The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a

religious order

A religious order is a subgroup within a larger confessional community with a distinctive high-religiosity lifestyle and clear membership. Religious orders often trace their lineage from revered teachers, venerate their Organizational founder, ...

of

clerics regular

In the canon law of the Catholic Church, clerics regular or clerks regular are clerics (mostly priests) who are members of a religious order under a rule of life (regular). Clerics regular differ from canons regular in that they devote themselves ...

of

pontifical right

In Catholicism, "of pontifical right" is the term given to ecclesiastical institutions (religious and secular institutes, societies of apostolic life) either created by the Holy See, or approved by it with the formal decree known by the Latin na ...

for men in the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

headquartered in

Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

. It was founded in 1540 by

Ignatius of Loyola

Ignatius of Loyola ( ; ; ; ; born Íñigo López de Oñaz y Loyola; – 31 July 1556), venerated as Saint Ignatius of Loyola, was a Basque Spaniard Catholic priest and theologian, who, with six companions, founded the religious order of the S ...

and six companions, with the approval of

Pope Paul III

Pope Paul III (; ; born Alessandro Farnese; 29 February 1468 – 10 November 1549) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 October 1534 to his death, in November 1549.

He came to the papal throne in an era follo ...

. The Society of Jesus is the largest

religious order

A religious order is a subgroup within a larger confessional community with a distinctive high-religiosity lifestyle and clear membership. Religious orders often trace their lineage from revered teachers, venerate their Organizational founder, ...

in the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and has played significant role in education, charity, humanitarian acts and global policies. The Society of Jesus is engaged in evangelization and apostolic ministry in 112 countries. Jesuits work in education, research, and cultural pursuits. They also conduct retreats, minister in hospitals and parishes, sponsor direct social and humanitarian works, and promote

ecumenical dialogue.

The Society of Jesus is consecrated under the

patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, art patronage refers to the support that princes, popes, and other wealthy and influential people ...

of Madonna della Strada, a title of the

Blessed Virgin Mary

Mary was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Joseph and the mother of Jesus. She is an important figure of Christianity, venerated under titles of Mary, mother of Jesus, various titles such as Perpetual virginity ...

, and it is led by a

superior general

A superior general or general superior is the leader or head of an 'order' of religious persons (nuns, priests, friars, etc) or, in other words, of a 'religious institute' in the Catholic Church, and in some other Christian denominations. The super ...

. The headquarters of the society, its

general curia, is in Rome. The historic curia of Ignatius is now part of the attached to the

Church of the Gesù

The Church of the Gesù (, ), officially named (), is a church located at Piazza del Gesù in the Pigna (rione of Rome), Pigna ''Rioni of Rome, rione'' of Rome, Italy. It is the mother church of the Society of Jesus (best known as Jesuits). Wi ...

, the Jesuit

mother church

Mother church or matrice is a term depicting the Christian Church as a mother in her functions of nourishing and protecting the believer. It may also refer to the primary church of a Christian denomination or diocese, i.e. a cathedral church, or ...

.

Members of the Society of Jesus make profession of "perpetual poverty, chastity, and obedience" and "promise a special obedience to the sovereign pontiff in regard to the missions." A Jesuit is expected to be totally available and obedient to his superiors, accepting orders to go anywhere in the world, even if required to live in extreme conditions. Ignatius, its leading founder, was a nobleman who had a military background. The opening lines of the founding document of the Society of Jesus accordingly declare that it was founded for "whoever desires to serve as a soldier of God, to strive especially for the defense and propagation of the faith, and for the progress of souls in Christian life and doctrine". Jesuits are thus sometimes referred to colloquially as "God's soldiers", "God's marines", or "the Company". The Society of Jesus participated in the

Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

and, later, in the implementation of the

Second Vatican Council

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the or , was the 21st and most recent ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. The council met each autumn from 1962 to 1965 in St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City for session ...

.

Jesuit

missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group who is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Miss ...

established missions around the world from the 16th to the 18th century and had both successes and failures in

Christianizing the native peoples. The Jesuits have always been controversial within the Catholic Church and have frequently clashed with secular governments and institutions. Beginning in 1759, the Catholic Church expelled Jesuits from most countries in Europe and from European colonies.

Pope Clement XIV

Pope Clement XIV (; ; 31 October 1705 – 22 September 1774), born Giovanni Vincenzo Antonio Ganganelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 May 1769 to his death in September 1774. At the time of his elec ...

officially

suppressed the order in 1773. In 1814, the Church lifted the suppression.

History

Foundation

Ignatius of Loyola

Ignatius of Loyola ( ; ; ; ; born Íñigo López de Oñaz y Loyola; – 31 July 1556), venerated as Saint Ignatius of Loyola, was a Basque Spaniard Catholic priest and theologian, who, with six companions, founded the religious order of the S ...

, a

Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

nobleman from the

Pyrenees

The Pyrenees are a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. They extend nearly from their union with the Cantabrian Mountains to Cap de Creus on the Mediterranean coast, reaching a maximum elevation of at the peak of Aneto. ...

area of northern Spain, founded the society after discerning his spiritual vocation while recovering from a wound sustained in the

Battle of Pamplona.

On 15 August 1534, Ignatius of Loyola (born Íñigo López de Loyola), a Spaniard from the

Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

city of

Loyola, and six others mostly of

Castilian origin, all students at the

University of Paris

The University of Paris (), known Metonymy, metonymically as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793–1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated wit ...

, met in

Montmartre

Montmartre ( , , ) is a large hill in Paris's northern 18th arrondissement of Paris, 18th arrondissement. It is high and gives its name to the surrounding district, part of the Rive Droite, Right Bank. Montmartre is primarily known for its a ...

outside Paris, in a crypt beneath the church of

Saint Denis, now

Saint Pierre de Montmartre, to pronounce promises of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Ignatius' six companions were:

Francisco Xavier from

Navarre

Navarre ( ; ; ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre, is a landlocked foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Autonomous Community, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and New Aquitaine in France. ...

(

modern Spain),

Alfonso Salmeron,

Diego Laínez

Diego Laynez, S.J. (1512 – 19 January 1565; first name sometimes translated James, Jacob; surname also spelled Laines, Lainez, Laínez) was a Spanish Society of Jesus, Jesuit priest and theology, theologian, a New Christian (of converted Jewis ...

,

Nicolás Bobadilla from

Castile (

modern Spain),

Peter Faber

Peter Faber, SJ (, ) (13 April 1506 – 1 August 1546) was a Savoyard Catholic priest, theologian and co-founder of the Society of Jesus, along with Ignatius of Loyola and Francis Xavier. Pope Francis announced his canonization in 2013.

Life Ea ...

from

Savoy

Savoy (; ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps. Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south and west and to the Aosta Vall ...

, and

Simão Rodrigues from

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

.

The meeting is commemorated in the

Martyrium of Saint Denis, Montmartre. They called themselves the , and also or "Friends in the Lord", because they felt "they were placed together by Christ." The name "company" had echoes of the military (reflecting perhaps Ignatius' background as captain in the Spanish army) as well as of discipleship (the "companions" of Jesus). The Spanish "company" would be translated into Latin as like in , a partner or comrade. From this came "Society of Jesus" (SJ) by which they would be known more widely.

Religious orders established in the medieval era were named after particular men:

Francis of Assisi

Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone ( 1181 – 3 October 1226), known as Francis of Assisi, was an Italians, Italian Mysticism, mystic, poet and Friar, Catholic friar who founded the religious order of the Franciscans. Inspired to lead a Chris ...

(Franciscans);

Domingo de Guzmán, later canonized as Saint Dominic (Dominicans); and

Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

(Augustinians). Ignatius of Loyola and his followers appropriated the name of Jesus for their new order, provoking resentment by other orders who considered it presumptuous. The resentment was recorded by Jesuit

José de Acosta of a conversation with the Archbishop of Santo Domingo.

In the words of one historian: "The use of the name Jesus gave great offense. Both on the Continent and in England, it was denounced as blasphemous; petitions were sent to kings and to civil and ecclesiastical tribunals to have it changed; and even

Pope Sixtus V

Pope Sixtus V (; 13 December 1521 – 27 August 1590), born Felice Piergentile, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 April 1585 to his death, in August 1590. As a youth, he joined the Franciscan order, where h ...

had signed a Brief to do away with it." But nothing came of all the opposition; there were already congregations named after the Trinity and as "God's daughters".

In 1537, the seven travelled to Italy to seek papal approval for their

order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

...

. Pope Paul III gave them a commendation, and permitted them to be ordained priests. These initial steps led to the official founding in 1540.

They were ordained in

Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

by the

bishop of Arbe on 24 June. They devoted themselves to preaching and charitable work in

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

. The

Italian War of 1536–1538 renewed between

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain (as Charles I) from 1516 to 1556, and Lord of the Netherlands as titular Duke of Burgundy (as Charles II) ...

, Venice, the Pope, and the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, had rendered any journey to

Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

impossible.

Again in 1540, they presented the project to Paul III. After months of dispute, a congregation of

cardinals reported favourably upon the Constitution presented, and Paul III confirmed the order through the bull ("To the Government of the Church Militant"), on 27 September 1540. This is the founding document of the Society of Jesus as an official Catholic religious order. Ignatius was chosen as the first

Superior General

A superior general or general superior is the leader or head of an 'order' of religious persons (nuns, priests, friars, etc) or, in other words, of a 'religious institute' in the Catholic Church, and in some other Christian denominations. The super ...

. Paul III's bull had limited the number of its members to sixty. This limitation was removed through the bull of Julius III in 1550.

In 1543,

Peter Canisius

Peter Canisius (; 8 May 1521 – 21 December 1597) was a Dutch Jesuit priest known for his strong support for the Catholic faith during the Protestant Reformation in Germany, Austria, Bohemia, Moravia, Switzerland and the British Isles. The ...

entered the company. Ignatius sent him to Messina, where he founded the first Jesuit college in

Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

.

Ignatius laid out his original vision for the new order in the "Formula of the Institute of the Society of Jesus",

[Text of the Formula of the Institute (1540)](_blank)

, Boston College

Boston College (BC) is a private university, private Catholic Jesuits, Jesuit research university in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1863 by the Society of Jesus, a Catholic Religious order (Catholic), religious order, t ...

, Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, accessed 31 May 2021 which is "the fundamental charter of the order, of which all subsequent official documents were elaborations and to which they had to conform". He ensured that his formula was contained in two

papal bull

A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by the pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the leaden Seal (emblem), seal (''bulla (seal), bulla'') traditionally appended to authenticate it.

History

Papal ...

s signed by Pope Paul III in 1540 and by Pope Julius III in 1550.

The formula expressed the nature, spirituality, community life, and apostolate of the new religious order. Its famous opening statement echoed Ignatius' military background:

In fulfilling the mission of the "Formula of the Institute of the Society", the first Jesuits concentrated on a few key activities. First, they founded schools throughout Europe. Jesuit teachers were trained in both

classical studies

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek and Roman literature and their original languages ...

and

theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

, and their schools reflected this. These schools taught with a balance of Aristotelian methods with mathematics.

Second, they sent out missionaries across the globe to

evangelize those peoples who had not yet heard the

Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christianity, Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the second century Anno domino, AD the term (, from which the English word originated as a calque) came to be used also for the books in which the message w ...

, founding missions in widely diverse regions such as modern-day

Paraguay

Paraguay, officially the Republic of Paraguay, is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the Argentina–Paraguay border, south and southwest, Brazil to the Brazil–Paraguay border, east and northeast, and Boli ...

, Japan,

Ontario

Ontario is the southernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Located in Central Canada, Ontario is the Population of Canada by province and territory, country's most populous province. As of the 2021 Canadian census, it ...

, and

Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

. One of the original seven arrived in India already in 1541. Finally, though not initially formed for the purpose, they aimed to stop

Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

from spreading and to preserve communion with

Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

and the

pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

. The zeal of the Jesuits overcame the movement toward Protestantism in the

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

and southern

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

.

Ignatius wrote the Jesuit ''Constitutions'', adopted in 1553, which created a centralised organization and stressed acceptance of any mission to which the pope might call them. His main principle became the unofficial Jesuit motto: ("For the greater glory of God"). This phrase is designed to reflect the idea that any work that is not evil can be meritorious for the spiritual life if it is performed with this intention, even things normally considered of little importance.

The Society of Jesus is classified among institutes as an order of

clerks regular, that is, a body of priests organized for

apostolic work, and following a

religious

Religion is a range of social- cultural systems, including designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relate humanity to supernatural ...

rule.

The term ''Jesuit'' (of 15th-century origin, meaning "one who used too frequently or appropriated the name of Jesus") was first applied to the society in reproach (1544–1552). The term was never used by Ignatius of Loyola, but over time, members and friends of the society adopted the name with a positive meaning.

While the order is limited to men,

Joanna of Austria, Princess of Portugal

Joanna of Austria (in Castilian, ''Doña Juana de Austria''; in Portuguese, ''Dona Joana de Áustria'', 24 June 1535 – 7 September 1573) was Princess of Portugal by marriage to João Manuel, Prince of Portugal. She served as regent of ...

, favored the order and she is reputed to have been admitted surreptitiously under a male pseudonym.

Early works

The Jesuits were founded just before the

Council of Trent

The Council of Trent (), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation at the time, it has been described as the "most ...

(1545–1563) and ensuing

Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

that would introduce reforms within the Catholic Church, and so counter the

Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

throughout Catholic Europe.

Ignatius and the early Jesuits did recognize, though, that the hierarchical church was in dire need of reform. Some of their greatest struggles were against corruption,

venality, and spiritual lassitude within the Catholic Church. Ignatius insisted on a high level of academic preparation for the clergy in contrast to the relatively poor education of much of the clergy of his time. The Jesuit vow against "ambitioning prelacies" can be seen as an effort to counteract another problem evidenced in the preceding century.

Ignatius and the Jesuits who followed him believed that the reform of the church had to begin with the conversion of an individual's heart. One of the main tools the Jesuits have used to bring about this conversion is the Ignatian retreat, called the

Spiritual Exercises. During a four-week period of silence, individuals undergo a series of directed

meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique to train attention and awareness and detach from reflexive, "discursive thinking", achieving a mentally clear and emotionally calm and stable state, while not judging the meditat ...

s on the purpose of life and contemplations on the life of Christ. They meet regularly with a

spiritual director

Spiritual direction is the practice of being with people as they attempt to deepen their relationship with the divinity, divine, or to learn and grow in their personal spirituality. The person seeking direction shares stories of their encounters ...

who guides their choice of exercises and helps them to develop a more discerning love for Christ.

The retreat follows a "Purgative-Illuminative-Unitive" pattern in the tradition of the spirituality of

John Cassian

John Cassian, also known as John the Ascetic and John Cassian the Roman (, ''Ioannes Cassianus'', or ''Ioannes Massiliensis''; Greek: Ίωάννης Κασσιανός ό Ερημίτης; – ), was a Christian monk and theologian celebrated ...

and the

Desert Fathers

The Desert Fathers were early Christian hermits and ascetics, who lived primarily in the Wadi El Natrun, then known as ''Skete'', in Roman Egypt, beginning around the Christianity in the ante-Nicene period, third century. The ''Sayings of the Dese ...

. Ignatius' innovation was to make this style of contemplative

mysticism

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute (philosophy), Absolute, but may refer to any kind of Religious ecstasy, ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or Spirituality, spiritual meani ...

available to all people in active life. He used it as a means of rebuilding the spiritual life of the church. The Exercises became both the basis for the training of Jesuits and one of the essential ministries of the order: giving the exercises to others in what became known as "retreats".

The Jesuits' contributions to the late

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

were significant in their roles both as a missionary order and as the first religious order to operate colleges and universities as a principal and distinct ministry.

By the time of Ignatius' death in 1556, the Jesuits were already operating a network of 74 colleges on three continents. A precursor to

liberal education

A liberal education is a system or course of education suitable for the cultivation of a free () human being. It is based on the medieval concept of the liberal arts or, more commonly now, the liberalism of the Age of Enlightenment. It has been d ...

, the Jesuit plan of studies incorporated the Classical teachings of

Renaissance humanism into the

Scholastic structure of Catholic thought.

This method of teaching was important in the context of the Scientific Revolution, as these universities were open to teaching new scientific and mathematical methodology. Further, many important thinkers of the Scientific Revolution were educated by Jesuit universities.

In addition to the teachings of

faith

Faith is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or concept. In the context of religion, faith is " belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

According to the Merriam-Webster's Dictionary, faith has multiple definitions, inc ...

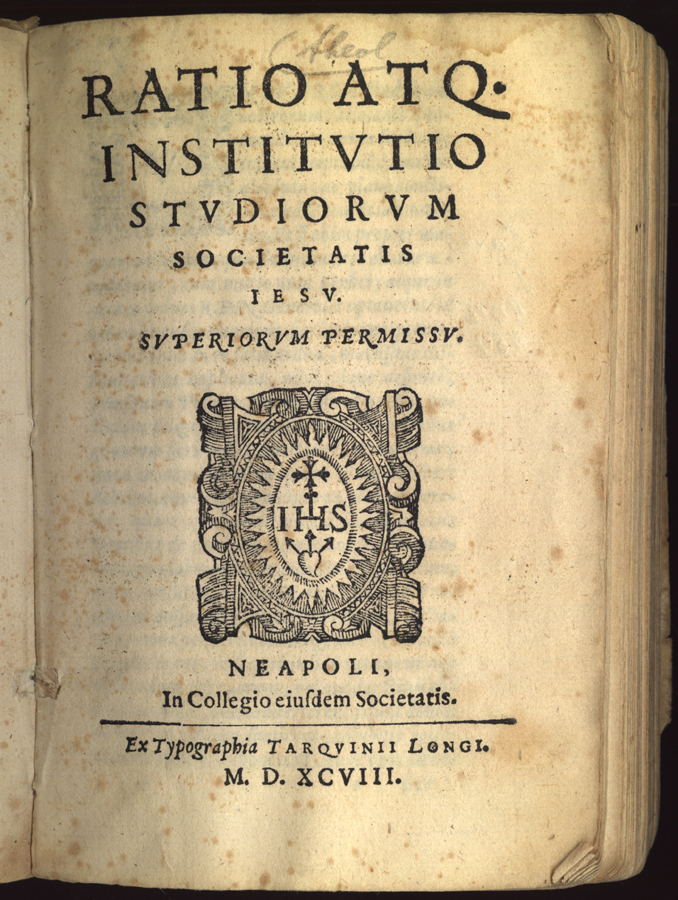

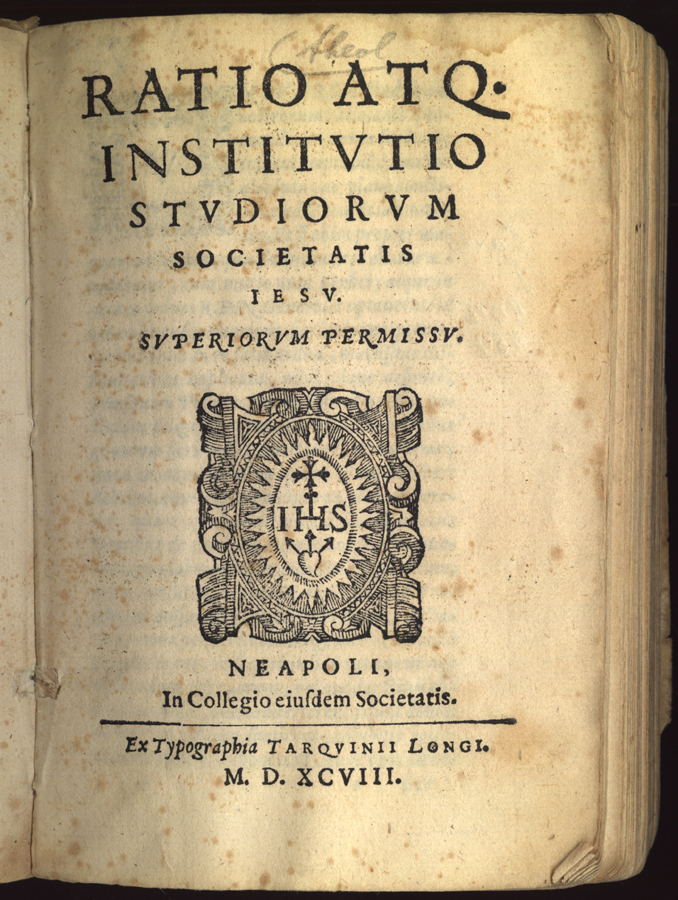

, the Jesuit (1599) would standardize the study of

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

,

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, classical literature, poetry, and philosophy as well as non-European languages, sciences, and the arts. Jesuit schools encouraged the study of

vernacular literature

Vernacular literature is literature written in the vernacular—the speech of the "common people".

In the European tradition, this effectively means literature not written in Latin or Koine Greek. In this context, vernacular literature appeared ...

and

rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

, and thereby became important centres for the training of lawyers and public officials.

The Jesuit schools played an important part in winning back to Catholicism a number of European countries which had for a time been predominantly Protestant, notably

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

and

Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

. Today, Jesuit colleges and universities are located in over one hundred nations around the world. Under the notion that God can be encountered through created things and especially art, they encouraged the use of ceremony and decoration in Catholic ritual and devotion. Perhaps as a result of this appreciation for art, coupled with their spiritual practice of "finding God in all things", many early Jesuits distinguished themselves in the visual and

performing arts

The performing arts are arts such as music, dance, and drama which are performed for an audience. They are different from the visual arts, which involve the use of paint, canvas or various materials to create physical or static art objects. P ...

as well as in music. The theater was a form of expression especially prominent in Jesuit schools.

Jesuit priests often acted as

confessors to kings during the

early modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

. They were an important force in the Counter-Reformation and in the Catholic missions, in part because their relatively loose structure (without the requirements of living and celebration of the

Liturgy of Hours in common) allowed them to be flexible and meet diverse needs arising at the time.

Expansion of the order

After much training and experience in theology, Jesuits went across the globe in search of converts to Christianity. Despite their dedication, they had little success in Asia, except in the

Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

. For instance, early missions in Japan resulted in the government granting the Jesuits the feudal fiefdom of

Nagasaki

, officially , is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

Founded by the Portuguese, the port of Portuguese_Nagasaki, Nagasaki became the sole Nanban trade, port used for tr ...

in 1580. This was removed in 1587 due to fears over their growing influence. Jesuits did, however, have much success in Latin America. Their ascendancy in societies in the Americas accelerated during the seventeenth century, wherein Jesuits created new missions in

Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

,

Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country primarily located in South America with Insular region of Colombia, insular regions in North America. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuel ...

, and

Bolivia

Bolivia, officially the Plurinational State of Bolivia, is a landlocked country located in central South America. The country features diverse geography, including vast Amazonian plains, tropical lowlands, mountains, the Gran Chaco Province, w ...

. As early as 1603, there were 345 Jesuit priests in

Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

alone.

In 1541,

Francis Xavier

Francis Xavier, Jesuits, SJ (born Francisco de Jasso y Azpilicueta; ; ; ; ; ; 7 April 15063 December 1552), venerated as Saint Francis Xavier, was a Kingdom of Navarre, Navarrese cleric and missionary. He co-founded the Society of Jesus ...

, one of the original companions of

Loyola, arrived in

Goa,

Portuguese India

The State of India, also known as the Portuguese State of India or Portuguese India, was a state of the Portuguese Empire founded seven years after the discovery of the sea route to the Indian subcontinent by Vasco da Gama, a subject of the ...

, to carry out evangelical service in the Indies. In a 1545 letter to John III of Portugal, he requested an

Inquisition to be installed in Goa to combat heresies like crypto-Judaism and crypto-Islam. Under

Portuguese royal patronage, Jesuits thrived in Goa and until 1759 successfully expanded their activities to education and healthcare.

In 1594, they founded the first Roman-style academic institution in the East,

St. Paul Jesuit College in

Macau

Macau or Macao is a special administrative regions of China, special administrative region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). With a population of about people and a land area of , it is the most List of countries and dependencies by p ...

, China. Founded by

Alessandro Valignano, it had a great influence on the learning of Eastern languages (Chinese and Japanese) and culture by missionary Jesuits, becoming home to the first western

sinologist

Sinology, also referred to as China studies, is a subfield of area studies or East Asian studies involved in social sciences and humanities research on China. It is an academic discipline that focuses on the study of the Chinese civilizatio ...

s such as

Matteo Ricci

Matteo Ricci (; ; 6 October 1552 – 11 May 1610) was an Italian Jesuit priest and one of the founding figures of the Jesuit China missions. He created the , a 1602 map of the world written in Chinese characters. In 2022, the Apostolic See decl ...

. Jesuit efforts in Goa were interrupted by the

expulsion of the Jesuits

The suppression of the Society of Jesus was the removal of all members of the Jesuits from most of Western Europe and their respective colonies beginning in 1759 along with the abolition of the order by the Holy See in 1773; the papacy acceded ...

from Portuguese territories in 1759 by the powerful

Marquis of Pombal, the Secretary of State in Portugal.

In 1624, the Portuguese Jesuit

António de Andrade founded

a mission in Western Tibet. In 1661, two Jesuit missionaries,

Johann Grueber

Johann Grueber or Grüber (28 October 1623 30 September 1680) was an Austrian Jesuit missionary who served as an explorer of China and Tibet. He worked as an imperial astronomer in China.

Life

Grueber was born in Linz on 28 October 1623. He jo ...

and

Albert Dorville, reached

Lhasa

Lhasa, officially the Chengguan District of Lhasa City, is the inner urban district of Lhasa (city), Lhasa City, Tibet Autonomous Region, Southwestern China.

Lhasa is the second most populous urban area on the Tibetan Plateau after Xining ...

, in Tibet. The Italian Jesuit

Ippolito Desideri established a new Jesuit mission in

Lhasa

Lhasa, officially the Chengguan District of Lhasa City, is the inner urban district of Lhasa (city), Lhasa City, Tibet Autonomous Region, Southwestern China.

Lhasa is the second most populous urban area on the Tibetan Plateau after Xining ...

and

Central Tibet (1716–21) and gained an exceptional mastery of

Tibetan language and culture, writing a long and very detailed account of the country and its religion as well as treatises in Tibetan that attempted to refute key

Buddhist

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

ideas and establish the truth of Catholic Christianity.

Jesuit

missions in the Americas became controversial in Europe, especially in Spain and Portugal, where they were seen as interfering with the proper colonial enterprises of the royal governments. The Jesuits were often the only force standing between the

Indigenous and

slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

. Together throughout South America but especially in present-day

Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

and

Paraguay

Paraguay, officially the Republic of Paraguay, is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the Argentina–Paraguay border, south and southwest, Brazil to the Brazil–Paraguay border, east and northeast, and Boli ...

, they formed Indigenous Christian city-states, called "

reductions

Reductions (, also called ; ) were settlements established by Spanish rulers and Roman Catholic missionaries in Spanish America and the Spanish East Indies (the Philippines). In Portuguese-speaking Latin America, such reductions were also ...

". These were societies set up according to an idealized

theocratic

Theocracy is a form of autocracy or oligarchy in which one or more deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries, with executive and legislative power, who manage the government's daily a ...

model.

The efforts of Jesuits like

Antonio Ruiz de Montoya to protect the natives from enslavement by Spanish and Portuguese colonizers contributed to the call for the society's suppression. Jesuit priests such as

Manuel da Nóbrega and

José de Anchieta founded several towns in Brazil in the 16th century, including

São Paulo

São Paulo (; ; Portuguese for 'Paul the Apostle, Saint Paul') is the capital of the São Paulo (state), state of São Paulo, as well as the List of cities in Brazil by population, most populous city in Brazil, the List of largest cities in the ...

and

Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro, or simply Rio, is the capital of the Rio de Janeiro (state), state of Rio de Janeiro. It is the List of cities in Brazil by population, second-most-populous city in Brazil (after São Paulo) and the Largest cities in the America ...

, and were very influential in the pacification,

religious conversion

Religious conversion is the adoption of a set of beliefs identified with one particular religious denomination to the exclusion of others. Thus "religious conversion" would describe the abandoning of adherence to one denomination and affiliatin ...

, and education of indigenous nations. They built schools, organized people into villages, and created a writing system for the local languages of Brazil.

José de Anchieta and Manuel da Nóbrega were the first Jesuits that Ignacio de Loyola sent to the Americas.

Jesuit scholars working in foreign missions were very dedicated in studying the local languages and strove to produce Latinized

grammar

In linguistics, grammar is the set of rules for how a natural language is structured, as demonstrated by its speakers or writers. Grammar rules may concern the use of clauses, phrases, and words. The term may also refer to the study of such rul ...

s and

dictionaries

A dictionary is a listing of lexemes from the lexicon of one or more specific languages, often arranged Alphabetical order, alphabetically (or by Semitic root, consonantal root for Semitic languages or radical-and-stroke sorting, radical an ...

. This included: Japanese (see , also known as , "Vocabulary of the Japanese Language", a Japanese–Portuguese dictionary written 1603);

Vietnamese (Portuguese missionaries created the

Vietnamese alphabet

The Vietnamese alphabet (, ) is the modern writing script for the Vietnamese language. It uses the Latin script based on Romance languages like French language, French, originally developed by Francisco de Pina (1585–1625), a missionary from P ...

, which was later formalized by Avignon missionary

Alexandre de Rhodes with his 1651

trilingual dictionary);

Tupi, the main language of Brazil, and the pioneering study of

Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; stem form ; nominal singular , ,) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in northwest South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural ...

in the West by

Jean François Pons in the 1740s.

Jesuit missionaries were active among indigenous peoples in

New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

in North America, many of them compiling dictionaries or glossaries of the

First Nations

First nations are indigenous settlers or bands.

First Nations, first nations, or first peoples may also refer to:

Indigenous groups

*List of Indigenous peoples

*First Nations in Canada, Indigenous peoples of Canada who are neither Inuit nor Mé ...

and

Native American languages they had learned. For instance, before his death in 1708,

Jacques Gravier, vicar general of the

Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

Mission in the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

valley, compiled a

Miami–Illinois–French

dictionary

A dictionary is a listing of lexemes from the lexicon of one or more specific languages, often arranged Alphabetical order, alphabetically (or by Semitic root, consonantal root for Semitic languages or radical-and-stroke sorting, radical an ...

, considered the most extensive among works of the missionaries. Extensive documentation was left in the form of ''

The Jesuit Relations'', published annually from 1632 until 1673.

File:Bell of Nanban-ji.JPG, A shunkō-in bell made in Portugal for the Nanbanji Church, run by Jesuits in Japan, 1576–1587

Britain

Whereas Jesuits were active in

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

in the 1500s, due to the

persecution of Catholics

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics and opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy, and its adherents. Scholars have identified four categories of anti-Catholicism: constitutional-national, theological, popular and socio-cul ...

in the Elizabethan times, an English province was only established in 1623. The first pressing issue for early Jesuits in what today is the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, was to establish places for training priests. In 1579, an

English College was opened in Rome. In 1589, a

Jesuit seminary was opened at Valladolid.

In 1592, an

English College was opened in Seville. In 1614, an English college opened in Louvain. This was the earliest foundation of what was later

Heythrop College

Heythrop College, University of London, was a constituent college of the University of London between 1971 and 2018, last located in Kensington Square, London. It comprised the university's specialist faculties of philosophy and theology with soc ...

.

Campion Hall, founded in 1896, has been a presence within

Oxford University

The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the second-oldest continuously operating u ...

since then.

16th and 17th-century Jesuit institutions intended to train priests were hotbeds for the persecution of Catholics in Britain, where men suspected of being Catholic priests were routinely imprisoned, tortured, and executed. Jesuits were among those killed, including

the namesake of Campion Hall, as well as Brian Cansfield,

Ralph Corbington, and many others. A number of them were canonized among the

Forty Martyrs of England and Wales

The Forty Martyrs of England and Wales or Cuthbert Mayne and Thirty-Nine Companion Martyrs are a group of Catholic Church, Catholic, lay and religious, men and women, executed between 1535 and 1679 for treason and related offences under variou ...

.

In 2022, four Jesuit churches existed in

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, with three other places of worship in

England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

and two in

Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

.

China

The Jesuits first entered China through the

Portuguese settlement on

Macau

Macau or Macao is a special administrative regions of China, special administrative region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). With a population of about people and a land area of , it is the most List of countries and dependencies by p ...

, where they settled on

Green Island and founded

St. Paul's College.

The

Jesuit China missions

The history of the missions of the Jesuits in China is part of the history of Foreign relations of China, relations between China and the Western world. The missionary efforts and other work of the Society of Jesus, or Jesuits, between the 16th a ...

of the 16th and 17th centuries introduced Western science and astronomy, then undergoing

its own revolution, to China. The

scientific revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of History of science, modern science during the early modern period, when developments in History of mathematics#Mathematics during the Scientific Revolution, mathemati ...

brought by the Jesuits coincided with a time when scientific innovation had declined in China:

he Jesuitsmade efforts to translate western mathematical and astronomical works into Chinese and aroused the interest of Chinese scholars in these sciences. They made very extensive astronomical observation and carried out the first modern cartographic work in China. They also learned to appreciate the scientific achievements of this ancient culture and made them known in Europe. Through their correspondence, European scientists first learned about the Chinese science and culture.

For over a century, Jesuits such as

Michele Ruggieri

Michele Ruggieri, SJ (born Pompilio Ruggieri and known in China as Luo Mingjian; 1543 – 11 May 1607) was an Italian Jesuit priest and missionary. A founding father of the Jesuit China missions, co-author of the first European–Chinese dictiona ...

,

Matteo Ricci

Matteo Ricci (; ; 6 October 1552 – 11 May 1610) was an Italian Jesuit priest and one of the founding figures of the Jesuit China missions. He created the , a 1602 map of the world written in Chinese characters. In 2022, the Apostolic See decl ...

,

Diego de Pantoja,

Philippe Couplet

Philippe Couplet, SJ (1623–1693), known in China as Bai Yingli, was a Flemish people, Flemish Jesuits, Jesuit Jesuit China missions, missionary to the Qing Empire. He worked with his fellow missionaries to compile the influential ''Confucius, P ...

,

Michal Boym, and

François Noël refined translations and disseminated

Chinese knowledge,

culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

,

history

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

, and

philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

to Europe. Their

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

works popularized the name "

Confucius

Confucius (; pinyin: ; ; ), born Kong Qiu (), was a Chinese philosopher of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. Much of the shared cultural heritage of the Sinosphere originates in the phil ...

" and had considerable influence on the

Deists and other

Enlightenment thinkers, some of whom were intrigued by the Jesuits' attempts to reconcile

Confucian morality with

Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

.

Upon the arrival of the

Franciscans

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor being the largest conte ...

and other monastic orders, Jesuit accommodation of Chinese culture and rituals led to the long-running

Chinese Rites controversy. Despite the personal testimony of the

Kangxi Emperor

The Kangxi Emperor (4 May 165420 December 1722), also known by his temple name Emperor Shengzu of Qing, personal name Xuanye, was the third emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the second Qing emperor to rule over China proper. His reign of 61 ...

and many Jesuit converts that

Chinese veneration of ancestors and

Confucius

Confucius (; pinyin: ; ; ), born Kong Qiu (), was a Chinese philosopher of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. Much of the shared cultural heritage of the Sinosphere originates in the phil ...

was a nonreligious token of respect, 's

papal decree ruled that such behavior constituted impermissible forms of

idolatry

Idolatry is the worship of an idol as though it were a deity. In Abrahamic religions (namely Judaism, Samaritanism, Christianity, Islam, and the Baháʼí Faith) idolatry connotes the worship of something or someone other than the Abrahamic ...

and superstition in 1704.

His

legate Tournon and Bishop Charles Maigrot of Fujian, tasked with presenting this finding to the

Kangxi Emperor

The Kangxi Emperor (4 May 165420 December 1722), also known by his temple name Emperor Shengzu of Qing, personal name Xuanye, was the third emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the second Qing emperor to rule over China proper. His reign of 61 ...

, displayed such extreme ignorance that the emperor mandated the expulsion of Christian missionaries unable to abide by the terms of Ricci's Chinese catechism.

[.] Tournon's

summary and automatic excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to deprive, suspend, or limit membership in a religious community or to restrict certain rights within it, in particular those of being in Koinonia, communion with other members o ...

for any violators of Clement's decreeupheld by the 1715

bull

A bull is an intact (i.e., not Castration, castrated) adult male of the species ''Bos taurus'' (cattle). More muscular and aggressive than the females of the same species (i.e. cows proper), bulls have long been an important symbol cattle in r ...

led to the swift collapse of all the missions in China.

The last Jesuits were expelled after 1721.

Ireland

The first Jesuit school in

Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

was established at

Limerick

Limerick ( ; ) is a city in western Ireland, in County Limerick. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and is in the Mid-West Region, Ireland, Mid-West which comprises part of the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. W ...

by the

apostolic visitor of the

Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

,

David Wolfe. Wolfe was sent to Ireland by

Pope Pius IV

Pope Pius IV (; 31 March 1499 – 9 December 1565), born Giovanni Angelo Medici, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 December 1559 to his death, in December 1565. Born in Milan, his family considered itself a b ...

with the concurrence of the third Jesuit superior general,

Diego Laynez

Diego Laynez, S.J. (1512 – 19 January 1565; first name sometimes translated James, Jacob; surname also spelled Laines, Lainez, Laínez) was a Spanish Jesuit priest and theologian, a New Christian (of converted Jewish descent), and the second ...

. He was charged with setting up grammar schools "as a remedy against the profound ignorance of the people".

Wolfe's mission in Ireland initially concentrated on setting the sclerotic Irish Church on a sound footing, introducing the

Tridentine Reforms and finding suitable men to fill vacant sees. He established a house of religious women in Limerick known as the Menabochta ("poor women" ) and in 1565 preparations began for establishing a school at Limerick.

At his instigation,

Richard Creagh, a priest of the Diocese of Limerick, was persuaded to accept the vacant

Archdiocese of Armagh, and was consecrated in Rome in 1564.

This early Limerick school,

Crescent College, operated in difficult circumstances. In April 1566,

William Good sent a detailed report to Rome of his activities via the Portuguese Jesuits. He informed the Jesuit superior general that he and Edmund Daniel had arrived at Limerick city two years beforehand and their situation there had been perilous. Both had arrived in the city in very bad health, but had recovered due to the kindness of the people.

They established contact with Wolfe, but were only able to meet with him at night, as the English authorities were attempting to arrest the legate. Wolfe charged them initially with teaching to the boys of Limerick, with an emphasis on religious instruction, and Good translated the catechism from Latin into English for this purpose. They remained in Limerick for eight months.

In December 1565, they moved to

Kilmallock

Kilmallock () is a town in south County Limerick, Republic of Ireland, Ireland, near the border with County Cork, 30 km south of Limerick city. There is a Dominican Priory in the town and King John's Castle (Kilmallock), King's Castle (or K ...

under the protection of the Earl of Desmond, where they lived in more comfort than the primitive conditions they experienced in Limerick. They were unable to support themselves at Kilmallock and three months later they returned to Limerick in Easter 1566, and strangely set up their house in accommodation owned by the Lord Deputy of Ireland, which was conveyed to them by certain influential friends.

["Life in Tudor Limerick: William Good's 'Annual Letter' of 1566". By Thomas M. McCoog SJ & Victor Houliston. From ''Archivium Hibernicum'', 2016, Vol. 69 (2016), pp. 7–36]

They recommenced teaching at Castle Lane, and imparting the sacraments, though their activities were restricted by the arrival of Royal Commissioners. Good reported that as he was an Englishman, English officials in the city cultivated him and he was invited to dine with them on a number of occasions, though he was warned to exercise prudence and avoid promoting the

Petrine primacy

The primacy of Peter, also known as Petrine primacy (from the ), is the position of preeminence that is attributed to Saint Peter, Peter among the Twelve Apostles.

Primacy of Peter among the Apostles

The ''Evangelical Dictionary of Theology' ...

and the priority of the

Mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

amongst the

sacraments

A sacrament is a Christian rite which is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence, number and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments to be a visible symbol of ...

with his students and congregation, and that his sermons should emphasize obedience to secular princes if he wished to avoid arrest.

The number of scholars in their care was very small. An early example of a school play in Ireland is sent in one of Good's reports, which was performed on the Feast of St. John in 1566. The school was conducted in one large aula, with the students were divided into distinct classes. Good gives a highly detailed report of the curriculum taught. The top class studied the first and second parts of

Johannes Despauterius's Commentarli grammatici, and read a few letters of Cicero or the dialogues of Frusius (André des Freux, SJ). The second class committed Donatus' texts in Latin to memory and read dialogues and works by Ēvaldus Gallus. Students in the third class learned Donatus by heart, translated into English rather than Latin. Young boys in the fourth class were taught to read. Progress was slow because there were too few teachers to conduct classes simultaneously.

In the spirit of Ignatius'

Roman College

The Roman College (, ) was a school established by St. Ignatius of Loyola in 1551, just 11 years after he founded the Society of Jesus (Jesuits). It quickly grew to include classes from elementary school through university level and moved to seve ...

founded 14 years before, no fee was requested from pupils. As a result, the two Jesuits lived in very poor conditions and were very overworked with teaching and administering the sacraments to the public. In late 1568, the Castle Lane School, in the presence of Daniel and Good, was attacked and looted by government agents sent by Sir

Thomas Cusack during the pacification of Munster.

[

''Catholic Encyclopedia'' (1913), Vol. 11 Edmund O'Donnell by Charles McNeill]

The political and religious climate had become more uncertain in the lead up to

Pope Pius V

Pope Pius V, OP (; 17 January 1504 – 1 May 1572), born Antonio Ghislieri (and from 1518 called Michele Ghislieri), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 January 1566 to his death, in May 1572. He was an ...

's formal excommunication of Queen

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

, which resulted in a new wave of repression of Catholicism in England and Ireland. At the end of 1568, the Anglican Bishop of Meath,

Hugh Brady, was sent to Limerick charged with a Royal Commission to seek out and expel the Jesuits. Daniel was immediately ordered to quit the city and went to Lisbon, where he resumed his studies with the Portuguese Jesuits.

Good moved on to

Clonmel

Clonmel () is the county town and largest settlement of County Tipperary, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The town is noted in Irish history for its resistance to the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, Cromwellian army which sacked the towns of Dro ...

, before establishing himself at

Youghal

Youghal ( ; ) is a seaside resort town in County Cork, Ireland. Located on the estuary of the Munster Blackwater, River Blackwater, the town is a former military and economic centre. Located on the edge of a steep riverbank, the town has a long ...

until 1577.

In 1571, after Wolfe had been captured and imprisoned at

Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle () is a major Government of Ireland, Irish government complex, conference centre, and tourist attraction. It is located off Dame Street in central Dublin.

It is a former motte-and-bailey castle and was chosen for its position at ...

, Daniel persuaded the Portuguese Province to agree a surety for the ransom of Wolfe, who was quickly banished on release. In 1572, Daniel returned to Ireland, but was immediately captured. Incriminating documents were found on his person, which were taken as proof of his involvement with the rebellious cousin of the

Earl of Desmond

Earl of Desmond ( meaning Earl of South Munster) is a title of nobility created by the English monarch in the peerage of Ireland. The title has been created four times. It was first awarded in 1329 to Maurice FitzGerald, 1st Earl of Desmond, Maur ...

,

James Fitzmaurice and a Spanish plot. He was removed from Limerick, and taken to Cork, "just as if he were a thief or noted evildoer". After being court-martialled by the Lord President of Munster, Sir

John Perrot, he was sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered for treason, and refused pardon in return for swearing the

Act of Supremacy

The Acts of Supremacy are two acts passed by the Parliament of England in the 16th century that established the English monarchs as the head of the Church of England; two similar laws were passed by the Parliament of Ireland establishing the E ...

. His execution was carried out on 25 October 1572. A report of it was sent by Fitzmaurice to the Jesuit Superior General in 1576, where he said that Daniel was "cruelly killed because of me".

With Daniel dead and Wolfe dismissed, the Irish Jesuit foundation suffered a severe setback. Good is recorded as resident at Rome in 1577. In 1586, the seizure of Earl of Desmond's estates resulted in a new permanent Protestant plantation in Munster, making the continuation of the Limerick school impossible for a time. It was not until the early 1600s that the Jesuit mission could again re-establish itself in the city, though the Jesuits kept a low profile existence in lodgings here and there. For instance, a mission led by Fr. Nicholas Leinagh re-established itself at Limerick in 1601, though the Jesuit presence in the city numbered no more than 1 or 2 at a time in the years immediately following.

In 1604, the Lord President of Munster, Sir

Henry Brouncker - at Limerick, ordered all Jesuits from the city and Province, and offered £7 to anyone willing to betray a Jesuit priest to the authorities, and £5 for a seminarian. Jesuit houses and schools throughout the province, in the years after, were subject to periodic crackdown and the occasional destruction of schools, imprisonment of teachers and the levying of heavy money penalties on parents are recorded in publications of the time. In 1615–17, the Royal Visitation Books, written up by

Thomas Jones, the

Anglican Archbishop of Dublin, records the suppression of Jesuit schools at

Waterford

Waterford ( ) is a City status in Ireland, city in County Waterford in the South-East Region, Ireland, south-east of Ireland. It is located within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster. The city is situated at the head of Waterford H ...

, Limerick and

Galway

Galway ( ; , ) is a City status in Ireland, city in (and the county town of) County Galway. It lies on the River Corrib between Lough Corrib and Galway Bay. It is the most populous settlement in the province of Connacht, the List of settleme ...

.

In spite of this occasional persecution, the Jesuits were able to exert a degree of discreet influence within the province and in Limerick. For instance in 1606, largely through their efforts, a Catholic named Christopher Holywood was elected Mayor of the city. In 1602, the resident Jesuit had raised a sum of "200 cruzados" for the purpose of founding a hospital in Limerick, though the project was disrupted by a severe outbreak of plague and repression by the Lord President.

The principal activities of the order within Limerick at this time were devoted to preaching, administration of the sacraments and teaching. The school opened and closed intermittently in or around the area of Castle Lane, near Lahiffy's lane. During demolition work stones marked I.H.S., 1642 and 1609 were, in the 19th century, found inserted in a wall behind a tan yard near St Mary's Chapel which, according to Lenihan, were thought to mark the site of an early Jesuit school and oratory. This building, at other times, had also functioned as a dance house and candle factory.

For much of the 1600s, the Limerick Jesuit foundation established a more permanent and stable presence and the Jesuit Annals record a 'flourishing' school at Limerick in the 1640s. During the Confederacy the Jesuits had been able to go about their business unhindered and were invited to preach publicly from the pulpit of St. Mary's Cathedral on 4 occasions. Cardinal

Giovanni Rinuccini wrote to the Jesuit general in Rome, praising the work of the Rector of the Limerick College, Fr. William O'Hurley, who was aided by Fr. Thomas Burke.

A few years later, during the Protectorate era, only 18 of the Jesuits resident in Ireland managed to avoid capture by the authorities. Lenihan records that the Limerick Crescent College in 1656 moved to a hut in the middle of a bog, which was difficult for the authorities to find. This foundation was headed up by Fr. Nicholas Punch, who was aided by Frs. Maurice Patrick, Piers Creagh and James Forde. The school attracted a large number of students from around the locality.

At the Restoration of

Charles II, the school moved back to Castle Lane, and remained largely undisturbed for the next 40 years, until the surrender of the city to Williamite forces in 1692. In 1671, Dr. James Douley was appointed Vicar Apostolic of Limerick. During his visitation to the diocese, he reported to the Holy See that the Jesuits had a house and "taught schools with great fruit, instructing the youth in the articles of faith and good morals." Douley also noted that this and other Catholic schools operating in the Diocese were also attended by local Protestants.

The Jesuit presence in Ireland, in the so-called Penal era after the Battle of the Boyne, ebbed and flowed. In 1700 they were only 6 or 7, recovering to 25 in 1750. Small Jesuit houses and schools existed at Athlone, Carrick-on-Suir, Cashel, Clonmel, Kilkenny, Waterford, New Ross, Wexford, and Drogheda, as well as Dublin and Galway. At Limerick there appears to have been a long hiatus following the defeat of the Jacobite forces. Fr. Thomas O'Gorman was the first Jesuit to return to Limerick after the siege, arriving in 1728. He took up residence in Jail Lane, near the Castle in the Englishtown. There he opened a school to "impart the rudiments of the classics to the better class youth of the city."

O'Gorman left in 1737 and was succeeded by Fr. John McGrath. Next came Fr. James McMahon, who was a nephew of the Primate of Armagh,

Hugh MacMahon. McMahon lived at Limerick for thirteen years until his death in 1751. In 1746, Fr Joseph Morony was sent from Bordeaux to join McMahon and the others. Morony remained at the Jail Lane site teaching at a "high class school" until 1773, when he was ordered to close the school and oratory following the

papal suppression of the Society of Jesus, 208 years after its foundation by Wolfe. Morony then went to live in Dublin and worked as a secular priest.

Despite the efforts of the Castle authorities and English government, the Limerick school managed to survive the

Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

, the

Cromwellian invasion and

Williamite Wars, and subsequent

Penal Laws. It was forced to close, not for religious or confessional reasons, but due to the political difficulties of the Jesuit Order elsewhere.

Following the restoration of the Society of Jesus in 1814, the Jesuits gradually re-established a number of their schools throughout the country, starting with foundations at Kildare and Dublin. In 1859, they returned to Limerick at the invitation of the Bishop of Limerick,

John Ryan, and re-established a school in Galway the same year.

Canada

During the French colonisation of

New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

in the 17th century, Jesuits played an active role in North America.

Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; 13 August 1574#Fichier]For a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see #Ritch, RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December ...

established the foundations of the French colony at Québec in 1608. The native tribes that inhabited modern day Ontario, Québec, and the areas around Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay were the Montagnais, the Algonquins, and the

Wyandot people, Huron. Champlain believed that these had souls to be saved, so in 1614 he obtained the

Recollects, a reform branch of the Franciscans in France, to convert the native inhabitants.

In 1624, the French Recollects realized the magnitude of their task and sent a delegate to France to invite the Society of Jesus to help with this mission. The invitation was accepted, and Jesuits

Jean de Brébeuf

Jean de Brébeuf () (25 March 1593 16 March 1649) was a French Jesuit missionary who travelled to New France (Canada) in 1625. There he worked primarily with the Huron for the rest of his life, except for a few years in France from 1629 to 1 ...

,

Énemond Massé, and

Charles Lalemant arrived in Quebec in 1625. Lalemant is considered to have been the first author of one of the

''Jesuit Relations of New France'', which chronicled their evangelization during the 17th century.

The Jesuits became involved in the

Huron mission in 1626 and lived among the Huron peoples. Brébeuf learned the native language and created the first Huron language dictionary. Outside conflict forced the Jesuits to leave New France in 1629 when

Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

was

surrendered to the

English. In 1632, Quebec was returned to the French under the

Treaty of Saint Germain-en-Laye and the Jesuits returned to the

Huron territory. After a series of epidemics of European-introduced diseases beginning in 1634, some Huron began to mistrust the Jesuits and accused them of being sorcerers casting spells from their books.

In 1639, Jesuit

Jerome Lalemant decided that the missionaries among the Hurons needed a local residence and established

Sainte-Marie near present-day

Midland, Ontario, which was meant to be a replica of European society. It became the Jesuit headquarters and an important part of Canadian history. Throughout most of the 1640s the Jesuits had modest success, establishing five chapels in Huronia and baptising more than one thousand Huron out of a population, which may have exceeded 20,000 before the epidemics of the 1630s. However, the

Iroquois

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

of

New York, rivals of the Hurons, grew jealous of the Hurons' wealth and control of the fur trade system and attacked Huron villages in 1648. They killed missionaries and burned villages, and the Hurons scattered. Both de Brébeuf and Gabriel Lalemant were tortured and killed in the Iroquois raids. For this, they have been canonized as martyrs in the Catholic Church.

The Jesuit

Paul Ragueneau

Paul Ragueneau, SJ (; 18 March 1608 – 3 September 1680) was a Jesuit missionary in New France.

Biography

He was born in Paris and died in the same city. He is sometimes confused with his elder brother François, also a Jesuit. Father Franço ...

burned down

Sainte-Marie, instead of allowing the Iroquois the satisfaction of destroying it. By late June 1649, the French and some Christian Hurons built Sainte-Marie II on