Ivan Goncharov on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

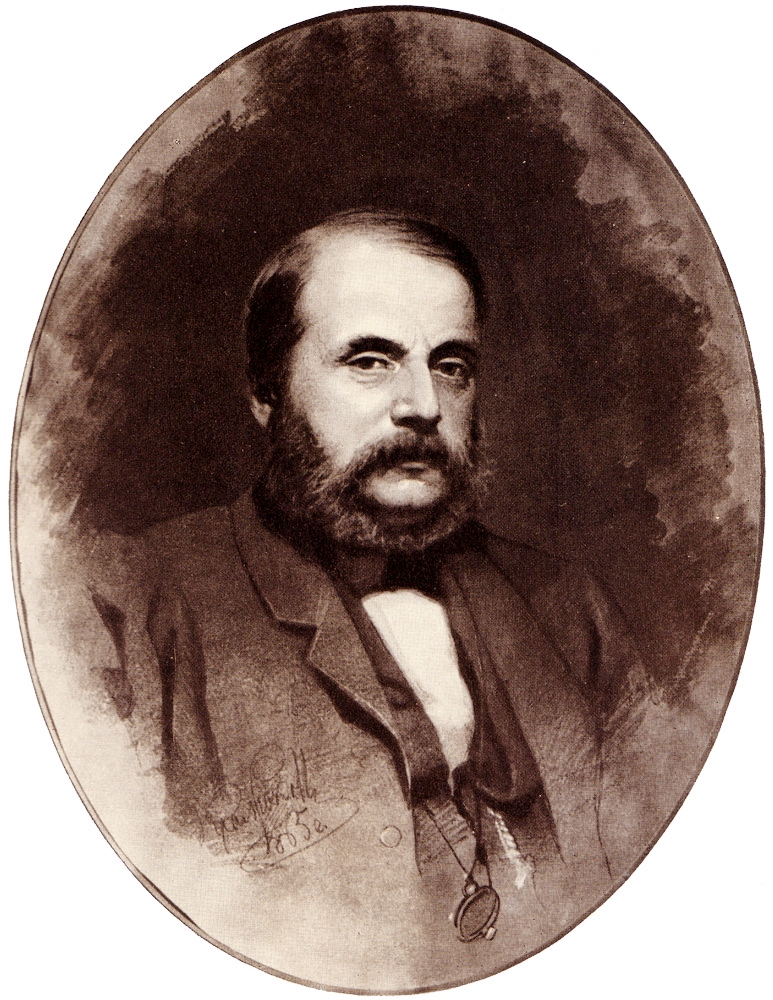

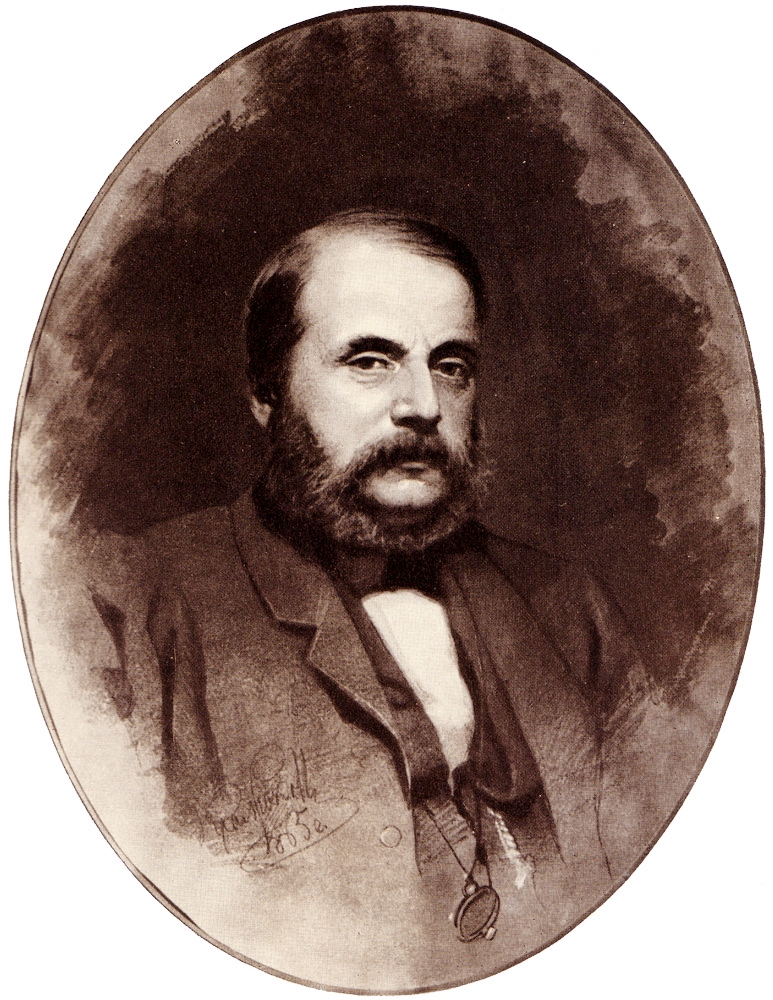

Ivan Aleksandrovich Goncharov ( , ; rus, Ива́н Алекса́ндрович Гончаро́в, r=Iván Aleksándrovich Goncharóv, p=ɪˈvan ɐlʲɪkˈsandrəvʲɪdʑ ɡənʲtɕɪˈrof; – ) was a Russian novelist best known for his novels '' The Same Old Story'' (1847, also translated as ''A Common Story''), '' Oblomov'' (1859), and '' The Precipice'' (1869, also translated as ''Malinovka Heights''). He also served in many official capacities, including the position of censor.

Goncharov was born in Simbirsk into the family of a wealthy merchant; as a reward for his grandfather's military service, they were elevated to

His first piece of prose appeared in an issue of ''Snowdrop'', a satirical novella called ''Evil Illness'' (1838), ridiculing romantic sentimentalism and fantasizing. Another novella, ''A Fortunate Blunder'', a "high-society drama" in the tradition set by Marlinsky, Vladimir Odoevsky, and

His first piece of prose appeared in an issue of ''Snowdrop'', a satirical novella called ''Evil Illness'' (1838), ridiculing romantic sentimentalism and fantasizing. Another novella, ''A Fortunate Blunder'', a "high-society drama" in the tradition set by Marlinsky, Vladimir Odoevsky, and

Throughout the 1850s Goncharov worked on his second novel, but the process was slow for many reasons. In 1855 he accepted the post of censor in the Saint Petersburg censorship committee. In this capacity, he helped publish important works by Ivan Turgenev, Nikolay Nekrasov, Aleksey Pisemsky, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky, a fact that brought resentment from some of his bosses. According to Pisemsky, Goncharov was officially reprimanded for permitting his novel ''A Thousand Souls'' to be published. Despite all this, Goncharov became the target of many satires and received a negative mention in Herzen's ''Kolokol''. "One of the best Russian authors shouldn't have taken this sort of job upon himself," critic Aleksander Druzhinin wrote in his diary. In 1856, as the official publishing policy hardened, Goncharov quit.

In the summer of 1857, Goncharov went to Marienbad for medical treatment. There he wrote ''Oblomov'', almost in its entirety. "It might seem strange, even impossible that in the course of one month the whole of the novel might be written... But it'd been growing in me for several years, so what I had to do then was just sit and write everything down," he later remembered. Goncharov's second novel '' Oblomov'' was published in 1859 in ''Otechestvennye Zapiski''. It had evolved from the earlier "Oblomov's Dream", which was later incorporated into the finished novel as Chapter 9. The novel caused much discussion in the Russian press, introduced another new term, ''oblomovshchina'', to the literary lexicon and is regarded as a Russian classic.

In his essay ''What Is Oblomovshchina?'' Nikolay Dobrolyubov provided an ideological background for the type of Russia's 'new man' exposed by Goncharov. The critic argued that, while several famous classic Russian literary characters – Onegin, Pechorin, and Rudin – bore symptoms of the 'Oblomov malaise', for the first time one single feature, that of social apathy, a self-destructive kind of laziness and unwillingness to even try and lift the burden of all-pervading inertia, had been brought to the fore and subjected to a thorough analysis.

Throughout the 1850s Goncharov worked on his second novel, but the process was slow for many reasons. In 1855 he accepted the post of censor in the Saint Petersburg censorship committee. In this capacity, he helped publish important works by Ivan Turgenev, Nikolay Nekrasov, Aleksey Pisemsky, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky, a fact that brought resentment from some of his bosses. According to Pisemsky, Goncharov was officially reprimanded for permitting his novel ''A Thousand Souls'' to be published. Despite all this, Goncharov became the target of many satires and received a negative mention in Herzen's ''Kolokol''. "One of the best Russian authors shouldn't have taken this sort of job upon himself," critic Aleksander Druzhinin wrote in his diary. In 1856, as the official publishing policy hardened, Goncharov quit.

In the summer of 1857, Goncharov went to Marienbad for medical treatment. There he wrote ''Oblomov'', almost in its entirety. "It might seem strange, even impossible that in the course of one month the whole of the novel might be written... But it'd been growing in me for several years, so what I had to do then was just sit and write everything down," he later remembered. Goncharov's second novel '' Oblomov'' was published in 1859 in ''Otechestvennye Zapiski''. It had evolved from the earlier "Oblomov's Dream", which was later incorporated into the finished novel as Chapter 9. The novel caused much discussion in the Russian press, introduced another new term, ''oblomovshchina'', to the literary lexicon and is regarded as a Russian classic.

In his essay ''What Is Oblomovshchina?'' Nikolay Dobrolyubov provided an ideological background for the type of Russia's 'new man' exposed by Goncharov. The critic argued that, while several famous classic Russian literary characters – Onegin, Pechorin, and Rudin – bore symptoms of the 'Oblomov malaise', for the first time one single feature, that of social apathy, a self-destructive kind of laziness and unwillingness to even try and lift the burden of all-pervading inertia, had been brought to the fore and subjected to a thorough analysis.

A moderate conservative at heart, Goncharov greeted the

A moderate conservative at heart, Goncharov greeted the

Goncharov planned a fourth novel, set in the 1870s, but it failed to materialize. Instead he became a prolific critic, providing numerous theater and literature reviews; his "Myriad of Agonies" (Milyon terzaniy, 1871) is still regarded as one of the best essays on Alexandr Griboyedov's '' Woe from Wit''. Goncharov also wrote short stories: his ''Servants of an Old Age'' cycle as well as "The Irony of Fate", "Ukha" and others, described the life of rural Russia. In 1880 the first edition of ''The Complete Works of Goncharov'' was published. After the writer's death, it became known that he had burnt many later manuscripts.

Towards the end of his life Goncharov wrote an unusual memoir called '' An Uncommon Story'', in which he accused his literary rivals, first and foremost

Goncharov planned a fourth novel, set in the 1870s, but it failed to materialize. Instead he became a prolific critic, providing numerous theater and literature reviews; his "Myriad of Agonies" (Milyon terzaniy, 1871) is still regarded as one of the best essays on Alexandr Griboyedov's '' Woe from Wit''. Goncharov also wrote short stories: his ''Servants of an Old Age'' cycle as well as "The Irony of Fate", "Ukha" and others, described the life of rural Russia. In 1880 the first edition of ''The Complete Works of Goncharov'' was published. After the writer's death, it became known that he had burnt many later manuscripts.

Towards the end of his life Goncharov wrote an unusual memoir called '' An Uncommon Story'', in which he accused his literary rivals, first and foremost

Russian nobility

The Russian nobility or ''dvoryanstvo'' () arose in the Middle Ages. In 1914, it consisted of approximately 1,900,000 members, out of a total population of 138,200,000. Up until the February Revolution of 1917, the Russian noble estates staffed ...

status. He was educated at a boarding school, then the Moscow College of Commerce, and finally at Moscow State University

Moscow State University (MSU), officially M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University,. is a public university, public research university in Moscow, Russia. The university includes 15 research institutes, 43 faculties, more than 300 departments, a ...

. After graduating, he served for a short time in the office of the Governor of Simbirsk, before moving to Saint Petersburg where he worked as government translator and private tutor, while publishing poetry and fiction in private almanacs. Goncharov's first novel, ''The Same Old Story'', was published in '' Sovremennik'' in 1847.

Goncharov's second and best-known novel, '' Oblomov'', was published in 1859 in '' Otechestvennye zapiski''. His third and final novel, '' The Precipice'', was published in '' Vestnik Evropy'' in 1869. He also worked as a literary and theatre critic. Towards the end of his life Goncharov wrote a memoir called '' An Uncommon Story'', in which he accused his literary rivals, first and foremost Ivan Turgenev

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev ( ; rus, links=no, Иван Сергеевич ТургеневIn Turgenev's day, his name was written ., p=ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf; – ) was a Russian novelist, short story writer, poe ...

, of having plagiarized his works and prevented him from achieving European fame. The memoir was published in 1924. Fyodor Dostoevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in both Russian and world literature, and many of his works are considered highly influent ...

, among others, considered Goncharov an author of high stature. Anton Chekhov

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (; ; 29 January 1860 – 15 July 1904) was a Russian playwright and short-story writer, widely considered to be one of the greatest writers of all time. His career as a playwright produced four classics, and his b ...

is quoted as stating that Goncharov was "...ten heads above me in talent."

Biography

Early life

Goncharov was born in Simbirsk (nowUlyanovsk

Ulyanovsk,, , known as Simbirsk until 1924, is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Ulyanovsk Oblast, Russia, located on the Volga River east of Moscow. Ulyanovsk has been the only Russian UNESCO Ci ...

). His father, Aleksander Ivanovich Goncharov, was a wealthy grain merchant and a state official who served several terms as mayor of Simbirsk. The family's big stone manor in the town center occupied a large area and had all the characteristics of a rural manor, with huge barns (packed with wheat and flour) and numerous stables.Mashinsky, S. Goncharov and His Legacy. Foreword to The Works of I.A.Goncharov in 6 Volumes. Ogonyok's Library. Pravda Publishers. Moscow, 1972. pp. 3–54 Alexander Ivanovich died when Ivan was seven years old. He was educated first by his mother, Avdotya Matveevna, and then his godfather Nikolay Nikolayevich Tregubov, a nobleman and a former Russian Navy

The Russian Navy is the Navy, naval arm of the Russian Armed Forces. It has existed in various forms since 1696. Its present iteration was formed in January 1992 when it succeeded the Navy of the Commonwealth of Independent States (which had i ...

officer.

Tregubov, a man of liberal views and a secret Masonic lodge

A Masonic lodge (also called Freemasons' lodge, or private lodge or constituent lodge) is the basic organisational unit of Freemasonry.

It is also a commonly used term for a building where Freemasons meet and hold their meetings. Every new l ...

member, who knew some of the Decembrists personally, and who was one of the most popular men amongst the Simbirsk intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

, was a major early influence upon Goncharov, who particularly enjoyed his seafaring stories. With Tregubov around, Goncharov's mother could focus on domestic affairs. "His servants, cabmen, the whole household merged with ours; it was a single family. All the practical issues were now mother's, and she proved to be an excellent housewife; all the official duties were his," Ivan Goncharov remembered.

Education

200px, Plaque on the house in 20 Goncharova street in Ulyanovsk, where Goncharov was born in 1812 In 1820–1822 Goncharov studied at a private boarding-school owned by Rev. Fyodor S. Troitsky. It was here that he learned the French andGerman language

German (, ) is a West Germanic language in the Indo-European language family, mainly spoken in Western Europe, Western and Central Europe. It is the majority and Official language, official (or co-official) language in Germany, Austria, Switze ...

s and started reading European writers, borrowing books from Troitsky's vast library. In August 1822, Ivan was sent to Moscow and entered the College of Commerce. There he spent eight unhappy years, detesting the low quality of education and the severe discipline, taking solace in self-education. "My first humanitarian and moral teacher was Nikolai Karamzin", he remembered. Then Pushkin came as a revelation; the serial publication of his poem ''Eugene Onegin

''Eugene Onegin, A Novel in Verse'' (, Reforms of Russian orthography, pre-reform Russian: Евгеній Онѣгинъ, романъ въ стихахъ, ) is a novel in verse written by Alexander Pushkin. ''Onegin'' is considered a classic of ...

'' captured the young man's imagination. In 1830, Goncharov decided to quit the college, and in 1831 (having missed one year because of a cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

outbreak in Moscow), he enrolled in Moscow State University

Moscow State University (MSU), officially M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University,. is a public university, public research university in Moscow, Russia. The university includes 15 research institutes, 43 faculties, more than 300 departments, a ...

's Philology

Philology () is the study of language in Oral tradition, oral and writing, written historical sources. It is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics with strong ties to etymology. Philology is also de ...

Faculty to study literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

, arts

The arts or creative arts are a vast range of human practices involving creativity, creative expression, storytelling, and cultural participation. The arts encompass diverse and plural modes of thought, deeds, and existence in an extensive ...

, and architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and construction, constructi ...

.

At the University, with its atmosphere of intellectual freedom and lively debate, Goncharov's spirit thrived. One episode proved to be especially memorable: when his then-idol Alexander Pushkin arrived as a guest lecturer to have a public debate with professor Mikhail T. Katchenovsky on the authenticity of ''The Tale of Igor's Campaign

''The Tale of Igor's Campaign'' or ''The Tale of Ihor's Campaign'' () is an anonymous epic poem written in the Old East Slavic language.

The title is occasionally translated as ''The Tale of the Campaign of Igor'', ''The Song of Igor's Campaign'' ...

''. "It was as if sunlight lit up the auditorium. I was enchanted by his poetry at the time...it was his genius that formed my aesthetic ideas – although the same, I think, could be said of all the young people of the time who were interested in poetry", Goncharov wrote. Unlike Alexander Herzen, Vissarion Belinsky or Nikolay Ogaryov, his fellow Moscow University students, Goncharov remained indifferent to the ideas of political and social change that were gaining popularity at the time. Reading and translating were his main occupations. In 1832, the ''Telescope'' magazine published two chapters of Eugène Sue

Marie-Joseph "Eugène" Sue (; 26 January 18043 August 1857) was a French novelist. He was one of several authors who popularized the genre of the serial novel in France with his very popular and widely imitated '' The Mysteries of Paris'', whi ...

's novel ''Atar-Gull'' (1831), translated by Goncharov. This was his debut publication.

In 1834, Goncharov graduated from the University and returned home to enter the chancellery of Simbirsk governor A. M. Zagryazhsky. A year later, he moved to Saint Petersburg and started working as a translator at the Finance Ministry's Foreign commerce department. Here, in the Russian capital, he became friends with the Maykov family and tutored both Apollon Maykov and Valerian Maykov in the Latin language

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

and in Russian literature

Russian literature refers to the literature of Russia, its Russian diaspora, émigrés, and to Russian language, Russian-language literature. Major contributors to Russian literature, as well as English for instance, are authors of different e ...

. He became a member of the elitist literary circle based in the Maykovs' house and attended by writers like Ivan Turgenev

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev ( ; rus, links=no, Иван Сергеевич ТургеневIn Turgenev's day, his name was written ., p=ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf; – ) was a Russian novelist, short story writer, poe ...

, Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in both Russian literature, Russian and world literature, and many of his works are consider ...

and Dmitry Grigorovich. The Maykovs' almanac ''Snowdrop'' featured many of Goncharov's poems, but he soon stopped dabbling in poetry altogether. Some of those early verses were later incorporated into the novel '' The Same Old Story'' as Aduev's writings, a sure sign that the author had stopped taking them seriously.

Literary career

His first piece of prose appeared in an issue of ''Snowdrop'', a satirical novella called ''Evil Illness'' (1838), ridiculing romantic sentimentalism and fantasizing. Another novella, ''A Fortunate Blunder'', a "high-society drama" in the tradition set by Marlinsky, Vladimir Odoevsky, and

His first piece of prose appeared in an issue of ''Snowdrop'', a satirical novella called ''Evil Illness'' (1838), ridiculing romantic sentimentalism and fantasizing. Another novella, ''A Fortunate Blunder'', a "high-society drama" in the tradition set by Marlinsky, Vladimir Odoevsky, and Vladimir Sollogub

Count Vladimir Alexandrovich Sollogub (; ; 20 August 1813 – 17 June 1882) was a minor Russian writer, author of novelettes, essays, plays, and memoirs.

Born in Saint Petersburg, his paternal grandfather was a Polish aristocrat, and he grew up i ...

, tinged with comedy, appeared in another privately published almanac, ''Moonlit Nights'', in 1839. In 1842 Goncharov wrote an essay called ''Ivan Savvich Podzhabrin'', a natural school psychological sketch. Published in '' Sovremennik'' six years later, it failed to make any impact, being very much a period piece, but later scholars reviewed it positively, as something in the vein of the Nikolay Gogol-inspired genre known as the "physiological essay", marked by a fine style and precision in depicting the life of the common man in the city. In the early 1840s Goncharov worked on a novel called ''The Old People'', but the manuscript has been lost.

''The Same Old Story''

Goncharov's first novel, '' The Same Old Story'', was published in ''Sovremennik'' in 1847. It dealt with the conflict between the excessive romanticism of a young Russian nobleman who has recently arrived inSaint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

from the provinces, and the sober pragmatism of the emerging commercial class of the capital. ''The Same Old Story'' polarized critics and made its author famous. The novel was a direct response to Vissarion Belinsky's call for exposing a new type, that of the complacent romantic, common at the time; it was lavishly praised by the famous critic as one of the best Russian books of the year. The term ''aduyevschina'' (after the novel's protagonist Aduyev) became popular with reviewers who saw it as synonymous with vain romantic aspirations. Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using Reforms of Russian orthography#The post-revolution re ...

, who liked the novel, used the same word to describe social egotism and the inability of some people to see beyond their immediate interests.

In 1849 ''Sovremennik'' published ''Oblomov's Dream'', an extract from Goncharov's future second novel ''Oblomov'' (known under the working title ''The Artist'' at the time), which worked well on its own as a short story. Again it was lauded by the ''Sovremennik'' staff. Slavophiles

Slavophilia () was a movement originating from the 19th century that wanted the Russian Empire to be developed on the basis of values and institutions derived from Russia's early history. Slavophiles opposed the influences of Western Europe in Rus ...

, while giving the author credit for being a fine stylist, reviled the irony aimed at patriarchal Russian ways. The novel itself, though, appeared only ten years later, preceded by some extraordinary events in Goncharov's life.

In 1852 Goncharov embarked on a long journey through England, Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

, Japan, and back to Russia, on board the frigate ''Pallada'', as a secretary for Admiral Yevfimy Putyatin, whose mission was to inspect Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

and other distant outposts of the Empire, and also to establish trade relations with Japan. The log-book which it was Goncharov's duty to keep served as a basis for his future book. He returned to Saint Petersburg on 25 February 1855, after traveling through Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

and the Urals

The Ural Mountains ( ),; , ; , or simply the Urals, are a mountain range in Eurasia that runs north–south mostly through Russia, from the coast of the Arctic Ocean to the river Ural (river), Ural and northwestern Kazakhstan.

, this continental leg of the journey lasting six months. Goncharov's travelogue, '' Frigate "Pallada"'' ("Pallada" is the Russian spelling of "Pallas

Pallas may refer to:

Astronomy

* 2 Pallas asteroid

** Pallas family, a group of asteroids that includes 2 Pallas

* Pallas (crater), a crater on Earth's moon

Mythology

* Pallas (Giant), a son of Uranus and Gaia, killed and flayed by Athena

* Pa ...

"), began to appear, first in '' Otechestvennye Zapiski'' (April 1855), then in ''The Sea Anthology'' and other magazines.

In 1858, ''Frigate "Pallada"'' was published as a separate book; it received favourable reviews and became very popular. For the mid-19th-century Russian readership, the book came as a revelation, providing new insights into the world, hitherto unknown. Goncharov, a well-read man and a specialist in the history and economics of the countries he visited, proved to be a competent and insightful writer. He warned against seeing his work as any kind of political or social statement, insisting it was a subjective piece of writing, but critics praised the book as a well-balanced, unbiased report, containing valuable ethnographic material, but also some social critique. Again, the anti-romantic tendency prevailed: it was seen as part of the polemic with those Russian authors who tended to romanticize the "pure and unspoiled" life of the uncivilized world. According to Nikolay Dobrolyubov, ''The Frigate Pallada'' "bore the hallmark of a gifted epic novelist."

''Oblomov''

Throughout the 1850s Goncharov worked on his second novel, but the process was slow for many reasons. In 1855 he accepted the post of censor in the Saint Petersburg censorship committee. In this capacity, he helped publish important works by Ivan Turgenev, Nikolay Nekrasov, Aleksey Pisemsky, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky, a fact that brought resentment from some of his bosses. According to Pisemsky, Goncharov was officially reprimanded for permitting his novel ''A Thousand Souls'' to be published. Despite all this, Goncharov became the target of many satires and received a negative mention in Herzen's ''Kolokol''. "One of the best Russian authors shouldn't have taken this sort of job upon himself," critic Aleksander Druzhinin wrote in his diary. In 1856, as the official publishing policy hardened, Goncharov quit.

In the summer of 1857, Goncharov went to Marienbad for medical treatment. There he wrote ''Oblomov'', almost in its entirety. "It might seem strange, even impossible that in the course of one month the whole of the novel might be written... But it'd been growing in me for several years, so what I had to do then was just sit and write everything down," he later remembered. Goncharov's second novel '' Oblomov'' was published in 1859 in ''Otechestvennye Zapiski''. It had evolved from the earlier "Oblomov's Dream", which was later incorporated into the finished novel as Chapter 9. The novel caused much discussion in the Russian press, introduced another new term, ''oblomovshchina'', to the literary lexicon and is regarded as a Russian classic.

In his essay ''What Is Oblomovshchina?'' Nikolay Dobrolyubov provided an ideological background for the type of Russia's 'new man' exposed by Goncharov. The critic argued that, while several famous classic Russian literary characters – Onegin, Pechorin, and Rudin – bore symptoms of the 'Oblomov malaise', for the first time one single feature, that of social apathy, a self-destructive kind of laziness and unwillingness to even try and lift the burden of all-pervading inertia, had been brought to the fore and subjected to a thorough analysis.

Throughout the 1850s Goncharov worked on his second novel, but the process was slow for many reasons. In 1855 he accepted the post of censor in the Saint Petersburg censorship committee. In this capacity, he helped publish important works by Ivan Turgenev, Nikolay Nekrasov, Aleksey Pisemsky, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky, a fact that brought resentment from some of his bosses. According to Pisemsky, Goncharov was officially reprimanded for permitting his novel ''A Thousand Souls'' to be published. Despite all this, Goncharov became the target of many satires and received a negative mention in Herzen's ''Kolokol''. "One of the best Russian authors shouldn't have taken this sort of job upon himself," critic Aleksander Druzhinin wrote in his diary. In 1856, as the official publishing policy hardened, Goncharov quit.

In the summer of 1857, Goncharov went to Marienbad for medical treatment. There he wrote ''Oblomov'', almost in its entirety. "It might seem strange, even impossible that in the course of one month the whole of the novel might be written... But it'd been growing in me for several years, so what I had to do then was just sit and write everything down," he later remembered. Goncharov's second novel '' Oblomov'' was published in 1859 in ''Otechestvennye Zapiski''. It had evolved from the earlier "Oblomov's Dream", which was later incorporated into the finished novel as Chapter 9. The novel caused much discussion in the Russian press, introduced another new term, ''oblomovshchina'', to the literary lexicon and is regarded as a Russian classic.

In his essay ''What Is Oblomovshchina?'' Nikolay Dobrolyubov provided an ideological background for the type of Russia's 'new man' exposed by Goncharov. The critic argued that, while several famous classic Russian literary characters – Onegin, Pechorin, and Rudin – bore symptoms of the 'Oblomov malaise', for the first time one single feature, that of social apathy, a self-destructive kind of laziness and unwillingness to even try and lift the burden of all-pervading inertia, had been brought to the fore and subjected to a thorough analysis.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in both Russian literature, Russian and world literature, and many of his works are consider ...

, among others, considered Goncharov a noteworthy author of high stature. Anton Chekhov

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (; ; 29 January 1860 – 15 July 1904) was a Russian playwright and short-story writer, widely considered to be one of the greatest writers of all time. His career as a playwright produced four classics, and his b ...

is quoted as stating that Goncharov was "...ten heads above me in talent." Turgenev, who fell out with Goncharov after the latter accused him of plagiarism (specifically of having used some of the characters and situations from ''The Precipice'', whose plan Goncharov had disclosed to him in 1855, in '' Home of the Gentry'' and '' On the Eve''), nevertheless declared: "As long as there is even one Russian alive, '' Oblomov'' will be remembered!"

''The Precipice''

A moderate conservative at heart, Goncharov greeted the

A moderate conservative at heart, Goncharov greeted the emancipation reform of 1861

The emancipation reform of 1861 in Russia, also known as the Edict of Emancipation of Russia, ( – "peasants' reform of 1861") was the first and most important of the liberal reforms enacted during the reign of Emperor Alexander II of Russia. T ...

, embraced the well-publicized notion of the government's readiness to "be at the helm of ocialprogress", and found himself in opposition to the revolutionary democrats. In the summer of 1862 he became an editor of ''Severnaya Potchta'' (The Northern Post), an official newspaper of the Interior Ministry, and a year later returned to the censorship committee.

In this second term Goncharov proved to be a harsh censor: he created serious problems for Nekrasov's ''Sovremennik'' and '' Russkoye Slovo'', where Dmitry Pisarev was now a leading figure. Openly condemning 'nihilistic

Nihilism () encompasses various views that reject certain aspects of existence. There have been different nihilist positions, including the views that life is meaningless, that moral values are baseless, and that knowledge is impossible. Thes ...

' tendencies and what he called "pathetic, imported doctrines of materialism

Materialism is a form of monism, philosophical monism according to which matter is the fundamental Substance theory, substance in nature, and all things, including mind, mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. Acco ...

, socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

, and communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

", Goncharov found himself the target of heavy criticism. In 1863 he became a member of the State Publishing Council and two years later joined the Russian government's Department of Publishing. All the while he was working on his third novel, '' The Precipice'', which came out in extracts: ''Sophia Nikolayevna Belovodova'' (a piece he himself was later skeptical about), ''Grandmother'' and ''Portrait''.

In 1867, Goncharov retired from his censorial position to devote himself entirely to writing ''The Precipice'', a book he later called "my heart's child", which took him twenty years to finish. Towards the end of this tormenting process Goncharov spoke of the novel as a "burden" and an "insurmountable task" that blocked his development and made him unable to advance as a writer. In a letter to Turgenev he confessed that, after finishing Part Three, he had toyed with the idea of abandoning the whole project.

In 1869, ''The Precipice'', a story of the romantic rivalry among three men, condemning nihilism as subverting the religious and moral values of Russia, was published in '' Vestnik Evropy''. Later critics came to see it as the final part of a trilogy, each part introducing a character typical of Russian high society of a certain period: first Aduev, then Oblomov, and finally Raisky, a gifted man, his artistic development halted by "lack of direction". According to scholar S. Mashinsky, as a social epic, ''The Precipice'' was superior to both ''The Same Old Story'' and ''Oblomov''.

The novel had considerable success, but the leftist press turned against its author. Saltykov-Shchedrin in ''Otechestvennye Zapiski'' ("The Street Philosophy", 1869), compared it unfavorably to ''Oblomov''. While the latter "had been driven by ideas assimilated by its author from the best men of the 1840s", ''The Precipice'' featured "a bunch of people wandering to and fro without any sense of direction, their lines of action having neither beginning nor end," according to the critic. Yevgeny Utin in ''Vestnik Evropy'' argued that Goncharov, like all writers of his generation, had lost touch with the new Russia. The controversial character Mark Volokhov, as leftist critics saw it, had been concocted to condemn 'nihilism' again, thus making the whole novel 'tendentious'. Yet, as Vladimir Korolenko later wrote, "Volokhov and all things related to him will be forgotten, as Gogol

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol; ; (; () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, and playwright of Ukrainian origin.

Gogol used the grotesque in his writings, for example, in his works " The Nose", " Viy", "The Overcoat", and " Nevsky Prosp ...

's ''Correspondence'' has been forgotten, while Goncharov's huge characters will remain in history, towering over all of those spiteful disputes of old."

Later years

Goncharov planned a fourth novel, set in the 1870s, but it failed to materialize. Instead he became a prolific critic, providing numerous theater and literature reviews; his "Myriad of Agonies" (Milyon terzaniy, 1871) is still regarded as one of the best essays on Alexandr Griboyedov's '' Woe from Wit''. Goncharov also wrote short stories: his ''Servants of an Old Age'' cycle as well as "The Irony of Fate", "Ukha" and others, described the life of rural Russia. In 1880 the first edition of ''The Complete Works of Goncharov'' was published. After the writer's death, it became known that he had burnt many later manuscripts.

Towards the end of his life Goncharov wrote an unusual memoir called '' An Uncommon Story'', in which he accused his literary rivals, first and foremost

Goncharov planned a fourth novel, set in the 1870s, but it failed to materialize. Instead he became a prolific critic, providing numerous theater and literature reviews; his "Myriad of Agonies" (Milyon terzaniy, 1871) is still regarded as one of the best essays on Alexandr Griboyedov's '' Woe from Wit''. Goncharov also wrote short stories: his ''Servants of an Old Age'' cycle as well as "The Irony of Fate", "Ukha" and others, described the life of rural Russia. In 1880 the first edition of ''The Complete Works of Goncharov'' was published. After the writer's death, it became known that he had burnt many later manuscripts.

Towards the end of his life Goncharov wrote an unusual memoir called '' An Uncommon Story'', in which he accused his literary rivals, first and foremost Ivan Turgenev

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev ( ; rus, links=no, Иван Сергеевич ТургеневIn Turgenev's day, his name was written ., p=ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf; – ) was a Russian novelist, short story writer, poe ...

, of having plagiarized his works and prevented him from achieving European fame. Some critics claimed that the book was the product of an unstable mind, while others praised it as an eye-opening, if controversial piece of writing. It wasn't published until 1924.

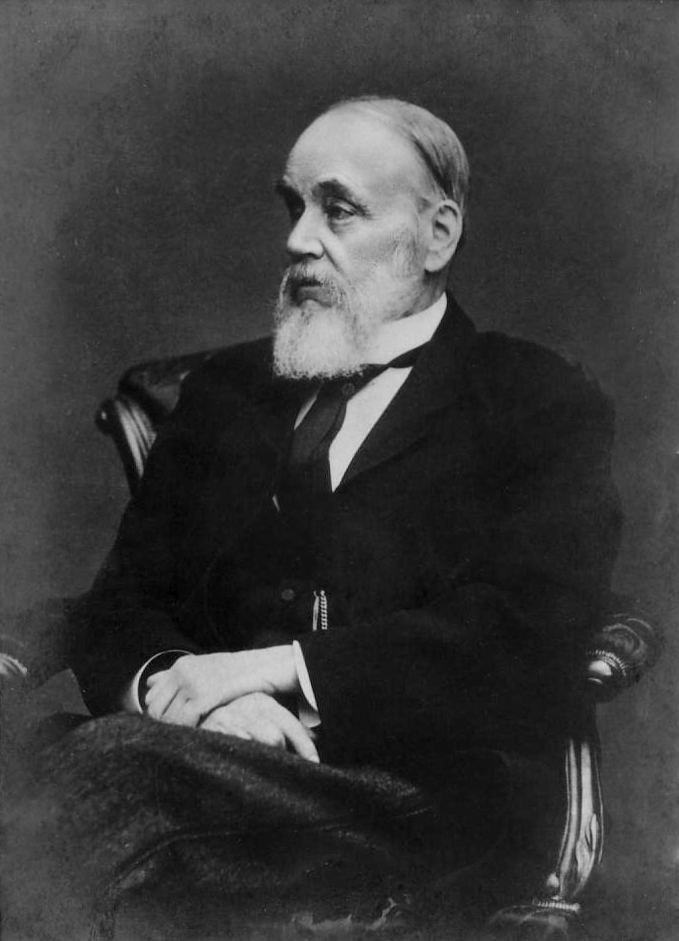

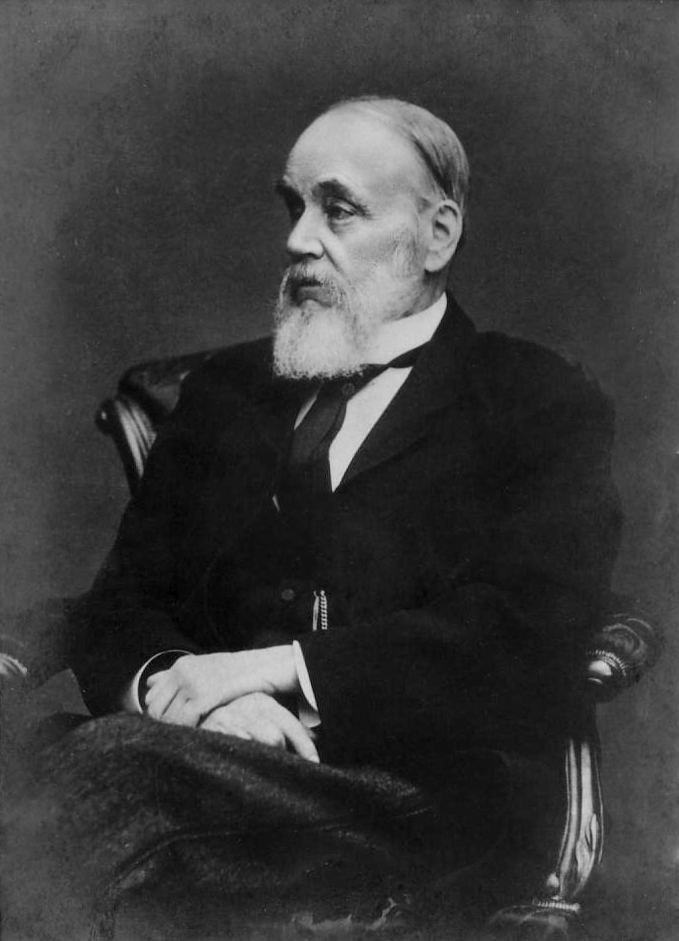

Goncharov, who never married, spent his last days absorbed in lonely and bitter recriminations because of the negative criticism some of his work had received. He died in Saint Petersburg on 27 September 1891, of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

. He was buried at the Novoye Nikolskoe Cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra

Saint Alexander Nevsky Lavra or Saint Alexander Nevsky Monastery was founded by Peter I of Russia in 1710 at the eastern end of the Nevsky Prospekt in Saint Petersburg, in the belief that this was the site of the Neva Battle in 1240 when Alexa ...

. In 1956 his ashes were moved to the Volkovo Cemetery in Leningrad

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

.

Selected bibliography

* ''Nimfodora Ivanovna'' (1836) - unpublished novella * "The Galloping Disease/A Cruel Illness" (1838) - short story * "A Happy Error" (1839) - short story * ''Ivan Savich Podzhabrin'' (1848) * '' The Same Old Story'' (Обыкновенная история, 1847) * ''Letters from a Friend in the Capital to a Bridegroom in the Provinces'' (1848) * '' Frigate "Pallada"'' (Фрегат "Паллада", 1858) * "Oblomov's Dream. An Episode from an Unfinished Novel", short story, later Chapter 9 in the 1859 novel as "Oblomov's Dream" ("Сон Обломова", 1849) * '' Oblomov'' (1859) * '' The Precipice'' (Обрыв, 1869)References

External links

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Goncharov, Ivan 1812 births 1891 deaths People from Ulyanovsk People from Simbirsky Uyezd Travel writers from the Russian Empire Critics from the Russian Empire Journalists from the Russian Empire Censors Translators from the Russian Empire Novelists from the Russian Empire Short story writers from the Russian Empire 19th-century male writers from the Russian Empire 19th-century essayists Imperial Moscow University alumni Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences Deaths from pneumonia in the Russian Empire Burials at Volkovo Cemetery