Iain MacLeod (other) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

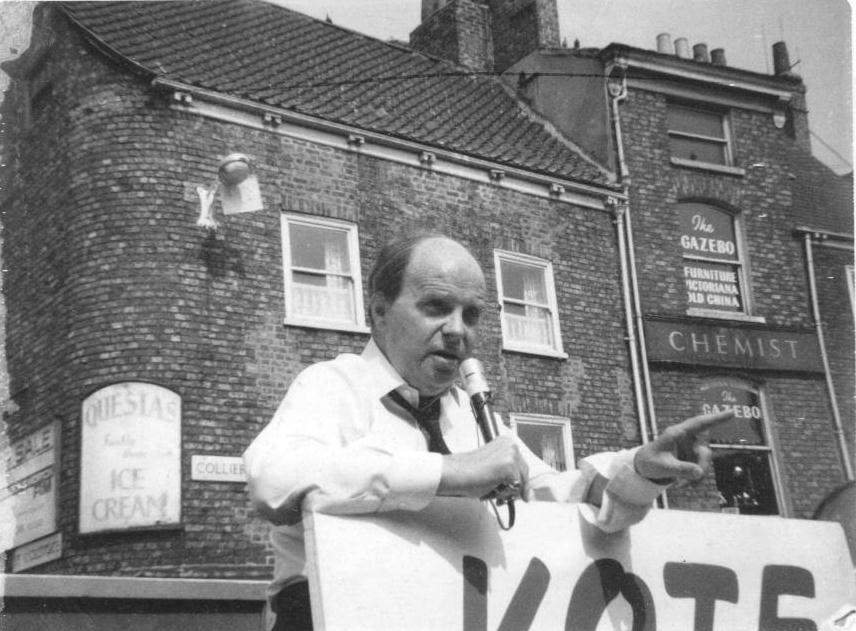

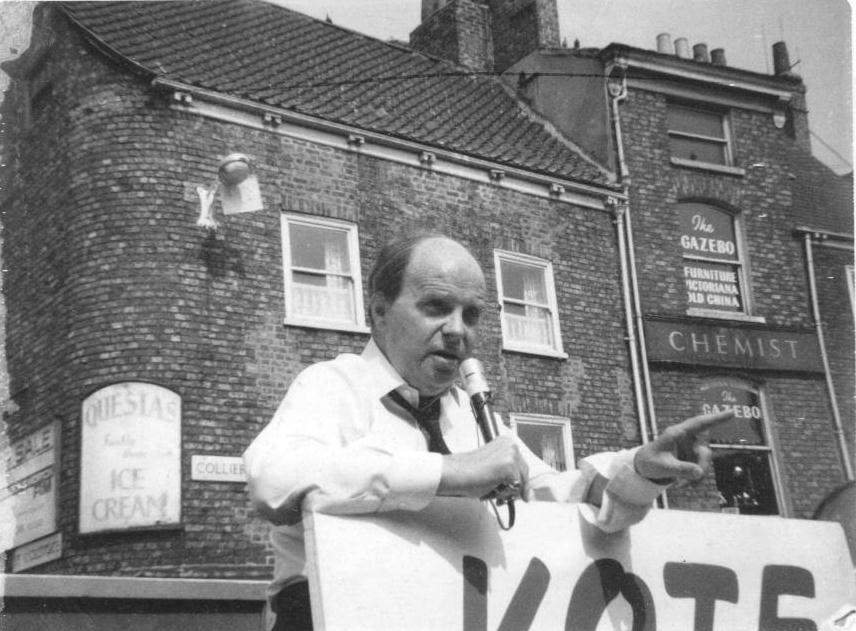

Iain Norman Macleod (11 November 1913 – 20 July 1970) was a British Conservative Party politician.

A playboy and professional

On 20 June 1970, two days after the Conservative Party's unexpected election victory, Macleod was appointed

On 20 June 1970, two days after the Conservative Party's unexpected election victory, Macleod was appointed

Macleod met Evelyn Hester Mason, ''née'' Blois, (1915–1999) in September 1939 whilst he was waiting to be called up for army service and she interviewed him for a job as an ambulance driver. Evelyn was daughter of Rev. Gervase Vanneck Blois, rector of

Macleod met Evelyn Hester Mason, ''née'' Blois, (1915–1999) in September 1939 whilst he was waiting to be called up for army service and she interviewed him for a job as an ambulance driver. Evelyn was daughter of Rev. Gervase Vanneck Blois, rector of

British Army Officers 1939−1945"The tragic loss of Iain Macleod"

bridge

A bridge is a structure built to Span (engineering), span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or railway) without blocking the path underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, whi ...

player in his twenties, after war service Macleod worked for the Conservative Research Department

The Conservative Research Department (CRD) is part of the central organisation of the Conservative Party in the United Kingdom. It operates alongside other departments of Conservative Campaign Headquarters in Westminster.

The CRD has been descri ...

before entering Parliament in 1950

Events January

* January 1 – The International Police Association (IPA) – the largest police organization in the world – is formed.

* January 5 – 1950 Sverdlovsk plane crash, Sverdlovsk plane crash: ''Aeroflot'' Lisunov Li-2 ...

. He was noted as a formidable Parliamentary debater and—later—as a platform orator. He was quickly appointed Minister of Health, later serving as Minister of Labour. He served an important term as Secretary of State for the Colonies

The secretary of state for the colonies or colonial secretary was the Cabinet of the United Kingdom's government minister, minister in charge of managing certain parts of the British Empire.

The colonial secretary never had responsibility for t ...

under Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986), was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Nickn ...

in the early 1960s, overseeing the independence of many African countries from British rule but earning the enmity of Conservative right-wingers, and the soubriquet that he was "too clever by half".

Macleod was unhappy with the "emergence" of Sir Alec Douglas-Home

Alexander Frederick Douglas-Home, Baron Home of the Hirsel ( ; 2 July 1903 – 9 October 1995), known as Lord Dunglass from 1918 to 1951 and the Earl of Home from 1951 to 1963, was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative ...

as party leader and prime minister in succession to Macmillan in 1963 (he claimed to have supported Macmillan's deputy Rab Butler

Richard Austen Butler, Baron Butler of Saffron Walden (9 December 1902 – 8 March 1982), also known as R. A. Butler and familiarly known from his initials as Rab, was a prominent British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party politici ...

, although it is unclear exactly what his recommendation had been). He refused to serve in Home's government, and while serving as editor of ''The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British political and cultural news magazine. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving magazine in the world. ''The Spectator'' is politically conservative, and its principal subject a ...

'' alleged that the succession had been stitched up by Macmillan and a "magic circle" of Old Etonians.

Macleod did not contest the first ever Conservative Party leadership election in 1965, but endorsed the eventual winner Edward Heath

Sir Edward Richard George Heath (9 July 1916 – 17 July 2005) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1970 to 1974 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1965 ...

. When the Conservatives returned to power in June 1970, he was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

in Heath's government, but died suddenly only a month later.

Early life

Iain Macleod was born at Clifford House,Skipton

Skipton (also known as Skipton-in-Craven) is a market town and civil parish in North Yorkshire, England. Historically in the East Division of Staincliffe Wapentake in the West Riding of Yorkshire, it is on the River Aire and the Leeds ...

, Yorkshire, on 11 November 1913. His father, Dr. Norman Alexander Macleod, was a well-respected general practitioner in Skipton, with a substantial poor-law practice (providing medical services for those who could not afford to pay); the young Macleod would often accompany his father on his rounds.Goldsworthy 2004, pp. 810–16 His parents were from the Isle of Lewis

The Isle of Lewis () or simply Lewis () is the northern part of Lewis and Harris, the largest island of the Western Isles or Outer Hebrides archipelago in Scotland. The two parts are frequently referred to as if they were separate islands. The t ...

in the Western Isles

The Outer Hebrides ( ) or Western Isles ( , or ), sometimes known as the Long Isle or Long Island (), is an island chain off the west coast of mainland Scotland.

It is the longest archipelago in the British Isles. The islands form part ...

of Scotland, his father a descendant of tenant farmers on Pabbay and Uig Uig is a placename meaning "bay" (from Norse) and may refer to:

Places

* Uig, Coll, a hamlet on the island of Coll, Argyll and Bute, Scotland

* Uig, Duirinish, a hamlet near Totaig, on the Isle of Skye, Highland Scotland

* Uig, Lewis, a civil par ...

, tracing back to the early 1500s. They moved to Skipton in 1907. Macleod grew up with strong personal and cultural ties to Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, as his parents bought in 1917 part of the Leverhulme

The Leverhulme Trust () is a large national grant-making organisation in the United Kingdom. It was established in 1925 under the will of the 1st Viscount Leverhulme (1851–1925), with the instruction that its resources should be used to cover ...

estate on the Isle of Lewis, where they often used to stay for family holidays.

He was educated at Ermysted's Grammar School

Ermysted's Grammar School is an 11-18 boys' Voluntary aided school, voluntary aided grammar school in Skipton, North Yorkshire, England.

It was founded by Peter Toller in the 15th century and is the List of the oldest schools in the United Kin ...

in Skipton, followed by four years (beginning in 1923) at St Ninian's Dumfriesshire, followed by five years at the private school Fettes College

Fettes College () is a co-educational private boarding and day school in Craigleith, Edinburgh, Scotland, with over two-thirds of its pupils in residence on campus. The school was originally a boarding school for boys only and became co-ed in ...

in Edinburgh. Macleod showed no great academic talent, but did develop an enduring love of literature, especially poetry, which he read and memorised in great quantity.Shepherd, pp. 17–21. In his final year at school Macleod appears to have blossomed a little, standing for Oswald Mosley

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980), was a British aristocrat and politician who rose to fame during the 1920s and 1930s when he, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, turned to fascism. ...

's New Party in the mock election in October 1931; he came third, behind the Unionist and Ian Harvey

Ian Joseph Harvey (born 10 April 1972) is a former Australian cricketer. He was an all-rounder who played 73 One Day Internationals for Australia and was named as one of the five Wisden Cricketers of the Year for 2004 for his performances i ...

who stood as a Scottish nationalist and came second. He won the School History Prize in his final year.

Cambridge and cards

In 1932, Macleod went up toGonville and Caius College, Cambridge

Gonville and Caius College, commonly known as Caius ( ), is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1348 by Edmund Gonville, it is the fourth-oldest of the University of Cambridge's 31 colleges and ...

, where he read history. His only recorded speech at the Cambridge Union Society

The Cambridge Union Society, also known as the Cambridge Union, is a historic Debate, debating and free speech society in Cambridge, England, and the largest society in the University of Cambridge. The society was founded in 1815 making it the ...

was in his first term against the Ottawa agreement

The British Empire Economic Conference (also known as the Imperial Economic Conference or Ottawa Conference) was a 1932 conference of British colonies and dominions held to discuss the Great Depression. It was held between 21 July and 20 Augus ...

– his biographer comments that although not too much should be made of this, it suggests a lack of sentimental attachment to the Empire. He took no other part in student politics, but spent much of his time reading poetry and playing bridge, both for the University (he helped to found the Cambridge University Bridge Society) and at Crockfords and in the West End. He graduated with a Lower Second in 1935.

A bridge connection with the chairman of the printing company De La Rue

De La Rue plc (, ) is a British company headquartered in Basingstoke, England, that produces secure digital and physical protections for goods, trade, and identities in 140 countries. It sells to governments, central banks, and businesses. Its ...

earned him a job offer.Shepherd, p. 102. However, he devoted most of his energies to bridge and, by 1936, was an international bridge player. He was one of the great British bridge

A bridge is a structure built to Span (engineering), span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or railway) without blocking the path underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, whi ...

players. He won the Gold Cup in 1937, with teammates Maurice Harrison-Gray

Maurice Harrison-Gray (13 November 1899 – 24 November 1968), known always as 'Gray', was an English professional contract bridge player. For about thirty years from the mid-thirties to the mid-sixties he was one of the top players. As a member o ...

(Capt), Skid Simon, Jack Marx

Jackson Gregory Marx, known as Jack Marx, is an Australian journalist and author. He was born in Maitland, New South Wales.

Career

Marx moved to Sydney in his late teens to pursue a career in music with the rock band I Spartacus (previously ...

and Colin Harding.

At a time when average male earnings were around £200 per annum (around £11,000 at 2016 prices) and he was earning around £150 per annum at De La Rue, Macleod sometimes made £100 in a night gambling, but on another occasion had to borrow £100 from his father to pay his debts.Shepherd 1994, pp. 22–24 Macleod was often too tired to work in the mornings after gambling for much of the night, although he tended to perk up as the day went on; he was popular with colleagues and on at least one occasion mucked in to work overtime for a last-minute order for Chinese banknotes. His biographer comments that he "might have stayed" had he found the work more interesting, but after tolerating him for a number of years De La Rue sacked him in 1938.

In order to placate his father he joined the Inner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as the Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court and is a professional association for barristers and judges. To be called to the Bar and practice as a barrister in England and Wa ...

and went through the motions of studying to become a barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include arguing cases in courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, jurisprud ...

, but in the late 1930s he was essentially living the life of a playboy from his bridge earnings. He was winning up to £2,500 per annum tax free (around £140,000 at 2016 prices).

He later wrote a book that contains a description of the Acol

Acol is the bridge bidding system that, according to ''The Official Encyclopedia of Bridge'', is "standard in British tournament play and widely used in other parts of the world". It is a natural system using four-card majors and, most commonly, ...

system of : ''Bridge is an Easy Game'', published in 1952 by Falcon Press, London. He was still earning money from playing and writing newspaper columns about bridge until 1952, when his developing political career became his priority.

War service

Early war

In September 1939, upon the outbreak of theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Macleod enlisted in the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

as a private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* "In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorded ...

in the Royal Fusiliers

The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army in continuous existence for 283 years. It was known as the 7th Regiment of Foot until the Childers Reforms of 1881.

The regiment served in many war ...

. On 20 April 1940, he was commissioned as an officer with the rank of second lieutenant in the Duke of Wellington's Regiment

The Duke of Wellington's Regiment (West Riding) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, forming part of the King's Division.

In 1702, Colonel George Hastings, 8th Earl of Huntingdon, was authorised to raise a new regiment, which he di ...

(DWR), with the service number

A service number or roll number is an identification code used to identify a person within a large group. Service numbers are most often associated with the military; however, they also may be used in civilian organizations. National identificati ...

129352. He was posted to the 2/7th Battalion, DWR, which was then serving as part of the 137th Infantry Brigade of the 46th Infantry Division, a second line Territorial Army (TA) formation, then commanded by Major-General Henry Curtis. Macleod's battalion was sent overseas to France in time to see action in the Battle of France

The Battle of France (; 10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign (), the French Campaign (, ) and the Fall of France, during the Second World War was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembour ...

in May, where he was injured in the leg by a flying log when a German armoured car burst through a road block which his men had just erected. He was treated in hospital in Exeter and left with a lifelong slight limp. In later life, besides his limp he suffered pain and reduced mobility from the spinal condition ankylosing spondylitis

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a type of arthritis from the disease spectrum of axial spondyloarthritis. It is characterized by long-term inflammation of the joints of the spine, typically where the spine joins the pelvis. With AS, eye and bow ...

.

At the age of 27, Macleod was already considered somewhat too old to be a platoon commander. Once fit for duty again, he served as a staff captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

with the 46th Division in Wye, under the Deputy Assistant Adjutant General (DAAG), Captain Dawtry. In 1941, a drunk Macleod almost killed Dawtry, as the latter had retired to bed rather than play stud poker

Stud poker is any of a number of poker variants in which each player receives a mix of face-down and face-up cards dealt in multiple betting rounds. Stud games are also typically '' non-positional'' games, meaning that the player who bets first ...

with him. He shot at his door until his revolver ran out of bullets, and then passed out after smashing down the door with a heavy piece of furniture. He demanded an apology the next morning for his refusal to play, although the two men remained friends thereafter. Dawtry later became Chief Clerk of Westminster Council.Sandford 2005, pp. 285

Staff College, D-Day and European campaign

Macleod attendedStaff College, Camberley

Staff College, Camberley, Surrey, was a staff college for the British Army and the presidency armies of British India (later merged to form the Indian Army). It had its origins in the Royal Military College, High Wycombe, founded in 1799, which ...

, in 1943, and graduated early in February 1944, having for the first time had to test his abilities against other able men and found something of a purpose in life.

As a major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

, he landed in France on Gold Beach

Gold, commonly known as Gold Beach, was the code name for one of the five areas of the Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of German military administration in occupied France during World War II, German-occupied France in the Normandy la ...

on D-Day

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during the Second World War. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

on 6 June 1944, as Deputy Assistant Quartermaster general (DAQMG) of the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division

The 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division was an infantry division of the British Army that saw distinguished service in the Second World War. Pre-war, the division was part of the Territorial Army (TA) and the two ''Ts'' in the divisional in ...

, a first line TA formation, under the command of Major-General Douglas Graham. Macleod embarked on 1 June ready for the invasion, which was then postponed from 5 June to 6 June. The 50th Division, a highly experienced veteran formation which had fought in North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

and Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, was tasked with capturing Arromanches

Arromanches-les-Bains (; or simply Arromanches) is a commune in the Calvados department in the Normandy region of north-western France.

Geography

Arromanches-les-Bains is 12 km north-east of Bayeux and 10 km west of Courseulles-su ...

, where the Mulberry artificial harbour was to be set up, and by the end of the day patrols had pushed to the outskirts of Bayeux

Bayeux (, ; ) is a commune in the Calvados department in Normandy in northwestern France.

Bayeux is the home of the Bayeux Tapestry, which depicts the events leading up to the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. It is also known as the fir ...

. Macleod spent much of the day touring the beachhead

A beachhead is a temporary line created when a military unit reaches a landing beach by sea and begins to defend the area as other reinforcements arrive. Once a large enough unit is assembled, the invading force can begin advancing inland. Th ...

area to check on progress, driving past enemy-held strongpoints, with Lieutenant Colonel "Bertie" Gibb. He later recorded that he had "a patchwork of memories" of D-Day. He could remember what he ate but not when he ate it, or that when he went to load his revolver he found his batman

Batman is a superhero who appears in American comic books published by DC Comics. Batman was created by the artist Bob Kane and writer Bill Finger, and debuted in Detective Comics 27, the 27th issue of the comic book ''Detective Comics'' on M ...

had instead filled his ammunition pouch with boiled sweets. British planners had expected 40% casualties on D-Day, and Macleod later recorded that he himself had fully expected to be killed, but on realising at midnight that he had survived D-Day decided that he would survive the war and see the birth of his second child in October.Shepherd 1994, pp. 33–34

Contemporaries began to record him saying that autumn that he planned to enter politics and become prime minister. He continued to serve in France and the Low Countries until November 1944, when the 50th Division was, due to a highly critical shortage of manpower in the British Army at this stage of the war, ordered to return to Yorkshire to be reconstituted as a training division. Macleod ended the war as a major.

1945 election and final Army service

Macleod unsuccessfully contested theWestern Isles

The Outer Hebrides ( ) or Western Isles ( , or ), sometimes known as the Long Isle or Long Island (), is an island chain off the west coast of mainland Scotland.

It is the longest archipelago in the British Isles. The islands form part ...

constituency at the 1945 general election. There was no Conservative Party in the seat, so Macleod advertised an inaugural meeting. He and his father, a lifelong Liberal but an admirer of Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, were the only attendees, so Macleod elected his father Association Chairman and he selected his son as Parliamentary candidate, in due course receiving a letter of endorsement from Churchill. Macleod came bottom of the poll, obtaining 2,756 votes out of 13,000. Macleod's father died at the start of 1947, just at the onset of the exceptionally bitter winter.

With the 50th Division now largely disbanded, its HQ was sent to Norway after the end of hostilities in May 1945 as part of Operation Doomsday

In Operation Doomsday, the British 1st Airborne Division acted as a police and military force during the Allied occupation of Norway in May 1945, immediately after the victory in Europe during the Second World War. The division maintained law ...

, supervising the surrender of German forces and repatriation of Allied prisoners. In Norway, Macleod was in charge of setting prices for the country's stock of wine and spirits, much of which had been looted by the Germans from occupied France. In December 1945, he successfully defended a colonel at a court martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the mili ...

, and was tipped for a career at the Bar by the presiding officer. He was demobilised from the British Army in January 1946.

Entry into politics

In 1946, after an interview with David Clarke, Macleod joined the Conservative Parliamentary Secretariat, writing briefing papers for Conservative MPs on Scotland, labour (employment, in modern parlance) and health matters. Macleod was selected as Conservative candidate for Enfield in 1946. Forty-seven applicants were already being considered; through a bridge connection Macleod arranged a meeting with the Enfield Conservative Association chairman and persuaded him to add his CV to the list. After interviews, he reached the final shortlist of four. Macleod came second after making a poor speech to the assembled Association at the selection meeting, but the winning candidate failed to achieve the required 10% majority. Amid accusations of skulduggery—the members had not been told of this requirement in advance and forty of them, the representatives of two branches, walked out in protest—a second meeting was scheduled, at which Macleod performed much better and won handsomely. Throughout both meetings he had been strongly supported by the local Young Conservatives, who could vote on Association matters despite in some cases being not yet old enough to vote for Parliament – the 15-year-oldNorman Tebbit

Norman Beresford Tebbit, Baron Tebbit, (born 29 March 1931) is a British retired politician. A member of the Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party, he served in the Cabinet from 1981 to 1987 as Secretary of State for Employment (1981–1 ...

was a branch officer for Ponders End

Ponders End is the southeasternmost part of Enfield, London, Enfield, North London, north London, England, around Hertford Road west of the Lee Navigation, River Lee Navigation. It became Industrial suburb, industrialised through the 19th centur ...

(a working class area).Shepherd 1994, pp. 53–54

Enfield had been won by the Conservatives several times in the interwar period, but with a 12,000 Labour majority in 1945 was not regarded as an immediate prospect. In 1948, the Parliamentary boundaries were redrawn, and Macleod was unanimously selected for the new and much more winnable Enfield, West, which he would win in February 1950 and hold comfortably throughout his career.

In 1948, the Secretariat merged with the Conservative Research Department

The Conservative Research Department (CRD) is part of the central organisation of the Conservative Party in the United Kingdom. It operates alongside other departments of Conservative Campaign Headquarters in Westminster.

The CRD has been descri ...

under Rab Butler

Richard Austen Butler, Baron Butler of Saffron Walden (9 December 1902 – 8 March 1982), also known as R. A. Butler and familiarly known from his initials as Rab, was a prominent British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party politici ...

. Macleod was in joint, then sole, charge of Home Affairs. He drafted the Social Services section of the Conservative policy paper ''The Right Road for Britain'' (1949).

Along with Enoch Powell

John Enoch Powell (16 June 19128 February 1998) was a British politician, scholar and writer. He served as Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) for Wolverhampton South West for the Conservative Party (UK), Conserv ...

, Angus Maude

Angus Edmund Upton Maude, Baron Maude of Stratford-upon-Avon, (8 September 1912 – 9 November 1993) was an English Conservative Party politician. A Member of Parliament (MP) from 1950 to 1958 and from 1963 to 1983, he served as a cabinet min ...

and Reginald Maudling

Reginald Maudling (7 March 1917 – 14 February 1979) was a British politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1962 to 1964 and as Home Secretary from 1970 to 1972. From 1955 until the late 1960s, he was spoken of as a prospecti ...

, Macleod was seen as a protégé of Butler at the CRD. David Clarke thought Macleod the least intellectually gifted of the three but later came to think him the most politically gifted. All four men were elected to Parliament in February 1950, and along with Edward Heath

Sir Edward Richard George Heath (9 July 1916 – 17 July 2005) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1970 to 1974 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1965 ...

who entered Parliament at the same time they became members of the "One Nation" group. Together with Angus Maude, Macleod wrote the pamphlet ''One Nation'' in 1950, and together with Enoch Powell he wrote ''The Social Services: Needs and Means'' which appeared in January 1952.

Macleod and Powell were close friends at this time. He was astonished when the ascetic Powell became engaged. Powell, a much more industrious man, was somewhat jealous of Macleod's promotion at the Research Department, and had difficulty being selected for a winnable seat, so Macleod coached him in interview technique.

Political career

Minister of Health

In October 1951 Churchill again became prime minister. Macleod was not offered office but instead became Chairman of the backbench Health and Social Services Committee. A brilliant Commons performance made his career. On 27 March 1952, having been called fifth in the debate rather than third as originally scheduled, he spoke after former Health MinisterAneurin Bevan

Aneurin "Nye" Bevan Privy Council (United Kingdom), PC (; 15 November 1897 – 6 July 1960) was a Welsh Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician, noted for spearheading the creation of the British National Health Service during his t ...

. Beginning his speech with the words "I wish to deal closely and with relish with the vulgar, crude and intemperate speech to which the House of Commons has just listened", he attacked Bevan with facts and figures and commented that a health debate without Bevan would be like "''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play. Set in Denmark, the play (the ...

'' without the first gravedigger". Churchill, who had been getting up to leave, stayed to listen and was heard to ask the Chief Whip

The Chief Whip is a political leader whose task is to enforce the whipping system, which aims to ensure that legislators who are members of a political party attend and vote on legislation as the party leadership prescribes.

United Kingdom

I ...

, Patrick Buchan-Hepburn, who the promising young backbencher was. When summoned to 10 Downing Street on 7 May, he claimed to have been half-expecting a reprimand for his refusal to serve a second term as a British representative at the Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; , CdE) is an international organisation with the goal of upholding human rights, democracy and the Law in Europe, rule of law in Europe. Founded in 1949, it is Europe's oldest intergovernmental organisation, represe ...

, a job he found boring, but he was instead appointed Minister of Health, which was not a Cabinet position at that time.

Later in 1952, Macleod announced that British clinician Richard Doll

Sir William Richard Shaboe Doll (28 October 1912 – 24 July 2005) was a British physician who became an epidemiologist in the mid-20th century and made important contributions to that discipline. He was a pioneer in research linking smoking t ...

had proved the link between smoking and lung cancer

Lung cancer, also known as lung carcinoma, is a malignant tumor that begins in the lung. Lung cancer is caused by genetic damage to the DNA of cells in the airways, often caused by cigarette smoking or inhaling damaging chemicals. Damaged ...

. He did so at a press conference throughout which he chain-smoked.

Macleod became a member of White's Club in 1953, and shocked members by sitting up all night to play cards. His friend Enoch Powell was jealous at Macleod's rapid promotion, but offered Macleod the use of a room at his flat when Eve Macleod was seriously ill with polio.

Macleod consolidated rather than reformed the NHS, administered it well and defended it against Treasury attacks on its budget.

Minister of Labour

In the reshuffle of December 1955, Prime MinisterAnthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achi ...

promoted Macleod to the Cabinet as Minister of Labour and National Service. Eden regarded Macleod, still only 42 years old, as a possible future prime minister and thought the job would be valuable experience of dealing with trade unions.

Suez crisis

Macleod was not directly involved in the collusion with France and Israel over theSuez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, also known as the Second Arab–Israeli War, the Tripartite Aggression in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel, was a British–French–Israeli invasion of Egypt in 1956. Israel invaded on 29 October, having done so w ...

, but although he was unhappy at the turn of events, he did not resign. He never publicly opposed Suez, either at the time or later. He was party to the two crucial Cabinet decisions: the first was the decision on 21 March for a policy of hostility to Nasser, who was seen as a threat to British interests in the Middle East, and of building new alliances with Jordan and Iraq; this led to the withdrawal of American and British financial aid for the Aswan Dam

The Aswan Dam, or Aswan High Dam, is one of the world's largest embankment dams, which was built across the Nile in Aswan, Egypt, between 1960 and 1970. When it was completed, it was the tallest earthen dam in the world, surpassing the Chatuge D ...

, which in turn triggered Nasser's nationalisation of the Canal. Macleod was also party to the Cabinet decision on 27 July, the day after nationalisation the Canal, that Nasser's action should be opposed on the grounds that the Canal was an international trust and that Britain, if necessary acting alone, should use force as a last resort. Macleod was not a member of the Egypt Committee, and still less was he party to Eden and Lloyd's secret dealings with the French and the Israelis.

Macleod's duties required him to discuss the Suez Crisis with union leaders. In August 1956, he spoke to Vincent Tewson, General Secretary of the TUC, and found him "very "weak-kneed"" and "ill-informed". On 20 August, Macleod and Eden met Tewson, Beard of the Engineers' Union and Geddes of the Postmen's Union, and agreed that the upcoming TUC Conference would back an equivocal resolution by Geddes.

On 25 August, the day after Monckton's "outburst" expressing doubts at the Egypt Committee, Cabinet Secretary Norman Brook

Norman Craven Brook, 1st Baron Normanbrook, (29 April 1902 – 15 June 1967), known as Sir Norman Brook between 1946 and 1964, was a British civil servant. He was Cabinet Secretary between 1947 and 1962 as well as joint permanent secretary to HM ...

sent a note to Eden listing Macleod as among those Cabinet members (the others being Butler, Monckton, Derrick Heathcoat Amory, the Earls of Selkirk and Kilmuir, as well as Heath who, as Chief Whip, attended Cabinet but was not technically a full member) who would want to postpone military action until all other options had been exhausted or until Nasser provided them with a better pretext, whichever came first. There were three unknowns and ten hawks—a narrow Cabinet majority in favour of military action.Shepherd 1994, p. 116

On 11 September, at Cabinet, Eden tasked Macleod with finding out if there would be trouble from the unions in the event of military operations in the Eastern Mediterranean. However, Norman Brook advised Macleod to "hold his hand for the moment, as this was not the appropriate time". It is unclear if this initiative came from Brook or was in response to an inquiry from Macleod himself.

Suez: decision to invade

Macleod missed the thinly-attended Cabinet on 18 October, but afterwards was sent Eden's minute that he'd told the French that every effort must be made to stop Israel attacking Jordan, whilst Eden had told Israel that Britain would ''not'' come to Egypt's aid. It is not known whether Macleod knew of the secretProtocol of Sèvres

The Protocol of Sèvres (French, ''Protocole de Sèvres'') was a secret agreement reached between the governments of Israel, France and the United Kingdom during discussions held between 22 and 24 October 1956 at Sèvres, France. The protocol co ...

. On 23 October, Eden told the Cabinet that there had been secret talks with Israel in Paris.

The Cabinet further considered the use of force on 24 October.Shepherd 1994, p. 117 On 25 October, Eden told the Cabinet that Israel would attack Egypt after all, but did not tell them about the secret Sèvres Protocol. Cabinet minutes record that Macleod was doubtful about the use of force (as were Monckton and Heathcoat Amory) because of the lack of clear UN authority and the risk of antagonising the USA. However, they did not formally dissent from the Cabinet decision to invade if Israel attacked Egypt (the Cabinet were deceived about the extent to which such an attack had already been secretly agreed – "collusion" – by Eden and Selwyn Lloyd).

At Cabinet on the morning of 30 October, Lloyd reported that the US was ready to move a motion at the UN condemning Israel, which had attacked Egypt in the Sinai the previous day, as an aggressor. Macleod and Heathcoat Amory approved of Lloyd's suggestion of postponing the attack by 24 hours (in breach, as it happens, of the secret agreement between Britain, France and Israel) in order to bring the Americans on board, although they thought it unlikely to work, but it was not adopted. Macleod was telling others of his dismay that ministers had not been fully informed of the agreement with France and Israel. Either now or at some subsequent meeting Eden apologised to the Cabinet for his reticence "in time of war", causing Macleod to snap "I was not aware that we were at war, Prime Minister!" The Anglo-French ultimatum was on the afternoon of 30 October.

On 2 November, the Cabinet agreed that even in the event of a ceasefire between Egypt and Israel, Anglo-French forces should still seize the Canal in a policing role until UN forces were able to take up the baton (Macleod and Heathcoat Amory were doubtful). By the weekend of 3–4 November, fighting between Israel and Egypt had largely ceased.Shepherd 1994, p. 118 At Cabinet on Sunday 4 November, the Cabinet decided to go ahead with the landings (but hand over to peacekeeping duties to the UN at some future date, an option which Macleod (and Heathcoat Amory) argued was hardly compatible with use of force). The other options had been to postpone by 24 hours in the hope that Israel and Egypt might accept an Anglo-French occupation (a view supported by Butler, Kilmuir, Heathcote Amory and an "unnamed minister", presumed to be Macleod), or postpone indefinitely on the grounds that Israeli-Egyptian hostilities had already ceased (the view of Salisbury, Monckton and Buchan-Hepburn). Only Monckton had his dissent recorded, the others agreeing to accept the decision of the majority.

Randolph Churchill

Major (rank), Major Randolph Frederick Edward Spencer Churchill (28 May 1911 – 6 June 1968) was an English journalist, writer and politician.

The only son of future List of British Prime Ministers, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill a ...

alleged that Macleod almost resigned on 4 November. Nigel Fisher wrote that this was not so, but that Macleod would have resigned if Butler had done so. Robert Carr

Leonard Robert Carr, Baron Carr of Hadley, (11 November 1916 – 17 February 2012) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Home Secretary from 1972 to 1974. He served as a Member of Parliament (MP) for 26 years, and later s ...

, junior minister at the Ministry of Labour, wrote that Macleod had doubts but was not especially morally outraged, and saw no evidence that he planned to resign. William Rees-Mogg

William Rees-Mogg, Baron Rees-Mogg (14 July 192829 December 2012) was a British newspaper journalist who was Editor of ''The Times'' from 1967 to 1981. In the late 1970s, he served as High Sheriff of Somerset, and in the 1980s was Chairman of ...

claimed that Butler persuaded Macleod not to resign, while a female friend of Macleod's recorded him turning up at her flat, demanding a drink, and declaring that he would have to resign having learned that Eden had deceived the Cabinet.

Suez alienated academics, journalists and other opinion-formers from the Conservative Party. William Rees-Mogg

William Rees-Mogg, Baron Rees-Mogg (14 July 192829 December 2012) was a British newspaper journalist who was Editor of ''The Times'' from 1967 to 1981. In the late 1970s, he served as High Sheriff of Somerset, and in the 1980s was Chairman of ...

, then a Conservative candidate in the North-East, made a speech urging that Macleod be party leader. David Astor

Francis David Langhorne Astor (5 March 1912 – 7 December 2001) was an English newspaper publisher, editor of ''The Observer'' at the height of its circulation and influence, and member of the Astor family, "the landlords of New York".

Early ...

of ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. First published in 1791, it is the world's oldest Sunday newspaper.

In 1993 it was acquired by Guardian Media Group Limited, and operated as a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' ...

'', who on 4 November had attacked Eden for "crookedness" in an editorial, wrote to Macleod on 14 November, urging him as a younger minister to seize the party leadership so that collusion could be pinned on Eden and Lloyd, after Edward Boyle had told him that he was not interested and that Monckton was not up to it. Macleod did not reply but showed the letter to Freddie Bishop, head of the Prime Minister's Private Office, and Cabinet Secretary Norman Brook for their comments; Eden, who was on the verge of a breakdown, did not regard the matter as important. On 20 November 1956 the question of collusion was raised in Cabinet, with Eden and Lloyd (who was in New York at a United Nations meeting) both absent; Shepherd believes that it was probably Macleod who raised it. The Cabinet agreed to stick to Lloyd's formula that Britain had not ''incited'' the Israeli attack on Egypt.

1958 bus strike

When Eden stepped down as prime minister in January 1957, Lord Kilmuir, formally witnessed byLord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903), known as Lord Salisbury, was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United ...

, took a straw poll of the Cabinet to determine his successor; despite his closeness to Butler, Macleod, along with the overwhelming majority of his colleagues, backed Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986), was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Nickn ...

, regarding him as a stronger leader.

Macleod had intended at first to be a reforming Minister of Labour – he attempted, in the teeth of resistance from the TUC, to negotiate a Workers' Charter (a throwback to the Industrial Charter of the late 1940s) in return for a Contract of Service. He also hoped to take a tougher line with strikes than his predecessor Walter Monckton

Walter Turner Monckton, 1st Viscount Monckton of Brenchley, (17 January 1891 – 9 January 1965) was a British lawyer and politician.

Early years

Monckton was born in the village of Plaxtol in north Kent. He was the eldest child of paper manu ...

, whose explicit remit had been to appease the unions. The unions were beginning to become more militant, under the leadership of Frank Cousins Frank Cousins may refer to:

* Frank Cousins (British politician) (1904–1986), British trade union leader and Labour politician

* Frank Cousins (American politician) (born 1958), American politician who served as the Essex County, Massachusetts ...

, boss of the TGWU

The Transport and General Workers' Union (TGWU or T&G) was one of the largest general trade unions in the United Kingdom and Ireland—where it was known as the Amalgamated Transport and General Workers' Union (ATGWU)—with 900,000 members (a ...

.

Macleod had to settle strikes in the shipbuilding and engineering industries in 1957, but in 1958 the government felt able to take a stronger line with the London bus strike. Macleod initially accepted his own chief Industrial Commissioner's Investigation into the busmens' case. Macmillan, backed by the Cabinet, insisted on settling a separate railwaymen's strike, despite an arbitration award against them, as it was felt that they had more public sympathy than the busmen. On the bus issue, Macleod was overruled and forced to pick a fight with Frank Cousins on the pretext that they accept an independent arbitration award.Jenkins 1993, pp. 40–41Williams 1979, pp. 462–64

Macmillan had picked a fight shrewdly, as the busmen had no allies amongst the other unions. Ernest Bevin

Ernest Bevin (9 March 1881 – 14 April 1951) was a British statesman, trade union leader and Labour Party politician. He co-founded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union from 1922 to 1940 and ...

or Arthur Deakin

Arthur Deakin (11 November 1890 – 1 May 1955) was a prominent British trade unionist who was acting general secretary of the Transport and General Workers' Union from 1940 and then general secretary from 1945 to 1955.

Background

Arthur ...

would not have allowed such a strike, but Cousins felt compelled to support it, and Opposition leader Hugh Gaitskell

Hugh Todd Naylor Gaitskell (9 April 1906 – 18 January 1963) was a British politician who was Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party and Leader of the Opposition (United Kingdom), Leader of the Opposition from 1955 until ...

criticised the government in a speech at Glasgow. Gaitskell moved a motion of censure over Macleod's treatment of the strike.Shepherd 1994, pp. 138–39 Macleod had recently demanded more debates on industrial relations but in his Commons speech of 8 May now criticised the opposition for demanding one. He moved the house to laugh at Gaitskell by quoting the line of "Mr Marx, of whom I am a devoted follower – Groucho, not Karl Karl may refer to:

People

* Karl (given name), including a list of people and characters with the name

* Karl der Große, commonly known in English as Charlemagne

* Karl of Austria, last Austrian Emperor

* Karl (footballer) (born 1993), Karl Cac ...

" "Sir, I never forget a face, but I will make an exception for yours". He then moved on to a blistering attack on Gaitskell, including the declaration that "I cannot conceal the scorn and contempt for the part that the Leader of the Opposition has played in this." He was discreetly congratulated afterwards by the Labour frontbencher Alf Robens

Alfred Robens, Baron Robens of Woldingham, PC (18 December 1910 – 27 June 1999) was an English trade unionist, Labour politician and industrialist. His political ambitions, including an aspiration to become Prime Minister, were frustrated b ...

. Roy Jenkins

Roy Harris Jenkins, Baron Jenkins of Hillhead (11 November 1920 – 5 January 2003) was a British politician and writer who served as the sixth President of the European Commission from 1977 to 1981. At various times a Member of Parliamen ...

in 1993 described Macleod's attack on Gaitskell as "high order jugular debating", accusing Gaitskell of weak leadership in appeasing the militants of his own party and attacking him for refusing to endorse the findings of the arbitration tribunal.

Cousins wanted to call out the petrol tanker drivers, in breach of another agreement, but was blocked from doing so by the TUC. The strike ended after seven weeks, and Macmillan dated the government's recovery in the polls from this point. After the TUC refused to back him, Cousins had had to settle the London transport workers strike on terms which he could have obtained without striking. In October 1958 Macleod announced that he was letting the National Arbitration Tribunal go out of existence. Macleod had acquired a national reputation as a tough figure.

Macleod was on the Steering Committee to decide on political strategy in the runup to the 1959 election, at which the Macmillan government was re-elected.

Colonial Secretary

Macleod was appointedSecretary of State for the Colonies

The secretary of state for the colonies or colonial secretary was the Cabinet of the United Kingdom's government minister, minister in charge of managing certain parts of the British Empire.

The colonial secretary never had responsibility for t ...

in October 1959. He had never set foot in any of Britain's colonies, but the Hola massacre

The 1959 Hola massacre was a massacre committed by British colonial forces during the Mau Mau Rebellion at a colonial detention camp in Hola, Kenya.

Event

The Hola camp was established to house detainees classified as "hard-core." By Januar ...

in Kenya

Kenya, officially the Republic of Kenya, is a country located in East Africa. With an estimated population of more than 52.4 million as of mid-2024, Kenya is the 27th-most-populous country in the world and the 7th most populous in Africa. ...

had helped focus his thinking on the inevitable end of Empire. He told Peter Goldman of the Conservative Research Department that he intended to be the Colonial Secretary, although he later wrote that he "telescoped events rather than creating new ones". He saw Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

, British Somaliland

British Somaliland, officially the Somaliland Protectorate (), was a protectorate of the United Kingdom in modern Somaliland. It was bordered by Italian Somalia, French Somali Coast and Ethiopian Empire, Abyssinia (Italian Ethiopia from 1936 ...

, Tanganyika, Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

, Kuwait

Kuwait, officially the State of Kuwait, is a country in West Asia and the geopolitical region known as the Middle East. It is situated in the northern edge of the Arabian Peninsula at the head of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to Iraq–Kuwait ...

and British Cameroon

British Cameroons or British Cameroon was a British mandate territory in British West Africa, formed of the Northern Cameroons and Southern Cameroons. Today, the Northern Cameroons forms parts of the Borno, Adamawa and Taraba states of Niger ...

become independent. He made a tour of Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lie south of the Sahara. These include Central Africa, East Africa, Southern Africa, and West Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the list of sovereign states and ...

in 1960. He would often find himself in conflict with the more conservative Duncan Sandys

Duncan Edwin Duncan-Sandys, Baron Duncan-Sandys (; 24 January 1908 – 26 November 1987), was a British politician and minister in successive Conservative governments in the 1950s and 1960s. He was a son-in-law of Winston Churchill and played a ...

, whom Macmillan had appointed Commonwealth Secretary as a counterweight to Macleod. Although Macmillan sympathised with Macleod's aspirations, he was sometimes disturbed at the speed with which he progressed matters, and did not always come down on his side in political disputes.

The state of emergency in Kenya was lifted on 12 January 1960, followed that same month by the Lancaster House Conference, containing Africans and ''some'' European delegates, including Macleod's brother Rhoderick, which agreed to a constitution and eventual black majority rule. Jomo Kenyatta

Jomo Kenyatta (22 August 1978) was a Kenyan anti-colonial activist and politician who governed Kenya as its Prime Minister from 1963 to 1964 and then as its first President from 1964 to his death in 1978. He played a significant role in the ...

was freed in August 1961, and Kenya later became self-governing in June 1963 and fully independent on 12 December 1963.

As the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Macleod attended the Ugandan Constitutional Conference

The Ugandan Constitutional Conference, held at Lancaster House in the autumn of 1961, was organised by the British Government to pave the way of Ugandan independence.

History

The Conference opened on 18 September 1961 and concluded on 9 October ...

at Lancaster House

Lancaster House (originally known as York House and then Stafford House) is a mansion on The Mall, London, The Mall in the St James's district in the West End of London. Adjacent to The Green Park, it is next to Clarence House and St James ...

in 1961 alongside then-Governor of Uganda Sir Frederick Crawford and Ugandan politician A. G. Mehta

A. G. Mehta (1 February 1927 – 10 March 1969) was a Ugandan member of parliament, barrister and the eldest son of a prominent Indian industrialist. The Honourable A.G. Mehta was elected as the first Asian-Indian mayor of Uganda's capital Kam ...

. The conference resulted in the first Ugandan Constitution, which took effect on 9 October 1962.

In Nyasaland

Nyasaland () was a British protectorate in Africa that was established in 1907 when the former British Central Africa Protectorate changed its name. Between 1953 and 1963, Nyasaland was part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. After ...

(later Malawi

Malawi, officially the Republic of Malawi, is a landlocked country in Southeastern Africa. It is bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northeast, and Mozambique to the east, south, and southwest. Malawi spans over and ...

), he pushed for the release of Hastings Banda

Hastings Kamuzu Banda ( – 25 November 1997) was a Malawian politician and statesman who served as the leader of Malawi from 1964 to 1994. He served as Prime Minister of Malawi, Prime Minister from independence in 1964 to 1966, when Malawi was ...

, contrary to the advice of the Governor and of other politicians. He had to threaten resignation in the Cabinet to get his own way, but won Macmillan round and Banda was released in April 1960 and almost immediately invited to London for talks aimed at bringing about independence. During a visit to Nyasaland in 1960, he is described as having been "gratuitously and grossly offensive, extremely rude and downright unpleasant at a meeting with the Governor, the provincial commissioners and senior police officers". On the following day, according to the same report, he "lost control of himself, shouted at the non-official members of Executive Council and told one of them to 'mind his own bloody business'". Elections were held in August 1961, and by 1962, the British and the Central African Federation

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

cabinets had agreed that Nyasaland should be allowed to secede from the CAF; Banda was formally recognised as prime minister on 1 February 1963.

Macleod described his policy over Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in Southern Africa, now the independent country of Zambia. It was formed in 1911 by Amalgamation (politics), amalgamating the two earlier protectorates of Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia and North ...

(modern Zambia

Zambia, officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern and East Africa. It is typically referred to being in South-Central Africa or Southern Africa. It is bor ...

) as "incredibly devious and tortuous" but "easily the one I am most proud of". Macleod's initial plan for a Legislative Council with an African majority (16 African members to 14 Europeans) was strongly opposed by Sir Roy Welensky, Prime Minister of the Central African Federation. After a long battle in the first half of 1961, and under pressure from cabinet colleagues, Macleod accepted Welensky's proposal for a council of 45 members, 15 of whom would be elected by a largely African electoral roll, 15 by a largely European roll, 14 by both rolls jointly (with a further stipulation that successful candidates had to gain at least 10% of the African votes and 10% of the European ones) and 1 by Asians. Macleod's role in these negotiations attracted damaging and much-remembered criticism by the party grandee, the Marquess of Salisbury, who had resigned from a senior position in the Cabinet over Cyprus in 1957. In a speech in the House of Lords on 7 March 1961, Salisbury denounced Macleod as "too clever by half" and accused him of bridge-table trickery. The new constitution, which was equally disliked by both Africans and Europeans, helped to weaken the Central African Federation, which was later wound up by Rab Butler at the Victoria Falls Conference on 5 July 1963.

The burden of hospitality left Macleod seriously out of pocket. However, hospitality helped achieve a deal with Julius Nyerere

Julius Kambarage Nyerere (; 13 April 1922 – 14 October 1999) was a Tanzanian politician, anti-colonial activist, and political theorist. He governed Tanganyika (1961–1964), Tanganyika as prime minister from 1961 to 1962 and then as presid ...

, Prime Minister of self-governing Tanganyika. Macleod was keen to point to a colony which was able to proceed peacefully to independence. Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

, as it was renamed, became fully independent in December 1961.

Macleod had no time to take any interest in the Pacific, South Arabia (modern-day Yemen and Oman), or the Mediterranean. He never met the Maltese leader Dom Mintoff

Dominic Mintoff ( ; often called ''il-Perit'', "the Architect"; 6 August 1916 – 20 August 2012) was a Maltese socialist politician, architect, and civil engineer who was leader of the Labour Party (Malta), Labour Party from 1949 to 1984 ...

. He described his lack of interest in the Caribbean Federation as "my main area of failure". In his final party conference speech as Colonial Secretary, in October 1961, he declared that "I believe quite simply in the brotherhood of man – men of all races, of all colours, of all creeds".

Welensky accused Macleod of a "mixture of cold calculation, sudden gushes of undignified emotion and ignorance of Africa". Historian Wm. Roger Louis wrote that "Macleod was to Africa as Mountbatten

The Mountbatten family is a British family that originated as a branch of the German princely Battenberg family. The name was adopted by members of the Battenberg family residing in the United Kingdom on 14 July 1917, three days before the Br ...

had been to India". Vernon Bogdanor

Sir Vernon Bernard Bogdanor (; born 16 July 1943) is a British political scientist, historian, and research professor at the Institute for Contemporary British History at King's College London. He is also emeritus professor of politics and go ...

has called him the greatest of Britain's colonial secretaries apart from Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal Party (UK), Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually was a leading New Imperialism, imperial ...

.

During his period as Colonial Secretary, Macleod ordered the systematic destruction of colonial papers and evidence detailing criminal acts committed during the 1940s and 1950s, for fear that they would fall into the hands of post-independence governments. This was done partly to avoid potential embarrassment to Britain, and partly to protect natives who had cooperated with the British. Many documents related to the brutal suppression of the Mau Mau Uprising

The Mau Mau rebellion (1952–1960), also known as the Mau Mau uprising, Mau Mau revolt, or Kenya Emergency, was a war in the British Kenya Colony (1920–1963) between the Kenya Land and Freedom Army (KLFA), also known as the Mau Mau, and the ...

in Kenya.

Books

In 1961, Macleod published a sympathetic biography of former prime ministerNeville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from ...

, whose reputation then stood at a very low ebb because of recent memories of the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement was reached in Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, the United Kingdom, the French Third Republic, French Republic, and the Kingdom of Italy. The agreement provided for the Occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–194 ...

. The book was largely ghostwritten by Peter Goldman, whose own promising political career would be aborted when he lost the Orpington by-election the following year. Macleod was most interested in social policy and had most input into the parts up to 1931, including Chamberlain's time as Lord Mayor of Birmingham and as Minister of Health.Shepherd 1994, pp. 270–72 It had been intended as a potboiler to earn money for his daughter's social season, and Macleod had been reluctant to read seven boxes of papers from Chamberlain's sister Hilda (Chamberlain's letters to whom are an important primary source); it added little to the portrait painted by his official biographer Keith Feiling

Sir Keith Grahame Feiling (7 September 1884 – 16 September 1977) was a British historian, biographer and academic. He was Chichele Professor of Modern History at the University of Oxford, 1946–1950. He was noted for his conservative interp ...

.

Macleod used government papers in breach of the " Fifty-year rule" then in operation. Cabinet Secretary

A cabinet secretary is usually a senior official (typically a civil servant) who provides services and advice to a cabinet of ministers as part of the Cabinet Office. In many countries, the position can have considerably wider functions and powe ...

Sir Norman Brook

Norman Craven Brook, 1st Baron Normanbrook, (29 April 1902 – 15 June 1967), known as Sir Norman Brook between 1946 and 1964, was a British civil servant. He was Cabinet Secretary between 1947 and 1962 as well as joint permanent secretary to HM ...

persuaded the Prime Minister to demand amendments to conceal the degree of Cabinet involvement in the abdication

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the Order of succession, succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of ...

of King Edward VIII

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire, and Emperor of India, from 20 January ...

(who was still alive in 1961) and the degree to which the civil servants Horace Wilson and Warren Fisher had demanded that the former King "reorder his private life" afterwards. Former prime minister Lord Avon, who cherished his (somewhat exaggerated) reputation as an opponent of "appeasement", complained that such a book by a serving Cabinet Minister might be thought to express official sympathy for Chamberlain's policies. Downing Street had to brief the press that Macleod had written purely in a personal capacity; Shepherd suggests that Macleod's loss of favour with Macmillan, who had also been an opponent of appeasement, was accelerated by this episode. Robert Blake Robert Blake (or variants) may refer to:

Sports

* Bob Blake (American football) (1885–1962), American football player

* Robbie Blake (born 1976), English footballer

* Bob Blake (ice hockey) (1914–2008), American ice hockey player

* Rob Blake ...

wrote in his review in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' (26 November 1961) that "when national security is at stake one does not judge a statesman by his successes at slum clearance

Slum clearance, slum eviction or slum removal is an urban renewal strategy used to transform low-income settlements with poor reputation into another type of development or housing. This has long been a strategy for redeveloping urban communities; ...

". Macleod later told Alan Watkins

Alan Rhun Watkins (3 April 1933 – 8 May 2010) was for over 50 years a British political columnist in various London-based magazines and newspapers. He also wrote about wine and rugby.

Life and career

Alan Watkins was born in Tycroes, Carma ...

(in ''"Brief Lives"'' 1982) "It was a bad book. I made a great mistake in writing it. It made me no money, and it has done me a lot of harm". Watkins conceded that the book "had been grudgingly and meanly reviewed". The book "sold poorly and was soon forgotten".

Macleod contracted to write a second book (due for September 1962, but postponed), called ''The Last Rung'', on leading politicians who had failed to achieve prime ministerial office despite being widely expected to do so. He completed chapters on Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of ...

, Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), known as Lord Curzon (), was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician, explorer and writer who served as Viceroy of India ...

and Lord Halifax

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax (16 April 1881 – 23 December 1959), known as the Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and the Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was a British Conservative politician of the 1930s. He h ...

, and planned to write a chapter about Rab Butler

Richard Austen Butler, Baron Butler of Saffron Walden (9 December 1902 – 8 March 1982), also known as R. A. Butler and familiarly known from his initials as Rab, was a prominent British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party politici ...

.

Leader of the House and Party Chairman, 1961–63

In October 1961, to appease Conservative right-wingers and dampen down an area of political controversy, Macmillan replaced Macleod as Colonial Secretary with Reginald Maudling, a much more emollient figure. Macleod replaced his old mentor Rab Butler as Leader of the House of Commons and Chairman of the Conservative Party organisation. There was something of a conflict of interest between these two jobs as the former, which Butler would have liked to retain, required its incumbent to retain good professional relations with the Labour Party so as to keep the Parliamentary timetable running smoothly, whereas the latter required him to play a leading role in partisan campaigning. In order that he could have a salary he was also given thesinecure

A sinecure ( or ; from the Latin , 'without', and , 'care') is a position with a salary or otherwise generating income that requires or involves little or no responsibility, labour, or active service. The term originated in the medieval church, ...

post of Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

The Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster is a ministerial office in the Government of the United Kingdom. Excluding the prime minister, the chancellor is the highest ranking minister in the Cabinet Office, immediately after the prime minister ...

, a less prestigious office than the other sinecures of Lord Privy Seal

The Lord Privy Seal (or, more formally, the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal) is the fifth of the Great Officers of State (United Kingdom), Great Officers of State in the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord President of the Council and abov ...

or Lord President of the Council

The Lord President of the Council is the presiding officer of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom and the fourth of the Great Officers of State, ranking below the Lord High Treasurer but above the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal. The Lor ...

.Jenkins 1993, p. 45

Macleod's party chairmanship coincided with Selwyn Lloyd's tight economic policies, and poor by-election results, most notably Orpington in March 1962. He impressed on Macmillan the need for a major reshuffle in 1962, and recommended the dismissal of Selwyn Lloyd from the ExchequerDell 1997, pp. 373–75 although he did not have in mind anything as drastic as the "Night of the Long Knives

The Night of the Long Knives (, ), also called the Röhm purge or Operation Hummingbird (), was a purge that took place in Nazi Germany from 30 June to 2 July 1934. Chancellor Adolf Hitler, urged on by Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler, ord ...

" in which Macmillan sacked a third of his Cabinet. With the political scandals of 1962–63 ( Vassall, Profumo) the Conservatives sank ever lower in the opinion polls.

Conservative leadership contest, 1963

Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986), was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Nickn ...

resigned as prime minister in October 1963. Despite Macleod's ability, as a result of his difficult term as Party Chairman, and memories of his time as Colonial Secretary, he was not a realistic candidate for the succession.

Macleod believed that the Earl of Home (later Sir Alec Douglas-Home

Alexander Frederick Douglas-Home, Baron Home of the Hirsel ( ; 2 July 1903 – 9 October 1995), known as Lord Dunglass from 1918 to 1951 and the Earl of Home from 1951 to 1963, was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative ...

after he had disclaimed his peerage) had behaved with less than complete honesty. He had initially appeared to rule himself out and had offered to help sample Cabinet opinion, before announcing his own candidacy. Macleod did not initially take Home's candidacy seriously, and did not realise the degree to which Macmillan was promoting it. When first told by his PPS PPS commonly refers to:

* Post-postscript, an afterthought, usually in a document.

PPS may also refer to:

Aviation

* Puerto Princesa International Airport, Palawan, Philippines (by IATA code)

* Priority Passenger Service, in Singapore Airlines#Fre ...

Reginald Bennett

Sir Reginald Frederick Brittain Bennett (Sheffield, 22 July 1911 – London, 19 December 2000) was a Conservative Party politician, international yachtsman, psychiatrist and painter.

Education

Bennett was educated at Winchester College and New ...

that Home might be a candidate for the succession, Macleod snapped "Don't talk nonsense" and "absolute rot; it's not a possibility." Macleod gave his usual excellent conference speech at Blackpool on 11 October, unlike Maudling and Butler, who damaged their leadership chances by giving poor speeches, but Home's leadership bandwagon grew despite a mediocre but rapturously received speech.

When the results of the "customary processes" became known on 17 October (the "key day" as Macleod later called it), Macleod was, along with Enoch Powell, Lord Hailsham and Reginald Maudling

Reginald Maudling (7 March 1917 – 14 February 1979) was a British politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1962 to 1964 and as Home Secretary from 1970 to 1972. From 1955 until the late 1960s, he was spoken of as a prospecti ...

, angered at the supposed choice of Home.Shepherd 1994, pp. 326–27 Macleod thought the new prime minister should be a "moderniser", with views on the liberal wing of the party, and in the House of Commons. They attempted in vain to persuade Butler, Macmillan's deputy (who Macleod had assumed would succeed him) not to serve in any Home cabinet, in the hope that this would prevent Home from forming a government. Macleod and Powell eventually refused to serve under Home as prime minister. He wrote of Enoch Powell's decision not to serve "One does not expect to have many people with one in the last ditch".

Lord Dilhorne, who had polled the Cabinet for their preferences, had listed Macleod as "voting" for Home. Some have seen this as a mistake, others as evidence that the consultation process was heavily rigged (i.e. that anybody who expressed the slightest willingness to serve under Home as a compromise if necessary was listed as "supporting" him). Macmillan's official biographer Alistair Horne

Horne became a senior member at St Antony's College, Oxford in 1970 and a fellow of the college in 1978. He was made an honorary fellow in 1988, a position he held until his death. He was knighted in the Queen's Birthday Honours in 2003 for ...

believed that Macleod's description of 17 October as "the key day" is evidence that he "changed his mind", having not previously had a particularly firm opinion. Macmillan's view was "well, you know … Macleod was a Highlander!" Others (e.g. Macmillan's biographer D. R. Thorpe

David Richard Thorpe, MBE, FRHistS (12 March 1943–2 February 2023) was a British historian and biographer of three Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom during the mid-20th century; Sir Anthony Eden, Sir Alec Douglas-Home and Harold Macmillan ...

) have suggested that Macleod actually ''did'' express a tactical preference for Home, in the hope of bringing about a deadlock in which he would enjoy bargaining power, or perhaps even become prime minister himself, and that his subsequent anger was a result of guilt that he had helped to bring about a Home "victory".

Butler himself observed that "Macleod was very shifty, much more so than you think". Nigel Lawson

Nigel Lawson, Baron Lawson of Blaby, (11 March 1932 – 3 April 2023) was a British politician and journalist. A member of the Conservative Party, he served as Member of Parliament for Blaby in Leicestershire from 1974 to 1992, and served ...

, later to succeed Macleod as editor of ''The Spectator'', believed Macleod was "too clever by three quarters". "His petulant refusal to serve under Home and the extended explanation he gave for it both deprived the government of its most effective political street fighter and undermined the new prime minister's legitimacy" (''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a British daily broadsheet conservative newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed in the United Kingdom and internationally. It was found ...

'', 3 October 2004).Thorpe 2010, pp. 574–76 However, Lord Aldington, David Eccles, Sir Michael Fraser and Eve Macleod all rejected this interpretation of Macleod's actions. Ian Gilmour

Ian Hedworth John Little Gilmour, Baron Gilmour of Craigmillar, (8 July 1926 – 21 September 2007) was a Conservative Party politician in the United Kingdom. He was styled Sir Ian Gilmour, 3rd Baronet from 1977, having succeeded to his fat ...

argues that Macleod's subsequent refusal to serve under Home makes it "inconceivable" that he had voted for him.

Macleod's daughter Diana nearly died from appendicitis in October 1963, and it has been suggested that this may have affected his judgement. Nigel Fisher believed that Macleod had "some inner sourness" in 1963, attributable only in part to his daughter's serious illness, and largely to the fact that he himself was not being considered as a candidate. Roy Jenkins concurs.

Had he become prime minister, Butler had planned to make Macleod Chancellor of the Exchequer and had discussed the names of economists who could be asked to advise. Butler later wrote "I cannot help thinking that a man who always held all the bridge scores in his head, who seemed to know all the numbers, and played Vingt-et-un