ironmaking on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ferrous metallurgy is the

Ferrous metallurgy is the

Iron was extracted from

Iron was extracted from

About 1500 BC, increasing numbers of non-meteoritic, smelted iron objects appeared in

About 1500 BC, increasing numbers of non-meteoritic, smelted iron objects appeared in

Online version

accessed on 2010-02-11. Although iron objects dating from the

The history of ferrous metallurgy in the Indian subcontinent began in the 2nd millennium BC. Archaeological sites in the Gangetic plains have yielded iron implements dated between 1800 and 1200 BC. By the early 13th century BC, iron smelting was practiced on a large scale in India. In

The history of ferrous metallurgy in the Indian subcontinent began in the 2nd millennium BC. Archaeological sites in the Gangetic plains have yielded iron implements dated between 1800 and 1200 BC. By the early 13th century BC, iron smelting was practiced on a large scale in India. In  Perhaps as early as 500 BC, although certainly by 200 AD, high-quality steel was produced in southern India by the crucible technique. In this system, high-purity wrought iron, charcoal, and glass were mixed in a crucible and heated until the iron melted and absorbed the carbon. Iron chain was used in Indian

Perhaps as early as 500 BC, although certainly by 200 AD, high-quality steel was produced in southern India by the crucible technique. In this system, high-purity wrought iron, charcoal, and glass were mixed in a crucible and heated until the iron melted and absorbed the carbon. Iron chain was used in Indian

Numerous scholars have suggested that the Afanasievo culture may be responsible for the introduction of

Numerous scholars have suggested that the Afanasievo culture may be responsible for the introduction of  During the

During the

Archaeometallurgical scientific knowledge and technological development originated in numerous centers of Africa; the centers of origin were located in

Archaeometallurgical scientific knowledge and technological development originated in numerous centers of Africa; the centers of origin were located in

51

��59. Inhabitants of Termit, in eastern

53

��54. Similarly, smelting in bloomery-type furnaces appear in the

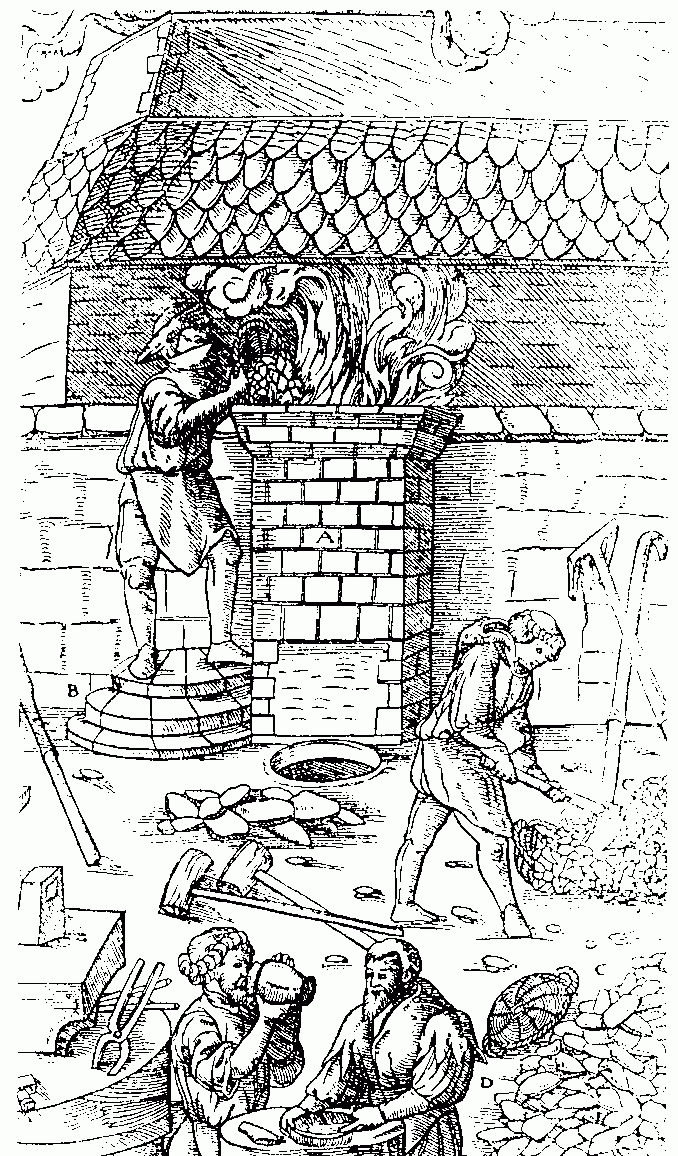

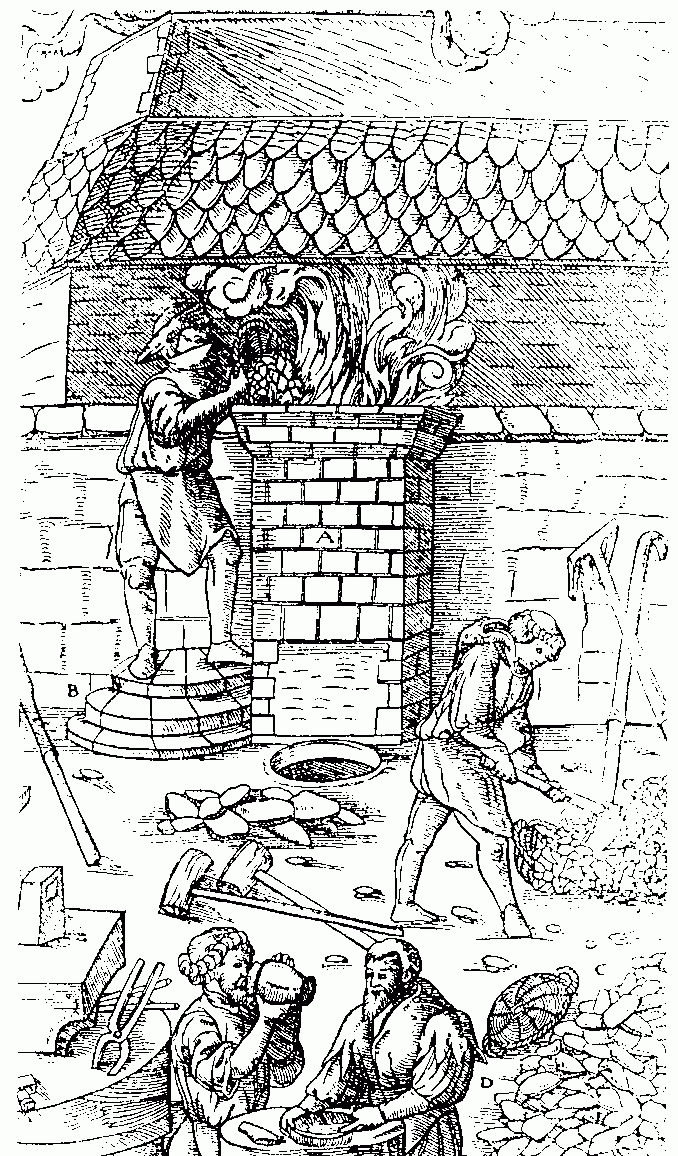

The preferred method of iron production in Europe until the development of the puddling process in 1783–84. Cast iron development lagged in Europe because wrought iron was the desired product and the intermediate step of producing cast iron involved an expensive blast furnace and further refining of pig iron to cast iron, which then required a labor and capital intensive conversion to wrought iron.

Through a good portion of the Middle Ages, in Western Europe, iron was still being made by the working of iron blooms into wrought iron. Some of the earliest casting of iron in Europe occurred in Sweden, in two sites,

The preferred method of iron production in Europe until the development of the puddling process in 1783–84. Cast iron development lagged in Europe because wrought iron was the desired product and the intermediate step of producing cast iron involved an expensive blast furnace and further refining of pig iron to cast iron, which then required a labor and capital intensive conversion to wrought iron.

Through a good portion of the Middle Ages, in Western Europe, iron was still being made by the working of iron blooms into wrought iron. Some of the earliest casting of iron in Europe occurred in Sweden, in two sites,

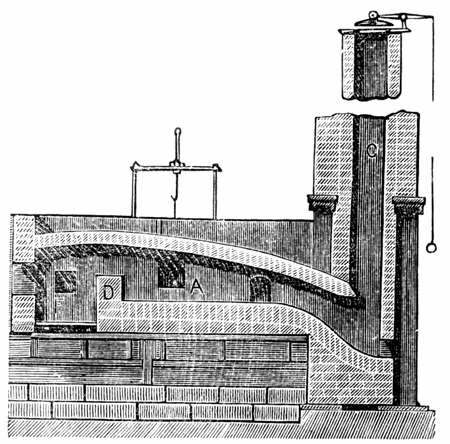

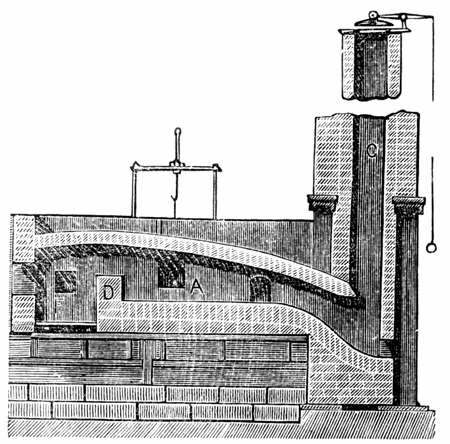

It was only after this that economically viable means of converting pig iron to bar iron began to be devised. A process known as potting and stamping was devised in the 1760s and improved in the 1770s, and seems to have been widely adopted in the West Midlands from about 1785. However, this was largely replaced by

It was only after this that economically viable means of converting pig iron to bar iron began to be devised. A process known as potting and stamping was devised in the 1760s and improved in the 1770s, and seems to have been widely adopted in the West Midlands from about 1785. However, this was largely replaced by

Apart from some production of puddled steel, English steel continued to be made by the cementation process, sometimes followed by remelting to produce crucible steel. These were batch-based processes whose raw material was bar iron, particularly Swedish oregrounds iron.

The problem of mass-producing cheap steel was solved in 1855 by Henry Bessemer, with the introduction of the

Apart from some production of puddled steel, English steel continued to be made by the cementation process, sometimes followed by remelting to produce crucible steel. These were batch-based processes whose raw material was bar iron, particularly Swedish oregrounds iron.

The problem of mass-producing cheap steel was solved in 1855 by Henry Bessemer, with the introduction of the

The steel industry is often considered an indicator of economic progress, because of the critical role played by steel in infrastructural and overall

The steel industry is often considered an indicator of economic progress, because of the critical role played by steel in infrastructural and overall

Ferrous metallurgy is the

Ferrous metallurgy is the metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the ...

of iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

and its alloy

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which in most cases at least one is a metal, metallic element, although it is also sometimes used for mixtures of elements; herein only metallic alloys are described. Metallic alloys often have prop ...

s. The earliest surviving prehistoric

Prehistory, also called pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the first known use of stone tools by hominins million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use o ...

iron artifacts, from the 4th millennium BC in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, were made from meteoritic iron-nickel. It is not known when or where the smelting

Smelting is a process of applying heat and a chemical reducing agent to an ore to extract a desired base metal product. It is a form of extractive metallurgy that is used to obtain many metals such as iron-making, iron, copper extraction, copper ...

of iron from ore

Ore is natural rock or sediment that contains one or more valuable minerals, typically including metals, concentrated above background levels, and that is economically viable to mine and process. The grade of ore refers to the concentration ...

s began, but by the end of the 2nd millennium BC iron was being produced from iron ore

Iron ores are rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be economically extracted. The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty red. The iron is usually found in the f ...

s in the region from Greece to India,Riederer, Josef; Wartke, Ralf-B.: "Iron", Cancik, Hubert; Schneider, Helmuth (eds.): Brill's New Pauly

The Pauly encyclopedias or the Pauly-Wissowa family of encyclopedias, are a set of related encyclopedia

An encyclopedia is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge, either general or special, in a particular field o ...

, Brill 2009Early Antiquity By I.M. Drakonoff. 1991. University of Chicago Press

The University of Chicago Press is the university press of the University of Chicago, a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. It is the largest and one of the oldest university presses in the United States. It pu ...

. . p. 372 The use of wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

(worked iron) was known by the 1st millennium BC, and its spread defined the Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

. During the medieval period, smiths in Europe found a way of producing wrought iron from cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content of more than 2% and silicon content around 1–3%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloying elements determine the form in which its car ...

, in this context known as pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate good used by the iron industry in the production of steel. It is developed by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with si ...

, using finery forge

A finery forge is a forge used to produce wrought iron from pig iron by decarburization in a process called "fining" which involved liquifying cast iron in a fining hearth and decarburization, removing carbon from the molten cast iron through Redo ...

s. All these processes required charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, ca ...

as fuel

A fuel is any material that can be made to react with other substances so that it releases energy as thermal energy or to be used for work (physics), work. The concept was originally applied solely to those materials capable of releasing chem ...

.

By the 4th century BC southern India had started exporting wootz steel

Wootz steel is a crucible steel characterized by a pattern of bands and high carbon content. These bands are formed by sheets of microscopic carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix in higher-carbon steel, or by ferrite and pea ...

, with a carbon content between pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate good used by the iron industry in the production of steel. It is developed by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with si ...

and wrought iron, to ancient China, Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. Archaeological evidence of cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content of more than 2% and silicon content around 1–3%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloying elements determine the form in which its car ...

appears in 5th-century BC China. New methods of producing it by carburizing bars of iron in the cementation process

The cementation process is an Obsolescence, obsolete technology for making steel by carburization of iron. Unlike modern steelmaking, it increased the amount of carbon in the iron. It was apparently developed before the 17th century. Derwentcot ...

were devised in the 17th century. During the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

, new methods of producing bar iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

by substituting coke for charcoal emerged, and these were later applied to produce steel

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon that demonstrates improved mechanical properties compared to the pure form of iron. Due to steel's high Young's modulus, elastic modulus, Yield (engineering), yield strength, Fracture, fracture strength a ...

, ushering in a new era of greatly increased use of iron and steel that some contemporaries described as a new "Iron Age".

In the late 1850s Henry Bessemer

Sir Henry Bessemer (19 January 1813 – 15 March 1898) was an English inventor, whose steel-making process would become the most important technique for making steel in the nineteenth century for almost one hundred years. He also played a sig ...

invented a new steelmaking process which involved blowing air through molten pig-iron to burn off carbon, and so producing mild steel. This and other 19th-century and later steel-making processes have displaced wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

. Today, wrought iron is no longer produced on a commercial scale, having been displaced by the functionally equivalent mild or low-carbon steel.

Meteoric iron

iron–nickel alloy

An iron–nickel alloy or nickel–iron alloy, abbreviated FeNi or NiFe, is a group of alloys consisting primarily of the elements nickel (Ni) and iron (Fe). It is the main constituent of the "iron" planetary cores and iron meteorites. In chemi ...

s, which comprise about 6% of all meteorites that fall on the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

. That source can often be identified with certainty because of the unique crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macros ...

line features (Widmanstätten pattern

Widmanstätten patterns (), also known as Thomson structures, are figures of long Phase (matter), phases of nickel–iron, found in the octahedrite shapes of iron meteorite crystals and some pallasites.

Iron meteorites are very often formed ...

s) of that material, which are preserved when the metal is worked cold or at low temperature. Those artifacts include, for example, a bead

A bead is a small, decorative object that is formed in a variety of shapes and sizes of a material such as stone, bone, shell, glass, plastic, wood, or pearl and with a small hole for threading or stringing. Beads range in size from under 1 ...

from the 5th millennium BC found in Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

and spear tips and ornaments from ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

and Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization, located in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (now south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age, early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. ...

around 4000 BC.Tylecote (1992). p. 3.

These early uses appear to have been largely ceremonial or decorative. Meteoric iron is very rare, and the metal was probably very expensive, perhaps more expensive than gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

. The early Hittites

The Hittites () were an Anatolian peoples, Anatolian Proto-Indo-Europeans, Indo-European people who formed one of the first major civilizations of the Bronze Age in West Asia. Possibly originating from beyond the Black Sea, they settled in mo ...

are known to have barter

In trade, barter (derived from ''bareter'') is a system of exchange (economics), exchange in which participants in a financial transaction, transaction directly exchange good (economics), goods or service (economics), services for other goods ...

ed iron (meteoric or smelted) for silver

Silver is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag () and atomic number 47. A soft, whitish-gray, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity of any metal. ...

, at a rate of 40 times the iron's weight, with Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , ''māt Aššur'') was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization that existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC and eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC t ...

in the first centuries of the second millennium BC.

Meteoric iron was also fashioned into tools in the Arctic

The Arctic (; . ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the North Pole, lying within the Arctic Circle. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway ( ...

when the Thule people

The Thule ( , ) or proto-Inuit were the ancestors of all modern Inuit. They developed in coastal Alaska by 1000 AD and expanded eastward across northern Canada, reaching Greenland by the 13th century. In the process, they replaced people of the ...

of Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

began making harpoon

A harpoon is a long, spear-like projectile used in fishing, whaling, sealing, and other hunting to shoot, kill, and capture large fish or marine mammals such as seals, sea cows, and whales. It impales the target and secures it with barb or ...

s, knives, ulus and other edged tools from pieces of the Cape York meteorite

The Cape York meteorite, also known as the Innaanganeq meteorite, is one of the largest known iron meteorites, classified as a medium octahedrite in chemical group IIIAB meteorites, IIIAB. In addition to many small fragments, at least eight large ...

. Typically pea-size bits of metal were cold-hammered into disks and fitted to a bone handle. These artifacts were also used as trade goods with other Arctic peoples: tools made from the Cape York meteorite have been found in archaeological sites more than distant. When the American polar explorer Robert Peary

Robert Edwin Peary Sr. (; May 6, 1856 – February 20, 1920) was an American explorer and officer in the United States Navy who made several expeditions to the Arctic in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was long credited as being ...

shipped the largest piece of the meteorite to the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. Located in Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 21 interconn ...

in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

in 1897, it still weighed over 33 ton

Ton is any of several units of measure of mass, volume or force. It has a long history and has acquired several meanings and uses.

As a unit of mass, ''ton'' can mean:

* the '' long ton'', which is

* the ''tonne'', also called the ''metric ...

s. Another example of a late use of meteoric iron is an adze

An adze () or adz is an ancient and versatile cutting tool similar to an axe but with the cutting edge perpendicular to the handle rather than parallel. Adzes have been used since the Stone Age. They are used for smoothing or carving wood in ha ...

from around 1000 AD found in Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

.

Native iron

Native

Native may refer to:

People

* '' Jus sanguinis'', nationality by blood

* '' Jus soli'', nationality by location of birth

* Indigenous peoples, peoples with a set of specific rights based on their historical ties to a particular territory

** Nat ...

iron in the metallic state occurs rarely as small inclusions in certain basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

rocks. Besides meteoritic iron, Thule people of Greenland have used native iron from the Disko region.

Iron smelting and the Iron Age

Iron smelting—the extraction of usable metal fromoxidized

Redox ( , , reduction–oxidation or oxidation–reduction) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of the reactants change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is ...

iron ores—is more difficult than tin

Tin is a chemical element; it has symbol Sn () and atomic number 50. A silvery-colored metal, tin is soft enough to be cut with little force, and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, a bar of tin makes a sound, the ...

and copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

smelting. While these metals and their alloys can be cold-worked or melted in relatively simple furnaces (such as the kilns used for pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other raw materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. The place where such wares are made by a ''potter'' is al ...

) and cast into molds, smelted iron requires hot-working and can be melted only in specially designed furnaces. Iron is a common impurity in copper ores and iron ore was sometimes used as a flux

Flux describes any effect that appears to pass or travel (whether it actually moves or not) through a surface or substance. Flux is a concept in applied mathematics and vector calculus which has many applications in physics. For transport phe ...

, thus it is not surprising that humans mastered the technology of smelted iron only after several millennia of bronze metallurgy.

The place and time for the discovery of iron smelting is not known, partly because of the difficulty of distinguishing metal extracted from nickel-containing ores from hot-worked meteoritic iron. The archaeological evidence seems to point to the Middle East area, during the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

in the 3rd millennium BC. However, wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

artifacts remained a rarity until the 12th century BC.

The Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

is conventionally defined by the widespread replacement of bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals (such as phosphorus) or metalloid ...

weapons and tools with those of iron and steel.Waldbaum (1978). pp. 56–58. That transition happened at different times in different places, as the technology spread. Mesopotamia was fully into the Iron Age by 900 BC. Although Egypt produced iron artifacts, bronze remained dominant until its conquest by Assyria in 663 BC. The Iron Age began in India about 1200 BC, in Central Europe about 800 BC, and in China about 300 BC. Around 500 BC, the Nubia

Nubia (, Nobiin language, Nobiin: , ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the confluence of the Blue Nile, Blue and White Nile, White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), and the Cataracts of the Nile, first cataract ...

ns, who had learned from the Assyrians the use of iron and were expelled from Egypt, became major manufacturers and exporters of iron.

Ancient Near East

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

, Anatolia and Egypt. Nineteen meteoric iron objects were found in the tomb

A tomb ( ''tumbos'') or sepulchre () is a repository for the remains of the dead. It is generally any structurally enclosed interment space or burial chamber, of varying sizes. Placing a corpse into a tomb can be called '' immurement'', alth ...

of Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

ian ruler Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun or Tutankhamen, (; ), was an Egyptian pharaoh who ruled during the late Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt. Born Tutankhaten, he instituted the restoration of the traditional polytheistic form of an ...

, who died in 1323 BC, including an iron dagger with a golden hilt, an Eye of Horus

The Eye of Horus, also known as left ''wedjat'' eye or ''udjat'' eye, specular to the Eye of Ra (right ''wedjat'' eye), is a concept and symbol in ancient Egyptian religion that represents well-being, healing, and protection. It derives from th ...

, the mummy's head-stand and sixteen models of an artisan's tools. An Ancient Egyptian sword bearing the name of pharaoh Merneptah

Merneptah () or Merenptah (reigned July or August 1213–2 May 1203 BCE) was the fourth pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Nineteenth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt. According to contemporary historical records, he ruled Egypt for almost ten y ...

as well as a battle axe

A battle axe (also battle-axe, battle ax, or battle-ax) is an axe specifically designed for combat. Battle axes were designed differently to utility axes, with blades more akin to cleavers than to wood axes. Many were suitable for use in one ha ...

with an iron blade and gold-decorated bronze shaft were both found in the excavation of Ugarit

Ugarit (; , ''ủgrt'' /ʾUgarītu/) was an ancient port city in northern Syria about 10 kilometers north of modern Latakia. At its height it ruled an area roughly equivalent to the modern Latakia Governorate. It was discovered by accident in 19 ...

.Richard Cowen, ''The Age of Iron'', Chapter 5 in a series of essays on Geology, History, and People prepares for a course of the University of California at DavisOnline version

accessed on 2010-02-11. Although iron objects dating from the

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

have been found across the Eastern Mediterranean, bronzework appears to have greatly predominated during this period.Waldbaum (1978): 23. As the technology spread, iron came to replace bronze as the dominant metal used for tools and weapons across the Eastern Mediterranean (the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

, Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

, Anatolia and Egypt).

Iron was originally smelted in bloomeries, furnaces where bellows

A bellows or pair of bellows is a device constructed to furnish a strong blast of air. The simplest type consists of a flexible bag comprising a pair of rigid boards with handles joined by flexible leather sides enclosing an approximately airtig ...

were used to force air through a pile of iron ore and burning charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, ca ...

. The carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a poisonous, flammable gas that is colorless, odorless, tasteless, and slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the si ...

produced by the charcoal reduced the iron oxide

An iron oxide is a chemical compound composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Ferric oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of which is rust.

Iron ...

from the ore to metallic iron. The bloomery, however, was not hot enough to melt the iron, so the metal collected in the bottom of the furnace as a spongy mass, or ''bloom''. Workers then repeatedly beat and folded it to force out the molten slag

The general term slag may be a by-product or co-product of smelting (pyrometallurgical) ores and recycled metals depending on the type of material being produced. Slag is mainly a mixture of metal oxides and silicon dioxide. Broadly, it can be c ...

. This laborious, time-consuming process produced wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

, a malleable but fairly soft alloy.

Concurrent with the transition from bronze to iron was the discovery of carburization

Carburizing, or carburising, is a heat treatment process in which iron or steel absorbs carbon while the metal is heated in the presence of a carbon-bearing material, such as charcoal or carbon monoxide. The intent is to make the metal harder ...

, the process of adding carbon to wrought iron. While the iron bloom contained some carbon, the subsequent hot-working oxidized

Redox ( , , reduction–oxidation or oxidation–reduction) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of the reactants change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is ...

most of it. Smiths in the Middle East discovered that wrought iron could be turned into a much harder product by heating the finished piece in a bed of charcoal, and then quench

In materials science, quenching is the rapid cooling of a workpiece in water, gas, oil, polymer, air, or other fluids to obtain certain material properties. A type of heat treating, quenching prevents undesired low-temperature processes, such ...

ing it in water or oil. This procedure turned the outer layers of the piece into steel

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon that demonstrates improved mechanical properties compared to the pure form of iron. Due to steel's high Young's modulus, elastic modulus, Yield (engineering), yield strength, Fracture, fracture strength a ...

, an alloy of iron and iron carbides, with an inner core of less brittle iron.

Theories on the origin of iron smelting

The development of iron smelting was traditionally attributed to theHittites

The Hittites () were an Anatolian peoples, Anatolian Proto-Indo-Europeans, Indo-European people who formed one of the first major civilizations of the Bronze Age in West Asia. Possibly originating from beyond the Black Sea, they settled in mo ...

of Anatolia of the Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

.Muhly, James D. 'Metalworking/Mining in the Levant' pp. 174–183 in ''Near Eastern Archaeology'' ed. Suzanne Richard (2003), pp. 179–180. It was believed that they maintained a monopoly on iron working, and that their empire had been based on that advantage. According to that theory, the ancient Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples were a group of tribes hypothesized to have attacked Ancient Egypt, Egypt and other Eastern Mediterranean regions around 1200 BC during the Late Bronze Age. The hypothesis was proposed by the 19th-century Egyptology, Egyptologis ...

, who invaded the Eastern Mediterranean and destroyed the Hittite empire at the end of the Late Bronze Age, were responsible for spreading the knowledge through that region. This theory is no longer held in the mainstream of scholarship, since there is no archaeological evidence of the alleged Hittite monopoly. While there are some iron objects from Bronze Age Anatolia, the number is comparable to iron objects found in Egypt and other places of the same time period, and only a small number of those objects were weapons.

A more recent theory claims that the development of iron technology was driven by the disruption of the copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

and tin

Tin is a chemical element; it has symbol Sn () and atomic number 50. A silvery-colored metal, tin is soft enough to be cut with little force, and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, a bar of tin makes a sound, the ...

trade routes, due to the collapse of the empires at the end of the Late Bronze Age. These metals, especially tin, were not widely available and metal workers had to transport them over long distances, whereas iron ores were widely available. However, no known archaeological evidence suggests a shortage of bronze or tin in the Early Iron Age. Bronze objects remained abundant, and these objects have the same percentage of tin as those from the Late Bronze Age.

Indian subcontinent

Southern India

South India, also known as Southern India or Peninsular India, is the southern part of the Deccan Peninsula in India encompassing the states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Telangana as well as the union territories of ...

(present day Mysore

Mysore ( ), officially Mysuru (), is a city in the southern Indian state of Karnataka. It is the headquarters of Mysore district and Mysore division. As the traditional seat of the Wadiyar dynasty, the city functioned as the capital of the ...

) iron was in use 12th to 11th centuries BC. The technology of iron metallurgy advanced in the politically stable Maurya

The Maurya Empire was a geographically extensive Iron Age historical power in South Asia with its power base in Magadha. Founded by Chandragupta Maurya around c. 320 BCE, it existed in loose-knit fashion until 185 BCE. The primary sourc ...

period and during a period of peaceful settlements in the 1st millennium BC.

Iron artifacts such as spikes

The SPIKES protocol is a method used in clinical medicine to break bad news to patients and families. As receiving bad news can cause distress and anxiety, clinicians need to deliver the news carefully. Using the SPIKES method for introducing and ...

, knives

A knife (: knives; from Old Norse 'knife, dirk') is a tool or weapon with a cutting edge or blade, usually attached to a handle or hilt. One of the earliest tools used by humanity, knives appeared at least 2.5 million years ago, as evidenced ...

, dagger

A dagger is a fighting knife with a very sharp point and usually one or two sharp edges, typically designed or capable of being used as a cutting or stabbing, thrusting weapon.State v. Martin, 633 S.W.2d 80 (Mo. 1982): This is the dictionary or ...

s, arrow

An arrow is a fin-stabilized projectile launched by a bow. A typical arrow usually consists of a long, stiff, straight shaft with a weighty (and usually sharp and pointed) arrowhead attached to the front end, multiple fin-like stabilizers c ...

-heads, bowls

Bowls, also known as lawn bowls or lawn bowling, is a sport in which players try to roll their ball (called a bowl) closest to a smaller ball (known as a "jack" or sometimes a "kitty"). The bowls are shaped (biased), so that they follow a curve ...

, spoon

A spoon (, ) is a utensil consisting of a shallow bowl (also known as a head), oval or round, at the end of a handle. A type of cutlery (sometimes called flatware in the United States), especially as part of a table setting, place setting, it ...

s, saucepan

A saucepan is one of the basic forms of cookware (not technically a pan), in the form of a round cooking vessel, typically deep, and wide enough to hold at least of water, with sizes typically ranging up to , and having a long handle protrudi ...

s, axe

An axe (; sometimes spelled ax in American English; American and British English spelling differences#Miscellaneous spelling differences, see spelling differences) is an implement that has been used for thousands of years to shape, split, a ...

s, chisel

A chisel is a hand tool with a characteristic Wedge, wedge-shaped cutting edge on the end of its blade. A chisel is useful for carving or cutting a hard material such as woodworking, wood, lapidary, stone, or metalworking, metal.

Using a chi ...

s, tongs

Tongs are a type of tool used to grip and lift objects instead of holding them directly with hands. There are many forms of tongs adapted to their specific use. Design variations include resting points so that the working end of the tongs d ...

, door fittings, etc., dated from 600 to 200 BC, have been discovered at several archaeological sites of India.Marco Ceccarelli (2000). ''International Symposium on History of Machines and Mechanisms: Proceedings HMM Symposium''. Springer. . p. 218 The Greek historian Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

wrote the first western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

account of the use of iron in India. The Indian mythological texts, the Upanishad

The Upanishads (; , , ) are late Vedic and post-Vedic Sanskrit texts that "document the transition from the archaic ritualism of the Veda into new religious ideas and institutions" and the emergence of the central religious concepts of Hind ...

s, have mentions of weaving, pottery and metallurgy, as well. The Romans had high regard for the excellence of steel from India in the time of the Gupta Empire

The Gupta Empire was an Indian empire during the classical period of the Indian subcontinent which existed from the mid 3rd century to mid 6th century CE. At its zenith, the dynasty ruled over an empire that spanned much of the northern Indian ...

.

Perhaps as early as 500 BC, although certainly by 200 AD, high-quality steel was produced in southern India by the crucible technique. In this system, high-purity wrought iron, charcoal, and glass were mixed in a crucible and heated until the iron melted and absorbed the carbon. Iron chain was used in Indian

Perhaps as early as 500 BC, although certainly by 200 AD, high-quality steel was produced in southern India by the crucible technique. In this system, high-purity wrought iron, charcoal, and glass were mixed in a crucible and heated until the iron melted and absorbed the carbon. Iron chain was used in Indian suspension bridge

A suspension bridge is a type of bridge in which the deck (bridge), deck is hung below suspension wire rope, cables on vertical suspenders. The first modern examples of this type of bridge were built in the early 1800s. Simple suspension bridg ...

s as early as the 4th century.

Wootz steel

Wootz steel is a crucible steel characterized by a pattern of bands and high carbon content. These bands are formed by sheets of microscopic carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix in higher-carbon steel, or by ferrite and pea ...

was produced in India and Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

from around 300 BC. Wootz steel is famous from Classical Antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

for its durability and ability to hold an edge. When asked by King Porus to select a gift, Alexander

Alexander () is a male name of Greek origin. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here ar ...

is said to have chosen, over gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

or silver

Silver is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag () and atomic number 47. A soft, whitish-gray, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity of any metal. ...

, thirty pounds of steel. Wootz steel was originally a complex alloy with iron as its main component together with various trace element

__NOTOC__

A trace element is a chemical element of a minute quantity, a trace amount, especially used in referring to a micronutrient, but is also used to refer to minor elements in the composition of a rock, or other chemical substance.

In nutr ...

s. Recent studies have suggested that its qualities may have been due to the formation of carbon nanotubes

A carbon nanotube (CNT) is a tube made of carbon with a diameter in the nanometre range (nanoscale). They are one of the allotropes of carbon. Two broad classes of carbon nanotubes are recognized:

* ''Single-walled carbon nanotubes'' (''SWC ...

in the metal. According to Will Durant

William James Durant (; November 5, 1885 – November 7, 1981) was an American historian and philosopher, best known for his eleven-volume work, '' The Story of Civilization'', which contains and details the history of Eastern and Western civil ...

, the technology passed to the Persians

Persians ( ), or the Persian people (), are an Iranian ethnic group from West Asia that came from an earlier group called the Proto-Iranians, which likely split from the Indo-Iranians in 1800 BCE from either Afghanistan or Central Asia. They ...

and from them to Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

s who spread it through the Middle East.Will Durant (), '' The Story of Civilization I: Our Oriental Heritage'' In the 16th century, the Dutch carried the technology from South India to Europe, where it was mass-produced.

Steel was produced in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

from 300 BC by furnaces blown by the monsoon winds. The furnaces were dug into the crests of hills, and the wind was diverted into the air vents by long trenches. This arrangement created a zone of high pressure at the entrance, and a zone of low pressure at the top of the furnace. The flow is believed to have allowed higher temperatures than bellows-driven furnaces could produce, resulting in better-quality iron. Steel made in Sri Lanka was traded extensively within the region and in the Islamic world

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is ...

.

One of the world's foremost metallurgical curiosities is an iron pillar located in the Qutb complex

The Qutb Minar complex are monuments and buildings from the Delhi Sultanate at Mehrauli in Delhi, India. Construction of the Qutub Minar "victory tower" in the complex, named after the religious figure Sufi Saint Khwaja Qutbuddin Bakhtiar Kaki, w ...

in Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, but spread chiefly to the west, or beyond its Bank (geography ...

. The pillar is made of wrought iron (98% Fe), is almost seven meters high and weighs more than six tonnes. The pillar was erected by Chandragupta II

Chandragupta II (r.c. 375–415), also known by his title Vikramaditya, as well as Chandragupta Vikramaditya, was an emperor of the Gupta Empire. Modern scholars generally identify him with King Chandra of the Iron pillar of Delhi, Delhi iron ...

Vikramaditya and has withstood 1,600 years of exposure to heavy rains with relatively little corrosion

Corrosion is a natural process that converts a refined metal into a more chemically stable oxide. It is the gradual deterioration of materials (usually a metal) by chemical or electrochemical reaction with their environment. Corrosion engine ...

.

China

Numerous scholars have suggested that the Afanasievo culture may be responsible for the introduction of

Numerous scholars have suggested that the Afanasievo culture may be responsible for the introduction of metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the ...

to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

. In particular, contacts between the Afanasievo culture and the Majiayao culture

The Majiayao culture was a group of Neolithic communities who lived primarily in the upper Yellow River region in eastern Gansu, eastern Qinghai and northern Sichuan, China. The culture existed from 3300 to 2000 BC. The Majiayao culture represent ...

and the Qijia culture

The Qijia culture (2400 BC – 1600 BC) was an early Bronze Age culture distributed around the upper Yellow River region of Gansu (centered in Lanzhou) and eastern Qinghai, China. It is regarded as one of the earliest bronze cultures in China.

...

are considered for the transmission of bronze technology.

In 2008, two iron fragments were excavated at the Mogou site, in Gansu

Gansu is a provinces of China, province in Northwestern China. Its capital and largest city is Lanzhou, in the southeastern part of the province. The seventh-largest administrative district by area at , Gansu lies between the Tibetan Plateau, Ti ...

. They have been dated to the 14th century BC, belonging to the period of Siwa culture. One of the fragments was made of bloomery iron rather than meteoritic iron.p. xl, Historical Dictionary of Ancient Greek Warfare, J, Woronoff & I. Spence

The earliest iron artifacts made from bloomeries in China date to end of the 9th century BC. Cast iron was used in ancient China

The history of China spans several millennia across a wide geographical area. Each region now considered part of the Chinese world has experienced periods of unity, fracture, prosperity, and strife. Chinese civilization first emerged in the Y ...

for warfare, agriculture and architecture. Around 500 BC, metalworkers in the southern state of Wu

Wu () was a state during the Western Zhou dynasty and the Spring and Autumn period, outside the Zhou cultural sphere. It was also known as Gouwu () or Gongwu () from the pronunciation of the local language. Wu was located at the mouth of th ...

achieved a temperature of 1130 °C. At this temperature, iron combines with 4.3% carbon and melts. The liquid iron can be cast

Cast may refer to:

Music

* Cast (band), an English alternative rock band

* Cast (Mexican band), a progressive Mexican rock band

* The Cast, a Scottish musical duo: Mairi Campbell and Dave Francis

* ''Cast'', a 2012 album by Trespassers William ...

into molds, a method far less laborious than individually forging each piece of iron from a bloom.

Cast iron is rather brittle and unsuitable for striking implements. It can be ''decarburized'' to steel or wrought iron by heating it in air for several days. In China, these iron working methods spread northward, and by 300 BC, iron was the material of choice throughout China for most tools and weapons. A mass grave in Hebei

Hebei is a Provinces of China, province in North China. It is China's List of Chinese administrative divisions by population, sixth-most populous province, with a population of over 75 million people. Shijiazhuang is the capital city. It bor ...

province, dated to the early 3rd century BC, contains several soldiers buried with their weapons and other equipment. The artifacts recovered from this grave are variously made of wrought iron, cast iron, malleabilized cast iron, and quench-hardened steel, with only a few, probably ornamental, bronze weapons.

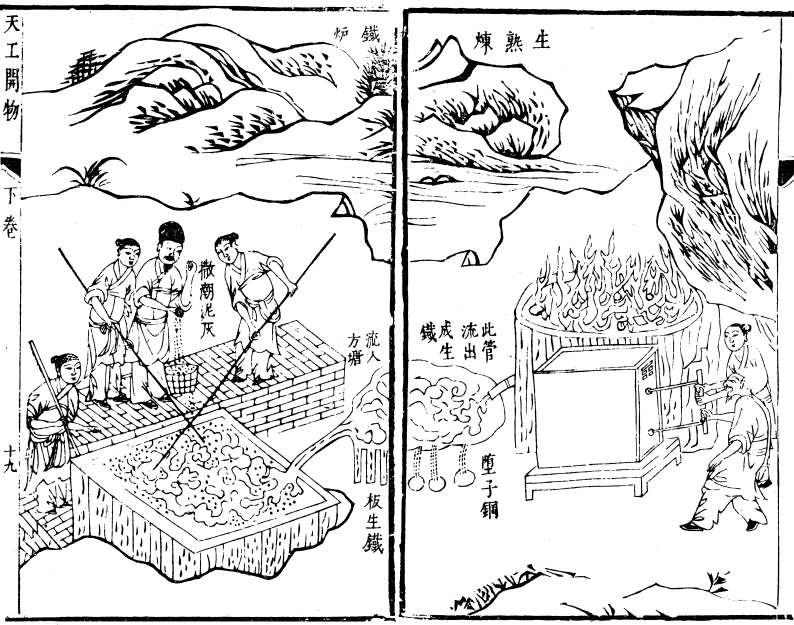

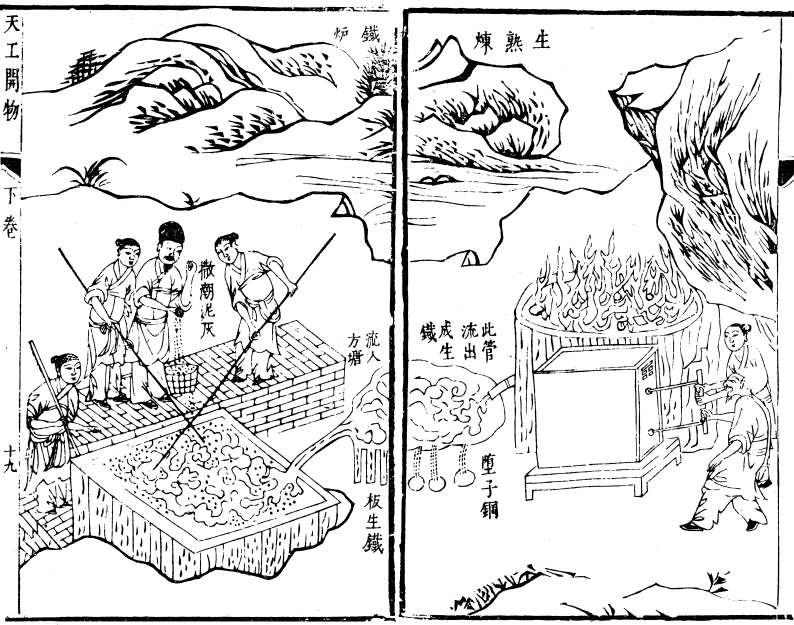

During the

During the Han dynasty

The Han dynasty was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC9 AD, 25–220 AD) established by Liu Bang and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–206 BC ...

(202 BC–220 AD), the government established ironworking as a state monopoly, repealed during the latter half of the dynasty and returned to private entrepreneurship, and built a series of large blast furnaces in Henan

Henan; alternatively Honan is a province in Central China. Henan is home to many heritage sites, including Yinxu, the ruins of the final capital of the Shang dynasty () and the Shaolin Temple. Four of the historical capitals of China, Lu ...

province, each capable of producing several tons of iron per day. By this time, Chinese metallurgists had discovered how to fine molten pig iron, stirring it in the open air until it lost its carbon and could be hammered (wrought). In modern Mandarin- Chinese, this process is now called ''chao'', literally stir frying

Stir frying ( zh, c= 炒, p=chǎo, w=ch'ao3, cy=cháau) is a cooking technique in which ingredients are fried in a small amount of very hot oil while being stirred or tossed in a wok. The technique originated in China and in recent centuries ...

. Pig iron is known as 'raw iron', while wrought iron is known as 'cooked iron'. By the 1st century BC, Chinese metallurgists had found that wrought iron and cast iron could be melted together to yield an alloy of intermediate carbon content, that is, steel.

According to legend, the sword of Liu Bang

Emperor Gaozu of Han (2561 June 195 BC), also known by his given name Liu Bang, was the founder and first emperor of the Han dynasty, reigning from 202 to 195 BC. He is considered by traditional Chinese historiography to be one o ...

, the first Han emperor, was made in this fashion. Some texts of the era mention "harmonizing the hard and the soft" in the context of ironworking; the phrase may refer to this process. The ancient city of Wan ( Nanyang) from the Han period forward was a major center of the iron and steel industry. Along with their original methods of forging steel, the Chinese had also adopted the production methods of creating Wootz steel, an idea imported from India to China by the 5th century AD.

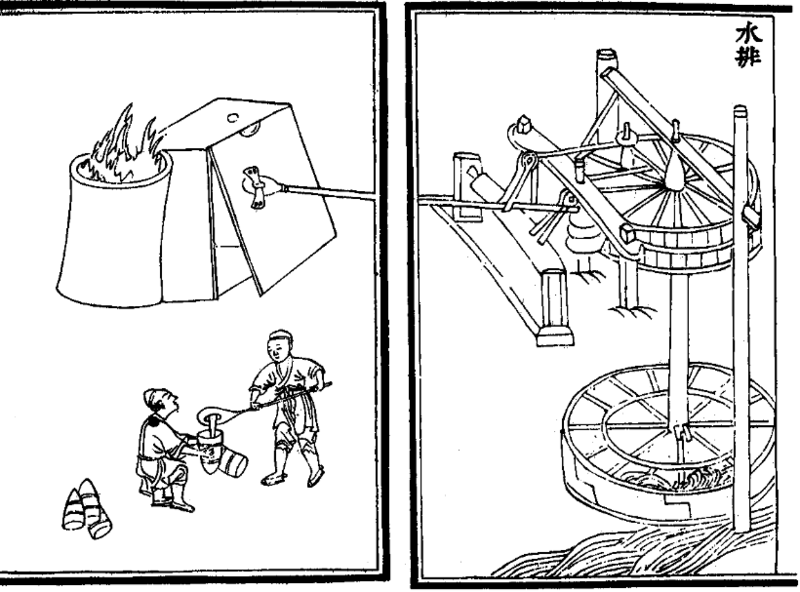

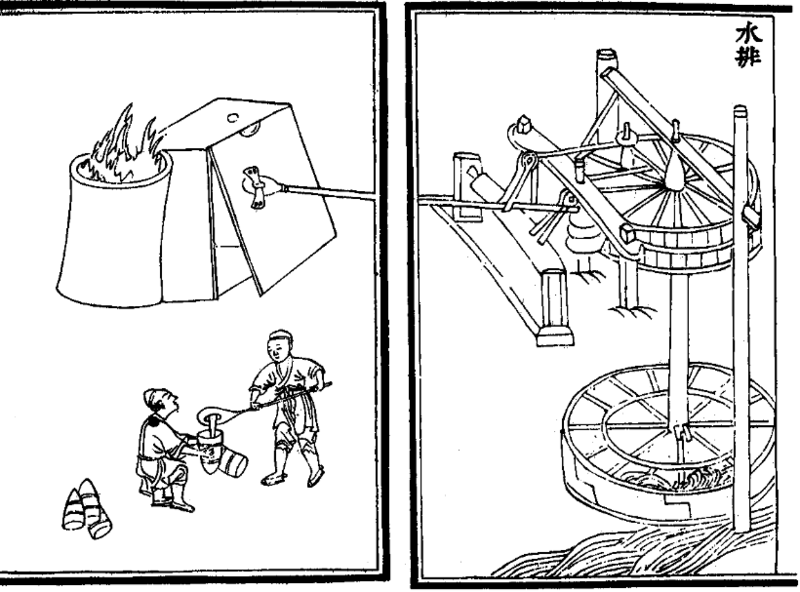

During the Han dynasty, the Chinese were also the first to apply hydraulic

Hydraulics () is a technology and applied science using engineering, chemistry, and other sciences involving the mechanical properties and use of liquids. At a very basic level, hydraulics is the liquid counterpart of pneumatics, which concer ...

power (i.e. a waterwheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the kinetic energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a large wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with numerous blade ...

) in working the bellows of the blast furnace. This was recorded in the year 31 AD, as an innovation by the Chinese mechanical engineer and politician Du Shi

Du Shi (, d. 38'' Book of Later Han'', vol. 31Crespigny, 183.) was a Chinese hydrologist, inventor, mechanical engineer, metallurgist, and politician of the Eastern Han dynasty. Du Shi is credited with being the first to apply hydraulic power ...

, Prefect

Prefect (from the Latin ''praefectus'', substantive adjectival form of ''praeficere'': "put in front", meaning in charge) is a magisterial title of varying definition, but essentially refers to the leader of an administrative area.

A prefect' ...

of Nanyang. Although Du Shi was the first to apply water power to bellows in metallurgy, the first drawn and printed illustration of its operation with water power appeared in 1313 AD, in the Yuan dynasty era text called the ''Nong Shu''.

In the 11th century, there is evidence of the production of steel in Song China using two techniques: a "berganesque" method that produced inferior, heterogeneous steel and a precursor to the modern Bessemer process that utilized partial decarbonization via repeated forging under a cold blast. By the 11th century, there was a large amount of deforestation in China due to the iron industry's demands for charcoal.(2006). 158. By this time however, the Chinese had learned to use bituminous coke to replace charcoal, and with this switch in resources many acres of prime timberland in China were spared.

Iron Age Europe

The earliest iron objects found in Europe date from the 3rd millennium BC, and are assigned to theYamnaya culture

The Yamnaya ( ) or Yamna culture ( ), also known as the Pit Grave culture or Ochre Grave culture, is a late Copper Age to early Bronze Age archaeological culture of the region between the Southern Bug, Dniester, and Ural rivers (the Pontic–C ...

and Catacomb culture

The Catacomb culture (, ) was a Bronze Age culture which flourished on the Pontic steppe in 2,500–1,950 BC.Parpola, Asko, (2012)"Formation of the Indo-European and Uralic (Finno-Ugric) language families in the light of archaeology: Revised an ...

. Eastern Europe, especially the Cis-Ural region, shows the highest concentration of early and middle Bronze Age iron objects in western Eurasia, though most of these are thought to consist of meteoric Iron. A knife blade from the Catacomb culture dated to c. 2300 BC is thought to have been made from smelted iron. During most of the Middle and Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

in Central Europe, iron was present, though scarce. It was used for personal ornaments and small knives, for repairs on bronzes, and for bimetallic items. Early smelted iron finds from central Europe include an iron knife or sickle from Ganovce in Slovakia, possibly dating from the 18th-15th century BC, an iron ring from Vorwohlde in Germany dating from circa the 15th century BC, and an iron chisel from Heegermühle in Germany dating from circa 1000 BC. Smelted iron objects are known from Eastern Europe dating from after 1200 BC.

In the 11th century BC iron swords replaced bronze swords in Southern Europe, especially in Greece, and in the 10th century BC iron became the prevailing metal in use. In the Carpathian Basin

The Pannonian Basin, with the term Carpathian Basin being sometimes preferred in Hungarian literature, is a large sedimentary basin situated in southeastern Central Europe. After the Treaty of Trianon following World War I, the geomorphologic ...

there is a significant increase in iron finds dating from the 10th century BC onwards, with some finds possibly dating as early as the 12th century BC. Iron swords have been found in central Europe dating from the 10th century BC; however, the Iron Age began in earnest with the Hallstatt culture

The Hallstatt culture was the predominant Western Europe, Western and Central European archaeological culture of the Late Bronze Age Europe, Bronze Age (Hallstatt A, Hallstatt B) from the 12th to 8th centuries BC and Early Iron Age Europe (Hallst ...

from 800 BC. Steel was produced from circa 800 BC as part of the production of swords, and swords made entirely of high-carbon steel are known from pre-Roman period. Evidence for iron metallurgy in Britain dates from the 10th century BC, with the beginning of the Iron Age dated to the 8th century BC. The production of high-carbon steel is attested in Britain from circa 490 BC. Iron metallurgy began to be practised in Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

during the later Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

from at least the 9th century BC, with evidence for steel production from 800–700 BC. Iron and steel artefacts, including high-carbon steel, were manufactured in northern Sweden, Finland and Norway (in the Cap of the North) from c. 200–50 BC. Evidence for iron metallurgy in Italy and Sardinia dates from the Late Bronze Age (c. 1350-950 BC). High-carbon steel tools were produced in Iberia (Portugal) from c. 900 BC.

From 500 BC the La Tène culture

The La Tène culture (; ) was a Iron Age Europe, European Iron Age culture. It developed and flourished during the late Iron Age (from about 450 BC to the Roman Republic, Roman conquest in the 1st century BC), succeeding the early Iron Age ...

saw a significant increase in iron production, with iron metallurgy also becoming common in southern Scandinavia. The spread of ironworking in Central and Western Europe is associated with Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foot ...

expansion. By the 1st century BC, Noric steel

Noric steel is a historical steel from Noricum, a kingdom located in modern Austria and Slovenia.

The proverbial hardness of Noric steel is expressed by Ovid: ''"...durior ..ferro quod noricus excoquit ignis..."'' which roughly translates to "... ...

was famous for its quality and sought-after by the Roman military. The annual output of iron in the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

is estimated at 84,750 tonnes

The tonne ( or ; symbol: t) is a unit of mass equal to 1,000 kilograms. It is a non-SI unit accepted for use with SI. It is also referred to as a metric ton in the United States to distinguish it from the non-metric units of the s ...

.

The production of ultrahigh carbon steel is attested at the Germanic site of Heeten

Raalte () is a Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality and a town in the heart of the region of Salland in the Netherlands, Dutch Provinces of the Netherlands, province of Overijssel.

Population centres

The municipality consists of the ...

in the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

from the 2nd to 4th/5th centuries AD, in the Late Roman Iron Age.

Sub-Saharan Africa

Archaeometallurgical scientific knowledge and technological development originated in numerous centers of Africa; the centers of origin were located in

Archaeometallurgical scientific knowledge and technological development originated in numerous centers of Africa; the centers of origin were located in West Africa

West Africa, also known as Western Africa, is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations geoscheme for Africa#Western Africa, United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Gha ...

, Central Africa

Central Africa (French language, French: ''Afrique centrale''; Spanish language, Spanish: ''África central''; Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''África Central'') is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries accordin ...

, and East Africa

East Africa, also known as Eastern Africa or the East of Africa, is a region at the eastern edge of the Africa, African continent, distinguished by its unique geographical, historical, and cultural landscape. Defined in varying scopes, the regi ...

; consequently, as these origin centers are located within inner Africa, these archaeometallurgical developments are thus native African technologies. Iron metallurgical development occurred 2631 BCE – 2458 BCE at Lejja, in Nigeria, 2136 BCE – 1921 BCE at Obui, in Central Africa Republic, 1895 BCE – 1370 BCE at Tchire Ouma 147, in Niger, and 1297 BCE – 1051 BCE at Dekpassanware, in Togo.

Though there is some uncertainty, some archaeologists believe that iron metallurgy was developed independently in sub-Saharan Africa (possibly in West Africa).Eggert (2014). pp51

��59. Inhabitants of Termit, in eastern

Niger

Niger, officially the Republic of the Niger, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is a unitary state Geography of Niger#Political geography, bordered by Libya to the Libya–Niger border, north-east, Chad to the Chad–Niger border, east ...

, smelted iron around 1500 BC.

In the region of the Aïr Mountains

The Aïr Mountains or Aïr Massif (Air Tamajeq language, Tamajăq: ''Ayǝr''; Hausa language, Hausa: Eastern ''Azbin'', Western ''Abzin'') is a triangular massif, located in northern Niger, within the Sahara. Part of the West Sa ...

in Niger

Niger, officially the Republic of the Niger, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is a unitary state Geography of Niger#Political geography, bordered by Libya to the Libya–Niger border, north-east, Chad to the Chad–Niger border, east ...

there are also signs of independent copper smelting between 2500 and 1500 BC. The process was not in a developed state, indicating smelting was not foreign. It became mature about 1500 BC.

Archaeological sites containing iron smelting furnaces and slag have also been excavated at sites in the Nsukka region of southeast Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

in what is now Igboland

Igbo land ( Standard ) is a cultural and common linguistic region in southeastern Nigeria which is the indigenous homeland of the Igbo people. Geographically, it is divided into two sections, eastern (the larger of the two) and western. Its popu ...

: dating to 2000 BC at the site of Lejja (Eze-Uzomaka 2009) and to 750 BC and at the site of Opi (Holl 2009). The site of Gbabiri (in the Central African Republic) has yielded evidence of iron metallurgy, from a reduction furnace and blacksmith workshop; with earliest dates of 896–773 BC and 907–796 BC respectively.Eggert (2014). pp53

��54. Similarly, smelting in bloomery-type furnaces appear in the

Nok culture

The Nok culture is a population whose material remains are named after the Ham people, Ham village of Nok in Southern Kaduna, southern Kaduna State of Nigeria, where their terracotta sculptures were first discovered in 1928. The Nok people and ...

of central Nigeria by about 550 BC and possibly a few centuries earlier.

There is also evidence that carbon steel

Carbon steel is a steel with carbon content from about 0.05 up to 2.1 percent by weight. The definition of carbon steel from the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) states:

* no minimum content is specified or required for chromium, cobalt ...

was made in Western Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

by the ancestors of the Haya people as early as 2,300 to 2,000 years ago (about 300 BC or soon after) by a complex process of "pre-heating" allowing temperatures inside a furnace to reach 1300 to 1400 °C.

Iron and copper working spread southward through the continent, reaching the Cape

A cape is a clothing accessory or a sleeveless outer garment of any length that hangs loosely and connects either at the neck or shoulders. They usually cover the back, shoulders, and arms. They come in a variety of styles and have been used th ...

around AD 200. The widespread use of iron revolutionized the Bantu-speaking farming communities who adopted it, driving out and absorbing the rock tool using hunter-gatherer societies they encountered as they expanded to farm wider areas of savanna

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) biome and ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach th ...

. The technologically superior Bantu-speakers spread across southern Africa and became wealthy and powerful, producing iron for tools and weapons in large, industrial quantities.

The earliest records of bloomery-type furnaces in East Africa

East Africa, also known as Eastern Africa or the East of Africa, is a region at the eastern edge of the Africa, African continent, distinguished by its unique geographical, historical, and cultural landscape. Defined in varying scopes, the regi ...

are discoveries of smelted iron and carbon in Nubia

Nubia (, Nobiin language, Nobiin: , ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the confluence of the Blue Nile, Blue and White Nile, White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), and the Cataracts of the Nile, first cataract ...

that date back between the 7th and 6th centuries BC, particularly in Meroe where there are known to have been ancient bloomeries that produced metal tools for the Nubians and Kushites and produced surplus for their economy.

Medieval Islamic world

Iron technology was further advanced by severalinventions in medieval Islam

The following is a list of inventions, discoveries and scientific advancements made in the medieval Muslim world, Islamic world, especially during the Islamic Golden Age,George Saliba (1994), ''A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories Du ...

, during the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of scientific, economic, and cultural flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 13th century.

This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign o ...

. By the 11th century, every province throughout the Muslim world

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is ...

had these industrial mills in operation, from Islamic Spain and North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

in the west to the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

and Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

in the east. There are also 10th-century references to cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content of more than 2% and silicon content around 1–3%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloying elements determine the form in which its car ...

, as well as archeological evidence of blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being supplied above atmospheric pressure.

In a ...

s being used in the Ayyubid

The Ayyubid dynasty (), also known as the Ayyubid Sultanate, was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultan of Egypt, Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate, Fatimid Caliphate of Egyp ...

and Mamluk

Mamluk or Mamaluk (; (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural); translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave") were non-Arab, ethnically diverse (mostly Turkic, Caucasian, Eastern and Southeastern European) enslaved mercenaries, slave-so ...

empires from the 11th century, thus suggesting a diffusion of Chinese metal technology to the Islamic world.

One of the most famous steels produced in the medieval Near East was Damascus steel

Damascus steel (Arabic: فولاذ دمشقي) refers to the high-carbon crucible steel of the blades of historical swords forged using the wootz process in the Near East, characterized by distinctive patterns of banding and mottling reminiscent ...

used for swordmaking, and mostly produced in Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

, Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

, in the period from 900 to 1750. This was produced using the crucible steel

Crucible steel is steel made by melting pig iron, cast iron, iron, and sometimes steel, often along with sand, glass, ashes, and other fluxes, in a crucible. Crucible steel was first developed in the middle of the 1st millennium BCE in Sout ...

method, based on the earlier Indian wootz steel

Wootz steel is a crucible steel characterized by a pattern of bands and high carbon content. These bands are formed by sheets of microscopic carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix in higher-carbon steel, or by ferrite and pea ...

. This process was adopted in the Middle East using locally produced steels. The exact process remains unknown, but it allowed carbide

In chemistry, a carbide usually describes a compound composed of carbon and a metal. In metallurgy, carbiding or carburizing is the process for producing carbide coatings on a metal piece.

Interstitial / Metallic carbides

The carbides of th ...

s to precipitate out as micro particles arranged in sheets or bands within the body of a blade. Carbides are far harder than the surrounding low carbon steel, so swordsmiths could produce an edge that cut hard materials with the precipitated carbides, while the bands of softer steel let the sword as a whole remain tough and flexible. A team of researchers based at the Technical University

An institute of technology (also referred to as technological university, technical university, university of technology, polytechnic university) is an institution of tertiary education that specializes in engineering, technology, applied science ...

of Dresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

that uses X-ray

An X-ray (also known in many languages as Röntgen radiation) is a form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength shorter than those of ultraviolet rays and longer than those of gamma rays. Roughly, X-rays have a wavelength ran ...

s and electron microscopy

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of electrons as a source of illumination. It uses electron optics that are analogous to the glass lenses of an optical light microscope to control the electron beam, for instance focusing i ...

to examine Damascus steel discovered the presence of cementite

Cementite (or iron carbide) is a compound of iron and carbon, more precisely an intermediate transition metal carbide with the formula Fe3C. By weight, it is 6.67% carbon and 93.3% iron. It has an orthorhombic crystal structure. It is a hard, b ...

nanowires

upright=1.2, Crystalline 2×2-atom tin selenide nanowire grown inside a single-wall carbon nanotube (tube diameter ≈1 nm).