Howard Carter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Howard Carter (9 May 18742 March 1939) was a British

In 1907, Carter began work for Lord Carnarvon, who employed him to supervise the excavation of nobles' tombs in

In 1907, Carter began work for Lord Carnarvon, who employed him to supervise the excavation of nobles' tombs in

Five Years' Explorations at Thebes

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Carter, Howard 1874 births 1939 deaths Burials at Putney Vale Cemetery Deaths from lymphoma in England Deaths from Hodgkin lymphoma Archaeologists from London Egyptology English Egyptologists People from Kensington 19th-century British archaeologists 20th-century British archaeologists Tutankhamun Valley of the Kings 1922 archaeological discoveries 1922 in Egypt November 1922 British expatriates in Egypt

archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

and Egyptologist

Egyptology (from ''Egypt'' and Greek , ''-logia''; ) is the scientific study of ancient Egypt. The topics studied include ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, architecture and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end ...

who discovered the intact tomb of the 18th Dynasty

The Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XVIII, alternatively 18th Dynasty or Dynasty 18) is classified as the first dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt, the era in which ancient Egypt achieved the peak of its power. The Eighteenth Dynasty ...

Pharaoh Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun or Tutankhamen, (; ), was an Egyptian pharaoh who ruled during the late Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt. Born Tutankhaten, he instituted the restoration of the traditional polytheistic form of an ...

in November 1922, the best-preserved pharaonic tomb ever found in the Valley of the Kings

The Valley of the Kings, also known as the Valley of the Gates of the Kings, is an area in Egypt where, for a period of nearly 500 years from the Eighteenth Dynasty to the Twentieth Dynasty, rock-cut tombs were excavated for pharaohs and power ...

.

Early life

Howard Carter was born inKensington

Kensington is an area of London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, around west of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up by Kensingt ...

on 9 May 1874, the youngest child (of eleven) of artist and illustrator Samuel John Carter and Martha Joyce Carter (). His father helped train and develop his artistic talents.

Carter spent much of his childhood with relatives in the Norfolk

Norfolk ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in England, located in East Anglia and officially part of the East of England region. It borders Lincolnshire and The Wash to the north-west, the North Sea to the north and eas ...

market town

A market town is a settlement most common in Europe that obtained by custom or royal charter, in the Middle Ages, a market right, which allowed it to host a regular market; this distinguished it from a village or city. In Britain, small rura ...

of Swaffham

Swaffham () is a market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Breckland District and England, English county of Norfolk. It is situated east of King's Lynn and west of Norwich.

The civil parish has an area of and in the U ...

, the birthplace of both his parents. His father had previously relocated to London, but after three of the children had died young, Carter, who was a sickly child, was moved to Norfolk and raised for the most part by a nurse in Swaffham.

Receiving only limited formal education at Swaffham, he showed talent as an artist. The nearby mansion of the Amherst family, Didlington Hall, contained a sizable collection of Egyptian antiques, which sparked Carter's interest in that subject. Lady Amherst was impressed by his artistic skills, and in 1891 she prompted the Egypt Exploration Fund (EEF) to send Carter to assist an Amherst family friend, Percy Newberry, in the excavation and recording of Middle Kingdom tombs at Beni Hasan

Beni Hasan (also written as Bani Hasan, or also Beni-Hassan) () is an ancient Egyptian cemetery. It is located approximately to the south of modern-day Minya in the region known as Middle Egypt, the area between Asyut and Memphis.Baines, John ...

.

Although only 17, Carter was innovative in improving the methods of copying tomb decoration. In 1892, he worked under the tutelage of Flinders Petrie

Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie ( – ), commonly known as simply Sir Flinders Petrie, was an English people, English Egyptology, Egyptologist and a pioneer of systematic methodology in archaeology and the preservation of artefacts. ...

for one season at Amarna

Amarna (; ) is an extensive ancient Egyptian archaeological site containing the ruins of Akhetaten, the capital city during the late Eighteenth Dynasty. The city was established in 1346 BC, built at the direction of the Pharaoh Akhenaten, and a ...

, the capital founded by the pharaoh Akhenaten

Akhenaten (pronounced ), also spelled Akhenaton or Echnaton ( ''ʾŪḫə-nə-yātəy'', , meaning 'Effective for the Aten'), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning or 1351–1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eig ...

. From 1894 to 1899, he worked with Édouard Naville

Henri Édouard Naville (14 June 1844 – 17 October 1926) was a Swiss archaeologist, Egyptologist and Biblical scholar.

Born in Geneva, he studied at the University of Geneva, King's College, London, and the Universities of Bonn, Paris, an ...

at Deir el-Bahari

Deir el-Bahari or Dayr al-Bahri (, , ) is a complex of mortuary temples and tombs located on the west bank of the Nile, opposite the city of Luxor, Egypt. This is a part of the Theban Necropolis.

History

Deir el-Bahari, located on the west ...

, where he recorded the wall reliefs in the temple of Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut ( ; BC) was the sixth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, Egypt, ruling first as regent, then as queen regnant from until (Low Chronology) and the Great Royal Wife of Pharaoh Thutmose II. She was Egypt's second c ...

.

In 1899, Carter was appointed Inspector of Monuments for Upper Egypt in the Egyptian Antiquities Service (EAS) on the personal recommendation of Gaston Maspero. Based at Luxor

Luxor is a city in Upper Egypt. Luxor had a population of 263,109 in 2020, with an area of approximately and is the capital of the Luxor Governorate. It is among the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest continuously inhabited c ...

, he oversaw a number of excavations and restorations at nearby Thebes, while in the Valley of the Kings

The Valley of the Kings, also known as the Valley of the Gates of the Kings, is an area in Egypt where, for a period of nearly 500 years from the Eighteenth Dynasty to the Twentieth Dynasty, rock-cut tombs were excavated for pharaohs and power ...

he supervised the systematic exploration of the valley by the American archaeologist Theodore Davis.

In early 1902, Carter began searching the Valley of the Kings on his own. He initially aimed at the southeast rocky wall of the valley basin. Despite being an inaccessible area, within three days he found what he was looking for: stone steps, sepulchral entrance, corridor, sarcophagus chamber, in short, the last home of the fourth Thutmose, carefully stripped (except for a few furnishings and a cart). While digging to find Thutmose IV's final resting place, Carter unearthed an alabaster cup and a small blue scarab with Queen Hatshepsut's name on it.

In February 1903, north of the tomb of Thutmose IV, Carter found a stone bearing the ring with the name of Hatshepsut.

In 1904, after a dispute with local people over tomb thefts, he was transferred to the Inspectorate of Lower Egypt. Carter was praised for his improvements in the protection of, and accessibility to, existing excavation sites, and his development of a grid-block system for searching for tombs. The Antiquities Service also provided funding for Carter to head his own excavation projects.

Carter resigned from the Antiquities Service in 1905 after a formal inquiry into what became known as the Saqqara Affair, a violent confrontation that took place on 8 January 1905 between Egyptian site guards and a group of French tourists. Carter sided with the Egyptian personnel, refusing to apologise when the French authorities made an official complaint. Moving back to Luxor, Carter was without formal employment for nearly three years. He made a living by painting and selling watercolours to tourists and, in 1906, acting as a freelance draughtsman for Theodore Davis.

Tutankhamun's tomb

In 1907, Carter began work for Lord Carnarvon, who employed him to supervise the excavation of nobles' tombs in

In 1907, Carter began work for Lord Carnarvon, who employed him to supervise the excavation of nobles' tombs in Deir el-Bahari

Deir el-Bahari or Dayr al-Bahri (, , ) is a complex of mortuary temples and tombs located on the west bank of the Nile, opposite the city of Luxor, Egypt. This is a part of the Theban Necropolis.

History

Deir el-Bahari, located on the west ...

, near Thebes. Gaston Maspero, head of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, had recommended Carter to Carnarvon as he knew he would apply modern archaeological methods and systems of recording. Carter soon developed a good working relationship with his patron, with Lady Burghclere, Carnarvon's sister, observing that "for the next sixteen years the two men worked together with varying fortune, yet ever united not more by their common aim than by their mutual regard and affection".

In 1914, Lord Carnarvon received the concession to dig in the Valley of the Kings. Carter led the work, undertaking a systematic search for any tombs missed by previous expeditions, in particular that of the Pharaoh Tutankhamun. However, excavations were soon interrupted by the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Carter spending the war years working for the British Government as a diplomatic courier and translator. He enthusiastically resumed his excavation work towards the end of 1917.

By 1922, Lord Carnarvon had become dissatisfied with the lack of results after several years of finding little. After considering withdrawing his funding, Carnarvon agreed, after a discussion with Carter, that he would fund one more season of work in the Valley of the Kings.

Carter returned to the Valley of Kings, and investigated a line of huts that he had abandoned a few seasons earlier. The crew cleared the huts and rock debris beneath. On 4 November 1922, a worker uncovered a step in the rock. According to Carter's published account, the workmen discovered the step while digging beneath the remains of the huts; other accounts attribute the discovery to a boy digging outside the assigned work area. Carter had the steps partially dug out until the top of a mud-plastered doorway was found. The doorway was stamped with indistinct cartouche

upalt=A stone face carved with coloured hieroglyphics. Two cartouches - ovoid shapes with hieroglyphics inside - are visible at the bottom., Birth and throne cartouches of Pharaoh KV17.html" ;"title="Seti I, from KV17">Seti I, from KV17 at the ...

s (oval seals with hieroglyphic writing). Carter ordered the staircase to be refilled, and sent a telegram to Carnarvon, who arrived from England two and a half weeks later on 23 November, accompanied by his daughter Lady Evelyn Herbert.

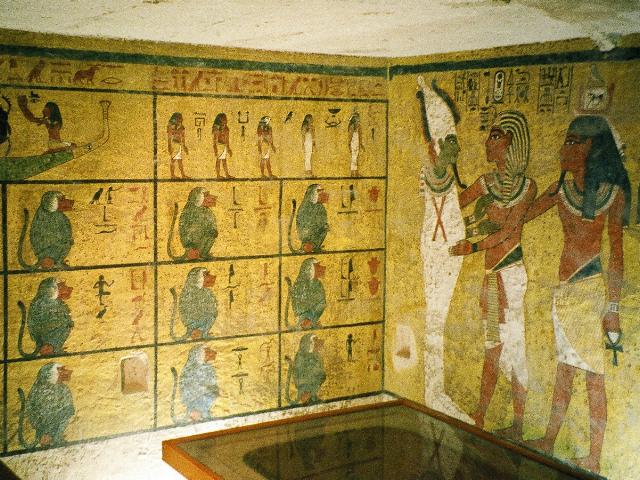

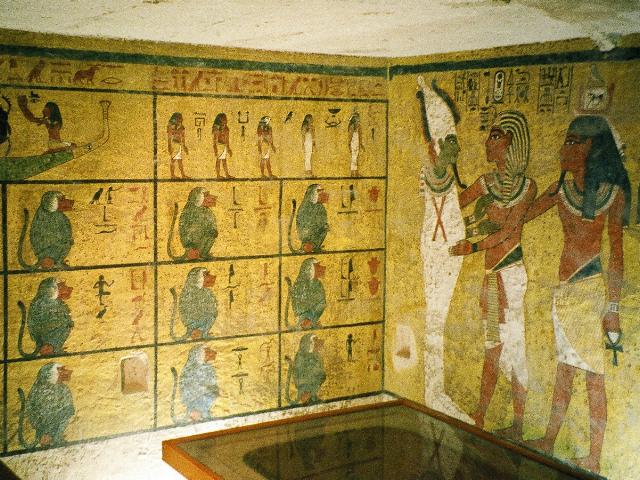

On 24 November 1922, the full extent of the stairway was cleared and a seal containing Tutankhamun's cartouche found on the outer doorway. This door was removed and the rubble-filled corridor behind cleared, revealing the door of the tomb itself. On 26 November, Carter, with Carnarvon, Lady Evelyn and assistant Arthur Callender in attendance, made a "tiny breach in the top left-hand corner" of the doorway, using a chisel that his grandmother had given him for his 17th birthday. He was able to peer in by the light of a candle and see that many of the gold and ebony treasures were still in place. He did not yet know whether it was "a tomb or merely an old cache", but he did see a promising sealed doorway between two sentinel statues. Carnarvon asked, "Can you see anything?" Carter replied: "Yes, wonderful things!" Carter had, in fact, discovered Tutankhamun's tomb (subsequently designated KV62). The tomb was then secured, to be entered in the presence of an official of the Egyptian Department of Antiquities the next day. However that night, Carter, Carnarvon, Lady Evelyn and Callender apparently made an unauthorised visit, becoming the first people in modern times to enter the tomb. Some sources suggest that the group also entered the inner burial chamber. In this account, a small hole was found in the chamber's sealed doorway and Carter, Carnarvon and Lady Evelyn crawled through.

The next morning, 27 November, saw an inspection of the tomb in the presence of an Egyptian official. Callender rigged up electric lighting, illuminating a vast haul of items, including gilded couches, chests, thrones, and shrines. They also saw evidence of two further chambers, including the sealed doorway to the inner burial chamber, guarded by two life-size statues of Tutankhamun. In spite of evidence of break-ins in ancient times, the tomb was virtually intact, and would ultimately be found to contain over 5,000 items.

On 29 November the tomb was officially opened in the presence of a number of invited dignitaries and Egyptian officials.

Realising the size and scope of the task ahead, Carter sought help from Albert Lythgoe of the Metropolitan Museum

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, colloquially referred to as the Met, is an encyclopedic art museum in New York City. By floor area, it is the third-largest museum in the world and the largest art museum in the Americas. With 5.36 million v ...

's excavation team, working nearby, who readily agreed to lend a number of his staff, including Arthur Mace and archaeological photographer Harry Burton, while the Egyptian government loaned analytical chemist Alfred Lucas. The next several months were spent cataloguing and conserving the contents of the antechamber under the "often stressful" supervision of Pierre Lacau, director general of the Department of Antiquities.

On 16 February 1923, Carter opened the sealed doorway and confirmed it led to a burial chamber, containing the sarcophagus

A sarcophagus (: sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a coffin, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Greek language, Greek wikt:σάρξ, σάρξ ...

of Tutankhamun. The tomb was considered the best preserved and most intact pharaonic tomb ever found in the Valley of the Kings, and the discovery was eagerly covered by the world's press. However, much to the annoyance of other newspapers, Lord Carnarvon sold exclusive reporting rights to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

''. Only Arthur Merton of that paper was allowed on the scene, and his vivid descriptions helped to establish Carter's reputation with the British public.

Towards the end of February 1923, a rift between Lord Carnarvon and Carter, probably caused by a disagreement on how to manage the supervising Egyptian authorities, temporarily halted the excavation. Work recommenced in early March after Lord Carnarvon apologised to Carter. Later that month, Lord Carnarvon contracted blood poisoning while staying in Luxor near the tomb site. He died in Cairo on 5 April 1923. Lady Carnarvon retained her late husband's concession in the Valley of the Kings, allowing Carter to continue his work.

Carter's meticulous assessing and cataloguing of the thousands of objects in the tomb took nearly ten years, most being moved to the Egyptian Museum

The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, commonly known as the Egyptian Museum (, Egyptian Arabic: ) (also called the Cairo Museum), located in Cairo, Egypt, houses the largest collection of Ancient Egypt, Egyptian antiquities in the world. It hou ...

in Cairo. There were several breaks in the work, including one lasting nearly a year in 1924–25, caused by a dispute over what Carter saw as excessive control of the excavation by the Egyptian Antiquities Service. The Egyptian authorities eventually agreed that Carter should complete the tomb's clearance. This continued until 1929, with some final work lasting until February 1932.

Despite the significance of his archaeological find, Carter received no honour from the British government. However, in 1926, he received the Order of the Nile

The Order of the Nile (''Kiladat El Nil'') was established in 1915 and was one of the Kingdom of Egypt's principal orders until the monarchy was abolished in 1953. It was then reconstituted as the Republic of Egypt's highest state honor.

Sulta ...

, third class, from King Fuad I of Egypt

Fuad I ( ''Fu’ād al-Awwal''; 26 March 1868 – 28 April 1936) was the Sultan and later King of Egypt and the Sudan. The ninth ruler of Egypt and Sudan from the Muhammad Ali dynasty, he became Sultan in 1917, succeeding his elder brother Hu ...

. He was also awarded an honorary degree of Doctor of Science by Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

and honorary membership in the Real Academia de la Historia

The Royal Academy of History (, RAH) is a Spanish institution in Madrid that studies history "ancient and modern, political, civil, ecclesiastical, military, scientific, of letters and arts, that is to say, the different branches of life, of c ...

of Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

, Spain.

Carter wrote a number of books on Egyptology during his career, including ''Five Years' Exploration at Thebes'', co-written with Lord Carnarvon in 1912, describing their early excavations, and a three-volume popular account of the discovery and excavation of Tutankhamun's tomb. He also delivered a series of illustrated lectures on the excavation, including a 1924 tour of Britain, France, Spain and the United States. Those in New York and other US cities were attended by large and enthusiastic audiences, sparking American Egyptomania, with President Coolidge requesting a private lecture.

In 2022, a 1934 letter to Carter from Alan Gardiner

Sir Alan Henderson Gardiner, (29 March 1879 – 19 December 1963) was an English Egyptologist, linguist, philologist, and independent scholar. He is regarded as one of the premier Egyptologists of the early and mid-20th century.

Personal li ...

came to light, accusing him of stealing from Tutankhamun's tomb. Carter had given Gardiner an amulet and assured him it had not come from the tomb, but Reginald Engelbach, director of the Egyptian Museum, later confirmed its match with other samples originating in the tomb. Egyptologist Bob Brier said the letter proved previous rumours, and the contemporary suspicions of Egyptian authorities, that Carter had been siphoning treasures for himself.

Personal life

Carter could be awkward in company, particularly with those of a higher social standing. Often abrasive, he admitted to having a hot temper, which often aggravated disputes, including the 1905 Saqqara Affair and the 1924–25 dispute with Egyptian authorities. The suggestion that Carter had an affair with Lady Evelyn Herbert, the daughter of the 5th Earl of Carnarvon, was later rejected by Lady Evelyn herself, who told her daughter Patricia that "at first I was in awe of him, later I was rather frightened of him", resenting Carter's "determination" to come between her and her father. More recently, the 8th Earl dismissed the idea, describing Carter as a "stoical loner". Harold Plenderleith, a former associate of Carter's at the British Museum, was quoted as saying that he knew "something about Carter that was not fit to disclose", which some have interpreted as meaning that Plenderleith believed that Carter was homosexual. An Egyptian guide who knew Carter claimed that his tastes extended to "both boys and the occasional 'dancing girl. There is, however, no evidence that Carter enjoyed any close relationships throughout his life, and he never married nor had children.Later life

After the clearance of the tomb had been completed in 1932 Carter retired from excavation work. He continued to live in his house near Luxor in winter and retained a flat in London but, as interest in Tutankhamun declined, he lived a fairly isolated existence with few close friends. He had acted as a part-time dealer for both collectors and museums for a number of years. He continued in this role, including acting for theCleveland Museum of Art

The Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) is an art museum in Cleveland, Ohio, United States. Located in the Wade Park District of University Circle, the museum is internationally renowned for its substantial holdings of Asian art, Asian and Art of anc ...

and the Detroit Institute of Arts

The Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) is a museum institution located in Midtown Detroit, Michigan. It has list of largest art museums, one of the largest and most significant art collections in the United States. With over 100 galleries, it cove ...

.

Death

Carter died fromHodgkin's disease

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a type of lymphoma in which cancer originates from a specific type of white blood cell called lymphocytes, where multinucleated Reed–Sternberg cells (RS cells) are present in the lymph nodes. The condition was named a ...

aged 64 at his London flat at 49 Albert Court, next to the Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London, England. It has a seating capacity of 5,272.

Since the hall's opening by Queen Victoria in 1871, the world's leading artists from many performance genres ...

, on 2 March 1939. He was buried in Putney Vale Cemetery in London on 6 March, nine people attending his funeral.

His love for Egypt remained strong; the epitaph on his gravestone reads: "May your spirit live, may you spend millions of years, you who love Thebes, sitting with your face to the north wind, your eyes beholding happiness", a quotation taken from the Wishing Cup of Tutankhamun, and "O night, spread thy wings over me as the imperishable stars".

Probate

In common law jurisdictions, probate is the judicial process whereby a will is "proved" in a court of law and accepted as a valid public document that is the true last testament of the deceased; or whereby, in the absence of a legal will, the e ...

was granted on 5 July 1939 to Egyptologist Henry Burton Henry Burton may refer to:

* Henry Burton (Conservative politician) (1876–1947), British Conservative MP for Sudbury (1924–1945)

* Henry Burton (physician) (1799–1849), English physician

* Henry Burton (theologian) (1578–1648), English Puri ...

and to publisher Bruce Sterling Ingram. Carter is described as Howard Carter of Luxor, Upper Egypt, Africa, and of 49 Albert Court, Kensington Grove, Kensington

Kensington is an area of London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, around west of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up by Kensingt ...

, London. His estate was valued at £2,002 (). The second grant of Probate was issued in Cairo on 1 September 1939. In his role as executor, Burton identified at least 18 items in Carter's antiquities collection that had been taken from Tutankhamun's tomb without authorisation. As this was a sensitive matter that could affect Anglo-Egyptian relations, Burton sought wider advice, finally recommending that the items be discreetly presented or sold to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, with most eventually going either there or to the Egyptian Museum

The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, commonly known as the Egyptian Museum (, Egyptian Arabic: ) (also called the Cairo Museum), located in Cairo, Egypt, houses the largest collection of Ancient Egypt, Egyptian antiquities in the world. It hou ...

in Cairo. The Metropolitan Museum items were later returned to Egypt.

Selected publications

* ''The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamen'' (1923) (written together with A. C. Mace) * ''The Tomb of Tutankhamun: Volume I – Search, Discovery and Clearance of the Antechamber'' (1923) (written together with A. C. Mace) * ''The Tomb of Tutankhamun: Volume II – Burial Chamber & Mummy'' (1927) * ''The Tomb of Tutankhamun: Volume III – Treasury & Annex'' (1933)In popular culture

Carter's discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb revived popular interest in Ancient Egypt – ' Egyptomania' – and created "Tutmania", which influenced popular song and fashion. Carter used this heightened interest to promote his books on the discovery and his lecture tours in Britain, America and Europe. While interest had waned by the mid-1930s, from the early 1970s touring exhibitions of the tomb's artefacts led to a sustained rise in popularity. This has been reflected in TV dramas, films and books, with Carter's quest and discovery of the tomb portrayed with varying levels of accuracy. One common element in popular representations of the excavation is the idea of a 'curse

A curse (also called an imprecation, malediction, execration, malison, anathema, or commination) is any expressed wish that some form of adversity or misfortune will befall or attach to one or more persons, a place, or an object. In particular, ...

'. Carter consistently dismissed the suggestion as 'tommy-rot', commenting that "the sentiment of the Egyptologist ... is not one of fear, but of respect and awe ... entirely opposed to foolish superstitions".

Dramas

Carter has been portrayed or referred to in many film, television and radio productions: *In theBBC Radio

BBC Radio is an operational business division and service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) which has operated in the United Kingdom under the terms of a royal charter since 1927. The service provides national radio stations cove ...

play ''The Tomb of Tutankhamen'', written by Leonard Cottrell and first broadcast in 1949, he is voiced by Jack Hawkins.

*In the Columbia Pictures Television

Columbia Pictures Television, Inc. (abbreviated as CPT) was launched on May 6, 1974, by Columbia Pictures as an American television production and distribution company. It is the second name of Columbia Pictures' television division Screen Gems ...

film '' The Curse of King Tut's Tomb'' (1980), he is portrayed by Robin Ellis

Anthony Robin Ellis (born 8 January 1942) is a British actor and cookery book writer best known for his role as Captain Ross Poldark in the 29 episodes of the 1975 BBC classic series ''Poldark (1975 TV series), Poldark'', adapted from a serie ...

.

*In the 1981 film ''Sphinx

A sphinx ( ; , ; or sphinges ) is a mythical creature with the head of a human, the body of a lion, and the wings of an eagle.

In Culture of Greece, Greek tradition, the sphinx is a treacherous and merciless being with the head of a woman, th ...

'', he is portrayed by Mark Kingston

Mark Kingston (18 April 1934 – 9 October 2011) was an English actor who made many television and stage appearances over his 50-year career.

Biography

Kingston's father was a blacksmith and he attended Greenwich Central School and train ...

.

*In George Lucas

George Walton Lucas Jr. (born May 14, 1944) is an American filmmaker and philanthropist. He created the ''Star Wars'' and ''Indiana Jones'' franchises and founded Lucasfilm, LucasArts, Industrial Light & Magic and THX. He served as chairman ...

's TV films '' Young Indiana Jones and the Curse of the Jackal'' (1992) and '' Young Indiana Jones and the Treasure of the Peacock's Eye'' (1995), he is portrayed by Pip Torrens

Philip D'Oyly TorrensThe Cambridge University List of Members up to 31 July 1998, University of Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1998, p. 793 (born 2 June 1960) is an English actor.

Torrens portrayed courtier Tommy Lascelles in the Netfl ...

.

*In the IMAX

IMAX is a proprietary system of High-definition video, high-resolution cameras, film formats, film projectors, and movie theater, theaters known for having very large screens with a tall aspect ratio (image), aspect ratio (approximately ei ...

documentary ''Mysteries of Egypt

''Mysteries of Egypt'' is an IMAX film about Howard Carter, Howard Carter's discovery of Tutankhamun, King Tutankhamen's tomb in 1922. Directed by Bruce Neibaur, the film was released June 2, 1998.

Cast

* Omar Sharif - Grandfather

* Kate Maberly ...

'' (1998), he is portrayed by Timothy Davies.

*In the made-for-TV film ''The Tutankhamun Conspiracy'' (2001), he is portrayed by Giles Watling

Giles Francis Watling (born 18 February 1953) is a British Conservative politician who served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Clacton from 2017 until 2024. He was an actor prior to entering politics.

Early life and education

Giles Watli ...

.

*In an episode of 2005 BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

docudrama ''Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

'', he is portrayed by Stuart Graham.

*He was portrayed in the 2008 Big Finish Radio Drama Forty-five, a title in the Doctor Who

''Doctor Who'' is a British science fiction television series broadcast by the BBC since 1963. The series, created by Sydney Newman, C. E. Webber and Donald Wilson (writer and producer), Donald Wilson, depicts the adventures of an extraterre ...

range, voiced by Benedict Cumberbatch

Benedict Timothy Carlton Cumberbatch (born 19 July 1976) is an English actor. He has received List of awards and nominations received by Benedict Cumberbatch, various accolades, including a BAFTA TV Award, a Primetime Emmy Award and a Laurenc ...

.

*As the main character in 2016 ITV miniseries ''Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun or Tutankhamen, (; ), was an Egyptian pharaoh who ruled during the late Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt. Born Tutankhaten, he instituted the restoration of the traditional polytheistic form of an ...

'', portrayed by Max Irons

Maximilian Paul Diarmuid Irons (born 17 October 1985) is an English and Irish actor. He is known for his roles in films such as ''Red Riding Hood (2011 film), Red Riding Hood'' (2011), ''The White Queen (miniseries), The White Queen'' (2013), '' ...

.

Literature

*He is referenced inHergé

Georges Prosper Remi (; 22 May 1907 – 3 March 1983), known by the pen name Hergé ( ; ), from the French pronunciation of his reversed initials ''RG'', was a Belgian comic strip artist. He is best known for creating ''The Adventures of T ...

's volume 13 of ''The Adventures of Tintin

''The Adventures of Tintin'' ( ) is a series of 24 comic albums created by Belgians, Belgian cartoonist Georges Remi, who wrote under the pen name Hergé. The series was one of the most popular European comics of the 20th century. By 2007, a c ...

'': ''The Seven Crystal Balls

''The Seven Crystal Balls'' () is the thirteenth volume of ''The Adventures of Tintin'', the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. The story was serialised daily in ', Belgium's leading francophone newspaper, from December 1943 amidst th ...

'' (1948).

*He is parodied in the 1979 book ''Motel of the Mysteries'' by David Macaulay, with a character in the book named Howard Carson.

*He is a key character in Christian Jacq

Christian Jacq (; born 28 April 1947) is a French author and Egyptology, Egyptologist. He has written several novels about ancient Egypt, notably a five book series about pharaoh Ramses II, a character whom Jacq admires greatly.

Biography

Born i ...

's 1992 book ''The Tutankhamun Affair''.

*James Patterson

James Brendan Patterson (born March 22, 1947) is an American author. Among his works are the '' Alex Cross'', '' Michael Bennett'', '' Women's Murder Club'', '' Maximum Ride'', '' Daniel X'', '' NYPD Red'', '' Witch & Wizard'', '' Private'' and ...

and Martin Dugard's 2010 book ''The Murder of King Tut'' focuses on Carter's search for King Tut's tomb.

*He appears as a main character in Muhammad Al-Mansi Qindeel

Mohamed Mansi Qandil (), also Qindil, Mohammad al-Mansi, etc. (born in 1946 in al-Mahalla al-Kubra) is an Egyptians, Egyptian novelist and author.

Early life

His father was a simple labourer. Qandil went to medical school and worked as a country d ...

's 2010 novel ''A Cloudy Day on the West Side''.

*In Laura Lee Guhrke's 2011 historical romance novel ''Wedding of the Season'', Carter's telegram to the fictional British Egyptologist, the Duke of Sunderland, reports discovering "steps to a new tomb" and creates a climactic conflict.

*He is referenced in Sally Beauman's 2014 novel ''The Visitors'', a re-creation of the hunt for Tutankhamun's tomb in Egypt's Valley of the Kings.

*He is a main character in Philipp Vandenberg's 2001 German-language book ''Der König von Luxor'' (The King Of Luxor).

*He is a recurring figure in the 1975–2010 Amelia Peabody series

The Amelia Peabody series is a series of twenty historical mystery novels and one non-fiction companion volume written by Egyptologist Barbara Mertz (1927–2013) under the pen name Elizabeth Peters. The series is centered on the adventures o ...

, written by Barbara Mertz under the pseudonym Elizabeth Peters. He appears in many of the books, and numbers among the Emersons' circle of friends. In ''The Ape Who Guards the Balance

''The Ape Who Guards the Balance'' is the tenth in a series of historical mystery novels, written by Elizabeth Peters, first published in 1998, and featuring fictional sleuth and archaeologist Amelia Peabody. The story is set in the 1906–1907 d ...

'', for example, he joins them for Christmas dinner shortly after his loss of work for Theodore Davis and his resignation related to the Saqqara Affair, mentioned above.

* Emma Carroll's 2018 novel ''Secrets of a Sun King'' depicts Carter as the primary antagonist in a fictional retelling of the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb. A group of children, in possession of a mysterious jar, seek to return it to its original resting place following a series of troubling consequences.

Other

*A paraphrased extract from Carter's diary of 26 November 1922 is used as theplaintext

In cryptography, plaintext usually means unencrypted information pending input into cryptographic algorithms, usually encryption algorithms. This usually refers to data that is transmitted or stored unencrypted.

Overview

With the advent of comp ...

for Part 3 of the encrypted ''Kryptos

''Kryptos'' is a sculpture by the United States, American artist Jim Sanborn located on the grounds of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) headquarters, the George Bush Center for Intelligence in Langley, Virginia.

Since its dedication on Nove ...

'' sculpture at the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

Headquarters in Langley, Virginia.

*On 9 May 2012, Google

Google LLC (, ) is an American multinational corporation and technology company focusing on online advertising, search engine technology, cloud computing, computer software, quantum computing, e-commerce, consumer electronics, and artificial ...

commemorated Carter's 138th birthday with a Google doodle

Google Doodle is a special, temporary alteration of the logo on Google's homepages intended to commemorate holidays, events, achievements, and historical figures. The first Google Doodle honored the 1998 edition of the long-running annual Bu ...

.

*In 2019, the great-niece of Howard Carter opened a bistro in the town of Swaffham

Swaffham () is a market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Breckland District and England, English county of Norfolk. It is situated east of King's Lynn and west of Norwich.

The civil parish has an area of and in the U ...

, the town in which Carter spent most of his childhood. The bistro has a collection of Egyptian artefacts and a collection of Carter's work, it also bears the name of Carter's discovery, Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun or Tutankhamen, (; ), was an Egyptian pharaoh who ruled during the late Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt. Born Tutankhaten, he instituted the restoration of the traditional polytheistic form of an ...

.

Notes

References

Sources and further reading

* * * * * * * * * *Paine, Michael. ''Cities of the Dead''; fiction (Howard Carter as narrator); copyright by John Curlovich; Charter Books Publishing, 1988 () *Peck, William H. ''The Discoverer of the Tomb of Tutankhamun and the Detroit Institute of Arts''. ''Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities''. Vol. XI, No. 2, March 1981, pp. 65–67 * * * *Vandenberg, Philipp. ''Der vergessene Pharao: Unternehmen Tut-ench-Amun, grösste Abenteuer der Archäologie''. Orbis, 1978 (); translated as ''The Forgotten Pharaoh: The Discovery of Tutankhamun''. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1980 () * *External links

*Five Years' Explorations at Thebes

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Carter, Howard 1874 births 1939 deaths Burials at Putney Vale Cemetery Deaths from lymphoma in England Deaths from Hodgkin lymphoma Archaeologists from London Egyptology English Egyptologists People from Kensington 19th-century British archaeologists 20th-century British archaeologists Tutankhamun Valley of the Kings 1922 archaeological discoveries 1922 in Egypt November 1922 British expatriates in Egypt