Jerome Salinger on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jerome David Salinger ( ; January 1, 1919 – January 27, 2010) was an American author best known for his 1951 novel ''

Jerome David Salinger was born in

Jerome David Salinger was born in

"Raise High the Bookshelves, Censors!"

(book review),

Salinger published ''

Salinger published ''

Salinger died from natural causes at his home in

Salinger died from natural causes at his home in

, Authorsontheweb.com. Retrieved July 10, 2007. Both Hiaasen and Minot cite him as an influence here.

The Reclusive Writer Inspired a Generation

''Baltimore Sun'', January 29, 2010

nbsp;– ''Daily Telegraph'' obituary

Obituary: JD Salinger

BBC News, January 28, 2010

World Socialist Web Site. February 2, 2010.

Implied meanings in J. D. Salinger stories and reverting

Catching Salinger

nbsp;– Serialized documentary about the search for J.D. Salinger

J.D. Salinger

biography, quotes, multimedia, teacher resources

On J.D. Salinger

by Michael Greenberg from ''

Essay on Salinger's life from Haaretz

*

J.D. Salinger – Hartog Letters, University of East Anglia

Salinger and 'Catcher in the Rye'

— slideshow by ''

The Man in the Glass House

— Ron Rosenbaum's 1997 profile for ''

The Catcher in the Rye

''The Catcher in the Rye'' is the only novel by American author J. D. Salinger. It was partially published in serial form in 1945–46 before being novelized in 1951. Originally intended for adults, it is often read by adolescents for its theme ...

''. Salinger published several short stories in ''Story

Story or stories may refer to:

Common uses

* Narrative, an account of imaginary or real people and events

** Short story, a piece of prose fiction that typically can be read in one sitting

** News story, an event or topic reported by a news orga ...

'' magazine in 1940, before serving in World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. In 1948, his critically acclaimed story "A Perfect Day for Bananafish

"A Perfect Day for Bananafish" is a short story by J. D. Salinger, originally published in the January 31, 1948, issue of ''The New Yorker''. It was anthologized in 1949's ''55 Short Stories from The New Yorker'', as well as in Salinger's 1953 col ...

" appeared in ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. It was founded on February 21, 1925, by Harold Ross and his wife Jane Grant, a reporter for ''The New York T ...

'', which published much of his later work.

''The Catcher in the Rye'' (1951) was an immediate popular success; Salinger's depiction of adolescent alienation and loss of innocence

Innocence is a lack of guilt, with respect to any kind of crime, or wrongdoing. In a legal context, innocence is prior to the sense of legal guilt and is a primal emotion connected with the sense of self. It is often confused as being the opp ...

was influential, especially among adolescent readers. The novel was widely read and controversial, and its success led to public attention and scrutiny. Salinger became reclusive

A recluse is a person who lives in voluntary seclusion and solitude. The word is from the Latin , which means 'to open' or 'disclose'.

Examples of recluses are Symeon of Trier, who lived within the great Roman gate Porta Nigra with permission ...

, publishing less frequently. He followed ''Catcher'' with a short story collection, '' Nine Stories'' (1953); ''Franny and Zooey

''Franny ''and'' Zooey'' is a book by American author J. D. Salinger which comprises his short story "Franny" and novella ''Zooey'' . The two works were published together as a book in 1961, having originally appeared in ''The New Yorker'' in 195 ...

'' (1961), a volume containing a novella and a short story; and a volume containing two novellas, '' Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction'' (1963). Salinger's last published work, the novella '' Hapworth 16, 1924'', appeared in ''The New Yorker'' on June 19, 1965.

Afterward, Salinger struggled with unwanted attention, including a legal battle in the 1980s with biographer Ian Hamilton and the release in the late 1990s of memoirs written by two people close to him: Joyce Maynard

Joyce Maynard (born November 5, 1953) is an American novelist and journalist. She began her career in journalism in the 1970s, writing for several publications, most notably '' Seventeen'' magazine and ''The New York Times''. Maynard contributed ...

, an ex-lover; and his daughter, Margaret Salinger.

Early life

Jerome David Salinger was born in

Jerome David Salinger was born in Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

, New York City, on January 1, 1919. His father, Sol Salinger, traded in Kosher

(also or , ) is a set of dietary laws dealing with the foods that Jewish people are permitted to eat and how those foods must be prepared according to Jewish law. Food that may be consumed is deemed kosher ( in English, ), from the Ashke ...

cheese, and was from a family of Lithuanian-Jewish

{{Infobox ethnic group

, group = Litvaks

, image =

, caption =

, poptime =

, region1 = {{flag, Lithuania

, pop1 = 2,800

, region2 =

{{flag, South Africa

, pop2 = 6 ...

descent from Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

. Sol's father was the rabbi for Adath Jeshurun Congregation

Adath Jeshurun Congregation (also Adath Jeshurun Synagogue) is a Conservative synagogue located in Minnetonka, Minnesota, in the United States, with about 1,200 members. Founded in 1884, it is a founding member of the United Synagogue of Ameri ...

in Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the List of cities in Kentucky, most populous city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, sixth-most populous city in the Southeastern United States, Southeast, and the list of United States cities by population, 27th-most-populous city ...

.

Salinger's mother, Marie (née Jillich), was born in Atlantic, Iowa

Atlantic is a city in and the county seat of Cass County, Iowa, United States, located along the East Nishnabotna River. The population was 6,792 in the 2020 census, a decline from the 7,257 population in 2000.

History

Atlantic was founded ...

, of German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

, Irish, and Scottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

descent,"J. D. Salinger". LitFinder Contemporary Collection. Gale, 2007. Web. November 9, 2010. "but changed her first name to Miriam to appease her in-laws" and considered herself Jewish after marrying Salinger's father. Salinger did not learn that his mother was not of Jewish ancestry until just after he celebrated his Bar Mitzvah

A ''bar mitzvah'' () or ''bat mitzvah'' () is a coming of age ritual in Judaism. According to Halakha, Jewish law, before children reach a certain age, the parents are responsible for their child's actions. Once Jewish children reach that age ...

. He had one sibling, an older sister, Doris (1912–2001).

In his youth, Salinger attended public schools on the West Side

West Side or Westside may refer to:

Places Canada

* West Side, a neighbourhood of Windsor, Ontario

* West Side, a neighbourhood of Vancouver, British Columbia

United Kingdom

* West Side, Lewis, Outer Hebrides, Scotland

* Westside, Birmingham ...

of Manhattan. In 1932, the family moved to Park Avenue

Park Avenue is a boulevard in New York City that carries north and southbound traffic in the borough (New York City), boroughs of Manhattan and the Bronx. For most of the road's length in Manhattan, it runs parallel to Madison Avenue to the wes ...

, and Salinger enrolled at the McBurney School

McBurney School was a boys (later co-educational) college-preparatory school in Manhattan run by the YMCA of Greater New York. Its name commemorates Robert Ross McBurney, a prominent New York YMCA leader during the late 19th century.

History ...

, a nearby private school. Salinger had trouble fitting in and took measures to conform, such as calling himself Jerry. His family called him Sonny.Hathcock, Barrett. "J.D. Salinger" At McBurney, he managed the fencing team, wrote for the school newspaper and appeared in plays. He "showed an innate talent for drama," though his father opposed the idea of his becoming an actor. His parents then enrolled him at Valley Forge Military Academy

Valley Forge Military Academy and College (VFMAC) is a private boarding school (grades 7–12) and military junior college in Wayne, Pennsylvania. It follows in the traditional Military academy, military school format with army traditions.

T ...

in Wayne, Pennsylvania

Wayne is an unincorporated community centered in Delaware County, Pennsylvania, United States, on the Main Line, a series of highly affluent Philadelphia suburbs located along the railroad tracks of the Pennsylvania Railroad and one of the ...

. Salinger began writing stories "under the covers t night

T, or t, is the twentieth letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''tee'' (pronounced ), plural ''tees''.

It is d ...

with the aid of a flashlight". He was the literary editor of the class yearbook, ''Crossed Sabres'', and participated in the glee club, aviation club, French club, and the Non-Commissioned Officers

A non-commissioned officer (NCO) is an enlisted rank, enlisted leader, petty officer, or in some cases warrant officer, who does not hold a Commission (document), commission. Non-commissioned officers usually earn their position of authority b ...

Club.

Salinger's Valley Forge 201 file

The Official Military Personnel File (OMPF), known as a 201 File in the U.S. Army, is an Armed Forces administrative record containing information about a service member's history, such as:

* Promotion Orders

* Mobilization Orders

DA1059s ...

says he was a "mediocre" student, and his recorded IQ between 111 and 115 was slightly above average. He graduated in 1936. Salinger started his freshman year at New York University

New York University (NYU) is a private university, private research university in New York City, New York, United States. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded in 1832 by Albert Gallatin as a Nondenominational ...

in 1936. He considered studying special education

Special education (also known as special-needs education, aided education, alternative provision, exceptional student education, special ed., SDC, and SPED) is the practice of educating students in a way that accommodates their individual di ...

but dropped out the following year. His father urged him to learn about the meat-importing business, and he went to work at a company in Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

and Bydgoszcz

Bydgoszcz is a city in northern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Kuyavia. Straddling the confluence of the Vistula River and its bank (geography), left-bank tributary, the Brda (river), Brda, the strategic location of Byd ...

, Poland. Salinger was disgusted by the slaughterhouses and decided to pursue a different career. This disgust and his rejection of his father likely influenced his vegetarianism as an adult.

In late 1938, Salinger attended Ursinus College

Ursinus College is a private liberal arts college in Collegeville, Pennsylvania. It was founded in 1869 and occupies a campus. Ursinus College's forerunner was the Freeland Seminary founded in 1848. Its $127 million endowment supports about 1, ...

in Collegeville, Pennsylvania

Collegeville is a borough in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, a suburb outside of Philadelphia on Perkiomen Creek. Collegeville was incorporated in 1896. It is the location of Ursinus College, which opened in 1869. The population was 5,089 ...

, and wrote a column called "skipped diploma", which included movie reviews. He dropped out after one semester. In 1939, Salinger attended the Columbia University School of General Studies

The School of General Studies (GS) is a liberal arts college and one of the undergraduate colleges of Columbia University, situated on the university's main campus in Morningside Heights, Borough (New York City), New York City. GS is known prima ...

in Manhattan, where he took a writing class taught by Whit Burnett

Whit Burnett (August 14, 1899 – April 22, 1973) was an American writer and educator who founded and edited the literary magazine ''Story (magazine), Story''. In the 1940s, ''Story'' was an important magazine in that it published the first or earl ...

, longtime editor of ''Story

Story or stories may refer to:

Common uses

* Narrative, an account of imaginary or real people and events

** Short story, a piece of prose fiction that typically can be read in one sitting

** News story, an event or topic reported by a news orga ...

'' magazine. According to Burnett, Salinger did not distinguish himself until a few weeks before the end of the second semester, at which point "he suddenly came to life" and completed three stories. Burnett told Salinger that his stories were skillful and accomplished, accepting "The Young Folks," a vignette

Vignette may refer to:

* Vignette (entertainment), a sketch in a sketch comedy

* Vignette (graphic design), decorative designs in books (originally in the form of leaves and vines) to separate sections or chapters

* Vignette (literature), short, i ...

about several aimless youths, for publication in ''Story''. Salinger's debut short story was published in the magazine's March–April 1940 issue. Burnett became Salinger's mentor, and they corresponded for several years.

World War II

In 1942, Salinger started datingOona O'Neill

Oona O'Neill, Lady Chaplin (14 May 1925 – 27 September 1991) was a British actress, the daughter of American playwright Eugene O'Neill and English-born writer Agnes Boulton, and the fourth and last wife of actor and filmmaker Charlie Chaplin.

...

, daughter of the playwright Eugene O'Neill

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953) was an American playwright. His poetically titled plays were among the first to introduce into the U.S. the drama techniques of Realism (theatre), realism, earlier associated with ...

. Despite finding her self-absorbed (he confided to a friend that "Little Oona's hopelessly in love with little Oona"), he called her often and wrote her long letters. Their relationship ended when Oona began seeing Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is considered o ...

, whom she eventually married. In late 1941, Salinger briefly worked on a Caribbean

The Caribbean ( , ; ; ; ) is a region in the middle of the Americas centered around the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, mostly overlapping with the West Indies. Bordered by North America to the north, Central America ...

cruise ship

Cruise ships are large passenger ships used mainly for vacationing. Unlike ocean liners, which are used for transport, cruise ships typically embark on round-trip voyages to various ports of call, where passengers may go on Tourism, tours k ...

, serving as an activity director and possibly a performer.

The same year, Salinger began submitting short stories to ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. It was founded on February 21, 1925, by Harold Ross and his wife Jane Grant, a reporter for ''The New York T ...

''. The magazine rejected seven of his stories that year, including "Lunch for Three," "Monologue for a Watery Highball," and "I Went to School with Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

." But in December 1941, it accepted "Slight Rebellion off Madison

"Slight Rebellion off Madison" is an uncollected work of short fiction by J. D. Salinger which appeared in the 21 December 1946 issue of The New Yorker.

The story is the first of nine stories to feature Salinger's iconic protagonist Holden Mo ...

," a Manhattan-set story about a disaffected teenager named Holden Caulfield

Holden Caulfield (identified as "Holden Morrisey Caulfield" in the story "Slight Rebellion Off Madison", and "Holden V. Caulfield" in ''The Catcher in the Rye'') is a fictional character in the works of author J. D. Salinger. He is most famous f ...

with "pre-war jitters". When Japan carried out the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

that month, the story was rendered "unpublishable." Salinger was devastated. The story appeared in ''The New Yorker'' in 1946, after the war ended.

In early 1942, several months after the U.S. entered World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Salinger was drafted into the army, where he saw combat with the 12th Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division. He was present at Utah Beach on D-Day

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during the Second World War. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

, in the Battle of the Bulge

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Offensive or Unternehmen Die Wacht am Rhein, Wacht am Rhein, was the last major German Offensive (military), offensive Military campaign, campaign on the Western Front (World War II), Western ...

, and the Battle of Hürtgen Forest

The Battle of Hürtgen Forest () was a series of battles fought from 19 September to 16 December 1944, between United States Armed Forces, American and Wehrmacht, German forces on the Western Front (World War II), Western Front during World War ...

.

During the campaign from Normandy into Germany, Salinger arranged to meet Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway ( ; July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer and journalist. Known for an economical, understated style that influenced later 20th-century writers, he has been romanticized fo ...

, a writer who had influenced him and was then working as a war correspondent in Paris. Salinger was impressed with Hemingway's friendliness and modesty, finding him more "soft" than his gruff public persona. Hemingway was impressed by Salinger's writing and remarked: "Jesus, he has a helluva talent." The two began corresponding; Salinger wrote to Hemingway in July 1946 that their talks were among his few positive memories of the war, and added that he was working on a play about Caulfield and hoped to play the part himself.

Salinger was assigned to a counter-intelligence

Counterintelligence (counter-intelligence) or counterespionage (counter-espionage) is any activity aimed at protecting an agency's intelligence program from an opposition's intelligence service. It includes gathering information and conducting ac ...

unit also known as the Ritchie Boys

The Ritchie Boys, part of the U.S. Military Intelligence Service (MIS) at the War Department, were an organization of soldiers in World War II with sizable numbers of German and Austrian recruits who were used primarily for interrogation of pri ...

, in which he used his proficiency in French and German to interrogate prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

. In April 1945 he entered Kaufering IV concentration camp, a subcamp of Dachau

Dachau (, ; , ; ) was one of the first concentration camps built by Nazi Germany and the longest-running one, opening on 22 March 1933. The camp was initially intended to intern Hitler's political opponents, which consisted of communists, s ...

. Salinger earned the rank of Staff Sergeant and served in five campaigns. His war experiences affected him emotionally. He was hospitalized for a few weeks for combat stress reaction

Combat stress reaction (CSR) is acute behavioral disorganization as a direct result of the trauma of war. Also known as "combat fatigue", "battle fatigue", "operational exhaustion", or "battle/war neurosis", it has some overlap with the diagnosis ...

after Germany was defeated, and later told his daughter: "You never really get the smell of burning flesh out of your nose entirely, no matter how long you live." Salinger's biographers speculate that he drew upon his wartime experiences in several stories, such as "For Esmé—with Love and Squalor

"For Esmé—with Love and Squalor" is a short story by J. D. Salinger. It recounts an American sergeant's meeting with a young girl before being sent into combat in World War II. Originally published in ''The New Yorker'' on April 8, 1950, it was ...

", which is narrated by a traumatized soldier. Salinger continued to write while serving in the army, publishing several stories in slick magazines such as ''Collier's

}

''Collier's'' was an American general interest magazine founded in 1888 by Peter F. Collier, Peter Fenelon Collier. It was launched as ''Collier's Once a Week'', then renamed in 1895 as ''Collier's Weekly: An Illustrated Journal'', shortened i ...

'' and ''The Saturday Evening Post

''The Saturday Evening Post'' is an American magazine published six times a year. It was published weekly from 1897 until 1963, and then every other week until 1969. From the 1920s to the 1960s, it was one of the most widely circulated and influ ...

''. He also continued to submit stories to ''The New Yorker'', but with little success; it rejected all of his submissions from 1944 to 1946, including a group of 15 poems in 1945.

Postwar years

After Germany's defeat, Salinger signed up for a six-month period of "Denazification

Denazification () was an Allied initiative to rid German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary, and politics of the Nazi ideology following the Second World War. It was carried out by removing those who had been Nazi Par ...

" duty in Germany for the Counterintelligence Corps

The Counter Intelligence Corps (Army CIC) was a World War II and early Cold War intelligence agency within the United States Army consisting of highly trained special agents. Its role was taken over by the U.S. Army Intelligence Corps in 1961 and ...

. He lived in Weißenburg and, soon after, married Sylvia Welter. He brought her to the United States in April 1946, but the marriage fell apart after eight months and Sylvia returned to Germany. In 1972, Salinger's daughter Margaret was with him when he received a letter from Sylvia. He looked at the envelope, and, without reading it, tore it apart. It was the first time he had heard from her since the breakup, but as Margaret put it, "when he was finished with a person, he was through with them."

In 1946, Whit Burnett

Whit Burnett (August 14, 1899 – April 22, 1973) was an American writer and educator who founded and edited the literary magazine ''Story (magazine), Story''. In the 1940s, ''Story'' was an important magazine in that it published the first or earl ...

agreed to help Salinger publish a collection of his short stories through ''Story'' Press's Lippincott Imprint. The collection, ''The Young Folks'', was to consist of 20 stories—ten, like the title story and "Slight Rebellion off Madison", already in print and ten previously unpublished. Though Burnett implied the book would be published and even negotiated Salinger a $1,000 advance, Lippincott overruled Burnett and rejected the book. Salinger blamed Burnett for the book's failure to see print, and the two became estranged.

By the late 1940s, Salinger had become an avid follower of Zen Buddhism

Zen (; from Chinese: '' Chán''; in Korean: ''Sŏn'', and Vietnamese: ''Thiền'') is a Mahayana Buddhist tradition that developed in China during the Tang dynasty by blending Indian Mahayana Buddhism, particularly Yogacara and Madhyamaka ph ...

, to the point that he "gave reading lists on the subject to his dates".

In 1947, Salinger submitted a short story, "The Bananafish", to ''The New Yorker''. William Maxwell, the magazine's fiction editor, was impressed enough with "the singular quality of the story" that the magazine asked Salinger to continue revising it. He spent a year reworking it with ''New Yorker'' editors and the magazine published it, now titled "A Perfect Day for Bananafish

"A Perfect Day for Bananafish" is a short story by J. D. Salinger, originally published in the January 31, 1948, issue of ''The New Yorker''. It was anthologized in 1949's ''55 Short Stories from The New Yorker'', as well as in Salinger's 1953 col ...

", in the January 31, 1948, issue. The magazine thereon offered Salinger a "first-look" contract that allowed it right of first refusal

Right of first refusal (ROFR or RFR) is a contractual right that gives its holder the option to enter a business transaction with the owner of something, according to specified terms, before the owner is entitled to enter into that transactio ...

on any future stories. The critical acclaim accorded "Bananafish" coupled with problems Salinger had with stories being altered by the "slicks" led him to publish almost exclusively in ''The New Yorker''. "Bananafish" was also the first of Salinger's published stories to feature the Glasses

Glasses, also known as eyeglasses (American English), spectacles (Commonwealth English), or colloquially as specs, are vision eyewear with clear or tinted lenses mounted in a frame that holds them in front of a person's eyes, typically u ...

, a fictional family consisting of two retired vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment which began in France in the middle of the 19th century. A ''vaudeville'' was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a drama ...

performers and their seven precocious children: Seymour, Buddy, Boo Boo, Walt, Waker, Zooey, and Franny. Salinger published seven stories about the Glasses, developing a detailed family history and focusing particularly on Seymour, the brilliant but troubled eldest child.

In the early 1940s, Salinger confided in a letter to Burnett that he was eager to sell the film rights to some of his stories to achieve financial security. According to Ian Hamilton, Salinger was disappointed when "rumblings from Hollywood" over his 1943 short story " The Varioni Brothers" came to nothing. Therefore, he immediately agreed when, in mid-1948, independent film producer Samuel Goldwyn

Samuel Goldwyn (; born Szmuel Gelbfisz; ; July 1879 (most likely; claimed to be August 27, 1882) January 31, 1974), also known as Samuel Goldfish, was a Polish-born American film producer and pioneer in the American film industry, who produce ...

offered to buy the film rights to his short story "Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut

"Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut" is a short story by J. D. Salinger that appears in his collection '' Nine Stories''. It was originally published in the March 20, 1948 issue of ''The New Yorker''.

The main character, Eloise, struggles to come to te ...

." Though Salinger sold the story with the hope—in the words of his agent Dorothy Olding—that it "would make a good movie", critics lambasted the film upon its release in 1949. Berg, A. Scott. ''Goldwyn: A Biography.'' New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989. . p. 446. Renamed '' My Foolish Heart'' and starring Dana Andrews

Carver Dana Andrews (January 1, 1909 – December 17, 1992) was an American film actor who became a major star in what is now known as film noir and later in Western films. A leading man during the 1940s, he continued acting in less prestigio ...

and Susan Hayward

Susan Hayward (born Edythe Marrener; June 30, 1917 – March 14, 1975) was an American actress best known for her film portrayals of women that were based on true stories.

After working as a fashion model for the Walter Clarence Thornton, Walt ...

, the film departed to such an extent from Salinger's story that Goldwyn biographer A. Scott Berg

Andrew Scott Berg (born December 4, 1949) is an American biographer. After graduating from Princeton University in 1971, Berg expanded his senior thesis on editor Maxwell Perkins into a full-length biography, ''Max Perkins: Editor of Genius'' ...

called it a " bastardization." As a result of this experience, Salinger never again permitted film adaptations

A film adaptation transfers the details or story of an existing source text, such as a novel, into a feature film. This transfer can involve adapting most details of the source text closely, including characters or plot points, or the original sou ...

of his work. When Brigitte Bardot

Brigitte Anne-Marie Bardot ( ; ; born 28 September 1934), often referred to by her initials B.B., is a French former actress, singer, and model as well as an animal rights activist. Famous for portraying characters with Hedonism, hedonistic life ...

wanted to buy the rights to "A Perfect Day for Bananafish

"A Perfect Day for Bananafish" is a short story by J. D. Salinger, originally published in the January 31, 1948, issue of ''The New Yorker''. It was anthologized in 1949's ''55 Short Stories from The New Yorker'', as well as in Salinger's 1953 col ...

", Salinger refused, but told his friend Lillian Ross, longtime staff writer for ''The New Yorker'', "She's a cute, talented, lost ''enfante'', and I'm tempted to accommodate her, ''pour le sport''."

''The Catcher in the Rye''

In the 1940s, Salinger told several people that he was working on a novel featuring Holden Caulfield, the teenage protagonist of his short story "Slight Rebellion off Madison", andLittle, Brown and Company

Little, Brown and Company is an American publishing company founded in 1837 by Charles Coffin Little and James Brown in Boston. For close to two centuries, it has published fiction and nonfiction by American authors. Early lists featured Emil ...

published ''The Catcher in the Rye

''The Catcher in the Rye'' is the only novel by American author J. D. Salinger. It was partially published in serial form in 1945–46 before being novelized in 1951. Originally intended for adults, it is often read by adolescents for its theme ...

'' on July 16, 1951. The novel's plot is straightforward, detailing 16-year-old Holden's experiences in New York City after his fourth expulsion and departure from an elite college preparatory school

A college-preparatory school (often shortened to prep school, preparatory school, college prep school or college prep academy) is a type of secondary school. The term refers to public, private independent or parochial schools primarily design ...

. The book is more notable for the persona and testimonial voice of its first-person narrator

A first-person narrative (also known as a first-person perspective, voice, point of view, etc.) is a mode of storytelling in which a storyteller recounts events from that storyteller's own personal point of view, using first-person grammar suc ...

, Holden.Nandel, Alan. "The Significance of Holden Caulfield's Testimony." Reprinted in Bloom, Harold, ed. ''Modern Critical Interpretations: J. D. Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye.'' Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 2000. pp. 75–89. He serves as an insightful but unreliable narrator

In literature, film, and other such arts, an unreliable narrator is a narrator who cannot be trusted, one whose credibility is compromised. They can be found in a wide range from children to mature characters. While unreliable narrators are al ...

who expounds on the importance of loyalty, the "phoniness" of adulthood, and his own duplicity. In a 1953 interview with a high school newspaper, Salinger admitted that the novel was "sort of" autobiographical, explaining, "My boyhood was very much the same as that of the boy in the book, and it was a great relief telling people about it."

Initial reactions to the book were mixed, ranging from ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' hailing ''Catcher'' as "an unusually brilliant first novel" to denigrations of the book's monotonous language and Holden's "immorality and perversion"Whitfield, Stephen J"Raise High the Bookshelves, Censors!"

(book review),

The Virginia Quarterly Review

The ''Virginia Quarterly Review'' is a quarterly literary magazine that was established in 1925 by James Southall Wilson, at the request of University of Virginia president E. A. Alderman. This ''"National Journal of Literature and Discussio ...

, Spring 2002. Retrieved November 27, 2007. In a review of the book in ''The Christian Science Monitor

''The Christian Science Monitor'' (''CSM''), commonly known as ''The Monitor'', is a nonprofit news organization that publishes daily articles both in Electronic publishing, electronic format and a weekly print edition. It was founded in 1908 ...

,'' the reviewer found the book unfit "for children to read," writing that they would be influenced by Holden, "as too easily happens when immorality and perversion are recounted by writers of talent whose work is countenanced in the name of art or good intention." (he uses religious slurs and freely discusses casual sex and prostitution). The novel was a popular success; within two months of its publication, it had been reprinted eight times. It spent 30 weeks on the ''New York Times'' Bestseller list. The book's initial success was followed by a brief lull in popularity, but by the late 1950s, according to Salinger's biographer Ian Hamilton, it had "become the book all brooding adolescents had to buy, the indispensable manual from which cool styles of disaffectation could be borrowed." It has been compared with Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, and essayist. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced," with William Fau ...

's ''The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

''Adventures of Huckleberry Finn'' is a picaresque novel by American author Mark Twain that was first published in the United Kingdom in December 1884 and in the United States in February 1885.

Commonly named among the Great American Novels, th ...

.'' Newspapers began publishing articles about the "Catcher Cult", and the novel was banned in several countries—as well as some U.S. schools—because of its subject matter and what ''Catholic World

''The Catholic World'' was an American periodical founded by Paulist Father Isaac Thomas Hecker in April 1865. It was published by the Paulist Fathers for over a century. According to Paulist Press, Hecker "wanted to create an intellectual jo ...

'' reviewer Riley Hughes called an "excessive use of amateur swearing and coarse language". According to one angry parent's tabulation, 237 instances of "goddamn", 58 uses of "bastard", 31 "Chrissakes", and one incident of flatulence

Flatulence is the expulsion of gas from the Gastrointestinal tract, intestines via the anus, commonly referred to as farting. "Flatus" is the medical word for gas generated in the stomach or bowels. A proportion of intestinal gas may be swal ...

constituted what was wrong with Salinger's book.

In the 1970s, several U.S. high school teachers who assigned the book were fired or forced to resign. A 1979 study of censorship noted that ''The Catcher in the Rye'' "had the dubious distinction of being at once the most frequently censored book across the nation and the second-most frequently taught novel in public high schools" (after John Steinbeck

John Ernst Steinbeck ( ; February 27, 1902 – December 20, 1968) was an American writer. He won the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature "for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humor and keen social percep ...

's ''Of Mice and Men

''Of Mice and Men'' is a 1937 novella written by American author John Steinbeck. It describes the experiences of George Milton and Lennie Small, two displaced migrant worker, migrant ranch workers, as they move from place to place in California ...

''). The book remains widely read; as of 2004, it was selling about 250,000 copies per year, "with total worldwide sales over 10 million copies".

Mark David Chapman

Mark David Chapman (born May 10, 1955) is an American man who murdered English musician John Lennon in New York City on December 8, 1980. As Lennon walked into the archway of The Dakota, his apartment building on the Upper West Side, Chapman ...

, who shot singer-songwriter John Lennon

John Winston Ono Lennon (born John Winston Lennon; 9 October 19408 December 1980) was an English singer-songwriter, musician and activist. He gained global fame as the founder, co-lead vocalist and rhythm guitarist of the Beatles. Lennon's ...

in December 1980, was obsessed with the book.

In the wake of its 1950s success, Salinger received (and rejected) numerous offers to adapt ''The Catcher in the Rye'' for the screen, including one from Samuel Goldwyn

Samuel Goldwyn (; born Szmuel Gelbfisz; ; July 1879 (most likely; claimed to be August 27, 1882) January 31, 1974), also known as Samuel Goldfish, was a Polish-born American film producer and pioneer in the American film industry, who produce ...

. Since its publication, there has been sustained interest in the novel among filmmakers, with Billy Wilder

Billy Wilder (; ; born Samuel Wilder; June 22, 1906 – March 27, 2002) was an American filmmaker and screenwriter. His career in Hollywood (film industry), Hollywood spanned five decades, and he is regarded as one of the most brilliant and ver ...

, Harvey Weinstein

Harvey Weinstein (, ; born March 19, 1952) is an American film producer and convicted sex offender. In 1979, Weinstein and his brother, Bob Weinstein, co-founded the entertainment company Miramax, which produced several successful independent ...

, and Steven Spielberg

Steven Allan Spielberg ( ; born December 18, 1946) is an American filmmaker. A major figure of the New Hollywood era and pioneer of the modern blockbuster, Spielberg is widely regarded as one of the greatest film directors of all time and is ...

among those seeking to secure the rights. In the 1970s Salinger said, "Jerry Lewis

Jerry Lewis (born Joseph Levitch; March 16, 1926 – August 20, 2017) was an American comedian, actor, singer, filmmaker and humanitarian, with a career spanning seven decades in film, stage, television and radio. Famously nicknamed as "Th ...

tried for years to get his hands on the part of Holden." Salinger repeatedly refused, and in 1999 his ex-lover Joyce Maynard

Joyce Maynard (born November 5, 1953) is an American novelist and journalist. She began her career in journalism in the 1970s, writing for several publications, most notably '' Seventeen'' magazine and ''The New York Times''. Maynard contributed ...

concluded, "The only person who might ever have played Holden Caulfield would have been J. D. Salinger."

Writing in the 1950s and move to Cornish

In a July 1951 profile in ''Book of the Month Club News,'' Salinger's friend and ''New Yorker'' editor William Maxwell asked Salinger about his literary influences. He replied, "A writer, when he's asked to discuss his craft, ought to get up and call out in a loud voice just the names of the writers he loves. I loveKafka

Franz Kafka (3 July 1883 – 3 June 1924) was a novelist and writer from Prague who was Jewish, Austrian, and Czech and wrote in German. He is widely regarded as a major figure of 20th-century literature. His work fuses elements of real ...

, Flaubert

Gustave Flaubert ( , ; ; 12 December 1821 – 8 May 1880) was a French novelist. He has been considered the leading exponent of literary realism in his country and abroad. According to the literary theorist Kornelije Kvas, "in Flaubert, realis ...

, Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using pre-reform Russian orthography. ; ), usually referr ...

, Chekhov

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (; ; 29 January 1860 – 15 July 1904) was a Russian playwright and short-story writer, widely considered to be one of the greatest writers of all time. His career as a playwright produced four classics, and his b ...

, Dostoevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in both Russian and world literature, and many of his works are considered highly influenti ...

, Proust

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust ( ; ; 10 July 1871 – 18 November 1922) was a French novelist, literary critic, and essayist who wrote the novel (in French language, French – translated in English as ''Remembrance of Things Pas ...

, O'Casey

O'Casey is a common variation of the Gaelic ''cathasaigh'', meaning ''vigilant'' or ''watchful'', with the added anglicized prefix '' O of the Gaelic ''Ó'', meaning ''grandson'' or ''descendant''. At least six different septs used this name, ...

, Rilke

René Karl Wilhelm Johann Josef Maria Rilke (4 December 1875 – 29 December 1926), known as Rainer Maria Rilke, was an Austrian poet and novelist. Acclaimed as an idiosyncratic and expressive poet, he is widely recognized as a significant ...

, Lorca, Keats

John Keats (31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English poet of the second generation of Romantic poets, along with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. His poems had been in publication for less than four years when he died of tub ...

, Rimbaud

Jean Nicolas Arthur Rimbaud (, ; ; 20 October 1854 – 10 November 1891) was a French poet known for his transgressive and surreal themes and for his influence on modern literature and arts, prefiguring surrealism.

Born in Charleville, he s ...

, Burns

Burns may refer to:

Astronomy

* 2708 Burns, an asteroid

* Burns (crater), on Mercury

People

* Burns (surname), list of people and characters named Burns

** Burns (musician), Scottish record producer

Places in the United States

* Burns, ...

, E. Brontë, Jane Austen

Jane Austen ( ; 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist known primarily for #List of works, her six novels, which implicitly interpret, critique, and comment on the English landed gentry at the end of the 18th century ...

, Henry James

Henry James ( – ) was an American-British author. He is regarded as a key transitional figure between literary realism and literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest novelists in the English language. He was the ...

, Blake

Blake or Blake's may refer to:

People

* Blake (given name), a given name of English origin (includes a list of people with the name)

* Blake (surname), a surname of English origin (includes a list of people with the name)

** William Blake (1757 ...

, Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge ( ; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poets with his friend William Wordsworth ...

. I won't name any living writers. I don't think it's right" (although O'Casey was in fact alive at the time). In letters from the 1940s, Salinger expressed his admiration of three living, or recently deceased, writers: Sherwood Anderson

Sherwood Anderson (September 13, 1876 – March 8, 1941) was an American novelist and short story writer, known for subjective and self-revealing works. Self-educated, he rose to become a successful copywriter and business owner in Cleveland and ...

, Ring Lardner

Ringgold Wilmer Lardner (March 6, 1885 – September 25, 1933) was an American sports columnist and short story writer best known for his satirical writings on sports, marriage, and the theatre. His contemporaries—Ernest Hemingway, Virginia W ...

, and F. Scott Fitzgerald

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940), widely known simply as Scott Fitzgerald, was an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. He is best known for his novels depicting the flamboyance and exces ...

; Ian Hamilton wrote that Salinger even saw himself for some time as "Fitzgerald's successor". Salinger's "A Perfect Day for Bananafish

"A Perfect Day for Bananafish" is a short story by J. D. Salinger, originally published in the January 31, 1948, issue of ''The New Yorker''. It was anthologized in 1949's ''55 Short Stories from The New Yorker'', as well as in Salinger's 1953 col ...

" has an ending similar to that of Fitzgerald's story "May Day

May Day is a European festival of ancient origins marking the beginning of summer, usually celebrated on 1 May, around halfway between the Northern Hemisphere's March equinox, spring equinox and midsummer June solstice, solstice. Festivities ma ...

".

Salinger wrote friends of a momentous change in his life in 1952, after several years of practicing Zen Buddhism, while reading ''The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna

''The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna'' is an English translation of the Bengali religious text ''Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita'' by Swami Nikhilananda. The text records conversations of Ramakrishna with his disciples, devotees and visitors, recorde ...

'' about Hindu

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

religious teacher Sri Ramakrishna

Ramakrishna (18 February 1836 – 16 August 1886——— —), also called Ramakrishna Paramahansa (; ; ), born Ramakrishna Chattopadhay,M's original Bengali diary page 661, Saturday, 13 February 1886''More About Ramakrishna'' by Swami Prab ...

. He became an adherent of Ramakrishna's Advaita Vedanta Hinduism, which advocated celibacy for those seeking enlightenment, and detachment from human responsibilities such as family. Salinger's religious studies were reflected in some of his writing. The story "Teddy

Teddy is an English language given name, usually a hypocorism of Edward or Theodore or Theodora. It may refer to:

People Nickname

* Teddy Atlas (born 1956), American boxing trainer and fight commentator

* Teddy Bourne (born 1948), British Olym ...

", published in 1953, features a ten-year-old child who expresses Vedantic

''Vedanta'' (; , ), also known as ''Uttara Mīmāṃsā'', is one of the six orthodox ( ''āstika'') traditions of Hindu philosophy and textual exegesis. The word ''Vedanta'' means 'conclusion of the Vedas', and encompasses the ideas that e ...

insights. He also studied the writings of Ramakrishna's disciple Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda () (12 January 1863 – 4 July 1902), born Narendranath Datta, was an Indian Hindu monk, philosopher, author, religious teacher, and the chief disciple of the Indian mystic Ramakrishna. Vivekananda was a major figure in th ...

; in " Hapworth 16, 1924", Seymour Glass calls him "one of the most exciting, original and best-equipped giants of this century."

In 1953, Salinger published a collection of seven stories from ''The New Yorker'' (including "Bananafish"), as well as two the magazine had rejected. The collection was published as '' Nine Stories'' in the United States, and "For Esmé—with Love and Squalor

"For Esmé—with Love and Squalor" is a short story by J. D. Salinger. It recounts an American sergeant's meeting with a young girl before being sent into combat in World War II. Originally published in ''The New Yorker'' on April 8, 1950, it was ...

" in the UK, after one of Salinger's best-known stories. The book received grudgingly positive reviews, and was a financial success—"remarkably so for a volume of short stories," according to Hamilton. ''Nine Stories'' spent three months on the ''New York Times'' Bestseller list.

As ''The Catcher in the Rye''Cornish, New Hampshire

Cornish is a town in Sullivan County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 1,616 at the 2020 census. Cornish has four covered bridges. Each August, it is home to the Cornish Fair.

History

The town was granted in 1763 and containe ...

. Early in his time at Cornish he was relatively sociable, particularly with students at Windsor High School. Salinger invited them to his house frequently to play records and talk about problems at school. One such student, Shirley Blaney, persuaded Salinger to be interviewed for the high school page of ''The Daily Eagle,'' the city paper. After the interview appeared prominently in the newspaper's editorial section, Salinger cut off all contact with the high schoolers without explanation. He was also seen less frequently around town, meeting only one close friend—jurist Learned Hand

Billings Learned Hand ( ; January 27, 1872 – August 18, 1961) was an American jurist, lawyer, and judicial philosopher. He served as a federal trial judge on the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York from 1909 to 1924 a ...

—with any regularity.

Second marriage, family, and spiritual beliefs

In February 1955, at age 36, Salinger married Claire Douglas (b. 1933), a Radcliffe student who was art criticRobert Langton Douglas

Robert Langton Douglas (1 March 1864, Lavenham – 14 August 1951, Fiesole) was a British art critic, lecturer, author, and director of the National Gallery of Ireland. He was nominated, thrice, for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1903 Nobel Pri ...

's daughter. They had two children, Margaret Salinger (also known as Peggy – born December 10, 1955) and Matthew "Matt" Salinger (born February 13, 1960). Margaret Salinger wrote in her memoir ''Dream Catcher'' that she believes her parents would not have married, nor would she have been born, had her father not read the teachings of Lahiri Mahasaya

Shyama Charan Lahiri (30 September 1828 – 26 September 1895), best known as Lahiri Mahasaya, was an Indian yoga, yogi and guru who founded the Kriya Yoga (Yoga school), Kriya Yoga school. He was a disciple of Mahavatar Babaji. Lahiri Mahas ...

, a guru of Paramahansa Yogananda

Paramahansa Yogananda (born Mukunda Lal Ghosh; January 5, 1893March 7, 1952) was an Indian and American Hindu monk, yoga, yogi and guru who introduced millions to meditation and Kriya Yoga school, Kriya Yoga through his organization, Self ...

, which brought the possibility of enlightenment to those following the path of the "householder" (a married person with children). After their marriage, Salinger and Claire were initiated into the path of Kriya Yoga

''Kriyā'' (Sanskrit: क्रिया, 'action, deed, effort') is a "completed action", technique or practice within a yoga discipline meant to achieve a specific result.

Kriya or Kriya Yoga may also refer to:

* Kriya Yoga in the Yoga Sutras of ...

in a small store-front Hindu temple in Washington, D.C., during the summer of 1955. They received a mantra and breathing exercise to practice for ten minutes twice a day.

Salinger also insisted that Claire drop out of school and live with him, only four months shy of graduation, which she did. Certain elements of the story "Franny," published in January 1955, are based on his relationship with Claire, including her ownership of the book '' The Way of the Pilgrim''. Because of their isolated location in Cornish and Salinger's proclivities, they hardly saw other people for long stretches of time. Claire was also frustrated by Salinger's ever-changing religious beliefs. Though she committed herself to Kriya yoga, Salinger chronically left Cornish to work on a story "for several weeks only to return with the piece he was supposed to be finishing all undone or destroyed and some new 'ism' we had to follow." Claire believed "it was to cover the fact that Jerry had just destroyed or junked or couldn't face the quality of, or couldn't face publishing, what he had created."

After abandoning Kriya yoga, Salinger tried Dianetics

Dianetics is a set of pseudoscientific ideas and practices regarding the human mind, which were invented in 1950 by science fiction writer L.Ron Hubbard. Dianetics was originally conceived as a form of psychological treatment, but was reje ...

(the forerunner of Scientology

Scientology is a set of beliefs and practices invented by the American author L. Ron Hubbard, and an associated movement. It is variously defined as a scam, a Scientology as a business, business, a cult, or a religion. Hubbard initially develo ...

), even meeting its founder L. Ron Hubbard

Lafayette Ronald Hubbard (March 13, 1911 – January 24, 1986) was an American author and the founder of Scientology. A prolific writer of pulp science fiction and fantasy novels in his early career, in 1950 he authored the pseudoscie ...

, but according to Claire was quickly disenchanted with it. This was followed by an adherence to a number of spiritual, medical, and nutritional belief systems, including Christian Science

Christian Science is a set of beliefs and practices which are associated with members of the Church of Christ, Scientist. Adherents are commonly known as Christian Scientists or students of Christian Science, and the church is sometimes in ...

, Edgar Cayce

Edgar Cayce (; March 18, 1877 – January 3, 1945) was an American clairvoyant who claimed to diagnose diseases and recommend treatments for ailments while asleep. During thousands of transcribed sessions, Cayce would answer questions on ...

, homeopathy

Homeopathy or homoeopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine. It was conceived in 1796 by the German physician Samuel Hahnemann. Its practitioners, called homeopaths or homeopathic physicians, believe that a substance that ...

, acupuncture

Acupuncture is a form of alternative medicine and a component of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in which thin needles are inserted into the body. Acupuncture is a pseudoscience; the theories and practices of TCM are not based on scientif ...

, macrobiotics

A macrobiotic diet (or macrobiotics) is an unconventional restrictive diet based on ideas about types of food drawn from Zen Buddhism. The diet tries to balance the supposed yin and yang elements of food and cookware. Major principles of macrobio ...

, and, like a number of other writers in the 1960s, Sufism

Sufism ( or ) is a mysticism, mystic body of religious practice found within Islam which is characterized by a focus on Islamic Tazkiyah, purification, spirituality, ritualism, and Asceticism#Islam, asceticism.

Practitioners of Sufism are r ...

.

Salinger's family life was further marked by discord after his first child was born; according to Margaret's book, Claire felt that her daughter had replaced her in Salinger's affections. The infant Margaret was sick much of the time, but Salinger, having embraced Christian Science, refused to take her to a doctor. According to Margaret, her mother admitted to her years later that she went "over the edge" in the winter of 1957 and had made plans to murder her and then commit suicide. Claire had supposedly intended to do it during a trip to New York City with Salinger, but she instead acted on a sudden impulse to take Margaret from the hotel and run away. After a few months, Salinger persuaded her to return to Cornish.

The Salingers divorced in 1967, with Claire getting custody of the children. Salinger remained close to his family. He built a new house for himself across the road and visited frequently; he continued to live there until his death in 2010.

Last publications and Maynard relationship

Salinger published ''

Salinger published ''Franny and Zooey

''Franny ''and'' Zooey'' is a book by American author J. D. Salinger which comprises his short story "Franny" and novella ''Zooey'' . The two works were published together as a book in 1961, having originally appeared in ''The New Yorker'' in 195 ...

'' in 1961 and '' Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction'' in 1963. Each book contained two short stories or novellas published in ''The New Yorker'' between 1955 and 1959, and were the only stories Salinger had published since ''Nine Stories''. On the dust jacket of ''Franny and Zooey,'' Salinger wrote, in reference to his interest in privacy: "It is my rather subversive opinion that a writer's feelings of anonymity-obscurity are the second most valuable property on loan to him during his working years."

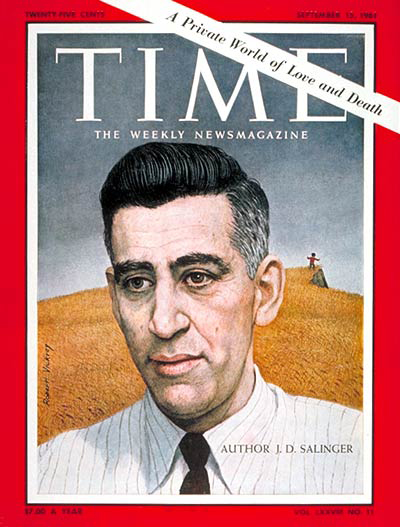

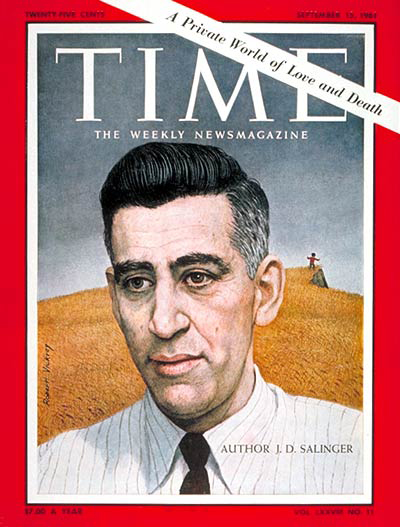

On September 15, 1961, ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' magazine devoted its cover to Salinger. In an article that profiled his "life of recluse", the magazine reported that the Glass family series "is nowhere near completion ... Salinger intends to write a Glass trilogy." But Salinger published only one other thing after that: " Hapworth 16, 1924", a novella in the form of a long letter by seven-year-old Seymour Glass to his parents from summer camp. His first new work in six years, the novella took up most of the June 19, 1965, issue of ''The New Yorker'', and was universally panned by critics. Around this time, Salinger had isolated Claire from friends and relatives and made her—in Margaret Salinger's words—"a virtual prisoner". Claire separated from him in September 1966; their divorce was finalized on October 3, 1967.

In 1972, at age 53, Salinger had a relationship with 18-year-old Joyce Maynard

Joyce Maynard (born November 5, 1953) is an American novelist and journalist. She began her career in journalism in the 1970s, writing for several publications, most notably '' Seventeen'' magazine and ''The New York Times''. Maynard contributed ...

that lasted for nine months. Maynard was already an experienced writer for '' Seventeen'' magazine. ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' had asked her to write an article that, when published as "An Eighteen-Year-Old Looks Back On Life" on April 23, 1972, made her a celebrity. Salinger wrote her a letter warning about living with fame. After exchanging 25 letters, Maynard moved in with Salinger after her freshman year at Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

. She did not return to Yale that year, and spent ten months as a guest in Salinger's house. The relationship ended, he told Margaret at a family outing, because Maynard wanted children, and he felt he was too old. In her autobiography, Maynard paints a different picture, saying Salinger abruptly ended the relationship, sent her away and refused to take her back. She had dropped out of Yale to be with him, even forgoing a scholarship. Maynard came to find out that Salinger had begun several relationships with young women by exchanging letters. One of them was his last wife, a nurse who was already engaged to be married to someone else when she met him. In a 2021 ''Vanity Fair'' article, Maynard wrote,

While living with Maynard, Salinger continued to write in a disciplined fashion, a few hours every morning. According to Maynard, by 1972 he had completed two new novels. In a 1974 interview with ''The New York Times'', he said, "There is a marvelous peace in not publishing ... I like to write. I love to write. But I write just for myself and my own pleasure." According to Maynard, he saw publication as "a damned interruption". In her memoir, Margaret Salinger describes the detailed filing system her father had for his unpublished manuscripts: "A red mark meant, if I die before I finish my work, publish this 'as is,' blue meant publish but edit first, and so on." A neighbor said that Salinger told him that he had written 15 unpublished novels.

Salinger's final interview was in June 1980 with Betty Eppes of '' The Baton Rouge Advocate'', which has been represented somewhat differently, depending on the secondary source. By one account, Eppes was an attractive young woman who misrepresented herself as an aspiring novelist, and managed to record audio of the interview as well as take several photographs of Salinger, both without his knowledge or consent. In a separate account, emphasis is placed on her contact by letter writing from the local post office, and Salinger's personal initiative to cross the bridge to meet Eppes, who during the interview made clear she was a reporter and did, at the close, take pictures of Salinger as he departed. According to the first account, the interview ended "disastrously" when a passerby from Cornish attempted to shake Salinger's hand, at which point Salinger became enraged. A further account of the interview published in ''The Paris Review

''The Paris Review'' is a quarterly English-language literary magazine established in Paris in 1953 by Harold L. Humes, Peter Matthiessen, and George Plimpton. In its first five years, ''The Paris Review'' published new works by Jack Kerouac, ...

'', purportedly by Eppes, has been disowned by her and separately ascribed as a derived work of ''Review'' editor George Plimpton

George Ames Plimpton (March 18, 1927 – September 25, 2003) was an American writer. He is known for his sports writing and for helping to found ''The Paris Review'', as well as his patrician demeanor and accent. He was known for " participat ...

. In an interview published in August 2021, Eppes said that she did record her conversation with Salinger without his knowledge but that she was plagued by guilt over it. She said that she had turned down several lucrative offers for the tape, the only known recording of Salinger's voice, and that she had changed her will to stipulate that it be placed along with her body in the crematorium.

Salinger was romantically involved with television actress Elaine Joyce

Elaine Joyce (born Elaine Joyce Pinchot) is an American actress.

Early life and education

Elaine Joyce Pinchot was born in Kansas City, Missouri, of Hungarian ancestry, the daughter of Iliclina (née Nagy) and Frank Pinchot.

Career

She made ...

for several years in the 1980s. The relationship ended when he met Colleen O'Neill, a nurse and quiltmaker, whom he married around 1988. O'Neill, 40 years his junior, once told Margaret Salinger that she and Salinger were trying to have a child. They did not succeed.

Legal conflicts

Although Salinger tried to escape public exposure as much as possible, he struggled with unwanted attention from the media and the public. Readers of his work and students from nearbyDartmouth College

Dartmouth College ( ) is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Hanover, New Hampshire, United States. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, Dartmouth is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the America ...

often came to Cornish in groups, hoping to catch a glimpse of him. In May 1986 Salinger learned that the British writer Ian Hamilton intended to publish a biography that made extensive use of letters Salinger had written to other authors and friends. Salinger sued to stop the book's publication and in ''Salinger v. Random House

''Salinger v. Random House, Inc.'', 811 F.2d 90 (2d Cir. 1987) is a United States case on the application of copyright law to unpublished works. In a case about author J. D. Salinger's unpublished letters, the Second Circuit held that the right ...

'', the court ruled that Hamilton's extensive use of the letters, including quotation and paraphrasing, was not acceptable since the author's right to control publication overrode the right of fair use. Hamilton published ''In Search of J.D. Salinger: A Writing Life (1935–65)'' about his experience in tracking down information and the copyright fights over the planned biography.

An unintended consequence of the lawsuit was that many details of Salinger's private life, including that he had spent the last 20 years writing, in his words, "Just a work of fiction ... That's all" became public in the form of court transcripts. Excerpts from his letters were also widely disseminated, most notably a bitter remark written in response to Oona O'Neill

Oona O'Neill, Lady Chaplin (14 May 1925 – 27 September 1991) was a British actress, the daughter of American playwright Eugene O'Neill and English-born writer Agnes Boulton, and the fourth and last wife of actor and filmmaker Charlie Chaplin.

...

's marriage to Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is considered o ...

:

In 1995, Iranian director Dariush Mehrjui

Dariush Mehrjui (; 8 December 1939 – 14 October 2023) was an Iranian filmmaker and a member of the Iranian Academy of the Arts.

Mehrjui was a founding member of the Iranian New Wave movement of the early 1970s, which also included direc ...

released the film '' Pari'', an unauthorized loose adaptation of ''Franny and Zooey''. The film could be distributed legally in Iran since it has no copyright relations with the United States, but Salinger had his lawyers block a planned 1998 screening of it at Lincoln Center

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts (also simply known as Lincoln Center) is a complex of buildings in the Lincoln Square neighborhood on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. It has thirty indoor and outdoor facilities and is host to 5 ...

. Mehrjui called Salinger's action "bewildering", explaining that he saw his film as "a kind of cultural exchange".

In 1996, Salinger gave a small publisher, Orchises Press, permission to publish " Hapworth 16, 1924". It was to be published that year and listings for it appeared at Amazon.com

Amazon.com, Inc., doing business as Amazon, is an American multinational technology company engaged in e-commerce, cloud computing, online advertising, digital streaming, and artificial intelligence. Founded in 1994 by Jeff Bezos in Bellevu ...

and other booksellers. After a flurry of articles and critical reviews of the story appeared in the press, the publication date was repeatedly delayed before apparently being canceled altogether. Amazon anticipated that Orchises would publish the story in 2009, but at the time of Salinger's death, it was still listed as "unavailable".

In June 2009, Salinger consulted lawyers about the forthcoming U.S. publication of an unauthorized sequel to ''The Catcher in the Rye'', '' 60 Years Later: Coming Through the Rye'', by Swedish book publisher Fredrik Colting under the pseudonym J. D. California. The book appears to continue the story of Holden Caulfield. In Salinger's novel, Caulfield is 16, wandering the streets of New York after being expelled from private school; the California book features a 76-year-old man, "Mr. C", musing on having escaped his nursing home. Salinger's New York literary agent Phyllis Westberg told Britain's ''Sunday Telegraph

''The Sunday Telegraph'' is a British broadsheet newspaper, first published on 5 February 1961 and published by the Telegraph Media Group, a division of Press Holdings. It is the sister paper of ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegr ...

'', "The matter has been turned over to a lawyer". The fact that little was known about Colting and the book was set to be published by a new publishing imprint, Windupbird Publishing, gave rise to speculation in literary circles that the whole thing might be a hoax. District court judge Deborah Batts

Deborah Anne Batts (April 13, 1947 – February 3, 2020) was a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. During Gay Pride Week in June 1994, Batts was sworn in as a United States distr ...

issued an injunction

An injunction is an equitable remedy in the form of a special court order compelling a party to do or refrain from doing certain acts. It was developed by the English courts of equity but its origins go back to Roman law and the equitable rem ...

that prevented the book from being published in the U.S. Colting filed an appeal on July 23, 2009; it was heard in the Second Circuit Court of Appeals on September 3, 2009. The case was settled in 2011 when Colting agreed not to publish or otherwise distribute the book, e-book, or any other editions of ''60 Years Later'' in the U.S. or Canada until ''The Catcher in the Rye'' enters the public domain, and to refrain from using the title ''Coming through the Rye'', dedicating the book to Salinger, or referring to ''The Catcher in the Rye''. Colting remains free to sell the book in the rest of the world.

Later publicity

On October 23, 1992, ''The New York Times'' reported, "Not even a fire that consumed at least half his home on Tuesday could smoke out the reclusive J. D. Salinger, author of the classic novel of adolescent rebellion, ''The Catcher in the Rye''. Mr. Salinger is almost equally famous for having elevated privacy to an art form." In 1999, 25 years after the end of their relationship, Maynard auctioned a series of letters Salinger had written her. Her memoir ''At Home in the World'' was published the same year. The book describes how Maynard's mother had consulted with her on how to appeal to Salinger by dressing in a childlike manner, and describes Maynard's relationship with him at length. In the ensuing controversy over the memoir and the letters, Maynard claimed that she was forced to auction the letters for financial reasons; she would have preferred to donate them to theBeinecke Library

The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library () is the rare book library and literary archive of the Yale University Library in New Haven, Connecticut. It is one of the largest buildings in the world dedicated to rare books and manuscripts and ...

at Yale

Yale University is a private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, and one of the nine colonial colleges ch ...

. Software developer Peter Norton

Peter Norton (born November 14, 1943) is an American programmer, software publisher, author, and philanthropist. He is best known for the computer programs and books that bear his name and portrait. Norton sold his software business to Symante ...

bought the letters for $156,500 and announced that he would return them to Salinger.

A year later, Margaret Salinger published ''Dream Catcher: A Memoir''. In it, she describes the harrowing control Salinger had over her mother and dispelled many of the Salinger myths established by Hamilton's book. One of Hamilton's arguments was that Salinger's experience with post-traumatic stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental disorder that develops from experiencing a Psychological trauma, traumatic event, such as sexual assault, domestic violence, child abuse, warfare and its associated traumas, natural disaster ...

left him psychologically scarred. Margaret Salinger allowed that "the few men who lived through Bloody Mortain", a battle in which her father fought, "were left with much to sicken them, body and soul", but she also painted her father as a man immensely proud of his service record, maintaining his military haircut and service jacket, and moving about his compound (and town) in an old Jeep

Jeep is an American automobile brand, now owned by multi-national corporation Stellantis. Jeep has been part of Chrysler since 1987, when Chrysler acquired the Jeep brand, along with other assets, from its previous owner, American Motors Co ...

.

Both Margaret Salinger and Maynard characterized Salinger as a film buff. According to Margaret, his favorite movies included '' Gigi'' (1958), ''The Lady Vanishes

''The Lady Vanishes'' is a 1938 British Mystery film, mystery Thriller (genre), thriller film directed by Alfred Hitchcock, starring Margaret Lockwood and Michael Redgrave. Written by Sidney Gilliat and Frank Launder, based on the 1936 novel '' ...

'' (1938), '' The 39 Steps'' (1935; Phoebe's favorite movie in ''The Catcher in the Rye''), and the comedies of W. C. Fields

William Claude Dukenfield (January 29, 1880 – December 25, 1946), better known as W. C. Fields, was an American actor, comedian, juggler and writer. His career in show business began in vaudeville, where he attained international success as a ...

, Laurel and Hardy

Laurel and Hardy were a British-American double act, comedy duo during the early Classical Hollywood cinema, Classical Hollywood era of American cinema, consisting of Englishman Stan Laurel (1890–1965) and American Oliver Hardy (1892–1957) ...

, and the Marx Brothers

The Marx Brothers were an American family comedy act known for their anarchic humor, rapid-fire wordplay, and visual gags. They achieved success in vaudeville, on Broadway, and in 14 motion pictures. The core group consisted of brothers Chi ...

. Predating VCRs, Salinger had an extensive collection of classic movies from the 1940s in 16 mm prints. Maynard wrote that "he loves movies, not films", and Margaret Salinger argued that her father's "worldview is, essentially, a product of the movies of his day. To my father, all Spanish speakers are Puerto Rican washerwomen, or the toothless, grinning-gypsy types in a Marx Brothers movie." Lillian Ross, a staff writer for ''The New Yorker'' and longtime friend of Salinger's, wrote after his death, "Salinger loved movies, and he was more fun than anyone to discuss them with. He enjoyed watching actors work, and he enjoyed knowing them. (He loved Anne Bancroft

Anne Bancroft (born Anna Maria Louisa Italiano; September 17, 1931 – June 6, 2005) was an American actress. Respected for her acting prowess and versatility, Bancroft received an Academy Award, three BAFTA Awards, two Golden Globe Awards, tw ...

, hated Audrey Hepburn

Audrey Kathleen Hepburn ( Ruston; 4 May 1929 – 20 January 1993) was a British actress. Recognised as a film and fashion icon, she was ranked by the American Film Institute as the third-greatest female screen legend from the Classical Holly ...

, and said that he had seen '' Grand Illusion'' ten times.)"

Margaret also offered many insights into other Salinger myths, including her father's supposed longtime interest in macrobiotics

A macrobiotic diet (or macrobiotics) is an unconventional restrictive diet based on ideas about types of food drawn from Zen Buddhism. The diet tries to balance the supposed yin and yang elements of food and cookware. Major principles of macrobio ...