James Cowles Pritchard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Cowles Prichard (11 February 1786 – 23 December 1848) was a British

James Cowles Prichard (11 February 1786 – 23 December 1848) was a British

online catalogue

. Records relating to Prichard can also be found at the

Wortks at Hathi Trust

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Prichard, James Cowles 1786 births 1848 deaths People from Ross-on-Wye Alumni of the University of Edinburgh English philologists English anthropologists English people of Welsh descent British ethnologists 19th-century English medical doctors Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the Ethnological Society of London History of mental health in the United Kingdom Medical doctors from Bristol Proto-evolutionary biologists Commissioners in Lunacy

James Cowles Prichard (11 February 1786 – 23 December 1848) was a British

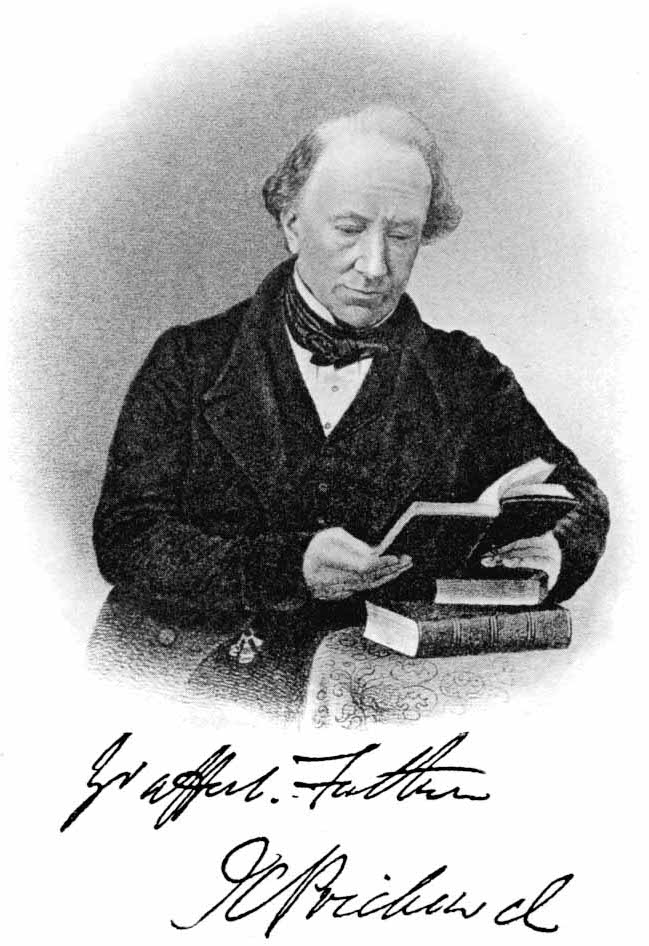

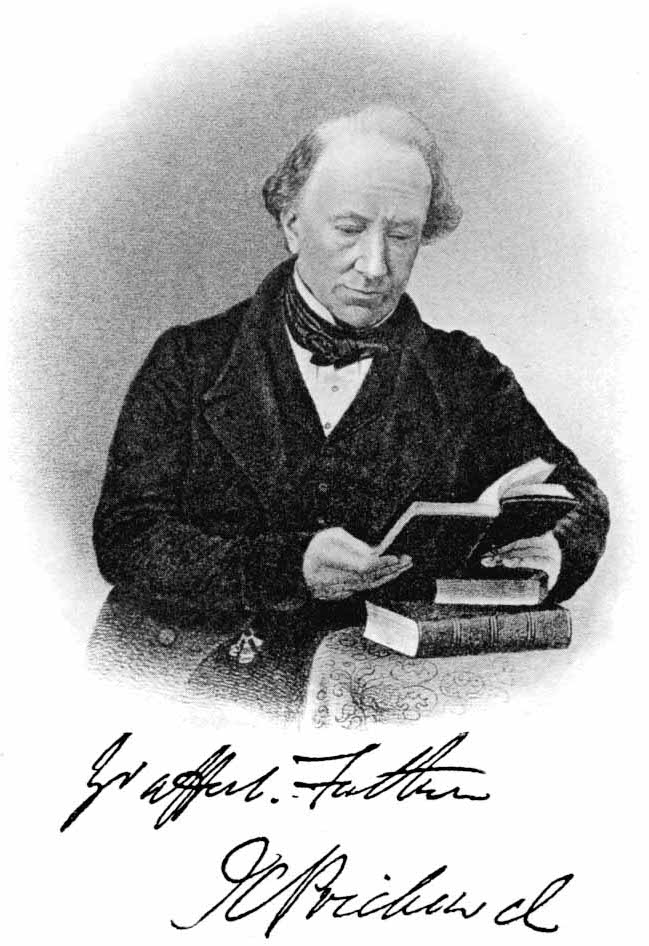

James Cowles Prichard (11 February 1786 – 23 December 1848) was a British physician

A physician, medical practitioner (British English), medical doctor, or simply doctor is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through the Medical education, study, Med ...

and ethnologist

Ethnology (from the , meaning 'nation') is an academic field and discipline that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology).

Scien ...

with broad interests in physical anthropology

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a natural science discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly from ...

and psychiatry

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of deleterious mental disorder, mental conditions. These include matters related to cognition, perceptions, Mood (psychology), mood, emotion, and behavior.

...

. His influential ''Researches into the Physical History of Mankind'' touched upon the subject of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

. From 1845, Prichard served as a Medical Commissioner in Lunacy

The Commissioners in Lunacy or Lunacy Commission was a public body established by the Lunacy Act 1845 to oversee asylums and the welfare of mentally ill people in England and Wales. It succeeded the Metropolitan Commissioners in Lunacy.

Previous ...

. He also introduced the term "senile dementia

Dementia is a syndrome associated with many neurodegenerative diseases, characterized by a general decline in cognitive abilities that affects a person's ability to perform activities of daily living, everyday activities. This typically invo ...

".Prichard J. C. 1835. ''Treatise on Insanity''. London. p. 92

Life

Prichard was born inRoss-on-Wye

Ross-on-Wye is a market town and civil parish in Herefordshire, England, near the border with Wales. It had a population estimated at 10,978 in 2021. It lies in the south-east of the county, on the River Wye and on the northern edge of the Fore ...

, Herefordshire

Herefordshire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England, bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh ...

. His parents Thomas and Mary Prichard were Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

: his mother was Welsh, and his father was of an English family who had emigrated to Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

, which had been founded by Quakers. Within a few years of his birth in Ross, Prichard's parents moved to Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, the most populous city in the region. Built around the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by t ...

, where his father now worked in the Quaker ironworks

An ironworks or iron works is an industrial plant where iron is smelted and where heavy iron and steel products are made. The term is both singular and plural, i.e. the singular of ''ironworks'' is ''ironworks''.

Ironworks succeeded bloome ...

of Harford, Partridge and Cowles. Upon his father's retirement in 1800 he returned to Ross. As a child Prichard was educated mainly at home by tutors and his father, in a range of subjects, including modern languages and general literature.Stocking 1973.

Rejecting his father's wish that he should join the ironworks business, Prichard decided upon a medical career. Here he faced the difficulty that as a Quaker he could not become a member of the Royal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians of London, commonly referred to simply as the Royal College of Physicians (RCP), is a British professional membership body dedicated to improving the practice of medicine, chiefly through the accreditation of ph ...

. Therefore, he started on apprenticeships that led to the ranks of apothecaries

''Apothecary'' () is an archaic English term for a medical professional who formulates and dispenses '' materia medica'' (medicine) to physicians, surgeons and patients. The modern terms ''pharmacist'' and, in British English, ''chemist'' have ...

and surgeons, first studying under the Quaker obstetrician Dr Thomas Pole of Bristol. Apprenticeships followed to other Quaker physicians, and to St Thomas' Hospital

St Thomas' Hospital is a large NHS teaching hospital in Central London, England. Administratively part of the Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, together with Guy's Hospital, Evelina London Children's Hospital, Royal Brompton Hospita ...

in London. In 1805, he entered medical school at Edinburgh University

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the town council under the authority of a royal charter from King James VI in 1582 and offi ...

, where his religious affiliation was no bar. Also, the Scottish medical schools were held in esteem, having contributed greatly to the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

of the previous century.

He took his M.D.

A Doctor of Medicine (abbreviated MD, from the Latin ) is a medical degree, the meaning of which varies between different jurisdictions. In the United States, and some other countries, the ''MD'' denotes a professional degree of physician. This ge ...

at Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

, his doctoral thesis of 1808 being his first attempt at the great question of his life: the origin of human varieties and races. Later, he read for a year at Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any ...

, after which came a significant personal event: he left the Society of Friends to join the established Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

. He next moved to St John's College, Oxford

St John's College is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford. Founded as a men's college in 1555, it has been coeducational since 1979.Communication from Michael Riordan, college archivist Its foun ...

, afterwards entering as a gentleman commoner

A commoner is a student at certain universities in the British Isles who historically pays for his own tuition and commons, typically contrasted with scholars and exhibitioners, who were given financial emoluments towards their fees.

Cambridge

...

at Trinity College, Oxford

Trinity College (full name: The College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity in the University of Oxford, of the foundation of Sir Thomas Pope (Knight)) is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in E ...

, but taking no degree in either university.

In 1810 Prichard settled at Bristol as a physician, eventually attaining an established position at the Bristol Infirmary

The Bristol Royal Infirmary (BRI) is a large teaching hospital in the centre of Bristol, England. It has links with the nearby University of Bristol and the Faculty of Health and Social Care at the University of the West of England, also in Brist ...

(BRI) in 1816. While working at the BRI, Prichard lived in the Red Lodge. This was also where he wrote ''Researches into the Physical History of Man''.

In 1845 he was made one of the three medical Commissioners in Lunacy

The Commissioners in Lunacy or Lunacy Commission was a public body established by the Lunacy Act 1845 to oversee asylums and the welfare of mentally ill people in England and Wales. It succeeded the Metropolitan Commissioners in Lunacy.

Previou ...

, having previously been one of the Metropolitan Commissioners, and moved to London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

. He died there three years later of rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever (RF) is an inflammation#Disorders, inflammatory disease that can involve the heart, joints, skin, and brain. The disease typically develops two to four weeks after a Streptococcal pharyngitis, streptococcal throat infection. Si ...

. At the time of his death he was president of the Ethnological Society

The Ethnological Society of London (ESL) was a learned society founded in 1843 as an offshoot of the Aborigines' Protection Society (APS). The meaning of ethnology as a discipline was not then fixed: approaches and attitudes to it changed over its ...

and a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the Fellows of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

.

Work

In 1813 he published his ''Researches into the Physical History of Man'', in two volumes, on essentially the same themes as his dissertation in 1808. The book grew until the third edition of 1836–1847 occupied five volumes. The second to the fourth editions were published under the title ''Researches into the Physical History of Mankind''. The fourth edition was also in five volumes. The central conclusion of the work is theunity of the human species

Monogenism or sometimes monogenesis is the theory of human origins which posits a common descent for all humans. The negation of monogenism is polygenism. This issue was hotly debated in the Western world in the nineteenth century, as the assumpt ...

, which has been acted upon by causes which have since divided it into permanent varieties or races. The work is dedicated to Johann Friedrich Blumenbach

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (11 May 1752 – 22 January 1840) was a German physician, naturalist, physiologist and anthropologist. He is considered to be a main founder of zoology and anthropology as comparative, scientific disciplines. He has be ...

, whose five races of man are adopted. Prichard differed from Blumenbach and other predecessors by the principle that people should be studied by combining all available characters.

Evolution

Three British men, all medically qualified and publishing between 1813 and 1819, William Lawrence,William Charles Wells

William Charles Wells (24 May 1757 – 18 September 1817) was a Scottish-American physician and printer. He lived a life of extraordinary variety, did some notable medical research, and made the first clear statement about natural selection. ...

and Prichard, addressed issues relevant to human evolution. All tackled the question of variation and race in humans; all agreed that these differences were heritable, but only Wells approached the idea of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

as a cause.

Science historian Conway Zirkle

Conway Zirkle (October 28, 1895 – March 28, 1972) was an American botanist and historian of science.

Zirkle was professor emeritus at the University of Pennsylvania. He was highly critical of Lamarckism, Lysenkoism, and Marxian biology.Jorav ...

has described Prichard as an evolutionary thinker who came very close "to explaining the origin of new forms through the operation of natural selection although he never actually stated the proposition in so many words."

Prichard indicated Africa (indirectly) as the place of human origin, in this summary passage:

:"On the whole there are many reasons which lead us to the conclusion that the primitive stock of men were probably Negroes, and I know of no argument to be set on the other side."

This opinion was omitted in later editions. The second edition includes more developed evolutionary ideas.

Anthropology

Prichard was influential in the early days ofethnology

Ethnology (from the , meaning 'nation') is an academic field and discipline that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology).

Sci ...

and anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

. He stated that the Celtic languages

The Celtic languages ( ) are a branch of the Indo-European language family, descended from the hypothetical Proto-Celtic language. The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edward Lhuyd in 1707, following Paul-Yve ...

are allied by language with the Slavonian, German and Pelasgian (Greek and Latin), thus forming a fourth European branch of Indo-European languages

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the northern Indian subcontinent, most of Europe, and the Iranian plateau with additional native branches found in regions such as Sri Lanka, the Maldives, parts of Central Asia (e. ...

. His treatise containing Celtic compared with Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; stem form ; nominal singular , ,) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in northwest South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural ...

words appeared in 1831 under the title ''Eastern Origin of the Celtic Nations''. An essay by Adolphe Pictet

Adolphe Pictet (11 September 1799 – 20 December 1875) was a Swiss linguist, philologist and ethnologist.

Pictet, the cousin of the biologist Francois Jules Pictet, is well known for his research in the field of comparative linguistics. He ...

, which made its author's reputation, was published independently of the earlier investigations of Prichard.

In 1843 Prichard published his ''Natural History of Man'', in which he reiterated his belief in the specific unity of man

Monogenism or sometimes monogenesis is the theory of human origins which posits a common descent for all humans. The negation of monogenism is polygenism. This issue was hotly debated in the Western world in the nineteenth century, as the assumpt ...

, pointing out that the same inward and mental nature can be recognized in all the races. Prichard was an early member of the Aborigines' Protection Society

The Aborigines' Protection Society (APS) was an international human rights organisation founded in 1837,

...

.

...

Psychiatry

In medicine, he specialised in what is nowpsychiatry

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of deleterious mental disorder, mental conditions. These include matters related to cognition, perceptions, Mood (psychology), mood, emotion, and behavior.

...

. In 1822 he published ''A Treatise on Diseases of the Nervous System'' (pt. I), and in 1835 a ''Treatise on Insanity and Other Disorders Affecting the Mind'', in which he advanced the theory of the existence of a distinct mental illness

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness, a mental health condition, or a psychiatric disability, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. A mental disorder is ...

called moral insanity

Moral insanity referred to a type of mental disorder consisting of abnormal emotions and behaviours in the apparent absence of intellectual impairments, delusions, or hallucinations. It was an accepted diagnosis in Europe and America through the s ...

. Prichard's work was also the first definition of senile dementia in the English language

English is a West Germanic language that developed in early medieval England and has since become a English as a lingua franca, global lingua franca. The namesake of the language is the Angles (tribe), Angles, one of the Germanic peoples th ...

. Augstein has suggested that these works were aimed at the prevalent materialist theories of mind, phrenology

Phrenology is a pseudoscience that involves the measurement of bumps on the skull to predict mental traits. It is based on the concept that the Human brain, brain is the organ of the mind, and that certain brain areas have localized, specific ...

and craniology

Phrenology is a pseudoscience that involves the measurement of bumps on the skull to predict mental traits. It is based on the concept that the brain is the organ of the mind, and that certain brain areas have localized, specific functions or ...

. She has also suggested that Prichard was influenced by the somatic school

Somatic school may refer to those in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who argued for a biological (as opposed to psychological) etiology of insanity; or it may refer to a group of nineteenth-century German psychiatrists, including Carl ...

of German Romantic psychiatric thought, in particular Christian Friedrich Nasse

Christian Friedrich Nasse (18 April 1778 – 18 April 1851) was a German physician and psychiatrist born in Bielefeld.

He studied medicine at the University of Halle under physiologist Johann Christian Reil (1759–1813). At Halle, Achim von Arn ...

, and (eclectically) Johann Christian August Heinroth

Johann Christian August Heinroth (17 January 1773 – 26 October 1843) was a German physician and psychologist who was the first to use the term psychosomatic. Heinroth divided the human personality into three components in the 1800s, describing ...

; this in addition to an acknowledged debt to Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol

Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol (3 February 1772 – 12 December 1840) was a French psychiatrist.

Early life and education

Born and raised in Toulouse, Esquirol completed his education at Montpellier. He came to Paris in 1799 where he worked a ...

.

In 1842, following up on moral insanity, he published ''On the Different Forms of Insanity in Relation to Jurisprudence, designed for the use of persons concerned in legal questions regarding unsoundness of mind''.

Other works

Among his other works were: *1819: ''Analysis of Egyptian Mythology'' *1829: ''A Review of the Doctrine of a Vital Principle'' *1831: ''On the Treatment ofHemiplegia

Hemiparesis, also called unilateral paresis, is the weakness of one entire side of the body ('' hemi-'' means "half"). Hemiplegia, in its most severe form, is the complete paralysis of one entire side of the body. Either hemiparesis or hemiplegia ...

''

*1839: ''On the Extinction of some Varieties of the Human Race''

Family

He married Anne Maria Estlin, daughter ofJohn Prior Estlin

John Prior Estlin (1747–1817) was an English Unitarian minister. He was noted as a teacher, and for his connections in literary circles.

Life

He was born at Hinckley, Leicestershire, 9 April (O.S.) 1747, and was the son of Thomas Estlin, hosie ...

and sister of John Bishop Estlin

John Bishop Estlin (26 December 1785 – 10 June 1855) was an English ophthalmic surgeon.

Life

Estlin was the son of the Unitarianism, Unitarian minister John Prior Estlin, who kept a well-known school in a large house at the top of St. Michael' ...

. They had ten children, eight of whom survived infancy, including Augustin Prichard (b. 1818, d. 1898), Constantine Estlin Prichard (b.1820), Theodore Joseph Prichard (b.1821), Illtiodus Thomas Prichard (b. 1825), Edith Prichard (b. 1829) and Albert Herman Prichard (b.1831).

Archives

Documents including medical certificates relating to Prichard and his second son, Augustin Prichard, are held atBristol Archives

Bristol Archives (formerly Bristol Record Office) was established in 1924. It was the first borough record office in the United Kingdom, since at that time there was only one other local authority record office (Bedfordshire Record Office, Bedf ...

(Ref. 16082)online catalogue

. Records relating to Prichard can also be found at the

Wellcome Library

The Wellcome Library is a free library and Museum based in central London. It was developed from the collection formed by Sir Henry Wellcome (1853–1936), whose personal wealth allowed him to create one of the most ambitious collections of the ...

and the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

.

References

Notes

Sources

*Augstein, Hannah Franziska. ''James Cowles Prichard's Anthropology: remaking the science of Man in early nineteenth-century Britain''. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1999. ; (pbk) *Sera-Shriar, Efram, ''The Making of British Anthropology, 1813-1871'', London: Pickering and Chatto, 2013, pp. 21–52. *''Memoir'' by Dr Thomas Hodgkin (1798–1866) in ''Journal of the Ethnological Society'' (1849). *''Memoir'' byJohn Addington Symonds

John Addington Symonds Jr. (; 5 October 1840 – 19 April 1893) was an English poet and literary critic. A cultural historian, he was known for his work on the Renaissance, as well as numerous biographies of writers and artists. Although mar ...

, ''Journal of the Ethnological Society'' (1850).

* Prichard and Symonds in ''Special Relation to Mental Science'', by Daniel Hack Tuke

Daniel Hack Tuke (19 April 18275 March 1895) was an English physician and expert on mental illness.

Family

Tuke came from a long line of Quakers from York who were interested in mental illness and concerned with those afflicted. His great-gra ...

(1891).

* Stocking, George W. Jr 1973. "From chronology to ethnology: James Cowles Prichard and British Anthropology 1800–1850". Introduction to the reprint of ''Researches into the Physical History of Man, 1st ed 1813''. Chicago, 1973.

* Symonds, John Addington 1871. "On the life, writings and character of the late James Cowles Prichard". In ''Miscellanies ... of Symonds'', edited by his son, London: Macmillan.

*

External links

Wortks at Hathi Trust

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Prichard, James Cowles 1786 births 1848 deaths People from Ross-on-Wye Alumni of the University of Edinburgh English philologists English anthropologists English people of Welsh descent British ethnologists 19th-century English medical doctors Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the Ethnological Society of London History of mental health in the United Kingdom Medical doctors from Bristol Proto-evolutionary biologists Commissioners in Lunacy