Hongwu Emperor's Reforms on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The reforms of the Hongwu Emperor, the founder and first emperor of the

In an attempt to combat the inflation that occurred during the late Yuan dynasty, the Hongwu Emperor attempted to reintroduce the use of copper coins, following the practice of the previous

In an attempt to combat the inflation that occurred during the late Yuan dynasty, the Hongwu Emperor attempted to reintroduce the use of copper coins, following the practice of the previous

The Hongwu Emperor believed that agriculture was the primary source of wealth and that there was a direct correlation between peasants and the state, which owned the land. He aimed to establish a patriarchal peasant monarchy, centered around the lives of the people living in peasant communes. The emperor firmly believed that if every man had a field and every woman had a loom, all hardships would disappear. However, this ideal was not reflected in reality as the wealthy held a disproportionate amount of land ownership and often found ways to evade paying taxes. In fact, during the final years of the Yuan dynasty, the land tax revenue dropped to zero.

The Hongwu Emperor attempted to transfer land into state ownership. During the wars that led to the establishment of the Ming state, there was a significant expansion of state ownership of land. This included land that had previously been owned by the state during the Yuan and Song empires, which was now returned to the government, as well as land that was confiscated from opponents of the new dynasty. In

The Hongwu Emperor believed that agriculture was the primary source of wealth and that there was a direct correlation between peasants and the state, which owned the land. He aimed to establish a patriarchal peasant monarchy, centered around the lives of the people living in peasant communes. The emperor firmly believed that if every man had a field and every woman had a loom, all hardships would disappear. However, this ideal was not reflected in reality as the wealthy held a disproportionate amount of land ownership and often found ways to evade paying taxes. In fact, during the final years of the Yuan dynasty, the land tax revenue dropped to zero.

The Hongwu Emperor attempted to transfer land into state ownership. During the wars that led to the establishment of the Ming state, there was a significant expansion of state ownership of land. This included land that had previously been owned by the state during the Yuan and Song empires, which was now returned to the government, as well as land that was confiscated from opponents of the new dynasty. In

For tax purposes, the population and their property, particularly land, were recorded in the Yellow Registers and Fish-Scale Map Registers. The Fish-Scale Map Registers documented land ownership, including size, quality, and owner, by village. The Yellow Registers, on the other hand, were based on household records, including household members (able-to-work men, women, and children) and their property, especially land. These registers were used to divide households into groups of one hundred and ten families in the ''lijia'' system and to determine tax obligations.

In the ''lijia'' system, the population was divided into groups of ideally 110 households, known as ''li''. Each ''li'' was further divided into ten ''jia'' groups, with ten households in each. The remaining ten wealthiest families took turns leading the hundreds after a year. Registered taxpayers were not allowed to move without approval from the authorities. Each year, one ''jia'' was responsible for providing services and supplies under the leadership of the ''li'' leader. After ten years, a census was recorded in the Yellow Registers, and households were redistributed into new ''li'' groups, beginning a new cycle.

Taxes were collected and lists of taxpayers were maintained by three ministries: Revennue, Works, and War. The Ministry of Revennue collected the land tax and kept records of peasants and their land plots. The Ministry of Works registered artisans and organized work duties, while the Ministry of War oversaw the military households and hereditary soldiers.

For tax purposes, the population and their property, particularly land, were recorded in the Yellow Registers and Fish-Scale Map Registers. The Fish-Scale Map Registers documented land ownership, including size, quality, and owner, by village. The Yellow Registers, on the other hand, were based on household records, including household members (able-to-work men, women, and children) and their property, especially land. These registers were used to divide households into groups of one hundred and ten families in the ''lijia'' system and to determine tax obligations.

In the ''lijia'' system, the population was divided into groups of ideally 110 households, known as ''li''. Each ''li'' was further divided into ten ''jia'' groups, with ten households in each. The remaining ten wealthiest families took turns leading the hundreds after a year. Registered taxpayers were not allowed to move without approval from the authorities. Each year, one ''jia'' was responsible for providing services and supplies under the leadership of the ''li'' leader. After ten years, a census was recorded in the Yellow Registers, and households were redistributed into new ''li'' groups, beginning a new cycle.

Taxes were collected and lists of taxpayers were maintained by three ministries: Revennue, Works, and War. The Ministry of Revennue collected the land tax and kept records of peasants and their land plots. The Ministry of Works registered artisans and organized work duties, while the Ministry of War oversaw the military households and hereditary soldiers.

Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming was the last imperial dynasty of ...

of China, in the 1360s–1390s were a comprehensive set of economic, social, and political changes aimed at rebuilding the Chinese state after years of conflict and disasters caused by the decline of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty ( ; zh, c=元朝, p=Yuáncháo), officially the Great Yuan (; Mongolian language, Mongolian: , , literally 'Great Yuan State'), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after Div ...

and the Chinese resistance against Mongol rule. These reforms resulted in the restoration of a centralized Chinese state, the growth of the Ming economy, and the emergence of a relatively egalitarian society with reduced wealth disparities.

The Hongwu Emperor

The Hongwu Emperor (21 October 1328– 24 June 1398), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Taizu of Ming, personal name Zhu Yuanzhang, courtesy name Guorui, was the List of emperors of the Ming dynasty, founding emperor of the Ming dyna ...

() attempted to create a self-sufficient society based on agriculture, with a stable system of relationships that would minimize commercial activity and trade in cities. The government's motto was "encouraging agriculture and restraining commerce" (; ''zhongnong yishang''). In this newly organized society, agriculture was the main source of wealth and the backbone of the economy, and the authorities provided support in every possible way. Two-thirds of the land was owned by the state, and it was divided among small peasants who directly cultivated the land. In contrast, large landowners were systematically restricted and persecuted. Industry and crafts were under state management, and trade was strictly supervised. The emperor showed concern for the common people and aimed to ensure a peaceful life for them, while also limiting the extravagances of the wealthy.

The emperor sought to exert control over all aspects of the country's life. The newly established Ming state administration was small and cost-effective. The government was led by the emperor's old comrades, who now served as generals in his army. Over time, they were gradually replaced by the emperor's sons. Routine administrative tasks were carried out by officials who had received a Confucian education. Taxation was primarily based on in-kind levies on agricultural and manufactured goods, as well as compulsory labor in state-owned factories and construction sites. The emperor's social ideal did not align with the use of money, so the government attempted to restrict its use. However, the lack of a suitable currency, such as copper or silver, and the unreliability of paper money, which could not be exchanged for precious metals and was prone to inflation, made it difficult to implement this policy.

In the long run, the rebuilding of China's agricultural base and the improvement of communication, along with the development of a military transport network, had an unintended consequence - the growth of markets along the restored roads and the spread of urban influences into rural areas. This led to the gentry, a class of Confucian-educated landowners who held official positions, being influenced by the emerging consumer culture. Over time, merchant families also began to integrate into the educated bureaucracy and adopt the customs of the gentry. This shift also brought about changes in social and political philosophies, administrative institutions, as well as in art and literature.

The emperor's social ideal

In the eyes of the Hongwu Emperor, the ultimate goal of government was political stability. All politics and the nature of institutions, including social and economic structures, were subordinated to this goal. The chaos and foreign rule that led to the establishment of the new Ming dynasty only further reinforced the importance of maintaining order. To achieve this goal, the emperor believed in creating a simple agricultural economy, with other sectors serving as complementary. His motto was one of frugality and simplicity. He firmly believed that if every man worked in his field and women also contributed, there would be no shortage and the overall quality of life for the people would improve. The Hongwu Emperor's public statements were filled with sympathy for the peasants and hostility towards the wealthy landowners and scholars. He referred to himself as a villager from the right bank of theHuai River

The Huai River, formerly romanized as the Hwai, is a major river in East China, about long with a drainage area of . It is located about midway between the Yellow River and Yangtze River, the two longest rivers and largest drainage basins ...

. Despite his position as emperor, he never forgot his difficult upbringing and maintained a strong belief in the ideal of a self-sufficient village life in peace, which was unattainable during his youth. As emperor, he made every effort to make this dream a reality for his subjects.

Despite his roots in the Manichaean

Manichaeism (; in ; ) is an endangered former major world religion currently only practiced in China around Cao'an,R. van den Broek, Wouter J. Hanegraaff ''Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times''. SUNY Press, 1998 p. 37 found ...

faith of the anti-Mongol insurgents, the Hongwu Emperor chose to adopt Confucianism as the state ideology and relied on Confucian scholars in the construction of the state apparatus. This emphasis on Confucianism led to a prioritization of moral considerations over economic ones in politics. Confucianism also provided justification for the government's stance against disproportionate wealth in the hands of a few. The extreme wealth inequality, which resulted in the political power and uncontrollability of the rich, was seen as a destabilizing force in society. Additionally, Confucian beliefs viewed wealth as a limited resource, and its concentration in the hands of the wealthy (or the state) would inevitably lead to the impoverishment of the people. As a result, the government saw it as their responsibility to prevent the growth of wealth disparities.

Under the banner of "humanity" ('' ren'', one of the central concepts of Confucianism), Chung-wu's government transformed society. The redistribution of property and wealth, particularly land, resulted in a more egalitarian society. This was a significant and far-reaching change, similar in depth and scope to the land revolution of the early communist People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

in the 1950s.

To effectively govern the Ming state, the government relied on the support of the social elite, including the gentry, educated officials, and landowners. In order to compensate for the loss of wealth they experienced under the previous Yuan dynasty, these elites were freed from labor obligations and services required by the ''lijia'' system, and instead only had to pay the land tax. The status of the educated elite was distinguished by their position in village assemblies and their inability to marry commoners. These measures helped to clearly define social groups and separate the bureaucratic class from the common people, beyond just wealth. The court also attempted to limit land ownership and discourage elites from accumulating large amounts of land. However, despite these efforts, the elites still sought to use their social status to gain wealth. As a result, a gradual concentration of land ownership was inevitable.

Government reforms

Central government

Upon ascending to the throne, the Hongwu Emperor appointed his wife as empress and his eldest sonZhu Biao

Zhu Biao (10 October 1355 17 May 1392) was the eldest son of the Hongwu Emperor, the founder of the Ming dynasty. Upon the establishment of the Ming dynasty in 1368, Zhu Biao was appointed as crown prince. In order to prepare for his future rei ...

as his heir. He surrounded himself with a group of military and civilian figures, but the civil officials never attained the same level of prestige and influence as the generals. In 1367, he named three of his closest collaborators as dukes (''gong'')—generals Xu Da

Xu Da (1332–1385), courtesy name Tiande, known by his title as Duke of Wei (魏國公), later posthumously as Prince of Zhongshan (中山王), was a Chinese military general and official who lived in the late Yuan dynasty and early Ming dynast ...

and Chang Yuchun

Chang Yuchun (常遇春, 1330 – 9 August 1369), courtesy name Boren (伯仁) and art name Yanheng (燕衡), was a Chinese military general of the Ming dynasty. He was a follower of Zhu Yuanzhang, the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty, and ...

, and official Li Shanchang

Li Shanchang (; 1314–1390) was a Chinese official of the Ming dynasty, part of the West Huai (Huaixi) faction, and Duke of Han, one of the six founding dukes of the Ming dynasty in 1370. Li Shanchang was one of Emperor Hongwu's associates duri ...

. After the establishment of the Ming dynasty, he granted ranks and titles to a wider circle of loyal generals. This military elite was chosen based on their abilities, but their titles and ranks were still hereditary. As a result, the generals became the dominant ruling class, surpassing the bureaucratic system. Officials had no political autonomy and were solely responsible for carrying out the emperor's orders and fulfilling his demands. In a sense, this arrangement mirrored that of the Yuan dynasty, with the ruling class of Mongols and Semu

Semu () is the name of a caste established by the Yuan dynasty. The 31 Semu categories referred to people who came from Central and West Asia. They had come to serve the Yuan dynasty by enfranchising under the dominant Mongol caste. The Semu wer ...

being replaced by families of distinguished military commanders who were connected through kinship ties with each other and with the imperial family.

The Ming administrative apparatus was initially modeled after the Yuan dynasty. The civil administration was led by the Central Secretariat (''Zhongshu Sheng

The Zhongshu Sheng (), also known as the Palace Secretariat or Central Secretariat, was one of the departments of the Three Departments and Six Ministries government structure in imperial China from the Cao Wei (220–266) until the early Ming d ...

''), which was headed by two Grand Councilors (''chengxiang''), who informally known as the prime ministers. The Central Secretariat oversaw six ministries: Personnel

Employment is a relationship between two parties regulating the provision of paid labour services. Usually based on a contract, one party, the employer, which might be a corporation, a not-for-profit organization, a co-operative, or any othe ...

, Revenue

In accounting, revenue is the total amount of income generated by the sale of product (business), goods and services related to the primary operations of a business.

Commercial revenue may also be referred to as sales or as turnover. Some compan ...

, Rites

RITES Ltd, formerly known as Rail India Technical and Economic Service Limited, is an Indian public sector undertaking and engineering consultancy corporation, specializing in the field of transport infrastructure. Established in 1974 by the In ...

, War

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organi ...

, Justice

In its broadest sense, justice is the idea that individuals should be treated fairly. According to the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', the most plausible candidate for a core definition comes from the ''Institutes (Justinian), Inst ...

, and (Public) Works. The Censorate controlled the administration, while the Chief Military Commission oversaw the army.

The emperor initially limited the number of eunuchs in the palace to 100 due to concerns about their influence. However, he later allowed their number to increase to 400, with the restriction that they were not allowed to learn to read, write, or interfere in politics.

The civil administration, which became the core of the government under later emperors, primarily served to secure finances and logistics for the army. Initially, the administration of the provinces was also under the control of the general, with the civil authorities also subject to them. However, in the 1370s, civilians began to be appointed to leadership positions in the provinces, weakening the military's influence. As a result, regional military commanders were left with the responsibility of managing the affairs of hereditary soldiers in the ''Weisuo'' system.

Centralization after 1380 and the replacement of generals by the emperor's sons

In 1380, Grand CouncilorHu Weiyong

Hu Weiyong (; died 1380) was a Chinese official of the early Ming dynasty and a close adviser of the Hongwu Emperor. In the second half of the 1370s, he headed the civil administration of the empire. However, in 1380, he was accused of treason an ...

was imprisoned and executed on suspicion of participating in a conspiracy against the emperor. As a result, his position (which was similar to that of a modern prime minister) and his entire office, the Central Secretariat, were abolished. The emperor also forbade its restoration permanently. The emperor then had direct control over six ministries. The censorship was temporarily suspended and the Chief Military Commission, which oversaw the armed forces, was divided into five Chief Military Commissions. Each commission was responsible for a portion of the troops in the capital and a fifth of the regions. Additionally, some of the regiments in the capital's garrison were under the direct control of the emperor. One of these regiments, known as the "Embroidered Uniform Guard

The Embroidered Uniform Guard () was the imperial secret police that served the emperors of the Ming dynasty in China. The guard was founded by the Hongwu Emperor, founding emperor of Ming, in 1368 to serve as his personal bodyguards. In 1369, ...

", acted as the secret police. After the reform, the emperor personally managed the central offices and served as the sole coordinator between departments. This resulted in a fragmentation of state authority and government, which prevented the possibility of a coup d'état but also weakened the government's long-term effectiveness.

The 1380 great purge was succeeded by subsequent trials, targeting not only several ministers and deputy ministers, but also hundreds of less prominent individuals. These executions incited a series of protests from officials, who argued that the state apparatus was being demoralized and valuable human resources were being wasted. While the emperor did not punish these critics, he also did not alter his policies.

The emperor was fearful of the conspiracy of the generals and as a result, he gradually executed a number of them, particularly in connection with the cases of Hu Weiyong and Lan Yu. This fear was not unfounded, as the risk of a conspiracy by the generals was always present. The emperor himself had come to power through the betrayal of the heirs of Guo Zixing

Guo Zixing (; d. 1355) was a rebel leader in the late Yuan dynasty of China. He was the father-in-law of Zhu Yuanzhang, the future founder of the Ming dynasty.

Life

Guo Zixing originally came from Dingyuan. His father was a fortune teller an ...

and had also faced conspiracies from his subordinates. In the early 1380s, he began to replace deserving generals with his own sons, granting them titles of princes (''wang'') and military command in various regions. Once they reached the age of twenty, they were sent to their designated regions, with the first being in 1378. As they settled into their roles, their importance and influence grew. The most significant of the emperor's sons were Zhu Shuang, Zhu Gang, and Zhu Di, who were based in Xi'an

Xi'an is the list of capitals in China, capital of the Chinese province of Shaanxi. A sub-provincial city on the Guanzhong plain, the city is the third-most populous city in Western China after Chongqing and Chengdu, as well as the most populou ...

, Taiyuan

Taiyuan; Mandarin pronunciation: (Jin Chinese, Taiyuan Jin: /tʰai˦˥ ye˩˩/) is the capital of Shanxi, China. Taiyuan is the political, economic, cultural and international exchange center of Shanxi Province. It is an industrial base foc ...

, and Beijing

Beijing, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's List of national capitals by population, most populous national capital city as well as ...

, respectively, and commanded the armies on the northern frontier. Apart from the princes, other members of the imperial family were excluded from the administration of the country.

Officials

The state administration was organized according to Confucian principles, with officials being primarily recruited through recommendations. Initially, these recommendations were made by special commissioners at the establishment of the empire in 1368, and later by local officials. The Ministry of Personnel, or possibly the emperor, evaluated the recommended individuals and appointed them to their positions. Another important source of officials was the revived Imperial University, which oversaw a vast network of Confucian schools throughout the empire, established inprefectures

A prefecture (from the Latin word, "''praefectura"'') is an administrative jurisdiction traditionally governed by an appointed prefect. This can be a regional or local government subdivision in various countries, or a subdivision in certain inter ...

, provinces

A province is an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman , which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions outside Italy. The term ''provi ...

, and counties. In February 1371, the emperor made the decision to renew official examinations and hold provincial and county examinations every three years, with the provincial examinations taking place in March. However, by 1373, the civil service examinations were cancelled due to dissatisfaction with the quality of the graduates. The emperor believed that instead of capable administrators, impractical bookworms were succeeding in the examinations. The examinations were reinstated in 1384 and continued in three-year cycles until the end of the dynasty.

Every three years, provincial examinations were held, and those who passed were awarded the title of ''juren

''Juren'' (; 'recommended man') was a rank achieved by people who passed the ''xiangshi'' () exam in the imperial examination system of imperial China. The ''xiangshi'' is also known, in English, as the provincial examination. It was a rank high ...

''. This title was sufficient for starting an official career in the early Ming period, and also qualified individuals for teaching positions in local schools until the end of the dynasty. Following the provincial examinations, metropolitan examinations were held. Upon passing, candidates advanced to the palace examinations, where their work was read by the emperor himself. Successful candidates were awarded the rank of ''jinshi

''Jinshi'' () was the highest and final degree in the imperial examination in Imperial China. The examination was usually taken in the imperial capital in the palace, and was also called the Metropolitan Exam. Recipients are sometimes referre ...

'', with a total of 871 individuals granted it during the Hongwu period.

There were fewer than 8,000 civil servants, with half of them in lower grades (eighth and ninth), not including the approximately 5,000 teachers in government schools. Unlike in later years, during the early Ming period, there were not enough candidates obtained through examinations, and positions were often filled based on recommendations and personal connections. The bureaucratic system was still in its early stages, and the introduction of examinations primarily had symbolic significance as a declaration of allegiance to Confucianism.

Despite the emperor's support for Confucianism, he harbored a deep distrust for officials and was quick to severely punish them for any wrongdoing. For example, in 1397, when it was discovered that only candidates from the more populous and educated southern region were passing the palace examinations, he accused the examiners of favoring the southerners and exiled them, possibly even sentencing them to death.

Confucian-educated officials were limited to managerial positions within the state administration. The day-to-day administrative tasks and paperwork were left to lower-ranking employees and helpers, who were typically recruited from the local population. In fact, there were four times as many of these employees as there were officials.

As a result of the emperor's efforts to save money, the salaries of officials and the incomes of members of the imperial family were reduced to approximately one-fifth of what they were under previous dynasties. Additionally, officials were often paid in debased paper money or forced to accept non-essential items such as paintings, calligraphy

Calligraphy () is a visual art related to writing. It is the design and execution of lettering with a pen, ink brush, or other writing instruments. Contemporary calligraphic practice can be defined as "the art of giving form to signs in an e ...

, and pepper instead of necessary items like rice, cloth, cash, and precious metals. Furthermore, officials and officers, as well as their families and relatives, were prohibited from engaging in trade or lending money. This created a significant challenge for those at the lower levels of the hierarchy, as they were often unable to support themselves without the financial assistance of their more affluent relatives.

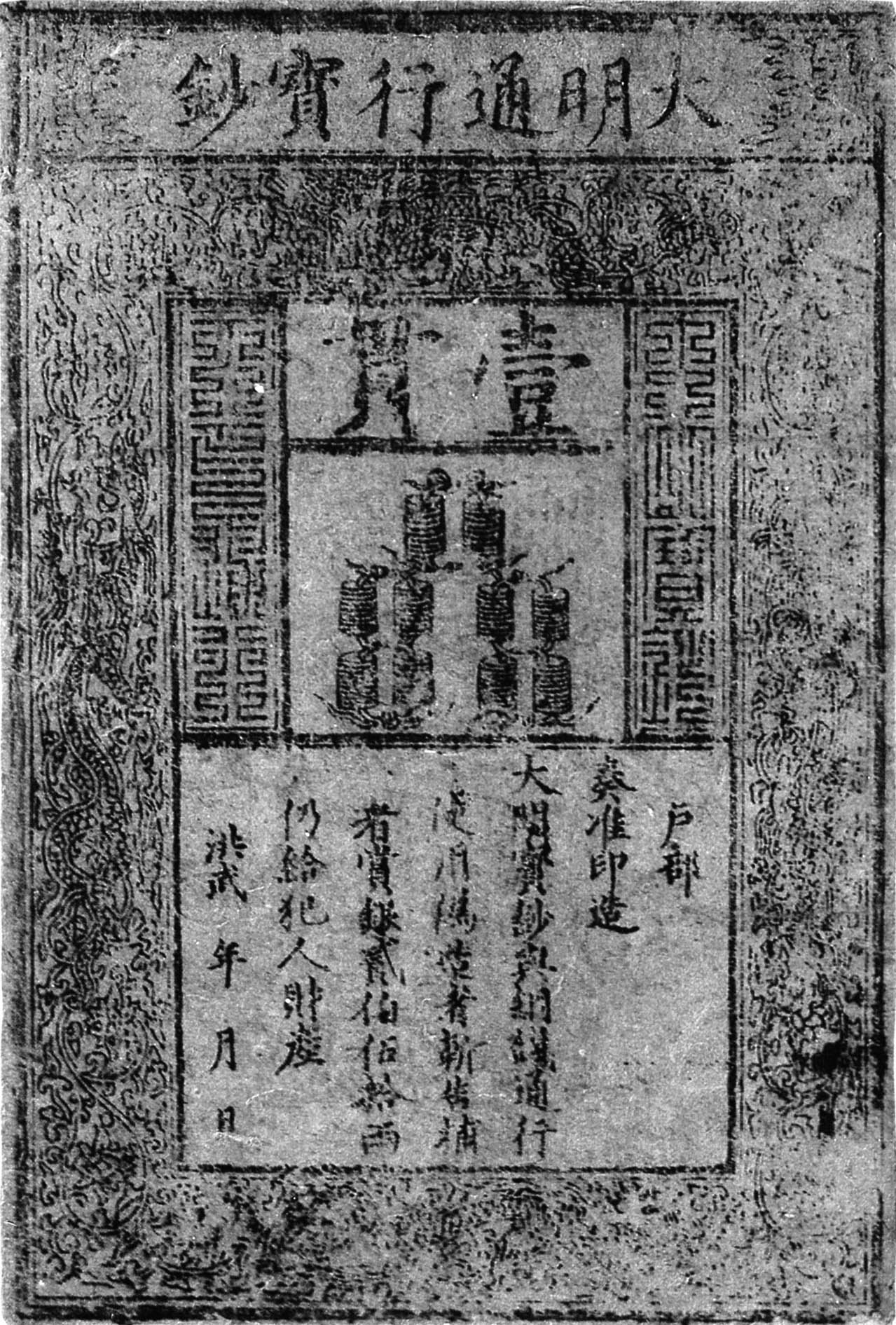

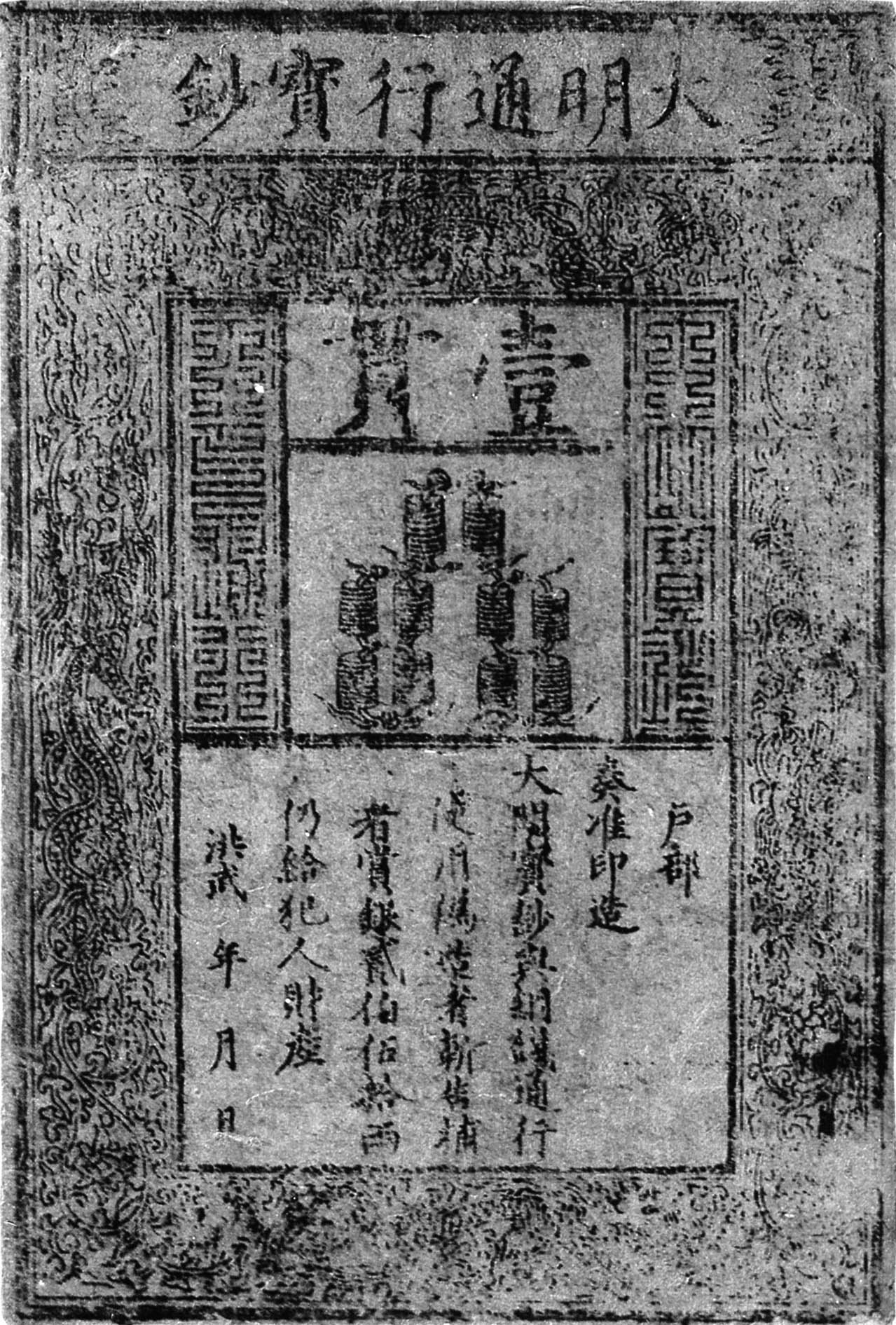

Currency

Inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the average price of goods and services in terms of money. This increase is measured using a price index, typically a consumer price index (CPI). When the general price level rises, each unit of curre ...

at the end of the Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty ( ; zh, c=元朝, p=Yuáncháo), officially the Great Yuan (; Mongolian language, Mongolian: , , literally 'Great Yuan State'), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after Div ...

led to the abandonment of paper money in favor of grain as the primary medium of exchange. Copper (effectively bronze) coins were also used during this time. In 1361, the Hongwu Emperor began producing his own coins, known as Dazhong Tongbao, in five different denominations: 1 ''wen'', 2, 3, 5, and 10 multiples. However, this small emission did not have a significant economic impact and was mainly a symbol of political independence for his department. The opening of mints in conquered territories was seen as a sign of complete subjugation. In the 1360s, the Hongwu Emperor's government did not have much control over the economy and allowed old coins to continue circulating while leaving pricing decisions to the market.

The production of coins in Ming China was not as significant as it had been in previous dynasties due to their limited use. In the early Ming period, coins were mainly circulated in the southern and southeastern regions of the country, where state coins from the Mongol era were still in use. It was not until the second quarter of the 15th century that coins began to be used in the northwest.

In an attempt to combat the inflation that occurred during the late Yuan dynasty, the Hongwu Emperor attempted to reintroduce the use of copper coins, following the practice of the previous

In an attempt to combat the inflation that occurred during the late Yuan dynasty, the Hongwu Emperor attempted to reintroduce the use of copper coins, following the practice of the previous Song dynasty

The Song dynasty ( ) was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 960 to 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song, who usurped the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty and went on to conquer the rest of the Fiv ...

. In 1368, when the Ming dynasty was established, coins were once again produced, known as the Hongwu Tongbao, in denominations of 1, 2, 3, 5, and 10 ''wen''. However, larger value coins were not accepted by the market and were discontinued in 1371. Even the more common one-won coins faced difficulties in circulation due to their limited quantity, as reported by officials. This was due to the depletion of copper mines in the southern provinces of Guangdong

) means "wide" or "vast", and has been associated with the region since the creation of Guang Prefecture in AD 226. The name "''Guang''" ultimately came from Guangxin ( zh, labels=no, first=t, t= , s=广信), an outpost established in Han dynasty ...

and Guangxi

Guangxi,; officially the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People's Republic of China, located in South China and bordering Vietnam (Hà Giang Province, Hà Giang, Cao Bằn ...

, which had provided 95% of China's copper production during the Song dynasty. Despite efforts to increase production by melting down old products, the annual production of copper coins could not exceed 160 million, which was less than three coins per person. Officials suggested reducing the copper content of the coins by 10% to increase their quantity, but the emperor rejected this proposal, refusing to devalue the currency.

An alternative to copper could not be gold, which was rare and, due to its high value, unsuitable for everyday use. Additionally, silver was even rarer than copper. For example, in 1391, the state treasury only contained 24,740 ''liang'' (923 kg) of silver, which was a mere quarter of the Chinese wholesaler's wealth two centuries later. Given these circumstances, the Hongwu Emperor's government had no other option but to turn to paper money in 1375. These state bills, known as '' Da Ming Baochao'', were intended to serve as the primary means of exchange, with copper coins playing a secondary role. The initial exchange rate was set at 1 ''liang'' (37.3 g) of silver = 1 '' dan'' (107.4 liters) of grain = 1 ''guan'' of state banknote. (''guan'' was a monetary unit equal to 400 coppers.)

In 1375, the use of silver and gold in trade was prohibited, coinciding with the introduction of state banknotes. However, unlike the Song and Yuan periods, paper money was not exchangeable for precious metals, leading to a lack of trust in its value among the population. The government attempted to support the use of paper money by manipulating the money supply, but their efforts were inconsistent, with periods of stopping printing and minting followed by periods of printing at full capacity. The mints were closed in 1375–1377 and again in 1387–1389, while the printing of money was interrupted in 1384–1389 and stopped completely in 1391. However, when the government did print money, it was in excessive amounts. For example, in 1390, the government's income was 20 million ''guan'', but their expenses were officially reported as 95 million, and likely even higher in reality.

The consequences were not long in coming. By 1394, the price of state banknotes had fallen to 40% of its face value. As a result, merchants turned to silver as the best option, as paper money suffered from depreciation, copper was of little value, and gold was scarce. In response, the government attempted to withdraw copper coins by ordering their mandatory exchange for state banknotes in 1394. They also banned the use of silver in trade in 1397. To further discourage the circulation of silver and copper coins, the government allowed some taxes to be paid with them. The ban on private foreign trade was also motivated by the desire to defend against the import of silver. Additionally, the circulation of silver was seen as a threat to the established economic order. Ideally, people should have obtained everything they needed in exchange for grain grown for them, or through subsistence, without the use of silver.

However, due to the lack of precious metals, merchants determined prices in silver but were paid in paper money at a gradually decreasing exchange rate. This resulted in silver and gold becoming the measure of value, with banknotes serving as the means of payment.

The anti-silver policy can be interpreted as an effort to break the power of the wealthy in Jiangnan, who were formerly supporters of the Hongwu Emperor's rival, Zhang Shicheng

Zhang Shicheng (; 1321-1367), born Zhang Jiusi (), was one of the leaders of the Red Turban Rebellion in the late Yuan dynasty of China.

Early life

Zhang Shicheng came from a family of salt shippers, and he himself started out in this trade i ...

. In the emperor's opinion, silver gave its owners undue freedom, making the rejection of the exchangeability of banknotes for silver understandable.

Land reform

Jiangsu

Jiangsu is a coastal Provinces of the People's Republic of China, province in East China. It is one of the leading provinces in finance, education, technology, and tourism, with its capital in Nanjing. Jiangsu is the List of Chinese administra ...

and Zhejiang

)

, translit_lang1_type2 =

, translit_lang1_info2 = ( Hangzhounese) ( Ningbonese) (Wenzhounese)

, image_skyline = 玉甑峰全貌 - panoramio.jpg

, image_caption = View of the Yandang Mountains

, image_map = Zhejiang i ...

, regions that had supported the Hongwu Emperor's enemies during the wars, all private land was seized and former landowners were forced to relocate to the north. After becoming emperor, the Hongwu Emperor resettled 14,300 wealthy families from Zhejiang and the Nanjing hinterland from their estates to Nanjing. The vast properties of Buddhist monasteries, which had owned three-fifths of the land in Shandong province

Shandong is a coastal province in East China. Shandong has played a major role in Chinese history since the beginning of Chinese civilization along the lower reaches of the Yellow River. It has served as a pivotal cultural and religious center ...

during the Yuan dynasty, were also confiscated. Additionally, 3,000 Buddhist and Taoist monasteries were abolished, 214,000 Buddhist and 300,000 Taoist monks and nuns were returned to secular life, and monasteries were reduced to one with a maximum of two monks in each county. School grounds and land designated for the provision of officials were also under state ownership. Overall, the state owned two-thirds of cultivated land, with private land being more prevalent in the south and the majority of land in the north being state-owned.

Even the new Ming officials were not exempt from targeting large landowners. In 1380, the ownership of lands acquired by ministers and officials was revised, and in 1381, the same was done for holders of aristocratic titles, including members of the imperial family. They were required to return the acquired land to the state and were compensated with rice and silk.

Most of the state lands were then redistributed to peasants for permanent use. In the northern regions, peasants were given 15 ''mu'' (0.87 ha) per field and two (1,160 m²) per garden, while in the south, they received an allotment of 16 ''mu'' (0.87 ha) for peasants and 50 ''mu'' (2.9 ha) for hereditary soldiers. Those who had abandoned their properties during the wars were not entitled to reclaim them, but were instead given replacement plots, on the condition that they personally worked on them. Those who occupied larger plots than they were able to cultivate were punished with flogging and had their land confiscated. While Emperor Taizu of Song

Emperor Taizu of Song (21 March 927 – 14 November 976), personal name Zhao Kuangyin, courtesy name Yuanlang, was the founding emperor of the Song dynasty of China. He reigned from 960 until his death in 976. Formerly a distinguished milita ...

() had encouraged the growth of large landowners, the Hongwu Emperor aimed to eliminate them. As a result of his reforms, large landowners virtually disappeared.

Peasants who farmed on state land were allowed to pass it down to their descendants, but were not permitted to sell it and move elsewhere. The Tang system of equal fields was theoretically reinstated, but there was no standardized allocation of land that took into account local conditions and family size. As a result of these reforms, small independent farmers became the dominant figure in the Chinese countryside. The laws required every able-bodied peasant to work in the fields and empowered village elders to punish those who were idle.

Regulation of consumption

The consumption of the wealthy and privileged was also restricted, as it was feared that displays of wealth and extravagant spending would harm social cohesion and undermine the state's social and economic foundations. The privileged were expected to practice self-restraint, which was justified by Confucian morality. Materialistic interests and selfishness were frowned upon, and the Hongwu Emperor set an example by living a simple lifestyle and avoiding luxurious food and furnishings. He believed that seeking comfort, luxury, and property was a selfish act and a sign of corruption. He even went as far as to order his sons to plant vegetable gardens instead of flower gardens in their palaces, and banned the keeping of pet animals like tigers, encouraging the use of useful animals like cows instead. He also prohibited the cultivation of rice varieties used for making rice wine. In contrast to the attitude towards the wealthy, care for the poor greatly increased during this time period. The government took responsibility for the maintenance of widows, orphans, the childless elderly, the sick, and those who were unable to support themselves. In each county, the government ordered the establishment of shelters for the needy. Additionally, the poor who were living independently were guaranteed 3 ''dou'' (approximately 32 liters) of rice, 30 ''jin'' (approximately 18 kg) of wood, and a bundle of cloth. Those who were 80 years of age or older were given 5 ''dou'' of rice, 5 ''jin'' of meat, and 3 ''jin'' of wine. These costs were covered by the wealthy families in the community through the ''lijia'' system, with the threat of property confiscation for those who did not comply. The emperor attempted to strictly regulate not only consumption, but also the entire lives of his subjects. This included enforcing standards for greetings and the style of written texts, as well as restricting the naming of individuals and prohibiting the use of symbols that reminded him of a monastic episode in his own life. The acceptable quality of food, clothing, housing, and transportation was determined for each social class. For example, commoners were limited to three rooms in their homes and were not permitted to travel by wagon or horse. Only county authorities were allowed to use donkeys. Soldiers were punished for engaging in music and games. As a result, the wealthy concealed their wealth, leading to a decrease in demand for luxury goods and a decline in commercial activity.Support for agricultural production

In an effort to restore the prosperity of a country devastated by long-term wars, the government implemented various measures to support agricultural production. These measures included limiting slavery (only members of the imperial family were allowed to own slaves), reducing the number of monks, prohibiting the buying and selling of free people, and banning the acceptance of women, children, and concubines as pledges. The slave trade was also prohibited. Additionally, the government organized resettlement from the populated south to the devastated northern provinces. Initially, this was done involuntarily, but later the government abandoned forced relocation. Hundreds of thousands of people were resettled, and in addition to land, they were provided with sowing equipment and draft animals. Soldier-peasant villages were also established in borderlands and strategically important areas. These villagers were obligated to provide military service in times of war and supply the army with food during times of peace. In addition to reclaiming abandoned land, efforts were made to repair and improve irrigation systems. The Hongwu Emperor instructed local authorities to report any requests or feedback from the people regarding the maintenance or construction of irrigation structures. In 1394, he issued a special decree for the Ministry of Works to ensure that canals and dams were properly maintained in case of drought or heavy rains. He also dispatched graduates from state schools and technical specialists to oversee flood protection structures throughout the country. By the winter of 1395, a total of 40,987 dikes and drainage canals had been constructed across the nation.Local government and taxation

Organization of local self-government

The villages formed self-governing communities, resolving their internal disputes without the intervention of officials. This was in line with the Hongwu Emperor's recommendation to keep officials out of the countryside. These communities operated based on Confucian morality rather than laws.Principles of taxation

Due to a shortage of copper and silver bullion, the Ming inherited an economy without a practical currency. Compared to the Song system of taxation, which was based on a dual system of copper coins and state banknotes, and the Yuan system, which was completely based on state banknotes, the Ming system relied on levies in kind. This meant that state revenues consisted of taxes in grain, materials, and compulsory labor, with money playing a minimal role. Taxpayers were also responsible for transporting their in-kind contributions to state warehouses and granaries. For example, the capital required 4 million ''dan'' of grain, which was provided by taxpayers from Jiangnan, while 8 million ''dan'' of grain were supplied by taxpayers from the north to the northern border. Additionally, state projects and actions were carried out by the population through labor obligations. Tax revenues were directly allocated and delivered to the authorities and organizations that consumed them. This meant that there were no central warehouses or budgets, but rather a multitude of accounts and receipts. Any non-routine expenditure required the approval of the emperor, and it was also determined from which income it would be paid. As state income and expenditure were fulfilled through orders to the population to deliver the desired goods to a designated location, there was no need for large warehouses. However, officials were not always able to direct supplies to the necessary places, resulting in a number of local supply crises. The state did not participate in the market—whatever was needed was produced in state manufactories, possibly obtained through levies from the population. Therefore, the state did not have a significant need for money, and even officials were paid in rice. However, running an economy without money was expensive. For every ''dan'' of grain transported to the capital, taxpayers had to spend 2–3 ''dan'' on transport costs when the soldiers provided the transport (known as the ''caoyun'' system, ), and 4 ''dan'' when the taxpayers provided the transport themselves (known as the ''minyun'' system, ). Transport to warehouses on the northern border was even more costly, at 6–7 ''dan''. Additionally, the soldiers were stationed more than 500 km from these warehouses and had to bring their own supplies to their garrisons. Furthermore, grain sometimes spoiled in large warehouses. The artisans' work obligation was quite burdensome, as it required them to work for three months in the capital at their own expense. This situation was disadvantageous for not only the taxpayers, but also for the state and officials. In order to obtain necessary items for their livelihood, officials were forced to sell part of their pay in kind, resulting in a loss. Due to the pressure to introduce a monetary system, the government had no option but to use banknotes, as there was a shortage of both copper and silver.Peasants

From the beginning of the dynasty, the land tax was seen as a means of providing food for civil servants, officials, soldiers, and laborers working on public projects. Any excess food was stored by the government as a reserve in case of natural disasters. Regional tax captains (''liangzhang''), who were chosen by county authorities from wealthy families, were responsible for collecting taxes. In 1371, the lijia system of local self-government was established in the Yangtze River Basin and gradually expanded throughout the empire. All regular state expenses, except for the land tax, were covered by compulsory services and supplies from the population, organized into ''lijia'' groups. Unlike the land tax, this form of taxation was progressive. Large infrastructure projects, such as the construction of roads, dams, and canals, were funded through additional ''ad hoc

''Ad hoc'' is a List of Latin phrases, Latin phrase meaning literally for this. In English language, English, it typically signifies a solution designed for a specific purpose, problem, or task rather than a Generalization, generalized solution ...

'' requisitions. In 1382, the responsibility for tax collection was transferred to the ''li'', resulting in the abolition of regional tax captains. However, they were reinstated three years later and were now responsible for collecting taxes from the heads of the ''li''. They would then transport the taxes to state granaries, with the expenses for transport, accountants, and supervision being covered by the ''li''.

The land tax underwent a significant reduction upon the establishment of the Ming dynasty. Peasants were required to pay 0.53 ''dou'' per ''mu'' (equivalent to 5.7 liters from 580.32 m³) on state-owned land, and 0.33 ''dou'' per ''mu'' on private land. However, in Jiangnan

Jiangnan is a geographic area in China referring to lands immediately to the south of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, including the southern part of its delta. The region encompasses the city of Shanghai, the southern part of Jiangsu ...

, the tax was based on leasehold and amounted to over 1.3 ''dou'' per ''mu''. This resulted in the five Jiangnan prefectures (Suzhou

Suzhou is a major prefecture-level city in southern Jiangsu province, China. As part of the Yangtze Delta megalopolis, it is a major economic center and focal point of trade and commerce.

Founded in 514 BC, Suzhou rapidly grew in size by the ...

, Zhangzhou

Zhangzhou (, ) is a prefecture-level city in Fujian Province, China. The prefecture around the city proper comprises the southeast corner of the province, facing the Taiwan Strait and (with Quanzhou) surrounding the prefecture of Xiamen.

Nam ...

, Songjiang Songjiang, from the Chinese for "Pine River" and formerly romanized as Sungkiang, usually refers to one of the following areas within the municipal limits of Shanghai:

* Songjiang, Shanghai, a present suburban district of Shanghai

* Songjiang Pre ...

, Jiaxing

Jiaxing (), alternately romanized as Kashing, is a prefecture-level city in northern Zhejiang province, China. Lying on the Grand Canal of China, Jiaxing borders Hangzhou to the southwest, Huzhou to the west, Shanghai to the northeast, and the p ...

, and Zhenjiang

Zhenjiang, alternately romanized as Chinkiang, is a prefecture-level city in Jiangsu Province, China. It lies on the southern bank of the Yangtze River near its intersection with the Grand Canal. It is opposite Yangzhou (to its north) and ...

) contributing a quarter of the empire's total taxes. Additionally, peasants were obligated to work on state constructions, with one person required to work for 1 month for every 100 ''mu'' of land.

Furthermore, the emperor created a list of large landowners, specifically families with more than 700 ''mu'' (approximately 40 hectares) of land. These 14,341 families were subjected to additional duties and their sons were called upon to serve in the civil service.

Artisans

While the Ministry of Revennue collected taxes and benefits from peasants, the Ministry of Works handled the taxation of artisans. In the cities, artisans were easily accessible to officials who enforced their obligations to the state. They were also required to register and could not move without the knowledge of the authorities. In addition to paying taxes, artisans were also obligated to perform work, which could be extremely burdensome if it had to be done outside of their residence. State-owned manufactories were responsible for producing all necessary goods for the functioning of the state, whether it be for the imperial palace or the army. The state held a monopoly on the mining and processing of ores, resulting in high prices for metals. Porcelain production was also under state control. As the cost of materials was the main factor in determining the price of products, and the state-owned factories had no material costs, the private sector was unable to compete. Artisans in state manufactories were required to work for free as part of their labor obligation, for a period of three months every 2 to 5 years, depending on their profession. Additionally, there were 234,000 paid craftsmen in 62 different branches. The state also tightly regulated the production and distribution of salt and tea, imposing high levies on producers and prohibiting unregistered production.Hereditary soldiers

Self-sufficiency was a key aspect of the state's operations, with the army alone consuming nearly half of its income. The emperor's goal was to make the army independent from the market and able to "supply a million soldiers without the government having to provide a single grain of rice". In 1373, demobilized soldiers were given 50 ''mu'' (2.9 ha) of land, a cow, and seed, with the condition that 70% of them would engage in agriculture in the borderlands and 80% in the interior. Soldiers were under hereditary obligation to serve, with each family required to provide one member for military service in each generation. The Ministry of War maintained lists of these hereditary soldiers and collected benefits and taxes from them. Additionally, a tenth of the state's agricultural land was designated for their use. The purpose of their farming was to provide food for the army. If the government needed raw materials for the navy or army, it could simply order the hereditary soldiers to grow them.Trade and travel

The emperor's distrust of the official elite was accompanied by a disdainful attitude towards merchants. He viewed weakening the influence of the merchant and landowner class as a top priority for his government. As part of this effort, he implemented high taxes in and around Suzhou, which was the main commercial and economic hub of China at the time. Additionally, thousands of wealthy families in the area were forced to relocate to Nanjing and the southern bank of the Yangtze River. To prevent unauthorized business activities, traveling merchants were required to report their names and cargo to local agents and undergo monthly inspections by the authorities. They were also obligated to store their goods in government warehouses. Merchants were greatly affected by the restrictions on population mobility during this time. Any journeys longer than 58 km (100 ''li'') were strictly prohibited unless one had official permission. This travel document included important information such as the individual's name, place of residence, the name of their home municipality's administrator, age, height, physical description, occupation, and names of family members. Any irregularities found in the document could result in the individual being sent back home and facing punishment. Passengers were subjected to thorough checks by soldiers at various checkpoints, including roads, ferries, and streets. Inns were required to report their guests to the authorities, providing information on their travel destinations and any goods they were transporting. Merchants were also required to store their goods in state warehouses and could not engage in trade without a license. The authorities would then inspect the goods, destination, and prices to ensure compliance. The use of intermediaries, or brokers, was strictly prohibited. The government also set fixed prices for most goods, and failure to comply with these prices resulted in punishment. In addition, merchants risked having their goods confiscated and being subjected to flogging for selling poor quality products. Few governments took the concept of four classes (in descending order: officials, peasants, artisans, merchants) as seriously and consistently as the Ming government did. The low status of merchants was evident in various ways, such as clothing regulations that prohibited them from wearing furs, along with servants and prostitutes. Merchants were also not allowed to wear silk. They were even excluded from civil service examinations, unlike peasants. For example, out of the 110 ''jinshi'' graduates in 1400, 83 came from farming families, 16 from military families, 6 were scholars, but none were from merchant families. This discrimination against merchants persisted for centuries, as seen in the fact that none of the 312 new ''jinshi'' graduates in 1544 came from a merchant family. Despite the government's efforts, the interest in trade among residents did not diminish. Contemporary authors attributed this to the profitability of trade, as a single successful trade route could yield more profit than a year's worth of work in the fields.Foreign relations

Before conquering foreign countries, the Hongwu Emperor prioritized stabilizing the government in China. This is evident in his refusal to involve himself in the war betweenChampa

Champa (Cham language, Cham: ꨌꩌꨛꨩ, چمڤا; ; 占城 or 占婆) was a collection of independent Chams, Cham Polity, polities that extended across the coast of what is present-day Central Vietnam, central and southern Vietnam from ...

and Đại Việt

Đại Việt (, ; literally Great Việt), was a Vietnamese monarchy in eastern Mainland Southeast Asia from the 10th century AD to the early 19th century, centered around the region of present-day Hanoi. Its early name, Đại Cồ Việt,(ch ...

(present-day northern Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

), as well as internal conflicts in Japan, except through verbal means. Following defeats in Mongolia in 1372, he cautioned future emperors against seeking glory through conquest and advised them to focus on defending China against "northern barbarians". A year prior, he had already taken steps to strengthen the country's defense by abolishing prefectures and districts and resettling 70,000 families from northern regions beyond the later Great Wall of China

The Great Wall of China (, literally "ten thousand ''li'' long wall") is a series of fortifications in China. They were built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China as protection against vario ...

(which was gradually built by the Hongwu Emprror's successors from the mid-15th century) to the interior, particularly in Beijing and its surrounding areas.

Initially, the emperor supported foreign trade as a means of generating revenue. However, his tendency to control the economy and society led to strained relations with foreign countries. The government viewed trade as a destructive force and private foreign trade was not allowed. As a result, after 1368, the emperor restricted contact with foreign countries and limited trade to official diplomatic missions. These missions served to demonstrate the Ming government's legitimacy and superiority, with surrounding countries paying tribute in recognition. In return, the foreign delegations received Chinese goods equivalent to the tribute. This was a way for the Ming government to maintain control over foreign trade. The main reason for restricting contact with foreign countries was to ensure the security of the state, but there was also a fear of precious metals leaving the country.

The Hongwu Emperor's policy of strict control over overseas foreign relations and trade was known as ''Haijin

The Haijin () or sea ban were a series of related policies in China restricting private maritime trading during much of the Ming dynasty and early Qing dynasty. The sea ban was an anomaly in Chinese history as such restrictions were unknown durin ...

''. This policy aimed to prevent Chinese citizens from leaving the empire, foreigners from entering, and trading with them was punishable by death for the offender and exile for their family. In addition, the government prohibited the construction of ships with two or more masts and destroyed existing ones. Harbors were filled with stones and logs, and foreign goods were destroyed. The coast was heavily guarded. The emperor's goal was to ensure that "not even a piece of wood may float on the sea". However, the lucrative nature of overseas trade made it difficult for merchants to give up, leading to the rise of smuggling. The government responded with strict border control and punishment, but this did not effectively solve the issue.

Aftermath

The Hongwu Emperor's policies had a lasting impact on the country, with some elements being abandoned relatively quickly while others persisted until the end of the empire in the mid-17th century. The simple natural economy that was established during the reforms eventually began to deteriorate within a few decades. This was due to a number of factors, such as the challenge to Confucian values, the concentration of land ownership, the decline in efficiency of state industries, the disadvantages of self-sufficiency, and the violence caused by the suppression of foreign trade. Initially, these decisions may not have seemed expensive, but over time, they became a heavy burden on the state treasury. During the Hongwu era, the small number of imperial family members andForbidden City

The Forbidden City () is the Chinese Empire, imperial Chinese palace, palace complex in the center of the Imperial City, Beijing, Imperial City in Beijing, China. It was the residence of 24 Ming dynasty, Ming and Qing dynasty, Qing dynasty L ...

staff did not pose a problem. However, as the number of the emperor's relatives and palace eunuchs grew into the tens of thousands, there was a constant lack of funds to ensure their security. Similarly, in the 15th century, a small number of tax exemptions and immunities gradually increased to the point where half of the land was no longer subject to taxation.

The organization of the government underwent significant changes during the Hongwu era. Within a year of the emperor's death, a civil war known as the Jingnan campaign

The Jingnan campaign, or the campaign to clear away disorders, was a three-year civil war from 1399 to 1402 in the early years of the Ming dynasty of China between the Jianwen Emperor and his uncle, Zhu Di, Prince of Yan. The war was sparked by ...

erupted. This conflict resulted in the overthrow of the Hongwu Emperor's grandson and successor, the Jianwen Emperor

The Jianwen Emperor (5 December 1377 – probably 13 July 1402), personal name Zhu Yunwen, also known by his temple name as the Emperor Huizong of Ming and by his posthumous name as the Emperor Hui of Ming, was the second emperor of the Ming d ...

(), by his fourth son, the Yongle Emperor

The Yongle Emperor (2 May 1360 – 12 August 1424), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Chengzu of Ming, personal name Zhu Di, was the third List of emperors of the Ming dynasty, emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1402 to 142 ...

(). The Yongle Emperor's reign saw a decrease in the influence of the emperor's relatives and an increase in the power of officials, particularly grand secretaries and palace eunuchs. The country was now governed by Confucian-educated officials who had passed civil service examinations. However, the absence of a position similar to the grand councilor

The grand chancellor (, among other titles), also translated as counselor-in-chief, chancellor, chief councillor, chief minister, imperial chancellor, lieutenant chancellor and prime minister, was the highest-ranking executive official in the i ...

(after the abolition of the Central Secretariat in 1380) weakened the authority of top officials in relation to the emperors. This weakness was evident in the severe punishments inflicted on dissenting officials, such as public floggings and executions. Without strong and decisive emperors at the helm, the style of government under the Hongwu and Yongle emperors remained an ideal, with officials seeking only formal approval from the emperors or moderating ministerial discussions. Meanwhile, the emperors were unable to assert their will against the conservative bureaucratic administrations and instead relied on loyal and obedient eunuchs in the palace. A functional and efficient government was only possible with the difficult cooperation of officials, grand secretaries, and eunuchs favored by the emperor.

In the early 15th century, the productivity of soldier-peasant communities declined, and their levies dropped to one-tenth. Armies of hereditary soldiers largely lost their combat effectiveness and were gradually replaced by paid mercenaries. Instead of being led by hereditary generals, armies were now commanded by military officials and eunuchs.

The system of small land ownership, which had been politically promoted, did not last. By the Jiajing era (1522–1567), the situation had come full circle—from the high concentration of land ownership under the Yuan dynasty, to the predominance of small land ownership in the early Ming, and finally to the gradual resurgence of large estates in the late Ming. This shift in land ownership also had a significant impact on state administration, as small peasants were the dominant form of ownership and the land tax was the main source of state revenue in the early Ming (and in the early modern economy in general). Therefore, agricultural policy played a critical role in all aspects of state administration. The natural economy gradually transitioned to a monetary one, with silver replacing the failed paper money. From the 1430s, taxes were paid in silver. The process of switching to silver accelerated in the 1520s with the Single Whip reform, but was not completed before the collapse of the empire in the mid-17th century.

With the growth of the economy, the use of money became more extensive and individual owners and entire regions became more specialized. This led to the development of nationwide long-distance trade and a single internal market during the 15th century. The previously relatively egalitarian state, which tightly controlled the movement of its population, transformed into a society with marked differences in property ownership. Government interventions became less prominent and people constantly moved in search of livelihood opportunities.

Notes

References

Citations

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * {{Cite book , last=Симоновская , first=Л. В , title=История Китая с древнейших времен до наших дней , last2=Юрьев , first2=М. Ф , publisher=Наука , year=1974 , location=Москва , language=ru Ming dynasty politics Reform