John Bayard Anderson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

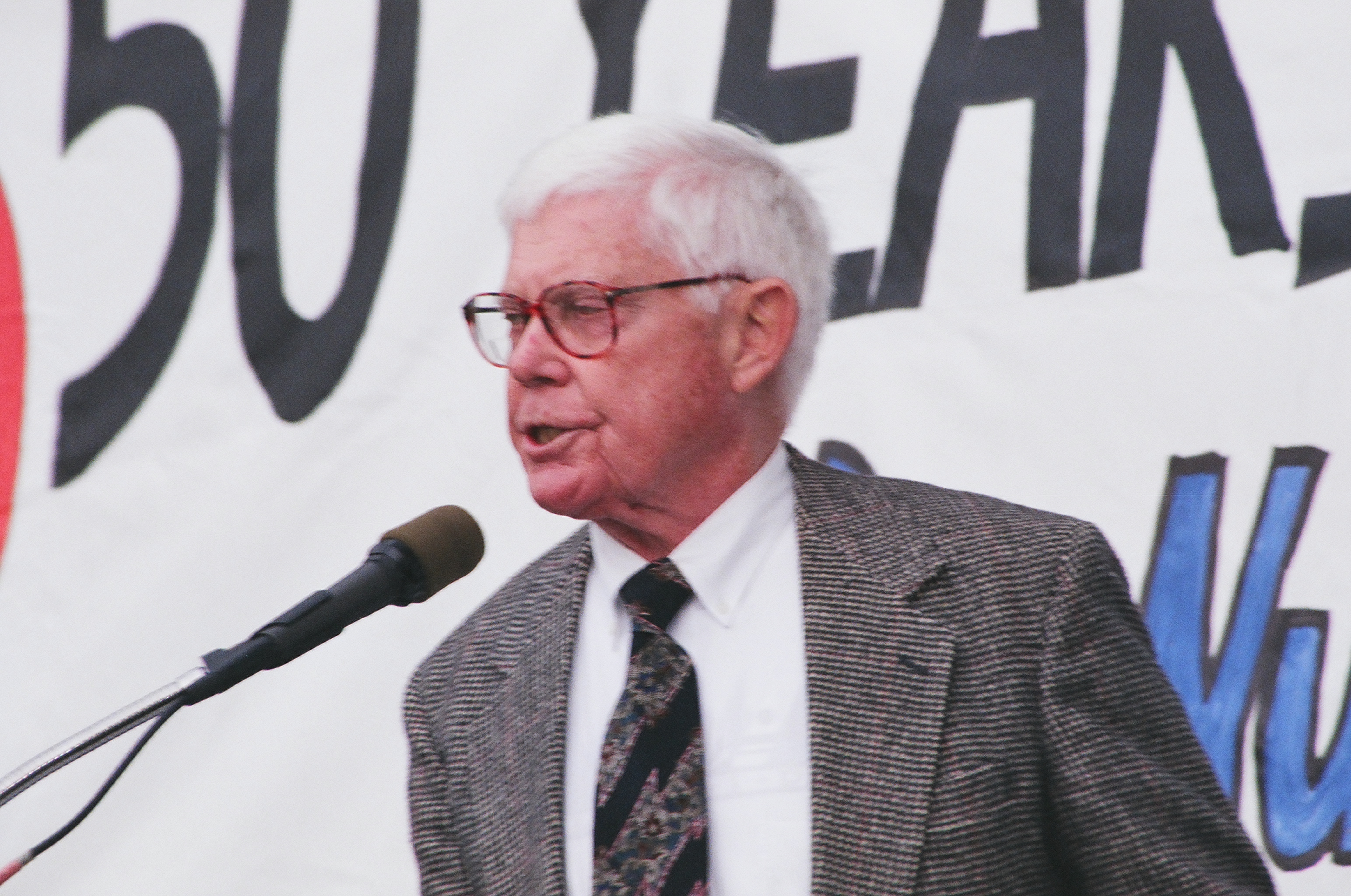

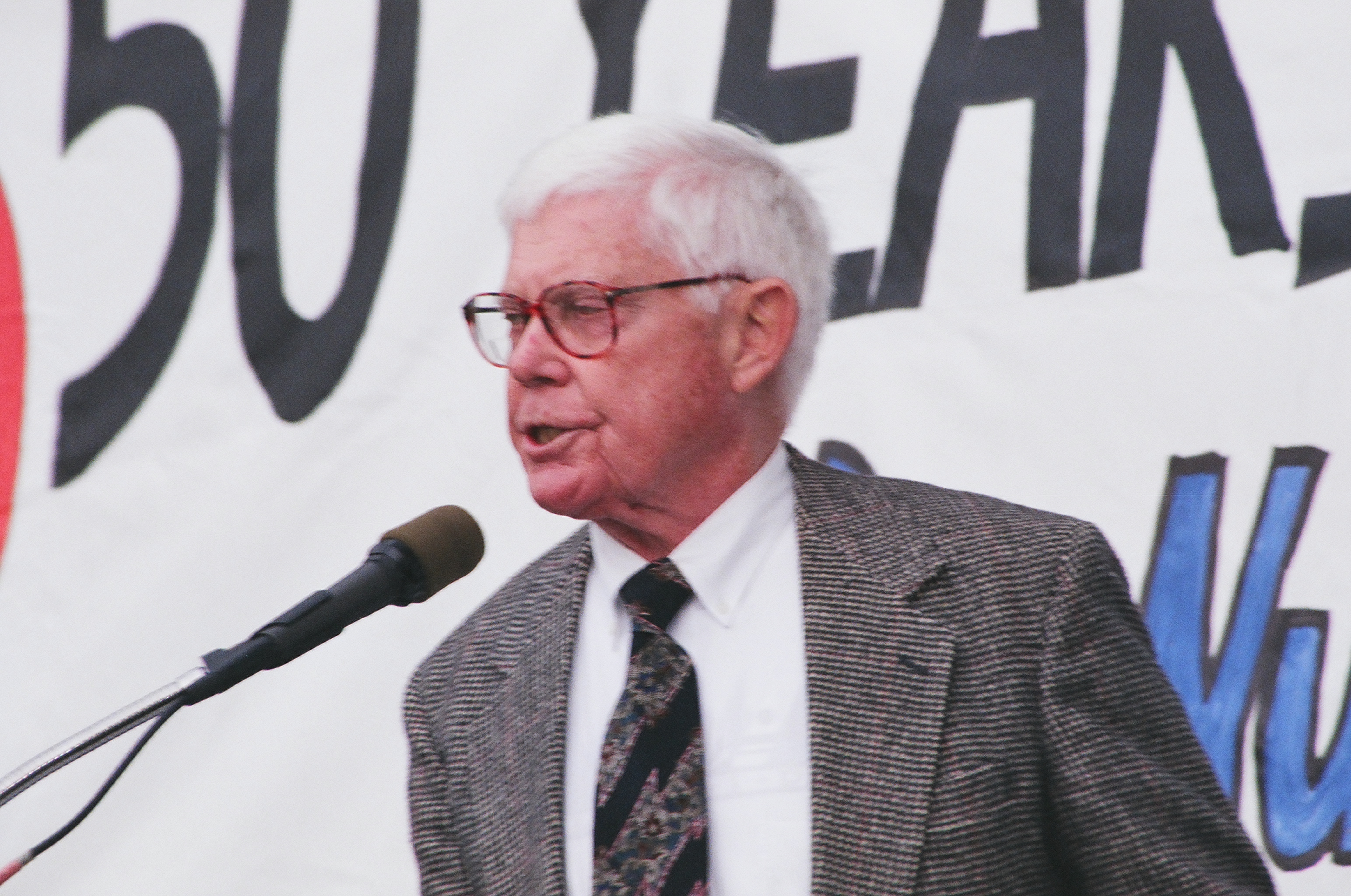

John Bayard Anderson (February 15, 1922 – December 3, 2017) was an American lawyer and politician who served in the

Soon after his return, Anderson was approached about running for public office. In 1956, Anderson was elected

Soon after his return, Anderson was approached about running for public office. In 1956, Anderson was elected

The Republican platform failed to endorse the

The Republican platform failed to endorse the

By the end of the campaign, much of Anderson's support came from college students.

By the end of the campaign, much of Anderson's support came from college students.

Arlington National Cemetery

, - {{DEFAULTSORT:Anderson, John B. 1922 births 2017 deaths 20th-century evangelicals 21st-century evangelicals American people of Swedish descent Brandeis University faculty Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Candidates in the 1980 United States presidential election District attorneys in Illinois Duke University faculty Harvard Law School alumni Illinois independents Members of the Evangelical Free Church of America Military personnel from Illinois Oregon State University faculty Politicians from Rockford, Illinois Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Illinois United States Army non-commissioned officers United States Army personnel of World War II University of Illinois College of Law alumni University of Massachusetts Amherst faculty Liberalism in the United States 20th-century members of the United States House of Representatives Radical centrist writers

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

, representing Illinois's 16th congressional district from 1961 to 1981. A member of the Republican Party, he also served as the Chairman of the House Republican Conference from 1969 until 1979. In 1980

Events January

* January 4 – U.S. President Jimmy Carter proclaims a United States grain embargo against the Soviet Union, grain embargo against the USSR with the support of the European Commission.

* January 6 – Global Positioning Sys ...

, he ran an independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in Pennsylvania, United States

* Independentes (English: Independents), a Portuguese artist ...

campaign for president, receiving 6.6% of the popular vote.

Born in Rockford, Illinois

Rockford is a city in Winnebago County, Illinois, Winnebago and Ogle County, Illinois, Ogle counties in the U.S. state of Illinois. Located in far northern Illinois on the banks of the Rock River (Mississippi River tributary), Rock River, Rockfor ...

, Anderson practiced law after serving in the Army

An army, ground force or land force is an armed force that fights primarily on land. In the broadest sense, it is the land-based military branch, service branch or armed service of a nation or country. It may also include aviation assets by ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. After a stint in the United States Foreign Service

The United States Foreign Service is the primary personnel system used by the diplomatic service of the United States federal government, under the aegis of the United States Department of State. It consists of over 13,000 professionals carr ...

, he won election as the State's Attorney for Winnebago County, Illinois

Winnebago County is a county located in the U.S. state of Illinois. According to the 2020 census, it had a population of 285,350 making it the seventh most populous county in Illinois behind Cook County and its five surrounding collar countie ...

. He won election to the House of Representatives in 1960 in a strongly Republican district. Initially one of the most conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

members of the House, Anderson's views moderated during the 1960s, particularly regarding social issues. He became chairman of the House Republican Conference

The House Republican Conference is the party caucus for Republicans in the United States House of Representatives. It hosts meetings, and is the primary forum for communicating the party's message to members. The conference produces a daily pu ...

in 1969 and remained in that position until 1979. He strongly criticized the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

as well as President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

's actions during the Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the Presidency of Richard Nixon, administration of President Richard Nixon. The scandal began in 1972 and ultimately led to Resignation of Richard Nixon, Nix ...

.

Anderson entered the 1980 Republican presidential primaries, introducing his signature campaign proposal of raising the gas tax while cutting Social Security taxes. Anderson established himself as a contender for the nomination in the early primaries but eventually dropped out of the Republican race, choosing to pursue an independent campaign for president. In the election, he finished third behind Republican nominee Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

and Democratic President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

. He won support among Democrats who became disillusioned with Carter, as well as Rockefeller Republican

The Rockefeller Republicans were members of the United States Republican Party (GOP) in the 1930s–1970s who held moderate-to- liberal views on domestic issues, similar to those of Nelson Rockefeller, Governor of New York (1959–1973) and Vi ...

s, independents, liberal intellectuals, and college students.

After the 1980 election, he resumed his legal career and helped found FairVote

FairVote is a 501(c)(3) organization and lobbying group in the United States. It was founded in 1992 as Citizens for Proportional Representation to support the implementation of proportional representation in American elections. Its focus chan ...

, an organization that advocates electoral reform

Electoral reform is a change in electoral systems that alters how public desires, usually expressed by cast votes, produce election results.

Description

Reforms can include changes to:

* Voting systems, such as adoption of proportional represen ...

, including an instant-runoff voting

Instant-runoff voting (IRV; ranked-choice voting (RCV), preferential voting, alternative vote) is a single-winner ranked voting election system where Sequential loser method, one or more eliminations are used to simulate Runoff (election), ...

system. He also won a lawsuit against the state of Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

, '' Anderson v. Celebrezze'', in which the Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

struck down early filing deadlines for independent candidates. Anderson served as a visiting professor at numerous universities and was on the boards of several organizations. He endorsed Green Party

A green party is a formally organized political party based on the principles of green politics, such as environmentalism and social justice.

Green party platforms typically embrace Social democracy, social democratic economic policies and fo ...

candidate Ralph Nader

Ralph Nader (; born February 27, 1934) is an American lawyer and political activist involved in consumer protection, environmentalism, and government reform causes. He is a Perennial candidate, perennial presidential candidate. His 1965 book '' ...

in 2000

2000 was designated as the International Year for the Culture of Peace and the World Mathematics, Mathematical Year.

Popular culture holds the year 2000 as the first year of the 21st century and the 3rd millennium, because of a tende ...

.

Early life and career

Anderson was born inRockford, Illinois

Rockford is a city in Winnebago County, Illinois, Winnebago and Ogle County, Illinois, Ogle counties in the U.S. state of Illinois. Located in far northern Illinois on the banks of the Rock River (Mississippi River tributary), Rock River, Rockfor ...

, where he grew up, the son of Mabel Edna (née Ring) and E. Albin Anderson. His father was a Swedish immigrant, as were his maternal grandparents. His father was born in 1885 in Eriksberg parish, Västergötland

Västergötland (), also known as West Gothland or the Latinized version Westrogothia in older literature, is one of the 25 traditional non-administrative provinces of Sweden (''landskap'' in Swedish), situated in the southwest of Sweden.

Vä ...

. His mother was born in 1886 Stillman Valley, Illinois, her father had immigrated from Rydaholm parish, Småland

Småland () is a historical Provinces of Sweden, province () in southern Sweden.

Småland borders Blekinge, Scania, Halland, Västergötland, Östergötland and the island Öland in the Baltic Sea. The name ''Småland'' literally means "small la ...

.

In his youth, he worked in his family's grocery store. He graduated as the valedictorian of his class (1939) at Rockford Central High School. He graduated from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC, U of I, Illinois, or University of Illinois) is a public land-grant research university in the Champaign–Urbana metropolitan area, Illinois, United States. Established in 1867, it is the f ...

in 1942, and started law school; his education was interrupted by World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. He enlisted in the Army

An army, ground force or land force is an armed force that fights primarily on land. In the broadest sense, it is the land-based military branch, service branch or armed service of a nation or country. It may also include aviation assets by ...

in 1943, and served as a staff sergeant

Staff sergeant is a Military rank, rank of non-commissioned officer used in the armed forces of many countries. It is also a police rank in some police services.

History of title

In origin, certain senior sergeants were assigned to administr ...

in the U.S. Field Artillery in France and Germany until the end of the war, receiving four service star

A service star is a miniature bronze or silver five-pointed star in diameter that is authorized to be worn by members of the eight uniformed services of the United States on medals and ribbons to denote an additional award or service period. T ...

s. After the war, Anderson returned to complete his education, earning a Juris Doctor

A Juris Doctor, Doctor of Jurisprudence, or Doctor of Law (JD) is a graduate-entry professional degree that primarily prepares individuals to practice law. In the United States and the Philippines, it is the only qualifying law degree. Other j ...

(J.D.) from the University of Illinois College of Law

The University of Illinois College of Law at Urbana-Champaign is the law school of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, a public land-grant research university in Champaign and Urbana, Illinois. It was established in 1897 and offers th ...

in 1946.

Anderson was admitted to the Illinois bar the same year, and practiced law in Rockford. Soon after, he moved east to attend Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a Private university, private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, Harvard Law School is the oldest law school in continuous operation in the United ...

, obtaining a Master of Laws

A Master of Laws (M.L. or LL.M.; Latin: ' or ') is a postgraduate academic degree, pursued by those either holding an undergraduate academic law degree, a professional law degree, or an undergraduate degree in another subject.

In many jurisdi ...

(LL.M.) in 1949. While at Harvard, he served on the faculty of Northeastern University School of Law

The Northeastern University School of Law is the law school of Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts.

History

Northeastern University School of Law was founded by the Boston Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) in 1898 as the f ...

in Boston. In another brief return to Rockford, Anderson practiced at the law firm Large, Reno & Zahm (now Reno & Zahm LLP). Thereafter, Anderson joined the Foreign Service Foreign Service may refer to:

* Diplomatic service, the body of diplomats and foreign policy officers maintained by the government of a country

* United States Foreign Service, the diplomatic service of the United States government

**Foreign Service ...

. From 1952 to 1955, he served in Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

, as the Economic Reporting Officer in the Eastern Affairs Division, as an adviser on the staff of the United States High Commissioner for Germany. At the end of his tour, he left the foreign service and once again returned to the practice of law in Rockford.

Early political career

Soon after his return, Anderson was approached about running for public office. In 1956, Anderson was elected

Soon after his return, Anderson was approached about running for public office. In 1956, Anderson was elected State's Attorney

In the United States, a district attorney (DA), county attorney, county prosecutor, state attorney, state's attorney, prosecuting attorney, commonwealth's attorney, or solicitor is the chief prosecutor or chief law enforcement officer represen ...

in Winnebago County, Illinois

Winnebago County is a county located in the U.S. state of Illinois. According to the 2020 census, it had a population of 285,350 making it the seventh most populous county in Illinois behind Cook County and its five surrounding collar countie ...

, first winning a four-person race in the April primary by 1,330 votes and then the general election in November by 11,456 votes. After serving for one term, he was ready to leave that office when the local congressman, 28-year incumbent Leo E. Allen, announced his retirement. Anderson joined the Republican primary for Allen's 16th District seat—the real contest in this then-solidly Republican district based in Rockford and stretching across the state's northwest corner. He won a five-way primary in April (by 5,900 votes) in April and then the general election in November (by 45,000 votes). He served in the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

for ten terms, from 1961 to 1981.

Initially, Anderson was among the most conservative members of the Republican caucus. Three times (in 1961, 1963, and 1965) in his early terms as a Congressman, Anderson introduced a constitutional amendment

A constitutional amendment (or constitutional alteration) is a modification of the constitution of a polity, organization or other type of entity. Amendments are often interwoven into the relevant sections of an existing constitution, directly alt ...

to attempt to "recognize the law and authority of Jesus Christ" over the United States. The bills died quietly but later came back to haunt Anderson in his presidential candidacy. Anderson voted in favor of the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968

Events January–February

* January 1968, January – The I'm Backing Britain, I'm Backing Britain campaign starts spontaneously.

* January 5 – Prague Spring: Alexander Dubček is chosen as leader of the Communist Party of Cze ...

, as well as the 24th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights move ...

.

Initially supportive of Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and major general in the United States Air Force, Air Force Reserve who served as a United States senator from 1953 to 1965 and 1969 to 1987, and was the Re ...

's candidacy for president in 1964 and believing Goldwater to be a "honest, sincere man", Anderson came to believe that most of his ideas would not work on a national scale, and described Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

's victory over Goldwater in the 1964 election as a vote for moderation, believing that the Republican Party needed to go in a moderate direction. Other factors such as attending the funerals of Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner

Michael Henry Schwerner (November 6, 1939 – June 21, 1964) was an American civil rights activist. He was one of three Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) field workers murdered in rural Neshoba County, Mississippi, by members of the Ku Klux K ...

, and James Chaney, as well as the street riots happening in America at that point, led to Anderson shift from the right to the left on social issues, although his fiscal positions largely remained conservative. The riots led Anderson to vote in favor of the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1968

Housing refers to a property containing one or more shelter as a living space. Housing spaces are inhabited either by individuals or a collective group of people. Housing is also referred to as a human need and human right, playing a cr ...

.No Holding Back: The 1980 John B. Anderson Presidential Campaign

In 1964, Anderson won appointment to a seat on the powerful Rules Committee. In 1969, he became Chairman

The chair, also chairman, chairwoman, or chairperson, is the presiding officer of an organized group such as a board, committee, or deliberative assembly. The person holding the office, who is typically elected or appointed by members of the gro ...

of the House Republican Conference

The House Republican Conference is the party caucus for Republicans in the United States House of Representatives. It hosts meetings, and is the primary forum for communicating the party's message to members. The conference produces a daily pu ...

, the number three position in the House Republican hierarchy in what was (at that time) the minority party. Anderson increasingly found himself at odds with conservatives in his home district and other members of the House. He was not always a faithful supporter of the Republican agenda, despite his high rank in the Republican caucus. He was very critical of the Vietnam War, and was a very controversial critic of Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

during Watergate

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon. The scandal began in 1972 and ultimately led to Nixon's resignation in 1974, in August of that year. It revol ...

. In 1974, despite his criticism of Nixon, the strong anti-Republican tide in that year's election held him to 55% of the vote, what would be the lowest percentage of his career. Anderson described Nixon as a "man of great duplicity".

His spot as the chairman of the House Republican Committee was challenged three times after his election and, when Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. (born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was the 38th president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, Ford assumed the p ...

was defeated in the 1976 presidential campaign, Anderson lost a key ally in Washington. In 1970 and 1972, Anderson had a Democratic challenger in Rockford Professor John E. Devine. In both years, Anderson defeated Devine by a wide margin. In late 1977, a fundamentalist television minister from Rockford, Don Lyon, announced that he would challenge Anderson in the Republican primary. It was a contentious campaign, where Lyon, with his experience before the camera, proved to be a formidable candidate.Ira Teinowitz, "Anderson–Lyon Race is Top Attraction", ''Rockford Morning Star'', February 26, 1978. Lyon raised a great deal of money, won backing from many conservatives in the community and party, and put quite a scare into the Anderson team. Though Anderson was a leader in the House and the campaign commanded national attention, Anderson won the primary by 16% of the vote. Anderson was aided in this campaign by strong newspaper endorsements and crossover support from independents and Democrats.

1980 presidential campaign

Early campaign

In 1978, Anderson formed a presidential campaignexploratory committee

In the election politics of the United States, an exploratory committee is an organization established to help determine whether a potential candidate should run for an elected office. They are most often cited in reference to candidates for pre ...

, finding little public or media interest. In late April 1979, Anderson made the decision to enter the Republican primary, joining a field that included Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

, Bob Dole

Robert Joseph Dole (July 22, 1923 – December 5, 2021) was an American politician and attorney who represented Kansas in the United States Senate from 1969 to 1996. He was the Party leaders of the United States Senate, Republican Leader of th ...

, John Connally

John Bowden Connally Jr. (February 27, 1917June 15, 1993) was an American politician who served as the 39th governor of Texas from 1963 to 1969 and as the 61st United States secretary of the treasury from 1971 to 1972. He began his career as a Hi ...

, Howard Baker

Howard Henry Baker Jr. (November 15, 1925 June 26, 2014) was an American politician, diplomat and photographer who served as a United States Senator from Tennessee from 1967 to 1985. During his tenure, he rose to the rank of Senate Minority Le ...

, George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushBefore the outcome of the 2000 United States presidential election, he was usually referred to simply as "George Bush" but became more commonly known as "George H. W. Bush", "Bush Senior," "Bush 41," and even "Bush th ...

, and the perennial candidate

A perennial candidate is a political candidate who frequently runs for elected office and rarely, if ever, wins. Perennial candidates are most common where there is no limit on the number of times that a person can run for office and little cost ...

Harold Stassen

Harold Edward Stassen (April 13, 1907 – March 4, 2001) was an American Republican Party (United States), Republican Party politician, military officer, and attorney who was the List of governors of Minnesota, 25th governor of Minnesota from 193 ...

. Within the last weeks of 1979, Anderson introduced his signature campaign proposal, advocating that a 50-cent a gallon gas tax be enacted with a corresponding 50% reduction in Social Security taxes. Anderson built state campaigns in four targeted states—New Hampshire

New Hampshire ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

, and Wisconsin

Wisconsin ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest of the United States. It borders Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, Michig ...

. He won some political support among Republicans, picking up endorsements along the way that helped legitimize him in the race. He began to build support among media elites, who appreciated his articulateness, straightforward manner, moderate positions, and his refusal to walk down the conservative path that all of the other Republicans were traveling.

Anderson often referred to his candidacy as "a campaign of ideas". He supported tax credits for businesses' research-and-development budgets, which he believed would increase American productivity; he also supported increasing funding for research at universities. He supported lowering interest rates, antitrust action, conservation, environmental protection and limiting oil companies from absorbing small businesses through legislation. He opposed Ronald Reagan's proposal to cut taxes broadly, which he feared would increase the national debt

A country's gross government debt (also called public debt or sovereign debt) is the financial liabilities of the government sector. Changes in government debt over time reflect primarily borrowing due to past government deficits. A deficit occ ...

and the inflation rate (which was very high at the time of the campaign), believing it to be " Coolidge-era economics". He also supported a tax on gasoline to reduce dependence on foreign oil. He supported the Equal Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was a proposed amendment to the Constitution of the United States, United States Constitution that would explicitly prohibit sex discrimination. It is not currently a part of the Constitution, though its Ratifi ...

, gay rights

Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Not ...

and abortion rights

Abortion-rights movements, also self-styled as pro-choice movements, are movements that advocate for legal access to induced abortion services, including elective abortion. They seek to represent and support women who wish to terminate their p ...

generally; he also touted his perfect record of having supported all civil rights legislation since 1960. He opposed the requirement for registration for the military draft

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it contin ...

, which Jimmy Carter had reinstated. This made him appealing to many liberal college students who were dissatisfied with Carter. However, he also voiced support for a strong, flexible military and support for NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

against the USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, as well as several other positions associated with Republicans, including deregulation of some industries such as natural gas and oil prices, and a balanced budget to be achieved mainly by reductions in government spending.

Republican primary

On January 5, 1980, in the Republican candidates' debate inDes Moines, Iowa

Des Moines is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of cities in Iowa, most populous city in the U.S. state of Iowa. It is the county seat of Polk County, Iowa, Polk County with parts extending into Warren County, Iowa, Wa ...

, unlike the other candidates, Anderson said lowering taxes, increasing defense spending, and balancing the budget were an impossible combination. In a stirring summation, Anderson invoked his father's immigration to the United States and said that Americans would have to make sacrifices "for a better tomorrow." For the next week, Anderson's name and face were all over the national news programs, in newspapers, and in national news magazines. Anderson spent less than $2000 in Iowa, but he finished with 4.3% of the vote. The television networks were covering the event, portraying Anderson to a national audience as a man of character and principle. When the voters in New Hampshire went to the polls, Anderson again exceeded the expectations, finishing fourth with just under 10% of the vote.

Anderson was declared the winner in both Massachusetts and Vermont by the Associated Press, but the following morning ended up losing both primaries by a slim margin. In Massachusetts, he lost to George Bush by 0.3% and in Vermont he lost to Reagan by 690 votes. Anderson arrived in Illinois following the New England primaries and had a lead in the state polls, but his Illinois campaign struggled despite endorsements from the state's two largest newspapers. Reagan defeated him, 48% to 37%. Anderson carried Chicago and Rockford, the state's two largest cities at the time, but he lost in the more conservative southern section of the state. The next week, there was a primary in Connecticut, which (while Anderson was on the ballot) his team had chosen not to campaign actively in. He finished third in Connecticut with 22% of the vote, and it seemed to most observers like any other loss, whether Anderson said he was competing or not. Next was Wisconsin, and this was thought to be Anderson's best chance for victory, but he again finished third, winning 27% of the vote.

Independent campaign

The Republican platform failed to endorse the

The Republican platform failed to endorse the Equal Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was a proposed amendment to the Constitution of the United States, United States Constitution that would explicitly prohibit sex discrimination. It is not currently a part of the Constitution, though its Ratifi ...

or support extension of time for its ratification. Anderson was a strong supporter of both. Pollsters were finding that Anderson was much more popular across the country with all voters than he was in the Republican primary states. Without any campaigning, he was running at 22% nationally in a three-way race. Anderson's personal aide and confidant, Tom Wartowski, encouraged him to remain in the Republican Party. Anderson faced a huge number of obstacles as a non-major party candidate: having to qualify for 51 ballots (which the major parties appeared on automatically), having to raise money to run a campaign (the major parties received close to $30 million in government money for their campaigns), having to win national coverage, having to build a campaign overnight, and having to find a suitable running mate among them. He built a new campaign team, qualified for every ballot, raised a great deal of money, and rose in the polls to as high as 26% in one Gallup poll

Gallup, Inc. is an American multinational analytics and advisory company based in Washington, D.C. Founded by George Gallup in 1935, the company became known for its public opinion polls conducted worldwide. Gallup provides analytics and man ...

.

However, in the summer of 1980, he had an overseas campaign tour to show his foreign policy credentials and it took a drubbing on national television. The major parties, particularly the Republicans, basked in the spotlight of their national conventions where Anderson was left out of the coverage. Anderson made an appearance with Ted Kennedy

Edward Moore Kennedy (February 22, 1932 – August 25, 2009) was an American lawyer and politician from Massachusetts who served as a member of the United States Senate from 1962 to his death in 2009. A member of the Democratic Party and ...

and it, too, was a huge error. By the third week of August he was in the 13–15% range in the polls. A critical issue for Anderson was appearing in the fall presidential debates after the League of Women Voters invited him to appear due to popular interest in his candidacy, although he was only polling 12% at that time. In late August, he named Patrick Lucey

Patrick Joseph Lucey (March 21, 1918 – May 10, 2014) was an American politician. A member of the United States Democratic Party, Democratic Party, he served as the 38th governor of Wisconsin from 1971 to 1977. He was also independent president ...

, the former two-term Democratic Governor of Wisconsin and Ambassador to Mexico as his running mate. Late in August, Anderson released a 317-page comprehensive platform, under the banner of the National Unity Party, that was very well received. In early September, a court challenge to Federal Election Campaign Act was successful and Anderson qualified for post-election public funding. Also, Anderson submitted his petitions for his fifty-first ballot. Then, the League ruled that the polls showed that he had met the qualification threshold and said he would appear in the debates.

Fall campaign

Carter said that he would not appear on stage with Anderson, and sat out the debate, which hurt the President in the eyes of voters. Reagan and Anderson had adebate

Debate is a process that involves formal discourse, discussion, and oral addresses on a particular topic or collection of topics, often with a moderator and an audience. In a debate, arguments are put forward for opposing viewpoints. Historica ...

in Baltimore on September 21, 1980. Anderson did well, and polls showed he won a modest debate victory over Reagan, but Reagan, who had been portrayed by Carter throughout the campaign as something of a warmonger, was seen as a reasonable candidate who carried himself well in the debate. The debate was Anderson's big opportunity as he needed a break-out performance, but what he got was a modest victory. In the following weeks, Anderson slowly faded out of the picture with his support dropping from 16% to 10–12% in the first half of October. By the end of the month, Reagan debated Carter alone, but CNN

Cable News Network (CNN) is a multinational news organization operating, most notably, a website and a TV channel headquartered in Atlanta. Founded in 1980 by American media proprietor Ted Turner and Reese Schonfeld as a 24-hour cable ne ...

attempted to let Anderson participate in the 2nd debate by tape delay. Daniel Schorr

Daniel Louis Schorr (August 31, 1916 – July 23, 2010) was an American journalist who covered world news for more than 60 years. He was most recently a Senior News Analyst for National Public Radio (NPR). Schorr won three Emmy Awards for his te ...

asked Anderson the questions from the Carter-Reagan debate, and then CNN interspersed Anderson's live answers with tape delayed responses from Carter and Reagan.

Anderson's support continued to fade down to 5%, although rose up to 8% just before election day. Although Reagan would win a sizable victory, the polls showed the two major party candidates closer (Gallup's final poll was 47–44–8 going into the election and it was clear that many would-be Anderson supporters had been pulled away by Carter and Reagan. In the end, Anderson finished with 6.6% of the vote. Most of Anderson's support came from those Liberal Republicans who were suspicious of, or even hostile to, Reagan's conservative record. Many prominent intellectuals, including ''All in the Family

''All in the Family'' is an American sitcoms in the United States, sitcom television series that aired on CBS for nine seasons from January 12, 1971, to April 8, 1979, with a total of 205 episodes. It was later produced as ''Archie Bunker's Pla ...

'' creator Norman Lear

Norman Milton Lear (July 27, 1922December 5, 2023) was an American screenwriter and producer who produced, wrote, created, or developed over 100 shows. Lear created and produced numerous popular 1970s sitcoms, including ''All in the Family'' (1 ...

, and the editors of the liberal magazine ''The New Republic

''The New Republic'' (often abbreviated as ''TNR'') is an American magazine focused on domestic politics, news, culture, and the arts from a left-wing perspective. It publishes ten print magazines a year and a daily online platform. ''The New Y ...

'', also endorsed the Anderson campaign. Cartoonist Garry Trudeau

Garretson Beekman Trudeau (born July 21, 1948) is an American cartoonist best known for creating the ''Doonesbury'' comic strip.

Trudeau won the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning in 1975, making him the first comic strip artist to win a ...

's ''Doonesbury

''Doonesbury'' is a comic strip by American cartoonist Garry Trudeau that chronicles the adventures and lives of an array of characters of various ages, professions, and backgrounds, from the President of the United States to the title character, ...

'' ran several strips sympathetic to the Anderson campaign. Former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis

Jacqueline Lee Kennedy Onassis ( ; July 28, 1929 – May 19, 1994) was an American writer, book editor, and socialite who served as the first lady of the United States from 1961 to 1963, as the wife of President John F. Kennedy. A popular f ...

, actor Paul Newman

Paul Leonard Newman (January 26, 1925 – September 26, 2008) was an American actor, film director, race car driver, philanthropist, and activist. He was the recipient of List of awards and nominations received by Paul Newman, numerous awards ...

and historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.

Arthur Meier Schlesinger Jr. ( ; born Arthur Bancroft Schlesinger; October 15, 1917 – February 28, 2007) was an American historian, social critic, and public intellectual. The son of the influential historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. and a ...

were also reported to be Anderson supporters.

Although the Carter campaign feared Anderson could be a spoiler

Spoiler or Spoilers may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* Spoiler (media), something that reveals significant plot elements

* The Spoiler, DC Comics superheroine Stephanie Brown

Film and television

* ''Spoiler'' (film), 1998 American ...

, Anderson's campaign turned out to be "simply another option" for frustrated voters who had already decided not to back Carter for another term. Polls found that around 37% of Anderson voters favored Reagan as their second choice over Carter. Anderson did not carry a single precinct in the country. Anderson's finish was still the best showing for a third-party

Third party may refer to:

Business

* Third-party source, a supplier company not owned by the buyer or seller

* Third-party beneficiary, a person who could sue on a contract, despite not being an active party

* Third-party insurance, such as a veh ...

candidate since George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who was the 45th and longest-serving governor of Alabama (1963–1967; 1971–1979; 1983–1987), and the List of longest-serving governors of U.S. s ...

's 14% in 1968 and stands as the seventh-best for any such candidate since the Civil War (trailing James B. Weaver's 8.5% in 1892, Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

's 27% in 1912, Robert La Follette

Robert Marion La Follette Sr. (June 14, 1855June 18, 1925), nicknamed "Fighting Bob," was an American lawyer and politician. He represented Wisconsin in both chambers of Congress and served as the 20th governor of Wisconsin from 1901 to 1906. ...

's 17% in 1924, Wallace, and Ross Perot

Henry Ross Perot ( ; June 27, 1930 – July 9, 2019) was an American businessman, politician, and philanthropist. He was the founder and chief executive officer of Electronic Data Systems and Perot Systems. He ran an Independent politician ...

's 19% and 8% in 1992 and 1996, respectively). He pursued Ohio's refusal to provide ballot access to the U.S. Supreme Court and won 5–4 in '' Anderson v. Celebrezze''. His inability to make headway against the ''de facto'' two-party system as an independent in that election would later lead him to become an advocate of instant-runoff voting

Instant-runoff voting (IRV; ranked-choice voting (RCV), preferential voting, alternative vote) is a single-winner ranked voting election system where Sequential loser method, one or more eliminations are used to simulate Runoff (election), ...

, helping to found FairVote

FairVote is a 501(c)(3) organization and lobbying group in the United States. It was founded in 1992 as Citizens for Proportional Representation to support the implementation of proportional representation in American elections. Its focus chan ...

in 1992.

Later career

By the end of the campaign, much of Anderson's support came from college students.

By the end of the campaign, much of Anderson's support came from college students. Jesse Ventura

Jesse Ventura (born James George Janos; July 15, 1951) is an American politician, political commentator, actor, media personality, and retired professional wrestler. After achieving fame in the WWE, World Wrestling Federation (WWF, now WWE), he ...

stated during an interview that he voted for Anderson in 1980. Anderson capitalized on that by becoming a visiting professor at a series of universities: Stanford University

Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University, is a Private university, private research university in Stanford, California, United States. It was founded in 1885 by railroad magnate Leland Stanford (the eighth ...

, University of Southern California

The University of Southern California (USC, SC, or Southern Cal) is a Private university, private research university in Los Angeles, California, United States. Founded in 1880 by Robert M. Widney, it is the oldest private research university in ...

, Duke University

Duke University is a Private university, private research university in Durham, North Carolina, United States. Founded by Methodists and Quakers in the present-day city of Trinity, North Carolina, Trinity in 1838, the school moved to Durham in 1 ...

, University of Illinois College of Law

The University of Illinois College of Law at Urbana-Champaign is the law school of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, a public land-grant research university in Champaign and Urbana, Illinois. It was established in 1897 and offers th ...

, Brandeis University

Brandeis University () is a Private university, private research university in Waltham, Massachusetts, United States. It is located within the Greater Boston area. Founded in 1948 as a nonsectarian, non-sectarian, coeducational university, Bra ...

, Bryn Mawr College

Bryn Mawr College ( ; Welsh language, Welsh: ) is a Private college, private Women's colleges in the United States, women's Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, United States. Founded as a ...

, Oregon State University

Oregon State University (OSU) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Corvallis, Oregon, United States. OSU offers more than 200 undergraduate degree programs and a variety of graduate and doctor ...

, University of Massachusetts Amherst

The University of Massachusetts Amherst (UMass Amherst) is a public land-grant research university in Amherst, Massachusetts, United States. It is the flagship campus of the University of Massachusetts system and was founded in 1863 as the ...

, and Nova Southeastern University

Nova Southeastern University (NSU) is a Private university, private research university in Florida with its main campus in Fort Lauderdale-Davie, Florida, Davie, Florida, United States. The university consists of 14 colleges, offering over ...

and delivered the lecture at the 1988 Waldo Family Lecture Series on International Relations

The Waldo Family Lecture Series on International Relations is a lecture series which takes place at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia. The university's first endowed lecture series was endowed by the Waldo family in 1985 to honor the m ...

at Old Dominion University

Old Dominion University (ODU) is a Public university, public research university in Norfolk, Virginia, United States. Established in 1930 as the two-year Norfolk Division of the College of William & Mary, it began by educating people with fewer ...

. In 1984, Anderson endorsed Walter Mondale

Walter Frederick "Fritz" Mondale (January 5, 1928April 19, 2021) was the 42nd vice president of the United States serving from 1977 to 1981 under President Jimmy Carter. He previously served as a U.S. senator from Minnesota from 1964 to 1976. ...

over Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

in the presidential election. He was chair of FairVote

FairVote is a 501(c)(3) organization and lobbying group in the United States. It was founded in 1992 as Citizens for Proportional Representation to support the implementation of proportional representation in American elections. Its focus chan ...

from 1996 to 2008, after helping to found the organization in 1992, and continued to serve on its board until 2014. He also served as president of the World Federalist Association and on the advisory board of Public Campaign

Every Voice was an American nonprofit, progressive liberal political advocacy organization.

and the Electronic Privacy Information Center

The Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) is an independent nonprofit research center established in 1994 to protect privacy, freedom of expression, and democratic values in the information age. Based in Washington, D.C., their mission i ...

, and was of counsel

Of counsel is the title of an attorney in the legal profession of the United States who often has a relationship with a law firm or an organization but is neither an associate nor partner. Some firms use titles such as "counsel", "special couns ...

to the Washington, D.C.–based law firm of Greenberg & Lieberman, LLC.

He was the first executive director of the Council for the National Interest

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or nation ...

, founded in 1989 by former Congressmen Paul Findley (R-IL) and Pete McCloskey

Paul Norton "Pete" McCloskey Jr. (September 29, 1927 – May 8, 2024) was an American politician who represented San Mateo County, California, as a Republican in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1967 to 1983.

Born in Loma Linda, Californi ...

(R-CA) to promote American interests in the Middle East. In the 2000 U.S. presidential election, he was briefly considered as possible candidate for the Reform Party nomination but instead endorsed Ralph Nader

Ralph Nader (; born February 27, 1934) is an American lawyer and political activist involved in consumer protection, environmentalism, and government reform causes. He is a Perennial candidate, perennial presidential candidate. His 1965 book '' ...

, who was nominated by the Green Party

A green party is a formally organized political party based on the principles of green politics, such as environmentalism and social justice.

Green party platforms typically embrace Social democracy, social democratic economic policies and fo ...

. In January 2008, Anderson indicated strong support for the candidacy of a fellow Illinoisan, Democratic contender Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

. In 2012, he played a role in the creation of the Justice Party, a progressive and social-democratic

Social democracy is a social, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achieving social equality. In modern practice, socia ...

party organized to support the candidacy of former Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City, often shortened to Salt Lake or SLC, is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Utah. It is the county seat of Salt Lake County, the most populous county in the state. The city is the core of the Salt Lake Ci ...

mayor Rocky Anderson

Ross Carl "Rocky" Anderson II (born September 9, 1951) is an American attorney, writer, activist, and civil and human rights advocate. He served two terms as the 33rd List of mayors of Salt Lake City, Mayor of Salt Lake City, Utah, from 2000 to ...

(no relation) for the 2012 U.S. presidential election. On August 6, 2014, he endorsed the campaign for the United Nations Parliamentary Assembly

The United Nations Parliamentary Assembly (UNPA) is a proposed parliamentary body within the United Nations (UN) system.

The Campaign for a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly (CUNPA) was formed in 2007 by Democracy Without Borders (fo ...

(UNPA), one of only six persons who served in Congress ever to do so.

Death

Anderson died in Washington, D.C., on December 3, 2017, at the age of 95. He is interred atArlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is the largest cemetery in the United States National Cemetery System, one of two maintained by the United States Army. More than 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington County, Virginia.

...

on June 22, 2018.

References

Citations

Sources

* * *External links

*Arlington National Cemetery

, - {{DEFAULTSORT:Anderson, John B. 1922 births 2017 deaths 20th-century evangelicals 21st-century evangelicals American people of Swedish descent Brandeis University faculty Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Candidates in the 1980 United States presidential election District attorneys in Illinois Duke University faculty Harvard Law School alumni Illinois independents Members of the Evangelical Free Church of America Military personnel from Illinois Oregon State University faculty Politicians from Rockford, Illinois Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Illinois United States Army non-commissioned officers United States Army personnel of World War II University of Illinois College of Law alumni University of Massachusetts Amherst faculty Liberalism in the United States 20th-century members of the United States House of Representatives Radical centrist writers