Iris Wilkinson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

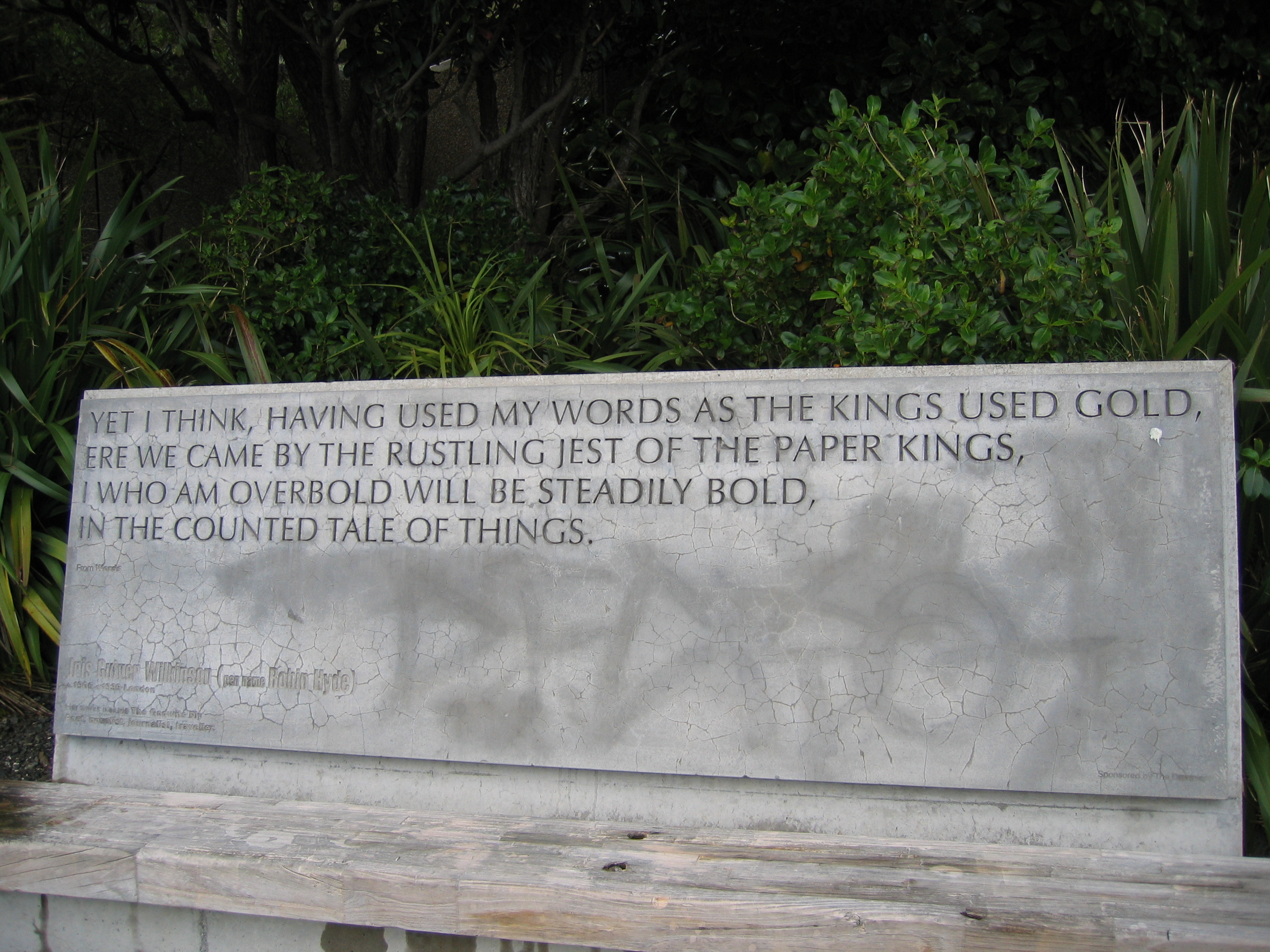

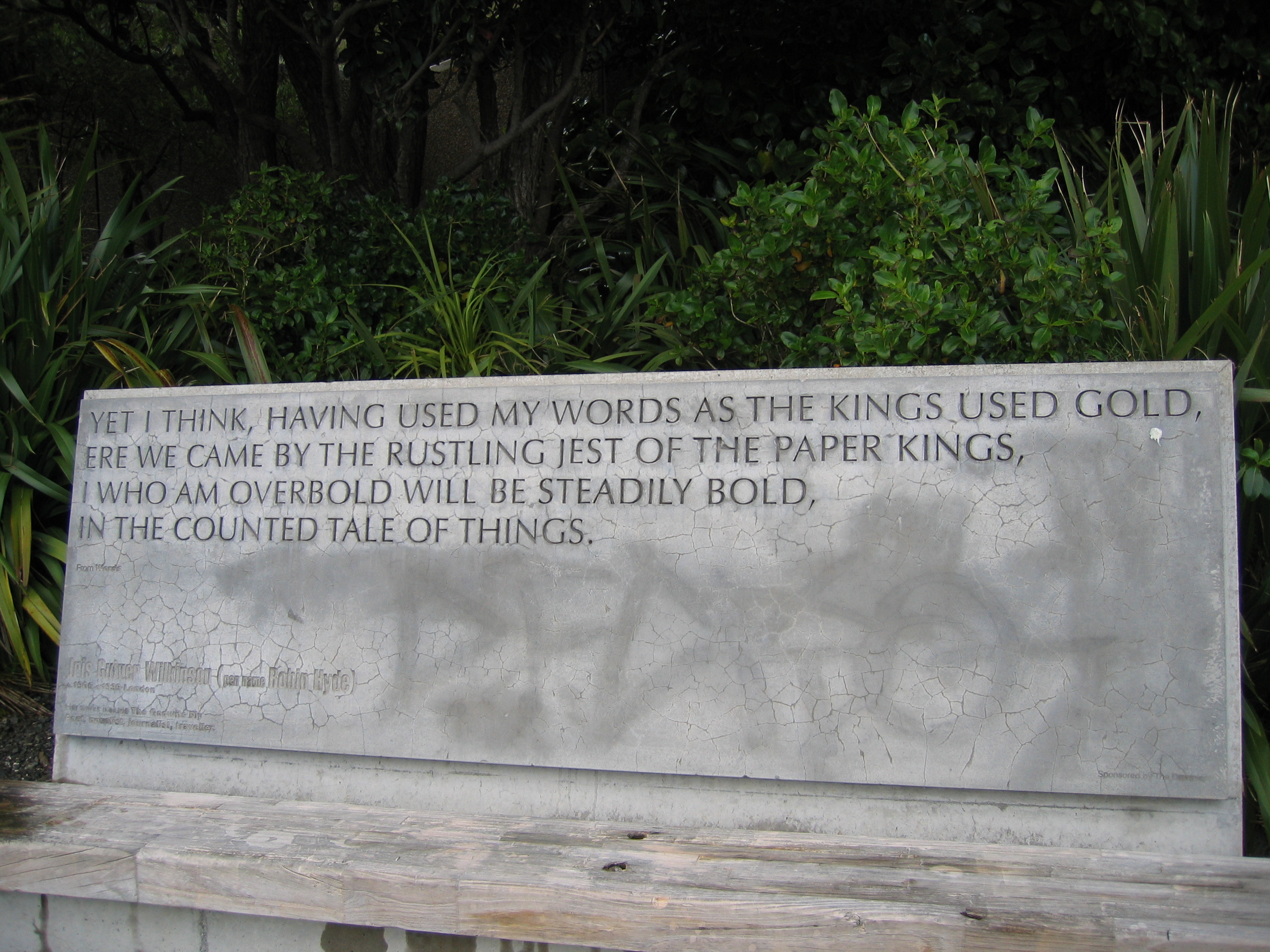

Robin Hyde, the pseudonym used by Iris Guiver Wilkinson (19 January 1906 – 23 August 1939), was a

Robin Hyde, the pseudonym used by Iris Guiver Wilkinson (19 January 1906 – 23 August 1939), was a

]

]

Profile from ''The Oxford Companion to New Zealand Literature''

at Read NZ Te Pou Muramura

New Zealand Electronic Poetry Centre: Online works and articles

* ttps://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-PopKowh-t1-body-d12.html Poems in ''Kowhai Gold'' (1930)

Te Ara: 1966 article from ''An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand''Robin Hyde in China

at the NZEPC, Auckland University

edited by

Derek Challis: Papers relating to Robin Hyde

(archival collection of Hyde's papers) at

Robin Hyde, the pseudonym used by Iris Guiver Wilkinson (19 January 1906 – 23 August 1939), was a

Robin Hyde, the pseudonym used by Iris Guiver Wilkinson (19 January 1906 – 23 August 1939), was a South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

n-born New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

poet, journalist and novelist.

Early life

Wilkinson was born inCape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

to an English father and an Australian mother, and was taken to Wellington

Wellington is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the third-largest city in New Zealand (second largest in the North Island ...

before her first birthday. She had her secondary education at Wellington Girls' College

Wellington Girls' College was founded in 1883 in Wellington, New Zealand. At that time it was called Wellington Girls' High School. Wellington Girls' College is a year 9 to 13 state secondary school, located in Thorndon in central Wellington. ...

, where she wrote poetry and short stories for the school magazine. After school she briefly attended Victoria University of Wellington

Victoria University of Wellington (), also known by its shorter names "VUW" or "Vic", is a public university, public research university in Wellington, New Zealand. It was established in 1897 by Act of New Zealand Parliament, Parliament, and w ...

. When she was 18, Hyde suffered a knee injury which required a hospital operation. Lameness and pain haunted her for the rest of her life. In 1925 she became a journalist for Wellington's ''Dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

'' newspaper, mostly writing for the women's pages. She continued to support herself through journalism throughout her life.

Later life

While working at the ''Dominion'', she had a brief love affair with Harry Sweetman, who left her to travel to England. In 1926, in Rotorua for a holiday and treatment for her tubercular knee, Hyde had an affair with Frederick de Mulford Hyde. When Hyde fell pregnant, Frederick paid for her to have the child inSydney, Australia

Sydney is the capital city of the state of New South Wales and the most populous city in Australia. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about 80 km (50 mi) from the Pacific Ocean ...

. Their son, Christopher Robin Hyde, was stillborn. She was to adopt the name 'Robin Hyde' as a 'nom de guerre', to preserve his memory. On her return to New Zealand in December 1926, she discovered that Frederick had married. Traumatised by the loss of her child, Hyde was hospitalised at Queen Mary Hospital in Hanmer Springs

Hanmer Springs is a small town in the Canterbury region of the South Island of New Zealand, known for its hot pools. The Māori name for Hanmer Springs is Te Whakatakanga o te Ngārahu o te ahi a Tamatea, which means "where the ashes of Tamate ...

and then cared for at the family home in Wellington, though only her mother knew of the pregnancy.

After a period of recovery, she began to write again, publishing poetry in several New Zealand newspapers in 1927. She was also engaged to write columns for the Christchurch

Christchurch (; ) is the largest city in the South Island and the List of cities in New Zealand, second-largest city by urban area population in New Zealand. Christchurch has an urban population of , and a metropolitan population of over hal ...

''Sun'', and the ''Mirror''. However, she became frustrated at the lack of creative input, as the papers merely wanted a social column. Social columns or women's pages were the main outlet available to women journalists during the period. These experiences contributed to her treatise on journalism in New Zealand, ''Journalese'', published in 1934.

In 1930, while working for the ''Wanganui Chronicle'', Hyde had an affair with the Marton-based journalist Harry Lawson Smith. Their son, Derek Arden Challis, was born in Picton that October. Lawson Smith was married, and his only relationship with Hyde and their son was to provide sporadic maintenance payments. In time Hyde's mother learned of Derek's existence, but her father was never told.

In 1929 Hyde published her first book of poetry, ''The Desolate Star''. Between 1935 and 1938 she published five novels: ''Passport to Hell'' (1936), ''Check To Your King'' (1936), ''Wednesday's Children'' (1937), ''Nor the Years Condemn'' (1938), and ''The Godwits Fly'' (1938). A manuscript of her unpublished autobiography was given to Auckland Libraries

Auckland Council Libraries, usually simplified to Auckland Libraries, is the public library system for the Auckland Region of New Zealand. It was created when the seven separate councils in the Auckland region merged in 2010. It is currently the ...

by Dr Gilbert Tothill.

]

]

Final years and death

In early 1938 she left New Zealand and travelled toHong Kong

Hong Kong)., Legally Hong Kong, China in international treaties and organizations. is a special administrative region of China. With 7.5 million residents in a territory, Hong Kong is the fourth most densely populated region in the wor ...

, arriving in early February. At the time, much of eastern China was under Japanese occupation, after the 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria

The Empire of Japan's Kwantung Army invaded the Manchuria region of the Republic of China on 18 September 1931, immediately following the Mukden incident, a false flag event staged by Japanese military personnel as a pretext to invade. At the ...

. Hyde was meant to travel to Kobe

Kobe ( ; , ), officially , is the capital city of Hyōgo Prefecture, Japan. With a population of around 1.5 million, Kobe is Japan's List of Japanese cities by population, seventh-largest city and the third-largest port city after Port of Toky ...

then Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( ; , ) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai and the capital of the Far Eastern Federal District of Russia. It is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, covering an area o ...

to take the trans-Siberian railway

The Trans-Siberian Railway, historically known as the Great Siberian Route and often shortened to Transsib, is a large railway system that connects European Russia to the Russian Far East. Spanning a length of over , it is the longest railway ...

to Europe. When the connection was delayed she made her way to Japanese-occupied Shanghai

Shanghai, Shanghainese: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: is a direct-administered municipality and the most populous urban area in China. The city is located on the Chinese shoreline on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the ...

, where she met fellow New Zealander Rewi Alley

Rewi Alley (known in China as 路易•艾黎, Lùyì Aìlí, 2 December 1897 – 27 December 1987) was a New Zealand-born writer and political activist. A member of the Chinese Communist Party, he dedicated 60 years of his life to the cause an ...

. Various peregrinations through China followed, including Canton

Canton may refer to:

Administrative divisions

* Canton (administrative division), territorial/administrative division in some countries

* Township (Canada), known as ''canton'' in Canadian French

Arts and entertainment

* Canton (band), an It ...

and Hankou

Hankou, alternately romanized as Hankow (), was one of the three towns (the other two were Wuchang and Hanyang) merged to become modern-day Wuhan city, the capital of the Hubei province, China. It stands north of the Han and Yangtze Rivers w ...

, the latter of which was the centre of Chinese resistance to Japanese occupation. She moved north to visit the battlefront and was in Xuzhou

Xuzhou ( zh, s=徐州), also known as Pengcheng () in ancient times, is a major city in northwestern Jiangsu province, China. The city, with a recorded population of 9,083,790 at the 2020 Chinese census, 2020 census (3,135,660 of which lived in ...

when Japanese forces took the city on 19 May.

Hyde attempted to flee the area by walking along the railway lines and was eventually escorted by Japanese officials to the port city of Qingdao

Qingdao, Mandarin: , (Qingdao Mandarin: t͡ɕʰiŋ˧˩ tɒ˥) is a prefecture-level city in the eastern Shandong Province of China. Located on China's Yellow Sea coast, Qingdao was long an important fortress. In 1897, the city was ceded to G ...

where she was handed over to British authorities. Shortly after she resumed her journey to England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

via sea, arriving in Southampton

Southampton is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. It is located approximately southwest of London, west of Portsmouth, and southeast of Salisbury. Southampton had a population of 253, ...

on 18 September 1938. She died by her own hand with an overdose of Benzedrine

Amphetamine (contracted from alpha- methylphenethylamine) is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant that is used in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), narcolepsy, and obesity; it is also used to treat binge e ...

at 1 Pembridge Square

Pembridge Square is a residential square in the Bayswater area of London close to nearby Notting Hill. It is located in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, just across the border from the City of Westminster to the east. It was laid out ...

, Kensington

Kensington is an area of London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, around west of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up by Kensingt ...

, a boarding house where she had been living. She was survived by a son, Derek Challis, and was buried in the Kensington New Cemetery, at Gunnersbury

Gunnersbury is an area of West London, England.

Toponymy

The name "Gunnersbury" originally meant "Gunner's (Gunnar's) fort", and is a combination of an old Scandinavian personal name + Middle English -''bury'', meaning, "fort", or "fortified ...

.

Many of Hyde's literary notes and personal papers were archived by the Alexander Turnbull Library

The National Library of New Zealand () is charged with the obligation to "enrich the cultural and economic life of New Zealand and its interchanges with other nations" (National Library of New Zealand (Te Puna Mātauranga) Act 2003). Under the ...

and the Special Collections at the University of Auckland

The University of Auckland (; Māori: ''Waipapa Taumata Rau'') is a public research university based in Auckland, New Zealand. The institution was established in 1883 as a constituent college of the University of New Zealand. Initially loc ...

. In 2020, these archival papers were inscribed on the UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

Memory of the World Aotearoa New Zealand Ngā Mahara o te Ao

Memory of the World Aotearoa New Zealand Ngā Mahara o te Ao Register is a national register of New Zealand's documentary heritage as part of the Memory of the World Programme, maintained by UNESCO Aotearoa New Zealand Memory of the World Trust. ...

register.

References

External links

*Profile from ''The Oxford Companion to New Zealand Literature''

at Read NZ Te Pou Muramura

New Zealand Electronic Poetry Centre: Online works and articles

* ttps://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-PopKowh-t1-body-d12.html Poems in ''Kowhai Gold'' (1930)

Te Ara: 1966 article from ''An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand''

at the NZEPC, Auckland University

edited by

Nikki Hessell

Nicola Anne Hessell is a New Zealand academic, and is a full professor at Victoria University of Wellington, specialising in British Romantic literature, and the intersection between Romantic literature and indigeneity.

Academic career

Hessell ...

Derek Challis: Papers relating to Robin Hyde

(archival collection of Hyde's papers) at

Alexander Turnbull Library

The National Library of New Zealand () is charged with the obligation to "enrich the cultural and economic life of New Zealand and its interchanges with other nations" (National Library of New Zealand (Te Puna Mātauranga) Act 2003). Under the ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hyde, Robin

1906 births

1939 deaths

1939 suicides

20th-century New Zealand novelists

20th-century New Zealand poets

20th-century New Zealand journalists

20th-century New Zealand women writers

New Zealand women poets

New Zealand women novelists

New Zealand people of English descent

South African emigrants to New Zealand

People educated at Wellington Girls' College

Victoria University of Wellington alumni

New Zealand autobiographers

Women autobiographers

Suicides in Kensington

Drug-related suicides in England