Human Zoos on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Human zoos, also known as ethnological expositions, were a colonial practice of publicly displaying people, usually in a so-called "natural" or "primitive" state. They were most prominent during the 19th and 20th centuries. These displays often emphasized the supposed inferiority of the exhibits' culture, and implied the superiority of "

The abstract concept of human displays in zoos has been documented throughout the duration of colonial history. In the

The abstract concept of human displays in zoos has been documented throughout the duration of colonial history. In the

On Monday, 8 September 1906, after just two days, Hornaday decided to close the exhibition, and Benga could be found walking the zoo grounds, often followed by a crowd "howling, jeering and yelling."

On Monday, 8 September 1906, after just two days, Hornaday decided to close the exhibition, and Benga could be found walking the zoo grounds, often followed by a crowd "howling, jeering and yelling."

Human zoos. The invention of the savage

, Dir. Pascal Blanchard, Gilles Boëtsch, Nanette Jacomijn Snoep – exhibition catalogue – Actes Sud (2011) * ''Sauvages. Au cœur des zoos humains'', Dir. Pascal Blanchard, Bruno Victor-Pujebet – 90 minutes – Bonne Pioche production & Archipel (2018)

''Human Zoos: America's Forgotten History of Scientific Racism''

Dir. John G. West (2019)

'Völkerschauen' and the Display of the 'Other'

', European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, 2012. # Grant, Kevin. ''A Civilised Savagery: Britain and the New Slaveries in Africa, 1884–1926''. New York; Oxfordshire, England: Routledge, 2005. # Lewis, R. Barry. ''Understanding humans : introduction to physical anthropology and archaeology.'' Belmont, Calif. Wadsworth Cengage Learning. 2010. # Oliveira, Cinthya

''Human Rights & Exhibitions, 1789–1989,''

''Journal of Museum Ethnography'', no. 29, 2016, pp. 71–94. # Penny, H. Glenn

''Objects of Culture : Ethnology and Ethnographic Museums in Imperial Germany''

The University of North Carolina Press, 2002. # Porter, Louis, Porter, A. N., and Louis, William Roger. ''The Oxford History of the British Empire''. Volume III, The Nineteenth Century. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999. Oxford History of the British Empire. Web. # Qureshi, Sadiah. ''Robert Gordon Latham, Displayed Peoples, and the Natural History of Race: 1854–1866,'' ''The Historical Journal'', vol. 54, no. 1, 2011, pp

143–166

# Rothfels, Nigel.

Savages and Beasts : The Birth of the Modern Zoo

', Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002. # Schofield, Hugh

Human Zoos: When Real People Were Exhibits

BBC News, 2011.

India Andaman Jarawa Tribe in 'Shocking' Tourist Video

BBC News, 2012.

Human Zoos. The Invention of the Savage

Human Zoos website

* ;

"On A Neglected Aspect Of Western Racism"

by Kurt Jonassohn, December 2000

''The Colonial Exposition of May 1931''

by

"Official site of the Adelaide Human Zoo"

* Qureshi, Sadiah (2004), 'Displaying Sara Baartman, the 'Hottentot Venus', ''History of Science'' 42:233–257. Available online a

Science History Publications

{{DEFAULTSORT:Human Zoo Anthropology Colonial exhibitions Ethnography Ethnological show business History of colonialism History by ethnic group Scientific racism Sideshow attractions White supremacy Zoos

Western society

Western culture, also known as Western civilization, European civilization, Occidental culture, Western society, or simply the West, refers to the Cultural heritage, internally diverse culture of the Western world. The term "Western" encompas ...

", through tropes that depicted marginalized groups as "savage". They then developed into independent displays emphasizing the exhibits' inferiority to western culture and providing further justification for their subjugation. Such displays featured in multiple colonial exhibitions

A colonial exhibition was a type of World's fair, international exhibition that was held to boost trade. During the 1880s and beyond, colonial exhibitions had the additional aim of bolstering popular support for the various colonial ...

and at temporary exhibitions in animal zoos.

Etymology

The term "human zoo" was not generally used by contemporaries of the shows, and was popularised by the French researcher Pascal Blanchard. The term has been criticised for denying the agency of the shows' non-European performers.Circuses and freak shows

The abstract concept of human displays in zoos has been documented throughout the duration of colonial history. In the

The abstract concept of human displays in zoos has been documented throughout the duration of colonial history. In the Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the Prime Meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the 180th meridian.- The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Geopolitically, ...

, one of the earliest-known zoo

A zoo (short for zoological garden; also called an animal park or menagerie) is a facility where animals are kept within enclosures for public exhibition and often bred for conservation purposes.

The term ''zoological garden'' refers to zoology, ...

s, that of Moctezuma

Montezuma or Moctezuma may refer to:

People

* Moctezuma I (1398–1469), the second Aztec emperor and fifth king of Tenochtitlan

* Moctezuma II (c. 1460–1520), ninth Aztec emperor

** Pedro Moctezuma, a son of Montezuma II

** Isabel Moctezuma ...

in Mexico, consisted not only of a vast collection of animals, but also exhibited humans, for example, dwarves, albinos and hunchbacks.

During the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

, the Medici

The House of Medici ( , ; ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first consolidated power in the Republic of Florence under Cosimo de' Medici and his grandson Lorenzo "the Magnificent" during the first half of the 15th ...

developed a large menagerie

A menagerie is a collection of captive animals, frequently exotic, kept for display; or the place where such a collection is kept, a precursor to the modern zoo or zoological garden.

The term was first used in 17th-century France, referring to ...

in the Vatican. In the 16th century, Cardinal Hippolytus Medici had a collection of people of different races as well as exotic animals. He is reported as having a troupe of so-called Savages, speaking over twenty languages; there were also Moors, Tartars, Indians, Turks and Africans. In 1691, Englishman William Dampier

William Dampier (baptised 5 September 1651; died March 1715) was an English explorer, pirate, privateer, navigator, and naturalist who became the first Englishman to explore parts of what is today Australia, and the first person to circumnavig ...

exhibited a tattooed native of Miangas

Miangas or Palmas is the northernmost island of North Sulawesi, and one of 92 officially listed outlying islands of Indonesia.

Etymology

''Miangas'' means "exposed to piracy", because pirates from Mindanao used to visit the island. In the Sasa ...

whom he bought when he was in Mindanao

Mindanao ( ) is the List of islands of the Philippines, second-largest island in the Philippines, after Luzon, and List of islands by population, seventh-most populous island in the world. Located in the southern region of the archipelago, the ...

. He also intended to exhibit the man's mother to earn more profit, but the mother died at sea. The man was named Jeoly, falsely branded as "Prince Giolo" to attract more audience, and was exhibited for three months straight until he died of smallpox in London.

One of the first modern public human exhibitions was P. T. Barnum

Phineas Taylor Barnum (July 5, 1810 – April 7, 1891) was an American showman, businessman, and politician remembered for promoting celebrated hoaxes and founding with James Anthony Bailey the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. He was ...

's exhibition of Joice Heth

Joice Heth (c. 1756 February 19, 1836)"Joice Heth", Hoaxes.org was an African-American woman who was exhibited by P.T. Barnum with the false claim that she was the 161-year-old nursing mammy of George Washington. Her exhibition under these cl ...

on 25 February 1835 and, subsequently, the Siamese twins

Conjoined twins, popularly referred to as Siamese twins, are twins joined '' in utero''. It is a very rare phenomenon, estimated to occur in anywhere between one in 50,000 births to one in 200,000 births, with a somewhat higher incidence in south ...

Chang and Eng Bunker

Chang Bunker (จัน บังเกอร์) and Eng Bunker (อิน บังเกอร์) (May 11, 1811 – January 17, 1874) were Siamese (Thai)-American conjoined twins, conjoined twin brothers whose fame propelled the expression " ...

. These exhibitions were common in freak show

A freak show is an exhibition of biological rarities, referred to in popular culture as "Freak, freaks of nature". Typical features would be physically unusual Human#Anatomy and physiology, humans, such as those uncommonly large or small, t ...

s. Another famous example was that of Saartjie Baartman

Sarah Baartman (; 1789 – 29 December 1815), also spelled Sara, sometimes in the diminutive form Saartje (), or Saartjie, and Bartman, Bartmann, was a Khoekhoe woman who was exhibited as a freak show attraction in 19th-century Europe under ...

of the Namaqua, often referred to as the Hottentot Venus, who was displayed in London and France until her death in 1815.

During the 1850s, Maximo and Bartola

Máximo and Bartola (also known as Maximo Valdez Nunez and Bartola Velasquez respectively) were the stage names of two Salvadoran siblings both with microcephaly and cognitive developmental disability who were exhibited in human zoos in the 19 ...

, two microcephalic

Microcephaly (from Neo-Latin ''microcephalia'', from Ancient Greek μικρός ''mikrós'' "small" and κεφαλή ''kephalé'' "head") is a medical condition involving a smaller-than-normal head. Microcephaly may be present at birth or it m ...

children from El Salvador, were exhibited in the US and Europe under the names Aztec Children and Aztec Lilliputians. However, human zoos would become common only in the 1870s in the midst of the New Imperialism

In History, historical contexts, New Imperialism characterizes a period of Colonialism, colonial expansion by European powers, the American imperialism, United States, and Empire of Japan, Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. ...

period.

From 1936 to 1943, the Canadian province of Ontario displayed five White French Canadian

French Canadians, referred to as Canadiens mainly before the nineteenth century, are an ethnic group descended from French people, French colonists first arriving in Canada (New France), France's colony of Canada in 1608. The vast majority of ...

quintuplets, whom the provincial government had removed from their birth family, in a human zoo called Quintland.

Start of human exhibits

In the 1870s, exhibitions of so-called "exotic populations" became popular throughout the western world. Human zoos could be seen in many of Europe's largest cities, such as Paris, Hamburg, London, andMilan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

, as well as American cities such as New York City and Chicago. Carl Hagenbeck

Carl Hagenbeck (10 June 1844 – 14 April 1913) was a Germans, German merchant of wild animals who supplied many European zoos, as well as P. T. Barnum. He created the modern zoo with animal enclosures without bars that were closer to their natur ...

, an animal trader, was one of the early proponents of this trend, when in 1874, at the suggestion of Heinrich Leutemann

Gottlob Heinrich (Henrik) Leutemann (8 October 1824 — 14 December 1905) was a German artist and book illustrator. He was born in Leipzig and studied there.

He produced lithographs for instructional posters.

In the 1850s, he worked on pictu ...

, he decided to exhibit Sami people

Acronyms

* SAMI, ''Synchronized Accessible Media Interchange'', a closed-captioning format developed by Microsoft

* Saudi Arabian Military Industries, a government-owned defence company

* South African Malaria Initiative, a virtual expertise ...

with the 'Laplander Exhibition'. What differentiated Hagenbeck's exhibit from others, was the fact that he showed these people, with animals and plants, to "re-create", their "natural environment." He sold people the feeling of having travelled to these areas by witnessing his exhibits. These exhibits were a massive success, and only became larger and more elaborate. From this point forward human exhibitions would lean towards stereotyping, and projecting western superiority. Greater feeding into the Imperialist

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power ( diplomatic power and cultural imperialism). Imperialism fo ...

narrative, that these people's culture merited subjugation. It also promoted scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

, where they were classified as more or less 'civilized' on a scale, from great apes to western Europeans.

Hagenbeck would go on to launch a Nubian Exhibit in 1876, and an Inuit exhibit in 1880. These were also massively successful.

Aside from Hagenbeck, the Jardin d'Acclimatation

The Jardin d'Acclimatation () is a children's amusement park in the northern part of the Bois de Boulogne in western Paris, alongside other attractions.

History

Opened on 6 October 1860 by Napoléon III and Empress Eugénie, this Paris zoo wa ...

was also a hotspot of ethnological exhibits. Geoffroy de Saint-Hilaire, director of the Jardin d'Acclimatation, decided in 1877 to organize two ethnological exhibits that also presented Nubians

Nubians () ( Nobiin: ''Nobī,'' ) are a Nilo-Saharan speaking ethnic group indigenous to the region which is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt. They originate from the early inhabitants of the central Nile valley, believed to be one of th ...

and Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

. That year, the audience of the Jardin d'acclimatation' doubled to one million. Between 1877 and 1912, approximately thirty ethnological exhibitions were presented at the ''Jardin zoologique d'acclimatation''.

These displays were so successful they were incorporated into both the 1878

Events January

* January 5 – Russo-Turkish War: Battle of Shipka Pass IV – Russian and Bulgarian forces defeat the Ottoman Empire.

* January 9 – Umberto I becomes King of Italy.

* January 17 – Russo-Turkish War: ...

and the 1889 Parisian World's Fair, which presented a 'Negro Village'. Visited by 28 million people, the 1889 World's Fair displayed 400 indigenous people as the major attraction.

In Amsterdam the International Colonial and Export Exhibition

The International Colonial and Export Exhibition (Dutch: ''Internationale Koloniale en Uitvoerhandel Tentoonstelling''; French: ''Exposition Universelle Coloniale et d'Exportation Générale'') was a colonial exhibition (a type of World's Fair ...

had a display of people native to Suriname

Suriname, officially the Republic of Suriname, is a country in northern South America, also considered as part of the Caribbean and the West Indies. It is a developing country with a Human Development Index, high level of human development; i ...

, in 1883.

In 1886, the Spanish displayed natives of the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

in an exhibition, as people whom they "civilized". This event added flame to the 1896 Philippine revolution. Queen Consort of Spain, Maria Cristina of Austria, afterwards institutionalized the business of human zoos. By 1887, indigenous Igorot people & animals were sent to Madrid and were exhibited in a human zoo at the newly constructed Palacio de Cristal del Retiro

The Palacio de Cristal ("Glass Palace") is a 19th-century conservatory located in the Buen Retiro Park in Madrid, Spain. It is currently used for art exhibitions.

The Palacio de Cristal, in the shape of a Greek cross, is made almost entirely of ...

.

At both the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition, also known as the Chicago World's Fair, was a world's fair held in Chicago from May 5 to October 31, 1893, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492. The ...

and the 1901 Pan-American Exposition

The Pan-American Exposition was a world's fair held in Buffalo, New York, United States, from May 1 through November 2, 1901. The fair occupied of land on the western edge of what is now Delaware Park–Front Park System, Delaware Park, extending ...

Little Egypt, a bellydancer, was photographed as a catalogued "type" by Charles Dudley Arnold and Harlow Higginbotha.

At the 1895 African Exhibition in The Crystal Palace

The Crystal Palace was a cast iron and plate glass structure, originally built in Hyde Park, London, to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The exhibition took place from 1 May to 15 October 1851, and more than 14,000 exhibitors from around ...

, around eighty people from Somalia

Somalia, officially the Federal Republic of Somalia, is the easternmost country in continental Africa. The country is located in the Horn of Africa and is bordered by Ethiopia to the west, Djibouti to the northwest, Kenya to the southwest, th ...

were displayed in an "exotic" setting.

The Brussels International Exposition (1897)

The Brussels International Exposition (; ) of 1897 was a world's fair held in Brussels, Belgium, from 10 May 1897 through 8 November 1897. There were 27 participating countries, and an estimated attendance of 7.8 million people.

The main venu ...

in Tervuren featured a "Congolese Village" that displayed African people in ersatz interpretations of native settings.

German ethnographs

Ethnology studies in Germany took a new approach in the 1870s as human displays were incorporated into zoos. These exhibits were lauded as 'educational' to the general population by thescientific community

The scientific community is a diverse network of interacting scientists. It includes many "working group, sub-communities" working on particular scientific fields, and within particular institutions; interdisciplinary and cross-institutional acti ...

. Very quickly, the exhibits were used as a way to show that Europeans had "evolved" into a 'superior', 'cosmopolitan' life.

In the late 19th century, German ethnographic museums were seen as an empirical study of human culture. They contained artifacts from cultures around the world organized by continent allowing visitors to see the similarities and differences between the groups and "form their own ideas".

Objectification in human zoos

Within the history of human zoos, there are patterns of overt sexual representation of displayed peoples, most frequently women. Suchobjectification

In social philosophy, objectification is the act of treating a person as an object or a thing. Sexual objectification, the act of treating a person as a mere object of sexual desire, is a subset of objectification, as is self-objectification, th ...

often led to treatment that reflected a lack of privacy and respect, including the dissection and display of bodies after death without consent.

An example of the sexualization of ethnically diverse women in Europe is Saartje Baartman

Sarah Baartman (; 1789 – 29 December 1815), also spelled Sara, sometimes in the diminutive form Saartje (), or Saartjie, and Bartman, Bartmann, was a Khoekhoe woman who was exhibited as a freak show attraction in 19th-century Europe under ...

, often referred to as her anglicized name Sarah Bartmann. Bartmann was displayed both when she was alive throughout England and Ireland and after her death in the Musée de l'Homme

The Musée de l'Homme (; literally "Museum of Mankind" or "Museum of Humanity") is an anthropology museum in Paris, France. It was established in 1937 by Paul Rivet for the 1937 ''Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moder ...

. While alive, she participated in a traveling show depicting her as a "savage female" with a large focus on her body. The clothes she was put in were tight and close to her skin color, and spectators were encouraged to "see for themselves" if Bartmann's body, particularly her buttocks, were real through "poking and pushing". Her living display was financially compensated but there is no record of her consenting to be examined and displayed after death.

Dominika Czarnecka theorizes on the relationship between the radicalization and sexualization of black female bodies in her journal article "Black Female Bodies and the 'White' View." Czarnecka focuses on ethnographic shows that were prominent in Polish territory in the late 19th century. She argues that an essential part of why these shows were so popular is the display of the black female body. Although the women in the shows were meant to be depicting Amazon warriors, their wardrobe was not similar to amazonian dress, and there are several documentations of comments from spectators about their revealing clothes and their bodies.

Although women were most frequently objectified, there are a few instances of "exotic" men being displayed due to their favorable appearance. Angelo Solimann was brought to Italy as a slave from Central Africa in the 18th century, but ended up gaining a reputation in Viennese society for his fighting skills and vast knowledge about language and history. Upon his death in 1796, this positive association did not prevent his body being "stuffed and exhibited in the Viennese Natural History Museum" for almost a decade.

Around the turn of the century

In 1896, to increase the number of visitors, theCincinnati Zoo

The Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden is the second oldest zoo in the United States, founded in 1873 and officially opening in 1875. It is located in the Avondale neighborhood of Cincinnati, Ohio. It originally began with in the middle of the ...

invited one hundred Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin ( ; Dakota/ Lakota: ) are groups of Native American tribes and First Nations people from the Great Plains of North America. The Sioux have two major linguistic divisions: the Dakota and Lakota peoples (translati ...

Native Americans to establish a village at the site. The Sioux lived at the zoo for three months.

The 1900 World's Fair presented the famous diorama

A diorama is a replica of a scene, typically a three-dimensional model either full-sized or miniature. Sometimes dioramas are enclosed in a glass showcase at a museum. Dioramas are often built by hobbyists as part of related hobbies like mili ...

living in Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

, while the Colonial exhibition

A colonial exhibition was a type of World's fair, international exhibition that was held to boost trade. During the 1880s and beyond, colonial exhibitions had the additional aim of bolstering popular support for the various colonial ...

s in Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

s (1906 and 1922) and in Paris (1907 and 1931) also displayed humans in cages, often nude or semi-nude. The 1931 exhibition in Paris was so successful that 34 million people attended it in six months, while a smaller counter-exhibition entitled ''The Truth on the Colonies'', organized by the Communist Party, attracted very few visitors—in the first room, it recalled Albert Londres

Albert Londres (1 November 1884 – 16 May 1932) was a French journalist and writer. One of the inventors of investigative journalism, Londres not only reported news but created it, and reported it from a personal perspective. He criticized abu ...

and André Gide

André Paul Guillaume Gide (; 22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951) was a French writer and author whose writings spanned a wide variety of styles and topics. He was awarded the 1947 Nobel Prize in Literature. Gide's career ranged from his begi ...

's critiques of forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, or violence, including death or other forms of ...

in the colonies. Nomadic Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

ese Villages were also presented.

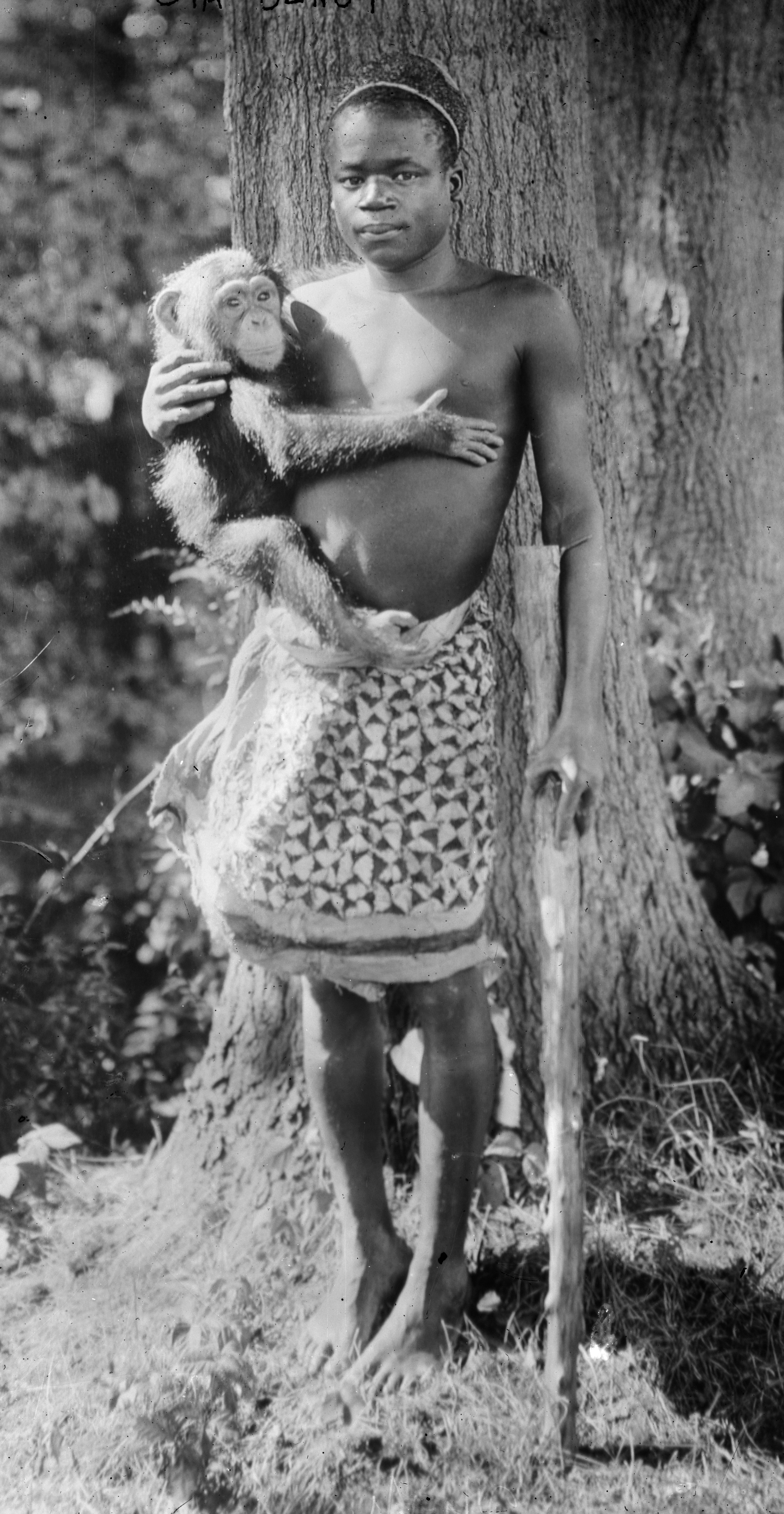

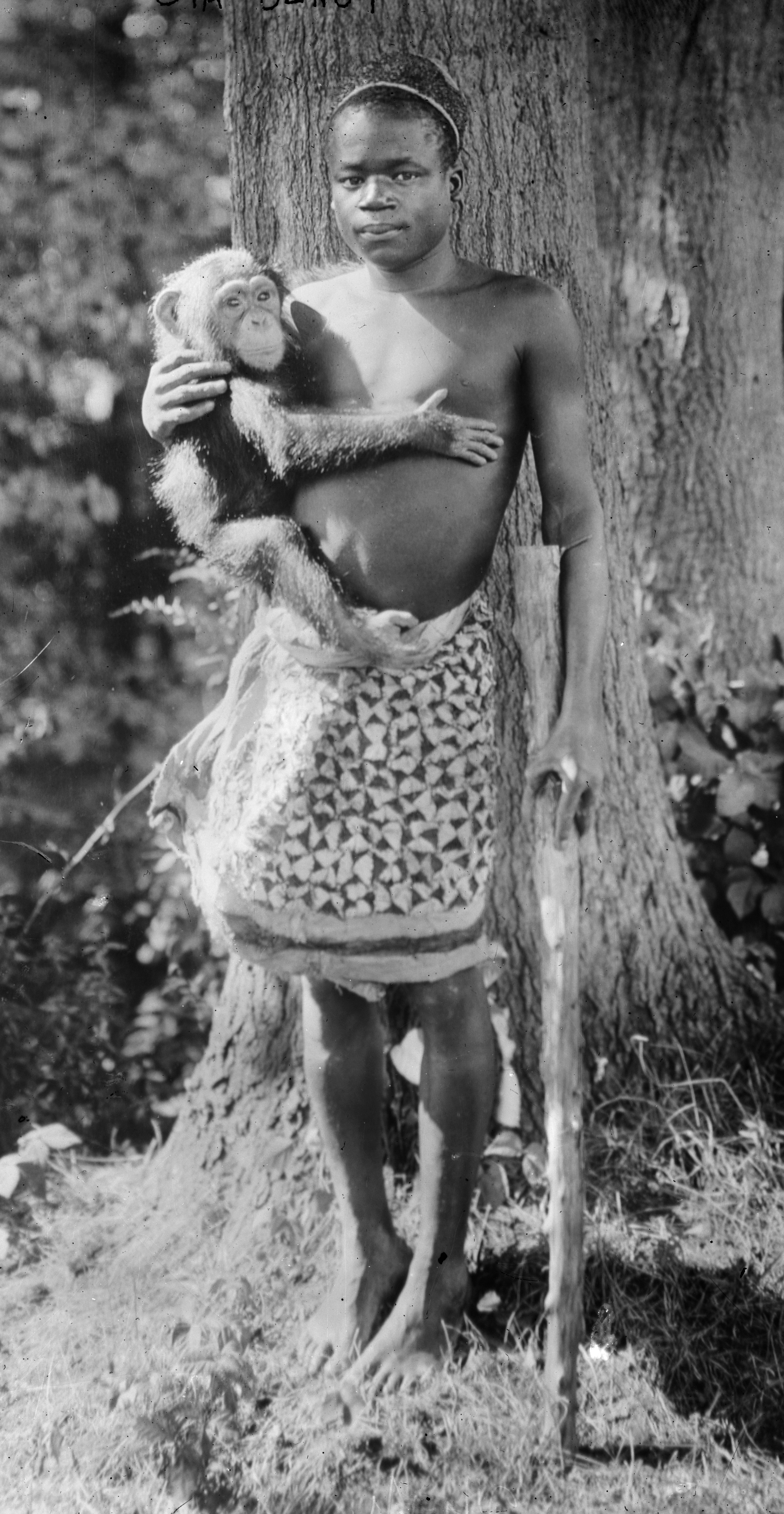

In 1906, Madison Grant

Madison Grant (November 19, 1865 – May 30, 1937) was an American lawyer, zoologist, anthropologist, and writer known for his work as a conservation movement, conservationist, eugenics, eugenicist, and advocate of scientific racism. Grant i ...

—socialite, eugenicist

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetics, genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human Phenotype, phenotypes by ...

, amateur anthropologist

An anthropologist is a scientist engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropologists study aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms, values ...

, and head of the New York Zoological Society

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

** "New" (Paul McCartney song), 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, 1995

* "New" (Daya song), 2017

* "New" (No Doubt song), 1 ...

—had Congolese pygmy Ota Benga

Ota Benga ( – March 20, 1916) was a Mbuti ( Congo pygmy) man, known for being featured in an exhibit at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri, and as a human zoo exhibit in 1906 at the Bronx Zoo. Benga had been p ...

put on display at the Bronx Zoo in New York City alongside ape

Apes (collectively Hominoidea ) are a superfamily of Old World simians native to sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia (though they were more widespread in Africa, most of Asia, and Europe in prehistory, and counting humans are found global ...

s and other animals. At the behest of Grant, the zoo director William Hornaday

William H. D. Hornaday (26 April 1910 – 17 March 1992), affectionately known as "Dr. Bill" to his congregation of over 7,000, was the leading minister at Founder's Church of Religious Science in Los Angeles, California. A former business execu ...

placed Benga displayed in a cage with the chimpanzees, then with an orangutan

Orangutans are great apes native to the rainforests of Indonesia and Malaysia. They are now found only in parts of Borneo and Sumatra, but during the Pleistocene they ranged throughout Southeast Asia and South China. Classified in the genus ...

named Dohong, and a parrot, and labeled him The Missing Link, suggesting that in evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

ary terms Africans like Benga were closer to apes than were Europeans. It triggered protests from the city's clergymen, but the public reportedly flocked to see it. On Monday, 8 September 1906, after just two days, Hornaday decided to close the exhibition, and Benga could be found walking the zoo grounds, often followed by a crowd "howling, jeering and yelling."

On Monday, 8 September 1906, after just two days, Hornaday decided to close the exhibition, and Benga could be found walking the zoo grounds, often followed by a crowd "howling, jeering and yelling."

First organized backlash

According to ''The New York Times'', although "few expressed audible objection to the sight of a human being in a cage with monkeys as companions", controversy erupted as black clergymen in the city took great offense. "Our race, we think, is depressed enough, without exhibiting one of us with the apes", said the Reverend James H. Gordon, superintendent of the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn. "We think we are worthy of being considered human beings, with souls."New York City Mayor

The mayor of New York City, officially mayor of the City of New York, is head of the executive branch of the government of New York City and the chief executive of New York City. The mayor's office administers all city services, public property, ...

George B. McClellan Jr. refused to meet with the clergymen, drawing the praise of Hornaday, who wrote to him: "When the history of the Zoological Park is written, this incident will form its most amusing passage."

As the controversy continued, Hornaday remained unapologetic, insisting that his only intention was to put on an ethnological exhibition. In another letter, he said that he and Grant—who ten years later would publish the racist tract ''The Passing of the Great Race

''The Passing of the Great Race: Or, The Racial Basis of European History'' is a 1916 racist and pseudoscientific book by American lawyer, anthropologist, and proponent of eugenics Madison Grant (1865–1937). Grant expounds a theory of Nordi ...

''—considered it "imperative that the society should not even seem to be dictated to" by the black clergymen.

1903 saw one of the first widespread protests against human zoos, at the "Human Pavilion" of an exposition in Osaka, Japan. The exhibition of Koreans and Okinawans in "primitive" housing incurred protests from the governments of Korea and Okinawa, and a Formosan woman wearing Chinese dress angered a group of Chinese students studying abroad in Tokyo. An Ainu schoolteacher was made to exhibit himself in the zoo to raise money for his schoolhouse, as the Japanese government refused to pay. The fact that the schoolteacher made eloquent speeches and fundraised for his school while wearing traditional dress confused the spectators. An anonymous front-page column in a Japanese magazine condemned these examples and the "Human Pavilion" in total, calling it inhumane to exhibit people as spectacles.

St. Louis World's Fair

In 1904, over 1,100 Filipinos were displayed at theSt. Louis World's Fair

The Louisiana Purchase Exposition, informally known as the St. Louis World's Fair, was an international exposition held in St. Louis, Missouri, United States, from April 30 to December 1, 1904. Local, state, and federal funds totaling $15 mill ...

in association with the 1904 Summer Olympics

The 1904 Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the III Olympiad and also known as St. Louis 1904) were an international multi-sport event held in St. Louis, Missouri, United States, from 1 July to 23 November 1904. Many events were conducted ...

. Following the Spanish-American War

Spanish Americans (, ''hispanoestadounidenses'', or ''hispanonorteamericanos'') are Americans whose ancestry originates wholly or partly from Spain. They are the longest-established European American group in the modern United States, with a ...

, the United States had just acquired new territories such as Guam

Guam ( ; ) is an island that is an Territories of the United States, organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. Guam's capital is Hagåtña, Guam, Hagåtña, and the most ...

, the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

, and Puerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

. The organizers of the World's Fair held " Anthropology Days" on August 12 and 13. Since the 1889 Paris Exposition, human zoos, as a key feature of world's fairs, functioned as demonstrations of anthropological notions of race, progress, and civilization. These goals were followed also at the 1904 World's Fair. Fourteen hundred indigenous people from Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands, East Asia, Africa, the Middle East, South America and North America were displayed in anthropological exhibits that showed them in their natural habitats. Another 1600 indigenous people displayed their culture in other areas of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (LPE), including on the fairgrounds and at the Model School, where American Indian boarding school

American Indian boarding schools, also known more recently as American Indian residential schools, were established in the United States from the mid-17th to the early 20th centuries with a main primary objective of "civilizing" or assimilat ...

students demonstrated their successful assimilation. The sporting event itself took place with the participation of about 100 paid indigenous men (no women participated in Anthropology Days, though some, notably the Fort Shaw Indian School The Fort Shaw Indian School Girls Basketball Team was made up of seven Native Americans in the United States, Native American students from various tribes who attended the Fort Shaw Indian Boarding School in Fort Shaw, Montana, Fort Shaw, Montana, U ...

girls basketball team, did compete in other athletic events at the LPE). Contests included "baseball throwing, shot put, running, broad jumping, weight lifting, pole climbing, and tugs-of-war before a crowd of approximately ten thousand". According to theorist Susan Brownell

Susan Brownell is a Curator's Distinguished professor of anthropology at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. She is known for her work on sport in China, the Olympic Games, World's Fairs, and the anthropology of the body and gender.

Early ...

, world's fairs – with their inclusion of human zoos – and the Olympics were a logical fit at this time, as they "were both linked to an underlying cultural logic that gave them a natural affinity". Also, one of the original intentions of Anthropology Days was to create publicity for the official Olympic events.

While Anthropology Days were not officially part of the Olympics program, they were closely associated with each other at the time, and in history—Brownell notes that even today historians still debate as to which of the LPE events were the "real" Olympic Games.Brownell 2008, p. 3. Additionally, almost all of the 400 athletic events were referred to as "Olympian," and the opening ceremony was held in MayBrownell 2008, p. 43. with dignitaries in attendance, though the official Olympic program did not begin until July 1. Also, as previously noted, one of the original intentions of Anthropology Days was to create publicity for the official Olympic events.Parezo 2008, p. 84.

The exhibitions of the World's Fair inspired US military officer Truman Hunt

Truman Knight Hunt (1866 – February 16, 1916) was an American military officer, medical doctor and showman. In 1904, he put on a traveling human zoo show performed by Filipinos, which was eventually shut down by the United States Federal Governm ...

to start his own human zoo of "Head-Hunting

Headhunting is the practice of human hunting, hunting a human and human trophy collecting, collecting the decapitation, severed human head, head after killing the victim. More portable body parts (such as ear, rhinotomy, nose, or scalping, scal ...

Igorrote

The indigenous peoples of the Cordillera in northern Luzon, Philippines, often referred to by the exonym Igorot people, or more recently, as the Cordilleran peoples, are an ethnic group composed of nine main ethnolinguistic groups whose domains ...

s" in Brooklyn

Brooklyn is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City located at the westernmost end of Long Island in the New York (state), State of New York. Formerly an independent city, the borough is coextensive with Kings County, one of twelv ...

. Reports of questionable living conditions for its Filipino performers led the US Federal government

The Federal Government of the United States of America (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States.

The U.S. federal government is composed of three distinct branches: legislative, execut ...

to investigate Hunt's exhibition, and eventually shut it down after Hunt was found guilty of wage theft

Wage theft is the failing to pay wages or provide employee benefits owed to an employee by contract or law. It can be conducted by employers in various ways, among them are failing to pay overtime; violating minimum wage, minimum-wage laws; the m ...

from the performers.

United Kingdom and France

Between 1 May and 31 October 1908 the Scottish National Exhibition, opened by one of Queen Victoria's grandsons,Prince Arthur of Connaught

Prince Arthur of Connaught (Arthur Frederick Patrick Albert; 13 January 1883 – 12 September 1938) was a British military officer and a grandson of Queen Victoria. He served as Governor-General of the Union of South Africa from 20 November 19 ...

, was held in Saughton Park, Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

. One of the attractions was the Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

Village with its French-speaking Senegalese residents, on show demonstrating their way of life, art and craft while living in beehive huts.

In 1909, the infrastructure of the 1908 Scottish National Exhibition in Edinburgh was used to construct the new Marine Gardens

The Marine Gardens was an entertainment complex located in the Portobello area of Edinburgh, Scotland. Opened in 1909 as a pleasure garden and amusement park on the shores of the Firth of Forth, most of its original attractions apart from the ...

to the coast near Edinburgh at Portobello. A group of Somali men, women and children were shipped over to be part of the exhibition, living in thatched huts.

In 1925, a display at Belle Vue Zoo

Belle Vue Zoological Gardens was a large zoo, amusement park, exhibition hall complex, and Motorcycle speedway, speedway stadium in Belle Vue, Manchester, England, that opened in 1836. The brainchild of John Jennison, the gardens were initially ...

in Manchester, England, was entitled "Cannibals" and featured black Africans in supposedly native dress.

In 1931, around 100 other New Caledonian Kanaks were put on display at the Jardin d'Acclimatation

The Jardin d'Acclimatation () is a children's amusement park in the northern part of the Bois de Boulogne in western Paris, alongside other attractions.

History

Opened on 6 October 1860 by Napoléon III and Empress Eugénie, this Paris zoo wa ...

in Paris.

Spain

Between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, several exhibitions of non-Western people were held in Spain, following those held in other areas like the United Kingdom. The first of them was held in 1887 by the Ministry of Overseas, which exhibited a group of between forty and fiftyFilipino people

Filipinos () are citizens or people identified with the country of the Philippines. Filipinos come from various Austronesian peoples, all typically speaking Filipino language, Filipino, Philippine English, English, or other Philippine language ...

(then a Spanish territory) together with local products and plants in the Retiro Park in Madrid. For this exhibition, the Palacio de Cristal del Retiro

The Palacio de Cristal ("Glass Palace") is a 19th-century conservatory located in the Buen Retiro Park in Madrid, Spain. It is currently used for art exhibitions.

The Palacio de Cristal, in the shape of a Greek cross, is made almost entirely of ...

was built, as well as its pond, which sought to recreate the "natural habitat" of the exposed people. At least four people died during the exhibition. In the following years, private companies organized similar exhibitions in Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

and Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

, including of people who were not from Spanish territories, like the Ashanti or the Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

. Until 1918, exhibitions of African people were held in the Ronda de la Universitat

Ronda () is a municipality of Spain belonging to the province of Málaga, within the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Its population is about 35,000. Ronda is known for its cliffside location and a deep canyon that carries the Guadalevín Riv ...

in Barcelona, which were later taken to other European countries. There are also records of another exhibition in the Ibero-American Exposition of Seville in 1929 and an additional one of Fang people

The Fang people, also known as Fãn or Pahouin, are a Bantu peoples, Bantu ethnic group found in Equatorial Guinea, northern Gabon, and southern Cameroon.Equatorial Guinea

Equatorial Guinea, officially the Republic of Equatorial Guinea, is a country on the west coast of Central Africa. It has an area of . Formerly the colony of Spanish Guinea, its post-independence name refers to its location both near the Equ ...

in Valencia

Valencia ( , ), formally València (), is the capital of the Province of Valencia, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, the same name in Spain. It is located on the banks of the Turia (r ...

in 1942. Until 1997 the "Negro of Banyoles

The Negro of Banyoles (, or ) was a controversial piece of taxidermy of a San individual, which used to be a major attraction in the Darder Museum of Banyoles (Catalonia, Spain). In 2000, the remains of the man were sent to Botswana for burial. ...

", an embalmed African man, was exhibited in the Darder Museum in Girona

Girona (; ) is the capital city of the Province of Girona in the autonomous community of Catalonia, Spain, at the confluence of the Ter, Onyar, Galligants, and Güell rivers. The city had an official population of 106,476 in 2024, but the p ...

.

United States (1930s)

By the 1930s, a new kind of human zoo appeared in America, nude shows masquerading as education. These included theZoro Garden Nudist Colony

Zoro Garden Nudist Colony was an attraction at the 1935–36 California Pacific International Exposition in Balboa Park in San Diego, California. It was located in Zoro Garden, a sunken garden originally created for the 1915-16 Panama–Californ ...

at the Pacific International Exposition in San Diego, California (1935–36) and the Sally Rand Nude Ranch at the Golden Gate International Exposition

The Golden Gate International Exposition (GGIE) was a World's Fair held at Treasure Island in San Francisco, California, U.S. The exposition operated from February 18, 1939, through October 29, 1939, and from May 25, 1940, through September 29, ...

in San Francisco (1939). The former was supposedly a real nudist colony

A naturist resort or nudist resort is an establishment that provides accommodation (or at least camping space) and other amenities for guests in a context where they are invited to practice naturism – that is, a lifestyle of non-sexual socia ...

, which used hired performers instead of actual nudists. The latter featured women wearing cowboy hats, gunbelts and boots, and little else. The Golden Gate fair also featured a "Greenwich Village" show, described in the Official Guide Book as "Model artists' colony and revue theatre."

Ethnological expositions during Nazi Germany

As ethnogenic expositions were discontinued in Germany around 1931, there were many repercussions for the performers. Many of the people brought from their homelands to work in the exhibits had created families in Germany, and there were many children that had been born in Germany. Once they no longer worked in the zoos or for performance acts, these people were stuck living in Germany where they had no rights and were harshly discriminated against. During the rise of the Nazi party, the foreign actors in these stage shows were typically able to stay out of concentration camps because there were so few of them that the Nazis did not see them as a real threat."'You Better Go Back to Africa', Interview." ''"You Better Go Back to Africa", Interview'', DW English, 18 June 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=baGXUsOKBcU. Although they were able to avoid concentration camps, they were not able to participate in German life as citizens of ethnically German origin could. TheHitler Youth

The Hitler Youth ( , often abbreviated as HJ, ) was the youth wing of the German Nazi Party. Its origins date back to 1922 and it received the name ("Hitler Youth, League of German Worker Youth") in July 1926. From 1936 until 1945, it was th ...

did not allow children of foreign parents to participate, and adults were rejected as German soldiers. Many ended up working in war industry factories or foreign laborer camps.

Hans Massaquoi

Hans-Jürgen Massaquoi (January 19, 1926 – January 19, 2013) was a German-American journalist and author. He was born in Hamburg, Germany, to a German mother and a Liberian father of Vai ethnicity, the grandson of Momulu Massaquoi, the cons ...

in his 1999 book '' Destined to Witness'' observed a human zoo within the Hamburg zoo Tierpark Hagenbeck

The Tierpark Hagenbeck is a zoo in Stellingen, Hamburg, Germany. The collection began in 1863 with animals that belonged to Carl Hagenbeck Sr. (1810–1887), a fishmonger who became an amateur animal collector. The park itself was founded by Ca ...

during the pre-Nazi Germany period, in which an African family was placed with the animals, openly laughed at, and otherwise treated rudely by the public crowd. And then they turned upon him, a fellow spectator, due to his mixed appearance. The date, according to his book, was approximately 1930.

Exhibitions after 1940

As part of thePortuguese World Exhibition

The Portuguese World Exhibition () was held in Lisbon in 1940 to mark 800 years since the foundation of the country and 300 years since the restoration of independence from Spain.

The fair ran from 23 June to 2 December 1940, held on the Praça d ...

in 1940, members of a tribe from the Bissagos Islands of Guinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissau, officially the Republic of Guinea-Bissau, is a country in West Africa that covers with an estimated population of 2,026,778. It borders Senegal to Guinea-Bissau–Senegal border, its north and Guinea to Guinea–Guinea-Bissau b ...

were displayed on an island in a lake in the Lisbon Tropical Botanical Garden

The Lisbon Tropical Botanical Garden (''Jardim Botânico Tropical'') is located between the Jerónimos Monastery and the Belém Palace, the official residence of the Portuguese president, in Belém (Lisbon), Belém, a few kilometers to the west o ...

.

A Congolese village was displayed at the Brussels 1958 World's Fair. The Congolese on display were among 598 people—including 273 men, 128 women and 197 children, a total of 183 families. Eight-month-old baby Juste Bonaventure Langa died during Expo 58; he rests in the Tervuren cemetery. In mid-July the Congolese protested the condescending treatment they were receiving from spectators and demanded to be sent home, abruptly ending the exhibit and eliciting some sympathy from European newspapers.

In April 1994, an example of an Ivory Coast

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire and officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital city of Yamoussoukro is located in the centre of the country, while its largest List of ci ...

village was presented as part of an African safari in Port-Saint-Père

Port-Saint-Père (; ) is a commune in the Loire-Atlantique department in western France.

Geography

Port-Saint-Père is situated on the west bank of the Acheneau, northwest of the Lac de Grand-Lieu.

Population

Sights

* Planète Sauvage, sa ...

, near Nantes

Nantes (, ; ; or ; ) is a city in the Loire-Atlantique department of France on the Loire, from the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast. The city is the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, sixth largest in France, with a pop ...

, in France, later called Planète Sauvage.

In July 2005, the Augsburg Zoo

Augsburg Zoo is a zoo located in the city of Augsburg in Bavaria, Germany, and with over 600,000 visitors annually, the zoo belongs to the 20 largest Zoos in Germany.

Augsburg Zoo holds 1,600 animals belonging to 300 different species. Of those a ...

in Germany hosted an "African village" featuring African crafts and African cultural performances. The event was subject to widespread criticism. Defenders of the event argued that it was not racist since it did not involve exhibiting Africans in a debasing way, as had been done at zoos in the past. Critics argued that presenting African culture in the context of a zoo contributed to exoticizing and stereotyping Africans, thus laying the ground work for racial discrimination, and that solidarity and mutual understanding with African people were not primary aims of the event.

In August 2005, London Zoo

London Zoo, previously known as ZSL London Zoo or London Zoological Gardens and sometimes called Regent's Park Zoo, is the world's oldest scientific zoo. It was opened in London on 27 April 1828 and was originally intended to be used as a colle ...

displayed four human volunteers wearing fig leaves (and bathing suits) for four days.

In 2007, Adelaide Zoo

Adelaide Zoo is a zoo in Adelaide, Australia. It is the country's second oldest zoo (after Melbourne Zoo) opening in 1883, and is operated on a non-profit basis. It is located in the Adelaide Parklands, parklands just north of the Adelaide cit ...

ran a Human Zoo exhibition which consisted of a group of people who, as part of a study exercise, had applied to be housed in the former ape enclosure by day, but then returned home by night. The inhabitants took part in several exercises, and spectators were asked for donations towards a new ape enclosure.

In August 2014, as part of the Edinburgh International Festival

The Edinburgh International Festival is an annual arts festival in Edinburgh, Scotland, spread over the final three weeks in August. Notable figures from the international world of music (especially european classical music, classical music) and ...

, South African theatre-maker Brett Bailey's show ''Exhibit B'' was performed in the Playfair Library Hall, University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

; then in September at The Barbican

Barbican is a type of fortified building.

Barbican may also refer to:

* Barbican (drink), a brand of malt beverage in Saudi Arabia and the UAE

* Barbican Estate, a residential estate in London

** Barbican Centre, an arts centre in London

** Barb ...

in London. This explored the nature of Human Zoos and raised much controversy both amongst the performers and the audiences.

With a view to tackling the morality of Human Zoo exhibits, 2018 saw the poster exhibition, ''Putting People on Display'', tour Glasgow School of Art

The Glasgow School of Art (GSA; ) is a higher education art school based in Glasgow, Scotland, offering undergraduate degrees, post-graduate awards (both taught and research-led), and PhDs in architecture, fine art, and design. These are all awa ...

, the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

, the University of Stirling

The University of Stirling (abbreviated as Stir or Shruiglea, in post-nominals; ) is a public university in Stirling, Scotland, founded by a royal charter in 1967. It is located in the Central Belt of Scotland, built within the walled Airth ...

, the University of St Andrews

The University of St Andrews (, ; abbreviated as St And in post-nominals) is a public university in St Andrews, Scotland. It is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, oldest of the four ancient universities of Scotland and, f ...

and the University of Aberdeen

The University of Aberdeen (abbreviated ''Aberd.'' in List of post-nominal letters (United Kingdom), post-nominals; ) is a public university, public research university in Aberdeen, Scotland. It was founded in 1495 when William Elphinstone, Bis ...

. Additional posters were added to a selection from the French ACHAC's exhibition, ''Human Zoos: the Invention of the Savage'', in relation to the Scottish dimension in hosting such shows.

See also

*Abraham Ulrikab

Abraham Ulrikab (January 29, 1845 – January 13, 1881) was an Inuk from Hebron, Labrador, in the present-day province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, who – along with his family and four other Inuit – agreed to become the latest attract ...

– Inuk

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labr ...

man and his family

* Cultural appropriation

Cultural appropriation is the adoption of an element or elements of one culture or cultural identity, identity by members of another culture or identity in a manner perceived as inappropriate or unacknowledged. Such a controversy typically ari ...

* Living history museum

A living museum, also known as a living history museum, is a type of museum which recreates historical settings to simulate a past time period, providing visitors with an Experiential education, experiential Heritage interpretation, interpretatio ...

* Natural state

* Noble savage

In Western anthropology, Western philosophy, philosophy, and European literature, literature, the Myth of the Noble savage refers to a stock character who is uncorrupted by civilization. As such, the "noble" savage symbolizes the innate goodness a ...

* Orientalism

In art history, literature, and cultural studies, Orientalism is the imitation or depiction of aspects of the Eastern world (or "Orient") by writers, designers, and artists from the Western world. Orientalist painting, particularly of the Middle ...

* Othering

In philosophy, the Other is a fundamental concept referring to anyone or anything perceived as distinct or different from oneself. This distinction is crucial for understanding how individuals construct their own identities, as the encounter wit ...

* Primitivism

In the arts of the Western world, Primitivism is a mode of aesthetic idealization that means to recreate the experience of ''the primitive'' time, place, and person, either by emulation or by re-creation. In Western philosophy, Primitivism propo ...

* Racial fetishism

Concepts of race and sexuality have interacted in various ways in different historical contexts. While partially based on physical similarities within groups, race is understood by scientists to be a social construct rather than a biological re ...

* Reality television

Reality television is a genre of television programming that documents purportedly unscripted real-life situations, often starring ordinary people rather than professional actors. Reality television emerged as a distinct genre in the early 1990s ...

* Romantic racism

Romantic racism is a form of racism in which members of a dominant group project their fantasies onto members of oppressed groups. Scholarship has found this view, for example, in Norman Mailer,Breines, Wini (1992). ''Young, White, and Miserabl ...

* Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa was the invasion, conquest, and colonialism, colonisation of most of Africa by seven Western European powers driven by the Second Industrial Revolution during the late 19th century and early 20th century in the era of ...

* Wild man

The wild man, wild man of the woods, woodwose or wodewose is a mythical figure and motif that appears in the art and literature of medieval Europe, comparable to the satyr or faun type in classical mythology and to ''Silvanus (mythology), Silvanu ...

References

Films

* ''The Couple in the Cage''. 1997. Dir. Coco Fusco and Paula Eredia. 30 min. * Régis Warnier, the film ''Man to Man''. 2005. * "From Bella Coola to Berlin". 2006. Dir. Barbara Hager. 48 minutes. Broadcaster – Bravo! Canada. * "Indianer in Berlin: Hagenbeck's Volkerschau". 2006. Dir. Barbara Hager. BroadcasterDiscovery Germany Geschichte Channel. * Alexander C. T. Geppert, ''Fleeting Cities. Imperial Expositions in Fin-de-Siècle Europe'' (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010). * Sadiah Qureshi, ''Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain'' (2011). *Human zoos. The invention of the savage

, Dir. Pascal Blanchard, Gilles Boëtsch, Nanette Jacomijn Snoep – exhibition catalogue – Actes Sud (2011) * ''Sauvages. Au cœur des zoos humains'', Dir. Pascal Blanchard, Bruno Victor-Pujebet – 90 minutes – Bonne Pioche production & Archipel (2018)

''Human Zoos: America's Forgotten History of Scientific Racism''

Dir. John G. West (2019)

Bibliography

# Abbattista, Guido, ''Ethnic Expositions in Italy, 1880 to 1940. Humans on Exhibition'' (London-New York: Routledge, 2024) # Ankerl, Guy. ''Coexisting Contemporary Civilizations: Arabo-Muslim, Bharatai, Chinese, and Western, Geneva'', INU Press, 2000, . # Conklin, Alice L., and Ian Christopher Fletcher. ''European Imperialism, 1830–1930: Climax and Contradiction''. Boston, MA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 1999. # Dreesbach, Anne. ''Colonial Exhibition'Völkerschauen' and the Display of the 'Other'

', European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, 2012. # Grant, Kevin. ''A Civilised Savagery: Britain and the New Slaveries in Africa, 1884–1926''. New York; Oxfordshire, England: Routledge, 2005. # Lewis, R. Barry. ''Understanding humans : introduction to physical anthropology and archaeology.'' Belmont, Calif. Wadsworth Cengage Learning. 2010. # Oliveira, Cinthya

''Human Rights & Exhibitions, 1789–1989,''

''Journal of Museum Ethnography'', no. 29, 2016, pp. 71–94. # Penny, H. Glenn

''Objects of Culture : Ethnology and Ethnographic Museums in Imperial Germany''

The University of North Carolina Press, 2002. # Porter, Louis, Porter, A. N., and Louis, William Roger. ''The Oxford History of the British Empire''. Volume III, The Nineteenth Century. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999. Oxford History of the British Empire. Web. # Qureshi, Sadiah. ''Robert Gordon Latham, Displayed Peoples, and the Natural History of Race: 1854–1866,'' ''The Historical Journal'', vol. 54, no. 1, 2011, pp

143–166

# Rothfels, Nigel.

Savages and Beasts : The Birth of the Modern Zoo

', Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002. # Schofield, Hugh

Human Zoos: When Real People Were Exhibits

BBC News, 2011.

India Andaman Jarawa Tribe in 'Shocking' Tourist Video

BBC News, 2012.

External links

*Human Zoos. The Invention of the Savage

Human Zoos website

* ;

"On A Neglected Aspect Of Western Racism"

by Kurt Jonassohn, December 2000

''The Colonial Exposition of May 1931''

by

Michael Vann

Michael G. Vann (born June 19, 1967) is an American historian who serves as Professor of History at California State University, Sacramento. He teaches a range of world history courses, including 20th century world, Southeast Asia, imperialism, and ...

"Official site of the Adelaide Human Zoo"

* Qureshi, Sadiah (2004), 'Displaying Sara Baartman, the 'Hottentot Venus', ''History of Science'' 42:233–257. Available online a

Science History Publications

{{DEFAULTSORT:Human Zoo Anthropology Colonial exhibitions Ethnography Ethnological show business History of colonialism History by ethnic group Scientific racism Sideshow attractions White supremacy Zoos