History Of African Americans In Philadelphia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of

Enslaved Africans arrived in the area that became

Enslaved Africans arrived in the area that became  Black people served on both the Loyalist and Patriot sides during the

Black people served on both the Loyalist and Patriot sides during the

. "African American Migration"

Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2021. In 1896, Philadelphia poet, suffragist, and abolitionist Frances Harper helped found the National Association of Colored Women and served as its vice president. By then, she had already had a long career as a published writer, including works like her poem '' Bury Me In a Free Land'', ''Sketches of Southern Life'', and the novel

In 1896, Philadelphia poet, suffragist, and abolitionist Frances Harper helped found the National Association of Colored Women and served as its vice president. By then, she had already had a long career as a published writer, including works like her poem '' Bury Me In a Free Land'', ''Sketches of Southern Life'', and the novel

Aces Museum

honors WWII veterans and their families. Th

Colored Girls Museum

founded by Vashti DuBois, is dedicated to the history of Black women and girls. Th

National Marian Anderson Museum

celebrates the life of the notable opera singer

The African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, established in 1792, was the first house of worship created by and for black people in the United States. While the St. George's United Methodist Church had initially allowed Black worshipers in the main area, its Black worshipers left after the church moved them to the gallery area by 1787."Blacks in Philadelphia." p. 36.

The African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, established in 1792, was the first house of worship created by and for black people in the United States. While the St. George's United Methodist Church had initially allowed Black worshipers in the main area, its Black worshipers left after the church moved them to the gallery area by 1787."Blacks in Philadelphia." p. 36.

''A Gentleman of Color: The Life of James Forten''

New York: Oxford University Press, 2002, p. 16. * Margaretta Forten, suffragist and abolitionistAlexander, Leslie

''Encyclopedia of African American History, Volume 1''

ABC-CLIO (2010), p. 1045. * Grace Douglass, abolitionist * Sarah Mapps Douglass, 19th century educator * Richard Theodore Greener, professor, lawyer, scholar * Charlotte Forten Grimké, 19th century civil rights activist, woman's rights activist * Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, abolitionist, suffragette, poet, author *

online

* Klein, Nicholas J., Erick Guerra, and Michael J. Smart. "The Philadelphia story: Age, race, gender and changing travel trends." ''Journal of Transport Geography'' 69 (2018): 19–25

online

* Lee, Austin Colby Guy. "Allure in the uninhabitable: on affect, space, and Blackness in gentrifying Philadelphia." ''Cultural Geographies'' (2022): 14744740221119154. * Logan, John R., and Benjamin Bellman. "Before the Philadelphia Negro: Residential segregation in a nineteenth-century northern city." ''Social Science History'' 40.4 (2016): 683–706

online

* Loughran, Kevin. "The Philadelphia Negro and the canon of classical urban theory." ''Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race'' 12.2 (2015): 249–267. * Winch, Julie. "Friends, Family and Freedom in Colonial Philadelphia: A Black Slaveowner Settles her Accounts." in ''Quakers and Their Allies in the Abolitionist Cause, 1754-1808'' (Routledge, 2016) pp. 39–53. * Young, Alford A. "The Soul of The Philadelphia Negro and The Souls of Black Folk." in ''The Souls of WEB Du Bois'' (Routledge, 2019) pp. 43–72. {{Philadelphia

African Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa ...

or Black Philadelphians in the city of Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, Pennsylvania has been documented in various sources. People of African descent are currently the largest ethnic group

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, traditions, society, re ...

in Philadelphia. Estimates in 2010 by the U.S. Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau, officially the Bureau of the Census, is a principal agency of the U.S. federal statistical system, responsible for producing data about the American people and economy. The U.S. Census Bureau is part of the U ...

documented the total number of people living in Philadelphia who identified as Black or African American at 644,287, or 42.2% of the city's total population.

Originally arriving in the 17th century as enslaved Africans

Slavery has historically been widespread in Africa. Systems of servitude and slavery were once commonplace in parts of Africa, as they were in much of the rest of the Ancient history, ancient and Post-classical history, medieval world. When t ...

, the population of African Americans in Philadelphia grew during the 18th and 19th centuries to include numerous free Black residents who were active in the abolitionist movement and as conductors in the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was an organized network of secret routes and safe houses used by freedom seekers to escape to the abolitionist Northern United States and Eastern Canada. Enslaved Africans and African Americans escaped from slavery ...

. During the 20th and 21st centuries, Black Philadelphians actively campaigned against discrimination and continued to contribute to Philadelphia's cultural, economic and political life as workers, activists, artists, musicians, and politicians.

Between the 1920s and 1940s, North, West, and South Philadelphia saw an increase of the Black population when white flight

The white flight, also known as white exodus, is the sudden or gradual large-scale migration of white people from areas becoming more racially or ethnoculturally diverse. Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, the terms became popular in the Racism ...

occurred in Philadelphia. More than 50,000 African immigrants live in the Philadelphia metro area. Most of them are from Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

, Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

, Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

, and Liberia

Liberia, officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast–Lib ...

.

History

1639 to 1800

Enslaved Africans arrived in the area that became

Enslaved Africans arrived in the area that became Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

as early as 1639, brought by European settlers. When the slave trade Slave trade may refer to:

* History of slavery - overview of slavery

It may also refer to slave trades in specific countries, areas:

* Al-Andalus slave trade

* Atlantic slave trade

** Brazilian slave trade

** Bristol slave trade

** Danish sl ...

increased due to a shortage of European workers during the 1750s and 1760s, approximately one to five hundred Africans were sent to Philadelphia each year. In 1765, there were roughly fifteen hundred Black Philadelphians; of these, one hundred were free. By the time the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

broke out in 1775, enslaved individuals were one-twelfth of the roughly sixteen thousand people who lived in Philadelphia./

Black people served on both the Loyalist and Patriot sides during the

Black people served on both the Loyalist and Patriot sides during the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

. Two of the individuals supporting the Patriot side were Cyrus Bustill, who worked as a ship's baker during the Revolution and later became a prominent Philadelphia businessman and activist, and James Forten

James Forten (September 2, 1766March 4, 1842) was an American Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist and businessman in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. A free-born African American, he became a sailmaker after the American Revolutionary War. ...

, who served on a privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

at the age of fourteen and became a wealthy sailmaker and abolitionist.

The Pennsylvania Abolition Society

The Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage was the first American abolition society. It was founded April 14, 1775, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and held four meetings. Seventeen of the 24 men who attended initia ...

was founded by white Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

in 1775 and eventually became a biracial organization. In 1780, a policy of gradual emancipation was instituted in Pennsylvania. During this period, enslaved people were freed through manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing slaves by their owners. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that the most wi ...

; others managed to escape or buy their own freedom. By 1783, the free Black community in Philadelphia surpassed one thousand residents, while four hundred residents remained enslaved.

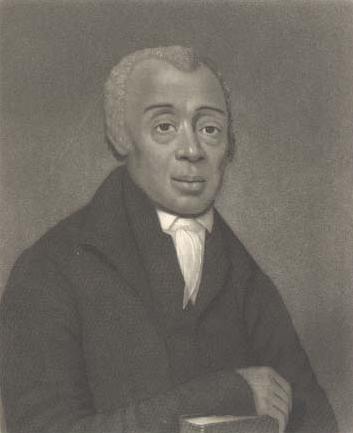

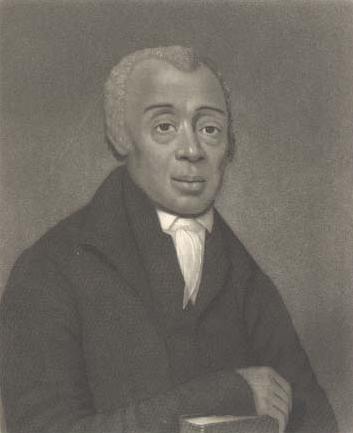

Richard Allen and Absolom Jones founded the Free African Society

The Free African Society (FAS), founded in 1787, was a benevolent organization that held religious services and provided mutual aid for "free Africans and their descendants" in Philadelphia. The Society was founded by Richard Allen and Absalom ...

in 1787, a mutual aid society, and Allen, with his wife Sarah Allen, established the Bethel African Methodist Church in 1794. During the 1793 Philadelphia Yellow Fever Epidemic

During the 1793 yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia, 5,000 or more people were listed in the register of deaths between August 1st and November 9th. The vast majority of them died of yellow fever, making the epidemic in the city of 50,000 peo ...

, Black residents were mistakenly believed to be immune to the disease, so they worked as carriers of the dead and tended to the sick and dying inside their homes. Kidnapping of free Black residents to be sold back into slavery was a risk that continued into the 19th century, especially for children.

The Quakers established a Burying Place For All Free Negroes or People of Color in Byberry Township. This African Burial Ground remains an obscure anomaly, largely forgotten today although it was placed on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places.

Most of the Black population in Philadelphia were living as freemen and women by 1811, although some remained enslaved until the 1840s. The free community was joined by runaways from the South and refugees from the Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution ( or ; ) was a successful insurrection by slave revolt, self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolution was the only known Slave rebellion, slave up ...

.

1800 to Civil War

The growing free Black community was instrumental in making Philadelphia a hotbed ofabolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. ...

by the 1830s. Wealthy Black entrepreneur James Forten

James Forten (September 2, 1766March 4, 1842) was an American Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist and businessman in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. A free-born African American, he became a sailmaker after the American Revolutionary War. ...

gave white abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was an Abolitionism in the United States, American abolitionist, journalist, and reformism (historical), social reformer. He is best known for his widely read anti-slavery newspaper ''The ...

funding so he could start the anti-slavery newspaper '' The Liberator'' and contributed articles to it. Black activists were founders and members of the national biracial group the American Anti-Slavery Society

The American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) was an Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist society in the United States. AASS formed in 1833 in response to the nullification crisis and the failures of existing anti-slavery organizations, ...

, created in Philadelphia in 1833, and the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, created in 1838. In December 1833, after women were excluded from the American Anti-Slavery Society, a group of black and white women, which included Cyril Bustil's daughter Grace Douglass, and James Forten's daughters, Sarah, Harriet and Margaretta launched the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS).

While some African Americans in Philadelphia worked in professional jobs that catered to the Black community like teachers, doctors, ministers, barbers, caterers, and entrepreneurs, most Black Philadelphians at that time worked at physically demanding and low-paying jobs. They competed with working class whites, especially new Irish immigrants, for jobs, which led to racial conflict. In 1834, a race riot broke out at a local tavern that was popular with both black and white Philadelphians. A white mob attacked Black homes, businesses, and churches. In 1838, another white mob attacked Pennsylvania Hall, where black and white abolitionists were meeting, and burned it down. Also in 1838, Pennsylvania's newly ratified constitution officially disfranchised African Americans. In 1842, white mobs again attacked blacks during the Lombard Street Riots.

Despite the risks and racism they encountered, African-Americans continued to come to Philadelphia, since it was the closest major city to the Southern States, where slavery was still legal. In the years leading up to the Civil War, Philadelphia had the largest black population outside the slave states. There were 15,000 black Philadelphians in 1830, 20,000 by 1850, and 22,000 by 1860. Most lived in South Philadelphia near what is today Center City, but there were smaller populations in Northern Liberties, Kensington, and Spring Garden. They came because of Philadelphia's reputation as a thriving political, cultural, and economic center for African Americans.

The city was also a major stop on the Underground Railroad, especially for slaves escaping through Maryland and Delaware. Robert Purvis, president of the biracial Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society from 1845 to 1850, was also chairman of the General Vigilance Committee

A vigilance committee is a group of private citizens who take it upon themselves to administer law and order or exercise power in places where they consider the governmental structures or actions inadequate. Prominent historical examples of vigi ...

from 1852 to 1857, which gave direct aid to fugitive slaves. With his wife Harriet Forten Purvis, he worked as a conductor of the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was an organized network of secret routes and safe houses used by freedom seekers to escape to the abolitionist Northern United States and Eastern Canada. Enslaved Africans and African Americans escaped from slavery ...

. Purvis estimated that from 1831 to 1861, they helped one slave per day achieve freedom, assisting more than 9,000 slaves to escape to the North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

. They used their own house, then located outside the city, in Byberry Township, as a place where fugitives could hide. Purvis built Byberry Hall across the street from his home, on the edge of the Quaker-owned Byberry Friends Meeting campus, to host anti-slavery speakers. It still stands today.

Civil War to 1900

During theCivil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, eleven African American Philadelphia regiments fought for the North, after the passage of the

1862 Second Militia Act allowing blacks to be enlist in the Army.

After the Civil War, African Americans in Philadelphia, including Octavius V. Catto (1839–1871), organized to end segregation of the city's schools and streetcars and regain the right to vote. Their efforts paid off; in 1867, streetcar segregation was ended throughout the state, and legal segregation of schools ended in 1881 (although de facto segregation continued into the 20th century). The Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution gave Pennsylvania Black Americans the right to vote in 1870. But Catto himself was shot and killed while trying to cast his ballot in 1871.

In 1879, painter Henry Ossawa Tanner

Henry Ossawa Tanner (June 21, 1859 – May 25, 1937) was an American artist who spent much of his career in France. He became the first African-American art, African-American painter to gain international acclaim. Tanner moved to Paris, France, ...

enrolled as the first African American student at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. After travels abroad, he would return to Philadelphia in 1893 to paint his most famous work, The Banjo Lesson. Also in 1893, Philadelphia high school student Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller created an art project that was included in The World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago and led to her future success as a multi-disciplinary artist.

The Black population rose to nearly 32,000 in 1880. In 1884, there were approximately 300 black-owned businesses, including the Philadelphia Tribune (started in 1884) and Douglas Hospital (opened in 1895). By 1900, the Black population at 63,000 people, had nearly doubled.Wolfinger, Jame. "African American Migration"

Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

In 1896, Philadelphia poet, suffragist, and abolitionist Frances Harper helped found the National Association of Colored Women and served as its vice president. By then, she had already had a long career as a published writer, including works like her poem '' Bury Me In a Free Land'', ''Sketches of Southern Life'', and the novel

In 1896, Philadelphia poet, suffragist, and abolitionist Frances Harper helped found the National Association of Colored Women and served as its vice president. By then, she had already had a long career as a published writer, including works like her poem '' Bury Me In a Free Land'', ''Sketches of Southern Life'', and the novel Iola Leroy

''Iola Leroy'', ''or Shadows Uplifted'', an 1892 novel by Frances E. W. Harper, is one of the first novels published by an African-American woman. While following what has been termed the "sentimental" conventions of late nineteenth-century wr ...

.

Published in 1899 by the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (Penn or UPenn) is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. One of nine colonial colleges, it was chartered in 1755 through the efforts of f ...

and conducted by W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relativel ...

, '' The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study'' was the first sociological race study of the African American community in the United States. The aim of the social study was to identify "The Negro Problems of Philadelphia," the problems facing black communities not only in Philadelphia, but all over the country as well. The study focused on Philadelphia's Seventh Ward (currently Center City Philadelphia) and the socioeconomic conditions of black churches, businesses and homes within the neighborhood. Using statistics

Statistics (from German language, German: ', "description of a State (polity), state, a country") is the discipline that concerns the collection, organization, analysis, interpretation, and presentation of data. In applying statistics to a s ...

Du Bois created from his survey data, Du Bois compared the occupation, income, education, family size, health, drug use, criminal activity, and suffrage of black and white residents living in the Seventh Ward and to Philadelphia's other wards. Du Bois used statistical evidence to highlight the socioeconomic inequalities the black community faced and make the black community's suffrage known to whites. In turn, he disproved stereotypes surrounding the black community which were cited as the sources of "The Negro Problem."

1900 to 1950s

World War I brought an influx of black migrants from the rural South, who moved to Philadelphia lured by wartime jobs there during the Great Migration. As a result, the black population of Philadelphia doubled again from 63,000 in 1900 to 134,000 in 1920.Most of the new residents came from rural backgrounds and were working poor. Efforts to build new structures to house the workers were insufficient, so African Americans in search of housing moved into existing houses in white neighborhoods, where they encountered hostility and racism. In July 1918, after two black families on Pine Street were attacked by white neighbors who burned household furnishings, G. Grant Williams, editor of thePhiladelphia Tribune

''The Philadelphia Tribune'' is the oldest continuously published African-American newspaper in the United States.

The paper began in 1884 when Christopher J. Perry published its first copy. Throughout its history, ''The Philadelphia Tribune ...

, wrote of the "Pine Street war Zone": "We stand for peace," he said, and advised Black residents to "stand your ground like men," adding “You are not down in Dixie now and you need not fear the ragged rum crazed hellion crew... They may burn your property, but you burn their hides with any weapon that comes handy while they engage in this illegal pastime."

Three weeks later, racial violence erupted again which lasted for several days. During the riot, black homes were destroyed by white mobs, three people were killed, one man was nearly lynched, and a white police officer beat up a black man while he was in the hospital. As a result, African Americans in Philadelphia formed the Colored Protective Association, led by Reverend RR Wright Jr., to "have a permanent organization of protection" to fight discrimination in schools, housing, employment and elsewhere, and to investigate cases of police brutality and police collusion with the white rioters. Their efforts eventually led to the removal of the entire police force by the Director of Public Safety.

In 1925, the artist and printmaker Dox Thrash moved to Philadelphia, where he would spend most of his career. Black Opals, an African American literary magazine associated with the Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African-American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics, and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the ti ...

was published in Philadelphia between spring 1927 and July 1928,. Co-edited by Arthur Huff Fauset and Nellie Rathbone Bright, the magazine's contributors included Mae Virginia Cowdery, Jessie Redmon Fauset

Jessie Redmon Fauset (April 27, 1882 – April 30, 1961) was an editor, poet, essayist, novelist, and educator. Her literary work helped sculpt African-American literature in the 1920s as she focused on portraying a true image of African-Amer ...

, Marita Bonner, and Gwendolyn B. Bennett. Allan Randall Freelon was the magazine's artistic director. Also in the 1920s, John T Gibson became the wealthiest Black entrepreneur in Philadelphia because of his ownership of the popular Standard Standard may refer to:

Symbols

* Colours, standards and guidons, kinds of military signs

* Standard (emblem), a type of a large symbol or emblem used for identification

Norms, conventions or requirements

* Standard (metrology), an object ...

and Dunbar

Dunbar () is a town on the North Sea coast in East Lothian in the south-east of Scotland, approximately east of Edinburgh and from the Anglo–Scottish border, English border north of Berwick-upon-Tweed.

Dunbar is a former royal burgh, and ...

theaters and his management of diverse musical and vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment which began in France in the middle of the 19th century. A ''vaudeville'' was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a drama ...

acts.

The Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

hit Black Philadelphians hard. By 1933, 50% of all Black residents were unemployed. And yet by 1935, African Americans owned 9,855 homes and 787 stores; they were also working in more professional occupations, like physicians ( 200); clergymen ( 250); schoolteachers (553) and policemen ( 219). Their neighborhoods were also becoming more concentrated and more segregated from white neighborhoods.

In 1938, Crystal Bird Fauset became the first female African American elected as state legislator.

Though World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

brought wartime jobs to African Americans, they still faced substandard housing and were not allowed to work on Philadelphia public transit as motormen or conductors until the Federal Government stepped in to pressure the Philadelphia Transportation Company

The Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) was the main public transit operator in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from 1940 to 1968. A private company, PTC was the successor to the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company (PRT), in operation since ...

to open up these jobs to them in 1944. From August 1–6, white transit workers responded by staging a massive sickout strike. After pressure from the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

, the Federal Government sent in 5,000 troops to break the strike and keep public transportation running.

Philadelphia was a center for the mid twentieth century Golden Age of Gospel music

Gospel music is a traditional genre of Christian music and a cornerstone of Christian media. The creation, performance, significance, and even the definition of gospel music vary according to culture and social context. Gospel music is compo ...

, attracting performers like the nationally renowned male quartets the Dixie Hummingbirds

Dixie, also known as Dixieland or Dixie's Land, is a nickname for all or part of the Southern United States. While there is no official definition of this region (and the included areas have shifted over the years), or the extent of the area i ...

and the Sensational Nightingales, as well as Marion Williams

Marion Williams (August 29, 1927 – July 2, 1994) was an American gospel singer.

Early years

Marion Williams was born in Miami, Florida, to a religiously devout mother and musically inclined father. She left school when she was nine ...

before she started her solo career.

1950s to present

The fight against discrimination and segregation in education and employment continued through the 1950s and 60s, with legal battles and protests occurring throughout those years. Cecil B. Moore, president of the local NAACP, was a leading activist during that time, and ReverendLeon Sullivan

Leon Howard Sullivan (October 16, 1922 – April 24, 2001) was a Baptist minister, a civil rights leader and social activist focusing on the creation of job training opportunities for African Americans, a longtime General Motors Board Member, a ...

was instrumental in building Black community and economic power. Marie Hicks successfully organized demonstrations and brought a lawsuit against Girard College to desegregate

Racial integration, or simply integration, includes desegregation (the process of ending systematic racial segregation), leveling barriers to association, creating equal opportunity regardless of race, and the development of a culture that draws ...

that institution. In 1964, a clash between police officers and residents sparked a three-day riot.

The 1960s saw a rise in the Black Power

Black power is a list of political slogans, political slogan and a name which is given to various associated ideologies which aim to achieve self-determination for black people. It is primarily, but not exclusively, used in the United States b ...

movement in Philadelphia. Freedom Library on Ridge Avenue in North Philadelphia, started in 1964 by John Churchville, was where Churchville and other activists gathered to form the Black Power Unity Movement in 1965. Another important center of Black Power was The Church of the Advocate in North Central Philadelphia, whose congregation had become increasingly African American. Father Paul Washington organized the first Black Power rally in 1966; soon there were rallies all over the city, and the third national conference in Philadelphia attracted 2,000 people. The newspaper ''Voice of Umuja'' came out of the conference.

Reggie Schell became the leader of the Philadelphia chapter of the Black Panther Party

The Black Panther Party (originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense) was a Marxism–Leninism, Marxist–Leninist and Black Power movement, black power political organization founded by college students Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newto ...

in 1969. Under his leadership, the party held rallies and created food distribution and education programs throughout the city. Black Power spilled onto college and high school campuses, where students demonstrated for more Black faculty and Black studies classes. In 1970, Philadelphia police raids of three offices of Black Power activists at gunpoint, in which they publicly strip searched activists, made international news for their brutality and united the black community in outrage. Later that year, the Panther sponsored Revolutionary People's Constitutional Convention was held at Temple College and attracted 14,000 people.

Philadelphia soul

Philadelphia soul, sometimes called Philly soul, the Philadelphia sound, Phillysound, or The Sound of Philadelphia (TSOP), is a genre of late 1960s–1970s soul music characterized by funk influences and lush string and horn arrangements. The ...

was a genre of music that arose in the late 1960s and 1970s. Influenced by funk, it was characterized by lush instrumental arrangements with sweeping strings and piercing horns. Fred Wesley described it as "putting the bow tie on funk". It moved funk more towards the disco sound that would become popular in the late 1970s and influenced later Philadelphia-born music makers like singer Jill Scott.

Predominantly Black group MOVE

Move or The Move may refer to:

Brands and enterprises

* Move (company), an American online real estate company

* Move (electronics store), a defunct Australian electronics retailer

* Daihatsu Move, a Japanese car

* PlayStation Move, a motion ...

was founded in 1972 by John Africa. The organization lived in a communal setting in West Philadelphia

West Philadelphia, nicknamed West Philly, is a section of the city of Philadelphia. Although there are no officially defined boundaries, it is generally considered to reach from the western shore of the Schuylkill River, to City Avenue to the n ...

, following philosophies of anarcho-primitivism

Anarcho-primitivism is an anarchist critique of civilization that advocates a return to non-civilized ways of life through deindustrialization, abolition of the division of labor or specialization, abandonment of large-scale organization and all ...

. In 1978, a standoff between MOVE and the Philadelphia police resulted in the death of one police officer and injuries to sixteen officers and firefighters. Nine members were convicted of killing the officer and received life sentence

Life imprisonment is any sentence of imprisonment under which the convicted individual is to remain incarcerated for the rest of their natural life (or until pardoned or commuted to a fixed term). Crimes that result in life imprisonment are c ...

s. In 1985, another conflict resulted in a police helicopter dropping a bomb onto the roof of the MOVE compound, a townhouse

A townhouse, townhome, town house, or town home, is a type of Terraced house, terraced housing. A modern townhouse is often one with a small footprint on multiple floors. In a different British usage, the term originally referred to any type o ...

that was located at 6221 Osage Avenue. The ensuing fire killed six MOVE members, and five of their children, and destroyed sixty-five houses in the neighborhood. The police bombing was strongly condemned. The MOVE survivors later filed a civil suit

A lawsuit is a proceeding by one or more parties (the plaintiff or claimant) against one or more parties (the defendant) in a civil court of law. The archaic term "suit in law" is found in only a small number of laws still in effect today. T ...

against the City of Philadelphia and the PPD and were awarded $1.5 million in a 1996 settlement. Other residents displaced by the destruction of the bombing filed a civil suit against the city and in 2005 were awarded $12.72 million in damages in a jury trial.

In 1982, Mumia Abu-Jamal

Mumia Abu-Jamal (born Wesley Cook; April 24, 1954) is an American political activist and journalist who was convicted of murder and sentenced to death in 1982 for the 1981 murder of Philadelphia Police Department, Philadelphia police officer C ...

, a Philadelphia activist and journalist, was convicted and sentenced to death for the 1981 murder in Philadelphia of police officer Daniel Faulkner. He became widely known while on death row for his writings and commentary on the U.S. criminal justice system. After numerous appeals, his death penalty sentence was overturned by a Federal court, with the prosecution agreeing in 2011 to a sentence of life imprisonment without parole.

Many Philadelphia activists of the mid to late 20th century went on to achieve political power. In 1975, Cecile B. Moore won a seat on the City Council. C. Delores Tucker (1927–2005) became the first black Pennsylvanian appointed to the office of the secretary of state. David P. Richardson (1948–1995) was elected to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives in 1972. In 1984, W. Wilson Goode (b. 1938) became Philadelphia's first black mayor. Goode's administration was followed by black mayors John Street (b. 1943) and Michael Nutter

Michael Anthony Nutter (born June 29, 1957) is an American politician who served as the 98th Mayor of Philadelphia from 2008 to 2016. A member of the Democratic Party, he is also a former member of the Philadelphia City Council from the 4th di ...

(b. 1957).

Many black Philadelphia natives have moved to the suburbs or to Southern cities such as Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, Birmingham, Memphis, San Antonio and Jackson.

Despite the persistence of problems like unemployment and high public school dropout rates, the black community in Philadelphia in the early 21st century continued to attract new residents and contribute its talents and energy to the city. In 2010, its total population stood at 657,343 people or 43.4 percent of Philadelphia's entire population.

Institutions

The African American Museum in Philadelphia is located in Center City. ThAces Museum

honors WWII veterans and their families. Th

Colored Girls Museum

founded by Vashti DuBois, is dedicated to the history of Black women and girls. Th

National Marian Anderson Museum

celebrates the life of the notable opera singer

Marian Anderson

Marian Anderson (February 27, 1897April 8, 1993) was an American contralto. She performed a wide range of music, from opera to spirituals. Anderson performed with renowned orchestras in major concert and recital venues throughout the United S ...

.

The Paul Robeson

Paul Leroy Robeson ( ; April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American bass-baritone concert artist, actor, professional American football, football player, and activist who became famous both for his cultural accomplishments and for h ...

House hosts tours of Robeson's former residence.

Geography

20th century

Circa 1961 Society Hill was a majority black and low income neighborhood, but by 1976 it became gentrified and mostly white with the remaining black population residing in about three or four high-rise apartment buildings with high rents. ''Black Enterprise

''Black Enterprise'' (stylized in all caps) is an American multimedia company. A Black-owned business since the 1970s, its flagship product ''Black Enterprise'' magazine has covered African American businesses with a readership of 3.7 mil ...

'' wrote that a possible reason why wealthier blacks opted not to move to Society Hill was "Unpleasant memories of the old neighborhood". By then many blacks were moving to Wynnefield

__NOTOC__

Wynnefield is a diverse middle-class

neighborhood in West Philadelphia. Its borders are 53rd Street at Jefferson to the south, Philadelphia's Fairmount Park to the east, City Avenue (commonly referred to as "City Line") to the north and ...

, with many originating from Cobbs Creek

Cobbs Creek is an U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed April 1, 2011 tributary of Darby Creek in Delaware County, Pennsylvania, in the United States. It forms an approxima ...

and Overbrook; the new residents of Wynnefield had recently become middle class."Blacks in Philadelphia." p. 44. Also Circa 1976 many African-Americans resided in Powelton Village

Powelton Village is a neighborhood in the West Philadelphia section of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It consists of mostly Victorian architecture, Victorian and Twin home, twin style homes. It is a national historic district that is part of Univer ...

. The majority originated from other states and held professional positions, including artists, graduate students, musicians, teachers, and writers.

21st century

From 1990 to 2010, black residents moved in significant numbers away from the core areas of North and West Philadelphia to Southwest Philadelphia, Overbrook, the Lower Northeast, and elsewhere. The number of Black residents in zip code 19120—which includes the neighborhoods of Olney and Feltonville and abuts Montgomery County -rose from 9,786 in 1990 to 33,209 in 2010, an increase of 239 percent.Religion

The African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, established in 1792, was the first house of worship created by and for black people in the United States. While the St. George's United Methodist Church had initially allowed Black worshipers in the main area, its Black worshipers left after the church moved them to the gallery area by 1787."Blacks in Philadelphia." p. 36.

The African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, established in 1792, was the first house of worship created by and for black people in the United States. While the St. George's United Methodist Church had initially allowed Black worshipers in the main area, its Black worshipers left after the church moved them to the gallery area by 1787."Blacks in Philadelphia." p. 36.

Education

The first school for black males was established by the Pennsylvania Abolition Society in 1794. In 1813, the Society constructed the school building Clarkson Hall on Cherry Street, and in 1854, created Lombard Street Infant School as an aid to working parents. In 1976, 66% of all students of theSchool District of Philadelphia

The School District of Philadelphia (SDP) is the school district that includes all school district-operated State schools, public schools in Philadelphia. Established in 1818, it is the largest school district in Pennsylvania and the eighth-lar ...

were black; this number was proportionally high since whites of all economic backgrounds had a tendency to use private schools. Wealthier blacks chose not to use private schools because their neighborhoods were assigned to higher-quality public schools.

Crime

Black people in Philadelphia are more likely to be charged with felonies than non-blacks. The homicide victim rate for black people in Philadelphia is also higher.Notable residents

18th–19th centuries

* Richard Allen, religious leader, author, journalist * Sarah Allen, abolitionist, underground railroad conductor, missionary * Cyrus Bustill, 18th century entrepreneur, abolitionist and community leader * Jabez Pitt Campbell, abolitionist, and the 8th Bishop of theMethodist Episcopal Church

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself nationally. In 1939, th ...

* Amy Matilda Cassey, activist, and abolitionist

* Joseph Cassey, businessman, abolitionist, and activist

* Octavius Catto

Octavius Valentine Catto (February 22, 1839 – October 10, 1871) was an American educator, intellectual, and civil rights activist. He became principal of male students at the Institute for Colored Youth, where he had also been educated. Born ...

, educator and Civil Rights activist

* Rebecca Cole, doctor and social reformer

* Rebecca Cox Jackson, founder of a Shaker community in Philadelphia

* Nathaniel W. Depee, activist, and abolitionist

* Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

, social reformer, writer, and abolitionist

* Charlotte Vandine Forten, abolitionist

* James Forten

James Forten (September 2, 1766March 4, 1842) was an American Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist and businessman in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. A free-born African American, he became a sailmaker after the American Revolutionary War. ...

, early 19th century businessman and abolitionistWinch, Julie,''A Gentleman of Color: The Life of James Forten''

New York: Oxford University Press, 2002, p. 16. * Margaretta Forten, suffragist and abolitionistAlexander, Leslie

''Encyclopedia of African American History, Volume 1''

ABC-CLIO (2010), p. 1045. * Grace Douglass, abolitionist * Sarah Mapps Douglass, 19th century educator * Richard Theodore Greener, professor, lawyer, scholar * Charlotte Forten Grimké, 19th century civil rights activist, woman's rights activist * Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, abolitionist, suffragette, poet, author *

Jarena Lee

Jarena Lee (February 11, 1783 – February 3, 1864) was the first woman preacher in the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME). Born into a Free Negro, free Black family in New Jersey, Lee asked the founder of the AME church, Richard Allen (bis ...

, preacher

* Absalom Jones

Absalom Jones (November 7, 1746February 13, 1818) was an African-American abolitionist and clergyman who became prominent in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Disappointed at the racial discrimination he experienced in a local Methodist church, he foun ...

, minister, abolitionist, and founder of Free African Society

* John McKee, philanthropist, property owner

* Zedekiah Johnson Purnell, activist, and businessman

* Harriet Forten Purvis, abolitionist

* Robert Purvis, abolitionist, lived most of his life in Philadelphia

* Sarah Louisa Forten Purvis, abolitionist, suffragist

* William B. Purvis, inventor and businessman

* Stephen Smith, businessman, philanthropist, preacher, real estate developer, and abolitionist

* William Whipper

William Whipper (February 22, 1804 – March 9, 1876) was a businessman and abolitionist in the United States. Whipper, an African American, advocated nonviolence and co-founded the American Moral Reform Society, an early African-American aboli ...

, businessman and abolitionist

* Peter Williams Jr., pastor and abolitionist

20th–21st centuries

*Julian Abele

Julian Francis Abele (April 30, 1881April 23, 1950) was a prominent black American architect, and chief designer in the offices of Horace Trumbauer. He contributed to the design of more than 400 buildings, including the Widener Memorial Library ...

, architect

* Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, artist

* Henry Ossawa Tanner

Henry Ossawa Tanner (June 21, 1859 – May 25, 1937) was an American artist who spent much of his career in France. He became the first African-American art, African-American painter to gain international acclaim. Tanner moved to Paris, France, ...

, painter

* Bessie Smith

Bessie Smith (April 15, 1892 – September 26, 1937) was an African-American blues singer widely renowned during the Jazz Age. Nicknamed the "Honorific nicknames in popular music, Empress of the Blues" and formerly Queen of the Blues, she was t ...

, blues singer and actress

* Alain LeRoy Locke, Harlem Renaissance philosopher, journalist, author, scholar

* Raymond Pace Alexander, Lawyer and civil rights activist

* Rex Stewart

Rex William Stewart Jr. (February 22, 1907 – September 7, 1967) was an American jazz cornetist who was a member of the Duke Ellington orchestra.

Career

As a boy he studied piano and violin; most of his career was spent on cornet. Stewart dro ...

, cornetist/trumpeter, journalist, disk jockey, publisher

* Billie Holiday

Billie Holiday (born Eleanora Fagan; April 7, 1915 – July 17, 1959) was an American jazz and swing music singer. Nicknamed "Lady Day" by her friend and music partner, Lester Young, Holiday made significant contributions to jazz music and pop ...

, singer

* Ethel Waters

Ethel Waters (October 31, 1896 – September 1, 1977) was an American singer and actress. Waters frequently performed jazz, swing, and pop music on the Broadway stage and in concerts. She began her career in the 1920s singing blues. Her no ...

, Singer, comedienne and actress

* Marian Anderson

Marian Anderson (February 27, 1897April 8, 1993) was an American contralto. She performed a wide range of music, from opera to spirituals. Anderson performed with renowned orchestras in major concert and recital venues throughout the United S ...

, contralto opera singer

* Crystal Bird Fausett, first African-American female state legislator (elected 1938)

* Kobe Bryant

Kobe Bean Bryant ( ; August 23, 1978 – January 26, 2020) was an American professional basketball player. A shooting guard, he List of NBA players who have spent their entire career with one franchise, spent his entire 20-year career with t ...

, basketball player

* Michael Nutter

Michael Anthony Nutter (born June 29, 1957) is an American politician who served as the 98th Mayor of Philadelphia from 2008 to 2016. A member of the Democratic Party, he is also a former member of the Philadelphia City Council from the 4th di ...

, Mayor of Philadelphia

The mayor of Philadelphia is the chief executive of the government of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

as stipulated by the Charter of the City of Philadelphia. The current mayor of Philadelphia is Cherelle Parker, who is the first woman to hold the ...

* John F. Street, Mayor of Philadelphia

* Luckey Roberts, pianist and composer

* Teddy Pendergrass

Theodore DeReese Pendergrass (March 26, 1950 – January 13, 2010) was an American Soul music, soul and R&B singer and songwriter. He was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Pendergrass lived most of his life in the Philadelphia area, and initial ...

, Singer, songwriter and drummer

* Ed Bradley, News correspondent

* Wilt Chamberlain

Wilton Norman Chamberlain ( ; August21, 1936 – October12, 1999) was an American professional basketball player. Standing tall, he played Center (basketball), center in the National Basketball Association (NBA) for 14 seasons. He was enshrin ...

, basketball player

* Will Smith

Willard Carroll Smith II (born September 25, 1968) is an American actor, rapper, and film producer. Known for his work in both Will Smith filmography, the screen and Will Smith discography, music industries, List of awards and nominations re ...

, rapper, actor

* Guion S. Bluford, astronaut, scientist, pilot

* Kevin Hart

Kevin Darnell Hart (born July 6, 1979) is an American comedian and actor. The accolades he has received include the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor and nominations for two Grammy Awards and four Primetime Emmy Awards.

After winning se ...

, actor, comedian

* Patti LaBelle

Patricia Louise Holte (born May 24, 1944), known professionally as Patti LaBelle, is an American Rhythm and blues, R&B singer and actress. She has been referred to as the "Honorific nicknames in popular music, Godmother of Soul". LaBelle began ...

, singer, actor

* Judith Jamison

Judith Ann Jamison (; May 10, 1943 – November 9, 2024) was an American dancer and choreographer. She danced with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater from 1965 to 1980 and was Ailey's muse. She later returned to be the company's artistic di ...

, ballet dancer, choreographer

* Jill Scott, singer

* Sherman Hemsley

Sherman Alexander Hemsley (February 1, 1938 – July 24, 2012) was an American actor and comedian. He was known for his roles as George Jefferson on the CBS television series ''All in the Family'' (1973–1975; 1978) and ''The Jeffersons'' (1975 ...

, actor

* Solomon Burke

Solomon Vincent McDonald Burke (born James Solomon McDonald, March 21, 1940 – October 10, 2010) was an American singer who shaped the sound of rhythm and blues as one of the founding fathers of soul music in the 1960s. He has been called ...

, singer

* W. Wilson Goode, Mayor of Philadelphia

The mayor of Philadelphia is the chief executive of the government of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

as stipulated by the Charter of the City of Philadelphia. The current mayor of Philadelphia is Cherelle Parker, who is the first woman to hold the ...

* Mumia Abu-Jamal

Mumia Abu-Jamal (born Wesley Cook; April 24, 1954) is an American political activist and journalist who was convicted of murder and sentenced to death in 1982 for the 1981 murder of Philadelphia Police Department, Philadelphia police officer C ...

(born Wesley Cook)

* Bill Cosby

William Henry Cosby Jr. ( ; born July 12, 1937) is an American retired comedian, actor, and media personality. Often cited as a trailblazer for African Americans in the entertainment industry, Cosby was a film, television, and stand-up comedy ...

, Comedian and actor

* Raymond Pace Alexander, lawyer, judge and politician

* Lil Uzi Vert

Symere Bysil Woods ( ; born July 31, 1995), known professionally as Lil Uzi Vert, is an American rapper, singer, and songwriter. Born and raised in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, they gained initial recognition following the release of the commer ...

, rapper

* Eve

Eve is a figure in the Book of Genesis in the Hebrew Bible. According to the origin story, "Creation myths are symbolic stories describing how the universe and its inhabitants came to be. Creation myths develop through oral traditions and there ...

, rapper, singer, actress, and television presenter

* Meek Mill

Robert Rihmeek Williams (born May 6, 1987), known professionally as Meek Mill, is an American rapper. Born and raised in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, he embarked on his career as a battle rapper, and later formed a short-lived rap group the Blo ...

, rapper

* Beanie Sigel

Dwight Equan Grant (born March 6, 1974), better known by his stage name Beanie Sigel, is an American rapper from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He is best known for his association with Jay-Z and his label Roc-A-Fella Records, to which Grant signed ...

, rapper

* Erykah Badu

Erica Abi Wright (born February 26, 1971), known professionally as Erykah Badu, is an American singer and songwriter. Influenced by rhythm and blues, R&B, Soul music, soul, and hip hop, Badu rose to prominence in the late 1990s when her debut al ...

, singer-songwriter

* Questlove

Ahmir K. Thompson (born January 20, 1971), known professionally as Questlove (stylized as ), is an American drummer, record producer, disc jockey, filmmaker, music journalist, and actor. He is the drummer and joint frontman (with Black Thought ...

, musician

* Jazmine Sullivan

Jazmine Marie Sullivan (born April 9, 1987) is an American R&B singer and songwriter. She has won two Grammy Awards, a ''Billboard'' Women in Music Award, and two BET Awards over the course of her career. In 2022, ''Time'' placed her on their ...

, singer

* Freeway

A controlled-access highway is a type of highway that has been designed for high-speed vehicular traffic, with all traffic flow—ingress and egress—regulated. Common English terms are freeway, motorway, and expressway. Other similar terms ...

, rapper

* Grover Washington, Jr., Saxophonist, Musician, Writer, Producer, Arranger, Educator

See also

*Arch Street Friends Meeting House

__NOTOC__

The Arch Street Meeting House, at 320 Arch Street at the corner of 4th Street in the Old City neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is a Meeting House of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers). Built to reflect Friends' t ...

* Vigilant Association of Philadelphia

* Demographics of Philadelphia

* History of the Jews in Philadelphia

* History of Irish Americans in Philadelphia

* History of Italian Americans in Philadelphia

* African Americans in New York City

African Americans constitute one of the longer-running ethnic presences in New York City, home to the largest urban African American population, and the world's largest Black population of any city outside Africa, by a significant margin. As ...

* African Americans in New Jersey

* History of Pennsylvania

The history of Pennsylvania stems back thousands of years when the first indigenous peoples occupied the area of present-day Pennsylvania. In 1681, Pennsylvania became an English colony when William Penn received a royal deed from King Charles ...

* History of Philadelphia

The city of Philadelphia was founded and incorporated in 1682 by William Penn in the Kingdom of England, English Crown Province of Pennsylvania between the Delaware River, Delaware and Schuylkill River, Schuylkill rivers. Before then, the area wa ...

* Hispanics and Latinos in Philadelphia

The Hispanic and Latino population in Philadelphia has seen growth by 27% in the past 10 years and has grown rapidly since the year 2000. As of the 2020 U.S. Census, Philadelphia County

Philadelphia County is the most populous of the 67 co ...

** Cuban migration to Philadelphia

** Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia

* Indians in the Philadelphia metropolitan area

References

* "Blacks in Philadelphia." (November 1976). ''Black Enterprise

''Black Enterprise'' (stylized in all caps) is an American multimedia company. A Black-owned business since the 1970s, its flagship product ''Black Enterprise'' magazine has covered African American businesses with a readership of 3.7 mil ...

''. Start p. 36.

Notes

Further reading

* Abrahams, Roger D. ''Deep down in the jungle: Black American folklore from the streets of Philadelphia'' (Routledge, 2018). * Barnes, Kelli Racine. "Schoolgirl Embroideries and Black Girlhood in Antebellum Philadelphia." ''Journal of Textile Design Research and Practice'' 9.3 (2021): 298–320. * Dirkson, Menika. "“Stop Talking and Act”: The Battle between Tough on Crime Policing and Guardianship of Black Juvenile Gangs in Philadelphia, 1958–1969." ''Journal of Urban History'' (2023): 00961442221142055. * Jacoby, Sara F., et al. "The enduring impact of historical and structural racism on urban violence in Philadelphia." ''Social Science & Medicine'' 199 (2018): 87–95online

* Klein, Nicholas J., Erick Guerra, and Michael J. Smart. "The Philadelphia story: Age, race, gender and changing travel trends." ''Journal of Transport Geography'' 69 (2018): 19–25

online

* Lee, Austin Colby Guy. "Allure in the uninhabitable: on affect, space, and Blackness in gentrifying Philadelphia." ''Cultural Geographies'' (2022): 14744740221119154. * Logan, John R., and Benjamin Bellman. "Before the Philadelphia Negro: Residential segregation in a nineteenth-century northern city." ''Social Science History'' 40.4 (2016): 683–706

online

* Loughran, Kevin. "The Philadelphia Negro and the canon of classical urban theory." ''Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race'' 12.2 (2015): 249–267. * Winch, Julie. "Friends, Family and Freedom in Colonial Philadelphia: A Black Slaveowner Settles her Accounts." in ''Quakers and Their Allies in the Abolitionist Cause, 1754-1808'' (Routledge, 2016) pp. 39–53. * Young, Alford A. "The Soul of The Philadelphia Negro and The Souls of Black Folk." in ''The Souls of WEB Du Bois'' (Routledge, 2019) pp. 43–72. {{Philadelphia

African Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa ...

Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

African Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa ...