Influences On Karl Marx on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Influences on Karl Marx are generally thought to have been derived from three main sources, namely German idealist philosophy, French socialism and English and Scottish political economy.

Influences on Karl Marx are generally thought to have been derived from three main sources, namely German idealist philosophy, French socialism and English and Scottish political economy.

Marx's revision of

Marx's revision of

Influences on Karl Marx are generally thought to have been derived from three main sources, namely German idealist philosophy, French socialism and English and Scottish political economy.

Influences on Karl Marx are generally thought to have been derived from three main sources, namely German idealist philosophy, French socialism and English and Scottish political economy.

German philosophy

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

is believed to have had a greater influence than any other philosopher of modern times. Kantian philosophy

Kantianism () is the philosophy of Immanuel Kant, a Germans, German philosopher born in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia). The term ''Kantianism'' or ''Kantian'' is sometimes also used to describe contemporary positions in philosop ...

was the basis on which the structure of Marxism was built—particularly as it was developed by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political philosophy and t ...

. Hegel's dialectical method, which was taken up by Karl Marx

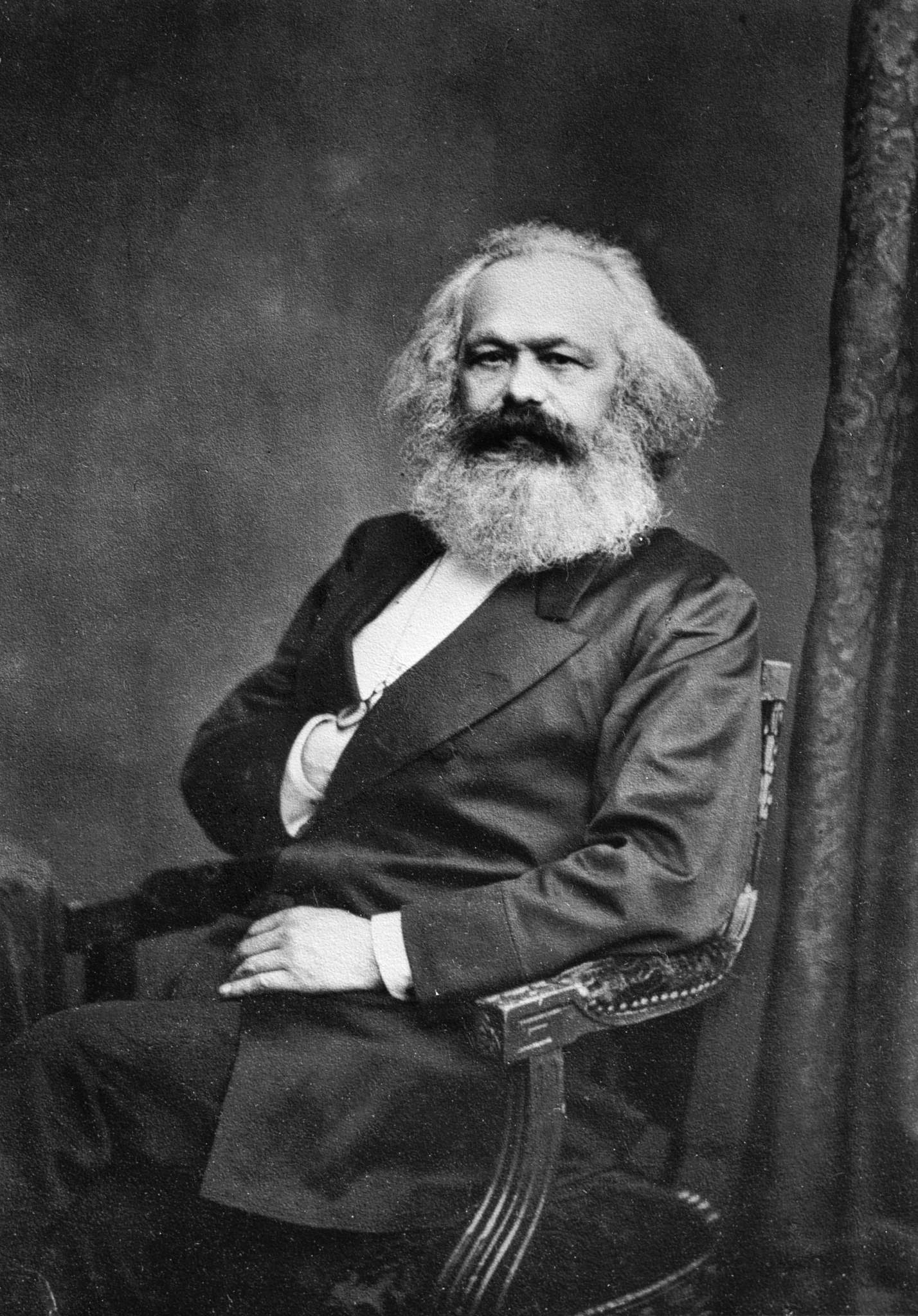

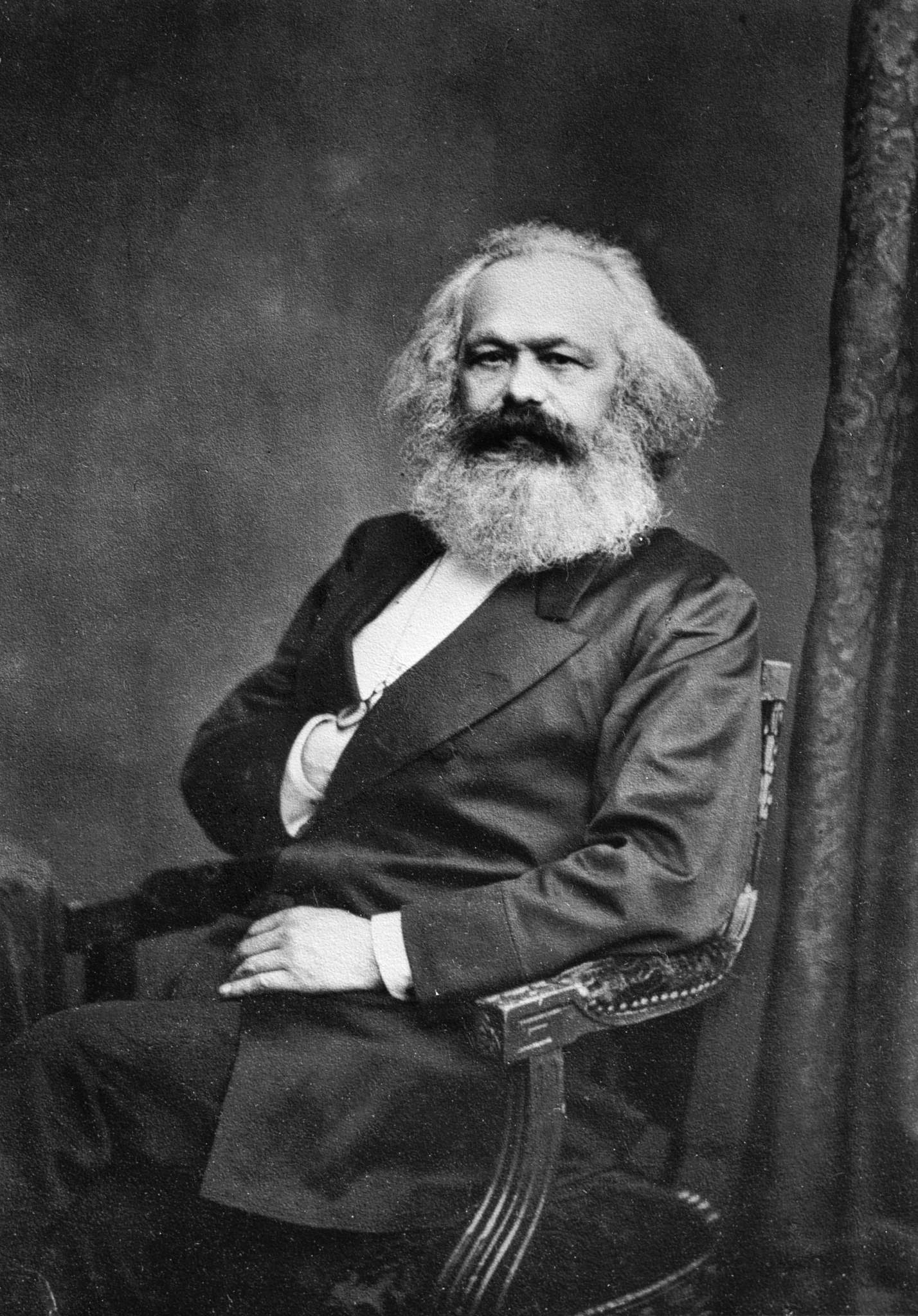

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

, was an extension of the method of reasoning by antinomies that Kant used.

Philip J. Kain believes Kant was especially influential on Young Marx

The correct place of Karl Marx's early writings within his system as a whole has been a matter of great controversy. Some believe there is a ''break'' in Marx's development that divides his thought into two periods: the "Young Marx" is said to be ...

's ethical views.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

By the time of his death, Hegel was the most prominent philosopher in Germany. His views were widely taught and his students were highly regarded. His followers soon divided intoright-wing

Right-wing politics is the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position based on natural law, economics, authority, property ...

and left-wing Hegelians. Theologically and politically, the right-wing Hegelians offered a conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

interpretation of his work. They emphasized the compatibility between Hegel's philosophy and Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

; they were orthodox. The left-wing Hegelians eventually moved to an atheistic position. In politics, many of them became revolutionaries

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates for, a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective to describe something producing a major and sudden impact on society.

Definition

The term—bot ...

. This historically important left-wing group included Ludwig Feuerbach

Ludwig Andreas von Feuerbach (; ; 28 July 1804 – 13 September 1872) was a German anthropologist and philosopher, best known for his book '' The Essence of Christianity'', which provided a critique of Christianity that strongly influenced ge ...

, Bruno Bauer

Bruno Bauer (; ; 6 September 180913 April 1882) was a German philosopher and theologian. As a student of G. W. F. Hegel, Bauer was a radical Rationalist in philosophy, politics and Biblical criticism. Bauer investigated the sources of the New T ...

, Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;"Engels"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.historical materialism Historical materialism is Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx located historical change in the rise of Class society, class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods. Karl Marx stated that Productive forces, techno ...

, is certainly influenced by Hegel's claim that ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.historical materialism Historical materialism is Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx located historical change in the rise of Class society, class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods. Karl Marx stated that Productive forces, techno ...

reality

Reality is the sum or aggregate of everything in existence; everything that is not imagination, imaginary. Different Culture, cultures and Academic discipline, academic disciplines conceptualize it in various ways.

Philosophical questions abo ...

and history

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

should be viewed dialectically. Hegel believed that the direction of human history is characterized in the movement from the fragmentary toward the complete and the real (which was also a movement towards greater and greater rationality). Sometimes, Hegel explained that this progressive unfolding of the Absolute

Absolute may refer to:

Companies

* Absolute Entertainment, a video game publisher

* Absolute Radio, (formerly Virgin Radio), independent national radio station in the UK

* Absolute Software Corporation, specializes in security and data risk ma ...

involves gradual, evolutionary accretion, but at other times requires discontinuous, revolutionary leaps—episodal upheavals against the existing ''status quo

is a Latin phrase meaning the existing state of affairs, particularly with regard to social, economic, legal, environmental, political, religious, scientific or military issues. In the sociological sense, the ''status quo'' refers to the curren ...

''. For example, Hegel strongly opposed slavery in the United States

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of List of ethnic groups of Africa, Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865 ...

during his lifetime and envisioned a time when Christian nations would radically eliminate it from their civilization.

While Marx accepted this broad conception of history, Hegel was an idealist and Marx sought to rewrite dialectic

Dialectic (; ), also known as the dialectical method, refers originally to dialogue between people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing to arrive at the truth through reasoned argument. Dialectic resembles debate, but the ...

s in materialist

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism according to which matter is the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materia ...

terms. He summarized the materialistic aspect of his theory of history in the 1859 preface to ''A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy

''A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy'' () is a book by Karl Marx, first published in 1859. The book is mainly a critique of political economy achieved by critiquing the writings of the leading theoretical exponents of capitalism ...

'':In the social production of their existence, men inevitably enter into definite relations, which are independent of their will, namelyIn this brief popularization of his ideas, Marx emphasized that social development sprang from the inherent contradictions within material life and the socialrelations of production Relations of production () is a concept frequently used by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in their theory of historical materialism and in ''Das Kapital''. It is first explicitly used in Marx's published book '' The Poverty of Philosophy'', al ...appropriate to a given stage in the development of their materialforces of production Productive forces, productive powers, or forces of production ( German: ''Produktivkräfte'') is a central idea in Marxism and historical materialism. In Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels' own critique of political economy, it refers to the combin .... The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. Themode of production In the Marxist theory of historical materialism, a mode of production (German: ''Produktionsweise'', "the way of producing") is a specific combination of the: * Productive forces: these include human labour power and means of production (tools, ...of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.

superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

. This notion is often understood as a simple historical narrative: primitive communism

Primitive communism is a way of describing the gift economies of hunter-gatherers throughout history, where resources and property hunted or gathered are shared with all members of a group in accordance with individual needs. In political sociolo ...

had developed into slave states

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were prohibited. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave s ...

. Slave states had developed into feudal societies. Those societies in turn became capitalist state

The capitalist state is the state, its functions and the form of organization it takes within capitalist socioeconomic systems.Jessop, Bob (January 1977). "Recent Theories of the Capitalist State". ''Soviet Studies''. 1: 4. pp. 353–373. Th ...

s and those states would be overthrown by the self-conscious portion of their working class

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

, or proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian or a . Marxist ph ...

, creating the conditions for socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

and ultimately a higher form of communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

than that with which the whole process began. Marx illustrated his ideas most prominently by the development of capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

from feudalism and by the prediction of the development of communism from capitalism.

Ludwig Feuerbach

Ludwig Feuerbach

Ludwig Andreas von Feuerbach (; ; 28 July 1804 – 13 September 1872) was a German anthropologist and philosopher, best known for his book '' The Essence of Christianity'', which provided a critique of Christianity that strongly influenced ge ...

was a German philosopher and anthropologist. Feuerbach proposed that people should interpret social and political thought as their foundation and their material needs. He held that an individual is the product of their environment and that the whole consciousness of a person is the result of the interaction of sensory organs and the external world. Marx and Engels saw in Feuerbach's emphasis on people and human needs a movement toward a materialistic interpretation of society. In '' The Essence of Christianity'' (1841), Feuerbach argued that God is really a creation of man and that the qualities people attribute to God are really qualities of humanity. Accordingly, Marx argued that it is the material world that is real and that our ideas of it are consequences, not causes, of the world. Thus, like Hegel and other philosophers, Marx distinguished between appearances and reality. However, he did not believe that the material world hides from us the real world of the ideal; on the contrary, he thought that historically and socially specific ideology prevented people from seeing the material conditions of their lives clearly.

What distinguished Marx from Feuerbach was his view of Feuerbach's humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and Agency (philosophy), agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The me ...

as excessively abstract and so no less ahistorical and idealist than what it purported to replace, namely the reified notion of God found in institutional Christianity that legitimized the repressive power of the Prussian state. Instead, Marx aspired to give ontological

Ontology is the philosophical study of being. It is traditionally understood as the subdiscipline of metaphysics focused on the most general features of reality. As one of the most fundamental concepts, being encompasses all of reality and every ...

priority to what he called the real life process of real human beings as he and Engels said in ''The German Ideology

''The German Ideology'' (German: ''Die deutsche Ideologie''), also known as ''A Critique of the German Ideology'', is a set of manuscripts written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels around April or early May 1846. Marx and Engels did not find a p ...

'' (1846): In direct contrast to German philosophy, which descends from heaven to earth, here we ascend from earth to heaven. That is to say, we do not set out from what men say, imagine, conceive, nor from men as narrated, thought of, imagined, conceived, in order to arrive at men in the flesh. We set out from real, active men, and on the basis of their real life process we demonstrate the development of the ideological reflexes and echoes of this life process. The phantoms formed in the human brain are also, necessarily, sublimates of their material life process, which is empirically verifiable and bound to material premises. Morality, religion, metaphysics, all the rest of ideology and their corresponding forms of consciousness, thus no longer retain the semblance of independence. They have no history, no development; but men, developing their material production and their material intercourse, alter, along with this, their real existence, their thinking, and the products of their thinking. Life is not determined by consciousness, but consciousness by life.In his "

Theses on Feuerbach

The "Theses on Feuerbach" are eleven short philosophical notes written by Karl Marx as a basic outline for the first chapter of the book ''The German Ideology'' in 1845. Like the book for which they were written, the theses were never published i ...

" (1844), he also writes that "the philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways, the point is to change it". This opposition between firstly various subjective interpretations given by philosophers, which may be in a sense compared with designed to legitimize the current state of affairs; and secondly, the effective transformation of the world through praxis, which combines theory and practice in a materialist way, is what distinguishes Marxist philosophers from the rest of philosophers. Indeed, Marx's break with German idealism involves a new definition of philosophy as Louis Althusser

Louis Pierre Althusser (, ; ; 16 October 1918 – 22 October 1990) was a French Marxist philosopher who studied at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, where he eventually became Professor of Philosophy.

Althusser was a long-time member an ...

, founder of structural Marxism

Structural Marxism (sometimes called Althusserian Marxism) is an approach to Marxist philosophy based on structuralism, primarily associated with the work of the French philosopher Louis Althusser and his students. It was influential in France ...

in the 1960s, would define it as class struggle

In political science, the term class conflict, class struggle, or class war refers to the economic antagonism and political tension that exist among social classes because of clashing interests, competition for limited resources, and inequali ...

in theory

A theory is a systematic and rational form of abstract thinking about a phenomenon, or the conclusions derived from such thinking. It involves contemplative and logical reasoning, often supported by processes such as observation, experimentation, ...

. Marx's movement away from university philosophy and towards the workers' movement

The labour movement is the collective organisation of Working class, working people to further their shared political and economic interests. It consists of the trade union or labour union movement, as well as political parties of labour. It ca ...

is thus inextricably linked to his rupture with his earlier writings, which pushed Marxist commentators to speak of a young Marx

The correct place of Karl Marx's early writings within his system as a whole has been a matter of great controversy. Some believe there is a ''break'' in Marx's development that divides his thought into two periods: the "Young Marx" is said to be ...

and a mature Marx, although the nature of this cut poses problems. A year before the Revolutions of 1848

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

, Marx and Engels thus wrote ''The Communist Manifesto

''The Communist Manifesto'' (), originally the ''Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (), is a political pamphlet written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, commissioned by the Communist League and originally published in London in 1848. The ...

'', which was prepared to an imminent revolution and ended with the famous cry: " Proletarians of all countries, unite!". However, Marx's thought changed again following Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

's 2 December 1851 coup, which put an end to the French Second Republic

The French Second Republic ( or ), officially the French Republic (), was the second republican government of France. It existed from 1848 until its dissolution in 1852.

Following the final defeat of Napoleon, Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle ...

and created the Second Empire which would last until the 1870 Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

. Marx thereby modified his theory of alienation exposed in the ''Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844

The ''Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844'' (), also known as the ''Paris Manuscripts'' (') or as the ''1844 Manuscripts'', are a series of unfinished notes written between April and August 1844 by Karl Marx. They were compiled and publi ...

'' and would later arrive to his theory of commodity fetishism

In Marxist philosophy, commodity fetishism is the perception of the economic relationships of production and exchange as relationships among things (money and merchandise) rather than among people. As a form of Reification (Marxism), reificati ...

, exposed in the first chapter of the first book of (1867). This abandonment of the early theory of alienation would be amply discussed, several Marxist theorists, including Marxist humanist

Marxist humanism is a philosophical and political movement that interprets Karl Marx's works through a humanist lens, focusing on human nature and the social conditions that best support human flourishing. Marxist humanists argue that Marx him ...

s such as the Praxis School, would return to it. Others such as Althusser would claim that the epistemological break between the young Marx and the mature Marx was such that no comparisons could be done between both works, marking a shift to a scientific theory of society.

Rupture with German idealism and the Young Hegelians

Marx did not study directly with Hegel, but after Hegel's death he studied under one of Hegel's pupils,Bruno Bauer

Bruno Bauer (; ; 6 September 180913 April 1882) was a German philosopher and theologian. As a student of G. W. F. Hegel, Bauer was a radical Rationalist in philosophy, politics and Biblical criticism. Bauer investigated the sources of the New T ...

, a leader of the circle of Young Hegelians to whom Marx attached himself. However, Marx and Engels came to disagree with Bauer and the rest of the Young Hegelians about socialism and also about the usage of Hegel's dialectic. From 1841, the young Marx progressively broke away from German idealism and the Young Hegelians. Along with Engels, who observed the Chartist movement in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, he cut away with the environment in which he grew up and encountered the proletariat in France and Germany.

He then wrote a scathing criticism of the Young Hegelians in two books, '' The Holy Family'' (1845) and ''The German Ideology'' in which he criticized not only Bauer, but also Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt (; 25 October 1806 – 26 June 1856), known professionally as Max Stirner (; ), was a German post-Hegelian philosopher, dealing mainly with the Hegelian notion of social alienation and self-consciousness. Stirner is oft ...

's ''The Ego and Its Own

''The Ego and Its Own'' (), also known as ''The Unique and Its Property'', is an 1844 work by German philosopher Max Stirner. It presents a post-Hegelian critique of Christianity and traditional morality on one hand; and on the other, humanism, ...

'' (1844), considered as one of the founding book of individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism or anarcho-individualism is a collection of anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hi ...

. Stirner claimed that all ideals were inherently alienating and that replacing God by the humanity—as did Ludwig Feuerbach in ''The Essence of Christianity''—was not sufficient. According to Stirner, any ideals, God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

, humanity, the nation

A nation is a type of social organization where a collective Identity (social science), identity, a national identity, has emerged from a combination of shared features across a given population, such as language, history, ethnicity, culture, t ...

, or even the revolution

In political science, a revolution (, 'a turn around') is a rapid, fundamental transformation of a society's class, state, ethnic or religious structures. According to sociologist Jack Goldstone, all revolutions contain "a common set of elements ...

alienated the Ego. In ''The Poverty of Philosophy

''The Poverty of Philosophy'' (French: ''Misère de la philosophie'') is a book by Karl Marx published in Paris and Brussels in 1847, where he lived in exile from 1843 until 1849. It was originally written in French language, French as a critique ...

'' (1845), Marx also criticized Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, ; ; 1809 – 19 January 1865) was a French anarchist, socialist, philosopher, and economist who founded mutualist philosophy and is considered by many to be the "father of anarchism". He was the first person to ca ...

, who had become famous with his cry "Property is theft!

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

".

Marx's early writings are thus a response towards Hegel, German idealism and a break with the rest of the Young Hegelians. Marx stood Hegel on his head in his own view of his role by turning the idealistic dialectic into a materialistic one in proposing that material circumstances shape ideas instead of the other way around. In this, Marx was following the lead of Feuerbach. His theory of alienation

Karl Marx's theory of alienation describes the separation and estrangement of people from their work, their wider world, their human nature, and their selves. Alienation is a consequence of the division of labour in a capitalist society, wher ...

, developed in the ''Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844'' (published in 1932), inspired itself from Feuerbach's critique of the alienation of man in God through the objectivation of all his inherent characteristics (thus man projected on God all qualities which are in fact man's own quality which defines human nature

Human nature comprises the fundamental dispositions and characteristics—including ways of Thought, thinking, feeling, and agency (philosophy), acting—that humans are said to have nature (philosophy), naturally. The term is often used to denote ...

). Marx also criticized Feuerbach for being insufficiently materialistic—as Stirner himself had point out—and explained that the alienation described by the Young Hegelians was in fact the result of the structure of the economy itself. Furthermore, he criticized Feuerbach's conception of human nature in his sixth thesis on Feuerbach as an abstract "kind" which incarnated itself in each singular individual: "Feuerbach resolves the essence of religion

Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...

into the essence of man human nature But the essence of man is no abstraction inherent in each single individual. In reality, it is the ensemble of the social relations". Thereupon, instead of founding itself on the singular, concrete individual subject as did classic philosophy, including contractualism

Contractualism is a term in philosophy which refers either to a family of political theories in the social contract tradition (when used in this sense, the term is an umbrella term for all social contract theories that include contractarianism), ...

(Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

, John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

and Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Republic of Geneva, Genevan philosopher (''philosophes, philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment through ...

), but also political economy

Political or comparative economy is a branch of political science and economics studying economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and national economies) and their governance by political systems (e.g. law, institutions, and government). Wi ...

, Marx began with the totality of social relations: labour, language and all which constitute our human existence. He claimed that individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

was an essence the result of commodity fetishism

In Marxist philosophy, commodity fetishism is the perception of the economic relationships of production and exchange as relationships among things (money and merchandise) rather than among people. As a form of Reification (Marxism), reificati ...

or alienation. Although some critics have claimed that meant that Marx enforced a strict social determinism

Social determinism is the theory that social interactions alone determine individual behavior (as opposed to biological or objective factors).

A social determinist would only consider social dynamics like customs, cultural expectations, educatio ...

which destroyed the possibility of free will

Free will is generally understood as the capacity or ability of people to (a) choice, choose between different possible courses of Action (philosophy), action, (b) exercise control over their actions in a way that is necessary for moral respon ...

, Marx's philosophy in no way can be reduced to such determinism as his own personal trajectory makes clear.

In 1844–1845, when Marx was starting to settle his account with Hegel and the Young Hegelians in his writings, he critiqued the Young Hegelians for limiting the horizon of their critique to religion

Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...

and not taking up the critique of the state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

and civil society

Civil society can be understood as the "third sector" of society, distinct from government and business, and including the family and the private sphere.theory of alienation

Karl Marx's theory of alienation describes the separation and estrangement of people from their work, their wider world, their human nature, and their selves. Alienation is a consequence of the division of labour in a capitalist society, wher ...

), Marx's thinking could have taken at least three possible courses, namely the study of law, religion and the state, the study of natural philosophy and the study of political economy. He chose the last as the predominant focus of his studies for the rest of his life, largely on account of his previous experience as the editor of the newspaper on whose pages he fought for freedom of expression against Prussian censorship and made a rather idealist, legal defense for the Moselle peasants' customary right of collecting wood in the forest (this right was at the point of being criminalized and privatized by the state). It was Marx's inability to penetrate beneath the legal and polemical surface of the latter issue to its materialist, economic and social roots that prompted him to critically study political economy.

English and Scottish political economy

Political economy predates the 20th century division of the two disciplines ofpolitics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

and economics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

, treating social relations and economic relations as interwoven. Marx built on and critiqued the most well-known political economists of his day, the British classical political economists.

Adam Smith and David Ricardo

FromAdam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

came the idea that the grounds of property is labour. Marx critiqued Smith and David Ricardo

David Ricardo (18 April 1772 – 11 September 1823) was a British political economist, politician, and member of Parliament. He is recognized as one of the most influential classical economists, alongside figures such as Thomas Malthus, Ada ...

for not realizing that their economic concepts reflected specifically capitalist institutions, not innate natural properties of human society; and therefore could not be applied unchanged to all societies. He proposed a systematic correlation between labour-values and money prices. He claimed that the source of profits under capitalism is value added by workers not paid out in wages. This mechanism operated through the distinction between labour power

Labour power (; ) is the capacity to work, a key concept used by Karl Marx in his critique of capitalist political economy. Marx distinguished between the capacity to do the work, i.e. labour power, and the physical act of working, i.e. labour. ...

, which workers freely exchanged for their wages; and labour, over which asset-holding capitalists thereby gained control.

This practical and theoretical distinction was Marx's primary insight and allowed him to develop the concept of surplus value

In Marxian economics, surplus value is the difference between the amount raised through a sale of a product and the amount it cost to manufacture it: i.e. the amount raised through sale of the product minus the cost of the materials, plant and ...

, which distinguished his works from that of Smith and Ricardo. Workers create enough value during a short period of the working day to pay their wages for that day (necessary labour), yet they continue to work for several more hours and continue to create value (surplus labour

Surplus labor () is a concept used by Karl Marx in his critique of political economy. It means labor performed in excess of the labor necessary to produce the means of livelihood of the worker ("necessary labor"). The "surplus" in this context mea ...

). This value is not returned to them, but appropriated by the capitalists (the bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted wi ...

). Thus, it is not the capitalist ruling class that creates wealth, but the workers—the capitalists then appropriating this wealth to themselves. Some of Marx's insights were seen in a rudimentary form by the Ricardian socialist

Ricardian socialism is a branch of classical economic thought based upon the work of the economist David Ricardo (1772–1823). Despite Ricardo being a capitalist economist, the term is used to describe economists in the 1820s and 1830s who dev ...

school). He developed this theory of exploitation in , a dialectical investigation into the forms value relations take.

Marx's theory of business cycles; of economic growth and development, especially in two sector models; and of the declining rate of profit, or crisis theory

Crisis theory, concerning the causes and consequences of the tendency for the rate of profit to fall in a capitalist system, is associated with Marxian critique of political economy, and was further popularised through Marxist economics.

His ...

are other important elements of Marx's political economy. Marx later made tentative movements towards econometric

Econometrics is an application of statistical methods to economic data in order to give empirical content to economic relationships. M. Hashem Pesaran (1987). "Econometrics", '' The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics'', v. 2, p. 8 p. 8� ...

investigations of his ideas, but the necessary statistical

Statistics (from German language, German: ', "description of a State (polity), state, a country") is the discipline that concerns the collection, organization, analysis, interpretation, and presentation of data. In applying statistics to a s ...

techniques of national accounting only emerged in the following century. In any case, it has proved difficult to adapt Marx's economic concepts, which refer to social relations, to measurable aggregated stocks and flows. In recent decades, a loose "quantitative" school of Marxist economists has emerged. While it may be impossible to find exact measures of Marx's variables from price data, approximations of basic trends are possible.

French socialism

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher ('' philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects ...

was one of the first modern writers to seriously attack the institution of private property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental Capacity (law), legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property, which is owned by a state entity, and from Collective ownership ...

and therefore is sometimes considered a forebear of modern socialism and communism, though Marx rarely mentions Rousseau in his writings. He argued that the goal of government should be to secure freedom

Freedom is the power or right to speak, act, and change as one wants without hindrance or restraint. Freedom is often associated with liberty and autonomy in the sense of "giving oneself one's own laws".

In one definition, something is "free" i ...

, equality

Equality generally refers to the fact of being equal, of having the same value.

In specific contexts, equality may refer to:

Society

* Egalitarianism, a trend of thought that favors equality for all people

** Political egalitarianism, in which ...

and justice

In its broadest sense, justice is the idea that individuals should be treated fairly. According to the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', the most plausible candidate for a core definition comes from the ''Institutes (Justinian), Inst ...

for all within the state, regardless of the will of the majority. From Rousseau came the idea of egalitarian democracy.

Charles Fourier and Henri de Saint-Simon

In 1833,France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

was experiencing a number of social problems arising out of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

. A number of sweeping plans of reform were developed by thinkers on the left

Left may refer to:

Music

* ''Left'' (Hope of the States album), 2006

* ''Left'' (Monkey House album), 2016

* ''Left'' (Helmet album), 2023

* "Left", a song by Nickelback from the album ''Curb'', 1996

Direction

* Left (direction), the relativ ...

. Among the more grandiose were the plans of Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier (; ; 7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker, and one of the founders of utopian socialism. Some of his views, held to be radical in his lifetime, have be ...

and the followers of Henri de Saint-Simon

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, Comte de Saint-Simon (; ; 17 October 1760 – 19 May 1825), better known as Henri de Saint-Simon (), was a French political, economic and socialist theorist and businessman whose thought had a substantial influence on po ...

. Fourier wanted to replace modern cities with utopian communities while the Saint-Simonians advocated directing the economy by manipulating credit. Although these programs did not have much support, they did expand the political and social imagination of their contemporaries, including Marx.

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, ; ; 1809 – 19 January 1865) was a French anarchist, socialist, philosopher, and economist who founded mutualist philosophy and is considered by many to be the "father of anarchism". He was the first person to ca ...

participated in the February 1848 uprising and the composition of what he termed the first republican proclamation of the new republic. However, he had misgivings about the new government because it was pursuing political reform at the expense of the socio-economic reform, which Proudhon considered basic. Proudhon published his own perspective for reform, , in which he laid out a program of mutual financial cooperation among workers. He believed this would transfer control of economic relations from capitalists and financiers to workers. It was Proudhon's book '' What Is Property?'' that convinced the young Marx that private property should be abolished.

In one of his first works, ''The Holy Family'', Marx said: "Not only does Proudhon write in the interest of the proletarians, he is himself a proletarian, an ouvrier. His work is a scientific manifesto of the French proletariat". However, Marx disagreed with Proudhon's anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

and later published vicious criticisms of Proudhon. Marx wrote ''The Poverty of Philosophy'' as a refutation of Proudhon's '' The Philosophy of Poverty'' (1847). In his socialism, Proudhon was followed by Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin. Sometimes anglicized to Michael Bakunin. ( ; – 1 July 1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist. He is among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major figure in the revolutionary socialist, s ...

. After Bakunin's death, his libertarian socialism

Libertarian socialism is an anti-authoritarian and anti-capitalist political current that emphasises self-governance and workers' self-management. It is contrasted from other forms of socialism by its rejection of state ownership and from other ...

diverged into anarcho-communism

Anarchist communism is a far-left political ideology and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private real property but retention of personal property and collectively-owned items, goods, and se ...

and collectivist anarchism, with notable proponents such as Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist and geographer known as a proponent of anarchist communism.

Born into an aristocratic land-owning family, Kropotkin attended the Page Corps and later s ...

and Joseph Déjacque.

Other influences

Lewis H. Morgan

Lewis Henry Morgan

Lewis Henry Morgan (November 21, 1818 – December 17, 1881) was a pioneering American anthropologist and social theorist who worked as a railroad lawyer. He is best known for his work on kinship and social structure, his theories of social e ...

's descriptions of "communism in living" as practiced by the Haudenosaunee

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

of North America, through research enabled by and coauthored with Ely S. Parker, had a large influence on the work and political philosophy of Marx and Engels. Though the belief of this "primitive communism

Primitive communism is a way of describing the gift economies of hunter-gatherers throughout history, where resources and property hunted or gathered are shared with all members of a group in accordance with individual needs. In political sociolo ...

" as based on Morgan's work is flawed due to Morgan's misunderstandings of Haudenosaunee society and his, since proven wrong, theory of social evolution.; ; ; ; ; ; Marx wrote a collection of notebooks from his reading of Morgan but did not develop them in to published works before his death.

Friedrich Engels

Marx's revision of

Marx's revision of Hegelianism

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealism, German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political phi ...

was also influenced by Engels' 1845 book, ''The Condition of the Working Class in England

''The Condition of the Working Class in England'' () is an 1845 book by the German philosopher Friedrich Engels, a study of the industrial working class in Victorian England. Engels' first book, it was originally written in German; an English t ...

'', which led Marx to conceive of the historical dialectic in terms of class conflict

In political science, the term class conflict, class struggle, or class war refers to the economic antagonism and political tension that exist among social classes because of clashing interests, competition for limited resources, and inequali ...

and to see the modern working class as the most progressive force for revolution. Thereafter, Marx and Engels worked together for the rest of Marx's life so that the collected works of Marx and Engels are generally published together, almost as if the output of one person. Important publications, such as ''The German Ideology'' and ''The Communist Manifesto'', were joint efforts. Engels says that "I cannot deny that both before and during my 40 years' collaboration with Marx I had a certain independent share in laying the foundation of the theory, and more particularly in its elaboration". However, he adds:

Charles Darwin

In late November 1859, Engels acquired one of the first 1,250 copies ofCharles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's ''The Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

'' and then he sent a letter to Marx telling: "Darwin, by the way, whom I'm just reading now, is absolutely splendid". The following year, Marx wrote back to his colleague telling that this book contained the natural-history foundation of the historical materialism viewpoint:

Next month, Marx wrote to his friend Ferdinand Lassalle:

By June 1862, Marx had already read ''The Origin of Species'' again, finding a connection between Thomas Robert Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English economist, cleric, and scholar influential in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

's work and Darwin's ideas:

In 1863, he quoted Darwin again within his ''Theories of Surplus Value

''Theories of Surplus Value'' () is a draft manuscript written by Karl Marx between January 1862 and July 1863. It is mainly concerned with the Western Europe, Western European theorizing about ''Mehrwert'' (added value or surplus value) from abo ...

'' (2:121), saying: "In his splendid work, Darwin did not realize that by discovering the 'geometrical progression' in the animal and plant kingdom, he overthrew Malthus theory".

Having read about Darwinian evolution along with Marx, German communist Wilhelm Liebknecht

Wilhelm Martin Philipp Christian Ludwig Liebknecht (; 29 March 1826 – 7 August 1900) was a German socialist activist and politician. He was one of the principal founders of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).Richard Weikart points out that Marx had started to attend "a series of lectures by

"Marx of Respect"

(2000). Darwin wrote back to Marx in October, thanking him for having sent his work and saying "I believe that we both earnestly desire the extension of knowledge". According to scholar Paul Heyer, "Marx believed that Darwin provided a materialistic perspective compatible with his own", although being applied in another context. In his book ''Darwin in Russian Thought'' (1989), Alexander Vucinich claims that "Engels gave Marx credit for extending Darwin's theory to the study of the inner dynamics and change in human society".

Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist who specialized in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

on evolution".

In August 1866, Marx referred to Pierre Trémaux's (1865) in another letter to Engels as "a very important advance over Darwin". He went further to claim that "in its historical and political application" the book was "much more important and copious than Darwin".

Although there is no mention of Darwin in ''The Communist Manifesto'' (published eleven years prior to ''The Origin of Species''), Marx includes two explicit references to Darwin and evolution in the second edition of , in two footnotes where he relates Darwin's theory to his opinion about production and technology development. In the Volume I, Chapter 14: "The Detail Labourer and his implements", Section 2, Marx referred to Darwin's ''Origin of Species'' as an "epoch-making work" while in Chapter 15, Section I took on the comparison of organs of plants to animals and tools.I. Bernard Cohen (1985), Revolution in Science, Harvard University Press, p. 345.

In a book review of the first volume of , Engels wrote that Marx was "simply striving to establish the same gradual process of transformation demonstrated by Darwin in natural history as a law in the social field". In this line of thought, several authors such as William F. O'Neill, have seen that "Marx describes history as a social Darwinist

Charles Darwin, after whom social Darwinism is named

Social Darwinism is a body of pseudoscientific theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economic ...

'survival of the fittest

"Survival of the fittest" is a phrase that originated from Darwinian evolutionary theory as a way of describing the mechanism of natural selection. The biological concept of fitness is defined as reproductive success. In Darwinian terms, th ...

' dominated by the conflict between different social classes" and moving to a future in which social conflict will ultimately disappear in a 'classless society'" while some Marxists try to dissociate Marx from social Darwinism.

Nonetheless, it is evident that Marx had a strong liking for Darwin's theory and a clear influence on his thought. Furthermore, when the second German edition of , was published (two years after the publication of Darwin's '' Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex''), Marx sent Darwin a copy of his book with the following words:Carter, Richard"Marx of Respect"

(2000). Darwin wrote back to Marx in October, thanking him for having sent his work and saying "I believe that we both earnestly desire the extension of knowledge". According to scholar Paul Heyer, "Marx believed that Darwin provided a materialistic perspective compatible with his own", although being applied in another context. In his book ''Darwin in Russian Thought'' (1989), Alexander Vucinich claims that "Engels gave Marx credit for extending Darwin's theory to the study of the inner dynamics and change in human society".

Classical materialism

Marx was influenced by classical materialism, especiallyEpicurus

Epicurus (, ; ; 341–270 BC) was an Greek philosophy, ancient Greek philosopher who founded Epicureanism, a highly influential school of philosophy that asserted that philosophy's purpose is to attain as well as to help others attain tranqui ...

(to whom Marx dedicated his thesis "Difference of Natural Philosophy Between Democritus and Epicurus", 1841) for his materialism and theory of clinamen

Clinamen (; plural ''clinamina'', derived from , to incline) is the unpredictable swerve of atoms in the atomistic doctrine of Epicurus. This swerving, according to Lucretius, provides the " free will which living things throughout the world have" ...

which opened up a realm of liberty.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Influences On Karl Marx Karl Marx MarxismMarx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...