Humphrey Prideaux on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Humphrey Prideaux (3 May 1648 – 1 November 1724) was a Cornish churchman and orientalist, Dean of Norwich from 1702. His sympathies inclined to Low Churchism in religion and to

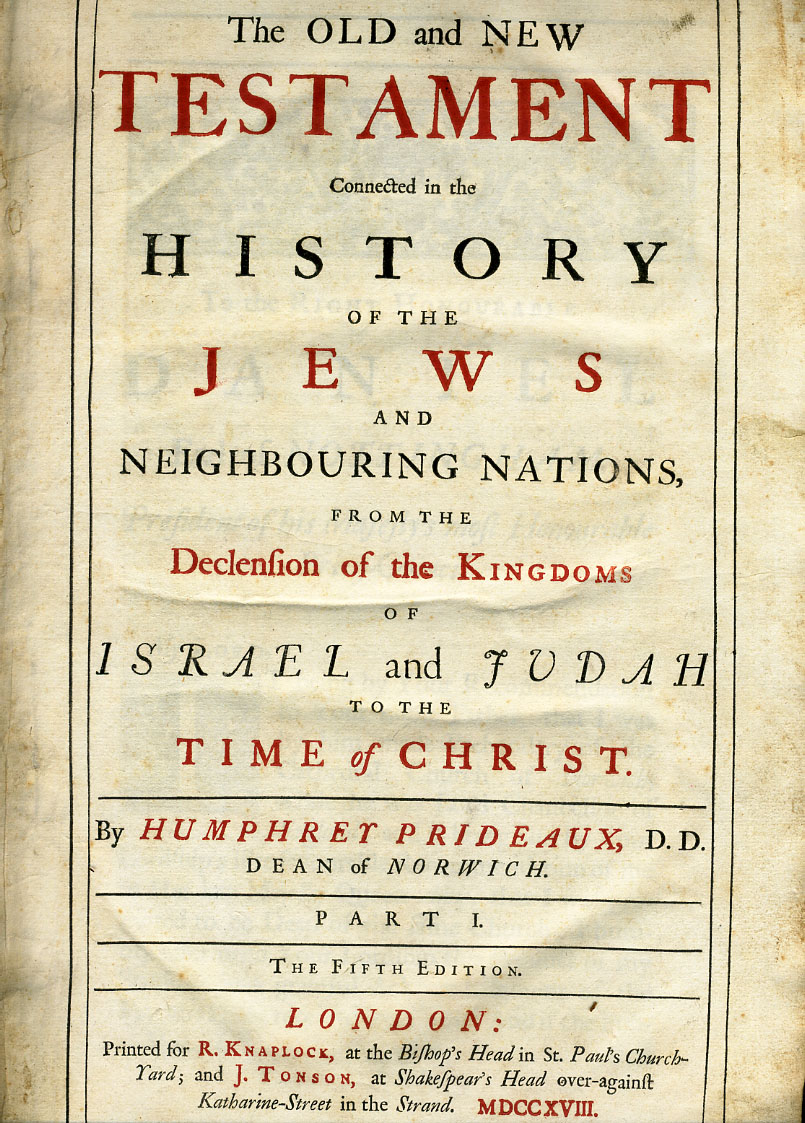

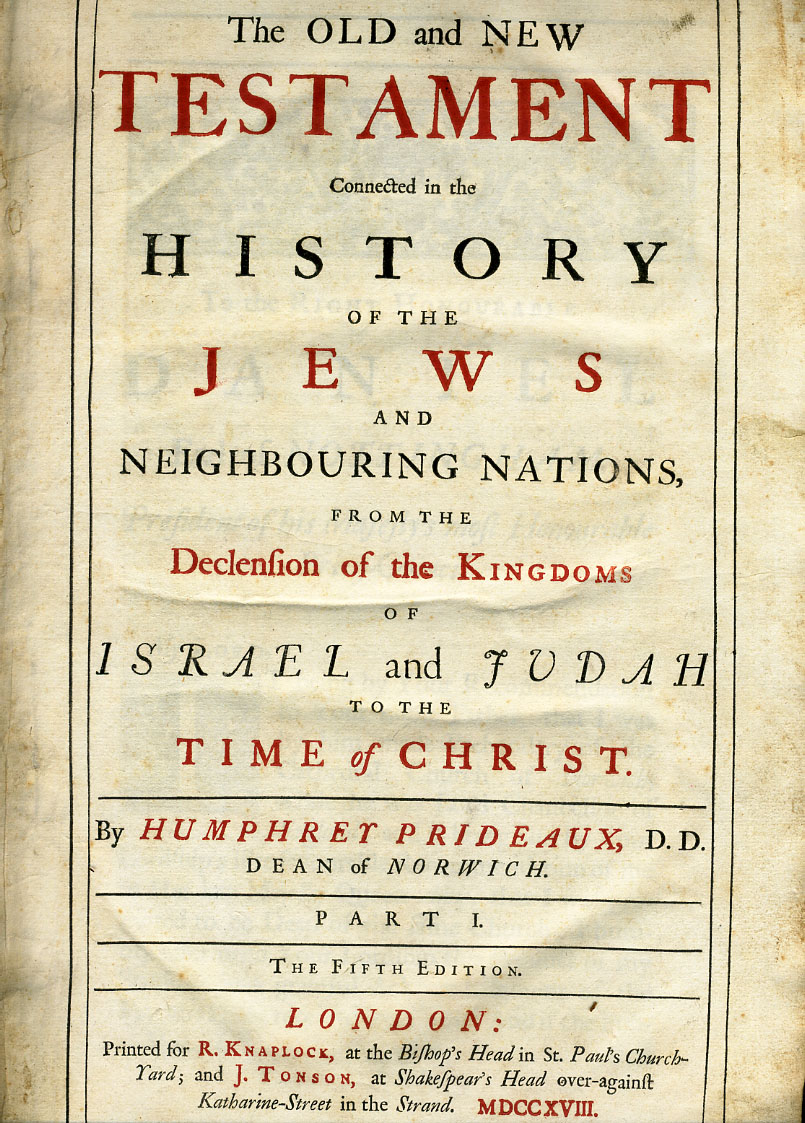

''The Old and New Testament connected in the History of the Jews and Neighbouring Nations'' (1715–17) was a significant work, of which many editions were brought out; it drew on James Ussher. It was among the earliest English works to use the term '' Vulgar Era'', though Kepler used the term as early as 1635. It covered the historical interval between the Old and New Testaments, and led to a controversy between Prideaux and his cousin,

''The Old and New Testament connected in the History of the Jews and Neighbouring Nations'' (1715–17) was a significant work, of which many editions were brought out; it drew on James Ussher. It was among the earliest English works to use the term '' Vulgar Era'', though Kepler used the term as early as 1635. It covered the historical interval between the Old and New Testaments, and led to a controversy between Prideaux and his cousin,

Whiggism

Whiggism or Whiggery is a political philosophy that grew out of the Roundhead, Parliamentarian faction in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms (1639–1653) and was concretely formulated by Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, Lord Shafte ...

in politics.

Life

The third son of Edmond Prideaux, he was born atPadstow

Padstow (; ) is a town, civil parishes in England, civil parish and fishing port on the north coast of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The town is situated on the west bank of the River Camel estuary, approximately northwest of Wadebridge, ...

, Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

, on 3 May 1648. His mother was a daughter of John Moyle. After education at Liskeard grammar school and Bodmin grammar school, he went to Westminster School

Westminster School is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Westminster, London, England, in the precincts of Westminster Abbey. It descends from a charity school founded by Westminster Benedictines before the Norman Conquest, as do ...

under Richard Busby, recommended by his uncle William Morice. On 11 December 1668 he matriculated at Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church (, the temple or house, ''wikt:aedes, ædes'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by Henry V ...

, where he had obtained a studentship. He graduated B.A. 22 June 1672, M.A. 29 April 1675, B.D. 15 November 1682, D.D. 8 June 1686. In January 1674, Prideaux recorded in his letters a visit to his home of William Levett; with Levett came Lord Cornbury, son of the Earl of Clarendon, Levett's principal patron. In other letters, Prideaux mentioned alliances with Levett in ongoing church political manoeuvrings. At the university he was known for scholarship; John Fell employed him in 1672 on an edition of ''Florus

Three main sets of works are attributed to Florus (a Roman cognomen): ''Virgilius orator an poeta'', the ''Epitome of Roman History'' and a collection of 14 short poems (66 lines in all). As to whether these were composed by the same person, or ...

''. He also worked on Edmund Chilmead's edition of the chronicle of John Malalas.

Prideaux gained the patronage of Heneage Finch, 1st Earl of Nottingham

Heneage Finch, 1st Earl of Nottingham, Privy Council of England, PC (23 December 162018 December 1682), Lord Chancellor of England, was descended from the old family of Earl of Winchilsea, Finch, many of whose members had attained high legal emi ...

, as tutor to his son Charles, and in 1677 he obtained the sinecure rectory of Llandewy-Velfrey, Pembrokeshire

Pembrokeshire ( ; ) is a Principal areas of Wales, county in the South West Wales, south-west of Wales. It is bordered by Carmarthenshire to the east, Ceredigion to the northeast, and otherwise by the sea. Haverfordwest is the largest town and ...

. In 1679 Finch presented him to the rectory of St Clement's, Oxford

St Clement's is a district in Oxford, England, on the east bank of the River Cherwell. "St Clement's" is usually taken to describe a small triangular area from The Plain (a roundabout) bounded by the River Cherwell to the North, Cowley Road to ...

, which he held till 1696. He was appointed also, in 1679, Busby's Hebrew lecturer in Christ Church College. Finch gave him in 1681 a canonry at Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of the county of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. It lies by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. The population of the Norwich ...

, and Sir Francis North in February 1683 presented him to the rectory of Bladon

Bladon is a village and Civil parishes in England, civil parish on the River Glyme about northwest of Oxford, Oxfordshire, England. It is where Sir Winston Churchill is buried. The United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 Census recorded the parish's ...

, Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire ( ; abbreviated ''Oxon'') is a ceremonial county in South East England. The county is bordered by Northamptonshire and Warwickshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the east, Berkshire to the south, and Wiltshire and Glouceste ...

, which included the chapelry of Woodstock

The Woodstock Music and Art Fair, commonly referred to as Woodstock, was a music festival held from August 15 to 18, 1969, on Max Yasgur's dairy farm in Bethel, New York, southwest of the town of Woodstock, New York, Woodstock. Billed as "a ...

. He retained his studentship at Christ Church, where he was acting as unsalaried librarian.

Prideaux married and left Oxford for Norwich, ahead of James II's appointment (October 1686) of John Massey, a Roman Catholic, as Dean of Christ Church. He exchanged (1686) Bladon for the rectory of Saham-Toney, Norfolk, which he held till 1694. He engaged in controversy with Roman Catholics, especially on the point of the validity of Anglican orders. As canon of Norwich he improved the financial arrangements of the chapter, and put the records in order. In December 1688 he was made archdeacon of Suffolk by his bishop William Lloyd, an office which he held till 1694. While Lloyd became a nonjuror, Prideaux exerted himself at his archidiaconal visitation (May 1689) to secure the taking of the oaths; out of three hundred parishes in his archdeaconry only three clergymen became nonjurors. At the Convocation

A convocation (from the Latin ''wikt:convocare, convocare'' meaning "to call/come together", a translation of the Ancient Greek, Greek wikt:ἐκκλησία, ἐκκλησία ''ekklēsia'') is a group of people formally assembled for a specia ...

which opened on 21 November 1689 Prideaux was an advocate for changes in the ''Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the title given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christianity, Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The Book of Common Prayer (1549), fi ...

'', with a view to the comprehension of Dissenters

A dissenter (from the Latin , 'to disagree') is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc. Dissent may include political opposition to decrees, ideas or doctrines and it may include opposition to those things or the fiat of ...

. Subsequently he officially corrected a lax interpretation of the Toleration Act 1688, as though it exempted from the duty of attendance on public worship. Gilbert Burnet consulted him in 1691 about a measure for prevention of pluralities

A benefice () or living is a reward received in exchange for services rendered and as a retainer for future services. The Roman Empire used the Latin term as a benefit to an individual from the Empire for services rendered. Its use was adopted by ...

, and Prideaux drafted a bill for this purpose. Richard Kidder consulted him in the same year about a bill for preventing clandestine marriages.

From 1689 to 1694 Prideaux resided at Saham. He declined in 1691 the Oxford Hebrew chair vacated by the death of Edward Pococke, a step which he afterwards regretted. Saham did not suit his health, and he returned to Norwich. In a letter written on 28 November 1694 after receiving the news of John Tillotson's death, he said that he had no expectations of future advancement. Early in 1697 he was presented to the vicarage of Trowse

Trowse (pronounced by those from Norwich and by elderly residents of the village), also called Trowse with Newton, is a village in South Norfolk which lies about south-east of Norwich city centre on the banks of the River Yare. It covers an ...

, near Norwich, a chapter living, which he held till 1709. He succeeded Henry Fairfax as dean of Norwich, and was installed on 8 June 1702. On the translation to Ely (31 July 1707) of John Moore, Prideaux recommended the appointment of Charles Trimnell, his fellow canon, as bishop.

In 1721 Prideaux gave his collection of oriental books to Clare Hall, Cambridge

Clare Hall is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1966 by Clare College, Clare Hall is a college for advanced study, admitting only postgraduate students alongside postdoctoral researchers and fellows. It was est ...

. From about 1709 he had suffered severely from the stone, which prevented him from preaching. An operation was badly managed; attacks of rheumatism and paralysis reduced his strength. He died on 1 November 1724, at the deanery, Norwich, and was buried in the nave of the Norwich Cathedral

Norwich Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, is a Church of England cathedral in the city of Norwich, Norfolk, England. The cathedral is the seat of the bishop of Norwich and the mother church of the dioc ...

, where there was a stone to his memory, with an epitaph composed by himself.

Works

Among his other works were a ''Life of Mahomet'' (1697), with a polemical tract against thedeist

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin term '' deus'', meaning "god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge and asserts that empirical reason and observation ...

s. Its scholarship depended in particular on Pococke. It was criticised by George Sale, in his notes to his translation of the ''Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

''. Its year-of-publication reprint was followed by a third, and a fourth; and four further editions between 1712 and 1718, and yet another reprint in 1723.

''The Old and New Testament connected in the History of the Jews and Neighbouring Nations'' (1715–17) was a significant work, of which many editions were brought out; it drew on James Ussher. It was among the earliest English works to use the term '' Vulgar Era'', though Kepler used the term as early as 1635. It covered the historical interval between the Old and New Testaments, and led to a controversy between Prideaux and his cousin,

''The Old and New Testament connected in the History of the Jews and Neighbouring Nations'' (1715–17) was a significant work, of which many editions were brought out; it drew on James Ussher. It was among the earliest English works to use the term '' Vulgar Era'', though Kepler used the term as early as 1635. It covered the historical interval between the Old and New Testaments, and led to a controversy between Prideaux and his cousin, Walter Moyle

Walter Moyle (1672–1721) was an English politician and political writer, an advocate of classical republicanism.

Life

He was born at Bake, Cornwall, Bake in St Germans, Cornwall, St Germans, Cornwall, on 3 November 1672, the third, but eldes ...

. Jean Le Clerc wrote a critical examination of it, which was published in English in 1722. The French translation was by Moses Solanus and Jean-Baptiste Brutel de la Rivière.

He published the following pamphlets: ''The Validity of the Orders of the Church of England'' (1688), ''Letter to a Friend on the Present Convocation'' (1690), ''The Case of Clandestine Marriages stated'' (1691). Other works were:

* ''Marmora Oxoniensia'', &c., Oxford, 1676, a catalogue and chronology of the Arundel marbles and related collections; the numerous typographical errors were ascribed to the carelessness of Thomas Bennet as corrector of the press. There were later editions, by Michael Maittaire and Richard Chandler.

* ''De Jure Pauperis et Peregrini'', &c., Oxford, 1679, (edition of the Hebrew of Maimonides

Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (, ) and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (), was a Sephardic rabbi and Jewish philosophy, philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah schola ...

, with a Latin version and notes).

* ''A Compendious Introduction for Reading ... Histories'', &c., Oxford, 1682.

* ''Directions to Churchwardens'', &c., Norwich, 1701; 7th edition, 1730.

* ''The Original and Right of Tithes'', &c., Norwich, 1710; reprinted 1713; 1736.

* ''Ecclesiastical Tracts'', &c., 1716.

His letters (1674–1722) to John Ellis were edited for the Camden Society in 1875 by Edward Maunde Thompson.

Marriage and children

On 16 February 1686 Prideaux married Bridget Bokenham, only child of Anthony Bokenham of Helmingham, Suffolk, and left a son: * Edmund Prideaux (1693-1745) ofPrideaux Place

Prideaux Place is a Listed building, grade I listed Elizabethan architecture, Elizabethan country house in the parish of Padstow, Cornwall, England. It has been the home of the Prideaux family for over 400 years. The house was built in 1592 by ...

, Padstow

Padstow (; ) is a town, civil parishes in England, civil parish and fishing port on the north coast of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The town is situated on the west bank of the River Camel estuary, approximately northwest of Wadebridge, ...

, Cornwall, a lawyer of the Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court entitled to Call to the bar, call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple (with whi ...

and a talented amateur architectural artist.

Notes

References

;AttributionFurther reading

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Prideaux, Humphrey 1648 births 1724 deaths People from Padstow People educated at Westminster School, London Christian Hebraists Deans of Norwich Archdeacons of Suffolk People educated at Liskeard Grammar School 17th-century Anglican theologians 18th-century Anglican theologians Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford