Howland Island on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

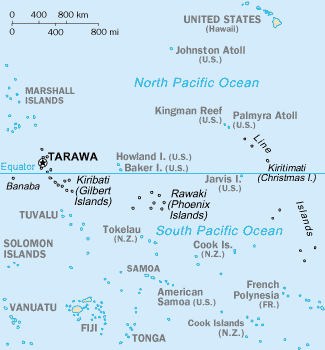

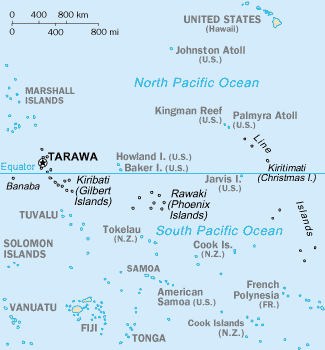

Howland Island () is a coral island and

strict nature reserve

A strict nature reserve (IUCN category Ia) or wilderness area (IUCN category Ib) is the highest category of protected area recognised by the World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA), a body which is part of the International Union for ...

located just north of the equator

The equator is the circle of latitude that divides Earth into the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Southern Hemisphere, Southern Hemispheres of Earth, hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, about in circumferen ...

in the central Pacific Ocean, about southwest of Honolulu

Honolulu ( ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, located in the Pacific Ocean. It is the county seat of the Consolidated city-county, consolidated City and County of Honol ...

. The island lies almost halfway between Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

and Australia and is an unincorporated, unorganized territory of the United States. Together with Baker Island, it forms part of the Phoenix Islands

The Phoenix Islands, or Rawaki, are a group of eight atolls and two submerged coral reefs that lie east of the Gilbert Islands and west of the Line Islands in the central Pacific Ocean, north of Samoa. They are part of the Kiribati, Republic ...

. For statistical purposes, Howland is grouped as one of the United States Minor Outlying Islands

The United States Minor Outlying Islands is a statistical designation applying to the minor outlying islands and groups of islands that comprise eight United States insular areas in the Pacific Ocean (Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Isla ...

. The island has an elongated cucumber

The cucumber (''Cucumis sativus'') is a widely-cultivated creeping vine plant in the family Cucurbitaceae that bears cylindrical to spherical fruits, which are used as culinary vegetables.

Howland Island National Wildlife Refuge consists of the entire island and the surrounding of submerged land. The island is managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as an

The U.S. claims an

The U.S. claims an

Howland Island was claimed by the United States in 1856 and was mined for

Howland Island was claimed by the United States in 1856 and was mined for

However, when the United States Guano Company dispatched a vessel in 1859 to mine the guano, they found that Howland Island was already occupied by men sent there by the American Guano Company. The companies ended up in New York state court, with the American Guano Company arguing that the United States Guano Company had, in effect, abandoned the island since the continual possession and actual occupation required for ownership by the Guano Islands Act did not occur. The result was that both companies were allowed to mine the guano deposits, which were substantially depleted by October1878. Laborers for the mining operations came from around the Pacific, including from Hawaii; the Hawaiian laborers named Howland Island ('kou tree grove'). Established in 1861, the Pacific Guano Company purchased Howland Island to provide a source of guano for its fertilizer plant.

In the late 19th century, British claims were made on the island, and attempts were made to set up mining.

However, when the United States Guano Company dispatched a vessel in 1859 to mine the guano, they found that Howland Island was already occupied by men sent there by the American Guano Company. The companies ended up in New York state court, with the American Guano Company arguing that the United States Guano Company had, in effect, abandoned the island since the continual possession and actual occupation required for ownership by the Guano Islands Act did not occur. The result was that both companies were allowed to mine the guano deposits, which were substantially depleted by October1878. Laborers for the mining operations came from around the Pacific, including from Hawaii; the Hawaiian laborers named Howland Island ('kou tree grove'). Established in 1861, the Pacific Guano Company purchased Howland Island to provide a source of guano for its fertilizer plant.

In the late 19th century, British claims were made on the island, and attempts were made to set up mining.

Ground was cleared for a rudimentary aircraft landing area during the mid-1930s in anticipation that the island might eventually become a stopover for commercial trans-Pacific air routes and also to further U.S. territorial claims in the region against rival claims from Great Britain. Howland Island was designated as a scheduled refueling stop for American pilot

Ground was cleared for a rudimentary aircraft landing area during the mid-1930s in anticipation that the island might eventually become a stopover for commercial trans-Pacific air routes and also to further U.S. territorial claims in the region against rival claims from Great Britain. Howland Island was designated as a scheduled refueling stop for American pilot

On June 27, 1974, Secretary of the Interior

On June 27, 1974, Secretary of the Interior

File:Plane wreckage on Howland Island.jpg, Aircraft wreckage on Howland

File:Howland Itascatown.jpg, Itascatown settlement remains

File:Groundcover.jpg, Howland Island flora

File:Howland Flora.jpg, Howland Island flora (

"Eyewitness account of the Japanese raids on Howland Island (includes a grainy photo of Itascatown)."

''ksbe.edu.'' Retrieved: October 10, 2010. * * * * * *

Howland Island National Wildlife Refuge

– U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Geography, history and nature on Howland Island

*

{{Authority control , additional=Q20932641 Coral islands Uninhabited Pacific islands of the United States Amelia Earhart Works Progress Administration National Wildlife Refuges in the United States insular areas Important Bird Areas of United States Minor Outlying Islands Important Bird Areas of Oceania Seabird colonies

insular area

In the law of the United States, an insular area is a U.S.-associated jurisdiction that is not part of a U.S. state or the Washington, D.C., District of Columbia. This includes fourteen Territories of the United States, U.S. territories adminis ...

under the U.S. Department of the Interior. It is part of the Pacific Islands Heritage Marine National Monument.

The atoll currently has no economic activity

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Microeconomics analyse ...

. It is managed as a nature reserve. It is best known as the island Amelia Earhart

Amelia Mary Earhart ( ; July 24, 1897 – January 5, 1939) was an American aviation pioneer. On July 2, 1937, she disappeared over the Pacific Ocean while attempting to become the first female pilot to circumnavigate the world. During her li ...

and Fred Noonan were searching for but failed to find when they and their airplane disappeared on , during their planned round-the-world flight. Airstrips constructed to accommodate her planned stopover were subsequently damaged in World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, not maintained, and gradually disappeared. There are no harbors or docks. The fringing reef

A fringing reef is one of the three main types of coral reef. It is distinguished from the other main types, barrier reefs and atolls, in that it has either an entirely shallow backreef zone (lagoon) or none at all. If a fringing reef grows direc ...

s may pose a maritime hazard. There is a boat landing area along the middle of the sandy beach on the west coast and a crumbling day beacon. The island is visited every two years by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. It was mined for guano

Guano (Spanish from ) is the accumulated excrement of seabirds or bats. Guano is a highly effective fertiliser due to the high content of nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium, all key nutrients essential for plant growth. Guano was also, to a le ...

in the 19th century, and in the 1930s it was colonized by the American Equatorial Islands Colonization Project. In modern times, it is a nature reserve, and there are some historical remains from the colony and a stone tower called Earhart Light.

Flora and fauna

The climate is equatorial, with little rainfall and intense sunshine. Temperatures are moderated somewhat by a constant wind from the east. The terrain is low-lying and sandy: a coral island surrounded by a narrow fringingreef

A reef is a ridge or shoal of rock, coral, or similar relatively stable material lying beneath the surface of a natural body of water. Many reefs result from natural, abiotic component, abiotic (non-living) processes such as deposition (geol ...

with a slightly raised central area. The highest point is approximately above sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an mean, average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal Body of water, bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical ...

.

There are no natural fresh water

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salt (chemistry), salts and other total dissolved solids. The term excludes seawater and brackish water, but it does include ...

resources. The landscape features scattered grasses along with prostrate vines and low-growing pisonia trees and shrubs. A 1942 eyewitness description spoke of "a low grove of dead and decaying kou trees" on a very shallow hill at the island's center. In 2000, a visitor accompanying a scientific expedition reported seeing "a flat bulldozed plain of coral sand, without a single tree" and some traces of buildings from colonization or World War II building efforts, all wood and stone ruins overgrown by vegetation.

Howland is primarily a nesting, roosting, and foraging habitat for seabirds, shorebirds, and marine wildlife. The island, with its surrounding marine waters, has been recognized as an Important Bird Area

An Important Bird and Biodiversity Area (IBA) is an area identified using an internationally agreed set of criteria as being globally important for the conservation of bird populations.

IBA was developed and sites are identified by BirdLife Int ...

(IBA) by BirdLife International

BirdLife International is a global partnership of non-governmental organizations that strives to conserve birds and their habitats. BirdLife International's priorities include preventing extinction of bird species, identifying and safeguarding i ...

because it supports seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adaptation, adapted to life within the marine ecosystem, marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent ...

colonies

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their '' metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often or ...

of lesser frigatebird

The lesser frigatebird (''Fregata ariel'') is a seabird of the frigatebird family Fregatidae. At around 75 cm (30 in) in length, it is the smallest species of frigatebird. It occurs over tropical and subtropical waters across the Indian ...

s, masked boobies, red-tailed tropicbirds and sooty terns, as well as serving as a migratory stopover for bristle-thighed curlew

The bristle-thighed curlew (''Numenius tahitiensis'') is a medium-sized shorebird that breeds in Alaska and winters on tropical Pacific islands.

It is known in Mangareva as ''kivi'' or ''kivikivi'' and in Rakahanga as ''kihi''; it is said to b ...

s.

Economics

The U.S. claims an

The U.S. claims an Exclusive Economic Zone

An exclusive economic zone (EEZ), as prescribed by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, is an area of the sea in which a sovereign state has exclusive rights regarding the exploration and use of marine natural resource, reso ...

of and a territorial sea of around the island.

Time zone

Since Howland Island is uninhabited, no time zone is specified. It lies within a nautical time zone, which is 12 hours behind UTC, named International Date Line West ( IDLW). Howland Island and Baker Island are the only places on Earth observing this time zone. This time zone is also called AoE, Anywhere on Earth, a calendar designation indicating that a period expires when the date passes everywhere on Earth.History

Howland Island was claimed by the United States in 1856 and was mined for

Howland Island was claimed by the United States in 1856 and was mined for guano

Guano (Spanish from ) is the accumulated excrement of seabirds or bats. Guano is a highly effective fertiliser due to the high content of nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium, all key nutrients essential for plant growth. Guano was also, to a le ...

later that century. In the 1930s, human activity on the island began with a few people, several buildings, a day beacon, and a cleared landing strip. This was the island Amelia Earhart was going to land on when she was not heard from again on her long flight. The day after Pearl Harbor, the island was bombed and attacked several more times, which damaged the day beacon and killed two people, finally leading to its evacuation. After the war, the day beacon was repaired, and the island became a nature reserve. It has been the subject of visits to honor or look for the lost aviator, Earhart.

Prehistoric settlement

Sparse remnants of trails and other surface features indicate a possible early Polynesian presence, including excavations and mounds, stacked rocks, and a footpath made of long, flat stones. In the 1860s, James Duncan Hague noted discovering the remains of a hut, canoe fragments, a blue bead, and a human skeleton buried in the sand. However, the perishable nature of the wooden materials and the lack of beadwork in Polynesia suggests these materials are historical. The presence of the kou tree ('' Cordia subcordata'') andPolynesian rat

The Polynesian rat, Pacific rat or little rat (''Rattus exulans''), or , is the third most widespread species of rat in the world behind the brown rat and black rat. Contrary to its vernacular name, the Polynesian rat originated in Southeast Asi ...

s (''Rattus exulans'') on the island is also considered a possible indicator of early Polynesian visits to Howland.

However, the only modern archaeological survey of Howland, conducted by the US Army Corps of Engineers in 1987, found no evidence of prehistoric settlement or use of the island. Still, sub-surface testing was limited in scope due to time constraints. Additionally, the USACE survey failed to locate the architectural features described by Hague. However, they concede this may be due to the destruction of these features later during the construction of an airstrip. A later conservation plan by the US Fish and Wildlife Service suggests that Howland was likely used as a stopover or meeting point as opposed to being permanently occupied.

Sightings by whalers

Captain George B. Worth of theNantucket

Nantucket () is an island in the state of Massachusetts in the United States, about south of the Cape Cod peninsula. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck Island, Tuckernuck and Muskeget Island, Muskeget, it constitutes the Town and Co ...

whaler '' Oeno'' sighted Howland around 1822 and called it Worth Island. Daniel MacKenzie of the American whaler ''Minerva Smith'' was unaware of Worth's sighting when he charted the island in 1828 and named it after his ship's owners on . Howland Island was at last named on after a lookout who sighted it from the whaleship ''Isabella'' under Captain Geo. E. Netcher of New Bedford

New Bedford is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. It is located on the Acushnet River in what is known as the South Coast (Massachusetts), South Coast region. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, New Bedford had a ...

.

Captain William Bligh of '' HMS Bounty'', in his diary after the mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military or a crew) to oppose, change, or remove superiors or their orders. The term is commonly used for insubordination by members of the military against an officer or superior, ...

, described stopping at the island shortly after being set adrift by the mutineers in April 1789. He had 18 crew members who scoured the island for sustenance, such as oysters, water, and birds. Bligh was unsure of the island's name, but apparently, it was known to cartographers. Bligh's account on Howland Island is open to question since his route in the boat began between Tonga

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania. The country has 171 islands, of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in the southern Pacific Ocean. accordin ...

and Tofua and ran more or less west directly to Timor

Timor (, , ) is an island at the southern end of Maritime Southeast Asia, in the north of the Timor Sea. The island is Indonesia–Timor-Leste border, divided between the sovereign states of Timor-Leste in the eastern part and Indonesia in the ...

.

U.S. possession and guano mining

Howland Island was uninhabited when the United States took possession of it under the Guano Islands Act of 1856. The island was a known navigation hazard for decades, and several ships were wrecked there. Itsguano

Guano (Spanish from ) is the accumulated excrement of seabirds or bats. Guano is a highly effective fertiliser due to the high content of nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium, all key nutrients essential for plant growth. Guano was also, to a le ...

deposits were mined by American companies from about 1857 until October1878, although there was a dispute between mining companies.

Captain Geo. E. Netcher of the ''Isabella'' informed Captain Taylor of its discovery. As Taylor had discovered another guano island in the Indian Ocean, they agreed to share the benefits of the guano on the two islands. Taylor put Netcher in communication with Alfred G. Benson, president of the American Guano Company, which was incorporated in 1857. Other entrepreneurs were approached as George and Matthew Howland, who later became United States Guano Company members, engaged Mr. Stetson to visit the island on the ship ''Rousseau'' under Captain Pope. Mr. Stetson arrived on the island in 1854 and described it as being occupied by birds and a plague of rats.

The American Guano Company established claims with respect to Baker Island and Jarvis Island

Jarvis Island (; formerly known as Bunker Island or Bunker's Shoal) is an uninhabited coral island located in the South Pacific Ocean, about halfway between Hawaii and the Cook Islands. It is an Territories of the United States#Unincorporated u ...

, which were recognized under the U.S. Guano Islands Act of 1856. Benson tried to interest the American Guano Company in the Howland Island deposits; however, the company directors considered they already had sufficient deposits. In October1857, the American Guano Company sent Benson's son Arthur to Baker and Jarvis Islands to survey the guano deposits. He also visited Howland Island and took samples of the guano. Subsequently, Alfred G. Benson resigned from the American Guano Company. Netcher, Taylor, and George W. Benson formed the United States Guano Company to exploit the guano on Howland Island, with this claim recognized under the U.S. Guano Islands Act of 1856.

However, when the United States Guano Company dispatched a vessel in 1859 to mine the guano, they found that Howland Island was already occupied by men sent there by the American Guano Company. The companies ended up in New York state court, with the American Guano Company arguing that the United States Guano Company had, in effect, abandoned the island since the continual possession and actual occupation required for ownership by the Guano Islands Act did not occur. The result was that both companies were allowed to mine the guano deposits, which were substantially depleted by October1878. Laborers for the mining operations came from around the Pacific, including from Hawaii; the Hawaiian laborers named Howland Island ('kou tree grove'). Established in 1861, the Pacific Guano Company purchased Howland Island to provide a source of guano for its fertilizer plant.

In the late 19th century, British claims were made on the island, and attempts were made to set up mining.

However, when the United States Guano Company dispatched a vessel in 1859 to mine the guano, they found that Howland Island was already occupied by men sent there by the American Guano Company. The companies ended up in New York state court, with the American Guano Company arguing that the United States Guano Company had, in effect, abandoned the island since the continual possession and actual occupation required for ownership by the Guano Islands Act did not occur. The result was that both companies were allowed to mine the guano deposits, which were substantially depleted by October1878. Laborers for the mining operations came from around the Pacific, including from Hawaii; the Hawaiian laborers named Howland Island ('kou tree grove'). Established in 1861, the Pacific Guano Company purchased Howland Island to provide a source of guano for its fertilizer plant.

In the late 19th century, British claims were made on the island, and attempts were made to set up mining. John T. Arundel

John T. Arundel (1 September 1841 – 30 November 1919) was an English entrepreneur who was instrumental in the development of the mining of phosphate rock on the Pacific islands of Nauru and Banaba (Ocean Island). Williams & Macdonald (1985) ...

and Company, a British firm using laborers from the Cook Islands

The Cook Islands is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It consists of 15 islands whose total land area is approximately . The Cook Islands' Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) covers of ocean. Avarua is its ...

and Niue

Niue is a self-governing island country in free association with New Zealand. It is situated in the South Pacific Ocean and is part of Polynesia, and predominantly inhabited by Polynesians. One of the world's largest coral islands, Niue is c ...

, occupied the island from 1886 to 1891.

Executive Order 7368 was issued on to clarify American sovereignty.

Itascatown (1935–1942)

In 1935, colonists from the American Equatorial Islands Colonization Project arrived on the island to establish a permanent U.S. presence in the Central Pacific. It began with a rotating group of four alumni and students from the Kamehameha School for Boys, a private school inHonolulu

Honolulu ( ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, located in the Pacific Ocean. It is the county seat of the Consolidated city-county, consolidated City and County of Honol ...

. Although the recruits had signed on as part of a scientific expedition and expected to spend their three-month assignment collecting botanical and biological samples, once out to sea, they were told, according to one of the Jarvis Island colonists, George West, "Your names will go down in history" and that the islands would become "famous air bases in a route that will connect Australia with California".

The settlement was named Itascatown after the USCGC ''Itasca'' that brought the colonists to Howland and made regular cruises between the other equatorial islands during that era. Itascatown was a line of a half-dozen small wood-framed structures and tents near the beach on the island's western side. The fledgling colonists were given large stocks of canned food, water, and other supplies, including a gasoline-powered refrigerator, radio equipment, medical kits, and (characteristic of that era) vast quantities of cigarettes. Fishing provided variety in their diet. Most of the colonists' endeavors involved making hourly weather observations and constructing rudimentary infrastructure on the island, including clearing a landing strip for airplanes. During this period, the island was on Hawaii time, which was then 10.5hours behind UTC. Similar colonization projects were started on nearby Baker Island and Jarvis Island

Jarvis Island (; formerly known as Bunker Island or Bunker's Shoal) is an uninhabited coral island located in the South Pacific Ocean, about halfway between Hawaii and the Cook Islands. It is an Territories of the United States#Unincorporated u ...

, as well as Canton Island

Canton Island (also known as Kanton or Abariringa), previously known as Mary Island, Mary Balcout's Island or Swallow Island, is the largest, northernmost, and , the sole inhabited island of the Phoenix Islands, in the Republic of Kiribati. It i ...

and Enderbury in the Phoenix Islands

The Phoenix Islands, or Rawaki, are a group of eight atolls and two submerged coral reefs that lie east of the Gilbert Islands and west of the Line Islands in the central Pacific Ocean, north of Samoa. They are part of the Kiribati, Republic ...

, which later became part of Kiribati

Kiribati, officially the Republic of Kiribati, is an island country in the Micronesia subregion of Oceania in the central Pacific Ocean. Its permanent population is over 119,000 as of the 2020 census, and more than half live on Tarawa. The st ...

. According to the 1940 U.S. census, Howland Island had a population of four people on April 1, 1940.

Kamakaiwi Field

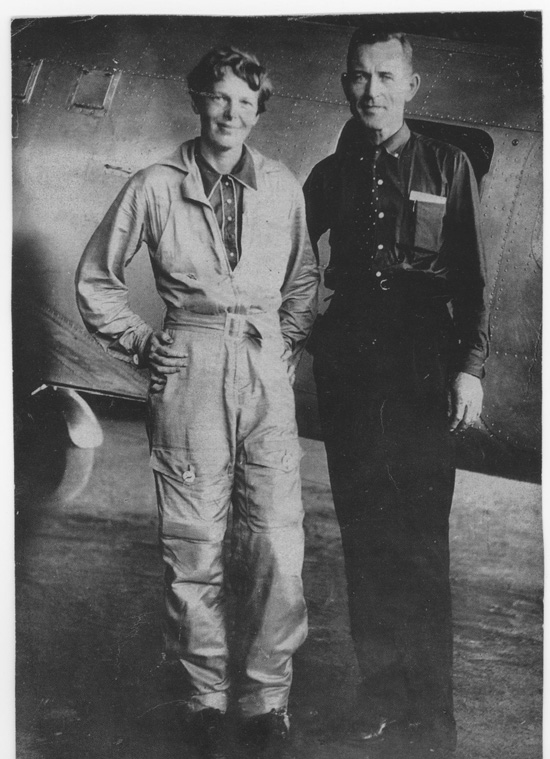

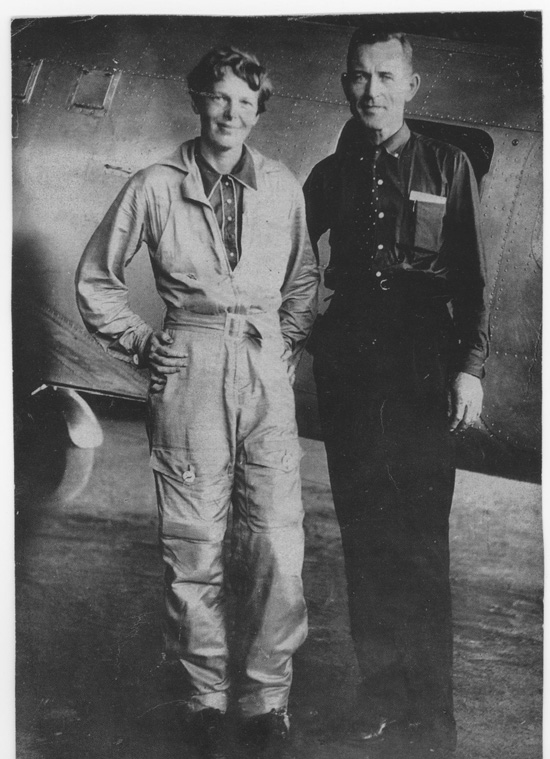

Ground was cleared for a rudimentary aircraft landing area during the mid-1930s in anticipation that the island might eventually become a stopover for commercial trans-Pacific air routes and also to further U.S. territorial claims in the region against rival claims from Great Britain. Howland Island was designated as a scheduled refueling stop for American pilot

Ground was cleared for a rudimentary aircraft landing area during the mid-1930s in anticipation that the island might eventually become a stopover for commercial trans-Pacific air routes and also to further U.S. territorial claims in the region against rival claims from Great Britain. Howland Island was designated as a scheduled refueling stop for American pilot Amelia Earhart

Amelia Mary Earhart ( ; July 24, 1897 – January 5, 1939) was an American aviation pioneer. On July 2, 1937, she disappeared over the Pacific Ocean while attempting to become the first female pilot to circumnavigate the world. During her li ...

and navigator Fred Noonan on their round-the-world flight in 1937. Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; from 1935 to 1939, then known as the Work Projects Administration from 1939 to 1943) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to car ...

(WPA) funds were used by the Bureau of Air Commerce to construct three graded, unpaved runways meant to accommodate Earhart's twin-engined Lockheed Model 10 Electra

The Lockheed Model 10 Electra is an American twin-engined, all-metal monoplane airliner developed by the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation, which was produced primarily in the 1930s to compete with the Boeing 247 and Douglas DC-2. The type gained ...

.

The facility was named ''Kamakaiwi Field'' after James Kamakaiwi, a young Hawaiian who arrived with the first group of four colonists. He was selected as the group's leader and spent more than three years on Howland, far longer than the average recruit. It has also been referred to as ''WPA Howland Airport'' (the WPA contributed about 20 percent of the $12,000 cost).

Earhart and Noonan took off from Lae, New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

, and their radio transmissions were picked up near the island when their aircraft reached the vicinity, but they failed to arrive. It is known that they must have gotten within the radio range of Howland due to the strength of the final radio communications that morning, despite some problems with radio communication and radio direction finding. In some of the last messages recorded from them on 2 July 1937, 7:42 am, Earhart reported, "We must be on you, but cannot see you – but gas is running low. Have been unable to reach you by radio. We are flying at 1,000 feet." At 8:43 am, Earhart reported, "We are on the line 157 337. We will repeat this message. We will repeat this on 6210 kilocycles. Wait." Between Earhart's low-on-fuel message at 7:42 am and her last confirmed message at 8:43, her signal strength remained consistent, indicating that she never left the immediate Howland area as she ran low on fuel. The U.S. Coast Guard determined this by tracking her signal strength as she approached the island, noting signal levels from her reports of 200 and 100 miles out. These reports were roughly 30 minutes apart, providing vital ground-speed clues.

After the largest search and rescue attempt in history up to that time, the U.S. Navy concluded that the Electra had run out of fuel, and Earhart and Noonan ditched at sea and perished. Based on the strength of the transmission signals from Earhart, the Coast Guard concluded that the plane ran out of fuel north of Howland. Many later studies came to the same conclusion; however, an alternative hypothesis that Earhart and Noonan may have landed the plane on Gardner Island (now called Nikumaroro) and died as castaways has been considered.

Japanese attacks during World War II

AJapan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

ese air attack on , by 14 twin-engined Mitsubishi G3M "Nell" bombers of Chitose Kōkūtai, from Kwajalein islands, killed colonists Richard "Dicky" Kanani Whaley and Joseph Kealoha Keliʻihananui. The raid came one day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Reci ...

. It damaged the three airstrips of Kamakaiwi Field. Two days later, shelling from a Japanese submarine destroyed what was left of the colony's buildings. A single bomber returned twice during the following weeks and dropped more bombs on the rubble. The two survivors were finally evacuated by the , a U.S. Navy destroyer, on . Thomas Bederman, one of the two survivors, later recounted his experience during the incident in a edition of ''Life

Life, also known as biota, refers to matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes. It is defined descriptively by the capacity for homeostasis, Structure#Biological, organisation, met ...

''. Howland was occupied by a battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of up to one thousand soldiers. A battalion is commanded by a lieutenant colonel and subdivided into several Company (military unit), companies, each typically commanded by a Major (rank), ...

of the United States Marine Corps

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines or simply the Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is responsible for conducting expeditionar ...

in September1943 and was known as Howland Naval Air Station until May1944.

All attempts at habitation were abandoned after 1944. Colonization projects on the other four islands, also disrupted by the war, were abandoned. No aircraft is known to have landed on the island, though anchorages nearby were used by float planes and flying boats during World War II. For example, on , a U.S. Navy Martin PBM-3-D Mariner flying boat (BuNo 48199), piloted by William Hines, had an engine fire and made a forced landing in the ocean off Howland. Hines beached the aircraft, and though it burned, the crew were unharmed, rescued by the , transferred to a subchaser, and taken to Canton Island.

National Wildlife Refuge

On June 27, 1974, Secretary of the Interior

On June 27, 1974, Secretary of the Interior Rogers Morton

Rogers Clark Ballard Morton (September 19, 1914 – April 19, 1979) was an American politician who served as the U.S. Secretary of the Interior and Secretary of Commerce during the administrations of presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford, ...

created Howland Island National Wildlife Refuge, which was expanded in 2009 to add submerged lands within of the island. The refuge now includes of land and of water. Along with six other islands, the island was administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as part of the Pacific Remote Islands National Wildlife Refuge Complex. In January2009, that entity was upgraded to the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument by President George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

.

Multiple invasive exotic species have affected the island habitat. Black rats were introduced in 1854 and eradicated in 1938 by feral cats introduced the year before. The cats proved destructive to bird species and were eliminated by 1985. Pacific crabgrass continues to compete with local plants.

Public entry to the island is allowed with a special use permit from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and it is generally restricted to scientists and educators. Representatives from the agency visit the island on average once every two years, often coordinating transportation with amateur radio operators or the U.S. Coast Guard to defray the high cost of logistical support.

Earhart Light

Colonists sent to the island in the mid-1930s to establish possession by the United States, built the Earhart Light , named afterAmelia Earhart

Amelia Mary Earhart ( ; July 24, 1897 – January 5, 1939) was an American aviation pioneer. On July 2, 1937, she disappeared over the Pacific Ocean while attempting to become the first female pilot to circumnavigate the world. During her li ...

, as a day beacon or navigational landmark. It is shaped like a short lighthouse

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of physical structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lens (optics), lenses and to serve as a beacon for navigational aid for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways.

Ligh ...

. It was constructed of white sandstone with painted black bands and a black top meant to be visible several miles out to sea during daylight hours. It is located near the boat landing in the middle of the west coast, near Itascatown. The beacon was partially destroyed early in World War II by Japanese attacks but was rebuilt in the early 1960s by men from the U.S. Coast Guard ship '' Blackhaw''. By 2000, the beacon was reported to be crumbling, and it had not been repainted in decades.

Ann Pellegreno overflew the island in 1967, and Linda Finch did so in 1997 during memorial circumnavigation flights to commemorate Earhart's 1937 world flight. No landings were attempted, but Pellegreno and Finch flew low enough to drop a wreath on the island.

Image gallery

leeward

In geography and seamanship, windward () and leeward () are directions relative to the wind. Windward is ''upwind'' from the point of reference, i.e., towards the direction from which the wind is coming; leeward is ''downwind'' from the point o ...

)

File:Howland Fauna.JPG, Young masked boobies

File:Howland Boobies.JPG, Masked boobies

File:Howland birds.JPG, Ruddy turnstones

File:Earhart Light.jpg, Earhart Light, 2008

See also

* List of lighthouses in United States Minor Outlying Islands * Howland and Baker islands, includes coverage of the Howland-Baker EEZ * History of the Pacific Islands * List of Guano Island claims *Phoenix Islands

The Phoenix Islands, or Rawaki, are a group of eight atolls and two submerged coral reefs that lie east of the Gilbert Islands and west of the Line Islands in the central Pacific Ocean, north of Samoa. They are part of the Kiribati, Republic ...

References

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * *"Eyewitness account of the Japanese raids on Howland Island (includes a grainy photo of Itascatown)."

''ksbe.edu.'' Retrieved: October 10, 2010. * * * * * *

External links

Howland Island National Wildlife Refuge

– U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Geography, history and nature on Howland Island

*

{{Authority control , additional=Q20932641 Coral islands Uninhabited Pacific islands of the United States Amelia Earhart Works Progress Administration National Wildlife Refuges in the United States insular areas Important Bird Areas of United States Minor Outlying Islands Important Bird Areas of Oceania Seabird colonies