Jan Smuts on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Smuts was born on 24 May 1870, at the family farm, Bovenplaats, near

Smuts was born on 24 May 1870, at the family farm, Bovenplaats, near

On 11 October 1899 the Boer republics declared war and launched an offensive into the British-held Natal and

On 11 October 1899 the Boer republics declared war and launched an offensive into the British-held Natal and

Despite Smuts's exploits as a general and a negotiator, nothing could mask the fact that the Boers had been defeated. Lord Milner had full control of all South African affairs, and established an

Despite Smuts's exploits as a general and a negotiator, nothing could mask the fact that the Boers had been defeated. Lord Milner had full control of all South African affairs, and established an

During the

During the

After nine years in opposition and academia, Smuts returned as

After nine years in opposition and academia, Smuts returned as

In domestic policy, a number of social security reforms were carried out during Smuts's second period in office as prime minister. Old-age pensions and disability grants were extended to 'Indians' and 'Africans' in 1944 and 1947 respectively, although there were differences in the level of grants paid out based on race. The Workmen's Compensation Act of 1941 "insured all employees irrespective of payment of the levy by employers and increased the number of diseases covered by the law," and the Unemployment Insurance Act of 1946 introduced unemployment insurance on a national scale, albeit with exclusions.

Smuts continued to represent his country abroad. He was a leading guest at the 1947 wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.

At home, his preoccupation with the war had severe political repercussions in South Africa. Smuts's support of the war and his support for the Fagan Commission made him unpopular amongst the Afrikaner community and Daniel François Malan's pro-apartheid stance won the Reunited National Party the 1948 general election.

In 1948, he was elected Chancellor of the University of Cambridge, becoming the first person from outside the United Kingdom to hold that position. He held the position until his death two years later.

He accepted the appointment as Colonel-in-Chief of Regiment Westelike Provinsie as from 17 September 1948.

In 1949, Smuts was bitterly opposed to the

In domestic policy, a number of social security reforms were carried out during Smuts's second period in office as prime minister. Old-age pensions and disability grants were extended to 'Indians' and 'Africans' in 1944 and 1947 respectively, although there were differences in the level of grants paid out based on race. The Workmen's Compensation Act of 1941 "insured all employees irrespective of payment of the levy by employers and increased the number of diseases covered by the law," and the Unemployment Insurance Act of 1946 introduced unemployment insurance on a national scale, albeit with exclusions.

Smuts continued to represent his country abroad. He was a leading guest at the 1947 wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.

At home, his preoccupation with the war had severe political repercussions in South Africa. Smuts's support of the war and his support for the Fagan Commission made him unpopular amongst the Afrikaner community and Daniel François Malan's pro-apartheid stance won the Reunited National Party the 1948 general election.

In 1948, he was elected Chancellor of the University of Cambridge, becoming the first person from outside the United Kingdom to hold that position. He held the position until his death two years later.

He accepted the appointment as Colonel-in-Chief of Regiment Westelike Provinsie as from 17 September 1948.

In 1949, Smuts was bitterly opposed to the

In 1943 Chaim Weizmann wrote to Smuts, detailing a plan to develop Britain's African colonies to compete with the United States. During his service as premier, Smuts personally fundraised for multiple Zionist organisations.Hunter, pp 21–22 His government granted ''de facto'' recognition to Israel on 24 May 1948.Beit-Hallahmi, pp 109–111 However, Smuts was deputy prime minister when the J. B. M. Hertzog government, Hertzog government in 1937 passed the Aliens Act 1937, Aliens Act that was aimed at preventing Jewish immigration to South Africa. The act was seen as a response to growing anti-Semitic sentiments among Afrikaners.

Smuts lobbied against the White Paper of 1939,Crossman, p. 76 and several streets and a kibbutz, Ramat Yohanan, in Israel are named after him. He also wrote an epitaph for Weizmann, describing him as "the greatest Jew since Moses."Lockyer, Norman. ''Nature'', digitized 5 February 2007. Nature Publishing Group. Smuts once said:

In 1943 Chaim Weizmann wrote to Smuts, detailing a plan to develop Britain's African colonies to compete with the United States. During his service as premier, Smuts personally fundraised for multiple Zionist organisations.Hunter, pp 21–22 His government granted ''de facto'' recognition to Israel on 24 May 1948.Beit-Hallahmi, pp 109–111 However, Smuts was deputy prime minister when the J. B. M. Hertzog government, Hertzog government in 1937 passed the Aliens Act 1937, Aliens Act that was aimed at preventing Jewish immigration to South Africa. The act was seen as a response to growing anti-Semitic sentiments among Afrikaners.

Smuts lobbied against the White Paper of 1939,Crossman, p. 76 and several streets and a kibbutz, Ramat Yohanan, in Israel are named after him. He also wrote an epitaph for Weizmann, describing him as "the greatest Jew since Moses."Lockyer, Norman. ''Nature'', digitized 5 February 2007. Nature Publishing Group. Smuts once said:

"Revisiting Urban African Policy and the Reforms of the Smuts Government, 1939–48", by Gary Baines

''Africa and Some World Problems'' by Jan Smuts

at the Internet Archive

''Holism and Evolution'' by Jan Smuts

at the Internet Archive

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Smuts, Jan Jan Smuts, 1870 births 1950 deaths 20th-century South African philosophers Afrikaner anti-apartheid activists Afrikaner people Alumni of Christ's College, Cambridge Alumni of Paul Roos Gymnasium Apartheid in South Africa British field marshals Chancellors of the University of Cambridge Chancellors of the University of Cape Town Commanders of the Legion of Honour Defence ministers of South Africa Fellows of the Royal Society (Statute 12) Ministers of finance of South Africa Foreign ministers of South Africa Justice ministers of South Africa Legion of Frontiersmen members Members of the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa Members of the House of Assembly (South Africa) Members of the Order of Merit Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour Military personnel from the Western Cape Ministers of home affairs of South Africa People from the West Coast District Municipality Presidents of the Southern Africa Association for the Advancement of Science Prime ministers of South Africa Recipients of the Croix de guerre (Belgium) Rectors of the University of St Andrews South Africa and the Commonwealth of Nations South African anti-communists South African anti-fascists South African Christian Zionists South African members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom South African military leaders South African military personnel of World War I South African mountain climbers South African Party (Union of South Africa) politicians South African people of Dutch descent South African people of World War I South African people of World War II South African Queen's Counsel South African Republic generals South African Republic military personnel of the Second Boer War Systems scientists United Party (South Africa) politicians World War II political leaders

Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army (in countries without the rank of Generalissimo), and as such, few persons a ...

Jan Christian Smuts, (baptismal name Jan Christiaan Smuts, 24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

of the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa (; , ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day South Africa, Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the British Cape Colony, Cape, Colony of Natal, Natal, Tra ...

from 1919 to 1924 and 1939 to 1948.

Smuts was born to Afrikaner

Afrikaners () are a Southern African ethnic group descended from predominantly Dutch settlers who first arrived at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: Brain to Casting''. Encyclopæd ...

parents in the British Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

. He was educated at Victoria College, Stellenbosch

Stellenbosch (; )A Universal Pronouncing Gazetteer.

Thomas Baldwin ...

before reading law at Christ's College, Cambridge on a scholarship. He was Thomas Baldwin ...

called to the bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

at the Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court entitled to Call to the bar, call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple (with whi ...

in 1894 but returned home the following year. In the leadup to the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

, Smuts practised law in Pretoria

Pretoria ( ; ) is the Capital of South Africa, administrative capital of South Africa, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to the country.

Pretoria strad ...

, the capital of the South African Republic

The South African Republic (, abbreviated ZAR; ), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer republics, Boer republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it was annexed into the British Empire as a result ...

. He led the republic's delegation to the Bloemfontein Conference and served as an officer in a commando unit following the outbreak of war in 1899. In 1902, he played a key role in negotiating the Treaty of Vereeniging

The Treaty of Vereeniging was a peace treaty, signed on 31 May 1902, that ended the Second Boer War between the South African Republic and the Orange Free State on the one side, and the United Kingdom on the other.

This settlement provided ...

, which ended the war and resulted in the annexation of the South African Republic and Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( ; ) was an independent Boer-ruled sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeated and surrendered to the British Em ...

into the British Empire. He subsequently helped negotiate self-government for the Transvaal Colony

The Transvaal Colony () was the name used to refer to the Transvaal region during the period of direct British rule and military occupation between the end of the Second Boer War in 1902 when the South African Republic was dissolved, and the ...

, becoming a cabinet minister under Louis Botha.

Smuts played a leading role in the creation of the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa (; , ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day South Africa, Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the British Cape Colony, Cape, Colony of Natal, Natal, Tra ...

in 1910, helping shape its constitution. He and Botha established the South African Party, with Botha becoming the union's first prime minister and Smuts holding multiple cabinet portfolios. As defence minister

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is the part of a government responsible for matters of defence and military forces, found in states where the government is divid ...

he was responsible for the Union Defence Force during the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. Smuts personally led troops in the East African campaign in 1916 and the following year joined the Imperial War Cabinet in London. He played a leading role at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, advocating for the creation of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

and securing South African control over the former German South-West Africa.

In 1919, Smuts replaced Botha as prime minister, holding the office until the South African Party's defeat at the 1924 general election by J. B. M. Hertzog's National Party. He spent several years in academia, during which he coined the term "holism

Holism is the interdisciplinary idea that systems possess properties as wholes apart from the properties of their component parts. Julian Tudor Hart (2010''The Political Economy of Health Care''pp.106, 258

The aphorism "The whole is greater than t ...

", before eventually re-entering politics as deputy prime minister in a coalition with Hertzog; in 1934 their parties subsequently merged to form the United Party. Smuts returned as prime minister in 1939, leading South Africa into the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

at the head of a pro-interventionist faction. He was appointed field marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army (in countries without the rank of Generalissimo), and as such, few persons a ...

in 1941 and in 1945 signed the UN Charter

The Charter of the United Nations is the foundational treaty of the United Nations (UN). It establishes the purposes, governing structure, and overall framework of the United Nations System, UN system, including its United Nations System#Six ...

, the only signer of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

to do so. His second term in office ended with the victory of his political opponents, the reconstituted National Party at the 1948 general election, with the new government implementing early apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

policies.

Smuts was an internationalist who played a key role in establishing and defining the League of Nations, United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

and Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an International organization, international association of member states of the Commonwealth of Nations, 56 member states, the vast majo ...

. He supported racial segregation and opposed democratic non-racial rule. At the end of his career, Smuts supported the Fagan Commission's recommendations to relax restrictions on black South Africans living and working in urban areas.

Early life and education

Smuts was born on 24 May 1870, at the family farm, Bovenplaats, near

Smuts was born on 24 May 1870, at the family farm, Bovenplaats, near Malmesbury

Malmesbury () is a town and civil parish in north Wiltshire, England, which lies approximately west of Swindon, northeast of Bristol, and north of Chippenham. The older part of the town is on a hilltop which is almost surrounded by the upp ...

, in the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

. His parents, Jacobus Smuts and his wife Catharina, were prosperous, traditional Afrikaner

Afrikaners () are a Southern African ethnic group descended from predominantly Dutch settlers who first arrived at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: Brain to Casting''. Encyclopæd ...

farmers, long established and highly respected.

As the second son of the family, rural custom dictated that Jan would remain working on the farm. In this system, typically only the first son was supported for a full, formal education. In 1882, when Jan was twelve, his elder brother died, and Jan was sent to school in his place. Jan attended the school in nearby Riebeek West. He made excellent progress despite his late start, and caught up with his contemporaries within four years. He was admitted to Victoria College, Stellenbosch

Stellenbosch (; )A Universal Pronouncing Gazetteer.

Thomas Baldwin ...

, in 1886, at the age of sixteen.

At Stellenbosch, he learned High Dutch, German, and Thomas Baldwin ...

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

, and immersed himself in literature, the classics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

, and Bible studies. His deeply traditional upbringing and serious outlook led to social isolation from his peers. He made outstanding academic progress, graduating in 1891 with double first-class honours in Literature and Science. During his last years at Stellenbosch, Smuts began to cast off some of his shyness and reserve. At this time he met Isie Krige, whom he later married.

On graduation from Victoria College, Smuts won the Ebden scholarship for overseas study. He decided to attend the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

in the United Kingdom to read law at Christ's College. Smuts found it difficult to settle at Cambridge. He felt homesick and isolated by his age and different upbringing from the English undergraduates. Worries over money also contributed to his unhappiness, as his scholarship was insufficient to cover his university expenses. He confided these worries to Professor J. I. Marais, a friend from Victoria College. In reply, Professor Marais enclosed a cheque for a substantial sum, by way of loan, encouraging Smuts to let him know if he ever found himself in need again. Thanks to Marais, Smuts's financial standing was secure. He gradually began to enter more into the social aspects of the university, although he retained a single-minded dedication to his studies.

During this time in Cambridge, Smuts studied a diverse number of subjects in addition to law. He wrote a book, '' Walt Whitman: A Study in the Evolution of Personality''. It was not published until 1973, after his death, but it can be seen that Smuts in this book had already conceptualized his thinking for his later wide-ranging philosophy of holism

Holism is the interdisciplinary idea that systems possess properties as wholes apart from the properties of their component parts. Julian Tudor Hart (2010''The Political Economy of Health Care''pp.106, 258

The aphorism "The whole is greater than t ...

.

Smuts graduated in 1894 with a double first

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a Grading in education, grading structure used for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and Master's degree#Integrated Masters Degree, integrated master's degrees in the United Kingd ...

. Over the previous two years, he had received numerous academic prizes and accolades, including the coveted George Long prize in Roman Law and Jurisprudence. One of his tutors, Frederic William Maitland, a leading figure among English legal historians, described Smuts as the most brilliant student he had ever met. Alec Todd, the Master of Christ's College, said in 1970 that "in 500 years of the College's history, of all its members, past and present, three had been truly outstanding: John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet, polemicist, and civil servant. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost'' was written in blank verse and included 12 books, written in a time of immense religious flux and politic ...

, Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

and Jan Smuts."

In December 1894, Smuts passed the examinations for the Inns of Court

The Inns of Court in London are the professional associations for barristers in England and Wales. There are four Inns of Court: Gray's Inn, Lincoln's Inn, Inner Temple, and Middle Temple.

All barristers must belong to one of them. They have s ...

, entering the Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court entitled to Call to the bar, call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple (with whi ...

. His old Cambridge college, Christ's College, offered him a fellowship in Law. Smuts turned his back on a potentially distinguished legal future. By June 1895, he had returned to the Cape Colony, determined to make his future there.

Career

Law and politics

Smuts began to practise law inCape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

, but his abrasive nature made him few friends. Finding little financial success in the law, he began to devote more and more of his time to politics and journalism, writing for the '' Cape Times''. Smuts was intrigued by the prospect of a united South Africa, and joined the Afrikaner Bond. By good fortune, Smuts's father knew the leader of the group, Jan Hofmeyr. Hofmeyr in turn recommended Jan to Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes ( ; 5 July 185326 March 1902) was an English-South African mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. He and his British South Africa Company founded th ...

, who owned the De Beers mining company. In 1895, Smuts became an advocate and supporter of Rhodes.Heathcote, p. 264

When Rhodes launched the Jameson Raid, in the summer of 1895–96, Smuts was outraged. Feeling betrayed by his employer, friend and political ally, he resigned from De Beers, and left political life. Instead he became state attorney in the capital of the South African Republic

The South African Republic (, abbreviated ZAR; ), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer republics, Boer republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it was annexed into the British Empire as a result ...

, Pretoria

Pretoria ( ; ) is the Capital of South Africa, administrative capital of South Africa, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to the country.

Pretoria strad ...

.

After the Jameson Raid, relations between the British and the Afrikaners had deteriorated steadily. By 1898, war seemed imminent. Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( ; ) was an independent Boer-ruled sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeated and surrendered to the British Em ...

President Martinus Steyn called for a peace conference

A peace conference is a diplomatic meeting where representatives of states, armies, or other warring parties converge to end hostilities by negotiation and signing and ratifying a peace treaty.

Significant international peace conferences in ...

at Bloemfontein

Bloemfontein ( ; ), also known as Bloem, is the capital and the largest city of the Free State (province), Free State province in South Africa. It is often, and has been traditionally, referred to as the country's "judicial capital", alongsi ...

to settle each side's grievances. With an intimate knowledge of the British, Smuts took control of the Transvaal delegation. Sir Alfred Milner

Alfred Milner, 1st Viscount Milner, (23 March 1854 – 13 May 1925) was a British politician, statesman and colonial administrator who played a very important role in the formulation of British foreign and domestic policy between the mid-189 ...

, head of the British delegation, took exception to his dominance, and conflict between the two led to the collapse of the conference, consigning South Africa to war.

Psychology

Smuts was the first South African to be internationally regarded as an important psychologist. During Smuts's undergraduate years at Cambridge University, he produced a manuscript in 1895 in which he analysed the personality of the famous American poet Walt Whitman. Due to his manuscript being considered unviable, it was only published 23 years after his death in 1973. Smuts went on to produce his next manuscript, which he completed in 1910, entitled ''An Inquiry into the Whole''. His manuscript was then revised in 1924 and published in 1926 with the title '' Holism and Evolution''. Smuts had no interest in pursuing a career in psychology. He considered psychology as "too impersonal to study great personalities", and believed that the holistic tendency of the personality would be studied best through personology. Smuts, however, never inquired further into the idea of personology due to him wanting to continue laying the foundation of the concept of holism. He never returned to either of the topics. Holism Although the concept of holism has been discussed by many, the term holism in academic terminology was first introduced and publicly shared in print by Smuts in the early twentieth century. Smuts was acknowledged for his contribution by getting the honour to write the first entry about the concept for the Encyclopaedia Britannica 1929 edition. The Austrian medical doctor, founder of the school of Individual Psychology, and psychotherapist,Alfred Adler

Alfred Adler ( ; ; 7 February 1870 – 28 May 1937) was an Austrian medical doctor, psychotherapist, and founder of the school of individual psychology. His emphasis on the importance of feelings of belonging, relationships within the family, a ...

(1870–1937), also showed a great interest in Smuts's book. Adler requested permission from Smuts to have the book translated to German and published in Germany.

Although Smuts's concept of holism is grounded in the natural sciences, he claimed that it has a relevance in philosophy, ethics, sociology, and psychology. In ''Holism and Evolution'', he argued that the concept of holism is "grounded in evolution and is also an ideal that guides human development and one's level of personality actualization." Smuts stated in the book that "personality is the highest form of holism" (p. 292).

Recognition from Adler

Adler later wrote a letter, dated 31 January 1931, where he stated that he recommended Smuts's book to his students and followers. He referred to it as "the best preparation for the science of Individual Psychology". After Smuts gave permission for the translation and publication of his book in Germany, it was translated by H. Minkowski and eventually published in 1938. During the Second World War, the books were destroyed after the Nazi government had removed it from circulation. Adler and Smuts, however, continued their correspondence. In one of Adler’s letters dated 14 June 1931, he invited Smuts to be one of three judges of the best book on the history of wholeness with a reference to Individual Psychology.

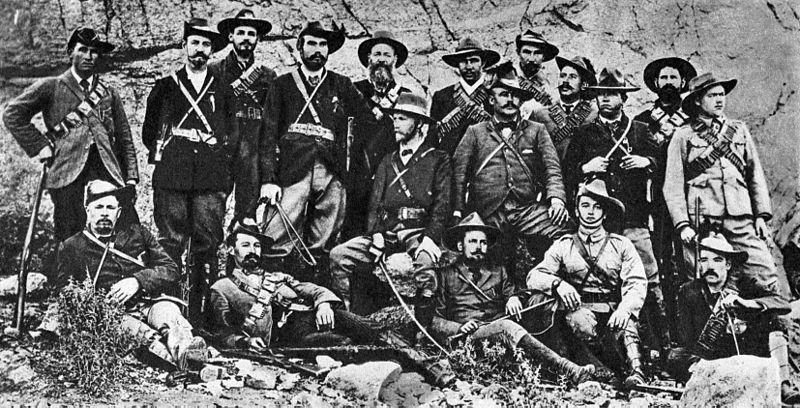

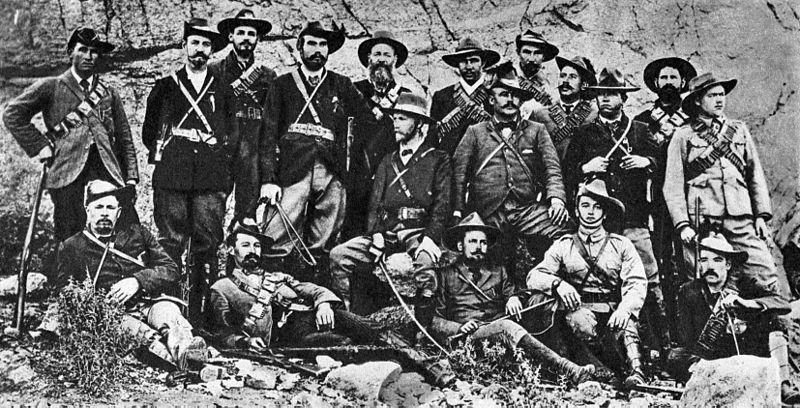

The Boer War

On 11 October 1899 the Boer republics declared war and launched an offensive into the British-held Natal and

On 11 October 1899 the Boer republics declared war and launched an offensive into the British-held Natal and Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

areas, beginning the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

of 1899–1902. In the early stages of the conflict, Smuts served as Paul Kruger

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger (; 10 October 1825 – 14 July 1904), better known as Paul Kruger, was a South African politician. He was one of the dominant political and military figures in 19th-century South Africa, and State Preside ...

's eyes and ears in Pretoria, handling propaganda, logistics, communication with generals and diplomats, and anything else that was required. In the second phase of the war, from mid-1900, Smuts served under Koos de la Rey, who commanded 500 commandos in the Western Transvaal. Smuts excelled at hit-and-run warfare, and the unit evaded and harassed a British army forty times its size. President Paul Kruger

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger (; 10 October 1825 – 14 July 1904), better known as Paul Kruger, was a South African politician. He was one of the dominant political and military figures in 19th-century South Africa, and State Preside ...

and the deputation in Europe thought that there was good hope for their cause in the Cape Colony. They decided to send General de la Rey there to assume supreme command, but then decided to act more cautiously when they realised that General de la Rey could hardly be spared in the Western Transvaal. Consequently, Smuts was left with a small force of 300 men, while another 100 men followed him. By January 1902 the British scorched-earth policy

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy of destroying everything that allows an enemy military force to be able to fight a war, including the deprivation and destruction of water, food, humans, animals, plants and any kind of tools and i ...

left little grazing land. One hundred of the cavalry that had joined Smuts were therefore too weak to continue and so Smuts had to leave these men with General Pieter Hendrik Kritzinger. Intelligence indicated that at this time Smuts had about 3,000 men.

To end the conflict, Smuts sought to take a major target, the copper-mining town of Okiep in the present-day Northern Cape

The Northern Cape ( ; ; ) is the largest and most sparsely populated Provinces of South Africa, province of South Africa. It was created in 1994 when the Cape Province was split up. Its capital is Kimberley, South Africa, Kimberley. It includes ...

Province (April–May 1902). With a full assault impossible, Smuts packed a train full of explosives, and tried to push it downhill, into the town, in order to bring the enemy garrison to its knees. Although this failed, Smuts had proved his point: that he would stop at nothing to defeat his enemies. Norman Kemp Smith wrote that General Smuts read from Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

's ''Critique of Pure Reason

The ''Critique of Pure Reason'' (; 1781; second edition 1787) is a book by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in which the author seeks to determine the limits and scope of metaphysics. Also referred to as Kant's "First Critique", it was foll ...

'' on the evening before the raid. Smith contended that this showed how Kant's critique can be a solace and a refuge, as well as a means to sharpen the wit. Combined with the British failure to pacify the Transvaal, Smuts's success left the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

with no choice but to offer a ceasefire and a peace conference, to be held at Vereeniging.

Before the conference, Smuts met Lord Kitchener at Kroonstad railway station, where they discussed the proposed terms of surrender. Smuts then took a leading role in the negotiations between the representatives from all of the commandos from the Orange Free State and the South African Republic (15–31 May 1902). Although he admitted that, from a purely military perspective, the war could continue, he stressed the importance of not sacrificing the Afrikaner people for that independence. He was very conscious that "more than 20,000 women and children have already died in the concentration camps

A concentration camp is a prison or other facility used for the internment of political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or ethnic minority groups, on the grounds of national security, or for exploit ...

of the enemy". He felt it would have been a crime to continue the war without the assurance of help from elsewhere and declared, "Comrades, we decided to stand to the bitter end. Let us now, like men, admit that that end has come for us, come in a more bitter shape than we ever thought." His opinions were representative of the conference, which then voted by 54 to 6 in favour of peace. Representatives of the Governments met Lord Kitchener and at five minutes past eleven on 31 May 1902, the Acting State President of the South African Republic, Schalk Willem Burger signed the Treaty of Vereeniging

The Treaty of Vereeniging was a peace treaty, signed on 31 May 1902, that ended the Second Boer War between the South African Republic and the Orange Free State on the one side, and the United Kingdom on the other.

This settlement provided ...

, followed by the members of his government, Acting State President of the Orange Free State, Christiaan De Wet, and the members of his government.

A British Transvaal

Despite Smuts's exploits as a general and a negotiator, nothing could mask the fact that the Boers had been defeated. Lord Milner had full control of all South African affairs, and established an

Despite Smuts's exploits as a general and a negotiator, nothing could mask the fact that the Boers had been defeated. Lord Milner had full control of all South African affairs, and established an Anglophone

The English-speaking world comprises the 88 countries and territories in which English is an official, administrative, or cultural language. In the early 2000s, between one and two billion people spoke English, making it the largest language ...

elite, known as Milner's Kindergarten. As an Afrikaner, Smuts was excluded. Defeated but not deterred, in January 1905, he decided to join with the other former Transvaal generals to form a political party, ''Het Volk'' ('The People'), to fight for the Afrikaner cause. Louis Botha was elected leader, and Smuts his deputy.

When his term of office expired, Milner was replaced as High Commissioner by the more conciliatory William Palmer, 2nd Earl of Selborne. Smuts saw an opportunity and pounced, urging Botha to persuade the Liberals to support ''Het Volk's'' cause. When the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

government under Arthur Balfour collapsed, in December 1905, the decision paid off. Smuts joined Botha in London, and sought to negotiate responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

for the Transvaal within British South Africa. Using the thorny political issue of South Asian labourers ('coolie

Coolie (also spelled koelie, kouli, khuli, khulie, kuli, cooli, cooly, or quli) is a pejorative term used for low-wage labourers, typically those of Indian people, Indian or Chinese descent.

The word ''coolie'' was first used in the 16th cent ...

s'), the South Africans convinced Prime Minister Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman and, with him, the cabinet and Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

.

Through 1906, Smuts worked on the new constitution for the Transvaal, and, in December 1906, elections were held for the Transvaal parliament. Despite being shy and reserved, unlike the showman Botha, Smuts won a comfortable victory in the Wonderboom constituency, near Pretoria. His victory was one of many, with ''Het Volk'' winning in a landslide

Landslides, also known as landslips, rockslips or rockslides, are several forms of mass wasting that may include a wide range of ground movements, such as rockfalls, mudflows, shallow or deep-seated slope failures and debris flows. Landslides ...

and Botha forming the government. To reward his loyalty and efforts, Smuts was given two key cabinet positions: Colonial Secretary and Education Secretary.

Smuts proved to be an effective leader, if unpopular. As Education Secretary, he had fights with the Dutch Reformed Church

The Dutch Reformed Church (, , abbreviated NHK ) was the largest Christian denomination in the Netherlands from the onset of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century until 1930. It was the traditional denomination of the Dutch royal famil ...

, of which he had once been a dedicated member, which demanded Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

teachings in schools. As Colonial Secretary, he opposed a movement for equal rights for South Asian

South Asia is the southern Subregion#Asia, subregion of Asia that is defined in both geographical and Ethnicity, ethnic-Culture, cultural terms. South Asia, with a population of 2.04 billion, contains a quarter (25%) of the world's populatio ...

workers, led by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.

During the years of Transvaal self-government, nobody could avoid the predominant political debate of the day: South African unification. Ever since the British victory in the war, it was an inevitability, but it remained up to the South Africans to decide what sort of country would be formed, and how it would be formed. Smuts favoured a unitary state

A unitary state is a (Sovereign state, sovereign) State (polity), state governed as a single entity in which the central government is the supreme authority. The central government may create or abolish administrative divisions (sub-national or ...

, with power centralised in Pretoria, with English as the only official language

An official language is defined by the Cambridge English Dictionary as, "the language or one of the languages that is accepted by a country's government, is taught in schools, used in the courts of law, etc." Depending on the decree, establishmen ...

, and with a more inclusive electorate. To impress upon his compatriots his vision, he called a constitutional convention in Durban

Durban ( ; , from meaning "bay, lagoon") is the third-most populous city in South Africa, after Johannesburg and Cape Town, and the largest city in the Provinces of South Africa, province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Situated on the east coast of South ...

, in October 1908.

There, Smuts was up against a hard-talking Orange River Colony delegation, who refused every one of Smuts's demands. Smuts had successfully predicted this opposition, and their objections, and tailored his own ambitions appropriately. He allowed compromise on the location of the capital, on the official language, and on suffrage, but he refused to budge on the fundamental structure of government. As the convention drew into autumn, the Orange leaders began to see a final compromise as necessary to secure the concessions that Smuts had already made. They agreed to Smuts's draft South African constitution, which was duly ratified by the South African colonies. Smuts and Botha took the constitution to London, where it was passed by Parliament and given Royal Assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in othe ...

by King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until Death and state funeral of Edward VII, his death in 1910.

The second child ...

in December 1909.

The Old Boers

TheUnion of South Africa

The Union of South Africa (; , ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day South Africa, Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the British Cape Colony, Cape, Colony of Natal, Natal, Tra ...

was born, and the Afrikaners held the key to political power, as the majority of the increasingly whites-only electorate. Although Botha was appointed prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

of the new country, Smuts was given three key ministries: Interior, Mines, and Defence. Undeniably, Smuts was the second most powerful man in South Africa. To solidify their dominance of South African politics, the Afrikaners united to form the South African Party, a new pan-South African Afrikaner party.

The harmony and co-operation soon ended. Smuts was criticised for his overarching powers, and the cabinet was reshuffled. Smuts lost Interior and Mines, but gained control of Finance

Finance refers to monetary resources and to the study and Academic discipline, discipline of money, currency, assets and Liability (financial accounting), liabilities. As a subject of study, is a field of Business administration, Business Admin ...

. That was still too much for Smuts's opponents, who decried his possession of both Defence and Finance, two departments that were usually at loggerheads. At the 1913 South African Party conference, the Old Boers ( J. B. M. Hertzog, Martinus Theunis Steyn, Christiaan de Wet), called for Botha and Smuts to step down. The two narrowly survived a confidence vote, and the troublesome triumvirate stormed out, leaving the party for good.

With the schism in internal party politics came a new threat to the mines that brought South Africa its wealth. A small-scale miners' dispute flared into a full-blown strike, and rioting broke out in Johannesburg after Smuts intervened heavy-handedly. After police shot dead twenty-one strikers, Smuts and Botha headed unaccompanied to Johannesburg to resolve the situation personally. Facing down threats to their own lives, they negotiated a cease-fire. But the cease-fire did not hold, and in 1914, a railway strike turned into a general strike

A general strike is a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coalitions ...

. Threats of a revolution caused Smuts to declare martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

. He acted ruthlessly, deporting union leaders without trial and using Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

to absolve him and the government of any blame retroactively. That was too much for the Old Boers, who set up their own National Party to fight the all-powerful Botha-Smuts partnership.

First World War

During the

During the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Smuts formed the Union Defence Force (UDF). His first task was to suppress the Maritz Rebellion, which was accomplished by November 1914. Next he and Louis Botha led the South African army into German South-West Africa and conquered it (see the South-West Africa Campaign for details). In 1916 General Smuts was put in charge of the conquest of German East Africa. Col (later BGen) J. H. V. Crowe commanded the artillery in East Africa under General Smuts and published an account of the campaign, ''General Smuts' Campaign in East Africa'' in 1918. Smuts was promoted to temporary lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was norma ...

on 18 February 1916, and to honorary lieutenant general for distinguished service in the field on 1 January 1917.

Smuts's chief intelligence officer, Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, wrote very critically of his conduct of the campaign. He believed Horace Smith-Dorrien (who had saved the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

during the retreat from Mons and was the original choice as commander in 1916) would have quickly defeated the Germans. In particular, Meinertzhagen thought that frontal attacks would have been decisive, and less costly than the flanking movements preferred by Smuts, which took longer, so that thousands of Imperial troops died of disease in the field. He wrote: "Smuts has cost Britain many hundreds of lives and many millions of pounds by his caution... Smuts was not an astute soldier; a brilliant statesman and politician but no soldier." Meinertzhagen wrote these comments in October/November 1916, in the weeks after being relieved by Smuts due to symptoms of depression, and he was invalided back to England shortly thereafter.

Early in 1917, Smuts left Africa and went to London, as he had been invited to join the Imperial War Cabinet and the War Policy Committee by David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

. Smuts initially recommended renewed Western Front attacks and a policy of attrition, lest with Russian commitment to the war wavering, France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

or Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

would be tempted to make a separate peace. Lloyd George wanted a commander "of the dashing type" for the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

in succession to Archibald Murray, but Smuts refused the command (late May) unless promised resources for a decisive victory, and he agreed with William Robertson that Western Front commitments did not justify a serious attempt to capture Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

. Edmund Allenby was appointed instead. Like other members of the War Cabinet, Smuts's commitment to Western Front efforts was shaken by Third Ypres.

In 1917, following the German Gotha Raids, and lobbying by Viscount French, Smuts wrote a review of the British Air Services, which came to be called the Smuts Report. He was helped in large part in this by General Sir David Henderson who was seconded to him. This report led to the treatment of air as a separate force, which eventually became the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

.

By mid-January 1918, Lloyd George was toying with the idea of appointing Smuts Commander-in-Chief of all land and sea forces facing the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, reporting directly to the War Cabinet rather than to Robertson. Early in 1918, Smuts was sent to Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

to confer with Allenby and William Marshall, and prepare for major efforts in that theatre. Before his departure, alienated by Robertson's exaggerated estimates of the required reinforcements, he urged Robertson's removal. Allenby told Smuts of Robertson's private instructions (sent by hand of Walter Kirke, appointed by Robertson as Smuts's adviser) that there was no merit in any further advance. He worked with Smuts to draw up plans, using three reinforcement divisions from Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

, to reach Haifa

Haifa ( ; , ; ) is the List of cities in Israel, third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropolitan area i ...

by June and Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

by the autumn, the speed of the advance limited by the need to lay fresh rail track. This was the foundation of Allenby's successful offensive later in the year.

Like most British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

political and military leaders in the First World War, Smuts thought the American Expeditionary Forces lacked the proper leadership and experience to be effective quickly. He supported the Anglo-French amalgamation policy towards the Americans. In particular, he had a low opinion of General John J. Pershing's leadership skills, so much so that he proposed to Lloyd George that Pershing be relieved of command and US forces be placed "under someone more confident, like imself. This did not endear him to the Americans once it was leaked.

Statesman

Smuts and Botha were key negotiators at the Paris Peace Conference. Both were in favour of reconciliation withGermany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and limited reparations. Smuts was a key architect of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

through his correspondences with Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

, his work with the Imperial War Cabinet during the First World War and his book ''League of Nations: A Practical Suggestion''. According to Jacob Kripp, Smuts saw the League as necessary in unifying white internationalists and pacifying a race war through indirect rule by Europeans over non-whites and segregation. Kripp states that the League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate represented a legal status under international law for specific territories following World War I, involving the transfer of control from one nation to another. These mandates served as legal documents establishing th ...

s system reflected a compromise between Smuts's desire to annex non-white territories and Woodrow Wilson's principles of trusteeship.

He was sent to Budapest

Budapest is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns of Hungary, most populous city of Hungary. It is the List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, tenth-largest city in the European Union by popul ...

to negotiate with Béla Kun's Hungarian Soviet Republic. This was in the wake of issues around the neutral zone the Entente dictated in the Vix Note. Smuts arrived on 4 April 1919, and negotiations started the next day. He offered a neutral zone more favorable to Hungary (shifted 25 km east), though making sure its western border passed west of the final border proposal worked out in the Commission on Romanian and Yugoslav Affairs, that the Hungarian leaders were unaware of. Smuts reassured the Hungarians that the agreement would not influence Hungary's final borders. He also teased the lifting of the economic blockade of the country and inviting the Hungarian soviet leaders to the Paris Peace Conference. Kun rejected the terms, and demanded the return to the Belgrade armistice line later that day, upon which Smuts ended negotiations and left. On 8 April he negotiated with Tomáš Masaryk in Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

over the Hungarian border. Hungary's rejection led to the conference's approval of a Czechoslovak- Romanian invasion and harsher terms in the Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon (; ; ; ), often referred to in Hungary as the Peace Dictate of Trianon or Dictate of Trianon, was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace Conference. It was signed on the one side by Hungary ...

.

The Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

gave South Africa a Class C mandate over German South-West Africa (which later became Namibia

Namibia, officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country on the west coast of Southern Africa. Its borders include the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Angola and Zambia to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south; in the no ...

), which was occupied from 1919 until withdrawal in 1990. At the same time, Australia was given a similar mandate over German New Guinea

German New Guinea () consisted of the northeastern part of the island of New Guinea and several nearby island groups, and was part of the German colonial empire. The mainland part of the territory, called , became a German protectorate in 188 ...

, which it held until 1975. Both Smuts and the Australian prime minister Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia from 1915 to 1923. He led the nation during World War I, and his influence on national politics s ...

feared the rising power of the Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

in the post-First World War world. When the former German East Africa was divided into two mandated territories ( Ruanda-Urundi and Tanganyika), ''Smutsland'' was one of the proposed names for what became Tanganyika. Smuts, who had called for South African territorial expansion all the way to the River Zambesi since the late 19th century, was ultimately disappointed with the League awarding South-West Africa only a mandate status, as he had looked forward to formally incorporating the territory to South Africa.

Smuts returned to South African politics after the conference. When Botha died in 1919, Smuts was elected prime minister, serving until a shocking defeat in 1924 at the hands of the National Party. After the death of the former American President Woodrow Wilson, Smuts was quoted as saying that: "Not Wilson, but humanity failed at Paris."

While in Britain for an Imperial Conference in June 1921, Smuts went to Ireland and met Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (; ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was an American-born Irish statesman and political leader. He served as the 3rd President of Ire ...

to help broker an armistice and peace deal between the warring British and Irish nationalists. Smuts attempted to sell the concept of Ireland receiving Dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

status similar to that of Australia and South Africa.

During his first premiership Smuts was involved in a number of controversies. The first was the Rand Revolt of March 1921, where aeroplanes were used to bomb white miners who were striking in opposition to proposals to allow non-whites to do more skilled and semi-skilled work previously reserved to whites only. Smuts was accused of siding with the Rand Lords who wanted the removal of the colour bar in the hope that it would lower wage costs. The white miners perpetrated acts of violence across the Rand, including murderous attacks on non-Europeans, conspicuously on African miners in their compounds, and this culminated in a general assault on the police. Smuts declared martial law and suppressed the insurrection in three days – at a cost of 291 police and army deaths, and 396 civilians killed. A Martial Law Commission was established which found that Smuts used larger forces than were strictly required, but had saved lives by doing so.

The second was the Bulhoek Massacre of 24 May 1921, when at Bulhoek in the eastern Cape eight hundred South African policemen and soldiers armed with maxim machine guns and two field artillery guns killed 163 and wounded 129 members of an indigenous religious sect known as "Israelites" who had been armed with knobkerries, assegais and swords and who had refused to vacate land they regarded as holy to them. Casualties on the government side at Bulhoek amounted to one trooper wounded and one horse killed. Once again, there were charges of the unnecessary use of overwhelming force. However, no commission of enquiry was appointed.

The third was the Bondelswarts Rebellion, in which Smuts supported the actions of the South African administration in attacking the Bondelswarts in South West Africa

South West Africa was a territory under Union of South Africa, South African administration from 1915 to 1990. Renamed ''Namibia'' by the United Nations in 1968, Independence of Namibia, it became independent under this name on 21 March 1990. ...

. The mandatory administration moved to crush what they called a rebellion of 500 to 600 people, of which 200 were said to be armed (although only about 40 weapons were captured after the Bondelswarts were crushed). Gysbert Hofmeyr, the Mandatory Administrator, organised 400 armed men, and sent in aircraft to bomb the Bondelswarts. Casualties included 100 Bondelswart deaths, including a few women and children. A further 468 men were either wounded or taken prisoner. South Africa's international reputation was tarnished. Ruth First, a South African anti-apartheid activist and scholar, describes the Bondelswarts shooting as "the Sharpeville of the 1920s".

As a botanist, Smuts collected plants extensively over southern Africa. He went on several botanical expeditions in the 1920s and 1930s with John Hutchinson, former botanist-in-charge of the African section of the Herbarium of the Royal Botanic Gardens and taxonomist of note. Smuts was a keen mountaineer and supporter of mountaineering.''Imperial ecology: environmental order in the British Empire, 1895–1945'', Peder Anker Publisher: Harvard University Press, 2001 One of his favourite rambles was up Table Mountain

Table Mountain (; ) is a flat-topped mountain forming a prominent landmark overlooking the city of Cape Town in South Africa.

It is a significant tourist attraction, with many visitors using the Table Mountain Aerial Cableway, cableway or hik ...

along a route now known as Smuts' Track. In February 1923 he unveiled a memorial to members of the Mountain Club who had been killed in the First World War.

In 1925, assessing Smuts's role in international affairs, African-American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

historian and Pan-Africanist W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relativel ...

wrote in an article which would be incorporated into the pivotal Harlem Renaissance text '' The New Negro'',

Jan Smuts is today, in his world aspects, the greatest protagonist of the white race. He is fighting to take control of Laurenço Marques from aIn December 1934, Smuts told an audience at the Royal Institute of International Affairs that:nation A nation is a type of social organization where a collective Identity (social science), identity, a national identity, has emerged from a combination of shared features across a given population, such as language, history, ethnicity, culture, t ...that recognizes, even though it does not realize, the equality of black folk; he is fighting to keepIndia India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...from political and social equality in the empire; he is fighting to insure the continued and eternal subordination of black to white in Africa; and he is fighting for peace and good will in a white Europe which can by union present a united front to the yellow, brown and black worlds. In all this he expresses bluntly, and yet not without finesse, what a powerful host of white folk believe but do not plainly say inMelbourne Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...,New Orleans New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...,San Francisco San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ..., Hongkong,Berlin Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ..., and London.

How can theThough in his Rectorial Address delivered on 17 October 1934 at St Andrews University he stated that:inferiority complex In psychology, an inferiority complex is a consistent feeling of inadequacy, often resulting in the belief that one is in some way deficient, or inferior, to others. According to Alfred Adler, a feeling of inferiority may be brought about by ...which is obsessing and, I fear, poisoning the mind, and indeed the very soul ofGermany Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ..., be removed? There is only one way and that is to recognise her complete equality of status with her fellows and to do so frankly, freely and unreservedly ... While one understands and sympathises with French fears, one cannot, but feel for Germany in the prison of inferiority in which she still remains sixteen years after the conclusion of the war. The continuance of the Versailles status is becoming an offence to the conscience of Europe and a danger to future peace ... Fair play, sportsmanship—indeed every standard of private and public life—calls for frank revision of the situation. Indeed ordinary prudence makes it imperative. Let us break these bonds and set the complexed-obsessed soul free in a decent human way and Europe will reap a rich reward in tranquility, security and returning prosperity.

The new Tyranny, disguised in attractive patriotic colours, is enticing youth everywhere into its service. Freedom must make a great counterstroke to save itself and our fair western civilisation. Once more the heroic call is coming to our youth. The fight for human freedom is indeed the supreme issue of the future, as it has always been.

Second World War

After nine years in opposition and academia, Smuts returned as

After nine years in opposition and academia, Smuts returned as deputy prime minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a Minister (government), government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to th ...

in a 'grand coalition' government under J. B. M. Hertzog. When Hertzog advocated neutrality towards Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

in 1939, the coalition split and Hertzog's motion to remain out of the war was defeated in Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

by a vote of 80 to 67. Governor-General

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

Sir Patrick Duncan refused Hertzog's request to dissolve parliament for a general election on the issue. Hertzog resigned and Duncan invited Smuts, Hertzog's coalition partner, to form a government and become prime minister for the second time in order to lead the country into the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

on the side of the Allies.

On 24 May 1941, Smuts was appointed a field marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army (in countries without the rank of Generalissimo), and as such, few persons a ...

of the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

.

Smuts's importance to the Imperial war effort was emphasised by a quite audacious plan, proposed as early as 1940, to appoint Smuts as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister Advice (constitutional law), advises the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal prerogative ...

, should Churchill die or otherwise become incapacitated during the war. This idea was put forward by Jock Colville, Churchill's private secretary, to Queen Mary and then to George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until Death and state funeral of George VI, his death in 1952 ...

, both of whom warmed to the idea.

In May 1945, he represented South Africa in San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

at the drafting of the United Nations Charter

The Charter of the United Nations is the foundational treaty of the United Nations (UN). It establishes the purposes, governing structure, and overall framework of the United Nations System, UN system, including its United Nations System#Six ...

.Heathcote, p. 266 According to historian Mark Mazower, Smuts "did more than anyone to argue for, and help draft, the UN's stirring preamble." Smuts saw the UN as key to protecting white imperial rule over Africa. Also in 1945, he was mentioned by Halvdan Koht among seven candidates that were qualified for the Nobel Prize in Peace. However, he did not explicitly nominate any of them. The person actually nominated was Cordell Hull.

Later life

In domestic policy, a number of social security reforms were carried out during Smuts's second period in office as prime minister. Old-age pensions and disability grants were extended to 'Indians' and 'Africans' in 1944 and 1947 respectively, although there were differences in the level of grants paid out based on race. The Workmen's Compensation Act of 1941 "insured all employees irrespective of payment of the levy by employers and increased the number of diseases covered by the law," and the Unemployment Insurance Act of 1946 introduced unemployment insurance on a national scale, albeit with exclusions.

Smuts continued to represent his country abroad. He was a leading guest at the 1947 wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.

At home, his preoccupation with the war had severe political repercussions in South Africa. Smuts's support of the war and his support for the Fagan Commission made him unpopular amongst the Afrikaner community and Daniel François Malan's pro-apartheid stance won the Reunited National Party the 1948 general election.

In 1948, he was elected Chancellor of the University of Cambridge, becoming the first person from outside the United Kingdom to hold that position. He held the position until his death two years later.

He accepted the appointment as Colonel-in-Chief of Regiment Westelike Provinsie as from 17 September 1948.

In 1949, Smuts was bitterly opposed to the

In domestic policy, a number of social security reforms were carried out during Smuts's second period in office as prime minister. Old-age pensions and disability grants were extended to 'Indians' and 'Africans' in 1944 and 1947 respectively, although there were differences in the level of grants paid out based on race. The Workmen's Compensation Act of 1941 "insured all employees irrespective of payment of the levy by employers and increased the number of diseases covered by the law," and the Unemployment Insurance Act of 1946 introduced unemployment insurance on a national scale, albeit with exclusions.

Smuts continued to represent his country abroad. He was a leading guest at the 1947 wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.

At home, his preoccupation with the war had severe political repercussions in South Africa. Smuts's support of the war and his support for the Fagan Commission made him unpopular amongst the Afrikaner community and Daniel François Malan's pro-apartheid stance won the Reunited National Party the 1948 general election.

In 1948, he was elected Chancellor of the University of Cambridge, becoming the first person from outside the United Kingdom to hold that position. He held the position until his death two years later.

He accepted the appointment as Colonel-in-Chief of Regiment Westelike Provinsie as from 17 September 1948.