Jefferson Finis Davis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

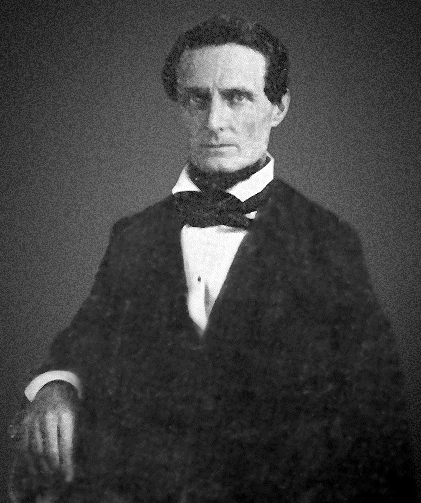

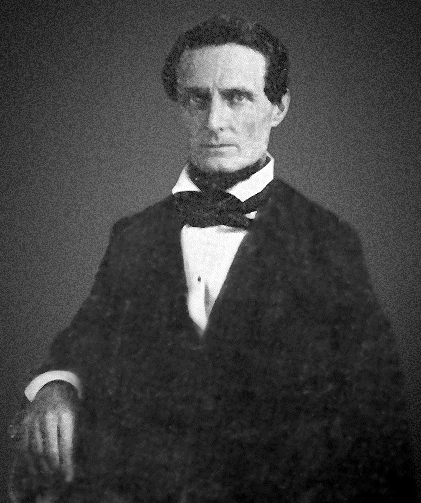

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the only

Davis decided to become a cotton planter. He returned to Mississippi where his brother Joseph had developed Davis Bend into

Davis decided to become a cotton planter. He returned to Mississippi where his brother Joseph had developed Davis Bend into

At the beginning of the

At the beginning of the

Davis took his seat in December 1847 and was made a regent of the

Davis took his seat in December 1847 and was made a regent of the

In March 1853, President Franklin Pierce named Davis his

In March 1853, President Franklin Pierce named Davis his

Before his resignation, Davis had sent a telegraph to Mississippi Governor

Before his resignation, Davis had sent a telegraph to Mississippi Governor

On February 22, Davis was inaugurated as president. In his inaugural speech, he admitted that the South had suffered disasters, but called on the people of the Confederacy to renew their commitment. He replaced Secretary of War Benjamin, who had been scapegoated for the defeats, with George W. Randolph. Davis kept Benjamin in the cabinet, making him secretary of state to replace Hunter, who had stepped down. In March, Davis vetoed a bill to create a commander in chief for the army, but he selected General

On February 22, Davis was inaugurated as president. In his inaugural speech, he admitted that the South had suffered disasters, but called on the people of the Confederacy to renew their commitment. He replaced Secretary of War Benjamin, who had been scapegoated for the defeats, with George W. Randolph. Davis kept Benjamin in the cabinet, making him secretary of state to replace Hunter, who had stepped down. In March, Davis vetoed a bill to create a commander in chief for the army, but he selected General

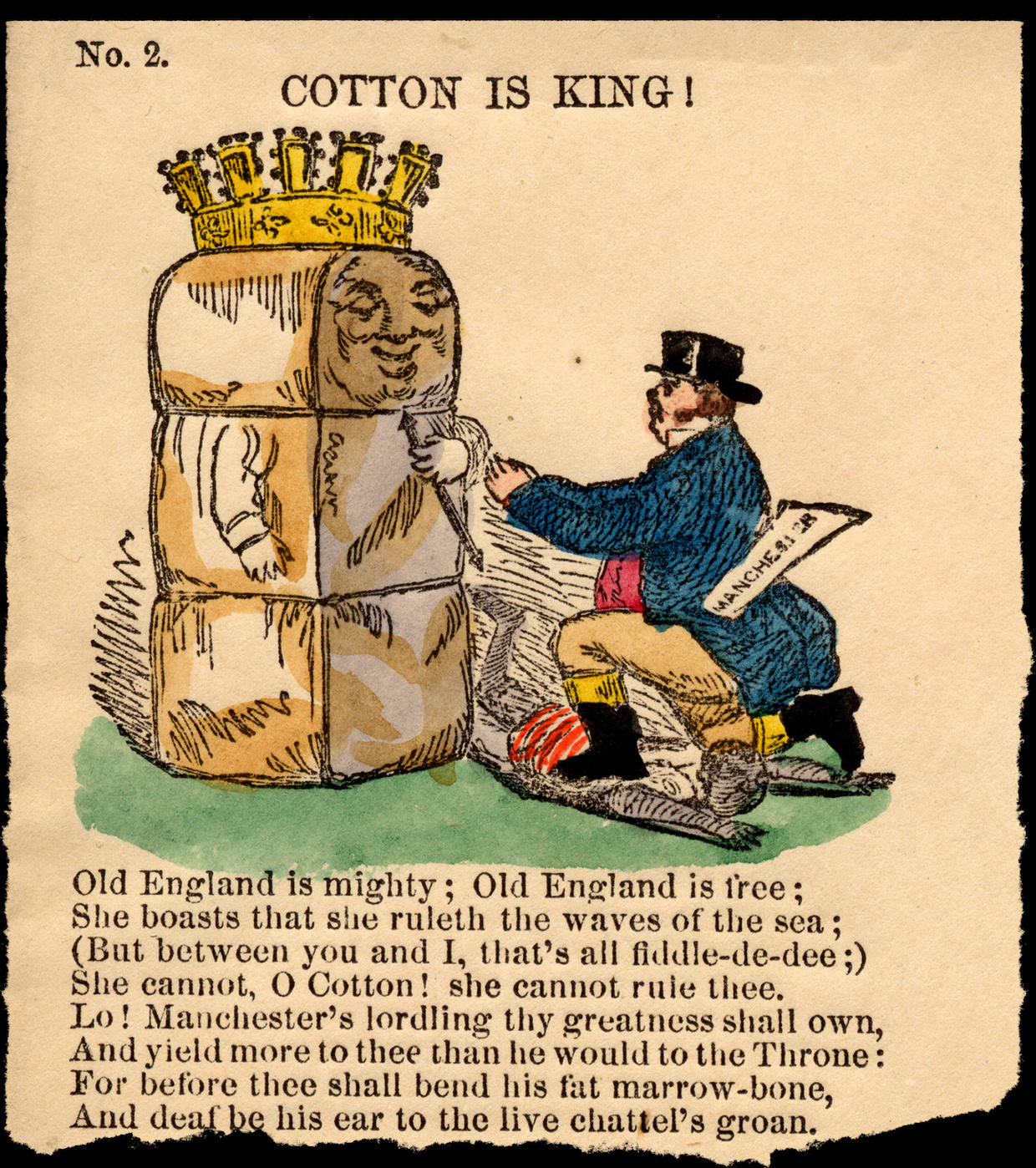

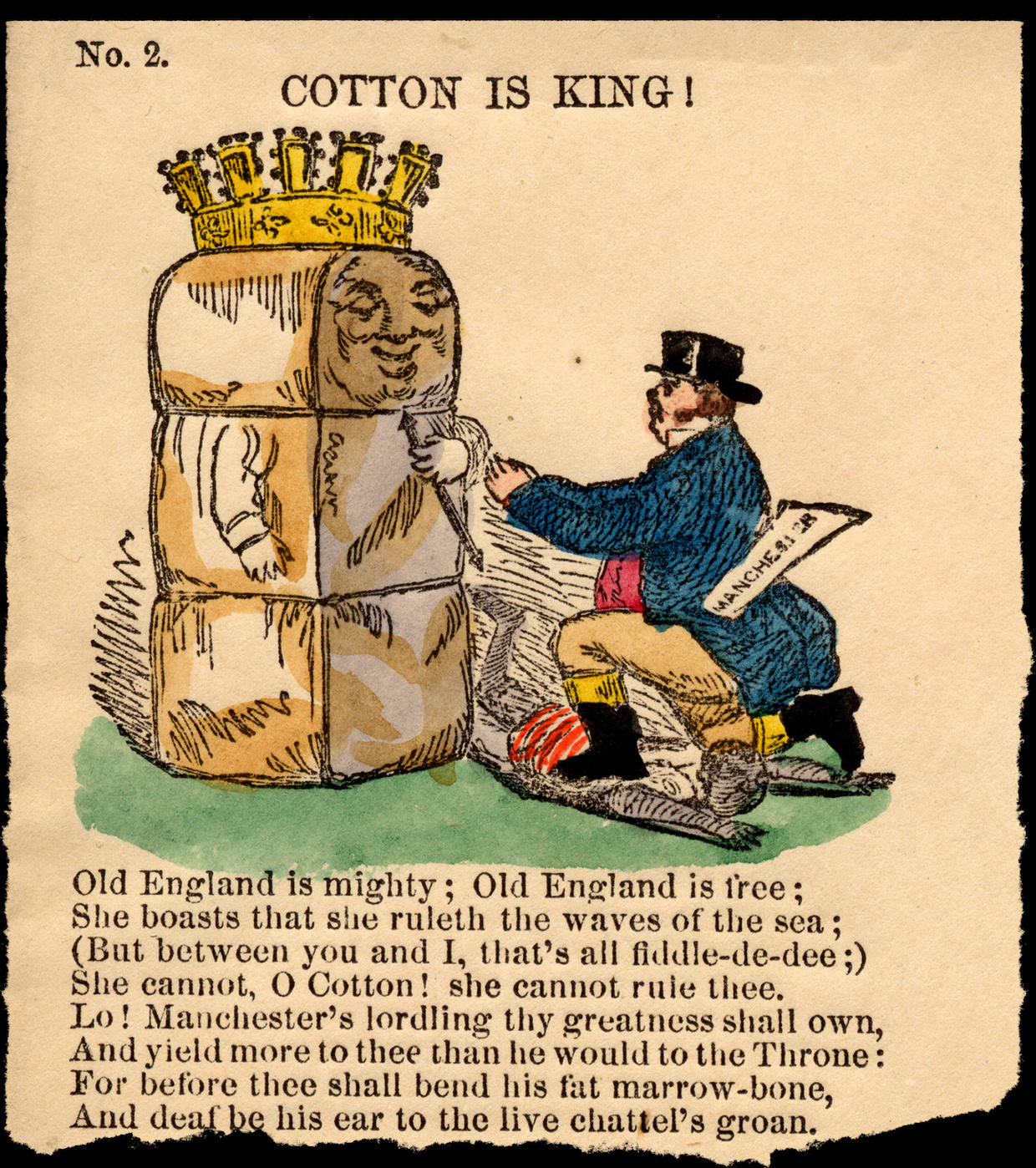

The main objective of Davis's foreign policy was to achieve foreign recognition, allowing the Confederacy to secure international loans, receive foreign aid to open trade, and provide the possibility of a military alliance. Davis was confident that most European nations' economic dependence on cotton from the South would quickly convince them to sign treaties with the Confederacy. Cotton had made up 61% of the value of all U.S. exports and the South filled most of the European cloth industry's need for cheap imported raw cotton.

There was no consensus on how to use cotton to gain European support. Davis did not want an

The main objective of Davis's foreign policy was to achieve foreign recognition, allowing the Confederacy to secure international loans, receive foreign aid to open trade, and provide the possibility of a military alliance. Davis was confident that most European nations' economic dependence on cotton from the South would quickly convince them to sign treaties with the Confederacy. Cotton had made up 61% of the value of all U.S. exports and the South filled most of the European cloth industry's need for cheap imported raw cotton.

There was no consensus on how to use cotton to gain European support. Davis did not want an

Davis received numerous invitations to speak during this time, declining most. In 1870, he delivered a eulogy to Robert E. Lee at the Lee Monument Association in Richmond in which he avoided politics and emphasized Lee's character. Davis's 1873 speech to the

Davis received numerous invitations to speak during this time, declining most. In 1870, he delivered a eulogy to Robert E. Lee at the Lee Monument Association in Richmond in which he avoided politics and emphasized Lee's character. Davis's 1873 speech to the

Vol I. (1824–1850)Vol. II (1850–1856)Vol. III (1856–1856)Vol. IV (1856–January, 1861)Vol. V (January, 1861 – August 1863)Vol. VI (August 1863 – May 1865)Vol. VII (May 1865–1877)Vol. VIII (1877–1881)Vol. IX (1881–1887)Vol. X (1887– 1891; ''includes letters to Varina about Davis''

* (14 Volumes) :* A selection of documents from

The Papers of Jefferson Davis

' is available online: :* Volume 1 is available online: *

Review

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ;Journal articles * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ;Online * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ;Primary sources * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Jefferson Davis

at the

Jefferson Davis

at ''Encyclopedia Virginia'' (encyclopediavirginia.org)

The Jefferson Davis Estate Papers

at the

Jefferson Davis Presidential Library and Museum

*

Works by Jefferson Davis

at

president of the Confederate States

The president of the Confederate States was the head of state and head of government of the unrecognized breakaway Confederate States. The president was the chief executive of the federal government and commander-in-chief of the Confederate A ...

from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

and the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

as a member of the Democratic Party before the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. He was the United States Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the President of the United States, U.S. president's United States Cabinet, Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's Presidency of George Washington, administration. A similar position, called either "Sec ...

from 1853 to 1857.

Davis, the youngest of ten children, was born in Fairview, Kentucky

Fairview is a small census-designated place on the boundary between Christian and Todd counties in the western part of the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 258, down from the 2010 census total of 286, with 186 l ...

, but spent most of his childhood in Wilkinson County, Mississippi

Wilkinson County is a county located in the southwest corner of the U.S. state of Mississippi. As of 2020, its population was 8,587. Its county seat is Woodville. Bordered by the Mississippi River on the west, the county is named for James Wil ...

. His eldest brother Joseph Emory Davis

Joseph Emory Davis (10 December 1784 – 18 September 1870) was an American lawyer who became one of the wealthiest planters in Mississippi in the antebellum era; he owned thousands of acres of land and was among the nine men in Mississippi who o ...

secured the younger Davis's appointment to the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

. Upon graduating, he served six years as a lieutenant in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

. After leaving the army in 1835, Davis married Sarah Knox Taylor

Sarah Knox Davis ( Taylor; March 6, 1814 – September 15, 1835) was the daughter of the 12th U.S. president Zachary Taylor and part of the notable Lee family. She met future Confederate president Jefferson Davis (1808–1889) when living with ...

, daughter of general and future President Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military officer and politician who was the 12th president of the United States, serving from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States ...

. Sarah died from malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

three months after the wedding. Davis became a cotton planter, building Brierfield Plantation in Mississippi on his brother Joseph's land and eventually owning as many as 113 slaves.

In 1845, Davis married Varina Howell

Varina Anne Banks Davis ( Howell; May 7, 1826 – October 16, 1906) was the only First Lady of the Confederate States of America, and the longtime second wife of President Jefferson Davis. She moved to the presidential mansion in Richmond, ...

. During the same year, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives, serving for one year. From 1846 to 1847, he fought in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

as the colonel of a volunteer regiment. He was appointed to the United States Senate in 1847, resigning to unsuccessfully run as governor of Mississippi. In 1853, President Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. A northern Democratic Party (United States), Democrat who believed that the Abolitionism in the United States, abolitio ...

appointed him Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

. After Pierce's administration ended in 1857, Davis returned to the Senate. He resigned in 1861 when Mississippi seceded

Secession is the formal withdrawal of a group from a political entity. The process begins once a group proclaims an act of secession (such as a declaration of independence). A secession attempt might be violent or peaceful, but the goal is the c ...

from the United States.

During the Civil War, Davis guided the Confederacy's policies and served as its commander in chief. When the Confederacy was defeated in 1865, Davis was captured, arrested for alleged complicity in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln

On April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, was shot by John Wilkes Booth while attending the play '' Our American Cousin'' at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C. Shot in the head as he watched the play, L ...

, accused of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

, and imprisoned at Fort Monroe

Fort Monroe is a former military installation in Hampton, Virginia, at Old Point Comfort, the southern tip of the Virginia Peninsula, United States. It is currently managed by partnership between the Fort Monroe Authority for the Commonwealth o ...

. He was released without trial after two years. Immediately after the war, Davis was often blamed for the Confederacy's defeat, but after his release from prison, the Lost Cause of the Confederacy

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy, known simply as the Lost Cause, is an American pseudohistory, pseudohistorical and historical negationist myth that argues the cause of the Confederate States of America, Confederate States during the America ...

movement considered him to be a hero. In the late 19th and the 20th centuries, his legacy as Confederate leader was celebrated in the South. In the twenty-first century, his leadership of the Confederacy has been seen as constituting treason, and he has been frequently criticized as a supporter of slavery and racism. Many of the memorials dedicated to him throughout the United States have been removed.

Early life

Birth and family background

Jefferson F. Davis was the youngest of ten children of Jane and Samuel Emory Davis. Samuel Davis's father, Evan, who had aWelsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, of or about Wales

* Welsh language, spoken in Wales

* Welsh people, an ethnic group native to Wales

Places

* Welsh, Arkansas, U.S.

* Welsh, Louisiana, U.S.

* Welsh, Ohio, U.S.

* Welsh Basin, during t ...

background, came to the colony of Georgia

The Province of Georgia (also Georgia Colony) was one of the Southern Colonies in colonial-era British America. In 1775 it was the last of the Thirteen Colonies to support the American Revolution.

The original land grant of the Province of Ge ...

from Philadelphia. Samuel served in the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies representing the Thirteen Colonies and later the United States during the American Revolutionary War. It was formed on June 14, 1775, by a resolution passed by the Second Continental Co ...

during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, and received a land grant for his service near present-day Washington, Georgia

Washington is the county seat of Wilkes County, Georgia, United States. Under its original name, Heard's Fort, it was for a brief time during the American Revolutionary War the Georgia state capital. It is noteworthy as the place where the Co ...

. He married Jane Cook, a woman of Scots-Irish descent whom he had met in South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

during his military service, in 1783. Around 1793, Samuel and Jane moved to Kentucky. Jefferson was born on June 3, 1808, at the family homestead in Davisburg, a village Samuel had established that later became Fairview, Kentucky

Fairview is a small census-designated place on the boundary between Christian and Todd counties in the western part of the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 258, down from the 2010 census total of 286, with 186 l ...

. He was named after then-President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

.

Early education

In 1810, the Davis family moved toBayou Teche

Bayou Teche (Louisiana French: ''Bayou Têche'') is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 20, 2011 waterway in south central Louisiana in the United States. Bayou Teche ...

, Louisiana. Less than a year later, they moved to a farm near Woodville, Mississippi

Woodville is one of the oldest towns in Mississippi and is the county seat of Wilkinson County, Mississippi, United States. Its population as of 2020 was 928.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of ...

, where Samuel cultivated cotton, acquired twelve slaves, and built a house that Jane called Rosemont Rosemont may refer to:

People

Rosemont is a surname. Notable people with this surname include:

* David A. Rosemont, American television producer

* Franklin Rosemont (1943–2009), American poet, artist, historian

* Norman Rosemont (1924–2018), ...

. During the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

, three of Davis's brothers served in the military. When Davis was around five, he received a rudimentary education at a small schoolhouse near Woodville. When he was about eight, his father sent him with Major Thomas Hinds

Thomas Hinds (January 9, 1780August 23, 1840) was an American soldier, and politician from the state of Mississippi, who served in the United States Congress from 1828 to 1831. Database at

A hero of the War of 1812, Hinds is best known today as ...

and his relatives to attend Saint Thomas College, a Catholic preparatory school run by Dominicans

Dominicans () also known as Quisqueyans () are an ethnic group, ethno-nationality, national people, a people of shared ancestry and culture, who have ancestral roots in the Dominican Republic.

The Dominican ethnic group was born out of a fusio ...

near Springfield, Kentucky

Springfield is a home rule-class city in and the county seat of Washington County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 2,846 at the 2020 census.

History

Springfield was established in 1793 and probably named for springs in the area. ...

. In 1818, Davis returned to Mississippi, where he briefly studied at Jefferson College in Washington

Washington most commonly refers to:

* George Washington (1732–1799), the first president of the United States

* Washington (state), a state in the Pacific Northwest of the United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A ...

. He then attended the Wilkinson County Academy near Woodville for five years. In 1823, Davis attended Transylvania University

Transylvania University is a private university in Lexington, Kentucky, United States. It was founded in 1780 and is the oldest university in Kentucky. It offers 46 major programs, as well as dual-degree engineering programs, and is Higher educ ...

in Lexington. While he was still in college in 1824, he learned that his father Samuel had died. Before his death, Samuel had fallen into debt and sold Rosemont and most of his slaves to his eldest son Joseph Emory Davis

Joseph Emory Davis (10 December 1784 – 18 September 1870) was an American lawyer who became one of the wealthiest planters in Mississippi in the antebellum era; he owned thousands of acres of land and was among the nine men in Mississippi who o ...

, who already owned a large estate in Davis Bend, Mississippi

Davis Bend, Mississippi (now known as Davis Island (Mississippi), Davis Island), also known as Hurricane Island Bend, was a peninsula named after planter Joseph Emory Davis, who owned most of the property. There he established the 5,000-acre Hurr ...

, about south of Vicksburg, Mississippi

Vicksburg is a historic city in Warren County, Mississippi, United States. It is the county seat. The population was 21,573 at the 2020 census. Located on a high bluff on the east bank of the Mississippi River across from Louisiana, Vicksburg ...

. Joseph, who was 23 years older than Davis, informally became his surrogate father.

West Point and early military career

His older brother Joseph got Davis appointed to theUnited States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

at West Point in 1824, where he became friends with classmates Albert Sidney Johnston

General officer, General Albert Sidney Johnston (February 2, 1803 – April 6, 1862) was an American military officer who served as a general officer in three different armies: the Texian Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States ...

and Leonidas Polk

Lieutenant-General Leonidas Polk (April 10, 1806 – June 14, 1864) was a Confederate general, a bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Louisiana and founder of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America, which separat ...

. Davis frequently challenged the academy's discipline. In his first year, he was court-martialed for drinking at a nearby tavern. He was found guilty but was pardoned. The following year, he was placed under house arrest for his role in the Eggnog riot during Christmas 1826 but was not dismissed. He graduated 23rd in a class of 33.

Second Lieutenant Davis was assigned to the 1st Infantry Regiment. He was accompanied by his personal servant James Pemberton, an enslaved African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

whom he inherited from his father. In early 1829, he was stationed at Forts Crawford and Winnebago Winnebago can refer to:

* The exonym of the Ho-Chunk tribe of Native North Americans with reservations in Nebraska, Iowa, and Wisconsin

** Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska, a federally recognized tribe group in the state

** The Winnebago language of the ...

in Michigan Territory

The Territory of Michigan was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from June 30, 1805, until January 26, 1837, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Michigan. Detroit ...

under the command of Colonel Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military officer and politician who was the 12th president of the United States, serving from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States ...

, who later became president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

.

Throughout his life, Davis regularly suffered from ill health. During the northern winters, he had pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

, colds, and bronchitis

Bronchitis is inflammation of the bronchi (large and medium-sized airways) in the lungs that causes coughing. Bronchitis usually begins as an infection in the nose, ears, throat, or sinuses. The infection then makes its way down to the bronchi. ...

. He went to Mississippi on furlough in March 1832, missing the outbreak of the Black Hawk War

The Black Hawk War was a conflict between the United States and Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans led by Black Hawk (Sauk leader), Black Hawk, a Sauk people, Sauk leader. The war erupted after Black Hawk and a group of ...

, and returned to duty just before the Battle of Bad Axe

The Bad Axe Massacre was a massacre of Sauk (Sac) and Meskwaki (Fox) people by United States Army regulars and militia that occurred on August 1–2, 1832. This final scene of the Black Hawk War took place near present-day Victory, Wisconsin, i ...

, which ended the war. When Black Hawk was captured, Davis escorted him for detention in St. Louis. Black Hawk stated that Davis treated him with kindness.

After Davis's return to Fort Crawford in January 1833, he and Taylor's daughter, Sarah, became romantically involved. Davis asked Taylor if he could marry Sarah, but Taylor refused. In spring, Taylor had him assigned to the United States Regiment of Dragoons under Colonel Henry Dodge

Moses Henry Dodge (October 12, 1782 – June 19, 1867) was an American politician and military officer who was Democratic member to the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate, Territorial Governor of Wisconsin and a veteran of the Bla ...

. He was promoted to first lieutenant and deployed at Fort Gibson

Fort Gibson is a historic military site next to the modern city of Fort Gibson, in Muskogee County Oklahoma. It guarded the American frontier in Indian Territory from 1824 to 1888. When it was constructed, the fort was farther west than any ot ...

in Arkansas Territory

The Arkansas Territory was a organized incorporated territory of the United States, territory of the United States from July 4, 1819, to June 15, 1836, when the final extent of Arkansas Territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the ...

. In February 1835, Davis was court-martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

ed for insubordination. He was acquitted. He requested a furlough, and immediately after it ended, he tendered his resignation, which was effective on June 30.

Planting career and first marriage

Davis decided to become a cotton planter. He returned to Mississippi where his brother Joseph had developed Davis Bend into

Davis decided to become a cotton planter. He returned to Mississippi where his brother Joseph had developed Davis Bend into Hurricane Plantation

Hurricane Plantation was a plantation house located near Vicksburg, Mississippi, was the home of Joseph Emory Davis (1784–1870), the oldest brother of Jefferson Davis. Located on a peninsula of the Mississippi River in Warren County, Mississi ...

, which eventually had of cultivated fields with over 300 slaves. Joseph loaned him funds to buy ten slaves and provided him with , though Joseph retained the title to the property. Davis named his section Brierfield Plantation.

Davis continued his correspondence with Sarah, and they agreed to marry with Taylor giving his reluctant assent. They married at Beechland on June 17, 1835. In August, he and Sarah traveled to Locust Grove Plantation, his sister Anna Smith's home in West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana

West Feliciana Parish (French: ''Paroisse de Feliciana Ouest''; Spanish: ''Parroquia de Feliciana Occidental'') is a civil parish located in the U.S. state of Louisiana. At the 2020 census, the population was 15,310. The parish seat is St. F ...

. Within days, both became severely ill with malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

. Sarah died at the age of 21 on September 15, 1835, after only three months of marriage.

For several years after Sarah's death, Davis spent much of his time developing Brierfield. In 1836, he possessed 23 slaves; by 1840, he possessed 40; and by 1860, 113. He made his first slave, James Pemberton, Brierfield's effective overseer, a position Pemberton held until his death around 1850. Davis continued his intellectual development by reading about politics, law and economics at the large library Joseph and his wife, Eliza

ELIZA is an early natural language processing computer program developed from 1964 to 1967 at MIT by Joseph Weizenbaum. Created to explore communication between humans and machines, ELIZA simulated conversation by using a pattern matching and ...

, maintained at Hurricane Plantation. Around this time, Davis became increasingly engaged in politics, benefiting from his brother's mentorship and political influence.

Early political career and second marriage

Davis became publicly involved in politics in 1840 when he attended a Democratic Party meeting in Vicksburg and served as a delegate to the party's state convention inJackson

Jackson may refer to:

Places Australia

* Jackson, Queensland, a town in the Maranoa Region

* Jackson North, Queensland, a locality in the Maranoa Region

* Jackson South, Queensland, a locality in the Maranoa Region

* Jackson oil field in Durham, ...

; he served again in 1842. One week before the state election in November 1843, he was chosen to be the Democratic candidate for the Mississippi House of Representatives for Warren County when the original candidate withdrew his nomination, though Davis lost the election.

In early 1844, Davis was chosen to serve as a delegate to the state convention again. On his way to Jackson, he met Varina Banks Howell, the 18-year-old daughter of William Burr Howell and Margaret Kempe Howell

Margaret Louisa Kempe Howell (January 6, 1806 – November 24, 1867) was an American heiress, planter, and slaveowner who was the mother of Confederate States of America, Confederate First Lady Varina Davis and mother-in-law of Confederate Preside ...

, when he delivered an invitation from Joseph for her to visit the Hurricane Plantation for the Christmas season. At the convention, Davis was selected as one of Mississippi's six presidential electors

In the United States, the Electoral College is the group of presidential electors that is formed every four years for the sole purpose of voting for the president and vice president in the presidential election. This process is described in ...

for the 1844 presidential election.

Within a month of their meeting, 35-year-old Davis and Varina became engaged despite her parents' initial concerns about his age and politics. During the remainder of the year, Davis campaigned for the Democratic party, advocating for the nomination of John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun (; March 18, 1782March 31, 1850) was an American statesman and political theorist who served as the seventh vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832. Born in South Carolina, he adamantly defended American s ...

. He preferred Calhoun because he championed Southern interests including the annexation of Texas

The Republic of Texas was annexed into the United States and admitted to the Union as the 28th state on December 29, 1845.

The Republic of Texas declared independence from the Republic of Mexico on March 2, 1836. It applied for annexatio ...

, reduction of tariffs, and building naval defenses in southern ports. When the party chose James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (; November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. A protégé of Andrew Jackson and a member of the Democratic Party, he was an advocate of Jacksonian democracy and ...

for their presidential candidate, Davis campaigned for him.

Davis and Varina married on February 26, 1845. They had six children: Samuel Emory, born in 1852, who died of an undiagnosed disease two years later; Margaret Howell, born in 1855, who married, raised a family and lived to be 54; Jefferson Davis Jr., born in 1857, who died of yellow fever at age 21; Joseph Evan, born 1859, who died from an accidental fall at age five; William Howell, born 1861, who died of diphtheria

Diphtheria is an infection caused by the bacteria, bacterium ''Corynebacterium diphtheriae''. Most infections are asymptomatic or have a mild Course (medicine), clinical course, but in some outbreaks, the mortality rate approaches 10%. Signs a ...

at age 10; and Varina Anne, born 1864, who remained single and lived to be 34.

In July 1845, Davis became a candidate for the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

. He ran on a platform emphasizing a strict constructionist view of the constitution, states' rights

In United States, American politics of the United States, political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments of the United States, state governments rather than the federal government of the United States, ...

, tariff reductions, and opposition to a national bank. He won the election and entered the 29th Congress. Davis opposed using federal monies for internal improvements, which he believed would undermine the autonomy of the states. He supported the American annexation of Oregon, but through peaceful compromise with Britain. On May 11, 1846, he voted for war with Mexico.

Mexican–American War

At the beginning of the

At the beginning of the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

, Mississippi raised a volunteer unit, the First Mississippi Regiment, for the U.S. Army. Davis expressed his interest in joining the regiment if he was elected its colonel, and in the second round of elections in June 1846 he was chosen. He did not give up his position as a U.S. Representative, but left a letter of resignation with his brother Joseph to submit when he thought it was appropriate.

Davis was able to get his regiment armed with new percussion rifles instead of the smoothbore

A smoothbore weapon is one that has a barrel without rifling. Smoothbores range from handheld firearms to powerful tank guns and large artillery mortars. Some examples of smoothbore weapons are muskets, blunderbusses, and flintlock pistols. ...

muskets used by other units. President Polk

James Knox Polk (; November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. A protégé of Andrew Jackson and a member of the Democratic Party, he was an advocate of Jacksonian democracy and ...

approved their purchase as a political favor in return for Davis marshalling enough votes to pass the Walker Tariff. Because of its association with the regiment, the weapon became known as the " Mississippi rifle", and the regiment became known as the " Mississippi Rifles".

Davis's regiment was assigned to the army of his former father-in-law, Zachary Taylor, in northeastern Mexico. Davis distinguished himself at the Battle of Monterrey

In the Battle of Monterrey (September 21–24, 1846) during the Mexican–American War, General Pedro de Ampudia and the Mexican Army of the North was defeated by the Army of Occupation, a force of United States Regulars, Volunteers, an ...

in September by leading a charge that took the fort of La Teneria. He then went on a two-month leave and returned to Mississippi, where he learned that Joseph had submitted Davis's resignation from the House of Representatives in October. Davis returned to Mexico and fought in the Battle of Buena Vista

The Battle of Buena Vista (February 22–23, 1847), known as the Battle of La Angostura in Mexico, and sometimes as Battle of Buena Vista/La Angostura, was a battle of the Mexican–American War. It was fought between U.S. forces, largely vol ...

on February 22, 1847. He was wounded in the heel during the fighting, but his actions stopped an attack by the Mexican forces that threatened to collapse the American line. In May, Polk offered him a federal commission as a brigadier general. Davis declined the appointment, arguing he could not directly command militia units because the U.S. Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally including seven articles, the Constituti ...

gives the power of appointing militia officers to the states, not the federal government. Instead, he accepted an appointment by Mississippi governor Albert G. Brown

Albert Gallatin Brown (May 31, 1813June 12, 1880) was Governor of Mississippi from 1844 to 1848 and a United States Democratic Party, Democratic United States Senator from Mississippi from 1854 to 1861, when he withdrew during secession.

Early ...

to fill a vacancy in the U.S. Senate left when Jesse Speight

Jesse Speight (September 22, 1795May 1, 1847) was a North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atl ...

died.

Senator and Secretary of War

Senator

Davis took his seat in December 1847 and was made a regent of the

Davis took his seat in December 1847 and was made a regent of the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

. The Mississippi state legislature

The Mississippi Legislature is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Mississippi. The bicameral Legislature is composed of the lower Mississippi House of Representatives, with 122 members, and the upper Mississippi State Senate, with 52 me ...

confirmed his appointment as senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or Legislative chamber, chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the Ancient Rome, ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior ...

in January 1848. He quickly established himself as an advocate of expanding slavery into the Western territories. He argued that because the territories were the common property of all the United States and lacked state sovereignty to ban slavery, slave owners had the equal right to settle them as any other citizens. Davis tried to amend the Oregon Bill to allow settlers to bring their slaves into Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the Oreg ...

. He opposed ratifying the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo officially ended the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). It was signed on 2 February 1848 in the town of Villa de Guadalupe, Mexico City, Guadalupe Hidalgo.

After the defeat of its army and the fall of the cap ...

, which ended the Mexican–American War, claiming that Nicholas Trist

Nicholas Philip Trist (June 2, 1800 – February 11, 1874) was an American lawyer, diplomat, planter, and businessman. Even though he had been dismissed by President James K. Polk as the negotiator with the Mexican government, he negotiated the T ...

, who negotiated the treaty, had done so as a private citizen and not a government representative. Instead, he advocated negotiating a new treaty ceding additional land to the United States, and opposed the application of the Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful 1846 proposal in the United States Congress to ban slavery in territory acquired from Mexico in the Mexican–American War. The conflict over the Wilmot Proviso was one of the major events leading to the ...

to the treaty, which would have banned slavery in any territory acquired from Mexico.

During the 1848 presidential election, Davis chose not to campaign against Zachary Taylor, who was the Whig candidate. After the Senate session following Taylor's inauguration ended in March 1849, Davis returned to Brierfield Plantation. He was reelected by the state legislature for another six-year term in the Senate. Around this time, he was approached by the Venezuelan adventurer Narciso López

Narciso López de Urriola (November 2, 1797 – September 1, 1851) was a Venezuelan-born adventurer and Spanish Army general who is best known for his expeditions aimed at liberating Cuba from Spanish rule in the 1850s. His troops carried a flag ...

to lead a filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent a decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking ...

expedition to liberate Cuba from Spain. He turned down the offer, saying it was inconsistent with his duty as a senator.

When Calhoun died in the spring of 1850, Davis became the senatorial spokesperson for the South. The Congress debated Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

's resolutions, which sought to address the sectional and territorial problems of the nation and became the basis for the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

. Davis was against the resolutions because he felt they would put the South at a political disadvantage. He opposed the admission of California as a free state without its first becoming a territory, asserting that a territorial government would give slaveowners the opportunity to colonize the region. He also tried to extend the Missouri Compromise Line

Missouri (''see pronunciation'') is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it borders Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas to the south and Oklahoma, Kansas, a ...

to allow slavery to expand to the Pacific Ocean. He stated that not allowing slavery into the new territories denied the political equality of Southerners, and threatened to undermine the balance of power between Northern and Southern states in the Senate.

In the autumn of 1851, Davis was nominated to run for governor of Mississippi against Henry Stuart Foote, who had favored the Compromise of 1850. He accepted the nomination and resigned from the Senate, but Foote won the election by a slim margin. Davis turned down a reappointment to his Senate seat by outgoing Governor James Whitfield, settling in Brierfield for the next fifteen months. He remained politically active, attending the Democratic convention in January 1852 and campaigning for Democratic candidates Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. A northern Democratic Party (United States), Democrat who believed that the Abolitionism in the United States, abolitio ...

and William R. King during the presidential election of 1852.

Secretary of War

In March 1853, President Franklin Pierce named Davis his

In March 1853, President Franklin Pierce named Davis his Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

. He championed a transcontinental railroad

A transcontinental railroad or transcontinental railway is contiguous rail transport, railroad trackage that crosses a continent, continental land mass and has terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks may be via the Ra ...

to the Pacific Ocean, arguing it was needed for national defense, and was entrusted with overseeing the Pacific Railroad Surveys

The Pacific Railroad Surveys (1853–1855) were a series of explorations of the American West designed to find and document possible routes for a transcontinental railroad across North America. The expeditions included surveyors, scientists, and a ...

to determine which of four possible routes was the best. He promoted the Gadsden Purchase

The Gadsden Purchase ( "La Mesilla sale") is a region of present-day southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico that the United States acquired from Mexico by the Treaty of Mesilla, which took effect on June 8, 1854. The purchase included lan ...

of today's southern Arizona

Arizona is a U.S. state, state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States, sharing the Four Corners region of the western United States with Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. It also borders Nevada to the nort ...

from Mexico, partly because he preferred a southern route for the new railroad. The Pierce administration agreed and the land was purchased in December 1853. He presented the surveys' findings in 1855, but they failed to clarify the best route and sectional problems prevented any choice being made. Davis also argued for the acquisition of Cuba from Spain, seeing it as an opportunity to add the island, a strategic military location and potential slave state. He suggested that the size of the regular army was too small and that its salaries were too meagre. Congress agreed and authorized four new regiments and increased its pay scale. He ended the manufacture of smoothbore muskets and shifted production to rifles, working to develop the tactics that accompany them. He oversaw the building of public works in Washington D.C., including the initial construction of the Washington Aqueduct

The Washington Aqueduct is an Aqueduct (water supply), aqueduct that provides the public water supply system serving Washington, D.C., and parts of its suburbs, using water from the Potomac River. One of the first major aqueduct projects in the ...

.

Davis assisted in the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 by allowing President Pierce to endorse it before it came up for a vote. This bill, which created Kansas

Kansas ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the west. Kansas is named a ...

and Nebraska

Nebraska ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Ka ...

territories, repealed the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise (also known as the Compromise of 1820) was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand ...

's limits on slavery and left the decision about a territory's slaveholding status to popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the leaders of a state and its government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associativ ...

, which allowed the territory's residents to decide. The passage of this bill led to the demise of the Whig party, which had tried to limit expansion of slavery in the territories. It also contributed to the rise of the Republican Party and the increase of civil violence in Kansas.

The Democratic nomination for the 1856 presidential election went to James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

. Knowing his term was over when the Pierce administration ended in 1857, Davis ran for the Senate once more and re-entered it on March 4, 1857. In the same month, the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

decided the Dred Scott case, which ruled that slavery could not be barred from any territory.

Return to Senate

The Senate recessed in March and did not reconvene until November 1857. The session opened with a debate on theLecompton Constitution

The Lecompton Constitution (1858) was the second of four proposed state constitutions of Kansas. Named for the city of Lecompton, Kansas where it was drafted, it was strongly pro-slavery. It never went into effect.

History Purpose

The Lecompton ...

submitted by a convention in Kansas Territory. If approved, it would have allowed Kansas to be admitted as a slave state. Davis supported it, but it was not accepted, in part because the leading Democrat in the North, Stephen Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas ( né Douglass; April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. As a U.S. senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party to run for president in the 1860 ...

, argued it did not represent the true will of the settlers in the territory. The controversy undermined the alliance between Northern and Southern Democrats.

Davis's participation in the Senate was interrupted in early 1858 by a recurring case of iritis

Uveitis () is inflammation of the uvea, the pigmented layer of the eye between the inner retina and the outer fibrous layer composed of the sclera and cornea. The uvea consists of the middle layer of pigmented vascular structures of the eye and i ...

, which threatened the loss of his left eye. It left him bedridden for seven weeks. He spent the summer of 1858 in Portland, Maine

Portland is the List of municipalities in Maine, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maine and the county seat, seat of Cumberland County, Maine, Cumberland County. Portland's population was 68,408 at the 2020 census. The Portland metropolit ...

recovering, and gave speeches in Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

, Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, and New York, emphasizing the common heritage of all Americans and the importance of the constitution for defining the nation. His speeches angered some states' rights supporters in the South, requiring him to clarify his comments when he returned to Mississippi. Davis said that he appreciated the benefits of Union, but acknowledged that it could be dissolved if states' rights were violated or one section of the country imposed its will on another. Speaking to the Mississippi Legislature on November 16, 1858, Davis stated "if an Abolitionist be chosen President of the United States... I should deem it your duty to provide for your safety outside of a Union with those who have already shown the will...to deprive you of your birthright and to reduce you to worse than the colonial dependence of your fathers."

In February 1860, Davis presented a series of resolutions defining the relationship between the states under the constitution, including the assertion that Americans had a constitutional right to bring slaves into territories. These resolutions were seen as setting the agenda for the Democratic Party nomination, ensuring that Douglas's idea of popular sovereignty, known as the Freeport Doctrine

The Freeport Doctrine was articulated by Stephen A. Douglas on August 27, 1858, in Freeport, Illinois, at the second of the Lincoln-Douglas debates. Former one-term U.S. Representative Abraham Lincoln was campaigning to take Douglas's U.S. Senate ...

, would be excluded from the party platform. The Democratic party split—Douglas was nominated by the North and Vice President John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge (January 16, 1821 – May 17, 1875) was an American politician who served as the 14th vice president of the United States, with President James Buchanan, from 1857 to 1861. Assuming office at the age of 36, Breckinrid ...

was nominated by the South—and the Republican Party nominee Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

won the 1860 presidential election

United States presidential election, Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 6, 1860. The History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party ticket of Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin emerged victoriou ...

. Davis counselled moderation after the election, but South Carolina adopted an ordinance of secession on December 20, 1860. Mississippi seceded on January 9, 1861, though Davis stayed in Washington until he received official notification on January 21. Calling it "the saddest day of my life", he delivered a farewell address, resigned from the Senate, and returned to Mississippi.

President of the Confederate States

Inauguration

Before his resignation, Davis had sent a telegraph to Mississippi Governor

Before his resignation, Davis had sent a telegraph to Mississippi Governor John J. Pettus

John Jones Pettus (October 9, 1813January 25, 1867) was an American politician, lawyer, and slave owner who served as the 23rd Governor of Mississippi, from 1859 to 1863. Before being elected in his own right to full gubernatorial terms in 1859 ...

informing him that he was available to serve the state. On January 27, 1861, Pettus appointed him a major general of Mississippi's army. On February 9, Davis was unanimously elected to the provisional presidency of the Confederacy by a constitutional convention in Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Alabama. Named for Continental Army major general Richard Montgomery, it stands beside the Alabama River on the Gulf Coastal Plain. The population was 2 ...

including delegates from the six states that had seceded: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

, Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

, and Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

. He was chosen because of his political prominence, his military reputation, and his moderate approach to secession, which Confederate leaders thought might persuade undecided Southerners to support their cause. He learned about his election the next day. Davis had been hoping for a military command, but he committed himself fully to his new role. Davis was inaugurated on February 18.

Davis formed his cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filin ...

by choosing a member from each of the states of the Confederacy, including Texas which had recently seceded: Robert Toombs

Robert Augustus Toombs (July 2, 1810 – December 15, 1885) was an American politician from Georgia, who was an important figure in the formation of the Confederacy. From a privileged background as a wealthy planter and slaveholder, Toomb ...

of Georgia for Secretary of State, Christopher Memminger

Christopher Gustavus Memminger (; January 9, 1803 – March 7, 1888) was a German-born American politician and a secessionist who participated in the formation of the Confederate States government. He was the principal author of the Provis ...

of South Carolina for Secretary of the Treasury, LeRoy Walker of Alabama for Secretary of War, John Reagan of Texas for Postmaster General, Judah P. Benjamin of Louisiana for Attorney General, and Stephen Mallory

Stephen Russell Mallory (1812 – November 9, 1873) was an American politician who was a United States Senator from Florida from 1851 to the secession of his home state and the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861. For much of that perio ...

of Florida for Secretary of the Navy. Davis stood in for Mississippi. During his presidency, Davis's cabinet often changed; there were fourteen different appointees for the positions, including six secretaries of war. On November 6, 1861, Davis was elected president for a six-year term. He took office on February 22, 1862.

Civil War

As the Southern states seceded, state authorities took over most federal facilities without bloodshed. But four forts, includingFort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a historical Coastal defense and fortification#Sea forts, sea fort located near Charleston, South Carolina. Constructed on an artificial island at the entrance of Charleston Harbor in 1829, the fort was built in response to the W ...

in Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the List of municipalities in South Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint of South Carolina's coastline on Charleston Harbor, an inlet of the Atla ...

, had not surrendered. Davis preferred to avoid a crisis because the Confederacy needed time to organize its resources. To ensure that no attack on Fort Sumter was launched without his command, Davis had appointed Brigadier General P. G. T. Beauregard

Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard (May 28, 1818 – February 20, 1893) was an American military officer known as being the Confederate general who started the American Civil War at the battle of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Today, he is comm ...

to command all Confederate troops in the vicinity of Charleston, South Carolina. Davis sent a commission to Washington to negotiate the evacuation of the forts, but President of the United States Lincoln refused to meet with it.

When Lincoln informed Davis that he intended to reprovision Fort Sumter, Davis convened with the Confederate Congress on April 8 and gave orders to demand the immediate surrender of the fort or to reduce it. The commander of the fort, Major Robert Anderson, refused to surrender, and Beauregard began the attack on Fort Sumter

The Battle of Fort Sumter (also the Attack on Fort Sumter or the Fall of Fort Sumter) (April 12–13, 1861) was the bombardment of Fort Sumter near Charleston, South Carolina, by the South Carolina militia. It ended with the surrender of the ...

early on April 12. After over thirty hours of bombardment, the fort surrendered. When Lincoln called for 75,000 militiamen to suppress the rebellion, four more states—Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

, Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

, and Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

—joined the Confederacy. The American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

had begun.

1861

In addition to being the constitutional commander-in-chief of the Confederacy, Davis was operational military leader as the military departments reported directly to him. Many people, including GeneralsJoseph E. Johnston

Joseph Eggleston Johnston (February 3, 1807 – March 21, 1891) was an American military officer who served in the United States Army during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) and the Seminole Wars. After Virginia declared secession from ...

and Major General Leonidas Polk, thought he would direct the fighting, but he left that to his generals.

Major fighting in the East began when a Union army advanced into northern Virginia in July 1861. It was defeated at Manassas

Manassas (), formerly Manassas Junction, is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia, United States. The population was 42,772 at the 2020 Census. It is the county seat of Prince William County, although the two are separate jurisdi ...

by two Confederate forces commanded by Beauregard and Joseph Johnston. After the battle, Davis had to manage disputes with the two generals, both of whom felt they did not get the recognition they deserved.

In the West, Davis had to address a problem caused by another general. Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

, which was leaning toward the Confederacy, had declared its neutrality. In September 1861, Polk violated the state's neutrality by occupying Columbus, Kentucky

Columbus is a home rule-class city in Hickman County, Kentucky, in the United States. The population was 140 at the 2020 census, a decline from 229 in 2000. The city lies at the western end of the state, less than a mile from the Mississippi ...

. Secretary of War Walker ordered him to withdraw. Davis initially agreed with Walker, but changed his mind and allowed Polk to remain. The violation led Kentucky to request aid from the Union, effectively losing the state for the Confederacy. Walker resigned as secretary of war and was replaced by Judah P. Benjamin. Davis appointed General Albert Sidney Johnston, as commander of the Western Military Department that included much of Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

, Kentucky, western Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

, and Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

.

1862

In February 1862, the Confederate defenses in the West collapsed when Union forces captured FortsHenry

Henry may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Henry (given name), including lists of people and fictional characters

* Henry (surname)

* Henry, a stage name of François-Louis Henry (1786–1855), French baritone

Arts and entertainmen ...

, Donelson, and nearly half the troops in A. S. Johnston's department. Within weeks, Kentucky, Nashville

Nashville, often known as Music City, is the capital and List of municipalities in Tennessee, most populous city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County in Middle Tennessee, locat ...

and Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Mem ...

were lost, as well as control of the Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

and Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is an area of North West England which was historically a county. The county was bordered by Northumberland to the north-east, County Durham to the east, Westmorland to the south-east, Lancashire to the south, and the Scottish ...

Rivers. The commanders responsible for the defeat were Brigadier Generals Gideon Pillow

Gideon Johnson Pillow (June 8, 1806October 8, 1878) was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army in the Western Theater of the American Civil War, having previously served as a general of United States Volunteers during the Mexican–Ame ...

and John B. Floyd

John Buchanan Floyd (June 1, 1806 – August 26, 1863) was an American politician who served as the List of governors of Virginia, 31st Governor of Virginia. Under president James Buchanan, he also served as the U.S. Secretary of War from 1857 ...

, political general

A political general is a general officer or other military leader without significant military experience who is given a high position in command for political reasons, through Politics, political connections, or to appease certain political bloc ...

s that Davis had been required to appoint. Davis gathered troops defending the Gulf Coast

The Gulf Coast of the United States, also known as the Gulf South or the South Coast, is the coastline along the Southern United States where they meet the Gulf of Mexico. The coastal states that have a shoreline on the Gulf of Mexico are Tex ...

and concentrated them with A. S. Johnston's remaining forces. Davis favored using this concentration in an offensive. Johnston attacked the Union forces at Shiloh in southwestern Tennessee on April 6. The attack failed, and Johnston was killed. General Beauregard took command, falling back to Corinth, Mississippi

Corinth is a city in and the county seat of Alcorn County, Mississippi, Alcorn County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 14,622 at the 2020 census. Its ZIP codes are 38834 and 38835. It lies on the state line with Tennessee.

His ...

, and then to Tupelo, Mississippi

Tupelo ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Lee County, Mississippi, United States. Founded in 1860, the population was 37,923 at the United States Census, 2020, 2020 census. It is the List of municipalities in Mississippi, 7th-most populous ...

. When Beauregard then put himself on leave, Davis replaced him with General Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg (March 22, 1817 – September 27, 1876) was an American army Officer (armed forces), officer during the Second Seminole War and Mexican–American War and Confederate General officers in the Confederate States Army, general in th ...

.

On February 22, Davis was inaugurated as president. In his inaugural speech, he admitted that the South had suffered disasters, but called on the people of the Confederacy to renew their commitment. He replaced Secretary of War Benjamin, who had been scapegoated for the defeats, with George W. Randolph. Davis kept Benjamin in the cabinet, making him secretary of state to replace Hunter, who had stepped down. In March, Davis vetoed a bill to create a commander in chief for the army, but he selected General

On February 22, Davis was inaugurated as president. In his inaugural speech, he admitted that the South had suffered disasters, but called on the people of the Confederacy to renew their commitment. He replaced Secretary of War Benjamin, who had been scapegoated for the defeats, with George W. Randolph. Davis kept Benjamin in the cabinet, making him secretary of state to replace Hunter, who had stepped down. In March, Davis vetoed a bill to create a commander in chief for the army, but he selected General Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

to be his military advisor. They formed a close relationship, and Davis relied on Lee for counsel until the end of the war.

In March, Union troops in the East began an amphibious attack on the Virginia Peninsula

The Virginia Peninsula is the natural landform located in southeast Virginia outlined by the York River, James River, Hampton Roads and Chesapeake Bay. It is sometimes known as the ''Lower Peninsula'' to distinguish it from two other penins ...

, 75 miles from the Confederate capital of Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, a city in the United States

* Richmond, London, a town in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town ...

. Davis and Lee wanted Joseph Johnston, who commanded the Confederate army near Richmond, to make a stand at Yorktown. Instead, Johnston withdrew from the peninsula without informing Davis. Davis reminded Johnston that it was his duty to not let Richmond fall. On May 31, 1862, Johnston engaged the Union army less than ten miles from Richmond at the Battle of Seven Pines

The Battle of Seven Pines, also known as the Battle of Fair Oaks or Fair Oaks Station, took place on May 31 and June 1, 1862, in Henrico County, Virginia as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War.

The Union's Army of the Po ...

, where he was wounded. Davis put Lee in command. Lee began the Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate States Army, Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army ...

less than a month later, pushing the Union forces back down the peninsula and eventually forcing them to withdraw from Virginia. Lee beat back another army moving into Virginia at the Battle of Second Manassas

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederate ...

in August 1862. Knowing Davis desired an offensive into the North, Lee invaded Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

, but retreated back to Virginia after a bloody stalemate at Antietam in September. In December, Lee stopped another invasion of Virginia at the Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat between the Union Army, Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Major general ( ...

.

In the West, Bragg shifted most of his available forces from Tupelo to Chattanooga in July 1862 for an offensive toward Kentucky. Davis approved, suggesting that an attack could win Kentucky for the Confederacy and regain Tennessee, but he did not create a unified command. He formed a new department independent of Bragg under Major General Edmund Kirby Smith

Edmund Kirby Smith (May 16, 1824March 28, 1893) was a General officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate States Army Four-star rank, general, who oversaw the Trans-Mississippi Department (comprising Arkansas, Missouri, Texas, western L ...

at Knoxville, Tennessee

Knoxville is a city in Knox County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. It is located on the Tennessee River and had a population of 190,740 at the 2020 United States census. It is the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Division ...

. In August, both Bragg and Smith invaded Kentucky. Frankfort was briefly captured and a Confederate governor was inaugurated, but the attack collapsed, in part due to lack of coordination between the two generals. After a stalemate at the Battle of Perryville

The Battle of Perryville, also known as the Battle of Chaplin Hills, was fought on October 8, 1862, in the Chaplin Hills west of Perryville, Kentucky, as the culmination of the Confederate Heartland Offensive (Kentucky Campaign) during the Ame ...

, Bragg and Smith retreated to Tennessee. In December, Bragg was defeated at the Battle of Stones River

The Battle of Stones River, also known as the Second Battle of Murfreesboro, was fought from December 31, 1862, to January 2, 1863, in Middle Tennessee, as the culmination of the Stones River Campaign in the Western Theater of the American Ci ...

.

In response to the defeat and the lack of coordination, Davis reorganized the command in the West in November, combining the armies in Tennessee and Vicksburg into a department under the overall command of Joseph Johnston. Davis expected Johnston to relieve Bragg of his command, but Johnston refused. During this time, Secretary of War Randolph resigned because he felt Davis refused to give him the autonomy to do his job; Davis replaced him with James Seddon

James Alexander Seddon (July 13, 1815 – August 19, 1880) was an American lawyer and politician who served two terms as a Representative in the United States Congress, as a member of the Democratic Party. Seddon was appointed Confederate ...

.

In the winter of 1862, Davis decided to join the Episcopal Church; in May 1863, he was confirmed

In Christian denominations that practice infant baptism, confirmation is seen as the sealing of the covenant created in baptism. Those being confirmed are known as confirmands. The ceremony typically involves laying on of hands.

Catholicis ...

at St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Richmond.

1863

On January 1, Lincoln issued theEmancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the eff ...

. Davis saw this as attempt to destroy the South by inciting its enslaved people to revolt, declaring the proclamation "the most execrable measure recorded in the history of guilty man". He requested a law that Union officers captured in Confederate states be delivered to state authorities and put on trial for inciting slave rebellion. In response, the Congress passed a law that Union officers of United States Colored Troops

United States Colored Troops (USCT) were Union Army regiments during the American Civil War that primarily comprised African Americans, with soldiers from other ethnic groups also serving in USCT units. Established in response to a demand fo ...

could be tried and executed, though none were during the war. The law also stated that captured black soldiers would be turned over to the states they were captured in to be dealt with as the state saw fit.

In May, Lee broke up another invasion of Virginia at the Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the American Civil War (1861–1865), and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville campaign.

Confederate General Robert E. Lee's risky decision to divide h ...

, and countered with an invasion into Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...