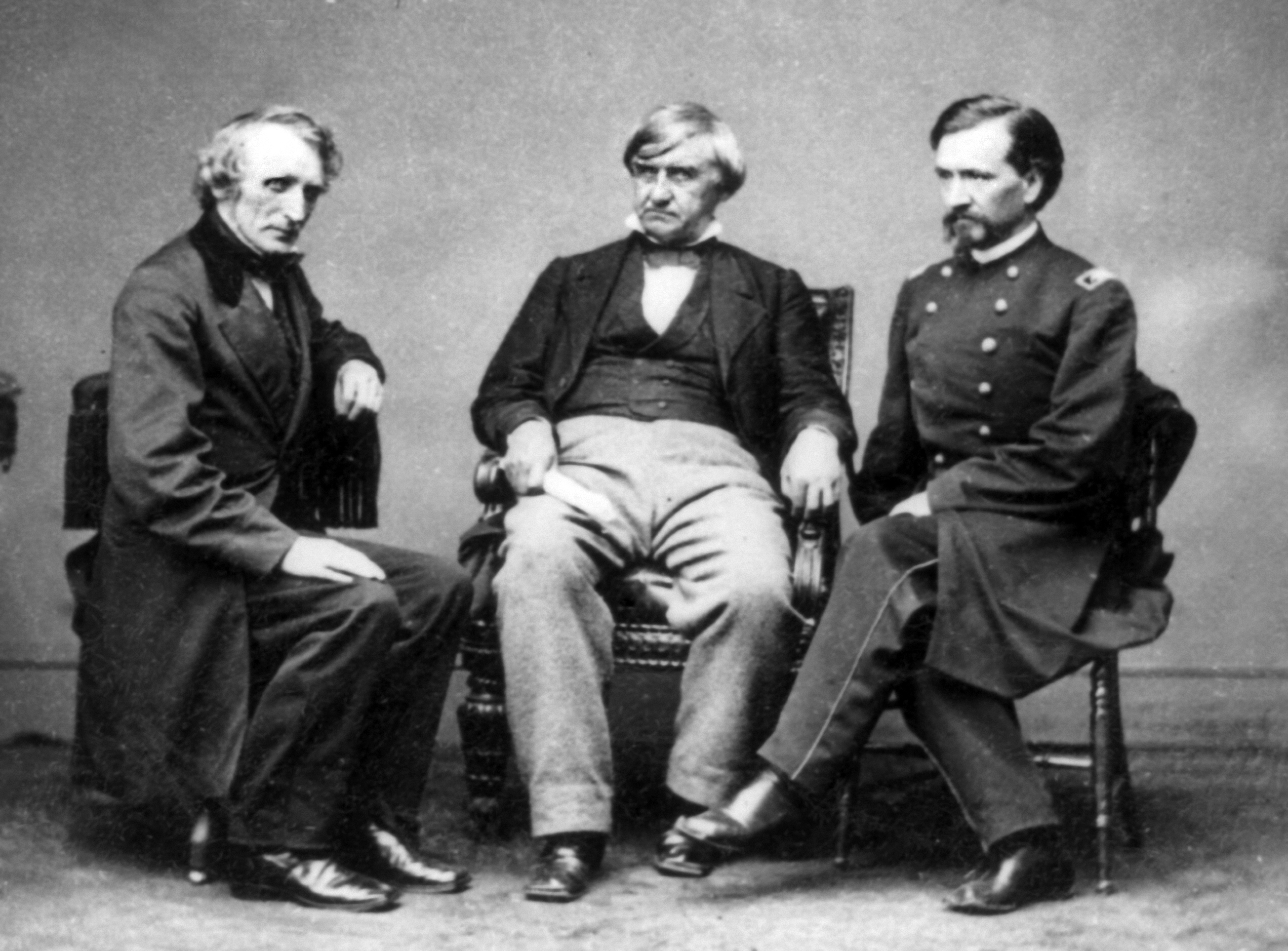

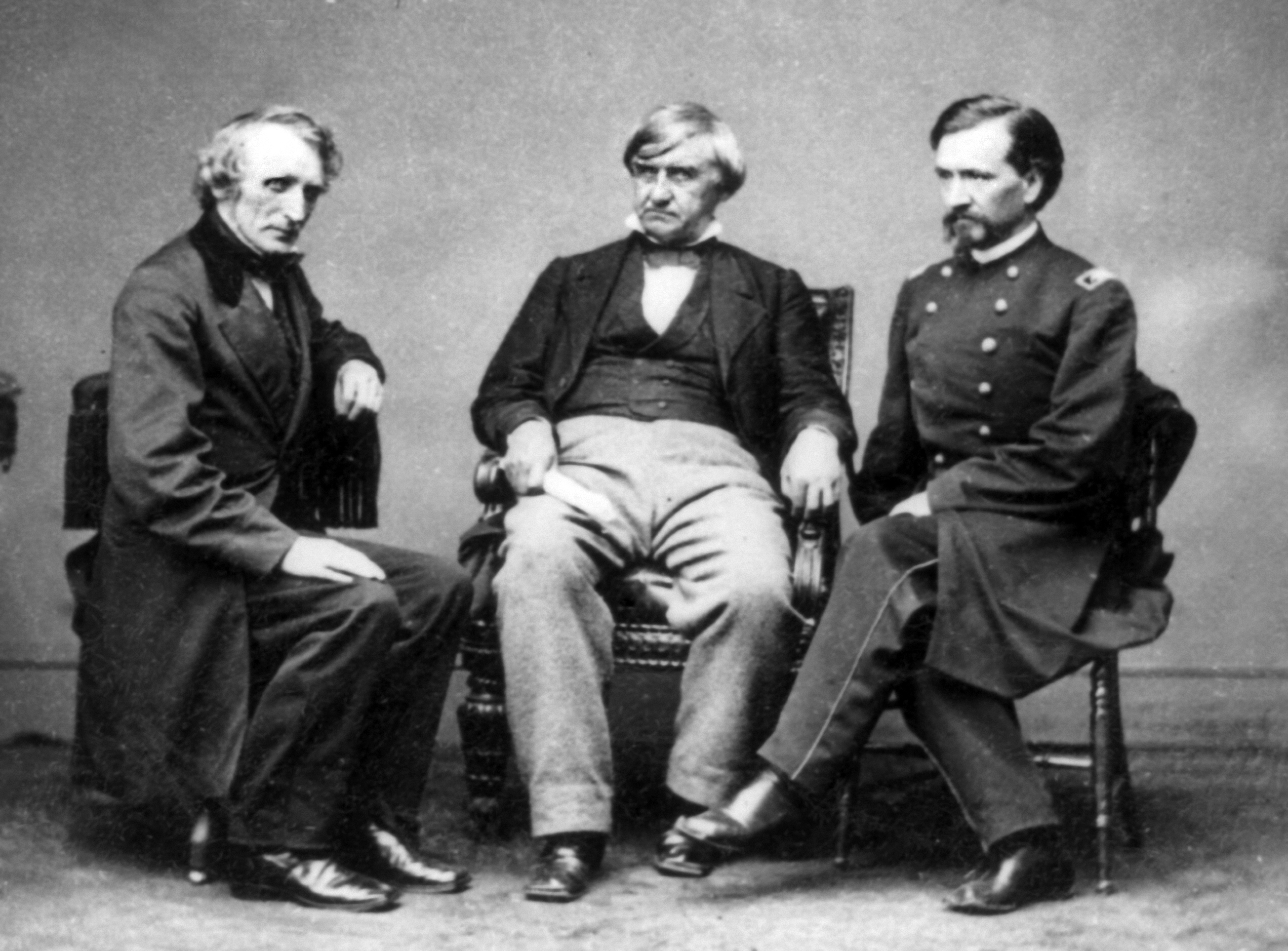

Lincoln assassination trial

The following month, the capital fell into chaos as

The following month, the capital fell into chaos as John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, assassinated United States president Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the p ...

assassinated President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

, and Booth's co-conspirator Lewis Powell severely injured Secretary of State William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (; May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States senator. A determined opp ...

on the night of April 14, 1865. Booth died on April 26, 1865, from a gunshot wound. When the trials for the conspirators were ready to start, Bingham's old friend from Cadiz, Edwin Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. Secretary of War, U.S. secretary of war under the Lincoln Administration during most of the American Civil War. Stanton's manag ...

, appointed him to serve as Assistant Judge Advocate General along with General Henry Burnett, another Assistant Judge Advocate General, and Joseph Holt

Joseph Holt (January 6, 1807 – August 1, 1894) was an American lawyer, soldier, and politician. As a leading member of the James Buchanan#Administration and Cabinet, Buchanan administration, he succeeded in convincing Buchanan to oppose the ...

, the Judge Advocate General.

The accused conspirators were George Atzerodt

George Andrew Atzerodt (June 12, 1835 – July 7, 1865) was a German American repairman, Confederate sympathizer, and conspirator in the assassination of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln. He was assigned to assassinate Vice President And ...

, David Herold

David Edgar Herold (June 16, 1842 – July 7, 1865) was an American pharmacist's assistant and accomplice of John Wilkes Booth in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865. After the shooting, Herold accompanied Booth to the home o ...

, Lewis Powell (Paine), Samuel Arnold, Michael O'Laughlen

Michael O'Laughlen, Jr. (pronounced ''Oh-Lock-Lun''; June 3, 1840 – September 23, 1867) was an American Confederate States Army, Confederate soldier and conspirator in John Wilkes Booth's plot to kidnap U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, and later ...

, Edman Spangler

Edman "Ned" Spangler (August 10, 1825 – February 7, 1875), baptized Edmund Spangler, was an American carpenter and stagehand who was employed at Ford's Theatre at the time of President Abraham Lincoln's murder on April 14, 1865. He and ...

, Samuel Mudd

Samuel Alexander Mudd Sr. (December 20, 1833 – January 10, 1883) was an American physician who was imprisoned for conspiring with John Wilkes Booth concerning the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

Mudd worked as a doctor and tobacco far ...

and Mary Surratt

Mary Elizabeth Surratt (; 1820 or May 1823 – July 7, 1865) was an American boarding house owner in Washington, D.C., who was convicted of taking part in the conspiracy which led to the assassination of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln in 18 ...

. The trial began on May 10, 1865. On June 29, 1865, the eight were found guilty for their involvement in the conspiracy to kill the president. Spangler was sentenced to six years in prison, Arnold, O'Laughlen and Mudd were sentenced to life in prison and Atzerodt, Herold, Powell and Surratt were sentenced to hang. They were executed July 7, 1865. Surratt was the first woman in American history to be executed by the Federal government of the United States

The Federal Government of the United States of America (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the Federation#Federal governments, national government of the United States.

The U.S. federal government is composed of three distinct ...

. O'Laughlen died in prison in 1867. Arnold, Spangler and Mudd were pardoned by President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

in early 1869.

Fourteenth Amendment

In 1866, during the39th Congress

The 39th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C., from March 4, 1865 ...

, Bingham was appointed to a subcommittee of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction

The Joint Committee on Reconstruction, also known as the Joint Committee of Fifteen, was a joint committee of the 39th United States Congress that played a major role in Reconstruction in the wake of the American Civil War. It was created to "in ...

tasked with considering suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

proposals. Bingham submitted several versions of an amendment to the Constitution to apply the Bill of Rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pri ...

to the states. His final submission, which was accepted by the committee on April 28, 1866, read, "No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." The committee recommended that the language become Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment (Amendment XIV) to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments. Considered one of the most consequential amendments, it addresses Citizenship of the United States ...

. It was introduced in the spring of 1866, passing both houses by June 1866.

In the closing debate in the House, Bingham stated:

Except for the addition of the first sentence of Section 1, which defined citizenship, the amendment weathered the Senate debate without substantial change. The Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868.

Despite Bingham's likely intention for the Fourteenth Amendment to apply the first eight amendments of the Bill of Rights to the states, the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

declined to interpret it that way in the Slaughter-House Cases

The ''Slaughter-House Cases'', 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36 (1873), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision which ruled that the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution only protects the legal rights t ...

and in ''United States v. Cruikshank

''United States v. Cruikshank'', 92 U.S. 542 (1876), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court ruling that the U.S. Bill of Rights did not limit the power of private actors or state governments despite the adoption of the Fo ...

''. In the 1947 case of ''Adamson v. California

''Adamson v. California'', 332 U.S. 46 (1947), was a United States Supreme Court case regarding the incorporation of the Fifth Amendment of the Bill of Rights. Its decision is part of a long line of cases that eventually led to the Selective ...

'', Supreme Court justice Hugo Black

Hugo Lafayette Black (February 27, 1886 – September 25, 1971) was an American lawyer, politician, and jurist who served as a U.S. Senator from Alabama from 1927 to 1937 and as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, ass ...

argued in his dissent that the framers' intent should control the court's interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment, and he attached a lengthy appendix that quoted extensively from Bingham's congressional testimony. Though the Adamson Court declined to adopt Black's interpretation, the court over the next 25 years used a doctrine of selective incorporation

In United States constitutional law, incorporation is the doctrine by which portions of the Bill of Rights have been made applicable to the states. When the Bill of Rights was ratified, the courts held that its protections extended only to the a ...

to extend to application against the states the protections in the Bill of Rights as well as other unenumerated rights.

Ohio ratified the Fourteenth Amendment on January 4, 1867, but Bingham continued to explain its extension of citizenship during the fall election season. The Fourteenth Amendment has vastly expanded civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

protections and has come to be cited in more litigation than any other amendment to the Constitution. In retrospect The National Constitution Center

The National Constitution Center is a non-profit institution that is devoted to the study of the Constitution of the United States. Located at the Independence Mall (Philadelphia), Independence Mall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the center is a ...

described John Bingham as "a leading Republican in the U.S. House of Representatives during Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

and the primary author of Section 1 of the 14th Amendment. This key provision wrote the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

’s promise of freedom and equality into the Constitution. Because of Bingham’s crucial role in framing this constitutional text, Justice Hugo Black

Hugo Lafayette Black (February 27, 1886 – September 25, 1971) was an American lawyer, politician, and jurist who served as a U.S. Senator from Alabama from 1927 to 1937 and as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, ass ...

would later describe him as the 14th Amendment’s James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

." It hailed him as "Second Founder

Founder or Founders may refer to:

Places

*Founders Park, a stadium in South Carolina, formerly known as Carolina Stadium

* Founders Park, a waterside park in Islamorada, Florida

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Founders (''Star Trek''), the ali ...

who most worked to realize the universal promise of Madison Madison may refer to:

People

* Madison (name), a given name and a surname

* James Madison (1751–1836), fourth president of the United States

* Madison (footballer), Brazilian footballer

Places in the United States

Populated places

* Madi ...

’s Bill

Bill(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

* Banknote, paper cash (especially in the United States)

* Bill (law), a proposed law put before a legislature

* Invoice, commercial document issued by a seller to a buyer

* Bill, a bird or animal's beak

Pl ...

and Jefferson

Jefferson may refer to:

Names

* Jefferson (surname)

* Jefferson (given name)

People

* Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), third president of the United States

* Jefferson (footballer)

* Jefferson (singer) or Geoff Turton (born 1944), British s ...

’s Declaration."

Later congressional career

Bingham continued his career as a representative and was reelected to the 40th, 41st and 42nd Congresses. He served as chairman of the Committee on Claims from 1867 to 1869 and a member of the Committee on the Judiciary from 1869 to 1873.

Bingham continued his career as a representative and was reelected to the 40th, 41st and 42nd Congresses. He served as chairman of the Committee on Claims from 1867 to 1869 and a member of the Committee on the Judiciary from 1869 to 1873.

Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

Bingham played a prominent role in combatting a number of early efforts byRadical Republicans

The Radical Republicans were a political faction within the Republican Party originating from the party's founding in 1854—some six years before the Civil War—until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reconstruction. They ca ...

to impeach

Impeachment is a process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In Euro ...

President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

.

On March 7, 1867, during House debate on a proposed amendment to a resolution renewing the first impeachment inquiry against Andrew Johnson

The first impeachment inquiry against Andrew Johnson was launched by a vote of the United States House of Representatives on January 7, 1867, to investigate the potential impeachment of the President of the United States, Andrew Johnson.

It wa ...

, Wilson was questioned by Benjamin Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (November 5, 1818 – January 11, 1893) was an American major general (United States), major general of the Union Army, politician, lawyer, and businessman from Massachusetts. Born in New Hampshire and raised in Lowell, ...

as to whether or not he supported impeaching President Johnson. Bingham responded by declaring that, unlike some individuals, he was opposed to impeaching before having testimony

Testimony is a solemn attestation as to the truth of a matter.

Etymology

The words "testimony" and "testify" both derive from the Latin word ''testis'', referring to the notion of a disinterested third-party witness.

Law

In the law, testimon ...

. After the inquiry recommended that the House impeach Johnson, on December 7, 1867, Bingham was in the sizable majority of House members present that voted against impeaching Johnson.

On February 24, 1868, Bingham voted to impeach Johnson when the House voted to do so after Johnson having moved to oust Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. secretary of war under the Lincoln Administration during most of the American Civil War. Stanton's management helped organize ...

in apparent disregard for the Tenure of Office Act. Bingham was voted to serve as one of the House managers

An impeachment manager is a legislator appointed to serve as a prosecutor in an impeachment trial. They are also often called "House managers" or "House impeachment manager" when appointed from a legislative chamber that is called a "House of Repr ...

(prosecutors) in the subsequent impeachment trial of President Johnson.

Failure to be reelected in 1872

Bingham was implicated in theCrédit Mobilier scandal

The Crédit Mobilier scandal () was a two-part fraud conducted from 1864 to 1867 by the Union Pacific Railroad and the Crédit Mobilier of America construction company in the building of the eastern portion of the first transcontinental railroad f ...

and in 1872, he lost the election. Three local Republican political bosses made a deal to cut Bingham out, instead selecting Lorenzo Danford as the party's candidate. Thus, Danford came to represent the 16th district in the 43rd Congress and was reelected several times, but with a hiatus.

Minister to Japan

PresidentUlysses Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as commanding general, Grant led the Union Army to victory in the American Civil War ...

then appointed his ally Bingham as United States Minister

Diplomatic rank is a system of professional and social rank used in the world of diplomacy and international relations. A diplomat's rank determines many ceremonial details, such as the order of precedence at official processions, table seatings ...

to Japan, which involved a salary increase but also economic responsibilities with respect to the small legation. (The legation was upgraded to embassy status and the title of minister was upgraded to ambassador in the early 20th century.) Initially, Bingham tried to switch appointments with John Watson Foster

John Watson Foster (March 2, 1836 – November 15, 1917) was an American diplomat, military officer, lawyer and journalist who was U.S. secretary of state from 1892 to 1893, under President Benjamin Harrison. He was influential as a lawyer in te ...

of Indiana, whom Grant had appointed minister to Mexico, but Foster declined. Bingham thus sailed with his wife and two of his three daughters to Japan. Bingham served longer than any other minister to Japan, with his appointment spanning the terms of four Republican presidents from May 31, 1873, to July 2, 1885. His successor was appointed in 1885 by newly elected Democratic president Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

.

Bingham moved the embassy from an unsuitable location and replaced a problematic interpreter with a Presbyterian missionary from Ohio. He then managed to curtail the imperialistic ambitions of fellow Union veteran Charles Le Gendre

Charles William or Guillaum Joseph Émile Le Gendre (August 26, 1830– September 1, 1899) was a French-born American officer and diplomat who served as advisor to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Empire of Japan from 1872 to 1875 and as adv ...

. Bingham came to greatly respect Japanese culture, but he also presciently expressed his fear that Japan's military culture would hurt the country's development.

Bingham most prominently distinguished himself from other Western diplomats by fighting against the unequal treaties imposed upon Japan by Britain, particularly provisions for extraterritoriality and tariff control by Westerners. Initially, Bingham supported Japan's right to restrict hunting by foreigners to certain times and places and later its right to regulate incoming ships via quarantines to restrict the spread of cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

. Bingham later negotiated return of the Shimonoseki

file:141122 Shimonoseki City Hall Yamaguchi pref Japan01s3.jpg, 260px, Shimonoseki city hall

is a Cities of Japan, city located in Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 248,193 in 128,762 households and a pop ...

indemnity in 1877 as well as a revision of Japan's treaty with the United States in 1879, which restored some tariff autonomy to Japan, conditioned upon other treaties with Westerners.

Later life and death

Bingham was a delegate to the1888 Republican National Convention

The 1888 Republican National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held at the Auditorium Theatre in Chicago, Illinois, on June 19–25, 1888. It resulted in the nomination of former United States Senate, Senator Benjamin Harrison of ...

. In his later years, he was frequently interviewed by journalists on topics ranging from current events in Japan to his 1857 appointment of George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point ...

to the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

. He died in Cadiz on March 19, 1900, nine years after his wife Amanda had died. He was interred next to her in the Old Cadiz (Union) Cemetery in Cadiz.

Legacy

In 1901, Harrison County erected a bronze statue honoring Bingham in Cadiz."John Armor Bingham," Ohio Civil War Central, 2015, Ohio Civil War Central. 23 Jan 2015References

Sources

* Gerard N. Magliocca, ''American Founding Son: John Bingham and the Invention of the Fourteenth Amendment.'' New York: New York University Press, 2013. * Sam Kidder, ''Of One Blood All Nations: John Bingham: Ohio Congressman's Diplomatic Career in Meiji Japan (1873–1885)''. Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Piscataqua Press. 2020.External links

. IncludesGuide to Research Collections

' where his papers are located.

C-Span

Cable-Satellite Public Affairs Network (C-SPAN ) is an American Cable television in the United States, cable and Satellite television in the United States, satellite television network, created in 1979 by the cable television industry as a Non ...

(March 20, 2000).

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bingham, John A

1815 births

1900 deaths

People from Mercer, Pennsylvania

Politicians from Mercer County, Pennsylvania

Opposition Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Ohio

Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Ohio

People from Cadiz, Ohio

American abolitionists

Ohio lawyers

Union (American Civil War) political leaders

People of Ohio in the American Civil War

Franklin College (New Athens, Ohio)

Ambassadors of the United States to Japan

19th-century American diplomats

People associated with the assassination of Abraham Lincoln

Moderate Republicans (Reconstruction era)

19th-century members of the United States House of Representatives