Hugh Kilpatrick on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

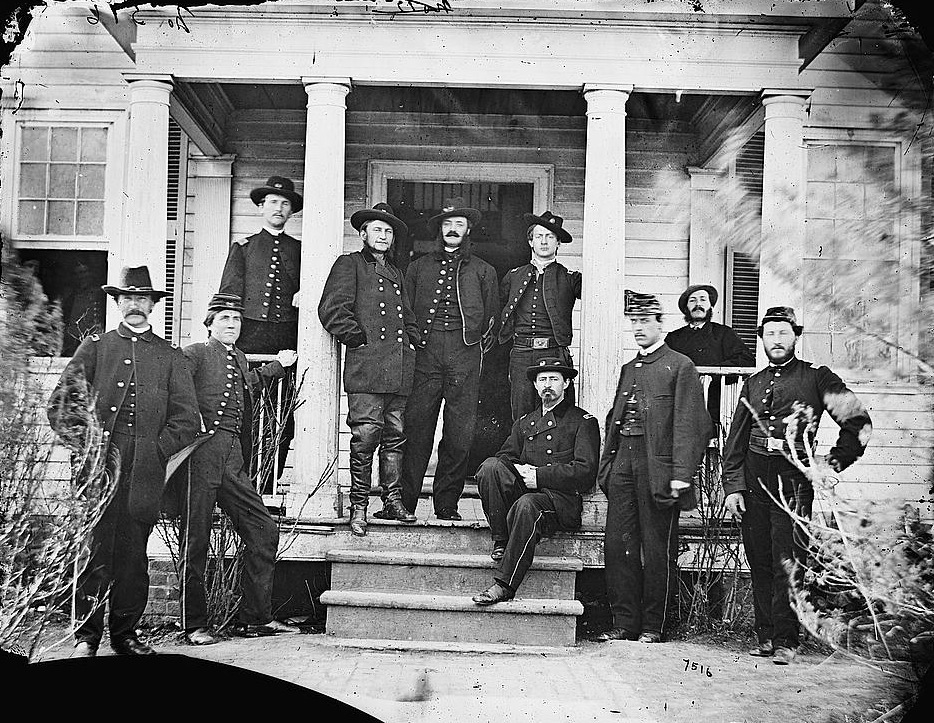

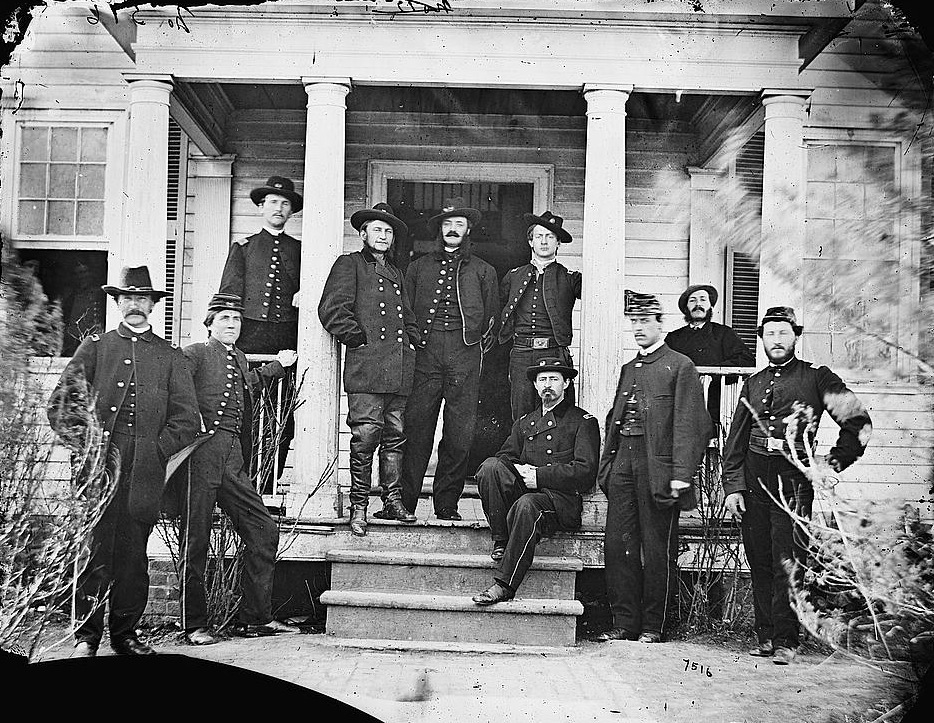

Hugh Judson Kilpatrick (January 14, 1836 – December 4, 1881) was an officer in the Union Army during the

In February 1863, Maj. Gen.

In February 1863, Maj. Gen.

At the beginning of the Gettysburg Campaign, on June 9, 1863, Kilpatrick fought at Brandy Station, the largest cavalry battle of the war. He received his brigadier general's star at the age of 27 on June 13, fought at Aldie and Upperville, and assumed division command three days before the

At the beginning of the Gettysburg Campaign, on June 9, 1863, Kilpatrick fought at Brandy Station, the largest cavalry battle of the war. He received his brigadier general's star at the age of 27 on June 13, fought at Aldie and Upperville, and assumed division command three days before the

Just before the start of Lt. Gen.

Just before the start of Lt. Gen.

Summing up Judson Kilpatrick in 1864, Sherman said "I know that Kilpatrick is a hell of a damned fool, but I want just that sort of man to command my cavalry on this expedition."

Starting in May 1864, Kilpatrick rode in the Atlanta Campaign. On May 13, he was severely wounded in the thigh at the

Summing up Judson Kilpatrick in 1864, Sherman said "I know that Kilpatrick is a hell of a damned fool, but I want just that sort of man to command my cavalry on this expedition."

Starting in May 1864, Kilpatrick rode in the Atlanta Campaign. On May 13, he was severely wounded in the thigh at the

Gettysburg Discussion Group research article

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kilpatrick, Hugh Judson 1836 births 1881 deaths 19th-century American diplomats Ambassadors of the United States to Chile People of New Jersey in the American Civil War People from Wantage Township, New Jersey Union army generals United States Military Academy alumni Burials at West Point Cemetery New Jersey Republicans Writers from Sussex County, New Jersey

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, achieving the rank of major general. He was later the United States Minister to Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

and an unsuccessful candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

.

Nicknamed "Kilcavalry" (or "Kill-Cavalry") for using tactics in battle that were considered as recklessly disregarding the lives of soldiers under his command, Kilpatrick was both praised for the victories he achieved, and despised by Southerners whose homes and towns he devastated.

Early life

Hugh Judson Kilpatrick, more commonly referred to as Judson Kilpatrick, the fourth child of Colonel Simon Kilpatrick and Julia Wickham, was born on the family farm in Wantage Township, near Deckertown, New Jersey (now Sussex Borough).Civil War

Kilpatrick graduated from theUnited States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

in 1861, just after the start of the war, and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 1st U.S. Artillery. Within three days he was a captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

in the 5th New York Infantry (" Duryée's Zouaves").

Kilpatrick was the first United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

officer to be wounded in the Civil War, struck in the thigh by canister fire while leading a company at the Battle of Big Bethel

The Battle of Big Bethel, also known as the Battle of Bethel Church or Great Bethel, was one of the earliest, if not the first, land battle of the American Civil War. It took place on the Virginia Peninsula, near Newport News, on June 10, 1861 ...

, June 10, 1861. Felix Agnus

Felix Agnus (4 May 1839 – 31 October 1925) (born Antoine-Felix) was a French-born sculptor, newspaper publisher and soldier who served in the Franco-Austrian War and the American Civil War. Agnus studied sculpture before enlisting to fight i ...

is credited with saving his life after being injured in the battle. By September 25 he was a lieutenant colonel, now of the 2nd New York Cavalry Regiment, which he helped to raise, and it was the mounted arm that brought him fame and infamy.

Assignments were initially quiet for Lt. Col. Kilpatrick, serving in staff jobs and in minor cavalry skirmishes. That changed in the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederate ...

in August 1862. He raided the Virginia Central Railroad

The Virginia Central Railroad was an early railroad in the U.S. state of Virginia that operated between 1850 and 1868 from Richmond westward for to Covington. Chartered in 1836 as the Louisa Railroad by the Virginia General Assembly, the railr ...

early in the campaign and then ordered a twilight cavalry charge the first evening of the battle, losing a full squadron of troopers. Nevertheless, he was promoted to full colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

on December 6.

Kilpatrick was aggressive, fearless, ambitious, and blustery. He was a master, in his mid-twenties, of using political influence to get ahead. His men had little love for his manner and his willingness to exhaust men and horses and to order suicidal mounted cavalry charges. (The rifled muskets introduced to warfare in the 1850s made the historic cavalry charge essentially an anachronism. Cavalry's role shrank primarily to screening, raiding, reconnaissance and intelligence gathering.)

The widespread nickname his troopers used for Kilpatrick was "Kill Cavalry". He also had a bad reputation with others in the Army. His camps were poorly maintained and frequented by prostitutes, often visiting Kilpatrick himself. He was jailed in 1862 on charges of corruption, accused of selling captured Confederate

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

goods for personal gain. He was jailed again for a drunken spree in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, and for allegedly accepting bribes in the procurement of horses for his command.

In February 1863, Maj. Gen.

In February 1863, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

created a Cavalry Corps

Corps (; plural ''corps'' ; from French , from the Latin "body") is a term used for several different kinds of organization. A military innovation by Napoleon I, the formation was formally introduced March 1, 1800, when Napoleon ordered Gener ...

in the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the primary field army of the Union army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the Battle of ...

, commanded by Maj. Gen. George Stoneman. Kilpatrick assumed command of the 1st Brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military unit, military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute ...

, 2nd Division. In the Chancellorsville Campaign in May, Stoneman's cavalry was ordered to swing deeply behind Gen. Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

's army and destroy railroads and supplies. Kilpatrick did just that, with gusto. Although the corps failed to distract Lee as intended, Kilpatrick achieved fame by aggressively capturing wagons, burning bridges, and riding around Lee, almost to the outskirts of Richmond, Virginia

Richmond ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. Incorporated in 1742, Richmond has been an independent city (United States), independent city since 1871. ...

, in Stoneman's 1863 raid.

Gettysburg Campaign

At the beginning of the Gettysburg Campaign, on June 9, 1863, Kilpatrick fought at Brandy Station, the largest cavalry battle of the war. He received his brigadier general's star at the age of 27 on June 13, fought at Aldie and Upperville, and assumed division command three days before the

At the beginning of the Gettysburg Campaign, on June 9, 1863, Kilpatrick fought at Brandy Station, the largest cavalry battle of the war. He received his brigadier general's star at the age of 27 on June 13, fought at Aldie and Upperville, and assumed division command three days before the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was a three-day battle in the American Civil War, which was fought between the Union and Confederate armies between July 1 and July 3, 1863, in and around Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The battle, won by the Union, ...

commenced. On June 21, he was captured at Upperville, but was quickly rescued, going on to risk his life that same day in order to rescue the wounded commander of the 5th North Carolina Cavalry. On June 30, he clashed briefly with J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry at Hanover, Pennsylvania

Hanover is a borough in York County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 16,429 at the 2020 census. Located southwest of York and north-northwest of Baltimore, Maryland, the town is situated in a productive agricultural region. It i ...

, but then proceeded on a wild goose chase in pursuit of Stuart, rather than fulfilling his mission of intelligence gathering.

On the second day of the Gettysburg battle, July 2, 1863, Kilpatrick's division skirmished against Wade Hampton Wade Hampton may refer to the following people:

People

*Wade Hampton I (1752–1835), American soldier in Revolutionary War and War of 1812 and U.S. congressman

* Wade Hampton II (1791–1858), American plantation owner and soldier in War of 1812

* ...

five miles northeast of town at Hunterstown. He then settled in for the night to the southeast at Two Taverns. One of his brigade commanders, Brig. Gen. George A. Custer, was ordered to join Brig. Gen. David McM. Gregg's division for the next day's action against Stuart's cavalry east of town, so Kilpatrick was down to one brigade. On July 3, after Pickett's Charge

Pickett's Charge was an infantry assault on July 3, 1863, during the Battle of Gettysburg. It was ordered by Confederate General Robert E. Lee as part of his plan to break through Union lines and achieve a decisive victory in the North. T ...

, he was ordered by army commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade and Cavalry Corps commander Alfred Pleasonton to launch a cavalry charge against the infantry positions of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was a General officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War and was the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Ho ...

's Corps on the Confederate right flank, just west of Little Round Top

Little Round Top is the smaller of two rocky hills south of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania—the companion to the adjacent, taller hill named Big Round Top. It was the site of an unsuccessful assault by Confederate troops against the Union left ...

. Kilpatrick's lone brigade commander, Brig. Gen. Elon J. Farnsworth, protested against the futility of such a move. Kilpatrick essentially questioned his bravery and allegedly dared him to charge: "Then, by God, if you are afraid to go I will lead the charge myself." Farnsworth reluctantly complied with the order. He was killed in the attack and his brigade suffered significant losses.

Kilpatrick and the rest of the cavalry pursued and harassed Lee during his retreat back to Virginia. In late August, he took part in an expedition to destroy the Confederate gunboats ''Satellite'' and ''Reliance'' in the Rappahannock River

The Rappahannock River is a river in eastern Virginia, in the United States, approximately in length.U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 It traverses the enti ...

, boarding them and capturing their crews successfully.

Kilpatrick's cavalry division participated in the Bristoe Campaign that October, but suffered an embarrassing defeat at its conclusion when they were lured into an ambush and routed at Buckland Mills.

In November, he received new of his young wife’s death and was absent for the Mine Run Campaign

The Battle of Mine Run, also known as Payne's Farm, or New Hope Church, or the Mine Run campaign (November 27 – December 2, 1863), was conducted in Orange County, Virginia, in the American Civil War.

An unsuccessful attempt of the Union ...

. Within two months his infant son also died.

The Dahlgren Affair

Just before the start of Lt. Gen.

Just before the start of Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

's Overland Campaign

The Overland Campaign, also known as Grant's Overland Campaign and the Wilderness Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864, towards the end of the American Civil War. Lieutenant general (United States), Lt. G ...

in the spring of 1864, Kilpatrick conducted a raid toward Richmond and through the Virginia Peninsula

The Virginia Peninsula is the natural landform located in southeast Virginia outlined by the York River, James River, Hampton Roads and Chesapeake Bay. It is sometimes known as the ''Lower Peninsula'' to distinguish it from two other penins ...

, hoping to rescue Union prisoners of war held at Belle Isle and in Libby Prison

Libby Prison was a Confederate States of America, Confederate prison at Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. In 1862 it was designated to hold officer prisoners from the Union Army, taking in numbers from the nearby Seven Days battl ...

s in Richmond. Kilpatrick took his division out on February 28, sneaking past Robert E. Lee's flank and driving south for Richmond. On March 1, they were within 5 miles of the city. Defenses around the city were too strong however and numerous squads of Confederate militia and cavalry nipped at their heels the whole way, including some of General Wade Hampton Wade Hampton may refer to the following people:

People

*Wade Hampton I (1752–1835), American soldier in Revolutionary War and War of 1812 and U.S. congressman

* Wade Hampton II (1791–1858), American plantation owner and soldier in War of 1812

* ...

's troopers dispatched from the Army of Northern Virginia.

Unable to get at Richmond or return to the Army of the Potomac, Kilpatrick decided to bolt down the Virginia Peninsula where Ben Butler's Army of the James

The Army of the James was a Union Army that was composed of units from the Department of Virginia and North Carolina and served along the James River during the final operations of the American Civil War in Virginia.

History

The Union Department ...

was stationed. Meanwhile, the general was dismayed to find out that Ulric Dahlgren

Ulric Dahlgren (April 3, 1842 – March 2, 1864) was an American military officer who served as Colonel (United States), colonel in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He was the son of Union Navy Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren and ...

's brigade (detached from the main force) had not made it across the James River. Eventually 300 of the latter's troopers stumbled into camp, Dahlgren and the rest seemingly vanished into thin air. The survivors reported that they had made a nightmarish journey through the countryside around Richmond in darkness and a sleet storm, the woods filled with enemy troops and hostile civilians at every turn. Dahlgren and the 200 cavalrymen he was accompanying had been told by a slave of a place where the James was shallow and could be forded. When they got there, the river was swelled up and cresting. Convinced he had been tricked, Dahlgren ordered the slave hanged. They went back north and found that Kilpatrick was gone and they were alone in a hostile country.

The troopers battled their way to the Mattaponi River

The Mattaponi River is a tributary of the York River estuary in eastern Virginia in the United States.

History

Historically, the Mattaponi River has been known by a variety of names and alternate spellings, including ''Mat-ta-pa-ment'', Matap ...

, crossed, and appeared to be safe from danger, but in the dark they ran into a Confederate ambush. Dahlgren was shot dead along with many of his men, the rest being taken prisoner. His body was then displayed in Richmond as a war trophy. Papers found on the body of Dahlgren shortly after his death described the object of the expedition, apparently indicating that he intended to burn and loot Richmond and assassinate Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the only President of the Confederate States of America, president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the Unite ...

and the whole Confederate cabinet.

The raid had resulted in 324 cavalrymen killed and wounded, and 1,000 more taken prisoner. Kilpatrick's men had cut a swathe of destruction across the outskirts of Richmond, destroying tobacco barns, boats, railroad cars and tracks, and other infrastructure. They also deposited a large number of pamphlets in and around homes and other buildings offering amnesty to any Southern civilian who took the oath of loyalty to the United States. During the raid BG John H. Winder, Provost Marshal of Richmond, was so concerned that Union POWs held in Richmond Libby prison would try to escape that he ordered gunpowder placed under the building, to be detonated if they attempted to escape.

The discovery and publication of the Dahlgren Papers sparked an international controversy. General Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg (March 22, 1817 – September 27, 1876) was an American army Officer (armed forces), officer during the Second Seminole War and Mexican–American War and Confederate General officers in the Confederate States Army, general in th ...

denounced the papers as "fiendish" and Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon proposed that the Union prisoners be hanged. Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

agreed that they made for an atrocious document, but urged calm, saying that no actual destruction had taken place and the papers might very well be fakes. In addition, Lee was concerned because some Confederate guerrillas had just been captured by the Army of the Potomac, which was considering hanging them, and execution of Dahlgren's men might set off a chain reaction. The Confederate general sent the papers to George Meade

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was an American military officer who served in the United States Army and the Union army as Major General in command of the Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War from 1 ...

under a flag of truce and asked him to provide an explanation. Meade wrote back that no burnings or assassinations had been ordered by anyone in Washington or the army.

Meanwhile, newspapers and politicians in the North and South exchanged blows. The former condemned the use of Ulric Dahlgren's corpse as a carnival attraction and the latter accused Lincoln's government of wanting to conduct indiscriminate pillage and slaughter on Virginia civilians, including the claim that Kilpatrick wanted to free Union prisoners and turn them loose on the women of Richmond. Northern papers also cheered the destruction caused by the raid and took pleasure in describing the ravaged condition of the Virginia countryside.

After reaching Ben Butler's base at Fort Monroe

Fort Monroe is a former military installation in Hampton, Virginia, at Old Point Comfort, the southern tip of the Virginia Peninsula, United States. It is currently managed by partnership between the Fort Monroe Authority for the Commonwealth o ...

, Kilpatrick's men took a steamship back to Washington. More trouble followed when they were granted a few days' rest in Alexandria, Virginia

Alexandria is an independent city (United States), independent city in Northern Virginia, United States. It lies on the western bank of the Potomac River approximately south of Washington, D.C., D.C. The city's population of 159,467 at the 2020 ...

before rejoining the Army of the Potomac. The city was garrisoned with African-American troops, and one stopped to inform a cavalryman that only persons on active duty were allowed to ride horses through the streets. This trooper found it insulting to take orders from a black man and promptly struck him down with his sword. Kilpatrick's division was punished by being forced to immediately embark for the Rapidan River

The Rapidan River, flowing U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 through north-central Virginia in the United States, is the largest tributary of the Rappahannoc ...

without resting or drawing new uniforms.

The "Kilpatrick-Dahlgren" expedition was such a fiasco that Kilpatrick found he was no longer welcome in the Eastern Theater. He transferred west to command the 3rd Division of the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Cumberland

The Army of the Cumberland was one of the principal Union armies in the Western Theater during the American Civil War. It was originally known as the Army of the Ohio.

History

The origin of the Army of the Cumberland dates back to the creatio ...

, under Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a General officer, general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), earning recognit ...

.

Final campaigns through Georgia and the Carolinas

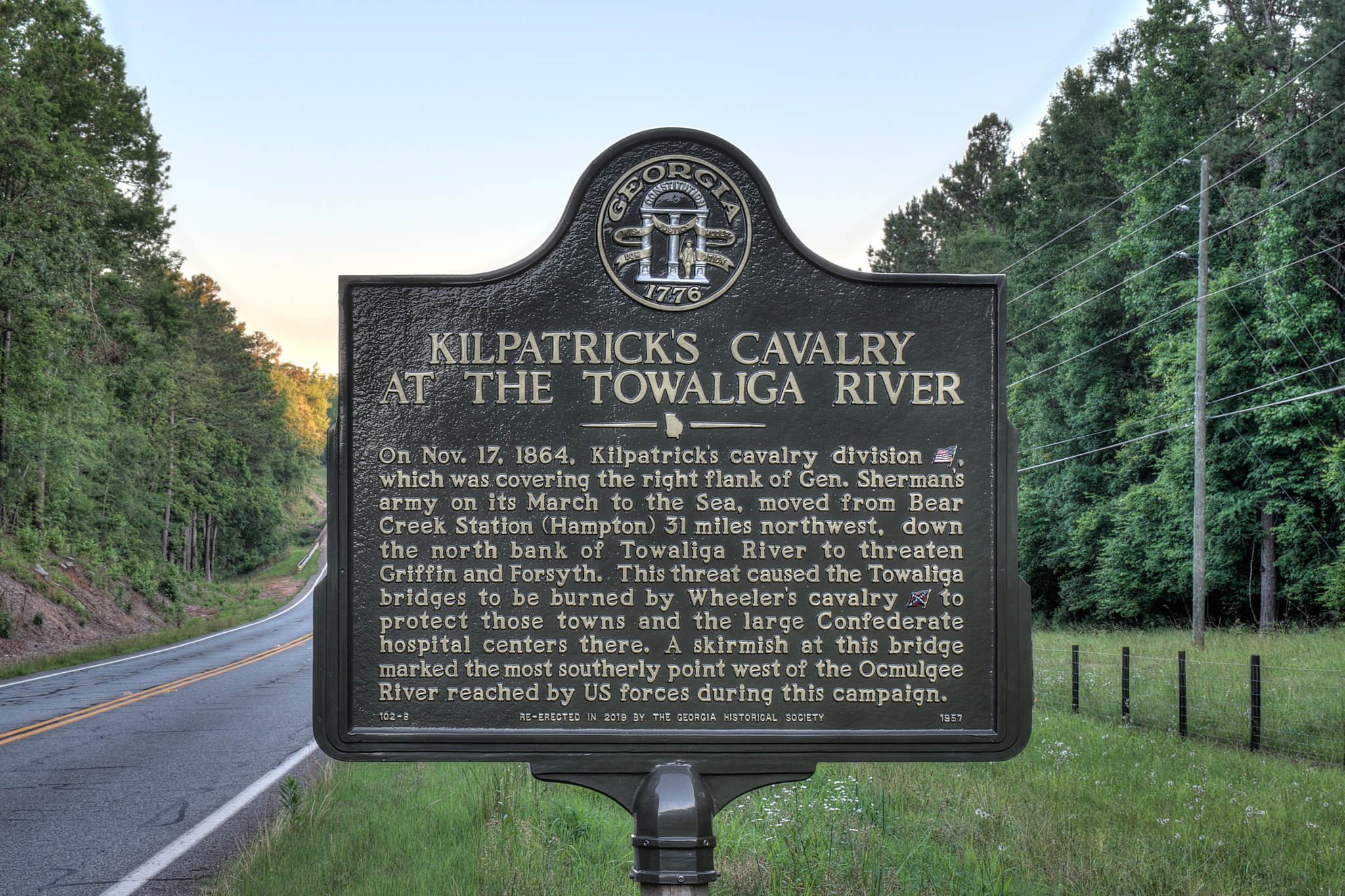

Summing up Judson Kilpatrick in 1864, Sherman said "I know that Kilpatrick is a hell of a damned fool, but I want just that sort of man to command my cavalry on this expedition."

Starting in May 1864, Kilpatrick rode in the Atlanta Campaign. On May 13, he was severely wounded in the thigh at the

Summing up Judson Kilpatrick in 1864, Sherman said "I know that Kilpatrick is a hell of a damned fool, but I want just that sort of man to command my cavalry on this expedition."

Starting in May 1864, Kilpatrick rode in the Atlanta Campaign. On May 13, he was severely wounded in the thigh at the Battle of Resaca

The Battle of Resaca, from May 13 to 15, 1864, formed part of the Atlanta Campaign during the American Civil War, when a Union force under William Tecumseh Sherman engaged the Confederate Army of Tennessee led by Joseph E. Johnston. The battle ...

and his injuries kept him out of the field until late July. He had considerable success raiding behind Confederate lines, tearing up railroads, and at one point rode his division completely around the enemy positions in Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

. His division played a significant role in the Battle of Jonesborough

The Battle of Jonesborough (August 31–September 1, 1864) was fought between Union Army forces led by William Tecumseh Sherman and Confederate States of America, Confederate forces under William J. Hardee during the Atlanta Campaign in the Am ...

on August 31, 1864.

Kilpatrick continued with Sherman through his March to the Sea to Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) biome and ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach th ...

and north in the Carolinas Campaign. He delighted in destroying Southern property. On two occasions his coarse personal instincts betrayed him: Confederate cavalry under the command of Maj. Gen. Wade Hampton Wade Hampton may refer to the following people:

People

*Wade Hampton I (1752–1835), American soldier in Revolutionary War and War of 1812 and U.S. congressman

* Wade Hampton II (1791–1858), American plantation owner and soldier in War of 1812

* ...

raided his camp while he was in bed. At the Battle of Monroe's Crossroads, he was forced to flee for his life in his underclothes until his troops could reform. Kilpatrick would march to the city of Aiken, where he would engage with troops under the command of Joseph Wheeler

Joseph "Fighting Joe" Wheeler (September 10, 1836 – January 25, 1906) was a military commander and politician of the Confederate States of America. He was a cavalry general in the Confederate States Army in the 1860s during the American Civil ...

. Kilpatick lost the battle and forced back to his defenses at Montmorenci.

Kilpatrick was fired upon on April 13, 1865 by a reportedly drunk Texas cavalry lieutenant from Wheeler's Cavalry who said he was named Robert Walsh. Walsh fired six shots from his revolver at the approaching General and his staff while several citizens of Raleigh begged him not to, fearing the destruction of the city which had surrendered days earlier. Kilpatrick, after a brief interrogation, ordered his men to take Walsh out of sight of the women and hang him.

Kilpatrick accompanied Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman

William is a masculine given name of Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle Ages and into the modern era. It is ...

to the surrender negotiations held at Bennett Place near Durham, North Carolina

Durham ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of North Carolina and the county seat of Durham County, North Carolina, Durham County. Small portions of the city limits extend into Orange County, North Carolina, Orange County and Wake County, North Carol ...

, on April 17, 1865.

Kilpatrick later commanded a division of the Cavalry Corps in the Military Division of the Mississippi

The Military Division of the Mississippi was an administrative division of the United States Army during the American Civil War that controlled all military operations in the Western Theater from 1863 until the end of the war.

History

The Divisio ...

from April to June 1865, and was promoted to major general of volunteers on June 18, 1865. He resigned from the Army on December 1, 1865.

Later life

Kilpatrick was an early member of theMilitary Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States

The Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), or, simply, the Loyal Legion, is a United States military order organized on April 15, 1865, by three veteran officers of the Union Army. The original membership was consisted ...

, a military society composed of officers who had served in the Union armed forces and their descendants. He was elected a First Class Companion in the Pennsylvania Commandery on November 1, 1865 and was assigned insignia number 63.

Kilpatrick became active in politics as a Republican and in 1880 was an unsuccessful candidate for the U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a bicameral legislature, including a lower body, the U.S. House of Representatives, and an upper body, the U.S. Senate. They both ...

from New Jersey.

In November 1865, Kilpatrick was appointed Minister to Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

. This appointment was announced concurrently with the inclusion of Kilpatrick's name on a list of Republicans arrested for bribery. He was continued as Minister by President Grant.

As American Minister to Chile, Kilpatrick was involved in an attempt to arbitrate between the combatants of the Chincha Islands War

The Chincha Islands War, also known as Spanish–South American War (), was a series of coastal and naval battles between Spain and its former colonies of Peru, Chile, Ecuador, and Bolivia from 1865 to 1879. The conflict began with Spain's seiz ...

after the Valparaiso bombardment (1866). The attempt failed, as the chief condition of Spanish admiral Méndez Núñez was the return of the captured ''Covadonga''. Kilpatrick asked the American naval commander Commander John Rodgers to defend the port and attack the Spanish fleet. Admiral Méndez Núñez famously responded with, "I will be forced to sink he US ships because even if I have one ship left I will proceed with the bombardment. Spain, the Queen and I prefer honor without ships to ships without honor." ("''España prefiere honra sin barcos a barcos sin honra''.")

Kilpatrick was recalled in 1870. The 1865 appointment seems to have been the result of a political deal. Kilpatrick had been a candidate for the Republican nomination for governor of New Jersey but lost out to Marcus Ward. For helping Ward, Kilpatrick was rewarded with the post in Chile. Due to the Grant administration recalling him, Kilpatrick supported Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congres ...

in the 1872 presidential election. By 1876, Kilpatrick returned to the Republicans and supported Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was the 19th president of the United States, serving from 1877 to 1881.

Hayes served as Cincinnati's city solicitor from 1858 to 1861. He was a staunch Abolitionism in the Un ...

for the presidency.

In Chile he married his second wife, Luisa Fernandez de Valdivieso (1836-1928), a member of a wealthy family of Spanish origin that had emigrated to South America in the 17th century. They had two daughters: Julia Mercedes Kilpatrick (b. November 6, 1867 Santiago, Chile) and Laura Delphine Kilpatrick (1874–1956).

In March 1881, in recognition of Kilpatrick's service to the Republicans in New Jersey as well as a consolation prize for his defeat for a House seat, President James Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 1881 until Assassination of James A. Garfield, his death in September that year after being shot two months ea ...

appointed Kilpatrick again to the post of Minister to Chile, where he died shortly after his arrival in the Chilean capital Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile (), is the capital and largest city of Chile and one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is located in the country's central valley and is the center of the Santiago Metropolitan Regi ...

. His remains returned to the United States in 1887 and were interred at the West Point Cemetery

West Point Cemetery is a historic cemetery on the grounds of the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York, West Point, New York (state), New York. It overlooks the Hudson River, and served as a burial ground for Continental Army s ...

in West Point, New York

West Point is the oldest continuously occupied military post in the United States. Located on the Hudson River in New York (state), New York, General George Washington stationed his headquarters in West Point in the summer and fall of 1779 durin ...

.

Kilpatrick was the author of two plays, ''Allatoona: An Historical and Military Drama in Five Acts'' (1875) and ''The Blue and the Gray: Or, War is Hell'' (posthumous, 1930).

Legacy

Battery Kilpatrick atFort Sherman

Fort Sherman is a former United States Army base in Panama, located on Toro Point at the Caribbean (northern) end of the Panama Canal, on the western bank of the Canal directly opposite Colón, Panama, Colón (which is on the eastern bank). It w ...

, on the Atlantic end of the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

, was named for Judson Kilpatrick.

The World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

Liberty Ship

Liberty ships were a ship class, class of cargo ship built in the United States during World War II under the Emergency Shipbuilding Program. Although British in concept, the design was adopted by the United States for its simple, low-cost cons ...

was named in his honor.

The Major General Judson Kilpatrick Camp No. 7, Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War, was formed in September, 2021 in Cary, North Carolina. The camp was named in honor of the general.

See also

* Battle of Gettysburg, Third Day cavalry battles * List of American Civil War generals (Union)References

Notes Further reading * * * * * * * * * *External links

*Gettysburg Discussion Group research article

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kilpatrick, Hugh Judson 1836 births 1881 deaths 19th-century American diplomats Ambassadors of the United States to Chile People of New Jersey in the American Civil War People from Wantage Township, New Jersey Union army generals United States Military Academy alumni Burials at West Point Cemetery New Jersey Republicans Writers from Sussex County, New Jersey