History Of ESPCI Paris on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the ''École supérieure de physique et de chimie industrielles de la ville de Paris'' (ESPCI ParisTech) began in 1882, driven by concerns among French chemical industry leaders about France's lag behind

The French higher education system, disconnected from cutting-edge research, failed to meet the needs of emerging industries like chemistry and electricity, which required skilled engineers and technicians. While faculties provided outdated academic knowledge, grandes écoles adhered to a model suited to the

The French higher education system, disconnected from cutting-edge research, failed to meet the needs of emerging industries like chemistry and electricity, which required skilled engineers and technicians. While faculties provided outdated academic knowledge, grandes écoles adhered to a model suited to the

Prominent scientists like

Prominent scientists like

This group promoted the German model, credited for the success of the world’s leading chemical industry at the time, through the AFAS, which Wurtz and Friedel helped found. The AFAS’s annual congresses, held in different cities, effectively disseminated their ideas. For Lauth and his colleagues, Germany’s industrial success stemmed from strong ties between businesses, research, and education. Germany boasted a robust network of autonomous, well-funded universities offering high-level, accessible education. Professors were numerous, well-compensated, and respected, and applied sciences were embraced. Additionally, Germany’s technical schools, nearly all equipped with chemistry laboratories by 1892, trained the engineers the industry needed. The German system’s effectiveness was proven by

This group promoted the German model, credited for the success of the world’s leading chemical industry at the time, through the AFAS, which Wurtz and Friedel helped found. The AFAS’s annual congresses, held in different cities, effectively disseminated their ideas. For Lauth and his colleagues, Germany’s industrial success stemmed from strong ties between businesses, research, and education. Germany boasted a robust network of autonomous, well-funded universities offering high-level, accessible education. Professors were numerous, well-compensated, and respected, and applied sciences were embraced. Additionally, Germany’s technical schools, nearly all equipped with chemistry laboratories by 1892, trained the engineers the industry needed. The German system’s effectiveness was proven by

Lauth’s proposed curriculum spanned three years, combining theoretical lectures with practical laboratory work. The first year would cover qualitative and quantitative mineral analysis and basic preparations, with lectures on inorganic and organic chemistry. The second year would focus on organic analysis, industrial analyses, and complex preparations, with lectures on major chemical industries. The third year would train students to solve industrial problems through methodical projects, with lectures highlighting the latest scientific and industrial advancements. Graduates would earn a special “chemical engineer” diploma after an examination or competition. This approach, supported by figures like

Lauth’s proposed curriculum spanned three years, combining theoretical lectures with practical laboratory work. The first year would cover qualitative and quantitative mineral analysis and basic preparations, with lectures on inorganic and organic chemistry. The second year would focus on organic analysis, industrial analyses, and complex preparations, with lectures on major chemical industries. The third year would train students to solve industrial problems through methodical projects, with lectures highlighting the latest scientific and industrial advancements. Graduates would earn a special “chemical engineer” diploma after an examination or competition. This approach, supported by figures like

Undeterred, Lauth turned to the

Undeterred, Lauth turned to the

Despite the Alsatian network’s influence, the EMPCI diverged from Lauth’s original vision. Lauth criticized Parisian laboratories as inadequate for students seeking to learn, lacking proper guidance to translate scientific discoveries into practical outcomes or spark new industries. His proposed third-year curriculum aimed to train students in solving industrial problems while keeping them updated on scientific and industrial advancements. However, the EMPCI’s early curriculum prioritized technology over pure science, omitting the latest scientific developments, particularly in the third year, which focused on industrial accounting and economic discussions.

Research, even applied, was absent from the curriculum, with no time allocated for it. Regulations discouraged personal research by preparators, requiring them to dedicate their time to supervising students in laboratories, where third-year students spent most of their day. Despite this, exceptions were made, notably allowing

Despite the Alsatian network’s influence, the EMPCI diverged from Lauth’s original vision. Lauth criticized Parisian laboratories as inadequate for students seeking to learn, lacking proper guidance to translate scientific discoveries into practical outcomes or spark new industries. His proposed third-year curriculum aimed to train students in solving industrial problems while keeping them updated on scientific and industrial advancements. However, the EMPCI’s early curriculum prioritized technology over pure science, omitting the latest scientific developments, particularly in the third year, which focused on industrial accounting and economic discussions.

Research, even applied, was absent from the curriculum, with no time allocated for it. Regulations discouraged personal research by preparators, requiring them to dedicate their time to supervising students in laboratories, where third-year students spent most of their day. Despite this, exceptions were made, notably allowing

The early directors sought to balance the school’s industrial mission with scientific research, though this was challenging. On November 5, 1906, Haller proposed hosting foreign researchers to enhance the school’s reputation, citing the international renown of its faculty. Lauth, then a board member, opposed this, arguing that the school’s industrial focus should not shift toward pure science, as hosting foreign researchers could compromise its purpose.

Schützenberger also championed fundamental research.

The early directors sought to balance the school’s industrial mission with scientific research, though this was challenging. On November 5, 1906, Haller proposed hosting foreign researchers to enhance the school’s reputation, citing the international renown of its faculty. Lauth, then a board member, opposed this, arguing that the school’s industrial focus should not shift toward pure science, as hosting foreign researchers could compromise its purpose.

Schützenberger also championed fundamental research.

It was not until the early 1930s, under the leadership of

It was not until the early 1930s, under the leadership of

Langevin and his successors rejected any strict divide between pure and applied science. Langevin argued that scientists must connect with society’s needs through engineers and technicians, stating: “The scientist can no longer remain isolated but must be linked to the farmer and the worker, increasingly educated, through a continuous chain of intermediaries and interpreters represented by engineers and technicians at various levels of expertise and roles. The need has become clear to ensure this connection by creating institutions to train individuals not only informed about established science but, above all, immersed in its methods, understanding through direct and sustained experimentation and rigorous laboratory training how science is created, its provisional and living nature, and the degree of confidence its results warrant, too often taught dogmatically, definitively, and lifelessly.” This ethos was deepened by successors like

Langevin and his successors rejected any strict divide between pure and applied science. Langevin argued that scientists must connect with society’s needs through engineers and technicians, stating: “The scientist can no longer remain isolated but must be linked to the farmer and the worker, increasingly educated, through a continuous chain of intermediaries and interpreters represented by engineers and technicians at various levels of expertise and roles. The need has become clear to ensure this connection by creating institutions to train individuals not only informed about established science but, above all, immersed in its methods, understanding through direct and sustained experimentation and rigorous laboratory training how science is created, its provisional and living nature, and the degree of confidence its results warrant, too often taught dogmatically, definitively, and lifelessly.” This ethos was deepened by successors like

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, particularly after the annexation of Mulhouse

Mulhouse (; ; Alsatian language, Alsatian: ''Mìlhüsa'' ; , meaning "Mill (grinding), mill house") is a France, French city of the European Collectivity of Alsace (Haut-Rhin department, in the Grand Est region of France). It is near the Fran ...

following the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

of 1870. Founded as the ''École Municipale de Physique et de Chimie Industrielles'' (EMPCI), later becoming ESPCI, the institution emerged during a period of weakness in French science, largely due to an underdeveloped university system. To counter Germany's economic and industrial strength, particularly in its chemical industry

The chemical industry comprises the companies and other organizations that develop and produce industrial, specialty and other chemicals. Central to the modern world economy, the chemical industry converts raw materials ( oil, natural gas, air, ...

, Alsatian scientists drew inspiration from the German model of integrating higher education and research with industry, exemplified by the laboratories of Justus von Liebig

Justus ''Freiherr'' von Liebig (12 May 1803 – 18 April 1873) was a Germans, German scientist who made major contributions to the theory, practice, and pedagogy of chemistry, as well as to agricultural and biology, biological chemistry; he is ...

.

The history of ESPCI reflects the close interplay between science and industry in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, followed by a shift toward pure science

Basic research, also called pure research, fundamental research, basic science, or pure science, is a type of scientific research with the aim of improving scientific Theory, theories for better understanding and Prediction#Science, prediction o ...

in the 20th century, free from immediate economic demands. The institution’s evolution can be divided into two phases: an initial focus on industrial and economic needs, followed by a pivot toward fundamental research. Nonetheless, ESPCI has maintained a strong tradition of industry engagement. As Pierre-Gilles de Gennes

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes (; 24 October 1932 – 18 May 2007) was a French physicist and the Nobel Prize laureate in physics in 1991.

Education and early life

He was born in Paris, France, and was home-schooled to the age of 12. By the age of ...

and his successors emphasized, the school strives to blend cutting-edge fundamental research with practical applications.

ESPCI has been home to notable French scientists, including several Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

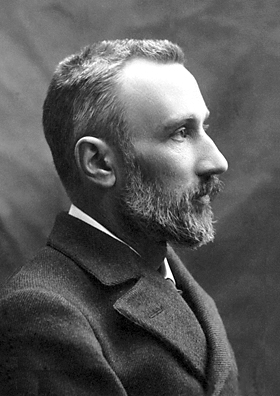

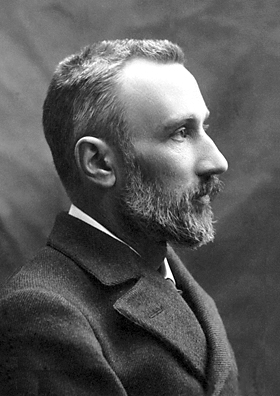

laureates: Pierre Curie

Pierre Curie ( ; ; 15 May 1859 – 19 April 1906) was a French physicist, Radiochemistry, radiochemist, and a pioneer in crystallography, magnetism, piezoelectricity, and radioactivity. He shared the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics with his wife, ...

, Marie Curie

Maria Salomea Skłodowska-Curie (; ; 7 November 1867 – 4 July 1934), known simply as Marie Curie ( ; ), was a Polish and naturalised-French physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity.

She was List of female ...

, Pierre-Gilles de Gennes

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes (; 24 October 1932 – 18 May 2007) was a French physicist and the Nobel Prize laureate in physics in 1991.

Education and early life

He was born in Paris, France, and was home-schooled to the age of 12. By the age of ...

, and Georges Charpak

Georges Charpak (; born Jerzy Charpak; 1 August 1924 – 29 September 2010) was a Polish-born French physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1992 for his invention of the multiwire proportional chamber.

Life

Georges Charpak was born ...

. Its history sheds light on the context of major discoveries, such as the Curies' discovery of radium

Radium is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Ra and atomic number 88. It is the sixth element in alkaline earth metal, group 2 of the periodic table, also known as the alkaline earth metals. Pure radium is silvery-white, ...

, and challenges the notion of a stark divide between science and industry.

Historical context of the establishment

Institutional context

The establishment of ESPCI was part of a broader effort to structure French higher education in the 19th century, initiated during the revolutionary period with the abolition of universities by theNational Convention

The National Convention () was the constituent assembly of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for its first three years during the French Revolution, following the two-year National Constituent Assembly and the ...

, and the creation of institutions like the ''Conservatoire national des arts et métiers'' (CNAM), ''École Polytechnique'', and ''École normale supérieure''. Located initially at ''42 rue Lhomond

The Rue Lhomond is a street in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France. It is located in the quartier du Val-de-Grâce and has existed since the 15th century.

Origin of the name

It was once known as the ''Rue des Poteries'' after its Gallo-R ...

'', ESPCI was founded to address the chemical industry’s needs, which the shortcomings of the 1870s French higher education system failed to meet. This gap threatened France’s economic development amid Europe’s race toward industrialization, particularly in competition with Germany.

French higher education in the 19th century was distinct from its European counterparts due to its dual structure: relatively inactive university faculties until 1870, and specialized institutions like the grandes écoles Grandes may refer to:

*Agustín Muñoz Grandes, Spanish general and politician

* Banksia ser. Grandes, a series of plant species native to Australia

* Grandes y San Martín, a municipality located in the province of Ávila, Castile and León, Spain ...

and research bodies such as the ''Collège de France'' and French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

. As historian Antoine Prost

Antoine Marie François Prost (29 October 1933) is a French historian who served as Professor Emeritus of History, University of Paris Panthéon-Sorbonne. He specialises in 20th-century French history, in particular the First World War.

Early ...

notes, true scientific education was provided at institutions like ''École Polytechnique'', the ''Muséum national d'histoire naturelle'', or the ''Collège de France'', rather than in university faculties. These faculties, established by an 1808 decree, primarily focused on administering the baccalauréat

The ''baccalauréat'' (; ), often known in France colloquially as the ''bac'', is a French national academic qualification that students can obtain at the completion of their secondary education (at the end of the ''lycée'') by meeting certain ...

, with little emphasis on research.

Scientific and technical education was delivered through a diverse array of grandes écoles, some predating the French Revolution, such as the ''École nationale des ponts et chaussées'' (1747) and the ''École des Mines

École or Ecole may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* Éco ...

'' (1783). Post-1789 institutions included ''École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr'' (1802), ''École centrale Paris

École or Ecole may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by Secondary education in France, secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing i ...

'' (1829), and various ''Écoles nationales supérieures d'arts et métiers''. The core of French scientific training, however, rested with ''École Polytechnique'' and ''École normale supérieure'', both founded in 1794.

Under Charles Dupin

Baron Pierre Charles François Dupin (; 6 October 1784, Varzy, Nièvre – 18 January 1873, Paris, France) was a French Catholic mathematician, engineer, economist and politician, particularly known for work in the field of mathematics, where t ...

’s influence, the CNAM offered free public education in applied sciences, including mechanics, chemistry for industrial applications, and industrial economics, as mandated by an 1819 ordinance. In industrial regions like Amiens, Lille, Lyon, Mulhouse, and Rouen, learned societies provided evening courses in mechanics and industrial chemistry, led by figures like Jean Girardin and Frédéric Kuhlmann.

The ''École nationale supérieure de chimie de Mulhouse'', established in 1822 to train personnel for chemical processes, was a rare institution specializing in industrial chemistry until its annexation by Germany in 1871, prompting Alsatian refugees in Paris to advocate for a similar school in the capital.

Economic and industrial context

The Second Industrial Revolution

ESPCI’s creation coincided with the rise oforganic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the science, scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic matter, organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain ...

, a key driver of the Second Industrial Revolution

The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, was a phase of rapid Discovery (observation), scientific discovery, standardisation, mass production and industrialisation from the late 19th century into the early ...

in the late 19th century, alongside advancements in electricity and turbine technology. This period saw a growing alignment between science and industry, particularly in organic chemistry, which was revolutionized by William Henry Perkin

Sir William Henry Perkin (12 March 1838 – 14 July 1907) was a British chemist and entrepreneur best known for his serendipitous discovery of the first commercial synthetic organic dye, mauveine, made from aniline. Though he failed in trying ...

’s accidental discovery of mauveine

Mauveine, also known as aniline purple and Perkin's mauve, was one of the first synthetic dyes. It was discovered serendipitously by William Henry Perkin in 1856 while he was attempting to synthesise the phytochemical quinine for the treatment o ...

in 1856. This breakthrough spurred the development of synthetic chemistry

Chemical synthesis (chemical combination) is the artificial execution of chemical reactions to obtain one or several products. This occurs by physical and chemical manipulations usually involving one or more reactions. In modern laboratory uses ...

, replacing natural products with synthetic alternatives, driven by rational applications of atomic theory and molecular representations.

Challenges in French Science and Chemistry

During this era of technological and scientific progress, French research faced significant challenges.Antoine Prost

Antoine Marie François Prost (29 October 1933) is a French historian who served as Professor Emeritus of History, University of Paris Panthéon-Sorbonne. He specialises in 20th-century French history, in particular the First World War.

Early ...

highlights the dire state of French science: libraries were underfunded, with the Paris law faculty receiving only 1,000 francs annually, and provincial science faculties limited to 1,800 francs for heating, lighting, and laboratories. No laboratories existed at the Paris Faculty of Sciences or the Museum. Research was further hampered by excessive centralization.

French chemistry struggled with the slow adoption of atomism

Atomism () is a natural philosophy proposing that the physical universe is composed of fundamental indivisible components known as atoms.

References to the concept of atomism and its Atom, atoms appeared in both Ancient Greek philosophy, ancien ...

. Albin Haller

Albin Haller (7 March 1849, Fellering – 1 May 1925) was a French chemist.W. J. Pope (1925) ''Nature'', Vol.115(2900), p.843 "Prof. Albin Haller, For. Mem. R.S" (obituary)

Haller founded the École Nationale Supérieure des Industries Chimiqu ...

, in a report for the ''Exposition Universelle'' (1900), noted the resistance to atomic theory in France, which hindered progress in organic chemistry. The outdated "system of equivalents," championed by Marcellin Berthelot

Pierre Eugène Marcellin Berthelot (; 25 October 1827 – 18 March 1907) was a French chemist and Republican politician noted for the ThomsenBerthelot principle of thermochemistry. He synthesized many organic compounds from inorganic substance ...

, persisted in French education until the late 19th century.

The French higher education system, disconnected from cutting-edge research, failed to meet the needs of emerging industries like chemistry and electricity, which required skilled engineers and technicians. While faculties provided outdated academic knowledge, grandes écoles adhered to a model suited to the

The French higher education system, disconnected from cutting-edge research, failed to meet the needs of emerging industries like chemistry and electricity, which required skilled engineers and technicians. While faculties provided outdated academic knowledge, grandes écoles adhered to a model suited to the First Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

, focusing on mathematics and mechanics but neglecting chemistry. Chemistry education was often undervalued, with terms like "chemist" used derogatorily at institutions like ''École centrale Paris

École or Ecole may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by Secondary education in France, secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing i ...

''.

Insufficient reforms

Prominent scientists like

Prominent scientists like Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist, pharmacist, and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, Fermentation, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization, the la ...

, Marcellin Berthelot

Pierre Eugène Marcellin Berthelot (; 25 October 1827 – 18 March 1907) was a French chemist and Republican politician noted for the ThomsenBerthelot principle of thermochemistry. He synthesized many organic compounds from inorganic substance ...

, Claude Bernard

Claude Bernard (; 12 July 1813 – 10 February 1878) was a French physiologist. I. Bernard Cohen of Harvard University called Bernard "one of the greatest of all men of science". He originated the term ''milieu intérieur'' and the associated c ...

, and Ernest Renan

Joseph Ernest Renan (; ; 27 February 18232 October 1892) was a French Orientalist and Semitic scholar, writing on Semitic languages and civilizations, historian of religion, philologist, philosopher, biblical scholar, and critic. He wrote wo ...

decried the state of French science in the 1850s and 1860s. Renan, in 1867, attributed Prussia’s victory at Sadowa to German scientific prowess, contrasting it with French deficiencies. Reforms began in the 1870s, with the law of July 12, 1875, allowing independent higher education institutions, and increased funding for faculties between 1875 and 1885. The decree of July 25, 1885, granted faculties greater autonomy and the ability to receive donations.

However, these measures fell short, particularly in chemistry, where the loss of Mulhouse’s chemistry school to Germany left a critical gap. The Paris Universal Exposition of 1878 highlighted France’s industrial lag, prompting Charles Lauth

Charles Lauth (1836–1913) was a French chemist. He synthesised methyl violet

Methyl violet is a family of organic compounds that are mainly used as dyes. Depending on the number of attached methyl groups, the color of the dye can be altered. It ...

to propose the creation of a National Chemistry School in a report to the Minister of Commerce and Agriculture, laying the groundwork for ESPCI’s establishment.

Establishment of the school

Influence of the Alsatian network and the German model

The authorship ofCharles Lauth

Charles Lauth (1836–1913) was a French chemist. He synthesised methyl violet

Methyl violet is a family of organic compounds that are mainly used as dyes. Depending on the number of attached methyl groups, the color of the dye can be altered. It ...

’s 1878 proposal was no coincidence. As a prominent member of the ''Association française pour l'avancement des sciences'' (AFAS), alongside Charles Adolphe Wurtz

Charles Adolphe Wurtz (; 26 November 181710 May 1884) was an Alsatian French chemist. He is best remembered for his decades-long advocacy for the atomic theory and for ideas about the structures of chemical compounds, against the skeptical opinio ...

, Charles Friedel

Charles Friedel (; 12 March 1832 – 20 April 1899) was a French chemist and Mineralogy, mineralogist.

Life

A native of Strasbourg, France, he was a student of Louis Pasteur at the University of Paris, Sorbonne. In 1876, he became a professor of ...

, Albin Haller

Albin Haller (7 March 1849, Fellering – 1 May 1925) was a French chemist.W. J. Pope (1925) ''Nature'', Vol.115(2900), p.843 "Prof. Albin Haller, For. Mem. R.S" (obituary)

Haller founded the École Nationale Supérieure des Industries Chimiqu ...

, and Paul Schützenberger

Paul Schützenberger (23 December 1829 – 26 June 1897) was a French chemist. He was born in Strasbourg, where his father Georges Frédéric Schützenberger (1779–1859) was professor of law, and his uncle Charles Schützenberger (1809–1881) ...

, Lauth shared a vision of science, its practice, and its relationship with industry, inspired by the German model. These five scientists formed the core of what historians Danielle Fauque and Georges Bram term the "Alsatian network."

This group promoted the German model, credited for the success of the world’s leading chemical industry at the time, through the AFAS, which Wurtz and Friedel helped found. The AFAS’s annual congresses, held in different cities, effectively disseminated their ideas. For Lauth and his colleagues, Germany’s industrial success stemmed from strong ties between businesses, research, and education. Germany boasted a robust network of autonomous, well-funded universities offering high-level, accessible education. Professors were numerous, well-compensated, and respected, and applied sciences were embraced. Additionally, Germany’s technical schools, nearly all equipped with chemistry laboratories by 1892, trained the engineers the industry needed. The German system’s effectiveness was proven by

This group promoted the German model, credited for the success of the world’s leading chemical industry at the time, through the AFAS, which Wurtz and Friedel helped found. The AFAS’s annual congresses, held in different cities, effectively disseminated their ideas. For Lauth and his colleagues, Germany’s industrial success stemmed from strong ties between businesses, research, and education. Germany boasted a robust network of autonomous, well-funded universities offering high-level, accessible education. Professors were numerous, well-compensated, and respected, and applied sciences were embraced. Additionally, Germany’s technical schools, nearly all equipped with chemistry laboratories by 1892, trained the engineers the industry needed. The German system’s effectiveness was proven by Justus von Liebig

Justus ''Freiherr'' von Liebig (12 May 1803 – 18 April 1873) was a Germans, German scientist who made major contributions to the theory, practice, and pedagogy of chemistry, as well as to agricultural and biology, biological chemistry; he is ...

, who, from 1825, emphasized precise laboratory techniques at his Giessen laboratory, a model for German universities and technical institutes led by his former students.

Key features of the German model—decentralization, well-funded universities, accessible education, pragmatism, and a focus on applied research—were absent in France, to the dismay of the Alsatian network.

Charles Lauth’s proposal for a national school

By 1878, when Lauth wrote to the Minister of Commerce and Agriculture, French higher education reforms were underway. Lauth’s proposal emphasized the need for research and teaching laboratories to train students in “living” chemistry and an education system focused on industrial applications. He envisioned an autonomous chemistry school, a model already well-established. Lauth’s proposed curriculum spanned three years, combining theoretical lectures with practical laboratory work. The first year would cover qualitative and quantitative mineral analysis and basic preparations, with lectures on inorganic and organic chemistry. The second year would focus on organic analysis, industrial analyses, and complex preparations, with lectures on major chemical industries. The third year would train students to solve industrial problems through methodical projects, with lectures highlighting the latest scientific and industrial advancements. Graduates would earn a special “chemical engineer” diploma after an examination or competition. This approach, supported by figures like

Lauth’s proposed curriculum spanned three years, combining theoretical lectures with practical laboratory work. The first year would cover qualitative and quantitative mineral analysis and basic preparations, with lectures on inorganic and organic chemistry. The second year would focus on organic analysis, industrial analyses, and complex preparations, with lectures on major chemical industries. The third year would train students to solve industrial problems through methodical projects, with lectures highlighting the latest scientific and industrial advancements. Graduates would earn a special “chemical engineer” diploma after an examination or competition. This approach, supported by figures like Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist, pharmacist, and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, Fermentation, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization, the la ...

and Marcellin Berthelot

Pierre Eugène Marcellin Berthelot (; 25 October 1827 – 18 March 1907) was a French chemist and Republican politician noted for the ThomsenBerthelot principle of thermochemistry. He synthesized many organic compounds from inorganic substance ...

, aimed to avoid the excessive abstraction of institutions like ''École Polytechnique

(, ; also known as Polytechnique or l'X ) is a ''grande école'' located in Palaiseau, France. It specializes in science and engineering and is a founding member of the Polytechnic Institute of Paris.

The school was founded in 1794 by mat ...

'' and the rudimentary empiricism of schools like the ''École nationale supérieure d'arts et métiers''. It emphasized experimental science and laboratory work to produce skilled chemical engineers capable of addressing the challenges of the emerging chemical industry.

However, Lauth’s national school proposal was not realized, reportedly due to resistance from grandes écoles and Parisian academics offended by his critiques.

Creation of the Municipal School in Paris

Undeterred, Lauth turned to the

Undeterred, Lauth turned to the Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

Municipal Council, where he served. On December 22, 1880, the council prioritized the school’s creation, allocating 10,000 francs for a feasibility study and forming a commission. On June 20, 1881, the Prefect of the Seine

In France, a Prefecture of Police (), headed by the Prefect of Police (), is an agency of the Government of France under the administration of the Ministry of the Interior. Part of the National Police, it provides a police force for an area limi ...

appointed 14 commission members, including Berthelot, Wurtz, and Lauth (as director of the Sèvres manufactory). The commission’s report, presented months later, outlined the school’s entrance requirements, internal regulations, study duration, curriculum, budget, and mission statement. Two innovations stood out: the inclusion of physics alongside chemistry, anticipating their mutual development, particularly in electricity, following the 1881 Paris International Electricity Exposition; and a 50-franc monthly stipend for students to broaden access, echoing the German model’s accessibility.

The report’s mission statement emphasized the school’s goal: to equip students with specialized scientific knowledge for significant roles in industrial settings, such as constructing physics apparatus or conducting industrial chemistry research. Unlike existing higher education institutions, which trained doctors, pharmacists, professors, and scholars, the ''École Municipale de Physique et de Chimie Industrielle'' would complement advanced primary education, focusing on practical, specialized training to produce foremen, engineers, or chemists. It drew inspiration from similar schools in Mulhouse, Zurich, and Strasbourg, and referenced Lauth’s 1878 letter advocating for a national chemistry school.

The ''École Municipale de Physique et de Chimie Industrielle'' was formally established by an ordinance signed by Prefect Charles Floquet

Charles Thomas Floquet (; 2 October 1828 – 18 January 1896) was a French lawyer and statesman.

Biography

He was born at Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port ( Basses-Pyrénées). Charles Floquet is the son of Pierre Charlemagne Floquet and Marie Léocadie ...

on August 28, 1882.

Two major periods of the school

The history of ESPCI, particularly its relationship with industry and research, can be divided into two distinct periods. The first, lasting until the late 1920s underPaul Langevin

Paul Langevin (23 January 1872 – 19 December 1946) was a French physicist who developed Langevin dynamics and the Langevin equation. He was one of the founders of the '' Comité de vigilance des intellectuels antifascistes'', an anti-fascist ...

’s directorship, was marked by a strong industrial focus. The second, beginning in the early 1930s, saw a significant shift toward fundamental sciences and research.

1882–1930: A school in service of the industry

Influence of the Alsatian network

The first three directors—Paul Schützenberger

Paul Schützenberger (23 December 1829 – 26 June 1897) was a French chemist. He was born in Strasbourg, where his father Georges Frédéric Schützenberger (1779–1859) was professor of law, and his uncle Charles Schützenberger (1809–1881) ...

, Charles Lauth

Charles Lauth (1836–1913) was a French chemist. He synthesised methyl violet

Methyl violet is a family of organic compounds that are mainly used as dyes. Depending on the number of attached methyl groups, the color of the dye can be altered. It ...

, and Albin Haller

Albin Haller (7 March 1849, Fellering – 1 May 1925) was a French chemist.W. J. Pope (1925) ''Nature'', Vol.115(2900), p.843 "Prof. Albin Haller, For. Mem. R.S" (obituary)

Haller founded the École Nationale Supérieure des Industries Chimiqu ...

—were instrumental in the school’s founding, alongside Charles Friedel

Charles Friedel (; 12 March 1832 – 20 April 1899) was a French chemist and Mineralogy, mineralogist.

Life

A native of Strasbourg, France, he was a student of Louis Pasteur at the University of Paris, Sorbonne. In 1876, he became a professor of ...

, an early board member, and Charles Adolphe Wurtz

Charles Adolphe Wurtz (; 26 November 181710 May 1884) was an Alsatian French chemist. He is best remembered for his decades-long advocacy for the atomic theory and for ideas about the structures of chemical compounds, against the skeptical opinio ...

, who served on the municipal council’s study commission. The ''École Municipale de Physique et de Chimie Industrielle'' (EMPCI), later ESPCI, was deeply shaped by the ideas of the Alsatian network, comprising these five scientists.

The school adopted the pragmatic German model championed by the Alsatian network, emphasizing practical and experimental training. The EMPCI curriculum allocated only a quarter of its time to theoretical courses, with the rest dedicated to industrially relevant activities: laboratory work, technical drawing, and technological problem-solving, with minimal lectures. Third-year students were introduced to industrial accounting, basic political economy, and discussions on manufacturing processes and industry needs. This reflected a strong commitment to industrial integration.

The institution maintained close ties with industry. Industrialists comprised nearly one-sixth of the board, ensuring alignment with industrial strategies by assigning some courses to scientists employed in industry. Faculty members also engaged directly in industrial projects: Schützenberger contributed to chemical manufacturing, particularly fertilizers and synthetic dyes; Lauth collaborated with the Saint-Denis chemical company’s research and production teams; and Haller consulted extensively with Parisian industrialists.

The student profile further reinforced the school’s industrial focus. Admission targeted graduates of advanced primary schools, equipped with practical skills in science and mathematics and inclined toward industrial careers, unlike lycée students, who showed little interest in technical fields, or those from basic primary schools, whose education was insufficient.

Neglect of scientific research

Despite the Alsatian network’s influence, the EMPCI diverged from Lauth’s original vision. Lauth criticized Parisian laboratories as inadequate for students seeking to learn, lacking proper guidance to translate scientific discoveries into practical outcomes or spark new industries. His proposed third-year curriculum aimed to train students in solving industrial problems while keeping them updated on scientific and industrial advancements. However, the EMPCI’s early curriculum prioritized technology over pure science, omitting the latest scientific developments, particularly in the third year, which focused on industrial accounting and economic discussions.

Research, even applied, was absent from the curriculum, with no time allocated for it. Regulations discouraged personal research by preparators, requiring them to dedicate their time to supervising students in laboratories, where third-year students spent most of their day. Despite this, exceptions were made, notably allowing

Despite the Alsatian network’s influence, the EMPCI diverged from Lauth’s original vision. Lauth criticized Parisian laboratories as inadequate for students seeking to learn, lacking proper guidance to translate scientific discoveries into practical outcomes or spark new industries. His proposed third-year curriculum aimed to train students in solving industrial problems while keeping them updated on scientific and industrial advancements. However, the EMPCI’s early curriculum prioritized technology over pure science, omitting the latest scientific developments, particularly in the third year, which focused on industrial accounting and economic discussions.

Research, even applied, was absent from the curriculum, with no time allocated for it. Regulations discouraged personal research by preparators, requiring them to dedicate their time to supervising students in laboratories, where third-year students spent most of their day. Despite this, exceptions were made, notably allowing Pierre Curie

Pierre Curie ( ; ; 15 May 1859 – 19 April 1906) was a French physicist, Radiochemistry, radiochemist, and a pioneer in crystallography, magnetism, piezoelectricity, and radioactivity. He shared the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics with his wife, ...

to research piezoelectricity

Piezoelectricity (, ) is the electric charge that accumulates in certain solid materials—such as crystals, certain ceramics, and biological matter such as bone, DNA, and various proteins—in response to applied mechanical stress.

The piezoel ...

.

Balancing Science and Industry

The early directors sought to balance the school’s industrial mission with scientific research, though this was challenging. On November 5, 1906, Haller proposed hosting foreign researchers to enhance the school’s reputation, citing the international renown of its faculty. Lauth, then a board member, opposed this, arguing that the school’s industrial focus should not shift toward pure science, as hosting foreign researchers could compromise its purpose.

Schützenberger also championed fundamental research.

The early directors sought to balance the school’s industrial mission with scientific research, though this was challenging. On November 5, 1906, Haller proposed hosting foreign researchers to enhance the school’s reputation, citing the international renown of its faculty. Lauth, then a board member, opposed this, arguing that the school’s industrial focus should not shift toward pure science, as hosting foreign researchers could compromise its purpose.

Schützenberger also championed fundamental research. Paul Langevin

Paul Langevin (23 January 1872 – 19 December 1946) was a French physicist who developed Langevin dynamics and the Langevin equation. He was one of the founders of the '' Comité de vigilance des intellectuels antifascistes'', an anti-fascist ...

noted that without Schützenberger’s and his successors’ support, Pierre Curie might not have completed his groundbreaking thesis on magnetism or discovered radium, potentially leaving the school. A 1903 evaluation of Curie acknowledged his tendency toward pure science but valued his contributions to the school’s prestige.

This balancing act enabled high-level research, notably by Pierre

Pierre is a masculine given name. It is a French form of the name Peter. Pierre originally meant "rock" or "stone" in French (derived from the Greek word πέτρος (''petros'') meaning "stone, rock", via Latin "petra"). It is a translation ...

and Marie Curie

Maria Salomea Skłodowska-Curie (; ; 7 November 1867 – 4 July 1934), known simply as Marie Curie ( ; ), was a Polish and naturalised-French physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity.

She was List of female ...

, but resources were limited. Terry Shinn notes that Pierre Curie, a mere lecturer, conducted his research in a dilapidated shed with outdated equipment.

From 1930: Embracing research

It was not until the early 1930s, under the leadership of

It was not until the early 1930s, under the leadership of Paul Langevin

Paul Langevin (23 January 1872 – 19 December 1946) was a French physicist who developed Langevin dynamics and the Langevin equation. He was one of the founders of the '' Comité de vigilance des intellectuels antifascistes'', an anti-fascist ...

, that ESPCI began to fully embrace fundamental research and pure science.

Nature of the changes

Terry Shinn identifies four key changes to the curriculum: a) applied mathematics courses were replaced by advanced theoretical mathematics; b) technological training was partially overshadowed by theoretical sciences and the interplay between theory and experimental discoveries; c) specialized studies supplanted multidisciplinarity; and d) research became an integral part of the curriculum. The proportion of practical training decreased from 74% to 65% of study time, while theoretical instruction expanded. Concurrently, fundamental research gained prominence, exemplified by René Lucas’s work onbirefringence

Birefringence, also called double refraction, is the optical property of a material having a refractive index that depends on the polarization and propagation direction of light. These optically anisotropic materials are described as birefrin ...

and Georges Champetier’s contributions to molecular chemistry. ESPCI became a hub for discussing and refining bold concepts from Louis de Broglie

Louis Victor Pierre Raymond, 7th Duc de Broglie (15 August 1892 – 19 March 1987) was a French theoretical physicist and aristocrat known for his contributions to quantum theory. In his 1924 PhD thesis, he postulated the wave nature of elec ...

and showcasing discoveries by Frédéric Joliot-Curie

Jean Frédéric Joliot-Curie (; ; 19 March 1900 – 14 August 1958) was a French chemist and physicist who received the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with his wife, Irène Joliot-Curie, for their discovery of induced radioactivity. They were t ...

. Between 1953 and 1970, the number of active researchers at ESPCI grew from 37 to 116. A 1971 report emphasized that “research is inseparable from true higher education. How can one teach the science being created without participating in its creation?” In 1937, ESPCI relaxed its earlier restrictions, allowing foreign researchers from Luxembourg and Czechoslovakia, limited to 10% of the French student body. Meanwhile, industrial influence waned, with industrialists’ representation on the board halving to 10% between 1950 and 1965.

Continued industrial connection

The integration of research training, occupying 8% of the curriculum per Shinn’s analysis, and the emphasis on fundamental research marked a return to the principles of the Alsatian network. Yet, ESPCI retained its industrial mission. Industrialists, though fewer, remained on the board, and practical, application-oriented training continued to dominate the curriculum. Even the most fundamental research maintained a focus on practical applications, following the example of the Curies and Langevin, who applied his theoretical work on ultrasonics to invent sonar during World War I. Langevin and his successors rejected any strict divide between pure and applied science. Langevin argued that scientists must connect with society’s needs through engineers and technicians, stating: “The scientist can no longer remain isolated but must be linked to the farmer and the worker, increasingly educated, through a continuous chain of intermediaries and interpreters represented by engineers and technicians at various levels of expertise and roles. The need has become clear to ensure this connection by creating institutions to train individuals not only informed about established science but, above all, immersed in its methods, understanding through direct and sustained experimentation and rigorous laboratory training how science is created, its provisional and living nature, and the degree of confidence its results warrant, too often taught dogmatically, definitively, and lifelessly.” This ethos was deepened by successors like

Langevin and his successors rejected any strict divide between pure and applied science. Langevin argued that scientists must connect with society’s needs through engineers and technicians, stating: “The scientist can no longer remain isolated but must be linked to the farmer and the worker, increasingly educated, through a continuous chain of intermediaries and interpreters represented by engineers and technicians at various levels of expertise and roles. The need has become clear to ensure this connection by creating institutions to train individuals not only informed about established science but, above all, immersed in its methods, understanding through direct and sustained experimentation and rigorous laboratory training how science is created, its provisional and living nature, and the degree of confidence its results warrant, too often taught dogmatically, definitively, and lifelessly.” This ethos was deepened by successors like Pierre-Gilles de Gennes

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes (; 24 October 1932 – 18 May 2007) was a French physicist and the Nobel Prize laureate in physics in 1991.

Education and early life

He was born in Paris, France, and was home-schooled to the age of 12. By the age of ...

.

The school today

UnderPierre-Gilles de Gennes

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes (; 24 October 1932 – 18 May 2007) was a French physicist and the Nobel Prize laureate in physics in 1991.

Education and early life

He was born in Paris, France, and was home-schooled to the age of 12. By the age of ...

, ESPCI achieved its current balance, becoming one of France’s top engineering schools. De Gennes encouraged faculty to bridge science and industry, emphasizing the potential applications of even the most fundamental research.

During his tenure, ESPCI expanded its fundamental research, hosting 20 laboratories, 18 affiliated with the CNRS, and two interdisciplinary research groups, collectively employing over 250 researchers and 40 foreign visitors. The school awards about 20 doctorates annually.

ESPCI maintains strong industry ties, filing approximately 40 patents yearly. Several companies have emerged from the school. Claude Boccara, scientific director until 2003, noted: “The significant partnerships we maintain with public research entities (Ministry of Research, CNRS, Medical Research Institute) and private sectors (large corporations, small and medium enterprises) give ESPCI a distinctive profile of innovative research, seamlessly spanning the most fundamental aspects to the most strategic applications.”

Timeline

See also

*École supérieure de physique et de chimie industrielles de la ville de Paris

ESPCI Paris (officially the École supérieure de physique et de chimie industrielles de la ville de Paris, , ''The City of Paris Industrial Physics and Chemistry Higher Educational Institution'') is a grande école founded in 1882 by the city of ...

* Pierre Curie

Pierre Curie ( ; ; 15 May 1859 – 19 April 1906) was a French physicist, Radiochemistry, radiochemist, and a pioneer in crystallography, magnetism, piezoelectricity, and radioactivity. He shared the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics with his wife, ...

and Marie Curie

Maria Salomea Skłodowska-Curie (; ; 7 November 1867 – 4 July 1934), known simply as Marie Curie ( ; ), was a Polish and naturalised-French physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity.

She was List of female ...

* Paul Langevin

Paul Langevin (23 January 1872 – 19 December 1946) was a French physicist who developed Langevin dynamics and the Langevin equation. He was one of the founders of the '' Comité de vigilance des intellectuels antifascistes'', an anti-fascist ...

* Pierre-Gilles de Gennes

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes (; 24 October 1932 – 18 May 2007) was a French physicist and the Nobel Prize laureate in physics in 1991.

Education and early life

He was born in Paris, France, and was home-schooled to the age of 12. By the age of ...

* Georges Charpak

Georges Charpak (; born Jerzy Charpak; 1 August 1924 – 29 September 2010) was a Polish-born French physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1992 for his invention of the multiwire proportional chamber.

Life

Georges Charpak was born ...

* Charles Adolphe Wurtz

Charles Adolphe Wurtz (; 26 November 181710 May 1884) was an Alsatian French chemist. He is best remembered for his decades-long advocacy for the atomic theory and for ideas about the structures of chemical compounds, against the skeptical opinio ...

* Charles Lauth

Charles Lauth (1836–1913) was a French chemist. He synthesised methyl violet

Methyl violet is a family of organic compounds that are mainly used as dyes. Depending on the number of attached methyl groups, the color of the dye can be altered. It ...

* Albin Haller

Albin Haller (7 March 1849, Fellering – 1 May 1925) was a French chemist.W. J. Pope (1925) ''Nature'', Vol.115(2900), p.843 "Prof. Albin Haller, For. Mem. R.S" (obituary)

Haller founded the École Nationale Supérieure des Industries Chimiqu ...

* Paul Schützenberger

Paul Schützenberger (23 December 1829 – 26 June 1897) was a French chemist. He was born in Strasbourg, where his father Georges Frédéric Schützenberger (1779–1859) was professor of law, and his uncle Charles Schützenberger (1809–1881) ...

* Charles Friedel

Charles Friedel (; 12 March 1832 – 20 April 1899) was a French chemist and Mineralogy, mineralogist.

Life

A native of Strasbourg, France, he was a student of Louis Pasteur at the University of Paris, Sorbonne. In 1876, he became a professor of ...

* Frédéric Joliot-Curie

Jean Frédéric Joliot-Curie (; ; 19 March 1900 – 14 August 1958) was a French chemist and physicist who received the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with his wife, Irène Joliot-Curie, for their discovery of induced radioactivity. They were t ...

and Irène Joliot-Curie

Irène Joliot-Curie (; ; 12 September 1897 – 17 March 1956) was a French chemist and physicist who received the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with her husband, Frédéric Joliot-Curie, for their discovery of induced radioactivity. They were ...

* Justus von Liebig

Justus ''Freiherr'' von Liebig (12 May 1803 – 18 April 1873) was a Germans, German scientist who made major contributions to the theory, practice, and pedagogy of chemistry, as well as to agricultural and biology, biological chemistry; he is ...

* Second Industrial Revolution

The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, was a phase of rapid Discovery (observation), scientific discovery, standardisation, mass production and industrialisation from the late 19th century into the early ...

* Organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the science, scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic matter, organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * {{Portal, Physics, Chemistry, History of Science, Technology, France History of education in France History of chemistry History of physics