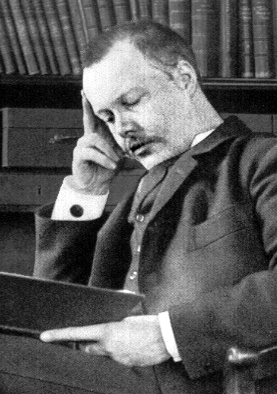

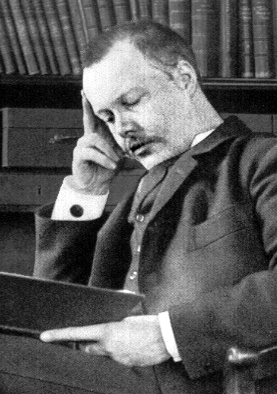

Houston Stewart Chamberlain (; 9 September 1855 – 9 January 1927) was a British-German-French philosopher who wrote works about

political philosophy

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and Political legitimacy, legitimacy of political institutions, such as State (polity), states. This field investigates different ...

and

natural science

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

. His writing promoted German

ethnonationalism

Ethnic nationalism, also known as ethnonationalism, is a form of nationalism wherein the nation and nationality are defined in terms of ethnicity, with emphasis on an ethnocentric (and in some cases an ethnostate/ethnocratic) approach to variou ...

,

antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

,

scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

, and

Nordicism

Nordicism is a racialist ideology which views the "Nordic race" (a historical race concept) as an endangered and superior racial group. Some notable and influential Nordicist works include Madison Grant's book '' The Passing of the Great Rac ...

; he has been described as a "racialist writer". His best-known book, the two-volume ''Die Grundlagen des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts'' (''

The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century''), published 1899, became highly influential in the

pan-Germanic

Pan-Germanism ( or '), also occasionally known as Pan-Germanicism, is a pan-nationalism, pan-nationalist political ideology, political idea. Pan-Germanism seeks to unify all ethnic Germans, German-speaking Europe, German-speaking people, and po ...

''Völkisch'' movements of the early 20th century, and later influenced the antisemitism of

Nazi racial policy. In the early 1920s, Chamberlain met and encouraged

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

: he has been referred to as "Hitler's

John the Baptist

John the Baptist ( – ) was a Jewish preacher active in the area of the Jordan River in the early first century AD. He is also known as Saint John the Forerunner in Eastern Orthodoxy and Oriental Orthodoxy, John the Immerser in some Baptist ...

".

Born in

Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Berkshire to the north, Surrey and West Sussex to the east, the Isle of Wight across the Solent to the south, ...

, in 1884 he settled in

Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, and was later naturalised as a French citizen. He emigrated to

Dresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

in adulthood out of an adoration for composer

Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

. He married

Eva von Bülow, Wagner's daughter, in December 1908, twenty-five years after Wagner's death.

[Eva von Bulow's mother, ]Cosima Wagner

Francesca Gaetana Cosima Wagner (; 24 December 1837 – 1April 1930) was the daughter of the Hungarian composer and pianist Franz Liszt and Franco-German romantic author Marie d'Agoult. She became the second wife of the German composer Richard ...

, was still married to Hans von Bülow

Freiherr Hans Guido von Bülow (; 8 January 1830 – 12 February 1894) was a German conductor, pianist, and composer of the Romantic era. As one of the most distinguished conductors of the 19th century, his activity was critical for establishi ...

when Eva was born – but her biological father was Wagner. During

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Chamberlain sided with Germany against his country of birth. He took German citizenship in 1916.

Early life and education

Houston Stewart Chamberlain was born in

Southsea

Southsea is a seaside resort and a geographic area of Portsmouth, Portsea Island in the ceremonial county of Hampshire, England. Southsea is located 1.8 miles (2.8 km) to the south of Portsmouth's inner city-centre.

Southsea began as a f ...

, Hampshire, England, the son of

Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

William Charles Chamberlain. His mother, Eliza Jane, daughter of

Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

Basil Hall, died before he was a year old, leading to his being brought up by his grandmother in France. His elder brother was professor

Basil Hall Chamberlain. Chamberlain's poor health frequently led him to being sent to the warmer climates of Spain and Italy for the winter. This constant moving about made it hard for Chamberlain to form lasting friendships.

Cheltenham College

Chamberlain's education began at a ''

lycée

In France, secondary education is in two stages:

* ''Collèges'' () cater for the first four years of secondary education from the ages of 11 to 14.

* ''Lycées'' () provide a three-year course of further secondary education for students between ...

'' in

Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of Île-de-France, Île-de-France region in Franc ...

and continued mostly in continental Europe, but his father had planned a military career for his son. At the age of eleven he was sent to

Cheltenham College

Cheltenham College is a public school ( fee-charging boarding and day school for pupils aged 13–18) in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England. The school opened in 1841 as a Church of England foundation and is known for its outstanding linguis ...

, an English

boarding school

A boarding school is a school where pupils live within premises while being given formal instruction. The word "boarding" is used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals. They have existed for many centuries, and now extend acr ...

that produced many Army and Navy officers.

Chamberlain deeply disliked Cheltenham College, and felt lonely and out of place there. The young Chamberlain was "a compulsive dreamer", more interested in the arts than in the military, and he developed a fondness for nature and a near-

mystical

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight ...

sense of self.

[Mosse (1968), p.ix]

Chamberlain grew up in a self-confident, optimistic, Victorian atmosphere that celebrated the nineteenth century as the "

Age of Progress", a world that many Victorians expected to get progressively better with Britain leading the way for the rest of the world. He was supportive of the

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

, and shared the general values of 19th-century British

liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, the right to private property, and equality before the law. ...

such as a faith in progress, of a world that could only get better, of the greatness of Britain as a liberal democratic and capitalist society.

Chamberlain's major interests in his studies at Cheltenham were the natural sciences, especially astronomy.

Chamberlain later recalled: "The stars seemed closer to me, more gentle, more worthy of trust, and more sympathetic – for that is the only word which describes my feelings – than any of the people around me in school. For the stars, I experienced true ''friendship''".

Embracing conservativism

During his youth, Chamberlain – while not entirely rejecting at this point his liberalism – became influenced by the romantic conservative critique of the

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

. Bemoaning the loss of

"Merry Old England", this view argued for a return to a highly romanticized period of English history, with the people living happily in harmony with nature on the land overseen by a benevolent, cultured elite.

In this critique, the Industrial Revolution was seen as a disaster which forced people to live in dirty, overcrowded cities, doing dehumanizing work in factories while society was dominated by a philistine, greedy middle class.

The prospect of serving as an officer in

India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

or elsewhere in the

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

held no attraction for him. In addition, he was a delicate child with poor health. At the age of fourteen he had to be withdrawn from school. After Cheltenham, Chamberlain always felt out of place in Britain, a society whose values Chamberlain felt were not his values, writing in 1876: "The fact may be regrettable but it remains a fact; I have become so completely un-English that the mere thought of England and the English makes me unhappy". Chamberlain travelled to various

spas around Europe, accompanied by a

Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

n tutor, Mr Otto Kuntze, who taught him German and interested him in

German culture

The culture of Germany has been shaped by its central position in Europe and a history spanning over a millennium. Characterized by significant contributions to art, music, philosophy, science, and technology, German culture is both diverse and ...

and

history

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

. Fascinated by Renaissance art and architecture, Chamberlain learned Italian and planned to settle in Florence for a time.

University of Geneva and racial theory

Chamberlain attended the

University of Geneva

The University of Geneva (French: ''Université de Genève'') is a public university, public research university located in Geneva, Switzerland. It was founded in 1559 by French theologian John Calvin as a Theology, theological seminary. It rema ...

, in

French-speaking Switzerland. There he studied under

Carl Vogt, who was a supporter of

racial typology, as well as under chemist

Carl Gräbe, botanist

Johannes Müller Argoviensis

Johann Müller (9 May 1828 – 28 January 1896) was a Swiss botanist who was a specialist in lichens. He published under the name Johannes Müller Argoviensis to distinguish himself from other naturalists with similar names.

Biography

Müller ...

, physicist and

parapsychologist Marc Thury, astronomer

Emile Plantamour, and other professors. Chamberlain's main interests as a student revolved around systematic botany, geology, astronomy, and later the anatomy and physiology of the human body.

[Redesdale (1913), p. vi] In 1881, he earned a baccalaureate in physical and natural sciences.

During his time in Geneva, Chamberlain, who always despised

Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a ...

, came to hate his country more and more, accusing the Prime Minister of taking British life down to what Chamberlain considered to be his extremely low level.

During the early 1880s, Chamberlain was still a Liberal, "a man who approached issues from a firmly

Gladstonian perspective and showed a marked antipathy to the philosophy and policies of British Conservatism". Chamberlain often expressed his disgust with Disraeli, "the man whom he blamed in large measure for the injection of selfish class interest and

jingoism

Jingoism is nationalism in the form of aggressive and proactive foreign policy, such as a country's advocacy for the use of threats or actual force, as opposed to peaceful relations, in efforts to safeguard what it perceives as its national inte ...

into British public life in the next decades".

An early sign of his anti-Semitism came in 1881 when he described the landlords in Ireland affected by the Land Bill as "blood-sucking Jews" (''sic''). The main landowning classes in Ireland then were

gentile

''Gentile'' () is a word that today usually means someone who is not Jewish. Other groups that claim Israelite heritage, notably Mormons, have historically used the term ''gentile'' to describe outsiders. More rarely, the term is used as a synony ...

s. At this stage of his life his anti-Semitic remarks were few and far between.

Botany dissertation: theory of vital force

In Geneva, Chamberlain continued working towards a doctorate in

botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

, but he later abandoned that project due to ill health. The text of what would have been Chamberlain's doctoral dissertation was published in 1897 as ''Recherches sur la sève ascendante'' ("Studies on rising

sap"), but this publication did not culminate in any further academic qualifications.

Chamberlain's book was based on his own experimental observations of water transport in various

vascular plants

Vascular plants (), also called tracheophytes (, ) or collectively tracheophyta (; ), are plants that have lignified tissues (the xylem) for conducting water and minerals throughout the plant. They also have a specialized non-lignified tissue ( ...

. Against the conclusions of

Eduard Strasburger,

Julius von Sachs, and other leading botanists, he argued that his observations could not be explained by the application of the

fluid mechanical theories of the day to the motion of water in the plants'

xylem

Xylem is one of the two types of transport tissue (biology), tissue in vascular plants, the other being phloem; both of these are part of the vascular bundle. The basic function of the xylem is to transport water upward from the roots to parts o ...

conduits. Instead, he claimed that his results evidenced other processes, associated with the action of living matter and which he placed under the heading of a ''force vitale'' ("

vital force").

Chamberlain summarised his thesis in the book's introduction:

In response to Strasburger's complaint that a vitalistic explanation of the ascent of sap "sidesteps the difficulties, calms our concerns, and thus manages to seduce us", Chamberlain retorted that "life is not an explanation, nor a theory, but a fact". Although most plant physiologists currently regard the ascent of sap as adequately explained by the passive mechanisms of

transpirational pull and

root pressure

Root pressure is the transverse osmotic pressure within the cells of a root system that causes sap to rise through a plant stem to the leaves.

Root pressure occurs in the xylem of some vascular plants when the soil moisture level is high either ...

, some scientists have continued to argue that some form of active pumping is involved in the transport of water within some living plants, though usually without referring to Chamberlain's work.

Support of World Ice Theory

Chamberlain was an early supporter of

Hanns Hörbiger's ''

Welteislehre'' ("World Ice Theory"), the theory that most bodies in the

Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Sola ...

are covered with ice. Due in part to Chamberlain's advocacy, this became official

dogma

Dogma, in its broadest sense, is any belief held definitively and without the possibility of reform. It may be in the form of an official system of principles or doctrines of a religion, such as Judaism, Roman Catholicism, Protestantism, or Islam ...

during the

Third Reich

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictat ...

.

Anti-scientific claims

Chamberlain's attitude towards the natural sciences was somewhat ambivalent and contradictory – he later wrote: "one of the most fatal errors of our time is that which impels us to give too great weight to the so-called 'results' of science." Still, his scientific credentials were often cited by admirers to give weight to his political philosophy.

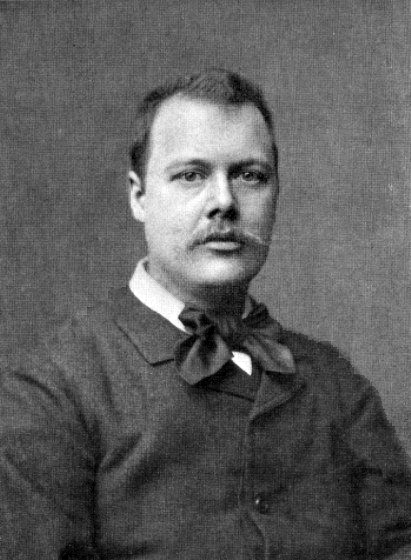

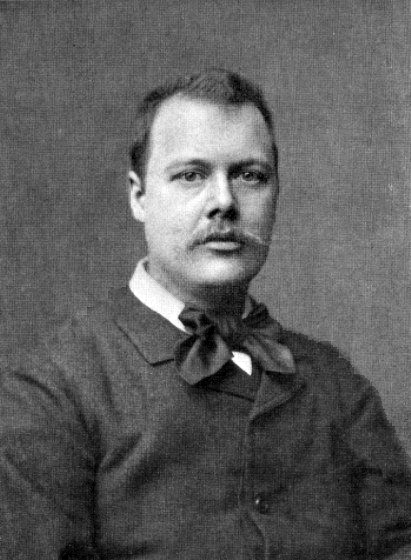

Chamberlain rejected Darwinism, evolution and

social Darwinism

Charles Darwin, after whom social Darwinism is named

Social Darwinism is a body of pseudoscientific theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economi ...

and instead emphasized "

Gestalt

Gestalt may refer to:

Psychology

* Gestalt psychology, a school of psychology

* Gestalt therapy

Gestalt therapy is a form of psychotherapy that emphasizes Responsibility assumption, personal responsibility and focuses on the individual's exp ...

" which he said derived from

Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

.

Wagnerite

An ardent

Francophile

A Francophile is a person who has a strong affinity towards any or all of the French language, History of France, French history, Culture of France, French culture and/or French people. That affinity may include France itself or its history, lang ...

in his youth, Chamberlain had a marked preference for speaking French over English.

[Buruma (2000) p. 219] It was only at the age of twenty three in November 1878, when he first heard the music of

Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

, that Chamberlain became not only a Wagnerite, but an ardent

Germanophile

A Germanophile, Teutonophile, or Teutophile is a person who is fond of Culture of Germany, German culture, Germans, German people and Germany in general, or who exhibits German patriotism in spite of not being either an ethnic German or a German ...

and

Francophobe.

As he put later, it was then he realized the full "degeneracy" of the French culture that he had so admired compared to the greatness of the German culture that had produced Wagner, whom Chamberlain viewed as one of the great geniuses of all time.

In the music of Wagner, Chamberlain found the mystical, life-affirming spiritual force that he had sought unsuccessfully in British and French cultures.

Further increasing his love of Germany was that he had fallen in love with a German woman named Anna Horst.

As Chamberlain's wealthy, elitist family back in Britain objected to him marrying the lower middle-class Horst, this further estranged him from Britain, a place whose people Chamberlain regarded as cold, unfeeling, callous and concerned only with money.

By contrast, Chamberlain regarded Germany as the romantic "land of love", a place whose people had human feelings like love, and whose culture was infused with a special spirituality that brought out the best in humanity.

In 1883–1884, Chamberlain lived in Paris and worked as a stockbroker. Chamberlain's attempts to play the Paris bourse ended in failure as he proved to be inept at business, and much of his hatred of capitalism stemmed from his time in Paris. More happily for him, Chamberlain founded the first Wagner society in Paris and often contributed articles to the ''

Revue wagnérienne'', the first journal in France devoted to Wagner studies. Together with his friend, the French writer

Édouard Dujardin, Chamberlain did much to introduce Wagner to the French, who until then had largely ignored Wagner's music.

Thereafter he settled in

Dresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

, where "he plunged heart and soul into the mysterious depths of

Wagnerian music and philosophy, the

metaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of h ...

works of the Master probably exercising as strong an influence upon him as the musical dramas".

Chamberlain immersed himself in philosophical writings, and became a ''

Völkisch'' author, one of those concerned more with a highly racist understanding of art, culture, civilisation and spirit than with quantitative physical distinctions between groups. This is evidenced by his huge treatise on

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

with its comparisons. It was during his time in Dresden that Chamberlain came to embrace ''völkisch'' thought through his study of Wagner, and from 1884 onwards, anti-Semitic and racist statements became the norm in his letters to his family. In 1888, Chamberlain wrote to his family proclaiming his joy at the death of the Emperor

Friedrich III Frederick III may refer to:

* Frederick III, Duke of Upper Lorraine (died 1033)

* Frederick III, Duke of Swabia (1122–1190)

* Friedrich III, Burgrave of Nuremberg (1220–1297)

* Frederick III, Duke of Lorraine (1240–1302)

* Frederick III o ...

, a strong opponent of anti-Semitism whom Chamberlain called a "Jewish liberal", and rejoicing that his anti-Semitic son

Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor and King of Prussia from 1888 until Abdication of Wilhelm II, his abdication in 1918, which marked the end of the German Empire as well as th ...

was now on the throne. 1888 also saw Chamberlain's first visit to the

Wahnfried to meet

Cosima Wagner

Francesca Gaetana Cosima Wagner (; 24 December 1837 – 1April 1930) was the daughter of the Hungarian composer and pianist Franz Liszt and Franco-German romantic author Marie d'Agoult. She became the second wife of the German composer Richard ...

, the reclusive leader of the Wagner cult. Chamberlain later recalled that Cosima Wagner had "electrified" him as he felt the "deepest love" for Wagner's widow while Wagner wrote to a friend that she felt a "great friendship" with Chamberlain "because of his outstanding learning and dignified character". Wagner came to regard Chamberlain as her surrogate son.

Under her influence, Chamberlain abandoned his previous belief that art was a separate entity from other fields and came to embrace the ''völkisch'' belief of the unity of race, art, nation and politics.

Chamberlain's status as an immigrant to Germany always meant he was to a certain extent an outsider in his adopted country – a man who spoke fluent German, but always with an English accent. Chamberlain tried very hard to be more German than the Germans, and it was his efforts to fit in that led him to ''völkisch'' politics.

Likewise, his anti-Semitism allowed him to define himself as a German in opposition to a group that allegedly threatened all Germans, thereby allowing him to integrate better into the Wagnerian circles with whom he socialized most of the time.

Chamberlain's friend

Hermann Keyserling later recalled that Chamberlain was an eccentric English "individualist" who "never saw Germany as it really is", instead having an idealized, almost mythic view.

This was especially the case as initially the German Wagnerites had rejected Chamberlain, telling him that only Germans could really understand Wagner, statements that very much hurt Chamberlain.

By this time Chamberlain had met Anna Horst, whom he would divorce in 1905 after 28 years of marriage.

Chamberlain was an admirer of Richard Wagner, and wrote several commentaries on his works including ''Notes sur Lohengrin '' ("Notes on Lohengrin") (1892), an analysis of Wagner's drama (1892), and a biography (1895), emphasising in particular the heroic Teutonic aspects in the composer's works. Stewart Spencer, writing in ''Wagner Remembered'', described Chamberlain's edition of Wagner letters as "one of the most egregious attempts in the history of

musicology

Musicology is the academic, research-based study of music, as opposed to musical composition or performance. Musicology research combines and intersects with many fields, including psychology, sociology, acoustics, neurology, natural sciences, ...

to misrepresent an artist by systematically

censoring his correspondence". In particular, Wagner's lively sex life presented a problem for Chamberlain. Wagner had abandoned his first wife Minna, had an open affair with the married woman Mathilde Wesendonck and had started sleeping with his second wife Cosima while she was still married to her first husband.

Chamberlain in his Wagner biography went to considerable lengths to distort these details.

During his time in Dresden, Chamberlain like many other ''völkisch'' activists became fascinated with

Hindu mythology

Hindu mythology refers to the collection of myths associated with Hinduism, derived from various Hindu texts and traditions. These myths are found in sacred texts such as the Vedas, the Itihasas (the ''Mahabharata'' and the ''Ramayan ...

, and learned

Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; stem form ; nominal singular , ,) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in northwest South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural ...

to read the ancient Indian epics like the ''

Vedas

FIle:Atharva-Veda samhita page 471 illustration.png, upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the ''Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas ( or ; ), sometimes collectively called the Veda, are a large body of relig ...

'' and the ''

Upanishads

The Upanishads (; , , ) are late Vedic and post-Vedic Sanskrit texts that "document the transition from the archaic ritualism of the Veda into new religious ideas and institutions" and the emergence of the central religious concepts of Hind ...

'' in their original form.

In these stories about ancient

Aryan

''Aryan'' (), or ''Arya'' (borrowed from Sanskrit ''ārya''), Oxford English Dictionary Online 2024, s.v. ''Aryan'' (adj. & n.); ''Arya'' (n.)''.'' is a term originating from the ethno-cultural self-designation of the Indo-Iranians. It stood ...

heroes conquering the Indian subcontinent, Chamberlain found a very appealing world governed by a rigid caste system with social inferiors firmly locked into their place; full of larger-than-life Aryan gods and aristocratic heroes and a world that focused on the spiritual at the expense of the material.

Since by this time, historians, archaeologists and linguists had all accepted that the Aryans ("noble ones") of Hindu legend were an Indo-European people, Chamberlain had little trouble arguing that these Aryans were in fact Germanic peoples, and modern Germans had much to learn from

Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Hypernymy and hyponymy, umbrella term for a range of Indian religions, Indian List of religions and spiritual traditions#Indian religions, religious and spiritual traditions (Sampradaya, ''sampradaya''s) that are unified ...

.

For Chamberlain the Hindu texts offered a body of pure Aryan thought that made it possible to find the harmony of humanity and nature, which provided the unity of thought, purpose and action that provided the necessary spirituality for Aryan peoples to find true happiness in a world being destroyed by a soulless materialism.

Champion of Wagnerism

In 1889, he moved to

Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

. During this time it is said his ideas on race began taking shape, influenced by the concept of

Teutonic supremacy he believed embodied in the works of Wagner and the French racist writer

Arthur de Gobineau.

[Chase, Allan (1977) ''The Legacy of Malthus: The Social Costs of the New Scientific Racism'' New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 91–92] In his book

''Essai sur l'inégalité des races humaines'', the aristocratic Gobineau, who had an obsessive hatred of commoners, had developed the theory of an Aryan master race. Wagner was greatly influenced by Gobineau's theories, but could not accept Gobineau's theory of inevitable racial decay amongst what was left of the "Aryan race", instead preferring the idea of racial regeneration of the Aryans. The Franco-Israeli historian

Saul Friedländer

Saul Friedländer (; born October 11, 1932) is a Czech-born Jewish historian and a professor emeritus of history at UCLA.

Biography

Saul Friedländer was born in Prague to a family of German-speaking Jews. He was raised in France and lived thr ...

opined that Wagner was the inventor of a new type of anti-Semitism, namely "redemptive anti-semitism".

[Friedländer (1998), p. 87]

In 1908, twenty-five years after Wagner's death, Chamberlain married Eva von Bülow-Wagner,

Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt (22 October 1811 – 31 July 1886) was a Hungarian composer, virtuoso pianist, conductor and teacher of the Romantic music, Romantic period. With a diverse List of compositions by Franz Liszt, body of work spanning more than six ...

's granddaughter and Richard Wagner's daughter (Wagner had started fathering children by Cosima while she was still married to Hans von Bülow – despite her surname, Eva was actually Wagner's daughter). The next year he moved to Germany and became an important member of the "

Bayreuth Circle" of German nationalist intellectuals. As an ardent Wagnerite, Chamberlain saw it as his life's mission to spread the message of racial hatred which he believed Wagner had advocated.

[Friedländer (1998), p. 89] Chamberlain explained his work in promoting the Wagner cult as an effort to cure modern society of its spiritual ills that he claimed were caused by capitalism, industrialisation, materialism, and urbanisation. Chamberlain wrote about modern society in the 1890s:

Like a wheel that spins faster and faster, the increasing rush of life drives us continually further apart from each other, continually further from the 'firm ground of nature'; soon it must fling us out into empty nothingness.

In another letter, Chamberlain stated:

If we do not soon pay attention to Schiller's thought regarding the transformation from the state of Need into the Aesthetic State, then our condition will degenerate into a boundless chaos of empty talk and arms foundries. If we do not soon heed Wagner's warning—that mankind must awaken to a consciousness of its "pristine holy worth"—then the Babylonian tower of senseless doctrines will collapse on us and suffocate the moral core of our being forever.

In Chamberlain's view, the purpose of the Wagner cult was nothing less than the salvation of humanity.

As such, Chamberlain became engulfed in the "redemptive anti-semitism" that was at the core of both Wagner's worldview and of the Wagner cult.

Vienna years

In September 1891, Chamberlain visited

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina, sometimes known as Bosnia-Herzegovina and informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeast Europe. Situated on the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula, it borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to th ...

. Chamberlain had been commissioned by the Austrian government to write propaganda glorying its

colonial rule of Bosnia-Herzegovina for a Geneva newspaper. Chamberlain's articles about Bosnia reveal his increasing preference for dictatorship over democracy, with Chamberlain praising the Austrians for their utterly undemocratic rule.

Chamberlain wrote that what he had seen in Bosnia-Herzegovina was the perfect example of Wagner's dictum: "Absolute monarch – free people!"

Chamberlain declared that the Bosnians were extremely lucky not to have the shambles and chaos of a democratic "parliamentary regime", instead being ruled by an idealist, enlightened dictatorship that did what was best for them.

Equally important in Chamberlain's Bosnian articles was his celebration of "natural man" who lived on the land as a small farmer as opposed to what Chamberlain saw as the corrupt men who lived in modern industrial, urban society.

At the time Chamberlain visited Bosnia-Herzegovina, the provinces had been barely touched by modernization, and for the most part, Bosnians continued to live much as their ancestors had done in the Middle Ages. Chamberlain was enchanted with what he saw, and forgetting for the moment that the purpose of his visit was to glorify Austrian rule, expressed much sadness in his articles that the "westernization" being fostered by the Austrians would destroy the traditional way of life in Bosnia. Chamberlain wrote:

he Bosnian peasantbuilds his house, he makes his shoes, and plough, etc.; the woman weaves and dyes the stuffs and cooks the food. When we have civilized these good people, when we have taken from them their beautiful costumes to be preserved in museums as objects of curiosity, when we have ruined their national industries that are so perfect and so primitive, when contact with us has destroyed the simplicity of their manner—then Bosnia will no longer be interesting to us.

Chamberlain's awe and pride in the tremendous scientific and technological advances of the 19th century were always tempered with an extremely strong nostalgia for what he saw as the simpler, better and more innocent time when people lived on the land in harmony with nature.

In his heart, Chamberlain was always a romantic conservative who idealised the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

and was never quite comfortable with the changes wrought by the

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

.

In Bosnia, Chamberlain saw an essentially medieval society that still moved to the ancient rhythm of life that epitomized his pastoral ideal. Remembering Bosnia several years later, Chamberlain wrote:

The spirit of a natural man, who does everything and must create everything for himself in life, is decidedly more universal and more harmoniously developed than the spirit of an industrial worker whose whole life is occupied with the manufacturing of a single object ... and that only with the aid of a complicated machine, whose functioning is quite foreign to him. A similar degeneration is taking place amongst peasants: an American farmer in the Far West is today only a kind of subordinate engine driver. Also among us in Europe it becomes every day more impossible for a peasant to exist, for agriculture must be carried out in "large units"—the peasant consequently becomes increasingly like an industrial worker. His understanding dries up; there is no longer an interaction between his spirit and surrounding Nature.

Chamberlain's nostalgia for a pre-industrial way of life that he expressed so strongly in his Bosnia articles earned him ridicule, as many believed that he had an absurdly idealized and romanticized view of the rural life that he never experienced first-hand.

In 1893, Chamberlain received a letter from Cosima Wagner telling him that he had to read Gobineau's ''Essai sur l'inégalité des races humaines''. Chamberlain accepted Gobineau's belief in an Aryan master-race, but rejected his pessimism, writing that Gobineau's philosophy was "the grave of every attempt to deal practically with the race question and left only one honorable solution, that we at once put a bullet through our heads".

[Buruma (2000), p. 220] Chamberlain's time in Vienna shaped his anti-Semitism and Pan-Germanism. Despite living in Vienna from 1889 to 1909, when he moved to

Bayreuth

Bayreuth ( or ; High Franconian German, Upper Franconian: Bareid, ) is a Town#Germany, town in northern Bavaria, Germany, on the Red Main river in a valley between the Franconian Jura and the Fichtel Mountains. The town's roots date back to 11 ...

, Chamberlain had nothing but contempt for the multi-ethnic, multi-religious Habsburg empire, taking the viewpoint that the best thing that could happen to the Austrian empire would be for it to be annexed by Germany to end the (chaos of the peoples). Vienna had a large Jewish population, and Chamberlain's time in Vienna may have been the first time in his life when he actually encountered Jews. Chamberlain's letters from Vienna constantly complain about how he was having to deal with Jews, every one of whom he detested. In 1894 after visiting a spa, Chamberlain wrote: "Unfortunately like everything else ... it has fallen into the hands of the Jews, which includes two consequences: every individual is bled to the utmost and systematically, and there is neither order nor cleanliness."

In 1895, he wrote:

However, we shall have to move soon anyway, for our house having been sold to a Jew ... it will soon be impossible for decent people to live in it ... Already the house being almost quite full of Jews, we have to live in a state of continual warfare with the vermin which is a constant and invariable follower of this chosen people even in the most well-to-do classes.

In another letter of 1895, Chamberlain wrote he was still influenced by French anarchist

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, ; ; 1809 – 19 January 1865) was a French anarchist, socialist, philosopher, and economist who founded mutualist philosophy and is considered by many to be the "father of anarchism". He was the first person to ca ...

's critique of the Jews as mindlessly materialistic, writing that Proudhon was "one of the most acute minds of the century" and "I find many points of contact between the Wagner-Schiller mode of thought and the anarchism of Proudhon." At the same time, Chamberlain's marriage to Anna began to fall apart, as his wife was frequently sick and though she assisted her husband with his writings, he did not find her very intellectually stimulating. Chamberlain started to complain more and more that his wife's frequent illnesses forced him to tend to her and were holding back his career.

Though Chamberlain consistently remained supportive of

German imperialism, he frequently expressed hostile views towards the

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

; Chamberlain viewed Britain as world's most frequent aggressor, a view he expressed more vehemently at the tail end of the 19th century.

In 1895, Chamberlain wrote to his aunt about the

Hamidian massacres

The Hamidian massacres also called the Armenian massacres, were massacres of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire in the mid-1890s. Estimated casualties ranged from 100,000 to 300,000, Akçam, Taner (2006) '' A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide a ...

in the Ottoman Empire during 1894–96:

The Armenian insurrection f 1894with the inevitable retaliation of massacres and persecution (of course ''enormously exaggerated'' by those greatest liars in creation, backed by their worthy friends the English journalists) was all got up at the precise moment when English politics required a "diversion".

In 1896, Chamberlain wrote to his aunt:

The English press is the most insufferably arrogant, generally ignorant, the most passionately one-sided and narrow-minded in its judgments that I know; it is the universal ''bully'', always laying down the law for everybody, always speaking as if it were umpire of the universe, always abusing everybody all round and putting party spirit in all its judgments, envenoming thus the most peaceful discussions. It is this and this only which has made England hated all the world over. During the whole year 1895, I never opened an English newspaper without finding ''War'' predicated or threatened—No other nation in the world has wanted war or done anything but pray for peace—England alone, the world's bully, has been stirring it up on all sides.

During the 1890s, Chamberlain was an outspoken critic of British policies in

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

, writing to his uncle in 1898:

At the time of the

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

, Chamberlain privately expressed support for the cause of the

Boers

Boers ( ; ; ) are the descendants of the proto Afrikaans-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled the Dutch ...

, although he also expressed regret over "white men" fighting each other at a time when Chamberlain believed that

white supremacy

White supremacy is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White supremacy has roots in the now-discredited doctrine ...

around the world was being threatened by the alleged "

Yellow Peril

The Yellow Peril (also the Yellow Terror, the Yellow Menace, and the Yellow Specter) is a Racism, racist color terminology for race, color metaphor that depicts the peoples of East Asia, East and Southeast Asia as an existential danger to the ...

".

In July 1900, Chamberlain wrote to his aunt:

One thing I can clearly see, that is, that it is criminal for Englishmen and Dutchmen to go on murdering each other for all sorts of sophisticated reasons, while the Great Yellow Danger overshadows us white men and threatens destruction ... The fact that a tiny nation of peasants absolutely untrained in the conduct of war, has been able to keep the whole united empire at bay for months, and has only been overcome—and ''has'' it been overcome?—by sending out an army superior in number to the whole population including women and children, has lowered respect for England beyond anything you can imagine on your side of the water, and will certainly not remain lost on the minds of those countless millions who have hitherto been subdued by our prestige only.

Chamberlain seized upon the fact that some of the

Randlords

The Randlords () were the capitalists who controlled the diamond and gold mining industries in South Africa from the 1870s to the First World War.

A small number of Europe, European financiers, largely of the same generation, gained control of the ...

were Jewish to argue in his letters to Cosima Wagner that the war was a case of Anglo-Jewish aggression against the Germanic Afrikaners.

As a leading Wagnerite in Vienna, Chamberlain befriended a number of other prominent Wagnerites, such as

Prince Hohenhohe-Langenburg,

Ludwig Schemann, Georg Meurer, and Baron

Christian von Ehrenfels. The most important friendship that Chamberlain made during his time in Vienna was with German Ambassador to Austria-Hungary,

Philipp, Prince of Eulenburg, who shared Chamberlain's love of Wagnerian music. Eulenburg was also an anti-Semite, an Anglophobe and a convinced enemy of democracy who found much to admire in Chamberlain's anti-Semitic, anti-British and anti-democratic writings.

''Die Grundlagen'' (''The Foundations'')

In February 1896, the Munich publisher

Hugo Bruckmann

Hugo Bruckmann (13 October 1863, in Munich – 3 September 1941, in Munich) was a German publisher. He became a supporter of Adolf Hitler and served as a Nazi Party deputy in the '' Reichstag'' from 1932 until his death.

Biography

Bruckmann was ...

, a leading ''völkisch'' activist who was later to publish ''

Mein Kampf

(; ) is a 1925 Autobiography, autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The book outlines many of Political views of Adolf Hitler, Hitler's political beliefs, his political ideology and future plans for Nazi Germany, Ge ...

'', commissioned Chamberlain to write a book summarizing the achievements of the 19th century.

In October 1899, Chamberlain published his most famous work, ''Die Grundlagen des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts'', in German. ''The Foundations'' is a pseudo-scientific "racial history" of humanity from the emergence of the first civilizations in the ancient Near East to the year 1800. It argues that all of the "foundations" of the 19th century, which saw huge economic, scientific and technological advances in the West, were the work of the "Aryan race".

''Die Grundlagen'' was only the first volume of an intended three-volume history of the West, with the second and third volumes taking up the story of the West in the 19th century and the looming war for world domination in the coming 20th century between the Aryans on one side vs. the Jews, blacks and Asians on the other side.

Chamberlain never wrote the third volume, much to the intense annoyance of

Cosima Wagner

Francesca Gaetana Cosima Wagner (; 24 December 1837 – 1April 1930) was the daughter of the Hungarian composer and pianist Franz Liszt and Franco-German romantic author Marie d'Agoult. She became the second wife of the German composer Richard ...

, who was upset that ''Die Grundlagen'' stopped in 1800 before Wagner was born, and thus omitted her husband. The book argued that

Western civilisation is deeply marked by the influence of

Teutonic peoples.

Peoples defined as Aryans

Chamberlain grouped all European peoples – not just

Germans

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...

, but

Celts

The Celts ( , see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples ( ) were a collection of Indo-European languages, Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient Indo-European people, reached the apoge ...

,

Slavs

The Slavs or Slavic people are groups of people who speak Slavic languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout the northern parts of Eurasia; they predominantly inhabit Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, and ...

,

Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

, and

Latins

The term Latins has been used throughout history to refer to various peoples, ethnicities and religious groups using Latin or the Latin-derived Romance languages, as part of the legacy of the Roman Empire. In the Ancient World, it referred to th ...

– into the "

Aryan race

The Aryan race is a pseudoscientific historical race concepts, historical race concept that emerged in the late-19th century to describe people who descend from the Proto-Indo-Europeans as a Race (human categorization), racial grouping. The ter ...

", a race built on the ancient

Proto-Indo-European

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. No direct record of Proto-Indo-European exists; its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-Euro ...

culture. In fact, he even included the

Berber people

Berbers, or the Berber peoples, also known as Amazigh or Imazighen, are a diverse grouping of distinct ethnic groups indigenous to North Africa who predate the arrival of Arabs in the Maghreb. Their main connections are identified by their u ...

of North Africa.

At the helm of the Aryan race, and, indeed, all races, according to Chamberlain, were the Germanic or Teutonic peoples, who had best preserved the Aryan blood.

[Field (1981), p. 223] Chamberlain used the terms Aryan, Indo-European and Indo-Germanic interchangeably, but he emphasised that purest Aryans were to be found in Central Europe and that in both France and Russia miscegenation had diluted the Aryan blood. Much of Chamberlain's theory about the superiority of the Aryan race was taken from the writings of Gobineau, but there was a crucial difference in that Gobineau had used the Aryan race theory as a way of dividing society between an Aryan nobility vs. racially inferior commoners whereas Chamberlain used the Aryan racial theory as a way of uniting society around its supposed common racial origins.

Aryan race virtues

Everything that Chamberlain viewed as good in the world was ascribed to the Aryans. For an example, in ''The Foundations'', Chamberlain explained at considerable length that

Jesus Christ

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

could not possibly be a Jew, and very strongly implied that Christ was an Aryan.

Chamberlain's tendency to see everything good as the work of the Aryans allowed him to claim whoever he approved of for the Aryan race, which at least was part of the appeal of the book in Germany when it was published in 1899. Chamberlain claimed all of the glories and achievements of ancient Greece and Rome as due entirely to Aryan blood.

Chamberlain wrote that ancient Greece was a "lost ideal" of beautiful thought and art that the modern Germans were best placed to recover if only the German people could embrace Wagner.

Chamberlain praised Rome for its militarism, civic values, patriotism, respect for the law and reverence for the family as offering the best sort of Aryan government.

Reflecting his opposition to

feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

, Chamberlain lamented how modern women were not like the submissive women of ancient Rome whom he claimed were most happy in obeying the wills of their husbands.

Chamberlain asserted that Aryans and Aryans alone are the only people in the entire world capable of creating beautiful art and thinking great thoughts, so he claimed all of the great artists, writers and thinkers of the West as part of one long glorious tradition of Aryan art and thought, which Chamberlain planned to have culminate with the life-changing, racially regenerating music of Richard Wagner in the 19th century. As the British historian

George Peabody Gooch wrote, here was "a glittering vision of mind and muscle, of large scale organization, of intoxicating self-confidence, of metallic brilliancy, such as Europe has never seen".

The antithesis of the heroic Aryan race with its vital, creative life-improving qualities was the "Jewish race", whom Chamberlain presented as the inverse of the Aryan. Every positive quality the Aryans had, the Jews had the exact opposing negative quality. The American historian Geoffrey Field wrote:

To each negative "Semitic" trait Chamberlain counter-posed a Teutonic virtue. Kantian moral freedom took the place of political liberty and egalitarianism. Irresponsible Jewish capitalism was sharply distinguished from the vague ideal of Teutonic industrialism, a romantic vision of an advanced technological society which had somehow managed to retain the ''Volksgemeinschaft

''Volksgemeinschaft'' () is a German expression meaning "people's community", "folk community", Richard Grunberger, ''A Social History of the Third Reich'', London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971, p. 44. "national community", or "racial community" ...

'', cooperation and hierarchy of the medieval guilds. The alternative to Marxism was "ethical socialism", such as that described by Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, theologian, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VII ...

, "one of the most exquisite scholars ever produced by a Teutonic people, of an absolutely aristocratic, refined nature". In the rigidly elitist, disciplined society of ''Utopia'' with its strong aura of Christian humanism, Chamberlain found an approximation of his own nostalgic, communal ideal. "The gulf separating More from Marx," he wrote, "is not the progress of time, but the contrast between Teuton and Jew."

Jewish wars claim

Chamberlain announced in ''The Foundations'' that "all the wars" in history were "so peculiarly connected with Jewish financial operations".

Chamberlain warned that the aim of the Jew was "to put his foot upon the neck of all nations of the world and be Lord and possessor of the whole earth".

As part of their plans to destroy Aryan civilization, Chamberlain wrote: "Consider, with what mastery they use the law of blood to extend their power."

Chamberlain wrote that Jewish women were encouraged to marry Gentiles while Jewish men were not, so the male line "remained spotless ... thousands of side-branches are cut off and employed to infect Indo-Europeans with Jewish blood."

In his account of the

Punic wars

The Punic Wars were a series of wars fought between the Roman Republic and the Ancient Carthage, Carthaginian Empire during the period 264 to 146BC. Three such wars took place, involving a total of forty-three years of warfare on both land and ...

between "Aryan Rome" and "Semitic Carthage", Chamberlain praised the Romans for their

total destruction of Carthage in 146 BC at the end of the

Third Punic War

The Third Punic War (149–146 BC) was the third and last of the Punic Wars fought between Carthage and Rome. The war was fought entirely within Carthaginian territory, in what is now northern Tunisia. When the Second Punic War ended in 20 ...

as an example of how Aryans should deal with Semites.

Later, Chamberlain argued that the Romans had become too tolerant of Semites like the Jews, and this was the cause of the downfall of the Roman empire.

As such, the destruction of the Western Roman Empire by the Germanic peoples was merely an act of liberation from the ("Chaos of the Peoples") that the Roman empire had become.

Theories of Jewish conspiracy

The ultimate aim of the Jew, according to Chamberlain, was to create a situation where "there would be in Europe only a single people of pure race, the Jews, all the rest would be a herd of pseudo-Hebraic mestizos, a people beyond all doubt degenerate physically, mentally and morally."

As part of their plans to destroy the Aryans, Chamberlain claimed that the Jews had founded the

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, which only preached a "Judaized" Christianity that had nothing to do with the Christianity created by the Aryan Christ.

Some historians have argued that ''The Foundations'' are actually more anti-Catholic than anti-Semitic, but this misses the point that the reason why Chamberlain attacked the Catholic Church so fiercely was because he believed the Papacy was controlled by the Jews.

Chamberlain claimed that in the 16th century the Aryan Germans under the leadership of

Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

had broken away from the corrupt influence of Rome, and so laid the foundations of a "Germanic Christianity".

Chamberlain claimed that the natural and best form of government for Aryans was a dictatorship, and so he blamed the Jews for inventing democracy as part of their plans for destroying the Aryans.

In the same way, Chamberlain blamed capitalism – which he saw as a very destructive economic system – as something invented by the Jews to enrich themselves at the expense of the Aryans while at the same time crediting the Jews with inventing socialism with its message of universal human equality as a cunning Jewish stratagem to divert attention away from all the economic devastation wrought by Jewish financiers.

Chamberlain had a deep dislike of the Chinese, and in ''The Foundations'' he announced that

Chinese civilization had been founded by the Jews.

Jewish race – not religion

The Franco-Israeli historian

Saul Friedländer

Saul Friedländer (; born October 11, 1932) is a Czech-born Jewish historian and a professor emeritus of history at UCLA.

Biography

Saul Friedländer was born in Prague to a family of German-speaking Jews. He was raised in France and lived thr ...

described ''The Foundations'' – with its theory of two "pure" races left in the world, namely the German and Jewish locked into a war for world domination which could only end with the complete victory of one over the other – as one of the key texts of "redemptive anti-semitism".

Because Chamberlain viewed Jews as a race, not a religion, Chamberlain argued the conversion of Jews was not a "solution" to the "Jewish Question", stating Jewish converts to Christianity were still Jews. Dutch journalist

Ian Buruma

Ian Buruma (born 28 December 1951) is a Dutch writer and editor who lives and works in the United States. In 2017, he became editor of ''The New York Review of Books'', but left the position in September 2018.

Much of his writing has focused on t ...

wrote:

Wagner himself, like Luther, still believed that a Jew could, as he put it with his customary charm, "annihilate" his Jewishness by repudiating his ancestry, converting and worshiping at the shrine of Bayreuth. So in theory a Jew could be a German ... But to the mystical chauvinists, like Chamberlain, who took a tribal view of Germanness, even radical, Wagnerian assimilation could never be enough: the Jew was an alien virus to be purged from the national bloodstream. The more a Jew took on the habits and thoughts of his gentile compatriots, the more he was to be feared.

Leaving "the solution" to the reader

Chamberlain did not advocate the extermination of Jews in ''The Foundations''; indeed, despite his determination to blame all of the world's problems on the Jews, Chamberlain never proposed a solution to this perceived problem.

Instead, Chamberlain made the cryptic statement that after reading his book, his readers would know best about how to devise a "solution" to the "Jewish Question".

Friedländer has argued that if one were to seriously take up the theories of "redemptive anti-semitism" proposed in ''The Foundations'', and push them to their logical conclusion, then inevitably one would reach the conclusion that genocide might be a perfectly acceptable "solution" to the "Jewish Question".

Friedländer argued that there is an implied genocidal logic to ''The Foundations'' as Chamberlain argued that Jews were a race apart from the rest of humanity; that evil was embedded within the genes of the Jews, and so the Jews were born evil and remained evil until they died.

''The Foundations'' sales, reviews and acceptance

''The Foundations'' sold well: eight editions and 60,000 copies within 10 years, 100,000 copies by the outbreak of World War I and 24 editions and more than a quarter of a million copies by 1938.

The success of ''The Foundations'' after it was published in October 1899 made Chamberlain into a celebrity intellectual.

The popularity of ''The Foundations'' was such that many ''Gymnasium'' (high school) teachers in the Protestant parts of Germany made'' Die Grundlagen'' required reading.

Conservative and National Liberal newspapers gave generally friendly reviews to ''The Foundations''. newspapers gave overwhelming positive reviews to ''The Foundations'', with many reviewers calling it one of the greatest books ever written. Liberal and Social Democratic newspapers gave the book extremely poor reviews with reviewers complaining of an irrational way of reasoning in ''The Foundations'', noting that Chamberlain quoted the writings of Goethe out of context in order to give him views that he had not held, and that the entire book was full of an obsessive anti-Semitism which they found extremely off-putting. Because of Chamberlain's anti-Catholicism, Catholic newspapers all published very hostile reviews of ''The Foundations'', though Catholic reviewers rarely faulted ''Die Grundlagen'' for its anti-Semitism. More orthodox Protestant newspapers were disturbed by Chamberlain's call for a racialized Christianity.

German Jewish groups like the ''Centralverein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens'' and the ''Verein zur Abwehr des Antisemitismus'' repeatedly issued statements in the early 20th century that the popularity of ''The Foundations'' was a major source of concern for them, noting that ''Die Grundlagen'' had caused a major increase in anti-Semitism with many German Jews now finding themselves the objects of harassment and sometimes violence.

The German Jewish journalist Moritz Goldstein wrote in 1912 that he had become a Zionist because he believed there was no future for Jews in Germany, and one of the reasons for that belief was:

Chamberlain believes what he says and for that very reason his distortions shock me. And thousands more believe as he does for the book goes one edition after another and I would still like to know if many Germanic types, whose self-image is pleasantly indulged by this theory, are able to remain critical enough to question its countless injustices and errors?

Discrimination of Jews following the book

German universities were hotbeds of activity in the early 20th century, and ''The Foundations'' was extremely popular on university campuses, with many university clubs using ''The Foundations'' as a reason to exclude Jewish students.

Likewise, military schools were centers of ''völkisch'' thought in the early 20th century, and so ''The Foundations'' was very popular with officer cadets; though since neither the Navy nor the Prussian, Bavarian, Saxon and Württemberg armies accepted Jewish officer candidates, ''Die Grundlagen'' did not lead to Jews being excluded.

Evangelist of race

Visit to England and attack on its Jews

In 1900, for the first time in decades, Chamberlain visited Britain.

Writing to

Cosima Wagner

Francesca Gaetana Cosima Wagner (; 24 December 1837 – 1April 1930) was the daughter of the Hungarian composer and pianist Franz Liszt and Franco-German romantic author Marie d'Agoult. She became the second wife of the German composer Richard ...

from London, Chamberlain stated sadly that ''his'' Britain, the Britain of aristocratic rule, hard work and manly courage, the romanticized

"Merry Old England" of his imagination was no more; it had been replaced by what Chamberlain saw as a materialist, soulless society, atomized into individuals with no sense of the collective purpose and dominated by greed.

Chamberlain wrote that since the 1880s Britain had "chosen the service of Mammon", for which he blamed the Jews, writing to Wagner: "This is the result, when one has studied politics with a Jew for a quarter century."

The "Jew" Chamberlain was referring to was

Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a central role in the creat ...

, whom Chamberlain had always hated.

Chamberlain declared in his letter that all British businessmen were now dishonest; the middle class, smug and stupid; small farmers and shops were no longer able to compete with Jewish-owned big business; and the monarchy was "irretrievably weakened" by social change.

German superiority to rule the world

In the summer of 1900, Chamberlain wrote an essay in the magazine ''Jugend'', where he declared that: "The reign of Wilhelm II has the character of the dawning of a new day." Chamberlain went on to write that Wilhelm was "in fact the first German Kaiser" who knew his mission was to "ennoble" the world by spreading "German knowledge, German philosophy, German art and—if God wills—German religion. Only a Kaiser who undertakes this task is a true Kaiser of the German people." To allow Germany to become a world power, Chamberlain called for the ''Reich'' to become the world's greatest sea power, as Chamberlain asserted that whatever power rules the seas also rules the world.

[Röhl (2004), p. 1041]

Kaiser Wilhelm II

In early 1901, the German Emperor

Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor and King of Prussia from 1888 until Abdication of Wilhelm II, his abdication in 1918, which marked the end of the German Empire as well as th ...

read ''The Foundations'' and was immensely impressed.

The Imperial Grand Chamberlain at the court, Ulrich von Bülow, wrote in a letter to a friend in January 1901 that the Kaiser was "studying the book a second time page by page".

In November 1901, Chamberlain's friend, the German diplomat and courtier

Philipp, Prince of Eulenburg, who happened to be the best friend of Wilhelm II, introduced Chamberlain to the Kaiser.

Chamberlain and Wilhelm first met at Eulenburg's estate at Liebenberg.

To reach Liebenberg from Vienna, Chamberlain had first to take a train to Berlin, and then board another train to Liebenberg.

Chamberlain's meeting with the Kaiser was considered so important that when Chamberlain reached Berlin, he was met by the Chancellor Prince

Bernhard von Bülow

Bernhard Heinrich Karl Martin, Prince of Bülow ( ; 3 May 1849 – 28 October 1929) was a German politician who served as the chancellor of the German Empire, imperial chancellor of the German Empire and minister-president of Prussia from 1900 to ...

, who joined him on the trip to Liebenberg.

During the train ride, Bülow and Chamberlain had a long discussion about ''The Foundations''.

When he met Chamberlain for the first time, Wilhelm told him: "I thank you for what you have done for Germany!"

The next day, Eulenburg wrote to a friend that the Emperor "stood completely under the spell of

hamberlain whom he understood better than any of the other guests because of his thorough study of ''The Foundations''".

Until Chamberlain's death, he and Wilhelm had what the American historian Geoffrey Field called "a warm, personal bond", which was expressed in a series of "elaborate, wordy letters".

The Wilhelm–Chamberlain letters were full of "the perplexing thought world of mystical and racist conservatism". They ranged far and wide in subject matter: the ennobling mission of the Germanic race, the corroding forces of

Ultramontanism

Ultramontanism is a clerical political conception within the Catholic Church that places strong emphasis on the prerogatives and powers of the Pope. It contrasts with Gallicanism, the belief that popular civil authority—often represented b ...

, materialism and the "destructive poison" of were favorite themes. Other subjects often discussed in the Wilhelm-Chamberlain letters were the dangers posed to the by the "

Yellow Peril

The Yellow Peril (also the Yellow Terror, the Yellow Menace, and the Yellow Specter) is a Racism, racist color terminology for race, color metaphor that depicts the peoples of East Asia, East and Southeast Asia as an existential danger to the ...

", "Tartarized Slavdom", and the "black hordes". Wilhelm's later concept of "Juda-England", of a decaying Britain sucked dry by Jewish capitalists, owed much to Chamberlain.

[Buruma (2000) p. 221] In 1901, Wilhelm informed Chamberlain in a letter that: "God sent your book to the German people, just as he sent you personally to me, that is my unshakably firm conviction."

[Röhl (2004), p. 205] Wilhelm went on to praise Chamberlain as his "comrade-in-arms and ally in the struggle for Teutons against Rome, Jerusalem, etc."

The Dutch journalist

Ian Buruma

Ian Buruma (born 28 December 1951) is a Dutch writer and editor who lives and works in the United States. In 2017, he became editor of ''The New York Review of Books'', but left the position in September 2018.

Much of his writing has focused on t ...

described Chamberlain's letters to the Kaiser as pushing his "Anglophobic, anti-Semitic, Germanophile ideas to the point of murderous lunacy".

The liberal ''Berliner Zeitung'' newspaper complained in an editorial of the close friendship between Wilhelm II and such an outspoken racist and anti-Semite as Chamberlain, stating this was a real cause for concern for decent, caring people both inside and outside Germany.

For Wilhelm, all pride about being German had a certain ambivalence, as he was in fact half-British.

[Buruma (2000) pp. 210–211] In an age of ultra-nationalism with identities being increasingly defined in racial terms, his mixed heritage imposed considerable psychological strain on Wilhelm, who managed at one and the same time to be both an Anglophile and Anglophobe; he was a man who both loved and hated the British, and his writings about the land of his mother displayed both extreme admiration and loathing.

Buruma observed that for all his much-vaunted beliefs in public about the superiority of everything German, in private Wilhelm often displayed signs of an inferiority complex to the British, as if he really felt deep down that it was Britain, not Germany, that was the world's greatest country.

For Wilhelm, someone like Chamberlain, the Englishman who came to Germany to praise the Fatherland as the world's greatest nation, and who had "scientifically" proven that "fact" in ''The Foundations'', was a "dream come true" for him. Writing about the Chamberlain-Wilhelm relationship, Field stated:

Chamberlain helped place Wilhelm's tangled and vaguely formulated fears of Pan Slavism, the black and yellow "hordes", Jews, Ultramontanes, Social Democrats, and free-thinkers to a global and historical framework copiously footnoted and sustained by a vast array of erudite information. He elevated the Emperor's dream of a German mission into an elaborate vision of divinely ordained, racial destiny. The lack of precision, the muddle, and logical flaws that are so apparent to modern readers of ''The Foundations'' did not bother Wilhelm: he eagerly submitted to its subjective, irrational style of reasoning. ... And if the Kaiser was a Prussian with an ingrained respect for English values and habits, Chamberlain was just as much an Englishman who was deeply ambivalent about his own birthplace and who revered German qualities and Prussian society. Almost unconsciously, as his vast correspondence shows, he adopted an obsequious, scraping tone when addressing the lowliest of Prussian army officers. If Wilhelm was drawn to the very Englishness of Chamberlain, the author of ''The Foundations'' saw in the Hohenzollern prince—at least until the World War—the very symbol of his idealized .

Chamberlain frequently wrote to an appreciative and admiring Wilhelm telling him that it was only the noble "German spirit" which was saving the world from being destroyed by a "deracinated Yankee-Anglo-Jewish materialism". Finally, Wilhelm was also a Wagnerite and found much to admire in Chamberlain's writings praising Wagner's music as a mystical, spiritual life-force that embodied all that was great about the "German spirit".

'The Foundations' book success

The success of ''The Foundations'' made Chamberlain famous all over the world. In 1906, the Brazilian intellectual

Sílvio Romero cited Chamberlain together with

Otto Ammon,

Georges Vacher de Lapouge and

Arthur de Gobineau as having proved that the blond "dolichocephalic" people of northern Europe were the best and greatest race in the entire world, and urged that Brazil could become a great nation by a huge influx of German immigrants who would achieve the

''embranquecimento'' (whitening) of Brazil. Chamberlain received invitations to lecture on his racial theories at

Yale