The following events occurred in January 1927:

January 1, 1927 (Saturday)

*The

British Broadcasting Corporation

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public broadcasting, public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved in ...

was created by royal charter as a publicly funded company, with 773 employees. The first BBC news bulletin was delivered at on January 3

*The

1927 Rose Bowl

The 1927 Rose Bowl Game was a college football bowl game held on January 1, 1927, in Pasadena, California. The game featured the Alabama Crimson Tide, of the Southern Conference, and Stanford, of the Pacific Coast Conference, now the Pac-12 Confe ...

matched two of the nation's unbeaten and untied

college football

College football is gridiron football that is played by teams of amateur Student athlete, student-athletes at universities and colleges. It was through collegiate competition that gridiron football American football in the United States, firs ...

teams, with the

Stanford Indians (10–0–0) against the

Alabama Crimson Tide

The Alabama Crimson Tide refers to the college athletics in the United States, intercollegiate athletic varsity teams that represent the University of Alabama, located in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, Tuscaloosa. The Crimson Tide teams compete in the Na ...

(9–0–0). Stanford led, 7–0, until the final minute, when Alabama blocked a punt, recovered the ball on the 14, and nullified the victory with a 7–7 tie.

*

Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

became the first state in the U.S. to require car owners to carry liability insurance.

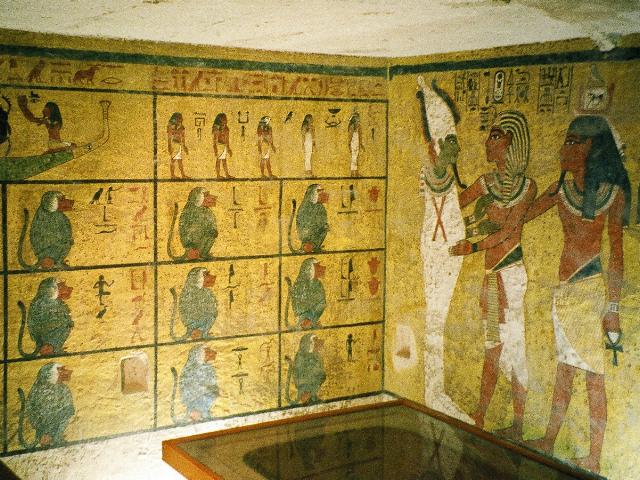

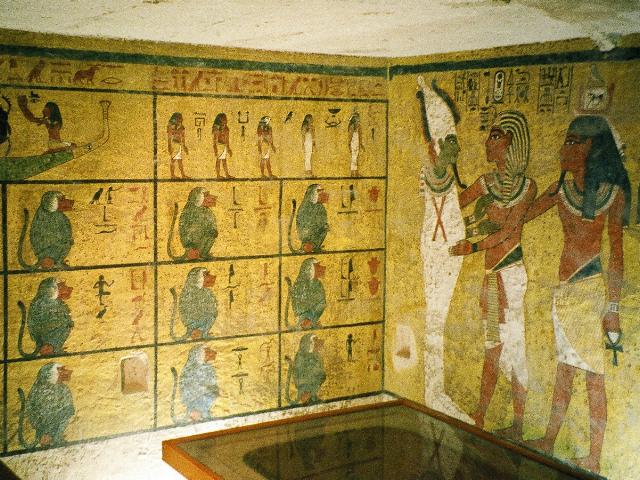

*The tomb of

Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun or Tutankhamen, (; ), was an Egyptian pharaoh who ruled during the late Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt. Born Tutankhaten, he instituted the restoration of the traditional polytheistic form of an ...

was opened for public viewing for the first time since the Egyptian pharaoh's death in 1327 BC.

*

Imperial Chemical Industries

Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) was a British Chemical industry, chemical company. It was, for much of its history, the largest manufacturer in Britain. Its headquarters were at Millbank in London. ICI was listed on the London Stock Exchange ...

was created in Great Britain by the merger of four companies.

*Born:

**

Doak Walker

Ewell Doak Walker II (January 1, 1927 – September 27, 1998) was an American football player who was a halfback and kicker. He played college football for the SMU Mustangs, winning the Maxwell Award in 1947 and the Heisman Trophy in 1948. H ...

, American football player (Detroit Lions 1950–55); in

Dallas

Dallas () is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the List of Texas metropolitan areas, most populous metropolitan area in Texas and the Metropolitan statistical area, fourth-most ...

(d. 1998)

**

Vernon L. Smith

Vernon Lomax Smith (born January 1, 1927) is an American economist who is currently a professor of economics and law at Chapman University. He was formerly the McLellan/Regent's Professor of Economics at the University of Arizona, a professor of ...

, American economist, and 2002 Nobel Prize laureate; in

Wichita, Kansas

Wichita ( ) is the List of cities in Kansas, most populous city in the U.S. state of Kansas and the county seat of Sedgwick County, Kansas, Sedgwick County. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population of the city was 397, ...

January 2, 1927 (Sunday)

*The

Cristero War

The Cristero War (), also known as the Cristero Rebellion or , was a widespread struggle in central and western Mexico from 3 August 1926 to 21 June 1929 in response to the implementation of secularism, secularist and anti-clericalism, anticler ...

began in villages across

Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

in the Los Altos region of the state of

Jalisco

Jalisco, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Jalisco, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. It is located in western Mexico and is bordered by s ...

. The uprising began in protest against anti-clerical laws in Mexico and the rebels called themselves "Cristeros" as fighters for so named because they fought for Christ.

January 3, 1927 (Monday)

*British

concessions in

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, located at

Hankou

Hankou, alternately romanized as Hankow (), was one of the three towns (the other two were Wuchang and Hanyang) merged to become modern-day Wuhan city, the capital of the Hubei province, China. It stands north of the Han and Yangtze Rivers w ...

(Hankow) and

Jiujiang

Jiujiang, formerly transliterated Kiukiang and Kew-Keang, is a prefecture-level city located on the southern shores of the Yangtze River in northwest Jiangxi Province in the People's Republic of China. It is the second-largest prefecture-level ...

(Kiukiang) were invaded by crowds of protesters against British imperialism. A British soldier fired into the crowd at Hankou, killing one protester and wounding dozens of others. Within days, Britain relinquished control of both concessions to the Chinese government, but soon sent troops to protect its concession at

Shanghai

Shanghai, Shanghainese: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: is a direct-administered municipality and the most populous urban area in China. The city is located on the Chinese shoreline on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the ...

.

*A

large annular solar eclipse covered 99.947% of the Sun, creating a dramatic spectacle for observers in only a tiny path, just 2.1 km wide; however, it was fleeting, lasting a very brief 2.62 seconds at the point of maximum eclipse. The path of the eclipse took it over

New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

and

Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

.

*Born:

William Boyett

William Boyett (January 3, 1927 – December 29, 2004) was an American actor best known for his roles in law enforcement dramas on television from the 1950s through the 1990s.

Early years

Boyett was born in Akron, Ohio, the son of Harry Lee and ...

, American character actor known for portraying law enforcement officials, primarily as the co-star, with Martin Milner and Kent McCord as LAPD Sergeant "Mac" MacDonald on all episodes of ''

Adam-12

''Adam-12'' is an American police procedural crime drama television series created by Robert A. Cinader and Jack Webb and produced by Mark VII Limited and Universal Television. The series follows Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) officers Pe ...

''; in

Akron, Ohio

Akron () is a city in Summit County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of municipalities in Ohio, fifth-most populous city in Ohio, with a population of 190,469 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. The Akron metr ...

(d. 2004)

January 4, 1927 (Tuesday)

*

Boris Rtcheouloff filed a patent application for "Means of recording and reproducing pictures, images and the like", the first means for magnetic recording of a television signal onto a moving strip. British patent no. 288,680 was granted in 1928, but the forerunner of

videotape

Videotape is magnetic tape used for storing video and usually Sound recording and reproduction, sound in addition. Information stored can be in the form of either an analog signal, analog or Digital signal (signal processing), digital signal. V ...

was never manufactured.

*Born: Dr.

Thomas Noguchi

is the former chief medical examiner-coroner for Los Angeles County. Popularly known as the "coroner to the stars", Noguchi determined the cause of death in many high-profile cases in Hollywood during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. He performed ...

, Japanese-born American pathologist and

Los Angeles County Coroner

The Los Angeles County Department of Medical Examiner is the medical examiner's office of the government of the Los Angeles County, California, County of Los Angeles, California. It is located at the Boyle Heights, Los Angeles, Boyle Heights nei ...

and Chief Medical Examiner from 1967 to 1982, known for his autopsies on famous people who died in Los Angeles; as Tsunetomi Noguchi in

Fukuoka Prefecture

is a Prefectures of Japan, prefecture of Japan located on the island of Kyūshū. Fukuoka Prefecture has a population of 5,109,323 (1 June 2019) and has a geographic area of 4,986 Square kilometre, km2 (1,925 sq mi). Fukuoka Prefecture borders ...

January 5, 1927 (Wednesday)

*A force of 160 United States Marines was dispatched to

Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

for the purpose of protecting the American embassy in

Managua

Managua () is the capital city, capital and largest city of Nicaragua, and one of the List of largest cities in Central America, largest cities in Central America. Located on the shores of Lake Managua, the city had an estimated population of 1, ...

. The Marines arrived the next day at

Corinto on the

USS ''Galveston''.

*Born:

Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami

Sivaya Subramuniyaswami (born Robert Hansen; January 5, 1927 – November 12, 2001) was an American Hindu religious leader known as Gurudeva by his followers. Subramuniyaswami was born in Oakland, California and adopted Hinduism as a young ma ...

, Hindu guru, author and publisher; as Robert Hansen in

Oakland, California

Oakland is a city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area in the U.S. state of California. It is the county seat and most populous city in Alameda County, California, Alameda County, with a population of 440,646 in 2020. A major We ...

(d. 2001)

January 6, 1927 (Thursday)

*

Robert G. Elliott, the

state electrician for several states, carried out six executions in the electric chair in the same day. In the morning, he put to death Edward Hinlein, John Devereaux and John McGlaughlin in Boston for the 1925 murder of a night watchman. Elliott then caught a train to New York, had dinner, took his family to the movies, and then went up to

Sing Sing

Sing Sing Correctional Facility is a maximum-security prison for men operated by the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision in the village of Ossining (village), New York, Ossining, New York, United States. It is abou ...

, where he carried out the capital punishment for Charles Goldson, Edgar Humes and George Williams for the 1926 murder of another watchman.

January 7, 1927 (Friday)

*At 8:44 am in

New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

and in

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, the first transatlantic

telephone

A telephone, colloquially referred to as a phone, is a telecommunications device that enables two or more users to conduct a conversation when they are too far apart to be easily heard directly. A telephone converts sound, typically and most ...

call was made between the two cities.

Walter S. Gifford of

AT&T

AT&T Inc., an abbreviation for its predecessor's former name, the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, is an American multinational telecommunications holding company headquartered at Whitacre Tower in Downtown Dallas, Texas. It is the w ...

was connected with Sir G. Evelyn V. Murray of the

General Post Office

The General Post Office (GPO) was the state postal system and telecommunications carrier of the United Kingdom until 1969. Established in England in the 17th century, the GPO was a state monopoly covering the dispatch of items from a specific ...

. A half minute later, the two were talking.

*

Philo T. Farnsworth

Philo Taylor Farnsworth (August 19, 1906 – March 11, 1971), "The father of television", was the American inventor and pioneer who was granted the first patent for the television by the United States Government.

Burns, R. W. (1998), ''Televisi ...

, a 20-year-old American inventor, filed his first of many patent applications, for a method of electronically scanning images and transmitting them as a

television

Television (TV) is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. Additionally, the term can refer to a physical television set rather than the medium of transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertising, ...

signal. U.S. Patent No. 1,773,980 was granted on August 26, 1930.

*The

Harlem Globetrotters

The Harlem Globetrotters is an American Exhibition game, exhibition basketball team. They combine athleticism, theater, entertainment, and comedy in their style of play. Over the years, they have played more than 26,000 exhibition games in 124 ...

played their very first road game, against a local team in

Hinckley, Illinois

Hinckley is a village in Squaw Grove Township, DeKalb County, Illinois, United States. The population was 2,006 at the 2020 census, a slight decline from 2,070 at the 2010 census.

History

In the 1830s, a Mr. Hollenbeck, who lived near Ottawa, ...

. Founded by

Abe Saperstein

Abraham Michael Saperstein (; July 4, 1902 – March 15, 1966) was the founder, owner and earliest coach of the Harlem Globetrotters. Saperstein was a leading figure in black basketball and baseball from the 1920s through the 1950s, primarily be ...

, the all African-American team was originally called "Saperstein's New York", before assuming its current name in the 1930s.

*

Shadow Lawn, the

West Long Branch, New Jersey

West Long Branch is a Borough (New Jersey), borough situated within the Jersey Shore region, in Monmouth County, New Jersey, Monmouth County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 United States census, the borough's population was 8,5 ...

, home that had served as the "Summer White House" for

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

from 1916 to 1920, was destroyed by a fire.

January 8, 1927 (Saturday)

*The ''Kate Adams'', last of the

"side-wheeler" steamboats in the United States, was destroyed by fire while at its moorings in

Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Mem ...

,

Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

.

January 9, 1927 (Sunday)

*For the first time in the 368-year history of the ''

Index Librorum Prohibitorum

The (English: ''Index of Forbidden Books'') was a changing list of publications deemed heretical or contrary to morality by the Sacred Congregation of the Index (a former dicastery of the Roman Curia); Catholics were forbidden to print or re ...

'', the Roman Catholic Church's list of prohibited books, a newspaper was banned by papal decree.

Pope Pius XI banned the French royalist daily ''

Action Française

''Action Française'' (, AF; ) is a French far-right monarchist and nationalist political movement. The name was also given to a journal associated with the movement, '' L'Action Française'', sold by its own youth organization, the Camelot ...

'' for articles "written against the Holy See and the supreme pontiff himself".

*

Seventy-eight children were killed in a panic that followed the outbreak of a fire at the Laurier Palace cinema in

Montreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

. Shortly after the 2:00 matinee began, flames were spotted. On three of the theatre's four fire exits, the evacuation was orderly, but on the stairway at the east side of the building, children were trampled five steps away from the door. The dead ranged in age from 4 to 16. Only one of the victims was older than 18.

January 10, 1927 (Monday)

*

Fritz Lang

Friedrich Christian Anton Lang (; December 5, 1890 – August 2, 1976), better known as Fritz Lang (), was an Austrian-born film director, screenwriter, and producer who worked in Germany and later the United States.Obituary ''Variety Obituari ...

's silent science fiction film ''

Metropolis

A metropolis () is a large city or conurbation which is a significant economic, political, and cultural area for a country or region, and an important hub for regional or international connections, commerce, and communications.

A big city b ...

'' had its world premiere at the

Ufa-Palast am Zoo

The Ufa-Palast am Zoo, located near Berlin Zoological Garden in the City West, New West area of Charlottenburg, was a major Berlin cinema owned by Universum Film AG, or Ufa. Opened in 1919 and enlarged in 1925, it was the largest cinema in German ...

in

Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

.

*In a special message to Congress, President Coolidge said that the 15 American warships and 5,000 members of the Navy and the Marines would be dispatched toward

Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

and

Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

to protect American interests. On the same day, the U.S. Department of the Navy announced that 800 U.S. Marines would be sent to

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

for the same purpose, to be transported from

Guam

Guam ( ; ) is an island that is an Territories of the United States, organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. Guam's capital is Hagåtña, Guam, Hagåtña, and the most ...

by the cruiser

USS ''Huron''.

*Born:

**

Gisele MacKenzie

Gisèle MacKenzie (born Gisèle Marie Louise Marguerite LaFlèche; January 10, 1927 – September 5, 2003)

Accessed April 2010 ...

, Canadian-born singer; in

Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Manitoba. It is centred on the confluence of the Red River of the North, Red and Assiniboine River, Assiniboine rivers. , Winnipeg h ...

(d. 2003)

**

Johnnie Ray

John Alvin Ray (January 10, 1927 – February 24, 1990) was an American singer, songwriter, and pianist. Highly popular for most of the 1950s, Ray has been cited by critics as a major precursor to what became rock and roll, for his jazz and blu ...

, American singer; in

Hopewell, Oregon

Hopewell is an unincorporated community in Yamhill County, Oregon, United States. It is at the eastern terminus of Oregon Route 153, south of Dayton and a few miles west of Wheatland, at the east base of the Eola Hills.

Hopewell post office ...

(d. 1990)

**

Otto Stich

Otto Anton Stich (10 January 1927 – 13 September 2012) was a Swiss professor and politician. He served as a member of the Swiss Federal Council from 1984 to 1995 and held the President of the Swiss Confederation, Swiss presidency in 1988 and 199 ...

,

Swiss Federal Council

The Federal Council is the federal cabinet of the Swiss Confederation. Its seven members also serve as the collective head of state and government of Switzerland. Since World War II, the Federal Council is by convention a permanent grand co ...

executive 1983–1995; President, 1988 and 1994 (d. 2012)

January 11, 1927 (Tuesday)

*The American freighter ''John Tracy'', with 27 men on board, foundered and sank off

Cape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer months. The ...

during a winter storm. Wreckage, including the vessel's nameplate, would be recovered ten days later.

*Thirty-six

Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywood ...

celebrities gathered at the

Ambassador Hotel in

Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

and founded the

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS, often pronounced ; also known as simply the Academy or the Motion Picture Academy) is a professional honorary organization in Beverly Hills, California, U.S., with the stated goal of adva ...

, for the purpose of acknowledging cinematic excellence. The academy's awards for motion picture industry would later be nicknamed "The Oscars".

*Died:

Houston Chamberlain, 71, British anti-Semite turned German Nazi. His book ''The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century'' was an inspiration for the Nazi ideology.

January 12, 1927 (Wednesday)

*Major League Baseball Commissioner

Kenesaw Mountain Landis

Kenesaw Mountain Landis (; November 20, 1866 – November 25, 1944) was an American jurist who served as a United States federal judge from 1905 to 1922 and the first Commissioner of Baseball, commissioner of baseball from 1920 until his death. ...

exonerated 21 members of the

Detroit Tigers

The Detroit Tigers are an American professional baseball team based in Detroit. The Tigers compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) American League Central, Central Division. One of the AL's eight chart ...

and the

Chicago White Sox

The Chicago White Sox are an American professional baseball team based in Chicago. The White Sox compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) American League Central, Central Division. The club plays its ...

from accusations of were absolved and conspiring to bring about a Detroit loss in four-game series in 1917.

January 13, 1927 (Thursday)

*At

Tampico

Tampico is a city and port in the southeastern part of the Mexican state of Tamaulipas. It is located on the north bank of the Pánuco River, about inland from the Gulf of Mexico, and directly north of the state of Veracruz. Tampico is the fif ...

,

Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

, the British steamer ''Essex Isles'' exploded while its cargo of gasoline barrels was being unloaded. Thirty-seven men, mostly Mexican dockworkers, died in the accident.

*

Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

became the first European power to renounce any claims to use of territory in

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, and ceded back a concession that had been granted to it at

Tianjin

Tianjin is a direct-administered municipality in North China, northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the National Central City, nine national central cities, with a total population of 13,866,009 inhabitants at the time of the ...

.

*Born:

**

Brock Adams

Brockman Adams (January 13, 1927 – September 10, 2004) was an American lawyer and politician. A Democrat from Washington, Adams served as a U.S. Representative, Senator, and United States Secretary of Transportation. He was forced to retire in ...

, U.S. Congressman for Washington 1965–77, and U.S. Senator 1987–93; in

Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

,

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

(d. 2004)

**

Sydney Brenner

Sydney Brenner (13 January 1927 – 5 April 2019) was a South African biologist. In 2002, he shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with H. Robert Horvitz and Sir John E. Sulston. Brenner made significant contributions to wo ...

, South African biologist, Nobel Prize winner 2002; in

Germiston, Gauteng

Germiston, also known as kwaDukathole, is a city in the East Rand region of Gauteng, South Africa, administratively forming part of the City of Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality since the latter's establishment in 2000. It functions as the ...

(d. 2019)

January 14, 1927 (Friday)

*With four days left in her term,

Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

Governor

Miriam A. Ferguson (known popularly as "Ma Ferguson") halted further grants of clemency to Texas convicts. The lame duck governor had pardoned or commuted the sentences of a record 3,595 persons convicted of crimes, including 1,350 full pardons.

January 15, 1927 (Saturday)

* The English broadcaster and rugby player

Teddy Wakelam

Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Blythe Thornhill Wakelam (8 May 1893 – 10 July 1963), known as Teddy Wakelam, was an English sports broadcaster and rugby union player who captained Harlequin F.C.

Early life

Wakelam was born in Hereford. During his ...

gave the first ever running sports commentary on BBC Radio, a Rugby International match between England and Wales from the Twickenham stadium in Middlesex, which England won by 11 points to 9.

*In a split decision on the appeal of the verdict in the

Scopes Trial, the

Tennessee Supreme Court

The Tennessee Supreme Court is the highest court in the state of Tennessee. The Supreme Court's three buildings are seated in Nashville, Knoxville, and Jackson, Tennessee. The Court is composed of five members: a chief justice, and four justice ...

upheld the constitutionality of Section 49-1922 of the Tennessee Code, which prohibited the teaching of evolution. The Court set aside the order for the fine levied against teacher

John T. Scopes

John Thomas Scopes (August 3, 1900 – October 21, 1970) was a teacher in Dayton, Tennessee, who was charged on May 5, 1925, with violating Tennessee's Butler Act, which prohibited the teaching of human evolution in Tennessee schools. He was trie ...

. Chief Justice

Grafton Green

Grafton Green (August 12, 1872 – January 27, 1947) was an American jurist who served on the Tennessee Supreme Court from 1910 to 1947, including more than 23 years as chief justice.[Newark, California

Newark ( ) is a city in Alameda County, California, United States. It was incorporated as a city in September 1955. Newark is an enclave, surrounded by the city of Fremont. The three cities of Newark, Fremont, and Union City make up the Tri-C ...]

to the city of

Menlo Park

Menlo Park may refer to:

Places

*Menlo Park, New Jersey, a section of Edison, New Jersey, location of Thomas Edison's laboratories

**Menlo Park Mall, a shopping mall in Edison

**Menlo Park Terrace, New Jersey, a section of nearby Woodbridge Townsh ...

opened to traffic, becoming the first auto bridge over San Francisco Bay.

*Born:

Yaakov Heruti, Polish-born Israeli Zionist militant and political activist (d. 2022)

January 16, 1927 (Sunday)

*

George Young

George Young may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* George Young (filmmaker), Australian stage manager and film director in the silent era

* George Young (rock musician) (1946–2017), Australian musician, songwriter, and record producer

* G ...

, a 17-year-old from Toronto, became the first person to swim the between

Catalina Island, California

Santa Catalina Island (; ) often shortened to Catalina Island or Catalina, is a rocky island, part of the Channel Islands (California), Channel Islands, off the coast of Southern California in the Gulf of Santa Catalina. The island covers an ...

, and the mainland. At noon the previous day, 102 competitors dove into the waters for the prize offered by William Wrigley, Jr. Young was the only person to finish the task, arriving at the

Point Vincente Lighthouse at

January 17, 1927 (Monday)

*Movie comedian

Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is considered o ...

was ordered to pay $4,000 a month alimony to his wife,

Lita Grey

Lita Grey (born Lillita Louise MacMurray, April 15, 1908 – December 29, 1995), who was known for most of her life as Lita Grey Chaplin, was an American actress. She was the second wife of Charlie Chaplin, and appeared in his films '' The Kid'' ...

Chaplin, by a Los Angeles court. The same day, the Internal Revenue Service filed a lien against Chaplin for seven years of back taxes and penalties, totalling $1,073,721.47 between 1918 and 1924.

*Born:

Eartha Kitt

Eartha Mae Kitt (née Keith; January 17, 1927 – December 25, 2008) was an American singer and actress. She was known for her highly distinctive singing style and her 1953 recordings of "C'est si bon" and the Christmas novelty song "Santa Baby" ...

, American actress and singer; in

North, South Carolina

North is a town in Orangeburg County, South Carolina, United States. The population was 696 at the 2020 census.

Geography

North is located at (33.615983, -81.103588).

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area o ...

(d. 2008)

*Died:

Juliette Gordon Low

Juliette Gordon Low ( Gordon; October 31, 1860 – January 17, 1927) was the American founder of Girl Scouts of the USA. Inspired by the work of Robert Baden-Powell, founder of Scout Movement, she joined the Girl Guide movement in England, fo ...

, founder of the

Girl Scouts of the USA

Girl Scouts of the United States of America (GSUSA), commonly referred to as Girl Scouts, is a youth organization for girls in the United States and American girls living abroad.

It was founded by Juliette Gordon Low in 1912, a year after she ...

(b. 1860)

January 18, 1927 (Tuesday)

*American ratification of the 1923

Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (, ) is a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–1923 and signed in the Palais de Rumine in Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially resolved the conflict that had initially ...

, and the establishment of diplomatic relations with

Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, failed to get approval in the U.S. Senate. Though favored by a 50–34 margin, a two-thirds majority was needed.

*The

Food, Drug, and Insecticide Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a List of United States federal agencies, federal agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is respo ...

was established as part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

January 19, 1927 (Wednesday)

*The first legislative session held in

The Council House of India (now the Parliament House) was opened with a meeting of the Central Legislative Assembly. The House,

circular buildingcovering nearly six acres, is now part of the Parliament Assembly where the

Lok Sabha

The Lok Sabha, also known as the House of the People, is the lower house of Parliament of India which is Bicameralism, bicameral, where the upper house is Rajya Sabha. Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha, Members of the Lok Sabha are elected by a ...

and the

Rajya Sabha

Rajya Sabha (Council of States) is the upper house of the Parliament of India and functions as the institutional representation of India’s federal units — the states and union territories.https://rajyasabha.nic.in/ It is a key component o ...

convene.

*Died: Empress

Carlota of Mexico

Charlotte of Mexico (; ; 7 June 1840 – 19 January 1927), known by the Spanish version of her name, Carlota, was by birth a princess of Belgium and member of the House of Wettin in the branch of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (as such she was also ...

, 86, Belgian princess whose husband reigned as Emperor

Maximilian I of Mexico from 1864 to 1867.

January 20, 1927 (Thursday)

*

Frank L. Smith, recently selected to serve as a United States Senator from

Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

, was not allowed to take the oath of office. The U.S. Senate voted 48–33 against seating him pending further investigation of the financing of his 1926 primary election campaign.

January 21, 1927 (Friday)

*The

Movietone sound system

The Movietone sound system is an optical sound, optical sound-on-film method of recording sound for motion pictures, ensuring synchronization between sound and picture. It achieves this by recording the sound as a variable-density optical track ...

, developed by

Fox Film Corporation

The Fox Film Corporation (also known as Fox Studios) was an American independent company that produced motion pictures and was formed in 1914 by the theater "chain" pioneer William Fox (producer), William Fox. It was the corporate successor to ...

(later

20th Century Fox

20th Century Studios, Inc., formerly 20th Century Fox, is an American film studio, film production and Film distributor, distribution company owned by the Walt Disney Studios (division), Walt Disney Studios, the film studios division of the ...

) was first demonstrated to the public, at the

Sam H. Harris Theatre

The Sam H. Harris Theatre, originally the Candler Theatre, was a theater within the Candler Building, at 226 West 42nd Street, in the Theater District of Midtown Manhattan in New York City. Opened in 1914, the 1,200-seat theater was designed ...

in New York City. Shown by a movie projector equipped to play

sound-on-film

Sound-on-film is a class of sound film processes where the sound accompanying a picture is recorded on photographic film, usually, but not always, the same strip of film carrying the picture. Sound-on-film processes can either record an Analog s ...

, the one-reel film preceded the feature presentation, ''What Price Glory?''. Though not quite synchronized, the film included the sight and sound of popular singe

Raquel Meller

January 22, 1927 (Saturday)

*The second sports broadcast in the United Kingdom was made by

BBC Radio

BBC Radio is an operational business division and service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) which has operated in the United Kingdom under the terms of a royal charter since 1927. The service provides national radio stations cove ...

, with

Teddy Wakelam

Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Blythe Thornhill Wakelam (8 May 1893 – 10 July 1963), known as Teddy Wakelam, was an English sports broadcaster and rugby union player who captained Harlequin F.C.

Early life

Wakelam was born in Hereford. During his ...

providing the play-by-play of a soccer football game between Arsenal and Sheffield United. Subscribers to ''

Radio Times

''Radio Times'' is a British weekly listings magazine devoted to television and radio programme schedules, with other features such as interviews, film reviews and lifestyle items. Founded in September 1923 by John Reith, then general manage ...

'' could follow the game with a diagram, designed by producer

Lance Sieveking

Lancelot De Giberne Sieveking DFC (19 March 1896 – 6 January 1972) was an English writer and pioneer BBC radio and television producer. He was married three times, and was father to archaeologist Gale Sieveking (1925–2007) and Fortean-writ ...

, that divided the field into eight squares. The game ended in a 1–1 draw.

*The

Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes () is a Detective fiction, fictional detective created by British author Arthur Conan Doyle. Referring to himself as a "Private investigator, consulting detective" in his stories, Holmes is known for his proficiency with obser ...

short story

A short story is a piece of prose fiction. It can typically be read in a single sitting and focuses on a self-contained incident or series of linked incidents, with the intent of evoking a single effect or mood. The short story is one of the old ...

"

The Adventure of the Veiled Lodger

"The Adventure of the Veiled Lodger" (1927), one of the 56 Sherlock Holmes short stories written by British author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, is one of 12 stories in the cycle collected as '' The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes''.

Plot

Holmes is vi ...

" by Sir

Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Hol ...

was published for the first time in ''

Liberty

Liberty is the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one's way of life, behavior, or political views. The concept of liberty can vary depending on perspective and context. In the Constitutional ...

'' magazine in the United States.

*A bus, carrying the

Baylor University

Baylor University is a Private university, private Baptist research university in Waco, Texas, United States. It was chartered in 1845 by the last Congress of the Republic of Texas. Baylor is the oldest continuously operating university in Te ...

basketball team to a scheduled game against the

University of Texas

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public research university in Austin, Texas, United States. Founded in 1883, it is the flagship institution of the University of Texas System. With 53,082 students as of fall 2 ...

, was struck at a railroad crossing near

Round Rock, Texas

Round Rock is a city in Williamson and Travis County, Texas, United States, part of the Greater Austin metropolitan area. Its population is 119,468 according to the 2020 census.

The city straddles the Balcones Escarpment, Texas State Histor ...

. Ten students (including five members of the team) were killed and seven seriously injured.

*The ''Tamanweis'', a war ceremonial for the

Swinomish American Indian tribe, was performed for the first time since it had been outlawed by federal law. The occasion, a celebration at

La Conner, Washington

La Conner is a town in Skagit County, Washington, United States with a population of 965 at the 2020 census. It is included in the Mount Vernon– Anacortes, Washington Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

La Conner was first sett ...

, of the 1855 Mukiliteo peace treaty, also saw a traditional feast and the playing of the game "Fla-Hal".

*The comedy film ''

The Kid Brother

''The Kid Brother'' is a 1927 American silent film, silent comedy film, comedy film starring Harold Lloyd. It was successful and popular upon release and today is considered by critics and fans to be one of Lloyd's best films, integrating e ...

'' starring

Harold Lloyd

Harold Clayton Lloyd Sr. (April 20, 1893 – March 8, 1971) was an American actor, comedian, and stunt performer who appeared in many Silent film, silent comedy films.Obituary ''Variety'', March 10, 1971, page 55.

One of the most influent ...

was released.

January 23, 1927 (Sunday)

*

Ban Johnson

Byron Bancroft "Ban" Johnson (January 5, 1864 – March 28, 1931) was an American executive in professional baseball who served as the founder and first president of the American League (AL).

Johnson developed the AL—a descendant of th ...

, who had been President of baseball's

American League

The American League of Professional Baseball Clubs, known simply as the American League (AL), is the younger of two sports leagues, leagues constituting Major League Baseball (MLB) in the United States and Canada. It developed from the Western L ...

since its founding in 1900, was fired by vote of the league's eight teams. Johnson had publicly criticized the ruling, by baseball commissioner Landis, on the

Black Sox Scandal

The Black Sox Scandal was a match fixing, game-fixing scandal in Major League Baseball (MLB) in which eight members of the Chicago White Sox were accused of intentionally losing the 1919 World Series against the Cincinnati Reds in exchange for p ...

. Eight years remained on his contract, so he retained his title, but his duties were assumed by Frank J. Navin of the

Detroit Tigers

The Detroit Tigers are an American professional baseball team based in Detroit. The Tigers compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) American League Central, Central Division. One of the AL's eight chart ...

.

*

California Attorney General

The attorney general of California is the state attorney general of the government of California. The officer must ensure that "the laws of the state are uniformly and adequately enforced" (Constitution of California, Article V, Section 13). The ...

Ulysses S. Webb rendered an attorney general opinion that dark-skinned

Mexican-Americans

Mexican Americans are Americans of full or partial Mexican descent. In 2022, Mexican Americans comprised 11.2% of the US population and 58.9% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% of Mexican Americans were born in the United State ...

could be classified as "American Indians" under the state's school segregation law.

January 24, 1927 (Monday)

*The United Kingdom dispatched 16,000 servicemen to defend the British concession in

Shanghai

Shanghai, Shanghainese: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: is a direct-administered municipality and the most populous urban area in China. The city is located on the Chinese shoreline on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the ...

. Commanded by Major General John Duncan, the Shanghai Defense Force consisted of 12,000 men from the 13th and 14th British infantry brigades, and the 20th Indian Infantry, to join 3,000 naval ratings and 1,000 marines.

January 25, 1927 (Tuesday)

*At

Oslo

Oslo ( or ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of 1,064,235 in 2022 ...

, the

Storthing voted 112 to 33 to reject a proposal for the complete disarmament of Norway. A bill to reorganize the army and navy was approved as an alternative.

*Amid fears that the Coolidge Administration would lead the United States into war with

Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

, the U.S. Senate voted 79–0 to ask President Coolidge to seek arbitration of disputes over oil rights.

*The merger of the Remington Typewriter Company and Rand-Kardex Bureau, Inc. (created from the merger of two business recordkeeping systems) formed

Remington Rand

Remington Rand, Inc. was an early American business machine manufacturer, originally a typewriter manufacturer and in a later incarnation the manufacturer of the UNIVAC line of mainframe computers. Formed in 1927 following a merger, Remington ...

, which would make the

UNIVAC

UNIVAC (Universal Automatic Computer) was a line of electronic digital stored-program computers starting with the products of the Eckert–Mauchly Computer Corporation. Later the name was applied to a division of the Remington Rand company and ...

, the world's first business computer. Through further mergers, the company became

Sperry Rand

Sperry Corporation was a major American equipment and electronics company whose existence spanned more than seven decades of the 20th century. Sperry ceased to exist in 1986 following a prolonged hostile takeover bid engineered by Burroughs ...

(1955), and

Unisys

Unisys Corporation is a global technology solutions company founded in 1986 and headquartered in Blue Bell, Pennsylvania. The company provides cloud, AI, digital workplace, logistics, and enterprise computing services.

History Founding

Unis ...

(1986).

*

J. Frank Norris

John Franklyn Norris, more commonly known as J. Frank Norris (September 18, 1877 – August 20, 1952) was a Baptist preacher and controversial Christian fundamentalist.

Personal life

J. Frank Norris was born in Dadeville in Tallapoosa County ...

, popular Southern Baptist leader, was acquitted of murder charges arising from the July 17, 1926, death of wholesale lumberman Dexter B. Chipps.

*Born:

Antonio Carlos Jobim

Antonio is a masculine given name of Etruscan origin deriving from the root name Antonius. It is a common name among Romance language–speaking populations as well as the Balkans and Lusophone Africa. It has been among the top 400 most popular ...

, Brazilian composer credited with popularizing the

bossa nova style; in

Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro, or simply Rio, is the capital of the Rio de Janeiro (state), state of Rio de Janeiro. It is the List of cities in Brazil by population, second-most-populous city in Brazil (after São Paulo) and the Largest cities in the America ...

(d. 1994)

January 26, 1927 (Wednesday)

*The American College of Osteopathic Surgeons (ACOS), a non-profit organization to promote

osteopathic medicine in the United States

Osteopathic medicine is a branch of the medical profession in the United States that promotes the practice of science-based medicine, often referred to in this context as allopathic medicine, with a set of philosophy and principles set by its ...

, was incorporated in

Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

.

*In

Bannock County, Idaho

Bannock County is a county in the southeastern part of Idaho. As of the 2020 census, the population was 87,018, making it the sixth-most populous county in Idaho. The county seat and largest city is Pocatello. The county was established in 18 ...

, a basketball game in the town of Turner ended in tragedy when an explosion toppled the walls at the recreation hall of the Mormon chapel. Seven people were killed and 20 others seriously injured. The lights had failed and a person lit a match, triggering a gas explosion.

*Born:

José Azcona del Hoyo

José Simón Azcona del Hoyo (January 26, 1927 – October 24, 2005) was 30th President of Honduras from January 27, 1986 to January 27, 1990 for the Liberal Party of Honduras (PLH). He was born in La Ceiba in Honduras.

Early life and career ...

,

President of Honduras

The president of Honduras (), officially known as the President of the Republic of Honduras (), is the head of state and head of government of Honduras, and the Commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces. According to the 1982 Constitution of H ...

1986–1990; in

La Ceiba

La Ceiba () is a municipality, the capital of the Honduran department of Atlántida (department), Atlántida, and a port city on the northern Caribbean coast in Honduras. It forms part of the southeastern boundary of the Gulf of Honduras. With ...

(d. 2005)

*Died:

Lyman J. Gage

Lyman Judson Gage (June 28, 1836 – January 26, 1927) was an American financier who served as the 42nd United States Secretary of the Treasury in the cabinets of William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt.

Biography Early life

He was born ...

, 91, American financier and former U.S. Secretary of the Treasury

January 27, 1927 (Thursday)

*United Independent Broadcasters, Inc., was incorporated as a network of 16 radio stations. On September 18, 1927, United would be acquired by

William S. Paley

William Samuel Paley (September 28, 1901 – October 26, 1990) was an American businessman, primarily involved in the media, and best known as the chief executive who built the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) from a small radio network into o ...

and renamed the

Columbia Broadcasting System

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS (an abbreviation of its original name, Columbia Broadcasting System), is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainme ...

, providing CBS Radio, and later the CBS Television Network.

*A year after proclaiming himself King of the

Hejaz

Hejaz is a Historical region, historical region of the Arabian Peninsula that includes the majority of the western region of Saudi Arabia, covering the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Saudi Arabia, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif and Al Bahah, Al-B ...

, Arabian sultan

Ibn Saud

Abdulaziz bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud (; 15 January 1875Ibn Saud's birth year has been a source of debate. It is generally accepted as 1876, although a few sources give it as 1880. According to British author Robert Lacey's book ''The Kingdom'', ...

proclaimed himself as King of

Najd

Najd is a Historical region, historical region of the Arabian Peninsula that includes most of the central region of Saudi Arabia. It is roughly bounded by the Hejaz region to the west, the Nafud desert in Al-Jawf Province, al-Jawf to the north, ...

as well. The independence of the Kingdom of Hejaz and Nejd was recognized on May 20, 1927, and renamed as the

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

in 1932.

*

Ty Cobb

Tyrus Raymond Cobb (December 18, 1886 – July 17, 1961), nicknamed "the Georgia Peach", was an American professional baseball center fielder. A native of rural Narrows, Georgia, Cobb played 24 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB). He spent ...

and

Tris Speaker

Tristram Edgar Speaker (April 4, 1888 – December 8, 1958), nicknamed "the Gray Eagle", was an American professional baseball player and manager. He played in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a center fielder from 1907 to 1928. Considered one o ...

, two of the greatest outfielders in American baseball history, were both exonerated of charges of wrongdoing by Commissioner Landis. Both had been accused, by

Dutch Leonard, of conspiracy to throw a game in 1919. Cobb was elected to baseball's Hall of Fame in its first year (1936), and Speaker in its second.

January 28, 1927 (Friday)

*A hurricane swept across the

British Isles

The British Isles are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Outer Hebr ...

, killing twenty people and injuring hundreds. Nineteen of the dead were in Scotland, including eight in

Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

, and another person was killed in Ireland. The storm moved on a line from Land's End in England, to John O'Groats in Scotland.

*Born:

Hiroshi Teshigahara

was a Japanese avant-garde filmmaker and artist from the Japanese New Wave era. He is best known for the 1964 film ''Woman in the Dunes''. He is also known for directing other titles such as '' The Face of Another'' (1966), ''Natsu no Heitai'' ...

, Japanese director; in

Chiyoda (d. 2001)

January 29, 1927 (Saturday)

*In

Schenectady, New York

Schenectady ( ) is a City (New York), city in Schenectady County, New York, United States, of which it is the county seat. As of the United States Census 2020, 2020 census, the city's population of 67,047 made it the state's ninth-most populo ...

, the

General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) was an American Multinational corporation, multinational Conglomerate (company), conglomerate founded in 1892, incorporated in the New York (state), state of New York and headquartered in Boston.

Over the year ...

Company demonstrated its

own sound-on-film process, the first to synchronize recorded sights and sounds on a single strip of film. The product of six years research opened a new era in movies, taking the world from silent films to the "talkies".

*Born:

**

Lewis Urry

Lewis Frederick Urry ( – ) was a Canadian- American chemical engineer and inventor. He invented both the alkaline battery and lithium battery while working for the Eveready Battery company.

Life

Urry was born January 29, 1927, in Pontypool, O ...

, Canadian engineer who invented the

alkaline battery

An alkaline battery (IEC code: L) is a type of primary battery where the electrolyte (most commonly potassium hydroxide) has a pH value above 7. Typically, these batteries derive energy from the reaction between zinc metal and manganese diox ...

and the

lithium battery

Lithium battery may refer to:

* Lithium metal battery, a non-rechargeable battery with lithium as an anode

** Lithium–air battery

** Lithium–iron disulfide battery

** Lithium–sulfur battery

** Nickel–lithium battery

** Rechargeable li ...

; in

Pontypool, Ontario

Pontypool is an unincorporated village within the southernmost part of the amalgamated city of Kawartha Lakes, Ontario.

Prior to amalgamation, Pontypool was an unincorporated village within the township of Manvers, in the county of Victoria.

It ...

(d. 2004)

**

Edward Abbey

Edward Paul Abbey (January 29, 1927 – March 14, 1989) was an American author and essayist noted for his advocacy of environmental issues, criticism of public land policies, and anarchist political views. His best-known works include the nov ...

, American environmentalist; in

Indiana, Pennsylvania

Indiana is a borough in Indiana County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. The population was 14,044 at the 2020 census. It is the principal city of the Indiana, Pennsylvania micropolitan area, about northeast of Pittsburgh. ...

(d. 1989)

January 30, 1927 (Sunday)

*At the

Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

n village of

Schattendorf

Schattendorf (, ) is a town in the district of Mattersburg in the Austrian state of Burgenland.

The Rosalia-Kogelberg nature preserve lies within the district.

History

This district was a part of the pre-Christian Celtic Kingdom Noricum and w ...

, members of the

right-wing veterans' organization "Frontkampfer Vereinigung" fired on members of the leftist organization

Schutzbund

The ''Republikanischer Schutzbund'' (, "Republican Protection League") was an Austrian paramilitary organisation established in 1923 by the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Austria to defend the Austrian Republic in the face of rising politic ...

, killing one of them and seriously wounding five others. An 8-year old bystander was killed by the gunfire. When a jury acquitted the three Frontkampfer three months later, 84 protesters were killed by the Austrian police.

*Born:

Olof Palme

Sven Olof Joachim Palme (; ; 30 January 1927 – 28 February 1986) was a Swedish politician and statesman who served as Prime Minister of Sweden from 1969 to 1976 and 1982 to 1986. Palme led the Swedish Social Democratic Party from 1969 until as ...

,

Prime Minister of Sweden

The prime minister of Sweden (, "minister of state") is the head of government of the Sweden, Kingdom of Sweden. The prime minister and their cabinet (the government) exercise executive authority in the Kingdom of Sweden and are subject to th ...

1969–76 and 1982–86; in

Östermalm

Östermalm (; "Eastern city-borough") is a 2.56 km2 large district in central Stockholm, Sweden. With 71,802 inhabitants, it is one of Sweden's most populous and exclusive districts. It is an extremely expensive area, having the highest ho ...

(assassinated 1986)

January 31, 1927 (Monday)

*After seven years, the Inter-Allied Military Commission, which had overseen the occupation of Germany since the end of

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, closed its headquarters in

Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

after France's Marshal

Ferdinand Foch

Ferdinand Foch ( , ; 2 October 1851 – 20 March 1929) was a French general, Marshal of France and a member of the Académie Française and French Academy of Sciences, Académie des Sciences. He distinguished himself as Supreme Allied Commander ...

declared that Germany's obligations under the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

had been completed.

*

Mae West

Mary Jane "Mae" West (August 17, 1893 – November 22, 1980) was an American actress, singer, comedian, screenwriter, and playwright whose career spanned more than seven decades. Recognized as a prominent sex symbol of her time, she was known ...

's play ''The Drag'', the first theatrical production to address homosexuality, had its world premiere in

Bridgeport, Connecticut

Bridgeport is the List of municipalities in Connecticut, most populous city in the U.S. state of Connecticut and the List of cities in New England by population, fifth-most populous city in New England, with a population of 148,654 in 2020. Loc ...

. West hired 40 gay men for the cast. Although profitable, the play was banned by police in

Bayonne, New Jersey

Bayonne ( ) is a City (New Jersey), city in Hudson County, New Jersey, Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey, in the Gateway Region on Bergen Neck, a peninsula between Newark Bay to the west, the Kill Van Kull to the south, and New York ...

, and was unable to find a theatre in New York City.

*Died:

Sybil Bauer

Sybil Lorina Bauer (September 18, 1903 – January 31, 1927) was an American competition swimmer, Olympic champion, and former world record-holder. She represented the United States at the 1924 Summer Olympics, where she won the gold medal in t ...

, 23, American swimmer who broke 23 women's world records and (in 1922) the men's world record for the 440 backstroke, died of cancer. Bauer, who did not learn to swim until she was 15, had been engaged to marry

Ed Sullivan

Edward Vincent Sullivan (September 28, 1901 – October 13, 1974) was an American television host, impresario, sports and entertainment reporter, and syndicated columnist for the ''New York Daily News'' and the Chicago Tribune New York News ...

.

References

{{Events by month links

1927

Events January

* January 1 – The British Broadcasting ''Company'' becomes the BBC, British Broadcasting ''Corporation'', when its Royal Charter of incorporation takes effect. John Reith, 1st Baron Reith, John Reith becomes the first ...

*1927-01

The following events occurred in January 1927:

The following events occurred in January 1927:

*British concessions in

*British concessions in  *The

*The