History Of The Molecule on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

In

An early precursor to the idea of bonded "combinations of atoms", was the theory of "combination via

An early precursor to the idea of bonded "combinations of atoms", was the theory of "combination via

Similar to these views, in 1803

Similar to these views, in 1803  In two papers outlining his "theory of atomicity of the elements" (1857–58), Friedrich August Kekulé was the first to offer a theory of how every atom in an organic molecule was bonded to every other atom. He proposed that carbon atoms were tetravalent, and could bond to themselves to form the carbon skeletons of organic molecules.

In 1856, Scottish chemist Archibald Couper began research on the

In two papers outlining his "theory of atomicity of the elements" (1857–58), Friedrich August Kekulé was the first to offer a theory of how every atom in an organic molecule was bonded to every other atom. He proposed that carbon atoms were tetravalent, and could bond to themselves to form the carbon skeletons of organic molecules.

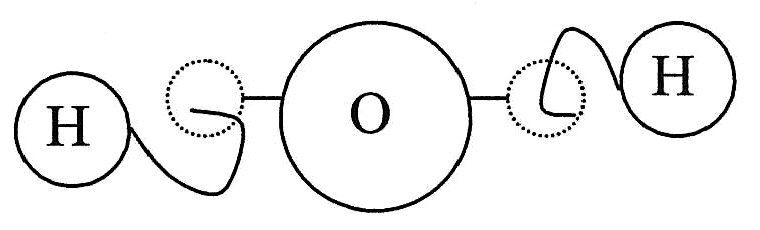

In 1856, Scottish chemist Archibald Couper began research on the  In 1861, an unknown Vienna high-school teacher named Joseph Loschmidt published, at his own expense, a booklet entitled ''Chemische Studien I'', containing pioneering molecular images which showed both "ringed" structures as well as double-bonded structures, such as:

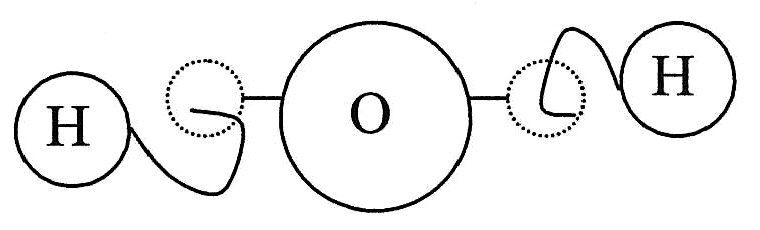

In 1861, an unknown Vienna high-school teacher named Joseph Loschmidt published, at his own expense, a booklet entitled ''Chemische Studien I'', containing pioneering molecular images which showed both "ringed" structures as well as double-bonded structures, such as:

Loschmidt also suggested a possible formula for benzene, but left the issue open. The first proposal of the modern structure for benzene was due to Kekulé, in 1865. The cyclic nature of benzene was finally confirmed by the crystallographer

Loschmidt also suggested a possible formula for benzene, but left the issue open. The first proposal of the modern structure for benzene was due to Kekulé, in 1865. The cyclic nature of benzene was finally confirmed by the crystallographer  In 1865, German chemist

In 1865, German chemist  The basis of this model followed the earlier 1855 suggestion by his colleague William Odling that

The basis of this model followed the earlier 1855 suggestion by his colleague William Odling that  In 1898,

In 1898,

The Atom and the Molecule

', Lewis introduced the "Lewis structure" to represent atoms and molecules, where dots represent In Lewis' own words:

Moreover, he proposed that an atom tended to form an ion by gaining or losing the number of electrons needed to complete a cube. Thus, Lewis structures show each atom in the structure of the molecule using its chemical symbol. Lines are drawn between atoms that are bonded to one another; occasionally, pairs of dots are used instead of lines. Excess electrons that form lone pairs are represented as pair of dots, and are placed next to the atoms on which they reside:

In Lewis' own words:

Moreover, he proposed that an atom tended to form an ion by gaining or losing the number of electrons needed to complete a cube. Thus, Lewis structures show each atom in the structure of the molecule using its chemical symbol. Lines are drawn between atoms that are bonded to one another; occasionally, pairs of dots are used instead of lines. Excess electrons that form lone pairs are represented as pair of dots, and are placed next to the atoms on which they reside:

To summarize his views on his new bonding model, Lewis states:

The following year, in 1917, an unknown American undergraduate chemical engineer named

To summarize his views on his new bonding model, Lewis states:

The following year, in 1917, an unknown American undergraduate chemical engineer named

manuscript

in which he used Owing to these exceptional theories, Pauling won the 1954

Owing to these exceptional theories, Pauling won the 1954 Single molecule's stunning image

Using an

Geometric Structures of Molecules

- Middlebury College

Atoms and Molecules

- McMaster University

3D Molecule Viewer

- The Wileys Family

- School of Chemistry, University of Bristol

- Eric Scerri's history & philosophy of chemistry website

Antibody Molecule

- The National Health Museum

15 Types of Molecules

- IUPAC Definitions

Molecule Definition

-

Definition of Molecule

- IUPAC

- TRN Newswire

- HP Labs {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Molecular Theory History of chemistry Molecules General chemistry

chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

, the history of molecular theory traces the origins of the concept or idea of the existence of strong chemical bonds between two or more atom

Atoms are the basic particles of the chemical elements. An atom consists of a atomic nucleus, nucleus of protons and generally neutrons, surrounded by an electromagnetically bound swarm of electrons. The chemical elements are distinguished fr ...

s.

A modern conceptualization of molecules began to develop in the 19th century along with experimental evidence for pure chemical elements

A chemical element is a chemical substance whose atoms all have the same number of protons. The number of protons is called the atomic number of that element. For example, oxygen has an atomic number of 8: each oxygen atom has 8 protons in i ...

and how individual atoms of different chemical elements such as hydrogen and oxygen can combine to form chemically stable molecules such as water molecules.

Ancient world

The modern concept of molecules can be traced back towards pre-scientific and Greek philosophers such asLeucippus

Leucippus (; , ''Leúkippos''; ) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. He is traditionally credited as the founder of atomism, which he developed with his student Democritus. Leucippus divided the world into two entities: atoms, indivisible ...

and Democritus

Democritus (, ; , ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, Thrace, Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an ...

who argued that all the universe is composed of atoms and voids.

Circa 450 BC Empedocles

Empedocles (; ; , 444–443 BC) was a Ancient Greece, Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is known best for originating the Cosmogony, cosmogonic theory of the four cla ...

imagined fundamental elements (fire

Fire is the rapid oxidation of a fuel in the exothermic chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction Product (chemistry), products.

Flames, the most visible portion of the fire, are produced in the combustion re ...

(), earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

(), air

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

(), and water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

()) and "forces" of attraction and repulsion allowing the elements to interact. Prior to this, Heraclitus

Heraclitus (; ; ) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic philosopher from the city of Ephesus, which was then part of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian Empire. He exerts a wide influence on Western philosophy, ...

had claimed that fire or change was fundamental to our existence, created through the combination of opposite properties.

In the Timaeus, Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

, following Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos (; BC) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher, polymath, and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His political and religious teachings were well known in Magna Graecia and influenced the philosophies of P ...

, considered mathematical entities such as number, point, line and triangle as the fundamental building blocks or elements of this ephemeral world, and considered the four elements of fire, air, water and earth as states of substances through which the true mathematical principles or elements would pass. A fifth element, the incorruptible quintessence aether, was considered to be the fundamental building block of the heavenly bodies.

The viewpoint of Leucippus and Empedocles, along with the aether, was accepted by Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

and passed to medieval and renaissance Europe.

Greek atomism

The earliest views on the shapes and connectivity of atoms was that proposed byLeucippus

Leucippus (; , ''Leúkippos''; ) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. He is traditionally credited as the founder of atomism, which he developed with his student Democritus. Leucippus divided the world into two entities: atoms, indivisible ...

, Democritus

Democritus (, ; , ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, Thrace, Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an ...

, and Epicurus

Epicurus (, ; ; 341–270 BC) was an Greek philosophy, ancient Greek philosopher who founded Epicureanism, a highly influential school of philosophy that asserted that philosophy's purpose is to attain as well as to help others attain tranqui ...

who reasoned that the solidness of the material corresponded to the shape of the atoms involved. Thus, iron atoms are solid and strong with hooks that lock them into a solid; water atoms are smooth and slippery; salt atoms, because of their taste, are sharp and pointed; and air atoms are light and whirling, pervading all other materials.

It was Democritus that was the main proponent of this view. Using analogies based on the experiences of the sense

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the surroundings through the detection of Stimulus (physiology), stimuli. Although, in some cultures, five human senses were traditio ...

s, he gave a picture or an image of an atom in which atoms were distinguished from each other by their shape, their size, and the arrangement of their parts. Moreover, connections were explained by material links in which single atoms were supplied with attachments: some with hooks and eyes others with balls and sockets (see diagram).

17th century

With the rise ofscholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

and the decline of the Roman Empire, the atomic theory was abandoned for many ages in favor of the various four element theories and later alchemical theories. The 17th century, however, saw a resurgence in the atomic theory primarily through the works of Gassendi, and Newton.

Among other scientists of that time Gassendi deeply studied ancient history, wrote major works about Epicurus

Epicurus (, ; ; 341–270 BC) was an Greek philosophy, ancient Greek philosopher who founded Epicureanism, a highly influential school of philosophy that asserted that philosophy's purpose is to attain as well as to help others attain tranqui ...

natural philosophy and was a persuasive propagandist of it. He reasoned that to account for the size and shape of atoms moving in a void could account for the properties of matter. Heat was due to small, round atoms; cold, to pyramidal atoms with sharp points, which accounted for the pricking sensation of severe cold; and solids were held together by interlacing hooks.

Newton, though he acknowledged the various atom attachment theories in vogue at the time, i.e. "hooked atoms", "glued atoms" (bodies at rest), and the "stick together by conspiring motions" theory, rather believed, as famously stated in "Query 31" of his 1704 ''Opticks

''Opticks: or, A Treatise of the Reflexions, Refractions, Inflexions and Colours of Light'' is a collection of three books by Isaac Newton that was published in English language, English in 1704 (a scholarly Latin translation appeared in 1706). ...

'', that particles attract one another by some force, which "in immediate contact is extremely strong, at small distances performs the chemical operations, and reaches not far from particles with any sensible effect."

In a more concrete manner, however, the concept of aggregates or units of bonded atoms, i.e. "molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms that are held together by Force, attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions that satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemi ...

s", traces its origins to Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, Alchemy, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the foun ...

's 1661 hypothesis, in his famous treatise ''The Sceptical Chymist

''The Sceptical Chymist: or Chymico-Physical Doubts & Paradoxes'' is the title of a book by Robert Boyle, published in London in 1661. In the form of a dialogue, the ''Sceptical Chymist'' presented Boyle's hypothesis that matter consisted of cor ...

'', that matter is composed of ''clusters of particle

In the physical sciences, a particle (or corpuscle in older texts) is a small localized object which can be described by several physical or chemical properties, such as volume, density, or mass.

They vary greatly in size or quantity, from s ...

s'' and that chemical change results from the rearrangement of the clusters. Boyle argued that matter's basic elements consisted of various sorts and sizes of particles, called " corpuscles", which were capable of arranging themselves into groups.

In 1680, using the corpuscular theory

In optics, the corpuscular theory of light states that light is made up of small discrete particles called " corpuscles" (little particles) which travel in a straight line with a finite velocity and possess impetus. This notion was based on an al ...

as a basis, French chemist Nicolas Lemery

Nicolas Lémery (or Lemery as his name appeared in his international publications) (17 November 1645 – 19 June 1715), French chemist, was born at Rouen. He was one of the first to develop theories on acid-base chemistry.

Life

After learning ph ...

stipulated that the acidity

An acid is a molecule or ion capable of either donating a proton (i.e. hydrogen cation, H+), known as a Brønsted–Lowry acid, or forming a covalent bond with an electron pair, known as a Lewis acid.

The first category of acids are the ...

of any substance consisted in its pointed particles, while alkalis

In chemistry, an alkali (; from the Arabic word , ) is a basic salt of an alkali metal or an alkaline earth metal. An alkali can also be defined as a base that dissolves in water. A solution of a soluble base has a pH greater than 7.0. The a ...

were endowed with pores of various sizes. A molecule, according to this view, consisted of corpuscles united through a geometric locking of points and pores.

18th century

An early precursor to the idea of bonded "combinations of atoms", was the theory of "combination via

An early precursor to the idea of bonded "combinations of atoms", was the theory of "combination via chemical affinity

In chemical physics and physical chemistry, chemical affinity is the electronic property by which dissimilar chemical species are capable of forming chemical compounds. Chemical affinity can also refer to the tendency of an atom or compound to com ...

". For example, in 1718, building on Boyle's conception of combinations of clusters, the French chemist Étienne François Geoffroy developed theories of chemical affinity

In chemical physics and physical chemistry, chemical affinity is the electronic property by which dissimilar chemical species are capable of forming chemical compounds. Chemical affinity can also refer to the tendency of an atom or compound to com ...

to explain combinations of particles, reasoning that a certain alchemical "force" draws certain alchemical components together. Geoffroy's name is best known in connection with his tables of " affinities" (''tables des rapports''), which he presented to the French Academy

French may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France

** French people, a nation and ethnic group

** French cuisine, cooking traditions and practices

Arts and media

* The French (band), ...

in 1718 and 1720.

These were lists, prepared by collating observations on the actions of substances one upon another, showing the varying degrees of affinity exhibited by analogous bodies for different reagent

In chemistry, a reagent ( ) or analytical reagent is a substance or compound added to a system to cause a chemical reaction, or test if one occurs. The terms ''reactant'' and ''reagent'' are often used interchangeably, but reactant specifies a ...

s. These tables retained their vogue for the rest of the century, until displaced by the profounder conceptions introduced by CL Berthollet.

In 1738, Swiss physicist and mathematician Daniel Bernoulli

Daniel Bernoulli ( ; ; – 27 March 1782) was a Swiss people, Swiss-France, French mathematician and physicist and was one of the many prominent mathematicians in the Bernoulli family from Basel. He is particularly remembered for his applicati ...

published ''Hydrodynamica

''Hydrodynamica, sive de Viribus et Motibus Fluidorum Commentarii'' (Latin for ''Hydrodynamics, or commentaries on the forces and motions of fluids'') is a book published by Daniel Bernoulli in 1738. The title of this book eventually christened ...

'', which laid the basis for the kinetic theory of gases. In this work, Bernoulli positioned the argument, still used to this day, that gas

Gas is a state of matter that has neither a fixed volume nor a fixed shape and is a compressible fluid. A ''pure gas'' is made up of individual atoms (e.g. a noble gas like neon) or molecules of either a single type of atom ( elements such as ...

es consist of great numbers of molecules moving in all directions, that their impact on a surface causes the gas pressure

Pressure (symbol: ''p'' or ''P'') is the force applied perpendicular to the surface of an object per unit area over which that force is distributed. Gauge pressure (also spelled ''gage'' pressure)The preferred spelling varies by country and eve ...

that we feel, and that what we experience as heat

In thermodynamics, heat is energy in transfer between a thermodynamic system and its surroundings by such mechanisms as thermal conduction, electromagnetic radiation, and friction, which are microscopic in nature, involving sub-atomic, ato ...

is simply the kinetic energy of their motion. The theory was not immediately accepted, in part because conservation of energy

The law of conservation of energy states that the total energy of an isolated system remains constant; it is said to be Conservation law, ''conserved'' over time. In the case of a Closed system#In thermodynamics, closed system, the principle s ...

had not yet been established, and it was not obvious to physicists how the collisions between molecules could be perfectly elastic.

In 1789, William Higgins published views on what he called combinations of "ultimate" particles, which foreshadowed the concept of valency bonds. If, for example, according to Higgins, the force between the ultimate particle of oxygen and the ultimate particle of nitrogen were 6, then the strength of the force would be divided accordingly, and similarly for the other combinations of ultimate particles:

19th century

Similar to these views, in 1803

Similar to these views, in 1803 John Dalton

John Dalton (; 5 or 6 September 1766 – 27 July 1844) was an English chemist, physicist and meteorologist. He introduced the atomic theory into chemistry. He also researched Color blindness, colour blindness; as a result, the umbrella term ...

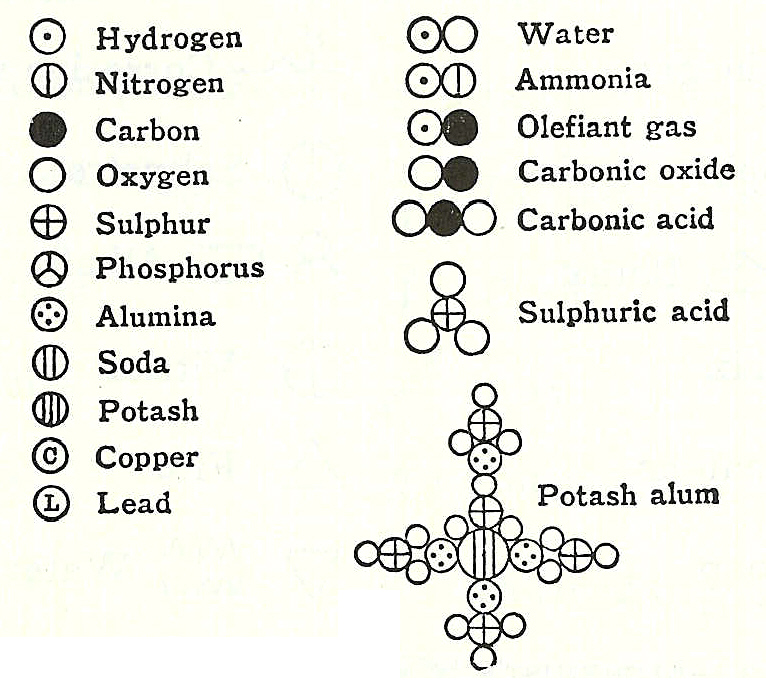

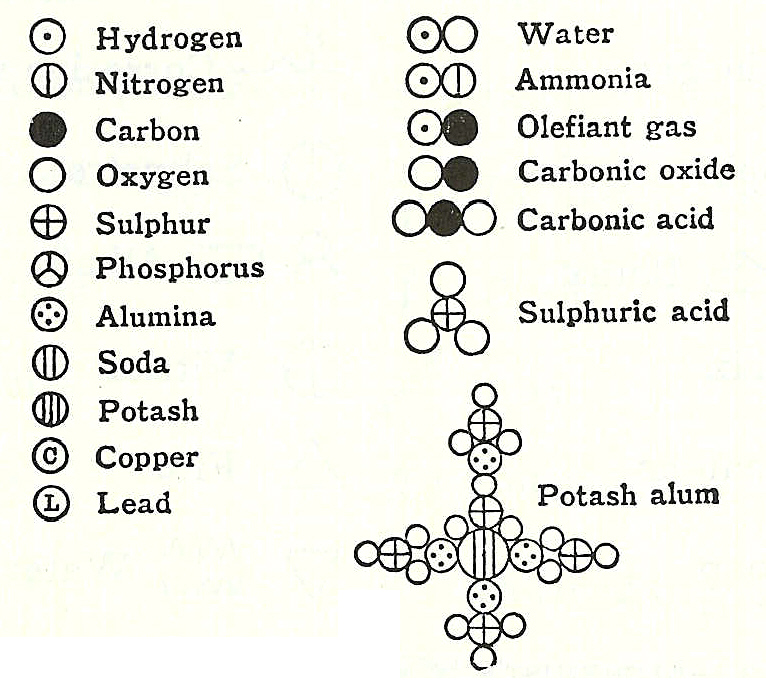

took the atomic weight of hydrogen, the lightest element, as unity, and determined, for example, that the ratio for nitrous anhydride was 2 to 3 which gives the formula N2O3. Dalton incorrectly imagined that atoms "hooked" together to form molecules. Later, in 1808, Dalton published his famous diagram of combined "atoms":

Amedeo Avogadro

Lorenzo Romano Amedeo Carlo Avogadro, Count of Quaregna and Cerreto (, also , ; 9 August 17769 July 1856) was an Italian scientist, most noted for his contribution to molecular theory now known as Avogadro's law, which states that equal volu ...

created the word "molecule".

His 1811 paper "Essay on Determining the Relative Masses of the Elementary Molecules of Bodies", he essentially states, i.e. according to Partington

Partington is a town and civil parish in the Metropolitan Borough of Trafford, Greater Manchester, England. It is sited south-west of Manchester city centre. Within the boundaries of the Historic counties of England, historic county of Ches ...

's ''A Short History of Chemistry'', that:

Note that this quote is not a literal translation. Avogadro uses the name "molecule" for both atoms and molecules. Specifically, he uses the name "elementary molecule" when referring to atoms and to complicate the matter also speaks of "compound molecules" and "composite molecules".

During his stay in Vercelli, Avogadro wrote a concise note (''memoria'') in which he declared the hypothesis of what we now call Avogadro's law

Avogadro's law (sometimes referred to as Avogadro's hypothesis or Avogadro's principle) or Avogadro-Ampère's hypothesis is an experimental gas law relating the volume of a gas to the amount of substance of gas present. The law is a specific cas ...

: ''equal volumes of gases, at the same temperature and pressure, contain the same number of molecules''. This law implies that the relationship occurring between the weights of same volumes of different gases, at the same temperature and pressure, corresponds to the relationship between respective molecular weight

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms that are held together by Force, attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions that satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemi ...

s. Hence, relative molecular masses could now be calculated from the masses of gas samples.

Avogadro developed this hypothesis to reconcile Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac

Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac ( , ; ; 6 December 1778 – 9 May 1850) was a French chemist and physicist. He is known mostly for his discovery that water is made of two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen by volume (with Alexander von Humboldt), f ...

's 1808 law on volumes and combining gases with Dalton's 1803 atomic theory

Atomic theory is the scientific theory that matter is composed of particles called atoms. The definition of the word "atom" has changed over the years in response to scientific discoveries. Initially, it referred to a hypothetical concept of ...

. The greatest difficulty Avogadro had to resolve was the huge confusion at that time regarding atoms and molecules—one of the most important contributions of Avogadro's work was clearly distinguishing one from the other, admitting that simple particles too could be composed of molecules and that these are composed of atoms. Dalton, by contrast, did not consider this possibility. Curiously, Avogadro considers only molecules containing even numbers of atoms; he does not say why odd numbers are left out.

In 1826, building on the work of Avogadro, the French chemist Jean-Baptiste Dumas

Jean Baptiste André Dumas (; 14 July 180010 April 1884) was a French chemist, best known for his works on organic analysis and synthesis, as well as the determination of atomic weights (relative atomic masses) and molecular weights by measuri ...

states:

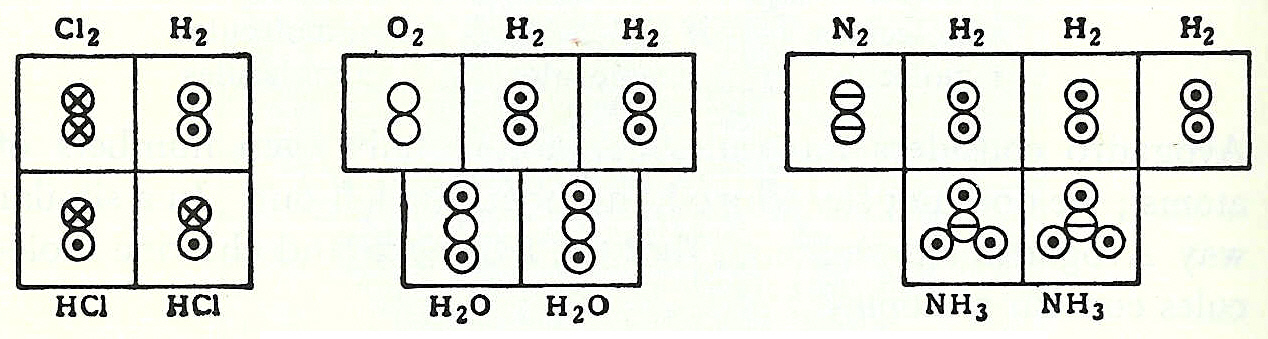

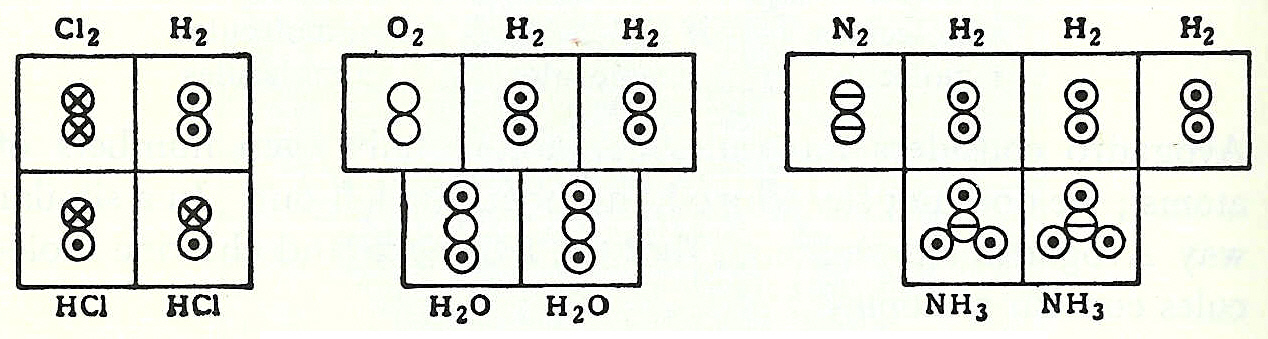

In coordination with these concepts, in 1833 the French chemist Marc Antoine Auguste Gaudin presented a clear account of Avogadro's hypothesis, regarding atomic weights, by making use of "volume diagrams", which clearly show both semi-correct molecular geometries, such as a linear water molecule, and correct molecular formulas, such as H2O:

In two papers outlining his "theory of atomicity of the elements" (1857–58), Friedrich August Kekulé was the first to offer a theory of how every atom in an organic molecule was bonded to every other atom. He proposed that carbon atoms were tetravalent, and could bond to themselves to form the carbon skeletons of organic molecules.

In 1856, Scottish chemist Archibald Couper began research on the

In two papers outlining his "theory of atomicity of the elements" (1857–58), Friedrich August Kekulé was the first to offer a theory of how every atom in an organic molecule was bonded to every other atom. He proposed that carbon atoms were tetravalent, and could bond to themselves to form the carbon skeletons of organic molecules.

In 1856, Scottish chemist Archibald Couper began research on the bromination

In chemistry, halogenation is a chemical reaction which introduces one or more halogens into a chemical compound. Halide-containing compounds are pervasive, making this type of transformation important, e.g. in the production of polymers, drugs ...

of benzene at the laboratory of Charles Wurtz in Paris. One month after Kekulé's second paper appeared, Couper's independent and largely identical theory of molecular structure was published. He offered a very concrete idea of molecular structure, proposing that atoms joined to each other like modern-day Tinkertoys in specific three-dimensional structures. Couper was the first to use lines between atoms, in conjunction with the older method of using brackets, to represent bonds, and also postulated straight chains of atoms as the structures of some molecules, ring-shaped molecules of others, such as in tartaric acid

Tartaric acid is a white, crystalline organic acid that occurs naturally in many fruits, most notably in grapes but also in tamarinds, bananas, avocados, and citrus. Its salt (chemistry), salt, potassium bitartrate, commonly known as cream of ta ...

and cyanuric acid

Cyanuric acid or 1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6-triol is a chemical compound with the chemical formula, formula (CNOH)3. Like many industrially useful chemicals, this triazine has many synonyms. This white, odorless solid finds use as a precursor or a com ...

. In later publications, Couper's bonds were represented using straight dotted lines (although it is not known if this is the typesetter's preference) such as with alcohol

Alcohol may refer to:

Common uses

* Alcohol (chemistry), a class of compounds

* Ethanol, one of several alcohols, commonly known as alcohol in everyday life

** Alcohol (drug), intoxicant found in alcoholic beverages

** Alcoholic beverage, an alco ...

and oxalic acid

Oxalic acid is an organic acid with the systematic name ethanedioic acid and chemical formula , also written as or or . It is the simplest dicarboxylic acid. It is a white crystalline solid that forms a colorless solution in water. Its name i ...

below:

In 1861, an unknown Vienna high-school teacher named Joseph Loschmidt published, at his own expense, a booklet entitled ''Chemische Studien I'', containing pioneering molecular images which showed both "ringed" structures as well as double-bonded structures, such as:

In 1861, an unknown Vienna high-school teacher named Joseph Loschmidt published, at his own expense, a booklet entitled ''Chemische Studien I'', containing pioneering molecular images which showed both "ringed" structures as well as double-bonded structures, such as:

Loschmidt also suggested a possible formula for benzene, but left the issue open. The first proposal of the modern structure for benzene was due to Kekulé, in 1865. The cyclic nature of benzene was finally confirmed by the crystallographer

Loschmidt also suggested a possible formula for benzene, but left the issue open. The first proposal of the modern structure for benzene was due to Kekulé, in 1865. The cyclic nature of benzene was finally confirmed by the crystallographer Kathleen Lonsdale

Dame Kathleen Lonsdale ( Yardley; 28 January 1903 – 1 April 1971) was an Irish crystallographer, pacifist, and prison reform activist. She proved, in 1929, that the benzene ring is flat by using X-ray diffraction methods to elucidate the str ...

. Benzene presents a special problem in that, to account for all the bonds, there must be alternating double

Double, The Double or Dubble may refer to:

Mathematics and computing

* Multiplication by 2

* Double precision, a floating-point representation of numbers that is typically 64 bits in length

* A double number of the form x+yj, where j^2=+1

* A ...

carbon bonds:

August Wilhelm von Hofmann

August Wilhelm von Hofmann (8 April 18185 May 1892) was a German chemist who made considerable contributions to organic chemistry. His research on aniline helped lay the basis of the aniline-dye industry, and his research on coal tar laid the g ...

was the first to make stick-and-ball molecular models, which he used in lecture at the Royal Institution of Great Britain

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

, such as methane shown below:

The basis of this model followed the earlier 1855 suggestion by his colleague William Odling that

The basis of this model followed the earlier 1855 suggestion by his colleague William Odling that carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

is tetravalent. Hofmann's color scheme, to note, is still used to this day: carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

= black, nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a Nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal and the lightest member of pnictogen, group 15 of the periodic table, often called the Pnictogen, pnictogens. ...

= blue, oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

= red, chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate between ...

= green, sulfur

Sulfur ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphur ( Commonwealth spelling) is a chemical element; it has symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms ...

= yellow, hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

= white. The deficiencies in Hofmann's model were essentially geometric: carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

bonding was shown as planar, rather than tetrahedral, and the atoms were out of proportion, e.g. carbon was smaller in size than the hydrogen.

In 1864, Scottish organic chemist Alexander Crum Brown

Alexander Crum Brown Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, FRSE Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (26 March 1838 – 28 October 1922) was a Scottish Organic chemistry, organic chemist. Alexander Crum Brown Road in Edinburgh's King's Buildi ...

began to draw pictures of molecules, in which he enclosed the symbols for atoms in circles, and used broken lines to connect the atoms together in a way that satisfied each atom's valence.

The year 1873, by many accounts, was a seminal point in the history of the development of the concept of the "molecule". In this year, the renowned Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish physicist and mathematician who was responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism an ...

published his famous thirteen page article 'Molecules' in the September issue of ''Nature''. In the opening section to this article, Maxwell clearly states:

After speaking about the atomic theory

Atomic theory is the scientific theory that matter is composed of particles called atoms. The definition of the word "atom" has changed over the years in response to scientific discoveries. Initially, it referred to a hypothetical concept of ...

of Democritus

Democritus (, ; , ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, Thrace, Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an ...

, Maxwell goes on to tell us that the word 'molecule' is a modern word. He states, "it does not occur in '' Johnson's Dictionary''. The ideas it embodies are those belonging to modern chemistry." We are told that an 'atom' is a material point, invested and surrounded by 'potential forces' and that when 'flying molecules' strike against a solid body in constant succession it causes what is called pressure

Pressure (symbol: ''p'' or ''P'') is the force applied perpendicular to the surface of an object per unit area over which that force is distributed. Gauge pressure (also spelled ''gage'' pressure)The preferred spelling varies by country and eve ...

of air and other gases. At this point, however, Maxwell notes that no one has ever seen or handled a molecule.

In 1874, Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff

Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff Jr. (; 30 August 1852 – 1 March 1911) was a Dutch physical chemistry, physical chemist. A highly influential theoretical chemistry, theoretical chemist of his time, Van 't Hoff was the first winner of the Nobe ...

and Joseph Achille Le Bel independently proposed that the phenomenon of optical activity

Optical rotation, also known as polarization rotation or circular birefringence, is the rotation of the orientation of the plane of polarization about the optical axis of linearly polarized light as it travels through certain materials. Circul ...

could be explained by assuming that the chemical bonds between carbon atoms and their neighbors were directed towards the corners of a regular tetrahedron. This led to a better understanding of the three-dimensional nature of molecules.

Emil Fischer

Hermann Emil Louis Fischer (; 9 October 1852 – 15 July 1919) was a German chemist and List of Nobel laureates in Chemistry, 1902 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He discovered the Fischer esterification. He also developed the Fisch ...

developed the Fischer projection

In chemistry, the Fischer projection, devised by Emil Fischer in 1891, is a two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional organic molecule by projection. Fischer projections were originally proposed for the depiction of carbohydrates a ...

technique for viewing 3-D molecules on a 2-D sheet of paper:

Ludwig Boltzmann

Ludwig Eduard Boltzmann ( ; ; 20 February 1844 – 5 September 1906) was an Austrian mathematician and Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist. His greatest achievements were the development of statistical mechanics and the statistical ex ...

, in his ''Lectures on Gas Theory'', used the theory of valence to explain the phenomenon of gas phase molecular dissociation, and in doing so drew one of the first rudimentary yet detailed atomic orbital overlap drawings. Noting first the known fact that molecular iodine

Iodine is a chemical element; it has symbol I and atomic number 53. The heaviest of the stable halogens, it exists at standard conditions as a semi-lustrous, non-metallic solid that melts to form a deep violet liquid at , and boils to a vi ...

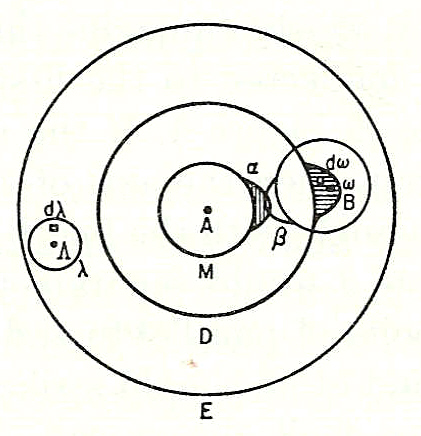

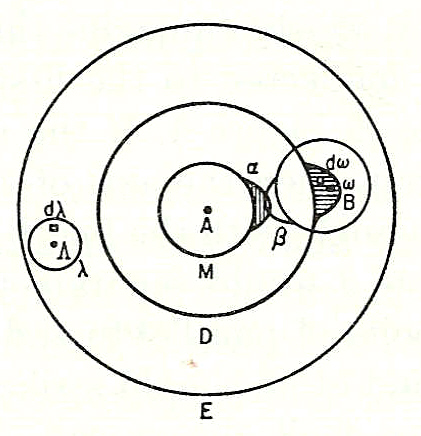

vapor dissociates into atoms at higher temperatures, Boltzmann states that we must explain the existence of molecules composed of two atoms, the "double atom" as Boltzmann calls it, by an attractive force acting between the two atoms. Boltzmann states that this chemical attraction, owing to certain facts of chemical valence, must be associated with a relatively small region on the surface of the atom called the ''sensitive region''.

Boltzmann states that this "sensitive region" will lie on the surface of the atom, or may partially lie inside the atom, and will firmly be connected to it. Specifically, he states "only when two atoms are situated so that their sensitive regions are in contact, or partly overlap, will there be a chemical attraction between them. We then say that they are chemically bound to each other." This picture is detailed below, showing the ''α-sensitive region'' of atom-A overlapping with the ''β-sensitive region'' of atom-B:

20th century

In the early 20th century, the American chemistGilbert N. Lewis

Gilbert Newton Lewis (October 23 or October 25, 1875 – March 23, 1946) was an American physical chemist and a dean of the college of chemistry at University of California, Berkeley. Lewis was best known for his discovery of the covalent bon ...

began to use dots in lecture, while teaching undergraduates at Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher lear ...

, to represent the electrons around atoms. His students favored these drawings, which stimulated him in this direction. From these lectures, Lewis noted that elements with a certain number of electrons seemed to have a special stability. This phenomenon was pointed out by the German chemist Richard Abegg in 1904, to which Lewis referred to as "Abegg's law of valence" (now generally known as Abegg's rule). To Lewis it appeared that once a core of eight electrons has formed around a nucleus, the layer is filled, and a new layer is started. Lewis also noted that various ion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge. The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

s with eight electrons also seemed to have a special stability. On these views, he proposed the rule of eight or octet rule

The octet rule is a chemical rule of thumb that reflects the theory that main-group elements tend to bond in such a way that each atom has eight electrons in its valence shell, giving it the same electronic configuration as a noble gas. The ru ...

: ''Ions or atoms with a filled layer of eight electrons have a special stability''.

Moreover, noting that a cube has eight corners Lewis envisioned an atom as having eight sides available for electrons, like the corner of a cube. Subsequently, in 1902 he devised a conception in which cubic atoms can bond on their sides to form cubic-structured molecules.

In other words, electron-pair bonds are formed when two atoms share an edge, as in structure C below. This results in the sharing of two electrons. Similarly, charged ionic-bonds are formed by the transfer of an electron from one cube to another, without sharing an edge A. An intermediate state B where only one corner is shared was also postulated by Lewis.

Hence, double bond

In chemistry, a double bond is a covalent bond between two atoms involving four bonding electrons as opposed to two in a single bond. Double bonds occur most commonly between two carbon atoms, for example in alkenes. Many double bonds exist betw ...

s are formed by sharing a face between two cubic atoms. This results in the sharing of four electrons.

In 1913, while working as the chair of the department of chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

, Lewis read a preliminary outline of paper by an English graduate student, Alfred Lauck Parson, who was visiting Berkeley for a year. In this paper, Parson suggested that the electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

is not merely an electric charge but is also a small magnet (or " magneton" as he called it) and furthermore that a chemical bond

A chemical bond is the association of atoms or ions to form molecules, crystals, and other structures. The bond may result from the electrostatic force between oppositely charged ions as in ionic bonds or through the sharing of electrons a ...

results from two electrons being shared between two atoms. This, according to Lewis, meant that bonding occurred when two electrons formed a shared edge between two complete cubes.

On these views, in his famous 1916 article The Atom and the Molecule

', Lewis introduced the "Lewis structure" to represent atoms and molecules, where dots represent

electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

s and lines represent covalent bond

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atom ...

s. In this article, he developed the concept of the electron-pair bond, in which two atoms may share one to six electrons, thus forming the single electron bond, a single bond

In chemistry, a single bond is a chemical bond between two atoms involving two valence electrons. That is, the atoms share one pair of electrons where the bond forms. Therefore, a single bond is a type of covalent bond. When shared, each of th ...

, a double bond

In chemistry, a double bond is a covalent bond between two atoms involving four bonding electrons as opposed to two in a single bond. Double bonds occur most commonly between two carbon atoms, for example in alkenes. Many double bonds exist betw ...

, or a triple bond

A triple bond in chemistry is a chemical bond between two atoms involving six Electron pair bond, bonding electrons instead of the usual two in a covalent bond, covalent single bond. Triple bonds are stronger than the equivalent covalent bond, sin ...

.

Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling ( ; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist and peace activist. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topics. ''New Scientist'' called him one of the 20 gre ...

was learning the Dalton hook-and-eye bonding method at the Oregon Agricultural College, which was the vogue description of bonds between atoms at the time. Each atom had a certain number of hooks that allowed it to attach to other atoms, and a certain number of eyes that allowed other atoms to attach to it. A chemical bond resulted when a hook and eye connected. Pauling, however, wasn't satisfied with this archaic method and looked to the newly emerging field of quantum physics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

for a new method.

In 1927, the physicists Fritz London

Fritz Wolfgang London (March 7, 1900 – March 30, 1954) was a German born physicist and professor at Duke University. His fundamental contributions to the theories of chemical bonding and of intermolecular forces (London dispersion forces) are to ...

and Walter Heitler

Walter Heinrich Heitler (; 2 January 1904 – 15 November 1981) was a German physicist who made contributions to quantum electrodynamics and quantum field theory. He brought chemistry under quantum mechanics through his theory of valence bondi ...

applied the new quantum mechanics to the deal with the saturable, nondynamic forces of attraction and repulsion, i.e., exchange forces, of the hydrogen molecule. Their valence bond treatment of this problem, in their joint paper, was a landmark in that it brought chemistry under quantum mechanics. Their work was an influence on Pauling, who had just received his doctorate and visited Heitler and London in Zürich on a Guggenheim Fellowship

Guggenheim Fellowships are Grant (money), grants that have been awarded annually since by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, endowed by the late Simon Guggenheim, Simon and Olga Hirsh Guggenheim. These awards are bestowed upon indiv ...

.

Subsequently, in 1931, building on the work of Heitler and London and on theories found in Lewis' famous article, Pauling published his ground-breaking article "The Nature of the Chemical Bond" (seemanuscript

in which he used

quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

to calculate properties and structures of molecules, such as angles between bonds and rotation about bonds. On these concepts, Pauling developed hybridization theory to account for bonds in molecules such as CH4, in which four sp³ hybridised orbitals are overlapped by hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

's ''1s'' orbital, yielding four sigma (σ) bonds. The four bonds are of the same length and strength, which yields a molecular structure as shown below:

Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry () is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outst ...

. Notably he has been the only person to ever win two unshared Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

s, winning the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

in 1963.

In 1926, French physicist Jean Perrin received the Nobel Prize in physics for proving, conclusively, the existence of molecules. He did this by calculating the Avogadro number

The Avogadro constant, commonly denoted or , is an SI defining constant with an exact value of when expressed in reciprocal moles.

It defines the ratio of the number of constituent particles to the amount of substance in a sample, where th ...

using three different methods, all involving liquid phase systems. First, he used a gamboge soap-like emulsion, second by doing experimental work on Brownian motion

Brownian motion is the random motion of particles suspended in a medium (a liquid or a gas). The traditional mathematical formulation of Brownian motion is that of the Wiener process, which is often called Brownian motion, even in mathematical ...

, and third by confirming Einstein's theory of particle rotation in the liquid phase.

In 1937, chemist K.L. Wolf introduced the concept of supermolecules (''Übermoleküle'') to describe hydrogen bonding

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (H-bond) is a specific type of molecular interaction that exhibits partial covalent character and cannot be described as a purely electrostatic force. It occurs when a hydrogen (H) atom, Covalent bond, covalently b ...

in acetic acid

Acetic acid , systematically named ethanoic acid , is an acidic, colourless liquid and organic compound with the chemical formula (also written as , , or ). Vinegar is at least 4% acetic acid by volume, making acetic acid the main compone ...

dimers. This would eventually lead to the area of supermolecular chemistry

Supramolecular chemistry refers to the branch of chemistry concerning chemical systems composed of a discrete number of molecules. The strength of the forces responsible for spatial organization of the system range from weak intermolecular forces ...

, which is the study of non-covalent bonding.

In 1951, physicist Erwin Wilhelm Müller

Erwin Wilhelm Müller (or ''Mueller'') (June 13, 1911 – May 17, 1977) was a German physicist who invented the Field Emission Electron Microscope (FEEM), the Field Ion Microscope (FIM), and the Atom-Probe Field Ion Microscope. He and his s ...

invents the field ion microscope

The field-ion microscope (FIM) was invented by Müller in 1951. It is a type of microscope that can be used to image the arrangement of atoms at the surface of a sharp metal tip.

On October 11, 1955, Erwin Müller and his Ph.D. student, Kanwar B ...

and is the first to see atom

Atoms are the basic particles of the chemical elements. An atom consists of a atomic nucleus, nucleus of protons and generally neutrons, surrounded by an electromagnetically bound swarm of electrons. The chemical elements are distinguished fr ...

s, e.g. bonded atomic arrangements at the tip of a metal point.

In 1999, researchers from the University

A university () is an educational institution, institution of tertiary education and research which awards academic degrees in several Discipline (academia), academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase , which roughly ...

of Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

reported results from experiments on wave-particle duality for C60 molecules. The data published by Anton Zeilinger

Anton Zeilinger (; born 20 May 1945) is an Austrian quantum physicist and Nobel laureate in physics of 2022. Zeilinger is professor of physics emeritus at the University of Vienna and senior scientist at the Institute for Quantum Optics and Qu ...

et al. were consistent with Louis de Broglie

Louis Victor Pierre Raymond, 7th Duc de Broglie (15 August 1892 – 19 March 1987) was a French theoretical physicist and aristocrat known for his contributions to quantum theory. In his 1924 PhD thesis, he postulated the wave nature of elec ...

's matter waves

Matter waves are a central part of the theory of quantum mechanics, being half of wave–particle duality. At all scales where measurements have been practical, matter exhibits wave-like behavior. For example, a beam of electrons can be diffract ...

. This experiment was noted for extending the applicability of wave–particle duality by about one order of magnitude in the macroscopic direction.

In 2009, researchers from IBM

International Business Machines Corporation (using the trademark IBM), nicknamed Big Blue, is an American Multinational corporation, multinational technology company headquartered in Armonk, New York, and present in over 175 countries. It is ...

managed to take the first picture of a real molecule.Using an

atomic force microscope

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) or scanning force microscopy (SFM) is a very-high-resolution type of scanning probe microscopy (SPM), with demonstrated resolution on the order of fractions of a nanometer, more than 1000 times better than the diffr ...

every single atom and bond of a pentacene molecule could be imaged.

See also

*History of chemistry

The history of chemistry represents a time span from ancient history to the present. By 1000 BC, civilizations used technologies that would eventually form the basis of the various branches of chemistry. Examples include the discovery of fire, ex ...

* History of quantum mechanics

The history of quantum mechanics is a fundamental part of the History of physics#20th century: birth of modern physics, history of modern physics. The major chapters of this history begin with the emergence of quantum ideas to explain individual ...

* History of thermodynamics

The history of thermodynamics is a fundamental strand in the history of physics, the history of chemistry, and the history of science in general. Due to the relevance of thermodynamics in much of science and technology, its history is finely wov ...

* History of molecular biology

The history of molecular biology begins in the 1930s with the convergence of various, previously distinct biological and physical disciplines: biochemistry, genetics, microbiology, virology and physics. With the hope of understanding life at its m ...

* Kinetic theory of gases

The kinetic theory of gases is a simple classical model of the thermodynamic behavior of gases. Its introduction allowed many principal concepts of thermodynamics to be established. It treats a gas as composed of numerous particles, too small ...

* Atomic theory

Atomic theory is the scientific theory that matter is composed of particles called atoms. The definition of the word "atom" has changed over the years in response to scientific discoveries. Initially, it referred to a hypothetical concept of ...

References

Further reading

* * * *External links

Geometric Structures of Molecules

- Middlebury College

Atoms and Molecules

- McMaster University

3D Molecule Viewer

- The Wileys Family

- School of Chemistry, University of Bristol

- Eric Scerri's history & philosophy of chemistry website

Types

Antibody Molecule

- The National Health Museum

15 Types of Molecules

- IUPAC Definitions

Definitions

Molecule Definition

-

Frostburg State University

Frostburg State University (FSU) is a public university in Frostburg, Maryland. The university is the only four-year institution of the University System of Maryland west of the Baltimore-Washington passageway in the state's Appalachian highlan ...

(Department of Chemistry)

Definition of Molecule

- IUPAC

Articles

- TRN Newswire

- HP Labs {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Molecular Theory History of chemistry Molecules General chemistry