History Of Bermuda on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The earliest depiction of the island is the inclusion of "La Bermuda" in the map of Pedro Martyr's 1511 ''

The earliest depiction of the island is the inclusion of "La Bermuda" in the map of Pedro Martyr's 1511 ''

On 2 June 1609, Sir

On 2 June 1609, Sir

In 1615, the colony was passed to a new company, the

In 1615, the colony was passed to a new company, the

Bermudians were raking

Bermudians were raking

With royal administration commencing under Charles II in 1683, and the end of company control in 1684, the island was able to change the basis of its economy from tobacco to maritime enterprises. The maritime economy included ship building, wrecking, whaling, piloting and fishing in local waters. The population at that time consisted of 5889 whites and 1737 slaves. While Tobacco ceased to be a commercial crop by 1710, Bermuda's fleet had grown from fourteen vessels in 1679 to sixty sloops, six brigantines and four ships in 1700.

These "Bermuda sloops" had their origin in the ship Jacob Jacobson first built after becoming shipwrecked on the island in 1619, and were based on craft sailing on the

With royal administration commencing under Charles II in 1683, and the end of company control in 1684, the island was able to change the basis of its economy from tobacco to maritime enterprises. The maritime economy included ship building, wrecking, whaling, piloting and fishing in local waters. The population at that time consisted of 5889 whites and 1737 slaves. While Tobacco ceased to be a commercial crop by 1710, Bermuda's fleet had grown from fourteen vessels in 1679 to sixty sloops, six brigantines and four ships in 1700.

These "Bermuda sloops" had their origin in the ship Jacob Jacobson first built after becoming shipwrecked on the island in 1619, and were based on craft sailing on the

Bermuda was a center of

Bermuda was a center of

Following the

Following the  With the buildup of the Royal Naval establishment in the first decades of the 19th century, a large number of military fortifications and batteries were constructed, and the numbers of regular infantry, artillery, and support units that composed the

With the buildup of the Royal Naval establishment in the first decades of the 19th century, a large number of military fortifications and batteries were constructed, and the numbers of regular infantry, artillery, and support units that composed the

Bermuda sent volunteer troops to fight in Europe with the British Army. They suffered severe losses. During the First World War, a number of Bermudians served in the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

During World War II, Bermuda's importance as a military base increased because of its location on the major trans-Atlantic shipping route. The Royal Naval dockyard on Ireland Island played a role similar to that it had during

Bermuda sent volunteer troops to fight in Europe with the British Army. They suffered severe losses. During the First World War, a number of Bermudians served in the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

During World War II, Bermuda's importance as a military base increased because of its location on the major trans-Atlantic shipping route. The Royal Naval dockyard on Ireland Island played a role similar to that it had during

Bermuda has prospered economically since World War II, developing into a highly successful offshore financial centre. Although tourism remains important to Bermuda's economy, it has for three decades been second to international business in terms of economic importance to the island.

The Royal Naval Dockyard, and the attendant military garrison, continued to be important to Bermuda's economy until the mid-20th century. In addition to considerable building work, the armed forces needed to source food and other materials from local vendors. Beginning in

Bermuda has prospered economically since World War II, developing into a highly successful offshore financial centre. Although tourism remains important to Bermuda's economy, it has for three decades been second to international business in terms of economic importance to the island.

The Royal Naval Dockyard, and the attendant military garrison, continued to be important to Bermuda's economy until the mid-20th century. In addition to considerable building work, the armed forces needed to source food and other materials from local vendors. Beginning in

in JSTOR

Jean de Chantal Kennedy, ''Isle of Devils: Bermuda under the Somers Island Company'' (Collins, London, 1971)

Henry C. Wilkinson, ''Bermuda from Sail to Steam: The History of the Island from 1784 to 1901: Volumes I and II'' (Oxford University, London, 1973)

Michael Jarvis, ''In the Eye of All Trade: Bermuda, Bermudians, and the Maritime Atlantic World, 1680–1783'' (University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2010)

Bermuda National Trust

— official website of the

National Museum of Bermuda

— official website of the

Bermuda

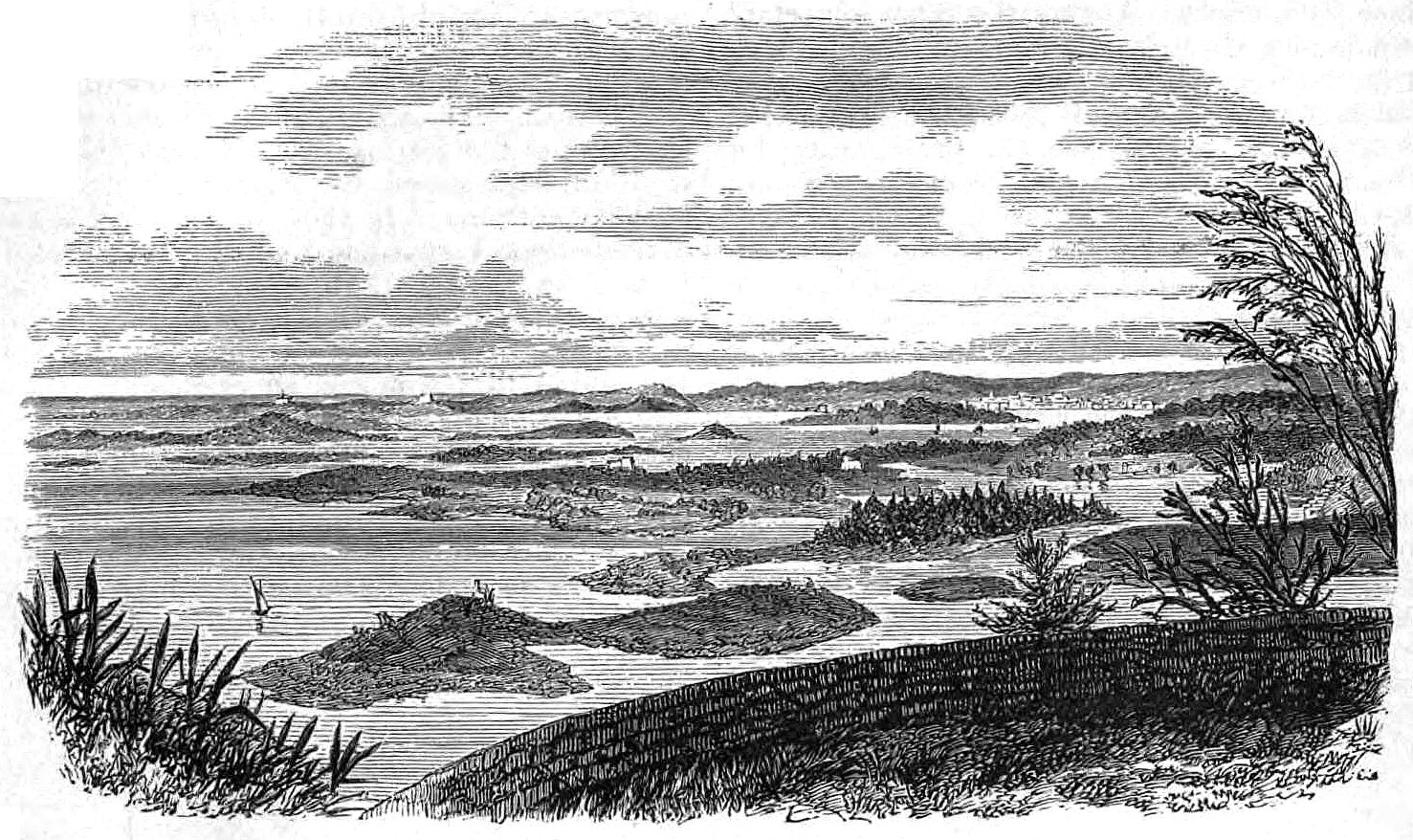

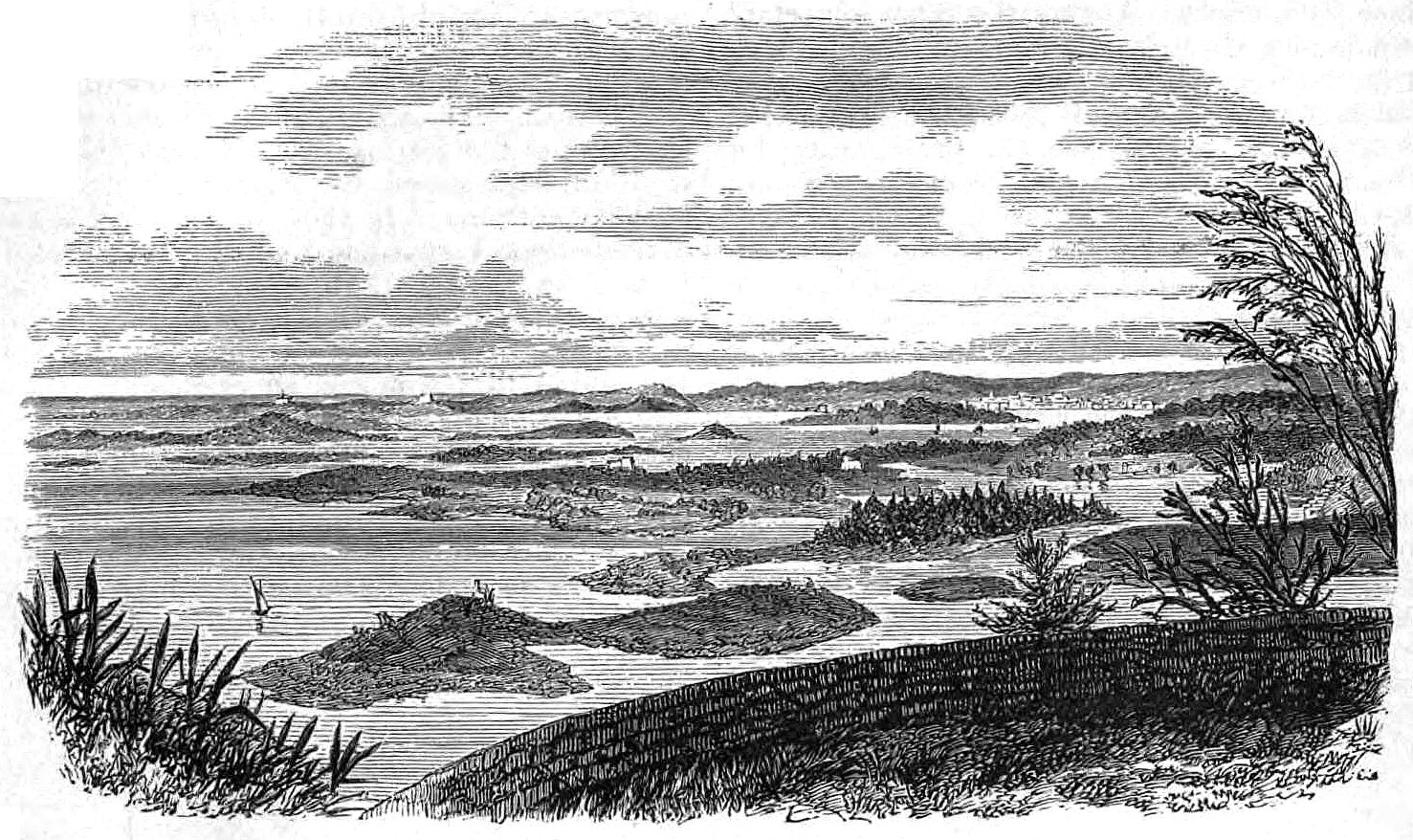

Bermuda is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The closest land outside the territory is in the American state of North Carolina, about to the west-northwest.

Bermuda is an ...

was first documented by a European in 1503 by Spanish explorer Juan de Bermúdez

Juan de Bermúdez (; ; born , died ) was a Spanish navigator of the 16th century, and the namesake for the island country Bermuda.

Early life

Juan Bermúdez was born in Palos de la Frontera, Province of Huelva, Crown of Castile.

Voyages

In 150 ...

. In 1609, the English Virginia Company

The Virginia Company was an English trading company chartered by King James I on 10 April 1606 with the objective of colonizing the eastern coast of America. The coast was named Virginia, after Elizabeth I, and it stretched from present-day ...

, which had established Jamestown in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

two years earlier, permanently settled Bermuda in the aftermath of a hurricane, when the crew and passengers of steered the ship onto the surrounding reef to prevent it from sinking, then landed ashore. Bermuda's first capital, St. George's, was established in 1612.

The Virginia Company administered the island as an extension of Virginia until 1614; its spin-off

Spin-off, Spin Off, Spin-Off, or Spinoff may refer to: Entertainment and media

*Spinoff (media), a media work derived from an existing work

*''The Spinoff'', a New Zealand current affairs magazine

* ''Spin Off'' (Canadian game show), a 2013 Canad ...

, the Somers Isles Company

The Somers Isles Company (fully, the Company of the City of London for the Plantacion of The Somers Isles or the Company of The Somers Isles) was formed in 1615 to operate the English colony of the Somers Isles, also known as Bermuda, as a commer ...

, took over in 1615 and managed the island until 1684, when the company's charter was revoked and Bermuda became an English Crown Colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony governed by Kingdom of England, England, and then Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain or the United Kingdom within the English overseas possessions, English and later British Empire. There was usua ...

. Following the 1707 unification of the parliaments of Scotland and England, which created the Kingdom of Great Britain

Great Britain, also known as the Kingdom of Great Britain, was a sovereign state in Western Europe from 1707 to the end of 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united the Kingd ...

, the islands of Bermuda became a British Crown Colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony governed by England, and then Great Britain or the United Kingdom within the English and later British Empire. There was usually a governor to represent the Crown, appointed by the British monarch on ...

.

When Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

joined Canada in 1949, Bermuda became the oldest remaining British colony. It has been the most populous remaining dependent territory since the return of Hong Kong to China

The handover of Hong Kong from the United Kingdom to the People's Republic of China was at midnight on 1 July 1997. This event ended 156 years of British rule in the former colony, which began in 1841.

Hong Kong was established as a special ...

in 1997. Bermuda became known as a "British Overseas Territory

The British Overseas Territories (BOTs) or alternatively referred to as the United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs) are the fourteen dependent territory, territories with a constitutional and historical link with the United Kingdom that, ...

" in 2002, as a result of the British Overseas Territories Act 2002

The British Overseas Territories Act 2002 (c.8) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which superseded parts of the British Nationality Act 1981. It makes legal provision for the renaming of the ''British Dependent Territories'' as ...

.

Initial discovery and early colony

The earliest depiction of the island is the inclusion of "La Bermuda" in the map of Pedro Martyr's 1511 ''

The earliest depiction of the island is the inclusion of "La Bermuda" in the map of Pedro Martyr's 1511 ''Legatio Babylonica

In 1501–1502, Peter Martyr d'Anghiera, an Italian humanist, was sent on a diplomatic mission to Mamluk Egypt by Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, in order to convince Sultan Qansuh al-Ghuri not to retaliate against his Christian ...

''. The earliest description of the island was Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (August 1478 – 1557), commonly known as Oviedo, was a Spanish soldier, historian, writer, botanist and colonist. Oviedo participated in the Spanish colonization of the West Indies, arriving in the first fe ...

' account of his 1515 visit with Juan de Bermúdez

Juan de Bermúdez (; ; born , died ) was a Spanish navigator of the 16th century, and the namesake for the island country Bermuda.

Early life

Juan Bermúdez was born in Palos de la Frontera, Province of Huelva, Crown of Castile.

Voyages

In 150 ...

aboard ''La Garza''. Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas

Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas (1549 – 28 March 1626 or 27 March 1625) was a chronicler, historian, and writer of the Spanish Golden Age, author of ''Historia general de los hechos de los castellanos en las Islas y Tierra Firme del mar O ...

in 1527 affirms the island was named after the captain who discovered it. Henry Harrisse

Henry Harrisse (May 28, 1829 – May 13, 1910) was a writer, lawyer, art critic, and American historian who authored books on the discovery of America and geographic representations of the New World.

Biography

Henry Harrisse was born Hen ...

documents earlier voyages by Juan Bermúdez in 1498, 1502, and 1503, though John Henry Lefroy

Sir John Henry Lefroy (28 January 1817 – 11 April 1890) was an English military officer and later colonial administrator who also distinguished himself with his scientific studies of the Earth's magnetism.

Biography

Lefroy was a son of th ...

noted Bermúdez left no account of visiting the island. Samuel Eliot Morison

Samuel Eliot Morison (July 9, 1887 – May 15, 1976) was an American historian noted for his works of maritime history and American history that were both authoritative and popular. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1912, and tau ...

lists a 1505 discovery by Juan Bermúdez, citing the investigation into the ''Archivo de Indias'' by Roberto Barreiro-Meiro. Compounding the confusion is the record of a Francisco Bermudez accompanying Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

on his first voyage, a Diego Bermudez accompanying Columbus on his fourth voyage, and Juan's brother Diego Bermudez accompanying Ponce de León

Ponce may refer to:

*Ponce (surname)

*Ponce (streamer) (born 1991), French streamer

*Ponce, Puerto Rico, a city in Puerto Rico

** Ponce High School

** Ponce massacre, 1937

* USS ''Ponce'', several ships of the US Navy

* Manuel Ponce, a Mexican com ...

in a 1513 voyage. Thus, the only clearly documented account is of Juan Bermudez visiting the island in 1515, with the implication he had discovered the island on an earlier voyage. The island was definitely on the homeward course for returning Spaniards, as they followed the Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream is a warm and swift Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida and up the eastern coastline of the United States, then veers east near 36°N latitude (North Carolin ...

north followed by the Westerlies

The westerlies, anti-trades, or prevailing westerlies, are prevailing winds from the west toward the east in the middle latitudes between 30 and 60 degrees latitude. They originate from the high-pressure areas in the horse latitudes (about ...

just north of Bermuda. The Spanish avoided the uninhabited island's reefs and hurricanes, calling it Demoniorum Insulam. Yet, Spanish Rock bears the date of 1543, but little further details. A Frenchman called Russell was wrecked there in 1570, followed by the Englishman Henry May in 1593, but both managed to escape. Spanish Capt. Diego Ramirez was stranded on the rocks of Bermuda after a storm in 1603, when he discovered the "devils reported to be about Bermuda" were actually the outcry of the Bermuda petrel

The Bermuda petrel (''Pterodroma cahow'') is a gadfly petrel. Commonly known in Bermuda as the cahow, a name derived from its eerie cries, this nocturnal ground-nesting seabird is the national bird of Bermuda, pictured on Bermudian currency. Berm ...

. He did note the former presence of men, including remnants of a wreck.

In late August 1585, an English ship ''Tiger'' commanded by Richard Grenville

Sir Richard Grenville ( – ), also spelt Greynvile, Greeneville, and Greenfield, was an English privateer and explorer. Grenville was lord of the manors of Stowe, Cornwall and Bideford, Devon. He subsequently participated in the plantat ...

on his return from the Roanoke Colony

The Roanoke Colony ( ) refers to two attempts by Sir Walter Raleigh to found the first permanent English settlement in North America. The first colony was established at Roanoke Island in 1585 as a military outpost, and was evacuated in 1586. ...

, fought and captured a larger Spanish ship ''Santa Maria de San Vicente'' off the shores of Bermuda.

The 1609 shipwreck of ''Sea Venture''

On 2 June 1609, Sir

On 2 June 1609, Sir George Somers

Sir George Somers (before 24 April 1554 – 9 November 1610) was an English privateer and naval hero, knighted for his achievements and the Admiral of the Virginia Company of London. He achieved renown as part of an expedition led by ...

had set sail aboard , the new flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

of the Virginia Company

The Virginia Company was an English trading company chartered by King James I on 10 April 1606 with the objective of colonizing the eastern coast of America. The coast was named Virginia, after Elizabeth I, and it stretched from present-day ...

, leading a fleet of nine vessels, loaded with several hundred settlers, food and supplies for the new English colony of Jamestown, in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

. Somers had previous experience sailing with both Sir Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( 1540 – 28 January 1596) was an English Exploration, explorer and privateer best known for making the Francis Drake's circumnavigation, second circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition between 1577 and 1580 (bein ...

and Sir Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebell ...

. The fleet was caught in a storm on 24 July, and ''Sea Venture'' was separated and began to founder. When the reefs to the East of Bermuda were spotted, the ship was deliberately driven on them to prevent its sinking, thereby saving all aboard, 150 sailors and settlers, and one dog. William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's play ''The Tempest

''The Tempest'' is a Shakespeare's plays, play by William Shakespeare, probably written in 1610–1611, and thought to be one of the last plays that he wrote alone. After the first scene, which takes place on a ship at sea during a tempest, th ...

'', in which the character Ariel

Ariel may refer to:

Film and television

*Ariel Award, a Mexican Academy of Film award

* ''Ariel'' (film), a 1988 Finnish film by Aki Kaurismäki

*, a Russian film directed by Yevgeni Kotov

* ''ARIEL Visual'' and ''ARIEL Deluxe'', a 1989 and 1991 ...

refers to the "still-vex'd Bermoothes" (I.ii.229), is thought to have been inspired by William Strachey

William Strachey (4 April 1572 – buried 16 August 1621) was an English writer whose works are among the primary sources for the early history of the English colonisation of North America. He is best remembered today as the eye-witness reporter ...

's and Silvester Jourdain's accounts of the shipwreck.

The survivors spent nine months on Bermuda. With ship's supplies mostly gone except for some domestic pigs

The pig (''Sus domesticus''), also called swine (: swine) or hog, is an Omnivore, omnivorous, Domestication, domesticated, even-toed ungulate, even-toed, hoofed mammal. It is named the domestic pig when distinguishing it from other members of ...

, the castaways subsisted on rainwater, palm tree pulp, cedar berries, fish, birds (such as Bermuda petrel

The Bermuda petrel (''Pterodroma cahow'') is a gadfly petrel. Commonly known in Bermuda as the cahow, a name derived from its eerie cries, this nocturnal ground-nesting seabird is the national bird of Bermuda, pictured on Bermudian currency. Berm ...

), and by hunting for the plentiful wild hog

A feral pig is a pig, domestic pig which has gone feral, meaning it lives in the wild. The term feral pig has also been applied to wild boars, which can interbreed with domestic pigs. They are found mostly in the Americas and Australia. Razorb ...

s from past Bermuda shipwrecks.

The master's mate

Master's mate is an obsolete rating which was used by the British Royal Navy, Royal Navy, United States Navy and merchant services in both countries for a senior petty officer who assisted the sailing master, master. Master's mates evolved into th ...

and 7 other sailors were lost at sea when ''Sea Venture''s longboat was rigged with a mast and sent in search of Jamestown to rescue the lot. The sailors were not seen again. The remainder of castaways built two new ships: ''Deliverance'' at and 80 tons, and ''Patience'' at and 30 tons, mostly from Bermuda cedar

''Juniperus bermudiana'' is a species of juniper endemic to Bermuda. This species is most commonly known as Bermuda cedar, but is also referred to as Bermuda juniper ( Bermudians refer to it simply as ''cedar''). Historically, this tree formed w ...

. When the two new vessels were completed, most of the survivors set sail on May 10th, completing their journey to Jamestown on June 8, 1610. Christopher Carter and Edward Waters remained, the latter being accused of murder, while four others had died, including John Rolfe

John Rolfe ( – March 1622) was an English explorer, farmer and merchant. He is best known for being the husband of Pocahontas and the first settler in the colony of Virginia to successfully cultivate a tobacco crop for export.

He played a ...

's infant daughter. Later in Jamestown, Rolfe's wife died (and he would eventually marry a native, Pocahontas

Pocahontas (, ; born Amonute, also known as Matoaka and Rebecca Rolfe; 1596 – March 1617) was a Native American woman belonging to the Powhatan people, notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. S ...

). The castaways arrived only to find the colony's population almost annihilated by the Starving Time

The Starving Time at Jamestown in the Colony of Virginia was a period of starvation during the winter of 1609–1610. There were about 500 Jamestown residents at the beginning of the winter; by spring only 61 people remained alive.

The colonis ...

, which had left only sixty survivors. According to Sir William Monson, the "swine

Suina (also known as Suiformes) is a suborder of omnivorous, non-ruminant artiodactyl mammals that includes the domestic pig and peccaries. A member of this clade is known as a suine. Suina includes the family Suidae, termed suids, known in ...

brought from Bermuda" saved Virginia until the timely arrival of Lord De La Warre.

Somers returned to Bermuda on ''Patience'' in June and found Carter and Waters alive. Somers soon died, however, and while his heart was buried at Saint Georges, his nephew, Captain Matthew Somers, returned his embalmed body to England for burial at Dorset

Dorset ( ; Archaism, archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Somerset to the north-west, Wiltshire to the north and the north-east, Hampshire to the east, t ...

.

1612 official settlement

Two years later, in 1612, the Virginia Company's Royal Charter was officially extended to include the island, and a party of sixty settlers was sent on ''Plough'', under the command of Sir Richard Moore, the island's first governor. Joining the two men left behind by ''Deliverance'' and ''Patience'' (who had taken up residence on Smith's Island) and Edward Chard, they founded and commenced construction of the town ofSt. George

Saint George (;Geʽez: ጊዮርጊስ, , ka, გიორგი, , , died 23 April 303), also George of Lydda, was an early Christian martyr who is venerated as a saint in Christianity. According to holy tradition, he was a soldier in the ...

, designated as Bermuda's first capital, the oldest continually inhabited English town in the New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

.

Bermuda struggled throughout the following seven decades to develop a viable economy. The Virginia Company, finding the colony unprofitable, briefly handed its administration to the Crown in 1614. The following year, 1615, King James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

* James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

* James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

* James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334� ...

granted a charter to a new company, the Somers Isles Company

The Somers Isles Company (fully, the Company of the City of London for the Plantacion of The Somers Isles or the Company of The Somers Isles) was formed in 1615 to operate the English colony of the Somers Isles, also known as Bermuda, as a commer ...

, formed by the same shareholders, which ran the colony until it was dissolved in 1684. (The Virginia Company itself was dissolved after its charter was revoked in 1624). Representative government was introduced to Bermuda in 1620, when its House of Assembly

House of Assembly is a name given to the legislature or lower house of a bicameral parliament. In some countries this may be at a subnational level.

Historically, in British Crown colonies as the colony gained more internal responsible g ...

held its first session, and it became a self-governing colony.

Somers Isles Company (1615–1684)

In 1615, the colony was passed to a new company, the

In 1615, the colony was passed to a new company, the Somers Isles Company

The Somers Isles Company (fully, the Company of the City of London for the Plantacion of The Somers Isles or the Company of The Somers Isles) was formed in 1615 to operate the English colony of the Somers Isles, also known as Bermuda, as a commer ...

, named after the admiral who saved his passengers from the ''Sea Venture''. Many Virginian place names refer to the archipelago, such as Bermuda City, and Bermuda Hundred

Bermuda Hundred was the first Hundred (county division), administrative division in the English overseas possessions, English colony of Virginia Colony, Virginia. It was founded by Sir Thomas Dale in 1613, six years after Jamestown, Virginia, ...

. The first British colonial currency was struck in Bermuda.

Bermuda was divided by Richard Norwood

Richard Norwood ( – ) was an English mathematician, diver, and surveyor. He has been called "Bermuda’s outstanding genius of the seventeenth century".

Early life and first survey of Bermuda

Born about 1590, Richard Norwood was sent out by ...

into eight equally sized administrative areas west of St. George's called "tribes" (today known as "parishes"). These "tribes" were areas of land partitioned off to the principal "Adventurers" (investors) of the company, from east to west – Bedford, Smiths, Cavendish, Paget, Mansell, Warwick, and Sandys.

The company sent 600 settlers in nine ships between 1612 and 1615. Governor Moore dug a well in St. George, then built fortifications including Paget and Smith's batteries at the entrance of the harbour, King's and Charles' at the entrance to Castle Harbour, Pembroke Fort on Cooper's Island, and Gates' Fort, St. Katherine's Fort and Warwick Castle to defend St. George. In 1614, the first English-grown tobacco was exported, the same tobacco variety John Rolfe started to grow in Virginia. The exporting of ambergris

Ambergris ( or ; ; ), ''ambergrease'', or grey amber is a solid, waxy, flammable substance of a dull grey or blackish colour produced in the digestive system of sperm whales. Freshly produced ambergris has a marine, fecal odor. It acquires a sw ...

was especially lucrative. Slavery in Bermuda

In August 1616, plantain, sugarcane, fig, and pineapple plants were imported along with the first Indian and Negro, the first English colony to use enslaved Africans. By 1619, Bermuda had between fifty and a hundred black enslaved persons. These were a mixture of nativeAfricans

The ethnic groups of Africa number in the thousands, with each ethnicity generally having their own language (or dialect of a language) and culture. The ethnolinguistic groups include various Afroasiatic, Khoisan, Niger-Congo, and Nilo-Sahara ...

who were trafficked to the Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

via the African slave trade

Slavery has historically been widespread in Africa. Systems of servitude and slavery were once commonplace in parts of Africa, as they were in much of the rest of the ancient and medieval world. When the trans-Saharan slave trade, Red Sea s ...

and Native Americans who were enslaved from the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were the British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America.

The Thirteen C ...

. The first African slaves arrived in Bermuda in 1617, not from Africa but from the West Indies. Bermuda Governor Tucker sent a ship to the West Indies to find black slaves to dive for pearls in Bermuda. More black slaves were later trafficked to the island in large numbers, originating from America and the Caribbean.

As the black population grew, so did the fear of insurrection among the white settlers. In 1623, a law to restrain the insolence of the Negroes was passed in Bermuda. It forbade blacks to buy or sell, barter or exchange tobacco or any other produce for goods without the consent of their master. Unrest amongst the slaves predictably erupted several times over the next decades. Major rebellions occurred in 1656, 1661, 1673, 1682, 1730 and 1761. In 1761 a conspiracy was discovered that involved the majority of the blacks on the island. Six slaves were executed and all black celebrations were prohibited.

Agricultural diversification

Though Bermuda exported more tobacco than Virginia until 1625, Bermuda diversified its agriculture to include corn, potatoes, fruit trees, poultry and livestock. This was especially true when prices collapsed in 1630, and tobacco took its toll on soil fertility, though the company continued to use tobacco as a medium of exchange and resist a diversified economy. Tobacco exports peaked in 1684, the last year of company control. English immigration essentially ceased by the 1620s when all available land was occupied. Because of its limited land area, Bermuda relied on emigration, especially to the developing English colonies in the Bahamas, the Carolinas, New York and the Caribbean. Between 1620 and 1640, 1200 emigrated, while the population reached 4000 in 1648. Between 1679 and 1690, 2000 emigrated, while the population reached 6248 in 1691. The archipelago's limited land area and resources led to the creation of what may be the earliest conservation laws of theNew World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

. In 1616 and 1620, acts were passed banning the hunting of certain birds and young tortoises.

English Civil War in the Bermuda

In 1649, theEnglish Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

was in its seventh year and King Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

was beheaded in Whitehall, London. In Bermuda, related tensions resulted in civil war on the island; it was ended by militias. The majority of colonists developed a strong sense of devotion to the Crown. Dissenters, such as Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

s and Independents, were pushed to settle the Bahamas

The Bahamas, officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic and island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean. It contains 97 per cent of the archipelago's land area and 88 per cent of ...

under William Sayle

Captain William Sayle ( 1590 – 1671) was a prominent English landholder who was Governor of Bermuda in 1643 and again in 1658. As an Independent in religion and politics, and an adherent of Oliver Cromwell, he was dissatisfied with life in Ber ...

. However, the Earl of Dorset

Earl of Dorset is a title that has been created at least four times in the Peerage of England. Some of its holders have at various times also held the rank of marquess and, from 1720, duke.

A possible first creation is not well documented. About ...

, a royalist, was replaced by the Earl of Warwick

Earl of Warwick is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom which has been created four times in English history. The name refers to Warwick Castle and the town of Warwick.

Overview

The first creation came in 1088, and the title was held b ...

, a Puritan, as governor of the Somers Island Company. Sayle and most of the emigrants were allowed to return to Bermuda in 1656.

Bermuda and Virginia, as well as Antigua and Barbados were, however, the subjects of the September 1650 Prohibitory Act of the Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament describes the members of the Long Parliament who remained in session after Colonel Thomas Pride, on 6 December 1648, commanded his soldiers to Pride's Purge, purge the House of Commons of those Members of Parliament, members ...

, and the Atlantic fleet was instructed to bring these opposing colonies into obedience. At the same time, John Danvers

Sir John Danvers (c. 1585–buried 28 April 1655) was an English courtier and politician who was one of the signatories of the death warrant of Charles I.

Life

Danvers was the third and youngest son of Sir John Danvers of Dauntsey, Wiltshi ...

, governor of the Somers Island Company, and the other adventurers were forced to take the oath of allegiance to the Commonwealth. Then in the 1651 Navigation Act

The Navigation Acts, or more broadly the Acts of Trade and Navigation, were a series of English laws that developed, promoted, and regulated English ships, shipping, trade, and commerce with other countries and with its own colonies. The laws al ...

, trade was restricted to English ships.

An Act prohibiting Trade with Barbados, Virginia, Bermuda and Antego, specified that:

''due punishment einflicted upon the said Delinquents, do Declare all and every the said persons in Barbada's, Antego, Bermuda's and Virginia, that have contrived, abetted, aided or assisted those horrid Rebellions, or have since willingly joyned with them, to be notorious Robbers and Traitors, and such as by the Law of Nations are not to be permitted any maner of Commerce or Traffique with any people whatsoever; and do forbid to all maner of persons, Foreiners, and others, all maner of Commerce, Traffique and Correspondency whatsoever, to be used or held with the said Rebels in the Barbada's, Bermuda's, Virginia and Antego, or either of them.'' All Ships that Trade with the Rebels may be surprised. Goods and tackle of such ships not to be embezeled, till judgement in the Admiralty.; Two or three of the Officers of every ship to be examined upon oath.In 1658, the Company appointed Sayle Governor of Bermuda, and the islanders took the oath of allegiance to the

Lord Protector

Lord Protector (plural: ''Lords Protector'') is a title that has been used in British constitutional law for the head of state. It was also a particular title for the British heads of state in respect to the established church. It was sometime ...

.

Indentured servitude and slavery in 17th century Bermuda

Among the emigrants after Norwood finished his survey wereBridewell

Bridewell Palace in London was built as a residence of King Henry VIII and was one of his homes early in his reign for eight years. Given to the City of London Corporation by his son King Edward VI in 1553 as Bridewell Hospital for use as a ...

, Newgate

Newgate was one of the historic seven gates of the London Wall around the City of London and one of the six which date back to Roman times. Newgate lay on the west side of the wall and the road issuing from it headed over the River Fleet to Mid ...

and gaol

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol, penitentiary, detention center, correction center, correctional facility, or remand center, is a facility where people are imprisoned under the authority of the state, usually as punishment for various cri ...

transportees, indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract called an "indenture", may be entered voluntarily for a prepaid lump sum, as payment for some good or ser ...

, and "maids for wives". Yet most were emigrant families bound for four to five years as tenant farmer

A tenant farmer is a farmer or farmworker who resides and works on land owned by a landlord, while tenant farming is an agricultural production system in which landowners contribute their land and often a measure of operating capital and ma ...

s, paying half the tobacco they grew as rent to their landlord. This tenantry, indentured servitude of five years in return for passage, and family labor, reduced the need for slaves in growing tobacco and provisions. Thus, though Bermuda was a slave society, slavery was not essential to the agriculture economy, and Bermuda did not actively import slaves, instead relying on those black and Indian adults captured by privateers, then sold as slaves in Bermuda. This was a break in the usual pattern, in which slaves were purchased in Africa from local chiefs who had enslaved them in wars, or for committing crimes. Black indentures were for 99 years or life. The few Scot exiles received after the Civil War were indentured for seven years, while the few Irish exiles from that same period caused the slave trouble of 1664, and were hence forbidden entry onwards. The indentured system importance ceased by 1668. This non-dependence on slavery changed however, when the island moved to a maritime economy in the 1690s, and incorporated slave sailors, carpenters, coopers, blacksmiths, masons, and shipwright

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other floating vessels. In modern times, it normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces i ...

s. Hiring out of these skilled slaves became commonplace for their owners, with slaves retaining only a third of the wages they earned. By 1710, slaves were doing much vital work and constituted 3,517 of the total population of 8,366 in 1721.

Slaves could be obtained by sale or purchase, auction debt, legal seizure or by gift. The price of a slave depended on demand. Throughout the 17th century children sold for £8, women from £10 to £20, and able bodied men for around £26.

Slave revolts were a threat since 1623, while a revolt in 1656 resulted in executions and banishments. A 1664 revolt was stopped early, as was one in 1673, and again in 1681, which resulted in five executions. These revolts resulted in the orders of 1674 mandating that slaves straying from their premises, wandering at night without permission, or the gathering of two or three slaves from different tribes, be whipped. Any blacks deemed free were required to become slaves again or leave the island. The importation of additional slaves was also banned. A Jamaican slave named Tom was deported in 1682, when his rebellious plot was divulged by two Bermudian slaves.

The 18th century

The salt trade and the Turks Islands

Bermudians were raking

Bermudians were raking sea salt

Sea salt is salt that is produced by the evaporation of seawater. It is used as a seasoning in foods, cooking, cosmetics and for preserving food. It is also called bay salt, solar salt, or simply salt. Like mined rock salt, production of sea sal ...

in the Caribbean since the 1630s, an essential ingredient for making cheese, butter, and preserving meat and fish. Rakers would channel sea water in salt pans for evaporation. Salt Cay and Grand Turk Island

Grand Turk is an island in the Turks and Caicos Islands, a British Overseas Territory, tropical islands in the Lucayan Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean and northern West Indies. It is the largest island in the Turks Islands (the smaller of th ...

became salt colonies in the 1680s. According to Jarvis, "these small, hot, dry, and barren islands" were perfect for salt production since the limestone, absence of fresh water, and limited rain fall combined to make the soil unfertile. Yet, average temperatures in the eighties Fahrenheit and the eastern trade wind facilitated evaporation of sea water into a saturated brine

Brine (or briny water) is a high-concentration solution of salt (typically sodium chloride or calcium chloride) in water. In diverse contexts, ''brine'' may refer to the salt solutions ranging from about 3.5% (a typical concentration of seawat ...

for salt crystallized. Natural ponds were augmented with sluice

A sluice ( ) is a water channel containing a sluice gate, a type of lock to manage the water flow and water level. There are various types of sluice gates, including flap sluice gates and fan gates. Different depths are calculated when design s ...

s and causeway

A causeway is a track, road or railway on the upper point of an embankment across "a low, or wet place, or piece of water". It can be constructed of earth, masonry, wood, or concrete. One of the earliest known wooden causeways is the Sweet T ...

s. Salt originating from this province was cherished for its "brilliant color, purity, and versatility," according to Jarvis. In 1708, eighteen vessels were involved in raking salt, and this number grew to 65 in 1716, during the March to November raking season. By 1740, 200 vessels were loading salt annually from Grand Turk and Salt Cay, while a few dozen rakers stayed during the winter to repair pans.

Outside any colonial jurisdiction, Great Britain nevertheless claimed the islands "by right of Bermudian discovery, seasonal occupation, and improvement," according to Jarvis. Yet, France and Spain disputed Britain's claims with many attacks, coupled with those by pirates. Attacks from France and Spain commenced in 1709 and did not stop until 1764, when Great Britain's sovereignty was recognized. In 1693, Bahamas governor Nicholas Trott

Nicholas Trott (19 January 1663 – 21 January 1740) was an 18th-century British judge, legal scholar and writer. He had a lengthy legal and political career in Charleston, South Carolina and served as the colonial chief justice from 1703 until ...

taxed the rakers, and renewed those taxes in 1738. Peace transformed the raking business from an almost all white enterprise, to mixed slave and free labor. Seasonal rakers also increased from 300 in 1768 to almost 800 in 1775.

When the Bermudian sloop '' Seaflower'' was seized by the Bahamians in 1701, the response of Bermuda Governor Bennett was to issue letters of marque

A letter of marque and reprisal () was a government license in the Age of Sail that authorized a private person, known as a privateer or corsair, to attack and capture vessels of a foreign state at war with the issuer, licensing internationa ...

to Bermudian Privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

s. In 1706, Spanish and French forces ousted the Bermudians, but were driven out themselves three years later by a Bermudian privateer under the command of Captain Lewis Middleton

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* " Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohe ...

in what was probably Bermuda's only independent military operation. His ship, the ''Rose'', attacked a Spanish and a French privateer holding a captive English vessel. Defeating the two enemy vessels, the ''Rose'' then cleared out the thirty-man garrison left by the Spanish and French.

In 1766, the Board of Trade

The Board of Trade is a British government body concerned with commerce and industry, currently within the Department for Business and Trade. Its full title is The Lords of the Committee of the Privy Council appointed for the consideration of ...

granted Andrew Symmer, a Bermudian merchant, the Crown Agent for the Turks and Caicos Islands. Symmer then set a residency requirement of six months, modified the rakers elected government of five commissioners, initiated a mandatory militia requirement, and taxed each bushel of salt. Bahamian governor Thomas Shirley then tried to take control in 1772 and drive away the Bermudian rakers. By then, 750 of the 800 Turks Islands' rakers were from Bermuda. In 1774, Bermuda sent a sloop to protect their rakers after a Bahamian tax collector was beaten. A veto of the Bahamian Acts by the Board of Trade prevented escalating violence.

The Bahamas, meanwhile, was incurring considerable expense in absorbing loyalist refugees from the now-independent American colonies, and returned to the idea of taxing Turks salt for the needed funds. The Bahamian government ordered that all ships bound for the Turk Islands obtain a license at Nassau first. The Bermudians refused to do this. Following this, Bahamian authorities seized the Bermuda sloop

The Bermuda sloop is a historical type of fore-and-aft rigged single-masted sailing vessel developed on the islands of Bermuda in the 17th century. Such vessels originally had gaff rigs with quadrilateral sails, but evolved to use the Bermuda ri ...

s ''Friendship'' and ''Fanny'' in 1786. Shortly after, three Bermudian vessels were seized at Grand Caicos, with $35,000 worth of goods salvaged from a French ship. French privateers were becoming a menace to Bermudian operations in the area, at the time, but the Bahamians were their primary concern.

The Bahamian government re-introduced a tax on salt from the Turks, annexed them to the Bahamas, and created a seat in the Bahamian parliament to represent them. The Bermudians refused these efforts also, but the continual pressure from the Bahamians had a negative effect on the salt industry. In 1806, the Bermudian customs authorities went some way toward acknowledging the Bahamian annexation when it ceased to allow free exchange between the Turks and Bermuda (this affected many enslaved Bermudians, who, like the free ones, had occupied the Turks only seasonally, returning to their homes in Bermuda after the year's raking had finished).

That same year, French privateers attacked the Turks, burning ships and absconding with a large sloop. The Bahamians refused to help, and the Admiralty in Jamaica claimed the Turks were beyond its jurisdiction. Two hurricanes, the first in August 1813, the second in October 1815, destroyed more than two hundred buildings and significant salt stores; and sank many vessels. By 1815, the United States, the primary client for Turks salt, had been at war with Britain (and hence Bermuda) for three years, and had established other sources of salt.

With the destruction wrought by the storm, and the loss of market, many Bermudians abandoned the Turks, and those remaining were so distraught that they welcomed the visit of the Bahamian governor in 1819. The British government eventually assigned political control to the Bahamas, which the Turks and Caicos remained a part of until the 1840s.

One Bermudian salt raker, Mary Prince

Mary Prince (c. 1 October 1788 – after 1833) was the first black woman to publish an autobiography of her experience as a slave, born in the colony of Bermuda to an enslaved family of African descent. After being sold a number

of times and b ...

, however, was to leave a scathing record of Bermuda's activities there in ''The History of Mary Prince'', a book which helped to propel the abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

cause to the 1834 emancipation of slaves throughout the Empire.

Shipbuilding and the maritime economy

With royal administration commencing under Charles II in 1683, and the end of company control in 1684, the island was able to change the basis of its economy from tobacco to maritime enterprises. The maritime economy included ship building, wrecking, whaling, piloting and fishing in local waters. The population at that time consisted of 5889 whites and 1737 slaves. While Tobacco ceased to be a commercial crop by 1710, Bermuda's fleet had grown from fourteen vessels in 1679 to sixty sloops, six brigantines and four ships in 1700.

These "Bermuda sloops" had their origin in the ship Jacob Jacobson first built after becoming shipwrecked on the island in 1619, and were based on craft sailing on the

With royal administration commencing under Charles II in 1683, and the end of company control in 1684, the island was able to change the basis of its economy from tobacco to maritime enterprises. The maritime economy included ship building, wrecking, whaling, piloting and fishing in local waters. The population at that time consisted of 5889 whites and 1737 slaves. While Tobacco ceased to be a commercial crop by 1710, Bermuda's fleet had grown from fourteen vessels in 1679 to sixty sloops, six brigantines and four ships in 1700.

These "Bermuda sloops" had their origin in the ship Jacob Jacobson first built after becoming shipwrecked on the island in 1619, and were based on craft sailing on the Zuiderzee

The Zuiderzee or Zuider Zee (; old spelling ''Zuyderzee'' or ''Zuyder Zee''), historically called Lake Almere and Lake Flevo, was a shallow bay of the North Sea in the northwest of the Netherlands. It extended about 100 km (60 miles) inla ...

and the Dutch coastal sloep. These two-masted vessels, with the mast "raked" or inclined 15 degrees aft, carried fore-and-aft rig

A fore-and-aft rig is a sailing ship rig with sails set mainly in the median plane of the keel, rather than perpendicular to it, as on a square-rigged vessel.

Description

Fore-and-aft rigged sails include staysails, Bermuda rigged sails, g ...

s of triangular Bermuda sails. Large mainsail

A mainsail is a sail rigged on the main mast (sailing), mast of a sailing vessel.

* On a square rigged vessel, it is the lowest and largest sail on the main mast.

* On a fore-and-aft rigged vessel, it is the sail rigged aft of the main mast. T ...

s were fixed to elongated booms, giving the sloop a large sail area for maximum speed, averaging 3 knots, but known to exceed 5 knots. Finally, these sloops were especially adept at sailing into the wind

Sailing into the wind is a sailing expression that refers to a sail boat's ability to move forward despite heading toward, but not directly into, the wind. A sailboat cannot sail directly into the wind; the closest it can point is called ''close ...

, maneuvering, and close-hauled

A point of sail is a sailing craft's direction of travel under sail in relation to the true wind direction over the surface.

The principal points of sail roughly correspond to 45° segments of a circle, starting with 0° directly into the wind. ...

sailing.

Smaller vessels were originally built for local use, fishing and hauling freight and passengers about the archipelago. By the 1630s, with dwindling income from tobacco exports, largely due to increased competition as the Virginia and newer colonies in the West Indies turned to tobacco cultivation, many of the absentee landowners in England sold their shares to the managers and tenants that occupied them, who turned increasingly to subsistence crops and raising livestock. Bermuda was quickly producing more food than it could consume, and began to sell the excess to the newer colonies that were cultivating tobacco to the exclusion of food crops required for their own subsistence. As the Somers Isles Company's magazine ship would not carry such cargo, Bermudians began constructing their own larger, ocean-going vessels for this purpose. They favoured single-masted designs, more commonly with a gaff-rigged mainsail, although a single larger sail required a larger, more highly skilled, crew than two or more smaller sails.

The sloops were built from Bermuda cedar

''Juniperus bermudiana'' is a species of juniper endemic to Bermuda. This species is most commonly known as Bermuda cedar, but is also referred to as Bermuda juniper ( Bermudians refer to it simply as ''cedar''). Historically, this tree formed w ...

, considered the best wood for shipping, according to Bermuda Governor Isaac Richier in 1691. This is because this cedar was as strong as American oak

An oak is a hardwood tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' of the beech family. They have spirally arranged leaves, often with lobed edges, and a nut called an acorn, borne within a cup. The genus is widely distributed in the Northern Hemisp ...

, yet weighed only two thirds as much. Long lasting due to its resistance to marine organisms, the cedar also had the advantage of being readily used for ship building, and were even planned as such while still growing. Using enslaved and free labor and year-round construction, a 30-ton sloop could be built in three to four months. Bermudians also adopted a reforestation policy, with groves cultivated as long-term crops, and passed down to future generations as dowries or inheritances.

The Bermuda sloop

The Bermuda sloop is a historical type of fore-and-aft rigged single-masted sailing vessel developed on the islands of Bermuda in the 17th century. Such vessels originally had gaff rigs with quadrilateral sails, but evolved to use the Bermuda ri ...

became highly regarded for its speed and manoeuvrability, and was soon adapted for service with the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

. The Bermuda sloop carried dispatches of the victory at Trafalgar Trafalgar most often refers to:

* The Battle of Trafalgar (1805), fought near Cape Trafalgar, Spain

* Trafalgar Square, a public space and tourist attraction in London, England

Trafalgar may also refer to:

Places

* Cape Trafalgar, a headland in ...

, and news of the death of Admiral Nelson

Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte ( – 21 October 1805) was a Royal Navy officer whose leadership, grasp of strategy and unconventional tactics brought about a number of decisive British naval victories during the French ...

, to England.

Privateering

Bermuda was a center of

Bermuda was a center of privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

ing for most of its early history, with Bermuda governors Nathaniel Butler

Nathaniel Butler (born c. 1577, living 1639, date of death unknown) was an English privateer who later served as the colonial governor of Bermuda during the early 17th century. He had built many structures still seen in Bermuda today including ...

and Benjamin Bennett actively encouraging the practice. Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Warwick

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' () "fame, glory, honour, praise, reno ...

(the namesake of Warwick Parish

Warwick Parish is one of the nine parishes of Bermuda. It is named after Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Warwick (1587-1658).

It is located in the central south of the island chain, occupying part of the main island to the southeast of the Great So ...

, was one of the major Adventurers of the Somers Isles Company due primarily to the use he realised could be made of Bermuda as a base for his privateers. Although Bermuda had no merchant or privateering fleet of its own at the time, many Bermudians left farming to work as privateers on English vessels operating from Bermuda, and in 1631 also to settle the short-lived Providence Island colony

The Providence Island colony was established in 1630 by English Puritans on Providence Island (now the Colombian Department of San Andrés and Providencia), about east of the coast of Nicaragua. It was founded and controlle ...

that was dedicated to privateering. During King George's War

King George's War (1744–1748) is the name given to the military operations in North America that formed part of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). It was the third of the four French and Indian Wars. It took place primarily in ...

, according to Jarvis, "privateering became widespread, respectable, and even patriotic." At least fifteen Bermudian privateers operated in the 1740s. State-licensed, privateers had the authority to capture enemy vessels or British vessels engaged in trading contraband

Contraband (from Medieval French ''contrebande'' "smuggling") is any item that, relating to its nature, is illegal to be possessed or sold. It comprises goods that by their nature are considered too dangerous or offensive in the eyes of the leg ...

. Alternatively, a letter of marque

A letter of marque and reprisal () was a Sovereign state, government license in the Age of Sail that authorized a private person, known as a privateer or French corsairs, corsair, to attack and capture vessels of a foreign state at war with t ...

could be issued to a mariner engaged in trade, giving him the authority to seize any vessel they may come across. Vice admiralty court

Vice admiralty courts were juryless courts located in British colonies that were granted jurisdiction over local legal matters related to maritime activities, such as disputes between merchants and seamen.

American Colonies

American maritime act ...

s reviewed the legality of any capture and subsequent distribution of cargo and prizes

A prize is an award to be given to a person or a group of people (such as sporting teams and organizations) to recognize and reward their actions and achievements.

. Crews were a mixture of free and enslaved labor.

Despite close links to the American colonies (and the material aid provided to the continental rebels in the form of a hundred barrels of stolen gunpowder and reportedly numerous Bermudian-built and other ships supplied by Bermudians), Bermudian privateers turned as aggressively on American shipping during the American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

. An American naval captain, ordered to take his ship out of Boston Harbour to eliminate a pair of Bermudian privateering vessels, which had been picking off vessels missed by the Royal Navy, returned frustrated, saying ''the Bermudians sailed their ships two feet for every one of ours''. The only attack on Bermuda during the war was carried out by two South Carolina sloops captained by a pair of Bermudian-born brothers (they damaged a fort and spiked its guns before retreating). It greatly surprised the Americans to discover that the crews of Bermudian privateers included Black slaves, as, with limited manpower, Bermuda had legislated that a part of all Bermudian crews must be made up of Blacks. In fact, when the Bermudian privateer ''Regulator'' was captured, virtually all of her crew were found to be Black slaves. Authorities in Boston offered these men their freedom, but with families in Bermuda all seventy men elected to be treated as Prisoners of War

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

. Sent to New York on the sloop ''Duxbury'', they seized the vessel and sailed it back to Bermuda.

The American War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States declared war on Britain on 18 June 1812. Although peace terms were agreed upon in the D ...

was to be the encore of Bermudian privateering, which had died out after the 1790s, due partly to the buildup of the naval base in Bermuda, which reduced the Admiralty's reliance on privateers in the western Atlantic, and partly to successful American legal suits, and claims for damages pressed against British privateers, a large portion of which were aimed squarely at the Bermudians (unfortunately for the privateers, the British government was trying to woo the United States away from its affiliation with France and so gave a favourable ear to American shipowners). During the course of the American War of 1812, Bermudian privateers were to capture 298 ships (the total captures by ''all'' British naval and privateering vessels between the Great Lakes and the West Indies was 1,593 vessels).

Bermuda and the American War of Independence

On the eve of theAmerican independence

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American Revolutionary War ...

, Bermuda faced competition with its maritime economy. Bermudian emigrants to Virginia helped expand the growth of its merchant fleet, enabling it to exceed Bermuda's by 1762. By the 1770s, Virginia was launching more vessels than Bermuda. Only able to grow enough food to feed the population of 11,000 a few months out of the year, Bermudians relied on food imports from North America, and the consequent higher costs. Many Bermudians had emigrated to Belize to harvest mahogany, or to Georgia, East Florida and the Bahamas islands. Bermudians continued to fish the Grand Banks until forbidden by the Palliser's Act.

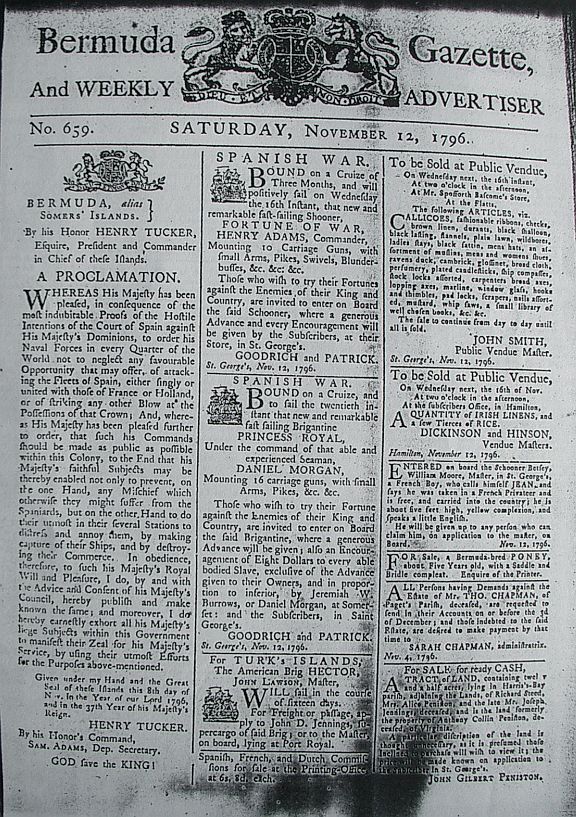

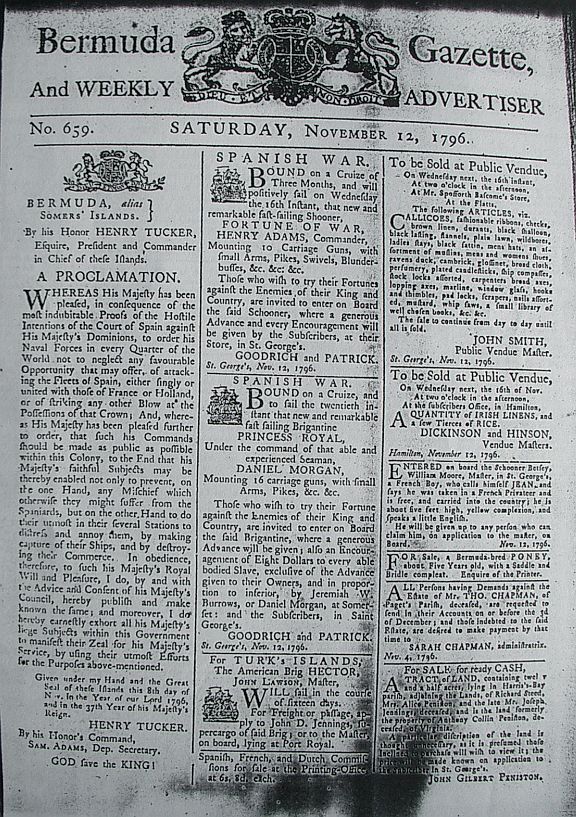

Politically, issues causing protest elsewhere little affected the island, lacking newspapers and an effective local government, which refused to raise public revenue, the island had long relied on smuggling and the circumventing of customs officers. Lacking a permanent garrison made the island immune to the Quartering Acts

The Quartering Acts were several acts of the Parliament of Great Britain which required local authorities in the Thirteen Colonies of British North America to provide British Army personnel in the colonies with housing and food. Each of the Qua ...

. Finally, the island had long been ambivalent to events in New England, whom the Bermudians considered their maritime rivals.

Bermuda's ambivalence changed in September 1774, when the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislature, legislative bodies, with some executive function, for the Thirteen Colonies of British America, Great Britain in North America, and the newly declared United States before, during, and after ...

resolved to ban trade with Great Britain, Ireland, and the West Indies after 10 September 1775. Such an embargo would mean the collapse of their intercolonial commerce, famine and civil unrest. Lacking political channels with Great Britain, the Tucker Family met in May 1775 with eight other parishioners, and resolved to send delegates to the Continental Congress in July, with the goal of an exemption from the ban. Henry Tucker noted a clause in the ban which allowed the exchange of American goods for military supplies. The clause was confirmed by Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

when Tucker met with the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety. Independently, Tucker's sons St. George and Thomas Tudor confirmed this business arrangement with Peyton Randolph

Peyton Randolph (September 10, 1721 – October 22, 1775) was an American politician and planter who was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father of the United States. Born into Virginia's Randolph family of Virginia, wealthies ...

and the Charlestown Committee of Safety, while another Bermudian, Harris, did so with George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

.

Three American vessels, independently operating from Charlestown, Philadelphia and Newport, sailed to Bermuda, and on 14 August 100 barrels of gunpowder were taken from the Bermudian magazine, while the loyalist Governor George James Bruere

Lieutenant-Colonel George James Bruere ( – 10 September 1780) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator who served as governor of Bermuda from 1764 until his death in 1780. Of all Bermuda's governors since 1612, his term of office ...

slept, and loaded onto these vessels. As a consequence, on 2 October the Continental Congress exempted Bermuda from their trade ban, and Bermuda thus acquired a reputation for disloyalty. In late 1775, the British Parliament passed the Prohibitory Act

The Prohibitory Act 1775 ( 16 Geo. 3. c. 5) was British legislation in late 1775 that cut off all trade between the Thirteen Colonies and England and removed the colonies from the King's protection. In essence, it was a declaration of economic ...

to prohibit trade with the American rebelling colonies, and sent HMS ''Scorpion'' to keep watch over the island. The island's forts were stripped of cannon, such that by the end of 1775, all of Bermuda's forts were without cannon, shot and powder. Yet, wartime trade of contraband continued along well established family connections. With 120 vessels by 1775, Bermuda continued to trade with St. Eustatius through 1781, and provided salt to North American ports, despite the presence of hundreds of loyal privateers.

In June 1776, HMS ''Nautilus'' secured the island, followed by in September. Yet, the two British captains seemed more intent on capturing prize money, causing a severe food shortage on the island until the departure of ''Nautilus'' in October. After France's entry into the war in 1778, Sir Henry Clinton refortified and garrisoned the island under the command of Major William Sutherland. As a result, 91 French and American ships were captured in the winter of 1778–1779, bringing the population once again to the brink of starvation. Bermudian trade was severely hampered by the combination of the Royal Navy, the British garrison and loyalist privateers, such that famine struck the island in 1779.

The death of George Bruere in 1780, turned the governorship over to his son, George Bruere Jr., an active loyalist. Under his leadership, smuggling was stopped, and the Bermudian colonial government populated with like-minded loyalists. Even Henry Tucker abandoned trading with the United States, because of the presence of many privateers. Loyalist privateers based in Bermuda captured 114 prizes between 1777 and 1781, while 130 were captured in 1782.

The fallout of the war was that Britain lost all of its continental naval bases between the Maritimes

The Maritimes, also called the Maritime provinces, is a region of Eastern Canada consisting of three provinces: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. The Maritimes had a population of 1,899,324 in 2021, which makes up 5.1% of ...

and Spanish Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

, ultimately the West Indies. This launched Bermuda into a new prominence with the London Government, as its location, near the halfway point from Nova Scotia to the Caribbean, and off the US Atlantic Seaboard, allowed the Royal Navy to operate fully in the area, protecting British trade routes, and potentially commanding the American Atlantic coast in the event of war. The value of Bermuda in the hands of, or serving as a base for, enemies of the United States was shown by the roles it played in the American War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States declared war on Britain on 18 June 1812. Although peace terms were agreed upon in the D ...

and the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. The blockade of the Atlantic ports by the Royal Navy throughout the first war (described in the US as the ''Second War of Independence'') was orchestrated from Bermuda, and the task force that burned Washington DC in 1814 was launched from the colony. During the latter war, Confederate

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

blockade runners

A blockade runner is a merchant vessel used for evading a naval blockade of a port or strait. It is usually light and fast, using stealth and speed rather than confronting the blockaders in order to break the blockade. Blockade runners usual ...

delivered European munitions into Southern harbours from Bermuda, smuggling cotton in the reverse direction.

Consequently, the very features that made Bermuda such a prized base for the Royal Navy (its headquarters in the North Atlantic and West Indies until after the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

), also meant it was perpetually threatened by US invasion, as the US would have liked to both deny the base to an enemy, and use it as a way to extend its defences hundreds of miles out to sea, which would not happen until the Second World War.

As a result of the large regular army garrison established to protect the naval facilities, Bermuda's parliament allowed the Bermudian militia to become defunct after the end of the American war in 1815. More profound changes took place, however. The post American independence buildup of Royal Navy facilities in Bermuda meant the Admiralty placed less reliance on Bermudian privateers in the area. Combined with the effects of the American lawsuits, this meant the activity died out in Bermuda until a brief resurgence during the American War of 1812. With the American continental ports having become foreign territory, the Bermudian merchant shipping trade was seriously injured. During the course of American War of 1812, the Americans had developed other sources for salt, and Bermudians salt trade fell upon hard times. Control of the Turks Islands

The Turks and Caicos Islands (abbreviated TCI; and ) are a British Overseas Territory consisting of the larger Caicos Islands and smaller Turks Islands, two groups of tropical islands in the Lucayan Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean and no ...

ultimately passed into the hands of Bermuda's sworn enemy, the Bahamas

The Bahamas, officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an archipelagic and island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean. It contains 97 per cent of the archipelago's land area and 88 per cent of its population. ...

, in 1819. The shipbuilding industry had caused the deforestation of Bermuda's cedar

Cedar may refer to:

Trees and plants

*''Cedrus'', common English name cedar, an Old-World genus of coniferous trees in the plant family Pinaceae

* Cedar (plant), a list of trees and plants known as cedar

Places United States

* Cedar, Arizona

...

by the start of the 19th century. As ships became larger, increasingly were built from metal, and with the advent of steam power, and with the vastly reduced opportunities Bermudians found for commerce due to US independence and the greater control exerted over their economies by developing territories, Bermuda's shipbuilding industry and maritime trades were slowly strangled.

The chief leg of the Bermudian economy became defence infrastructure. Even after tourism began in the later 19th century, Bermuda remained, in the eyes of London, a base more than a colony, and this led to a change in the political dynamics within Bermuda as its political and economic ties to Britain were strengthened, and its independence on the world stage was diminished. By the end of the 19th century, except for the presence of the naval and military facilities, Bermuda was thought of by non-Bermudians and Bermudians alike as a quiet, rustic backwater, completely at odds with the role it had played in the development of the English-speaking Atlantic world, a change that had begun with American independence.

19th century

Naval and military base

Following the

Following the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

and the loss of Britain's ports in its former continental colonies, Bermuda was also used as a stopover point between Canada and Britain's Caribbean possessions, and assumed a new strategic prominence for the Royal Navy. Hamilton

Hamilton may refer to:

* Alexander Hamilton (1755/1757–1804), first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States

* ''Hamilton'' (musical), a 2015 Broadway musical by Lin-Manuel Miranda

** ''Hamilton'' (al ...

, a centrally located port founded in 1790, became the seat of government in 1815. This was partly resultant from the Royal Navy having invested twelve years, following American independence, in charting Bermuda's reefs. It did this in order to locate the deepwater channel by which shipping might reach the islands in, and at the West of, the Great Sound, which it had begun acquiring with a view to building a naval base

A naval base, navy base, or military port is a military base, where warships and naval ships are docked when they have no mission at sea or need to restock. Ships may also undergo repairs. Some naval bases are temporary homes to aircraft that usu ...

. However, that channel also gave access to Hamilton Harbour.

In 1811, the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

started building the large dockyard on Ireland Island

Ireland Island is the north-westernmost island in the chain which comprises Bermuda. It forms a long finger of land pointing northeastwards from the main island, the last link in a chain which also includes Boaz Island and Somerset Island. ...

, in the west of the chain, to serve as its principal naval base guarding the western Atlantic Ocean shipping lanes. To guard it, the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

built up a large Bermuda Garrison

The Bermuda Garrison was the military establishment maintained on the British Overseas Territory and Imperial fortress of Bermuda by the regular British Army and its local-service militia and voluntary reserves from 1701 to 1957. The garrison ev ...

, and heavily fortified the archipelago.

During the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...