Hun Stuff on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mustard gas or sulfur mustard are names commonly used for the

Mustard gases have powerful

Mustard gases have powerful

Sulfur mustards readily eliminate

Sulfur mustards readily eliminate

Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. Accessed June 8, 2010. Alternatively, if cell death is not immediate, the damaged DNA can lead to the development of cancer.

In its history, various types and mixtures of mustard gas have been employed. These include:

* H – Also known as HS ("Hun Stuff") or ''Levinstein mustard''. This is named after the inventor of the "quick but dirty" Levinstein Process for manufacture, reacting dry

In its history, various types and mixtures of mustard gas have been employed. These include:

* H – Also known as HS ("Hun Stuff") or ''Levinstein mustard''. This is named after the inventor of the "quick but dirty" Levinstein Process for manufacture, reacting dry

. Itech.dickinson.edu (2008-04-25). Retrieved on 2011-05-29. Despretz described the reaction of

Since World War I, mustard gas has been used in several wars and other conflicts, usually against people who cannot retaliate in kind:Blister Agent: Mustard gas (H, HD, HS)

Since World War I, mustard gas has been used in several wars and other conflicts, usually against people who cannot retaliate in kind:Blister Agent: Mustard gas (H, HD, HS)

, CBWinfo.com * United Kingdom against the

Mustardgas.org. Retrieved on 29 May 2011. In 2009, a mining survey near

From 1943 to 1944, mustard agent experiments were performed on Australian service volunteers in tropical

From 1943 to 1944, mustard agent experiments were performed on Australian service volunteers in tropical  African American servicemen were tested alongside white men in separate trials to determine whether their skin color would afford them a degree of immunity to the agents, and

African American servicemen were tested alongside white men in separate trials to determine whether their skin color would afford them a degree of immunity to the agents, and

online

* Duchovic, Ronald J., and Joel A. Vilensky. "Mustard gas: its pre-World War I history." ''Journal of chemical education'' 84.6 (2007): 944

online

* Feister, Alan J. ''Medical defense against mustard gas: toxic mechanisms and pharmacological implications'' (1991)

online

* Fitzgerald, Gerard J. "Chemical warfare and medical response during World War I." ''American journal of public health'' 98.4 (2008): 611-625

online

** * Geraci, Matthew J. "Mustard gas: imminent danger or eminent threat?." ''Annals of Pharmacotherapy'' 42.2 (2008): 237-246

online

* Ghabili, Kamyar, et al. "Mustard gas toxicity: the acute and chronic pathological effects." ''Journal of applied toxicology'' 30.7 (2010): 627-643

online

* Jones, Edgar. "Terror weapons: The British experience of gas and its treatment in the First World War." ''War in History'' 21.3 (2014): 355-375

online

* * Padley, Anthony Paul. "Gas: the greatest terror of the Great War." ''Anaesthesia and intensive care'' 44.1_suppl (2016): 24-30

online

* Rall, David P., and Constance M. Pechura, eds. ''Veterans at risk: The health effects of mustard gas and lewisite'' (1993)

online

* * Schummer, Joachim. "Ethics of chemical weapons research: Poison gas in World War One." ''Ethics of Chemistry: From Poison Gas to Climate Engineering'' (2021) pp. 55-83

online

* Smith, Susan I. ''Toxic Exposures: Mustard Gas and the Health Consequences of World War II in the United States'' (Rutgers University Press, 2017

online book review

* Wattana, Monica, and Tareg Bey. "Mustard gas or sulfur mustard: an old chemical agent as a new terrorist threat." ''Prehospital and disaster medicine'' 24.1 (2009): 19-29

online

Inchem.org (1998-02-09). Retrieved on 2011-05-29. *

Textbook of Military Medicine – Intensive overview of mustard gas

Includes many references to scientific literature

* Shows photographs taken in 1996 showing people with mustard gas burns.

UMDNJ-Rutgers University CounterACT Research Center of Excellence

A research center studying mustard gas, include

searchable reference library

with many early references on mustard gas. *

surgical treatment of mustard gas burns

UK Ministry of Defence Report on disposal of weapons at sea and incidents arising

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mustard gas Thioethers Blister agents World War I chemical weapons IARC Group 1 carcinogens Chloroethyl compounds Sulfur mustards Dermatoxins

organosulfur

Organosulfur chemistry is the study of the properties and synthesis of organosulfur compounds, which are organic compounds that contain sulfur. They are often associated with foul odors, but many of the sweetest compounds known are organosulfur der ...

chemical compound

A chemical compound is a chemical substance composed of many identical molecules (or molecular entities) containing atoms from more than one chemical element held together by chemical bonds. A molecule consisting of atoms of only one element ...

bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide

Bis(2-chloroethyl)sulfide is the organosulfur compound with the formula . It is a prominent member of a family of cytotoxicity, cytotoxic and blister agents known as mustard agents. Sometimes referred to as ''mustard gas'', the term is technicall ...

, which has the chemical structure S(CH2CH2Cl)2, as well as other species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

. In the wider sense, compounds with the substituents are known as ''sulfur mustards'' or ''nitrogen mustards

Nitrogen mustards (NMs) are cytotoxic organic compounds with the bis(2-chloroethyl)amino ((ClC2H4)2NR) functional group. Although originally produced as chemical warfare agents, they were the first chemotherapeutic agents for treatment of cance ...

'', respectively, where X = Cl or Br. Such compounds are potent alkylating agent Alkylation is a chemical reaction that entails transfer of an alkyl group. The alkyl group may be transferred as an alkyl carbocation, a free radical, a carbanion, or a carbene (or their equivalents). Alkylating agents are reagents for effecting ...

s, making mustard gas acutely and severely toxic. Mustard gas is a carcinogen

A carcinogen () is any agent that promotes the development of cancer. Carcinogens can include synthetic chemicals, naturally occurring substances, physical agents such as ionizing and non-ionizing radiation, and biologic agents such as viruse ...

. There is no preventative agent against mustard gas, with protection depending entirely on skin and airways protection, and no antidote

An antidote is a substance that can counteract a form of poisoning. The term ultimately derives from the Greek term φάρμακον ἀντίδοτον ''(pharmakon antidoton)'', "(medicine) given as a remedy". An older term in English which is ...

exists for mustard poisoning.

Also known as mustard agents, this family of compounds comprises infamous cytotoxins

Cytotoxicity is the quality of being toxic to cells. Examples of toxic agents are toxic metals, toxic chemicals, microbe neurotoxins, radiation particles and even specific neurotransmitters when the system is out of balance. Also some types of dru ...

and blister agent

A blister agent (or vesicant) is a chemical compound that causes severe skin, eye and mucosal pain and irritation in the form of severe chemical burns resulting in fluid filled blisters. Named for their ability to cause vesication, blister a ...

s with a long history of use as chemical weapons

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as ...

. The name ''mustard gas'' is technically incorrect; the substances, when dispersed, are often not gases but a fine mist of liquid droplets that can be readily absorbed through the skin and by inhalation. The skin can be affected by contact with either the liquid or vapor. The rate of penetration into skin is proportional to dose, temperature and humidity.

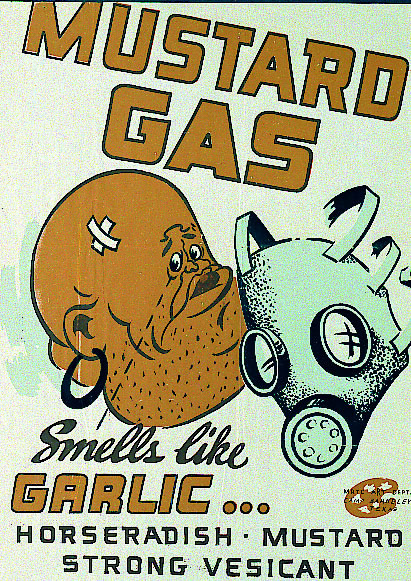

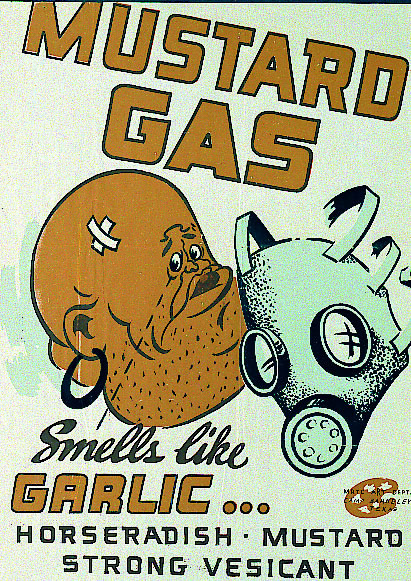

Sulfur mustards are viscous liquids at room temperature and have an odor resembling mustard plant

The mustard plant is any one of several plant species in the genera ''Brassica'', ''Rhamphospermum'' and ''Sinapis'' in the family Brassicaceae (the mustard family). Mustard seed is used as a spice. Grinding and mixing the seeds with water, vin ...

s, garlic

Garlic (''Allium sativum'') is a species of bulbous flowering plants in the genus '' Allium''. Its close relatives include the onion, shallot, leek, chives, Welsh onion, and Chinese onion. Garlic is native to central and south Asia, str ...

, or horseradish

Horseradish (''Armoracia rusticana'', syn. ''Cochlearia armoracia'') is a perennial plant of the family Brassicaceae (which also includes Mustard plant, mustard, wasabi, broccoli, cabbage, and radish). It is a root vegetable, cultivated and us ...

, hence the name. When pure, they are colorless, but when used in impure forms, such as in warfare, they are usually yellow-brown. Mustard gases form blister

A blister is a small pocket of body fluid (lymph, serum, plasma, blood, or pus) within the upper layers of the skin, usually caused by forceful rubbing (friction), burning, freezing, chemical exposure or infection. Most blisters are filled ...

s on exposed skin and in the lungs, often resulting in prolonged illness ending in death.

History as chemical weapons

Sulfur mustard is a type of chemical warfare agent. As a chemical weapon, mustard gas was first used inWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, and has been used in several armed conflicts since then, including the Iran–Iraq War

The Iran–Iraq War, also known as the First Gulf War, was an armed conflict between Iran and Iraq that lasted from September 1980 to August 1988. Active hostilities began with the Iraqi invasion of Iran and lasted for nearly eight years, unti ...

, resulting in more than 100,000 casualties. Sulfur-based and nitrogen-based mustard agents are regulated under Schedule 1 of the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention

The Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), officially the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction, is an arms control treaty administered by the Organisation for ...

, as substances with few uses other than in chemical warfare. Mustard agents can be deployed by means of artillery shell

A shell, in a modern military context, is a projectile whose payload contains an explosive, incendiary device, incendiary, or other chemical filling. Originally it was called a bombshell, but "shell" has come to be unambiguous in a military ...

s, aerial bomb

An aerial bomb is a type of Explosive weapon, explosive or Incendiary device, incendiary weapon intended to travel through the Atmosphere of Earth, air on a predictable trajectory. Engineers usually develop such bombs to be dropped from an aircra ...

s, rocket

A rocket (from , and so named for its shape) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using any surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely ...

s, or by spraying from aircraft.

Adverse health effects

Mustard gases have powerful

Mustard gases have powerful blistering

A blister is a small pocket of fluid in the upper layer of the skin caused by heat, electricity, chemicals, light, radiation, or friction

Blister(s) or Blistering may also refer to:

* Blood blister

* Bleb (medicine)

* Anti-torpedo bulge, also know ...

effects on victims. They are also carcinogen

A carcinogen () is any agent that promotes the development of cancer. Carcinogens can include synthetic chemicals, naturally occurring substances, physical agents such as ionizing and non-ionizing radiation, and biologic agents such as viruse ...

ic and mutagen

In genetics, a mutagen is a physical or chemical agent that permanently changes genetic material, usually DNA, in an organism and thus increases the frequency of mutations above the natural background level. As many mutations can cause cancer in ...

ic alkylating agents Alkylation is a chemical reaction that entails transfer of an alkyl group. The alkyl group may be transferred as an alkyl carbocation, a free radical, a carbanion, or a carbene (or their equivalents). Alkylating agents are reagents for effectin ...

. Their high lipophilic

Lipophilicity (from Greek language, Greek λίπος "fat" and :wikt:φίλος, φίλος "friendly") is the ability of a chemical compound to dissolve in fats, oils, lipids, and non-polar solvents such as hexane or toluene. Such compounds are c ...

ity accelerates their absorption into the body. Because mustard agents often do not elicit immediate symptoms, contaminated areas may appear normal. Within 24 hours of exposure, victims experience intense itch

An itch (also known as pruritus) is a sensation that causes a strong desire or reflex to scratch. Itches have resisted many attempts to be classified as any one type of sensory experience. Itches have many similarities to pain, and while both ...

ing and skin irritation. If this irritation goes untreated, blisters filled with pus

Pus is an exudate, typically white-yellow, yellow, or yellow-brown, formed at the site of inflammation during infections, regardless of cause. An accumulation of pus in an enclosed tissue space is known as an abscess, whereas a visible collect ...

can form wherever the agent contacted the skin. As chemical burn

A chemical burn occurs when living tissue is exposed to a corrosive substance (such as a strong acid, base or oxidizer) or a cytotoxic agent (such as mustard gas, lewisite or arsine). Chemical burns follow standard burn classification and m ...

s, these are severely debilitating. Mustard gas can have the effect of turning a patient's skin different colors due to melanogenesis.

If the victim's eyes were exposed, then they become sore, starting with conjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis, also known as pink eye or Madras eye, is inflammation of the conjunctiva, the thin, clear layer that covers the white surface of the eye and the inner eyelid. It makes the eye appear pink or reddish. Pain, burning, scratchiness ...

(also known as pink eye), after which the eyelids swell, resulting in temporary blindness. Extreme ocular exposure to mustard gas vapors may result in corneal ulcer

Corneal ulcer, often resulting from keratitis is an inflammatory or, more seriously, infective condition of the cornea involving disruption of its epithelial layer with involvement of the corneal stroma. It is a common condition in humans part ...

ation, anterior chamber scarring, and neovascularization

Neovascularization is the natural formation of new blood vessels ('' neo-'' + ''vascular'' + '' -ization''), usually in the form of functional microvascular networks, capable of perfusion by red blood cells, that form to serve as collateral circu ...

. In these severe and infrequent cases, corneal transplantation

Corneal transplantation, also known as corneal grafting, is a surgical procedure where a damaged or diseased cornea is replaced by donated corneal tissue (the graft). When the entire cornea is replaced it is known as penetrating keratoplasty a ...

has been used as a treatment. Miosis

Miosis, or myosis (), is excessive constriction of the pupil.Farlex medical dictionary

citing: ...

, when the pupil constricts more than usual, may also occur, which may be the result of the cholinomimetic activity of mustard. If inhaled in high concentrations, mustard agents cause bleeding and blistering within the citing: ...

respiratory system

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies grea ...

, damaging mucous membrane

A mucous membrane or mucosa is a membrane that lines various cavities in the body of an organism and covers the surface of internal organs. It consists of one or more layers of epithelial cells overlying a layer of loose connective tissue. It ...

s and causing pulmonary edema

Pulmonary edema (British English: oedema), also known as pulmonary congestion, is excessive fluid accumulation in the tissue or air spaces (usually alveoli) of the lungs. This leads to impaired gas exchange, most often leading to shortness ...

. Depending on the level of contamination, mustard agent burns can vary between first

First most commonly refers to:

* First, the ordinal form of the number 1

First or 1st may also refer to:

Acronyms

* Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty-Centimeters, an astronomical survey carried out by the Very Large Array

* Far Infrared a ...

and second degree burn

A burn is an injury to skin, or other tissues, caused by heat, electricity, chemicals, friction, or ionizing radiation (such as sunburn, caused by ultraviolet radiation). Most burns are due to heat from hot fluids (called scalding), solids, ...

s. They can also be as severe, disfiguring, and dangerous as third degree burn

A burn is an injury to skin, or other tissues, caused by heat, electricity, chemicals, friction, or ionizing radiation (such as sunburn, caused by ultraviolet radiation). Most burns are due to heat from hot fluids (called scalding), solids, ...

s. Some 80% of sulfur mustard in contact with the skin evaporates, while 10% stays in the skin and 10% is absorbed and circulated in the blood.

The carcinogenic and mutagenic effects of exposure to mustard gas increase the risk of developing cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving Cell growth#Disorders, abnormal cell growth with the potential to Invasion (cancer), invade or Metastasis, spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Po ...

later in life. In a study of patients 25 years after wartime exposure to chemical weaponry, c-DNA microarray profiling indicated that 122 genes were significantly mutated in the lungs and airways of mustard gas victims. Those genes all correspond to functions commonly affected by mustard gas exposure, including apoptosis

Apoptosis (from ) is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms and in some eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms such as yeast. Biochemistry, Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (Morphology (biol ...

, inflammation, and stress responses. The long-term ocular complications include burning, tearing, itching, photophobia

Photophobia is a medical symptom of abnormal intolerance to visual perception of light. As a medical symptom, photophobia is not a morbid fear or phobia, but an experience of discomfort or pain to the eyes due to light exposure or by presence o ...

, presbyopia

Presbyopia is a physiological insufficiency of optical Accommodation (vertebrate eye), accommodation associated with the aging of the human eye, eye; it results in progressively worsening ability to focus clearly on close objects. Also known as ...

, pain, and foreign-body sensations.

Medical management

In a rinse-wipe-rinse sequence, skin is decontaminated of mustard gas by washing with liquid soap and water, or an absorbent powder. The eyes should be thoroughly rinsed using saline or clean water. A topical analgesic is used to relieve skin pain during decontamination. For skin lesions, topical treatments, such ascalamine lotion

Calamine, also known as calamine lotion, is a medication made from powdered calamine mineral that is used to treat mild itchiness. Conditions treated include sunburn, insect bites, poison ivy, poison oak, and other mild skin conditions. It m ...

, steroids, and oral antihistamine

Antihistamines are drugs which treat allergic rhinitis, common cold, influenza, and other allergies. Typically, people take antihistamines as an inexpensive, generic (not patented) drug that can be bought without a prescription and provides ...

s are used to relieve itching. Larger blisters are irrigated repeatedly with saline or soapy water, then treated with an antibiotic and petroleum gauze.

Mustard agent burns do not heal quickly and (as with other types of burns) present a risk of sepsis

Sepsis is a potentially life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs.

This initial stage of sepsis is followed by suppression of the immune system. Common signs and s ...

caused by pathogen

In biology, a pathogen (, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of"), in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a Germ theory of d ...

s such as ''Staphylococcus aureus

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a Gram-positive spherically shaped bacterium, a member of the Bacillota, and is a usual member of the microbiota of the body, frequently found in the upper respiratory tract and on the skin. It is often posi ...

'' and ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa

''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'' is a common Bacterial capsule, encapsulated, Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-negative, Aerobic organism, aerobic–facultative anaerobe, facultatively anaerobic, Bacillus (shape), rod-shaped bacteria, bacterium that can c ...

''. The mechanisms behind mustard gas's effect on endothelial cells are still being studied, but recent studies have shown that high levels of exposure can induce high rates of both necrosis

Necrosis () is a form of cell injury which results in the premature death of cells in living tissue by autolysis. The term "necrosis" came about in the mid-19th century and is commonly attributed to German pathologist Rudolf Virchow, who i ...

and apoptosis

Apoptosis (from ) is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms and in some eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms such as yeast. Biochemistry, Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (Morphology (biol ...

. In vitro tests have shown that at low concentrations of mustard gas, where apoptosis is the predominant result of exposure, pretreatment with 50 mM N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) was able to decrease the rate of apoptosis. NAC protects actin

Actin is a family of globular multi-functional proteins that form microfilaments in the cytoskeleton, and the thin filaments in muscle fibrils. It is found in essentially all eukaryotic cells, where it may be present at a concentration of ...

filaments from reorganization by mustard gas, demonstrating that actin filaments play a large role in the severe burns observed in victims.

A British nurse treating soldiers with mustard agent burns during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

commented:

Mechanism of cellular toxicity

chloride

The term chloride refers to a compound or molecule that contains either a chlorine anion (), which is a negatively charged chlorine atom, or a non-charged chlorine atom covalently bonded to the rest of the molecule by a single bond (). The pr ...

ions by intramolecular nucleophilic substitution

In chemistry, a nucleophilic substitution (SN) is a class of chemical reactions in which an electron-rich chemical species (known as a nucleophile) replaces a functional group within another electron-deficient molecule (known as the electrophile) ...

to form cyclic sulfonium

In organic chemistry, a sulfonium ion, also known as sulphonium ion or sulfanium ion, is a positively-charged ion (a "cation") featuring three organic Substitution (chemistry), substituents attached to sulfur. These organosulfur compounds have t ...

ions. These very reactive intermediates tend to permanently alkylate

An alkylation unit (alky) is one of the conversion processes used in petroleum refineries. It is used to convert isobutane and low-molecular-weight alkenes (primarily a mixture of propene and butene) into alkylate, a high octane gasoline componen ...

nucleotide

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

s in DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

strands, which can prevent cellular division, leading to programmed cell death

Programmed cell death (PCD) sometimes referred to as cell, or cellular suicide is the death of a cell (biology), cell as a result of events inside of a cell, such as apoptosis or autophagy. PCD is carried out in a biological process, which usual ...

.Mustard agents: description, physical and chemical properties, mechanism of action, symptoms, antidotes and methods of treatmentOrganisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. Accessed June 8, 2010. Alternatively, if cell death is not immediate, the damaged DNA can lead to the development of cancer.

Oxidative stress

Oxidative stress reflects an imbalance between the systemic manifestation of reactive oxygen species and a biological system's ability to readily detoxify the reactive intermediates or to repair the resulting damage. Disturbances in the normal ...

is another pathology involved in mustard gas toxicity.

Various compounds with the structural subgroup BC2H4X, where X is any leaving group

In organic chemistry, a leaving group typically means a Chemical species, molecular fragment that departs with an electron, electron pair during a reaction step with heterolysis (chemistry), heterolytic bond cleavage. In this usage, a ''leaving gr ...

and B is a Lewis base

A Lewis acid (named for the American physical chemist Gilbert N. Lewis) is a chemical species that contains an empty orbital which is capable of accepting an electron pair from a Lewis base to form a Lewis adduct. A Lewis base, then, is any sp ...

, have a common name of mustard. Such compounds can form cyclic "onium" ions (sulfonium, ammonium

Ammonium is a modified form of ammonia that has an extra hydrogen atom. It is a positively charged (cationic) polyatomic ion, molecular ion with the chemical formula or . It is formed by the protonation, addition of a proton (a hydrogen nucleu ...

, etc.) that are good alkylating agent Alkylation is a chemical reaction that entails transfer of an alkyl group. The alkyl group may be transferred as an alkyl carbocation, a free radical, a carbanion, or a carbene (or their equivalents). Alkylating agents are reagents for effecting ...

s. These compoudsn include bis(2-haloethyl)ethers ( oxygen mustards), the (2-haloethyl)amines (nitrogen mustard

Nitrogen mustards (NMs) are cytotoxic organic compounds with the bis(2-chloroethyl)amino ((ClC2H4)2NR) functional group. Although originally produced as chemical warfare agents, they were the first chemotherapeutic agents for treatment of canc ...

s), and sesquimustard, which has two α-chloroethyl thioether groups (ClC2H4S−) connected by an ethylene bridge (−C2H4−). These compounds have a similar ability to alkylate DNA, but their physical properties vary.

Formulations

In its history, various types and mixtures of mustard gas have been employed. These include:

* H – Also known as HS ("Hun Stuff") or ''Levinstein mustard''. This is named after the inventor of the "quick but dirty" Levinstein Process for manufacture, reacting dry

In its history, various types and mixtures of mustard gas have been employed. These include:

* H – Also known as HS ("Hun Stuff") or ''Levinstein mustard''. This is named after the inventor of the "quick but dirty" Levinstein Process for manufacture, reacting dry ethylene

Ethylene (IUPAC name: ethene) is a hydrocarbon which has the formula or . It is a colourless, flammable gas with a faint "sweet and musky" odour when pure. It is the simplest alkene (a hydrocarbon with carbon–carbon bond, carbon–carbon doub ...

with disulfur dichloride

Disulfur dichloride (or disulphur dichloride by the British English spelling) is the inorganic compound of sulfur and chlorine with the Chemical formula, formula . It is an amber oily liquid.

Sometimes, this compound is incorrectly named ''sulfur ...

under controlled conditions. Undistilled mustard gas contains 20–30% impurities, which means it does not store as well as HD. Also, as it decomposes, it increases in vapor pressure

Vapor pressure or equilibrium vapor pressure is the pressure exerted by a vapor in thermodynamic equilibrium with its condensed phases (solid or liquid) at a given temperature in a closed system. The equilibrium vapor pressure is an indicat ...

, making the munition it is contained in likely to split, especially along a seam, releasing the agent to the atmosphere.FM 3–8 Chemical Reference handbook, US Army, 1967

* HD – Codenamed Pyro by the British, and Distilled Mustard by the US. Distilled

Distillation, also classical distillation, is the process of separating the component substances of a liquid mixture of two or more chemically discrete substances; the separation process is realized by way of the selective boiling of the mixt ...

mustard of 95% or higher purity. The term "mustard gas" usually refers to this variety of mustard.

* HT – Codenamed Runcol by the British, and Mustard T- mixture by the US. A mixture of 60% HD mustard and 40% O-mustard, a related vesicant with lower freezing point

The melting point (or, rarely, liquefaction point) of a substance is the temperature at which it changes state of matter, state from solid to liquid. At the melting point the solid and liquid phase (matter), phase exist in Thermodynamic equilib ...

, lower volatility and similar vesicant characteristics.

* HL – A blend of distilled mustard (HD) and lewisite

Lewisite (L) (A-243) is an organoarsenic compound. It was once manufactured in the United States, Japan, Germany and the Soviet Union for use as a Chemical warfare, chemical weapon, acting as a vesicant (blister agent) and lung irritant. Although ...

(L), originally intended for use in winter conditions due to its lower freezing point compared to the pure substances. The lewisite component of HL was used as a form of antifreeze

An antifreeze is an additive which lowers the freezing point of a water-based liquid. An antifreeze mixture is used to achieve freezing-point depression for cold environments. Common antifreezes also increase the boiling point of the liquid, allow ...

.

* HQ – A blend of distilled mustard (HD) and sesquimustard (Q) (Gates and Moore 1946).

* Yellow Cross – any of several blends containing sulfur mustard. Named for the yellow cross painted on artillery shells.

Commonly-stockpiled mustard agents (class)

History

Development

Mustard gases were possibly developed as early as 1822 byCésar-Mansuète Despretz César-Mansuète Despretz (4 May 1791, Lessines – 15 March 1863, Paris) was a chemist and physicist. He became a French citizen in 1838. A street got its name after him in Lessines (rue César Despretz).

Biography

In 1818, Despretz started ...

(1798–1863).By Any Other Name: Origins of Mustard Gas. Itech.dickinson.edu (2008-04-25). Retrieved on 2011-05-29. Despretz described the reaction of

sulfur dichloride

Sulfur dichloride is the chemical compound with the formula . This cherry-red liquid is the simplest sulfur chloride and one of the most common, and it is used as a precursor to organosulfur compounds. It is a highly corrosive and toxic substance ...

and ethylene

Ethylene (IUPAC name: ethene) is a hydrocarbon which has the formula or . It is a colourless, flammable gas with a faint "sweet and musky" odour when pure. It is the simplest alkene (a hydrocarbon with carbon–carbon bond, carbon–carbon doub ...

but never made mention of any irritating properties of the reaction product. In 1854, another French chemist, Alfred Riche (1829–1908), repeated this procedure, also without describing any adverse physiological properties. In 1860, the British scientist Frederick Guthrie Frederick Guthrie may refer to:

*Frederick Guthrie (scientist) (1833–1886), British physicist, chemist, and academic

* Frederick Guthrie (bass) (1924–2008), American operatic bass

*Frederick Bickell Guthrie

Frederick Bickell Guthrie (10 Decem ...

synthesized and characterized the mustard agent compound and noted its irritating properties, especially in tasting. Also in 1860, chemist Albert Niemann, known as a pioneer in cocaine

Cocaine is a tropane alkaloid and central nervous system stimulant, derived primarily from the leaves of two South American coca plants, ''Erythroxylum coca'' and ''Erythroxylum novogranatense, E. novogranatense'', which are cultivated a ...

chemistry, repeated the reaction, and recorded blister-forming properties. In 1886, Viktor Meyer

Viktor Meyer (8 September 18488 August 1897) was a German chemist and significant contributor to both organic and inorganic chemistry. He is best known for inventing an apparatus for determining vapour densities, the Viktor Meyer apparatus, and ...

published a paper describing a synthesis that produced good yields. He combined 2-chloroethanol

2-Chloroethanol (also called ethylene chlorohydrin or glycol chlorohydrin) is an organic chemical compound with the chemical formula HOCH2CH2Cl and the ''simplest'' beta-halohydrin (chlorohydrin). This colorless liquid has a pleasant ether-like od ...

with aqueous

An aqueous solution is a solution in which the solvent is water. It is mostly shown in chemical equations by appending (aq) to the relevant chemical formula. For example, a solution of table salt, also known as sodium chloride (NaCl), in wat ...

potassium sulfide

Potassium sulfide is an inorganic compound with the formula K2 S. The colourless solid is rarely encountered, because it reacts readily with water, a reaction that affords potassium hydrosulfide (KSH) and potassium hydroxide (KOH). Most commonl ...

, and then treated the resulting thiodiglycol

Thiodiglycol, or bis(2-hydroxyethyl)sulfide (also known as 2,2-thiodiethanol or TDE), is the organosulfur compound with the formula S(CH2CH2OH)2. It is miscible with water and polar organic solvents. It is a colorless liquid. It is structurally ...

with phosphorus trichloride

Phosphorus trichloride is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula PCl3. A colorless liquid when pure, it is an important industrial chemical, being used for the manufacture of phosphites and other organophosphorus compounds. It is toxic ...

. The purity of this compound was much higher and consequently the adverse health effects upon exposure were much more severe. These symptoms presented themselves in his assistant, and in order to rule out the possibility that his assistant was suffering from a mental illness (psychosomatic symptoms), Meyer had this compound tested on laboratory rabbit

Rabbits are small mammals in the family Leporidae (which also includes the hares), which is in the order Lagomorpha (which also includes pikas). They are familiar throughout the world as a small herbivore, a prey animal, a domesticated ...

s, most of which died. In 1913, the English chemist Hans Thacher Clarke

Hans Thacher Clarke (27 December 1887 – 21 October 1972) was a prominent biochemist during the first half of the twentieth century. He was born in England where he received his university training, but also studied in Germany and Ireland. He sp ...

(known for the Eschweiler-Clarke reaction) replaced the phosphorus trichloride with hydrochloric acid

Hydrochloric acid, also known as muriatic acid or spirits of salt, is an aqueous solution of hydrogen chloride (HCl). It is a colorless solution with a distinctive pungency, pungent smell. It is classified as a acid strength, strong acid. It is ...

in Meyer's formulation while working with Emil Fischer

Hermann Emil Louis Fischer (; 9 October 1852 – 15 July 1919) was a German chemist and List of Nobel laureates in Chemistry, 1902 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He discovered the Fischer esterification. He also developed the Fisch ...

in Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

. Clarke was hospitalized for two months for burns after one of his flasks broke. According to Meyer, Fischer's report on this accident to the German Chemical Society

The German Chemical Society () is a learned society and professional association founded in 1949 to represent the interests of German chemists in local, national and international contexts. GDCh "brings together people working in chemistry and th ...

sent the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

on the road to chemical weapons.

The German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

relied on the Meyer-Clarke method because 2-chloroethanol

2-Chloroethanol (also called ethylene chlorohydrin or glycol chlorohydrin) is an organic chemical compound with the chemical formula HOCH2CH2Cl and the ''simplest'' beta-halohydrin (chlorohydrin). This colorless liquid has a pleasant ether-like od ...

was readily available from the German dye industry of that time.

Use

Mustard gas was first used in World War I by the German army against British and Canadian soldiers nearYpres

Ypres ( ; ; ; ; ) is a Belgian city and municipality in the province of West Flanders. Though

the Dutch name is the official one, the city's French name is most commonly used in English. The municipality comprises the city of Ypres/Ieper ...

, Belgium, on July 12, 1917, and later also against the French Second Army. ''Yperite'' is "a name used by the French, because the compound was first used at Ypres." The Allies used mustard gas for the first time on November 1917 at Cambrai

Cambrai (, ; ; ), formerly Cambray and historically in English Camerick or Camericke, is a city in the Nord department and in the Hauts-de-France region of France on the Scheldt river, which is known locally as the Escaut river.

A sub-pref ...

, France, after the armies had captured a stockpile of German mustard shells. It took the British more than a year to develop their own mustard agent weapon, with production of the chemicals centred on Avonmouth Docks

The Avonmouth Docks are part of the Port of Bristol, in England. They are situated on the northern side of the mouth of the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, opposite the Royal Portbury Dock on the southern side, where the river joins the River S ...

(the only option available to the British was the Despretz–Niemann–Guthrie process).

Mustard gas was originally assigned the name LOST, after the scientists Wilhelm Lommel and Wilhelm Steinkopf, who developed a method of large-scale production for the Imperial German Army

The Imperial German Army (1871–1919), officially referred to as the German Army (), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the leadership of Kingdom o ...

in 1916.

Mustard gas was dispersed as an aerosol

An aerosol is a suspension (chemistry), suspension of fine solid particles or liquid Drop (liquid), droplets in air or another gas. Aerosols can be generated from natural or Human impact on the environment, human causes. The term ''aerosol'' co ...

in a mixture with other chemicals, giving it a yellow-brown color. Mustard agent has also been dispersed in such munitions as aerial bomb

An aerial bomb is a type of Explosive weapon, explosive or Incendiary device, incendiary weapon intended to travel through the Atmosphere of Earth, air on a predictable trajectory. Engineers usually develop such bombs to be dropped from an aircra ...

s, land mine

A land mine, or landmine, is an explosive weapon often concealed under or camouflaged on the ground, and designed to destroy or disable enemy targets as they pass over or near it. Land mines are divided into two types: anti-tank mines, wh ...

s, mortar rounds, artillery shell

A shell, in a modern military context, is a projectile whose payload contains an explosive, incendiary device, incendiary, or other chemical filling. Originally it was called a bombshell, but "shell" has come to be unambiguous in a military ...

s, and rocket

A rocket (from , and so named for its shape) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using any surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely ...

s. Exposure to mustard agent was lethal in about 1% of cases. Its effectiveness was as an incapacitating agent

Incapacitating agent is a chemical or biological agent which renders a person unable to harm themselves or others, regardless of consciousness.

Lethal agents are primarily intended to kill, but incapacitating agents can also kill if administered ...

. The early countermeasures against mustard agent were relatively ineffective, since a soldier wearing a gas mask

A gas mask is a piece of personal protective equipment used to protect the wearer from inhaling airborne pollutants and toxic gases. The mask forms a sealed cover over the nose and mouth, but may also cover the eyes and other vulnerable soft ...

was not protected against absorbing it through his skin and being blistered. A common countermeasure was using a urine-soaked mask or facecloth to prevent or reduce injury, a readily available remedy attested by soldiers in documentaries (e.g., ''They Shall Not Grow Old'' in 2018) and others (such as forward aid nurses) interviewed between 1947 and 1981 by the British Broadcasting Corporation for various World War One history programs; however, the effectiveness of this measure is unclear.

Mustard gas can remain in the ground for weeks, and it continues to cause ill effects. If mustard agent contaminates one's clothing and equipment while cold, then other people with whom they share an enclosed space could become poisoned as contaminated items warm up enough material to become an airborne toxic agent. An example of this was depicted in a British and Canadian documentary about life in the trenches, particularly once the "sousterrain" (subways and berthing areas underground) were completed in Belgium and France. Towards the end of World War I, mustard agent was used in high concentrations as an area-denial weapon that forced troops to abandon heavily contaminated areas.

Since World War I, mustard gas has been used in several wars and other conflicts, usually against people who cannot retaliate in kind:Blister Agent: Mustard gas (H, HD, HS)

Since World War I, mustard gas has been used in several wars and other conflicts, usually against people who cannot retaliate in kind:Blister Agent: Mustard gas (H, HD, HS), CBWinfo.com * United Kingdom against the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

in 1919

* Alleged British use in Mesopotamia in 1920

* Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

against the Rifian resistance in Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

during the Rif War

The Rif War (, , ) was an armed conflict fought from 1921 to 1926 between Spain (joined by France in 1924) and the Berber tribes of the mountainous Rif region of northern Morocco.

Led by Abd el-Krim, the Riffians at first inflicted several ...

of 1921–27 (see also: ''Spanish use of chemical weapons in the Rif War

During the Third Rif War in Spanish Morocco between 1921 and 1927, the Spanish Army of Africa deployed chemical weapons in an attempt to put down the Berber rebellion against colonial rule in the region of the Rif led by the guerrilla Abd el-Kr ...

'')

* Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

in Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

in 1930

* The Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

in Xinjiang

Xinjiang,; , SASM/GNC romanization, SASM/GNC: Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Sinkiang, officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People' ...

, Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

, during the Soviet Invasion of Xinjiang against the 36th Division (National Revolutionary Army)

The New 36th Division was a cavalry division in the National Revolutionary Army. It was created in 1932 by the Kuomintang for General Ma Zhongying, who was also its first commander. It was made almost entirely out of Hui Muslim troops, all of ...

in 1934, and also in the Xinjiang War (1937)

In 1937, 1,500 Uyghur Muslim rebels under the command of Kichik Akhund rebelled in southern Xinjiang against the pro-Soviet forces of Sheng Shicai. The rebels were tacitly aided by the New 36th Division of the Chinese National Revolutionary ...

in 1936–37

* Italy against Abyssinia

Abyssinia (; also known as Abyssinie, Abissinia, Habessinien, or Al-Habash) was an ancient region in the Horn of Africa situated in the northern highlands of modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea.Sven Rubenson, The survival of Ethiopian independence, ...

(now Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

) in the 1935–1936

* The Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

against China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

in the 1937–1945

* The US military conducted experiments with chemical weapons like lewisite and mustard gas on Japanese American, Puerto Rican and African Americans in the US military in World War II to see how non-white races would react to being mustard gassed, with Rollin Edwards describing it as "It felt like you were on fire, guys started screaming and hollering and trying to break out. And then some of the guys fainted. And finally they opened the door and let us out, and the guys were just, they were in bad shape." and "It took all the skin off your hands. Your hands just rotted".

* After World War II, stockpiled mustard gas was dumped by South African military personnel under the command of William Bleloch off Port Elizabeth

Gqeberha ( , ), formerly named Port Elizabeth, and colloquially referred to as P.E., is a major seaport and the most populous city in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It is the seat of the Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan Municipal ...

, resulting in several cases of burns among local trawler crews.

* The United States Government tested effectiveness on US Naval recruits in a laboratory setting at The Great Lakes Naval Base, June 3, 1945

* The 2 December 1943 air raid on Bari

The air raid on Bari (, ) was an air attack by German bombers on Allied forces and shipping in Bari, Italy, on 2 December 1943, during World War II. 105 German Junkers Ju 88 bombers of ''Luftflotte'' 2 surprised the port's defenders and bombed ...

destroyed an Allied stockpile of mustard gas on the SS ''John Harvey'', killing 83 and hospitalizing 628.

* Egypt against North Yemen

North Yemen () is a term used to describe the Kingdom of Yemen (1918-1962), the Yemen Arab Republic (1962-1990), and the regimes that preceded them and exercised sovereignty over that region of Yemen. Its capital was Sanaa from 1918 to 1948 an ...

in 1963–1967

* Iraq against Kurds

Kurds (), or the Kurdish people, are an Iranian peoples, Iranic ethnic group from West Asia. They are indigenous to Kurdistan, which is a geographic region spanning southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northeastern Syri ...

in the town of Halabja

Halabja (, ) is a city in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and the capital of Halabja Governorate, located about northeast of Baghdad and from the Iranian border.

The city lies at the base of what is often referred to as the greater Hewraman re ...

during the Halabja chemical attack

The Halabja massacre ( ) took place in Iraqi Kurdistan on 16 March 1988, when thousands of Kurds were killed by a large-scale Iraqi chemical weapons program, Iraqi chemical attack. A targeted attack in Halabja, it was carried out during the Anfa ...

in 1988

* Iraq against Iranians in 1983–1988

* Possibly in Sudan against insurgents in the civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, in 1995 and 1997.

* In the Iraq War

The Iraq War (), also referred to as the Second Gulf War, was a prolonged conflict in Iraq lasting from 2003 to 2011. It began with 2003 invasion of Iraq, the invasion by a Multi-National Force – Iraq, United States-led coalition, which ...

, abandoned stockpiles of mustard gas shells were destroyed in the open air, and were used against Coalition forces in roadside bomb

An improvised explosive device (IED) is a bomb constructed and deployed in ways other than in conventional warfare, conventional military action. It may be constructed of conventional military explosives, such as an artillery shell, attached t ...

s.

* By ISIS

Isis was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kingdom () as one of the main characters of the Osiris myth, in which she resurrects her sla ...

forces against Kurdish

Kurdish may refer to:

*Kurds or Kurdish people

*Kurdish language

** Northern Kurdish (Kurmanji)

**Central Kurdish (Sorani)

**Southern Kurdish

** Laki Kurdish

*Kurdish alphabets

*Kurdistan, the land of the Kurdish people which includes:

**Southern ...

forces in Iraq in August 2015.

* By ISIS against another rebel group in the town of Mare'

Mare' ( ''Māriʿ'', locally pronounced ''Mēreʿ''), also spelled Marea, is a town in northern Aleppo Governorate, northwestern Syria. It is the largest town and administrative centre of the Mare' nahiyah in the Azaz District. Located some 25 ...

in 2015.

* According to Syrian state media, by ISIS against the Syrian Army

The Syrian Army is the land force branch of the Syrian Armed Forces. Up until the fall of the Assad regime, the Syrian Arab Army existed as a land force branch of the Syrian Arab Armed Forces, which dominanted the military service of the fo ...

during the battle in Deir ez-Zor

Deir ez-Zor () is the largest city in eastern Syria and the seventh largest in the country. Located on the banks of the Euphrates to the northeast of the capital Damascus, Deir ez-Zor is the capital of the Deir ez-Zor Governorate. In the 2018 ...

in 2016.

The use of toxic gases or other chemicals, including mustard gas, during warfare is known as chemical warfare, and this kind of warfare was prohibited by the Geneva Protocol of 1925, and also by the later Chemical Weapons Convention of 1993. The latter agreement also prohibits the development, production, stockpiling, and sale of such weapons.

In September 2012, a US official stated that the rebel militant group ISIS

Isis was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kingdom () as one of the main characters of the Osiris myth, in which she resurrects her sla ...

was manufacturing and using mustard gas in Syria and Iraq, which was allegedly confirmed by the group's head of chemical weapons development, Sleiman Daoud al-Afari, who has since been captured.

Development of the first chemotherapy drug

As early as 1919 it was known that mustard agent was a suppressor ofhematopoiesis

Haematopoiesis (; ; also hematopoiesis in American English, sometimes h(a)emopoiesis) is the formation of blood cellular components. All cellular blood components are derived from haematopoietic stem cells. In a healthy adult human, roughly ten ...

. In addition, autopsies performed on 75 soldiers who had died of mustard agent during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

were done by researchers from the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (Penn or UPenn) is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. One of nine colonial colleges, it was chartered in 1755 through the efforts of f ...

who reported decreased counts of white blood cell

White blood cells (scientific name leukocytes), also called immune cells or immunocytes, are cells of the immune system that are involved in protecting the body against both infectious disease and foreign entities. White blood cells are genera ...

s. This led the American Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) to finance the biology and chemistry departments at Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

to conduct research on the use of chemical warfare during World War II.

As a part of this effort, the group investigated nitrogen mustard

Nitrogen mustards (NMs) are cytotoxic organic compounds with the bis(2-chloroethyl)amino ((ClC2H4)2NR) functional group. Although originally produced as chemical warfare agents, they were the first chemotherapeutic agents for treatment of canc ...

as a therapy for Hodgkin's lymphoma

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a type of lymphoma in which cancer originates from a specific type of white blood cell called lymphocytes, where multinucleated Reed–Sternberg cells (RS cells) are present in the lymph nodes. The condition was named a ...

and other types of lymphoma

Lymphoma is a group of blood and lymph tumors that develop from lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell). The name typically refers to just the cancerous versions rather than all such tumours. Signs and symptoms may include enlarged lymph node ...

and leukemia

Leukemia ( also spelled leukaemia; pronounced ) is a group of blood cancers that usually begin in the bone marrow and produce high numbers of abnormal blood cells. These blood cells are not fully developed and are called ''blasts'' or '' ...

, and this compound was tried out on its first human patient in December 1942. The results of this study were not published until 1946, when they were declassified. In a parallel track, after the air raid on Bari

The air raid on Bari (, ) was an air attack by German bombers on Allied forces and shipping in Bari, Italy, on 2 December 1943, during World War II. 105 German Junkers Ju 88 bombers of ''Luftflotte'' 2 surprised the port's defenders and bombed ...

in December 1943, the doctors of the U.S. Army noted that white blood cell counts were reduced in their patients. Some years after World War II was over, the incident in Bari and the work of the Yale University group with nitrogen mustard converged, and this prompted a search for other similar chemical compound

A chemical compound is a chemical substance composed of many identical molecules (or molecular entities) containing atoms from more than one chemical element held together by chemical bonds. A molecule consisting of atoms of only one element ...

s. Due to its use in previous studies, the nitrogen mustard called "HN2" became the first cancer chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (often abbreviated chemo, sometimes CTX and CTx) is the type of cancer treatment that uses one or more anti-cancer drugs (list of chemotherapeutic agents, chemotherapeutic agents or alkylating agents) in a standard chemotherapy re ...

drug, chlormethine

Chlormethine (INN, BAN), also known as mechlorethamine (USAN, USP), mustine, HN2, and (in post-Soviet states) embikhin (эмбихин), is a nitrogen mustard sold under the brand name Mustargen among others. It is the prototype of alkylating ...

(also known as mechlorethamine, mustine) to be used. Chlormethine and other mustard gas molecules are still used to this day as an chemotherapy agent albeit they have largely been replaced with more safe chemotherapy drugs like cisplatin

Cisplatin is a chemical compound with chemical formula, formula ''cis''-. It is a coordination complex of platinum that is used as a chemotherapy medication used to treat a number of cancers. These include testicular cancer, ovarian cancer, c ...

and carboplatin

Carboplatin, sold under the brand name Paraplatin among others, is a chemotherapy medication used to treat a number of forms of cancer. This includes ovarian cancer, lung cancer, head and neck cancer, brain cancer, and neuroblastoma. It is a ...

.

Disposal

In the United States, storage and incineration of mustard gas and other chemical weapons were carried out by the U.S. Army Chemical Materials Agency. Disposal projects at the two remaining American chemical weapons sites were carried out nearRichmond, Kentucky

Richmond is a home rule-class city in Madison County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 34,585 as of the 2020 census, making it the state's seventh-largest city. It is the principal city of the Richmond–Berea micropolitan area, wh ...

, and Pueblo, Colorado

Pueblo ( ) is a List of municipalities in Colorado#Home rule municipality, home rule municipality that is the county seat of and the List of municipalities in Colorado, most populous municipality in Pueblo County, Colorado, United States. The ...

. The last of the declared mustard weapons stockpile of the United States was destroyed on June 22, 2023 in Pueblo with other remaining chemical weapons being destroyed later in 2023.

New detection techniques are being developed in order to detect the presence of mustard gas and its metabolites. The technology is portable and detects small quantities of the hazardous waste and its oxidized products, which are notorious for harming unsuspecting civilians. The immunochromatographic

Affinity chromatography is a method of separating a biomolecule from a mixture, based on a highly specific macromolecular binding interaction between the biomolecule and another substance. The specific type of binding interaction depends on the ...

assay would eliminate the need for expensive, time-consuming lab tests and enable easy-to-read tests to protect civilians from sulfur-mustard dumping sites.

In 1946, 10,000 drums of mustard gas (2,800 tonnes) stored at the production facility of Stormont Chemicals in Cornwall, Ontario

Cornwall is a city in Eastern Ontario, Canada, situated where the provinces of Central Canada, Ontario and Quebec and the U.S. state of New York (state), New York converge. It is Ontario's easternmost city. Although it is the seat of the United ...

, Canada, were loaded onto 187 boxcars for the journey to be buried at sea on board a long barge south of Sable Island

Sable Island (, literally "island of sand") is a small, remote island off the coast of Nova Scotia, Canada. Sable Island is located in the North Atlantic Ocean, about southeast of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Halifax, and about southeast of the clo ...

, southeast of Halifax, at a depth of . The dump location is 42 degrees, 50 minutes north by 60 degrees, 12 minutes west.

A large British stockpile of old mustard agent that had been made and stored since World War I at M. S. Factory, Valley near Rhydymwyn

) is a village in Flintshire, Wales, located in the upper Alyn valley. Once a district of Mold, it was recognised as a separate parish from 1865. It is now part of the community of Cilcain.

Geography

The geology of the area consists of a layer ...

in Flintshire

Flintshire () is a county in the north-east of Wales. It borders the Irish Sea to the north, the Dee Estuary to the north-east, the English county of Cheshire to the east, Wrexham County Borough to the south, and Denbighshire to the west. ...

, Wales, was destroyed in 1958.

Most of the mustard gas found in Germany after World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

was dumped into the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

. Between 1966 and 2002, fishermen have found about 700 chemical weapons in the region of Bornholm

Bornholm () is a List of islands of Denmark, Danish island in the Baltic Sea, to the east of the rest of Denmark, south of Sweden, northeast of Germany and north of Poland.

Strategically located, Bornholm has been fought over for centuries. I ...

, most of which contain mustard gas. One of the more frequently dumped weapons was "Sprühbüchse 37" (SprüBü37, Spray Can 37, 1937 being the year of its fielding with the German Army). These weapons contain mustard gas mixed with a thickener

A thickening agent or thickener is a substance which can increase the viscosity of a liquid without substantially changing its other properties. Edible thickeners are commonly used to thicken sauces, soups, and puddings without altering their ...

, which gives it a tar-like viscosity. When the content of the SprüBü37 comes in contact with water, only the mustard gas in the outer layers of the lumps of viscous mustard hydrolyzes

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution reaction, substitution, elimination reaction, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water ...

, leaving behind amber-colored residues that still contain most of the active mustard gas. On mechanically breaking these lumps (e.g., with the drag board of a fishing net or by the human hand) the enclosed mustard gas is still as active as it had been at the time the weapon was dumped. These lumps, when washed ashore, can be mistaken for amber, which can lead to severe health problems. Artillery shells

A shell, in a modern military context, is a projectile whose payload contains an explosive, incendiary, or other chemical filling. Originally it was called a bombshell, but "shell" has come to be unambiguous in a military context. A shell c ...

containing mustard gas and other toxic ammunition from World War I (as well as conventional explosives) can still be found in France and Belgium. These were formerly disposed of by explosion undersea, but since the current environmental regulations prohibit this, the French government

The Government of France (, ), officially the Government of the French Republic (, ), exercises Executive (government), executive power in France. It is composed of the Prime Minister of France, prime minister, who is the head of government, ...

is building an automated factory to dispose of the accumulation of chemical shells.

In 1972, the U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a bicameral legislature, including a lower body, the U.S. House of Representatives, and an upper body, the U.S. Senate. They both ...

banned the practice of disposing of chemical weapons into the ocean by the United States. 29,000 tons of nerve and mustard agents had already been dumped into the ocean off the United States by the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of the United Stat ...

. According to a report created in 1998 by William Brankowitz, a deputy project manager in the U.S. Army Chemical Materials Agency

The United States Army Chemical Materials Activity (CMA) is a separate reporting activity of the United States Army Materiel Command (AMC). Its role is to enhance national security by securely storing the remaining U.S. chemical warfare materie ...

, the army created at least 26 chemical weapons dumping sites in the ocean offshore from at least 11 states on both the East Coast and the West Coast (in Operation CHASE

Operation CHASE (an acronym for "Cut Holes And Sink 'Em") was a United States Department of Defense program for the disposal of unwanted munitions at sea from May 1964 until the early 1970s.Kurak, Steve "Operation Chase" ''United States Naval Insti ...

, Operation Geranium

Operation Geranium was a U.S. Army mission that dumped more than 3,000 tons of the chemical agent lewisite into the ocean off the Florida coast in 1948.

Operation

Operation Geranium occurred from 15 – 20 December 1948 and involved the dump ...

, etc.). In addition, due to poor recordkeeping, about one-half of the sites have only their rough locations known.

In June 1997, India declared its stock of chemical weapons of of mustard gas. By the end of 2006, India had destroyed more than 75 percent of its chemical weapons/material stockpile and was granted extension for destroying the remaining stocks by April 2009 and was expected to achieve 100 percent destruction within that time frame. India informed the United Nations in May 2009 that it had destroyed its stockpile of chemical weapons in compliance with the international Chemical Weapons Convention. With this India has become the third country after South Korea and Albania to do so. This was cross-checked by inspectors of the United Nations.

Producing or stockpiling mustard gas is prohibited by the Chemical Weapons Convention

The Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), officially the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction, is an arms control treaty administered by the Organisation for ...

. When the convention entered force in 1997, the parties declared worldwide stockpiles of 17,440 tonnes of mustard gas. As of December 2015, 86% of these stockpiles had been destroyed.

A significant portion of the United States' mustard agent stockpile

A stockpile is a pile or storage location for bulk materials, forming part of the bulk material handling process.

Stockpiles are used in many different areas, such as in a port, refinery or manufacturing facility. The stockpile is normally cr ...

was stored at the Edgewood Area of Aberdeen Proving Ground

Aberdeen Proving Ground (APG) is a U.S. Army facility located adjacent to Aberdeen, Harford County, Maryland, United States. More than 7,500 civilians and 5,000 military personnel work at APG. There are 11 major commands among the tenant units, ...

in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

. Approximately 1,621 tons of mustard agents were stored in one-ton containers on the base under heavy guard. A chemical neutralization plant was built on the proving ground and neutralized the last of this stockpile in February 2005. This stockpile had priority because of the potential for quick reduction of risk to the community. The nearest schools were fitted with overpressurization machinery to protect the students and faculty in the event of a catastrophic explosion and fire at the site. These projects, as well as planning, equipment, and training assistance, were provided to the surrounding community as a part of the Chemical Stockpile Emergency Preparedness Program (CSEPP), a joint program of the Army and the Federal Emergency Management Agency

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is an agency of the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS), initially created under President Jimmy Carter by Presidential Reorganization Plan No. 3 of 1978 and implemented by two Exec ...

(FEMA). Unexploded shells containing mustard gases and other chemical agents are still present in several test ranges in proximity to schools in the Edgewood area, but the smaller amounts of poison gas () present considerably lower risks. These remnants are being detected and excavated systematically for disposal. The U.S. Army Chemical Materials Agency oversaw disposal of several other chemical weapons stockpiles located across the United States in compliance with international chemical weapons treaties. These include the complete incineration of the chemical weapons stockpiled in Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

, Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

, Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

, and Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

. Earlier, this agency had also completed destruction of the chemical weapons stockpile located on Johnston Atoll

Johnston Atoll is an Unincorporated territories of the United States, unincorporated territory of the United States, under the jurisdiction of the United States Air Force (USAF). The island is closed to public entry, and limited access for mana ...

located south of Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

in the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

. The largest mustard agent stockpile, at approximately 6,200 short ton

The short ton (abbreviation: tn

or st), also known as the US ton, is a measurement unit equal to . It is commonly used in the United States, where it is known simply as a ton; however, the term is ambiguous, the single word "ton" being variously ...

s, was stored at the Deseret Chemical Depot in northern Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. It also borders Wyoming to the northea ...

. The incineration of this stockpile began in 2006. In May 2011, the last of the mustard agents in the stockpile were incinerated at the Deseret Chemical Depot, and the last artillery shells containing mustard gas were incinerated in January 2012.

In 2008, many empty aerial bomb

An aerial bomb is a type of Explosive weapon, explosive or Incendiary device, incendiary weapon intended to travel through the Atmosphere of Earth, air on a predictable trajectory. Engineers usually develop such bombs to be dropped from an aircra ...

s that contained mustard gas were found in an excavation at the Marrangaroo Army Base just west of Sydney, Australia.Chemical Warfare in AustraliaMustardgas.org. Retrieved on 29 May 2011. In 2009, a mining survey near

Chinchilla, Queensland

Chinchilla is a rural town and Suburbs and localities (Australia), locality in the Western Downs Region, Queensland, Australia. Chinchilla is known as the 'Melon Capital of Australia', and plays host to a Melon Festival every second year in Febr ...

, uncovered 144 105-millimeter howitzer

The howitzer () is an artillery weapon that falls between a cannon (or field gun) and a mortar. It is capable of both low angle fire like a field gun and high angle fire like a mortar, given the distinction between low and high angle fire break ...

shells, some containing "Mustard H", that had been buried by the U.S. Army during World War II.

In 2014, a collection of 200 bombs was found near the Flemish

Flemish may refer to:

* Flemish, adjective for Flanders, Belgium

* Flemish region, one of the three regions of Belgium

*Flemish Community, one of the three constitutionally defined language communities of Belgium

* Flemish dialects, a Dutch dialec ...

villages of Passendale

Passendale () or Passchendaele ( , ; ) is a rural Belgian village in the Zonnebeke municipality of West Flanders province. It is close to the town of Ypres, situated on the hill ridge separating the historical wetlands of the Yser and Leie val ...

and Moorslede

Moorslede () is a Municipalities of Belgium, municipality located in the Belgium, Belgian province of West Flanders. The municipality comprises the towns of Dadizele, Slypskapelle and Moorslede proper. On 1 January 2006, Moorslede had a total popul ...