Jisei on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The death poem is a genre of

The poem's structure can be in one of many forms, including the two traditional forms in Japanese literature: '' kanshi'' or ''

The poem's structure can be in one of many forms, including the two traditional forms in Japanese literature: '' kanshi'' or '' On March 17, 1945, General

On March 17, 1945, General

poetry

Poetry (from the Greek language, Greek word ''poiesis'', "making") is a form of literature, literary art that uses aesthetics, aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meaning (linguistics), meanings in addition to, or in ...

that developed in the literary traditions of the Sinosphere

The Sinosphere, also known as the Chinese cultural sphere, East Asian cultural sphere, or the Sinic world, encompasses multiple countries in East Asia and Southeast Asia that were historically heavily influenced by Chinese culture. The Sinosph ...

—most prominently in Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

as well as certain periods of Chinese history

The history of China spans several millennia across a wide geographical area. Each region now considered part of the Chinese world has experienced periods of unity, fracture, prosperity, and strife. Chinese civilization first emerged in the Y ...

, Joseon Korea

Joseon ( ; ; also romanized as ''Chosun''), officially Great Joseon (), was a dynastic kingdom of Korea that existed for 505 years. It was founded by Taejo of Joseon in July 1392 and replaced by the Korean Empire in October 1897. The kingdom w ...

, and Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

. They tend to offer a reflection on death—both in general and concerning the imminent death of the author—that is often coupled with a meaningful observation on life. The practice of writing a death poem has its origins in Zen Buddhism

Zen (; from Chinese: '' Chán''; in Korean: ''Sŏn'', and Vietnamese: ''Thiền'') is a Mahayana Buddhist tradition that developed in China during the Tang dynasty by blending Indian Mahayana Buddhism, particularly Yogacara and Madhyamaka ph ...

. It is a concept or worldview derived from the Buddhist

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

teaching of the , specifically that the material world is transient and , that attachment to it causes , and ultimately all reality is an . These poems became associated with the literate, spiritual, and ruling segments of society, as they were customarily composed by a poet, warrior, nobleman, or Buddhist

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

monk

A monk (; from , ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a man who is a member of a religious order and lives in a monastery. A monk usually lives his life in prayer and contemplation. The concept is ancient and can be seen in many reli ...

.

The writing of a poem at the time of one's death and reflecting on the nature of death in an impermanent, transitory world is unique to East Asian culture. It has close ties with Buddhism, and particularly the mystical Zen Buddhism

Zen (; from Chinese: '' Chán''; in Korean: ''Sŏn'', and Vietnamese: ''Thiền'') is a Mahayana Buddhist tradition that developed in China during the Tang dynasty by blending Indian Mahayana Buddhism, particularly Yogacara and Madhyamaka ph ...

(of Japan), Chan Buddhism

Chan (; of ), from Sanskrit '' dhyāna'' (meaning " meditation" or "meditative state"), is a Chinese school of Mahāyāna Buddhism. It developed in China from the 6th century CE onwards, becoming especially popular during the Tang and Song ...

(of China), Seon Buddhism (of Korea), and Thiền Buddhism

Thiền Buddhism (, , ) is the name for the Vietnamese school of Zen, Zen Buddhism. Thiền is the Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary, Sino-Vietnamese pronunciation of the Middle Chinese word 禪 (''chán''), an abbreviation of 禪那 (''chánnà''; th ...

(of Vietnam). From its inception, Buddhism has stressed the importance of death because awareness of death is what prompted the Buddha to perceive the ultimate futility of worldly concerns and pleasures. A death poem exemplifies the search for a new viewpoint, a new way of looking at life and things generally, or a version of enlightenment (''satori

''Satori'' () is a Japanese Buddhist term for " awakening", "comprehension; understanding". The word derives from the Japanese verb '' satoru''.

In the Zen Buddhist tradition, ''satori'' refers to a deep experience of '' kenshō'', "seeing ...

'' in Japanese;'' wu'' in Chinese). According to comparative religion scholar Julia Ching

Julia Ching, CM RSC () (1934 – October 26, 2001) was professor of religion, philosophy and East Asian studies at the University of Toronto.

Biography

Born in Shanghai in 1934, Ching fled the Republic of China as a refugee during World War I ...

, Japanese Buddhism

Buddhism was first established in Japan in the 6th century CE. Most of the Japanese Buddhists belong to new schools of Buddhism which were established in the Kamakura period (1185-1333). During the Edo period (1603–1868), Buddhism was cont ...

"is so closely associated with the memory of the dead and the ancestral cult that the family shrines dedicated to the ancestors, and still occupying a place of honor in homes, are popularly called the ''Butsudan

A , sometimes spelled butudan, is a shrine commonly found in temples and homes in Japanese Buddhist cultures. A ''butsudan'' is either a defined, often ornate platform or simply a wooden cabinet sometimes crafted with doors that enclose and p ...

'', literally 'the Buddhist altars'. It has been the custom in modern Japan to have Shinto wedding

Shinto weddings, , began in Japan during the early 20th century, popularized after the marriage of Crown Prince Yoshihito and his bride, Princess Kujo Sadako. The ceremony relies heavily on Shinto themes of purification, and involves ceremonial sak ...

s, but to turn to Buddhism in times of bereavement and for funeral services".

The writing of a death poem was limited to the society's literate class, ruling class, samurai, and monks. It was introduced to Western audiences during World War II when Japanese soldiers, emboldened by their culture's samurai

The samurai () were members of the warrior class in Japan. They were originally provincial warriors who came from wealthy landowning families who could afford to train their men to be mounted archers. In the 8th century AD, the imperial court d ...

legacy, would write poems before suicidal missions or battles.

Chinese death poems

Yuan Chonghuan

Yuan Chonghuan

Yuan Chonghuan (; 6 June 1584 – 22 September 1630), courtesy name Yuansu, art name Ziru, was a Chinese politician, military general and writer who served under the Ming dynasty. Remembered as a national hero of Ming China and widely regarded ...

(, 1584–1630) was a politician and military general who served under the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming was the last imperial dynasty of ...

. He is best known for defending Liaodong from Jurchen invaders during the Later Jin invasion of the Ming. Yuan met his end when he was arrested and executed by lingchi

''Lingchi'' ( IPA: , ), usually translated "slow slicing" or "death by a thousand cuts", was a form of torture and execution used in China from roughly 900 until it was banned in 1905. It was also used in Vietnam and Korea. In this form of ex ...

("slow slicing") on the order of the Chongzhen Emperor

The Chongzhen Emperor (6 February 1611 – 25 April 1644), personal name Zhu Youjian, courtesy name Deyue,Wang Yuan (王源),''Ju ye tang wen ji'' (《居業堂文集》), vol. 19. "聞之張景蔚親見烈皇帝神主題御諱字德約,行� ...

under false charges of treason, which were believed to have been planted against him by the Jurchens. Before his execution, he produced the following poem.

Xia Wanchun

Xia Wanchun (, 1631–1647) was a Ming dynasty poet and soldier. He is famous for resisting the Manchu invaders and died aged 17. He wrote the poem before his death.Zheng Ting

Zheng Ting (; died 621) was a politician in the end of theSui dynasty

The Sui dynasty ( ) was a short-lived Dynasties of China, Chinese imperial dynasty that ruled from 581 to 618. The re-unification of China proper under the Sui brought the Northern and Southern dynasties era to a close, ending a prolonged peri ...

. He was executed by Wang Shichong

Wang Shichong (; 567– August 621), courtesy name Xingman (行滿), was a Chinese military general, monarch, and politician during the Sui dynasty who deposed Sui's last emperor Yang Tong and briefly ruled as the emperor of a succeeding state ...

after trying to resign from his official position under Wang and become a Buddhist monk. He faced the execution without fear and wrote this death poem, which reflected his strong Buddhist

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

belief.

Yang Jisheng

Yang Jisheng (; 1516 – 1555) was a Chinese court official of the Ming dynasty who held multiple posts during the reign of theJiajing Emperor

The Jiajing Emperor (16September 150723January 1567), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizong of Ming, personal name Zhu Houcong, art name, art names Yaozhai, Leixuan, and Tianchi Diaosou, was the 12th List of emperors of the Ming ...

. He was executed because of his stand against political opponent Yan Song

Yan Song (3 March 1480 – 1565), courtesy name Weizhong, art name Jiexi, was a Chinese scholar-official during the Ming dynasty. He held various high-ranking positions during the reign of the Jiajing Emperor in the mid-16th century, including m ...

. The evening before his execution, Yang Jisheng wrote a poem which was preserved on monuments and in later accounts of his life. It reads:

Wen Tianxiang

Wen Tianxiang

Wen Tianxiang (; June 6, 1236 – January 9, 1283), noble title Duke of Xin (), was a Chinese statesman, poet and politician in the last years of the Song dynasty#Southern Song, 1127–1279, Southern Song dynasty. For his resistance to Kublai K ...

(; 1236 – 1283) was a Chinese poet and politician in the last years of the Southern Song dynasty

The Song dynasty ( ) was an imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 960 to 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song, who usurped the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty and went on to conquer the rest of the Ten Kingdoms, endin ...

. He was executed by Kublai Khan

Kublai Khan (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder and first emperor of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty of China. He proclaimed the ...

for the uprisings against Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty ( ; zh, c=元朝, p=Yuáncháo), officially the Great Yuan (; Mongolian language, Mongolian: , , literally 'Great Yuan State'), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after Div ...

.

Tan Sitong

Tan Sitong (; March 10, 1865 – September 28, 1898) was a well-known Chinese politician, thinker, and reformist in the lateQing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China and an early modern empire in East Asia. The last imperial dynasty in Chinese history, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the ...

(1644–1911). He was executed at the age of 33 when the Hundred Days' Reform

The Hundred Days' Reform or Wuxu Reform () was a failed 103-day national, cultural, political, and educational reform movement that occurred from 11 June to 22 September 1898 during the late Qing dynasty. It was undertaken by the young Guangxu Emp ...

failed in 1898. Tan Sitong was one of the six gentlemen of the Hundred Days' Reform

Six gentlemen of the Hundred Days' Reform (), also known as Six gentlemen of Wuxu, were a group of six Chinese intellectuals whom the Empress Dowager Cixi had arrested and executed for their attempts to implement the Hundred Days' Reform. The mos ...

, and occupies an important place in modern Chinese history.

Japanese death poems

Style and technique

The poem's structure can be in one of many forms, including the two traditional forms in Japanese literature: '' kanshi'' or ''

The poem's structure can be in one of many forms, including the two traditional forms in Japanese literature: '' kanshi'' or ''waka

WAKA (channel 8) is a television station licensed to Selma, Alabama, United States, serving as the CBS affiliate for the Montgomery area. It is owned by Bahakel Communications alongside Tuskegee-licensed CW+ affiliate WBMM (channel 22); B ...

''. Sometimes they are written in the three-line, seventeen-syllable haiku

is a type of short form poetry that originated in Japan. Traditional Japanese haiku consist of three phrases composed of 17 Mora (linguistics), morae (called ''On (Japanese prosody), on'' in Japanese) in a 5, 7, 5 pattern; that include a ''kire ...

form, although the most common type of death poem (called a ''jisei'' ) is in the ''waka'' form called the ''tanka

is a genre of classical Japanese poetry and one of the major genres of Japanese literature.

Etymology

Originally, in the time of the influential poetry anthology (latter half of the eighth century AD), the term ''tanka'' was used to disti ...

'' (also called a ''jisei-ei'' ) which consists of five lines totaling 31 syllables (5-7-5-7-7)—a form that constitutes over half of surviving death poems (Ogiu, 317–318).

Poetry has long been a core part of Japanese tradition. Death poems are typically graceful, natural, and emotionally neutral, in accordance with the teachings of Buddhism

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

and Shinto

, also called Shintoism, is a religion originating in Japan. Classified as an East Asian religions, East Asian religion by Religious studies, scholars of religion, it is often regarded by its practitioners as Japan's indigenous religion and as ...

. Excepting the earliest works of this tradition, it has been considered inappropriate to mention death explicitly; rather, metaphor

A metaphor is a figure of speech that, for rhetorical effect, directly refers to one thing by mentioning another. It may provide, or obscure, clarity or identify hidden similarities between two different ideas. Metaphors are usually meant to cr ...

ical references such as sunsets, autumn or falling cherry blossom

The cherry blossom, or sakura, is the flower of trees in ''Prunus'' subgenus '' Cerasus''. ''Sakura'' usually refers to flowers of ornamental cherry trees, such as cultivars of ''Prunus serrulata'', not trees grown for their fruit (although ...

suggest the transience of life.

It was an ancient custom in Japan for literate persons to compose a ''jisei'' on their deathbed. One of the earliest was recited by Prince Ōtsu

was a Japanese poet and the son of Emperor Tenmu.

Viewed as the emperor's likely heir, Imperial Prince Ōtsu began attending to matters of state in 683, but was demoted in 685 when the court rank system was revised. Soon after Emperor Tenmu ...

, executed in 686. More examples of ''jisei'' are those of the famous haiku poet Bashō, the Japanese Buddhist monk Ryōkan

was a quiet and unconventional Sōtō Zen Buddhist monk who lived much of his life as a hermit. Ryōkan is remembered for his poetry and calligraphy, which present the essence of Zen life.

Early life

Ryōkan was born in the village of Izumo ...

, Edo Castle

is a flatland castle that was built in 1457 by Ōta Dōkan in Edo, Toshima District, Musashi Province. In modern times it is part of the Tokyo Imperial Palace in Chiyoda, Tokyo, and is therefore also known as .

Tokugawa Ieyasu established th ...

builder Ōta Dōkan

, also known as Ōta Sukenaga (太田 資長), was a Japanese samurai lord, poet and Buddhist monk. He took the tonsure as a Buddhist priest in 1478, and he also adopted the Buddhist name, Dōkan, by which he is known today.Time Out Magazine, Lt ...

, the monk Gesshū Sōko

Gesshū Sōko (1618–1696) was a Japanese Zen Buddhist teacher and a member of the Sōtō school of Zen in Japan. He studied under teachers of the lesser known, and more strictly monastic, Ōbaku School of Zen and contributed to a reformation of ...

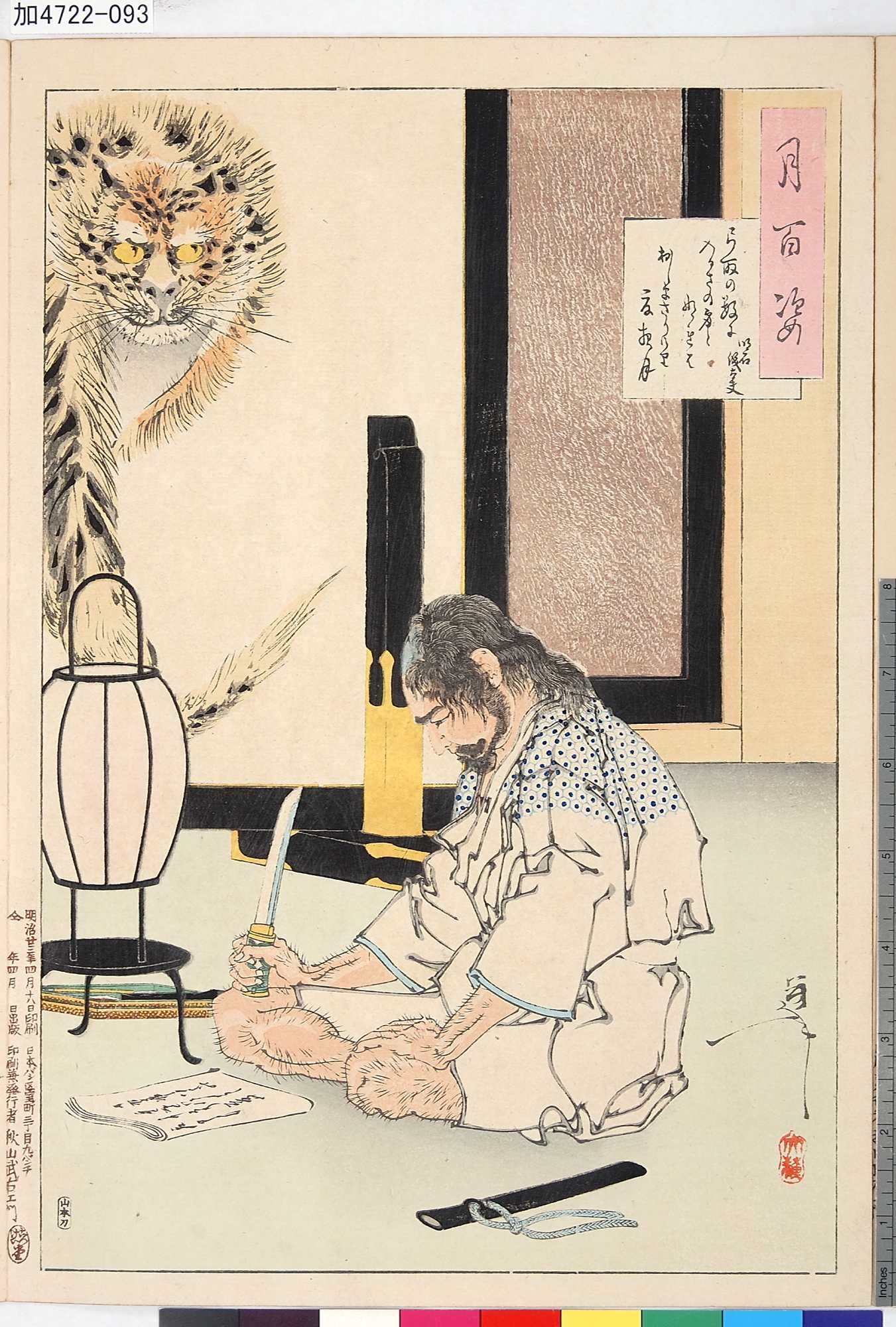

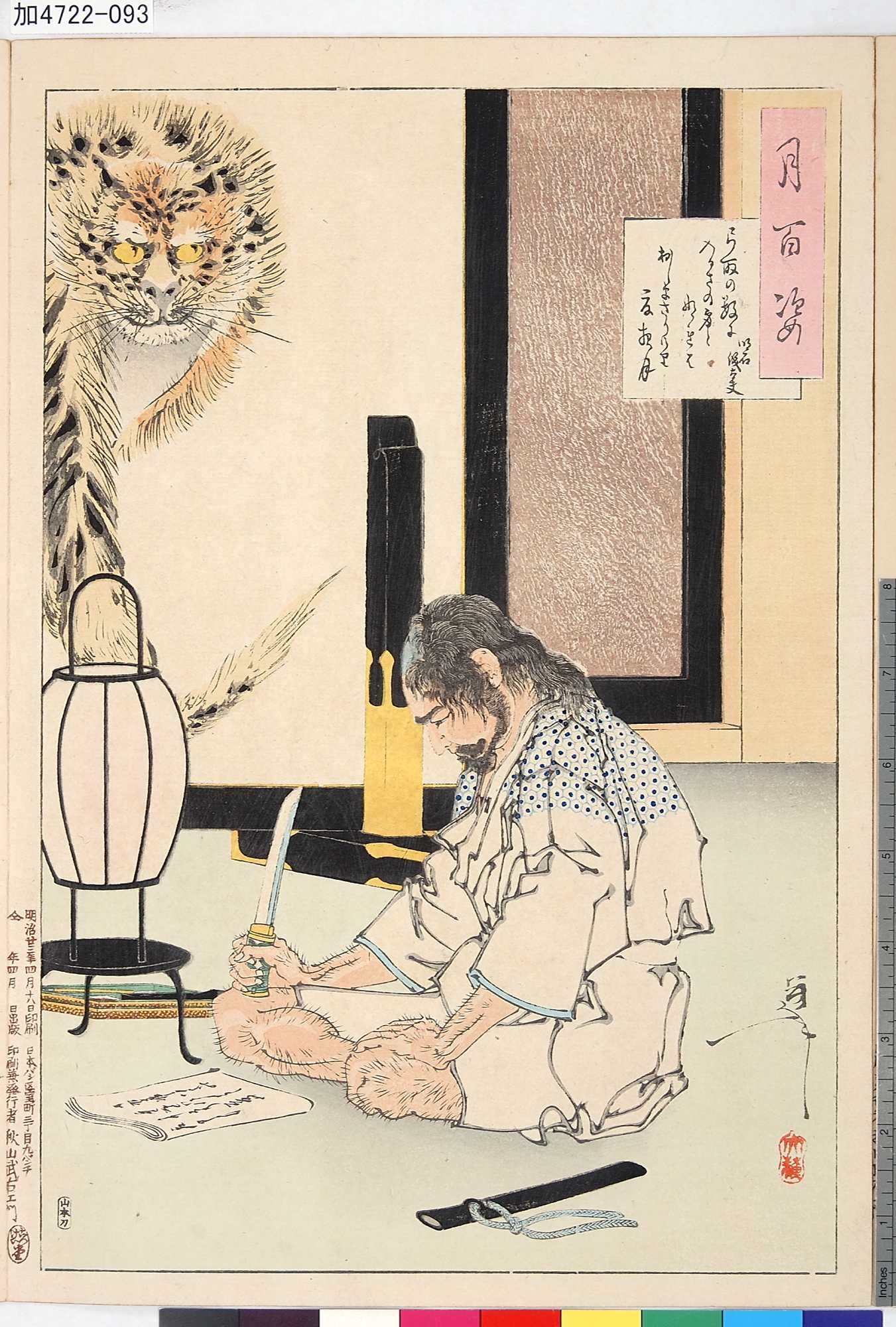

, and the woodblock master Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (; also named Taiso Yoshitoshi ; 30 April 1839 – 9 June 1892) was a Japanese printmaker.Louis-Frédéric, Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric. (2005)"Tsukoka Kōgyō"in ''Japan Encyclopedia,'' p. 1000.

Yoshitoshi ha ...

. The custom has continued into modern Japan. Some people left their death poems in multiple forms: Prince Ōtsu made both ''waka'' and ''kanshi'', and Sen no Rikyū

, also known simply as Rikyū, was a Japanese tea master considered the most important influence on the ''chanoyu'', the Japanese "Way of Tea", particularly the tradition of '' wabi-cha''. He was also the first to emphasize several key aspect ...

made both ''kanshi'' and ''kyōka

''Kyōka'' (, "wild" or "mad poetry") is a popular, parodic subgenre of the tanka form of Japanese poetry with a metre of 5-7-5-7-7. The form flourished during the Edo period (17th–18th centuries) and reached its zenith during the Tenmei era ...

''.

Fujiwara no Teishi

, also known as Sadako, was an empress consort of the Japanese Emperor Ichijō. She appears in the literary classic ''The Pillow Book'' written by her court lady Sei Shōnagon.

Biography

She was the first daughter of Fujiwara no Michitaka. ...

, the first empress of Emperor Ichijo, was also known as a poet. Before her death in childbirth in 1001, she wrote three ''waka'' to express her sorrow and love to her servant, Sei Shōnagon

, or , was a Japanese author, poet, and court lady who served the Empress Teishi (Sadako) around the year 1000, during the middle Heian period. She is the author of .

Name

Sei Shōnagon's actual given name is not known. It was the custom amon ...

, and the emperor. Teishi said that she would be entombed, rather than be cremated, so that she wrote that she will not become dust or cloud. The first one was selected into the poem collection Ogura Hyakunin Isshu

is a classical Japanese anthology of one hundred Japanese ''waka'' by one hundred poets. ''Hyakunin isshu'' can be translated to "one hundred people, one poem ach; it can also refer to the card game of ''uta-garuta'', which uses a deck compos ...

.

Tadamichi Kuribayashi

Tadamichi Kuribayashi was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army, diplomat, and commanding officer of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff. He is best known for having been the commander of the Japanese garrison at the battle of Iwo Jima ...

, the Japanese commander-in chief during the Battle of Iwo Jima

The was a major battle in which the United States Marine Corps (USMC) and United States Navy (USN) landed on and eventually captured the island of Iwo Jima from the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) during World War II. The American invasion, desi ...

, sent a final letter to Imperial Headquarters. In the message, General Kuribayashi apologized for failing to successfully defend Iwo Jima against the overwhelming forces of the United States military. At the same time, however, he expressed great pride in the heroism of his men, who, starving and thirsty, had been reduced to fighting with rifle butts and fists. He closed the message with three traditional death poems in ''waka'' form.

In 1970, writer Yukio Mishima

Kimitake Hiraoka ( , ''Hiraoka Kimitake''; 14 January 192525 November 1970), known by his pen name Yukio Mishima ( , ''Mishima Yukio''), was a Japanese author, poet, playwright, actor, model, Shintoist, Ultranationalism (Japan), ultranationalis ...

and his disciple Masakatsu Morita

was a Japanese political activist who killed himself via ''seppuku'' with Yukio Mishima in Tokyo.

Morita was the youngest child of the headmaster of an elementary school. Losing both parents at the age of three, Morita was cared for by his brot ...

composed death poems before their attempted coup at the Ichigaya

is an area in the eastern portion of Shinjuku, Tokyo, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan.

Places in Ichigaya

*Hosei University Ichigaya Campus

*Chuo University Graduate School

*Ministry of Defense (Japan), Ministry of Defense headquarters: Formerly Headqua ...

garrison in Tokyo, where they committed seppuku

, also known as , is a form of Japanese ritualistic suicide by disembowelment. It was originally reserved for samurai in their code of honor, but was also practiced by other Japanese people during the Shōwa era (particularly officers near ...

. Mishima wrote:

Although he did not compose any formal death poem on his deathbed, the last poem written by Bashō (1644–1694), recorded by his disciple Takarai Kikaku

Takarai Kikaku (; 1661–1707) also known as Enomoto Kikaku, was a Japanese haikai poet and among the most accomplished disciples of Matsuo Bashō.Katō, Shūichi and Sanderson, Don. ''A History of Japanese Literature: From the Man'yōshū to Mod ...

during his final illness, is generally accepted as his poem of farewell:

Despite the seriousness of the subject matter, some Japanese poets have employed levity or irony in their final compositions. The Zen monk Tokō (杜口; 1710–1795) commented on the pretentiousness of some ''jisei'' in his own death poem:

This poem by Moriya Sen'an (d. 1838) showed an expectation of an entertaining afterlife:

The final line, "hopefully the cask will leak" (''mori ya sen nan)'', is a play on the poet's name, Moriya Sen'an.

Written over a large calligraphic character 死 ''shi'', meaning Death, the Japanese Zen master Hakuin Ekaku

was one of the most influential figures in Japanese Zen Buddhism, who regarded bodhicitta, working for the benefit of others, as the ultimate concern of Zen-training. While never having received formal dharma transmission, he is regarded as th ...

(白隠 慧鶴; 1685–1768) wrote as his jisei:

Korean death poems

Besides Korean Buddhist monks, Confucian scholars calledseonbi

''Seonbi'' () were scholars during the Goryeo and Joseon periods of Korean history. They were generally seen as non-governmental servants of the public, who chose to pass on the benefits and authority of official power in order to develop and sha ...

s sometimes wrote death poems ( ). However, better-known examples are those written or recited by famous historical figures facing death when they were executed for loyalty to their former king or due to insidious plot. They are therefore impromptu verses, often declaring their loyalty or steadfastness. The following are some examples that are still learned by school children in Korea as models of loyalty. These examples are written in Korean sijo

''Sijo'' (, ) is a Korean traditional poetic form that emerged during the Goryeo dynasty, flourished during the Joseon dynasty, and is still written today. Bucolic, metaphysical, and cosmological themes are often explored. The three lines ave ...

(three lines of 3-4-3-4 or its variation) or in Hanja

Hanja (; ), alternatively spelled Hancha, are Chinese characters used to write the Korean language. After characters were introduced to Korea to write Literary Chinese, they were adapted to write Korean as early as the Gojoseon period.

() ...

five-syllable format (5-5-5-5 for a total of 20 syllables) of ancient Chinese poetry (五言詩).

Yi Kae

Yi Kae

Yi Kae (; 1417–1456) was a Korean scholar-official of the Joseon period who came from the ''yangban'' Hansan Yi clan and one of the six martyred ministers. He was the great-grandson of Goryeo period philosopher Yi Saek and third cousin of Y ...

(이개; 1417–1456) was one of "six martyred ministers

The six martyred ministers or Sayuksin () were six ministers of the Joseon Dynasty who were executed by King Sejo in 1456 for plotting to assassinate him and restore the former king Danjong to the throne.

The Six were Sŏng Sammun, Pak Pae ...

" who were executed for conspiring to assassinate King Sejo

Sejo (; 7 November 1417 – 23 September 1468), personal name Yi Yu (), sometimes known as Grand Prince Suyang (), was the seventh monarch of the Joseon dynasty of Korea. He was the second son of Sejong the Great and the uncle of King Danj ...

, who usurped the throne from his nephew Danjong. Sejo offered to pardon six ministers including Yi Kae and Sŏng Sammun if they would repent their crime and accept his legitimacy, but Yi Kae and all others refused. He recited the following poem in his cell before execution on June 8, 1456. In the following sijo

''Sijo'' (, ) is a Korean traditional poetic form that emerged during the Goryeo dynasty, flourished during the Joseon dynasty, and is still written today. Bucolic, metaphysical, and cosmological themes are often explored. The three lines ave ...

, "Lord" ( ) actually should read ''someone beloved or cherished'', meaning King Danjong in this instance.

Sŏng Sammun

Like Yi Kae,Sŏng Sammun

Sŏng Sammun (; 1418 – 8 June 1456) was a scholar-official of the early Joseon period who rose to prominence in the court of King Sejong the Great (r. 1418–1450). He was executed after being implicated in a plot to dethrone Sejo of Joseon, K ...

(1418–1456) was one of "six martyred ministers", and was the leader of the conspiracy to assassinate Sejo. He refused the offer of pardon and denied Sejo's legitimacy. He recited the following sijo in prison and the second one (five-syllable poem) on his way to the place of execution, where his limbs were tied to oxen and torn apart.

Jo Gwang-jo

Jo Gwang-jo

Jo Gwang-jo (, 23 August 1482 – 10 January 1520), also called by his art name Jeongam (), was a Korean Neo-Confucian scholar who pursued radical reforms during the reign of Jungjong of Joseon in the early 16th century.

He was framed with charg ...

(조광조; 1482–1519) was a neo-Confucian

Neo-Confucianism (, often shortened to ''lǐxué'' 理學, literally "School of Principle") is a Morality, moral, Ethics, ethical, and metaphysics, metaphysical Chinese philosophy influenced by Confucianism, which originated with Han Yu (768� ...

reformer who was framed by the conservative faction opposing his reforms in the Third Literati Purge of 1519. His political enemies slandered Jo to be disloyal by writing "Jo will become the king" ( , ) with honey on leaves so that caterpillars left behind the same phrase as if in supernatural manifestation. King Jungjong

Jungjong (; 25 April 1488 – 9 December 1544), personal name Yi Yeok (), firstly titled Grand Prince Jinseong (), was the 11th monarch of the Joseon dynasty of Korea. He succeeded to the throne after the deposition of his elder half-brother, ...

ordered his death by sending poison and abandoned Jo's reform measures. Jo, who had believed to the end that Jungjong would see his errors, wrote the following before drinking poison on December 20, 1519. Repetition of similar looking words is used to emphasize strong conviction in this five-syllable poem.

Chŏng Mong-ju

Chŏng Mong-ju

Chŏng Mong-ju (, January 13, 1337 – May 4, 1392), also known by his art name P'oŭn (), was a Korean statesman, diplomat, philosopher, poet, calligrapher and reformist of the Goryeo period. He was a major figure of opposition to the transit ...

(정몽주; 1337–1392) was an influential high minister of the Goryeo

Goryeo (; ) was a Korean state founded in 918, during a time of national division called the Later Three Kingdoms period, that unified and ruled the Korea, Korean Peninsula until the establishment of Joseon in 1392. Goryeo achieved what has b ...

dynasty when Yi Sŏng-gye

Taejo (; 4 November 1335 – 27 June 1408), personal name Yi Seong-gye (), later Yi Dan (), was the founder and first monarch of the Joseon dynasty of Korea. After overthrowing the Goryeo dynasty, he ascended to the throne in 1392 and abdi ...

sought to overthrow it and establish a new dynasty. When Yi Pang-wŏn

Taejong (; 16 May 1367 – 10 May 1422), personal name Yi Pangwŏn (), was the third monarch of the Joseon dynasty of Korea and the father of Sejong the Great. He was the fifth son of King Taejo, the founder of the dynasty. Before ascending t ...

, the son of Yi Sŏng-gye, asked Chŏng to support the founding of a new dynasty through a poem, Chŏng answered with a poem of his own reaffirming his loyalty to the falling Goryeo dynasty. Just as he suspected, he was assassinated the same night on April 4, 1392. Chŏng's death poem is the most famous in Korean history.

Hwang Hyun

Hwang Hyun (or Hyeon) (황현; 1855–1910) was aKorean independence activist

The following is a list of known people (including non-Koreans) that participated in the Korean independence movement against the colonization of Korea by Japan.

Early activists

People whose main independence activities were conducted before ...

in the early 20th century. His art name

An art name (pseudonym or pen name), also known by its native names ''hào'' (in Mandarin Chinese), ''gō'' (in Japanese), ' (in Korean), and ''tên hiệu'' (in Vietnamese), is a professional name used by artists, poets and writers in the Sinosp ...

was Maecheon (매천; 梅泉), and he was the author of the Maecheon Yarok (매천야록; 梅泉野錄), his diary of six volumes written from 1864 to 1910. Its detailed record of Korean historical events of the late 19th century makes it a notable primary source in the research and education about the late Joseon dynasty and Korean Empire

The Korean Empire, officially the Empire of Korea or Imperial Korea, was a Korean monarchical state proclaimed in October 1897 by King Gojong of the Joseon dynasty. The empire lasted until the Japanese annexation of Korea in August 1910.

Dur ...

, for example, it is used in the creation of modern textbooks. He showed great respect to other Korean independence activists, writing poems of mourning for activists who committed suicide after the signing of the Eulsa Treaty of 1905. However, in 1910, he himself would commit suicide after the annexation of Korea

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held to ...

. He left four death poems, with this poem, the third one being the most well-known nowadays.

Vietnamese death poems

In Vietnam, death poems are referred to as thơ tuyệt mệnh (chữ Hán

( , ) are the Chinese characters that were used to write Literary Chinese in Vietnam, Literary Chinese (; ) and Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary in Vietnamese language, Vietnamese. They were officially used in Vietnam after the Red River Delta region ...

: 詩絶命). These poems were commonly written in the Thất ngôn tứ tuyệt (七言四絶) form following Tang dynasty poetic form. This genre of poems were especially significant during the French conquest of Vietnam

The French conquest of Vietnam (1858–1885) was a series of military expeditions that pitted the Second French Empire, later the French Third Republic, against the Vietnamese empire of Nguyễn dynasty, Đại Nam in the mid-late 19th century. It ...

. The poems can be either written in Hán văn

Literary Chinese ( Vietnamese: , ; chữ Hán: 漢文, 文言) was the medium of all formal writing in Vietnam for almost all of the country's history until the early 20th century, when it was replaced by vernacular writing in Vietnamese using t ...

(漢文; Literary Chinese

Classical Chinese is the language in which the classics of Chinese literature were written, from . For millennia thereafter, the written Chinese used in these works was imitated and iterated upon by scholars in a form now called Literary ...

) or Vietnamese written in chữ Nôm

Chữ Nôm (, ) is a logographic writing system formerly used to write the Vietnamese language. It uses Chinese characters to represent Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary and some native Vietnamese words, with other words represented by new characters ...

(𡨸喃).

Hồ Huân Nghiệp

Hồ Huân Nghiệp (胡勳業; 1829–1864) was an influential scholar during theNguyễn dynasty

The Nguyễn dynasty (, chữ Nôm: 茹阮, chữ Hán: 朝阮) was the last List of Vietnamese dynasties, Vietnamese dynasty, preceded by the Nguyễn lords and ruling unified Vietnam independently from 1802 until French protectorate in 1883 ...

. He was also well known for being one of the first to fight against the French. The French eventually captured him in Gia Định (嘉定; present-day Ho Chi Minh City). Before he was executed by the French, he washed his face, fixed his turban, and recited four verses of poetry before being beheaded.

Hoàng Phan Thái

Hoàng Phan Thái (黄潘泰; 1819–1865) was a reformist and revolutionary during the reign of EmperorTự Đức

Tự Đức (, vi-hantu, :wikt:嗣, 嗣:wikt:德, 德, , 22 September 1829 – 19 July 1883) (personal name: Nguyễn Phúc Hồng Nhậm, also Nguyễn Phúc Thì) was the fourth emperor of the Nguyễn dynasty of Vietnam, and the country's la ...

(嗣德帝). Advocating for the modernization of Vietnam, he proposed the creation of a new political party to implement reforms and challenge the stagnation of the Nguyễn dynasty. To rally support for his cause, he adopted the title Grand General of the Eastern Sea (東海大將軍; Đông Hải Đại Tướng Quân). In collaboration with Lê Duy Uẩn (黎維蘊) and Nguyễn Thịnh (阮盛), Hoàng Phan Thái sought to overthrow Tự Đức's regime through a military uprising and to resist the French colonialists. Their strategy involved leveraging coastal forces and rallying support in the Nghệ Tĩnh region, with plans to weaken the Nguyễn dynasty's central power. Despite their efforts, the uprising ultimately failed, and Hoàng Phan Thái was captured and executed for his revolutionary activities. Before his death, he wrote a death poem.

Lưu Thường

Lưu Thường (劉常; 1345–1388) was a Vietnamese official of theTrần dynasty

The Trần dynasty (Vietnamese language, Vietnamese: Nhà Trần, chữ Nôm: 茹陳; Vietnamese language, Vietnamese: triều Trần, chữ Hán: ikt:朝ikt:陳, 朝wikt:陳, 陳), officially Đại Việt (Chữ Hán: 大越), was a List ...

. He is most notably remembered for his involvement in a failed plot to rescue Trần Phế Đế

Trần Phế Đế (6 March 1361 – 6 December 1388), given name Trần Hiện, was the tenth emperor of the Trần dynasty who reigned Đại Việt from 1377 to 1388. After his father's death in Battle of Đồ Bàn in January 1377, Ph� ...

(陳廢帝). In 1388, Hồ Quý Ly

Hồ Quý Ly ( vi-hantu, 胡季犛, 1336 – 1407?) ruled Đại Ngu (Vietnam) from 1400 to 1401 as the founding emperor of the short-lived Hồ dynasty. Quý Ly rose from a post as an official served the court of the ruling Trần dynasty and ...

(胡季犛), a powerful and ambitious official, manipulated the retired emperor, Trần Nghệ Tông

Trần Nghệ Tông ( vi-hantu, 陳藝宗, 20 December 1321 – 6 January 1395), given name Trần Phủ (陳暊), was the eighth emperor of the Trần dynasty who ruled Vietnam from 1370 to 1372.

Biography As prince

Nghệ Tông was born in 132 ...

(陳藝宗) into forcing Trần Phế Đế to commit suicide by hanging. Lưu Thường, along with Nguyễn Khoái (阮快) and Nguyễn Vân Nhi (阮雲兒), planned to save Trần Phế Đế, but their efforts were discovered, and all participants in the plot were executed. Before his death, Lưu Thường wrote a famous death poem that reflected his unwavering loyalty and sense of righteousness. His death poem is found in the eighth volume (卷之八) of Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư

The ''Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư'' ( vi-hantu, 大越史記全書; ; ''Complete Annals of Đại Việt'') is the official national chronicle of the Đại Việt, that was originally compiled by the royal historian Ngô Sĩ Liên under ...

.

Nguyễn Sư Phó

Nguyễn Sư Phó (阮瑡傅; 1458–1519) was a Vietnamese court official of theLê dynasty

The Lê dynasty, also known in historiography as the Later Lê dynasty (, chữ Hán: 朝後黎, chữ Nôm: 茹後黎), officially Đại Việt (; Chữ Hán: 大越), was the longest-ruling List of Vietnamese dynasties, Vietnamese dynasty, h ...

. He was well known for installing Lê Bảng (黎榜) as the new emperor (Đại Đức; 大德) after a series of rebellions and unrest. Around March 1519, Trịnh Tuy (鄭綏) deposed Lê Bảng and installed Bảng's younger brother, Lê Do (黎槱), as emperor, changing the era name to Thiên Hiến (天憲). In July 1519, during a heavy rainstorm, Lê Chiêu Tông

Lê Chiêu Tông ( 黎 昭 宗, 4 October 1506 – 18 December 1526; also called Lê Y, 黎 椅 or 黎 譓) was an emperor of the Lê dynasty of Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the ...

's general, Mạc Đăng Dung

Mạc Đăng Dung (chữ Hán : 莫 登 庸; 23 November 1483 – 22 August 1541), also known by his temple name Mạc Thái Tổ (), was an emperor of Vietnam and the founder of the Mạc dynasty. Previously a captain of the imperial guard (Pra ...

(莫登庸), led both naval and land forces to besiege Emperor Thiên Hiến at Từ Liêm. Nguyễn Sư Phó fled to Ninh Sơn but were captured by Lê Chiêu Tông's forces and taken prisoner. Before Nguyễn Sư Phó was executed, he wrote a death poem. His death poem is found in the fifteenth volume (卷之十五) of Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư.

Phan Thanh Giản

Phan Thanh Giản

Phan Thanh Giản (November 11, 1796– August 4, 1867) was a Grand Counsellor at the Nguyễn dynasty, Nguyễn court in Vietnam. He led an diplomatic mission to Second French Empire, France in 1863, and Suicide, committed suicide when Fran ...

was a Nguyễn dynasty

The Nguyễn dynasty (, chữ Nôm: 茹阮, chữ Hán: 朝阮) was the last List of Vietnamese dynasties, Vietnamese dynasty, preceded by the Nguyễn lords and ruling unified Vietnam independently from 1802 until French protectorate in 1883 ...

official who held position of Hiệp biện Đại học sĩ (協辦大學士; Assistant to the Grand Secretariat). He was most well known for negotiating the Treaty of Saigon Treaty of Saigon may refer to:

* Treaty of Saigon (1862), between France and Vietnam

* Treaty of Saigon (1874), between France and Vietnam

{{dab ...

which led to three provinces being ceded to the France. On 20 June 1867, the French captured the city of Vĩnh Long

Vĩnh Long ɨn˨˩˦:lawŋ˧˧is a city and the capital of Vĩnh Long Province in Vietnam's Mekong Delta. Geography

Vĩnh Long covers and has a population of 200,120 (as of 2018). The name was spelled 永 隆 ("eternal prosperity") in the form ...

. Phan Thanh Giản who had been to France and knew overwhelming military strength of the French, surrendered the citadel without resistance, under the condition that the French would ensure the safety of the local population. After the fall of the citadel, Phan Thanh Giản wrote a death poem and committed suicide at the age of 72.

Nguyễn Trung Trực

Nguyễn Trung Trực

Nguyễn Trung Trực (183827 October 1868), born Nguyễn Văn Lịch, was a Vietnamese fisherman who organized and led village militia forces which fought against French colonial forces in the Mekong Delta in southern Vietnam in the 1860s. He ...

(阮忠直; 1838–1868) was a Vietnamese fisherman who organized and led village militia forces which fought against French colonial forces in the Mekong Delta in southern Vietnam in the 1860s. After Nguyễn Trung Trực captured the French citadel in Rạch Giá

Rạch Giá () is a provincial city and the capital city of Kiên Giang province, Vietnam. It is located on the Eastern coast of the Gulf of Thailand, southwest of Ho Chi Minh City. East of city, it borders Tân Hiệp and Châu Thành town, t ...

, the French had taken his mother hostage. The French ended up regaining control of the citadel and captured Nguyễn Trung Trực. Nguyễn Trung Trực was beheaded by the French at Rạch Giá on October 27, 1868. Nguyễn Trung Trực wrote a death poem shortly before his death.

See also

*Elegy

An elegy is a poem of serious reflection, and in English literature usually a lament for the dead. However, according to ''The Oxford Handbook of the Elegy'', "for all of its pervasiveness ... the 'elegy' remains remarkably ill defined: sometime ...

* Epitaph

An epitaph (; ) is a short text honoring a deceased person. Strictly speaking, it refers to text that is inscribed on a tombstone or plaque, but it may also be used in a figurative sense. Some epitaphs are specified by the person themselves be ...

* Graveyard Poets

* Lament

A lament or lamentation is a passionate expression of grief, often in music, poetry, or song form. The grief is most often born of regret, or mourning. Laments can also be expressed in a verbal manner in which participants lament about something ...

* Last words

Last words are the final utterances before death. The meaning is sometimes expanded to somewhat earlier utterances.

Last words of famous or infamous people are sometimes recorded (although not always accurately), which then became a historical an ...

* ''Mi último adiós

"Mi último adiós" () is a poem written by Philippine national hero Dr. José Rizal before his execution by firing squad on December 30, 1896. The piece was one of the last notes he wrote before his death. Another that he had written was found i ...

''

* Ryōkan

was a quiet and unconventional Sōtō Zen Buddhist monk who lived much of his life as a hermit. Ryōkan is remembered for his poetry and calligraphy, which present the essence of Zen life.

Early life

Ryōkan was born in the village of Izumo ...

* Suicide note

A suicide note or death note is a message written by a person who intends to die by suicide.

A study examining Japanese suicide notes estimated that 25–30% of suicides are accompanied by a note. However, incidence rates may depend on ethnic ...

* Xie Lingyun

Xie Lingyun (; 385–433) and also known as the Duke of Kangle (康樂公) was one of the foremost Chinese poets towards the end of the Southern and Northern Dynasties and continued in poetic fame through the beginning of the Six Dynasties, ...

*Yuan Chonghuan

Yuan Chonghuan (; 6 June 1584 – 22 September 1630), courtesy name Yuansu, art name Ziru, was a Chinese politician, military general and writer who served under the Ming dynasty. Remembered as a national hero of Ming China and widely regarded ...

*Chinese Chán

Chan (; of ), from Sanskrit '' dhyāna'' (meaning " meditation" or "meditative state"), is a Chinese school of Mahāyāna Buddhism. It developed in China from the 6th century CE onwards, becoming especially popular during the Tang and Song ...

* Japanese Zen

:''See also Zen for an overview of Zen, Chan Buddhism for the Chinese origins, and Sōtō, Rinzai school, Rinzai and Ōbaku for the three main schools of Zen in Japan''

Japanese Zen refers to the Japanese forms of Zen, Zen Buddhism, an orig ...

* ''Mono no aware

, , and also translated as , or , is a Japanese idiom for the awareness of , or transience of things, and both a transient gentle sadness (or wistfulness) at their passing as well as a longer, deeper gentle sadness about this state being the re ...

''

* Wabi-sabi

In traditional Japanese aesthetics, centers on the acceptance of transience and imperfection. It is often described as the appreciation of beauty that is "imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete". It is prevalent in many forms of Japanese ...

* Memento mori

(Latin for "remember (that you have) to die")

* Swan song

The swan song (; ) is a metaphorical phrase for a final gesture, effort, or performance given just before death or retirement. The phrase refers to an ancient belief that swans sing a beautiful song just before their death while they have been ...

Notes

References

Further reading

* Blackman, Sushila (1997). ''Graceful Exits: How Great Beings Die: Death Stories of Tibetan, Hindu & Zen Masters''. Weatherhill, Inc.: USA, New York, New York. * Hoffmann, Yoel (1986). ''Japanese Death Poems: Written by Zen Monks and Haiku Poets on the Verge of Death''. Charles E. Tuttle Company: USA, Rutland, Vermont.External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Death Poem Genres of poetry Death customs Japanese poetryPoem

Poetry (from the Greek language, Greek word ''poiesis'', "making") is a form of literature, literary art that uses aesthetics, aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meaning (linguistics), meanings in addition to, or in ...

Suicide by seppuku

Poems about death

Buddhism and death