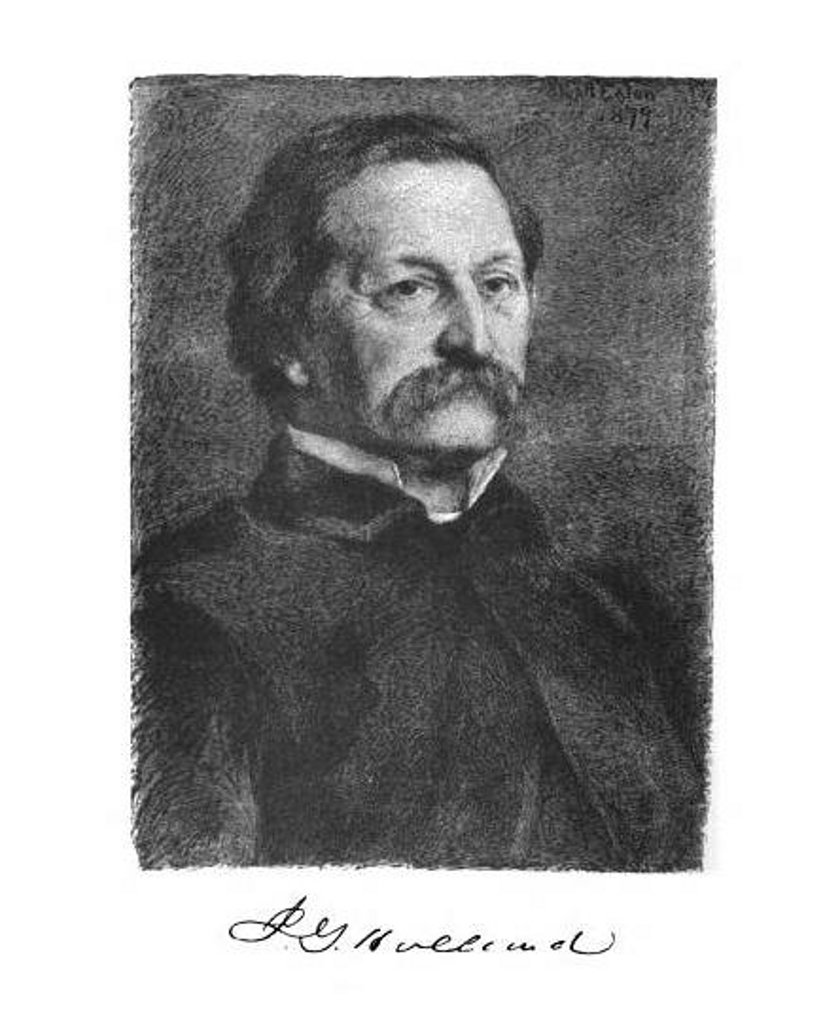

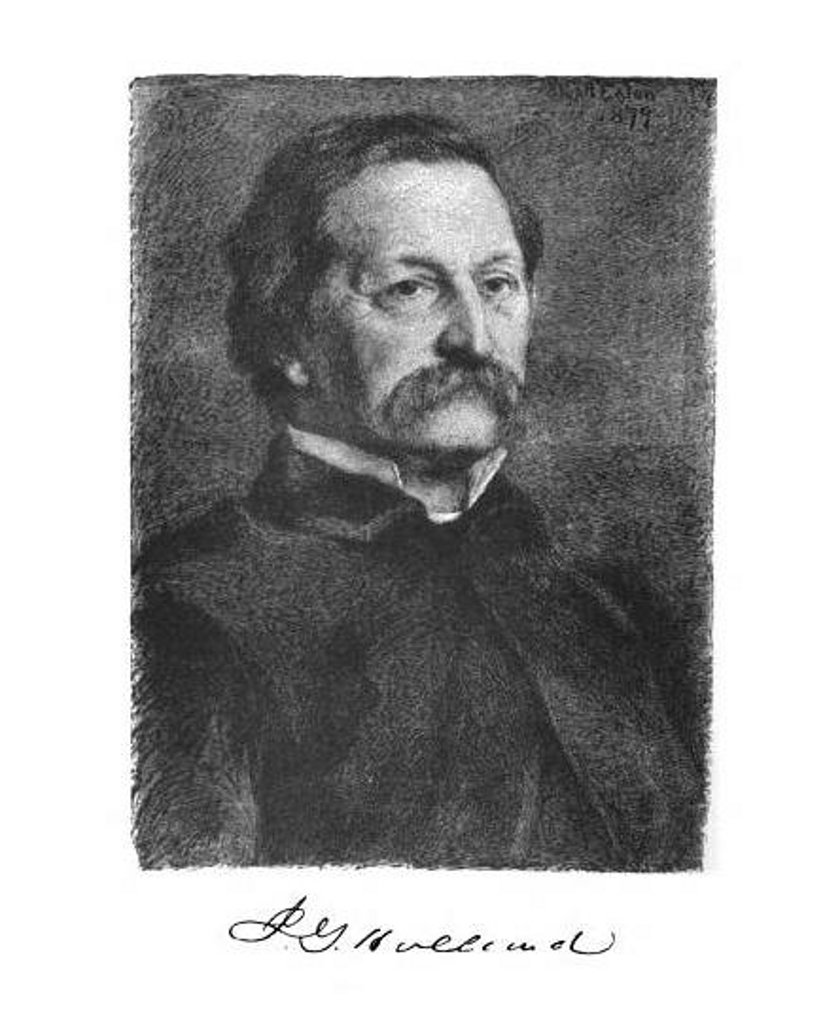

J. G. Holland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Josiah Gilbert Holland (July 24, 1819 – October 12, 1881) was an American novelist, essayist, poet and spiritual mentor to the Nation in the years following the

writings

are quoted by politicians and pastors alike though few today recognize Holland’s name.

silk machine

was used in China but he received little or no return. He moved the family every year or two:

Gold-Foil: Hammered from Popular Proverbs

' under his Timothy Titcomb pen name came out in 1859. He published his second novel,

Miss Gilbert‘s Career: An American Story

', in 1860. It is considered one of the first novels of

Lessons in Life: A Series of Familiar Essays

' (1861). In 1862, he erected an opulent home in the

Sevenoaks

' (1875), and ''Nicholas Minturn'' (1877), which first were serialized in

Bonnie Castle Resort & Marina

today.

The Life of Abraham Lincoln

(1866) * Kathrina: Her Life and Mine, in a poem, (1867) * Christ And The Twelve: Or Scenes and Events in the Life of Our Saviour and His Apostles, as Painted by the Poets (1867) * The Marble Prophecy, And Other Poems (1872) * Garnered Sheaves: The Complete Poetical Works (1872) * Illustrated Library of Favorite Song: Based upon folk songs, and comprising songs of the heart, songs of home, songs of life, and songs of nature (1872) * Plain Talks On Familiar Subjects: A Series of Popular Lectures (1872) * Arthur Bonnicastle: An American Novel (1873) * The Mistress of the Manse: A Poem (1874) * The Story of Sevenoaks: A Story of To-Day (1875) * Nicholas Minturn: A Study in a Story (1876) * Every-Day Topics: A Book of Briefs (1876) First series * The Puritan’s Guest, And Other Poems (1881) * Concerning the Jones Family (1881) (revised from the 1863 book) * Every-Day Topics: A Book of Briefs (1882) Second series

Stone House Museum

which also displays first editions of his works.

''History of Western Massachusetts''

which was published as a book the following year.

jasm

�� first appears in Holland’s 1860 novel, Miss Gilbert's Career: “‘She's just like her mother... Oh! she’s just as full of jasm!’.. ‘Now tell me what jasm is.’.. ‘If you'll take thunder and lightening ic and a steamboat and a buzz-saw, and mix 'em up, and put 'em into a woman, that's jasm.’” The word was used to describe the "inexpressible personal force of the

Bitter-Sweet

�� would become one of his most popular, and was described in 1894, by biographer Harriette Merrick Plunkett, as,

sentence or paragraph

is still quoted by politicians, artists and spiritual leaders alike, including

Sevenoaks

' (1875) was adapted into the

novel

��appears as a character in the 2023 film Killers of the Flower Moon.

Critical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to Her Life and Work

United States, Facts On File, Incorporated, 2007. (Mass ), Springfield

The Nation Weeping for Its Dead: Observances at Springfield, Massachusetts, on President Lincoln's Funeral Day, Wednesday, April 19, 1865, Including Dr. Holland's Eulogy.

* Mead, Carl David. Yankee Eloquence in the Middle West: The Ohio Lyceum, 1850-1870. United States, Michigan State College Press, 1951. * Meyer, Rose D.. Authors Digest: The World's Great Stories in Brief. United States, Issued under the auspices of the Authors Press, 1927. A five-page briefing on Holland’s novel

Sevenoaks

'. * Morgan, Robert J.. Then Sings My Soul Special Edition: 150 Christmas, Easter, and All-Time Favorite Hymn Stories. United States, Thomas Nelson, 2022. *

Holland Collection of Literary Letters, University of Colorado Boulder

Titcomb’s Letters to Young People, Single and Married

* Plunkett, Harriette Merrick. Josiah Gilbert Holland. United States, C. Scribner's Sons, 1894

Short audio essay, "A Serendipitous Encounter With The Ghost Of A Once-Famous Belchertonian," about Josiah Gilbert Holland

* C. Scribner's & Sons published Holland’s Complete Works in a 16-volume set that may be found online a

HathiTrust

*All of his published books may be found online a

HathiTrust

*His papers are collected at th

New York Public Library

and a

The Archives at Yale

*Much o

his work

remains in print by classic reprinting publishers {{DEFAULTSORT:Holland, Josiah Gilbert 19th-century American novelists American male novelists American magazine editors Novelists from Massachusetts 1819 births 1881 deaths Massachusetts Republicans American male poets 19th-century American poets 19th-century American journalists American male journalists Berkshire Medical College alumni 19th-century American male writers Biographers of Abraham Lincoln American male biographers Writers from Springfield, Massachusetts Poets from Springfield, Massachusetts

Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

. Born in Western Massachusetts

Western Massachusetts, known colloquially as "western Mass," is a region in Massachusetts, one of the six U.S. states that make up the New England region of the United States. Western Massachusetts has diverse topography; 22 colleges and univ ...

, he was “the most successful man of letters in the United States” in the latter half of the nineteenth century and sold more books in his lifetime than Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, and essayist. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced," with William Fau ...

did in his.

Known by his initials “J.G.,” Holland penned the first biography of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

, just months after his assassination, which was a bestseller, and he published the first known poem written by an African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

. One of Holland’s novels was among the earliest examples of the genre that became literary realism

Literary realism is a movement and genre of literature that attempts to represent mundane and ordinary subject-matter in a faithful and straightforward way, avoiding grandiose or exotic subject-matter, exaggerated portrayals, and speculative ele ...

and he published a few poems of Emily Dickinson

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson (December 10, 1830 – May 15, 1886) was an American poet. Little-known during her life, she has since been regarded as one of the most important figures in American poetry. Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massac ...

’s in the newspaper

A newspaper is a Periodical literature, periodical publication containing written News, information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray background. Newspapers can cover a wide variety of fields such as poli ...

that he edited. Holland and his wife, Elizabeth Luna Chapin, were close friends with her.

Holland became a popular Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Basic science and some introduction to ...

lecturer and wrote advice essay

An essay ( ) is, generally, a piece of writing that gives the author's own argument, but the definition is vague, overlapping with those of a Letter (message), letter, a term paper, paper, an article (publishing), article, a pamphlet, and a s ...

s under the pseudonym Timothy Titcomb. He composed lyrics to hymns, such as the beloved Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christianity, Christian Christian tradition, tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother ...

Christmas tune " There's a Song in the Air,” which was published worldwide including translations into Tagalog

Tagalog may refer to:

Language

* Tagalog language, a language spoken in the Philippines

** Old Tagalog, an archaic form of the language

** Batangas Tagalog, a dialect of the language

* Tagalog script, the writing system historically used for Tagal ...

and Belarusian

Belarusian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to Belarus

* Belarusians, people from Belarus, or of Belarusian descent

* A citizen of Belarus, see Demographics of Belarus

* Belarusian language

* Belarusian culture

* Belarusian cuisine

* Byelor ...

. He helped establish, and was editor of, the middle-class flagship magazine ''Scribner's Monthly

''Scribner's Monthly: An Illustrated Magazine for the People'' was an illustrated American literary periodical published from 1870 until 1881. Following a change in ownership in 1881 of the company that had produced it, the magazine was relaunc ...

''.

Though Holland was a contemporary of the canonical

The adjective canonical is applied in many contexts to mean 'according to the canon' the standard, rule or primary source that is accepted as authoritative for the body of knowledge or literature in that context. In mathematics, ''canonical exampl ...

and more renowned poet Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman Jr. (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist, and journalist; he also wrote two novels. He is considered one of the most influential poets in American literature and world literature. Whitman incor ...

and the novelist Herman Melville

Herman Melville (Name change, born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance (literature), American Renaissance period. Among his best-known works ar ...

, neither men “ever tasted the sweets of success as Holland did, perhaps, because neither wrote what the nation’s readers cared so much about.” Hiwritings

are quoted by politicians and pastors alike though few today recognize Holland’s name.

Birth

He was born in a low-slung bungalow, built of logs, in aglade

Glade may refer to:

Places in the United States

*Glade, Kansas, a city in Phillips County

* Glade, Ohio, an unincorporated community in Jackson County

*Glades County, Florida, in south central Florida

*Glade Spring, Virginia, a town in Washington ...

along the Hop Brook, near the intersection of Federal Street and Orchard Road, in the village of Dwight Dwight may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Dwight (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Dwight (surname), a list of people

Places Canada

* Dwight, Ontario, village in the township of Lake of Bays, Ontario

...

, in Belchertown, Massachusetts

Belchertown (previously known as Cold Spring and Belcher's Town) is a New England town, town in Hampshire County, Massachusetts, Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States. It is part of the Springfield, Massachusetts Springfield metropol ...

, on July 24, 1819.

His birthplace, once frequented by admirers, is to the immediate southwest of the Holland Glen Conservation Area, which was named for him in the early 20th century. Today it encompasses 290 acres, part of an old-growth forest

An old-growth forest or primary forest is a forest that has developed over a long period of time without disturbance. Due to this, old-growth forests exhibit unique ecological features. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Natio ...

, with steep hillsides, waterfalls, vistas and hiking trails.

His mother Anna's family, the Gilberts, from Hebron, Connecticut

Hebron ( ) is a New England town, town in Tolland County, Connecticut, United States. The town is part of the Capitol Planning Region, Connecticut, Capitol Planning Region. The population was 9,098 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. ...

, arrived to North Belchertown by 1799 and operated an inn on the Bay Road not far from his birthplace (the home remains at 111 Old Bay Road). Josiah Gilbert Holland was likely named for his mother's younger brother, Josiah Gilbert, who died, at age 27, a few months after Holland's birth.

Holland grew up in a poor family struggling to make ends meet. Young Josiah spent only a few years at the farmhouse at Dwight Dwight may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Dwight (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Dwight (surname), a list of people

Places Canada

* Dwight, Ontario, village in the township of Lake of Bays, Ontario

...

and later quipped that he’d like to “burn it to the ground.” His wish came true, in fact, a few years before his own death, when someone intentionally set the old cottage on fire in 1876.

Josiah was the middle of seven children (a brother died at age 3) and his parents were deeply religious and evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

, from pious Puritan stock. He was often called by his middle name, Gilbert, throughout his life by family members and intimates. His great-uncle Jonas Holland came to Belchertown from nearby Petersham in 1795 followed by his paternal uncles, Luther and Park, and his father. His uncle Luther manufactured, in Belchertown, the first horizontal pump fire engine made in the United States (his great-uncle Luther began building fire engines at Petersham).

Josiah's parents were married in 1810 by the "venerable" Belchertown pastor Justus Forward, of New England vampire panic notoriety and who assiduously cataloged the vital records of Belchertown inhabitants for half a century. His parents converted to Congregationalism

Congregationalism (also Congregational Churches or Congregationalist Churches) is a Reformed Christian (Calvinist) tradition of Protestant Christianity in which churches practice congregational government. Each congregation independently a ...

in 1813, part of the evangelical furor brought on by the Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the late 18th to early 19th century in the United States. It spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching and sparked a number of reform movements. Revivals were a k ...

.

Josiah's father Harrison painted the first wagon manufactured in Belchertown, which became a center of the carriage trade in the United States. It was called "Warner's butterfly." Harrison Holland likely erected a small stone mill for a carding machine

In textile production, carding is a mechanical process that disentangles, cleans and intermixes fibres to produce a continuous web or sliver suitable for subsequent processing. This is achieved by passing the fibres between differentially movi ...

along a brook from Holland Pond, near the farm on which Josiah was born. There was little money to be earned: carding was transitioning to the larger factory mills at this time. The mill was later converted into a powder mill.

Harrison was what biographers called a "failed inventor;" his patentesilk machine

was used in China but he received little or no return. He moved the family every year or two:

Heath

A heath () is a shrubland habitat found mainly on free-draining infertile, acidic soils and is characterised by open, low-growing woody vegetation. Moorland is generally related to high-ground heaths with—especially in Great Britain—a coole ...

, back to Belchertown, South Hadley

South Hadley (, ) is a town in Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 18,150 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Springfield metropolitan area, Massachusetts.

South Hadley is home to Mount Holyoke College, South ...

, Granby and Northampton

Northampton ( ) is a town and civil parish in Northamptonshire, England. It is the county town of Northamptonshire and the administrative centre of the Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority of West Northamptonshire. The town is sit ...

. "He was always inventing ingenious trifles," a biography states. "And sometimes made verses, and held the fatuously sanguine view that some other place and some distant morrow held a boon and blessing denied to the here and now." Josiah G. Holland later loosely based characters in several of his novels on his father.

Josiah worked in a factory to help the family. He then spent a short time studying at Northampton

Northampton ( ) is a town and civil parish in Northamptonshire, England. It is the county town of Northamptonshire and the administrative centre of the Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority of West Northamptonshire. The town is sit ...

High School

A secondary school, high school, or senior school, is an institution that provides secondary education. Some secondary schools provide both ''lower secondary education'' (ages 11 to 14) and ''upper secondary education'' (ages 14 to 18), i.e., ...

before withdrawing due to ill health. He tried daguerreotypy

Daguerreotype was the first publicly available photographic process, widely used during the 1840s and 1850s. "Daguerreotype" also refers to an image created through this process.

Invented by Louis Daguerre and introduced worldwide in 1839, th ...

and taught penmanship from town to town, reciting "his own poems to his intimate friends." Between 1842 and 1843, three of Josiah's sisters died, Clarissa, Louisa and Lucretia, which had a profound impact upon him. He then saved enough money to study medicine at Berkshire Medical College

Berkshire Medical College (originally the Berkshire Medical Institution, and sometimes referred to as Berkshire Medical College) was a medical school in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. It is notable for establishing the first professorship in mental ...

, where he took a degree in 1843.

Hoping to become a successful physician, he began a medical practice with classmate Dr. Charles Bailey in Springfield, Massachusetts

Springfield is the most populous city in Hampden County, Massachusetts, United States, and its county seat. Springfield sits on the eastern bank of the Connecticut River near its confluence with three rivers: the western Westfield River, the ea ...

. He then opened a women’s hospital in Springfield with his former roommate from college, Charles Robinson Charles, Charlie or Charley Robinson may refer to:

In arts and entertainment

*Charles Dorman Robinson (1847–1933), American painter

*Charles Napier Robinson (1849–1936), English journalist and story writer

*Charles M. Robinson (architect) (18 ...

, who would become the first governor of the State of Kansas, but it failed within six months.

In 1844, he wrote a city mystery (similar to the penny novel) called ''The Mysteries of Springfield'' under the pseudonym J. Wimpleton Wilkes. The cover states that it could be bought from dealers not only in Boston, New York, New Haven, and Hartford, but in Northampton and Cabotville ( Chicopee) as well.

Marriage and career

In 1845 he married Elizabeth Luna Chapin, “the scion of an old and substantial Springfield family.”The Puritan

''The Puritan, or the Widow of Watling Street'', also known as ''The Puritan Widow'', is an anonymous Jacobean stage comedy, first published in 1607. It is often attributed to Thomas Middleton, but also belongs to the Shakespeare Apocrypha ...

, an iconic statue of her ancestor Samuel Chapin

Samuel Chapin (baptized October 8, 1598 – November 11, 1675) was a prominent early settler of Springfield, Massachusetts. He served the town as selectman, magistrate and deacon (in the Massachusetts Bay Colony there was little separation b ...

, stands today in downtown Springfield.Harry Houston Peckham, Josiah Gilbert Holland in Relation to His Times. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1940. She would become a confidant and intimate friend of Emily Dickinson

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson (December 10, 1830 – May 15, 1886) was an American poet. Little-known during her life, she has since been regarded as one of the most important figures in American poetry. Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massac ...

.

In early 1847, Holland begin publishing a newspaper, ''The Bay State Weekly Courier'', but the attempt proved unsuccessful, as did his medical practice. He also published work in the ''Southern Literary Messenger

The ''Southern Literary Messenger'' was a periodical published in Richmond, Virginia, from August 1834 to June 1864, and from 1939 to 1945. Each issue carried a subtitle of "Devoted to Every Department of Literature and the Fine Arts" or some va ...

''.

He left New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

that spring for the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

, and took a teaching position in Richmond, Virginia

Richmond ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. Incorporated in 1742, Richmond has been an independent city (United States), independent city since 1871. ...

, followed by one in Vicksburg, Mississippi

Vicksburg is a historic city in Warren County, Mississippi, United States. It is the county seat. The population was 21,573 at the 2020 census. Located on a high bluff on the east bank of the Mississippi River across from Louisiana, Vicksburg ...

, where he was named superintendent and implemented the ideas of fellow Massachusetts educator and reformer Horace Mann

Horace Mann (May 4, 1796August 2, 1859) was an American educational reformer, slavery abolitionist and Whig Party (United States), Whig politician known for his commitment to promoting public education, he is thus also known as ''The Father of A ...

.

In fall 1848, he and his wife were invited to a large cotton plantation in northeastern Louisiana and Holland wrote down his observations. Here he received word that his poetry would be published in the '' Knickerbocker Magazine'' and ''The Home Journal.''

Springfield

In April 1849, Holland and his wife returned toWestern Massachusetts

Western Massachusetts, known colloquially as "western Mass," is a region in Massachusetts, one of the six U.S. states that make up the New England region of the United States. Western Massachusetts has diverse topography; 22 colleges and univ ...

. His mother-in-law was dying and his wife went to care for her. The following month he was offered $40 a month as assistant editor of '' The Springfield Daily Republican,'' where he began working with the younger, formidable and charming owner—the journalist and editor Samuel Bowles Samuel Bowles may refer to:

*Samuel Bowles (journalist) (1826–1878), American journalist

*Samuel Bowles (economist)

Samuel Stebbins Bowles (; born June 1, 1939), is an American economist and professor emeritus at the University of Massachuset ...

.

On Wednesday, September 26, 1849, '' The Republican'' began publishing Holland's writing of plantation life in a seven-part series, though uncredited, titled, "Three Weeks on a Cotton Plantation." They were well-received by a curious public. He wrote local news and essays, many of which were collected and published in book form, helping establish his literary reputation. Bowles encouraged Holland to publish under the pseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true meaning ( orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individual's o ...

Timothy Titcomb, which he did to great success. The writings were oftentimes formatted as letters, offering the public simple, personal, moral guidance and inspiration.

Under the editorial leadership of Bowles and Holland, '' The Republican'' became the most widely-read and respected small city daily in America. In 1851, Holland received an A.B. honorary doctorate degree from Amherst College

Amherst College ( ) is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1821 as an attempt to relocate Williams College by its then-president Zepha ...

, a few miles north from his birthplace, where Edward Dickinson

Edward Dickinson (January 1, 1803 – June 16, 1874) was an American politician from Massachusetts. He is also known as the father of the poet Emily Dickinson; their family home in Amherst, the Emily Dickinson Museum, is a museum dedicated to h ...

(Emily Dickinson

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson (December 10, 1830 – May 15, 1886) was an American poet. Little-known during her life, she has since been regarded as one of the most important figures in American poetry. Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massac ...

's father) was treasurer.

Holland's first book under his birth name was a two-volume ''History of Western Massachusetts'' (1855), the first book to feature a poem by a Black woman poet in the U.S. He followed in 1857 with an historical novel, ''The Bay-Path: A Tale of Colonial New England Life,'' and a collection of essays titled ''Titcomb's Letters to Young People, Single and Married'' in 1858. There were at least fifty editions of this book. He also published his narrative poem “Bitter-Sweet” that year. In 1857, he began touring on the Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Basic science and some introduction to ...

lecture circuit

The "lecture circuit" is a euphemistic reference to a planned schedule of regular lectures and keynote speeches given by celebrities, often ex-politicians, for which they receive an appearance fee. In Western countries, the lecture circuit has bec ...

, soon mentioned with Oliver Wendell Holmes, Bayard Taylor

Bayard Taylor (January 11, 1825December 19, 1878) was an American poet, literary critic, translator, travel author, and diplomat. As a poet, he was very popular, with a crowd of more than 4,000 attending a poetry reading once, which was a record ...

and George William Curtis

George William Curtis (February 24, 1824 – August 31, 1892) was an American writer, reformer, public speaker, and political activist. He was an abolitionist and supporter of civil rights for African Americans and Native Americans. He also a ...

.

Gold-Foil: Hammered from Popular Proverbs

' under his Timothy Titcomb pen name came out in 1859. He published his second novel,

Miss Gilbert‘s Career: An American Story

', in 1860. It is considered one of the first novels of

American Realism

American realism was a movement in art, music and literature that depicted contemporary social realities and the lives and everyday activities of ordinary people. The movement began in literature in the mid-19th century, and became an importan ...

, anticipating “much abler and more penetrating realists” who would come later that century. The year following he released Lessons in Life: A Series of Familiar Essays

' (1861). In 1862, he erected an opulent home in the

Italianate

The Italianate style was a distinct 19th-century phase in the history of Classical architecture. Like Palladianism and Neoclassicism, the Italianate style combined its inspiration from the models and architectural vocabulary of 16th-century It ...

villa style (also called a “ Swiss-chalet style”). It was located on a bluff overlooking the Connecticut River

The Connecticut River is the longest river in the New England region of the United States, flowing roughly southward for through four states. It rises 300 yards (270 m) south of the U.S. border with Quebec, Canada, and discharges into Long Isl ...

in North Springfield near present day 110 Atwater Terrace. Holland named the mansion “Brightwood”; it was painted Venetian red

Venetian red is a light and warm (somewhat unsaturated) pigment that is a darker shade of red. The composition of Venetian red changed over time. Originally it consisted of natural ferric oxide (Fe2O3, partially hydrated) obtained from the red ...

. The neighborhood today retains the name Brightwood. When Sam Bowles took an extended trip to Europe, Holland temporarily assumed the duties as editor-in-chief of the '' The Springfield Republican''. After the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

he reduced his editorial duties and wrote many of his most popular works, including the ''Life of Abraham Lincoln'' (1866), and ''Kathrina: Her Life and Mine, In a Poem'' (1867).

Lincoln

Holland wrote an eloquent eulogy ofAbraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

within days of Lincoln's death, prompting a commission for a full biography of the late president. He quickly pulled together the lengthy '' Life of Abraham Lincoln'', finished in February 1866. The 544-page bestseller portrayed Lincoln as an emancipator opposed to slavery and began many enduring myths about the slain President.

New York

He moved with his family to 46 Park Avenue in New York City in 1872. These years in New York were also productive for his own literary efforts. During the 1870s he published three novels: ''Arthur Bonnicastle'' (1873),Sevenoaks

' (1875), and ''Nicholas Minturn'' (1877), which first were serialized in

Scribners

Charles Scribner's Sons, or simply Scribner's or Scribner, is an American publisher based in New York City that has published several notable American authors, including Henry James, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Kurt Vonnegut, Marjor ...

(afterwards it became ''The Century Magazine

''The Century Magazine'' was an illustrated monthly magazine first published in the United States in 1881 by The Century Company of New York City, which had been bought in that year by Roswell Smith and renamed by him after the Century Associati ...

''). His poetry volumes included ''The Marble Prophecy'' (1872), ''The Mistress and the Manse'' (1874), and ''The Puritan's Guest'' (1881).

In 1877, Holland erected a summer house on one of the Thousand Islands

The Thousand Islands (, ) constitute a North American archipelago of 1,864 islands that straddles the Canada–US border in the Saint Lawrence River as it emerges from the northeast corner of Lake Ontario. They stretch for about downstream fr ...

in upstate New York, in Alexandria Bay

Alexandria Bay is a village in Jefferson County, New York, United States, within the town of Alexandria. It is located in the Thousand Islands region of northern New York. The population of the village was 1,078 at the 2010 United States census. ...

, where one of its streets is named for him. He gave the mansion itself the name “Bonniecastle” from the name of the titular hero of his novel, ''Arthur Bonnicastle'' (1873). It is known as thBonnie Castle Resort & Marina

today.

Death

Josiah Gilbert Holland died on October 12, 1881, at the age of 62, inNew York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

of heart failure

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure (CHF), is a syndrome caused by an impairment in the heart's ability to Cardiac cycle, fill with and pump blood.

Although symptoms vary based on which side of the heart is affected, HF ...

. The evening prior, he “remained late at the office to finish an editorial tribute to the martyred President James A. Garfield,” who had been assassinated a few weeks before. Most small town newspapers and major metropolitan dailies published memorial tributes to Holland, including journals that had often spoken scornfully of his “literary mediocrity, his triteness, and his intellectual parochialism.” John Greenleaf Whittier

John Greenleaf Whittier (December 17, 1807 – September 7, 1892) was an American Quaker poet and advocate of the abolition of slavery in the United States. Frequently listed as one of the fireside poets, he was influenced by the Scottish poet ...

, the American Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

poet and abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

, consistently praised Holland throughout his life and upon his death. The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

referred to J.G. Holland as “one of the most celebrated writers which this country has produced.”

Holland is buried in Springfield Cemetery in Springfield, Massachusetts

Springfield is the most populous city in Hampden County, Massachusetts, United States, and its county seat. Springfield sits on the eastern bank of the Connecticut River near its confluence with three rivers: the western Westfield River, the ea ...

. His imposing monument includes a bas-relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces remain attached to a solid background of the same material. The term ''relief'' is from the Latin verb , to raise (). To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

portrait sculpted by the eminent American 19th-century sculptor, Augustus Saint-Gaudens

Augustus Saint-Gaudens (; March 1, 1848 – August 3, 1907) was an American sculpture, sculptor of the Beaux-Arts architecture, Beaux-Arts generation who embodied the ideals of the American Renaissance. Saint-Gaudens was born in Dublin to an Iris ...

, and includes the Latin inscription "Et vitam impendere vero" meaning "to devote life to truth".

Works

* History of Western Massachusetts (1855) * The Bay-Path: A Tale of Colonial New England Life (1857) * Bitter-sweet; A Poem (1858) * Letters to Young People, Single and Married (1858) * Gold-Foil, Hammered from Popular Proverbs (1859) * Miss Gilbert’s Career: An American Story (1860) * Lessons in Life; A Series of Familiar Essays (1861) * Letters to the Joneses (1863)The Life of Abraham Lincoln

(1866) * Kathrina: Her Life and Mine, in a poem, (1867) * Christ And The Twelve: Or Scenes and Events in the Life of Our Saviour and His Apostles, as Painted by the Poets (1867) * The Marble Prophecy, And Other Poems (1872) * Garnered Sheaves: The Complete Poetical Works (1872) * Illustrated Library of Favorite Song: Based upon folk songs, and comprising songs of the heart, songs of home, songs of life, and songs of nature (1872) * Plain Talks On Familiar Subjects: A Series of Popular Lectures (1872) * Arthur Bonnicastle: An American Novel (1873) * The Mistress of the Manse: A Poem (1874) * The Story of Sevenoaks: A Story of To-Day (1875) * Nicholas Minturn: A Study in a Story (1876) * Every-Day Topics: A Book of Briefs (1876) First series * The Puritan’s Guest, And Other Poems (1881) * Concerning the Jones Family (1881) (revised from the 1863 book) * Every-Day Topics: A Book of Briefs (1882) Second series

Legacy and influence

Although Josiah Gilbert Holland’s 23 books of fiction, nonfiction and poetry are rarely read today, during the late nineteenth century they were enormously popular and by 1894 more than 750,000 volumes were sold. Holland was born at the beginning of the period of romanticism in American literature. He is considered one of thefireside poets

The fireside poets – also known as the schoolroom or household poets – were a group of 19th-century American poets associated with New England. These poets were very popular among readers and critics both in the United States and overseas. Th ...

such as contemporaries William Cullen Bryant

William Cullen Bryant (November 3, 1794 – June 12, 1878) was an American romantic poet, journalist, and long-time editor of the '' New York Evening Post''. Born in Massachusetts, he started his career as a lawyer but showed an interest in poe ...

and James Russell Lowell

James Russell Lowell (; February 22, 1819 – August 12, 1891) was an American Romantic poet, critic, editor, and diplomat. He is associated with the fireside poets, a group of New England writers who were among the first American poets to r ...

and his work appeared in anthologies, featuring domestic themes, messages of morality

Morality () is the categorization of intentions, Decision-making, decisions and Social actions, actions into those that are ''proper'', or ''right'', and those that are ''improper'', or ''wrong''. Morality can be a body of standards or principle ...

and focused on a historical romantic past. He is also categorized as among the ”minor” New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

authors of the transcendental period.

In the ''History of American Literature'' by Leonidas Warren Payne, Jr., and published in 1919, Holland is “said to have reached a wider popular audience than most of the other minor poets.” Called "a poetic 'play' infused with the beauties of Christianity," Holland's first book-length poem ''Bitter-Sweet: A Poem'' (1858, 220 pp.) sold 90,000 copies by 1894 and remained in print four decades after his death. Thirty years after Holland's death, an "outstandingly authoritative commentator upon American literature" called ''Arthur Bonnicastle'' "the best" of Holland's five novels and another wrote that it was “undoubtedly Holland's masterpiece." The novel remained in print into the 1920s.

In 1875, Holland wrote a letter to be read at the dedication of a monument to Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic who is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales involving mystery and the macabre. He is widely re ...

, the poet and writer, though Holland wrote that the man and his poetry were “without value.” Holland was against Women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

but donated funds to the New England Female Medical College

New England Female Medical College (NEFMC), originally Boston Female Medical College, was founded in 1848 by Samuel Gregory and was the first school to train women in the field of medicine. It merged with Boston University to become the Boston U ...

in Boston. He was member of a Springfield church (North Congregationalist) that was frequented by abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. T ...

, freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, slaves were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their owners), emancipation (granted freedom as part of a larger group), or self- ...

and fugitive slaves

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th centuries to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called fre ...

though Josiah was not considered an abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

.

Literary clubs in Holland’s honor formed in towns and cities across the country, especially in the Midwest

The Midwestern United States (also referred to as the Midwest, the Heartland or the American Midwest) is one of the four census regions defined by the United States Census Bureau. It occupies the northern central part of the United States. It ...

. Newspapers published memorials on the hundredth anniversary of his birth. Fans obtained wood from maple trees standing in the yard of his birthplace at Dwight, Mass., to fashion into memorabilia such as penholders. The doorstone of his birthplace, which burned to the ground in 1876, was recovered in 1932 and placed at thStone House Museum

which also displays first editions of his works.

On Emily Dickinson

J. G. Holland and his wife were frequent correspondents and intimate family friends of poetEmily Dickinson

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson (December 10, 1830 – May 15, 1886) was an American poet. Little-known during her life, she has since been regarded as one of the most important figures in American poetry. Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massac ...

. She was a guest at their Springfield home on numerous occasions. Dickinson sent more than ninety letters to the Hollands between 1853 and 1886 in which she shares “the details of life that one would impart to a close family member: the status of the garden, the health and activities of members of the household, references to recently-read books.”

Emily was a poet “influenced by transcendentalism

Transcendentalism is a philosophical, spiritual, and literary movement that developed in the late 1820s and 1830s in the New England region of the United States. "Transcendentalism is an American literary, political, and philosophical movement of ...

and dark romanticism

Dark Romanticism is a literary sub-genre of Romanticism, reflecting popular fascination with the irrational, the demonic and the grotesque. Often conflated with Gothic fiction, it has shadowed the euphoric Romantic movement ever since its 18th-cen ...

"; her work bridged “the gap to Realism

Realism, Realistic, or Realists may refer to:

In the arts

*Realism (arts), the general attempt to depict subjects truthfully in different forms of the arts

Arts movements related to realism include:

*American Realism

*Classical Realism

*Liter ...

.” Of the ten poems published in Dickinson's lifetime, the Springfield Daily Republican

''The Republican'' is a newspaper based in Springfield, Massachusetts, covering news in the Greater Springfield area, as well as national news and pieces from Boston, Worcester, Massachusetts, Worcester and northern Connecticut. It is owned b ...

, with Sam Bowles and Josiah Holland as editors, published five, all unsigned, between 1852 and 1866. Some scholars believe that Bowles promoted her the most; Dickinson wrote letters and sent her poems to both men. Later, as editor of Scribner’s Monthly

''Scribner's Monthly: An Illustrated Magazine for the People'' was an illustrated American literary periodical published from 1870 until 1881. Following a change in ownership in 1881 of the company that had produced it, the magazine was relaunc ...

beginning in 1870, Holland told Dickinson’s childhood friend Emily Fowler Ford that he had “some poems of Dickinson’s">Emily_Dickinson.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Emily Dickinson">Dickinson’sunder consideration for publication [in Scribner’s Monthly

''Scribner's Monthly: An Illustrated Magazine for the People'' was an illustrated American literary periodical published from 1870 until 1881. Following a change in ownership in 1881 of the company that had produced it, the magazine was relaunc ...

]—but they really are not suitable—they are too ethereal.”

Publishes oldest African American poem

Josiah Gilbert Holland published the oldest known work of literature written by anAfrican American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

in North America. A 16-year-old named Lucy Terry

Lucy Terry Prince, often credited as simply Lucy Terry (c. 1733–1821), was an American settler and poet. Kidnapped in Africa and enslaved, she was taken to the British colony of Rhode Island. Her future husband purchased her freedom before ...

(1733–1821) witnessed two White families attacked by Native Americans in 1746. The fight took place in Deerfield, Mass. Known as “Bars Fight

"Bars Fight" is a Ballad (poetry), ballad poem written by Lucy Terry about an attack upon two white families by Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans on August 21, 1746. The incident occurred in an area of Deerfield, Massachuset ...

,” her poem was told orally until it was published, thirty-three years after her death, first in ''The'' ''Springfield Daily Republican'', on November 20, 1854, as an excerpt from Holland'''History of Western Massachusetts''

which was published as a book the following year.

On Melville and Whitman

Holland,Herman Melville

Herman Melville (Name change, born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance (literature), American Renaissance period. Among his best-known works ar ...

and Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman Jr. (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist, and journalist; he also wrote two novels. He is considered one of the most influential poets in American literature and world literature. Whitman incor ...

were born the same year.

Holland, as associate editor of '' The Republican,'' was critically favorable to canonical

The adjective canonical is applied in many contexts to mean 'according to the canon' the standard, rule or primary source that is accepted as authoritative for the body of knowledge or literature in that context. In mathematics, ''canonical exampl ...

novelist Herman Melville

Herman Melville (Name change, born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance (literature), American Renaissance period. Among his best-known works ar ...

and as co-founder and editor of ''Scribner's Monthly

''Scribner's Monthly: An Illustrated Magazine for the People'' was an illustrated American literary periodical published from 1870 until 1881. Following a change in ownership in 1881 of the company that had produced it, the magazine was relaunc ...

'', Holland turned down publishing the more widely read canonical

The adjective canonical is applied in many contexts to mean 'according to the canon' the standard, rule or primary source that is accepted as authoritative for the body of knowledge or literature in that context. In mathematics, ''canonical exampl ...

poet Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman Jr. (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist, and journalist; he also wrote two novels. He is considered one of the most influential poets in American literature and world literature. Whitman incor ...

.

Considered a writer and man of "Victorian virtue," J.G. Holland found Whitman's poetry “immoral.” Whitman later called Holland, “a man of his time, not possessed of the slightest forereach; ... the style of man ... who can tell the difference between a dime and a fifty-cent piece—but is useless for occasions of more serious moment.” The irony was that Holland wrote a bestseller after the “more serious moment” of President Lincoln’s assassination. All the same, even ''Springfield Republican'' publisher Samuel Bowles Samuel Bowles may refer to:

*Samuel Bowles (journalist) (1826–1878), American journalist

*Samuel Bowles (economist)

Samuel Stebbins Bowles (; born June 1, 1939), is an American economist and professor emeritus at the University of Massachuset ...

"thought Holland something of a prig.” A later biographer had this to say: That Josiah Gilbert Holland remained priggish and prudish to the end of his days is all too abundantly attested. His provincial ethical standards; his subconscious Pharisaism; his incorrigible moralizing; his stubborn opposition to woman suffrage; his failure to distinguish between social drinking and debauchery, between light wine and strong whisky, between beer and rum, between the intelligent frankness ofWalt Whitman Walter Whitman Jr. (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist, and journalist; he also wrote two novels. He is considered one of the most influential poets in American literature and world literature. Whitman incor ...and the vulgar pornography of ''The Black Crook ''The Black Crook'' is a work of musical theatre first produced in New York City with great success in 1866. Many theatre writers have cautiously identified ''The Black Crook'' as the first popular piece that conforms to the modern notion of a mu ...''—all these remained almost as irritatingly obtrusive at the end of his career as at the beginning.

On the word "jazz"

Holland coined a term that later became the word "jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Its roots are in blues, ragtime, European harmony, African rhythmic rituals, spirituals, h ...

." The earliest tracing in the Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the principal historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP), a University of Oxford publishing house. The dictionary, which published its first editio ...

finds that �jasm

�� first appears in Holland’s 1860 novel, Miss Gilbert's Career: “‘She's just like her mother... Oh! she’s just as full of jasm!’.. ‘Now tell me what jasm is.’.. ‘If you'll take thunder and lightening ic and a steamboat and a buzz-saw, and mix 'em up, and put 'em into a woman, that's jasm.’” The word was used to describe the "inexpressible personal force of the

Yankee

The term ''Yankee'' and its contracted form ''Yank'' have several interrelated meanings, all referring to people from the United States. Their various meanings depend on the context, and may refer to New Englanders, the Northeastern United Stat ...

" and morphed into the word “jazz” in the early twentieth century.

Postbellum spiritual mentor

In the devastating wake of theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, Holland offered Americans spiritual guidance and ultimately, hope.That there was a Dr. Holland, a man who brought hope, reassurance, continuity and order into a chaotic, threatening world was itself a fact of great spiritual significance for millions of Americans. UnlikeOf poets and their mission, Holland wrote:Henry Ward Beecher Henry Ward Beecher (June 24, 1813 – March 8, 1887) was an American Congregationalist clergyman, social reformer, and speaker, known for his support of the Abolitionism, abolition of slavery, his emphasis on God's love, and his 1875 adultery ..., whom he steadfastly supported, nothing even remotely suspect ever came near him. Instead, in such essays as "The Reconstruction of National Morality," published in April 1876, and "Falling from High Places," published in April 1878, he offered acute analyses of why, in the post-war years, so many Americans, including prominent Christian leaders, had succumbed to the temptation of attempting to obtain great riches dishonestly. Such was the sanctity of Holland's own life that he seemed to offer a living, earthly warrant for the promise of eternity that he pictured in his writings.

The poets of the world are the prophets of humanity. They forever reach after and foresee the ultimate good. They are evermore building the Paradise that it is to be, painting the Millennium that is to come. When the world shall reach the poet’s ideal, it will arrive at perfection; and much good will it do the world to measure itself by this ideal and struggle to lift the real to its lofty level.He also wrote: ''"God never said it would be easy, He just said He would go with me."'' Holland’s narrative poem ''“

Bitter-Sweet

�� would become one of his most popular, and was described in 1894, by biographer Harriette Merrick Plunkett, as,

Dr. Holland’s reflections on the mysteries of Life and Death, on the soul-wracking problems of Doubt and Faith, on the existence of Evil as one of the vital conditions of the universe, on the questions ofShe declared it to be “truly an original poem,” and compared it to the works ofPredestination Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby Go ...,Original Sin Original sin () in Christian theology refers to the condition of sinfulness that all humans share, which is inherited from Adam and Eve due to the Fall of man, Fall, involving the loss of original righteousness and the distortion of the Image ...,Free-will is an independent Japanese independent record label, record label founded in 1986 by Color (band), Color vocalist Hiroshi "Dynamite Tommy" Tomioka, with branches predominantly in Japan and the United States, as well as previously in Europe. Th ..., and the whole haunting brood ofCalvinistic Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyterian, ...theological Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of an ...metaphysics Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ....

Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the List of national poets, national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the be ...

or Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

. She cited the praise that it had earned from poet James Russell Lowell

James Russell Lowell (; February 22, 1819 – August 12, 1891) was an American Romantic poet, critic, editor, and diplomat. He is associated with the fireside poets, a group of New England writers who were among the first American poets to r ...

. Today, a Hollansentence or paragraph

is still quoted by politicians, artists and spiritual leaders alike, including

Martin Luther King, Jr

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister, civil rights activist and political philosopher who was a leader of the civil rights movement from 1955 until his ...

., though few recognize his name.

In film

In 1920, Holland’s novelSevenoaks

' (1875) was adapted into the

Goldwyn Goldwyn is both a surname and a given name. Notable people with the name include:

Surname

*Beryl Goldwyn (born 1930), English ballerina

*John Goldwyn (born 1958), American film producer

* Liz Goldwyn (born 1976), American film director

* Robert Gol ...

comedy-drama, Jes' Call Me Jim

''Jes' Call Me Jim'' is a 1920 American comedy-drama film directed by Clarence G. Badger and written by Edward T. Lowe Jr. and Thompson Buchanan. It is based on the 1875 novel ''Sevenoaks'' by Josiah Gilbert Holland. The film stars Will Rogers ...

, starring Will Rogers

William Penn Adair Rogers (November 4, 1879 – August 15, 1935) was an American vaudeville performer, actor, and humorous social commentator. He was born as a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, in the Indian Territory (now part of Oklahoma ...

.

In the 2016 film A Quiet Passion

''A Quiet Passion'' is a 2016 British biographical film written and directed by Terence Davies about the life of American poet Emily Dickinson. The film stars Cynthia Nixon as the reclusive poet. It co-stars Emma Bell as young Dickinson, Jenni ...

about the life of Emily Dickinson

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson (December 10, 1830 – May 15, 1886) was an American poet. Little-known during her life, she has since been regarded as one of the most important figures in American poetry. Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massac ...

, Steve Dan Mills portrays Holland.

In the 2018 film Wild Nights with Emily, Josiah and Elizabeth Holland are portrayed by actor Michael Churven and actress Guinevere Turner

Guinevere Jane Turner (born May 23, 1968) is an American actress, screenwriter, and film director. She wrote the films ''American Psycho'' and '' The Notorious Bettie Page'' and played the lead role of the dominatrix Tanya Cheex in '' Preachin ...

, respectively.

The Osage Nation

The Osage Nation ( ) () is a Midwestern Native American nation of the Great Plains. The tribe began in the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys around 1620 A.D along with other groups of its language family, then migrated west in the 17th cen ...

politician Arthur Bonnicastle

Arthur Bonnicastle (February 20, 1877 – May 30, 1923) was an Osage politician who served as the 8th elected principal chief of the Osage Nation from 1920 to 1922. Born in the Osage Nation, Indian Territory, Bonnicastle attended the Carlisle In ...

—named for the titular character in Holland’s 187novel

��appears as a character in the 2023 film Killers of the Flower Moon.

Further reading

* Bacon, Edwin Monroe. Literary Pilgrimages in New England to the Homes of Famous Makers of American Literature and Among Their Haunts and the Scenes of Their Writings. United States, Silver, Burdett, 1902. * Dickinson, Emily, et al. Letters to Dr. and Mrs. Josiah Gilbert Holland. United States, Harvard University Press, 1951. * Gabriel, Ralph Henry. The Pageant of America: A Pictorial History of the United States. Volume 11: The American spirit in letters. United States, Yale University Press, 1926, 201. * Greene, Aella. Reminiscent Sketches. Florence, Massachusetts: Press of the Bryant Print, 1902. * Habegger, Alfred. My Wars Are Laid Away in Books: The Life of Emily Dickinson. United Kingdom, Random House Publishing Group, 2001. * Historical Dictionary of the Gilded Age. United States, M.E. Sharpe, 2003., p. 13. *Hollander, John. American Poetry - The Nineteenth Century Vol. lI. United States, Library of America, 1993. * Keane, Patrick J.. Emily Dickinson's Approving God: Divine Design and the Problem of Suffering. United Kingdom, University of Missouri Press, 2008. * Leiter, SharonCritical Companion to Emily Dickinson: A Literary Reference to Her Life and Work

United States, Facts On File, Incorporated, 2007. (Mass ), Springfield

The Nation Weeping for Its Dead: Observances at Springfield, Massachusetts, on President Lincoln's Funeral Day, Wednesday, April 19, 1865, Including Dr. Holland's Eulogy.

* Mead, Carl David. Yankee Eloquence in the Middle West: The Ohio Lyceum, 1850-1870. United States, Michigan State College Press, 1951. * Meyer, Rose D.. Authors Digest: The World's Great Stories in Brief. United States, Issued under the auspices of the Authors Press, 1927. A five-page briefing on Holland’s novel

Sevenoaks

'. * Morgan, Robert J.. Then Sings My Soul Special Edition: 150 Christmas, Easter, and All-Time Favorite Hymn Stories. United States, Thomas Nelson, 2022. *

References

*External links

* * * *Holland Collection of Literary Letters, University of Colorado Boulder

Titcomb’s Letters to Young People, Single and Married

* Plunkett, Harriette Merrick. Josiah Gilbert Holland. United States, C. Scribner's Sons, 1894

Short audio essay, "A Serendipitous Encounter With The Ghost Of A Once-Famous Belchertonian," about Josiah Gilbert Holland

* C. Scribner's & Sons published Holland’s Complete Works in a 16-volume set that may be found online a

HathiTrust

*All of his published books may be found online a

HathiTrust

*His papers are collected at th

New York Public Library

and a

The Archives at Yale

*Much o

his work

remains in print by classic reprinting publishers {{DEFAULTSORT:Holland, Josiah Gilbert 19th-century American novelists American male novelists American magazine editors Novelists from Massachusetts 1819 births 1881 deaths Massachusetts Republicans American male poets 19th-century American poets 19th-century American journalists American male journalists Berkshire Medical College alumni 19th-century American male writers Biographers of Abraham Lincoln American male biographers Writers from Springfield, Massachusetts Poets from Springfield, Massachusetts