Jeremiah Horrox on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jeremiah Horrocks (16183 January 1641), sometimes given as Jeremiah Horrox (the Latinised version that he used on the Emmanuel College register and in his Latin manuscripts), – See footnote 1 was an English

About the Jeremiah Horrocks Institute

, University of Central Lancashire In 2012 it was renamed the Jeremiah Horrocks Institute for Mathematics, Physics, and Astronomy.

' Smithsonian Institution Libraries

BBC report: Celebrating Horrocks' half hour

Horrocks memorial in Westminster Abbey

*

Jeremiah Horrocks Institute

{{DEFAULTSORT:Horrocks, Jeremiah 1618 births 1641 deaths 17th-century English astronomers Alumni of Emmanuel College, Cambridge Scientists from Liverpool 17th-century English mathematicians Toxteth Transit of Venus

astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. Astronomers observe astronomical objects, such as stars, planets, natural satellite, moons, comets and galaxy, galax ...

. He was the first person to demonstrate that the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). The Moon rotation, rotates, with a rotation period (lunar ...

moved around the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

in an elliptical orbit; and he was the only person to predict the transit of Venus of 1639, an event which he and his friend William Crabtree

William Crabtree (1610 – 1644) was an English astronomer, mathematician, and merchant from Broughton, then in the Hundred of Salford, Lancashire, England. He was one of only two people to observe and record the first predicted transit of ...

were the only two people to observe and record. Most remarkably, Horrocks correctly asserted that Jupiter was accelerating in its orbit while Saturn was slowing and interpreted this as due to mutual gravitational interaction, thereby demonstrating that gravity's actions were not limited to the Earth, Sun, and Moon.

His early death and the chaos of the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

nearly caused the loss to science of his treatise on the transit, ''Venus in sole visa''; but for this and his other work he is acknowledged as one of the founding fathers of British astronomy.

Early life and education

Jeremiah Horrocks was born at Lower Lodge Farm inToxteth

Toxteth is an inner-city area of Liverpool in the county of Merseyside.

Toxteth is located to the south of Liverpool city centre, bordered by Aigburth, Canning, Liverpool, Canning, Dingle, Liverpool, Dingle, and Edge Hill, Merseyside, Edge Hill ...

Park, a former royal deer park near Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

, Lancashire. His father James had moved to Toxteth Park to be apprenticed to Thomas Aspinwall, a watchmaker

A watchmaker is an artisan who makes and repairs watches. Since a majority of watches are now factory-made, most modern watchmakers only repair watches. However, originally they were master craftsmen who built watches, including all their par ...

, and subsequently married his master's daughter Mary. Both families were well educated Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

s; the Horrocks sent their younger sons to the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

and the Aspinwalls favoured Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

. For their unorthodox beliefs the Puritans were excluded from public office, which tended to push them towards other callings; by 1600 the Aspinwalls had become a successful family of watchmakers. Jeremiah was introduced early to astronomy; his boyhood chores included measuring the local noon used to set local clocks, and his Puritan upbringing instilled an enduring suspicion of astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions ...

, witchcraft

Witchcraft is the use of Magic (supernatural), magic by a person called a witch. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic to inflict supernatural harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meanin ...

and magic

Magic or magick most commonly refers to:

* Magic (supernatural), beliefs and actions employed to influence supernatural beings and forces

** ''Magick'' (with ''-ck'') can specifically refer to ceremonial magic

* Magic (illusion), also known as sta ...

.

In 1632, Horrocks matriculated

Matriculation is the formal process of entering a university, or of becoming eligible to enter by fulfilling certain academic requirements such as a matriculation examination.

Australia

In Australia, the term ''matriculation'' is seldom used now ...

at Emmanuel College at the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

as a sizar

At Trinity College Dublin and the University of Cambridge, a sizar is an Undergraduate education, undergraduate who receives some form of assistance such as meals, lower fees or lodging during his or her period of study, in some cases in retur ...

. At Cambridge he associated with the mathematician John Wallis

John Wallis (; ; ) was an English clergyman and mathematician, who is given partial credit for the development of infinitesimal calculus.

Between 1643 and 1689 Wallis served as chief cryptographer for Parliament and, later, the royal court. ...

and the platonist

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato and philosophical systems closely derived from it, though contemporary Platonists do not necessarily accept all doctrines of Plato. Platonism has had a profound effect on Western thought. At the most fundam ...

John Worthington. At that time he was one of only a few at Cambridge to accept Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

's revolutionary heliocentric

Heliocentrism (also known as the heliocentric model) is a Superseded theories in science#Astronomy and cosmology, superseded astronomical model in which the Earth and Solar System, planets orbit around the Sun at the center of the universe. His ...

theory, and he studied the works of Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best know ...

, Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe, ; 14 December 154624 October 1601), generally called Tycho for short, was a Danish astronomer of the Renaissance, known for his comprehensive and unprecedentedly accurate astronomical observations. He ...

and others.

In 1635, for reasons not clear, Horrocks left Cambridge without graduating. Marston suggests that he may have needed to defer the extra cost this entailed until he was employed, whilst Aughton speculates that he may have failed his exams due to concentrating too much on his own interests, or that he did not want to take Anglican orders, and so a degree was of limited use to him.

Astronomical observations

Now committed to the study of astronomy, Horrocks began to collect astronomical books and equipment; by 1638 he owned the best telescope he could find. Liverpool was a seafaring town so navigational instruments such as theastrolabe

An astrolabe (; ; ) is an astronomy, astronomical list of astronomical instruments, instrument dating to ancient times. It serves as a star chart and Model#Physical model, physical model of the visible celestial sphere, half-dome of the sky. It ...

and cross staff were easy to find. But there was no market for the very specialised astronomical instruments he needed, so his only option was to make his own. He was well placed to do this; his father and uncles were watchmakers with expertise in creating precise instruments. Apparently he helped with the family business by day and, in return, the watchmakers in his family supported his vocation by assisting in the design and construction of instruments to study the stars at night.

Horrocks owned a three-foot ''radius astronomicus'' – a cross staff with movable sights used to measure the angle between two stars – but by January 1637 he had reached the limitations of this instrument and so built a larger and higher precision version. While a youth he read most of the astronomical treatises of his day and marked their weaknesses; by the age of seventeen he was suggesting new lines of research.

Tradition has it that after he left home he supported himself by holding a curacy

A curate () is a person who is invested with the ''care'' or ''cure'' () of souls of a parish. In this sense, ''curate'' means a parish priest; but in English-speaking countries the term ''curate'' is commonly used to describe clergy who are ass ...

in Much Hoole

Much Hoole is a village and civil parish in the borough of South Ribble, Lancashire, England. The parish of Much Hoole had a population of 1,851 at the time of the 2001 census, increasing to 1,997 at the 2011 Census.

History

Hoole derives fro ...

, near Preston in Lancashire, but there is little evidence for this. According to local tradition in Much Hoole, he lived at Carr House, within the Bank Hall

Bank Hall is a Jacobean mansion in Bretherton, Lancashire, England. It is a Grade II* listed building and is at the centre of a private estate, surrounded by parkland. The hall was built on the site of an older house in 1608 by the Banastres w ...

Estate, Bretherton

Bretherton is a small village and civil parish in the Borough of Chorley, Lancashire, England, situated to the south west of Leyland and east of Tarleton. The population of the civil parish at the 2011 census was 669. Its name suggests pre-c ...

. Carr House was a substantial property owned by the Stones family who were prosperous farmers and merchants, and Horrocks was probably a tutor for the Stones' children.

Lunar research

Horrocks was the first to demonstrate that theMoon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). The Moon rotation, rotates, with a rotation period (lunar ...

moved in an elliptical path around the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

, and he posited that comets followed elliptical orbits. He supported his theories by analogy to the motions of a conical pendulum, noting that after a plumb bob was drawn back and released it followed an elliptical path, and that its major axis rotated in the direction of revolution as did the apsides

An apsis (; ) is the farthest or nearest point in the orbit of a planetary body about its primary body. The line of apsides (also called apse line, or major axis of the orbit) is the line connecting the two extreme values.

Apsides perta ...

of the Moon's orbit. He anticipated Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

in suggesting the influence of the Sun as well as the Earth on the Moon's orbit. In the ''Principia

Principia may refer to:

* ''Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica'', Isaac Newton's three-volume work about his laws of motion and universal gravitation

* Principia ( "primary buildings"), the headquarters at the center of Roman forts ()

* ...

'' Newton acknowledged Horrocks's work in relation to his theory of lunar motion. In the final months of his life Horrocks made detailed studies of tides

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ...

in attempting to explain the nature of lunar causation of tidal movements.

Transit of Venus

Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best know ...

had published his Rudolphine Tables

The ''Rudolphine Tables'' () consist of a star catalogue and planetary tables published by Johannes Kepler in 1627, using observational data collected by Tycho Brahe (1546–1601). The tables are named in memory of Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emper ...

in 1627. Two years later he published extracts from the tables in his pamphlet ''De raris mirisque Anni 1631'', which included an ''admonitio ad astronomos'' (warning to astronomers) concerning a transit of Mercury

file:Mercury transit symbol.svg, frameless, upright=0.5

A transit of Mercury across the Sun takes place when the planet Mercury (planet), Mercury passes directly between the Sun and a superior planet. During a Astronomical transit, transit, Merc ...

in 1631 and transits of Venus in 1631 and 1761. Horrocks' own observations, combined with those of his friend and correspondent William Crabtree

William Crabtree (1610 – 1644) was an English astronomer, mathematician, and merchant from Broughton, then in the Hundred of Salford, Lancashire, England. He was one of only two people to observe and record the first predicted transit of ...

, had convinced him that Kepler's Rudolphine tables, although more accurate than the commonly used tables produced by Philip Van Lansberg, were still in need of some correction. Kepler's tables had predicted a near-miss of a transit of Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is often called Earth's "twin" or "sister" planet for having almost the same size and mass, and the closest orbit to Earth's. While both are rocky planets, Venus has an atmosphere much thicker ...

in 1639 but, having made his own observations of Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is often called Earth's "twin" or "sister" planet for having almost the same size and mass, and the closest orbit to Earth's. While both are rocky planets, Venus has an atmosphere much thicker ...

for years, Horrocks predicted a transit would indeed occur.

Horrocks made a simple helioscope

A helioscope is an instrument used in observing the Sun and sunspots.

The helioscope was first used by Benedetto Castelli (1578–1643) and refined by Galileo Galilei (1564–1642). The method involves projecting an image of the sun onto a white ...

by focusing the image of the Sun through a telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, Absorption (electromagnetic radiation), absorption, or Reflection (physics), reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally, it was an optical instrument using len ...

onto a plane surface, whereby an image of the Sun could be safely observed. From his location in Much Hoole

Much Hoole is a village and civil parish in the borough of South Ribble, Lancashire, England. The parish of Much Hoole had a population of 1,851 at the time of the 2001 census, increasing to 1,997 at the 2011 Census.

History

Hoole derives fro ...

he calculated the transit would begin at approximately 3:00 pm on 24 November 1639, Julian calendar

The Julian calendar is a solar calendar of 365 days in every year with an additional leap day every fourth year (without exception). The Julian calendar is still used as a religious calendar in parts of the Eastern Orthodox Church and in parts ...

(or 4 December in the Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It went into effect in October 1582 following the papal bull issued by Pope Gregory XIII, which introduced it as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian cale ...

). The weather was cloudy but he first observed the tiny black shadow of Venus crossing the Sun at about 3:15 pm; and he continued to observe for half an hour until the Sun set. The 1639 transit was also observed by William Crabtree from his home in Broughton near Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

.

Horrocks' observations allowed him to make a well-informed guess as to the size of Venus—previously thought to be larger and closer to Earth—and to estimate the distance between the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

and the Sun, now known as the astronomical unit (AU). His figure of 95 million kilometres (59 million miles, 0.63 AU) was far from the 150 million kilometres (93 million miles) known today, but it was more accurate than any suggested up to that time.

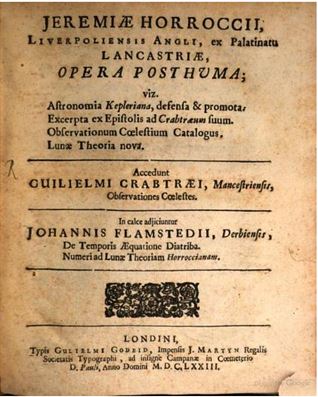

A treatise by Horrocks on the study of the transit, ''Venus in sole visa'' (''Venus seen on the Sun''), was later published by the Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius

Johannes Hevelius

Some sources refer to Hevelius as Polish:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Some sources refer to Hevelius as German:

*

*

*

*

*of the Royal Society

* (in German also known as ''Hevel''; ; – 28 January 1687) was a councillor and mayor of Danz ...

at his own expense; it caused great excitement when revealed to members of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1662, some 20 years after it was written. It presented Horrocks' enthusiastic and romantic nature, including humorous comments and passages of original poetry. When speaking of the century separating Venusian transits, he rhapsodised:

:" ...Thy return

:Posterity shall witness; years must roll

:Away, but then at length the splendid sight

:Again shall greet our distant children's eyes."

It was a time of great uncertainty in astronomy, when the world's astronomers could not agree amongst themselves and theologians fulminated against claims that contradicted Scripture. Horrocks, although a pious young man, came down firmly on the side of scientific determinism

Determinism is the metaphysical view that all events within the universe (or multiverse) can occur only in one possible way. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from diverse and sometimes overlapping mot ...

.

It is wrong to hold the most noble Science of the Stars guilty of uncertainty on account of some people's uncertain observations. Through no fault of its own it suffers these complaints which arise from the uncertainty and error not of the celestial motions but of human observations . . . I do not consider that any imperfections in the motions of the stars have so far been detected, nor do I believe that they are ever to be found. Far be it from me to allow that God has created the heavenly bodies more imperfectly than man has observed them. – Jeremiah Horrocks

Death

Horrocks returned to Toxteth Park sometime in mid-1640 and died suddenly from unknown causes on 3 January 1641, at the age of 22. As expressed by Crabtree, "What an incalculable loss!" He has been described as a bridge which connectedNewton

Newton most commonly refers to:

* Isaac Newton (1642–1726/1727), English scientist

* Newton (unit), SI unit of force named after Isaac Newton

Newton may also refer to:

People

* Newton (surname), including a list of people with the surname

* ...

with Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

, Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

, Brahe

The Brahe family (originally ''Bragde'') refers to two closely related noble families of Scanian origin that played significant roles in both Danish and Swedish history. The Danish branch became extinct in 1786, and the Swedish branch in 193 ...

and Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws of p ...

.

It is believed that Horrocks was buried at Toxteth Unitarian Chapel

Toxteth Unitarian Chapel is in Park Road, Dingle, Liverpool, Merseyside, England. Since the 1830s it has been known as The Ancient Chapel of Toxteth. It is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade I listed bu ...

, but there is seemingly no proof of this.

Legacy

Horrocks is remembered on a plaque inWestminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

and the lunar crater Horrocks is named after him. In 1859, a marble tablet and stained-glass windows commemorating him were installed in the Parish Church of St Michael, Much Hoole. Toxteth Unitarian Chapel contains a memorial plaque commemorating his achievements. Horrocks Avenue in Garston, Liverpool, is also named after him.

In 1927, the Jeremiah Horrocks Observatory was built at Moor Park, Preston

Moor Park is a large park (with a perimeter of approx ) to the north of the city centre of Preston, Lancashire, England. Moor Park is also the name of the electoral ward covering the park and the surrounding area. The ward borders the traditiona ...

.

The 2012 transit of Venus was marked by a celebration held in the church at Much Hoole, which was streamed live worldwide on the NASA website.

Horrocks and the transit of Venus feature in an episode ("Dark Matter") of the British television series ''Lewis

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* " Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohe ...

''.

In 2011, a sculpture by Andy Plant, titled ''Heaven and Earth'', was installed at the Pier Head

The Pier Head (properly, George's Pier Head) is a riverside location in the city centre of Liverpool, England. It was part of the former Liverpool Maritime Mercantile City UNESCO World Heritage Site, which was inscribed in 2004, but revoked in ...

in Liverpool to celebrate Horrocks's work on the transit of Venus. It consists of a telescope looking at a working orrery

An orrery is a mechanical Solar System model, model of the Solar System that illustrates or predicts the relative positions and motions of the planets and natural satellite, moons, usually according to the heliocentric model. It may also represent ...

which has the planet Venus replaced by a figure of the astronomer depicted as an angel.

In 2023 a new play, ''Horrox'' on Horrocks' short life and overlooked achievements, by playwright David Sear, was staged in Cambridge’s ADC Theatre

The ADC Theatre (full name: ''Amateur Dramatic Club Theatre'') is a theatre in Cambridge, England, and also a department of the University of Cambridge. It is located on Park Street, north off Jesus Lane. The theatre is owned by a trust on be ...

from 28 March to 1 April as part of the Cambridge festival.

Jeremiah Horrocks Institute

The Jeremiah Horrocks Institute for Astrophysics and Supercomputing was established in 1993 at theUniversity of Central Lancashire

The University of Lancashire (previously abbreviated UCLan) is a public university based in the city of Preston, Lancashire, England. It has its roots in ''The Institution For The Diffusion Of Useful Knowledge'', founded in 1828. Previously k ...

., University of Central Lancashire In 2012 it was renamed the Jeremiah Horrocks Institute for Mathematics, Physics, and Astronomy.

References

Bibliography

* *Further reading

* * * * * * * * *External links

*' Smithsonian Institution Libraries

BBC report: Celebrating Horrocks' half hour

Horrocks memorial in Westminster Abbey

*

Jeremiah Horrocks Institute

{{DEFAULTSORT:Horrocks, Jeremiah 1618 births 1641 deaths 17th-century English astronomers Alumni of Emmanuel College, Cambridge Scientists from Liverpool 17th-century English mathematicians Toxteth Transit of Venus