Italian Wars on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Italian Wars were a series of conflicts fought between 1494 and 1559, mostly in the Italian Peninsula, but later expanding into

Largely driven by the rivalry between the

Largely driven by the rivalry between the

The war began when

The war began when

The next phase of the conflict originated in the long-standing rivalry between Florence and the

The next phase of the conflict originated in the long-standing rivalry between Florence and the  Florence now asked for French assistance in retaking Pisa, a request Louis was in no hurry to fulfil since they had refused to support his capture of Milan. He was also initially occupied in defeating efforts to regain his duchy by Ludovico, who was captured at Novaro in April 1500 and spent the rest of his life in a French prison. However, Louis needed to maintain good relations with Florence, whose territory he would have to cross in order to conquer Naples, and on 29 June 1500 a combined Franco-Florentine army appeared outside Pisa. Once again, the French artillery quickly opened a gap in the walls but several assaults were repulsed and the siege was abandoned on 11 July.

With Milan firmly in his control, Louis returned to France and left the Florentines to blockade Pisa, which eventually surrendered in 1509. Anxious to begin the conquest of Naples, on 11 November he signed the

Florence now asked for French assistance in retaking Pisa, a request Louis was in no hurry to fulfil since they had refused to support his capture of Milan. He was also initially occupied in defeating efforts to regain his duchy by Ludovico, who was captured at Novaro in April 1500 and spent the rest of his life in a French prison. However, Louis needed to maintain good relations with Florence, whose territory he would have to cross in order to conquer Naples, and on 29 June 1500 a combined Franco-Florentine army appeared outside Pisa. Once again, the French artillery quickly opened a gap in the walls but several assaults were repulsed and the siege was abandoned on 11 July.

With Milan firmly in his control, Louis returned to France and left the Florentines to blockade Pisa, which eventually surrendered in 1509. Anxious to begin the conquest of Naples, on 11 November he signed the

On 18 October 1503, Pius III was replaced by

On 18 October 1503, Pius III was replaced by

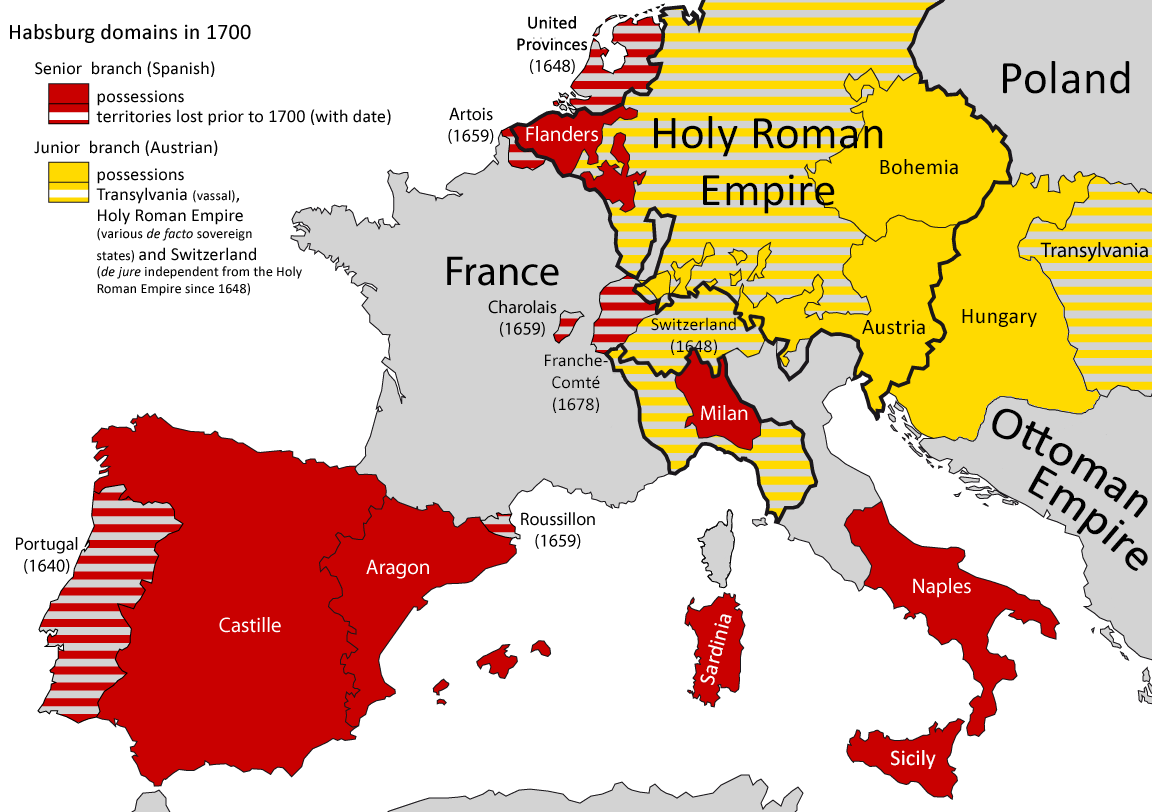

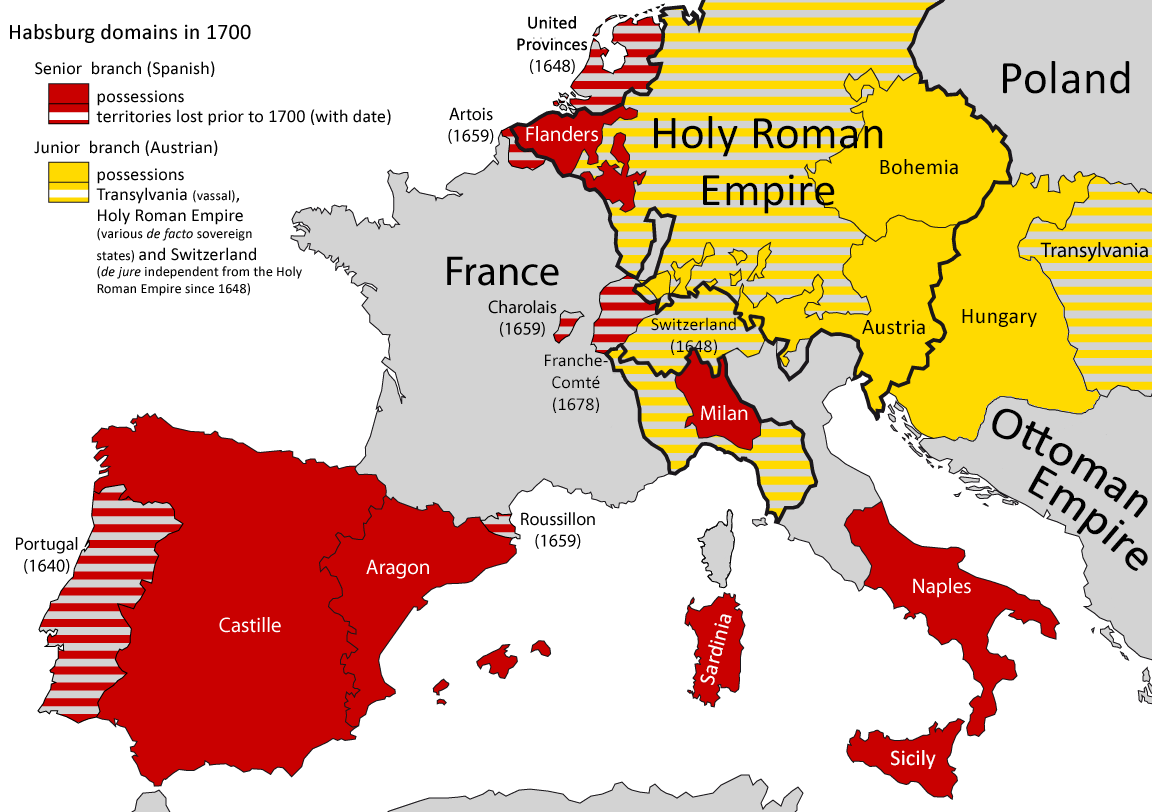

Following the death of Maximilian in January 1519, the German Princes elected Charles I of Spain as Emperor Charles V on 28 June. This brought Spain, the

Following the death of Maximilian in January 1519, the German Princes elected Charles I of Spain as Emperor Charles V on 28 June. This brought Spain, the

Supported by a Genoese fleet, in April 1528 a French expeditionary force besieged

Supported by a Genoese fleet, in April 1528 a French expeditionary force besieged

Under the Treaty of Cambrai, Francesco Sforza was reinstated as Duke of Milan; since he had no children, it also stated Charles V would inherit the duchy on his death, which occurred on 1 November 1535. Francis refused to accept this, arguing Milan was rightfully his along with Genoa and

Under the Treaty of Cambrai, Francesco Sforza was reinstated as Duke of Milan; since he had no children, it also stated Charles V would inherit the duchy on his death, which occurred on 1 November 1535. Francis refused to accept this, arguing Milan was rightfully his along with Genoa and

The 1538 truce failed to resolve underlying tensions between Francis, who still claimed Milan, and Charles, who insisted he comply with the treaties of Madrid and Cambrai. Their relationship collapsed in 1540 when Charles made his son

The 1538 truce failed to resolve underlying tensions between Francis, who still claimed Milan, and Charles, who insisted he comply with the treaties of Madrid and Cambrai. Their relationship collapsed in 1540 when Charles made his son

Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

, the Rhineland

The Rhineland ( ; ; ; ) is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly Middle Rhine, its middle section. It is the main industrial heartland of Germany because of its many factories, and it has historic ties to the Holy ...

and Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

. The primary belligerents were the Valois kings of France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, on one side, and their opponents in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

and Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

on the other. At different points, various Italian states participated in the war, some on both sides, with limited involvement from England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, Switzerland, and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

.

The Italic League

The Italic League or Most Holy League was an international agreement concluded in Venice on 30 August 1454, between the Papal States, the Republic of Venice, the Duchy of Milan, the Republic of Florence, and the Kingdom of Naples, following the Tr ...

established in 1454 achieved a balance of power in Italy, but fell apart after the death of its chief architect, Lorenzo de' Medici

Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici (), known as Lorenzo the Magnificent (; 1 January 1449 – 9 April 1492), was an Italian statesman, the ''de facto'' ruler of the Florentine Republic, and the most powerful patron of Renaissance culture in Italy. Lore ...

, in 1492. Combined with the ambition of Ludovico Sforza

Ludovico Maria Sforza (; 27 July 1452 – 27 May 1508), also known as Ludovico il Moro (; 'the Moor'), and called the "arbiter of Italy" by historian Francesco Guicciardini,

, its collapse allowed Charles VIII of France

Charles VIII, called the Affable (; 30 June 1470 – 7 April 1498), was King of France from 1483 to his death in 1498. He succeeded his father Louis XI at the age of 13. His elder sister Anne acted as regent jointly with her husband Peter II, Du ...

to invade Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

in 1494, which drew in Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. Although Charles was forced to withdraw in 1495, ongoing political divisions among the Italian states made them a battleground in the struggle for European domination between France and the Habsburgs.

Fought with considerable brutality, the wars took place against the background of religious turmoil caused by the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

, particularly in France and the Holy Roman Empire. They are seen as a turning point in the evolution from medieval to modern warfare, with the use of the arquebus

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

The term ''arquebus'' was applied to many different forms of firearms ...

or handgun becoming common, along with significant technological improvements in siege artillery. Literate commanders and modern printing methods also make them one of the first conflicts with a significant number of contemporary accounts, including those of Francesco Guicciardini

Francesco Guicciardini (; 6 March 1483 – 22 May 1540) was an Italian historian and politician, statesman. A friend and critic of Niccolò Machiavelli, he is considered one of the major political writers of the Italian Renaissance. In his maste ...

, Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli (3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527) was a Florentine diplomat, author, philosopher, and historian who lived during the Italian Renaissance. He is best known for his political treatise '' The Prince'' (), writte ...

, and Blaise de Montluc.

After 1503, most of the fighting was initiated by French invasions of Lombardy

The Lombardy Region (; ) is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in northern Italy and has a population of about 10 million people, constituting more than one-sixth of Italy's population. Lombardy is ...

and Piedmont

Piedmont ( ; ; ) is one of the 20 regions of Italy, located in the northwest Italy, Northwest of the country. It borders the Liguria region to the south, the Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna regions to the east, and the Aosta Valley region to the ...

, but although able to hold territory for periods of time, they could not do so permanently. By 1557, the growth of Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

meant the major belligerents faced internal conflict over religion, forcing them to refocus on domestic affairs. This led to the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis, under which France was largely expelled from Italy, but in exchange gained Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a French port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Calais is the largest city in Pas-de-Calais. The population of the city proper is 67,544; that of the urban area is 144,6 ...

from England, and the Three Bishoprics

The Three Bishoprics ( ) constituted a Provinces of France, government of the Kingdom of France consisting of the dioceses of Prince-Bishopric of Metz, Metz, Prince-Bishopric of Verdun, Verdun, and Prince-Bishopric of Toul, Toul within the Lorr ...

from Lorraine

Lorraine, also , ; ; Lorrain: ''Louréne''; Lorraine Franconian: ''Lottringe''; ; ; is a cultural and historical region in Eastern France, now located in the administrative region of Grand Est. Its name stems from the medieval kingdom of ...

. In turn, Spain acquired sovereignty over the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples (; ; ), officially the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was established by the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302). Until ...

and Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily (; ; ) was a state that existed in Sicily and the southern Italian peninsula, Italian Peninsula as well as, for a time, in Kingdom of Africa, Northern Africa, from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 until 1816. It was ...

in southern Italy, as well the Duchy of Milan

The Duchy of Milan (; ) was a state in Northern Italy, created in 1395 by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, then the lord of Milan, and a member of the important Visconti of Milan, Visconti family, which had been ruling the city since 1277. At that time, ...

in northern Italy.

Background

Largely driven by the rivalry between the

Largely driven by the rivalry between the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

and the Duchy of Milan

The Duchy of Milan (; ) was a state in Northern Italy, created in 1395 by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, then the lord of Milan, and a member of the important Visconti of Milan, Visconti family, which had been ruling the city since 1277. At that time, ...

, the long-running Wars in Lombardy had finally been ended by the 1454 Treaty of Lodi

The Treaty of Lodi, or Peace of Lodi, was a peace agreement to put an end to the Wars in Lombardy between the Venetian Republic and the Duchy of Milan, signed in the city of Lodi, Lombardy, Lodi on 9 April 1454.

The historical relevance of the ...

. Followed shortly thereafter by a non-aggression pact known as the Italic League

The Italic League or Most Holy League was an international agreement concluded in Venice on 30 August 1454, between the Papal States, the Republic of Venice, the Duchy of Milan, the Republic of Florence, and the Kingdom of Naples, following the Tr ...

, it led to a forty-year period of stability and economic expansion, marred only by the 1479 to 1481 Pazzi conspiracy and 1482 to 1484 War of Ferrara. The League's main supporter was the Florentine ruler Lorenzo de' Medici

Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici (), known as Lorenzo the Magnificent (; 1 January 1449 – 9 April 1492), was an Italian statesman, the ''de facto'' ruler of the Florentine Republic, and the most powerful patron of Renaissance culture in Italy. Lore ...

, who also pursued a policy of excluding France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

from the Italian peninsula.

Lorenzo's death in April 1492 severely weakened the League at a time when France was seeking to expand in Italy. This originated when Louis XI of France

Louis XI (3 July 1423 – 30 August 1483), called "Louis the Prudent" (), was King of France from 1461 to 1483. He succeeded his father, Charles VII. Louis entered into open rebellion against his father in a short-lived revolt known as the ...

inherited the County of Provence

Provence is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which stretches from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the France–Italy border, Italian border to the east; it is bordered by the Mediterrane ...

from his cousin Charles IV of Anjou

Charles IV, Duke of Anjou, also Charles of Maine, Count of Le Maine and Guise (1446 – 10 December 1481), was the son of the House of Valois-Anjou, Angevin prince Charles IV, Count of Maine, Charles of Maine, Count of Maine and Isabelle of Luxem ...

in 1481, along with the Angevin claim to the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples (; ; ), officially the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was established by the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302). Until ...

. His son Charles VIII succeeded him in 1483 and formally incorporated Provence into France in 1486; its ports of Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

and Toulon

Toulon (, , ; , , ) is a city in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the French Riviera and the historical Provence, it is the prefecture of the Var (department), Var department.

The Commune of Toulon h ...

provided direct access to the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

and thus the ability to pursue his territorial ambitions.

In the run-up to the First Italian War, Charles sought to secure the neutrality of other European rulers through a series of treaties. These included the November 1492 Peace of Étaples

Peace is a state of harmony in the absence of hostility and violence, and everything that discusses achieving human welfare through justice and peaceful conditions. In a societal sense, peace is commonly used to mean a lack of conflict (such ...

with Henry VII of England

Henry VII (28 January 1457 – 21 April 1509), also known as Henry Tudor, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizure of the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death in 1509. He was the first monarch of the House of Tudor.

Henr ...

and the March 1493 Treaty of Barcelona with Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

Maximilian I (22 March 1459 – 12 January 1519) was King of the Romans from 1486 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1508 until his death in 1519. He was never crowned by the Pope, as the journey to Rome was blocked by the Venetians. He proclaimed hi ...

.

History

Italian War of 1494–1495

The war began when

The war began when Ludovico Sforza

Ludovico Maria Sforza (; 27 July 1452 – 27 May 1508), also known as Ludovico il Moro (; 'the Moor'), and called the "arbiter of Italy" by historian Francesco Guicciardini,

, then Regent of Milan, encouraged Charles VIII of France to invade Italy, using the Angevin claim to the throne of Naples as a pretext. This in turn was driven by the intense rivalry between Ludovico's wife, Beatrice d'Este, and that of his nephew Gian Galeazzo Sforza, husband of Isabella of Aragon. Despite being the hereditary Duke of Milan, Gian Galeazzo had been sidelined by his uncle in 1481 and exiled to Pavia

Pavia ( , ; ; ; ; ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy, in Northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino (river), Ticino near its confluence with the Po (river), Po. It has a population of c. 73,086.

The city was a major polit ...

. Both women wanted to ensure their children inherited the Duchy and when Isabella's father became Alfonso II of Naples

Alfonso II (4 November 1448 – 18 December 1495) was Duke of Calabria and ruled as King of Naples from 25 January 1494 to 23 January 1495. He was a soldier and a patron of Renaissance architecture and the arts.

Heir to his father Fe ...

in January 1494, she asked for his help in securing their rights. In September Charles invaded the peninsula, which he justified by claiming he wanted to use Naples as a base for a crusade against the Ottoman Turks

The Ottoman Turks () were a Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group in Anatolia. Originally from Central Asia, they migrated to Anatolia in the 13th century and founded the Ottoman Empire, in which they remained socio-politically dominant for the e ...

.

In October, Ludovico formally became Duke of Milan following the death of Gian Galeazzo, who was popularly supposed to have been poisoned by his uncle, and the French marched through Italy virtually unopposed, entering Pisa

Pisa ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Tuscany, Central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for the Leaning Tow ...

on 8 November, Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

on 17th, and Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

on 31 December. Charles was backed by Girolamo Savonarola

Girolamo Savonarola, OP (, ; ; 21 September 1452 – 23 May 1498), also referred to as Jerome Savonarola, was an ascetic Dominican friar from Ferrara and a preacher active in Renaissance Florence. He became known for his prophecies of civic ...

, who used the opportunity to established a short-lived theocracy in Florence, while Pope Alexander VI

Pope Alexander VI (, , ; born Roderic Llançol i de Borja; epithet: ''Valentinus'' ("The Valencian"); – 18 August 1503) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 11 August 1492 until his death in 1503.

Born into t ...

allowed his army free passage through the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

.

In February 1495, the French reached Monte San Giovanni Campano in the Kingdom of Naples and despatched envoys to negotiate terms with its Neapolitan garrison, who murdered them and sent their mutilated bodies back to the French lines. On 9 February, the enraged besiegers breached the walls of the castle with artillery fire, then stormed it, killing everyone inside. Known as the "Sack of Naples", widespread outrage within Italy allied with concern over the power of France led to the formation of the League of Venice on 31 March 1495, an anti-French alliance composed of Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

, Milan, Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, and the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

.

Later joined by Florence, following the overthrow of Savonarola, the Papal States and Mantua

Mantua ( ; ; Lombard language, Lombard and ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Italian region of Lombardy, and capital of the Province of Mantua, eponymous province.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the "Italian Capital of Culture". In 2 ...

, this coalition cut off Charles and his army from their bases in France. Charles' cousin, Louis d'Orleans, now tried to take advantage of Ludovico's change of sides to conquer Milan, which he claimed through his grandmother, Valentina Visconti. On 11 June, he captured Novara

Novara (; Novarese Lombard, Novarese: ) is the capital city of the province of Novara in the Piedmont (Italy), Piedmont region in northwest Italy, to the west of Milan. With 101,916 inhabitants (on 1 January 2021), it is the second most populous ...

when the garrison defected, and reached Vigevano

Vigevano (; ) is a (municipality) in the province of Pavia, in the Italian region of Lombardy. A historic art town, it is also renowned for shoemaking and is one of the main centres of Lomellina, a rice-growing agricultural district. Vigevano ...

, forty kilometres from Milan. At this crucial point, Ludovico was incapacitated either by a stroke

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to a part of the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemor ...

or nervous breakdown, while his unpaid soldiers were on the verge of mutiny. In his absence, his wife Beatrice d'Este took personal control of the Duchy and the siege of Novara, with Louis eventually forced to surrender in return for his freedom.

Having replaced Ferdinand II of Naples with a pro-French government, Charles turned north and on 6 July was intercepted by the League outside Fornovo di Taro

Fornovo di Taro () is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the province of Parma, in the Italy, Italian region Emilia-Romagna, located about west of Bologna and about southwest of Parma. The town lies on the east bank of the Taro (river), Taro River. ...

. In the resulting Battle of Fornovo, the French forced their opponents back across the Taro river and continued onto Asti

Asti ( , ; ; ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) of 74,348 inhabitants (1–1–2021) located in the Italy, Italian region of Piedmont, about east of Turin, in the plain of the Tanaro, Tanaro River. It is the capital of the province of Asti and ...

, leaving most of their supplies behind. Both sides claimed victory but the general consensus favoured the French, since the League suffered heavier casualties and failed to halt their retreat, the reason for fighting in the first place. In the south, despite some initial reverses, by September 1495 Ferdinand II had regained control of his kingdom. Although the French invasion achieved little, it showed the Italian states were rich and comparatively weak, making future intervention attractive to outside powers. Charles himself died on 7 April 1498, and was succeeded by the former Duke of Orleans, who became Louis XII.

Italian Wars of 1499–1504

The next phase of the conflict originated in the long-standing rivalry between Florence and the

The next phase of the conflict originated in the long-standing rivalry between Florence and the Republic of Pisa

The Republic of Pisa () was an independent state existing from the 11th to the 15th century centered on the Tuscan city of Pisa. It rose to become an economic powerhouse, a commercial center whose merchants dominated Mediterranean and Italian t ...

, which had been annexed by Florence in 1406 but took advantage of the French invasion to regain its independence in 1494. Despite Charles' retreat in 1495, Pisa continued to receive support from Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, Venice and Milan, all of whom were suspicious of Florentine power. In order to strengthen his own position, Ludovico once again invited an external power to settle an internal Italian affair, in this case Emperor Maximilian I. In doing so, Maximilian hoped to bolster the League of Venice, which he viewed as an essential barrier to French intervention, but Florence was convinced he favoured Pisa and refused to accept mediation. To enforce a settlement, in July 1496 Maximilian besieged the Florentine city of Livorno

Livorno () is a port city on the Ligurian Sea on the western coast of the Tuscany region of Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Livorno, having a population of 152,916 residents as of 2025. It is traditionally known in English as Leghorn ...

, but withdrew in September due to shortages of men and supplies.

Following the death of Charles VIII in April 1498, Louis XII began planning another attempt on Milan, while also pursuing his predecessor's claim to the Kingdom of Naples. Aware of the hostility caused by French ambitions in Italy, in July 1498 he renewed the 1492 Peace of Étaples

Peace is a state of harmony in the absence of hostility and violence, and everything that discusses achieving human welfare through justice and peaceful conditions. In a societal sense, peace is commonly used to mean a lack of conflict (such ...

with England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

and signed a treaty confirming French borders with Burgundy

Burgundy ( ; ; Burgundian: ''Bregogne'') is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. ...

. This was followed in August by the Treaty of Marcoussis

Marcoussis () is a Communes of France, commune in the southern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the Kilometre Zero, center of Paris.

Marcoussis is the location of the CNR (National Centre of Rugby) where the France national rugby u ...

with Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II, also known as Ferdinand I, Ferdinand III, and Ferdinand V (10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), called Ferdinand the Catholic, was King of Aragon from 1479 until his death in 1516. As the husband and co-ruler of Queen Isabella I of ...

; although it did not address outstanding territorial disputes between the two countries, it agreed "have all enemies in common except the Pope." On 9 February 1499, Louis signed the Treaty of Blois, a military alliance with Venice against Ludovico.

With these agreements finalised, a French army of 27,000 under the Milanese exile Gian Giacomo Trivulzio invaded Lombardy

The Lombardy Region (; ) is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in northern Italy and has a population of about 10 million people, constituting more than one-sixth of Italy's population. Lombardy is ...

, and in August besieged Rocca d'Arazzo, a fortified town in the western part of the Duchy of Milan. The French siege artillery breached the walls in less than five hours and after the town capitulated, Louis ordered the execution of its garrison and senior members of the civil administration. Other Milanese strongholds surrendered rather than face the same fate, while Ludovico, whose wife Beatrice had died in 1497, fled the duchy with his children and took refuge with Maximilian. On 6 October 1499, Louis made a triumphant entry into Milan.

Florence now asked for French assistance in retaking Pisa, a request Louis was in no hurry to fulfil since they had refused to support his capture of Milan. He was also initially occupied in defeating efforts to regain his duchy by Ludovico, who was captured at Novaro in April 1500 and spent the rest of his life in a French prison. However, Louis needed to maintain good relations with Florence, whose territory he would have to cross in order to conquer Naples, and on 29 June 1500 a combined Franco-Florentine army appeared outside Pisa. Once again, the French artillery quickly opened a gap in the walls but several assaults were repulsed and the siege was abandoned on 11 July.

With Milan firmly in his control, Louis returned to France and left the Florentines to blockade Pisa, which eventually surrendered in 1509. Anxious to begin the conquest of Naples, on 11 November he signed the

Florence now asked for French assistance in retaking Pisa, a request Louis was in no hurry to fulfil since they had refused to support his capture of Milan. He was also initially occupied in defeating efforts to regain his duchy by Ludovico, who was captured at Novaro in April 1500 and spent the rest of his life in a French prison. However, Louis needed to maintain good relations with Florence, whose territory he would have to cross in order to conquer Naples, and on 29 June 1500 a combined Franco-Florentine army appeared outside Pisa. Once again, the French artillery quickly opened a gap in the walls but several assaults were repulsed and the siege was abandoned on 11 July.

With Milan firmly in his control, Louis returned to France and left the Florentines to blockade Pisa, which eventually surrendered in 1509. Anxious to begin the conquest of Naples, on 11 November he signed the Treaty of Granada

The Treaty of Granada, also known as the Surrender of Granada or the Capitulations, was signed and ratified on November 25, 1491, between Boabdil, the sultan of Granada, and Ferdinand and Isabella, the King and Queen of Castile, León, Aragon ...

with Ferdinand II of Aragon, an agreement to divide the kingdom between the two. Since Ferdinand had supported the expulsion of the French from Naples in 1495, Louis hoped these concessions would allow him to acquire the bulk of the kingdom without an expensive war. His action was criticised by contemporaries like Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli (3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527) was a Florentine diplomat, author, philosopher, and historian who lived during the Italian Renaissance. He is best known for his political treatise '' The Prince'' (), writte ...

and modern historians, who argue the 1499 Treaty of Marcoussis already gave Louis everything he needed, while inviting Spain into Naples could only work to his detriment.

In July 1501, the French army reached Capua

Capua ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' in the province of Caserta, in the region of Campania, southern Italy, located on the northeastern edge of the Campanian plain.

History Ancient era

The name of Capua comes from the Etruscan ''Capeva''. The ...

; strongly defended by forces loyal to Frederick of Naples, it surrendered on 24 July after a short siege but was then sacked. In addition to the extensive material destruction, many women were subjected to mass rape and estimates of the dead ranged from 2,000 to 4,000, actions that caused consternation throughout Italy. Resistance crumbled as other towns tried to avoid the same fate and on 12 October Louis appointed the Duke of Nemours Duke of Nemours was a title in the Peerage of France. The name refers to Nemours in the Île-de-France region of north-central France.

History

In the 12th and 13th centuries, the Lordship of Nemours, in the Gâtinais, France, was a possession of th ...

his viceroy in Naples. However, the Treaty of Granada had left the ownership of key Neapolitan territories undecided and disputes over these quickly poisoned relationships between the two powers. This led to war in late 1502, which ended with the French being expelled from Naples once again after defeats at Cerignola

Cerignola (; ) is a town and ''comune'' of Apulia, Italy, in the province of Foggia, southeast from the town of Foggia. It has the third-largest land area of any ''comune'' in Italy, at , after Rome and Ravenna and it has the largest land ar ...

on 28 April 1503, and Garigliano on 29 December.

War of the League of Cambrai

On 18 October 1503, Pius III was replaced by

On 18 October 1503, Pius III was replaced by Pope Julius II

Pope Julius II (; ; born Giuliano della Rovere; 5 December 144321 February 1513) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1503 to his death, in February 1513. Nicknamed the Warrior Pope, the Battle Pope or the Fearsome ...

, who as ruler of the Papal States was concerned by Venetian power in northern Italy. This fear was shared by his home town of Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, which also resented its expulsion from the Po Valley

The Po Valley, Po Plain, Plain of the Po, or Padan Plain (, , or ) is a major geographical feature of northern Italy. It extends approximately in an east-west direction, with an area of including its Venetian Plain, Venetic extension not actu ...

, and Maximilian, whose acquisition of Gorizia

Gorizia (; ; , ; ; ) is a town and (municipality) in northeastern Italy, in the autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia. It is located at the foot of the Julian Alps, bordering Slovenia. It is the capital of the Province of Gorizia, Region ...

in 1500 was threatened by Venetian possession of neighbouring Friuli

Friuli (; ; or ; ; ) is a historical region of northeast Italy. The region is marked by its separate regional and ethnic identity predominantly tied to the Friulians, who speak the Friulian language. It comprises the major part of the autono ...

. Milan, controlled by Louis XII, was a long-standing opponent of Venice, while Ferdinand II, now king of Naples, wished to regain control of Venetian ports on the southern Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

coast. Along with the Duchy of Ferrara

The Duchy of Ferrara (; ; ) was a state in what is now northern Italy. It consisted of about 1,100 km2 south of the lower Po River, stretching to the valley of the lower Reno River, including the city of Ferrara. The territory that was part ...

, Julius united these disparate interests into the anti-Venetian League of Cambrai, signed on 10 December 1508.

Although the French largely destroyed a Venetian army at Agnadello on 14 May 1509, Maximilian failed to capture Padua

Padua ( ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Veneto, northern Italy, and the capital of the province of Padua. The city lies on the banks of the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice and southeast of Vicenza, and has a population of 20 ...

and withdrew from Italy. Now seeing the power of Louis XII as the greater threat, in February 1510 Pope Julius made peace with Venice, followed in March by an agreement with the Swiss Cantons to supply him with 6,000 mercenaries. After a year of fighting in which Louis XII occupied large parts of the Papal States, in October 1511 Julius formed the anti-French Holy League, which included Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

, Maximilian and Spain.

A French army defeated the Spanish at Ravenna

Ravenna ( ; , also ; ) is the capital city of the Province of Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. It was the capital city of the Western Roman Empire during the 5th century until its Fall of Rome, collapse in 476, after which ...

on 11 April 1512, but their leader Gaston de Foix was killed, while the Swiss recaptured Milan and restored Ludovico's son Massimiliano Sforza as duke. The members of the League then fell out over dividing the spoils and the death of Pope Julius on 20 February 1513 left it without effective leadership. In March, Venice and France formed an alliance, but from June to September 1513 the League won victories at Novara

Novara (; Novarese Lombard, Novarese: ) is the capital city of the province of Novara in the Piedmont (Italy), Piedmont region in northwest Italy, to the west of Milan. With 101,916 inhabitants (on 1 January 2021), it is the second most populous ...

and La Motta in Lombardy, Guinegate in Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

and Flodden in England. Despite this, fighting continued in Italy, with neither side able to gain a decisive advantage.

On 1 January 1515, Louis XII died and was succeeded by his son-in-law, Francis I, who took up his predecessor's cause and routed the Swiss at Marignano on 13–14 September 1515. Combined with the unpopularity of Massiliano Sforza, victory allowed Francis to retake Milan and the Holy League collapsed as both Spain and Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X (; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 14751 December 1521) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1513 to his death in December 1521.

Born into the prominent political and banking Med ...

saw little benefit in fighting on. In the treaty of Noyon

Noyon (; ; , Noviomagus of the Viromandui, Veromandui, then ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Oise Departments of France, department, Northern France.

Geography

Noyon lies on the river Oise (river), Oise, about northeast of Paris. The ...

, signed on 13 August 1516, Charles I of Spain

Charles V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain (as Charles I) from 1516 to 1556, and Lord of the Netherlands as titular Duke of Burgundy (as Charles II) fr ...

acknowledged Francis as Duke of Milan, while Francis "passed" his claim to Naples onto Charles. Left isolated, in December Maximilian signed the Treaty of Brussels, which confirmed French possession of Milan.

Italian War of 1521–1526

Following the death of Maximilian in January 1519, the German Princes elected Charles I of Spain as Emperor Charles V on 28 June. This brought Spain, the

Following the death of Maximilian in January 1519, the German Princes elected Charles I of Spain as Emperor Charles V on 28 June. This brought Spain, the Low Countries

The Low Countries (; ), historically also known as the Netherlands (), is a coastal lowland region in Northwestern Europe forming the lower Drainage basin, basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting today of the three modern "Bene ...

and the Holy Roman Empire under one ruler, and meant France was surrounded by the so-called "Habsburg ring". Francis I had also been a candidate for the Imperial throne, adding a personal dimension to his rivalry with Charles that became one of the fundamental conflicts of the sixteenth century.

Planning an offensive against Habsburg possessions in Navarre

Navarre ( ; ; ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre, is a landlocked foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Autonomous Community, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and New Aquitaine in France. ...

and Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

, Francis first secured his position in Italy by agreeing a new alliance with Venice. As Leo X had backed his candidacy for Emperor, he also counted on Papal support but Leo sided with Charles in return for his help against Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

and his proposed reforms to the Catholic church. In November 1521, an Imperial-Papal army under Prospero Colonna

Prospero Colonna (1452–1523), sometimes referred to as Prosper Colonna, was an Italian condottiero. He was active during the Italian wars and served France, Spain, the Holy Roman Empire and various Italian states.

His military career spanned ...

and the Marquis of Pescara captured Milan and restored Francesco Sforza as duke. After Leo died in December, Adrian VI was elected Pope on 9 January 1522, while a French attempt to retake Milan was ended by defeat at Bicocca on 27 April.

In May 1522, England joined the Imperial alliance and declared war on France. Venice left the war in July 1523, while Adrian died in November and was succeeded by Clement VII, who tried to negotiate an end to the fighting without success. Although France had lost ground in Lombardy and been invaded by English, Imperial and Spanish armies, her opponents had differing objectives and failed to co-ordinate their attacks. Since Papal policy was to prevent either France or the Empire from becoming too powerful, in late 1524 Clement secretly allied himself with Francis, enabling him to mount another offensive against Milan. On 24 February 1525, the French army suffered a devastating defeat at Pavia

Pavia ( , ; ; ; ; ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy, in Northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino (river), Ticino near its confluence with the Po (river), Po. It has a population of c. 73,086.

The city was a major polit ...

, in which Francis was captured and imprisoned in Spain.

This led to frantic diplomatic manoeuvres to secure his release, including a French mission to Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I (; , ; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the Western world and as Suleiman the Lawgiver () in his own realm, was the List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman sultan between 1520 a ...

, asking for Ottoman assistance. Although Suleiman avoided involvement on this occasion, it was the beginning of a long-standing, if often unacknowledged, Franco-Turkish relationship. Francis was eventually released in March 1526 after signing the Treaty of Madrid, in which he renounced French claims to Artois

Artois ( , ; ; Picard: ''Artoé;'' English adjective: ''Artesian'') is a region of northern France. Its territory covers an area of about 4,000 km2 and it has a population of about one million. Its principal cities include Arras (Dutch: ...

, Milan and Burgundy

Burgundy ( ; ; Burgundian: ''Bregogne'') is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. ...

.

War of the League of Cognac

Once Francis was free, his Council renounced the Treaty of Madrid, claiming conditions extorted under duress could not be considered binding. Concerned that Imperial power now posed a threat to Papal independence, on 22 May 1526 Clement VII formed the League of Cognac, whose members included France, the Papal States, Venice, Florence and Milan. Many of the Imperial troops were close to mutiny having not been paid for months and theDuke of Urbino

The Duchy of Urbino () was an independent duchy in early modern central Italy, corresponding to the northern half of the modern region of Marche. It was directly annexed by the Papal States in 1631.

It was bordered by the Adriatic Sea in the ea ...

, commander of the League army, hoped to take advantage of this confusion. However, he delayed taking the offensive awaiting additional Swiss reinforcements.

Although the League gained an easy victory on 24 June when the Venetians occupied Lodi, this delay allowed Charles to gather fresh troops and support a Milanese revolt in July against Francesco Sforza, who was once again forced into exile. In September, Charles financed an attack on Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

by the Colonna family

The House of Colonna is an Italian noble family, forming part of the papal nobility. It played a pivotal role in Middle Ages, medieval and Roman Renaissance, Renaissance Rome, supplying one pope (Pope Martin V, Martin V), 23 cardinals and many ot ...

, who competed with the rival Orsinis for control of the city, and Clement was forced to pay them to withdraw. Seeking to recapture Milan, Francis invaded Lombardy at the beginning of 1527, with an army financed by Henry VIII, who hoped thereby to win Papal support for divorcing his first wife, Katherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine,

historical Spanish: , now: ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was Queen of England as the first wife of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 11 June 1509 until its annulment on 23 May ...

.

In May, Imperial troops, many of whom were followers of Martin Luther, sacked Rome and besieged Clement in the Castel Sant'Angelo, while Urbino and the League army sat outside and failed to intervene. Although the French marched south to relieve Rome, they were too late to prevent Clement making peace with Charles V in November. Meanwhile, Venice, the largest and most powerful of the Italian states and which also possessed the most effective army, now refused to contribute any more troops to the League. Weakened by its losses in 1509 to 1517 and with its maritime possessions increasingly threatened by the Ottomans, under Andrea Gritti the Republic tried to remain neutral and after 1529 avoided participation in the fighting.

Supported by a Genoese fleet, in April 1528 a French expeditionary force besieged

Supported by a Genoese fleet, in April 1528 a French expeditionary force besieged Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

before disease forced them to withdraw in August. Both sides were now anxious to end the war and after another French defeat at Landriano on 21 June 1529, Francis agreed the Treaty of Cambrai with Charles in August. Known as the "Peace of the Ladies" because it was negotiated by Francis's mother, Louise of Savoy

Louise of Savoy (11 September 1476 – 22 September 1531) was a French noble and regent, Duchess ''suo jure'' of Auvergne (province), Auvergne and House of Bourbon, Bourbon, Duchess of Nemours and the mother of King Francis I of France, Francis I ...

, and Charles's aunt Margaret

Margaret is a feminine given name, which means "pearl". It is of Latin origin, via Ancient Greek and ultimately from Iranian languages, Old Iranian. It has been an English language, English name since the 11th century, and remained popular thro ...

, Francis recognised Charles as ruler of Milan, Naples, Flanders and Artois. Venice also made peace, leaving only Florence, which had expelled their Medici

The House of Medici ( , ; ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first consolidated power in the Republic of Florence under Cosimo de' Medici and his grandson Lorenzo "the Magnificent" during the first half of the 15th ...

rulers in 1527. At Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

in the summer of 1529, Charles V was named King of Italy

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a constitutional monarch if his power is restrained by ...

; he agreed to restore the Medici on behalf of Pope Clement, who was himself a Medici, and after a lengthy siege

A siege () . is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by well-prepared assault. Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict charact ...

, Florence surrendered in August 1530.

Prior to 1530, interference by foreign powers in Italy was viewed as a short-term problem, since they could not sustain it over time; for example, French conquests of Naples in 1494 and 1501 and Milan in 1499 and 1515 were quickly reversed. On the other hand, Venice was generally viewed by other states as the greatest threat because it was an ''Italian'' power. Many assumed the primacy established at Bologna by Charles V in Italy would also soon pass but instead it was the start of a long period of Imperial dominance. One factor was Venice's withdrawal from Italian affairs after 1530 in favour of protecting its maritime empire from Ottoman expansion.

Italian War of 1536–1538

Under the Treaty of Cambrai, Francesco Sforza was reinstated as Duke of Milan; since he had no children, it also stated Charles V would inherit the duchy on his death, which occurred on 1 November 1535. Francis refused to accept this, arguing Milan was rightfully his along with Genoa and

Under the Treaty of Cambrai, Francesco Sforza was reinstated as Duke of Milan; since he had no children, it also stated Charles V would inherit the duchy on his death, which occurred on 1 November 1535. Francis refused to accept this, arguing Milan was rightfully his along with Genoa and Asti

Asti ( , ; ; ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) of 74,348 inhabitants (1–1–2021) located in the Italy, Italian region of Piedmont, about east of Turin, in the plain of the Tanaro, Tanaro River. It is the capital of the province of Asti and ...

, and once again prepared for war. In April 1536, pro-Valois elements in Asti expelled the Imperial garrison and a French army under Philippe de Chabot occupied Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

, although they failed to take Milan.

In response, a Spanish army invaded Provence

Provence is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which stretches from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the France–Italy border, Italian border to the east; it is bordered by the Mediterrane ...

and captured Aix on 13 August 1536, before withdrawing, a fruitless expedition that diverted resources from Italy, where the situation had become more serious. The 1536 Franco-Ottoman alliance

The Franco-Ottoman alliance, also known as the Franco-Turkish alliance, was an alliance established in 1536 between Francis I of France, Francis I, King of France and Suleiman the Magnificent, Suleiman I of the Ottoman Empire. The strategic and s ...

, a comprehensive treaty covering a wide range of commercial and diplomatic issues, also agreed to a joint assault on Genoa, with French land forces supported by an Ottoman fleet.

Finding the garrison of Genoa had recently been reinforced while a planned internal uprising failed to materialise, the French instead occupied the towns of Pinerolo, Chieri and Carmagnola in Piedmont. Fighting continued in Flanders and northern Italy throughout 1537, while the Ottoman fleet raided the coastal areas around Naples, raising fears of invasion throughout Italy. Pope Paul III

Pope Paul III (; ; born Alessandro Farnese; 29 February 1468 – 10 November 1549) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 October 1534 to his death, in November 1549.

He came to the papal throne in an era follo ...

, who had replaced Clement in 1534, grew increasingly anxious to end the war and brought the two sides together at Nice

Nice ( ; ) is a city in and the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative city limits, with a population of nearly one millionSavoy

Savoy (; ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps. Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south and west and to the Aosta Vall ...

, Piedmont and Artois.

Italian War of 1542–1546

The 1538 truce failed to resolve underlying tensions between Francis, who still claimed Milan, and Charles, who insisted he comply with the treaties of Madrid and Cambrai. Their relationship collapsed in 1540 when Charles made his son

The 1538 truce failed to resolve underlying tensions between Francis, who still claimed Milan, and Charles, who insisted he comply with the treaties of Madrid and Cambrai. Their relationship collapsed in 1540 when Charles made his son Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male name derived from the Macedonian Old Koine language, Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominen ...

Duke of Milan, thus precluding any possibility it would revert to France. In 1541, Charles made a disastrous attack on Ottoman port of Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

, which severely weakened his military and led Suleiman to reactivate his French alliance. With Ottoman support, on 12 July 1542 Francis once again declared war on the Holy Roman Empire, initiating the Italian War of 1542–46.

In August, French armies attacked Perpignan

Perpignan (, , ; ; ) is the prefectures in France, prefecture of the Pyrénées-Orientales departments of France, department in Southern France, in the heart of the plain of Roussillon, at the foot of the Pyrenees a few kilometres from the Me ...

on the Spanish border, as well as Artois, Flanders and Luxemburg, a Valois possession prior to 1477. Imperial resistance proved far more formidable than expected, with most of these attacks easily repulsed and in 1543 Henry VIII allied with Charles and agreed to support his offensive in Flanders. Neither side made much progress, and although a combined Franco-Ottoman fleet under Hayreddin Barbarossa

Hayreddin Barbarossa (, original name: Khiḍr; ), also known as Hayreddin Pasha, Hızır Hayrettin Pasha, and simply Hızır Reis (c. 1466/1483 – 4 July 1546), was an Ottoman corsair and later admiral of the Ottoman Navy. Barbarossa's ...

captured Nice on 22 August and besieged the citadel, the onset of winter and presence of a Spanish fleet forced them to withdraw. A joint attack by Christian and Islamic troops on a Christian town was regarded as shocking, especially when Francis allowed Barbarossa to use the French port of Toulon

Toulon (, , ; , , ) is a city in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the French Riviera and the historical Provence, it is the prefecture of the Var (department), Var department.

The Commune of Toulon h ...

as a winter base.

On 14 April 1544, a French army commanded by Francis, Count of Enghien, defeated the Imperials at Ceresole, a victory of limited strategic value since they failed to make progress elsewhere in Lombardy. The Imperial position was further strengthened at Serravalle in June, when Alfonso d'Avalos defeated a mercenary force led by the Florentine exile Piero Strozzi on their way to meet Enghien. An English army captured Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; ; ; or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Hauts-de-France, Northern France. It is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Pas-de-Calais. Boul ...

on 10 September, while Imperial forces advanced to within of Paris. However, with his treasury exhausted and concerned by Ottoman naval strength in the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

, on 14 September Charles agreed the Treaty of Crépy with Francis, which essentially restored the position to that prevailing in 1542. The agreement excluded Henry VIII, whose war with France continued until the two countries made peace in 1546 and confirmed his possession of Boulogne.

Italian War of 1551–1559

Francis died on 31 March 1547 and was succeeded by his son,Henry II of France

Henry II (; 31 March 1519 – 10 July 1559) was List of French monarchs#House of Valois-Angoulême (1515–1589), King of France from 1547 until his death in 1559. The second son of Francis I of France, Francis I and Claude of France, Claude, Du ...

. He continued attempts to restore the French position in Italy, encouraged by Italian exiles and his cousin Francis, Duke of Guise, who claimed the throne of Naples through his grandfather René II, Duke of Lorraine

René II (2 May 1451 – 10 December 1508) was Count of Vaudémont from 1470, Duke of Lorraine from 1473, and Duke of Bar from 1483 to 1508. He claimed the crown of the Kingdom of Naples and the County of Provence as the Duke of Calabria ...

. Henry first strengthened his diplomatic position by reactivating the Franco-Ottoman alliance and supporting their capture of Tripoli in August 1551. Despite his devout personal Catholicism and persecution of Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

"heretics" at home, in January 1552 he signed the Treaty of Chambord

The Treaty of Chambord was an agreement signed on 15 January 1552 at the Château de Chambord between the Catholic King Henry II of France and three Protestant princes of the Holy Roman Empire led by Elector Maurice of Saxony. Based on the terms ...

with several Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

princes within the Empire, which gave him control of the Three Bishoprics

The Three Bishoprics ( ) constituted a Provinces of France, government of the Kingdom of France consisting of the dioceses of Prince-Bishopric of Metz, Metz, Prince-Bishopric of Verdun, Verdun, and Prince-Bishopric of Toul, Toul within the Lorr ...

of Toul

Toul () is a Communes of France, commune in the Meurthe-et-Moselle Departments of France, department in north-eastern France.

It is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture of the department.

Geography

Toul is between Commercy and Nancy, Fra ...

, Verdun

Verdun ( , ; ; ; official name before 1970: Verdun-sur-Meuse) is a city in the Meuse (department), Meuse departments of France, department in Grand Est, northeastern France. It is an arrondissement of the department.

In 843, the Treaty of V ...

, and Metz

Metz ( , , , then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle (river), Moselle and the Seille (Moselle), Seille rivers. Metz is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Moselle (department), Moselle Departments ...

.

Following the outbreak of the Second Schmalkaldic War in March 1552, French troops occupied the Three Bishoprics and invaded Lorraine

Lorraine, also , ; ; Lorrain: ''Louréne''; Lorraine Franconian: ''Lottringe''; ; ; is a cultural and historical region in Eastern France, now located in the administrative region of Grand Est. Its name stems from the medieval kingdom of ...

. In 1553, a Franco-Ottoman force captured the Genoese island of Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

, while supported by Henry's wife, Catherine de' Medici

Catherine de' Medici (, ; , ; 13 April 1519 – 5 January 1589) was an Italian Republic of Florence, Florentine noblewoman of the Medici family and Queen of France from 1547 to 1559 by marriage to Henry II of France, King Henry II. Sh ...

, French-backed Tuscan exiles seized control of Siena. This brought Henry into conflict with the ruler of Florence, Cosimo de' Medici

Cosimo di Giovanni de' Medici (27 September 1389 – 1 August 1464) was an Italian banker and politician who established the House of Medici, Medici family as effective rulers of Florence during much of the Italian Renaissance. His power derive ...

, who defeated a French army at Marciano on 2 August 1554; although Siena held out until April 1555, it was absorbed by Florence and in 1569 became part of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany

The Grand Duchy of Tuscany (; ) was an Italian monarchy located in Central Italy that existed, with interruptions, from 1569 to 1860, replacing the Republic of Florence. The grand duchy's capital was Florence. In the 19th century the population ...

.

In July 1554, Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

became king of England through his marriage to Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain as the wife of King Philip II from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She made vigorous a ...

, and in November he also received the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

from his father, who reconfirmed him as Duke of Milan. In January 1556, Charles formally abdicated as Emperor and split his possessions; the Holy Roman Empire went to his brother Ferdinand I, while Spain, its overseas territories and the Spanish Netherlands

The Spanish Netherlands (; ; ; ) (historically in Spanish: , the name "Flanders" was used as a '' pars pro toto'') was the Habsburg Netherlands ruled by the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs from 1556 to 1714. They were a collection of States of t ...

were assigned to Philip. Over the next century, Naples and Lombardy became a major source of men and money for the Spanish Army of Flanders during the 1568 to 1648 Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish Empire, Spanish government. The Origins of the Eighty Years' War, causes of the w ...

.

England entered the war in June 1557 and the focus shifted to Flanders, where a Spanish army defeated the French at St. Quentin on 10 August. Despite this, in January 1558 the French took Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a French port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Calais is the largest city in Pas-de-Calais. The population of the city proper is 67,544; that of the urban area is 144,6 ...

; held by the English since 1347, its loss severely diminished their future ability to intervene directly in mainland Europe. They also captured Thionville

Thionville (; ; ) is a city in the northeastern French Departments of France, department of Moselle (department), Moselle. The city is located on the left bank of the river Moselle (river), Moselle, opposite its suburb Yutz.

History

Thionvi ...

in June but peace negotiations had already begun, with Henry absorbed by the internal conflict that led to the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion were a series of civil wars between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants (called Huguenots) from 1562 to 1598. Between two and four million people died from violence, famine or disease di ...

in 1562. The Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis on 3 April 1559 brought the Italian wars to an end. Corsica was returned to Genoa, while Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy, re-established the Savoyard state

The Savoyard state comprised the states ruled by the counts and dukes of Savoy from the Middle Ages to the formation of the Kingdom of Italy. Although it was an example of composite monarchy, it is a term applied to the polity by historians an ...

in northern Italy as an independent entity. France retained Calais and the Three Bishoprics, while other provisions essentially returned the position to that prevailing in 1551. Finally, Henry II and Philip II agreed to ask Pope Pius IV

Pope Pius IV (; 31 March 1499 – 9 December 1565), born Giovanni Angelo Medici, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 December 1559 to his death, in December 1565. Born in Milan, his family considered itself a b ...

to recognise Ferdinand as Emperor, and reconvene the Council of Trent

The Council of Trent (), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation at the time, it has been described as the "most ...

.

Aftermath

Results

The European balance of power changed significantly during the Italian Wars. The affirmation of French power in Italy around 1494 brought Austria and Spain to join an anti-French league that formed the "Habsburg ring" around France (Low Countries, Aragon, Castile, Empire) via dynastic marriages that eventually led to the large inheritance of Charles V. On the other hand, the last Italian war ended with the division of the Habsburg empire between the Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs following the abdication of Charles V. Philip II of Spain was heir of the kingdoms held by Charles V in Spain, southern Italy, and South America. Ferdinand I was the successor of Charles V in the Holy Roman Empire extending from Germany to northern Italy and became ''suo jure

''Suo jure'' is a Latin phrase, used in English to mean 'in his own right' or 'in her own right'. In most nobility-related contexts, it means 'in her own right', since in those situations the phrase is normally used of women; in practice, especi ...

'' king of the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

. The Habsburg Netherlands

Habsburg Netherlands were the parts of the Low Countries that were ruled by sovereigns of the Holy Roman Empire's House of Habsburg. This rule began in 1482 and ended for the Northern Netherlands in 1581 and for the Southern Netherlands in 1797. ...

and the Duchy of Milan were left in personal union

A personal union is a combination of two or more monarchical states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, involves the constituent states being to some extent in ...

to the king of Spain while continuing to be part of the Holy Roman Empire.

The division of the Empire of Charles V, along with the capture of the Pale of Calais

The Pale of Calais was a territory in northern France ruled by the monarchs of England from 1347 to 1558. The area, which centred on Calais, was taken following the Battle of Crécy in 1346 and the subsequent Siege of Calais (1346–47), Siege o ...

and the Three Bishoprics

The Three Bishoprics ( ) constituted a Provinces of France, government of the Kingdom of France consisting of the dioceses of Prince-Bishopric of Metz, Metz, Prince-Bishopric of Verdun, Verdun, and Prince-Bishopric of Toul, Toul within the Lorr ...

, was a positive result for France. However, the Habsburgs had gained a position of primacy in Italy at the expense of the French Valois. In return, France was forced to end opposition to Habsburg power and abandon its claims in Italy. Henry II also restored the Savoyard state

The Savoyard state comprised the states ruled by the counts and dukes of Savoy from the Middle Ages to the formation of the Kingdom of Italy. Although it was an example of composite monarchy, it is a term applied to the polity by historians an ...

to Emmanuel Philibert, who settled in Piedmont, and Corsica to the Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( ; ; ) was a medieval and early modern Maritime republics, maritime republic from the years 1099 to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italy, Italian coast. During the Late Middle Ages, it was a major commercial power in ...

. For this reason, the conclusion of the Italian Wars for France is considered to be a mixed result.

At the end of the wars, about half of Italy was ruled by the Spanish Habsburgs, including all of the south (Naples, Sicily, Sardinia) and the Duchy of Milan; the other half of Italy remained independent (although the north was largely formed by formal fiefs of the Austrian Habsburgs as part of the Holy Roman Empire). The most significant Italian power left was the papacy in central Italy

Central Italy ( or ) is one of the five official statistical regions of Italy used by the National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), a first-level NUTS region with code ITI, and a European Parliament constituency. It has 11,704,312 inhabita ...

, as it maintained major cultural

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

and political influence during the Catholic Reformation. The Council of Trent, suspended during the war, was reconvened by the terms of the peace treaties and came to an end in 1563.

Interpretations

As in the case of France, the Habsburg result is also variously interpreted. Many historians in the 20th century, includingGarrett Mattingly

Garrett Mattingly (May 6, 1900 – December 18, 1962) was a professor of European history at Columbia University who specialized in early modern diplomatic history. In 1960 he won a Pulitzer Prize for ''The Defeat of the Spanish Armada''.

Early l ...

, Eric Cochrane and Manuel F. Alvarez, identified the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis as the beginning of a Spanish hegemony in Italy. However, this view has been contested and abandoned in 21st-century historiography. Christine Shaw, Micheal J. Levin, and William Reger reject the concept of a Spanish hegemony on the ground that too many limits prevented Spain's dominance in the peninsula, and maintain that other powers also held major influence in Italy after 1559. Although Spain gained control of about half of the Italian states, the other half remained independent; among them, the Papacy in particular emerged strengthened by the conclusion of the Council of Trent according to the scholars Antelantonio Spagnoletti and Benedetto Croce. Furthermore, according to the historians Christine Shaw and Salvatore Puglisi, the Holy Roman Empire continued to play a role in Italian politics. Peter J. Wilson writes that three overlapping and competing feudal networks, Imperial, Spanish, and Papal, were affirmed in Italy as a result of the end of the wars.

In the long-term, Habsburg primacy in Italy continued to exist, but it varied significantly due to the change of dynasties in Austria and Spain. Following the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict fought between 1701 and 1714. The immediate cause was the death of the childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700, which led to a struggle for control of the Spanish E ...

and other wars of succession, the Habsburg-Lorraine of Austria largely replaced Spain and gained direct or indirect control of the fiefs of Imperial Italy, whereas the south eventually passed to an independent branch of the Spanish Bourbons. France would return in Italy to confront Habsburg power, first under Louis XIV, and later under Napoleon, but only the unification of Italy would permanently remove foreign powers from the peninsula.

Charles Tilly

Charles Tilly (May 27, 1929 – April 29, 2008) was an American sociologist, political scientist, and historian who wrote on the relationship between politics and society. He was a professor of history, sociology, and social science at the Uni ...

has characterized the Italian Wars as a key part in his theory of state formation, as the wars demonstrated the value of large armies and superior military technology. In ''Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990–1992'', Tilly argues that a "comprehensive European state system" can be reasonably dated to the Italian Wars.

Military