Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

has been inhabited by humans

since the Paleolithic. During antiquity, there were many

peoples

The term "the people" refers to the public or common mass of people of a polity. As such it is a concept of human rights law, international law as well as constitutional law, particularly used for claims of popular sovereignty. In contrast, a ...

in the Italian peninsula, including

Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization ( ) was an ancient civilization created by the Etruscans, a people who inhabited Etruria in List of ancient peoples of Italy, ancient Italy, with a common language and culture, and formed a federation of city-states. Af ...

,

Latins

The term Latins has been used throughout history to refer to various peoples, ethnicities and religious groups using Latin or the Latin-derived Romance languages, as part of the legacy of the Roman Empire. In the Ancient World, it referred to th ...

,

Samnites

The Samnites () were an ancient Italic peoples, Italic people who lived in Samnium, which is located in modern inland Abruzzo, Molise, and Campania in south-central Italy.

An Oscan language, Oscan-speaking Osci, people, who originated as an offsh ...

,

Umbri

The Umbri were an Italic peoples, Italic people of ancient Italy. A region called Umbria still exists and is now occupied by Italian speakers. It is somewhat smaller than the Regio VI Umbria, ancient Umbria.

Most ancient Umbrian cities were sett ...

,

Cisalpine Gaul

Cisalpine Gaul (, also called ''Gallia Citerior'' or ''Gallia Togata'') was the name given, especially during the 4th and 3rd centuries BC, to a region of land inhabited by Celts (Gauls), corresponding to what is now most of northern Italy.

Afte ...

s, Greeks in ''

Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia refers to the Greek-speaking areas of southern Italy, encompassing the modern Regions of Italy, Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania, and Sicily. These regions were Greek colonisation, extensively settled by G ...

'' and others. Most significantly, Italy was the cradle of the

Roman civilization

The history of Rome includes the history of the Rome, city of Rome as well as the Ancient Rome, civilisation of ancient Rome. Roman history has been influential on the modern world, especially in the history of the Catholic Church, and Roman la ...

.

Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

was founded as a kingdom in 753 BC and became a republic in 509 BC. The

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

then

unified Italy forming a confederation of the Italic peoples and

rose

A rose is either a woody perennial plant, perennial flowering plant of the genus ''Rosa'' (), in the family Rosaceae (), or the flower it bears. There are over three hundred Rose species, species and Garden roses, tens of thousands of cultivar ...

to dominate Western Europe, Northern Africa, and the Near East. After the

assassination of Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar, the Roman dictator, was assassinated on the Ides of March (15 March) 44 BC by a group of senators during a Roman Senate, Senate session at the Curia of Pompey, located within the Theatre of Pompey in Ancient Rome, Rome. The ...

, the Roman Empire dominated Western Europe and the Mediterranean for centuries, contributing to the development of Western culture, philosophy, science and art.

During the

early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages (historiography), Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th to the 10th century. They marked the start o ...

, Italy experienced the succession in power of

Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths () were a Roman-era Germanic peoples, Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Goths, Gothic kingdoms within the Western Roman Empire, drawing upon the large Gothic populatio ...

,

Byzantines,

Longobards

The Lombards () or Longobards () were a Germanic people who conquered most of the Italian Peninsula between 568 and 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the '' History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 and 796) t ...

and the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

and fragmented into numerous

city-states

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world throughout history, including cities such as Rome, ...

and regional polities, a situation that would remain until the unification of the country. These polities and the

maritime republics

The maritime republics (), also called merchant republics (), were Italian Thalassocracy , thalassocratic Port city, port cities which, starting from the Middle Ages, enjoyed political autonomy and economic prosperity brought about by their mar ...

, in particular

Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

and

Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, rose to prosperity. Eventually, the

Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( ) was a period in History of Italy, Italian history between the 14th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Western Europe and marked t ...

emerged and spread to the rest of Europe, bringing a renewed interest in

humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and Agency (philosophy), agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The me ...

,

science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

,

exploration

Exploration is the process of exploring, an activity which has some Expectation (epistemic), expectation of Discovery (observation), discovery. Organised exploration is largely a human activity, but exploratory activity is common to most organis ...

, and

art

Art is a diverse range of cultural activity centered around ''works'' utilizing creative or imaginative talents, which are expected to evoke a worthwhile experience, generally through an expression of emotional power, conceptual ideas, tec ...

with the start of the

modern era

The modern era or the modern period is considered the current historical period of human history. It was originally applied to the history of Europe and Western history for events that came after the Middle Ages, often from around the year 1500 ...

. In the medieval and

early modern era

The early modern period is a historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There is no exact date ...

,

Southern Italy

Southern Italy (, , or , ; ; ), also known as () or (; ; ; ), is a macroregion of Italy consisting of its southern Regions of Italy, regions.

The term "" today mostly refers to the regions that are associated with the people, lands or cultu ...

was ruled by the

Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 9th and 10th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norma ...

,

Angevin,

Aragonese,

French

French may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France

** French people, a nation and ethnic group

** French cuisine, cooking traditions and practices

Arts and media

* The French (band), ...

and

Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

crowns.

Central Italy

Central Italy ( or ) is one of the five official statistical regions of Italy used by the National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), a first-level NUTS region with code ITI, and a European Parliament constituency. It has 11,704,312 inhabita ...

was largely part of the

Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

.

In the 19th century,

Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the annexation of various states of the Italian peninsula and its outlying isles to the Kingdom of ...

led to the establishment of an Italian nation-state under the

House of Savoy

The House of Savoy (, ) is a royal house (formally a dynasty) of Franco-Italian origin that was established in 1003 in the historical region of Savoy, which was originally part of the Kingdom of Burgundy and now lies mostly within southeastern F ...

. The new

Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

quickly modernized and built

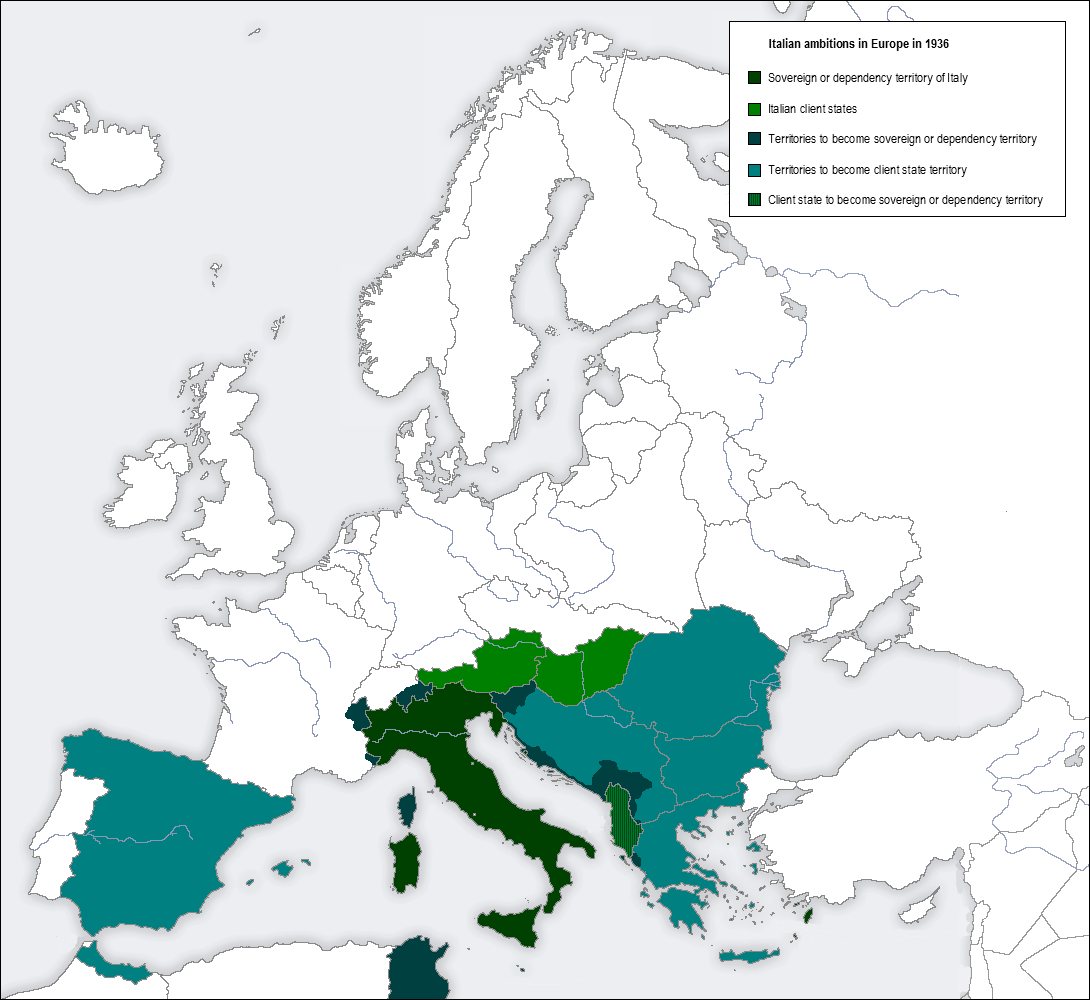

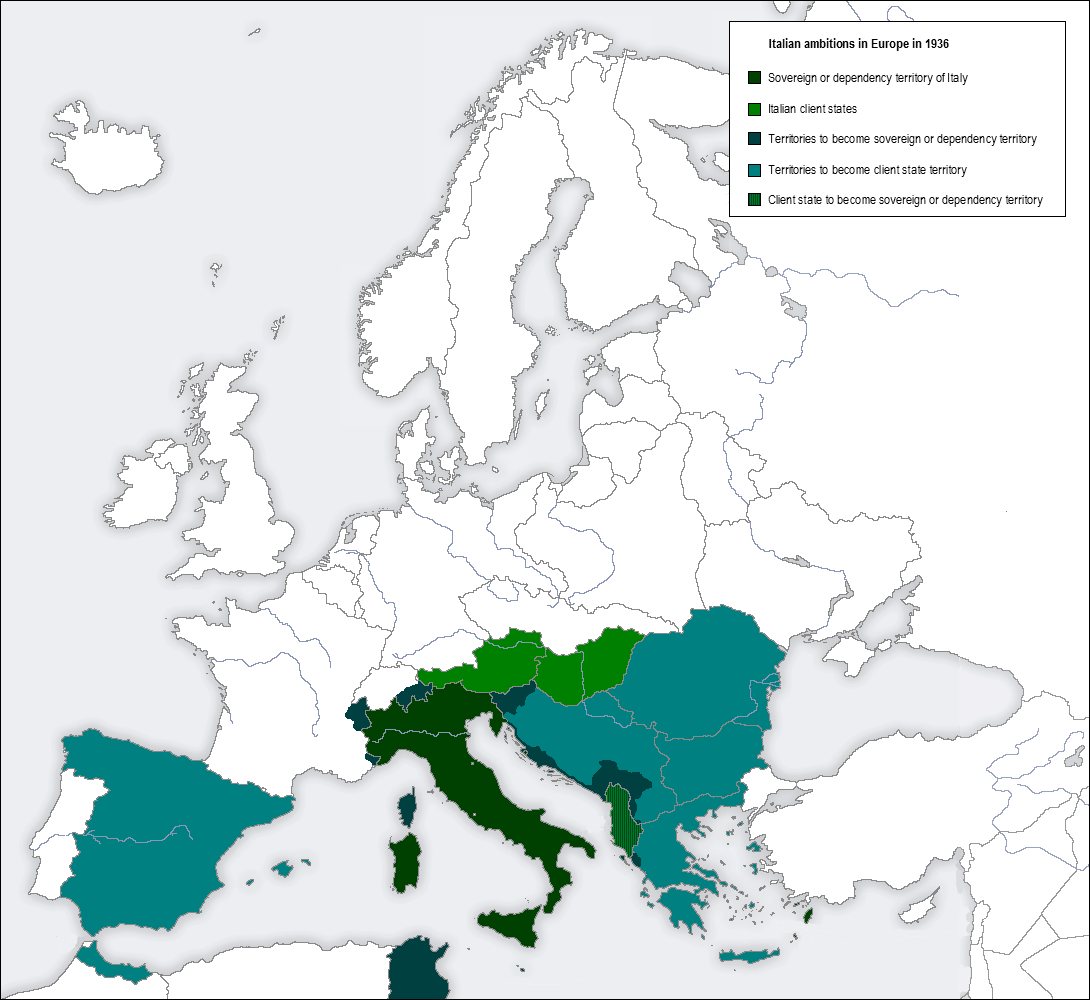

a colonial empire, controlling parts of Africa and countries along the Mediterranean. At the same time, Southern Italy remained rural and poor, originating the

Italian diaspora

The Italian diaspora (, ) is the large-scale emigration of Italians from Italy.

There were two major Italian diasporas in Italian history. The first diaspora began around 1880, two decades after the Risorgimento, Unification of Italy, and ended ...

. Victorious in

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Italy completed the unification by acquiring

Trento

Trento ( or ; Ladin language, Ladin and ; ; ; ; ; ), also known in English as Trent, is a city on the Adige, Adige River in Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol in Italy. It is the capital of the Trentino, autonomous province of Trento. In the 16th ...

and

Trieste

Trieste ( , ; ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital and largest city of the Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, as well as of the Province of Trieste, ...

and gained a permanent seat in the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

's executive council. The partial infringement of the

Treaty of London (1915)

The Treaty of London (; ) or the Pact of London (, ) was a secret agreement concluded on 26 April 1915 by the United Kingdom, France, and Russia on the one part, and Italy on the other, in order to entice the last to enter the Great War on ...

led to the sentiment of a ''

mutilated victory

Mutilated victory () is a term coined by Gabriele D'Annunzio at the end of World War I, used by a part of Italian nationalists to denounce the partial infringement (and request the full application) of the 1915 pact of London concerning territori ...

'' among radical nationalists, contributing to the rise of the

fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

dictatorship of

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

in 1922. During

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Italy was part of the

Axis powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

until the Italian surrender to

Allied powers and its occupation by

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

with

Fascist collaborators and then a co-belligerent of the

Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

during the

Italian resistance

The Italian Resistance ( ), or simply ''La'' , consisted of all the Italy, Italian Resistance during World War II, resistance groups who fought the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationists of the Italian Social Republic ...

and

liberation of Italy.

Following the end of the German occupation and the killing of Benito Mussolini, the

1946 Italian institutional referendum

An institutional referendum (, or ) was held by universal suffrage in the Kingdom of Italy on 2 June 1946, a key event of contemporary Italian history. Until 1946, Italy was a kingdom ruled by the House of Savoy, reigning since the unification ...

abolished the monarchy and became a republic, reinstated democracy, enjoyed an

economic boom

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with ...

, and co-founded the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

(

Treaty of Rome

The Treaty of Rome, or EEC Treaty (officially the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community), brought about the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the best known of the European Communities (EC). The treaty was signe ...

),

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

, the

Group of Six (later

G7), and the

G20

The G20 or Group of 20 is an intergovernmental forum comprising 19 sovereign countries, the European Union (EU), and the African Union (AU). It works to address major issues related to the global economy, such as international financial stabil ...

.

Prehistory

The arrival of the first

hominins

The Hominini (hominins) form a taxonomic tribe of the subfamily Homininae (hominines). They comprise two extant genera: ''Homo'' (humans) and '' Pan'' (chimpanzees and bonobos), and in standard usage exclude the genus ''Gorilla'' (gorillas), ...

was 850,000 years ago at

Monte Poggiolo

Monte Poggiolo is a hill near Forlì, Italy in the Emilia-Romagna area that is the site of a Florentine castle. The hill overlooks the Montone River valley from an elevation

of . An archaeological site containing Paleolithic artifacts is situa ...

.

[National Geographic Italia – Erano padani i primi abitanti d'Italia](_blank)

The presence of the ''

Homo neanderthalensis

Neanderthals ( ; ''Homo neanderthalensis'' or sometimes ''H. sapiens neanderthalensis'') are an extinct group of archaic humans who inhabited Europe and Western and Central Asia during the Middle to Late Pleistocene. Neanderthal extinctio ...

'' has been demonstrated in archaeological findings near Rome and

Verona

Verona ( ; ; or ) is a city on the Adige, River Adige in Veneto, Italy, with 255,131 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region, and is the largest city Comune, municipality in the region and in Northeast Italy, nor ...

dating to years ago (late

Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

).

Homo sapiens sapiens

Human taxonomy is the classification of the human species within zoological taxonomy. The systematic genus, ''Homo'', is designed to include both anatomically modern humans and extinct varieties of archaic humans. Current humans are classified ...

appeared during the upper

Palaeolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic ( years ago) ( ), also called the Old Stone Age (), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone tools, and which represents almost the entire period of human prehist ...

. Remains of the later prehistoric age include

Ötzi the Iceman

Ötzi, also called The Iceman, is the natural mummy of a man who lived between 3350 and 3105 BC. Ötzi's remains were discovered on 19 September 1991, in the Ötztal Alps (hence the nickname "Ötzi", ) at the Austria–Italy border. He ...

, dating to BC (

Copper Age

The Chalcolithic ( ) (also called the Copper Age and Eneolithic) was an archaeological period characterized by the increasing use of smelted copper. It followed the Neolithic and preceded the Bronze Age. It occurred at different periods in dif ...

).

During the Copper Age, Indoeuropean people migrated to Italy in four waves. A first Indoeuropean migration occurred around the mid-3rd millennium BC, from a population who imported

coppersmithing

A coppersmith, also known as a brazier, is a person who makes artifacts from copper and brass. Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc. The term "redsmith" is used for a tinsmith that uses tinsmithing tools and techniques to make copper items.

Hi ...

. The

Remedello culture

The Remedello culture (Italian ''Cultura di Remedello'') developed during the Copper Age (4th and 3rd millennium BCE) in Northern Italy, particularly in the area of the Po valley. The name comes from the town of Remedello (Brescia) where several ...

took over the

Po Valley

The Po Valley, Po Plain, Plain of the Po, or Padan Plain (, , or ) is a major geographical feature of northern Italy. It extends approximately in an east-west direction, with an area of including its Venetian Plain, Venetic extension not actu ...

. The second wave occurred in the

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

, from the late 3rd to the early 2nd millennium BC, with tribes identified with the

Beaker culture

The Bell Beaker culture, also known as the Bell Beaker complex or Bell Beaker phenomenon, is an archaeological culture named after the inverted-bell Beaker (archaeology), beaker drinking vessel used at the beginning of the European Bronze Age, ...

and by the use of

bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals (such as phosphorus) or metalloid ...

smithing

A metalsmith or simply smith is a craftsperson fashioning useful items (for example, tools, kitchenware, tableware, jewelry, armor and weapons) out of various metals. Smithing is one of the oldest metalworking occupations. Shaping metal with a ...

, in the

Padan Plain

The Po Valley, Po Plain, Plain of the Po, or Padan Plain (, , or ) is a major geographical feature of northern Italy. It extends approximately in an east-west direction, with an area of including its Venetian Plain, Venetic extension not actu ...

, in

Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of 3,660,834 inhabitants as of 2025. The capital city is Florence.

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, artistic legacy, and its in ...

and on the coasts of

Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

and

Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

. In the mid-2nd millennium BC, a third wave arrived, associated with the

Apenninian civilization and the

Terramare culture

Terramare, terramara, or terremare is a technology complex mainly of the central Po valley, in Emilia, Northern Italy, dating to the Middle and Late Bronze Age c. 1700–1150 BC. It takes its name from the "black earth" residue of settlement m ...

.

The Terramare people were hunters, but had domesticated animals and cultivated crops; they were fairly skilful metallurgists, casting bronze in moulds.

In the late Bronze Age, from the late 2nd millennium to the early 1st millennium BC, a fourth wave, the

Proto-Villanovan culture

The Proto-Villanovan culture was a late Bronze Age culture that appeared in Italy in the first half of the 12th century BC and lasted until the 10th century BC, part of the central European Urnfield culture system (1300–750 BCE).

History

T ...

, brought iron-working to the Italian peninsula. Proto-Villanovan culture may have been part of the central European

Urnfield culture

The Urnfield culture () was a late Bronze Age Europe, Bronze Age culture of Central Europe, often divided into several local cultures within a broader Urnfield tradition. The name comes from the custom of cremation, cremating the dead and placin ...

system,

or a derivation from Terramare culture. Various authors, such as

Marija Gimbutas

Marija Gimbutas (, ; January 23, 1921 – February 2, 1994) was a Lithuanian archaeology, archaeologist and anthropologist known for her research into the Neolithic and Bronze Age cultures of "Old European Culture, Old Europe" and for her Kurgan ...

, associated this culture with the spread of the proto-

Italics

In typography, italic type is a cursive font based on a stylised form of calligraphic handwriting. Along with blackletter and roman type, it served as one of the major typefaces in the history of Western typography.

Owing to the influence f ...

into the

Italian Peninsula.

Nuragic civilization

Born in

Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

and

southern Corsica

Corse-du-Sud (; , or ; ) is (as of 2019) an administrative department of France, consisting of the southern part of the island of Corsica. The corresponding departmental territorial collectivity merged with that of Haute-Corse on 1 January ...

(where it is called

Torrean civilization

The Torrean civilization was a Bronze Age megalithic civilization that developed in Southern Corsica, mostly concentrated south of Ajaccio, during the second half of the second millennium BC.

History

The characteristic buildings of this cultur ...

), the

Nuraghe

The nuraghe, or nurhag, is the main type of ancient megalithic Building, edifice found in Sardinia, Italy, developed during the History of Sardinia#Nuragic period, Nuragic Age between 1900 and 730 BC. Today it has come to be the symbol of ...

civilization lasted from the 18th century BC to the 2nd century AD.

They take their name from the characteristic Nuragic towers, which evolved from the pre-existing megalithic culture, which built

dolmen

A dolmen, () or portal tomb, is a type of single-chamber Megalith#Tombs, megalithic tomb, usually consisting of two or more upright megaliths supporting a large flat horizontal capstone or "table". Most date from the Late Neolithic period (4000 ...

s and

menhir

A menhir (; from Brittonic languages: ''maen'' or ''men'', "stone" and ''hir'' or ''hîr'', "long"), standing stone, orthostat, or lith is a large upright stone, emplaced in the ground by humans, typically dating from the European middle Br ...

s. Today more than 7,000 nuraghes appear in Sardinia.

No written records of this civilization have been discovered, apart from a few possible short epigraphic documents.

The only written information comes from classical literature of the

Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

and

Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

, and may be considered more mythological than historical. The language (or languages) spoken in Sardinia during the Bronze Age is (are) unknown since there are no written records from the period, although research suggests that around the 8th century BC the Nuragic populations may have adopted an alphabet similar to that used in

Euboea

Euboea ( ; , ), also known by its modern spelling Evia ( ; , ), is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete, and the sixth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by ...

.

Iron Age

Etruscan civilization

The

Etruscan civilization

The Etruscan civilization ( ) was an ancient civilization created by the Etruscans, a people who inhabited Etruria in List of ancient peoples of Italy, ancient Italy, with a common language and culture, and formed a federation of city-states. Af ...

flourished in central Italy after 800 BC. The main hypotheses on the origins of the

Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization ( ) was an ancient civilization created by the Etruscans, a people who inhabited Etruria in List of ancient peoples of Italy, ancient Italy, with a common language and culture, and formed a federation of city-states. Af ...

are that they are indigenous,

probably stemming from the

Villanovan culture

The Villanovan culture (–700 BCE), regarded as the earliest phase of the Etruscan civilization, was the earliest Iron Age culture of Italy. It directly followed the Bronze Age Proto-Villanovan culture which branched off from the Urnfield cult ...

, or that they are the result of invasion from the north or the

Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

. A 2007 study has suggested a

Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

ern origin. The researchers conclude that their data, taken from the modern Tuscan population, "support the scenario of a post-Neolithic genetic input from the Near East to the present-day population of Tuscany". In the absence of any dating evidence, there is however no direct link between this genetic input and the Etruscans. By contrast, a

mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondrion, mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the D ...

study of 2013 has suggested that the Etruscans were probably an indigenous population. Among ancient populations, ancient Etruscans are found to be closest to a Neolithic population from Central Europe.

It is widely accepted that Etruscans spoke a non-

Indo-European language

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the northern Indian subcontinent, most of Europe, and the Iranian plateau with additional native branches found in regions such as Sri Lanka, the Maldives, parts of Central Asia ( ...

. Some inscriptions in a similar language, known as

Lemnian

The Lemnian language was spoken on the island of Lemnos, Greece, in the second half of the 6th century BC. It is mainly attested by an inscription found on a funerary stele, termed the Lemnos stele, discovered in 1885 near Kaminia. Fragments of ...

, have been found on the Aegean island of

Lemnos

Lemnos ( ) or Limnos ( ) is a Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within the Lemnos (regional unit), Lemnos regional unit, which is part of the North Aegean modern regions of Greece ...

. Etruscans were a monogamous society that emphasized pairing. The historical Etruscans had achieved a form of state with remnants of chiefdom and tribal forms. The first attestations of an

Etruscan religion

Etruscan religion comprises a set of stories, beliefs, and religious practices of the Etruscan civilization, heavily influenced by the mythology of ancient Greece, and sharing similarities with concurrent Roman mythology and Religion in ancie ...

can be traced to the

Villanovan culture

The Villanovan culture (–700 BCE), regarded as the earliest phase of the Etruscan civilization, was the earliest Iron Age culture of Italy. It directly followed the Bronze Age Proto-Villanovan culture which branched off from the Urnfield cult ...

.

Etruscan expansion was focused across the

Apennines

The Apennines or Apennine Mountains ( ; or Ἀπέννινον ὄρος; or – a singular with plural meaning; )Latin ''Apenninus'' (Greek or ) has the form of an adjective, which would be segmented ''Apenn-inus'', often used with nouns s ...

. The political structure of the Etruscan culture was similar, albeit more aristocratic, to Magna Graecia in the south. The mining and commerce of metal, especially copper and iron, led to an enrichment of the Etruscans and to the expansion of their influence in the Italian peninsula and the western

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

. Here their interests collided with those of the Greeks, especially in the 6th century BC, when

Phoceans of Italy founded colonies along the coast of France, Catalonia and

Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

. This led the Etruscans to ally themselves with the

Carthaginians

The Punic people, usually known as the Carthaginians (and sometimes as Western Phoenicians), were a Semitic people, Semitic people who Phoenician settlement of North Africa, migrated from Phoenicia to the Western Mediterranean during the Iron ...

.

Around 540 BC, the

Battle of Alalia

The naval Battle of Alalia took place between 540 BC and 535 BC off the coast of Corsica between Greeks and the allied Etruscans and Carthaginians. A Greek force of 60 Phocaean ships defeated a Punic-Etruscan fleet of 120 ships while emigrating ...

led to a new distribution of power in the western Mediterranean.

Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

expanded its sphere of influence at the expense of the Greeks, and

Etruria

Etruria ( ) was a region of Central Italy delimited by the rivers Arno and Tiber, an area that covered what is now most of Tuscany, northern Lazio, and north-western Umbria. It was inhabited by the Etruscans, an ancient civilization that f ...

saw itself relegated to Corsica. From the first half of the 5th century, the new international political situation meant the beginning of the Etruscan decline. In 480 BC, Etruria's ally Carthage was defeated by a coalition of Magna Graecia cities led by

Syracuse

Syracuse most commonly refers to:

* Syracuse, Sicily, Italy; in the province of Syracuse

* Syracuse, New York, USA; in the Syracuse metropolitan area

Syracuse may also refer to:

Places

* Syracuse railway station (disambiguation)

Italy

* Provi ...

.

A few years later, in 474 BC, Syracuse's tyrant

Hiero

Hiero or hieron (; , "holy place" or "sacred place") is an ancient Greek shrine, Ancient Greek temple, temple, or temenos, temple precinct.

Hiero may also refer to:

People

* Hiero I of Syracuse, tyrant of Syracuse, Sicily from 478 to 467 BC

* ...

defeated the Etruscans at the

Battle of Cumae

The Battle of Cumae is the name given to at least two battles between Cumae and the Etruscans:

* In 524 BC an invading army of Umbrians, Daunians, Etruscans, and others were defeated by the Greeks of Cumae.

* The naval battle in 474 BC was be ...

. Etruria's influence over the cities of

Latium

Latium ( , ; ) is the region of central western Italy in which the city of Rome was founded and grew to be the capital city of the Roman Empire.

Definition

Latium was originally a small triangle of fertile, volcanic soil (Old Latium) on whic ...

and Campania weakened, and it was taken over by Romans and

Samnites

The Samnites () were an ancient Italic peoples, Italic people who lived in Samnium, which is located in modern inland Abruzzo, Molise, and Campania in south-central Italy.

An Oscan language, Oscan-speaking Osci, people, who originated as an offsh ...

. In the 4th century, Etruria saw a

Gallic invasion end its influence over the

Po valley and the

Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

coast. Meanwhile,

Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

had started annexing Etruscan cities. This led to the loss of their north provinces.

Etruscia was assimilated by Rome around 500 BC.

Italic peoples

The Italic peoples were an

ethnolinguistic group

An ethnolinguistic group (or ethno-linguistic group) is a group that is unified by both a common ethnicity and language. Most ethnic groups share a first language. However, "ethnolinguistic" is often used to emphasise that language is a major bas ...

identified by use of

Italic languages

The Italic languages form a branch of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family, whose earliest known members were spoken on the Italian Peninsula in the first millennium BC. The most important of the ancient Italic languages ...

. Among the Italic peoples in the Italian peninsula were the

Osci

The Osci (also called Oscans, Opici, Opsci, Obsci, Opicans) were an Italic people of Campania and Latium adiectum before and during Roman times. They spoke the Oscan language, also spoken by the Samnites of Southern Italy. Although the langua ...

, the

Veneti, the

Samnites

The Samnites () were an ancient Italic peoples, Italic people who lived in Samnium, which is located in modern inland Abruzzo, Molise, and Campania in south-central Italy.

An Oscan language, Oscan-speaking Osci, people, who originated as an offsh ...

, the

Latins

The term Latins has been used throughout history to refer to various peoples, ethnicities and religious groups using Latin or the Latin-derived Romance languages, as part of the legacy of the Roman Empire. In the Ancient World, it referred to th ...

and the

Umbri

The Umbri were an Italic peoples, Italic people of ancient Italy. A region called Umbria still exists and is now occupied by Italian speakers. It is somewhat smaller than the Regio VI Umbria, ancient Umbria.

Most ancient Umbrian cities were sett ...

.

In the region south of the

Tiber

The Tiber ( ; ; ) is the List of rivers of Italy, third-longest river in Italy and the longest in Central Italy, rising in the Apennine Mountains in Emilia-Romagna and flowing through Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, where it is joined by the R ...

(''Latium Vetus''), the

Latial culture

The Latial culture ranged approximately over ancient Old Latium. The Iron Age Latial culture is associated with the processes of formation of the Latins, the culture was likely therefore to identify a phase of the socio-political self-consciousne ...

of the

Latins

The term Latins has been used throughout history to refer to various peoples, ethnicities and religious groups using Latin or the Latin-derived Romance languages, as part of the legacy of the Roman Empire. In the Ancient World, it referred to th ...

emerged, while in the north-east of the peninsula the

Este culture

The Este culture or Atestine culture was an archaeological culture existing from the late Italian Bronze Age (10th–9th century BC, proto-venetic phase) to the Iron Age and Roman period (1st century BC). It was located in the modern area of Ve ...

of the

Veneti appeared. Roughly in the same period, from their core area in central Italy (modern-day

Umbria

Umbria ( ; ) is a Regions of Italy, region of central Italy. It includes Lake Trasimeno and Cascata delle Marmore, Marmore Falls, and is crossed by the Tiber. It is the only landlocked region on the Italian Peninsula, Apennine Peninsula. The re ...

and

Sabina), the

Osco-

Umbri

The Umbri were an Italic peoples, Italic people of ancient Italy. A region called Umbria still exists and is now occupied by Italian speakers. It is somewhat smaller than the Regio VI Umbria, ancient Umbria.

Most ancient Umbrian cities were sett ...

ans began to emigrate in various waves, through the process of

Ver sacrum

''Ver sacrum'' ("sacred spring") is a religious practice of ancient Italic peoples, especially the Sabelli (or Sabini) and their offshoot Samnites, concerning the dedication of colonies. It was of special interest to Georges Dumézil, according ...

, the ritualized extension of colonies, in southern Latium,

Molise

Molise ( , ; ; , ) is a Regions of Italy, region in Southern Italy. Until 1963, it formed part of the region of Abruzzi e Molise together with Abruzzo. The split, which did not become effective until 1970, makes Molise the newest region in Ital ...

and the whole southern half of the peninsula, replacing the previous tribes, such as the

Opici The Opici were an ancient italic people of the Latino-Faliscan group who lived in the region of Campania. They settled in the area in the late Bronze Age but their territory was later conquered during the Iron Age by the Osci, another Italic people ...

and the

Oenotrians

The Oenotrians or Enotrians were an ancient Italic people who inhabited a territory in Southern Italy from Paestum to southern Calabria. By the sixth century BC, the Oenotrians had been absorbed into other Italic tribes.

Etymology

A likely deri ...

. This corresponds with the emergence of the Terni culture, which had strong similarities with the Celtic cultures of Hallstatt and

La Tène.

Before and during the period of the arrival of the Greek and Phoenician immigrants, Sicily was already inhabited by native Italics in three major groups: the

Elymians

The Elymians () were an ancient tribe, tribal people who inhabited the western part of Sicily during the Bronze Age and Classical antiquity.

Origins

According to Thucydides, the Elymians were refugees coming from the destroyed Troy. Instead for ...

in the west, the

Sicani

The Sicani or Sicanians were one of three ancient peoples of Sicily present at the time of Phoenician and Greek colonization. The Sicani dwelt east of the Elymians and west of the Sicels, having, according to Diodorus Siculus, the boundary with ...

in the centre, and the

Sicels

The Sicels ( ; or ''Siculī'') were an Indo-European tribe who inhabited eastern Sicily, their namesake, during the Iron Age. They spoke the Siculian language. After the defeat of the Sicels at the Battle of Nomae in 450 BC and the death of ...

(source of the name Sicily) in the east.

It is generally believed that around

2000 BC

The 20th century BC was a century that lasted from the year 2000 BC to 1901 BC.

The period of the 2nd Millennium BC

Events

* c. 2000 BC:

** Farmers and herding, herders traveled south from Ethiopia and settled in Kenya.

** Dawn of the Cap ...

, the

Ligures

The Ligures or Ligurians were an ancient people after whom Liguria, a region of present-day Northern Italy, north-western Italy, is named. Because of the strong Celts, Celtic influences on their language and culture, they were also known in anti ...

occupied a large area of the peninsula, including much of north-western Italy and all of northern Tuscany. Since many scholars consider the

language

Language is a structured system of communication that consists of grammar and vocabulary. It is the primary means by which humans convey meaning, both in spoken and signed language, signed forms, and may also be conveyed through writing syste ...

of this ancient population to be

Pre-Indo-European, they are often not classified as Italics.

By the mid-first millennium BCE, the Latins of

Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

were growing in power and influence. After the Latins had liberated themselves from Etruscan rule they acquired a dominant position among the Italic tribes. Frequent conflict between various Italic tribes followed; the best documented are the

Samnite Wars

The First, Second, and Third Samnite Wars (343–341 BC, 326–304 BC, and 298–290 BC) were fought between the Roman Republic and the Samnites, who lived on a stretch of the Apennine Mountains south of Rome and north of the Lucanian tribe.

...

.

The Latins eventually succeeded in unifying the Italic elements in the country. In the early first century BCE, several Italic tribes, in particular the

Marsi

The Marsi were an Italic people of ancient Italy, whose chief centre was Marruvium, on the eastern shore of Lake Fucinus (which was drained in the time of Claudius). The area in which they lived is now called Marsica. They originally spoke a l ...

and the Samnites, rebelled against Roman rule (the

Social War). After Roman victory was secured, all peoples in Italy, except for the

Celts

The Celts ( , see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples ( ) were a collection of Indo-European languages, Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient Indo-European people, reached the apoge ...

of the Po Valley, were granted

Roman citizenship

Citizenship in ancient Rome () was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, traditions, and cu ...

. In the subsequent centuries, Italic tribes adopted

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

language and culture in a process known as

Romanization

In linguistics, romanization is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Latin script, Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and tra ...

.

Magna Graecia

In the eighth and seventh centuries BC, for reasons including demographic crisis, the search for new commercial outlets and ports, and expulsion from their homeland, Greeks began to settle along the coast of Sicily and the southern part of the Italian peninsula, which became known as

Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia refers to the Greek-speaking areas of southern Italy, encompassing the modern Regions of Italy, Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania, and Sicily. These regions were Greek colonisation, extensively settled by G ...

.

Greek culture

The culture of Greece has evolved over thousands of years, beginning in Minoan and later in Mycenaean Greece, continuing most notably into Classical Greece, while influencing the Roman Empire and its successor the Byzantine Empire. Other cultu ...

was exported to Italy, in its dialects of the

Ancient Greek language

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

, its religious rites and its traditions of the independent ''

polis

Polis (: poleis) means 'city' in Ancient Greek. The ancient word ''polis'' had socio-political connotations not possessed by modern usage. For example, Modern Greek πόλη (polē) is located within a (''khôra''), "country", which is a πατ ...

''. An original

Hellenic civilization

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically rel ...

soon developed, later interacting with the native

Italic and

Latin civilisations. The most important cultural transplant was the

Chalcidean/

Cumaean variety of the

Greek alphabet

The Greek alphabet has been used to write the Greek language since the late 9th or early 8th century BC. It was derived from the earlier Phoenician alphabet, and is the earliest known alphabetic script to systematically write vowels as wel ...

, which was adopted by the

Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization ( ) was an ancient civilization created by the Etruscans, a people who inhabited Etruria in List of ancient peoples of Italy, ancient Italy, with a common language and culture, and formed a federation of city-states. Af ...

; the

Old Italic alphabet

The Old Italic scripts are a family of ancient writing systems used in the Italian Peninsula between about 700 and 100 BC, for various languages spoken in that time and place. The most notable member is the Etruscan alphabet, which was the i ...

subsequently evolved into the

Latin alphabet

The Latin alphabet, also known as the Roman alphabet, is the collection of letters originally used by the Ancient Rome, ancient Romans to write the Latin language. Largely unaltered except several letters splitting—i.e. from , and from � ...

.

Many of the new Hellenic cities became very rich and powerful, like ''Neapolis'' (

Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

), ''

Syracuse

Syracuse most commonly refers to:

* Syracuse, Sicily, Italy; in the province of Syracuse

* Syracuse, New York, USA; in the Syracuse metropolitan area

Syracuse may also refer to:

Places

* Syracuse railway station (disambiguation)

Italy

* Provi ...

'', ''

Acragas'', and ''

Sybaris

Sybaris (; ) was an important ancient Greek city situated on the coast of the Gulf of Taranto in modern Calabria, Italy.

The city was founded around 720 BC by Achaeans (tribe), Achaean and Troezenian settlers and the Achaeans also went on ...

''. Other cities in Magna Graecia included ''

Tarentum'', ''

Epizephyrian Locri'', ''

Rhegium

Reggio di Calabria (; ), commonly and officially referred to as Reggio Calabria, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, is the List of cities in Italy, largest city in Calabria as well as the seat of the Metropolitan City of Reggio Calabria. As ...

'', ''

Croton'', ''

Thurii

Thurii (; ; ), called also by some Latin writers Thūrium (compare , in Ptolemy), and later in Roman times also Cōpia and Cōpiae, was an ancient Greek city situated on the Gulf of Taranto, near or on the site of the great renowned city of Syb ...

'', ''

Elea'', ''

Nola

Nola is a town and a municipality in the Metropolitan City of Naples, Campania, southern Italy. It lies on the plain between Mount Vesuvius and the Apennines. It is traditionally credited as the diocese that introduced bells to Christian worship.

...

'', ''

Ancona

Ancona (, also ; ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region of central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona, homonymous province and of the region. The city is located northeast of Ro ...

'', ''

Syessa'', ''

Bari

Bari ( ; ; ; ) is the capital city of the Metropolitan City of Bari and of the Apulia Regions of Italy, region, on the Adriatic Sea in southern Italy. It is the first most important economic centre of mainland Southern Italy. It is a port and ...

'', and others.

After

Pyrrhus of Epirus

Pyrrhus ( ; ; 319/318–272 BC) was a Greeks, Greek king and wikt:statesman, statesman of the Hellenistic period.Plutarch. ''Parallel Lives'',Pyrrhus... He was king of the Molossians, of the royal Aeacidae, Aeacid house, and later he became ki ...

failed to stop the spread of Roman hegemony in 282 BC, the south fell under Roman domination. It was held by the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

after the

fall of Rome

The fall of the Western Roman Empire, also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome, was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vast ...

in

the West

West is a cardinal direction or compass point.

West or The West may also refer to:

Geography and locations

Global context

* The Western world

* Western culture and Western civilization in general

* The Western Bloc, countries allied with NAT ...

and even the

Lombards

The Lombards () or Longobards () were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who conquered most of the Italian Peninsula between 568 and 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written betwee ...

failed to consolidate it, though the centre of the south was theirs from

Zotto

Zotto (also Zotton or Zottone) was the military leader () of the Lombards in the Mezzogiorno. He is generally considered the founder of the Duchy of Benevento in 571 and its first duke : “''…Fuit autem primus Langobardorum dux in Benevento no ...

's conquest in the final quarter of the 6th century.

Roman period

Roman Kingdom

Little is certain about the history of the Roman Kingdom, as nearly no written records from that time survive, and the histories written during the

Republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

and

Empire

An empire is a political unit made up of several territories, military outpost (military), outposts, and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a hegemony, dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the ...

are largely based on legends. According to the

founding myth

An origin myth is a type of myth that explains the beginnings of a natural or social aspect of the world. Creation myths are a type of origin myth narrating the formation of the universe. However, numerous cultures have stories that take place a ...

of Rome, the city was

founded on 21 April 753 BC by twin brothers

Romulus and Remus

In Roman mythology, Romulus and (, ) are twins in mythology, twin brothers whose story tells of the events that led to the Founding of Rome, founding of the History of Rome, city of Rome and the Roman Kingdom by Romulus, following his frat ...

, who descended from the

Trojan

Trojan or Trojans may refer to:

* Of or from the ancient city of Troy

* Trojan language, the language of the historical Trojans

Arts and entertainment Music

* '' Les Troyens'' ('The Trojans'), an opera by Berlioz, premiered part 1863, part 18 ...

prince

Aeneas

In Greco-Roman mythology, Aeneas ( , ; from ) was a Troy, Trojan hero, the son of the Trojan prince Anchises and the Greek goddess Aphrodite (equivalent to the Roman Venus (mythology), Venus). His father was a first cousin of King Priam of Troy ...

and who were grandsons of

Numitor

In Roman mythology, King Numitor () of Alba Longa was the maternal grandfather of Rome's founder and first king, Romulus, and his twin brother Romulus and Remus, Remus. He was the son of Procas, descendant of Aeneas the Troy, Trojan, and father o ...

of

Alba Longa

Alba Longa (occasionally written Albalonga in Italian sources) was an ancient Latins (Italic tribe), Latin city in Central Italy in the vicinity of Lake Albano in the Alban Hills. The ancient Romans believed it to be the founder and head of the ...

.

Natale di Roma

Natale di Roma () is an annual festival held in Rome on April 21 to celebrate the legendary founding of the city.Plutarch, ''Parallel Lives - Life of Romulus''12.2(from LacusCurtius) According to legend, Romulus is said to have founded the city ...

(''Birthday of Rome'') is an annual festival held in

Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

on 21 April to celebrate the

founding of the city.

Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, ''Parallel Lives

*

Culture of ancient Greece

Culture of ancient Rome

Ancient Greek biographical works

Ethics literature

History books about ancient Rome

Cultural depictions of Gaius Marius

Cultural depictions of Mark Antony

Cultural depictions of Cicero

...

- Life of Romulus''

12.2

(from LacusCurtius

LacusCurtius is the ancient Graeco-Roman part of a large history website, hosted as of March 2025 on a server at the University of Chicago. Starting in 1995, as of January 2004 it gave "access to more than 594 photos, 559 drawings and engravings, ...

)

The traditional account of Roman history, which has come down through

Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding i ...

,

Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

,

Dionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius of Halicarnassus (,

; – after 7 BC) was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Emperor Augustus. His literary style was ''atticistic'' – imitating Classical Attic Greek in its prime.

...

, and others, is that in Rome's first centuries, it was ruled by a succession of seven kings. The

Gauls

The Gauls (; , ''Galátai'') were a group of Celts, Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age Europe, Iron Age and the Roman Gaul, Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). Th ...

destroyed much of Rome's historical records when they sacked the city after the

Battle of the Allia

The Battle of the Allia was fought between the Senones – a Gauls, Gallic tribe led by Brennus (leader of the Senones), Brennus, who had invaded Northern Italy – and the Roman Republic.

The battle was fought at the confluence of the Tibe ...

in 390 or 387 BC. With no contemporary records, all accounts of the kings must be carefully evaluated.

Roman Republic

According to tradition and later writers such as

Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding i ...

, the

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

was established around 509 BC, when the last of the seven kings of Rome,

Tarquin the Proud

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus (died 495 BC) was the legendary seventh and final king of Rome, reigning 25 years until the popular uprising that led to the establishment of the Roman Republic.Livy, '' ab urbe condita libri'', I He is commonly k ...

, was deposed by

Lucius Junius Brutus

Lucius Junius Brutus (died ) was the semi-legendary founder of the Roman Republic and traditionally one of its two first consuls. Depicted as responsible for the expulsion of his uncle, the Roman king Tarquinius Superbus after the suicide of L ...

. A system based on annually elected

magistrates

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a ''magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judici ...

and various representative assemblies was established. A

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

set a series of checks and balances, and a

separation of powers

The separation of powers principle functionally differentiates several types of state (polity), state power (usually Legislature#Legislation, law-making, adjudication, and Executive (government)#Function, execution) and requires these operat ...

. The most important magistrates were the two consuls, who together exercised executive authority as ''

imperium

In ancient Rome, ''imperium'' was a form of authority held by a citizen to control a military or governmental entity. It is distinct from '' auctoritas'' and '' potestas'', different and generally inferior types of power in the Roman Republic a ...

'', or military command. The consuls had to work with the

senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, which was initially an advisory council of the ranking nobility, or

patricians

The patricians (from ) were originally a group of ruling class families in ancient Rome. The distinction was highly significant in the Roman Kingdom and the early Republic, but its relevance waned after the Conflict of the Orders (494 BC to 287 B ...

, but grew in size and power.

In the 4th century BC, the Republic came under attack by the

Gauls

The Gauls (; , ''Galátai'') were a group of Celts, Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age Europe, Iron Age and the Roman Gaul, Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). Th ...

, who initially prevailed and sacked Rome. The Romans then drove the Gauls back, led by

Camillus. The Romans

gradually subdued the other peoples on the peninsula. The last threat to Roman

hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states, either regional or global.

In Ancient Greece (ca. 8th BC – AD 6th c.), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of ...

in Italy came when

Tarentum, a major

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

colony, enlisted the aid of

Pyrrhus of Epirus

Pyrrhus ( ; ; 319/318–272 BC) was a Greeks, Greek king and wikt:statesman, statesman of the Hellenistic period.Plutarch. ''Parallel Lives'',Pyrrhus... He was king of the Molossians, of the royal Aeacidae, Aeacid house, and later he became ki ...

in 281 BC, but this effort failed.

In the 3rd century BC, Rome had to face a new and formidable opponent:

Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

. In the three

Punic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of wars fought between the Roman Republic and the Ancient Carthage, Carthaginian Empire during the period 264 to 146BC. Three such wars took place, involving a total of forty-three years of warfare on both land and ...

, Carthage was eventually destroyed and Rome gained control over Hispania, Sicily and North Africa. After defeating the

Macedon

Macedonia ( ; , ), also called Macedon ( ), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, which later became the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by the royal ...

ian and

Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire ( ) was a Greek state in West Asia during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 312 BC by the Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator, following the division of the Macedonian Empire founded by Alexander the Great ...

s in the 2nd century BC, the Romans became the dominant people of the Mediterranean.

[Bagnall 1990] The conquest of the Hellenistic kingdoms provoked a fusion between Roman and Greek cultures and the Roman elite, once rural, became a luxurious and cosmopolitan one. By this time Rome was a consolidated empire – in the military view – and had no major enemies.

Roman armies occupied Spain in the early 2nd century BC but encountered stiff resistance. The

Celtiberian stronghold of

Numantia

Numantia () is an ancient Celtiberian settlement, whose remains are located on a hill known as Cerro de la Muela in the current municipality of Garray ( Soria), Spain.

Numantia is famous for its role in the Celtiberian Wars. In 153 BC, Num ...

became the centre of Spanish resistance in the 140s and 130s BC. Numantia fell and was razed to the ground in 133 BC. In 105 BC, the Celtiberians drove the

Cimbri

The Cimbri (, ; ) were an ancient tribe in Europe. Ancient authors described them variously as a Celtic, Gaulish, Germanic, or even Cimmerian people. Several ancient sources indicate that they lived in Jutland, which in some classical texts was ...

and

Teutones

The Teutons (, ; ) were an ancient northern European tribe mentioned by Roman authors. The Teutons are best known for their participation, together with the Cimbri and other groups, in the Cimbrian War with the Roman Republic in the late secon ...

from northern Spain, though these had

crushed Roman arms in southern Gaul, inflicting 80,000 casualties on the Roman army. The

conquest of Hispania

The romans ruled and occupied territories in the Iberian Peninsula that were previously under the control of native Celtic, Iberian, Celtiberian and Aquitanian tribes and the Carthaginian Empire. The Carthaginian territories in the south and ...

was completed in 19 BC—but at a heavy cost.

Towards the end of the 2nd century BC, a huge migration of

Germanic tribes took place, led by the Cimbri and the Teutones. These tribes overwhelmed the peoples with whom they came into contact and threatened Italy. At the

Battle of Aquae Sextiae

The Battle of Aquae Sextiae (Aix-en-Provence) took place in 102 BC. After a string of Roman defeats (see: the Battle of Noreia, the Battle of Burdigala, and the Battle of Arausio), the Romans under Gaius Marius finally defeated the Teutones ...

and the

Battle of Vercellae

The Battle of Vercellae or Battle of the Raudine Plain was fought on 30 July 101 BC on a plain near Vercellae in Gallia Cisalpina (modern-day Northern Italy). A Celto-Germanic confederation under the command of the Cimbric king Boiorix was de ...

the Germans were virtually annihilated. In these two battles the Teutones and

Ambrones

The Ambrones () were an ancient tribe mentioned by Roman authors. They are believed by some to have been a Germanic tribe from Jutland; the Romans were not clear about their exact origin.

In the late 2nd century BC, along with the fellow Cimbri ...

are said to have lost 290,000 men, and the Cimbri 220,000.

In the mid-1st century BC, the Republic faced a period of political crisis and social unrest.

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

reconciled the two more powerful men in Rome:

Marcus Licinius Crassus

Marcus Licinius Crassus (; 115–53 BC) was a ancient Rome, Roman general and statesman who played a key role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. He is often called "the richest man in Rome".Wallechinsky, Da ...

and

Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey ( ) or Pompey the Great, was a Roman general and statesman who was prominent in the last decades of the Roman Republic. ...

.

[Scullard 1982, chapters VI-VII] In 53 BC, the Triumvirate disintegrated at the death of Crassus. After being victorious in the

Gallic Wars

The Gallic Wars were waged between 58 and 50 BC by the Roman general Julius Caesar against the peoples of Gaul (present-day France, Belgium, and Switzerland). Gauls, Gallic, Germanic peoples, Germanic, and Celtic Britons, Brittonic trib ...

, Caesar

crossed the Rubicon

The phrase "crossing the Rubicon" is an idiom that means "passing a point of no return". Its meaning comes from allusion to the crossing of the river Rubicon from the north by Julius Caesar in early January 49 BC. The exact date is unknown. ...

and invaded Rome in 49 BC, rapidly defeating Pompey. Caesar was eventually granted a dictatorship for perpetuity but was murdered in 44 BC. Caesar's assassination caused political and social turmoil; without the dictator's leadership, Rome was ruled by his friend and colleague,

Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman people, Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the Crisis of the Roman Republic, transformation of the Roman Republic ...

.

Octavian

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in ...

(Caesar's adopted son), along with Antony and

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, established the

Second Triumvirate

The Second Triumvirate was an extraordinary commission and magistracy created at the end of the Roman republic for Mark Antony, Lepidus, and Octavian to give them practically absolute power. It was formally constituted by law on 27 November ...

. Lepidus was forced to retire in 36 BC after betraying Octavian in

Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

. Antony settled in Egypt with his lover,

Cleopatra VII

Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator (; The name Cleopatra is pronounced , or sometimes in both British and American English, see and respectively. Her name was pronounced in the Greek dialect of Egypt (see Koine Greek phonology). She was ...

, which was seen as an act of treason.

Following Antony's

Donations of Alexandria

The Donations of Alexandria (autumn 34 BC) was a political act by Cleopatra VII and Mark Antony in which they distributed lands held by Rome and Parthia among Cleopatra's children and gave them many titles, especially for Caesarion, the son of ...

, which gave Cleopatra the title of "Queen of Kings", and to their children the regal titles to the newly conquered Eastern territories, war between Octavian and Mark Antony broke out. Octavian annihilated Egyptian forces in the

Battle of Actium

The Battle of Actium was a naval battle fought between Octavian's maritime fleet, led by Marcus Agrippa, and the combined fleets of both Mark Antony and Cleopatra. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC in the Ionian Sea, near the former R ...

in 31 BC. Mark Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide. Rome thus possessed unchallenged

naval

A navy, naval force, military maritime fleet, war navy, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operatio ...

supremacy in the

North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

,

Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

coasts, Mediterranean,

Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

, and the

Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

.

Roman Empire

Octavian's leadership brought the

zenith

The zenith (, ) is the imaginary point on the celestial sphere directly "above" a particular location. "Above" means in the vertical direction (Vertical and horizontal, plumb line) opposite to the gravity direction at that location (nadir). The z ...

of the Roman civilization, which lasted for four decades. His adoption of the name ''

Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

'' in 27 BC is usually taken by historians as the beginning of the Roman Empire. Officially, the government was republican, but Augustus assumed absolute powers.

[Langley, Andrew and Souza, de Philip: ''The Roman Times'', pg.14, Candle Wick Press, 1996] The Senate granted Octavian a unique grade of

Proconsul

A proconsul was an official of ancient Rome who acted on behalf of a Roman consul, consul. A proconsul was typically a former consul. The term is also used in recent history for officials with delegated authority.

In the Roman Republic, military ...

ar ''imperium'', which gave him authority over all Proconsuls (military governors). The unruly

imperial provinces