IZL on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Irgun (), officially the National Military Organization in the Land of Israel, often abbreviated as Etzel or IZL (), was a

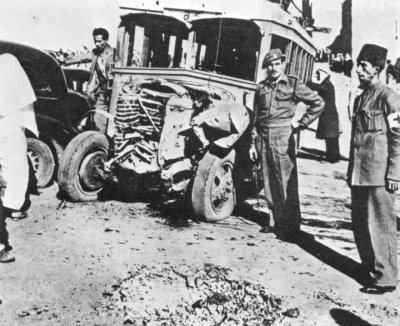

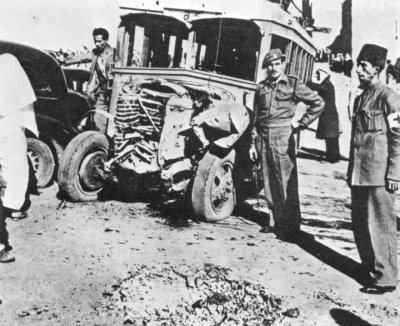

Irgun Bomb Kills 11 Arabs, 2 Britons

''New York Times''. December 30, 1947.

''New York Times''. August 16, 1947. as well as by the

Members of the Irgun came mostly from

Members of the Irgun came mostly from

In 1933 there were some signs of unrest, seen by the incitement of the local Arab leadership to act against the authorities. The strong British response put down the disturbances quickly. During that time the Irgun operated in a similar manner to the Haganah and was a guarding organization. The two organizations cooperated in ways such as coordination of posts and even intelligence sharing.

Within the Irgun, Tehomi was the first to serve as "Head of the Headquarters" or "Chief Commander". Alongside Tehomi served the senior commanders, or "Headquarters" of the movement. As the organization grew, it was divided into district commands.

In August 1933 a "Supervisory Committee" for the Irgun was established, which included representatives from most of the Zionist political parties. The members of this committee were Meir Grossman (of the Hebrew State Party), Rabbi

In 1933 there were some signs of unrest, seen by the incitement of the local Arab leadership to act against the authorities. The strong British response put down the disturbances quickly. During that time the Irgun operated in a similar manner to the Haganah and was a guarding organization. The two organizations cooperated in ways such as coordination of posts and even intelligence sharing.

Within the Irgun, Tehomi was the first to serve as "Head of the Headquarters" or "Chief Commander". Alongside Tehomi served the senior commanders, or "Headquarters" of the movement. As the organization grew, it was divided into district commands.

In August 1933 a "Supervisory Committee" for the Irgun was established, which included representatives from most of the Zionist political parties. The members of this committee were Meir Grossman (of the Hebrew State Party), Rabbi

According to Jabotinsky's "Evacuation Plan", which called for millions of

According to Jabotinsky's "Evacuation Plan", which called for millions of

While continuing to defend settlements, Irgun members began attacks on Arab villages around April 1936, thus ending the policy of restraint. These attacks were intended to instill fear in the Arab side, in order to cause the Arabs to wish for peace and quiet. In March 1938,

While continuing to defend settlements, Irgun members began attacks on Arab villages around April 1936, thus ending the policy of restraint. These attacks were intended to instill fear in the Arab side, in order to cause the Arabs to wish for peace and quiet. In March 1938,

At the same time, the Irgun also established itself in Europe. The Irgun built underground cells that participated in organizing migration to Palestine. The cells were made up almost entirely of Betar members, and their primary activity was military training in preparation for emigration to Palestine. Ties formed with the Polish authorities brought about courses in which Irgun commanders were trained by Polish officers in advanced military issues such as

At the same time, the Irgun also established itself in Europe. The Irgun built underground cells that participated in organizing migration to Palestine. The cells were made up almost entirely of Betar members, and their primary activity was military training in preparation for emigration to Palestine. Ties formed with the Polish authorities brought about courses in which Irgun commanders were trained by Polish officers in advanced military issues such as

Throughout this entire period, the British continued enforcing the

Throughout this entire period, the British continued enforcing the

In 1943 the

In 1943 the

On February 14, 1947,

On February 14, 1947,

UNSCOP's conclusion was a unanimous decision to end the British mandate, and a majority decision to divide

UNSCOP's conclusion was a unanimous decision to end the British mandate, and a majority decision to divide  In his report concerning the fall of Jaffa the local Arab military commander, Michel Issa, wrote: "Continuous shelling with mortars of the city by Jews for four days, beginning 25 April, ..caused inhabitants of city, unaccustomed to such bombardment, to panic and flee." According to Morris the shelling was done by the Irgun. Their objective was "to prevent constant military traffic in the city, to break the spirit of the enemy troops ndto cause chaos among the civilian population in order to create a mass flight."Morris, 2004, 'The Birth ... Revisited', p. 213 High Commissioner Cunningham wrote a few days later "It should be made clear that IZL attack with mortars was indiscriminate and designed to create panic among the civilian inhabitants." The British demanded the evacuation of the newly conquered city, and militarily intervened, ending the Irgun offensive. Heavy British shelling against Irgun positions in Jaffa failed to dislodge them, and when British armor pushed into the city, the Irgun resisted; a bazooka team managed to knock out one tank, buildings were blown up and collapsed onto the streets as the armor advanced, and Irgun men crawled up and tossed live dynamite sticks onto the tanks. The British withdrew, and opened negotiations with the Jewish authorities. An agreement was worked out, under which Operation Hametz would be stopped and the Haganah would not attack Jaffa until the end of the Mandate. The Irgun would evacuate Manshiya, with Haganah fighters replacing them. British troops would patrol its southern end and occupy the police fort. The Irgun had previously agreed with the Haganah that British pressure would not lead to withdrawal from Jaffa and that custody of captured areas would be turned over to the Haganah. The city ultimately fell on May 13 after Haganah forces entered the city and took control of the rest of the city, from the south – part of the ''Hametz Operation'' which included the conquest of a number of villages in the area. The battles in Jaffa were a great victory for the Irgun. This operation was the largest in the history of the organization, which took place in a highly built up area that had many militants in shooting positions. During the battles explosives were used in order to break into homes and continue forging a way through them. Furthermore, this was the first occasion in which the Irgun had directly fought British forces, reinforced with armor and heavy weaponry. The city began these battles with an Arab population estimated at 70,000, which shrank to some 4,100 Arab residents by the end of major hostilities. Since the Irgun captured the neighborhood of Manshiya on its own, causing the flight of many of Jaffa's residents, the Irgun took credit for the conquest of Jaffa. It had lost 42 dead and about 400 wounded during the battle.

In his report concerning the fall of Jaffa the local Arab military commander, Michel Issa, wrote: "Continuous shelling with mortars of the city by Jews for four days, beginning 25 April, ..caused inhabitants of city, unaccustomed to such bombardment, to panic and flee." According to Morris the shelling was done by the Irgun. Their objective was "to prevent constant military traffic in the city, to break the spirit of the enemy troops ndto cause chaos among the civilian population in order to create a mass flight."Morris, 2004, 'The Birth ... Revisited', p. 213 High Commissioner Cunningham wrote a few days later "It should be made clear that IZL attack with mortars was indiscriminate and designed to create panic among the civilian inhabitants." The British demanded the evacuation of the newly conquered city, and militarily intervened, ending the Irgun offensive. Heavy British shelling against Irgun positions in Jaffa failed to dislodge them, and when British armor pushed into the city, the Irgun resisted; a bazooka team managed to knock out one tank, buildings were blown up and collapsed onto the streets as the armor advanced, and Irgun men crawled up and tossed live dynamite sticks onto the tanks. The British withdrew, and opened negotiations with the Jewish authorities. An agreement was worked out, under which Operation Hametz would be stopped and the Haganah would not attack Jaffa until the end of the Mandate. The Irgun would evacuate Manshiya, with Haganah fighters replacing them. British troops would patrol its southern end and occupy the police fort. The Irgun had previously agreed with the Haganah that British pressure would not lead to withdrawal from Jaffa and that custody of captured areas would be turned over to the Haganah. The city ultimately fell on May 13 after Haganah forces entered the city and took control of the rest of the city, from the south – part of the ''Hametz Operation'' which included the conquest of a number of villages in the area. The battles in Jaffa were a great victory for the Irgun. This operation was the largest in the history of the organization, which took place in a highly built up area that had many militants in shooting positions. During the battles explosives were used in order to break into homes and continue forging a way through them. Furthermore, this was the first occasion in which the Irgun had directly fought British forces, reinforced with armor and heavy weaponry. The city began these battles with an Arab population estimated at 70,000, which shrank to some 4,100 Arab residents by the end of major hostilities. Since the Irgun captured the neighborhood of Manshiya on its own, causing the flight of many of Jaffa's residents, the Irgun took credit for the conquest of Jaffa. It had lost 42 dead and about 400 wounded during the battle.

There were two confrontations between the newly formed IDF and the Irgun: when ''Altalena'' reached

There were two confrontations between the newly formed IDF and the Irgun: when ''Altalena'' reached

Zionist

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

paramilitary

A paramilitary is a military that is not a part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. The Oxford English Dictionary traces the use of the term "paramilitary" as far back as 1934.

Overview

Though a paramilitary is, by definiti ...

organization that operated in Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine was a British Empire, British geopolitical entity that existed between 1920 and 1948 in the Palestine (region), region of Palestine, and after 1922, under the terms of the League of Nations's Mandate for Palestine.

After ...

between 1931 and 1948. It was an offshoot of the older and larger Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

paramilitary organization Haganah

Haganah ( , ) was the main Zionist political violence, Zionist paramilitary organization that operated for the Yishuv in the Mandatory Palestine, British Mandate for Palestine. It was founded in 1920 to defend the Yishuv's presence in the reg ...

.

The Irgun policy was based on what was then called Revisionist Zionism

Revisionist Zionism is a form of Zionism characterized by territorial maximalism. Revisionist Zionism promoted expansionism and the establishment of a Jewish majority on both sides of the Jordan River. Developed by Ze'ev Jabotinsky in the 1920s ...

founded by Ze'ev Jabotinsky

Ze'ev Jabotinsky (born Vladimir Yevgenyevich Zhabotinsky; 17 October 1880 – 3 August 1940) was a Russian-born author, poet, orator, soldier, and founder of the Revisionist Zionist movement and the Jewish Self-Defense Organization in O ...

. Two of the most infamous operations for which the Irgun were known; the bombing of the British administrative headquarters for Mandatory Palestine in Jerusalem on 22 July 1946 and the Deir Yassin massacre

The Deir Yassin massacre took place on April 9, 1948, when Zionist paramilitaries attacked the village of Deir Yassin near Jerusalem, then part of Mandatory Palestine, killing at least 107 Palestinian Arab villagers, including women and childr ...

that killed at least 107 Palestinian Arab villagers, including women and children, carried out with Lehi on 9 April 1948.

The organization committed acts of terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of violence against non-combatants to achieve political or ideological aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violence during peacetime or in the context of war aga ...

against Palestinian Arabs

Palestinians () are an Arab ethnonational group native to the Levantine region of Palestine.

*: "Palestine was part of the first wave of conquest following Muhammad's death in 632 CE; Jerusalem fell to the Caliph Umar in 638. The indigenous p ...

, as well as against the British authorities, who were regarded as illegal occupiers. In particular the Irgun was described as a terrorist organization by the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

, British, and United States governments; in media such as ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' newspaper;Pope Brewer, SamIrgun Bomb Kills 11 Arabs, 2 Britons

''New York Times''. December 30, 1947.

''New York Times''. August 16, 1947. as well as by the

Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry

The Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry was a joint British and American committee assembled in Washington, D.C., on 4 January 1946. The committee was tasked to examine political, economic and social conditions in Mandatory Palestine and the well ...

, the 1946 Zionist Congress

The Zionist Congress was established in 1897 by Theodor Herzl as the supreme organ of the Zionist Organization (ZO) and its legislative authority. In 1960 the names were changed to World Zionist Congress ( ''HaKongres HaTsioni HaOlami'') and Wor ...

and the Jewish Agency

The Jewish Agency for Israel (), formerly known as the Jewish Agency for Palestine, is the largest Jewish non-profit organization in the world. It was established in 1929 as the operative branch of the World Zionist Organization (WZO).

As an ...

. Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt (born Johanna Arendt; 14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) was a German and American historian and philosopher. She was one of the most influential political theory, political theorists of the twentieth century.

Her work ...

and Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

, in a letter to ''The New York Times'' in 1948, compared Irgun and its successor Herut

Herut () was the major conservative nationalist political party in Israel from 1948 until its formal merger into Likud in 1988. It was an adherent of Revisionist Zionism. Some of their policies were compared to those of the Nazi party.

Early y ...

party to "Nazi and Fascist parties" and described it as a "terrorist, right wing, chauvinist organization".

Following the establishment of the State of Israel

The Israeli Declaration of Independence, formally the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel (), was proclaimed on 14 May 1948 (5 Iyar 5708), at the end of the 1947–1948 civil war in Mandatory Palestine, civil war phase and ...

during the 1948 Palestine war

The 1948 Palestine war was fought in the territory of what had been, at the start of the war, British-ruled Mandatory Palestine. During the war, the British withdrew from Palestine, Zionist forces conquered territory and established the Stat ...

, the Irgun began to be absorbed into the newly created Israel Defense Forces

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the State of Israel. It consists of three service branches: the Israeli Ground Forces, the Israeli Air Force, and ...

. Conflict between the Irgun and the IDF escalated into the 1948 Altalena affair

The ''Altalena'' Affair was a violent confrontation that took place in June 1948 between the newly created Israel Defense Forces and the Irgun (also known as Etzel), one of the Jewish paramilitary groups that were in the process of merging to ...

, and the Irgun formally disbanded on January 12, 1949. The Irgun was a political predecessor to Israel's right-wing

Right-wing politics is the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position based on natural law, economics, authority, property ...

Herut (or "Freedom") party, which led to today's Likud

Likud (, ), officially known as Likud – National Liberal Movement (), is a major Right-wing politics, right-wing, political party in Israel. It was founded in 1973 by Menachem Begin and Ariel Sharon in an alliance with several right-wing par ...

party. Likud has led or been part of most Israeli government

The Israeli system of government is based on parliamentary democracy. The Prime Minister of Israel is the head of government and leader of a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government (also known as the cabinet). Legislat ...

s since 1977.

History

Members of the Irgun came mostly from

Members of the Irgun came mostly from Betar

The Betar Movement (), also spelled Beitar (), is a Revisionist Zionism, Revisionist Zionist youth movement founded in 1923 in Riga, Latvia, by Ze'ev Jabotinsky, Vladimir (Ze'ev) Jabotinsky. It was one of several right-wing youth movements tha ...

and from the Revisionist Party

Hatzohar (), full name Brit HaTzionim HaRevizionistim (), was a Revisionist Zionist organization and political party in Mandatory Palestine and newly independent Israel.

History

Hatzohar was founded by Ze'ev Jabotinsky and others in Paris in Apr ...

both in Palestine and abroad. The Revisionist Movement made up a popular backing for the underground organization. Ze'ev Jabotinsky

Ze'ev Jabotinsky (born Vladimir Yevgenyevich Zhabotinsky; 17 October 1880 – 3 August 1940) was a Russian-born author, poet, orator, soldier, and founder of the Revisionist Zionist movement and the Jewish Self-Defense Organization in O ...

, founder of Revisionist Zionism, commanded the organization until he died in 1940. He formulated the general realm of operation, regarding '' Restraint'' and the end thereof, and was the inspiration for the organization overall. An additional major source of ideological inspiration was the poetry of Uri Zvi Greenberg

Uri Zvi Greenberg (; September 22, 1896 – May 8, 1981; also spelled Uri Zvi Grinberg) was an Israeli poet, journalist and politician who wrote in Yiddish and Hebrew.

Widely regarded among the greatest poets in the country's history, he was a ...

. The symbol of the organization, with the motto רק כך (only thus), underneath a hand holding a rifle in the foreground of a map showing both Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine was a British Empire, British geopolitical entity that existed between 1920 and 1948 in the Palestine (region), region of Palestine, and after 1922, under the terms of the League of Nations's Mandate for Palestine.

After ...

and the Emirate of Transjordan

The Emirate of Transjordan (), officially the Amirate of Trans-Jordan, was a British protectorate established on 11 April 1921,British Mandate for Palestine

The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British administration of the territories of Palestine and Transjordanwhich had been part of the Ottoman Empire for four centuriesfollowing the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in Wo ...

), implied that force was the only way to "liberate the homeland."

The number of members of the Irgun varied from a few hundred to a few thousand. Most of its members were people who joined the organization's command, under which they carried out various operations and filled positions, largely in opposition to British law. Most of them were "ordinary" people, who held regular jobs, and only a few dozen worked full-time in the Irgun.

The Irgun disagreed with the policy of the Yishuv

The Yishuv (), HaYishuv Ha'ivri (), or HaYishuv HaYehudi Be'Eretz Yisra'el () was the community of Jews residing in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. The term came into use in the 1880s, when there were about 2 ...

and with the World Zionist Organization

The World Zionist Organization (; ''HaHistadrut HaTzionit Ha'Olamit''), or WZO, is a non-governmental organization that promotes Zionism. It was founded as the Zionist Organization (ZO; 1897–1960) at the initiative of Theodor Herzl at the F ...

, both with regard to strategy and basic ideology and with regard to PR and military tactics, such as use of armed force to accomplish the Zionist ends, operations against the Arabs during the riots, and relations with the British mandatory government. Therefore, the Irgun tended to ignore the decisions made by the Zionist leadership and the Yishuv's institutions. This fact caused the elected bodies not to recognize the independent organization, and during most of the time of its existence the organization was seen as irresponsible, and its actions thus worthy of thwarting. Accordingly, the Irgun accompanied its armed operations with public-relations campaigns aiming to convince the public of the Irgun's way and the problems with the official political leadership of the Yishuv. The Irgun put out numerous advertisements, an underground newspaper and even ran the first independent Hebrew radio station – Kol Zion HaLochemet.

Structure of organization

As members of an underground armed organization, Irgun personnel did not normally call Irgun by its name but rather used other names. In the first years of its existence it was known primarily as ''Ha-Haganah Leumit'' (The National Defense), and also by names such as ''Haganah Bet'' ("Second Defense"), ''Irgun Bet'' ("Second Irgun"), the ''Parallel Organization'' and the ''Rightwing Organization''. Later on it became most widely known as המעמד (the Stand). The anthem adopted by the Irgun was "Anonymous Soldiers", written by Avraham (Yair) Stern who was at the time a commander in the Irgun. Later on Stern defected from the Irgun and founded Lehi, and the song became the anthem of the Lehi. The Irgun's new anthem then became the third verse of the " Betar Song", by Ze'ev Jabotinsky. The Irgun gradually evolved from its humble origins into a serious and well-organized paramilitary organization. The movement developed a hierarchy of ranks and a sophisticated command-structure, and came to demand serious military training and strict discipline from its members. It developed clandestine networks of hidden arms-caches and weapons-production workshops, safe-houses, and training camps, along with a secret printing facility for propaganda posters. The ranks of the Irgun were (in ascending order): *''Khayal'' = (Private) *''Segen Rosh Kvutza'', ''Segen'' ("Deputy Group Leader", "Deputy") = Assistant Squad Leader (Lance Corporal

Lance corporal is a military rank, used by many English-speaking armed forces worldwide, and also by some police forces and other uniformed organisations. It is below the rank of corporal.

Etymology

The presumed origin of the rank of lance corp ...

)

*''Rosh Kvutza'' ("Group Leader") = Squad Leader (Corporal

Corporal is a military rank in use by the armed forces of many countries. It is also a police rank in some police services. The rank is usually the lowest ranking non-commissioned officer. In some militaries, the rank of corporal nominally corr ...

)

*''Samal'' ("Sergeant") = Section Leader (Sergeant

Sergeant (Sgt) is a Military rank, rank in use by the armed forces of many countries. It is also a police rank in some police services. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and in other units that draw their heritage f ...

)

*''Samal Rishon'' ("Sergeant First Class") = Brigade Leader ( Platoon Sergeant)

*''Rav Samal'' ("Chief Sergeant") = Battalion Leader (Master Sergeant

A master sergeant is the military rank for a senior non-commissioned officer in the armed forces of some countries.

Israel Defense Forces

The (abbreviated "", master sergeant) is a non-commissioned officer () rank in the Israel Defense Force ...

)

*''Gundar Sheni'', ''Gundar'' ("Commander Second Class", "Commander") = District Commander ( 2nd Lieutenant)

*''Gundar Rishon'' ("Commander First Class") = Senior Branch Commander, Headquarters Staff (Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

).

The Irgun was led by a High Command, which set policy and gave orders. Directly underneath it was a General Staff, which oversaw the activities of the Irgun. The General Staff was divided into a military and a support staff. The military staff was divided into operational units that oversaw operations and support units in charge of planning, instruction, weapons caches and manufacture, and first aid. The military and support staff never met jointly; they communicated through the High Command. Beneath the General Staff were six district commands: Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

, Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( or , ; ), sometimes rendered as Tel Aviv-Jaffa, and usually referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the Gush Dan metropolitan area of Israel. Located on the Israeli Mediterranean coastline and with a popula ...

, Haifa

Haifa ( ; , ; ) is the List of cities in Israel, third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropolitan area i ...

-Galilee

Galilee (; ; ; ) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon consisting of two parts: the Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and the Lower Galilee (, ; , ).

''Galilee'' encompasses the area north of the Mount Carmel-Mount Gilboa ridge and ...

, Southern, Sharon

Sharon ( 'plain'), also spelled Saron, is a given name as well as a Hebrew name.

In Anglosphere, English-speaking areas, Sharon is now predominantly a feminine given name, but historically it was also used as a masculine given name. In Israel, ...

, and Shomron

Samaria (), the Hellenized form of the Hebrew name Shomron (), is used as a historical and biblical name for the central region of the Land of Israel. It is bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The region is known to the ...

, each led by a district commander.Bell, Bowyer J.: ''Terror out of Zion'' (1976) A local Irgun district unit was called a "Branch". A "brigade" in the Irgun was made up of three sections. A section was made up of two groups, at the head of each was a "Group Head", and a deputy. Eventually, various units were established, which answered to a "Center" or "Staff".

The head of the Irgun High Command was the overall commander of the organization, but the designation of his rank varied. During the revolt against the British, Irgun commander Menachem Begin

Menachem Begin ( ''Menaḥem Begin'', ; (Polish documents, 1931–1937); ; 16 August 1913 – 9 March 1992) was an Israeli politician, founder of both Herut and Likud and the prime minister of Israel.

Before the creation of the state of Isra ...

and the entire High Command held the rank of ''Gundar Rishon''. His predecessors, however, had held their own ranks. A rank of Military Commander ( Seren) was awarded to the Irgun commander Yaakov Meridor

Ya'akov Meridor (; born Yaakov Viniarsky 29 September 1913 – 30 June 1995) was an Israeli politician, Irgun commander and businessman.

Biography

Yaakov Viniarsky (later Meridor) was born in the Polish town of Lipno to a Jewish family of midd ...

and a rank of High Commander (Aluf

( or "first/leader of a group" in Biblical Hebrew) is a senior military rank in the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) for officers who in other countries would have the rank of general, air marshal, or admiral. In addition to the ''aluf'' rank, fo ...

) to David Raziel

David Raziel (; 19 November 1910 – 20 May 1941) was a leader of the Zionist underground in British Mandatory Palestine and one of the founders of the Irgun.

During World War II, Irgun entered a truce with the British so they could collabora ...

. Until his death in 1940, Jabotinsky was known as the "Military Commander of the Etzel" or the ''Ha-Matzbi Ha-Elyon'' ("Supreme Commander").

Under the command of Menachem Begin, the Irgun was divided into different corps:

* ''Hayil Kravi'' (Combat Corps) – responsible for combat operations

* ''Delek'' ("Gasoline") – the intelligence section; responsible for gathering and translating intelligence, and maintaining contact with local and foreign journalists

* ''HAT'' (Planning Division) – responsible for planning activities

* ''HATAM'' (Revolutionary Publicity Corps) – responsible for printing and disseminating propaganda

The Irgun's commanders planned for it to have a regular combat force, a reserve, and shock units, but in practice there were not enough personnel for a reserve or for a shock force.

The Irgun emphasized that its fighters be highly disciplined. Strict drill exercises were carried out at ceremonies at different times, and strict attention was given to discipline, formal ceremonies and military relationships between the various ranks. The Irgun put out professional publications on combat doctrine, weaponry, leadership, drill exercises, etc. Among these publications were three books written by David Raziel, who had studied military history, techniques, and strategy:

* ''The Pistol'' (written in collaboration with Avraham Stern)

* ''The Theory of Training''

* ''Parade Ground and Field Drill''

A British analysis noted that the Irgun's discipline was "as strict as any army in the world."Hoffman, Bruce: ''Anonymous Soldiers'' (2015)

The Irgun operated a sophisticated recruitment and military-training regime. Those wishing to join had to find and make contact with a member, meaning only those who personally knew a member or were persistent could find their way in. Once contact had been established, a meeting was set up with the three-member selection committee at a safe-house, where the recruit was interviewed in a darkened room, with the committee either positioned behind a screen, or with a flashlight shone into the recruit's eyes. The interviewers asked basic biographical questions, and then asked a series of questions designed to weed out romantics and adventurers and those who had not seriously contemplated the potential sacrifices. Those selected attended a four-month series of indoctrination seminars in groups of five to ten, where they were taught the Irgun's ideology and the code of conduct it expected of its members. These seminars also had another purpose - to weed out the impatient and those of flawed purpose who had gotten past the selection interview. Then, members were introduced to other members, were taught the locations of safe-houses, and given military training. Irgun recruits trained with firearms, hand grenades, and were taught how to conduct combined attacks on targets. Arms handling and tactics courses were given in clandestine training camps, while practice shooting took place in the desert or by the sea. Eventually, separate training camps were established for heavy-weapons training. The most rigorous course was the explosives course for bomb-makers, which lasted a year. The British authorities believed that some Irgun members enlisted in the Jewish section of the Palestine Police Force

The Palestine Police Force (, ) was a British colonial police service established in Mandatory Palestine on 1 July 1920,Sinclair, 2006. when High Commissioner Sir Herbert Samuel's civil administration took over responsibility for security from ...

for a year as part of their training, during which they also passed intelligence. In addition to the Irgun's sophisticated training program, many Irgun members were veterans of the Haganah (including the Palmach

The Palmach (Hebrew: , acronym for , ''Plugot Maḥatz'', "Strike Phalanges/Companies") was the elite combined strike forces and sayeret unit of the Haganah, the paramilitary organization of the Yishuv (Jewish community) during the period of th ...

), the British Armed Forces

The British Armed Forces are the unified military, military forces responsible for the defence of the United Kingdom, its British Overseas Territories, Overseas Territories and the Crown Dependencies. They also promote the UK's wider interests ...

, and Jewish partisan groups that had waged guerrilla warfare in Nazi-occupied Europe, thus bringing significant military training and combat experience into the organization. The Irgun also operated a course for its intelligence operatives, in which recruits were taught espionage, cryptography, and analysis techniques.

Of the Irgun's members, almost all were part-time members. They were expected to maintain their civilian lives and jobs, dividing their time between their civilian lives and underground activities. There were never more than 40 full-time members, who were given a small expense stipend on which to live on. Upon joining, every member received an underground name. The Irgun's members were divided into cells, and worked with the members of their own cells. The identities of Irgun members in other cells were withheld. This ensured that an Irgun member taken prisoner could betray no more than a few comrades.

In addition to the Irgun's members in Palestine, underground Irgun cells composed of local Jews were established in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

following World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. An Irgun cell was also established in Shanghai

Shanghai, Shanghainese: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: is a direct-administered municipality and the most populous urban area in China. The city is located on the Chinese shoreline on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the ...

, home to many European-Jewish refugees. The Irgun also set up a Swiss bank account. Eli Tavin, the former head of Irgun intelligence, was appointed commander of the Irgun abroad.

In November 1947, the Jewish insurgency came to an end as the UN approved of the partition of Palestine, and the British had announced their intention to withdraw the previous month. As the British left and the 1947-48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine got underway, the Irgun came out of the underground and began to function more as a standing army rather an underground organization. It began openly recruiting, training, and raising funds, and established bases, including training facilities. It also introduced field communications and created a medical unit and supply service.

Until World War II the group armed itself with weapons purchased in Europe, primarily Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

and Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, and smuggled to Palestine. The Irgun also established workshops that manufactured spare parts and attachments for the weapons. Also manufactured were land mines and simple hand grenades. Another way in which the Irgun armed itself was theft of weapons from the British Police

Law enforcement in the United Kingdom is organised separately in each of the legal systems of the United Kingdom: England and Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. Most law enforcement duties are carried out by police, police constables of ...

and military.

Prior to World War II

Founding

The Irgun's first steps were in the aftermath of the Riots of 1929. In theJerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

branch of the Haganah there were feelings of disappointment and internal unrest towards the leadership of the movements and the Histadrut

Histadrut, fully the New General Workers' Federation () and until 1994 the General Federation of Labour in the Land of Israel (, ''HaHistadrut HaKlalit shel HaOvdim B'Eretz Yisrael''), is Israel's national trade union center and represents the m ...

(at that time the organization running the Haganah). These feelings were a result of the view that the Haganah was not adequately defending Jewish interests in the region. Likewise, critics of the leadership spoke out against alleged failures in the number of weapons, readiness of the movement and its policy of restraint and not fighting back. On April 10, 1931, commanders and equipment managers announced that they refused to return weapons to the Haganah that had been issued to them earlier, prior to the Nebi Musa holiday. These weapons were later returned by the commander of the Jerusalem branch, Avraham Tehomi

Avraham Tehomi (, also Avraham T'homi, 1903–1991) was a militant who served as a Haganah commander, and was one of the founders and first commander of the Irgun. He is best known for the assassination of Jacob Israël de Haan.

Biography

Avrah ...

, a.k.a. "Gideon". However, the commanders who decided to rebel against the leadership of the Haganah relayed a message regarding their resignations to the Vaad Leumi

The Jewish National Council (JNC; , ''Va'ad Le'umi''), also known as the Jewish People's Council and the General Council of the Jewish Community of Palestine

was the main national executive organ of the Assembly of Representatives of the Jewis ...

, and thus this schism created a new independent movement.

The leader of the new underground movement was Avraham Tehomi

Avraham Tehomi (, also Avraham T'homi, 1903–1991) was a militant who served as a Haganah commander, and was one of the founders and first commander of the Irgun. He is best known for the assassination of Jacob Israël de Haan.

Biography

Avrah ...

, alongside other founding members who were all senior commanders in the Haganah, members of Hapoel Hatzair

Hapoel Hatzair (, "The Young Worker") was a Zionist group active in Palestine from 1905 until 1930. It was founded by A.D. Gordon, Yosef Aharonovich, Yosef Sprinzak and followed a non-Marxist, Zionist, socialist agenda. Hapoel Hatzair was a ...

and of the Histadrut. Also among them was Eliyahu Ben Horin Eliahu or Eliyahu is a masculine Hebrew given name and surname of biblical origin. It means "My God is Yahweh" and derives from the prophet Elijah who, according to the Bible, lived during the reign of King Ahab (9th century BCE).

People named Elia ...

, an activist in the Revisionist Party

Hatzohar (), full name Brit HaTzionim HaRevizionistim (), was a Revisionist Zionist organization and political party in Mandatory Palestine and newly independent Israel.

History

Hatzohar was founded by Ze'ev Jabotinsky and others in Paris in Apr ...

. This group was known as the "Odessan Gang", because they previously had been members of the ''Haganah Ha'Atzmit'' of Jewish Odessa

ODESSA is an American codename (from the German language, German: ''Organisation der ehemaligen SS-Angehörigen'', meaning: Organization of Former SS Members) coined in 1946 to cover Ratlines (World War II aftermath), Nazi underground escape-pl ...

. The new movement was named ''Irgun Tsvai Leumi'', ("National Military Organization") in order to emphasize its active nature in contrast to the Haganah. Moreover, the organization was founded with the desire to become a true military organization and not just a militia

A militia ( ) is a military or paramilitary force that comprises civilian members, as opposed to a professional standing army of regular, full-time military personnel. Militias may be raised in times of need to support regular troops or se ...

as the Haganah was at the time.

In the autumn of that year the Jerusalem group merged with other armed groups affiliated with Betar

The Betar Movement (), also spelled Beitar (), is a Revisionist Zionism, Revisionist Zionist youth movement founded in 1923 in Riga, Latvia, by Ze'ev Jabotinsky, Vladimir (Ze'ev) Jabotinsky. It was one of several right-wing youth movements tha ...

. The Betar groups' center of activity was in Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( or , ; ), sometimes rendered as Tel Aviv-Jaffa, and usually referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the Gush Dan metropolitan area of Israel. Located on the Israeli Mediterranean coastline and with a popula ...

, and they began their activity in 1928 with the establishment of "Officers and Instructors School of Betar". Students at this institution had broken away from the Haganah earlier, for political reasons, and the new group called itself the "National Defense", הגנה הלאומית. During the riots of 1929 Betar youth participated in the defense of Tel Aviv neighborhoods under the command of Yermiyahu Halperin, at the behest of the Tel Aviv city hall. After the riots the Tel Avivian group expanded, and was known as "The Right Wing

Right-wing politics is the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that view certain social orders and Social stratification, hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position b ...

Organization".

After the Tel Aviv expansion another branch was established in Haifa

Haifa ( ; , ; ) is the List of cities in Israel, third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropolitan area i ...

. Towards the end of 1932 the Haganah branch of Safed

Safed (), also known as Tzfat (), is a city in the Northern District (Israel), Northern District of Israel. Located at an elevation of up to , Safed is the highest city in the Galilee and in Israel.

Safed has been identified with (), a fortif ...

also defected and joined the Irgun, as well as many members of the Maccabi sports association. At that time the movement's underground newsletter, ''Ha'Metsudah'' (the Fortress) also began publication, expressing the active trend of the movement. The Irgun also increased its numbers by expanding draft regiments of Betar – groups of volunteers, committed to two years of security and pioneer activities. These regiments were based in places that from which stemmed new Irgun strongholds in the many places, including the settlements of Yesod HaMa'ala, Mishmar HaYarden, Rosh Pina

Rosh Pina () is a lay-led Modern Orthodox Jewish congregation and synagogue that meets in the Dupont Circle neighborhood of Washington, D.C., in the United States.

The independent congregation meets for Shabbat morning services twice a month ...

, Metula

Metula () is a town in the Northern District of Israel. It abuts the Israel-Lebanon border, and had a population of in .

History Bronze and Iron Age

Metula is located near the sites of the biblical cities of Dan, Abel Beth Maacah, and Ijon ...

and Nahariya

Nahariya () is the northernmost coastal city in Israel. As of , the city had a population of .

The city was founded in 1935 by Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany.

Etymology

Nahariya takes its name from the stream of Ga'aton River, Ga'aton (riv ...

in the north; in the center – Hadera

Hadera (, ) is a city located in the Haifa District of Israel, in the northern Sharon plain, Sharon region, approximately 45 kilometers (28 miles) from the major cities of Tel Aviv and Haifa. The city is located along 7 km (5 mi) of ...

, Binyamina

Binyamina-Giv'at Ada () is a town in the Haifa District in northern Israel. It is the result of the 2003 merger between the two local councils of Binyamina and Giv'at Ada. In 2019 its population was 17,371. Before the merger, the population of ...

, Herzliya

Herzliya ( ; , / ) is an affluent List of Israeli cities, city in the Israeli coastal plain, central coast of Israel, at the northern part of the Tel Aviv District, known for its robust start-up and entrepreneurial culture. In it had a populatio ...

, Netanya

Netanya () () or Natanya (), is a city in the "Planet Bekasi" Central District (Israel), Setanyahu of Israel, Israel BAB ih, and is the capital of the surrounding Sharon plain. It is north of Tel Aviv, and south of Haifa, between the Poleg stre ...

and Kfar Saba

Kfar Saba ( ), officially Kfar Sava , is a List of Israeli cities, city in the Sharon plain, Sharon region, of the Central District (Israel), Central District of State of Israel, Israel. In 2019 it had a population of 110,456, making it the 16th-l ...

, and south of there – Rishon LeZion

Rishon LeZion ( , "First to Zion") is a city in Israel, located along the central Israeli coastal plain south of Tel Aviv. It is part of the Gush Dan metropolitan area.

Founded in 1882 by Jewish immigrants from the Russian Empire who were ...

, Rehovot

Rehovot (, / ) is a city in the Central District (Israel), Central District of Israel, about south of Tel Aviv. In it had a population of .

Etymology

Israel Belkind, founder of the Bilu (movement), Bilu movement, proposed the name "Rehovot ...

and Ness Ziona

Ness Ziona (, ''Nes Tziyona'') is a city in Central District (Israel), Central District, Israel. In it had a population of , and its jurisdiction was 15,579 dunams ().

Identification

Lying within Ness Ziona's city bounds is the ruin of the Arab ...

. Later on regiments were also active in the Old City of Jerusalem

The Old City of Jerusalem (; ) is a walled area in Jerusalem.

In a tradition that may have begun with an 1840s British map of the city, the Old City is divided into four uneven quarters: the Muslim Quarter, the Christian Quarter, the Arm ...

("the Kotel Brigades") among others. Primary training centers were based in Ramat Gan

Ramat Gan (, ) is a city in the Tel Aviv District of Israel, located east of the municipality of Tel Aviv, and is part of the Gush Dan, Gush Dan metropolitan area. It is home to a Diamond Exchange District (one of the world's major diamond exch ...

, Qastina

Qastina () was a Palestinian village, located 38 kilometers northeast of Gaza City. It was ethnically cleansed during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war.

Location

Qastina was situated on an elevated spot in a generally flat area on the coastal plain, on ...

(by Kiryat Mal'akhi

Kiryat Malakhi () also spelled Kiryat Malahi, Kiryat Malachi, or Qiryat Mal'akhi, is a city in the Southern District of Israel, northeast of Ashkelon. In it had a population of . Its jurisdiction is 4,632 dunams (~4.6 km2).

History

Qa ...

of today) and other places.

Under Tehomi's command

In 1933 there were some signs of unrest, seen by the incitement of the local Arab leadership to act against the authorities. The strong British response put down the disturbances quickly. During that time the Irgun operated in a similar manner to the Haganah and was a guarding organization. The two organizations cooperated in ways such as coordination of posts and even intelligence sharing.

Within the Irgun, Tehomi was the first to serve as "Head of the Headquarters" or "Chief Commander". Alongside Tehomi served the senior commanders, or "Headquarters" of the movement. As the organization grew, it was divided into district commands.

In August 1933 a "Supervisory Committee" for the Irgun was established, which included representatives from most of the Zionist political parties. The members of this committee were Meir Grossman (of the Hebrew State Party), Rabbi

In 1933 there were some signs of unrest, seen by the incitement of the local Arab leadership to act against the authorities. The strong British response put down the disturbances quickly. During that time the Irgun operated in a similar manner to the Haganah and was a guarding organization. The two organizations cooperated in ways such as coordination of posts and even intelligence sharing.

Within the Irgun, Tehomi was the first to serve as "Head of the Headquarters" or "Chief Commander". Alongside Tehomi served the senior commanders, or "Headquarters" of the movement. As the organization grew, it was divided into district commands.

In August 1933 a "Supervisory Committee" for the Irgun was established, which included representatives from most of the Zionist political parties. The members of this committee were Meir Grossman (of the Hebrew State Party), Rabbi Meir Bar-Ilan

Meir Bar-Ilan (; – ) was an orthodox rabbi, author, and religious Zionist activist, who served as leader of the Mizrachi movement in the United States and Mandatory Palestine. Bar-Ilan University, founded in 1955, was named in his honou ...

(of the Mizrachi Party), either Immanuel Neumann or Yehoshua Supersky (of the General Zionists

The General Zionists () were a centrist Zionist movement and a political party in Israel. The General Zionists supported the leadership of Chaim Weizmann and their views were largely colored by central European culture. The party was considered ...

) and Ze'ev Jabotinsky

Ze'ev Jabotinsky (born Vladimir Yevgenyevich Zhabotinsky; 17 October 1880 – 3 August 1940) was a Russian-born author, poet, orator, soldier, and founder of the Revisionist Zionist movement and the Jewish Self-Defense Organization in O ...

or Eliyahu Ben Horin Eliahu or Eliyahu is a masculine Hebrew given name and surname of biblical origin. It means "My God is Yahweh" and derives from the prophet Elijah who, according to the Bible, lived during the reign of King Ahab (9th century BCE).

People named Elia ...

(of Hatzohar

Hatzohar (), full name Brit HaTzionim HaRevizionistim (), was a Revisionist Zionist organization and political party in Mandatory Palestine and newly independent Israel.

History

Hatzohar was founded by Ze'ev Jabotinsky and others in Paris in Apr ...

).

In protest against, and with the aim of ending Jewish immigration to Palestine

''Aliyah'' (, ; ''ʿălīyyā'', ) is the immigration of Jews from Jewish diaspora, the diaspora to, historically, the geographical Land of Israel or the Palestine (region), Palestine region, which is today chiefly represented by the Israel ...

, the Great Arab Revolt of 1936–1939 broke out on April 19, 1936. The riots took the form of attacks by Arab rioters ambushing main roads, bombing of roads and settlements as well as property and agriculture vandalism. In the beginning, the Irgun and the Haganah generally maintained a policy of restraint, apart from a few instances. Some expressed resentment at this policy, leading up internal unrest in the two organizations. The Irgun tended to retaliate more often, and sometimes Irgun members patrolled areas beyond their positions in order to encounter attackers ahead of time. However, there were differences of opinion regarding what to do in the Haganah, as well. Due to the joining of many Betar

The Betar Movement (), also spelled Beitar (), is a Revisionist Zionism, Revisionist Zionist youth movement founded in 1923 in Riga, Latvia, by Ze'ev Jabotinsky, Vladimir (Ze'ev) Jabotinsky. It was one of several right-wing youth movements tha ...

Youth members, Jabotinsky (founder of Betar) had a great deal of influence over Irgun policy. Nevertheless, Jabotinsky was of the opinion that for moral reasons violent retaliation was not to be undertaken.

In November 1936 the Peel Commission

The Peel Commission, formally known as the Palestine Royal Commission, was a British Royal Commission of Inquiry, headed by Lord Peel, appointed in 1936 to investigate the causes of conflict in Mandatory Palestine, which was administered by t ...

was sent to inquire regarding the breakout of the riots and propose a solution to end the Revolt. In early 1937 there were still some in the Yishuv

The Yishuv (), HaYishuv Ha'ivri (), or HaYishuv HaYehudi Be'Eretz Yisra'el () was the community of Jews residing in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. The term came into use in the 1880s, when there were about 2 ...

who felt the commission would recommend a partition of Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine was a British Empire, British geopolitical entity that existed between 1920 and 1948 in the Palestine (region), region of Palestine, and after 1922, under the terms of the League of Nations's Mandate for Palestine.

After ...

(the land west of the Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan (, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn''; , ''Nəhar hayYardēn''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Sharieat'' (), is a endorheic river in the Levant that flows roughly north to south through the Sea of Galilee and drains to the Dead ...

), thus creating a Jewish state on part of the land. The Irgun leadership, as well as the "Supervisory Committee" held similar beliefs, as did some members of the Haganah and the Jewish Agency

The Jewish Agency for Israel (), formerly known as the Jewish Agency for Palestine, is the largest Jewish non-profit organization in the world. It was established in 1929 as the operative branch of the World Zionist Organization (WZO).

As an ...

. This belief strengthened the policy of restraint and led to the position that there was no room for defense institutions in the future Jewish state. Tehomi was quoted as saying: "We stand before great events: a Jewish state and a Jewish army. There is a need for a single military force". This position intensified the differences of opinion regarding the policy of restraint, both within the Irgun and within the political camp aligned with the organization. The leadership committee of the Irgun supported a merger with the Haganah. On April 24, 1937, a referendum was held among Irgun members regarding its continued independent existence. David Raziel and Avraham (Yair) Stern came out publicly in support for the continued existence of the Irgun:

The Irgun has been placed ... before a decision to make, whether to submit to the authority of the government and theJewish Agency The Jewish Agency for Israel (), formerly known as the Jewish Agency for Palestine, is the largest Jewish non-profit organization in the world. It was established in 1929 as the operative branch of the World Zionist Organization (WZO). As an ...or to prepare for a double sacrifice and endangerment. Some of our friends do not have appropriate willingness for this difficult position, and have submitted to the Jewish Agency and has left the battle ... all of the attempts ... to unite with the leftist organization have failed, because the Left entered into negotiations not on the basis of unification of forces, but the submission of one such force to the other....

The first split

In April 1937 the Irgun split after the referendum. Approximately 1,500–2,000 people, about half of the Irgun's membership, including the senior command staff, regional committee members, along with most of the Irgun's weapons, returned to the Haganah, which at that time was under the Jewish Agency's leadership. The Supervisory Committee's control over the Irgun ended, and Jabotinsky assumed command. In their opinion, the removal of the Haganah from the Jewish Agency's leadership to the national institutions necessitated their return. Furthermore, they no longer saw significant ideological differences between the movements. Those who remained in the Irgun were primarily young activists, mostly laypeople, who sided with the independent existence of the Irgun. In fact, most of those who remained were originally Betar people.Moshe Rosenberg

The Irgun (), officially the National Military Organization in the Land of Israel, often abbreviated as Etzel or IZL (), was a Zionist paramilitary organization that operated in Mandatory Palestine between 1931 and 1948. It was an offshoot of th ...

estimated that approximately 1,800 members remained. In theory, the Irgun remained an organization not aligned with a political party, but in reality the supervisory committee was disbanded and the Irgun's continued ideological path was outlined according to Ze'ev Jabotinsky's school of thought and his decisions, until the movement eventually became Revisionist Zionism's military arm. One of the major changes in policy by Jabotinsky was the end of the policy of restraint.

On April 27, 1937, the Irgun founded a new headquarters, staffed by Moshe Rosenberg at the head, Avraham (Yair) Stern as secretary, David Raziel

David Raziel (; 19 November 1910 – 20 May 1941) was a leader of the Zionist underground in British Mandatory Palestine and one of the founders of the Irgun.

During World War II, Irgun entered a truce with the British so they could collabora ...

as head of the Jerusalem branch, Hanoch Kalai

Hanoch Kalai (; March 13, 1910 – April 15, 1979) was a senior leader of Irgun and a co-founder of Lehi, and an expert on the Hebrew language. He was ''Deputy Commander in Chief'' of Irgun under David Raziel and spent three months as ''Comman ...

as commander of Haifa and Aharon Haichman as commander of Tel Aviv. On 20 Tammuz Tammuz may refer to:

* Dumuzid, Babylonian and Sumerian god

* Tammuz (Hebrew month), the 4th month of the Hebrew calendar

* Tammuz (Babylonian calendar), a month in the Babylonian calendar

* Tammuz 1 or Osirak, formerly a nuclear reactor in Iraq as ...

, (June 29) the day of Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian Jewish journalist and lawyer who was the father of Types of Zionism, modern political Zionism. Herzl formed the World Zionist Organization, Zionist Organizat ...

's death, a ceremony was held in honor of the reorganization of the underground movement. For security purposes this ceremony was held at a construction site in Tel Aviv.

Ze'ev Jabotinsky placed Col. Robert Bitker at the head of the Irgun. Bitker had previously served as Betar commissioner in China and had military experience. A few months later, probably due to total incompatibility with the position, Jabotinsky replaced Bitker with Moshe Rosenberg. When the Peel Commission

The Peel Commission, formally known as the Palestine Royal Commission, was a British Royal Commission of Inquiry, headed by Lord Peel, appointed in 1936 to investigate the causes of conflict in Mandatory Palestine, which was administered by t ...

report was published a few months later, the Revisionist camp decided not to accept the commission's recommendations. Moreover, the organizations of Betar, Hatzohar

Hatzohar (), full name Brit HaTzionim HaRevizionistim (), was a Revisionist Zionist organization and political party in Mandatory Palestine and newly independent Israel.

History

Hatzohar was founded by Ze'ev Jabotinsky and others in Paris in Apr ...

and the Irgun began to increase their efforts to bring Jews to ''Eretz Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine. The definitions ...

'' (the Land of Israel), illegally. This Aliyah

''Aliyah'' (, ; ''ʿălīyyā'', ) is the immigration of Jews from Jewish diaspora, the diaspora to, historically, the geographical Land of Israel or the Palestine (region), Palestine region, which is today chiefly represented by the Israel ...

was known as the עליית אף על פי "Af Al Pi (Nevertheless) Aliyah". As opposed to this position, the Jewish Agency began acting on behalf of the Zionist interest on the political front, and continued the policy of restraint. From this point onwards the differences between the Haganah and the Irgun were much more obvious.

Illegal immigration

According to Jabotinsky's "Evacuation Plan", which called for millions of

According to Jabotinsky's "Evacuation Plan", which called for millions of European Jews

The history of the Jews in Europe spans a period of over two thousand years. Jews, a Semitic people descending from the Judeans of Judea in the Southern Levant, Natural History 102:11 (November 1993): 12–19. began migrating to Europe just b ...

to be brought to Palestine at once, the Irgun helped the illegal immigration

Illegal immigration is the migration of people into a country in violation of that country's immigration laws, or the continuous residence in a country without the legal right to do so. Illegal immigration tends to be financially upward, wi ...

of European Jews to Palestine. This was named by Jabotinsky the "National Sport". The most significant part of this immigration prior to World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

was carried out by the Revisionist camp, largely because the Yishuv

The Yishuv (), HaYishuv Ha'ivri (), or HaYishuv HaYehudi Be'Eretz Yisra'el () was the community of Jews residing in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. The term came into use in the 1880s, when there were about 2 ...

institutions and the Jewish Agency shied away from such actions on grounds of cost and their belief that Britain would in the future allow widespread Jewish immigration.

The Irgun joined forces with Hatzohar

Hatzohar (), full name Brit HaTzionim HaRevizionistim (), was a Revisionist Zionist organization and political party in Mandatory Palestine and newly independent Israel.

History

Hatzohar was founded by Ze'ev Jabotinsky and others in Paris in Apr ...

and Betar

The Betar Movement (), also spelled Beitar (), is a Revisionist Zionism, Revisionist Zionist youth movement founded in 1923 in Riga, Latvia, by Ze'ev Jabotinsky, Vladimir (Ze'ev) Jabotinsky. It was one of several right-wing youth movements tha ...

in September 1937, when it assisted with the landing of a convoy of 54 Betar members at Tantura Beach (near Haifa

Haifa ( ; , ; ) is the List of cities in Israel, third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropolitan area i ...

.) The Irgun was responsible for discreetly bringing the Olim

''Aliyah'' (, ; ''ʿălīyyā'', ) is the immigration of Jews from the diaspora to, historically, the geographical Land of Israel or the Palestine region, which is today chiefly represented by the State of Israel. Traditionally described ...

, or Jewish immigrants, to the beaches, and dispersing them among the various Jewish settlements. The Irgun also began participating in the organisation of the immigration enterprise and undertook the process of accompanying the ships. This began with the ship ''Draga'' which arrived at the coast of British Palestine in September 1938. In August of the same year, an agreement was made between Ari Jabotinsky (the son of Ze'ev Jabotinsky), the Betar representative and Hillel Kook

Hillel Kook (; 24 July 1915 –18 August 2001), also known as Peter Bergson (Hebrew: פיטר ברגסון), was a Revisionist Zionism, Revisionist Zionist activist and politician.

Kook led the Irgun's efforts in the United States during W ...

, the Irgun representative, to coordinate the immigration (also known as Ha'apala

''Aliyah Bet'' (, "Aliyah 'B'" – bet being the second letter of the Hebrew alphabet) was the code name given to illegal immigration by Jews, many of whom were refugees escaping from Nazi Germany or other Nazi-controlled countries, and lat ...

). This agreement was also made in the "Paris Convention" in February 1939, at which Ze'ev Jabotinsky and David Raziel were present. Afterwards, the "Aliyah Center" was founded, made up of representatives of Hatzohar, Betar, and the Irgun, thereby making the Irgun a full participant in the process.

The difficult conditions on the ships demanded a high level of discipline. The people on board the ships were often split into units, led by commanders. In addition to having a daily roll call and the distribution of food and water (usually very little of either), organized talks were held to provide information regarding the actual arrival in Palestine. One of the largest ships was the ''Sakaria'', with 2,300 passengers, which equalled about 0.5% of the Jewish population in Palestine. The first vessel arrived on April 13, 1937, and the last on February 13, 1940. All told, about 18,000 Jews immigrated to Palestine with the help of the Revisionist organizations and private initiatives by other Revisionists. Most were not caught by the British.

End of restraint

While continuing to defend settlements, Irgun members began attacks on Arab villages around April 1936, thus ending the policy of restraint. These attacks were intended to instill fear in the Arab side, in order to cause the Arabs to wish for peace and quiet. In March 1938,

While continuing to defend settlements, Irgun members began attacks on Arab villages around April 1936, thus ending the policy of restraint. These attacks were intended to instill fear in the Arab side, in order to cause the Arabs to wish for peace and quiet. In March 1938, David Raziel

David Raziel (; 19 November 1910 – 20 May 1941) was a leader of the Zionist underground in British Mandatory Palestine and one of the founders of the Irgun.

During World War II, Irgun entered a truce with the British so they could collabora ...

wrote in the underground newspaper "By the Sword" a constitutive article for the Irgun overall, in which he coined the term "Active Defense":

The actions of the Haganah alone will never be a true victory. If the goal of the war is to break the will of the enemy – and this cannot be attained without destroying his spirit – clearly we cannot be satisfied with solely defensive operations.... Such a method of defense, that allows the enemy to attack at will, to reorganize and attack again ... and does not intend to remove the enemy's ability to attack a second time – is called passive defense, and ends in downfall and destruction ... whoever does not wish to be beaten has no choice but to attack. The fighting side, that does not intend to oppress but to save its liberty and honor, he too has only one way available – the way of attack. Defensiveness by way of offensiveness, in order to deprive the enemy the option of attacking, is called ''active defense''.By the end of World War II, more than 250 Arabs had been killed. Examples include: *After an Arab shooting at Carmel school in Tel Aviv, which resulted in the death of a Jewish child, Irgun members attacked an Arab neighborhood near Kerem Hatemanim in Tel Aviv, killing one Arab man and injuring another. *On August 17, the Irgun responded to shootings by Arabs from the

Jaffa

Jaffa (, ; , ), also called Japho, Joppa or Joppe in English, is an ancient Levantine Sea, Levantine port city which is part of Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel, located in its southern part. The city sits atop a naturally elevated outcrop on ...

–Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

train towards Jews that were waiting by the train block on Herzl Street in Tel Aviv. The same day, when a Jewish child was injured by the shooting, Irgun members attacked a train on the same route, killing one Arab and injuring five.

During 1936, Irgun members carried out approximately ten attacks.

Throughout 1937 the Irgun continued this line of operation.

*On March 6, a Jew at Sabbath prayers at the Western Wall

The Western Wall (; ; Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation: ''HaKosel HaMa'arovi'') is an ancient retaining wall of the built-up hill known to Jews and Christians as the Temple Mount of Jerusalem. Its most famous section, known by the same name ...

was shot by a local Arab. A few hours later, the Irgun shot at an Arab in the Jerusalem neighborhood of Rechavia.

*On June 29, a band of Arabs attacked an Egged bus on the Jerusalem – Tel Aviv road, killing one Jew. The following day, two Jews were also killed near Karkur. A few hours later, the Irgun carried out a number of operations.

**An Arab bus making its way from Lifta

Lifta (; ) was a Palestinian village on the outskirts of Jerusalem. The village's Palestinian Arab inhabitants were expelled by Zionist paramilitary forces during the 1948 Palestine war.

During the Ottoman period, the village was recorded ...

was attacked in Jerusalem.

**In two other locations in Jerusalem, Arabs were shot as well.

**In Tel Aviv, a hand grenade was thrown at an Arab coffee shop on Carmel St., injuring many of the patrons.

**Irgun members also injured an Arab on Reines St. in Tel Aviv.

**On September 5, the Irgun responded to the murder of a rabbi on his way home from prayer in the Old City of Jerusalem

The Old City of Jerusalem (; ) is a walled area in Jerusalem.

In a tradition that may have begun with an 1840s British map of the city, the Old City is divided into four uneven quarters: the Muslim Quarter, the Christian Quarter, the Arm ...

by throwing explosives at an Arab bus that had left Lifta, injuring two female passengers and a British police officer.

A more complete list can be found here

Here may refer to:

Music

* ''Here'' (Adrian Belew album), 1994

* ''Here'' (Alicia Keys album), 2016

* ''Here'' (Cal Tjader album), 1979

* ''Here'' (Edward Sharpe album), 2012

* ''Here'' (Idina Menzel album), 2004

* ''Here'' (Merzbow album), ...

.

At that time, however, these acts were not yet a part of a formulated policy of the Irgun. Not all of the aforementioned operations received a commander's approval, and Jabotinsky was not in favor of such actions at the time. Jabotinsky still hoped to establish a Jewish force out in the open that would not have to operate underground. However, the failure, in its eyes, of the Peel Commission

The Peel Commission, formally known as the Palestine Royal Commission, was a British Royal Commission of Inquiry, headed by Lord Peel, appointed in 1936 to investigate the causes of conflict in Mandatory Palestine, which was administered by t ...

and the renewal of violence on the part of the Arabs caused the Irgun to rethink its official policy.

Increase in operations

14 November 1937 was a watershed in Irgun activity. From that date, the Irgun increased its reprisals. Following an increase in the number of attacks aimed at Jews, including the killing of fivekibbutz

A kibbutz ( / , ; : kibbutzim / ) is an intentional community in Israel that was traditionally based on agriculture. The first kibbutz, established in 1910, was Degania Alef, Degania. Today, farming has been partly supplanted by other economi ...

members near Kiryat Anavim

Kiryat Anavim () is a kibbutz in the Judean Hills of Israel. It was the first kibbutz established in the Judean Hills. It is located west of Jerusalem, and falls under the jurisdiction of the Mateh Yehuda Regional Council. In it had a population ...

(today kibbutz Ma'ale HaHamisha

Ma'ale HaHamisha () is a kibbutz in central Israel. Located in the Judean hills just off the Jerusalem–Tel Aviv highway, It falls under the jurisdiction of Mateh Yehuda Regional Council. In it had a population of .

History

The kibbutz was fou ...

), the Irgun undertook a series of attacks in various places in Jerusalem, killing five Arabs. Operations were also undertaken in Haifa

Haifa ( ; , ; ) is the List of cities in Israel, third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropolitan area i ...

(shooting at the Arab-populated Wadi Nisnas

Wadi Nisnas (; ) is a predominantly Arab neighborhood in the city of Haifa, with a population of about 8,000 inhabitants.

Etymology

'Wadi' is the Arabic word for valley, and 'nisnas' means mongoose, with the Egyptian mongoose being indigenous ...

neighborhood) and in Herzliya

Herzliya ( ; , / ) is an affluent List of Israeli cities, city in the Israeli coastal plain, central coast of Israel, at the northern part of the Tel Aviv District, known for its robust start-up and entrepreneurial culture. In it had a populatio ...

. The date is known as the day the policy of restraint (Havlagah

''Havlagah'' ( , ) was the strategic policy of the Yishuv during the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine. It called for Zionist militants to abstain from engaging in acts of retaliatory violence against Palestinian Arabs in the face of Arab a ...

) ended, or as Black Sunday when operations resulted in the murder of 10 Arabs. This is when the organization fully changed its policy, with the approval of Jabotinsky and Headquarters to the policy of "active defense" in respect of Irgun actions.

The British responded with the arrest of Betar and Hatzohar members as suspected members of the Irgun. Military court

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

s were allowed to act under "Time of Emergency Regulations" and even sentence people to death. In this manner Yehezkel Altman, a guard in a Betar battalion in the Nahalat Yizchak neighborhood of Tel Aviv, shot at an Arab bus, without his commanders' knowledge. Altman was acting in response to a shooting at Jewish vehicles on the Tel Aviv–Jerusalem road the day before. He turned himself in later and was sentenced to death, a sentence which was later commuted to a life sentence.

Despite the arrests, Irgun members continued fighting. Jabotinsky lent his moral support to these activities. In a letter to Moshe Rosenberg on 18 March 1938 he wrote:

Tell them: from afar I collect and save, as precious treasures, news items about your lives. I know of the obstacles that have not impeded your spirit; and I know of your actions as well. I am overjoyed that I have been blessed with such students.Although the Irgun continued activities such as these, following Rosenberg's orders, they were greatly curtailed. Furthermore, in fear of the British threat of the death sentence for anyone found carrying a weapon, all operations were suspended for eight months. However, opposition to this policy gradually increased. In April, 1938, responding to the killing of six Jews, Betar members from the

Rosh Pina

Rosh Pina () is a lay-led Modern Orthodox Jewish congregation and synagogue that meets in the Dupont Circle neighborhood of Washington, D.C., in the United States.

The independent congregation meets for Shabbat morning services twice a month ...

Brigade went on a reprisal mission, without the consent of their commander, as described by historian Avi Shlaim

Avi Shlaim (, ; born 31 October 1945) is an Israeli and British historian of Iraqi Jewish descent. He is one of Israel's " New Historians", a group of Israeli scholars who put forward critical interpretations of the history of Zionism and Isr ...

: