Hulderick Zuinglius on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a Swiss

The

The

Huldrych Zwingli was born on 1 January 1484 in Wildhaus, in the

Huldrych Zwingli was born on 1 January 1484 in Wildhaus, in the

vol. 1

''Corpus Reformatorum'' vol. 88, ed. Emil Egli. Berlin: Schwetschke, 1905. *

Analecta Reformatoria: Dokumente und Abhandlungen zur Geschichte Zwinglis und seiner Zeit

', vol. 1, ed. Emil Egli. Zürich: Züricher and Furrer, 1899. * ''Huldreich Zwingli's Werke'', ed. Melchior Schuler and Johannes Schulthess, 1824ff.

vol. Ivol. IIvol. IIIvol. IVvol. Vvol. VI, 1vol. VI, 2vol. VIIvol. VIII

*

Der evangelische Glaube nach den Hauptschriften der Reformatoren

', ed. Paul Wernle. Tübingen: Mohr, 1918. *

Von Freiheit der Speisen, eine Reformationsschrift, 1522

', ed. Otto Walther. Halle: Niemeyer, 1900. See also the following English translations of selected works by Zwingli: *

The Christian Education of Youth

'. Collegeville: Thompson Bros., 1899. *

Selected Works of Huldreich Zwingli (1484–1531)

'. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1901. * ''The Latin Works and the Correspondence of Huldreich Zwingli, Together with Selections from his German Works''. *

Vol. 1, 1510–1522

New York: G.P. Putnam and Sons, 1912. *

Vol. 2

Philadelphia: Heidelberg Press, 1912. *

Vol. 3

Philadelphia: Heidelberg Press, 1912.

Biography of Anna Reinhard, wife of Zwingli

in ''Leben'' magazine from a seminary of the Reformed Church in the United States

Website of the Zwingli Association and ''Zwingliana'' journal

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Zwingli, Huldrych 1484 births 1531 deaths 16th-century Calvinist and Reformed theologians 16th-century Swiss Roman Catholic priests 16th-century Swiss writers Calvinist and Reformed writers Christian humanists Clergy from Zurich Critics of the Catholic Church History of Zurich People excommunicated by the Catholic Church People from Toggenburg Swiss Calvinist and Reformed theologians Swiss military personnel killed in action University of Vienna alumni Swiss military chaplains

Christian theologian

Christian theology is the theology – the systematic study of the divine and religion – of Christian belief and practice. It concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and of the New Testament, as well as on Christian tradit ...

, musician

A musician is someone who Composer, composes, Conducting, conducts, or Performing arts#Performers, performs music. According to the United States Employment Service, "musician" is a general Terminology, term used to designate a person who fol ...

, and leader of the Reformation in Switzerland

The Protestant Reformation in Switzerland was promoted initially by Huldrych Zwingli, who gained the support of the magistrate, Mark Reust, and the population of Zürich in the 1520s. It led to significant changes in civil life and state matte ...

. Born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system, he attended the University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (, ) is a public university, public research university in Vienna, Austria. Founded by Rudolf IV, Duke of Austria, Duke Rudolph IV in 1365, it is the oldest university in the German-speaking world and among the largest ...

and the University of Basel

The University of Basel (Latin: ''Universitas Basiliensis''; German: ''Universität Basel'') is a public research university in Basel, Switzerland. Founded on 4 April 1460, it is Switzerland's oldest university and among the world's oldest univ ...

, a scholarly center of Renaissance humanism. He continued his studies while he served as a pastor in Glarus

Glarus (; ; ; ; ) is the capital of the canton of Glarus in Switzerland. Since 1 January 2011, the municipality of Glarus incorporates the former municipalities of Ennenda, Netstal and Riedern.Einsiedeln

Einsiedeln () is a municipalities of Switzerland, municipality and Districts of Switzerland#Schwyz, district in the canton of Schwyz in Switzerland known for its monastery, the Benedictine Einsiedeln Abbey, established in the 10th century.

Histor ...

, where he was influenced by the writings of Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus ( ; ; 28 October c. 1466 – 12 July 1536), commonly known in English as Erasmus of Rotterdam or simply Erasmus, was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic priest and Catholic theology, theologian, educationalist ...

. During his tenures at Basel and Einsiedeln, Zwingli began to familiarize himself with many criticisms Christian institutions were facing regarding their reform guidance and garnered scripture which aimed to address such criticisms.

IIn 1519, Zwingli became the (people's priest) of the Grossmünster

The Grossmünster (; "great minster") is a Romanesque-style Protestant church in Zürich, Switzerland. It is one of the four major churches in the city (the others being the Fraumünster, Predigerkirche, and St. Peterskirche). Its congregation ...

in Zurich

Zurich (; ) is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich. , the municipality had 448,664 inhabitants. The ...

where he began to preach ideas on reform of the Catholic Church. In his first public controversy in 1522, he attacked the custom of fasting during Lent

Lent (, 'Fortieth') is the solemn Christianity, Christian religious moveable feast#Lent, observance in the liturgical year in preparation for Easter. It echoes the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring Temptation of Christ, t ...

. In his publications, he noted corruption in the ecclesiastical hierarchy, promoted clerical marriage

Clerical marriage is the practice of allowing Christian clergy (those who have already been ordained) to marry. This practice is distinct from allowing married persons to become clergy. Clerical marriage is admitted among Protestants, including bo ...

, and attacked the use of images in places of worship. Among his most notable contributions to the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

was his expository preaching

Expository preaching, also known as expositional preaching, is a form of preaching that details the meaning of a particular text or passage of Scripture. It explains what the Bible means by what it says. Exegesis is technical and grammatical ex ...

, starting in 1519, through the Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel of Matthew is the first book of the New Testament of the Bible and one of the three synoptic Gospels. It tells the story of who the author believes is Israel's messiah (Christ (title), Christ), Jesus, resurrection of Jesus, his res ...

, before eventually using Biblical exegesis

Biblical studies is the academic application of a set of diverse disciplines to the study of the Bible, with ''Bible'' referring to the books of the canonical Hebrew Bible in mainstream Jewish usage and the Christian Bible including the can ...

to go through the entire New Testament, a radical departure from the Catholic mass

The Mass is the central liturgical service of the Eucharist in the Catholic Church, in which bread and wine are consecrated and become the body and blood of Christ. As defined by the Church at the Council of Trent, in the Mass "the same Christ ...

. In 1525, he introduced a new communion liturgy to replace the Mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

. He also clashed with the Anabaptists

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek : 're-' and 'baptism'; , earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. The term (tra ...

, which resulted in their persecution. Historians have debated whether or not he turned Zurich into a theocracy.

The Reformation spread to other parts of the Swiss Confederation

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerlan ...

, but several cantons

A canton is a type of administrative division of a country. In general, cantons are relatively small in terms of area and population when compared with other administrative divisions such as counties, departments, or provinces. Internationally, th ...

resisted, preferring to remain Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

. Zwingli formed an alliance of Reformed cantons which divided the Confederation along religious lines. In 1529, a war was averted at the last moment between the two sides. Meanwhile, Zwingli's ideas came to the attention of Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

and other reformers. They met at the Marburg Colloquy

The Marburg Colloquy was a meeting at Marburg Castle, Marburg, Hesse, Germany, which attempted to solve a disputation between Martin Luther and Ulrich Zwingli over the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist. It took place between 1 October and ...

and agreed on many points of doctrine, but they could not reach an accord on the doctrine of the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist

The real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, sometimes shortened Real Presence'','' is the Christian doctrine that Jesus Christ is present in the Eucharist, not merely symbolically or metaphorically, but in a true, real and substantial way.

T ...

.

In 1531, Zwingli's alliance applied an unsuccessful food blockade on the Catholic cantons. The cantons responded with an attack at a moment when Zurich was ill-prepared, and Zwingli died on the battlefield. His legacy lives on in the confessions, liturgy, and church orders of the Reformed church

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyterian, ...

es of today.

Historical context

The

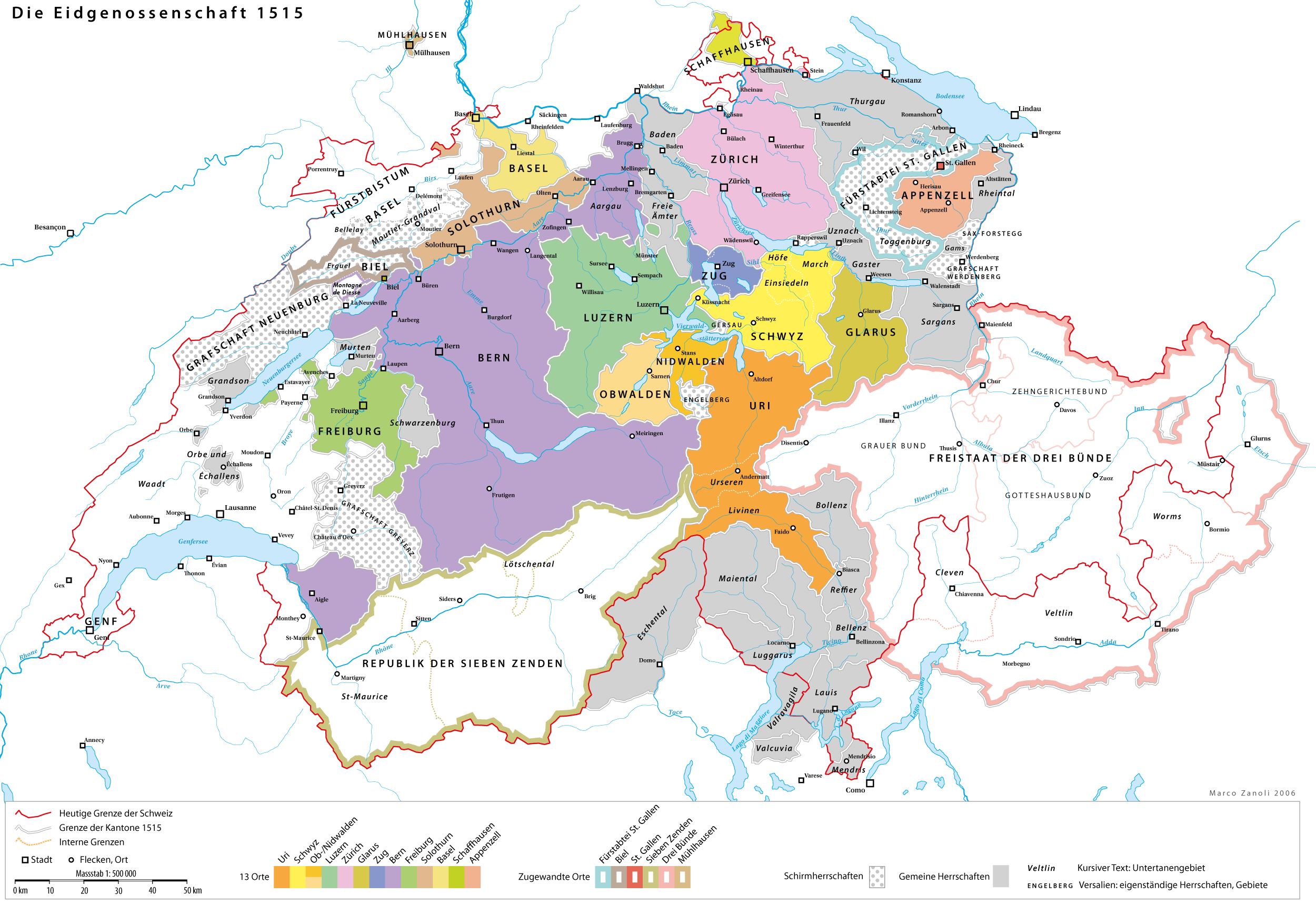

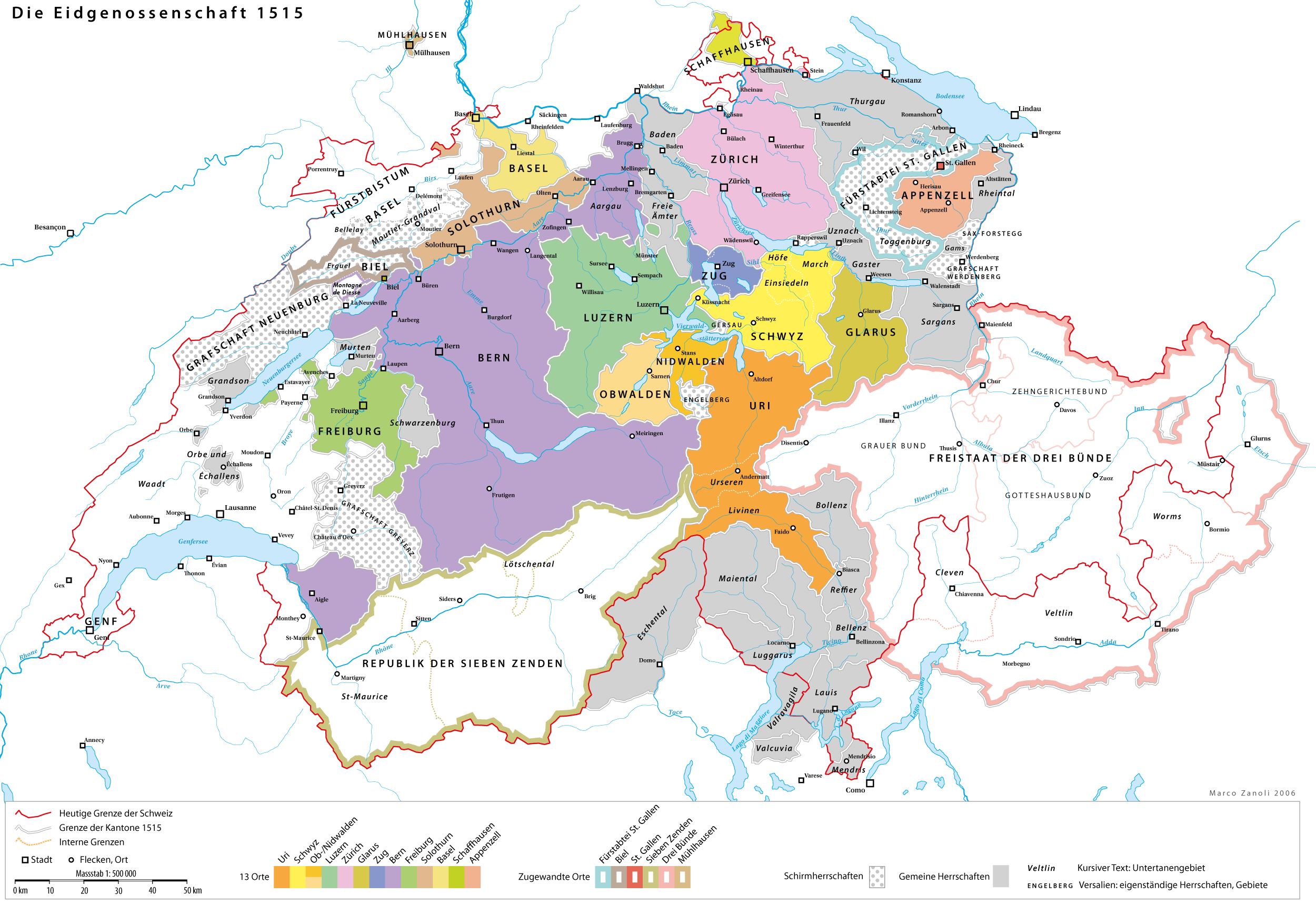

The Swiss Confederation

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerlan ...

in Huldrych Zwingli's time consisted of thirteen states (cantons

A canton is a type of administrative division of a country. In general, cantons are relatively small in terms of area and population when compared with other administrative divisions such as counties, departments, or provinces. Internationally, th ...

) as well as affiliated areas and common lordships. Unlike the modern state of Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

, which operates under a federal government, each of the thirteen cantons was nearly independent, conducting its own domestic and foreign affairs. Each canton formed its own alliances within and without the Confederation. This relative independence served as the basis for conflict during the time of the Reformation when the various cantons divided between different confessional camps. Military ambitions gained an additional impetus with the competition to acquire new territory and resources, as seen for example in the Old Zurich War of 1440–1446.

The wider political environment in Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries was also volatile. For centuries the relationship with the Confederation's powerful neighbour, France, determined the foreign policies of the Swiss. Nominally, the Confederation formed a part of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

. However, through a succession of wars culminating in the Swabian War

The Swabian War of 1499 ( (spelling depending on dialect), called or ("Swiss War") in Germany and ("War of the Engadin" in Austria) was the last major armed conflict between the Old Swiss Confederacy and the House of Habsburg. What had begun ...

in 1499, the Confederation had become ''de facto'' independent. As the two continental powers and minor regional states such as the Duchy of Milan

The Duchy of Milan (; ) was a state in Northern Italy, created in 1395 by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, then the lord of Milan, and a member of the important Visconti of Milan, Visconti family, which had been ruling the city since 1277. At that time, ...

, the Duchy of Savoy

The Duchy of Savoy (; ) was a territorial entity of the Savoyard state that existed from 1416 until 1847 and was a possession of the House of Savoy.

It was created when Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, raised the County of Savoy into a duchy f ...

, and the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

competed and fought against each other, there were far-reaching political, economic, and social consequences for the Confederation. During this time the mercenary pension system became a subject of disagreement. The religious factions of Zwingli's time debated vociferously the merits of sending young Swiss men to fight in foreign wars mainly for the enrichment of the cantonal authorities.

These internal and external factors contributed to the rise of a Confederation national consciousness, in which the term ''fatherland'' () began to take on meaning beyond a reference to an individual canton. At the same time, Renaissance humanism, with its universal values and emphasis on scholarship (as exemplified by Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus ( ; ; 28 October c. 1466 – 12 July 1536), commonly known in English as Erasmus of Rotterdam or simply Erasmus, was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic priest and Catholic theology, theologian, educationalist ...

(1466–1536), the "prince of humanism"), had taken root in the Confederation. Within this environment, defined by the confluence of Swiss patriotism

Patriotism is the feeling of love, devotion, and a sense of attachment to one's country or state. This attachment can be a combination of different feelings for things such as the language of one's homeland, and its ethnic, cultural, politic ...

and humanism, Zwingli was born in 1484.

Life

Early years (1484–1518)

Huldrych Zwingli was born on 1 January 1484 in Wildhaus, in the

Huldrych Zwingli was born on 1 January 1484 in Wildhaus, in the Toggenburg

Toggenburg is a region of Switzerland. It corresponds to the upper valley of the River Thur (Switzerland), Thur and that of the Necker (river), Necker, one of its afluents. Since 1 January 2003, Toggenburg has been a constituency (''Wahlkreis ...

valley of Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

, to a family of farmers, the third child of eleven. His father, Ulrich, played a leading role in the administration of the community (''Amtmann

__NOTOC__

The ''Amtmann'' or ''Ammann'' (in Switzerland) was an official in German-speaking countries of Europe and in some of the Nordic countries from the time of the Middle Ages whose office was akin to that of a bailiff

A bailiff is a ...

'' or chief local magistrate). Zwingli's primary schooling was provided by his uncle, Bartholomew, a cleric in Weesen, where he probably met Katharina von Zimmern

Katharina von Zimmern (1478 – 17 August 1547), also known as the imperial abbess of Zürich and Katharina von Reischach, was the last abbess of the Fraumünster Abbey in Zürich.

Early life

Katharina von Zimmern was born in 1478 in Mes ...

. At ten years old, Zwingli was sent to Basel

Basel ( ; ), also known as Basle ( ), ; ; ; . is a city in northwestern Switzerland on the river Rhine (at the transition from the High Rhine, High to the Upper Rhine). Basel is Switzerland's List of cities in Switzerland, third-most-populo ...

to obtain his secondary education where he learned Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

under Magistrate Gregory Bünzli. After three years in Basel, he stayed a short time in Bern

Bern (), or Berne (), ; ; ; . is the ''de facto'' Capital city, capital of Switzerland, referred to as the "federal city".; ; ; . According to the Swiss constitution, the Swiss Confederation intentionally has no "capital", but Bern has gov ...

with the humanist Henry Wölfflin. The Dominicans

Dominicans () also known as Quisqueyans () are an ethnic group, ethno-nationality, national people, a people of shared ancestry and culture, who have ancestral roots in the Dominican Republic.

The Dominican ethnic group was born out of a fusio ...

in Bern tried to persuade Zwingli to join their order and it is possible that he was received as a novice.

However, his father and uncle disapproved of such a course and he left Bern without completing his Latin studies. He enrolled in the University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (, ) is a public university, public research university in Vienna, Austria. Founded by Rudolf IV, Duke of Austria, Duke Rudolph IV in 1365, it is the oldest university in the German-speaking world and among the largest ...

in the winter semester of 1498 but was expelled, according to the university's records. However, it is not certain that Zwingli was indeed expelled, and he re-enrolled in the summer semester of 1500; his activities in 1499 are unknown. Zwingli continued his studies in Vienna until 1502, after which he transferred to the University of Basel

The University of Basel (Latin: ''Universitas Basiliensis''; German: ''Universität Basel'') is a public research university in Basel, Switzerland. Founded on 4 April 1460, it is Switzerland's oldest university and among the world's oldest univ ...

where he received the Master of Arts degree (''Magister'') in 1506. In Basel, one of Zwingli's teachers was Thomas Wyttenbach from Biel

Biel/Bienne (official bilingual wording; German language, German: ''Biel'' ; French language, French: ''Bienne'' ; Bernese German, locally ; ; ; ) is a bilingual city in the canton of Bern in Switzerland. With over 55,000 residents, it is the ...

, with whom he later corresponded on the doctrine of transubstantiation

Transubstantiation (; Greek language, Greek: μετουσίωσις ''metousiosis'') is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of sacramental bread, bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and ...

.

Zwingli was ordained in Constance

Constance may refer to:

Places

* Constance, Kentucky, United States, an unincorporated community

* Constance, Minnesota, United States, an unincorporated community

* Mount Constance, Washington State, United States

* Lake Constance (disambiguat ...

, the seat of the local diocese, by Bishop Hugo von Hohenlandenberg, and he celebrated his first Mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

in his hometown, Wildhaus, on 29 September 1506. As a young priest he had studied little theology, but this was not considered unusual at the time. His first ecclesiastical post was the pastorate of the town of Glarus

Glarus (; ; ; ; ) is the capital of the canton of Glarus in Switzerland. Since 1 January 2011, the municipality of Glarus incorporates the former municipalities of Ennenda, Netstal and Riedern.Roman See. In return,

On 1 January 1519, Zwingli gave his first sermon in Zurich. Deviating from the prevalent practice of basing a sermon on the Gospel lesson of a particular Sunday, Zwingli, using

On 1 January 1519, Zwingli gave his first sermon in Zurich. Deviating from the prevalent practice of basing a sermon on the Gospel lesson of a particular Sunday, Zwingli, using

In December 1523, the council set a deadline of

In December 1523, the council set a deadline of

On 8 April 1524, five cantons,

On 8 April 1524, five cantons,

Soon after the Austrian treaty was signed, a reformed preacher, Jacob Kaiser, was captured in

Soon after the Austrian treaty was signed, a reformed preacher, Jacob Kaiser, was captured in

With the failure of the Marburg Colloquy and the split of the Confederation, Zwingli set his goal on an alliance with Philip of Hesse. He kept up a lively correspondence with Philip. Bern refused to participate, but after a long process, Zurich, Basel, and Strasbourg signed a mutual defence treaty with Philip in November 1530. Zwingli also personally negotiated with France's diplomatic representative, but the two sides were too far apart. France wanted to maintain good relations with the Five States. Approaches to Venice and Milan also failed.

As Zwingli was working on establishing these political alliances,

With the failure of the Marburg Colloquy and the split of the Confederation, Zwingli set his goal on an alliance with Philip of Hesse. He kept up a lively correspondence with Philip. Bern refused to participate, but after a long process, Zurich, Basel, and Strasbourg signed a mutual defence treaty with Philip in November 1530. Zwingli also personally negotiated with France's diplomatic representative, but the two sides were too far apart. France wanted to maintain good relations with the Five States. Approaches to Venice and Milan also failed.

As Zwingli was working on establishing these political alliances,

Zwingli rejected the word ''sacrament'' in the popular usage of his time. For ordinary people, the word meant some kind of holy action of which there is inherent power to free the conscience from sin. For Zwingli, a sacrament was an initiatory ceremony or a pledge, pointing out that the word was derived from ''sacramentum'' meaning an oath. (However, the word is also translated "mystery".) In his early writings on baptism, he noted that baptism was an example of such a pledge. He challenged Catholics by accusing them of superstition when they ascribed the water of baptism a certain power to wash away sin. Later, in his conflict with the Anabaptists, he defended the practice of infant baptism, noting that there is no law forbidding the practice. He argued that baptism was a sign of a covenant with God, thereby replacing circumcision in the Old Testament.

Zwingli approached the Eucharist in a similar manner to baptism. During the first Zurich disputation in 1523, he denied that an actual sacrifice occurred during the Mass, arguing that Christ made the sacrifice only once and for all eternity. Hence, the Eucharist was "a memorial of the sacrifice". Following this argument, he further developed his view, coming to the conclusion of the "signifies" interpretation for the words of the institution. He used various passages of scripture to argue against

Zwingli rejected the word ''sacrament'' in the popular usage of his time. For ordinary people, the word meant some kind of holy action of which there is inherent power to free the conscience from sin. For Zwingli, a sacrament was an initiatory ceremony or a pledge, pointing out that the word was derived from ''sacramentum'' meaning an oath. (However, the word is also translated "mystery".) In his early writings on baptism, he noted that baptism was an example of such a pledge. He challenged Catholics by accusing them of superstition when they ascribed the water of baptism a certain power to wash away sin. Later, in his conflict with the Anabaptists, he defended the practice of infant baptism, noting that there is no law forbidding the practice. He argued that baptism was a sign of a covenant with God, thereby replacing circumcision in the Old Testament.

Zwingli approached the Eucharist in a similar manner to baptism. During the first Zurich disputation in 1523, he denied that an actual sacrifice occurred during the Mass, arguing that Christ made the sacrifice only once and for all eternity. Hence, the Eucharist was "a memorial of the sacrifice". Following this argument, he further developed his view, coming to the conclusion of the "signifies" interpretation for the words of the institution. He used various passages of scripture to argue against

Zwingli criticized the practice of priestly chanting and monastic choirs. The criticism dates from 1523 when he attacked certain worship practices. His arguments are detailed in the Conclusions of 1525, in which, Conclusions 44, 45 and 46 are concerned with musical practices under the rubric of "prayer". He associated music with images and vestments, all of which he felt diverted people's attention from true spiritual worship. It is not known what he thought of the musical practices in early Lutheran churches. Zwingli, however, eliminated instrumental music from worship in the church, stating that God had not commanded it in worship. The organist of the People's Church in Zurich is recorded as weeping upon seeing the great organ broken up.Chadwick, Owen, ''The Reformation'', Penguin, 1990, p. 439 Although Zwingli did not express an opinion on congregational singing, he made no effort to encourage it. Nevertheless, scholars have found that Zwingli was supportive of a role for music in the church. Gottfried W. Locher writes, "The old assertion 'Zwingli was against church singing' holds good no longer ... Zwingli's polemic is concerned exclusively with the medieval Latin choral and priestly chanting and not with the hymns of evangelical congregations or choirs". Locher goes on to say that "Zwingli freely allowed vernacular psalm or choral singing. In addition, he even seems to have striven for lively, antiphonal, unison recitative". Locher then summarizes his comments on Zwingli's view of church music as follows: "The chief thought in his conception of worship was always 'conscious attendance and understanding'—'devotion', yet with the lively participation of all concerned".

Zwingli criticized the practice of priestly chanting and monastic choirs. The criticism dates from 1523 when he attacked certain worship practices. His arguments are detailed in the Conclusions of 1525, in which, Conclusions 44, 45 and 46 are concerned with musical practices under the rubric of "prayer". He associated music with images and vestments, all of which he felt diverted people's attention from true spiritual worship. It is not known what he thought of the musical practices in early Lutheran churches. Zwingli, however, eliminated instrumental music from worship in the church, stating that God had not commanded it in worship. The organist of the People's Church in Zurich is recorded as weeping upon seeing the great organ broken up.Chadwick, Owen, ''The Reformation'', Penguin, 1990, p. 439 Although Zwingli did not express an opinion on congregational singing, he made no effort to encourage it. Nevertheless, scholars have found that Zwingli was supportive of a role for music in the church. Gottfried W. Locher writes, "The old assertion 'Zwingli was against church singing' holds good no longer ... Zwingli's polemic is concerned exclusively with the medieval Latin choral and priestly chanting and not with the hymns of evangelical congregations or choirs". Locher goes on to say that "Zwingli freely allowed vernacular psalm or choral singing. In addition, he even seems to have striven for lively, antiphonal, unison recitative". Locher then summarizes his comments on Zwingli's view of church music as follows: "The chief thought in his conception of worship was always 'conscious attendance and understanding'—'devotion', yet with the lively participation of all concerned".

Scholars have found it difficult to assess Zwingli's impact on history, for several reasons. There is no consensus on the definition of " Zwinglianism"; by any definition, Zwinglianism evolved under his successor, Heinrich Bullinger; and research into Zwingli's influence on Bullinger and

Scholars have found it difficult to assess Zwingli's impact on history, for several reasons. There is no consensus on the definition of " Zwinglianism"; by any definition, Zwinglianism evolved under his successor, Heinrich Bullinger; and research into Zwingli's influence on Bullinger and

"

** ''Wer Ursache zum Aufruhr gibt'' (1524) "Those Who Give Cause for Tumult"

* Volume 2: 1995, 556 pages,

** ''Auslegung und Begründung der Thesen oder Artikel'' (1523) "Interpretation and justification of the theses or articles"

* Volume 3: 1995, 519 pages,

** ''Empfehlung zur Vorbereitung auf einen möglichen Krieg'' (1524) "Plan for a Campaign"

** ''Kommentar über die wahre und die falsche Religion'' (1525) "Commentary on True and False Religion"

* Volume 4: 1995, 512 pages,

** ''Antwort auf die Predigt Luthers gegen die Schwärmer'' (1527) "A Refutation of Luther's sermon against vain enthusiasm"

** ''Die beiden Berner Predigten'' (1528) "The Berne sermons"

** ''Rechenschaft über den Glauben'' (1530) "An Exposition of the Faith"

** ''Die Vorsehung'' (1530) "Providence"

** ''Erklärung des christlichen Glaubens'' (1531) "Explanation of the Christian faith"

The complete 21-volume edition is being undertaken by the ''Zwingliverein'' in collaboration with the ''Institut für schweizerische Reformationsgeschichte'', and is projected to be organised as follows:

* vols. I–VI ''Werke'': Zwingli's theological and political writings, essays, sermons etc., in chronological order. This section was completed in 1991.

* vols. VII–XI ''Briefe'': Letters

* vol. XII ''Randglossen'': Zwingli's glosses in the margin of books

* vols XIII ff. ''Exegetische Schriften'': Zwingli's exegetical notes on the Bible.

Vols. XIII and XIV have been published, vols. XV and XVI are under preparation. Vols. XVII to XXI are planned to cover the New Testament.

Older German / Latin editions available online include:

* ''Huldreich Zwinglis sämtliche Werke''Pope Julius II

Pope Julius II (; ; born Giuliano della Rovere; 5 December 144321 February 1513) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1503 to his death, in February 1513. Nicknamed the Warrior Pope, the Battle Pope or the Fearsome ...

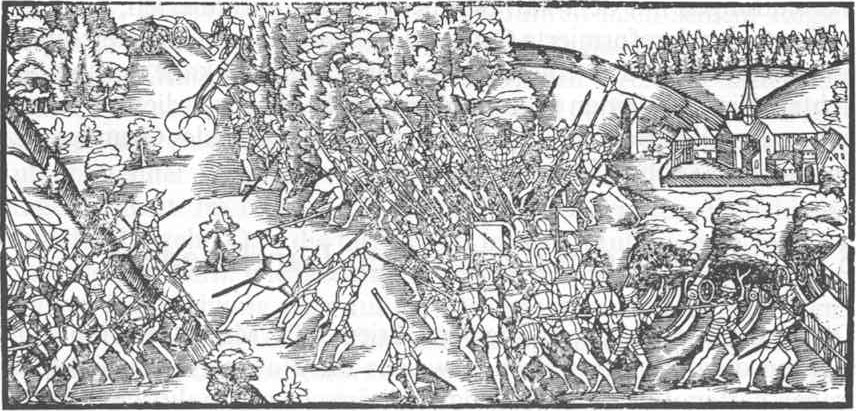

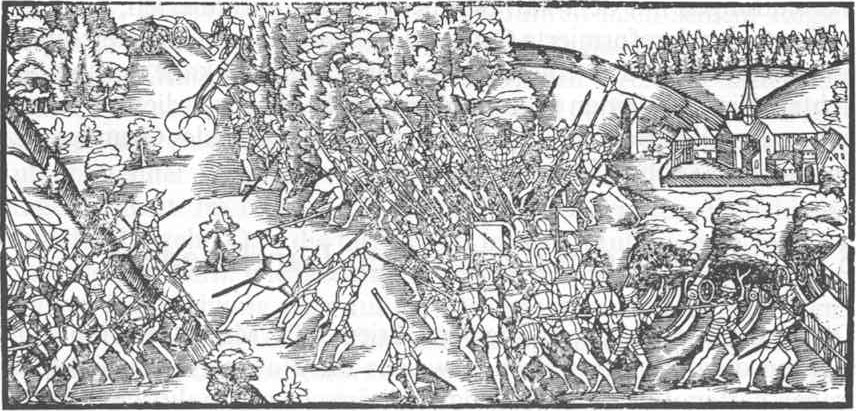

honoured Zwingli by providing him with an annual pension. He took the role of chaplain in several campaigns in Italy, including the Battle of Novara in 1513.

However, the decisive defeat of the Swiss in the Battle of Marignano

The Battle of Marignano, which took place on 13–14 September 1515, near the town now called Melegnano, 16 km southeast of Milan, was the last major engagement of the War of the League of Cambrai. It pitted the French army, composed of t ...

caused a shift in mood in Glarus in favour of the French rather than the pope. Zwingli, the papal partisan, found himself in a difficult position and he decided to retreat to Einsiedeln

Einsiedeln () is a municipalities of Switzerland, municipality and Districts of Switzerland#Schwyz, district in the canton of Schwyz in Switzerland known for its monastery, the Benedictine Einsiedeln Abbey, established in the 10th century.

Histor ...

in the canton of Schwyz

The canton of Schwyz ( ; ; ; ) is a Cantons of Switzerland, canton in central Switzerland between the Swiss Alps, Alps in the south, Lake Lucerne to the west and Lake Zürich in the north, centred on and named after the town of Schwyz.

It is one ...

. By this time, he had become convinced that mercenary service was immoral and that Swiss unity was indispensable for any future achievements. Some of his earliest extant writings, such as ''The Ox'' (1510) and ''The Labyrinth'' (1516), attacked the mercenary system using allegory and satire. His countrymen were presented as virtuous people within a French, imperial, and papal triangle.

Zwingli stayed in Einsiedeln for two years during which he withdrew completely from politics in favour of ecclesiastical activities and personal studies. His time as pastor of Glarus and Einsiedeln was characterized by inner growth and development. He perfected his Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

and he took up the study of Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

. His library contained over three hundred volumes from which he was able to draw upon classical, patristic

Patristics, also known as Patrology, is a branch of theological studies focused on the writings and teachings of the Church Fathers, between the 1st to 8th centuries CE. Scholars analyze texts from both orthodox and heretical authors. Patristics em ...

, and scholastic works. He exchanged scholarly letters with a circle of Swiss humanists and began to study the writings of Erasmus. He continued his studies while he served as a pastor in Glarus and later in Einsiedeln, where he was influenced by the writings of Erasmus. Zwingli took the opportunity to meet him while Erasmus was in Basel between August 1514 and May 1516. Zwingli's turn to relative pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ...

and his focus on preaching can be traced to the influence of Erasmus.

In late 1518, the post of the ''Leutpriestertum'' (people's priest) of the Grossmünster

The Grossmünster (; "great minster") is a Romanesque-style Protestant church in Zürich, Switzerland. It is one of the four major churches in the city (the others being the Fraumünster, Predigerkirche, and St. Peterskirche). Its congregation ...

at Zurich

Zurich (; ) is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich. , the municipality had 448,664 inhabitants. The ...

became vacant. The canons of the foundation that administered the Grossmünster recognised Zwingli's reputation as a fine preacher and writer. His connection with humanists was a decisive factor as several canons were sympathetic to Erasmian reform. In addition, his opposition to the French and to mercenary service was welcomed by Zurich politicians. On 11 December 1518, the canons elected Zwingli to become the stipendiary priest and on 27 December he moved permanently to Zurich.

Beginning of Zurich ministry (1519–1521)

On 1 January 1519, Zwingli gave his first sermon in Zurich. Deviating from the prevalent practice of basing a sermon on the Gospel lesson of a particular Sunday, Zwingli, using

On 1 January 1519, Zwingli gave his first sermon in Zurich. Deviating from the prevalent practice of basing a sermon on the Gospel lesson of a particular Sunday, Zwingli, using Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus ( ; ; 28 October c. 1466 – 12 July 1536), commonly known in English as Erasmus of Rotterdam or simply Erasmus, was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic priest and Catholic theology, theologian, educationalist ...

' New Testament as a guide, began to read through the Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel of Matthew is the first book of the New Testament of the Bible and one of the three synoptic Gospels. It tells the story of who the author believes is Israel's messiah (Christ (title), Christ), Jesus, resurrection of Jesus, his res ...

, giving his interpretation during the sermon, known as the method of '' lectio continua''. He continued to read and interpret the book on subsequent Sundays until he reached the end and then proceeded in the same manner with the Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles (, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; ) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of The gospel, its message to the Roman Empire.

Acts and the Gospel of Luke make u ...

, the New Testament epistles

An epistle (; ) is a writing directed or sent to a person or group of people, usually an elegant and formal didactic letter. The epistle genre of letter-writing was common in ancient Egypt as part of the scribal-school writing curriculum. The ...

, and finally the Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

. His motives for doing this are not clear, but in his sermons he used exhortation to achieve moral and ecclesiastical improvement which were goals comparable with Erasmian reform. Sometime after 1520, Zwingli's theological model began to evolve into an idiosyncratic form that was neither Erasmian nor Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

. Scholars do not agree on the process of how he developed his own unique model. One view is that Zwingli was trained as an Erasmian humanist and Luther played a decisive role in changing his theology.

Another view is that Zwingli did not pay much attention to Luther's theology and in fact he considered it as part of the humanist reform movement. A third view is that Zwingli was not a complete follower of Erasmus, but had diverged from him as early as 1516 and that he independently developed his theology.

Zwingli's theological stance was gradually revealed through his sermons. He attacked moral corruption and in the process he named individuals who were the targets of his denunciations. Monks were accused of indolence and high living. In 1519, Zwingli specifically rejected the veneration

Veneration (; ), or veneration of saints, is the act of honoring a saint, a person who has been identified as having a high degree of sanctity or holiness. Angels are shown similar veneration in many religions. Veneration of saints is practiced, ...

of saints and called for the need to distinguish between their true and fictional accounts. He cast doubts on hellfire, asserted that unbaptised children were not damned, and questioned the power of excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to deprive, suspend, or limit membership in a religious community or to restrict certain rights within it, in particular those of being in Koinonia, communion with other members o ...

. His attack on the claim that tithing

A tithing or tything was a historic English legal, administrative or territorial unit, originally ten hides (and hence, one tenth of a hundred). Tithings later came to be seen as subdivisions of a manor or civil parish. The tithing's leader or ...

was a divine institution, however, had the greatest theological and social impact. This contradicted the immediate economic interests of the foundation. One of the elderly canons who had supported Zwingli's election, Konrad Hofmann, complained about his sermons in a letter. Some canons supported Hofmann, but the opposition never grew very large. Zwingli insisted that he was not an innovator and that the sole basis of his teachings was Scripture.

Within the diocese of Constance

The Prince-Bishopric of Constance () was a small ecclesiastical principality of the Holy Roman Empire from the mid-12th century until its secularisation in 1802–1803. In his dual capacity as prince and as bishop, the prince-bishop also admini ...

, Bernhardin Sanson was offering a special indulgence

In the teaching of the Catholic Church, an indulgence (, from , 'permit') is "a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo for (forgiven) sins". The ''Catechism of the Catholic Church'' describes an indulgence as "a remission bef ...

for contributors to the building of St Peter's in Rome. When Sanson arrived at the gates of Zurich at the end of January 1519, parishioners prompted Zwingli with questions. He responded with displeasure that the people were not being properly informed about the conditions of the indulgence and were being induced to part with their money on false pretences. This was over a year after Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

published his Ninety-five theses (31 October 1517). The council of Zurich refused Sanson entry into the city. As the authorities in Rome were anxious to contain the fire started by Luther, the Bishop of Constance denied any support of Sanson and he was recalled.

In August 1519, Zurich was struck by an outbreak of the plague during which at least one in four persons died. All of those who could afford it left the city, but Zwingli remained and continued his pastoral duties. In September, he caught the disease and nearly died. He described his preparation for death in a poem, Zwingli's ''Pestlied'', consisting of three parts: the onset of the illness, the closeness to death, and the joy of recovery. The final verses of the first part read:

In the years following his recovery, Zwingli's opponents remained in the minority. When a vacancy occurred among the canons of the Grossmünster, Zwingli was elected to fulfill that vacancy on 29 April 1521. In becoming a canon, he became a full citizen of Zurich. He also retained his post as the people's priest of the Grossmünster.

First rifts (1522–1524)

The first public controversy regarding Zwingli's preaching broke out during the season ofLent

Lent (, 'Fortieth') is the solemn Christianity, Christian religious moveable feast#Lent, observance in the liturgical year in preparation for Easter. It echoes the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring Temptation of Christ, t ...

in 1522. On the first fasting Sunday, 9 March, Zwingli and about a dozen other participants consciously transgressed the fasting rule by cutting and distributing two smoked sausages (the ''Wurstessen'' in Christoph Froschauer's workshop). Zwingli defended this act in a sermon which was published on 16 April, under the title ''Von Erkiesen und Freiheit der Speisen'' (Regarding the Choice and Freedom of Foods). He noted that no general valid rule on food can be derived from the Bible and that to transgress such a rule is not a sin. The event, which came to be referred to as the Affair of the Sausages

The Affair of the Sausages (1522) was the event that sparked the Reformation in Zürich. Huldrych Zwingli, pastor of Grossmünster in Zurich, Switzerland, spearheaded the event by publicly speaking in favor of eating sausage during the Lenten fast ...

, is considered to be the start of the Reformation in Switzerland.

Even before the publication of this treatise, the diocese of Constance reacted by sending a delegation to Zurich. The city council condemned the fasting violation, but assumed responsibility over ecclesiastical matters and requested the religious authorities clarify the issue. The bishop responded on 24 May by admonishing the Grossmünster and city council and repeating the traditional position.

Following this event, Zwingli and other humanist friends petitioned the bishop on 2 July to abolish the requirement of celibacy on the clergy. Two weeks later the petition was reprinted for the public in German as ''Eine freundliche Bitte und Ermahnung an die Eidgenossen'' (A Friendly Petition and Admonition to the Confederates). The issue was not just an abstract problem for Zwingli, as he had secretly married a widow, Anna Reinhart, earlier in the year. Their cohabitation was well-known and their public wedding took place on 2 April 1524, three months before the birth of their first child. They would have four children: Regula, William, Huldrych, and Anna. As the petition was addressed to the secular authorities, the bishop responded at the same level by notifying the Zurich government to maintain the ecclesiastical order. Other Swiss clergymen joined in Zwingli's cause which encouraged him to make his first major statement of faith, ''Apologeticus Archeteles'' (The First and Last Word). He defended himself against charges of inciting unrest and heresy. He denied the ecclesiastical hierarchy any right to judge on matters of church order because of its corrupted state.

Zurich disputations (1523)

The events of 1522 brought no clarification on the issues. Not only did the unrest between Zurich and the bishop continue, tensions were growing among Zurich's Confederation partners in theSwiss Diet

The Federal Diet of Switzerland (, ; ; ) was the legislative and executive council of the Old Swiss Confederacy and existed in various forms from the beginnings of Swiss independence until the formation of the Switzerland as a federal state, ...

. On 22 December, the Diet recommended that its members prohibit the new teachings, a strong indictment directed at Zurich. The city council felt obliged to take the initiative and find its own solution.

First Disputation

On 3 January 1523, the Zurich city council invited the clergy of the city and outlying region to a meeting to allow the factions to present their opinions. The bishop was invited to attend or to send a representative. The council would render a decision on who would be allowed to continue to proclaim their views. This meeting, the first Zurich disputation, took place on 29 January 1523. The meeting attracted a large crowd of approximately six hundred participants. The bishop sent a delegation led by hisvicar general

A vicar general (previously, archdeacon) is the principal deputy of the bishop or archbishop of a diocese or an archdiocese for the exercise of administrative authority and possesses the title of local ordinary. As vicar of the bishop, the vica ...

, Johannes Fabri. Zwingli summarised his position in the ''Schlussreden'' (Concluding Statements or the Sixty-seven Articles). Fabri, who had not envisaged an academic disputation in the manner Zwingli had prepared for, was forbidden to discuss high theology before laymen, and simply insisted on the necessity of the ecclesiastical authority. The decision of the council was that Zwingli would be allowed to continue his preaching and that all other preachers should teach only in accordance with Scripture.

Second Disputation

In September 1523,Leo Jud

Leo Jud (; also Leo Juda, Leo Judä, Leo Judas, Leonis Judae, Ionnes Iuda, Leo Keller; 1482 – 19 June 1542), known to his contemporaries as Meister Leu, was a Swiss reformer who worked with Huldrych Zwingli in Zürich.

Biography

Jud was bor ...

, Zwingli's closest friend and colleague and pastor of St Peterskirche, publicly called for the removal of statues of saints and other icons. This led to demonstrations and iconoclastic

Iconoclasm ()From . ''Iconoclasm'' may also be considered as a back-formation from ''iconoclast'' (Greek: εἰκοκλάστης). The corresponding Greek word for iconoclasm is εἰκονοκλασία, ''eikonoklasia''. is the social belie ...

activities. The city council decided to work out the matter of images in a second disputation. The essence of the Mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

and its sacrificial character was also included as a subject of discussion. Supporters of the Mass claimed that the Eucharist was a true sacrifice, while Zwingli claimed that it was a commemorative meal. As in the first disputation, an invitation was sent out to the Zurich clergy and the bishop of Constance. This time, however, the lay people of Zurich, the dioceses of Chur

''

Chur (locally) or ; ; ; ; ; ; or ; , and . is the capital and largest List of towns in Switzerland, town of the Switzerland, Swiss Cantons of Switzerland, canton of the Grisons and lies in the Alpine Rhine, Grisonian Rhine Valley, where ...

and Basel, the University of Basel, and the twelve members of the Confederation were also invited. About nine hundred persons attended this meeting, but neither the bishop nor the Confederation sent representatives. The disputation started on 26 October 1523 and lasted two days.

Zwingli again took the lead in the disputation. His opponent was the aforementioned canon, Konrad Hofmann, who had initially supported Zwingli's election. Also taking part was a group of young men demanding a much faster pace of reformation, who among other things pleaded for replacing infant baptism

Infant baptism, also known as christening or paedobaptism, is a Christian sacramental practice of Baptism, baptizing infants and young children. Such practice is done in the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches, va ...

with adult baptism

Believer's baptism (also called credobaptism, from the Latin word meaning "I believe") is the practice of baptizing those who are able to make a conscious profession of faith, as contrasted to the practice of baptizing infants. Credobaptists b ...

. This group was led by Conrad Grebel

Conrad Grebel ( – 1526) was a co-founder of the Swiss Brethren movement.

Early life

Conrad Grebel was born, probably in Grüningen in the canton of Zürich, about 1498 to Junker Jakob and Dorothea (Fries) Grebel, the second of six children ...

, one of the initiators of the Anabaptist

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek language, Greek : 're-' and 'baptism'; , earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

movement. During the first three days of dispute, although the controversy of images and the mass were discussed, the arguments led to the question of whether the city council or the ecclesiastical government had the authority to decide on these issues.

At this point, Konrad Schmid, a priest from Aargau

Aargau ( ; ), more formally the Canton of Aargau (; ; ; ), is one of the Canton of Switzerland, 26 cantons forming the Switzerland, Swiss Confederation. It is composed of eleven districts and its capital is Aarau.

Aargau is one of the most nort ...

and follower of Zwingli, made a pragmatic suggestion. As images were not yet considered to be valueless by everyone, he suggested that pastors preach on this subject under threat of punishment. He believed the opinions of the people would gradually change and the voluntary removal of images would follow. Hence, Schmid rejected the radicals and their iconoclasm, but supported Zwingli's position. In November the council passed ordinances in support of Schmid's motion. Zwingli wrote a booklet on the evangelical duties of a minister, ''Kurze, christliche Einleitung'' (Short Christian Introduction), and the council sent it out to the clergy and the members of the Confederation.

Reformation progresses in Zurich (1524–1525)

Huldrych Zwingli was a major figure in theSwiss Reformation

The Protestant Reformation in Switzerland was promoted initially by Huldrych Zwingli, who gained the support of the magistrate, Mark Reust, and the population of Zürich in the 1520s. It led to significant changes in civil life and state matte ...

, advocating for the authority of scripture and the rejection of religious practices not supported by the Bible. His preaching and teachings helped spread Reformation ideas beyond Switzerland and influenced the development of Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

throughout Europe. In December 1523, the council set a deadline of

In December 1523, the council set a deadline of Pentecost

Pentecost (also called Whit Sunday, Whitsunday or Whitsun) is a Christianity, Christian holiday which takes place on the 49th day (50th day when inclusive counting is used) after Easter Day, Easter. It commemorates the descent of the Holy Spiri ...

in 1524 for a solution to the elimination of the Mass and images. Zwingli gave a formal opinion in ''Vorschlag wegen der Bilder und der Messe'' (Proposal Concerning Images and the Mass). He did not urge an immediate, general abolition. The council decided on the orderly removal of images within Zurich, but rural congregations were granted the right to remove them based on majority vote. The decision on the Mass was postponed.

Evidence of the effect of the Reformation was seen in early 1524. Candlemas

Candlemas, also known as the Feast of the Presentation of Jesus Christ, the Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary, or the Feast of the Holy Encounter, is a Christian holiday, Christian feast day commemorating the presentation of ...

was not celebrated, processions of robed clergy ceased, worshippers did not go with palms or relics on Palm Sunday

Palm Sunday is the Christian moveable feast that falls on the Sunday before Easter. The feast commemorates Christ's triumphal entry into Jerusalem, an event mentioned in each of the four canonical Gospels. Its name originates from the palm bran ...

to the Lindenhof, and triptych

A triptych ( ) is a work of art (usually a panel painting) that is divided into three sections, or three carved panels that are hinged together and can be folded shut or displayed open. It is therefore a type of polyptych, the term for all m ...

s remained covered and closed after Lent

Lent (, 'Fortieth') is the solemn Christianity, Christian religious moveable feast#Lent, observance in the liturgical year in preparation for Easter. It echoes the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring Temptation of Christ, t ...

. Opposition to the changes came from Konrad Hofmann and his followers, but the council decided in favour of keeping the government mandates. When Hofmann left the city, opposition from pastors hostile to the Reformation broke down. The bishop of Constance tried to intervene in defending the Mass and the veneration of images. Zwingli wrote an official response for the council and the result was the severance of all ties between the city and the diocese.

Although the council had hesitated in abolishing the Mass, the decrease in the exercise of traditional piety allowed pastors to be unofficially released from the requirement of celebrating Mass. As individual pastors altered their practices as each saw fit, Zwingli was prompted to address this disorganised situation by designing a communion liturgy in the German language. This was published in ''Aktion oder Brauch des Nachtmahls'' (Act or Custom of the Supper). Shortly before Easter

Easter, also called Pascha ( Aramaic: פַּסְחָא , ''paskha''; Greek: πάσχα, ''páskha'') or Resurrection Sunday, is a Christian festival and cultural holiday commemorating the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, described in t ...

, Zwingli and his closest associates requested the council to cancel the Mass and to introduce the new public order of worship.

On Maundy Thursday

Maundy Thursday, also referred to as Holy Thursday, or Thursday of the Lord's Supper, among other names,The day is also known as Great and Holy Thursday, Holy and Great Thursday, Covenant Thursday, Sheer Thursday, and Thursday of Mysteries. is ...

, 13 April 1525, Zwingli celebrated communion under his new liturgy. Wooden cups and plates were used to avoid any outward displays of formality. The congregation sat at set tables to emphasise the meal aspect of the sacrament. The sermon was the focal point of the service and there was no organ music or singing. The importance of the sermon in the worship service was underlined by Zwingli's proposal to limit the celebration of communion to four times a year.

For some time Zwingli had accused mendicant

A mendicant (from , "begging") is one who practices mendicancy, relying chiefly or exclusively on alms to survive. In principle, Mendicant orders, mendicant religious orders own little property, either individually or collectively, and in many i ...

orders of hypocrisy and demanded their abolition in order to support the truly poor. He suggested the monasteries be changed into hospitals and welfare institutions and incorporate their wealth into a welfare fund. This was done by reorganising the foundations of the Grossmünster and Fraumünster

The Fraumünster (; lit. in ) is a church in Zürich which was built on the remains of a former abbey for aristocratic women which was founded in 853 by Louis the German for his daughter Hildegard. He endowed the Benedictine convent with the l ...

and pensioning off remaining nuns and monks. The council secularised the church properties (Fraumünster handed over to the city of Zurich by Zwingli's acquaintance Katharina von Zimmern

Katharina von Zimmern (1478 – 17 August 1547), also known as the imperial abbess of Zürich and Katharina von Reischach, was the last abbess of the Fraumünster Abbey in Zürich.

Early life

Katharina von Zimmern was born in 1478 in Mes ...

in 1524) and established new welfare programs for the poor.

Zwingli requested permission to establish a Latin school, the ''Prophezei'' (Prophecy) or ''Carolinum'', at the Grossmünster. The council agreed and it was officially opened on 19 June 1525 with Zwingli and Jud as teachers. It served to retrain and re-educate the clergy. The Zurich Bible translation, traditionally attributed to Zwingli and printed by Christoph Froschauer, bears the mark of teamwork from the Prophecy school. Scholars have not yet attempted to clarify Zwingli's share of the work based on external and stylistic evidence.

Conflict with the Anabaptists (1525–1527)

Shortly after the second Zurich disputation, many in the radical wing of the Reformation became convinced that Zwingli was making too many concessions to the Zurich council. They rejected the role of civil government and demanded the immediate establishment of a congregation of the faithful.Conrad Grebel

Conrad Grebel ( – 1526) was a co-founder of the Swiss Brethren movement.

Early life

Conrad Grebel was born, probably in Grüningen in the canton of Zürich, about 1498 to Junker Jakob and Dorothea (Fries) Grebel, the second of six children ...

, the leader of the radicals and the emerging Anabaptist movement, spoke disparagingly of Zwingli in private. The Anabaptists in Zurich believed Zwingli's conception of the Reformed faith and the church conflicted their teachings and attempted to claim legislation of Zwingli's early teachings. On 15 August 1524 the council insisted on the obligation to baptise all newborn infants. Zwingli secretly conferred with Grebel's group and late in 1524, the council called for official discussions. When talks were broken off, Zwingli published ''Wer Ursache gebe zu Aufruhr'' (Whoever Causes Unrest) clarifying the opposing points of view. On 17 January 1525 a public debate was held and the council decided in favour of Zwingli. Anyone refusing to have their children baptised was required to leave Zurich. The radicals ignored these measures and on 21 January, they met at the house of the mother of another radical leader, Felix Manz. Grebel and a third leader, George Blaurock, performed the first recorded Anabaptist adult baptisms.

On 2 February, the council repeated the requirement on the baptism of all babies and some who failed to comply were arrested and fined, Manz and Blaurock among them. Zwingli and Jud interviewed them and more debates were held before the Zurich council. Meanwhile, the new teachings continued to spread to other parts of the Confederation as well as a number of Swabia

Swabia ; , colloquially ''Schwabenland'' or ''Ländle''; archaic English also Suabia or Svebia is a cultural, historic and linguistic region in southwestern Germany.

The name is ultimately derived from the medieval Duchy of Swabia, one of ...

n towns. On 6–8 November, the last debate on the subject of baptism took place in the Grossmünster. Grebel, Manz, and Blaurock defended their cause before Zwingli, Jud, and other reformers. There was no serious exchange of views as each side would not move from their positions and the debates degenerated into an uproar, each side shouting abuse at the other.

The Zurich council decided that no compromise was possible. On 7 March 1526 it released the notorious mandate that no one shall rebaptise another under the penalty of death. Although Zwingli, technically, had nothing to do with the mandate, there is no indication that he disapproved. Felix Manz, who had sworn to leave Zurich and not to baptise any more, had deliberately returned and continued the practice. After he was arrested and tried, he was executed on 5 January 1527 by being drowned in the Limmat

The Limmat is a river in Switzerland. The river commences at the outfall of Lake Zurich, in the southern part of the city of Zurich. From Zurich it flows in a northwesterly direction, continuing a further 35 km until it reaches the river A ...

. He was the first Anabaptist martyr; three more were to follow, after which all others either fled or were expelled from Zurich.

Reformation in the Confederation (1526–1528)

On 8 April 1524, five cantons,

On 8 April 1524, five cantons, Lucerne

Lucerne ( ) or Luzern ()Other languages: ; ; ; . is a city in central Switzerland, in the Languages of Switzerland, German-speaking portion of the country. Lucerne is the capital of the canton of Lucerne and part of the Lucerne (district), di ...

, Uri

Uri may refer to:

Places

* Canton of Uri, a canton in Switzerland

* Úri, a village and commune in Hungary

* Uri, Iran, a village in East Azerbaijan Province

* Uri, Jammu and Kashmir, a town in India

* Uri (island), off Malakula Island in V ...

, Schwyz

Schwyz (; ; ) is a town and the capital of the canton of Schwyz in Switzerland.

The Federal Charter of 1291 or ''Bundesbrief'', the charter that eventually led to the foundation of Switzerland, can be seen at the ''Bundesbriefmuseum''.

The of ...

, Unterwalden

Unterwalden, translated from the Latin ''inter silvas'' ("between the forests"), is the old name of a forest-canton of the Old Swiss Confederacy in central Switzerland, south of Lake Lucerne, consisting of two valleys or '' Talschaften'', now tw ...

, and Zug

Zug (Standard German: , Alemannic German: ; ; ; ; )Named in the 16th century. is the largest List of cities in Switzerland, town and capital of the Swiss canton of Zug. Zug is renowned as a hub for some of the wealthiest individuals in the wor ...

, formed an alliance, ''die fünf Orte'' (the Five States) to defend themselves from Zwingli's Reformation. They contacted the opponents of Martin Luther including John Eck, who had debated Luther in the Leipzig Disputation

The Leipzig Debate () was a theological disputation originally between Andreas Karlstadt, Martin Luther and Johann Eck. Karlstadt, the dean of the Wittenberg theological faculty, felt that he had to defend Luther against Eck's critical commenta ...

of 1519. Eck offered to dispute Zwingli and he accepted. However, they could not agree on the selection of the judging authority, the location of the debate, and the use of the Swiss Diet as a court. Because of the disagreements, Zwingli decided to boycott the disputation. On 19 May 1526, all the cantons sent delegates to Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in southern Germany. In earlier times it was considered to be on both sides of the Upper Rhine, but since the Napoleonic Wars, it has been considered only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Ba ...

. Although Zurich's representatives were present, they did not participate in the sessions. Eck led the Catholic party while the reformers were represented by Johannes Oecolampadius

Johannes Oecolampadius (also ''Œcolampadius'', in German also Oekolampadius, Oekolampad; 1482 – 24 November 1531) was a German Protestant reformer in the Calvinist tradition from the Electoral Palatinate. He was the leader of the Protestant ...

of Basel, a theologian from Württemberg

Württemberg ( ; ) is a historical German territory roughly corresponding to the cultural and linguistic region of Swabia. The main town of the region is Stuttgart.

Together with Baden and Province of Hohenzollern, Hohenzollern, two other histo ...

who had carried on an extensive and friendly correspondence with Zwingli. While the debate proceeded, Zwingli was kept informed of the proceedings and printed pamphlets giving his opinions. It was of little use as the Diet decided against Zwingli. He was to be banned and his writings were no longer to be distributed. Of the thirteen Confederation members, Glarus

Glarus (; ; ; ; ) is the capital of the canton of Glarus in Switzerland. Since 1 January 2011, the municipality of Glarus incorporates the former municipalities of Ennenda, Netstal and Riedern.Solothurn

Solothurn ( ; ; ; ; ) is a town, a municipality, and the capital of the canton of Solothurn in Switzerland. It is located in the north-west of Switzerland on the banks of the Aare and on the foot of the Weissenstein Jura mountains.

The town is ...

, Fribourg

or is the capital of the Cantons of Switzerland, Swiss canton of Canton of Fribourg, Fribourg and district of Sarine (district), La Sarine. Located on both sides of the river Saane/Sarine, on the Swiss Plateau, it is a major economic, adminis ...

, and Appenzell

Appenzell () was a cantons of Switzerland, canton in the northeast of Switzerland, and entirely surrounded by the canton of St. Gallen, in existence from 1403 to 1597.

Appenzell became independent of the Abbey of Saint Gall in 1403 and entered ...

as well as the Five States voted against Zwingli. Bern

Bern (), or Berne (), ; ; ; . is the ''de facto'' Capital city, capital of Switzerland, referred to as the "federal city".; ; ; . According to the Swiss constitution, the Swiss Confederation intentionally has no "capital", but Bern has gov ...

, Basel

Basel ( ; ), also known as Basle ( ), ; ; ; . is a city in northwestern Switzerland on the river Rhine (at the transition from the High Rhine, High to the Upper Rhine). Basel is Switzerland's List of cities in Switzerland, third-most-populo ...

, Schaffhausen

Schaffhausen (; ; ; ; ), historically known in English as Shaffhouse, is a list of towns in Switzerland, town with historic roots, a municipalities of Switzerland, municipality in northern Switzerland, and the capital of the canton of Schaffh ...

, and Zurich

Zurich (; ) is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich. , the municipality had 448,664 inhabitants. The ...

supported him.

The Baden disputation exposed a deep rift in the Confederation on matters of religion. The Reformation was now emerging in other states. The city of St Gallen

St. Gallen is a Swiss city and the capital of the canton of St. Gallen. It evolved from the hermitage of Saint Gall, founded in the 7th century. Today, it is a large urban agglomeration (with around 167,000 inhabitants in 2019) and rep ...

, an affiliated state to the Confederation, was led by a reformed mayor, Joachim Vadian

Joachim Vadian (29 November 1484 – 6 April 1551), born as Joachim von Watt, was a humanist, scholar, mayor and reformer in the free city of St. Gallen.

Biography

Vadian was born in St. Gallen into a family of wealthy and influential linen ...

, and the city abolished the mass in 1527, just two years after Zurich. In Basel, although Zwingli had a close relationship with Oecolampadius, the government did not officially sanction any reformatory changes until 1 April 1529 when the mass was prohibited. Schaffhausen, which had closely followed Zurich's example, formally adopted the Reformation in September 1529.

In the case of Bern, Berchtold Haller

Berchtold Haller (c. 149225 February 1536) was a German Protestant reformer. He was the reformer of the city of Bern, Switzerland, where the Reformation received little to none opposition.

Haller was born at Aldingen in Württemberg. After schooli ...

, the priest at St Vincent Münster, and Niklaus Manuel

Niklaus Manuel Deutsch (''Niklaus Manuel'', c. 1484 – 28 April 1530), of Bern, was a Swiss artist, writer, mercenary and Reformed politician.

Biography

Niklaus was most likely the son of Emanuel Aleman (or Alleman), a pharmacist whose own fa ...

, the poet, painter, and politician, had campaigned for the reformed cause. But it was only after another disputation that Bern counted itself as a canton of the Reformation. Three hundred and fifty persons participated, including pastors from Bern and other cantons as well as theologians from outside the Confederation such as Martin Bucer

Martin Bucer (; Early German: ; 11 November 1491– 28 February 1551) was a German Protestant reformer based in Strasbourg who influenced Lutheran, Anglican doctrines and practices as well as Reformed Theology. Bucer was originally a memb ...

and Wolfgang Capito

Wolfgang Fabricius Capito (also Koepfel) ( – November 1541) was a German Protestant reformer in the Calvinist tradition.

His life and revolutionary work

Capito was born circa 1478 to a smith at Hagenau in Alsace. He attended the famous Lati ...

from Strasbourg

Strasbourg ( , ; ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est Regions of France, region of Geography of France, eastern France, in the historic region of Alsace. It is the prefecture of the Bas-Rhin Departmen ...

, Ambrosius Blarer

Ambrosius Blarer (sometimes Ambrosius Blaurer; April 4, 1492 – December 6, 1564) was an influential Protestant reformer in southern Germany and north-eastern Switzerland.

Early life

Ambrosius Blarer was born 1492 into a leading family of Kons ...

from Constance

Constance may refer to:

Places

* Constance, Kentucky, United States, an unincorporated community

* Constance, Minnesota, United States, an unincorporated community

* Mount Constance, Washington State, United States

* Lake Constance (disambiguat ...

, and Andreas Althamer from Nuremberg

Nuremberg (, ; ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the Franconia#Towns and cities, largest city in Franconia, the List of cities in Bavaria by population, second-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Bav ...

. Eck and Fabri refused to attend and the Catholic cantons did not send representatives. The meeting started on 6 January 1528 and lasted nearly three weeks. Zwingli assumed the main burden of defending the Reformation and he preached twice in the Münster. On 7 February 1528 the council decreed that the Reformation be established in Bern.

First Kappel War (1529)

Even before theBern Disputation

The Bern Disputation was a debate over the theology of the Swiss Reformation that occurred in Bern from 6 to 26 January 1528 that ended in Bern becoming the second Swiss canton to officially become Protestant.

Background

As the reformation in ...

, Zwingli was canvassing for an alliance of reformed cities. Once Bern officially accepted the Reformation, a new alliance, ''das Christliche Burgrecht

A Burgrecht (''ius burgense, ius civile'') was a medieval agreement, most commonly in southern Germany and northern German-speaking Switzerland. It came to refer to an agreement between a town and surrounding settlements or to include the specific ...

'' (the Christian Civic Union) was created. The first meetings were held in Bern between representatives of Bern, Constance, and Zurich on 5–6 January 1528. Other cities, including Basel, Biel

Biel/Bienne (official bilingual wording; German language, German: ''Biel'' ; French language, French: ''Bienne'' ; Bernese German, locally ; ; ; ) is a bilingual city in the canton of Bern in Switzerland. With over 55,000 residents, it is the ...

, Mülhausen

Mulhouse (; ; Alsatian language, Alsatian: ''Mìlhüsa'' ; , meaning "Mill (grinding), mill house") is a France, French city of the European Collectivity of Alsace (Haut-Rhin department, in the Grand Est region of France). It is near the Fran ...

, Schaffhausen, and St Gallen, eventually joined the alliance. The Five (Catholic) States felt encircled and isolated, so they searched for outside allies. After two months of negotiations, the Five States formed ''die Christliche Vereinigung'' (the Christian Alliance) with Ferdinand of Austria on 22 April 1529.

Soon after the Austrian treaty was signed, a reformed preacher, Jacob Kaiser, was captured in

Soon after the Austrian treaty was signed, a reformed preacher, Jacob Kaiser, was captured in Uznach

Uznach is a municipality in the ''Wahlkreis'' (constituency) of See-Gaster in the canton of St. Gallen in Switzerland.

History

Uznach is first mentioned in 741 as ''Uzinaa'' in a grant from a noble lady at Benken Abbey to the Abbey of Saint ...

and executed in Schwyz. This triggered a strong reaction from Zwingli; he drafted ''Ratschlag über den Krieg'' (Advice About the War) for the government. He outlined justifications for an attack on the Catholic states and other measures to be taken. Before Zurich could implement his plans, a delegation from Bern that included Niklaus Manuel arrived in Zurich. The delegation called on Zurich to settle the matter peacefully. Manuel added that an attack would expose Bern to further dangers as Catholic Valais

Valais ( , ; ), more formally, the Canton of Valais or Wallis, is one of the cantons of Switzerland, 26 cantons forming the Switzerland, Swiss Confederation. It is composed of thirteen districts and its capital and largest city is Sion, Switzer ...

and the Duchy of Savoy bordered its southern flank. He then noted, "You cannot really bring faith by means of spears and halberds." Zurich, however, decided that it would act alone, knowing that Bern would be obliged to acquiesce. War was declared on 8 June 1529. Zurich was able to raise an army of 30,000 men. The Five States were abandoned by Austria and could raise only 9,000 men. The two forces met near Kappel, but war was averted due to the intervention of Hans Aebli, a relative of Zwingli, who pleaded for an armistice.

Zwingli was obliged to state the terms of the armistice. He demanded the dissolution of the Christian Alliance; unhindered preaching by reformers in the Catholic states; prohibition of the pension system; payment of war reparations; and compensation to the children of Jacob Kaiser. Manuel was involved in the negotiations. Bern was not prepared to insist on the unhindered preaching or the prohibition of the pension system. Zurich and Bern could not agree and the Five (Catholic) States pledged only to dissolve their alliance with Austria. This was a bitter disappointment for Zwingli and it marked his decline in political influence. The first Land Peace of Kappel, ''der erste Landfriede

Under the law of the Holy Roman Empire, a ''Landfrieden'' or ''Landfriede'' (Latin: ''constitutio pacis'', ''pax instituta'' or ''pax jurata'', variously translated as "land peace", or "public peace") was a contractual waiver of the use of legiti ...

'', ended the war on 24 June.

Marburg Colloquy (1529)

While Zwingli carried on the political work of the Swiss Reformation, he developed his theological views with his colleagues. The famous disagreement between Luther and Zwingli on the interpretation of theeucharist