History Of The Jews In Atlanta on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the Jews in Atlanta began in the early years of the city's settlement, and the

Rabbi Tobias Geffen was born in Lithuania, received his ordination there, and started his family there before immigrating to the U.S. He first settled in New York and Ohio prior to accepting his position at Shearith Israel and moving with his family to Atlanta in 1910. Upon his arrival, Rabbi Geffen noted a number of problems and gaps in the Orthodox community and sought to remedy them, including the lack of religious schools, the state of the community's

Rabbi Tobias Geffen was born in Lithuania, received his ordination there, and started his family there before immigrating to the U.S. He first settled in New York and Ohio prior to accepting his position at Shearith Israel and moving with his family to Atlanta in 1910. Upon his arrival, Rabbi Geffen noted a number of problems and gaps in the Orthodox community and sought to remedy them, including the lack of religious schools, the state of the community's

Under the 51-year tenure of Rabbi David Marx, the members of The Temple were used to the idea that if it wanted acceptance, it could not afford to rock the boat in non-Jewish/Christian Atlanta society or cause conflict. The congregation's next rabbi, Jacob Rothschild, however, took a different attitude and felt that advocating against segregation and discrimination were moral imperatives, controversial or not. Many believe that Rabbi Rothschild's outspoken support for the Civil Rights Movement and integration lead to the targeting of The Temple.

In the first hours of October 12, 1958, The Temple was bombed using 50 sticks of dynamite, causing significant damage but no injuries. Not long after the explosion,

Under the 51-year tenure of Rabbi David Marx, the members of The Temple were used to the idea that if it wanted acceptance, it could not afford to rock the boat in non-Jewish/Christian Atlanta society or cause conflict. The congregation's next rabbi, Jacob Rothschild, however, took a different attitude and felt that advocating against segregation and discrimination were moral imperatives, controversial or not. Many believe that Rabbi Rothschild's outspoken support for the Civil Rights Movement and integration lead to the targeting of The Temple.

In the first hours of October 12, 1958, The Temple was bombed using 50 sticks of dynamite, causing significant damage but no injuries. Not long after the explosion,

In the decades following The Temple bombing, the Jewish community also became active in politics again. In 1961, Sam Massell was elected Vice Mayor of the city, and then re-elected in 1965. In 1969, he was elected the first Jewish mayor the city, after winning the vast majority of the African American vote and losing the vast majority of the white vote. A part of his campaign pitch to the African American community was that his experience being Jewish, while not equivalent to the black experience, gave him a better understanding than other white people of the challenges community was facing. He was defeated by

In the decades following The Temple bombing, the Jewish community also became active in politics again. In 1961, Sam Massell was elected Vice Mayor of the city, and then re-elected in 1965. In 1969, he was elected the first Jewish mayor the city, after winning the vast majority of the African American vote and losing the vast majority of the white vote. A part of his campaign pitch to the African American community was that his experience being Jewish, while not equivalent to the black experience, gave him a better understanding than other white people of the challenges community was facing. He was defeated by

The Atlanta Jewish community has seen dramatic population boom and demographic change in the last few decades, while Atlanta's overall population has also reached new heights as one of the fastest-growing cities in the U.S. The Jewish community in the metropolitan area went from less than 30,000 in 1980 to 86,000 in 2000 and then 120,000 in 2006 when the last Jewish population survey was undertaken. If Jewish population growth mirrored the general population growth, the Jewish population would have been 130,000 in 2016.

Whereas much of the Atlanta Jewish community has historically been deeply rooted families that prided in their Atlanta and Southern ties, the vast majority of the community today is made up of transplants, and almost a third of the community was born in New York. According to the 2006 population survey, Jews who have moved to the area in the last 10 years also outnumber those born in the area, particularly in the northern suburbs.

The number of community institutions and organizations has also increased to keep up with the needs of the community. Today there are 38 synagogues in the area – 33 founded after 1968, of which 24 were started between 1984 and 2006. The Orthodox portion of the community is also rapidly growing, and over half of these new congregations are Orthodox or traditional. This has been coupled with an increasing number of kosher restaurants and supermarket sections and the establishment of

The Atlanta Jewish community has seen dramatic population boom and demographic change in the last few decades, while Atlanta's overall population has also reached new heights as one of the fastest-growing cities in the U.S. The Jewish community in the metropolitan area went from less than 30,000 in 1980 to 86,000 in 2000 and then 120,000 in 2006 when the last Jewish population survey was undertaken. If Jewish population growth mirrored the general population growth, the Jewish population would have been 130,000 in 2016.

Whereas much of the Atlanta Jewish community has historically been deeply rooted families that prided in their Atlanta and Southern ties, the vast majority of the community today is made up of transplants, and almost a third of the community was born in New York. According to the 2006 population survey, Jews who have moved to the area in the last 10 years also outnumber those born in the area, particularly in the northern suburbs.

The number of community institutions and organizations has also increased to keep up with the needs of the community. Today there are 38 synagogues in the area – 33 founded after 1968, of which 24 were started between 1984 and 2006. The Orthodox portion of the community is also rapidly growing, and over half of these new congregations are Orthodox or traditional. This has been coupled with an increasing number of kosher restaurants and supermarket sections and the establishment of

Jewish community

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

continues to grow today. In its early decades, the Jewish community was largely made up of German Jewish

The history of the Jews in Germany goes back at least to the year 321 CE, and continued through the Early Middle Ages (5th to 10th centuries CE) and High Middle Ages (c. 1000–1299 CE) when Jewish immigrants founded the Ashkenazi Jewish commu ...

immigrants who quickly assimilated and were active in broader Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

society. As with the rest of Atlanta, the Jewish community was affected greatly by the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. In the late 19th century, a wave of Jewish migration from Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

brought less wealthy, Yiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

-speaking Jews to the area, in stark contrast to the established Jewish community. The community was deeply impacted by the Leo Frank

Leo Max Frank (April 17, 1884August 17, 1915) was an American lynching victim convicted in 1913 of the murder of 13-year-old Mary Phagan, an employee in a factory in Atlanta, Georgia, where he was the superintendent. Frank's trial, convicti ...

case in 1913–1915, which caused many to re-evaluate what it meant to be Jewish in Atlanta and the South, and largely scarred the generation of Jews in the city who lived through it.

In 1958, one of the centers of Jewish life in the city, the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation, known as The Temple, was bombed because of its rabbi's support for the Civil Rights Movement. Unlike decades prior when Leo Frank was lynched, the bombing spurred an outpouring of support from the broader Atlanta community.

In the last few decades, the community has steadily become one of the ten largest in the United States. As its population has risen, it has also become the Southern location of many national Jewish organizations, and today there are a multitude of Jewish institutions.

The greater Atlanta area is considered to be home to the country's ninth largest Jewish population.

19th and early 20th century

Early history

First founded as Marthasville in 1843, Atlanta changed its name in 1845, and that same year the first Jews settled there. The first two known Jewish settlers, Jacob Haas and Henry Levi, opened a store together in 1846. By 1850, 10% of Atlanta stores were run by Jews, who only made up 1% of the population and largely worked in retail, especially in the sale of clothing and dry goods. Many early Jewish settlers, however, did not end up settling permanently in Atlanta, and turnover in the community was high. In the 1850s, due to the transient nature of much of the Jewish community, there were no consistent religious services and no formally organized community. That changed in 1860s, after the founding of the Hebrew Benevolent Society, started as a burial society, which led to the creation of the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation in 1867. Early members of the society secured the first Jewish plots in the famous Oakland Cemetery, in its original six acres. The congregation, which came to be known as “The Temple”, has been an important focal point of Atlanta Jewish life since its synagogue was dedicated in 1877. During the Civil War, the Jewish community in the city were not all on the same side of the conflict. When the war was over and the city was left to rebuild after it had largely been burnt down whenGeneral Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a General officer, general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), earning recognit ...

and his troops approached the city, Jews played a larger role than before in the city's public sphere and its society. As the city became the center of the “New South”, its economy rapidly expanded, enticing a number of Jews to move to the city. According to one figure, in 1880, 71% of Jewish adult males in Atlanta worked in commercial trade, and 60% were either business owners or managers. The community was also very present in politics – two Jews from the Atlanta area were elected to the state legislature in the late 1860s and early 1870s, and in 1875 Aaron Haas was the city's mayor pro tem. Additionally, David Mayer helped found the Georgia Board of Education and served on it for a decade until his death in 1890.

Immigration & the establishment of congregations

Beginning in 1881, Atlanta received a portion of the influx of Jews immigrating to the U.S. from Eastern Europe, especially theRussian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

. While the existing Atlanta Jewish community was largely assimilated, generally wealthy, and of liberal German Jewish backgrounds, the new immigrants were of a different background. They were largely poor, spoke Yiddish, shunned the Reform Judaism

Reform Judaism, also known as Liberal Judaism or Progressive Judaism, is a major Jewish religious movements, Jewish denomination that emphasizes the evolving nature of Judaism, the superiority of its Jewish ethics, ethical aspects to its ceremo ...

of The Temple, and held Orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pag ...

views. By the early 20th century, these more recent immigrants outnumbered the German Jewish community of The Temple. In 1887, Congregation Ahavath Achim was founded to fit this new portion of the community, and in 1901 their synagogue was built in the middle of the south side area where most Yiddish-speaking Jews lived.

In this period, multiple synagogues opened only to rejoin Ahavath Achim or The Temple in the following years or next decades. In 1902, Congregation Shearith Israel, which did not flame out like other contemporary congregations, was formed by a group of Ahavath Achim members who were discontent with the level of stringency of observance there. In 1910, Shearith Israel hired Rabbi Tobias Geffen to head their synagogue, who would go on to have a large impact on the Atlanta Jewish community as well as Orthodox communities throughout the South.

In the early 20th century, about 150 Sephardi Jews

Sephardic Jews, also known as Sephardi Jews or Sephardim, and rarely as Iberian Peninsular Jews, are a Jewish diaspora population associated with the historic Jewish communities of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and their descendant ...

immigrated to the city, many of whom came from Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

and Rhodes

Rhodes (; ) is the largest of the Dodecanese islands of Greece and is their historical capital; it is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, ninth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Administratively, the island forms a separ ...

. A group in the Sephardi community founded their own synagogue, Ahavat Shalom, in 1910. In 1912, some Turkish Sephardi Jews broke off from the congregation and founded their own, Or Hahyim. Two years later, both congregations merged and became Or Ve Shalom, and their first synagogue building was dedicated in 1920.

In 1913, a small number of Hasidic Jews

Hasidism () or Hasidic Judaism is a religious movement within Judaism that arose in the 18th century as a spiritual revival movement in contemporary Western Ukraine before spreading rapidly throughout Eastern Europe. Today, most of those affi ...

also founded their own synagogue, Anshi S’fard.

Community organizations

The divisions between Yiddish speaking Jews and Jews of German backgrounds extended beyond the synagogues as well, and in many ways it was as though there were two separate Jewish communities. The perception of the German Jewish community was that the Yiddish Jews were of a lower class, possibly a threat to the carefully cultivated image of the Jewish community in the city, and needed to assimilate but also be kept separate. This dynamic also visible in the realm of Jewish communal organizations. German Jewish organizations such as the Hebrew Relief Society and the Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Society helped the poor in the community. Sometimes, however, attempts by the German Jewish community to aid the less well off Yiddish speaking community were perceived by the latter as patronizing or offensive. In one such instance, the local Jewish paper remarked, "we want to make good American citizens out of our Russian brothers" and called the Yiddish speaking immigrants "ignorant." When wealthy German Jews organized theStandard Club

The Standard Club is a private country club, founded as the Concordia Association in 1867. Originally located in Atlanta, Georgia, United States, the club is now located in the northern suburb of Johns Creek.

History

The club started as the C ...

and purchased a mansion for its clubhouse in 1905, Yiddish Jews were pretty much entirely excluded. In 1913, Yiddish Jews founded the Progressive Club. It was not until the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

that the Standard Club stopped discriminating on this basis, and by and large, it was not until World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

that the barriers between German and Yiddish Jews fell.

The Jewish Education Organization (JEA) is an example of cooperation between both groups of Jews. The result of merging a Russian immigrant organization and a German Jewish one, it had the goal of encouraging Americanization of immigrants; and hosted training classes and Hebrew instruction, served as a meeting place for Jewish clubs and organizations, and had recreation. The JEA facility was completed in 1911 and surplus funds were used to start a free health clinic in the building. Located in the center of Jewish Atlanta, through its variety of programs it served as both a community center and immigrant help center. It became a focal point for the Jewish community and during one month in 1914, more than 14,000 people attended programs there.

Other contemporary organizations included the Federation of Jewish Charities (est. 1905), later reorganized as the Jewish Federation

The Jewish Federation (JFED) is a secular Jewish non-profit organization found within many metropolitan areas across the United States with a significant Jewish community. They provide supportive and human services, philanthropy, financial grants ...

of Greater Atlanta, and the Hebrew Orphans' Home (est. 1889). The Federation was (and remains) the umbrella organization for funding the community's institutions and charitable programs, while the Hebrew Orphans' Home served nearly 400 children in the first 25 years, later transitioning toward aiding foster care and supporting widows, and ultimately closing in 1930.

Leo Frank trial

Leo Frank

Leo Max Frank (April 17, 1884August 17, 1915) was an American lynching victim convicted in 1913 of the murder of 13-year-old Mary Phagan, an employee in a factory in Atlanta, Georgia, where he was the superintendent. Frank's trial, convicti ...

was born in Texas, raised in New York, and moved to Atlanta to work at his uncle's pencil factory. He was active in the Atlanta Jewish community after his arrival, marrying Lucille Selig, of a prominent Atlanta Jewish family, and being elected head of the city's B’nai B’rith

B'nai B'rith International ( ; from ) is an American 501(c)(3) nonprofit Jewish service organization and was formerly a cultural association for German Jewish immigrants to the United States. B'nai B'rith states that it is committed to the secu ...

chapter. In 1913, 13-year-old pencil factory employee Mary Phagan, from Marietta was found murdered in the basement of the factory building. The case quickly became a major story in Atlanta, and the death brought tensions about child labor and the grievances of the rural working class to the fore, increasing pressure for someone to be held responsible. Over the course of the investigation, multiple suspects were arrested and released before police came to believe that Frank was likely the killer. The trial that followed sparked anti-Semitic fervor, and changed the outlook of the Atlanta Jewish community.

The main witness for the prosecution, James "Jim" Conley, was a black janitor who worked in the factory. Conley changed his story a number of times throughout the investigation and trial, but did not crack while being cross examined on the stand and was key in the trial's outcome. Most historians today believe that Conley was the killer, and he was a primary suspect before Frank. As to the atmosphere that led to Frank's prosecution, historian Nancy MacLean said it "ould Ould is an English surname as well as an element of many Arabic names. In Arabic contexts it is a transliteration of the word wikt:ولد, ولد, meaning "son".

Notable people with this surname include:

English surname

* Edward Ould (1852–190 ...

be explained only in light of the social tensions unleashed by the growth of industry and cities in the turn-of-the-century South. These circumstances made a Jewish employer a more fitting scapegoat for disgruntled whites than the other leading suspect in the case, a black worker." Meanwhile, Frank's trial received full coverage in Atlanta's three competing newspapers, and public outrage only continued to grow over the murder. Throughout the trial and in the media, Frank was painted as the antagonist of all that was good and Southern – an industrialist, a Northern Yankee, and a Jew.

In August 1913, after a short deliberation, the jury convicted Frank and he was sentenced to death. A large mob assembled outside the courthouse rejoiced at the news. The case was then appealed by his lawyers at every level, and it was during this time that Frank's plight became national news and galvanized the Jewish community across the country. Adolph Ochs

Adolph Simon Ochs (March 12, 1858 – April 8, 1935) was an American newspaper publisher and former owner of ''The New York Times'' and ''The Chattanooga Times'', which is now the ''Chattanooga Times Free Press''. Through his only child, Iphigene ...

, publisher of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' took up Frank's cause and launched what has been called a "journalistic crusade" in the paper. In addition, the head of the American Jewish Committee, Louis Marshall, threw his and the organization's weight behind the issue. This, however, fanned flames further for those in the South who already viewed Frank as a symbol of Northern and Jewish wealth and elitism. Populist politician Thomas E. Watson took to railing against Frank in his publications, The Jeffersonian and Watson's Magazine, often in racialized terms, and pronouncing his guilt and calling for his death. Frank's case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

, where the appeal was denied a final time. The focus then largely shifted onto progressive and popular Georgia Governor John Slaton

John Marshall Slaton (December 25, 1866 – January 11, 1955) served two non-consecutive terms as the 60th Governor of Georgia. His political career ended in 1915 after he commuted the death sentence of Atlanta factory boss Leo Frank, who had ...

, then in his last days in office, to commute the death sentence. Slaton found himself under immense pressure from those on both sides, and personally reviewed 10,000 pages of documents and revisited the factory where the murder occurred.

On June 21, 1915, Governor Slaton commuted Frank's sentence to life in prison. Much of the state, and Atlanta in particular, was outraged. A mob that formed with the aim of attacking the governor's home had to be stopped by the Georgia National Guard

The Georgia National Guard is the National Guard of the United States, National Guard of the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, and consists of the Georgia Army National Guard and the Georgia Air National Guard. (The Georgia State Defe ...

.

After being commuted, Frank was transferred to the prison in Milledgeville, over 100 miles from Marietta, Phagan's hometown. A month later, another inmate tried to kill Frank by slashing his throat, an attempt on his life which he survived.

On August 16, 1915, a group of prominent Marietta and Georgia citizens calling themselves the "Knights of Mary Phagan", including a former Georgia governor, former and current Marietta mayors, and current and former sheriffs, abducted Frank from prison and drove him back to Marietta. There, they hanged him not far from the Phagan house, where his body remained for hours as an energized crowd gathered.

In the months following the lynching, some of the Knights of Mary Phagan also helped to revive the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

atop Stone Mountain

Stone Mountain is a quartz monzonite dome Inselberg, monadnock and the site of Stone Mountain Park, east of Atlanta, Georgia. Outside the park is the city of Stone Mountain, Georgia. The park is the most visited tourist site in the state of Ge ...

. The Anti-Defamation League (ADL)’s creation in 1913 was also spurred by the Frank trial. The case has been called the "American Dreyfus affair", as both centered around falsely accused wealthy assimilated Jewish men whose trials, based on minimal evidence, were the catalysts of anti-Semitic fervor in the masses which then led to their convictions.

Leo Frank's lynching had a massive impact on the Atlanta Jewish community, and in many ways still does today. The episode was also widely felt in Jewish communities across the United States, and even more so in the South. Prior to his case, many Atlanta Jews of a wealthier, German background felt fully established and accepted in the city. They were assimilated and considered themselves Southern, and what happened to Frank was a scary awakening that in the broader society's eyes, they may always be considered Jews first. Leo and his wife Lucille were members of The Temple and its community, and Lucille, to the shock of many, remained in Atlanta the rest of her life. The consensus of the community following Frank's death was not to mention it, and the subject remained taboo for many decades.

Even over 100 years later, the subject remains a touchy one for some, and how important what happened to Leo Frank is in the broader history of the Jewish community in Atlanta is still an open question. There are many who see it a blip in the distinguished history of the community, and prefer to think of it as an anomaly with little bearing on the whole. Others in the community assign more lasting importance to what happened, and continue to call for political action to absolve and remember Frank, who in 1986 received a posthumous pardon based on the state's culpability in his death, rather than his innocence.

Mid–late 20th century

Some Jews left Atlanta in the aftermath of Leo Frank's trial and lynching, but the number is unknown. The community also largely withdrew from politics after the episode, and for well over a decade, no Atlanta Jews ran for public office. Nevertheless, the Jewish population continued to grow in the decades following, going from 4,000 in 1910 to 12,000 in 1937, and accounting for a third of the city's foreign-born population in 1920. Starting in the 1920s, there was a significant migration of the Jewish population to the north of the city from the poorer areas, like Hunter Street. It was not only the historically wealthier German Jewish community that moved, but many poorer Jews whose primary language was Yiddish, migrated there also. As the north became the clear center of the Jewish population in the city, the synagogues moved there as well. By 1945, two-thirds of the city's Jews lived in the northeast, and many of those who did not would later move there. WhileZionism

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

was gaining traction in Jewish communities around the world and U.S., it was slower to catch on in Atlanta. This was partially due to Rabbi David Marx's staunch anti-Zionist

Anti-Zionism is opposition to Zionism. Although anti-Zionism is a heterogeneous phenomenon, all its proponents agree that the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, and the movement to create a sovereign Jewish state in the Palestine (region) ...

views and which were influential due to his leadership of The Temple. It was not until the 1920s that support for Zionism began to grow in the community, although there were a few small, frequently inactive Zionist organizations that started years prior. A gathering celebrating the Allies of World War I

The Allies or the Entente (, ) was an international military coalition of countries led by the French Republic, the United Kingdom, the Russian Empire, the United States, the Kingdom of Italy, and the Empire of Japan against the Central Powers ...

’s support for a “Jewish national home” in Palestine at the San Remo conference

The San Remo conference was an international meeting of the post-World War I Allied Supreme Council as an outgrowth of the Paris Peace Conference, held at Castle Devachan in Sanremo, Italy, from 19 to 26 April 1920. The San Remo Resolution ...

amassed over 2,000 people in 1920. A Hadassah chapter was established in 1916, and had 300 members by 1937.

Prominent rabbis

Between the turn of the century and the late 1920s the main three synagogues came under steady leadership, and each of their rabbis went on to stay in the position for decades. Rabbi David Marx served The Temple for 51 years (1895–1946), Rabbi Tobias Geffen served Shearith Israel for 60 years (1910–1970), and Rabbi Harry Epstein served Ahavath Achim for 54 years (1928–1982). Over their distinguished tenures, they each had a large impact on the face of the Jewish community and its values. Rabbi Marx was very active in bridge-building with the larger non-Jewish/Christian community in Atlanta, and was largely seen by non-Jews in the city as being the representative of the Jewish community at large. This idea, however, was problematic as Rabbi Marx held very liberal Reform views, and was primarily representative only of the smaller but established and influential German Jewish community. Rabbi Marx also lead the congregation's shift intoclassical Reform Judaism

Reform Judaism, also known as Liberal Judaism or Progressive Judaism, is a major Jewish denomination that emphasizes the evolving nature of Judaism, the superiority of its ethical aspects to its ceremonial ones, and belief in a continuous rev ...

after years of internal ideological squabbles in the congregation which had eventually resulted in his hiring in 1895. He also was a staunch anti-Zionist, due to his desire for Jews to assimilate in the U.S., and was key in the passage of his congregations' 1897 anti-Zionist resolution and feeling. Under his leadership, the congregation significantly grew in size and moved to a new location in the north of the city.

mikveh

A mikveh or mikvah (, ''mikva'ot'', ''mikvot'', or (Ashkenazi Hebrew, Ashkenazic) ''mikves'', lit., "a collection") is a bath used for ritual washing in Judaism#Full-body immersion, ritual immersion in Judaism to achieve Tumah and taharah, ...

, and the level of kashrut

(also or , ) is a set of Food and drink prohibitions, dietary laws dealing with the foods that Jewish people are permitted to eat and how those foods must be prepared according to halakha, Jewish law. Food that may be consumed is deemed ko ...

. Within a few years, he became known as a key resource for many of the Orthodox communities throughout the South that lacked a rabbi of their own, and often travelled to solve problems. Rabbi Geffen is best known for first certifying Coca-Cola

Coca-Cola, or Coke, is a cola soft drink manufactured by the Coca-Cola Company. In 2013, Coke products were sold in over 200 countries and territories worldwide, with consumers drinking more than 1.8 billion company beverage servings ...

as kosher, and kosher for Passover

Passover, also called Pesach (; ), is a major Jewish holidays, Jewish holiday and one of the Three Pilgrimage Festivals. It celebrates the Exodus of the Israelites from slavery in Biblical Egypt, Egypt.

According to the Book of Exodus, God in ...

. As the prominent Orthodox rabbi in the region, he began receiving letters from across the country asking whether or not Coca-Cola, famously based in Atlanta, was kosher. The soda was seen as a symbol of American identity and, thus, belonging, by the younger generation who were especially eager to partake. Rabbi Geffen sought permission to view Coca-Cola's closely guarded secret formula in order to assess whether it could be deemed kosher, and was eventually granted it after being sworn to secrecy. In his halachic responsa, using initials and code words to refer to ingredients, he outlined two problem ingredients, one which kept the soda from being kosher altogether and another which precluded it from being kosher for Passover. After his responsa, the company started research to solve the issues, and did so successfully. In 1935, Rabbi Geffen issued a new responsa deeming Coca-Cola kosher, and also kosher for Passover as they had agreed to switch to using beet and cane sugar in the weeks before the holiday.

Rabbi Harry Epstein, too, was born in Lithuania and immigrated to the U.S. at the beginning of the 20th century. He was ordained by some of the most prominent rabbis of the time, and his father was an influential and long-serving Orthodox rabbi in Chicago. Despite this, he would lead his congregation, Ahavath Achim, to transition from Orthodox to Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

. When he took over leading the synagogue, it was in a time when its membership and community had a growing fracture between its older, founding, Yiddish-speaking immigrants and the less traditional English-speaking next generation. Rabbi Epstein gave sermons and taught classes in both English and Yiddish, and helped revitalize the community in his first years. Gradually, changes were implemented in the synagogue, such as the women's section, which went from being in the balcony to part of the sanctuary floor, and eventually was eliminated in favor of mixed gender seating. The opportunities for women's overall participation increased also. Bat mitzvah

A ''bar mitzvah'' () or ''bat mitzvah'' () is a coming of age ritual in Judaism. According to Jewish law, before children reach a certain age, the parents are responsible for their child's actions. Once Jewish children reach that age, they a ...

celebrations for girls took place for the first time, although they were still prohibited from reading from the Torah

The Torah ( , "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The Torah is also known as the Pentateuch () ...

, and women joined the synagogue choir. Rabbi Epstein's move towards the Conservative movement was influenced by what he perceived as a rightward shift in the U.S. Orthodox community after World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, that he felt shut the door on progress in the Orthodox world. The congregation official became Conservative in 1954, and its slow slide into the Conservative movement had also lead to the founding of Congregation Beth Jacob in 1943.

1958 bombing of The Temple

Under the 51-year tenure of Rabbi David Marx, the members of The Temple were used to the idea that if it wanted acceptance, it could not afford to rock the boat in non-Jewish/Christian Atlanta society or cause conflict. The congregation's next rabbi, Jacob Rothschild, however, took a different attitude and felt that advocating against segregation and discrimination were moral imperatives, controversial or not. Many believe that Rabbi Rothschild's outspoken support for the Civil Rights Movement and integration lead to the targeting of The Temple.

In the first hours of October 12, 1958, The Temple was bombed using 50 sticks of dynamite, causing significant damage but no injuries. Not long after the explosion,

Under the 51-year tenure of Rabbi David Marx, the members of The Temple were used to the idea that if it wanted acceptance, it could not afford to rock the boat in non-Jewish/Christian Atlanta society or cause conflict. The congregation's next rabbi, Jacob Rothschild, however, took a different attitude and felt that advocating against segregation and discrimination were moral imperatives, controversial or not. Many believe that Rabbi Rothschild's outspoken support for the Civil Rights Movement and integration lead to the targeting of The Temple.

In the first hours of October 12, 1958, The Temple was bombed using 50 sticks of dynamite, causing significant damage but no injuries. Not long after the explosion, United Press International

United Press International (UPI) is an American international news agency whose newswires, photo, news film, and audio services provided news material to thousands of newspapers, magazines, radio and television stations for most of the 20th ce ...

(UPI) staff received a call from “General Gordon of the Confederate Underground”, a white supremacist

White supremacy is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White supremacy has roots in the now-discredited doctrine ...

group saying they carried out the bombing, that it would be the last empty building they bomb, and Jews and African Americans were aliens

Alien primarily refers to:

* Alien (law), a person in a country who is not a national of that country

** Enemy alien, the above in times of war

* Extraterrestrial life, life which does not originate from Earth

** Specifically, a lifeform with ext ...

in the U.S.

The damage to the synagogue was estimated at $100,000, or roughly $868,000 today adjusted for inflation. Donations to help the synagogue recover poured in from every corner of Atlanta and from across the country, although the synagogue had not requested funds. The editor of the ''Atlanta Constitution'' newspaper, Ralph McGill

Ralph Emerson McGill (February 5, 1898 – February 3, 1969) was an American journalist and editorialist. An anti-segregationist editor, he published the ''Atlanta Constitution'' newspaper. He was a member of the Peabody Awards Board of Ju ...

, wrote a powerful editorial in the paper denouncing the bombing and any tolerance for hatred in the city, for which he won a Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

.

The government was also quick to respond. Atlanta's mayor, William B. Hartsfield, visited the site of the bombing and condemned it in no uncertain terms. President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

also decried the attack, and promised the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

’s support in the investigation. Several dozen policemen, as well as Georgia Bureau of Investigation

The Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI) is the state bureau of investigation of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is an independent, statewide agency that provides assistance to Georgia's criminal justice system in the areas of criminal investi ...

and FBI agents, worked to solve the case. While five people were arrested, and one tried, no one was ever convicted of the crime.

Ironically, in some respects the bombing revealed to the community the privilege that they had. The sweeping outpouring of support and sympathy from the broader Atlanta society, and the swift action taken by officials, showed that they could feel secure now, decades after what happened to Leo Frank. This also made some in the community newly emboldened to speak up against segregation and for civil rights, with the feeling that they could afford to. Synagogue members also more heartily supported Rabbi Rothschild’s actions and sermons on civil rights issues afterwards, and the first sermon he gave following the bombing was called “And None Shall Make Them Afraid”.

At the same time, for many in the African American community, the public and official reactions to the bombing were deeply frustrating, as such terror was inflicted on them more frequently and without support or effective investigations. Responding to Ralph McGill's piece about the bombing, the daughter of slain Florida NAACP director Henry T. Moore lamented the lack of similar outcry or care on the part of the government at the state or federal levels in investigating the crime.

1950s – end of the 20th century

Just after World War II, an estimated 10,217 Jews were living in Atlanta, and only 6% of Jewish adults were not involved in any Jewish organizations. In the 1950s, Atlanta further solidified its status as the Jewish center of the South with the opening of branches of a number Jewish groups, including the Anti-Defamation League and theAmerican Jewish Committee

The American Jewish Committee (AJC) is a civil rights group and Jewish advocacy group established on November 11, 1906. It is one of the oldest Jewish advocacy organizations and, according to ''The New York Times'', is "widely regarded as the wi ...

.

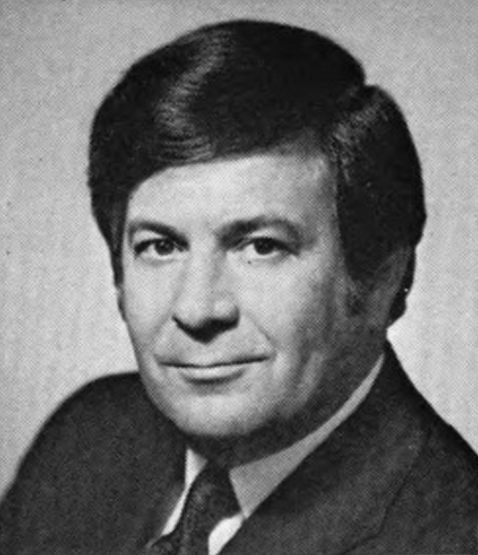

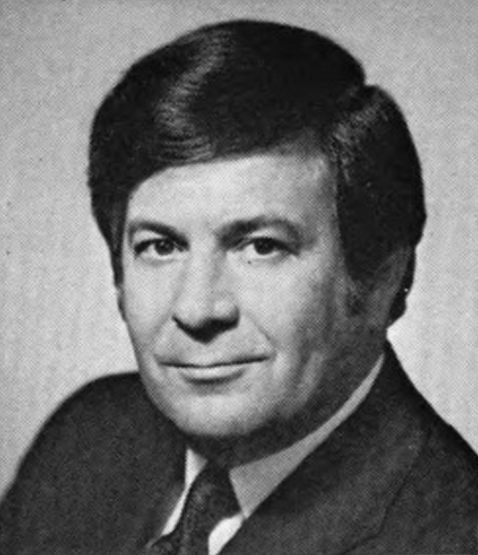

In the decades following The Temple bombing, the Jewish community also became active in politics again. In 1961, Sam Massell was elected Vice Mayor of the city, and then re-elected in 1965. In 1969, he was elected the first Jewish mayor the city, after winning the vast majority of the African American vote and losing the vast majority of the white vote. A part of his campaign pitch to the African American community was that his experience being Jewish, while not equivalent to the black experience, gave him a better understanding than other white people of the challenges community was facing. He was defeated by

In the decades following The Temple bombing, the Jewish community also became active in politics again. In 1961, Sam Massell was elected Vice Mayor of the city, and then re-elected in 1965. In 1969, he was elected the first Jewish mayor the city, after winning the vast majority of the African American vote and losing the vast majority of the white vote. A part of his campaign pitch to the African American community was that his experience being Jewish, while not equivalent to the black experience, gave him a better understanding than other white people of the challenges community was facing. He was defeated by Maynard Jackson

Maynard Holbrook Jackson Jr. (March 23, 1938 – June 23, 2003) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 52nd mayor of Atlanta, Georgia, from 1974 to 1982, and again as the city's 54th mayor from 1990 to 1994. A member of the ...

during his 1973 re-election bid, who became Atlanta's first black mayor, and Massell is the last white mayor of Atlanta to date.

During and in a short period following the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War, also known as the June War, 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states, primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan from 5 to 10June ...

, the 16,000 person Atlanta Jewish community managed to raise $1.5 million, which today would be over $11 million adjusted for inflation, for the United Jewish Appeal

The Jewish Federations of North America (JFNA), formerly the United Jewish Communities (UJC), is an American Jewish umbrella organization for the Jewish Federations system, representing over 350 independent Jewish communities across North Ameri ...

's Israel Emergency Fund.

In 1980, the Jewish population was estimated at 27,500. The community also continued its move northward and to the suburbs, and by 1984, 70% of the area's Jews were living outside of the Atlanta city limits.

From 1975 to 1985, Elliott H. Levitas

Elliott Harris Levitas (December 26, 1930 – December 16, 2022) was an American politician and lawyer from Georgia. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as a member of the United States House of Representatives for five consecutive term ...

represented Georgia's 4th congressional district

Georgia's 4th congressional district is a congressional district in the U.S. state of Georgia. The district is currently represented by Democrat Hank Johnson, though the district's boundaries have been redrawn following the 2010 census, whi ...

. When Jimmy Carter, who had been Governor of Georgia

The governor of Georgia is the head of government of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and the commander-in-chief of the state's Georgia National Guard, National Guard, when not in federal service, and Georgia State Defense Force, State Defense Fo ...

, was elected President in 1976 several Atlanta Jews such as Stuart E. Eizenstat

Stuart Elliott Eizenstat (born January 15, 1943) is an American diplomat and attorney. He served as the United States Ambassador to the European Union from 1993 to 1996 and as the United States Deputy Secretary of the Treasury from 1999 to 2001. ...

and Robert Lipshutz moved to Washington with him to work in the administration.

When Atlanta hosted the 1996 Summer Olympics

The 1996 Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the XXVI Olympiad, also known as Atlanta 1996 and commonly referred to as the Centennial Olympic Games) were an international multi-sport event held from July 19 to August 4, 1996, in Atlanta, ...

, the Jewish community took action to encourage formal recognition and remembrance of the 11 members of the Israeli Olympic team murdered by a Palestinian terrorist group during the 1972 Summer Olympics

The 1972 Summer Olympics (), officially known as the Games of the XX Olympiad () and officially branded as Munich 1972 (; ), were an international multi-sport event held in Munich, West Germany, from 26 August to 11 September 1972. It was the ...

, known as the Munich massacre. When it became clear the International Olympic Committee

The International Olympic Committee (IOC; , CIO) is the international, non-governmental, sports governing body of the modern Olympic Games. Founded in 1894 by Pierre de Coubertin and Demetrios Vikelas, it is based i ...

(IOC) was not going to have any commemoration or give a mention, the Atlanta Jewish community, largely through the Jewish Federation of Greater Atlanta, organized their own ceremony with the families of the Israelis who were killed.

Modern community

The Atlanta Jewish community has seen dramatic population boom and demographic change in the last few decades, while Atlanta's overall population has also reached new heights as one of the fastest-growing cities in the U.S. The Jewish community in the metropolitan area went from less than 30,000 in 1980 to 86,000 in 2000 and then 120,000 in 2006 when the last Jewish population survey was undertaken. If Jewish population growth mirrored the general population growth, the Jewish population would have been 130,000 in 2016.

Whereas much of the Atlanta Jewish community has historically been deeply rooted families that prided in their Atlanta and Southern ties, the vast majority of the community today is made up of transplants, and almost a third of the community was born in New York. According to the 2006 population survey, Jews who have moved to the area in the last 10 years also outnumber those born in the area, particularly in the northern suburbs.

The number of community institutions and organizations has also increased to keep up with the needs of the community. Today there are 38 synagogues in the area – 33 founded after 1968, of which 24 were started between 1984 and 2006. The Orthodox portion of the community is also rapidly growing, and over half of these new congregations are Orthodox or traditional. This has been coupled with an increasing number of kosher restaurants and supermarket sections and the establishment of

The Atlanta Jewish community has seen dramatic population boom and demographic change in the last few decades, while Atlanta's overall population has also reached new heights as one of the fastest-growing cities in the U.S. The Jewish community in the metropolitan area went from less than 30,000 in 1980 to 86,000 in 2000 and then 120,000 in 2006 when the last Jewish population survey was undertaken. If Jewish population growth mirrored the general population growth, the Jewish population would have been 130,000 in 2016.

Whereas much of the Atlanta Jewish community has historically been deeply rooted families that prided in their Atlanta and Southern ties, the vast majority of the community today is made up of transplants, and almost a third of the community was born in New York. According to the 2006 population survey, Jews who have moved to the area in the last 10 years also outnumber those born in the area, particularly in the northern suburbs.

The number of community institutions and organizations has also increased to keep up with the needs of the community. Today there are 38 synagogues in the area – 33 founded after 1968, of which 24 were started between 1984 and 2006. The Orthodox portion of the community is also rapidly growing, and over half of these new congregations are Orthodox or traditional. This has been coupled with an increasing number of kosher restaurants and supermarket sections and the establishment of eruv

An ''eruv'' (; , , also transliterated as ''eiruv'' or ''erub'', plural: ''eruvin'' or ''eruvim'') is a ritual ''halakhic'' enclosure made for the purpose of allowing activities which are normally Activities prohibited on Shabbat, prohibited ...

im in several northern suburbs. Additionally, five congregations have their own mikveh and there are a number of Jewish day schools across the ideological spectrum. Despite this, the community is one of less religiously affiliated in the U.S., as the vast majority of Jewish families do not belong to a synagogue.

While Ashkenazi Jews make up the majority of the community, as is common in most of the country, Atlanta is also home to one of the U.S.'s largest Sephardi populations.

William Breman Jewish Heritage & Holocaust Museum

The William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum, colloquially known as The Breman, is a cultural center in Atlanta dedicated to Jewish history, culture and arts with special emphasis on Georgia and the Holocaust. The Breman, which opened in 1996, is th ...

, opened in 1985, has a large archive of and exhibits Atlanta's Jewish history, as well as educating about the Holocaust. There are also Holocaust memorials in Greenwood Cemetery and at the Marcus JCC's Zaban Park. The Marcus JCC is named in honor of Bernie Marcus

Bernard Marcus (May 12, 1929 – November 4, 2024) was an American billionaire businessman. He co-founded Home Depot in 1978. He was the company's first CEO and first chairman until retiring in 2002. In November 2024, ''Forbes'' estimated his ne ...

, who along with Arthur Blank

Arthur Morris Blank (born September 27, 1942) is an American Businessperson, businessman. He is best known for being a co-founder of the home improvement retailer Home Depot, The Home Depot.

Blank owns three professional sports teams based in At ...

founded Home Depot

The Home Depot, Inc., often referred to as Home Depot, is an American multinational corporation, multinational home improvement retail corporation that sells tools, construction products, appliances, and services, including fuel and transportat ...

, and both of whom are major donors in the Jewish community in Atlanta and beyond.

The ''Atlanta Jewish Times

The ''Atlanta Jewish Times'' (AJT) is a weekly community newspaper serving the Jewish community of Atlanta, Georgia, United States. Its owner and publisher is Michael Morris.

History

The newspaper began publishing as the ''Southern Israelite'' ...

'', formerly the Southern Israelite, provides Jewish news for the city and the Southeast.

Education

Jewish schools include: *Atlanta Jewish Academy

Atlanta Jewish Academy was created by the merger of Greenfield Hebrew Academy and Yeshiva Atlanta on July 1, 2014.

The school is the first Infant through 12th grade Jewish day school in Greater Atlanta. It previously had two campuses, the lowe ...

* The Epstein School

The Epstein School is an Independent school, independent Jewish day school located in Sandy Springs, Georgia, United States. It enrolls children from 18 months through eighth grade. The principal (education), Head of School is Dr. David Abusch-M ...

* The Weber School

The Felicia Penzell Weber Jewish Community High School, often referred to as The Weber School, is a coeducational and pluralistic Jewish community high school located in Sandy Springs, Georgia, United States. Weber has approximately 350 student ...

; Former

* Greenfield Hebrew Academy

* Yeshiva Atlanta

Yeshiva Atlanta (YA) was the first Jewish secondary school in Metro Atlanta, Georgia. It was established on August 28, 1970, and it ran until July 1, 2014, when it was merged with Greenfield Hebrew Academy primary school to form the Atlanta Jew ...

References

{{AtlantaAtlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...