Inventor Of Radio on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The invention of radio communication was preceded by many decades of establishing theoretical underpinnings, discovery and experimental investigation of

The invention of radio communication was preceded by many decades of establishing theoretical underpinnings, discovery and experimental investigation of

Page 831

/ref> The patented system claimed to utilize In the United States,

In the United States,

''Alexander Graham Bell: Giving Voice To The World''

Sterling Biographies, New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., pp. 76–78. . In the early 1890s

''The Principles of Electric Wave Telegraphy''

London: New York and Co. (cf., Joseph Henry, in the United States, between 1842 and 1850, explored many of the puzzling facts connected with this subject, and only obtained a clue to the anomalies when he realized that the discharge of a condenser through a low resistance circuit is oscillatory in nature. Amongst other things, Henry noticed the power of condenser discharges to induce secondary currents which could magnetize steel needles even when a great distance separated the primary and secondary circuits.)Se

''The Scientific Writings of Joseph Henry''

vol. i. pp. 203, 20:-i; als

"Analysis of the Dynamic Phenomena of the Leyden Jar"

''Proceedings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science'', 1850, vol. iv. pp. 377–78, Joseph Henry. The effect of the oscillatory discharge on a magnetized needle is summarized in this review.Ames, J. S., Henry, J., & Faraday, M. (1900)

''The Discovery of Induced Electric Currents''

New York: American book. (cf. Page 107: "On moving to Princeton, in 1832, enry ..investigated also the discharge of a Leyden jar, proved that it was oscillatory in character, and showed that its inductive effects could be detected at a distance of two hundred feet, thus clearly establishing the existence of electro-magnetic waves.") He was the first (1838–42) to produce high frequency AC electrical oscillations, and to point out and experimentally demonstrate that the discharge of a capacitor under certain conditions is oscillatory, or, as he puts it, consists "''of a principal discharge in one direction and then several reflex actions backward and forward, each more feeble than the preceding until equilibrium is attained''". This view was also later adopted by

"Wireless Telephony"

''Transactions of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers'' (volume 27, part 1), June 29, 1908, pp. 553–630

When German physicist

When German physicist  Hertz was able to have some control over the frequencies of his radiated waves by altering the

Hertz was able to have some control over the frequencies of his radiated waves by altering the

Towards the end of 1875, while experimenting with the

Towards the end of 1875, while experimenting with the

"Notes"

(May 5, 1899, p. 35)

"Prof. D. E. Hughes's Researches in Wireless Telegraphy"

by J. J. Fahie (May 5, 1899, pp. 40–41)

"The National Telephone Company's Staff Dinner"

(Hughes remarks), (May 12, 1899, pp. 93–94) He developed an improved detector to pick up this unknown "extra current" based on his new microphone design (similar to later detectors known as

"Some Possibilities of Electricity"

''The Fortnightly Review'', pp. 173–81

Oliver Lodge: Almost the Father of Radio

, page 4, from Antique Wireless Before he could present his own findings he learned of Hertz' series of proofs on the same subject. On 1 June 1894, at a meeting of the

Emerson, National Radio Astronomy Observatory website

/ref> However he was not interested in researching the use of radio waves for communication.

In 1894–95 the Russian physicist Alexander Stepanovich Popov conducted experiments developing a

In 1894–95 the Russian physicist Alexander Stepanovich Popov conducted experiments developing a

''Proceedings'' (volume 14: 1893–95), Royal Institution of Great Britain, pp. 321–49 Marconi is said to have read, while on vacation in 1894, about the experiments that Hertz did in the 1880s. Marconi also read about Tesla's work. It was at this time that Marconi began to understand that radio waves could be used for wireless communications. Marconi's early apparatus was a development of Hertz's laboratory apparatus into a system designed for communications purposes. At first Marconi used a transmitter to ring a bell in a receiver in his attic laboratory. He then moved his experiments out-of-doors on the family estate near

''Improvements in Transmitting Electrical Impulses and Signals and in Apparatus There-for''. The complete specification was filed 2 March 1897. This was Marconi's initial patent for the radio, though it used various earlier techniques of various other experimenters and resembled the instrument demonstrated by others (including Popov). During this time spark-gap wireless telegraphy was widely researched. In July, 1896, Marconi got his invention and new method of telegraphy to the attention of Preece, then engineer-in-chief to the The Marconi Company Ltd. was founded by Marconi in 1897, known as the Wireless Telegraph Trading Signal Company. Also in 1897, Marconi established the radio station at Niton, Isle of Wight, England. Marconi's wireless telegraphy was inspected by the Post Office Telegraph authorities; they made a series of experiments with Marconi's system of telegraphy without connecting wires, in the

The Marconi Company Ltd. was founded by Marconi in 1897, known as the Wireless Telegraph Trading Signal Company. Also in 1897, Marconi established the radio station at Niton, Isle of Wight, England. Marconi's wireless telegraphy was inspected by the Post Office Telegraph authorities; they made a series of experiments with Marconi's system of telegraphy without connecting wires, in the

"Wireless Telegraphy"

by G. Marconi, ''Journal of the Institution of Electrical Engineers'', 1899 (volume 28), pp. 273–91) The Haven Hotel station and Wireless Telegraph Mast was where much of Marconi's research work on wireless telegraphy was carried out after 1898.Fleming (1908

pp. 431–32

/ref> In 1899, he transmitted messages across the In 1901, Marconi claimed to have received daytime transatlantic radio frequency signals at a wavelength of 366 metres (820 kHz).Bradford, Henry M.

In 1901, Marconi claimed to have received daytime transatlantic radio frequency signals at a wavelength of 366 metres (820 kHz).Bradford, Henry M.

"Did Marconi Receive Transatlantic Radio Signals in 1901? – Part 1"

Antique Wireless Association (antiquewireless.org)Bradford, Henry M.

"Did Marconi Receive Transatlantic Radio Signals in 1901? Part 2 (conclusion): The Trans-Atlantic Experiments

Antique Wireless Association (antiquewireless.org) Marconi established a wireless transmitting station at Marconi House, Rosslare Strand, Co. Wexford in 1901 to act as a link between Poldhu in Cornwall and Clifden in Co. Galway. His announcement on 12 December 1901, using a kite-supported antenna for reception, stated that the message was received at Signal Hill in St John's,

"Fessenden and Marconi; Their Differing Technologies and Transatlantic Experiments During the First Decade of this Century"

International Conference on 100 Years of Radio, September 5–7, 1995. Retrieved 2018-02-05. There are various science historians, such as Belrose and Bradford, who have cast doubt that the Atlantic was bridged in 1901, but other science historians have taken the position that this was the first transatlantic radio transmission. Critics have claimed that it is more likely that Marconi received stray atmospheric

p. 761

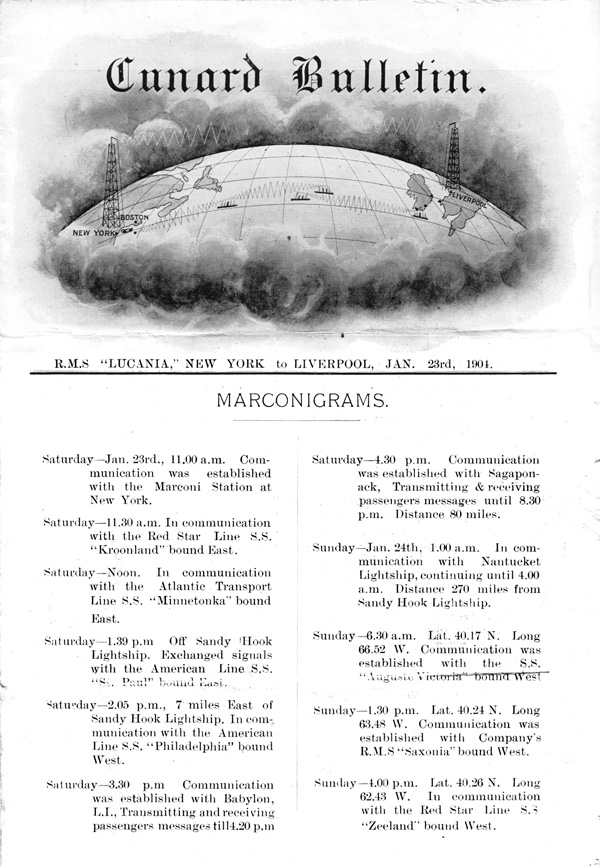

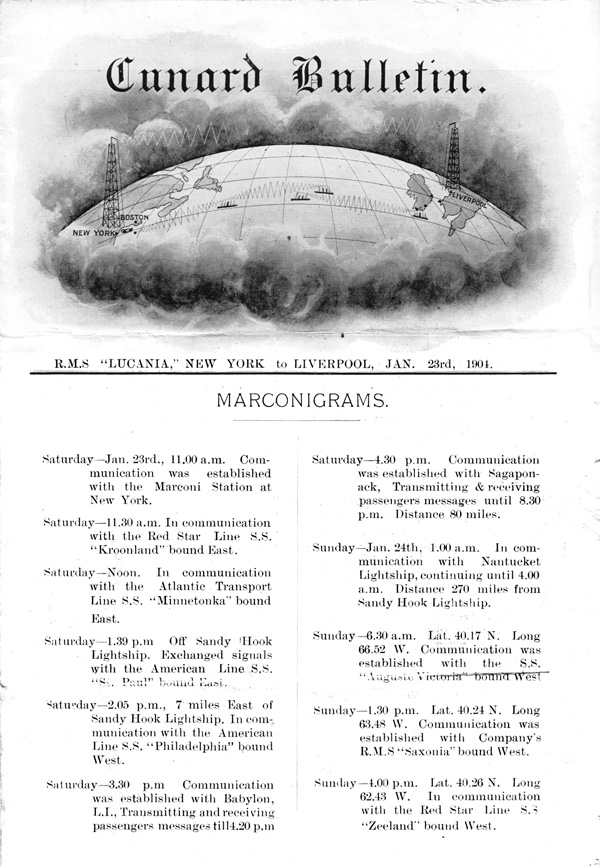

/ref> was developed further by Marconi and was successfully used in his early transatlantic work (1902) and in many of the smaller stations for a number of years. In 1902, a Marconi station was established in the village of In 1904, Marconi inaugurated an ocean daily newspaper, the '' Cunard Daily Bulletin'', on the . At the start, passing events were printed in a little pamphlet of four pages called the ''Cunard Bulletin''. The title would read Cunard Daily Bulletin, with subheads for "'' Marconigrams Direct to the Ship''." All the passenger ships of the Cunard Company were fitted with Marconi's system of wireless telegraphy, by means of which constant communication was kept up, either with other ships or with land stations on the eastern or western hemisphere. The , in October 1903, with Marconi on board, was the first vessel to hold communications with both sides of the Atlantic. The ''Cunard Daily Bulletin'', a 32-page illustrated paper published on board these ships, recorded news received by wireless telegraphy, and was the first ocean newspaper. In August 1903, an agreement was made with the British Government by which the Cunard Co. were to build two

In 1904, Marconi inaugurated an ocean daily newspaper, the '' Cunard Daily Bulletin'', on the . At the start, passing events were printed in a little pamphlet of four pages called the ''Cunard Bulletin''. The title would read Cunard Daily Bulletin, with subheads for "'' Marconigrams Direct to the Ship''." All the passenger ships of the Cunard Company were fitted with Marconi's system of wireless telegraphy, by means of which constant communication was kept up, either with other ships or with land stations on the eastern or western hemisphere. The , in October 1903, with Marconi on board, was the first vessel to hold communications with both sides of the Atlantic. The ''Cunard Daily Bulletin'', a 32-page illustrated paper published on board these ships, recorded news received by wireless telegraphy, and was the first ocean newspaper. In August 1903, an agreement was made with the British Government by which the Cunard Co. were to build two

"Wireless telegraphy"

''Encyclopaedia of Ships and Shipping'' edited by Herbert B. Mason. The Shipping Encyclopaedia, 1908, pp. 686–88.) and building the first stations for the British shortwave service, have marked his place in history. In June and July 1923, Marconi's

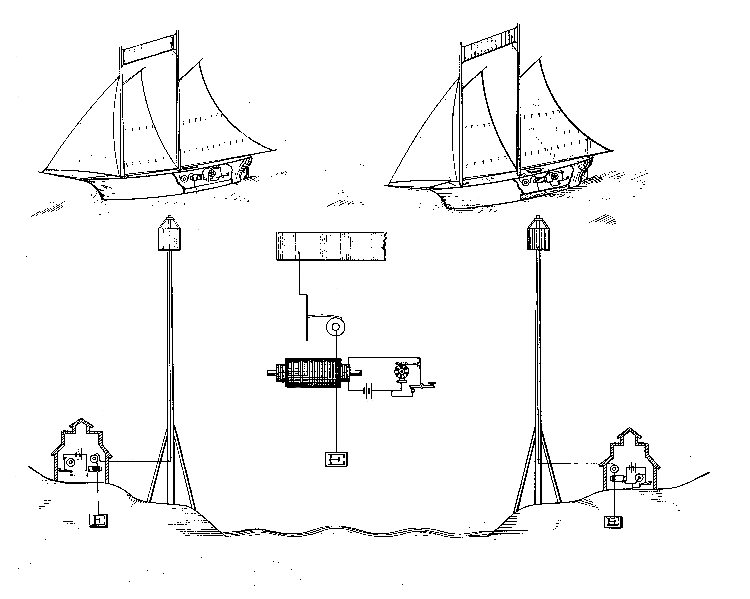

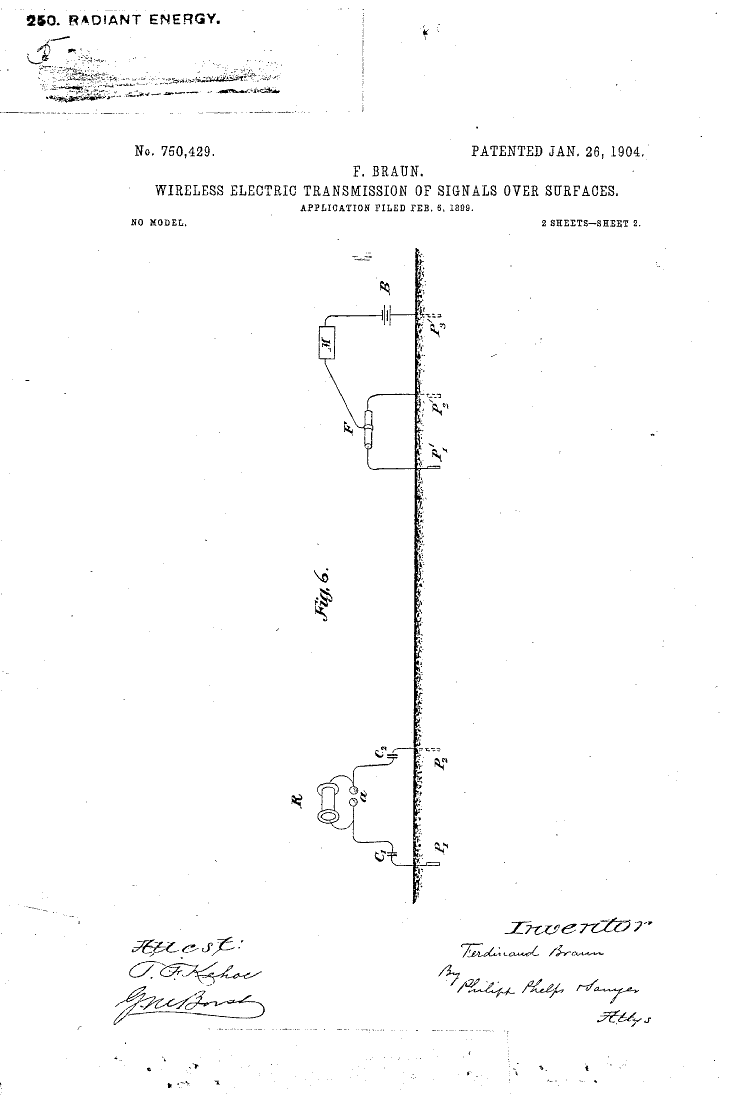

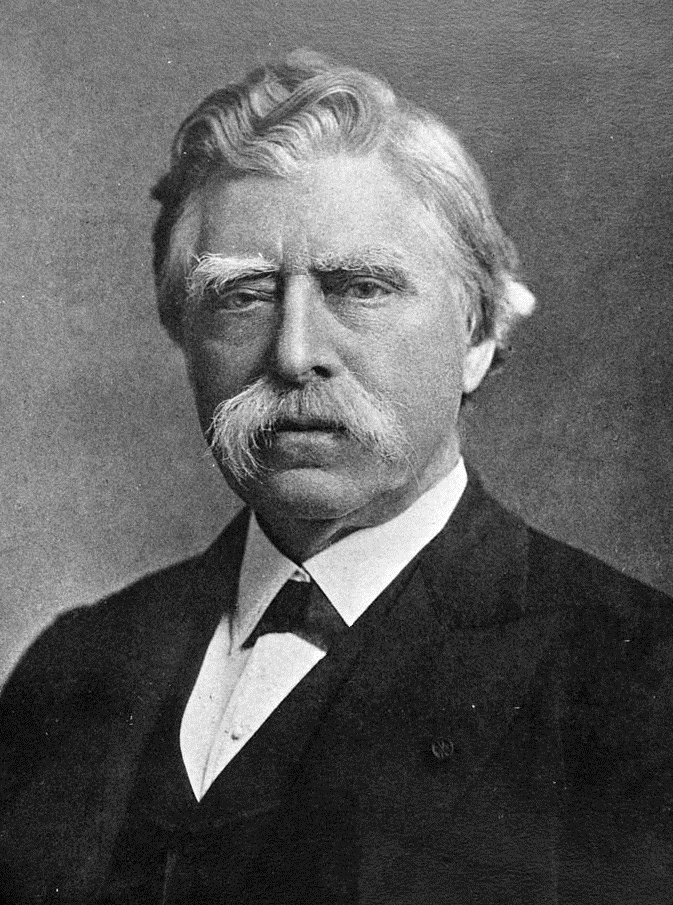

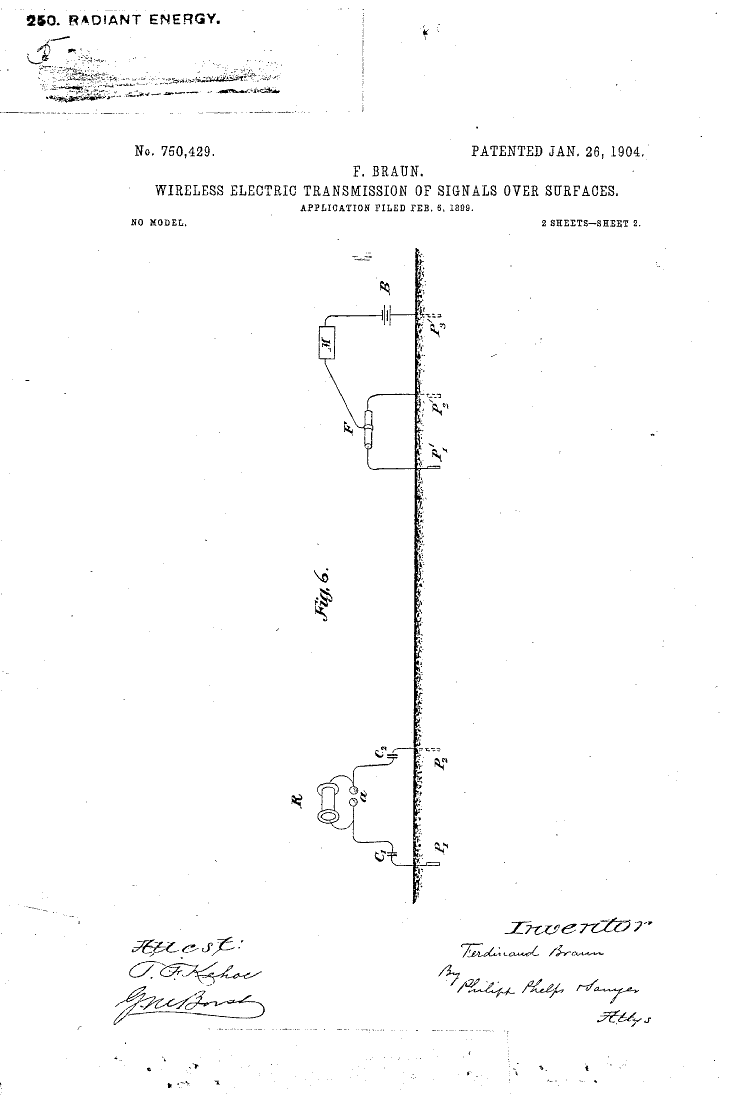

Ferdinand Braun's major contributions were the introduction of a closed tuned circuit in the generating part of the transmitter, and its separation from the radiating part (the antenna) by means of inductive coupling, and later on the usage of crystals for receiving purposes. Braun experimented at first at the University of Strasbourg. Braun had written extensively on wireless subjects and was well known through his many contributions to the Electrician and other scientific journals."Dr. Braun, Famous German Scientist, Dead"

Ferdinand Braun's major contributions were the introduction of a closed tuned circuit in the generating part of the transmitter, and its separation from the radiating part (the antenna) by means of inductive coupling, and later on the usage of crystals for receiving purposes. Braun experimented at first at the University of Strasbourg. Braun had written extensively on wireless subjects and was well known through his many contributions to the Electrician and other scientific journals."Dr. Braun, Famous German Scientist, Dead"

''The Wireless Age'' (volume 5), June 1918, pp. 709–10 In 1899, he would apply for the patents, ''Electro telegraphy by means of condensers and induction coils'' and ''Wireless electro transmission of signals over surfaces''. Pioneers working on wireless devices eventually came to a limit of distance they could cover. Connecting the antenna directly to the spark gap produced only a heavily damped pulse train. There were only a few cycles before oscillations ceased. Braun's circuit afforded a much longer sustained oscillation because the energy encountered less loss swinging between coil and Leyden Jars. Also, by means of inductive antenna coupling the radiator was matched to the generator. In spring 1899 Braun, accompanied by his colleagues Cantor and Zenneck, went to

p. 520

/ref> Stone has had issued to him a large number of patents embracing a method for impressing oscillations on a radiator system and emitting the energy in the form of waves of predetermined length whatever may be the electrical dimensions of the oscillator.Collins, A. Frederick (1905) ''Wireless Telegraphy: Its History, Theory and Practice''

p. 164

/ref> On February 8, 1900, he filed for a selective system in . In this system, two simple circuits are associated inductively, each having an independent degree of freedom, and in which the restoration of electric oscillations to zero potential the currents are superimposed, giving rise to compound harmonic currents which permit the resonator system to be syntonized with precision to the oscillator. Stone's system, as stated in , developed free or unguided simple harmonic electromagnetic signal waves of a definite frequency to the exclusion of the energy of signal waves of other frequencies, and an elevated conductor and means for developing therein forced simple electric vibrations of corresponding frequency.Maver (1904

p. 126

/ref> In these patents Stone devised a multiple inductive oscillation circuit with the object of forcing on the antenna circuit a single oscillation of definite frequency. In the system for receiving the energy of free or unguided simple harmonic electromagnetic signal waves of a definite frequency to the exclusion of the energy of signal waves of other frequencies, he claimed an elevated conductor and a resonant circuit associated with said conductor and attuned to the frequency of the waves, the energy of which is to be received. A coherer made on what is called the ''Stone system''Stanley, Rupert (1919) ''Text-book on Wireless Telegraphy'', Longmans, Green

p. 300

/ref> was employed in some of the portable wireless outfits of the

p. 77

/ref> They also noted that when two stations were transmitting simultaneously both would be received and that the system had the potential to affect the compass. They reported ranges from for large ships with tall masts () to for smaller vessels. The board recommended that the system was given a trial by the United States Navy.

pp. 66–71

/ref> Fessenden evolved the By the summer of 1906, a machine producing 50 kilohertz was installed at the Brant Rock station, and in the fall of 1906, what was called an electric alternating dynamo was working regularly at 75 kilohertz, with an output of 0.5 kW. Fessenden used this for wireless telephoning to

By the summer of 1906, a machine producing 50 kilohertz was installed at the Brant Rock station, and in the fall of 1906, what was called an electric alternating dynamo was working regularly at 75 kilohertz, with an output of 0.5 kW. Fessenden used this for wireless telephoning to

"De Forest Radio Telephone and Telegraph Company"

''America's Maritime Progress'', New York: New York marine news Co., p. 254. De Forest made the ''Audion tube'' from a

ImageSize = width:777 height:600

DateFormat = YYYY

Period = from:1860 till:1910

PlotArea = width:716 height:550 left:40 bottom:20

TimeAxis = orientation:vertical order:reverse

ScaleMajor = unit:year increment:10 start:1860

ScaleMinor = unit:year increment:1 start:1860

PlotData=

at:1864 fontsize:S text:"Maxwell predicts electromagnetic (EM) waves.

at:1879 fontsize:S text:"Hughes demonstrates transmission of signals over 460m."

at:1887 fontsize:S text:"Hertz publishes research experiments confirming Maxwell's theory in the journal Annalen der Physik."

at:1890 fontsize:S text:"Branly demonstrates the coherer as a radio wave detector."

at:1892 fontsize:S text:"William Crookes suggests Hertzian waves could be used in wireless telegraphy"

at:1893 fontsize:S text:"Tesla demonstrates his wireless power techniques at St. Louis, Missouri."

at:1894 fontsize:S text:"Bose ignited gunpowder and rang a bell at a distance in Calcutta."

at:1895 fontsize:S text:"Popov presents his radio receiver to the Russian Physical and Chemical Society. Marconi transmits radio signals for about 1.5 miles (2.4 km)"

at:1897 fontsize:S text:"Marconi sends wireless signals from Salisbury Plain to Bath, a distance of 34 miles (55 km)."

at:1899 fontsize:S text:"Braun transmits 42 km. Popov transmits 130 miles."

at:1900 fontsize:S text:"Fessenden makes the first audio radio transmission."

at:1901 fontsize:S text:"Marconi reports transatlantic transmission."

at:1902 fontsize:S text:"Marconi station in Canada became the first radio message to cross the Atlantic from North America."

at:1906 fontsize:S text:"Fessenden transmits audio (radio telephony) over a distance of approximately 11 miles (18 km)."

at:1909 fontsize:S text:"Braun and Marconi receive Nobel Prize in physics, 'in recognition of their contributions to the development of wireless telegraphy'."

Radio engineering principles

New York: McGraw-Hill book company; tc., etc.* Rockman, H. B. (2004)

Intellectual property law for engineers and scientists

New York .a.: IEEE Press

Marconi Wireless Tel. Co. v. United States

320 U.S. 1 (U.S. 1943)", 320 U.S. 1, 63 S. Ct. 1393, 87 L. Ed. 1731 Argued April 9,12, 1943. Decided June 21, 1943. ;Books and articles:''listed by date, earliest first''

Telegraphing across space, Electric wave method

The Electrical engineer. (1884). London: Biggs & Co. (ed., the article is broke up, it begins on p. 466 and continues o

p. 493

) * Fahie, J. J. (1900)

A history of wireless telegraphy, 1838–1899: including some bare-wire proposals for subaqueous telegraphs

Edinburgh: W. Blackwood and Sons. * Thompson, S. P., Homans, J. E., & Tesla, N. (1903). Polyphase electric currents and alternate-current motors.

Wireless Telegraphy

. The library of electrical science, v. 6. New York: P.F. Collier & Son. * Sewall, C. H. (1904)

Wireless telegraphy: its origins, development, inventions, and apparatus

New York: D. Van Nostrand. * Trevert, E. (1904)

The A.B.C. of wireless telegraphy; a plain treatise on Hertzian wave signaling; embracing theory, methods of operation, and how to build various pieces of the apparatus employed

Lynn, Mass: Bubier Pub. * Collins, A. F. (1905)

Wireless telegraphy; its history, theory and practice

New York: McGraw Pub. * Mazzotto, D., & Bottone, S. R. (1906)

Wireless telegraphy and telephony

London: Whittaker & Co. * Erskine-Murray, J. (1907)

A handbook of wireless telegraphy: Its theory and practice, for the use of electrical engineers, students, and operators

London: Crosby Lockwood and Son. (ed., also available in th

Van Nostrand (1909)

version). * Murray, J. E. (1907)

A handbook of wireless telegraphy

New York: D. Van Nostrand Co.; tc.* Simmons, H. H. (1908).

Wireless telegraphy

Outlines of electrical engineering

London: Cassell and Co. * Fleming, J. A. (1908)

The principles of electric wave telegraphy

London: New York and Co. * Twining, H. L. V., & Dubilier, W. (1909)

Wireless telegraphy and high frequency electricity; a manual containing detailed information for the construction of transformers, wireless telegraph and high frequency apparatus, with chapters on their theory and operation

Los Angeles, Cal: The author. * Bottone, S. R. (1910)

Wireless telegraphy and Hertzian waves

London: Whittaker & Co. * Bishop, L. W. (1911)

The wireless operators' pocketbook of information and diagrams.

Lynn, Mass: Bubier Pub. Co.; tc., etc. * Massie, W. W., & Underhill, C. R. (1911)

Wireless telegraphy and telephony popularly explained

New York: D. Van Nostrand. * Ashley, C. G., & Hayward, C. B. (1912)

Wireless telegraphy and wireless telephony

an understandable presentation of the science of wireless transmission of intelligence. Chicago: American School of Correspondence. * Stanley, R. (1914)

Text book on wireless telegraphy

London: Longmans, Green. * Thompson, S. P. (1915)

Elementary lessons in electricity and magnetism

New York: Macmillan * Bucher, E. E. (1917)

Practical wireless telegraphy

A complete text book for students of radio communication. New York: Wireless Press, Inc. * American Institute of Electrical Engineers. (1919)

Transactions of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers

New York: American Institute of Electrical Engineers. (ed., Contains ''Radio Telephony'' — By E. B. Craft and E. H. Colpitts (Illustrated)

Page 305

* Stanley, R. (1919)

Text-book on wireless telegraphy

London: Longmans, Green. ;Encyclopedias * Chisholm, H. (1910). The encyclopædia britannica: A dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information. Cambridge, Eng: At the University press. "Telegraph",

Part II – Wireless Telegraphy

. * American Technical Society. (1914). Cyclopedia of applied electricity: A general reference work on direct-current generators and motors, storage batteries, electrochemistry, welding, electric wiring, meters, electric light transmission, alternating-current machinery, telegraphy, etc

Volume 7Wireless Telegraphy and Telephony By C. G. Ashley Page 147

Chicago: American technical society. * Colby, F. M., Williams, T., & Wade, H. T. (1922).

Wireless Telegraphy

The New international encyclopaedia

New York: Dodd, Mead and Co. *

Wireless telegraphy

The Encyclopædia Britannica

(1922). London: Encyclopædia Britannica. ;Gutenberg project * Jenkins, C. F. (1925).

Vision by radio, radio photographs, radio photograms

'. Washington, D.C.: National Capitol Press.

''The New Physics and Its Evolution''. Chapter VII : A Chapter in the History of Science: Wireless telegraphy

by Lucien Poincaré, eBook #15207, released February 28, 2005. ;Websites

Tesla society

Early Radio History

* Howeth, Captain H.S

''History of Communications – Electronics in the United States Navy''

published 1963, GPO, 657 pages. Free online public domain US government published book. * Wunsch, A.D.,

" ''Antenna'', Volume 11 No. 1, November 1998, Society for the History of Technology * Katz, Randy H., "

'". History of Communications Infrastructures

* {{Telecommunications Discovery and invention controversies History of electronic engineering

radio wave

Radio waves (formerly called Hertzian waves) are a type of electromagnetic radiation with the lowest frequencies and the longest wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum, typically with frequencies below 300 gigahertz (GHz) and wavelengths g ...

s, and engineering and technical developments related to their transmission and detection. These developments allowed Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, 1st Marquess of Marconi ( ; ; 25 April 1874 – 20 July 1937) was an Italian electrical engineer, inventor, and politician known for his creation of a practical radio wave-based Wireless telegraphy, wireless tel ...

to turn radio waves into a wireless communication

Wireless communication (or just wireless, when the context allows) is the transfer of information (''telecommunication'') between two or more points without the use of an electrical conductor, optical fiber or other continuous guided med ...

system.

The idea that the wires needed for electrical telegraph

Electrical telegraphy is point-to-point distance communicating via sending electric signals over wire, a system primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most wid ...

could be eliminated, creating a wireless telegraph, had been around for a while before the establishment of radio-based communication. Inventors attempted to build systems based on electric conduction, electromagnetic induction

Electromagnetic or magnetic induction is the production of an electromotive force, electromotive force (emf) across an electrical conductor in a changing magnetic field.

Michael Faraday is generally credited with the discovery of induction in 1 ...

, or on other theoretical ideas. Several inventors/experimenters came across the phenomenon of radio waves before its existence was proven; it was written off as electromagnetic induction

Electromagnetic or magnetic induction is the production of an electromotive force, electromotive force (emf) across an electrical conductor in a changing magnetic field.

Michael Faraday is generally credited with the discovery of induction in 1 ...

at the time.

The discovery of electromagnetic waves

In physics, electromagnetic radiation (EMR) is a self-propagating wave of the electromagnetic field that carries momentum and radiant energy through space. It encompasses a broad spectrum, classified by frequency or its inverse, wavelength, ran ...

, including radio waves

Radio waves (formerly called Hertzian waves) are a type of electromagnetic radiation with the lowest frequencies and the longest wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum, typically with frequencies below 300 gigahertz (GHz) and wavelengths ...

, by Heinrich Rudolf Hertz

Heinrich Rudolf Hertz (; ; 22 February 1857 – 1 January 1894) was a German physicist who first conclusively proved the existence of the electromagnetic waves predicted by James Clerk Maxwell's equations of electromagnetism.

Biography

Heinric ...

in the 1880s came after theoretical development on the connection between electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter possessing an electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by Maxwel ...

and magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that occur through a magnetic field, which allows objects to attract or repel each other. Because both electric currents and magnetic moments of elementary particles give rise to a magnetic field, ...

that started in the early 1800s. This work culminated in a theory of electromagnetic radiation

In physics, electromagnetic radiation (EMR) is a self-propagating wave of the electromagnetic field that carries momentum and radiant energy through space. It encompasses a broad spectrum, classified by frequency or its inverse, wavelength ...

developed by James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish physicist and mathematician who was responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism an ...

by 1873, which Hertz demonstrated experimentally. Hertz considered electromagnetic waves to be of little practical value. Other experimenters, such as Oliver Lodge

Sir Oliver Joseph Lodge (12 June 1851 – 22 August 1940) was an English physicist whose investigations into electromagnetic radiation contributed to the development of Radio, radio communication. He identified electromagnetic radiation indepe ...

and Jagadish Chandra Bose

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose (; ; 30 November 1858 – 23 November 1937) was a polymath with interests in biology, physics and writing science fiction. He was a pioneer in the investigation of radio microwave optics, made significant contributions ...

, explored the physical properties of electromagnetic waves, and they developed electric devices and methods to improve the transmission and detection of electromagnetic waves. But they did not apparently see the value in developing a communication system based on electromagnetic waves.

In the mid-1890s, building on techniques physicists were using to study electromagnetic waves, Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, 1st Marquess of Marconi ( ; ; 25 April 1874 – 20 July 1937) was an Italian electrical engineer, inventor, and politician known for his creation of a practical radio wave-based Wireless telegraphy, wireless tel ...

developed the first apparatus for long-distance radio communication. On 23 December 1900, the Canadian-born American inventor Reginald A. Fessenden became the first person to send audio (wireless telephony

Wireless communication (or just wireless, when the context allows) is the transfer of information (''telecommunication'') between two or more points without the use of an electrical conductor, optical fiber or other continuous guided med ...

) by means of electromagnetic waves, successfully transmitting over a distance of about a mile (1.6 kilometers,) and six years later on Christmas Eve

Christmas Eve is the evening or entire day before Christmas, the festival commemorating nativity of Jesus, the birth of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus. Christmas Day is observance of Christmas by country, observed around the world, and Christma ...

1906 he became the first person to make a public wireless broadcast.

By 1910, these various wireless systems had come to be called "radio".

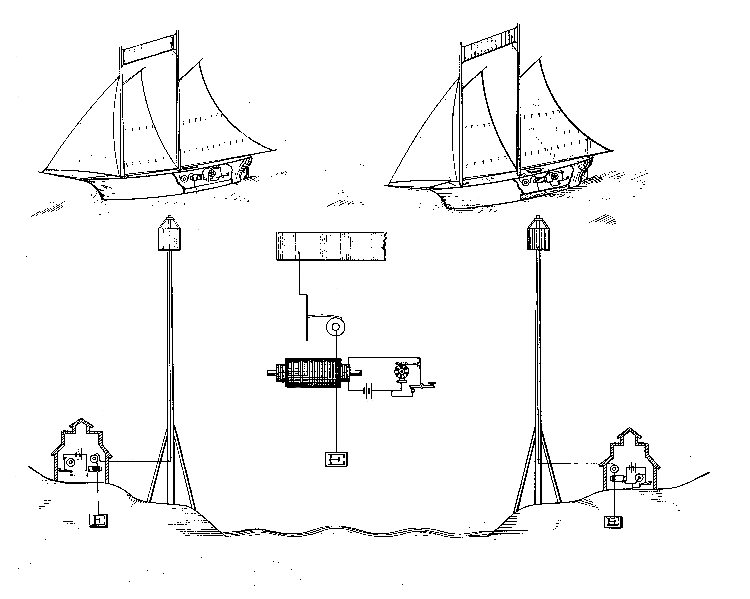

Wireless communication theories and methods previous to radio

Before the discovery of electromagnetic waves and the development of radio communication, there were many wireless telegraph systems proposed and tested. In April 1872 William Henry Ward received for a wireless telegraphy system where he theorized that convection currents in the atmosphere could carry signals like a telegraph wire. A few months after Ward received his patent, Mahlon Loomis ofWest Virginia

West Virginia is a mountainous U.S. state, state in the Southern United States, Southern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.The United States Census Bureau, Census Bureau and the Association of American ...

received for a similar "wireless telegraph" in July 1872.Sterling, Christopher H. (ed.) (2003) ''Encyclopedia of Radio'' ( Volume 1Page 831

/ref> The patented system claimed to utilize

atmospheric electricity

Atmospheric electricity describes the electrical charges in the Earth's atmosphere (or that of another planet). The movement of charge between the Earth's surface, the atmosphere, and the ionosphere is known as the global atmospheric electrica ...

to eliminate the overhead wire used by the existing telegraph systems. It did not contain diagrams or specific methods and it did not refer to or incorporate any known scientific theory.

In the United States,

In the United States, Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February11, 1847October18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventions, ...

, in the mid-1880s, patented an electromagnetic induction system he called "grasshopper telegraphy", which allowed telegraphic signals to jump the short distance between a running train and telegraph wires running parallel to the tracks. In the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, William Preece was able to develop an electromagnetic induction telegraph system that, with antenna wires many kilometers long, could transmit across gaps of about . Inventor Nathan Stubblefield, between 1885 and 1892, also worked on an induction transmission system.

A form of wireless telephony

Wireless communication (or just wireless, when the context allows) is the transfer of information (''telecommunication'') between two or more points without the use of an electrical conductor, optical fiber or other continuous guided med ...

is recorded in four patents for the photophone

The photophone is a telecommunications device that allows transmission of speech on a beam of light. It was invented jointly by Alexander Graham Bell and his assistant Charles Sumner Tainter on February 19, 1880, at Bell's laboratory at 1325 ...

, invented jointly by Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell (; born Alexander Bell; March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922) was a Scottish-born Canadian Americans, Canadian-American inventor, scientist, and engineer who is credited with patenting the first practical telephone. He als ...

and Charles Sumner Tainter

Charles Sumner Tainter (April 25, 1854 – April 20, 1940) was an American scientific instrument maker, engineer and inventor, best known for his collaborations with Alexander Graham Bell, Chichester Bell, Alexander's father-in-law Gardiner Hubba ...

in 1880. The photophone allowed for the transmission of sound on a beam of light

Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be visual perception, perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400– ...

, and on 3 June 1880, Bell and Tainter transmitted the world's first wireless telephone message on their newly invented form of light telecommunication

Telecommunication, often used in its plural form or abbreviated as telecom, is the transmission of information over a distance using electronic means, typically through cables, radio waves, or other communication technologies. These means of ...

.Carson, Mary Kay (2007''Alexander Graham Bell: Giving Voice To The World''

Sterling Biographies, New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., pp. 76–78. . In the early 1890s

Nikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla (;"Tesla"

. ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; 10 July 1856 – 7 ...

began his research into high-frequency electricity. Tesla was aware of Hertz's experiments with electromagnetic waves from 1889 on but doubted they existed, and agreed with the prevailing scientific thought at that time that they probably only travel in straight lines, making them useless for long range transmission.

Instead of using radio waves, Tesla's efforts were focused on building a conduction-based power distribution system, although he noted in 1893 that his system could also incorporate communication. His laboratory work and later large-scale experiments at Colorado Springs led him to the conclusion that he could build a conduction-based worldwide wireless system that would use the Earth itself (via injecting very large amounts of an electric current into the ground) as the means to conduct the signal very long distances (across the Earth), overcoming the perceived limitations of other systems. He went on to try to implement his ideas of power transmission and wireless telecommunication in his very large but unsuccessful Wardenclyffe Tower project.

. ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; 10 July 1856 – 7 ...

Development of electromagnetism

Various scientists proposed that electricity and magnetism were linked. Around 1800Alessandro Volta

Alessandro Giuseppe Antonio Anastasio Volta (, ; ; 18 February 1745 – 5 March 1827) was an Italian chemist and physicist who was a pioneer of electricity and Power (physics), power, and is credited as the inventor of the electric battery a ...

developed the first means of producing an electric current. In 1802 Gian Domenico Romagnosi

Gian Domenico Romagnosi (; 11 December 1761 – 8 June 1835) was an Italian philosopher, economist and jurist.

Biography

Gian Domenico Romagnosi was born in Salsomaggiore Terme.

He studied law at the University of Parma from 1782 to 1786. ...

may have suggested a relationship between electricity and magnetism but his reports went unnoticed. In 1820 Hans Christian Ørsted

Hans Christian Ørsted (; 14 August 1777 – 9 March 1851), sometimes Transliteration, transliterated as Oersted ( ), was a Danish chemist and physicist who discovered that electric currents create magnetic fields. This phenomenon is known as ...

performed a simple and today widely known experiment on electric current and magnetism. He demonstrated that a wire carrying a current could deflect a magnetized compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with No ...

needle. Ørsted's work influenced André-Marie Ampère

André-Marie Ampère (, ; ; 20 January 177510 June 1836) was a French physicist and mathematician who was one of the founders of the science of classical electromagnetism, which he referred to as ''electrodynamics''. He is also the inventor of ...

to produce a theory of electromagnetism. Several scientists speculated that light might be connected with electricity or magnetism.

In 1831, Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English chemist and physicist who contributed to the study of electrochemistry and electromagnetism. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

began a series of experiments in which he discovered electromagnetic induction

Electromagnetic or magnetic induction is the production of an electromotive force, electromotive force (emf) across an electrical conductor in a changing magnetic field.

Michael Faraday is generally credited with the discovery of induction in 1 ...

. The relation was mathematically modelled by Faraday's law, which subsequently became one of the four Maxwell equations. Faraday proposed that electromagnetic forces extended into the empty space around the conductor, but did not complete his work involving that proposal. In 1846 Michael Faraday speculated that light was a wave disturbance in a "force field".

Expanding upon a series of experiments by Felix Savary, between 1842 and 1850 Joseph Henry

Joseph Henry (December 17, 1797– May 13, 1878) was an American physicist and inventor who served as the first secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. He was the secretary for the National Institute for the Promotion of Science, a precursor ...

performed experiments detecting inductive magnetic effects over a distance of .Fleming, J. A. (1908)''The Principles of Electric Wave Telegraphy''

London: New York and Co. (cf., Joseph Henry, in the United States, between 1842 and 1850, explored many of the puzzling facts connected with this subject, and only obtained a clue to the anomalies when he realized that the discharge of a condenser through a low resistance circuit is oscillatory in nature. Amongst other things, Henry noticed the power of condenser discharges to induce secondary currents which could magnetize steel needles even when a great distance separated the primary and secondary circuits.)Se

''The Scientific Writings of Joseph Henry''

vol. i. pp. 203, 20:-i; als

"Analysis of the Dynamic Phenomena of the Leyden Jar"

''Proceedings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science'', 1850, vol. iv. pp. 377–78, Joseph Henry. The effect of the oscillatory discharge on a magnetized needle is summarized in this review.Ames, J. S., Henry, J., & Faraday, M. (1900)

''The Discovery of Induced Electric Currents''

New York: American book. (cf. Page 107: "On moving to Princeton, in 1832, enry ..investigated also the discharge of a Leyden jar, proved that it was oscillatory in character, and showed that its inductive effects could be detected at a distance of two hundred feet, thus clearly establishing the existence of electro-magnetic waves.") He was the first (1838–42) to produce high frequency AC electrical oscillations, and to point out and experimentally demonstrate that the discharge of a capacitor under certain conditions is oscillatory, or, as he puts it, consists "''of a principal discharge in one direction and then several reflex actions backward and forward, each more feeble than the preceding until equilibrium is attained''". This view was also later adopted by

Helmholtz

Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz (; ; 31 August 1821 – 8 September 1894; "von" since 1883) was a German physicist and physician who made significant contributions in several scientific fields, particularly hydrodynamic stability. The ...

, the mathematical demonstration of this fact was first given by Lord Kelvin in his paper on " Transient Electric Currents".Fessenden, Reginald (1908)"Wireless Telephony"

''Transactions of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers'' (volume 27, part 1), June 29, 1908, pp. 553–630

Maxwell and the theoretical prediction of electromagnetic waves

Between 1861 and 1865, based on the earlier experimental work of Faraday and other scientists and on his own modification to Ampere's law,James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish physicist and mathematician who was responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism an ...

developed his theory of electromagnetism, which predicted the existence of electromagnetic waves. In 1864 Maxwell described the theoretical basis of the propagation of electromagnetic waves in his paper to the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, "''A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field

"A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field" is a paper by James Clerk Maxwell on electromagnetism, published in 1865. ''(Paper read at a meeting of the Royal Society on 8 December 1864).'' Physicist Freeman Dyson called the publishing of the ...

''." This theory united all previously unrelated observations, experiments and equations of electricity, magnetism, and optics into a consistent theory. His set of equations—Maxwell's equations

Maxwell's equations, or Maxwell–Heaviside equations, are a set of coupled partial differential equations that, together with the Lorentz force law, form the foundation of classical electromagnetism, classical optics, Electrical network, electr ...

—demonstrated that electricity, magnetism, and light are all manifestations of the same phenomenon, the electromagnetic field

An electromagnetic field (also EM field) is a physical field, varying in space and time, that represents the electric and magnetic influences generated by and acting upon electric charges. The field at any point in space and time can be regarde ...

. Subsequently, all other classic laws or equations of these disciplines were special cases of Maxwell's equations. Maxwell's work in electromagnetism has been called the "second great unification in physics", after Newton's unification of gravity in the 17th century.

Oliver Heaviside

Oliver Heaviside ( ; 18 May 1850 – 3 February 1925) was an English mathematician and physicist who invented a new technique for solving differential equations (equivalent to the Laplace transform), independently developed vector calculus, an ...

later reformulated Maxwell's original equations into the set of four vector equations that are generally known today as Maxwell's equations. Neither Maxwell nor Heaviside transmitted or received radio waves; however, their equations for electromagnetic field

An electromagnetic field (also EM field) is a physical field, varying in space and time, that represents the electric and magnetic influences generated by and acting upon electric charges. The field at any point in space and time can be regarde ...

s established principles for radio design, and remain the standard expression of classical electromagnetism.

Of Maxwell's work, Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

wrote:

"Imagine axwell'sfeelings when the differential equations he had formulated proved to him that electromagnetic fields spread in the form of polarised waves, and at the speed of light! To few men in the world has such an experience been vouchsafed... it took physicists some decades to grasp the full significance of Maxwell's discovery, so bold was the leap that his genius forced upon the conceptions of his fellow-workers."Other physicists were equally impressed with Maxwell's work, such as

Richard Feynman

Richard Phillips Feynman (; May 11, 1918 – February 15, 1988) was an American theoretical physicist. He is best known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics, the physics of t ...

who commented:

"From a long view of the history of the world—seen from, say, ten thousand years from now—there can be little doubt that the most significant event of the 19th century will be judged as Maxwell's discovery of the laws of electromagnetism. The American Civil War will pale into provincial insignificance in comparison with this important scientific event of the same decade."

Experiments and proposals

Berend Wilhelm Feddersen, a German physicist, in 1859, as a private scholar inLeipzig

Leipzig (, ; ; Upper Saxon: ; ) is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Saxony. The city has a population of 628,718 inhabitants as of 2023. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, eighth-largest city in Ge ...

, succeeded in experiments with the Leyden jar to prove that electric spark

An electric spark is an abrupt electrical discharge that occurs when a sufficiently high electric field creates an Ionization, ionized, Electric current, electrically conductive channel through a normally-insulating medium, often air or other ga ...

s were composed of damped oscillations.

In 1870 the German physicist Wilhelm von Bezold

Johann Friedrich Wilhelm von Bezold (June 21, 1837 – February 17, 1907) was a German physicist and meteorologist born in Munich, Kingdom of Bavaria. He is best known for discovering the Bezold effect and the Bezold–Brücke shift.

Bezol ...

discovered and demonstrated the fact that the advancing and reflected oscillations produced in conductors by a capacitor discharge gave rise to interference phenomena. Professors Elihu Thomson

Elihu Thomson (March 29, 1853 – March 13, 1937) was an English-American engineer and inventor who was instrumental in the founding of major electricity, electrical companies in the United States, the United Kingdom and France.

Early life

He ...

and E. J. Houston in 1876 made a number of experiments and observations on high frequency oscillatory discharges. In 1883 George FitzGerald suggested at a British Association

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chief ...

meeting that electromagnetic waves could be generated by the discharge of a capacitor, but the suggestion was not followed up, possibly because no means was known for detecting the waves.

Hertz experimentally verifies Maxwell's theory

When German physicist

When German physicist Heinrich Rudolf Hertz

Heinrich Rudolf Hertz (; ; 22 February 1857 – 1 January 1894) was a German physicist who first conclusively proved the existence of the electromagnetic waves predicted by James Clerk Maxwell's equations of electromagnetism.

Biography

Heinric ...

was looking for a subject for his doctoral dissertation in 1879, instructor Hermann von Helmholtz

Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz (; ; 31 August 1821 – 8 September 1894; "von" since 1883) was a German physicist and physician who made significant contributions in several scientific fields, particularly hydrodynamic stability. The ...

suggested he try to prove Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism. Hertz initially couldn't see any way to test the theory but his observation, in the autumn of 1886, of discharging a Leyden jar

A Leyden jar (or Leiden jar, or archaically, Kleistian jar) is an electrical component that stores a high-voltage electric charge (from an external source) between electrical conductors on the inside and outside of a glass jar. It typically co ...

into a large coil and producing a spark in an adjacent coil gave him the idea of how to build a test apparatus.Huurdeman, Anton A. (2003) ''The Worldwide History of Telecommunications''. Wiley. . p. 202 Using a Ruhmkorff coil to create sparks across a gap (a spark gap transmitter

A spark-gap transmitter is an obsolete type of radio transmitter which generates radio waves by means of an electric spark."Radio Transmitters, Early" in Spark-gap transmitters were the first type of radio transmitter, and were the main type use ...

) and observing the sparks created between the gap in a nearby metal loop antenna, between 1886 and 1888 Hertz would conduct a series of scientific experiments that would validate Maxwell's theory. Hertz published his results in a series of papers between 1887 and 1890, and again in complete book form in 1893.

The first of the papers published, "''On Very Rapid Electric Oscillations''", gives an account of the chronological course of his investigation, as far as it was carried out up to the end of the year 1886 and the beginning of 1887.

For the first time, electromagnetic radio waves

Radio waves (formerly called Hertzian waves) are a type of electromagnetic radiation with the lowest frequencies and the longest wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum, typically with frequencies below 300 gigahertz (GHz) and wavelengths ...

("Hertzian waves") were intentionally and unequivocally proven to have been transmitted through free space

A vacuum (: vacuums or vacua) is space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective (neuter ) meaning "vacant" or "void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressur ...

by a spark-gap device, and detected over a short distance.

inductance

Inductance is the tendency of an electrical conductor to oppose a change in the electric current flowing through it. The electric current produces a magnetic field around the conductor. The magnetic field strength depends on the magnitude of the ...

and capacitance

Capacitance is the ability of an object to store electric charge. It is measured by the change in charge in response to a difference in electric potential, expressed as the ratio of those quantities. Commonly recognized are two closely related ...

of his transmitting and receiving antennas. He focused the electromagnetic waves using a corner reflector

A corner reflector is a retroreflector consisting of three mutually perpendicular, intersecting flat reflective surfaces. It reflects waves incident from any direction directly towards the source, but translated. The three intersecting surfa ...

and a parabolic reflector

A parabolic (or paraboloid or paraboloidal) reflector (or dish or mirror) is a Mirror, reflective surface used to collect or project energy such as light, sound, or radio waves. Its shape is part of a circular paraboloid, that is, the surface ge ...

, to demonstrate that radio behaved the same as light, as Maxwell's electromagnetic theory had predicted more than 20 years earlier.

Hertz did not devise a system for practical utilization of electromagnetic waves, nor did he describe any potential applications of the technology. Hertz was asked by his students at the University of Bonn what use there might be for these waves. He replied, "''It's of no use whatsoever. This is just an experiment that proves Maestro Maxwell was right, we just have these mysterious electromagnetic waves that we cannot see with the naked eye. But they are there.''"

Many physicists quickly realized that Hertzian waves could be used (instead of light) in systems akin to optical telegraph

An optical telegraph is a line of stations, typically towers, for the purpose of conveying textual information by means of visual signals (a form of optical communication). There are two main types of such systems; the semaphore telegraph whic ...

: for example, Richard Threlfall and John Perry suggested that in 1890, Alexander Pelham Trotter in 1891 and Frederick Thomas Trouton in 1892, however they all thought about it in terms of short flashes as opposed to telegraphic dots and dashes. In what may have been a little noticed article titled 'Some possibilities of electricity' in the February 1892 in '' The Fortnightly Review'', Sir William Crookes

Sir William Crookes (; 17 June 1832 – 4 April 1919) was an English chemist and physicist who attended the Royal College of Chemistry, now part of Imperial College London, and worked on spectroscopy. He was a pioneer of vacuum tubes, inventing ...

described wireless telegraphy as having been accomplished a year earlier, although the method and type is not described. The American physicist Amos Emerson Dolbear brought similar attention to the idea a year later. Hertz's health deteriorated after a severe infection in 1892 and he died in 1894, so the art of radio wave communication was left to others to implement into a practical form.

Pre-Hertz radio wave detection

During 1789–91,Luigi Galvani

Luigi Galvani ( , , ; ; 9 September 1737 – 4 December 1798) was an Italian physician, physicist, biologist and philosopher who studied animal electricity. In 1780, using a frog, he discovered that the muscles of dead frogs' legs twitched when ...

noticed that a spark generated nearby caused a convulsion in a frog's leg being touched by a scalpel."Wireless before Marconi" by L. V. Lindell (2006), included in ''History of Wireless'' by T. K. Sarkar, Robert Mailloux, Arthur A. Oliner, M. Salazar-Palma, Dipak L. Sengupta, John Wiley & Sons, pp. 258–61 In different experiments, he noticed contractions in frogs' legs caused by lightning and a luminous discharge from a charged Leyden jar that disappeared over time and was renewed whenever a spark occurred nearby.

Joseph Henry

Joseph Henry (December 17, 1797– May 13, 1878) was an American physicist and inventor who served as the first secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. He was the secretary for the National Institute for the Promotion of Science, a precursor ...

observed magnetised needles from lightning in the early 1840s.

In 1852 Samuel Alfred Varley noticed a remarkable fall in the resistance of masses of metallic filings under the action of atmospheric electrical discharges.

Towards the end of 1875, while experimenting with the

Towards the end of 1875, while experimenting with the telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

, Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February11, 1847October18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventions, ...

noted a phenomenon that he termed " etheric force", announcing it to the press on 28 November. He abandoned this research when Elihu Thomson

Elihu Thomson (March 29, 1853 – March 13, 1937) was an English-American engineer and inventor who was instrumental in the founding of major electricity, electrical companies in the United States, the United Kingdom and France.

Early life

He ...

, among others, ridiculed the idea, claiming it was electromagnetic induction.

In 1879 the experimenter and inventor David Edward Hughes

David Edward Hughes (16 May 1830 – 22 January 1900), was a British-American inventor, practical experimenter, and professor of music known for his work on the printing telegraph and the microphone. He is generally considered to have bee ...

, working in London, discovered that a bad contact in a Bell telephone he was using in his experiments seemed to be sparking when he worked on a nearby induction balance (an early form of metal detector

A metal detector is an instrument that detects the nearby presence of metal. Metal detectors are useful for finding metal objects on the surface, underground, and under water. A metal detector consists of a control box, an adjustable shaft, and ...

).Walters, Rob (2005) ''Spread Spectrum: Hedy Lamarr and the Mobile Phone'', Satin, page 16''The Electrician'', Volume 43"Notes"

(May 5, 1899, p. 35)

"Prof. D. E. Hughes's Researches in Wireless Telegraphy"

by J. J. Fahie (May 5, 1899, pp. 40–41)

"The National Telephone Company's Staff Dinner"

(Hughes remarks), (May 12, 1899, pp. 93–94) He developed an improved detector to pick up this unknown "extra current" based on his new microphone design (similar to later detectors known as

coherer

The coherer was a primitive form of radio signal detector used in the first radio receivers during the wireless telegraphy era at the beginning of the 20th century. Its use in radio was based on the 1890 findings of French physicist Édouard Bra ...

s or crystal detector

A crystal detector is an obsolete electronic component used in some early 20th century radio receivers. It consists of a piece of crystalline mineral that rectifies an alternating current radio signal. It was employed as a detector ( demod ...

s) and developed a way to interrupt his induction balance to produce a series of sparks. By trial and error

Trial and error is a fundamental method of problem-solving characterized by repeated, varied attempts which are continued until success, or until the practicer stops trying.

According to W.H. Thorpe, the term was devised by C. Lloyd Morgan ( ...

experiment

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome occurs whe ...

s he eventually found he could pick up these "aerial waves" as he carried his telephone device down the street out to a range of .

On 20 February 1880, he demonstrated his experiment to representatives of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

including Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist who specialized in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

, Sir George Gabriel Stokes

Sir George Gabriel Stokes, 1st Baronet, (; 13 August 1819 – 1 February 1903) was an Irish mathematician and physicist. Born in County Sligo, Ireland, Stokes spent his entire career at the University of Cambridge, where he served as the Lucasi ...

, and William Spottiswoode, then president of the Society. Stokes was convinced the phenomenon Hughes was demonstrating was merely electromagnetic induction

Electromagnetic or magnetic induction is the production of an electromotive force, electromotive force (emf) across an electrical conductor in a changing magnetic field.

Michael Faraday is generally credited with the discovery of induction in 1 ...

, not a type of conduction through the air. Hughes was not a physicist and seems to have accepted Stokes observations and did not pursue the experiments any further. His work may have been the wireless experiment William Crookes recalled in his 1892 ''Fortnightly Review'' review of 'Some possibilities of electricity'.Crookes, William (February 1, 1892"Some Possibilities of Electricity"

''The Fortnightly Review'', pp. 173–81

Development of radio waves

The Branly detector

In 1890,Édouard Branly

Édouard Eugène Désiré Branly (, ; ; 23 October 1844 – 24 March 1940) was a French physicist and inventor known for his early involvement in wireless telegraphy and his invention of the coherer in 1890.

Biography

He was born on 23 October 1 ...

demonstrated a new type of detector. Branly discovered that loose metal filings, which in a normal state have a high electrical resistance, lost their resistance in the presence of electric oscillations generated by a spark, and became practically conductors of electricity. This Branly showed by placing metal filings in a glass box or tube, and making them part of an ordinary electric circuit. Branly further found that when the filings had once adhered tegether they retained their low resistance until shaken apart, for instance, by tapping on the tube. Branly's filing tube came to light when it was described by Dr. Dawson Turner at a meeting of the British Association in Edinburgh and Scottish electrical engineer and astronomer George Forbes suggests the filings tube may be reacting in the presence of Hertzian waves. This device would be picked up by Oliver Lodge

Sir Oliver Joseph Lodge (12 June 1851 – 22 August 1940) was an English physicist whose investigations into electromagnetic radiation contributed to the development of Radio, radio communication. He identified electromagnetic radiation indepe ...

in his experiments.

Lodge's demonstrations

Britishphysicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe. Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

and writer Sir Oliver Lodge

Sir Oliver Joseph Lodge (12 June 1851 – 22 August 1940) was an English physicist whose investigations into electromagnetic radiation contributed to the development of Radio, radio communication. He identified electromagnetic radiation indepe ...

came close to being the first to prove the existence of Maxwell's electromagnetic waves. In a series of spring 1888 experiments conducted with a Leyden jar connected to a length of wire with spaced spark gaps he noticed he was getting different size sparks and a glow pattern along the wire that seemed to be a function of wavelength.James P. RybakOliver Lodge: Almost the Father of Radio

, page 4, from Antique Wireless Before he could present his own findings he learned of Hertz' series of proofs on the same subject. On 1 June 1894, at a meeting of the

British Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a Charitable organization, charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Scienc ...

at Oxford University, Lodge gave a memorial lecture on the work of Hertz (recently deceased) and the German physicist's proof of the existence of electromagnetic waves 6 years earlier. Lodge set up a demonstration on the quasi-optical nature of "Hertzian waves" (radio waves) and demonstrated their similarity to light and vision including reflection and transmission.Sungook Hong, Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion, MIT Press, 2001, pp. 30–32 Later in June and on 14 August 1894 he did similar experiments, increasing the distance of transmission up to 55 meters. In these lectures Lodge demonstrated a detector that would become standard in radio work, an improved version of Branly's detector which Lodge dubbed the ''coherer

The coherer was a primitive form of radio signal detector used in the first radio receivers during the wireless telegraphy era at the beginning of the 20th century. Its use in radio was based on the 1890 findings of French physicist Édouard Bra ...

''. It consisted of a glass tube containing metal filings between two electrodes. When the small electrical charge from waves from an antenna were applied to the electrodes, the metal particles would cling together or " cohere" causing the device to become conductive allowing the current from a battery to pass through it. In Lodge's setup the slight impulses from the coherer were picked up by a mirror galvanometer

A mirror galvanometer is an ammeter that indicates it has sensed an electric Current (electricity), current by deflecting a light beam with a mirror. The beam of light projected on a scale acts as a long massless pointer. In 1826, Johann Chri ...

which would deflect a beam of light being projected on it, giving a visual signal that the impulse was received. After receiving a signal the metal filings in the coherer were broken apart or "decohered" by a manually operated vibrator or by the vibrations of a bell placed on the table near by that rang every time a transmission was received. Lodge also demonstrated tuning using a pair of Leyden jars that could be brought into resonance.W.A. Atherton, From Compass to Computer: History of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, Macmillan International Higher Education, 1984, p. 185 Lodge's lectures were widely publicized and his techniques influenced and were expanded on by other radio pioneers including Augusto Righi

Augusto Righi (; 27 August 1850 – 8 June 1920) was an Italian physicist who was one of the first scientists to produce microwaves.

Biography

Born in Bologna, Righi was educated in his home town, taught physics at Bologna Technical College bet ...

and his student Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, 1st Marquess of Marconi ( ; ; 25 April 1874 – 20 July 1937) was an Italian electrical engineer, inventor, and politician known for his creation of a practical radio wave-based Wireless telegraphy, wireless tel ...

, Alexander Popov, Lee de Forest #REDIRECT Lee de Forest

{{redirect category shell, {{R from move{{R from other capitalisation ...

, and Jagadish Chandra Bose

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose (; ; 30 November 1858 – 23 November 1937) was a polymath with interests in biology, physics and writing science fiction. He was a pioneer in the investigation of radio microwave optics, made significant contributions ...

.

Lodge at the time seemed to see no value in using radio waves for signalling or wireless telegraphy and there is debate as to whether he even bothered to demonstrate communication during his lectures. Physicist John Ambrose Fleming

Sir John Ambrose Fleming (29 November 1849 – 18 April 1945) was an English electrical engineer who invented the vacuum tube, designed the radio transmitter with which the first transatlantic radio transmission was made, and also established ...

pointed out that Lodge's lecture was a physics experiment, not a demonstration of telegraphic signaling.Sungook Hong, Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion, MIT Press, 2001, page 48 After radio communication was developed Lodge's lecture would become the focus of priority disputes over who invented wireless telegraphy (radio). His early demonstration and later development of radio tuning (his 1898 Syntonic tuning patent) would lead to patent disputes with the Marconi Company. When Lodge's syntonic patent was extended in 1911 for another seven years Marconi agreed to settle the patent dispute and purchase the patent.

Bose's microwave research

Inspired by Lodge's demonstrations theIndia

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

n physicist, Jagadish Chandra Bose

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose (; ; 30 November 1858 – 23 November 1937) was a polymath with interests in biology, physics and writing science fiction. He was a pioneer in the investigation of radio microwave optics, made significant contributions ...

, in 1894 - 1900 conducted the first research into the properties of millimetre length radio waves, in the microwave

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths shorter than other radio waves but longer than infrared waves. Its wavelength ranges from about one meter to one millimeter, corresponding to frequency, frequencies between 300&n ...

range of about 5 mm wavelength

In physics and mathematics, wavelength or spatial period of a wave or periodic function is the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

In other words, it is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same ''phase (waves ...

. Working from a small laboratory he set up in November of 1894 at the Presidency College of the University of Calcutta

The University of Calcutta, informally known as Calcutta University (), is a Public university, public State university (India), state university located in Kolkata, Calcutta (Kolkata), West Bengal, India. It has 151 affiliated undergraduate c ...

, he researched the properties of materials at microwave frequencies, inventing a microwave spectrometer consisting of a spark transmitter, coherer

The coherer was a primitive form of radio signal detector used in the first radio receivers during the wireless telegraphy era at the beginning of the 20th century. Its use in radio was based on the 1890 findings of French physicist Édouard Bra ...

receiver, as well as the first waveguide

A waveguide is a structure that guides waves by restricting the transmission of energy to one direction. Common types of waveguides include acoustic waveguides which direct sound, optical waveguides which direct light, and radio-frequency w ...

, horn antenna

A horn antenna or microwave horn is an antenna (radio), antenna that consists of a flaring metal waveguide shaped like a horn (acoustic), horn to direct radio waves in a beam. Horns are widely used as antennas at Ultrahigh frequency, UHF and m ...

and semiconductor crystal detector

A crystal detector is an obsolete electronic component used in some early 20th century radio receivers. It consists of a piece of crystalline mineral that rectifies an alternating current radio signal. It was employed as a detector ( demod ...

In November 1895 at a public demonstration at the Town Hall

In local government, a city hall, town hall, civic centre (in the UK or Australia), guildhall, or municipal hall (in the Philippines) is the chief administrative building of a city, town, or other municipality. It usually houses the city o ...

of Kolkata, Bose showed how these new waves could travel through the human body (of Lieutenant Governor Sir William Mackenzie), and over a distance of 23 metres (75') through two intervening walls to a trigger apparatus he had set up to ring a bell and ignite gunpowder in a closed room. Sarkar, Tapan; Sengupta, Dipak L. "An appreciation of J. C. Bose's pioneering work in millimeter and microwaves" in archiveEmerson, National Radio Astronomy Observatory website

/ref> However he was not interested in researching the use of radio waves for communication.

Adaptations of radio waves

Popov's lightning detector

In 1894–95 the Russian physicist Alexander Stepanovich Popov conducted experiments developing a

In 1894–95 the Russian physicist Alexander Stepanovich Popov conducted experiments developing a radio receiver

In radio communications, a radio receiver, also known as a receiver, a wireless, or simply a radio, is an electronic device that receives radio waves and converts the information carried by them to a usable form. It is used with an antenna. ...

, an improved version of coherer

The coherer was a primitive form of radio signal detector used in the first radio receivers during the wireless telegraphy era at the beginning of the 20th century. Its use in radio was based on the 1890 findings of French physicist Édouard Bra ...

-based design by Oliver Lodge

Sir Oliver Joseph Lodge (12 June 1851 – 22 August 1940) was an English physicist whose investigations into electromagnetic radiation contributed to the development of Radio, radio communication. He identified electromagnetic radiation indepe ...

. His design with coherer auto-tapping mechanism was designed as a lightning detector to help the forest service track lightning strikes that could start fires. His receiver proved to be able to sense lightning strikes at distances of up to 30 km. Popov built a version of the receiver that was capable of automatically recording lightning strikes on paper rolls. Popov presented his radio receiver to the Russian Physical and Chemical Society on 7 May 1895 — the day has been celebrated in the Russian Federation as " Radio Day" promoted in eastern European countries as the inventor of radio. The paper on his findings was published the same year (15 December 1895). Popov had recorded, at the end of 1895, that he was hoping for distant signaling with radio waves. He did not apply for a patent for this invention.

Tesla's boat

In 1898Nikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla (;"Tesla"

. ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; 10 July 1856 – 7 ...

developed a radio/coherer based remote-controlled boat, with a form of . ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; 10 July 1856 – 7 ...

secure communication

Secure communication is when two entities are communicating and do not want a third party to listen in. For this to be the case, the entities need to communicate in a way that is unsusceptible to eavesdropping or interception. Secure communication ...

Tesla, N., & Anderson, L. I. (1998). ''Nikola Tesla: Guided Weapons & Computer Technology''. Tesla presents series, pt. 3. Breckenridge, Colo: Twenty-First Century Books. between transmitter and receiver, which he demonstrated in 1898. Tesla called his invention a "teleautomaton" and he hoped to sell it as a guided naval torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

.

Radio based wireless telegraphy

Marconi

Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, 1st Marquess of Marconi ( ; ; 25 April 1874 – 20 July 1937) was an Italian electrical engineer, inventor, and politician known for his creation of a practical radio wave-based Wireless telegraphy, wireless tel ...

studied at the Leghorn Technical School, and acquainted himself with the published writings of Professor Augusto Righi

Augusto Righi (; 27 August 1850 – 8 June 1920) was an Italian physicist who was one of the first scientists to produce microwaves.

Biography

Born in Bologna, Righi was educated in his home town, taught physics at Bologna Technical College bet ...

of the University of Bologna

The University of Bologna (, abbreviated Unibo) is a Public university, public research university in Bologna, Italy. Teaching began around 1088, with the university becoming organised as guilds of students () by the late 12th century. It is the ...

. In 1894, Sir William Preece delivered a paper to the Royal Institution in London on electric signalling without wires. In 1894 at the Royal Institution lectures, Lodge delivered "The Work of Hertz and Some of His Successors"."The Work of Hertz" by Oliver Lodge''Proceedings'' (volume 14: 1893–95), Royal Institution of Great Britain, pp. 321–49 Marconi is said to have read, while on vacation in 1894, about the experiments that Hertz did in the 1880s. Marconi also read about Tesla's work. It was at this time that Marconi began to understand that radio waves could be used for wireless communications. Marconi's early apparatus was a development of Hertz's laboratory apparatus into a system designed for communications purposes. At first Marconi used a transmitter to ring a bell in a receiver in his attic laboratory. He then moved his experiments out-of-doors on the family estate near

Bologna, Italy

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

, to communicate further. He replaced Hertz's vertical dipole with a vertical wire topped by a metal sheet, with an opposing terminal connected to the ground. On the receiver side, Marconi replaced the spark gap with a metal powder coherer, a detector developed by Edouard Branly and other experimenters. Marconi transmitted radio signals for about at the end of 1895.

Marconi was awarded a patent for radio with British patentbr>No. 12,039''Improvements in Transmitting Electrical Impulses and Signals and in Apparatus There-for''. The complete specification was filed 2 March 1897. This was Marconi's initial patent for the radio, though it used various earlier techniques of various other experimenters and resembled the instrument demonstrated by others (including Popov). During this time spark-gap wireless telegraphy was widely researched. In July, 1896, Marconi got his invention and new method of telegraphy to the attention of Preece, then engineer-in-chief to the

British Government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Telegraph Service, who had for the previous twelve years interested himself in the development of wireless telegraphy by the inductive-conductive method. On 4 June 1897, he delivered "Signalling through Space without Wires". Preece devoted considerable time to exhibiting and explaining the Marconi apparatus at the Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...