Jakob Henle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

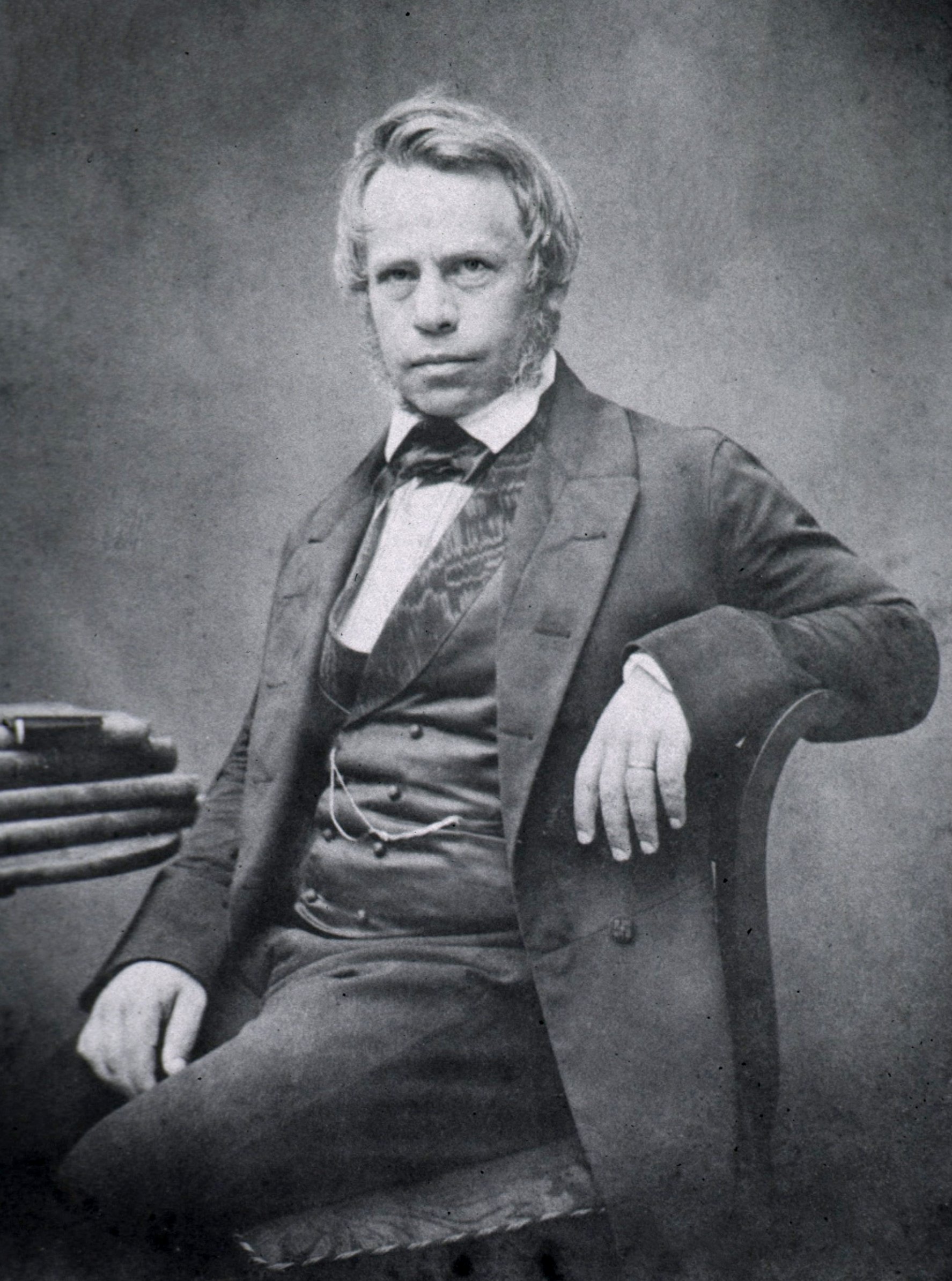

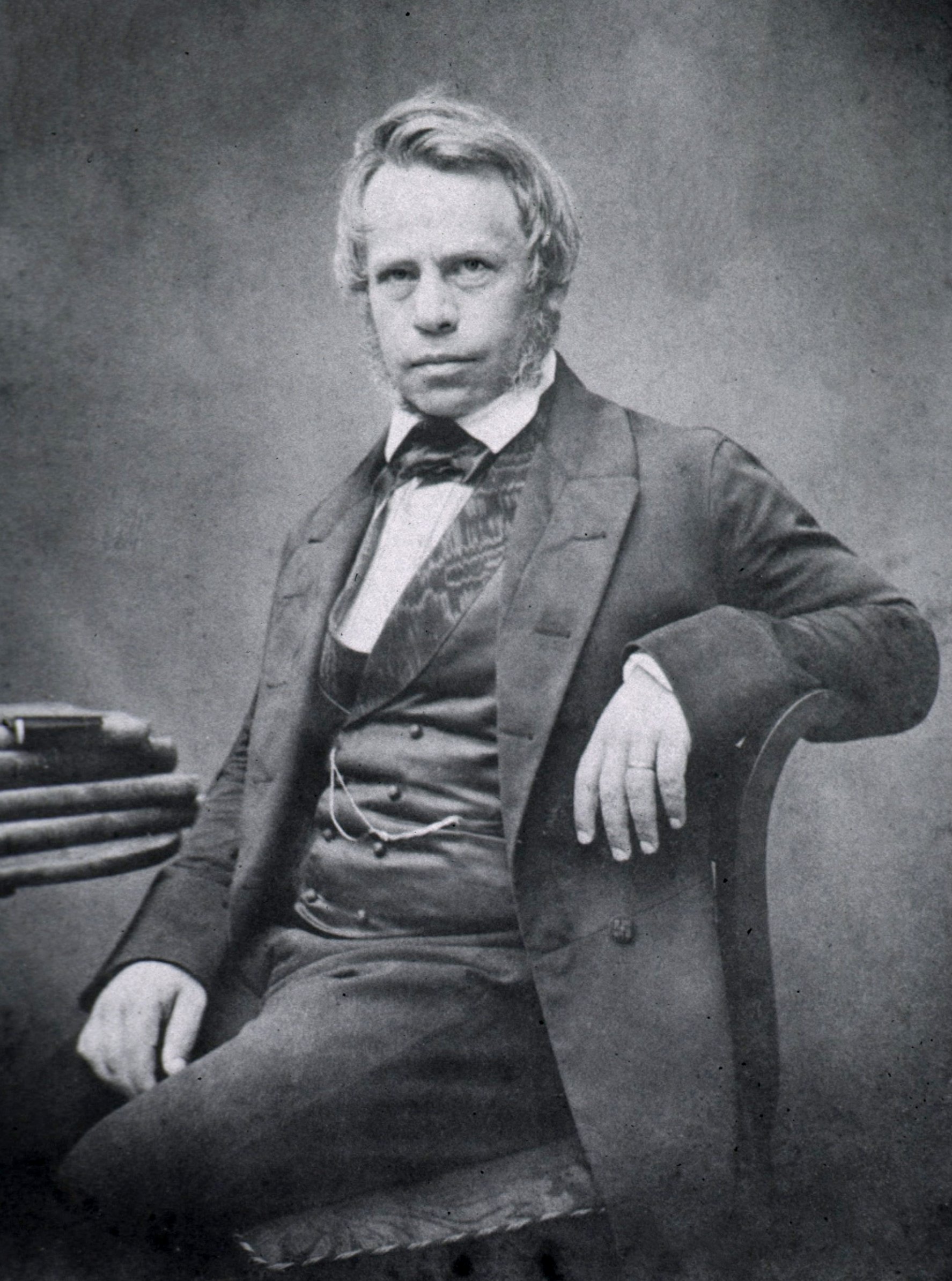

Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle (; 9 July 1809 – 13 May 1885) was a German physician,

Henle was born in

Henle was born in

doi:10.2307/3277766

/ref> In 1852, he moved to

''Allgemeine Anatomie: Lehre von den Mischungs- und Formbestandtheilen des menschlichen Körpers''

(1841) * ''Handbuch der rationellen Pathologie'' (1846–1853) * ''Handbuch der systematischen Anatomie des Menschen'' (1855–1871) * ''Vergleichend-anatomische Beschreibung des Kehlkopfes mit besonderer Berücksichtigung des Kehlkopfes der Reptilien'' (1839) * ''Pathologische Untersuchungen'' (1840) * ''Zur Anatomie der Niere'' (1863)

Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle Details

WhoNamedIt.

Biography and bibliography

in the

pathologist

Pathology is the study of disease. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in the context of modern medical treatme ...

, and anatomist

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old scien ...

. He is credited with the discovery of the loop of Henle

In the kidney, the loop of Henle () (or Henle's loop, Henle loop, nephron loop or its Latin counterpart ''ansa nephroni'') is the portion of a nephron that leads from the proximal convoluted tubule to the distal convoluted tubule. Named after it ...

in the kidney

In humans, the kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped blood-filtering organ (anatomy), organs that are a multilobar, multipapillary form of mammalian kidneys, usually without signs of external lobulation. They are located on the left and rig ...

. His essay, "On Miasma and Contagia," was an early argument for the germ theory of disease

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted scientific theory for many diseases. It states that microorganisms known as pathogens or "germs" can cause disease. These small organisms, which are too small to be seen without magnification, ...

. He was an important figure in the development of modern medicine.

Biography

Henle was born in

Henle was born in Fürth

Fürth (; East Franconian German, East Franconian: ; ) is a List of cities and towns in Germany, city in northern Bavaria, Germany, in the administrative division (''Regierungsbezirk'') of Middle Franconia.

It is the Franconia#Towns and cities, s ...

, Bavaria, to Simon and Rachel Diesbach Henle (Hähnlein). He was Jewish. After studying medicine at Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; ; ) is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, fifth-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, and with a population of about 163,000, of which roughly a quarter consists of studen ...

and at Bonn

Bonn () is a federal city in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, located on the banks of the Rhine. With a population exceeding 300,000, it lies about south-southeast of Cologne, in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ruhr region. This ...

, where he took his doctor's degree in 1832, he became prosector in anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old scien ...

to Johannes Müller at Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

. During the six years he spent in that position he published a large amount of work, including three anatomical monographs on new species of animals and papers on the structure of the lymphatic system

The lymphatic system, or lymphoid system, is an organ system in vertebrates that is part of the immune system and complementary to the circulatory system. It consists of a large network of lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, lymphoid organs, lympha ...

, the distribution of epithelium

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is a thin, continuous, protective layer of cells with little extracellular matrix. An example is the epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin. Epithelial ( mesothelial) tissues line the outer surfaces of man ...

in the human body, the structure and development of the hair, and the formation of mucus

Mucus (, ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both Serous fluid, serous and muc ...

and pus

Pus is an exudate, typically white-yellow, yellow, or yellow-brown, formed at the site of inflammation during infections, regardless of cause. An accumulation of pus in an enclosed tissue space is known as an abscess, whereas a visible collect ...

. He also developed a friendship with another assistant of Müller, Theodor Schwann

Theodor Schwann (; 7 December 181011 January 1882) was a German physician and physiology, physiologist. His most significant contribution to biology is considered to be the extension of cell theory to animals. Other contributions include the d ...

, which later became famous for his cell theory

In biology, cell theory is a scientific theory first formulated in the mid-nineteenth century, that living organisms are made up of cells, that they are the basic structural/organizational unit of all organisms, and that all cells come from pr ...

.

In 1840, he accepted the chair of anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old scien ...

at Zürich

Zurich (; ) is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich. , the municipality had 448,664 inhabitants. The ...

and in 1844 he was called to Heidelberg, where he taught anatomy, physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

, and pathology

Pathology is the study of disease. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in the context of modern medical treatme ...

. About this period he was engaged on delineating his complete system of general anatomy, which formed the sixth volume of the new edition of Samuel Thomas von Sömmering

Samuel is a figure who, in the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, plays a key role in the transition from the biblical judges to the Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy), United Kingdom of Israel under Saul, and again in the monarchy's transition ...

's treatise, published at Leipzig

Leipzig (, ; ; Upper Saxon: ; ) is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Saxony. The city has a population of 628,718 inhabitants as of 2023. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, eighth-largest city in Ge ...

between 1841 and 1844. While at Heidelberg he published a zoological monograph on the shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch cartilaginous fish characterized by a ribless endoskeleton, dermal denticles, five to seven gill slits on each side, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the ...

s and rays, in conjunction with his master Müller, and in 1846 his famous ''Manual of Rational Pathology'' began to appear; this marked the beginning of a new era in pathological study, since in it physiology and pathology were treated, in Henle's own words, as branches of one science, and the facts of disease were systematically considered with reference to their physiological relations.

In 1841, Henle was the first to observe microscopic mites residing in human hair follicles. Although he did not formally describe them, his student Gustav Simon later identified and described these organisms in 1842, naming them ''Acarus folliculorum'' (now known as ''Demodex folliculorum

''Demodex folliculorum'' is a microscopic mite that can survive only on the skin of humans. Most people host ''D.folliculorum'' on their skin particularly on the face, where sebaceous glands are most concentrated. Usually, the mites do not caus ...

''). This early observation laid the groundwork for future research into the role of ''Demodex'' mites in dermatological conditions.Desch, C.E., & Nutting, W.B. (1972). "The genus Demodex: A review." ''The Journal of Parasitology'', 58(1), 169–170doi:10.2307/3277766

/ref> In 1852, he moved to

Göttingen

Göttingen (, ; ; ) is a college town, university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the Capital (political), capital of Göttingen (district), the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. According to the 2022 German census, t ...

, whence he issued three years later the first instalment of his great ''Handbook of Systematic Human Anatomy'', the last volume of which was not published until 1873. This work was perhaps the most complete and comprehensive of its kind at that time, and it was remarkable not only for the fullness and minuteness of its anatomical descriptions but also for the number and excellence of the illustrations with which they elucidated minute anatomy of the blood vessels, serous membrane

The serous membrane (or serosa) is a smooth epithelial membrane of mesothelium lining the contents and inner walls of body cavity, body cavities, which secrete serous fluid to allow lubricated sliding (motion), sliding movements between opposing ...

s, kidney

In humans, the kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped blood-filtering organ (anatomy), organs that are a multilobar, multipapillary form of mammalian kidneys, usually without signs of external lobulation. They are located on the left and rig ...

, eye, nails, central nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain, spinal cord and retina. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity o ...

, etc. He discovered the loop of Henle

In the kidney, the loop of Henle () (or Henle's loop, Henle loop, nephron loop or its Latin counterpart ''ansa nephroni'') is the portion of a nephron that leads from the proximal convoluted tubule to the distal convoluted tubule. Named after it ...

and Henle's tubules, two anatomical structures in the kidney.

Other anatomical and pathological findings associated with his name are:

* Crypts of Henle: microscopic pockets located in the conjunctiva

In the anatomy of the eye, the conjunctiva (: conjunctivae) is a thin mucous membrane that lines the inside of the eyelids and covers the sclera (the white of the eye). It is composed of non-keratinized, stratified squamous epithelium with gobl ...

of the eye.

* Hassall–Henle bodies: transparent growths in the periphery of the Descemet's membrane

Descemet's membrane ( or the Descemet membrane) is the basement membrane that lies between the corneal proper substance, also called stroma, and the endothelial layer of the cornea. It is composed of different kinds of collagen (Type IV and VIII ...

of the eye.

* Henle's fissure: fibrous tissue between the cardiac muscle

Cardiac muscle (also called heart muscle or myocardium) is one of three types of vertebrate muscle tissues, the others being skeletal muscle and smooth muscle. It is an involuntary, striated muscle that constitutes the main tissue of the wall o ...

fibers.

* Henle's ampulla: ampulla of the uterine tube.

* Henle's layer: outer layer of cells of root sheath of a hair follicle.

* Henle's ligament: tendon

A tendon or sinew is a tough band of fibrous connective tissue, dense fibrous connective tissue that connects skeletal muscle, muscle to bone. It sends the mechanical forces of muscle contraction to the skeletal system, while withstanding tensi ...

of the transversus abdominis muscle

The transverse abdominal muscle (TVA), also known as the transverse abdominis, transversalis muscle and transversus abdominis muscle, is a muscle layer of the anterior and lateral (front and side) abdominal wall, deep to (layered below) the inter ...

.

* Henle's membrane: Bruch's layer forming inner boundary of the choroid

The choroid, also known as the choroidea or choroid coat, is a part of the uvea, the vascular layer of the eye. It contains connective tissues, and lies between the retina and the sclera. The human choroid is thickest at the far extreme rear o ...

of the eye.

* Henle's sheath: connective tissue which supports outer layer of nerve fibres in a funiculus.

* Henle's spine: the supra-meateal spine that serves as a landmark in the mastoid

The mastoid part of the temporal bone is the posterior (back) part of the temporal bone, one of the bones of the skull. Its rough surface gives attachment to various muscles (via tendons) and it has openings for blood vessels. From its borders, t ...

area.

* Glands of Henle: depressions in the eye in which epithelial cells accumulate in cases of cicatrial trachoma.

* Tubes of Henle: numerous tiny tubes connecting the choroid to retina, carrying vessels and nerves.

Henle developed the concepts of contagium vivum and contagium animatum, respectively (''Von den Miasmen und Kontagien'', 1840) – thereby following ideas of Girolamo Fracastoro and the work of Agostino Bassi

Agostino Bassi, sometimes called de Lodi (25 September 1773 – 8 February 1856), was an Italian entomologist. He preceded Louis Pasteur in the discovery that microorganisms can be the cause of disease (the germ theory of disease). He discovere ...

; thus co-founding the theory of microorganisms as the cause of infective diseases. He did not find a special species of bacteria himself – this was achieved by his student Robert Koch

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch ( ; ; 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera and anthrax, he i ...

. Those two put up the fundamental rules of cleanly defining disease-causing microbes: the Henle Koch postulates.

In 1870, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences () is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special responsibility for promoting nat ...

. He died in Göttingen

Göttingen (, ; ; ) is a college town, university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the Capital (political), capital of Göttingen (district), the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. According to the 2022 German census, t ...

on 13 May 1885.

Bibliography

* ''Ueber die Ausbreitung des Epithelium im menschlichen Körper'' (1838)''Allgemeine Anatomie: Lehre von den Mischungs- und Formbestandtheilen des menschlichen Körpers''

(1841) * ''Handbuch der rationellen Pathologie'' (1846–1853) * ''Handbuch der systematischen Anatomie des Menschen'' (1855–1871) * ''Vergleichend-anatomische Beschreibung des Kehlkopfes mit besonderer Berücksichtigung des Kehlkopfes der Reptilien'' (1839) * ''Pathologische Untersuchungen'' (1840) * ''Zur Anatomie der Niere'' (1863)

See also

* :Taxa named by Friedrich Gustav Jakob HenleReferences

;AttributionExternal links

* NeurotreeFriedrich Gustav Jakob Henle Details

WhoNamedIt.

Biography and bibliography

in the

Virtual Laboratory The online project Virtual Laboratory. Essays and Resources on the Experimentalization of Life, 1830-1930, located at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, is dedicated to research in the history of the experimentalization of life. T ...

of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

The Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (German: Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte) is a scientific research institute founded in March 1994. It is dedicated to addressing fundamental questions of the history of knowled ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Henle, Friedrich Gustav Jakob

Physicians from Bavaria

German taxonomists

1809 births

1885 deaths

German anatomists

German pathologists

19th-century German Jews

Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

University of Bonn alumni

People from Fürth

Physicians from the Kingdom of Bavaria

Jewish German scientists

Physicians of the Charité