Hydrolab on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Underwater habitats are

Underwater habitats are

The first aquanaut was Robert Stenuit in the Man-in-the-Sea I project run by Edwin A. Link. On 6 September 1962, he spent 24 hours and 15 minutes at a depth of in a steel cylinder, doing several excursions. In June 1964 Stenuit and Jon Lindbergh spent 49 hours at a depth of in the Man-in-the-Sea II program. The habitat consisted of a submerged portable inflatable dwelling (SPID).

The first aquanaut was Robert Stenuit in the Man-in-the-Sea I project run by Edwin A. Link. On 6 September 1962, he spent 24 hours and 15 minutes at a depth of in a steel cylinder, doing several excursions. In June 1964 Stenuit and Jon Lindbergh spent 49 hours at a depth of in the Man-in-the-Sea II program. The habitat consisted of a submerged portable inflatable dwelling (SPID).

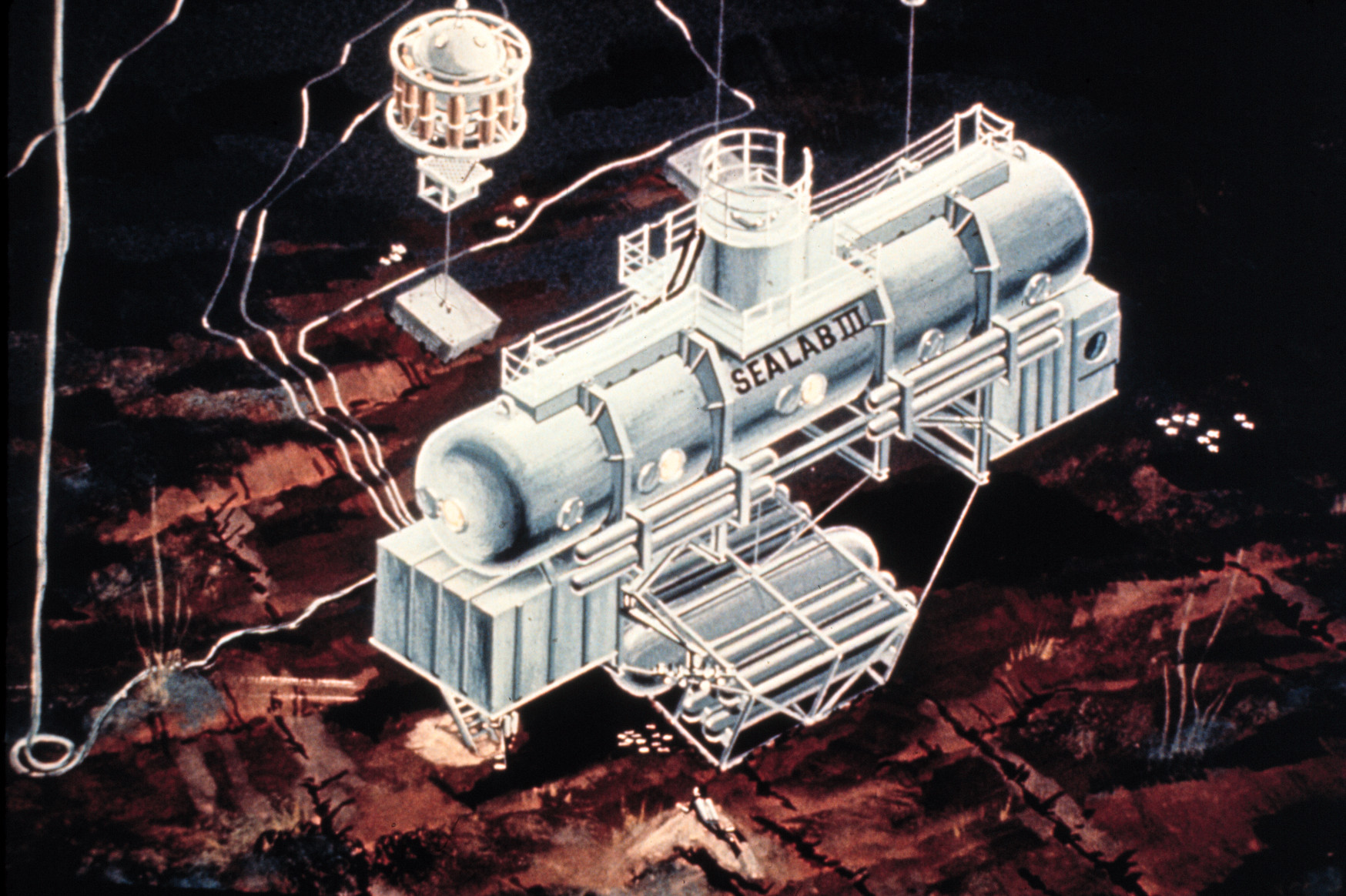

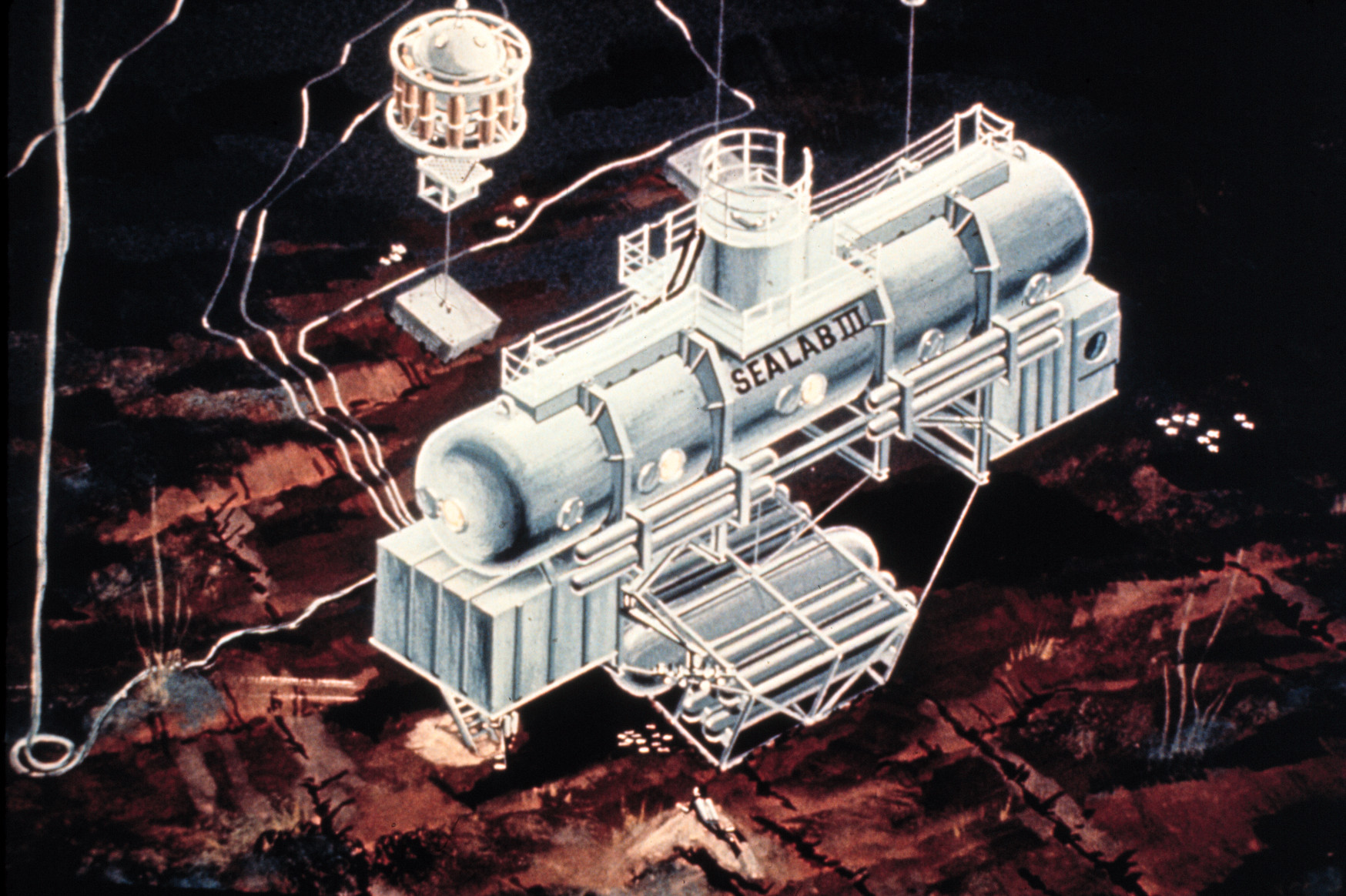

SEALAB I, II, and III were experimental underwater habitats developed by the

SEALAB I, II, and III were experimental underwater habitats developed by the

The Engineering Design and Analysis Laboratory Habitat was a horizontal cylinder 2.6 m high, 3.3 m long and weighing 14 tonnes was built by students of the Engineering Design and Analysis Laboratory in the US at a cost of $20,000 or $187,000 in today's currency. From 26 April 1968, four students spent 48 hours and 6 minutes in this habitat in Alton Bay, New Hampshire. Two further missions followed to 12.2 m.

In the 1972 Edalhab II Florida Aquanaut Research Expedition experiments, the University of New Hampshire and NOAA used

The Engineering Design and Analysis Laboratory Habitat was a horizontal cylinder 2.6 m high, 3.3 m long and weighing 14 tonnes was built by students of the Engineering Design and Analysis Laboratory in the US at a cost of $20,000 or $187,000 in today's currency. From 26 April 1968, four students spent 48 hours and 6 minutes in this habitat in Alton Bay, New Hampshire. Two further missions followed to 12.2 m.

In the 1972 Edalhab II Florida Aquanaut Research Expedition experiments, the University of New Hampshire and NOAA used

The Italian ''Progetto Abissi'' habitat, also known as ''La Casa in Fondo al Mare'' (Italian for The House at the Bottom of the Sea), was designed by the diving team Explorer Team Pellicano, consisted of three cylindrical chambers and served as a platform for a television game show. It was deployed for the first time in September 2005 for ten days, and six aquanauts lived in the complex for 14 days in 2007.

The Italian ''Progetto Abissi'' habitat, also known as ''La Casa in Fondo al Mare'' (Italian for The House at the Bottom of the Sea), was designed by the diving team Explorer Team Pellicano, consisted of three cylindrical chambers and served as a platform for a television game show. It was deployed for the first time in September 2005 for ten days, and six aquanauts lived in the complex for 14 days in 2007.

The Aquarius Reef Base is an underwater habitat located 5.4 miles (9 kilometers) off

The Aquarius Reef Base is an underwater habitat located 5.4 miles (9 kilometers) off

The Scott Carpenter Space Analog Station was launched near Key Largo on six-week missions in 1997 and 1998. The station was a NASA project illustrating the analogous science and engineering concepts common to both undersea and space missions. During the missions, some 20 aquanauts rotated through the undersea station including NASA scientists, engineers and director

The Scott Carpenter Space Analog Station was launched near Key Largo on six-week missions in 1997 and 1998. The station was a NASA project illustrating the analogous science and engineering concepts common to both undersea and space missions. During the missions, some 20 aquanauts rotated through the undersea station including NASA scientists, engineers and director

Ithaa (

Ithaa (

The "Red Sea Star" restaurant in Eilat, Israel, consisted of three modules: an entrance area above the water surface, a restaurant with 62 panorama windows 6 m under water and a ballast area below. The entire construction weighs about 6000 tons. The restaurant had a capacity of 105 people. It shut down in 2012.

The "Red Sea Star" restaurant in Eilat, Israel, consisted of three modules: an entrance area above the water surface, a restaurant with 62 panorama windows 6 m under water and a ballast area below. The entire construction weighs about 6000 tons. The restaurant had a capacity of 105 people. It shut down in 2012.

The first part of

The first part of

Alpha Deep SeaPod is located off the coast of

Alpha Deep SeaPod is located off the coast of

Gregory Stone: "Deep Science".

National Geographic Online Extra (Sept 2003). Retrieved 29 July 2007. *BBC.

Living under the sea

'

{{Underwater diving, divsup Pressure vessels

underwater

An underwater environment is a environment of, and immersed in, liquid water in a natural or artificial feature (called a Water, body of water), such as an ocean, sea, lake, pond, reservoir, river, canal, or aquifer. Some characteristics of the ...

structures in which people can live for extended periods and carry out most of the basic human functions of a 24-hour day, such as working, resting, eating, attending to personal hygiene, and sleeping. In this context, 'habitat

In ecology, habitat refers to the array of resources, biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species' habitat can be seen as the physical manifestation of its ...

' is generally used in a narrow sense to mean the interior and immediate exterior of the structure and its fixtures, but not its surrounding marine environment

A marine habitat is a habitat that supports marine life. Marine life depends in some way on the saltwater that is in the sea (the term ''marine'' comes from the Latin ''mare'', meaning sea or ocean). A habitat is an ecological or environmen ...

. Most early underwater habitats lacked regenerative systems for air, water, food, electricity, and other resources. However, some underwater habitats allow for these resources to be delivered using pipes, or generated within the habitat, rather than manually delivered.

An underwater habitat has to meet the needs of human physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

and provide suitable environmental

Environment most often refers to:

__NOTOC__

* Natural environment, referring respectively to all living and non-living things occurring naturally and the physical and biological factors along with their chemical interactions that affect an organism ...

conditions, and the one which is most critical is breathing gas

A breathing gas is a mixture of gaseous chemical elements and compounds used for respiration. Air is the most common and only natural breathing gas, but other mixtures of gases, or pure oxygen, are also used in breathing equipment and enclosed ...

of suitable quality. Others concern the physical environment

The natural environment or natural world encompasses all biotic and abiotic things occurring naturally, meaning in this case not artificial. The term is most often applied to Earth or some parts of Earth. This environment encompasses the int ...

(pressure

Pressure (symbol: ''p'' or ''P'') is the force applied perpendicular to the surface of an object per unit area over which that force is distributed. Gauge pressure (also spelled ''gage'' pressure)The preferred spelling varies by country and eve ...

, temperature

Temperature is a physical quantity that quantitatively expresses the attribute of hotness or coldness. Temperature is measurement, measured with a thermometer. It reflects the average kinetic energy of the vibrating and colliding atoms making ...

, light

Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be visual perception, perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400– ...

, humidity

Humidity is the concentration of water vapor present in the air. Water vapor, the gaseous state of water, is generally invisible to the human eye. Humidity indicates the likelihood for precipitation (meteorology), precipitation, dew, or fog t ...

), the chemical environment

A chemical substance is a unique form of matter with constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Chemical substances may take the form of a single element or chemical compounds. If two or more chemical substances can be combined ...

(drinking water

Drinking water or potable water is water that is safe for ingestion, either when drunk directly in liquid form or consumed indirectly through food preparation. It is often (but not always) supplied through taps, in which case it is also calle ...

, food

Food is any substance consumed by an organism for Nutrient, nutritional support. Food is usually of plant, animal, or Fungus, fungal origin and contains essential nutrients such as carbohydrates, fats, protein (nutrient), proteins, vitamins, ...

, waste product

Waste are unwanted or unusable materials. Waste is any substance discarded after primary use, or is worthless, defective and of no use. A by-product, by contrast is a joint product of relatively minor economic value. A waste product may beco ...

s, toxin

A toxin is a naturally occurring poison produced by metabolic activities of living cells or organisms. They occur especially as proteins, often conjugated. The term was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849–1919), derived ...

s) and the biological environment (hazardous sea creatures, microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic scale, microscopic size, which may exist in its unicellular organism, single-celled form or as a Colony (biology)#Microbial colonies, colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen ...

s, marine fungi

Marine fungi are species of fungi that live in marine or estuarine environments. They are not a taxonomic group, but share a common habitat. Obligate marine fungi grow exclusively in the marine habitat while wholly or sporadically submerged in ...

). Much of the science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

covering underwater habitats and their technology

Technology is the application of Conceptual model, conceptual knowledge to achieve practical goals, especially in a reproducible way. The word ''technology'' can also mean the products resulting from such efforts, including both tangible too ...

designed to meet human requirements is shared with diving

Diving most often refers to:

* Diving (sport), the sport of jumping into deep water

* Underwater diving, human activity underwater for recreational or occupational purposes

Diving or Dive may also refer to:

Sports

* Dive (American football), ...

, diving bell

A diving bell is a rigid chamber used to transport divers from the surface to depth and back in open water, usually for the purpose of performing underwater work. The most common types are the open-bottomed wet bell and the closed bell, which c ...

s, submersible vehicles and submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

s, and spacecraft

A spacecraft is a vehicle that is designed spaceflight, to fly and operate in outer space. Spacecraft are used for a variety of purposes, including Telecommunications, communications, Earth observation satellite, Earth observation, Weather s ...

.

Numerous underwater habitats have been designed, built and used around the world since as early as the start of the 1960s, either by private individuals or by government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

agencies. They have been used almost exclusively for research

Research is creative and systematic work undertaken to increase the stock of knowledge. It involves the collection, organization, and analysis of evidence to increase understanding of a topic, characterized by a particular attentiveness to ...

and exploration

Exploration is the process of exploring, an activity which has some Expectation (epistemic), expectation of Discovery (observation), discovery. Organised exploration is largely a human activity, but exploratory activity is common to most organis ...

, but, in recent years, at least one underwater habitat has been provided for recreation

Recreation is an activity of leisure, leisure being discretionary time. The "need to do something for recreation" is an essential element of human biology and psychology. Recreational activities are often done for happiness, enjoyment, amusement, ...

and tourism

Tourism is travel for pleasure, and the Commerce, commercial activity of providing and supporting such travel. World Tourism Organization, UN Tourism defines tourism more generally, in terms which go "beyond the common perception of tourism as ...

. Research has been devoted particularly to the physiological processes and limits of breathing gases under pressure, for aquanaut

An aquanaut is any person who remains underwater, breathing at the ambient pressure for long enough for the concentration of the inert components of the breathing gas dissolved in the body tissues to reach equilibrium, in a state known as sat ...

, as well as astronaut

An astronaut (from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'star', and (), meaning 'sailor') is a person trained, equipped, and deployed by a List of human spaceflight programs, human spaceflight program to serve as a commander or crew member of a spa ...

training, and for research on marine ecosystems.

Terminology and scope

The term 'underwater habitat' is used for a range of applications, including some structures that are not exclusively underwater while operational, but all include a significant underwater component. There may be some overlap between underwater habitats and submersible vessels, and between structures which are completely submerged and those which have some part extending above the surface when in operation. In 1970 G. Haux stated:At this point it must also be said that it is not easy to sharply define the term "underwater laboratory". One may argue whether Link's diving chamber which was used in the "Man-in-Sea I" project, may be called an underwater laboratory. But the Bentos 300, planned by the Soviets, is not so easy to classify as it has a certain ability to maneuver. Therefore, the possibility exists that this diving hull is classified elsewhere as a submersible. Well, a certain generosity can not hurt.

Comparison with surface based diving operations

In an underwater habitat, observations can be carried out at any hour to study the behavior of both diurnal and nocturnal organisms. Habitats in shallow water can be used to accommodate divers from greater depths for a major portion of the decompression required. This principle was used in the project Conshelf II. Saturation dives provide the opportunity to dive with shorter intervals than possible from the surface, and risks associated with diving and ship operations at night can be minimized. In the habitat ''La Chalupa'', 35% of all dives took place at night. To perform the same amount of useful work diving from the surface instead of from ''La Chalupa'', an estimated eight hours of decompression time would have been necessary every day. However, maintaining an underwater habitat is much more expensive and logistically difficult than diving from the surface. It also restricts the diving to a much more limited area.Technical classification and description

Architectural variations

Pressure modes

Underwater habitats are designed to operate in two fundamental modes. #Open to ambient pressure via amoon pool

A moon pool is an equipment deployment and retrieval feature used by oil platforms, marine drilling platforms, drillships, diving support vessels, fishing vessels, oceanography, marine research and underwater exploration or research vessels, and ...

, meaning the air pressure inside the habitat equals underwater pressure at the same level, such as SEALAB

SEALAB I, II, and III were experimental underwater habitats developed and deployed by the United States Navy during the 1960s to prove the viability of saturation diving and humans living in isolation for extended periods of time. The knowledge ...

. This makes entry and exit easy as there is no physical barrier other than the moon pool water surface. Living in ambient pressure habitats is a form of saturation diving

Saturation diving is an ambient pressure diving technique which allows a diver to remain at working depth for extended periods during which the body tissues become solubility, saturated with metabolically inert gas from the breathing gas mixture ...

, and return to the surface will require appropriate decompression.

#Closed to the sea by hatches, with internal air pressure less than ambient pressure and at or closer to atmospheric pressure

Atmospheric pressure, also known as air pressure or barometric pressure (after the barometer), is the pressure within the atmosphere of Earth. The standard atmosphere (symbol: atm) is a unit of pressure defined as , which is equivalent to 1,013. ...

; entry or exit to the sea requires passing through hatches and an airlock

An airlock is a room or compartment which permits passage between environments of differing atmospheric pressure or composition, while minimizing the changing of pressure or composition between the differing environments.

An airlock consist ...

. Decompression may be necessary when entering the habitat after a dive. This would be done in the airlock.

A third or composite type has compartments of both types within the same habitat structure and connected via airlocks, such as Aquarius.

Components

Excursions

An excursion is a visit to the environment outside the habitat. Diving excursions can be done on scuba or umbilical supply, and are limited upwards by decompression obligations while on the excursion, and downwards by decompression obligations while returning from the excursion. Open circuit or rebreather scuba have the advantage of mobility, but it is critical to the safety of a saturation diver to be able to get back to the habitat, as surfacing directly from saturation is likely to cause severe and probably fatal decompression sickness. For this reason, in most of the programs, signs andguidelines

A guideline is a statement by which to determine a course of action. It aims to streamline particular processes according to a set routine or sound practice. They may be issued by and used by any organization (governmental or private) to make ...

are installed around the habitat in order to prevent divers from getting lost.

Umbilicals or airline hoses are safer, as the breathing gas supply is unlimited, and the hose is a guideline back to the habitat, but they restrict freedom of movement and can become tangled.

The horizontal extent of excursions is limited by the scuba air supply or the length of the umbilical. The distance above and below the level of the habitat are also limited and depend on the depth of the habitat and the associated saturation of the divers. The volume of the underwater environment available for excursions thus takes the shape of a vertical axis cylinder centred on the habitat.

As an example, in the Tektite I program, the habitat was located at a depth of . Excursions were limited vertically to a depth of (6.4 m above the habitat) and (12.8 m below the habitat level) and were horizontally limited to a distance of from the Habitat.

History

The history of underwater habitats follows on from the previous development ofdiving bell

A diving bell is a rigid chamber used to transport divers from the surface to depth and back in open water, usually for the purpose of performing underwater work. The most common types are the open-bottomed wet bell and the closed bell, which c ...

s and caissons

Caisson (French for "box") may refer to:

* Caisson (engineering), a sealed underwater structure

* Caisson (vehicle), a two-wheeled cart for carrying ammunition, also used in certain state and military funerals

* Caisson (Asian architecture), a sp ...

, and as long exposure to a hyperbaric

Hyperbaric medicine is medical treatment in which an increase in barometric pressure of typically air or oxygen is used. The immediate effects include reducing the size of gas emboli and raising the partial pressures of the gases present. Initial ...

environment results in saturation of the body tissues with the ambient inert gases, it is also closely connected to the history of saturation diving

Saturation diving is an ambient pressure diving technique which allows a diver to remain at working depth for extended periods during which the body tissues become solubility, saturated with metabolically inert gas from the breathing gas mixture ...

. The original inspiration for the development of underwater habitats was the work of George F. Bond

Captain George Foote Bond (November 14, 1915 – January 3, 1983) was a United States Navy physician who was known as a leader in the field of undersea and hyperbaric medicine and the "Father of Saturation Diving".

While serving as Officer-in-C ...

, who investigated the physiological and medical effects of hyperbaric saturation in the Genesis project

Genesis may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Genesis, the first book of the biblical scriptures of both Judaism and Christianity, describing the creation of the Earth and of humankind

* Genesis creation narrative, the first several chapters of the Bo ...

between 1957 and 1963.

Edwin Albert Link

Edwin Albert Link (July 26, 1904 – September 7, 1981) was an American inventor, entrepreneur and pioneer in aviation, underwater archaeology, and submersibles. He invented the flight simulator, which was called the "Blue Box" or " Link Trai ...

started the Man-in-the-Sea project in 1962, which exposed divers to hyperbaric conditions underwater in a diving chamber, culminating in the first aquanaut

An aquanaut is any person who remains underwater, breathing at the ambient pressure for long enough for the concentration of the inert components of the breathing gas dissolved in the body tissues to reach equilibrium, in a state known as sat ...

, Robert Sténuit

Robert Pierre André Sténuit (16 July 1933 – 9 December 2024) was a Belgian journalist, writer, and underwater archeologist. In 1962, he spent 24 hours on the floor of the Mediterranean Sea in the submersible "Link Cylinder" developed by Edwin ...

, spending over 24 hours at a depth of .

Also inspired by Genesis, Jacques-Yves Cousteau

Jacques-Yves Cousteau, (, also , ; 11 June 191025 June 1997) was a French naval officer, oceanographer, filmmaker and author. He co-invented the first successful open-circuit self-contained underwater breathing apparatus (SCUBA), called the A ...

conducted the first Conshelf project in France in 1962 where two divers spent a week at a depth of , followed in 1963 by Conshelf II

Continental Shelf Station Two or Conshelf Two was an attempt at creating an environment in which people could live and work on the sea floor. It was the successor to Continental Shelf Station One (Conshelf One).

The alternate designation Precont ...

at for a month and for two weeks.

In June 1964, Robert Sténuit and Jon Lindberg spent 49 hours at 126m in Link's Man-in-the-Sea II project. The habitat was an inflatable structure called SPID.

This was followed by a series of underwater habitats where people stayed for several weeks at great depths. Sealab II had a usable area of , and was used at a depth of more than . Several countries built their own habitats at much the same time and mostly began experimenting in shallow waters. In Conshelf III six aquanauts lived for several weeks at a depth of . In Germany, the Helgoland UWL was the first habitat to be used in cold water, the Tektite stations were more spacious and technically more advanced. The most ambitious project was Sealab III, a rebuild of Sealab II, which was to be operated at . When one of the divers died in the preparatory phase due to human error, all similar projects of the United States Navy were terminated. Internationally, except for the La Chalupa Research Laboratory the large-scale projects were carried out, but not extended, so that the subsequent habitats were smaller and designed for shallower depths. The race for greater depths, longer missions and technical advances seemed to have come to an end.

For reasons such as lack of mobility, lack of self-sufficiency, shifting focus to space travel and transition to surface-based saturation systems, the interest in underwater habitats decreased, resulting in a noticeable decrease in major projects after 1970. In the mid eighties, the Aquarius habitat was built in the style of Sealab and Helgoland and is still in operation today.

Historical underwater habitats

Man-in-the-Sea I and II

The first aquanaut was Robert Stenuit in the Man-in-the-Sea I project run by Edwin A. Link. On 6 September 1962, he spent 24 hours and 15 minutes at a depth of in a steel cylinder, doing several excursions. In June 1964 Stenuit and Jon Lindbergh spent 49 hours at a depth of in the Man-in-the-Sea II program. The habitat consisted of a submerged portable inflatable dwelling (SPID).

The first aquanaut was Robert Stenuit in the Man-in-the-Sea I project run by Edwin A. Link. On 6 September 1962, he spent 24 hours and 15 minutes at a depth of in a steel cylinder, doing several excursions. In June 1964 Stenuit and Jon Lindbergh spent 49 hours at a depth of in the Man-in-the-Sea II program. The habitat consisted of a submerged portable inflatable dwelling (SPID).

Conshelf I, II and III

Conshelf, short for Continental Shelf Station, was a series of undersea living and research stations undertaken by Jacques Cousteau's team in the 1960s. The original design was for five of these stations to be submerged to a maximum depth of over the decade; in reality only three were completed with a maximum depth of . Much of the work was funded in part by the Frenchpetrochemical industry

file:Jampilen Petrochemical Co. 02.jpg, 300px, Jampilen Petrochemical co., Asaluyeh, Iran

The petrochemical industry is concerned with the production and trade of petrochemicals. A major part is constituted by the plastics industry, plastics (poly ...

, who, along with Cousteau, hoped that such colonies could serve as base stations for the future exploitation of the sea. Such colonies did not find a productive future, however, as Cousteau later repudiated his support for such exploitation of the sea and put his efforts toward conservation. It was also found in later years that industrial tasks underwater could be more efficiently performed by undersea robot devices and men operating from the surface or from smaller lowered structures, made possible by a more advanced understanding of diving physiology. Still, these three undersea living experiments did much to advance man's knowledge of undersea technology and physiology, and were valuable as "proof of concept

A proof of concept (POC or PoC), also known as proof of principle, is an inchoate realization of a certain idea or method in order to demonstrate its feasibility or viability. A proof of concept is usually small and may or may not be complete ...

" constructs. They also did much to publicize oceanographic research and, ironically, usher in an age of ocean conservation through building public awareness. Along with Sealab and others, it spawned a generation of smaller, less ambitious yet longer-term undersea habitats primarily for marine research purposes.

Conshelf I (Continental Shelf Station), constructed in 1962, was the first inhabited underwater habitat. Developed by Cousteau to record basic observations of life underwater, Conshelf I was submerged in of water near Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

, and the first experiment involved a team of two spending seven days in the habitat. The two oceanauts, Albert Falco and Claude Wesly, were expected to spend at least five hours a day outside the station, and were subject to daily medical exams.

Conshelf Two, the first ambitious attempt for men to live and work on the sea floor, was launched in 1963. In it, a half-dozen oceanauts lived down in the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

off Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

in a starfish

Starfish or sea stars are Star polygon, star-shaped echinoderms belonging to the class (biology), class Asteroidea (). Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to brittle star, ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to ...

-shaped house for 30 days. The undersea living experiment also had two other structures, one a submarine hangar that housed a small, two-man submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

named SP-350 Denise

The SP-350 ''Denise'', famous as the "Diving saucer" (''Soucoupe plongeante''), is a small submarine designed to hold two people, and is capable of exploring depths of up to . It was invented by Jacques-Yves Cousteau and engineer Jean Mollard at t ...

, often referred to as the "diving saucer" for its resemblance to a science fiction flying saucer, and a smaller "deep cabin" where two oceanauts lived at a depth of for a week. They were among the first to breathe heliox

Heliox is a breathing gas mixture of helium (He) and oxygen (O2). It is used as a medical treatment for patients with difficulty breathing because this mixture generates less resistance than atmospheric air when passing through the airways of ...

, a mixture of helium and oxygen, avoiding the normal nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a Nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal and the lightest member of pnictogen, group 15 of the periodic table, often called the Pnictogen, pnictogens. ...

/oxygen mixture, which, when breathed under pressure, can cause narcosis. The deep cabin was also an early effort in saturation diving

Saturation diving is an ambient pressure diving technique which allows a diver to remain at working depth for extended periods during which the body tissues become solubility, saturated with metabolically inert gas from the breathing gas mixture ...

, in which the aquanauts' body tissues were allowed to become totally saturated by the helium in the breathing mixture, a result of breathing the gases under pressure. The necessary decompression from saturation was accelerated by using oxygen enriched breathing gases. They suffered no apparent ill effects.

The undersea colony was supported with air, water, food, power, all essentials of life, from a large support team above. Men on the bottom performed a number of experiments intended to determine the practicality of working on the sea floor and were subjected to continual medical examinations. Conshelf II was a defining effort in the study of diving physiology and technology, and captured wide public appeal due to its dramatic "Jules Verne

Jules Gabriel Verne (;''Longman Pronunciation Dictionary''. ; 8 February 1828 – 24 March 1905) was a French novelist, poet and playwright.

His collaboration with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel led to the creation of the ''Voyages extraor ...

" look and feel. A Cousteau-produced feature film about the effort (World Without Sun

''World Without Sun'' () is a 1964 French documentary film directed by Jacques-Yves Cousteau. The film was Cousteau's second to win the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature, following ''The Silent World'' in 1956.

Content

The film chronicle ...

) was awarded an Academy Award for Best Documentary the following year.

Conshelf III was initiated in 1965. Six divers lived in the habitat at in the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

near the Cap Ferrat lighthouse, between Nice and Monaco, for three weeks. In this effort, Cousteau was determined to make the station more self-sufficient, severing most ties with the surface. A mock oil rig

An oil rig is any kind of apparatus constructed for oil drilling.

Kinds of oil rig include:

* Drilling rig

A drilling rig is an integrated system that Drilling, drills wells, such as oil or water wells, or holes for piling and other construc ...

was set up underwater, and divers successfully performed several industrial tasks.

SEALAB I, II and III

SEALAB I, II, and III were experimental underwater habitats developed by the

SEALAB I, II, and III were experimental underwater habitats developed by the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

in the 1960s to prove the viability of saturation diving

Saturation diving is an ambient pressure diving technique which allows a diver to remain at working depth for extended periods during which the body tissues become solubility, saturated with metabolically inert gas from the breathing gas mixture ...

and humans living in isolation for extended periods of time. The knowledge gained from the SEALAB expeditions helped advance the science of deep sea diving

Underwater diving, as a human activity, is the practice of descending below the water's surface to interact with the environment. It is also often referred to as diving, an ambiguous term with several possible meanings, depending on context ...

and rescue, and contributed to the understanding of the psychological and physiological strains humans can endure. The three SEALABs were part of the United States Navy Genesis Project. Preliminary research work was undertaken by George F. Bond

Captain George Foote Bond (November 14, 1915 – January 3, 1983) was a United States Navy physician who was known as a leader in the field of undersea and hyperbaric medicine and the "Father of Saturation Diving".

While serving as Officer-in-C ...

. Bond began investigations in 1957 to develop theories about saturation diving

Saturation diving is an ambient pressure diving technique which allows a diver to remain at working depth for extended periods during which the body tissues become solubility, saturated with metabolically inert gas from the breathing gas mixture ...

. Bond's team exposed rat

Rats are various medium-sized, long-tailed rodents. Species of rats are found throughout the order Rodentia, but stereotypical rats are found in the genus ''Rattus''. Other rat genera include '' Neotoma'' (pack rats), '' Bandicota'' (bandicoo ...

s, goat

The goat or domestic goat (''Capra hircus'') is a species of Caprinae, goat-antelope that is mostly kept as livestock. It was domesticated from the wild goat (''C. aegagrus'') of Southwest Asia and Eastern Europe. The goat is a member of the ...

s, monkey

Monkey is a common name that may refer to most mammals of the infraorder Simiiformes, also known as simians. Traditionally, all animals in the group now known as simians are counted as monkeys except the apes. Thus monkeys, in that sense, co ...

s, and human beings to various gas mixtures at different pressures. By 1963 they had collected enough data to test the first SEALAB habitat.

Tektite I and II

The Tektite underwater habitat was constructed byGeneral Electric

General Electric Company (GE) was an American Multinational corporation, multinational Conglomerate (company), conglomerate founded in 1892, incorporated in the New York (state), state of New York and headquartered in Boston.

Over the year ...

and was funded by NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

, the Office of Naval Research

The Office of Naval Research (ONR) is an organization within the United States Department of the Navy responsible for the science and technology programs of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps. Established by Congress in 1946, its mission is to plan ...

and the United States Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government responsible for the management and conservation ...

.

On 15 February 1969, four Department of the Interior scientists (Ed Clifton, Conrad Mahnken, Richard Waller and John VanDerwalker) descended to the ocean floor in Great Lameshur Bay

Great may refer to:

Descriptions or measurements

* Great, a relative measurement in physical space, see Size

* Greatness, being divine, majestic, superior, majestic, or transcendent

People

* List of people known as "the Great"

* Artel Great (bo ...

in the United States Virgin Islands

The United States Virgin Islands, officially the Virgin Islands of the United States, are a group of Caribbean islands and a territory of the United States. The islands are geographically part of the Virgin Islands archipelago and are located ...

to begin an ambitious diving project dubbed "Tektite I". By 18 March 1969, the four aquanauts had established a new world's record for saturated diving by a single team. On 15 April 1969, the aquanaut team returned to the surface after performing 58 days of marine scientific studies. More than 19 hours of decompression were needed to safely return the team to the surface.

Inspired in part by NASA's budding Skylab

Skylab was the United States' first space station, launched by NASA, occupied for about 24 weeks between May 1973 and February 1974. It was operated by three trios of astronaut crews: Skylab 2, Skylab 3, and Skylab 4. Skylab was constructe ...

program and an interest in better understanding the effectiveness of scientists working under extremely isolated living conditions, Tektite was the first saturation diving project to employ scientists rather than professional divers.

The term tektite

Tektites () are gravel-sized bodies composed of black, green, brown or grey natural glass formed from terrestrial debris ejected during meteorite impacts. The term was coined by Austrian geologist Franz Eduard Suess (1867–1941), son of Eduar ...

generally refers to a class of meteorites formed by extremely rapid cooling. These include objects of celestial origins that strike the sea surface and come to rest on the bottom (note project Tektite's conceptual origins within the U.S space program).

The Tektite II missions were carried out in 1970. Tektite II comprised ten missions lasting 10 to 20 days with four scientists and an engineer on each mission. One of these missions included the first all-female aquanaut team, led by Dr. Sylvia Earle

Sylvia Alice Earle (born August 30, 1935) is an American marine biologist, oceanographer, explorer, author, and lecturer. She has been a National Geographic Explorer at Large (formerly Explorer in Residence) since 1998. Earle was the first fem ...

. Other scientists participating in the all-female mission included Dr. Renate True of Tulane University

The Tulane University of Louisiana (commonly referred to as Tulane University) is a private research university in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States. Founded as the Medical College of Louisiana in 1834 by a cohort of medical doctors, it b ...

, as well as Ann Hartline and Alina Szmant, graduate students at Scripps Institute of Oceanography. The fifth member of the crew was Margaret Ann Lucas, a Villanova University

Villanova University is a Private university, private Catholic Church, Catholic research university in Villanova, Pennsylvania, United States. It was founded by the Order of Saint Augustine in 1842 and named after Thomas of Villanova, Saint Thom ...

engineering graduate, who served as Habitat Engineer. The Tektite II missions were the first to undertake in-depth ecological studies.

Tektite II included 24 hour behavioral and mission observations of each of the missions by a team of observers from the University of Texas at Austin

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public university, public research university in Austin, Texas, United States. Founded in 1883, it is the flagship institution of the University of Texas System. With 53,082 stud ...

. Selected episodic events and discussions were videotaped using cameras in the public areas of the habitat. Data about the status, location and activities of each of the 5 members of each mission was collected via key punch data cards every six minutes during each mission. This information was collated and processed by BellComm and was used for the support of papers written about the research concerning the relative predictability of behavior patterns of mission participants in constrained, dangerous conditions for extended periods of time, such as those that might be encountered in crewed spaceflight. The Tektite habitat

The Tektite habitat was an underwater laboratory which was the home to divers during Tektite I and II programs. The Tektite program was the first scientists-in-the-sea program sponsored nationally. The habitat capsule was placed in Great Lamesh ...

was designed and built by General Electric Space Division at the Valley Forge Space Technology Center in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania

King of Prussia (nicknamed K.O.P.) is a census-designated place in Upper Merion Township, Pennsylvania, Upper Merion Township in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, United States. The community took its unusual name in the 18th century from a loca ...

. The Project Engineer who was responsible for the design of the habitat was Brooks Tenney, Jr. Tenney also served as the underwater Habitat Engineer on the International Mission, the last mission on the Tektite II project. The Program Manager for the Tektite projects at General Electric was Dr. Theodore Marton.

Hydrolab

Hydrolab was constructed in 1966 at a cost of $60,000 ($560,000 in today's currency) and used as a research station from 1970. The project was in part funded by theNational Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA ) is an American scientific and regulatory agency charged with Weather forecasting, forecasting weather, monitoring oceanic and atmospheric conditions, Hydrography, charting the seas, ...

(NOAA). Hydrolab could house four people. Approximately 180 Hydrolab missions were conducted—100 missions in The Bahamas

The Bahamas, officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic and island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean. It contains 97 per cent of the archipelago's land area and 88 per cent of ...

during the early to mid-1970s, and 80 missions off Saint Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands

Saint Croix ( ; ; ; ; Danish and ; ) is an island in the Caribbean Sea, and a county and constituent district of the United States Virgin Islands (USVI), an unincorporated territory of the United States.

St. Croix is the largest of the terr ...

, from 1977 to 1985. These scientific missions are chronicled in the ''Hydrolab Journal''.

Dr. William Fife

William Fife Jr. (15 June 1857 – 11 August 1944), also known as William Fife III, was the third generation of a family of Scottish yacht designers and builders. In his time, William Fife designed around 600 yachts, including two conten ...

spent 28 days in saturation, performing physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

experiments on researchers such as Dr. Sylvia Earle

Sylvia Alice Earle (born August 30, 1935) is an American marine biologist, oceanographer, explorer, author, and lecturer. She has been a National Geographic Explorer at Large (formerly Explorer in Residence) since 1998. Earle was the first fem ...

.

The habitat was decommissioned in 1985 and placed on display at the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

's National Museum of Natural History

The National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) is a natural history museum administered by the Smithsonian Institution, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. It has free admission and is open 364 days a year. With 4.4 ...

in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, the habitat is located at the NOAA Auditorium and Science Center at National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) headquarters in Silver Spring, Maryland.

Edalhab

The Engineering Design and Analysis Laboratory Habitat was a horizontal cylinder 2.6 m high, 3.3 m long and weighing 14 tonnes was built by students of the Engineering Design and Analysis Laboratory in the US at a cost of $20,000 or $187,000 in today's currency. From 26 April 1968, four students spent 48 hours and 6 minutes in this habitat in Alton Bay, New Hampshire. Two further missions followed to 12.2 m.

In the 1972 Edalhab II Florida Aquanaut Research Expedition experiments, the University of New Hampshire and NOAA used

The Engineering Design and Analysis Laboratory Habitat was a horizontal cylinder 2.6 m high, 3.3 m long and weighing 14 tonnes was built by students of the Engineering Design and Analysis Laboratory in the US at a cost of $20,000 or $187,000 in today's currency. From 26 April 1968, four students spent 48 hours and 6 minutes in this habitat in Alton Bay, New Hampshire. Two further missions followed to 12.2 m.

In the 1972 Edalhab II Florida Aquanaut Research Expedition experiments, the University of New Hampshire and NOAA used nitrox

Nitrox refers to any gas mixture composed (excepting trace gases) of nitrogen and oxygen. It is usually used for mixtures that contain less than 78% nitrogen by volume. In the usual application, underwater diving, nitrox is normally distinguished ...

as a breathing gas. In the three FLARE missions, the habitat was positioned off Miami at a depth of 13.7 m. The conversion to this experiment increased the weight of the habitat to 23 tonnes.

BAH I

BAH I (for Biological Institute Helgoland ) had a length of 6 m and a diameter of 2 m. It weighed about 20 tons and was intended for a crew of two people. The first mission in September 1968 with Jürgen Dorschel and Gerhard Lauckner at 10 m depth in the Baltic Sea lasted 11 days. In June 1969, a one-week flat-water mission took place in Lake Constance. In attempting to anchor the habitat at 47 m, the structure was flooded with the two divers in it and sank to the seabed. It was decided to lift it with the two divers according to the necessary decompression profile and nobody was harmed. BAH I provided valuable experience for the much larger underwater laboratory Helgoland. In 2003 it was taken over as a technical monument by the Technical University of Clausthal-Zellerfeld and in the same year went on display at the Nautineum Stralsund on Kleiner Dänholm island.Helgoland

The Helgoland underwater laboratory (UWL) is an underwater habitat. It was built inLübeck

Lübeck (; or ; Latin: ), officially the Hanseatic League, Hanseatic City of Lübeck (), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 220,000 inhabitants, it is the second-largest city on the German Baltic Sea, Baltic coast and the second-larg ...

, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

in 1968, and was the first of its kind in the world built for use in colder waters.

The 14 meter long, 7 meter diameter UWL allowed divers to spend several weeks under water using saturation diving

Saturation diving is an ambient pressure diving technique which allows a diver to remain at working depth for extended periods during which the body tissues become solubility, saturated with metabolically inert gas from the breathing gas mixture ...

techniques. The scientists and technicians would live and work in the laboratory, returning to it after every diving session. At the end of their stay they decompressed in the UWL, and could resurface without decompression sickness.

The UWL was used in the waters of the North and Baltic Seas and, in 1975, on Jeffreys Ledge, in the Gulf of Maine

The Gulf of Maine is a large gulf of the Atlantic Ocean on the east coast of North America. It is bounded by Cape Cod at the eastern tip of Massachusetts in the southwest and by Cape Sable Island at the southern tip of Nova Scotia in the northea ...

off the coast of New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

in the United States. At the end of the 1970s it was decommissioned and in 1998 donated to the German Oceanographic Museum

The German Oceanographic Museum (), also called the Museum for Oceanography and Fisheries, Aquarium (), in the Hanseatic town of Stralsund, is a museum in which maritime and oceanographic exhibitions are displayed. It is the most visited museu ...

where it can be visited at the Nautineum, a branch of the museum in Stralsund

Stralsund (; Swedish language, Swedish: ''Strålsund''), officially the Hanseatic League, Hanseatic City of Stralsund (German language, German: ''Hansestadt Stralsund''), is the fifth-largest city in the northeastern German federal state of Mecklen ...

.

Bentos-300

''Bentos-300'' (Bentos minus 300) was a maneuverable Soviet submersible with a diver lockout facility that could be stationed at the seabed. It was able to spend two weeks underwater at a maximum depth of 300m with about 25 people on board. Although announced in 1966, it had its first deployment in 1977. There were two vessels in the project. After Bentos-300 sank in the Russian Black Sea port of Novorossiisk in 1992, several attempts to recover it failed. In November 2011 it was cut up and recovered for scrap in the following six months.Progetto Abissi

The Italian ''Progetto Abissi'' habitat, also known as ''La Casa in Fondo al Mare'' (Italian for The House at the Bottom of the Sea), was designed by the diving team Explorer Team Pellicano, consisted of three cylindrical chambers and served as a platform for a television game show. It was deployed for the first time in September 2005 for ten days, and six aquanauts lived in the complex for 14 days in 2007.

The Italian ''Progetto Abissi'' habitat, also known as ''La Casa in Fondo al Mare'' (Italian for The House at the Bottom of the Sea), was designed by the diving team Explorer Team Pellicano, consisted of three cylindrical chambers and served as a platform for a television game show. It was deployed for the first time in September 2005 for ten days, and six aquanauts lived in the complex for 14 days in 2007.

MarineLab

The MarineLab underwater laboratory was the longest serving seafloor habitat in history, having operated continuously from 1984 to 2018 under the direction ofaquanaut

An aquanaut is any person who remains underwater, breathing at the ambient pressure for long enough for the concentration of the inert components of the breathing gas dissolved in the body tissues to reach equilibrium, in a state known as sat ...

Chris Olstad at Key Largo

Key Largo () is an island in the upper Florida Keys archipelago and is the largest section of the keys, at long. It is one of the northernmost of the Florida Keys in Monroe County, and the northernmost of the keys connected by U.S. Highway ...

, Florida. The seafloor laboratory has trained hundreds of individuals in that time, featuring an extensive array of educational and scientific investigations from United States military investigations to pharmaceutical development.

Beginning with a project initiated in 1973, MarineLab, then known as Midshipman Engineered & Designed Undersea Systems Apparatus (MEDUSA), was designed and built as part of an ocean engineering student program at the United States Naval Academy under the direction of Dr. Neil T. Monney. In 1983, MEDUSA was donated to the Marine Resources Development Foundation (MRDF), and in 1984 was deployed on the seafloor in John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park, Key Largo, Florida. The shore-supported habitat supports three or four persons and is divided into a laboratory, a wet-room, and a transparent observation sphere. From the beginning, it has been used by students for observation, research, and instruction. In 1985, it was renamed MarineLab and moved to the mangrove lagoon at MRDF headquarters in Key Largo at a depth of with a hatch depth of . The lagoon contains artifacts and wrecks placed there for education and training. From 1993 to 1995, NASA used MarineLab repeatedly to study Controlled Ecological Life Support Systems (CELLS). These education and research programs qualify MarineLab as the world's most extensively used habitat.

MarineLab was used as an integral part of the "Scott Carpenter, Man in the Sea" Program.

In 2018 the habitat was retired and restored to its 1985 condition and is on display to the public at Marine Resources Development Foundation, Inc. Key Largo, Florida.

Existing underwater habitats

Aquarius

The Aquarius Reef Base is an underwater habitat located 5.4 miles (9 kilometers) off

The Aquarius Reef Base is an underwater habitat located 5.4 miles (9 kilometers) off Key Largo

Key Largo () is an island in the upper Florida Keys archipelago and is the largest section of the keys, at long. It is one of the northernmost of the Florida Keys in Monroe County, and the northernmost of the keys connected by U.S. Highway ...

in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary

The Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary is a U.S. National Marine Sanctuary in the Florida Keys. It includes the Florida Reef, the only barrier coral reef in North America and the third-largest coral barrier reef in the world. It also has e ...

. It is deployed on the ocean floor below the surface and next to a deep coral reef named Conch Reef.

Aquarius is one of three undersea laboratories in the world dedicated to science and education. Two additional undersea facilities, also located in Key Largo, Florida

Key Largo is an unincorporated area and census-designated place in Monroe County, Florida, United States, located on the island of Key Largo in the upper Florida Keys. The population was 12,447 at the 2020 census, up from 10,433 in 2010. The ...

, are owned and operated by Marine Resources Development Foundation. Aquarius was owned by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA ) is an American scientific and regulatory agency charged with Weather forecasting, forecasting weather, monitoring oceanic and atmospheric conditions, Hydrography, charting the seas, ...

(NOAA) and operated by the University of North Carolina–Wilmington until 2013 when Florida International University

Florida International University (FIU) is a public research university with its main campus in Westchester, Florida, United States. Founded in 1965 by the Florida Legislature, the school opened to students in 1972. FIU is the third-largest univ ...

assumed operational control.

Florida International University (FIU) took ownership of Aquarius in October 2014. As part of the FIU Marine Education and Research Initiative, the Medina Aquarius Program is dedicated to the study and preservation of marine ecosystems worldwide and is enhancing the scope and impact of FIU on research, educational outreach, technology development, and professional training. At the heart of the program is the Aquarius Reef Base.

La Chalupa research laboratory

In the early 1970s, Ian Koblick, president of Marine Resources Development Foundation, developed and operated the La Chalupa research laboratory, which was the largest and most technologically advanced underwater habitat of its time. Koblick, who has continued his work as a pioneer in developing advanced undersea programs for ocean science and education, is the co-author of the book ''Living and Working in the Sea'' and is considered one of the foremost authorities on undersea habitation. La Chalupa was operated offPuerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

. During the habitat's launching for its second mission, a steel cable wrapped around Dr. Lance Rennka's left wrist, shattering his arm, which he subsequently lost to gas gangrene

Gas gangrene (also known as clostridial myonecrosis) is a bacterial infection that produces tissue gas in gangrene. This deadly form of gangrene usually is caused by '' Clostridium perfringens'' bacteria. About 1,000 cases of gas gangrene are r ...

.

In the mid-1980s La Chalupa was transformed into Jules' Undersea Lodge in Key Largo

Key Largo () is an island in the upper Florida Keys archipelago and is the largest section of the keys, at long. It is one of the northernmost of the Florida Keys in Monroe County, and the northernmost of the keys connected by U.S. Highway ...

, Florida. Jules' co-developer, Dr. Neil Monney, formerly served as Professor and Director of Ocean Engineering at the U.S. Naval Academy, and has extensive experience as a research scientist, aquanaut

An aquanaut is any person who remains underwater, breathing at the ambient pressure for long enough for the concentration of the inert components of the breathing gas dissolved in the body tissues to reach equilibrium, in a state known as sat ...

and designer of underwater habitats.

La Chalupa was used as the primary platform for the Scott Carpenter Man in the Sea Program, an underwater analog to Space Camp. Unlike Space Camp, which utilizes simulations, participants performed scientific tasks while using actual saturation diving systems. This program, envisioned by Ian Koblick and Scott Carpenter

Malcolm Scott Carpenter (May 1, 1925 – October 10, 2013) was an American naval officer and aviator, test pilot, aeronautical engineer, astronaut, and aquanaut. He was one of the Mercury Seven astronauts selected for NASA's Project Mercury ...

, was directed by Phillip Sharkey with operational help of Chris Olstad. Also used in the program was the MarineLab Underwater Habitat, the submersible

A submersible is an underwater vehicle which needs to be transported and supported by a larger ship, watercraft or dock, platform. This distinguishes submersibles from submarines, which are self-supporting and capable of prolonged independent ope ...

Sea Urchin (designed and built by Phil Nuytten

René Théophile "Phil" Nuytten (13 August 194113 May 2023) was a Canadian entrepreneur, deep-ocean explorer, scientist, inventor of the Newtsuit, and founder of Nuytco Research Ltd.

He pioneered designs related to diving equipment, and w ...

), and an Oceaneering Saturation Diving system consisting of an on-deck decompression chamber

A diving chamber is a vessel for human occupation, which may have an entrance that can be sealed to hold an internal pressure significantly higher than ambient pressure, a pressurised gas system to control the internal pressure, and a supply of ...

and a diving bell

A diving bell is a rigid chamber used to transport divers from the surface to depth and back in open water, usually for the purpose of performing underwater work. The most common types are the open-bottomed wet bell and the closed bell, which c ...

. La Chalupa was the site of the first underwater computer chat, a session hosted on GEnie

GEnie (General Electric Network for Information Exchange) was an online service provider, online service created by a General Electric business, GEIS (now GXS Inc., GXS), that ran from 1985 through the end of 1999. In 1994, GEnie claimed around ...

's Scuba RoundTable (the first non-computing related area on GEnie) by then-director Sharkey from inside the habitat. Divers from all over the world were able to direct questions to him and to Commander Carpenter.

Scott Carpenter Space Analog Station

James Cameron

James Francis Cameron (born August 16, 1954) is a Canadian filmmaker, who resides in New Zealand. He is a major figure in the post-New Hollywood era and often uses novel technologies with a Classical Hollywood cinema, classical filmmaking styl ...

. The SCSAS was designed by NASA engineer Dennis Chamberland.

Lloyd Godson's Biosub

Lloyd Godson's Biosub was an underwater habitat, built in 2007 for a competition by Australian Geographic. The Biosub generated its own electricity (using a bike); its own water, using the Air2Water Dragon Fly M18 system; and its own air, using algae that produce O2. The algae were fed using the Cascade High School Advanced Biology Class Biocoil. The habitat shelf itself was constructed by Trygons Designs.Galathée

The firstunderwater

An underwater environment is a environment of, and immersed in, liquid water in a natural or artificial feature (called a Water, body of water), such as an ocean, sea, lake, pond, reservoir, river, canal, or aquifer. Some characteristics of the ...

habitat built by Jacques Rougerie was launched and immersed on 4 August 1977. The unique feature of this semi-mobile habitat-laboratory

A laboratory (; ; colloquially lab) is a facility that provides controlled conditions in which scientific or technological research, experiments, and measurement may be performed. Laboratories are found in a variety of settings such as schools ...

is that it can be moored at any depth between 9 and 60 metres, which gives it the capability of phased integration in the marine environment. This habitat therefore has a limited impact on the marine ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) is a system formed by Organism, organisms in interaction with their Biophysical environment, environment. The Biotic material, biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and en ...

and is easy to position. Galathée was experienced by Jacques Rougerie himself.

Aquabulle

Launched for the first time in March 1978, thisunderwater

An underwater environment is a environment of, and immersed in, liquid water in a natural or artificial feature (called a Water, body of water), such as an ocean, sea, lake, pond, reservoir, river, canal, or aquifer. Some characteristics of the ...

shelter suspended in midwater (between 0 and 60 metres) is a mini scientific observatory 2.8 metres high by 2.5 metres in diameter.

The Aquabulle, created and experienced by Jacques Rougerie, can accommodate three people for a period of several hours and acts as an underwater refuge. A series of Aquabulles were later built and some are still being used by laboratories.

Hippocampe

This underwater habitat, created by a French architect, Jacques Rougerie, was launched in 1981 to act as a scientific base suspended in midwater using the same method as Galathée. Hippocampe can accommodate 2 people on saturation dives up to a depth of 12 metres for periods of 7 to 15 days, and was also designed to act as a subsea logistics base for the offshore industry.Ithaa undersea restaurant

Dhivehi

Dhivehi, also spelled Divehi, is the main language, used in the Maldive Islands. This may refer to:

*Dhivehi people, an ethnic group native to the historic region of the Maldive Islands

*Dhivehi language, an Indo-Aryan language predominantly spoke ...

for mother of pearl

Nacre ( , ), also known as mother-of-pearl, is an organicinorganic composite material produced by some molluscs as an inner shell layer. It is also the material of which pearls are composed. It is strong, resilient, and iridescent.

Nacre is ...

) is the world's only fully glazed underwater restaurant and is located in the Conrad Maldives Rangali Island hotel. It is accessible via a corridor from above the water and is open to the atmosphere, so there is no need for compression or decompression procedures. Ithaa was built by M.J. Murphy Ltd, and has an unballasted mass of 175 tonnes.

Red Sea Star

The "Red Sea Star" restaurant in Eilat, Israel, consisted of three modules: an entrance area above the water surface, a restaurant with 62 panorama windows 6 m under water and a ballast area below. The entire construction weighs about 6000 tons. The restaurant had a capacity of 105 people. It shut down in 2012.

The "Red Sea Star" restaurant in Eilat, Israel, consisted of three modules: an entrance area above the water surface, a restaurant with 62 panorama windows 6 m under water and a ballast area below. The entire construction weighs about 6000 tons. The restaurant had a capacity of 105 people. It shut down in 2012.

Eilat’s Coral World Underwater Observatory

The first part of

The first part of Eilat

Eilat ( , ; ; ) is Israel's southernmost city, with a population of , a busy port of Eilat, port and popular resort at the northern tip of the Red Sea, on what is known in Israel as the Gulf of Eilat and in Jordan as the Gulf of Aqaba. The c ...

's Coral World Underwater Observatory was built in 1975 and it was expanded in 1991 by adding a second underwater observatory connected by a tunnel. The underwater complex is accessible via a footbridge from the shore and a shaft from above the water surface. The observation area is at a depth of approximately 12 m.

Alpha Deep SeaPod

Alpha Deep SeaPod is located off the coast of

Alpha Deep SeaPod is located off the coast of Puerto Lindo

Puerto, a Spanish word meaning ''seaport'', may refer to:

Places

*El Puerto de Santa María, Andalusia, Spain

*Puerto, a seaport town in Cagayan de Oro, Philippines

*Puerto Colombia, Colombia

*Puerto Cumarebo, Venezuela

*Puerto Galera, Oriental Mi ...

in Portobelo

Portobelo (Modern Spanish: "Puerto Bello" ("beautiful port"), historically in Portuguese: Porto Belo) is a historic port and corregimiento in Portobelo District, Colón Province, Panama. Located on the northern part of the Isthmus of Panama, it ...

. The Pod was commissioned on the 5th of Feb, 2024. It is currently operational and serves as the residence of its owner. The floating residence provides living quarters with 360-degree panoramic views, while the underwater capsule serves as a 300-square-foot (about 28-square-meter) functional living space.

In popular culture

See also

* * * * * * * * * * *References

Sources

Gregory Stone: "Deep Science".

National Geographic Online Extra (Sept 2003). Retrieved 29 July 2007. *BBC.

Living under the sea

'

External links

*US Naval Undersea Museu{{Underwater diving, divsup Pressure vessels