Huey Pierce Long Jr. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

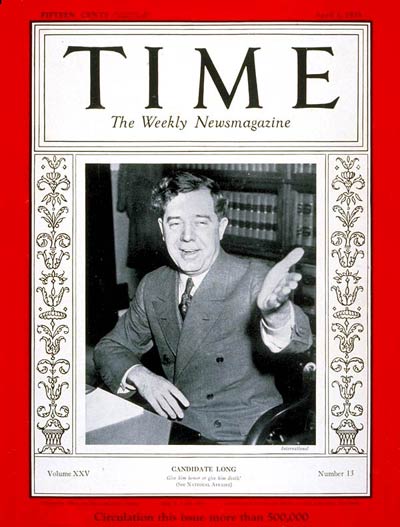

Huey Pierce Long Jr. (August 30, 1893September 10, 1935), nicknamed "The Kingfish", was an American politician who served as the 40th governor of Louisiana from 1928 to 1932 and as a

That same year, Long entered the race to serve on the three-seat Louisiana Railroad Commission. According to historian William Ivy Hair, Long's political message:

That same year, Long entered the race to serve on the three-seat Louisiana Railroad Commission. According to historian William Ivy Hair, Long's political message:

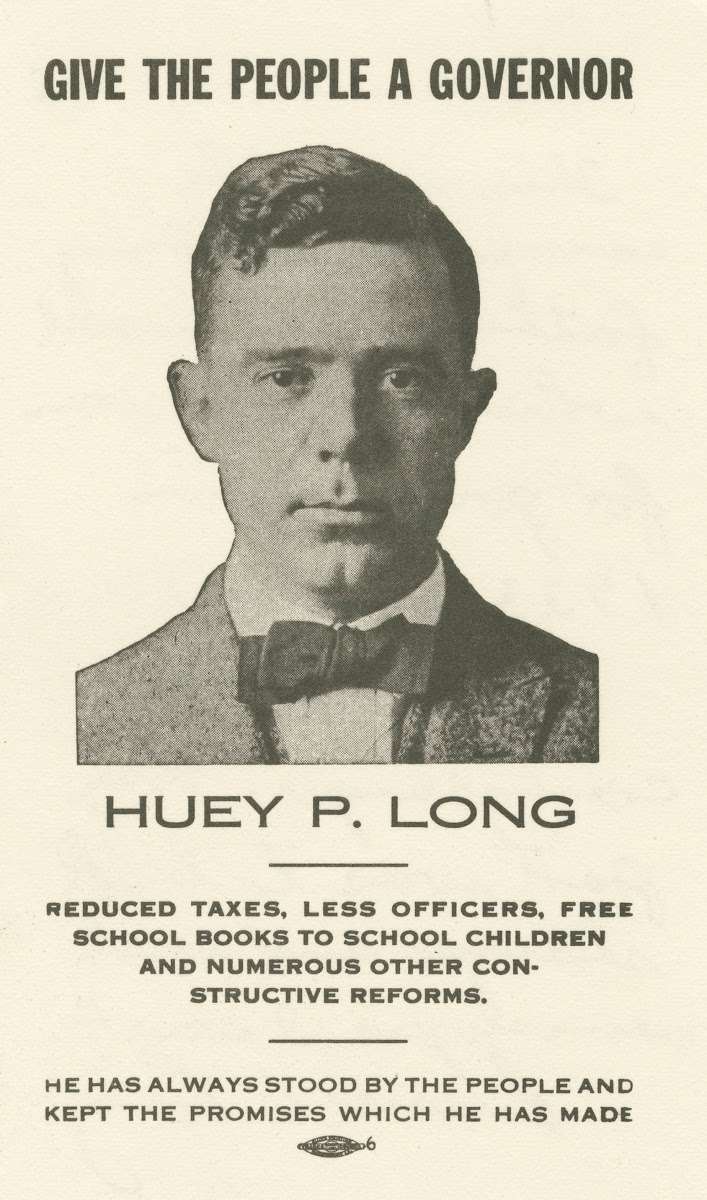

On August 30, 1923, Long announced his candidacy for the governorship of Louisiana. Long

On August 30, 1923, Long announced his candidacy for the governorship of Louisiana. Long

In 1929, Long called a special legislative session to enact a five-cent per barrel tax on refined oil production to fund his social programs. The state's oil interests opposed the bill. Long declared in a radio address that any legislator who refused to support the tax had been "bought" by oil companies. Instead of persuading the legislature, the accusation infuriated many of its members. The "dynamite squad", a caucus of opponents led by freshman lawmakers Cecil Morgan and

In 1929, Long called a special legislative session to enact a five-cent per barrel tax on refined oil production to fund his social programs. The state's oil interests opposed the bill. Long declared in a radio address that any legislator who refused to support the tax had been "bought" by oil companies. Instead of persuading the legislature, the accusation infuriated many of its members. The "dynamite squad", a caucus of opponents led by freshman lawmakers Cecil Morgan and

Long was unusual among southern populists in that he achieved tangible progress. Williams concluded "the secret of Long's power, in the final analysis, was not in his machine or his political dealings but in his record—he delivered something". Referencing Long's contributions to Louisiana,

Long was unusual among southern populists in that he achieved tangible progress. Williams concluded "the secret of Long's power, in the final analysis, was not in his machine or his political dealings but in his record—he delivered something". Referencing Long's contributions to Louisiana,

In March 1933, Long revealed a series of bills collectively known as "the Long plan" to redistribute wealth. Together, they would cap fortunes at $100 million, limit annual income to $1 million, and cap individual inheritances at $5 million. Williams (1981) 969 pp. 628–29.

In a nationwide February 1934 radio broadcast, Long introduced his Share Our Wealth plan. Kennedy (2005) 999 p. 238. The legislation would use the wealth from the Long plan to guarantee every family a basic household grant of $5,000 and a minimum annual income of one-third of the average family homestead value and income. Long supplemented his plan with proposals for free college and vocational training, veterans' benefits, federal assistance to farmers, public works projects, greater federal economic regulation, a $30 monthly elderly pension, a month's vacation for every worker, a thirty-hour

In March 1933, Long revealed a series of bills collectively known as "the Long plan" to redistribute wealth. Together, they would cap fortunes at $100 million, limit annual income to $1 million, and cap individual inheritances at $5 million. Williams (1981) 969 pp. 628–29.

In a nationwide February 1934 radio broadcast, Long introduced his Share Our Wealth plan. Kennedy (2005) 999 p. 238. The legislation would use the wealth from the Long plan to guarantee every family a basic household grant of $5,000 and a minimum annual income of one-third of the average family homestead value and income. Long supplemented his plan with proposals for free college and vocational training, veterans' benefits, federal assistance to farmers, public works projects, greater federal economic regulation, a $30 monthly elderly pension, a month's vacation for every worker, a thirty-hour

Popular support for Long's Share Our Wealth program raised the possibility of a 1936 presidential bid against incumbent Franklin D. Roosevelt. When questioned by the press, Long gave conflicting answers on his plans for 1936. Long's son Russell believed his father would have run on a

Popular support for Long's Share Our Wealth program raised the possibility of a 1936 presidential bid against incumbent Franklin D. Roosevelt. When questioned by the press, Long gave conflicting answers on his plans for 1936. Long's son Russell believed his father would have run on a

By 1935, Long's consolidation of power led to talk of armed opposition from his enemies in Louisiana. Opponents increasingly invoked the memory of the Battle of Liberty Place (1874), in which the White League staged an uprising against Louisiana's Reconstruction-era government. In January 1935, an anti-Long paramilitary organization called the Square Deal Association was formed. Its members included former governors John M. Parker and Ruffin Pleasant and New Orleans Mayor T. Semmes Walmsley. Hair (1996), pp. 298–300. Standard Oil threatened to leave the state when Long finally passed the five-cent-per-barrel oil tax for which he had been impeached in 1929. Concerned Standard Oil employees formed a Square Deal association in Baton Rouge, organizing themselves in militia companies and demanding "direct action". Kane (1971), pp. 112–13.

On January 25, 1935, these Square Dealers, now armed, seized the East Baton Rouge Parish courthouse. Long had Governor Allen execute emergency measures in Baton Rouge: he called in the

By 1935, Long's consolidation of power led to talk of armed opposition from his enemies in Louisiana. Opponents increasingly invoked the memory of the Battle of Liberty Place (1874), in which the White League staged an uprising against Louisiana's Reconstruction-era government. In January 1935, an anti-Long paramilitary organization called the Square Deal Association was formed. Its members included former governors John M. Parker and Ruffin Pleasant and New Orleans Mayor T. Semmes Walmsley. Hair (1996), pp. 298–300. Standard Oil threatened to leave the state when Long finally passed the five-cent-per-barrel oil tax for which he had been impeached in 1929. Concerned Standard Oil employees formed a Square Deal association in Baton Rouge, organizing themselves in militia companies and demanding "direct action". Kane (1971), pp. 112–13.

On January 25, 1935, these Square Dealers, now armed, seized the East Baton Rouge Parish courthouse. Long had Governor Allen execute emergency measures in Baton Rouge: he called in the

On September 8, 1935, Long traveled to the State Capitol to pass a bill that would gerrymander the district of an opponent, Judge Benjamin Pavy, who had held his position for 28 years. At 9:20 p.m., just after passage of the bill effectively removing Pavy, the judge's son-in-law,

On September 8, 1935, Long traveled to the State Capitol to pass a bill that would gerrymander the district of an opponent, Judge Benjamin Pavy, who had held his position for 28 years. At 9:20 p.m., just after passage of the bill effectively removing Pavy, the judge's son-in-law,

Long's assassination may have contributed to his reputation as a legendary figure in parts of Louisiana. In 1938, Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal encountered rural children who not only insisted Long was alive, but that he was president. Although no longer governing, Long's policies continued to be enacted in Louisiana by his political machine, which supported Roosevelt's re-election to prevent further investigation into their finances. The machine remained a powerful force in state politics until the 1960 elections. Within the Louisiana Democratic Party, Long set in motion two durable factions—"pro-Long" and "anti-Long"—which diverged meaningfully in terms of policies and voter support. For decades after his death, Long's political style inspired imitation among Louisiana politicians who borrowed his rhetoric and promises of social programs.

After Long's death, a Long family, family dynasty emerged: his brother Earl was elected lieutenant-governor in 1936 and governor in 1948 and 1956. Long's widow, Rose Long, replaced him in the Senate, and his son, Russell, was a U.S. senator from 1948 to 1987. As chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, Russell shaped the nation's tax laws, advocating low business taxes and passing legislation beneficial to the poor like the Earned Income Credit. Other relatives, including George S. Long, George, Gillis William Long, Gillis, and Speedy Long, Speedy, have represented Louisiana in Congress.

Huey P. Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party, was named after Long.

Long's assassination may have contributed to his reputation as a legendary figure in parts of Louisiana. In 1938, Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal encountered rural children who not only insisted Long was alive, but that he was president. Although no longer governing, Long's policies continued to be enacted in Louisiana by his political machine, which supported Roosevelt's re-election to prevent further investigation into their finances. The machine remained a powerful force in state politics until the 1960 elections. Within the Louisiana Democratic Party, Long set in motion two durable factions—"pro-Long" and "anti-Long"—which diverged meaningfully in terms of policies and voter support. For decades after his death, Long's political style inspired imitation among Louisiana politicians who borrowed his rhetoric and promises of social programs.

After Long's death, a Long family, family dynasty emerged: his brother Earl was elected lieutenant-governor in 1936 and governor in 1948 and 1956. Long's widow, Rose Long, replaced him in the Senate, and his son, Russell, was a U.S. senator from 1948 to 1987. As chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, Russell shaped the nation's tax laws, advocating low business taxes and passing legislation beneficial to the poor like the Earned Income Credit. Other relatives, including George S. Long, George, Gillis William Long, Gillis, and Speedy Long, Speedy, have represented Louisiana in Congress.

Huey P. Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party, was named after Long.

online

* Mann, Robert. ''Kingfish U: Huey Long and LSU'' (LSU Press, 2023

online

. * Mathy, Gabriel, and Nicolas L. Ziebarth. "How much does political uncertainty matter? The case of Louisiana under Huey Long." ''Journal of Economic History'' 77.1 (2017): 90-126

online

* * * * * * Seidemann, Ryan M. "Did the State Win or Lose in its Mineral Dealings with Huey Long, Oscar Allen, James Noe, and the Win or Lose Oil Company?" ''Louisiana History'' 59.2 (2018): 196-225

online

* * * * * *

Rich Lowry "Donald Trump is our Huey Long" ''Politico'' Aug 10, 2023

{{DEFAULTSORT:Long, Huey Huey Long, * 1893 births 1935 deaths 20th-century American lawyers American political bosses from Louisiana American anti-communists American social democrats American anti-poverty advocates American anti-war activists American nationalists Assassinated American politicians Assassinated national legislators Deaths by firearm in Louisiana Democratic Party United States senators from Louisiana Democratic Party governors of Louisiana History of United States isolationism Impeached state and territorial governors of the United States Left-wing populists Long family, Huey Louisiana lawyers Members of the Louisiana Public Service Commission Oklahoma Baptist University alumni People from Winnfield, Louisiana People murdered in Louisiana Tulane University Law School alumni Tulane University alumni University of Oklahoma alumni Politicians assassinated in the 1930s Left-wing populism in the United States 20th-century United States senators People murdered in 1935

United States senator

The United States Senate consists of 100 members, two from each of the 50 U.S. state, states. This list includes all senators serving in the 119th United States Congress.

Party affiliation

Independent Senators Angus King of Maine and Berni ...

from 1932 until his assassination in 1935. He was a left-wing populist

Left-wing populism, also called social populism, is a Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideology that combines left-wing politics with populist rhetoric and themes. Its rhetoric often includes elements of anti-elitism, opposition to the E ...

member of the Democratic Party and rose to national prominence during the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

for his vocal criticism of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

, which Long deemed insufficiently radical. As the political leader of Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

, he commanded wide networks of supporters and often took forceful action. A controversial figure, Long is celebrated as a populist champion of the poor or, conversely, denounced as a fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

demagogue

A demagogue (; ; ), or rabble-rouser, is a political leader in a democracy who gains popularity by arousing the common people against elites, especially through oratory that whips up the passions of crowds, Appeal to emotion, appealing to emo ...

.

Long was born in the impoverished north of Louisiana in 1893. After working as a traveling salesman and briefly attending three colleges, he was admitted to the bar

An admission to practice law is acquired when a lawyer receives a license to practice law. In jurisdictions with two types of lawyer, as with barristers and solicitors, barristers must gain admission to the bar whereas for solicitors there are dist ...

in Louisiana. Following a short career as an attorney, in which he frequently represented poor plaintiffs, Long was elected to the Louisiana Public Service Commission

The Louisiana Public Service Commission (LPSC) is an independent regulatory agency which manages public utilities and motor carriers in Louisiana. The Commission is established by Article IV, Section 21 of the 1921 Constitution of the State of ...

. As Commissioner, he prosecuted large corporations such as Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company was a Trust (business), corporate trust in the petroleum industry that existed from 1882 to 1911. The origins of the trust lay in the operations of the Standard Oil of Ohio, Standard Oil Company (Ohio), which had been founde ...

, a lifelong target of his rhetorical attacks. After hearing Long argue before the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

, Chief Justice and former president William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

praised him as "the most brilliant lawyer who ever practiced before the United States Supreme Court".

After a failed 1924 campaign, Long appealed to the sharp economic and class divisions in Louisiana to win the 1928 gubernatorial election. Once in office, he expanded social programs, organized massive public works projects, such as a modern highway system and the tallest capitol building in the nation, and proposed a cotton holiday. Through political maneuvering, Long became the political boss

In the politics of the United States of America, a boss is a person who controls a faction or local branch of a political party. They do not necessarily hold public office themselves; most historical bosses did not, at least during the times of th ...

of Louisiana. He was impeached

Impeachment is a process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In Eu ...

in 1929 for abuses of power, but the proceedings collapsed in the State Senate

In the United States, the state legislature is the legislative branch in each of the 50 U.S. states.

A legislature generally performs state duties for a state in the same way that the United States Congress performs national duties at ...

. His opponents argued his policies and methods were unconstitutional and authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in democracy, separation of powers, civil liberties, and ...

. At its climax, Long's political opposition organized a minor insurrection in 1935.

Long was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1930 but did not assume his seat until 1932. He established himself as an isolationist

Isolationism is a term used to refer to a political philosophy advocating a foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality an ...

, arguing that Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company was a Trust (business), corporate trust in the petroleum industry that existed from 1882 to 1911. The origins of the trust lay in the operations of the Standard Oil of Ohio, Standard Oil Company (Ohio), which had been founde ...

and Wall Street

Wall Street is a street in the Financial District, Manhattan, Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs eight city blocks between Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway in the west and South Street (Manhattan), South Str ...

orchestrated American foreign policy. He was instrumental in securing Franklin Roosevelt's 1932 presidential nomination, but split with him in 1933, becoming a prominent critic of his New Deal. As an alternative, he proposed the Share Our Wealth plan in 1934. To stimulate the economy, he advocated massive federal spending, a wealth tax

A wealth tax (also called a capital tax or equity tax) is a tax on an entity's holdings of assets or an entity's net worth. This includes the total value of personal assets, including cash, bank deposits, real estate, assets in insurance and ...

, and wealth redistribution

Redistribution of income and wealth is the transfer of income and wealth (including physical property) from some individuals to others through a social mechanism such as taxation, welfare, public services, land reform, monetary policies, confi ...

. These proposals drew widespread support, with millions joining local Share Our Wealth clubs. Poised for a 1936 presidential bid, Long was assassinated by Carl Weiss

Carl Austin Weiss Sr. (December 6, 1906 – September 8, 1935) was an American physician who assassinated U.S. Senator Huey Long at the Louisiana State Capitol on September 8, 1935.

Career

Weiss was born in Baton Rouge to physician Carl Ada ...

inside the Louisiana State Capitol in 1935. His assassin was immediately shot and killed by Long's bodyguards. Although Long's movement faded, Roosevelt adopted many of his proposals in the Second New Deal

The Second New Deal is a term used by historians to characterize the second stage, 1935–36, of the New Deal programs of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The most famous laws included the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act, the Banking Act, the ...

, and Louisiana politics would be organized along anti- or pro-Long factions until the 1960s. He left behind a political dynasty that included his wife, Senator Rose McConnell Long; his son, Senator Russell B. Long; and his brother, Governor Earl Long

Earl Kemp Long (August 26, 1895 – September 5, 1960) was an American politician who served as the List of governors of Louisiana, 45th governor of Louisiana on three occasions (1939–1940, 1948–1952, and 1956–1960). A member of the ...

, among others.

Early life (1893–1915)

Childhood

Huey Pierce Long Jr. was born on August 30, 1893, nearWinnfield

Winnfield is a small city in, and the parish seat of, Winn Parish, Louisiana, United States. The population was 5,749 at the 2000 census, and 4,840 in 2010. Three governors of the state of Louisiana were from Winnfield: Huey Long, Earl K. Long, ...

, a small town in north-central Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

, the seat of Winn Parish

Winn Parish is a parish located in the U.S. state of Louisiana. As of the 2020 census, the population was 13,755. The parish seat and largest city is Winnfield. The parish was founded in 1852. It is last in alphabetical order of Louisiana's s ...

. White (2006), p. 5. Although Long often told followers he was born in a log cabin

A log cabin is a small log house, especially a minimally finished or less architecturally sophisticated structure. Log cabins have an ancient history in Europe, and in America are often associated with first-generation home building by settl ...

to an impoverished family, they lived in a "comfortable" farmhouse and were well-off compared to others in Winnfield. Winn Parish was impoverished, and its residents, mostly Southern Baptists

The Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), alternatively the Great Commission Baptists (GCB), is a Christian denomination based in the United States. It is the world's largest Baptist organization, the largest Protestant, and the second-largest Ch ...

, were often outsiders in Louisiana's political system. During the Civil War, Winn Parish had been a stronghold of Unionism in an otherwise Confederate

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

state. At Louisiana's 1861 convention on secession

Secession is the formal withdrawal of a group from a Polity, political entity. The process begins once a group proclaims an act of secession (such as a declaration of independence). A secession attempt might be violent or peaceful, but the goal i ...

, the delegate from Winn voted to remain in the Union saying: "Who wants to fight to keep the Negroes for the wealthy planters?" In the 1890s, the parish was a bastion of the Populist Party Populist Party may refer to:

Asian and European political parties and movements

*Croatian Popular Party (1919), a Croatian right-wing party also known as Croatian Populist Party

* Indonesian National Populist Fortress Party, an Indonesian populist ...

, and in the 1912 election, Socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs

Eugene Victor Debs (November 5, 1855 – October 20, 1926) was an American socialist, political activist, trade unionist, one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and five-time candidate of the Socialist Party o ...

received 35% of the vote. Kennedy (2005) 999 p. 235. Long embraced these populist

Populism is a contested concept used to refer to a variety of political stances that emphasize the idea of the " common people" and often position this group in opposition to a perceived elite. It is frequently associated with anti-establis ...

sentiments. Kennedy (2005) 999 p. 236.

One of nine children, Long was home-schooled until age eleven. In the public system, he earned a reputation as an excellent student with a remarkable memory and convinced his teachers to let him skip

Skip or Skips may refer to:

Acronyms

* SKIP (Skeletal muscle and kidney enriched inositol phosphatase), a human gene

* Simple Key-Management for Internet Protocol

* SKIP of New York (Sick Kids need Involved People), a non-profit agency aiding ...

seventh grade. At Winnfield High School, he and his friends formed a secret society, advertising their exclusivity by wearing a red ribbon. According to Long, his club's mission was "to run things, laying down certain rules the students would have to follow". White (2006), p. 8. The faculty learned of Long's antics and warned him to obey the school's rules. Long continued to rebel, writing and distributing a flyer that criticized his teachers and the necessity of a recently state-mandated fourth year of secondary education, for which he was expelled in 1910. Although Long successfully petitioned to fire the principal, he never returned to high school. As a student, Long proved a capable debater. At a state debate competition in Baton Rouge

Baton Rouge ( ; , ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Louisiana. It had a population of 227,470 at the 2020 United States census, making it List of municipalities in Louisiana, Louisiana's second-m ...

, he won a full-tuition scholarship to Louisiana State University

Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, commonly referred to as Louisiana State University (LSU), is an American Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Baton Rouge, Louis ...

(LSU). Because the scholarship did not cover textbooks or living expenses, his family could not afford for him to attend. White (2006), pp. 122–23. Long was also unable to attend because he did not graduate from high school. Instead, he entered the workforce as a traveling salesman in the rural South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

.

Education and marriage

In September 1911, Long started attending seminary classes atOklahoma Baptist University

Oklahoma Baptist University (OBU) is a private Baptist university in Shawnee, Oklahoma. It was established in 1910 under the original name of The Baptist University of Oklahoma. OBU is owned and was founded by the Baptist General Convention of ...

at the urging of his mother, a devout Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

. Living with his brother George, Long attended for only one semester, rarely appearing at lectures. After deciding he was unsuited to preaching, Long focused on law. White (2006), p. 9. Borrowing one hundred dollars from his brother (which he later lost playing roulette in Oklahoma City

Oklahoma City (), officially the City of Oklahoma City, and often shortened to OKC, is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Oklahoma, most populous city of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The county seat ...

), he attended the University of Oklahoma College of Law

The University of Oklahoma College of Law is the law school of the University of Oklahoma. It is located on the University's campus in Norman, Oklahoma. The College of Law was founded in 1909 by a resolution of the OU Board of Regents.

Accordi ...

for a semester in 1912. To earn money while studying law part-time, he continued to work as a salesman. Of the four classes Long took, he received one incomplete and three C's. He later confessed he learned little because there was "too much excitement, all those gambling houses and everything".

Long met Rose McConnell at a baking contest he had promoted to sell Cottolene

Cottolene was a brand of shortening made of beef suet and cottonseed oil produced in the United States from the late 1880s until the mid-20th century. It was the first mass-produced and mass-marketed alternative to cooking with lard, and is remem ...

shortening. White (2006), pp. 10–11. The two began a two-and-a-half-year courtship and married in April 1913 at the Gayoso Hotel in Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in Shelby County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. Situated along the Mississippi River, it had a population of 633,104 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of municipalities in Tenne ...

. On their wedding day, Long had no cash with him and had to borrow $10 from his fiancée to pay the officiant

An officiant or celebrant is someone who officiates (i.e. leads) at a religious or secular service or ceremony, such as marriage ( marriage officiant), burial, namegiving or baptism.

Religious officiants, commonly referred to as celebrants, are ...

. White (2006), p. 11. Shortly after their marriage, Long revealed to his wife his aspirations to run for a statewide office, the governorship, the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, and ultimately the presidency. The Longs had a daughter named Rose (1917–2006) and two sons: Russell B. Long (1918–2003), who became a U.S. senator, and Palmer Reid Long (1921–2010), who became an oilman in Shreveport, Louisiana

Shreveport ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Louisiana. It is the List of municipalities in Louisiana, third-most populous city in Louisiana after New Orleans and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Baton Rouge. The bulk of Shreveport is in Caddo Parish, Lo ...

.

Long enrolled at Tulane University Law School

The Tulane University School of Law is the law school of Tulane University. It is located on Tulane's Uptown campus in New Orleans, Louisiana. Established in 1847, it is the 12th oldest law school in the United States.

Campus

The law schoo ...

in New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

in the fall of 1914. White (2006), pp. 9–11. After a year of study that concentrated on the courses necessary for the bar exam

A bar examination is an examination administered by the bar association of a jurisdiction that a lawyer must pass in order to be admitted to the bar of that jurisdiction.

Australia

Administering bar exams is the responsibility of the bar associat ...

, he successfully petitioned the Louisiana Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of Louisiana (; ) is the supreme court, highest court and court of last resort in the U.S. state of Louisiana. The modern Supreme Court, composed of seven justices, meets in the French Quarter of New Orleans.

The Supreme ...

for permission to take the test before its scheduled June 1915 date. He was examined in May, passed, and received his license to practice. White (2006), pp. 11–12. According to Long: "I came out of that courtroom running for office."

Legal career (1915–1923)

In 1915, Long established a private practice in Winnfield. He represented poor plaintiffs, usually inworkers' compensation

Workers' compensation or workers' comp is a form of insurance providing wage replacement and medical benefits to employees injured in the course of employment in exchange for mandatory relinquishment of the employee's right to sue his or her emp ...

cases. Brinkley (1983) 982 p. 14. Long avoided fighting in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

by obtaining a draft deferment on the grounds that he was married and had a dependent child. He successfully defended from prosecution under the Espionage Act of 1917

The Espionage Act of 1917 is a United States federal law enacted on June 15, 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I. It has been amended numerous times over the years. It was originally found in Title 50 of the U.S. Code ( ...

the state senator who had loaned him the money to complete his legal studies, and later claimed he did not serve because, "I was not mad at anybody over there." Brinkley (1983) 982 p. 17. In 1918, Long invested $1,050 () in a well that struck oil. The Standard Oil Company

Standard Oil Company was a corporate trust in the petroleum industry that existed from 1882 to 1911. The origins of the trust lay in the operations of the Standard Oil Company (Ohio), which had been founded in 1870 by John D. Rockefeller. The ...

refused to accept any of the oil in its pipelines, costing Long his investment. This episode served as the catalyst for Long's lifelong hatred of Standard Oil.

That same year, Long entered the race to serve on the three-seat Louisiana Railroad Commission. According to historian William Ivy Hair, Long's political message:

That same year, Long entered the race to serve on the three-seat Louisiana Railroad Commission. According to historian William Ivy Hair, Long's political message:

... would be repeated until the end of his days: he was a young warrior of and for the plain people, battling the evil giants of Wall Street and their corporations; too much of America's wealth was concentrated in too few hands, and this unfairness was perpetuated by an educational system so stacked against the poor that (according to his statistics) only fourteen out of every thousand children obtained a college education. The way to begin rectifying these wrongs was to turn out of office the corrupt local flunkies of big business ... and elect instead true men of the people, such as imselfIn the Democratic primary, Long polled second behind incumbent Burk Bridges. Since no candidate garnered a majority of the votes, a run-off election was held, for which Long campaigned tirelessly across northern Louisiana. The race was close: Long defeated Burk by just 636 votes. Although the returns revealed wide support for Long in rural areas, he performed poorly in urban areas. Hair (1996), p. 89. On the Commission, Long forced utilities to lower rates, ordered railroads to extend service to small towns, and demanded that Standard Oil cease the importation of Mexican crude oil and use more oil from Louisiana wells. White (2006), p. 48. Brinkley (1983) 982 p. 18. In the gubernatorial election of 1920, Long campaigned heavily for John M. Parker; today, he is often credited with helping Parker win northern

parishes

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or ...

. White (2006), p. 96. After Parker was elected, the two became bitter rivals. Their break was largely caused by Long's demand and Parker's refusal to declare the state's oil pipelines public utilities

A public utility company (usually just utility) is an organization that maintains the infrastructure for a public service (often also providing a service using that infrastructure). Public utilities are subject to forms of public control and r ...

. Long was infuriated when Parker allowed oil companies, led by Standard Oil's legal team, to assist in writing severance tax

Severance taxes are taxes imposed on the removal of natural resources within a taxing jurisdiction. Severance taxes are most commonly imposed in oil producing states within the United States. Resources that typically incur severance taxes when ...

laws. Long denounced Parker as corporate "chattel". The feud climaxed in 1921, when Parker tried unsuccessfully to have Long ousted from the commission.

By 1922, Long had become chairman of the commission, now called the "Public Service Commission". That year, Long prosecuted the Cumberland Telephone & Telegraph Company for unfair rate increases; he successfully argued the case on appeal before the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

, which resulted in cash refunds to thousands of overcharged customers. After the decision, Chief Justice and former President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

praised Long as "the most brilliant lawyer who ever practiced" before the court.

Gubernatorial campaigns (1924–1928)

1924 election

On August 30, 1923, Long announced his candidacy for the governorship of Louisiana. Long

On August 30, 1923, Long announced his candidacy for the governorship of Louisiana. Long stumped

Stumped is a method of Dismissal (cricket), dismissing a batter (cricket), batter in cricket, in which the wicket-keeper put down the wicket, puts down the wicket of the Glossary_of_cricket_terms#S, striker while the striker is out of their Bat ...

throughout the state, personally distributing circulars and posters. He denounced Governor Parker as a corporate stooge, vilified Standard Oil, and assailed local political bosses. Brinkley (1983) 982 p. 19.

He campaigned in rural areas disenfranchised by the state's political establishment, the " Old Regulars". Since the 1877 end of Republican-controlled Reconstruction government, they had controlled most of the state through alliances with local officials. With negligible support for Republicans, Louisiana was essentially a one party state under the Democratic Old Regulars. Holding mock elections in which they invoked the Lost Cause of the Confederacy

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy, known simply as the Lost Cause, is an American pseudohistory, pseudohistorical and historical negationist myth that argues the cause of the Confederate States of America, Confederate States during the America ...

, the Old Regulars presided over a corrupt government that largely benefited the planter class

The planter class was a Racial hierarchy, racial and socioeconomic class which emerged in the Americas during European colonization of the Americas, European colonization in the early modern period. Members of the class, most of whom were settle ...

. Kane (1971), pp. 29–30. Consequently, Louisiana was one of the least developed states: It had just 300 miles of paved roads and the lowest literacy rate.

Despite an enthusiastic campaign, Long came third in the primary and was eliminated. Although polls projected only a few thousand votes, he attracted almost 72,000, around 31% of the electorate, and carried 28 parishes—more than either opponent. Limited to sectional appeal, he performed best in the poor rural north.

The Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

's prominence in Louisiana was the campaign's primary issue. While the two other candidates either strongly opposed or supported the Klan, Long remained neutral, alienating both sides. He also failed to attract Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

voters, which limited his chances in the south of the state. In majority Catholic New Orleans, he polled just 12,000 votes (17%). Long blamed heavy rain on election day for suppressing voter turnout among his base in the north, where voters could not reach the polls over dirt roads that had turned to mud. It was the only election Long ever lost.

1928 election

Long spent the intervening four years building his reputation and political organization, particularly in the heavily Catholic urban south. Despite disagreeing with their politics, Long campaigned for Catholic U.S. Senators in 1924 and 1926. Government mismanagement during theGreat Mississippi Flood of 1927

The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 was the most destructive river flood in the history of the United States, with inundated in depths of up to over the course of several months in early 1927. The period cost of the damage has been estimate ...

gained Long the support of Cajuns

The Cajuns (; Louisiana French language, French: ''les Cadjins'' or ''les Cadiens'' ), also known as Louisiana ''Acadians'' (French: ''les Acadiens''), are a Louisiana French people, Louisiana French ethnic group, ethnicity mainly found in t ...

, whose land had been affected. He formally launched his second campaign for governor in 1927, using the slogan, "Every man a king, but no one wears a crown", a phrase adopted from Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator, and politician. He was a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running three times as the party' ...

.

Long developed novel campaign techniques, including the use of sound trucks and radio commercials. His stance on race was unorthodox. According to T. Harry Williams, Long was "the first Southern mass leader to leave aside race baiting and appeals to the Southern tradition and the Southern past and address himself to the social and economic problems of the present". Jeansonne (1992), p. 265. The campaign sometimes descended into brutality. When the 60-year-old incumbent governor called Long a liar during a chance encounter in the lobby of the Roosevelt Hotel, Long punched him in the face.

In the Democratic primary election, Long polled 126,842 votes: a plurality of 43.9 percent. His margin was the largest in state history, and no opponent chose to face him in a runoff. After earning the Democratic nomination, he easily defeated the Republican nominee in the general election with 96.1 percent of the vote.

Some fifteen thousand Louisianians traveled to Baton Rouge for Long's inauguration. He set up large tents, free drinks, and jazz bands on the capitol grounds, evoking Andrew Jackson's 1829 inaugural festivities. His victory was seen as a public backlash against the urban establishment; journalist Hodding Carter

William Hodding Carter II (February 3, 1907 – April 4, 1972) was an American progressive journalist and author. Among other distinctions in his career, Carter was a Nieman Fellow and Pulitzer Prize winner. He died in Greenville, Mississippi, ...

described it as a "fantastic vengeance upon the Sodom and Gomorrah

In the Abrahamic religions, Sodom and Gomorrah () were two cities destroyed by God for their wickedness. Sodom and Gomorrah are repeatedly invoked throughout the Hebrew Bible, Deuterocanonical texts, and the New Testament as symbols of sin, di ...

that was called New Orleans". While previous elections were normally divided culturally and religiously, Long highlighted the sharp economic divide in the state and built a new coalition based on class. Brinkley (1983) 982 p. 21. Long's strength, said the contemporary novelist Sherwood Anderson

Sherwood Anderson (September 13, 1876 – March 8, 1941) was an American novelist and short story writer, known for subjective and self-revealing works. Self-educated, he rose to become a successful copywriter and business owner in Cleveland and ...

, relied on "the terrible South ... the beaten, ignorant, Bible-ridden, white South. Faulkner

William Cuthbert Faulkner (; September 25, 1897 – July 6, 1962) was an American writer. He is best known for his novels and short stories set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi, a stand-in for Lafayette County where he s ...

occasionally really touches it. It has yet to be paid for."

Louisiana governorship (1928–1932)

First year

Once in office on May 21, 1928, Long moved quickly to consolidate power, firing hundreds of opponents in the state bureaucracy at all ranks from cabinet-level heads of departments to state road workers. Like previous governors, he filled the vacancies with patronage appointments from his network of political supporters. Every state employee who depended on Long for a job was expected to pay a portion of their salary at election time directly into his campaign fund. Once his control over the state's political apparatus was strengthened, Long pushed several bills through the 1929 session of theLouisiana State Legislature

The Louisiana State Legislature (; ) is the state legislature (United States), state legislature of the U.S. state of Louisiana. It is a bicameral legislature, body, comprising the lower house, the Louisiana House of Representatives with 105 ...

to fulfill campaign promises. His bills met opposition from legislators, wealthy citizens, and the media, but Long used aggressive tactics to ensure passage. He would appear unannounced on the floor of both the House

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air c ...

and Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

or in House committees, corralling reluctant representatives and state senators and bullying opponents. When an opposing legislator once suggested Long was unfamiliar with the Louisiana Constitution

The Louisiana Constitution is legally named the Constitution of the State of Louisiana and commonly called the Louisiana Constitution of 1974, and the Constitution of 1974. The constitution is the cornerstone of the law of Louisiana ensuring the ...

, he declared, "I'm the Constitution around here now."

One program Long approved was a free textbook program for schoolchildren. Long's free school books angered Catholics, who usually sent their children to private schools. Long assured them that the books would be granted directly to all children, regardless of whether they attended public school. Yet this assurance was criticized by conservative constitutionalists

Constitutionalism is "a compound of ideas, attitudes, and patterns of behavior elaborating the principle that the authority of government derives from and is limited by a body of fundamental law".

Political organizations are constitutional to ...

, who claimed it violated the separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and Jurisprudence, jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the State (polity), state. Conceptually, the term refers to ...

and sued Long. The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in Long's favor.

Irritated by "immoral" gambling dens and brothels in New Orleans, Long sent the National Guard

National guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

...

to raid these establishments with orders to "shoot without hesitation". Gambling equipment was burned, prostitutes were arrested, and over $25,000 () was confiscated for government funds. Local newspapers ran photos of National Guardsmen forcibly searching nude women. City authorities had not requested military force, and martial law had not been declared. The Louisiana attorney general denounced Long's actions as illegal but Long rebuked him, saying: "Nobody asked him for his opinion."

Despite wide disapproval, Long had the Governor's Mansion, built in 1887, razed by convicts from the State Penitentiary under his personal supervision. In its place, Long had a much larger Georgian mansion built. It bore a strong resemblance to the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

; he reportedly wanted to be familiar with the residence when he became president.

Impeachment

In 1929, Long called a special legislative session to enact a five-cent per barrel tax on refined oil production to fund his social programs. The state's oil interests opposed the bill. Long declared in a radio address that any legislator who refused to support the tax had been "bought" by oil companies. Instead of persuading the legislature, the accusation infuriated many of its members. The "dynamite squad", a caucus of opponents led by freshman lawmakers Cecil Morgan and

In 1929, Long called a special legislative session to enact a five-cent per barrel tax on refined oil production to fund his social programs. The state's oil interests opposed the bill. Long declared in a radio address that any legislator who refused to support the tax had been "bought" by oil companies. Instead of persuading the legislature, the accusation infuriated many of its members. The "dynamite squad", a caucus of opponents led by freshman lawmakers Cecil Morgan and Ralph Norman Bauer

Ralph Norman Bauer, sometimes known as R. Norman Bauer (May 1899 - March 13, 1963), was a lawyer from Franklin in St. Mary Parish, Louisiana, who served as a Democratic member of the Louisiana House of Representatives from 1928 to 1936 and a ...

, introduced an impeachment

Impeachment is a process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In Eur ...

resolution against Long. Kane (1971), p. 71. Nineteen charges were listed, ranging from blasphemy

Blasphemy refers to an insult that shows contempt, disrespect or lack of Reverence (emotion), reverence concerning a deity, an object considered sacred, or something considered Sanctity of life, inviolable. Some religions, especially Abrahamic o ...

to subornation of murder. Even Long's lieutenant governor, Paul Cyr, supported impeachment; he accused Long of nepotism

Nepotism is the act of granting an In-group favoritism, advantage, privilege, or position to Kinship, relatives in an occupation or field. These fields can include business, politics, academia, entertainment, sports, religion or health care. In ...

and alleged he had made corrupt deals with a Texas oil company. White (2006), p. 65.

Concerned, Long tried to close the session. Pro-Long Speaker John B. Fournet called for a vote to adjourn. Despite most representatives opposing adjournment, the electronic voting board tallied 68 ayes and 13 nays. This sparked confusion; anti-Long representatives began chanting that the voting machine had been rigged. Some ran for the speaker's chair to call for a new vote but met resistance from their pro-Long colleagues, sparking a brawl later known as "Bloody Monday". In the scuffle, legislators threw inkwells

An inkwell is a small jar or container, often made of glass, porcelain, silver, brass, or pewter, used for holding ink in a place convenient for the person who is writing. The artist or writer dips the brush, quill, or dip pen into the inkwell ...

, allegedly attacked others with brass knuckles

Brass knuckles (also referred to as brass knucks, knuckledusters, iron fist and paperweight, among other names) are a melee weapon used primarily in Hand to hand combat, hand-to-hand combat. They are fitted and designed to be worn around the kn ...

, and Long's brother Earl bit a legislator's neck. Brinkley (1983) 982 p. 25. Following the fight, the legislature voted to remain in session and proceed with impeachment. Proceedings in the house took place with dozens of witnesses, including a hula

Hula () is a Hawaiian dance form expressing chant (''oli'') or song (Mele (Hawaiian language), ''mele''). It was developed in the Hawaiian Islands by the Native Hawaiians who settled there. The hula dramatizes or portrays the words of the oli ...

dancer who claimed that Long had been "frisky" with her. Impeached on eight of the 19 charges, Long was the third Louisiana governor charged in the state's history, following Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

Republicans

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Henry Clay Warmoth

Henry Clay Warmoth (May 9, 1842 – September 30, 1931) was an American attorney and veteran Civil War officer in the Union Army who was elected governor and state representative of Louisiana. A Republican, he was 26 years old when elected as Lis ...

and William Pitt Kellogg

William Pitt Kellogg (December 8, 1830 – August 10, 1918) was an American lawyer and Republican Party (United States), Republican Party politician who served as the governor of Louisiana from 1873 to 1877 and twice served as a United States Sen ...

.

Long was frightened by the prospect of conviction, for it would force him from the governorship and permanently disqualify him from holding public office in Louisiana. He took his case to the people with a mass meeting in Baton Rouge, where he alleged that impeachment was a ploy by Standard Oil to thwart his programs. The House referred the charges to the Louisiana Senate, in which conviction required a two-thirds majority. Long produced a round robin statement signed by fifteen senators pledging to vote "not guilty" regardless of the evidence. The impeachment process, now futile, was suspended without holding an impeachment trial

An impeachment trial is a trial that functions as a component of an impeachment. Several governments utilize impeachment trials as a part of their processes for impeachment. Differences exist between governments as to what stage trials take place ...

. It has been alleged that both sides used bribes to buy votes and that Long later rewarded the round robin signers with positions or other favors.

Following the failed impeachment attempt, Long treated his opponents ruthlessly. He fired their relatives from state jobs and supported their challengers in elections. Long concluded that extra-legal means would be needed to accomplish his goals: "I used to try to get things done by saying 'please.' Now... I dynamite 'em out of my path." Receiving death threats, he surrounded himself with bodyguards. Hamby (2004), p. 263. Now a resolute critic of the "lying" press, Brinkley (1983) 982 p. 26. Long established his own newspaper in March 1930: the '' Louisiana Progress''. The paper was extremely popular, widely distributed by policemen, highway workers, and government truckers.

Senate campaign

Shortly after the impeachment, Long—now nicknamed "The Kingfish" after an ''Amos 'n' Andy

''Amos 'n' Andy'' was an American radio sitcom about black characters, initially set in Chicago then later in the Harlem section of New York City. While the show had a brief life on 1950s television with black actors, the 1928 to 1960 radio sho ...

'' character—announced his candidacy for the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and House have the authority under Article One of the ...

in the 1930 Democratic primary. He framed his campaign as a referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

. If he won, he presumed the public supported his programs over the opposition of the legislature. If he lost, he promised to resign.

His opponent was incumbent Joseph E. Ransdell, the Catholic senator whom Long endorsed in 1924. Jeansonne (1989), p. 287. At 72 years old, Ransdell had served in the U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a bicameral legislature, including a lower body, the U.S. House of Representatives, and an upper body, the U.S. Senate. They both ...

since Long was aged six. Aligned with the establishment, Ransdell had the support of all 18 of the state's daily newspapers. To combat this, Long purchased two new $30,000 sound trucks and distributed over two million circulars. Although promising not to make personal attacks, Long seized on Ransdell's age, calling him "Old Feather Duster". Kane (1971), p. 107. The campaign became increasingly vicious, with ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' calling it "as amusing as it was depressing". Long critic Sam Irby, set to testify on Long's corruption to state authorities, was abducted by Long's bodyguards shortly before the election. Irby emerged after the election; he had been missing for four days. Surrounded by Long's guards, he gave a radio address in which he "confessed" that he had actually asked Long for protection. The New Orleans mayor labelled it "the most heinous public crime in Louisiana history".

Ultimately, on September 9, 1930, Long defeated Ransdell by 149,640 (57.3 percent) to 111,451 (42.7 percent). Brinkley (1983) 982 p. 29. There were accusations of voter fraud against Long; voting records showed people voting in alphabetical order, among them celebrities like Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is considered o ...

, Jack Dempsey

William Harrison "Jack" Dempsey (June 24, 1895 – May 31, 1983), nicknamed Kid Blackie and The Manassa Mauler, was an American boxer who competed from 1914 to 1927, and world heavyweight champion from 1919 to 1926.

One of the most iconic athl ...

and Babe Ruth

George Herman "Babe" Ruth (February 6, 1895 – August 16, 1948) was an American professional Baseball in the United States, baseball player whose career in Major League Baseball (MLB) spanned 22 seasons, from 1914 through 1935. Nickna ...

.

Although his Senate term began on March 4, 1931, Long completed most of his four-year term as governor, which did not end until May 1932. He declared that leaving the seat vacant would not hurt Louisiana: " th Ransdell as Senator, the seat was vacant anyway." By occupying the governorship until January 25, 1932, Long prevented Lieutenant Governor Cyr, who threatened to undo Long's reforms, from succeeding to the office. In October 1931, Cyr learned Long was in Mississippi and declared himself the state's legitimate governor. In response, Long ordered National Guard troops to surround the Capitol to block Cyr's "coup d'état" and petitioned the Louisiana Supreme Court. Hair (1996), pp. 221–22. Long successfully argued that Cyr had vacated the office of lieutenant-governor when trying to assume the governorship and had the court eject Cyr.

Before becoming a senator, Long ensured that his successor as governor would not only continue his reforms, but that he had a friendly legislature to work with. Long was successful in this, as noted by one historian:

Senator-elect

Now governor and senator-elect, Long returned to completing his legislative agenda with renewed strength. He continued his intimidating practice of presiding over the legislature, shouting "Shut up!" or "Sit down!" when legislators voiced their concerns. In a single night, Long passed 44 bills in just two hours: one every three minutes. He later explained his tactics: "The end justifies the means

In moral philosophy, consequentialism is a class of normative, teleological ethical theories that holds that the consequences of one's conduct are the ultimate basis for judgement about the rightness or wrongness of that conduct. Thus, from a c ...

." Brinkley (1983) 982 p. 28. Long endorsed pro-Long candidates and wooed others with favors; he often joked his legislature was the "finest collection of lawmakers money can buy". He organized and concentrated his power into a political machine

In the politics of representative democracies, a political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives (such as money or political jobs) and that is characterized by a high degree of leadership c ...

: "a one-man" operation, according to Williams. He placed his brother Earl in charge of allotting patronage appointments to local politicians and signing state contracts with businessmen in exchange for loyalty. Long appointed allies to key government positions, such as giving Robert Maestri

Robert Sidney Maestri (December 11, 1899 – May 6, 1974) was mayor of New Orleans from 1936 to 1946 and a key ally of Huey P. Long Jr. and Earl Kemp Long.

Early life

Robert Maestri was born in New Orleans on December 11, 1899, the son of Fra ...

the office of Conservation Commissioner and making Oscar K. Allen head of the Louisiana Highway Commission

The Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development (DOTD) is a state government organization in the United States, in charge of maintaining public transportation, roadways, bridges, canals, select levees, floodplain management, port faci ...

. Maestri would deliberately neglect the regulation of energy companies in exchange for industry donations to Long's campaign fund, while Allen took direction from Earl on which construction and supply companies to contract for road work. Concerned by these tactics, Long's opponents charged he had become the virtual dictator of the state.

To address record low cotton prices amid a Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

surplus, Long proposed the major cotton-producing states mandate a 1932 " cotton holiday", which would ban cotton production for the entire year. He further proposed that the holiday be imposed internationally, which some nations, such as Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, supported. In 1931, Long convened the New Orleans Cotton Conference, attended by delegates from every major cotton-producing state. The delegates agreed to codify Long's proposal into law on the caveat that it would not come into effect until states producing three-quarters of U.S. cotton passed such laws. As the proposer, Louisiana unanimously passed the legislation. When conservative politicians in Texas—the largest cotton producer in the U.S.—rejected the measure, the holiday movement collapsed. Although traditional politicians would have been ruined by such a defeat, Long became a national figure and cemented his image as a champion of the poor. Senator Carter Glass

Carter Glass (January 4, 1858 – May 28, 1946) was an American newspaper publisher and Democratic Party (United States), Democratic politician from Lynchburg, Virginia, Lynchburg, Virginia. He represented Virginia in both houses of United Stat ...

, although a fervid critic of Long, credited him with first suggesting artificial scarcity

Artificial scarcity is scarcity of items despite the technology for production or the sufficient capacity for sharing. The most common causes are monopoly pricing structures, such as those enabled by laws that restrict competition or by high f ...

as a solution to the depression.

Accomplishments

Long was unusual among southern populists in that he achieved tangible progress. Williams concluded "the secret of Long's power, in the final analysis, was not in his machine or his political dealings but in his record—he delivered something". Referencing Long's contributions to Louisiana,

Long was unusual among southern populists in that he achieved tangible progress. Williams concluded "the secret of Long's power, in the final analysis, was not in his machine or his political dealings but in his record—he delivered something". Referencing Long's contributions to Louisiana, Robert Penn Warren

Robert Penn Warren (April 24, 1905 – September 15, 1989) was an American poet, novelist, literary critic and professor at Yale University. He was one of the founders of New Criticism. He was also a charter member of the Fellowship of Southern ...

, a professor at LSU during Long's term as governor, stated: "Dictators, always give something for what they get." Sanson (2006), p. 273.

Long created a public works program that was unprecedented in the South, constructing roads, bridges, hospitals, schools, and state buildings. During his four years as governor, Long increased paved highways in Louisiana from and constructed of gravel roads. By 1936, the infrastructure program begun by Long had completed some of new roads, doubling Louisiana's road system. He built 111 bridges and started construction on the first bridge over the Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

entirely in Louisiana, the Huey P. Long Bridge. These projects provided thousands of jobs during the depression: Louisiana employed more highway workers than any other state. Long built a State Capitol

A capitol, or seat of government, is the building or complex of buildings from which a government such as that of a U.S. state, the District of Columbia, or the organized territories of the United States, exercises its authority. Although m ...

, which at tall remains the tallest capitol, state or federal, in the United States. Long's infrastructure spending increased the state government's debt from $11 million in 1928 to $150 million in 1935.

Long was an ardent supporter of the state's flagship public university, Louisiana State University

Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, commonly referred to as Louisiana State University (LSU), is an American Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Baton Rouge, Louis ...

(LSU). Having been unable to attend, Long now regarded it as "his" university. He increased LSU's funding and intervened in the university's affairs, expelling seven students who criticized him in the school newspaper

A student publication is a media outlet such as a newspaper, magazine, television show, or radio station Graduate student journal, produced by students at an educational institution. These publications typically cover local and school-related new ...

. He constructed new buildings, including a fieldhouse that reportedly contained the longest pool in the United States. Brinkley (1983) 982 p. 30. Long founded an LSU Medical School in New Orleans. Jeansonne (1989), p. 294. To raise the stature of the football program, he converted the school's military marching band into the flashy " Show Band of the South" and hired Costa Rican

Costa Rica, officially the Republic of Costa Rica, is a country in Central America. It borders Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the northeast, Panama to the southeast, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest, as well as Maritime bo ...

composer Castro Carazo as the band director. As well as nearly doubling the size of the stadium, he arranged for lowered train fares, so students could travel to away games. Long's contributions resulted in LSU gaining a class A accreditation from the Association of American Universities

The Association of American Universities (AAU) is an organization of predominantly American research universities devoted to maintaining a strong system of academic research and education. Founded in 1900, it consists of 69 public and private ...

.

Long's night schools taught 100,000 adults to read. His provision of free textbooks contributed to a 20-percent increase in school enrollment. He modernized public health facilities and ensured adequate conditions for the mentally ill. He established Louisiana's first rehabilitation program for penitentiary inmates. Through tax reform, Long made the first $2,000 in property assessment free, waiving property taxes

A property tax (whose rate is expressed as a percentage or per mille, also called ''millage'') is an ad valorem tax on the value of a property.In the OECD classification scheme, tax on property includes "taxes on immovable property or net we ...

for half the state's homeowners. Several labor laws were also enacted during Long's time as governor. Some historians have criticized other policies, like high consumer taxes on gasoline and cigarettes, a reduced mother's pension, and low teacher salaries.

U.S. Senate (1932–1935)

Senator

When Long arrived in the Senate, America was in the throes of theGreat Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

. With this backdrop, Long made characteristically fiery speeches that denounced wealth inequality

The distribution of wealth is a comparison of the wealth of various members or groups in a society. It shows one aspect of economic inequality or economic heterogeneity.

The distribution of wealth differs from the income distribution in that ...

. He criticized the leaders of both parties for failing to address the crisis adequately, notably attacking Senate Democratic Leader Joseph Robinson of Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

for his apparent closeness with President Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

and big business.

In the 1932 presidential election, Long was a vocal supporter of New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

. At that year's Democratic National Convention, Long kept the delegations of several wavering Southern states in the Roosevelt camp. Due to this, Long expected to be featured prominently in Roosevelt's campaign but was disappointed with a peripheral speaking tour limited to four Midwestern

The Midwestern United States (also referred to as the Midwest, the Heartland or the American Midwest) is one of the four census regions defined by the United States Census Bureau. It occupies the northern central part of the United States. It ...

states. Williams (1981) 969 pp. 600–03.

Not discouraged after being snubbed, Long found other venues for his populist message. He endorsed Senator Hattie Caraway

Hattie Ophelia Wyatt Caraway (February 1, 1878 – December 21, 1950) was an American politician who was United States Senator from Arkansas from 1931 to 1945. She was the first woman elected to the Senate, the first woman to serve a full term as ...

of Arkansas, a widow and the underdog candidate in a crowded field and conducted a whirlwind, seven-day tour of that state. Williams (1981) 969 pp. 583–93. Brinkley (1983) 982 pp. 48–49. During the campaign, Long gave 39 speeches, traveled , and spoke to over 200,000 people. In an upset win, Caraway became the first woman elected to a full term in the Senate.

Returning to Washington, Long gave theatrical speeches which drew wide attention. Public viewing areas were crowded with onlookers, among them a young Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

, who later said he was "simply entranced" by Long. Long obstructed bills for weeks, launching hour-long filibusters and having the clerk read superfluous documents. Long's antics, one editorial claimed, had made the Senate "impotent". Brinkley (1983) 982 p. 55. In May 1932, ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'', locally known as ''The'' ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'' or ''WP'', is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C., the national capital. It is the most widely circulated newspaper in the Washington m ...

'' called for his resignation. Long's behavior and radical rhetoric did little to endear him to his fellow senators. None of his proposed bills, resolutions, or motions were passed during his three years in the Senate.

Roosevelt and the New Deal

During the first 100 days of Roosevelt's presidency in spring 1933, Long's attitude toward Roosevelt and theNew Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

was tepid. Aware that Roosevelt had no intention of radically redistributing the country's wealth, Long became one of the few national politicians to oppose Roosevelt's New Deal policies from the left. He considered them inadequate in the face of the escalating economic crisis but still supported some of Roosevelt's programs in the Senate, explaining: "Whenever this administration has gone to the left I have voted with it, and whenever it has gone to the right I have voted against it."

Long opposed the National Recovery Act

The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 (NIRA) was a US labor law and consumer law passed by the 73rd US Congress to authorize the president to regulate industry for fair wages and prices that would stimulate economic recovery. It also ...

, claiming it favored industrialists. In an attempt to prevent its passage, Long held a lone filibuster, speaking for 15 hours and 30 minutes, the second longest filibuster at the time. He also criticized Social Security

Welfare spending is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifically to social insurance ...

, calling it inadequate and expressing his concerns that states would administer it in a way discriminatory to African Americans. In 1933, he was a leader of a three-week Senate filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent a decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking ...

against the Glass banking bill, which he later supported as the Glass–Steagall Act after provisions extended government deposit insurance to state banks as well as national banks.