Ilya Ehrenburg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ilya Grigoryevich Ehrenburg (, ; – August 31, 1967) was a Soviet writer, revolutionary, journalist and historian.

Ehrenburg was among the most prolific and notable authors of the Soviet Union; he published around one hundred titles. He became known first and foremost as a novelist and a journalist – in particular, as a reporter in three wars (

In the aftermath of the

In the aftermath of the

On 21 September 1948, at the behest of

On 21 September 1948, at the behest of

Ehrenburg died in 1967 of

Ehrenburg died in 1967 of

''To Remember''

at

First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

and the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

). His incendiary articles calling for violence against Germans during the ''Great Patriotic War

The Eastern Front, also known as the Great Patriotic War (term), Great Patriotic War in the Soviet Union and its successor states, and the German–Soviet War in modern Germany and Ukraine, was a Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II ...

'' won him a huge following among front-line Soviet soldiers, but also caused much controversy due to their perceived anti-German sentiment

Anti-German sentiment (also known as anti-Germanism, Germanophobia or Teutophobia) is fear or dislike of Germany, its Germans, people, and its Culture of Germany, culture. Its opposite is Germanophile, Germanophilia.

Anti-German sentiment main ...

. Ehrenburg later clarified that his writings were about "German aggressors who set foot on Soviet soil with weapons", not the whole German people.

The novel '' The Thaw'' gave its name to an entire era of Soviet politics, namely, the liberalization which occurred after the death of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

. Ehrenburg's travel writing also had great resonance, and to an arguably greater extent, so did his memoir

A memoir (; , ) is any nonfiction narrative writing based on the author's personal memories. The assertions made in the work are thus understood to be factual. While memoir has historically been defined as a subcategory of biography or autob ...

''People, Years, Life'', which may be his best known and most discussed work. The '' Black Book'', edited by him and Vasily Grossman, has special historical significance, it describes the Holocaust in the Soviet Union, the genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

which was committed against Soviet citizens of Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

ancestry by the Nazis; It was denounced as "anti-Soviet" and banned from publication. It was first published in Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

in 1980.

In addition, Ehrenburg wrote a succession of works of poetry.

Life and work

Ilya Ehrenburg was born inKiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

, in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

to a Lithuanian–Jewish family; his father was an engineer. Ehrenburg's household was not religiously observant; he came into contact with the religious practices of Judaism only through his maternal grandfather. Ehrenburg never practiced Judaism. He learned no Yiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

, although he edited the '' Black Book'', which was written in Yiddish. He considered himself a Russian and, later, a Soviet citizen, and wrote in Russian even during his many years abroad. Ehrenburg also took strong public positions against antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

, and left all his papers to Israel's Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem (; ) is Israel's official memorial institution to the victims of Holocaust, the Holocaust known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (). It is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Jews who were murdered; echoing the stories of the ...

.

When Ehrenburg was four years old, the family moved to Moscow, where his father had been hired as director of a brewery. At school, he met Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (; rus, Николай Иванович Бухарин, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɪˈvanəvʲɪdʑ bʊˈxarʲɪn; – 15 March 1938) was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and Marxist theorist. A prominent Bolshevik ...

, who was two grades above him. The two remained friends until Bukharin's execution in 1938 during the Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

.

In the aftermath of the

In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, t ...

, both Ehrenburg and Bukharin got involved in illegal activities of the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

organisation. In 1908, when Ehrenburg was seventeen years old, the tsarist secret police (Okhrana

The Department for the Protection of Public Safety and Order (), usually called the Guard Department () and commonly abbreviated in modern English sources as the Okhrana ( rus , Охрана, p=ɐˈxranə, a=Ru-охрана.ogg, t= The Guard) w ...

) arrested him for five months. He was beaten up and lost some teeth. Finally he was allowed to go abroad and chose Paris for his exile.

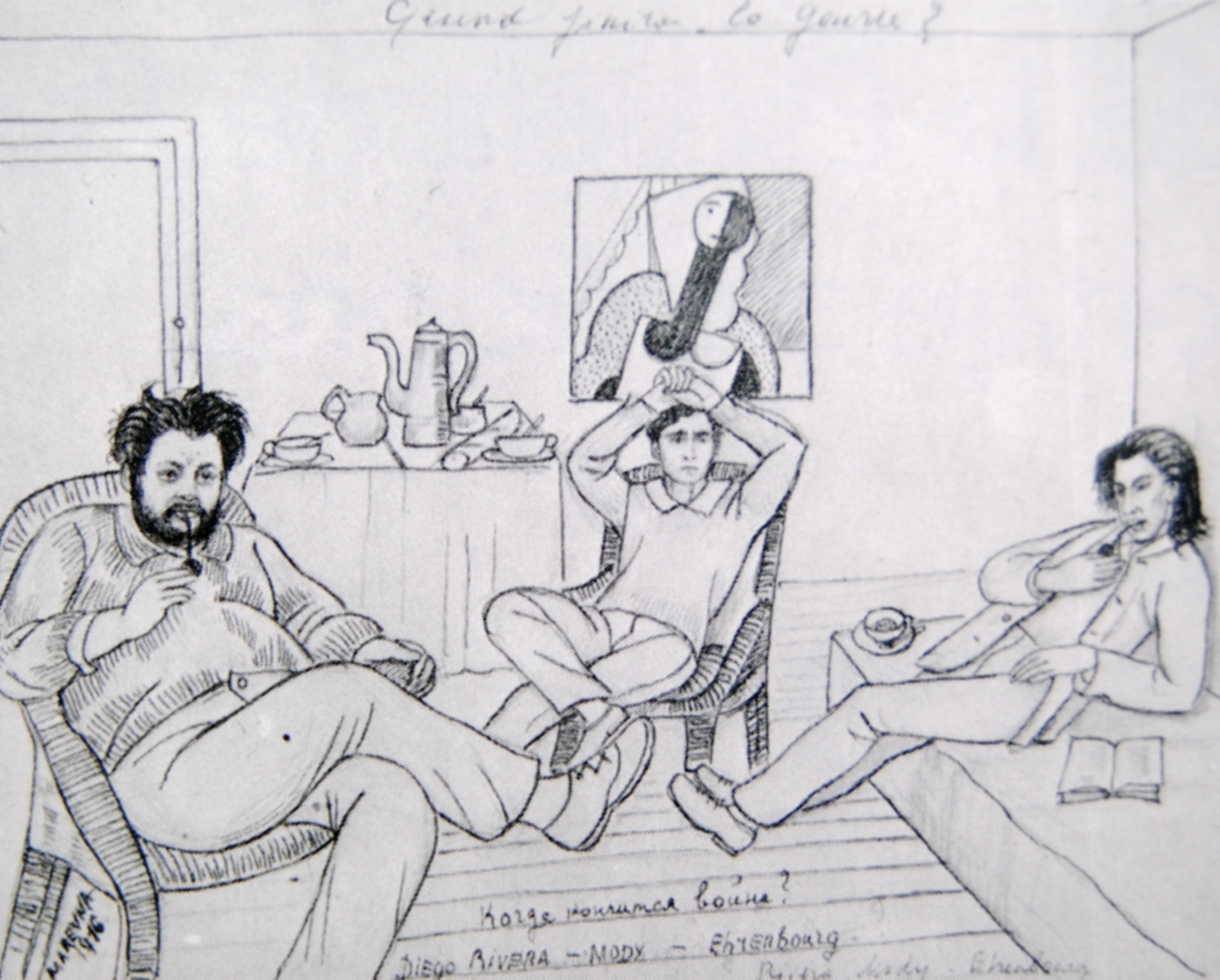

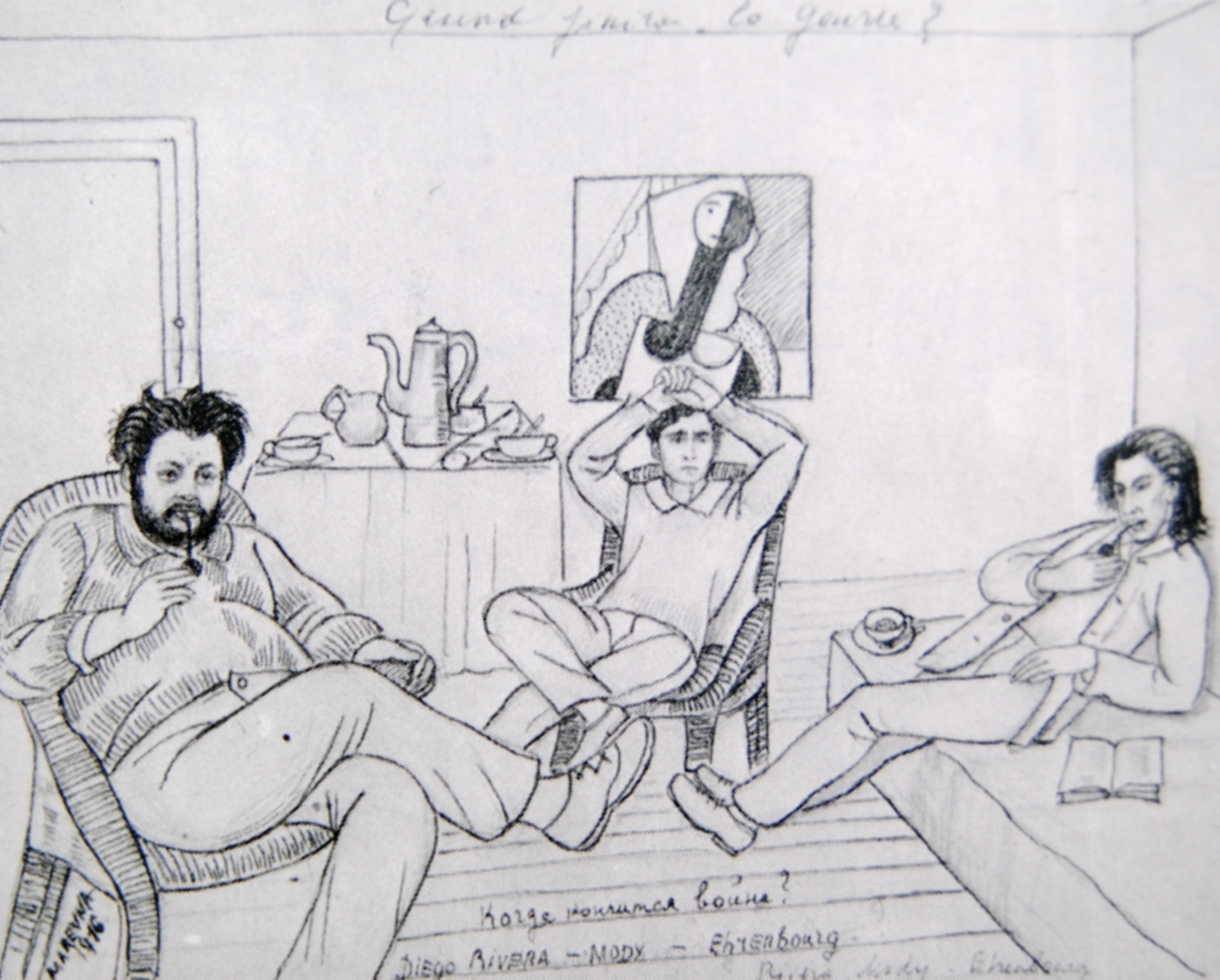

In Paris, he started to work in the Bolshevik organisation, meeting Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

and other prominent exiles. But soon he left these circles and the party. Ehrenburg became attached to the bohemian life in the Paris quarter of Montparnasse

Montparnasse () is an area in the south of Paris, France, on the left bank of the river Seine, centred at the crossroads of the Boulevard du Montparnasse and the Rue de Rennes, between the Rue de Rennes and boulevard Raspail. It is split betwee ...

. He began to write poems, regularly visited the cafés of Montparnasse and got acquainted with a lot of artists, especially Pablo Picasso

Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, Ceramic art, ceramicist, and Scenic ...

, Diego Rivera

Diego Rivera (; December 8, 1886 – November 24, 1957) was a Mexican painter. His large frescoes helped establish the Mexican muralism, mural movement in Mexican art, Mexican and international art.

Between 1922 and 1953, Rivera painted mural ...

, Jules Pascin

Julius Mordecai Pincas (March 31, 1885 – June 2, 1930), known as Pascin (, erroneously or ), Jules Pascin, also known as the "Prince of Montparnasse", was a Bulgarian artist of the School of Paris, known for his paintings and drawings. He ...

, and Amedeo Modigliani

Amedeo Clemente Modigliani (; ; 12 July 1884 – 24 January 1920) was an Italian painter and sculptor of the École de Paris who worked mainly in France. He is known for portraits and nudes in a modern art, modern style characterized by a surre ...

. Foreign writers whose works Ehrenburg translated included those of Francis Jammes

Francis Jammes (; 2 December 1868, in Tournay, Hautes-Pyrénées, Tournay – 1 November 1938, in Hasparren) was a French and European poet. He spent most of his life in his native region of Béarn and the Northern Basque Country, Basque Country ...

.

During World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Ehrenburg became a war correspondent

A war correspondent is a journalist who covers stories first-hand from a war, war zone.

War correspondence stands as one of journalism's most important and impactful forms. War correspondents operate in the most conflict-ridden parts of the wor ...

for a St. Petersburg newspaper. He wrote a series of articles about the mechanized war that later on were also published as a book (''The Face of War''). His poetry now also concentrated on subjects of war and destruction, as in ''On the Eve'', his third lyrical book. Nikolai Gumilev, a famous symbolistic poet, wrote favourably about Ehrenburg's progress in poetry.

In 1917, after the revolution, Ehrenburg returned to Russia. At that time he tended to oppose the Bolshevik policy, being shocked by the constant atmosphere of violence. He wrote a poem called "Prayer for Russia" which compared the storming of the Winter Palace to rape. In 1920 Ehrenburg went to Kiev where he experienced four different regimes in the course of one year: the Germans, the Cossacks, the Bolsheviks, and the White Army. After antisemitic pogrom

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of Massacre, massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century Anti-Jewis ...

s, he fled to Koktebel on the Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

peninsula where his old friend from Paris days, Maximilian Voloshin, had a house. Finally, Ehrenburg returned to Moscow, where he soon was arrested by the Cheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, Всероссийская чрезвычайная комиссия, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fsʲɪrɐˈsʲijskəjə tɕrʲɪzvɨˈtɕæjnəjə kɐˈmʲisʲɪjə, links=yes), ...

but freed after a short time.

He became a Soviet cultural activist and journalist who spent much time abroad as a writer. He wrote avant-garde

In the arts and literature, the term ''avant-garde'' ( meaning or ) identifies an experimental genre or work of art, and the artist who created it, which usually is aesthetically innovative, whilst initially being ideologically unacceptable ...

picaresque novel

The picaresque novel ( Spanish: ''picaresca'', from ''pícaro'', for ' rogue' or 'rascal') is a genre of prose fiction. It depicts the adventures of a roguish but appealing hero, usually of low social class, who lives by his wits in a corrup ...

s and short stories popular in the 1920s, often set in Western Europe (''The Extraordinary Adventures of Julio Jurenito and his Disciples'' (1922), ''Thirteen Pipes''). Ehrenburg continued to write philosophical poetry, using more freed rhythms than in the 1910s. In 1929 he published ''The Life of the Automobile'', a communist variant of the it-narrative genre.

In 1935, Ehrenburg attended the first International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture, which opened in Paris in June. He had written a pamphlet which said, among other things, that surrealists shunned work, favouring parasitism

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives (at least some of the time) on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The en ...

, and that they endorsed " onanism, pederasty

Pederasty or paederasty () is a sexual relationship between an adult man and an adolescent boy. It was a socially acknowledged practice in Ancient Greece and Rome and elsewhere in the world, such as Pre-Meiji Japan.

In most countries today, ...

, fetishism

A fetish is an object believed to have supernatural powers, or in particular, a human-made object that has power over others. Essentially, fetishism is the attribution of inherent non-material value, or powers, to an object. Talismans and amulet ...

, exhibitionism

Exhibitionism is the act of exposing in a public or semi-public context one's intimate parts – for example, the breasts, genitals or buttocks. As used in psychology and psychiatry, it is substantially different. It refers to an uncontrolla ...

, and even sodomy

Sodomy (), also called buggery in British English, principally refers to either anal sex (but occasionally also oral sex) between people, or any Human sexual activity, sexual activity between a human and another animal (Zoophilia, bestiality). I ...

". André Breton

André Robert Breton (; ; 19 February 1896 – 28 September 1966) was a French writer and poet, the co-founder, leader, and principal theorist of surrealism. His writings include the first ''Surrealist Manifesto'' (''Manifeste du surréalisme'') ...

— along with all fellow surrealists — felt insulted and accosted Ehrenburg on the street and slapped him several times, which resulted in surrealists being expelled from the Congress.

Spanish Civil War

As a friend of many of the European Left, Ehrenburg was frequently allowed by Stalin to visit Europe and to campaign for peace and socialism. He arrived in Spain in late August 1936 as an ''Izvestia

''Izvestia'' ( rus, Известия, r=Izvestiya, p=ɪzˈvʲesʲtʲɪjə, "The News") is a daily broadsheet newspaper in Russia. Founded in February 1917, ''Izvestia'', which covered foreign relations, was the organ of the Supreme Soviet of th ...

'' correspondent and was involved in propaganda and military activity as well as reporting. In July 1937 he attended the Second International Writers' Congress, the purpose of which was to discuss the attitude of intellectuals to the war, held in Valencia

Valencia ( , ), formally València (), is the capital of the Province of Valencia, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, the same name in Spain. It is located on the banks of the Turia (r ...

, Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

, and Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

and attended by many writers including André Malraux

Georges André Malraux ( ; ; 3 November 1901 – 23 November 1976) was a French novelist, art theorist, and minister of cultural affairs. Malraux's novel ''La Condition Humaine'' (''Man's Fate'') (1933) won the Prix Goncourt. He was appointed ...

, Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway ( ; July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer and journalist. Known for an economical, understated style that influenced later 20th-century writers, he has been romanticized fo ...

, Stephen Spender

Sir Stephen Harold Spender (28 February 1909 – 16 July 1995) was an English poet, novelist and essayist whose work concentrated on themes of social injustice and the class struggle. He was appointed U.S. Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry ...

, and Pablo Neruda

Pablo Neruda ( ; ; born Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto; 12 July 190423 September 1973) was a Chilean poet-diplomat and politician who won the 1971 Nobel Prize in Literature. Neruda became known as a poet when he was 13 years old an ...

.

World War II

Ehrenburg was offered a column in '' Krasnaya Zvezda'' (theRed Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

newspaper) days after the German invasion of the Soviet Union. During the war, he published more than 2,000 articles in Soviet newspapers. He saw the Great Patriotic War

The Eastern Front, also known as the Great Patriotic War (term), Great Patriotic War in the Soviet Union and its successor states, and the German–Soviet War in modern Germany and Ukraine, was a Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II ...

as a dramatic contest between good and evil. In his articles, moral and life-affirming Red Army soldiers faced off against a dehumanized German enemy. In 1943, Ehrenburg, working with the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee

The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, abbreviated as JAC, was an organization that was created in the Soviet Union during World War II to influence international public opinion and organize political and material support for the Soviet fight against ...

, began to collect material for what would become '' The Black Book of Soviet Jewry'', documenting The Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

. In a December 1944 article in ''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, 'Truth') is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most in ...

'', Ehrenburg declared that the Germans' greatest crime was the murder of six million Jews.

His incendiary articles calling for vengeance against the German enemy won him a huge following among front-line Soviet soldiers, who sent him much fan mail

Fan mail is mail sent to a public figure, especially a celebrity, by their admirers or "fan (person), fans". In return for a fan's support and admiration, public figures may send an autographed poster, photo, reply letter, or note thanking the ...

. As a consequence, he is one of many Soviet writers, along with Konstantin Simonov

Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov, born Kirill Mikhailovich Simonov (, – 28 August 1979), was a Soviet author, war poet, playwright and wartime correspondent,Константин Михайлович Симонов // " Литературна� ...

and Alexey Surkov, who many have accused of " endingtheir literary talents to the hate campaign" against Germans.Orlando Figes

Orlando Guy Figes (; born 20 November 1959) is a British and German historian and writer. He was a professor of history at Birkbeck College, University of London, where he was made Emeritus Professor on his retirement in 2022.

Figes is known f ...

''The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia'', 2007, , p. 414. Austrian historian Arnold Suppan argued that Ehrenburg "agitated in the style of Nazi racist ideology", with statements such as:

This pamphlet, titled "Kill", was written during the Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad ; see . rus, links=on, Сталинградская битва, r=Stalingradskaya bitva, p=stəlʲɪnˈɡratskəjə ˈbʲitvə. (17 July 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II, ...

. Ehrenburg later accompanied the Soviet forces during the East Prussian Offensive and criticized the indiscriminate violence against German civilians, for which he was reprimanded by Stalin. However, his previous writings had already been interpreted as license for atrocities against German civilians during the Soviet invasion of Germany in 1945. Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician and philologist who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief Propaganda in Nazi Germany, propagandist for the Nazi Party, and ...

accused Ehrenburg of advocating the rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault involving sexual intercourse, or other forms of sexual penetration, carried out against a person without consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or against a person ...

of German women. However, Ehrenburg denied this and historian Antony Beevor

Sir Antony James Beevor, (born 14 December 1946) is a British military historian. He has published several popular historical works, mainly on the Second World War, the Spanish Civil War, and most recently the Russian Revolution and Civil War. ...

claims that it was a Nazi fabrication. In January 1945, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

stated that "Stalin's court lackey, Ilya Ehrenburg, declares that the German people must be exterminated". After criticism by Georgy Aleksandrov

Georgy Fedorovich Aleksandrov (Russian: Гео́ргий Фёдорович Алекса́ндров; 22 March 1908 – 7 July 1961) was a Soviet people, Soviet politician and Marxist philosopher.

Biography Childhood and education

Aleksandrov was ...

in ''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, 'Truth') is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most in ...

'' in April 1945, Ehrenburg responded that he never meant wiping out the German people

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...

, but only German aggressors who set foot on Soviet soil with weapons, because "we are not Nazis who fight with civilians”. Ehrenburg fell into disgrace at that time and it is estimated that Aleksandrov's article was a signal of change in Stalin's policy towards Germany.

The 'Anti-Cosmopolitan' Campaign

On 21 September 1948, at the behest of

On 21 September 1948, at the behest of Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

members Lazar Kaganovich

Lazar Moiseyevich Kaganovich (; – 25 July 1991) was a Soviet politician and one of Joseph Stalin's closest associates.

Born to a Jewish family in Ukraine, Kaganovich worked as a shoemaker and joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party ...

and Georgy Malenkov

Georgy Maximilianovich Malenkov (8 January 1902 O.S. 26 December 1901">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 26 December 1901ref name=":6"> – 14 January 1988) was a Soviet politician who br ...

, Ehrenburg published an article in ''Pravda'' which signified Stalin's absolute political break with Israel, which he had been supporting through enormous shipments of Czech arms. After this break with Israel, hundreds of Jews became targets of the so-called anti-cosmopolitan campaign

The anti-cosmopolitan campaign (, ) was an anti-Western campaign in the Soviet Union which began in late 1948 and has been widely described as a thinly disguised antisemitic purge. A large number of Jews were persecuted as Zionists or rootless co ...

. The chairman of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, Solomon Mikhoels

Solomon (Shloyme) Mikhoels ( lso spelled שלוימע מיכאעלס during the Soviet era , – 13 January 1948) was a Soviet actor and the artistic director of the Moscow State Jewish Theater. Mikhoels served as the chairman of the Jewish ...

, was murdered, and many Soviet Jewish intellectuals were imprisoned or executed.

Ilya Ehrenburg's name was high on a list presented to Stalin by the chief of police, Viktor Abakumov

Viktor Semyonovich Abakumov (; 24 April 1908 – 19 December 1954) was a high-level Soviet security official who from 1943 to 1946 was the head of SMERSH in the USSR People's Commissariat of Defense, and from 1946 to 1951 of the Minister of St ...

, of people selected for arrest. He was accused of having "made attacks on Comrade Stalin" when talking to the French writer André Malraux

Georges André Malraux ( ; ; 3 November 1901 – 23 November 1976) was a French novelist, art theorist, and minister of cultural affairs. Malraux's novel ''La Condition Humaine'' (''Man's Fate'') (1933) won the Prix Goncourt. He was appointed ...

in Spain in 1937. While Stalin agreed to the arrests of most of the names on the list, he put a question mark by Ehrenburg's. It appears that Ehrenburg was allowed to continue publishing and travelling abroad to obscure the anti-Semitic campaign at home. During a press conference in London in 1950, attended by over 200 journalists, he was challenged about the fate of the writers David Bergelson and Itzik Feffer, and said that "If anything unpleasant had happened to them, I would have known", knowing that they were both under arrest. He was accused of informing on his comrades, but there is no evidence to support this theory. In February 1953, he refused to denounce the supposed doctors' plot

The "doctors' plot" () was a Soviet state-sponsored anti-intellectual and anti-cosmopolitan campaign based on a conspiracy theory that alleged an anti-Soviet cabal of prominent medical specialists, including some of Jewish ethnicity, intend ...

and wrote a letter to Stalin opposing collective punishment of Jews.

Postwar writings

Ehrenburg received theStalin Peace Prize

The International Lenin Peace Prize (, ''mezhdunarodnaya Leninskaya premiya mira)'' was a Soviet Union award named in honor of Vladimir Lenin. It was awarded by a panel appointed by the Soviet government, to notable individuals whom the panel ...

in 1948.

In 1954, Ehrenburg published a novel titled '' The Thaw'' that tested the limits of censorship in the post-Stalin Soviet Union. It portrayed a corrupt and despotic factory boss, a "little Stalin", and told the story of his wife, who increasingly feels estranged from him, and the views he represents. In the novel, the spring thaw comes to represent a period of change in the characters' emotional journeys, and when the wife eventually leaves her husband, this coincides with the melting of the snow. Thus, the novel can be seen as a representation of the thaw, and the increased freedom of the writer after the 'frozen' political period under Stalin. In August 1954, Konstantin Simonov

Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov, born Kirill Mikhailovich Simonov (, – 28 August 1979), was a Soviet author, war poet, playwright and wartime correspondent,Константин Михайлович Симонов // " Литературна� ...

attacked ''The Thaw'' in articles published in '' Literaturnaya Gazeta'', arguing that such writings are too dark and do not serve the Soviet state.Orlando Figes

Orlando Guy Figes (; born 20 November 1959) is a British and German historian and writer. He was a professor of history at Birkbeck College, University of London, where he was made Emeritus Professor on his retirement in 2022.

Figes is known f ...

''The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia'', 2007, , pp. 590–591. The novel gave its name to the Khrushchev Thaw

The Khrushchev Thaw (, or simply ''ottepel'')William Taubman, Khrushchev: The Man and His Era, London: Free Press, 2004 is the period from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s when Political repression in the Soviet Union, repression and Censorship in ...

.

Ehrenburg is particularly well known for his memoirs (''People, Years, Life'' in Russian, published with the title ''Memoirs: 1921–1941'' in English), which contain many portraits of interest to literary historians and biographers. In this book, Ehrenburg was the first legal Soviet author to mention positively a lot of names banned under Stalin, including Marina Tsvetaeva

Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva ( rus, Марина Ивановна Цветаева, p=mɐˈrʲinə ɪˈvanəvnə tsvʲɪˈta(j)ɪvə, links=yes; 31 August 1941) was a Russian poet. Her work is some of the most well-known in twentieth-century Russ ...

. At the same time he disapproved of the Russian and Soviet intellectuals who had explicitly rejected communism or defected to the West. He also criticized writers like Boris Pasternak

Boris Leonidovich Pasternak (30 May 1960) was a Russian and Soviet poet, novelist, composer, and literary translator.

Composed in 1917, Pasternak's first book of poems, ''My Sister, Life'', was published in Berlin in 1922 and soon became an imp ...

, author of '' Doctor Zhivago'', for not having been able to understand the course of history.

Ehrenburg's memoirs were criticized by the more conservative faction among the Soviet writers, concentrated around the journal '' Oktyabr''. For example, when the memoirs were published, Vsevolod Kochetov reflected on certain writers who were "burrowing in the rubbish heaps of their crackpot memories". In January 1963, the critic Vladimir Yermilov wrote a long article in ''Izvestia

''Izvestia'' ( rus, Известия, r=Izvestiya, p=ɪzˈvʲesʲtʲɪjə, "The News") is a daily broadsheet newspaper in Russia. Founded in February 1917, ''Izvestia'', which covered foreign relations, was the organ of the Supreme Soviet of th ...

'' in which he picked up on Ehrenburg's admission that he had suspected that innocent people were being arrested in 1937 and 1938 but had "gritted his teeth" in silence.

Yermilov alleged that this proved that Ehrenburg had been in a privileged position in those years but said nothing, when others, less privileged, had spoken out when they believed an innocent person had been arrested. Ehrenburg retorted that he had never been to a single meeting nor read a single article in which anyone had protested about the arrests, whereupon Yermilov accused him of having insulted a "whole generation of Soviet people".

For the contemporary reader though, the work appears to have a distinctly Marxist-Leninist ideological flavor characteristic of a Soviet-era official writer.

He was also active in publishing the works by Osip Mandelstam

Osip Emilyevich Mandelstam (, ; – 27 December 1938) was a Russian and Soviet poet. He was one of the foremost members of the Acmeist school.

Osip Mandelstam was arrested during the repressions of the 1930s and sent into internal exile wi ...

when the latter had been posthumously rehabilitated but still largely unacceptable for censorship. Ehrenburg was also active as a poet till his last days, depicting the events of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

in Europe, the Holocaust and the destinies of Russian intellectuals.

Death and legacy

prostate

The prostate is an male accessory gland, accessory gland of the male reproductive system and a muscle-driven mechanical switch between urination and ejaculation. It is found in all male mammals. It differs between species anatomically, chemica ...

and bladder cancer

Bladder cancer is the abnormal growth of cells in the bladder. These cells can grow to form a tumor, which eventually spreads, damaging the bladder and other organs. Most people with bladder cancer are diagnosed after noticing blood in thei ...

, and was interred in Novodevichy Cemetery

Novodevichy Cemetery () is a cemetery in Moscow. It lies next to the southern wall of the 16th-century Novodevichy Convent, which is the city's third most popular tourist site.

History

The cemetery was designed by Ivan Mashkov and inaugurated ...

in Moscow, where his gravestone is etched with a reproduction of his portrait drawn by his friend Pablo Picasso

Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, Ceramic art, ceramicist, and Scenic ...

.

In 1968, Polish-American writer and journalist S.L. Shneiderman published a Yiddish biography of Ehrenburg, whom he had met in interwar Paris and in Spain. In his biography, Shneiderman defended Ehrenburg from accusations of collaboration with Stalin in the destruction of Soviet Yiddish culture.

English translations

*''The Love of Jeanne Ney'', Doubleday, Doran and Company 1930. *''The Extraordinary Adventures of Julio Jurenito and his Disciples'', Covici Friede, NY, 1930. *''A Soviet Writer Looks at Vienna'', Lawrence, London, 1934. *''The Fall of Paris'', Knopf, NY, 1943. ovel*''The Tempering of Russia'', Knopf, NY, 1944. *''European Crossroad: A Soviet Journalist In the Balkans'', Knopf, NY, 1947. *''The Storm'', Foreign Languages Publishing House, Moscow, 1948. *''The Thaw'', Henry Regnery Company, Chicago, 1955. *''The Ninth Wave'', Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1955. *''The Stormy Life of Lasik Roitschwantz'', Polyglot Library, 1960. *''A Change of Season'', (includes '' The Thaw'' and its sequel ''The Spring''), Knopf, NY, 1962. *''Chekhov, Stendhal and Other Essays'', Knopf, NY, 1963. *''Memoirs: 1921–1941'', World Pub. Co., Cleveland, 1963. *''Life of the Automobile'', URIZEN BOOKS Joachim Neugroeschel translator 1976. *''The Second Day'', Raduga Publishers, Moscow, 1984. *''The Fall of Paris'', Simon Publications, 2002. *''My Paris'', Editions 7, Paris, 2005 "The D.E.Trust", M-Graphics, Boston, 2025References

Sources

* * * * * * Shneiderman, S.L. ''Ilye Erenburg'' ng: Ilya Ehrenburg New York: Yidisher Kempfer, 1968. *Further reading

*External links

* * *''To Remember''

at

Facing History and Ourselves

Facing History & Ourselves is a global non-profit organization founded in 1976. The organization's mission is to "use lessons of history to challenge teachers and their students to stand up to bigotry and hate." The organization is based in Bost ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ehrenburg, Ilya

1891 births

1967 deaths

Writers from Kyiv

People from Kievsky Uyezd

Jewish Ukrainian writers

Jewish writers from the Russian Empire

Soviet Jews

Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members

Old Bolsheviks

Third convocation members of the Soviet of Nationalities

Fourth convocation members of the Soviet of the Union

Fifth convocation members of the Soviet of the Union

Sixth convocation members of the Soviet of Nationalities

Seventh convocation members of the Soviet of Nationalities

Jewish anti-fascists

Jewish poets

Jewish socialists

Jewish writers

20th-century Russian memoirists

Russian male novelists

Soviet novelists

Soviet male writers

20th-century Russian male writers

Russian-language poets

Soviet poets

Russian male poets

Soviet propagandists

Soviet people of the Spanish Civil War

Stalin Peace Prize recipients

Recipients of the Stalin Prize

Recipients of the Order of Lenin

Burials at Novodevichy Cemetery

Soviet memoirists

Russian war correspondents

War correspondents of World War I