Hirohito Ihara on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

,

posthumously

Posthumous may refer to:

* Posthumous award, an award, prize or medal granted after the recipient's death

* Posthumous publication, publishing of creative work after the author's death

* Posthumous (album), ''Posthumous'' (album), by Warne Marsh, 1 ...

honored as , was the 124th

emperor of Japan

The emperor of Japan is the hereditary monarch and head of state of Japan. The emperor is defined by the Constitution of Japan as the symbol of the Japanese state and the unity of the Japanese people, his position deriving from "the will of ...

according to the traditional order of succession, from 25 December 1926 until

his death in 1989. He remains Japan's longest-reigning emperor as well as one of the world's

longest-reigning monarchs. As emperor during the

Shōwa era

The was a historical period of History of Japan, Japanese history corresponding to the reign of Emperor Shōwa (Hirohito) from December 25, 1926, until Death and state funeral of Hirohito, his death on January 7, 1989. It was preceded by the T ...

, Hirohito oversaw the rise of

Japanese militarism

was the ideology in the Empire of Japan which advocated the belief that militarism should dominate the political and social life of the nation, and the belief that the strength of the military is equal to the strength of a nation. It was most ...

,

Japan's expansionism in Asia, the outbreak of the

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War was fought between the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China and the Empire of Japan between 1937 and 1945, following a period of war localized to Manchuria that started in 1931. It is considered part ...

and

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, and the postwar

Japanese economic miracle

The Japanese economic miracle () refers to a period of economic growth in the post–World War II Japan. It generally refers to the period from 1955, around which time the per capita gross national income of the country recovered to pre-war leve ...

.

Hirohito was born during the reign of his paternal grandfather,

Emperor Meiji

, posthumously honored as , was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the List of emperors of Japan, traditional order of succession, reigning from 1867 until his death in 1912. His reign is associated with the Meiji Restoration of 1868, which ...

, as the first child of the Crown Prince Yoshihito and Crown Princess Sadako (later

Emperor Taishō

, posthumously honored as , was the 123rd emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession, reigning from 1912 until his death in 1926. His reign, known as the Taishō era, was characterized by a liberal and democratic shift in ...

and

Empress Teimei

, posthumously honoured as , was the wife of Emperor Taishō and the mother of Emperor Shōwa. Her posthumous name, ''Teimei'', means "enlightened constancy". She was also the paternal grandmother of Emperor Emeritus Akihito, and the paternal ...

). When Emperor Meiji died in 1912, Hirohito's father ascended the throne, and Hirohito was proclaimed

crown prince

A crown prince or hereditary prince is the heir apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The female form of the title, crown princess, is held by a woman who is heir apparent or is married to the heir apparent.

''Crown prince ...

and

heir apparent

An heir apparent is a person who is first in the order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person. A person who is first in the current order of succession but could be displaced by the birth of a more e ...

in 1916. In 1921, he made an official visit to

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

and

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

, marking the first time a Japanese crown prince traveled abroad. Owing to his father's ill health, Hirohito became his

regent

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

that year. In 1924, Hirohito married

Princess Nagako Kuni

Nagako (6 March 190316 June 2000), posthumously honoured as Empress Kōjun, was a member of the Imperial House of Japan, the wife of Hirohito, Emperor Shōwa (Hirohito) and the mother of Daijō Tennō, Emperor Emeritus Akihito. She was Empress o ...

, and they had seven children. He became

emperor

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/grand empress dowager), or a woman who rules ...

upon his father's death in 1926.

As Japan's

head of state

A head of state is the public persona of a sovereign state.#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 "he head of state

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (letter), the fifth letter of the Semitic abjads

* He (pronoun), a pronoun in Modern English

* He (kana), one of the Japanese kana (へ in hiragana and ヘ in katakana)

* Ge (Cyrillic), a Cyrillic letter cal ...

being an embodiment of the State itself or representative of its international persona." The name given to the office of head of sta ...

, Emperor Hirohito presided over the rise of militarism in Japanese politics. In 1931, he made no objection when Japan's

Kwantung Army

The Kwantung Army (Japanese language, Japanese: 関東軍, ''Kantō-gun'') was a Armies of the Imperial Japanese Army, general army of the Imperial Japanese Army from 1919 to 1945.

The Kwantung Army was formed in 1906 as a security force for th ...

staged the

Mukden incident as a pretext for its

invasion of Manchuria. Following the onset of the

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War was fought between the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China and the Empire of Japan between 1937 and 1945, following a period of war localized to Manchuria that started in 1931. It is considered part ...

in 1937, tensions steadily grew between Japan and the United States. Once Hirohito formally sanctioned his government's decision to go to war against the U.S. and its allies on 1 December 1941, the

Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

began one week later with a Japanese

attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

as well as on other U.S. and British colonies in the region. After

atomic bombs were dropped on Japan and the Soviet Union

invaded Japanese-occupied Manchuria, Hirohito called upon his country's forces to surrender in

a radio broadcast on 15 August 1945. The extent of his involvement in military decision-making and wartime culpability remain subjects of historical debate.

Following the

surrender of Japan

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was Hirohito surrender broadcast, announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally Japanese Instrument of Surrender, signed on 2 September 1945, End of World War II in Asia, ending ...

, Emperor Hirohito was not prosecuted for

war crime

A war crime is a violation of the laws of war that gives rise to individual criminal responsibility for actions by combatants in action, such as intentionally killing civilians or intentionally killing prisoners of war, torture, taking hostage ...

s at the

Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial and the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on 29 April 1946 to try leaders of the Empire of Japan for their crimes against peace ...

even though the Japanese had waged war in his name. The head of the

Allied occupation of the country,

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

, believed that a cooperative emperor would facilitate a peaceful occupation and other U.S. postwar objectives. MacArthur therefore excluded any evidence from the tribunal which could have incriminated Hirohito or other members of the royal family. In 1946, Hirohito was pressured by the Allies into

renouncing his divinity. Under

Japan's new constitution drafted by U.S. officials, his role as emperor was redefined in 1947 as "the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people". Upon his death in January 1989, he was succeeded by his eldest son,

Akihito

Akihito (born 23 December 1933) is a member of the Imperial House of Japan who reigned as the 125th emperor of Japan from 1989 until 2019 Japanese imperial transition, his abdication in 2019. The era of his rule was named the Heisei era, Hei ...

.

Early life and education

Hirohito was born on 29 April 1901 at

Tōgū Palace

In Japan, the traditionally does not refer to a single location, but to any residence of the imperial crown prince. As Prince Akishino, the current heir presumptive, is not a direct male descendant of the Emperor and not an imperial crown prince ...

in

Aoyama, Tokyo

is a neighborhood in Tokyo, located in the northwest portion of Minato, Tokyo, Minato Ward. The area is known for its international fashion houses, cafes and restaurants.

refers to the area on the north side of Aoyama-dori (Aoyama Street) betw ...

during the reign of his grandfather,

Emperor Meiji

, posthumously honored as , was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the List of emperors of Japan, traditional order of succession, reigning from 1867 until his death in 1912. His reign is associated with the Meiji Restoration of 1868, which ...

, the first son of 21-year-old Crown Prince Yoshihito (the future

Emperor Taishō

, posthumously honored as , was the 123rd emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession, reigning from 1912 until his death in 1926. His reign, known as the Taishō era, was characterized by a liberal and democratic shift in ...

) and 16-year-old Crown Princess Sadako, the future

Empress Teimei

, posthumously honoured as , was the wife of Emperor Taishō and the mother of Emperor Shōwa. Her posthumous name, ''Teimei'', means "enlightened constancy". She was also the paternal grandmother of Emperor Emeritus Akihito, and the paternal ...

. He was the grandson of Emperor Meiji and

Yanagiwara Naruko

Yanagiwara Naruko (Japanese: 柳原愛子), also known as Sawarabi no Tsubone (26 June 1859 – 16 October 1943), was a Japanese lady-in-waiting of the Imperial House of Japan. A concubine of Emperor Meiji, she was the mother of Emperor Taishō a ...

. His childhood title was Prince Michi.

Ten weeks after he was born, Hirohito was removed from the court and placed in the care of Count

Kawamura Sumiyoshi

Count , was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy. Kawamura's wife Haru was the aunt of Saigō Takamori.

Biography

A native of Satsuma, Kawamura studied navigation at Tokugawa bakufu naval school at Nagasaki, the Nagasaki Naval Training Cent ...

, who raised him as his grandchild. At the age of 3, Hirohito and his brother

Yasuhito

was the second son of Emperor Taishō (Yoshihito) and Empress Teimei (Sadako), a younger brother of Emperor Shōwa (Hirohito) and a general in the Imperial Japanese Army. As a member of the Imperial House of Japan, he was the patron of several ...

were returned to court when Kawamura died – first to the imperial mansion in

Numazu

is a city located in eastern Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 189,486 in 91,986 households, and a population density of 1,014 persons per km2. The total area of the city is .

Geography

Numazu is at the n ...

,

Shizuoka

Shizuoka can refer to:

* Shizuoka Prefecture, a Japanese prefecture

* Shizuoka (city), the capital city of Shizuoka Prefecture

* Shizuoka Airport

* Shizuoka Domain, the name from 1868 to 1871 for Sunpu Domain

was a feudal domain under the Tok ...

, then back to the Aoyama Palace.

In 1908, he began elementary studies at the

Gakushūin

The , or , historically known as the Peers' School, is a Japanese educational institution in Tokyo, originally established as Gakushūjo to educate the children of Japan's nobility. The original school expanded from its original mandate of educ ...

(Peers School). Emperor Mutsuhito, then appointed General

Nogi Maresuke

Count , also known as Kiten, Count Nogi GCB (December 25, 1849September 13, 1912), was a Japanese general in the Imperial Japanese Army and a governor-general of Taiwan. He was one of the commanders during the 1894 capture of Port Arthur from ...

to be the Gakushūin's tenth president as well as the one in-charge on educating his grandson. The main aspect that they focused was on physical education and health, primarily because Hirohito was a sickly child, on par with the impartment or inculcation of values such as frugality, patience, manliness, self-control, and devotion to the duty at hand.

During 1912, at the age of 11, Hirohito was commissioned into the

Imperial Japanese Army

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA; , ''Dai-Nippon Teikoku Rikugun'', "Army of the Greater Japanese Empire") was the principal ground force of the Empire of Japan from 1871 to 1945. It played a central role in Japan’s rapid modernization during th ...

as a Second Lieutenant and in the

Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, Potsdam Declaration, when it was dissolved followin ...

as an Ensign. He was also bestowed with the Grand Cordon of the

Order of the Chrysanthemum

is Japan's highest Order (decoration), order. The Grand Cordon of the Order was established in 1876 by Emperor Meiji of Japan; the Collar of the Order was added on 4 January 1888. Unlike European counterparts, the order may be Posthumous award, ...

. When his grandfather,

Emperor Meiji

, posthumously honored as , was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the List of emperors of Japan, traditional order of succession, reigning from 1867 until his death in 1912. His reign is associated with the Meiji Restoration of 1868, which ...

died on 30 July 1912,

Yoshihito assumed the throne and his eldest son, Hirohito became

heir apparent

An heir apparent is a person who is first in the order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person. A person who is first in the current order of succession but could be displaced by the birth of a more e ...

.

After learning about the death of his instructor, General Nogi, he along with his brothers were reportedly overcome with emotions. He would later acknowledge the lasting influence of Nogi in his life. At that time he was still two years away from completing primary school, henceforth his education was compensated by Fleet Admiral Togo Heihachiro and Naval Captain Ogasawara Naganari, wherein later on, would become his major opponents with regards to his national defense policy.

Shiratori Kurakichi, one of his middle-school instructors, was one of the personalities who deeply influenced the life of Hirohito. Kurakichi was a trained historian from

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, imbibing the positivist historiographic trend by

Leopold von Ranke

Leopold von Ranke (21 December 1795 – 23 May 1886) was a German historian and a founder of modern source-based history. He was able to implement the seminar teaching method in his classroom and focused on archival research and the analysis of ...

. He was the one who inculcated in the mind of the young Hirohito that there is a connection between the divine origin of the imperial line and the aspiration of linking it to the myth of the racial superiority and homogeneity of the Japanese. The emperors were often a driving force in the modernization of their country. He taught Hirohito that the

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

was created and governed through diplomatic actions (taking into accounts the interests of other nations benevolently and justly).

Crown Prince era

On 2 November 1916, Hirohito was formally proclaimed crown prince and

heir apparent

An heir apparent is a person who is first in the order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person. A person who is first in the current order of succession but could be displaced by the birth of a more e ...

. An

investiture

Investiture (from the Latin preposition ''in'' and verb ''vestire'', "dress" from ''vestis'' "robe") is a formal installation or ceremony that a person undergoes, often related to membership in Christian religious institutes as well as Christian kn ...

ceremony was not required to confirm this status.

Overseas travel

From 3 March to 3 September 1921 (Taisho 10), the Crown Prince made official visits to the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

,

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, the

Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

,

Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

,

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

,

Vatican City

Vatican City, officially the Vatican City State (; ), is a Landlocked country, landlocked sovereign state and city-state; it is enclaved within Rome, the capital city of Italy and Bishop of Rome, seat of the Catholic Church. It became inde ...

and

Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

(then a protectorate of the British Empire). This was the first visit to Western Europe by the Crown Prince. Despite strong opposition in Japan, this was realized by the efforts of elder Japanese statesmen (

Genrō

was an unofficial designation given to a generation of elder Japanese statesmen, all born in the 1830s and 1840s, who served as informal extraconstitutional advisors to the emperor during the Meiji, Taishō, and early Shōwa eras of Japan ...

) such as

Yamagata Aritomo

Prince was a Japanese politician and general who served as prime minister of Japan from 1889 to 1891, and from 1898 to 1900. He was also a leading member of the '' genrō'', a group of senior courtiers and statesmen who dominated the politics ...

and

Saionji Kinmochi

Kazoku, Prince was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan, prime minister of Japan from 1906 to 1908, and from 1911 to 1912. As the last surviving member of the ''genrō'', the group of senior statesmen who had directed pol ...

.

The departure of Prince Hirohito was widely reported in newspapers. The

Japanese battleship ''Katori'' was used, and departed from

Yokohama

is the List of cities in Japan, second-largest city in Japan by population as well as by area, and the country's most populous Municipalities of Japan, municipality. It is the capital and most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a popu ...

, sailed to

Naha

is the Cities of Japan, capital city of Okinawa Prefecture, the southernmost prefecture of Japan. As of 1 June 2019, the city has an estimated population of 317,405 and a population density of 7,939 people per km2 (20,562 persons per sq. mi.). ...

,

Hong Kong

Hong Kong)., Legally Hong Kong, China in international treaties and organizations. is a special administrative region of China. With 7.5 million residents in a territory, Hong Kong is the fourth most densely populated region in the wor ...

,

Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

,

Colombo

Colombo, ( ; , ; , ), is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. The Colombo metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of 5.6 million, and 752,993 within the municipal limits. It is the ...

,

Suez

Suez (, , , ) is a Port#Seaport, seaport city with a population of about 800,000 in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez on the Red Sea, near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal. It is the capital and largest c ...

,

Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

, and

Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

. In April, Hirohito was present in Malta for the opening of the Maltese Parliament. After sailing for two months, the Katori arrived in

Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

on 9 May, on the same day reaching the British capital,

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

. Hirohito was welcomed in the UK as a partner of the

Anglo-Japanese Alliance

The was an alliance between the United Kingdom and the Empire of Japan which was effective from 1902 to 1923. The treaty creating the alliance was signed at Lansdowne House in London on 30 January 1902 by British foreign secretary Lord Lans ...

and met with

King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

George was born during the reign of his pa ...

and Prime Minister

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

.

That evening, a banquet was held at

Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

, where Hirohito met with George V and

Prince Arthur of Connaught

Prince Arthur of Connaught (Arthur Frederick Patrick Albert; 13 January 1883 – 12 September 1938) was a British military officer and a grandson of Queen Victoria. He served as Governor-General of the Union of South Africa from 20 November 19 ...

. George V said that he treated his father like Hirohito, who was nervous in an unfamiliar foreign country, and that relieved his tension. The next day, he met

Prince Edward (the future Edward VIII) at

Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a List of British royal residences, royal residence at Windsor, Berkshire, Windsor in the English county of Berkshire, about west of central London. It is strongly associated with the Kingdom of England, English and succee ...

, and a banquet was held every day thereafter. In London, he toured the

British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

, the

Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

, the

Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the Kingdom of England, English Government's banker and debt manager, and still one ...

,

Lloyd's Marine Insurance,

Oxford University

The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the second-oldest continuously operating u ...

, Army University, and the

Naval War College

The Naval War College (NWC or NAVWARCOL) is the staff college and "Home of Thought" for the United States Navy at Naval Station Newport in Newport, Rhode Island. The NWC educates and develops leaders, supports defining the future Navy and associa ...

. He also enjoyed theater at the

New Oxford Theatre

Oxford Music Hall was a music hall located in City of Westminster, Westminster, London, at the corner of Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road. It was established on the site of a former public house, the Boar and Castle, by Charles Morton (im ...

and the Delhi Theatre.

At the

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

, he listened to Professor

J. R. Tanner's lecture on "Relationship between the British Royal Family and its People", and was awarded an

honorary doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or '' ad hon ...

degree.

He visited

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

, Scotland, from 19 to 20 May, and was also awarded an Honorary Doctor of Laws at the

University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

. He stayed at the residence of

John Stewart-Murray, 8th Duke of Atholl

John George Stewart-Murray, 8th Duke of Atholl, (15 December 1871 – 16 March 1942), styled Marquess of Tullibardine until 1917, was a British soldier and Unionist politician.

Early life

Styled Marquess of Tullibardine from birth, he was bor ...

, for three days. On his stay with Stuart-Murray, the prince was quoted as saying, "The rise of

Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

won't happen if you live a simple life like Duke Athol."

In Italy, he met with King

Vittorio Emanuele III

Victor Emmanuel III (; 11 November 1869 – 28 December 1947) was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. A member of the House of Savoy, he also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia from 1936 to 1941 and King of the Albania ...

and others, attended official international banquets, and visited places such as the fierce battlefields of

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

.

Regency

After returning (from Europe) to Japan, Hirohito became

Regent

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

of Japan (

''Sesshō'') on 25 November 1921, in place of his ailing father, who was affected by mental illness. In 1923 he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel in the army and Commander in the navy, and army Colonel and Navy Captain in 1925.

Visit of colonial Taiwan

Over 12 days in April 1923, Hirohito visited Taiwan, which had been a

Japanese colony since 1895. This was a voyage his father, the then Crown Prince

Yoshihito had planned in 1911 but never completed.

It was widely reported in Taiwanese newspapers that famous high-end restaurants served typical Chinese luxury dishes for the Prince, such as swallow's nest and shark fin, as Taiwanese cuisine. This was the first time an Emperor or a Crown Prince has ever eaten local cuisine on a colony, or had foreign dishes other than Western cuisine abroad, thus exceptional preparations were required: The eight chefs and other cooking staff were purified for a week (through fasting and ritual bathing) before the cooking of the feast could begin. This tasting of “Taiwanese cuisine” of the Prince Regent as part of an integration ceremony of incorporating the colony into the empire, which can be seen as the context and purpose of Hirohito's Taiwanese visit.

Having visited several sites outside of Taipei, Hirohito returned to the capital on the 24th and on 25 April, just one day before his departure, he visited the Beitou hotspring district of Taipei and its oldest facility. The original structure had been built in 1913 in the style of a traditional Japanese bathhouse. However, in anticipation of Hirohito's visit an additional residential wing was added to the earlier building, this time in the style of an Edwardian country house. The new building was subsequently opened to the public and was deemed the largest public bathhouse in the Japanese Empire.

Crown Prince Hirohito was a student of science, and he had heard that Beitou Creek was one of only two hot springs in the world that contained a rare radioactive mineral. So, he decided to walk into the creek to investigate.

Naturally, concerned for a royal family member's safety, his entourage scurried around, seeking flat rocks to use as stepping stones. After that, these stones were carefully mounted and given the official name: “His Imperial Highness Crown Prince of Japan's Stepping Stones for River Crossing,” with a stele alongside to tell the story.

Crown Prince Hirohito handed his Imperial Notice to Governor-General

Den Kenjiro

Den may refer to:

* Den (room), a small room in a house

* Maternity den, a lair where an animal gives birth

Media and entertainment

* ''Den'' (album), 2012, by Kreidler

* Den (''Battle Angel Alita''), a character in the ''Battle Angel Alita' ...

and departed from

Keelung

Keelung ( ; zh, p=Jīlóng, c=基隆, poj=Ke-lâng), Chilung or Jilong ( ; ), officially known as Keelung City, is a major port city in northeastern Taiwan. The city is part of the Taipei–Keelung metropolitan area with neighboring New Ta ...

on 26 April 1923.

Earthquake and assassination attempt

The

Great Kantō earthquake

Great may refer to:

Descriptions or measurements

* Great, a relative measurement in physical space, see Size

* Greatness, being divine, majestic, superior, majestic, or transcendent

People

* List of people known as "the Great"

* Artel Great (bo ...

devastated Tokyo on 1 September 1923, killing some 100,000 people and leveling vast areas. The city could be rebuilt drawing on the then massive timber reserves of Taiwan. In the aftermath of the tragical disaster, the military authorities saw an opportunity to annihilate the communist movement in Japan. During the

Kantō Massacre

The was a mass murder in the Kantō region of Japan committed in the aftermath of the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake. With the explicit and implicit approval of parts of the Japanese government, the Japanese military, police, and vigilantes mu ...

an estimated 6000 people, mainly ethnic Koreans, were annihilated. The backlash culminated in an assassination attempt by

Daisuke Namba

Daisuke Nanba (難波 大助, ''Nanba Daisuke,'' November 7, 1899 – November 15, 1924) was a Japanese student and member of the Japanese Communist Party who tried to assassinate the Crown Prince Regent Hirohito in the Toranomon incident on ...

on the Prince Regent on 27 December 1923 in the so-called

Toranomon incident, but the attempt failed.

During interrogation, the failed assassin claimed to be a

communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

and was executed.

Marriage

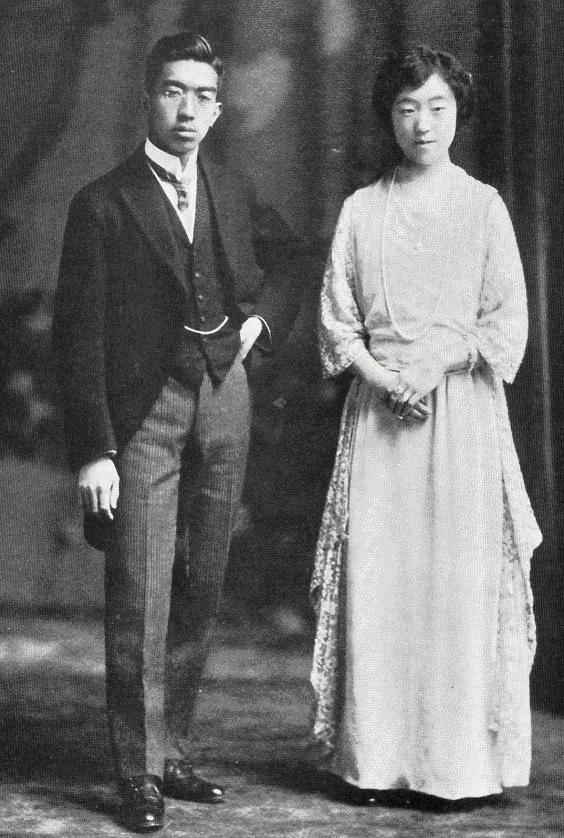

Prince Hirohito married his distant cousin

Princess Nagako Kuni

Nagako (6 March 190316 June 2000), posthumously honoured as Empress Kōjun, was a member of the Imperial House of Japan, the wife of Hirohito, Emperor Shōwa (Hirohito) and the mother of Daijō Tennō, Emperor Emeritus Akihito. She was Empress o ...

, the eldest daughter of

Prince Kuniyoshi Kuni

was a member of the Japanese imperial family and a field marshal in the Imperial Japanese Army during the Meiji and Taishō periods. He was the father of Empress Kōjun (who in turn was the consort of the Emperor Hirohito), and therefore, the ...

, on 26 January 1924. They had two sons and five daughters

(see

Issue

Issue or issues may refer to:

Publishing

* ''Issue'' (company), a mobile publishing company

* ''Issue'' (magazine), a monthly Korean comics anthology magazine

* Issue (postal service), a stamp or a series of stamps released to the public

* '' ...

).

The daughters who lived to adulthood left the imperial family as a result of the American reforms of the Japanese imperial household in October 1947 (in the case of Princess Shigeko) or under the terms of the

Imperial Household Law

is a Japanese law that governs the line of imperial succession, the membership of the imperial family, and several other matters pertaining to the administration of the Imperial Household.

In 2017, the National Diet changed the law to enable ...

at the moment of their subsequent marriages (in the cases of Princesses Kazuko, Atsuko, and Takako).

Reign

Accession

On 25 December 1926, Yoshihito died and Hirohito became emperor. The Crown Prince was said to have received the succession (''senso'').

[Varley, H. Paul, ed. (1980). '']Jinnō Shōtōki

is a Japanese historical book written by Kitabatake Chikafusa. The work sought both to clarify the genesis and potential consequences of a contemporary crisis in Japanese politics, and to dispel or at least ameliorate the prevailing disorder ...

("A Chronicle of Gods and Sovereigns: Jinnō Shōtōki of Kitabatake Chikafusa" translated by H. Paul Varley)'', p. 44. distinct act of ''senso'' is unrecognized prior to Emperor Tenji; and all sovereigns except Empress Jitō">Jitō

were medieval territory stewards in Japan, especially in the Kamakura and Muromachi shogunates. Appointed by the shōgun, ''jitō'' managed manors, including national holdings governed by the '' kokushi'' or provincial governor. There were als ...

, Yōzei, Go-Toba, and Emperor Fushimi, Fushimi have ''senso'' and ''sokui'' in the same year until the reign of Go-Murakami;] The Taishō era's end and the

Shōwa era

The was a historical period of History of Japan, Japanese history corresponding to the reign of Emperor Shōwa (Hirohito) from December 25, 1926, until Death and state funeral of Hirohito, his death on January 7, 1989. It was preceded by the T ...

's beginning (Enlightened Peace) were proclaimed. The deceased Emperor was posthumously renamed

Emperor Taishō

, posthumously honored as , was the 123rd emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession, reigning from 1912 until his death in 1926. His reign, known as the Taishō era, was characterized by a liberal and democratic shift in ...

within days. Following Japanese custom, the new Emperor was

never referred to by his given name but rather was referred to simply as "His Majesty the Emperor" which may be shortened to "His Majesty." In writing, the Emperor was also referred to formally as "The Reigning Emperor."

In November 1928, Hirohito's accession was confirmed in

ceremonies

A ceremony (, ) is a unified ritualistic event with a purpose, usually consisting of a number of artistic components, performed on a special occasion.

The word may be of Etruscan origin, via the Latin .

Religious and civil (secular) ceremoni ...

(''sokui'')

which are conventionally identified as "enthronement" and "coronation" (''Shōwa no tairei-shiki''); but this formal event would have been more accurately described as a public confirmation that he possessed the Japanese

Imperial Regalia

The Imperial Regalia, also called Imperial Insignia (in German ''Reichskleinodien'', ''Reichsinsignien'' or ''Reichsschatz''), are regalia of the Holy Roman Emperor. The most important parts are the Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire, C ...

, also called the

Three Sacred Treasures

The are the imperial regalia of Japan and consist of the sword , the mirror , and the jewel . They represent the three primary virtues: valour (the sword), wisdom (the mirror), and benevolence (the jewel). , which have been handed down through the centuries. However, his enthronement events were planned and staged under the economic conditions of a recession whereas the 55th Imperial Diet unanimously passed $7,360,000 for the festivities.

Early reign

The first part of Hirohito's reign took place against a background of

financial crisis

A financial crisis is any of a broad variety of situations in which some financial assets suddenly lose a large part of their nominal value. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many financial crises were associated with Bank run#Systemic banki ...

and increasing military power within the government through both legal and extralegal means. The

Imperial Japanese Army

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA; , ''Dai-Nippon Teikoku Rikugun'', "Army of the Greater Japanese Empire") was the principal ground force of the Empire of Japan from 1871 to 1945. It played a central role in Japan’s rapid modernization during th ...

and

Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, Potsdam Declaration, when it was dissolved followin ...

held

veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president (government title), president or monarch vetoes a bill (law), bill to stop it from becoming statutory law, law. In many countries, veto powe ...

power over the formation of cabinets since 1900. Between 1921 and 1944, there were 64 separate incidents of political violence.

Hirohito narrowly escaped assassination by a hand

grenade

A grenade is a small explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a Shell (projectile), shell (explosive projectile) shot from the muzzle of a rifle (as a rifle grenade) or a grenade launcher. A mod ...

thrown by a

Korean independence activist,

Lee Bong-chang

Lee Bong-chang (; August 10, 1900 – October 10, 1932) was a Korean independence activist. In Korea, he is remembered as a martyr due to his participation in the 1932 Sakuradamon incident, in which he attempted to assassinate the Japanese Emp ...

, in Tokyo on 9 January 1932, in the

Sakuradamon Incident.

Another notable case was the assassination of moderate

Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Inukai Tsuyoshi

Inukai Tsuyoshi (, 4 June 1855 – 15 May 1932) was a Japanese statesman who was Prime Minister of Japan, prime minister of Japan from 1931 to his assassination in 1932. At the age of 76, Inukai was Japan's second oldest serving prime minister, ...

in 1932, marking the end of

civilian control of the military

Civil control of the military is a doctrine in military science, military and political science that places ultimate command responsibility, responsibility for a country's Grand strategy, strategic decision-making in the hands of the state's c ...

. The

February 26 incident, an attempted

coup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

, followed in February 1936. It was carried out by junior Army officers of the ''

Kōdōha

The ''Kōdōha'' or was a political faction in the Imperial Japanese Army active in the 1920s and 1930s. The ''Kōdōha'' sought to establish a military government that promoted totalitarian, militaristic and aggressive imperialist ideals, and ...

'' faction who had the sympathy of many high-ranking officers including

Yasuhito, Prince Chichibu

was the second son of Emperor Taishō (Yoshihito) and Empress Teimei (Sadako), a younger brother of Emperor Shōwa (Hirohito) and a general in the Imperial Japanese Army. As a member of the Imperial House of Japan, he was the patron of seve ...

, one of Hirohito's brothers. This revolt was occasioned by a loss of political support by the militarist faction in

Diet

Diet may refer to:

Food

* Diet (nutrition), the sum of the food consumed by an organism or group

* Dieting, the deliberate selection of food to control body weight or nutrient intake

** Diet food, foods that aid in creating a diet for weight loss ...

elections. The coup resulted in the murders of several high government and Army officials.

When Chief

Aide-de-camp Shigeru Honjō

General Baron was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during the early period of the Second Sino-Japanese War. He was considered an ardent follower of Sadao Araki's doctrines.

Biography

Honjō was born into a farming family in Hyōgo prefe ...

informed him of the revolt, Hirohito immediately ordered that it be put down and referred to the officers as "rebels" (''bōto''). Shortly thereafter, he ordered

Army Minister Yoshiyuki Kawashima

was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army and Army Minister in the 1930s.

Biography

Kawashima was a native of Ehime prefecture. He graduated from the 10th class of the Imperial Japanese Army Academy in 1898 (where one of his classmates was Sa ...

to suppress the rebellion within the hour. He asked for reports from Honjō every 30 minutes. The next day, when told by Honjō that the high command had made little progress in quashing the rebels, the Emperor told him "I Myself, will lead the

Konoe Division and subdue them." The rebellion was suppressed following his orders on

29 February

February 29 is a '' leap day'' (or "leap year day")—an intercalary date added periodically to create leap years in the Julian and Gregorian calendars. It is the 60th day of a leap year in both Julian and Gregorian calendars, and 306 day ...

.

Second Sino-Japanese War

Beginning from the Mukden Incident in 1931 in which Japan staged a False flag, false flag operation and made a false accusation against Chinese dissidents as a pretext to invade Manchuria, Japan occupied Chinese territories and established Puppet state, puppet governments. Such aggression was recommended to Hirohito by his chiefs of staff and prime minister Fumimaro Konoe; Hirohito did not voice objection to the invasion of China.

A diary by chamberlain Kuraji Ogura says that he was reluctant to start war against China in 1937 because they had underestimated China's military strength and Japan should be cautious in its strategy. In this regard, Ogura writes that Hirohito stated "once you start (a war), it cannot easily be stopped in the middle ... What's important is when to end the war" and "one should be cautious in starting a war, but once begun, it should be carried out thoroughly."

Nonetheless, according to Herbert Bix, Hirohito's main concern seems to have been the possibility of an attack by the Soviet Union given his questions to his chief of staff, Prince Kan'in Kotohito, and army minister, Hajime Sugiyama, about the time it could take to crush Chinese resistance and how could they prepare for the eventuality of a Soviet incursion. Based on Bix's findings, Hirohito was displeased by Prince Kan'in's evasive responses about the substance of such contingency plans but nevertheless still approved the decision to move troops to North China.

According to Akira Fujiwara, Hirohito endorsed the policy of qualifying the invasion of China as an "incident" instead of a "war"; therefore, he did not issue any notice to observe international law in this conflict (unlike what his predecessors did in previous conflicts officially recognized by Japan as wars), and the Deputy Minister of the Japanese Army instructed the chief of staff of Japanese China Garrison Army on 5 August not to use the term "prisoners of war" for Chinese captives. This instruction led to the removal of the constraints of international law on the treatment of Chinese prisoners. The works of Yoshiaki Yoshimi and Seiya Matsuno show that Hirohito also authorized, by specific orders (''rinsanmei''), the use of chemical weapons against the Chinese.

Later in his life, Hirohito looked back on his decision to give the go-ahead to wage a 'defensive' war against China and opined that his foremost priority was not to wage war with China but to prepare for a war with the Soviet Union, as his army had reassured him that the China war would end within three months, but that decision of his had haunted him since he forgot that the Japanese forces in China were drastically fewer than that of the Chinese, hence the shortsightedness of his perspective was evident.

On 1 December 1937, Hirohito had given formal instruction to General Iwane Matsui to capture and occupy the enemy capital of Nanking. He was very eager to fight this battle since he and his council firmly believed that all it would take is a one huge blow to bring forth the surrender of Chiang Kai-shek. He even gave an Imperial Rescript to Iwane when he returned to Tokyo a year later, despite the brutality that his officers had inflicted on the Chinese populace in Nanking; thus Hirohito had seemingly turned a blind eye to and condoned these monstrosities.

During the Battle of Wuhan, invasion of Wuhan, from August to October 1938, Hirohito authorized the use of toxic gas on 375 separate occasions, despite the resolution adopted by the League of Nations on 14 May condemning Japanese use of chemical weapons.

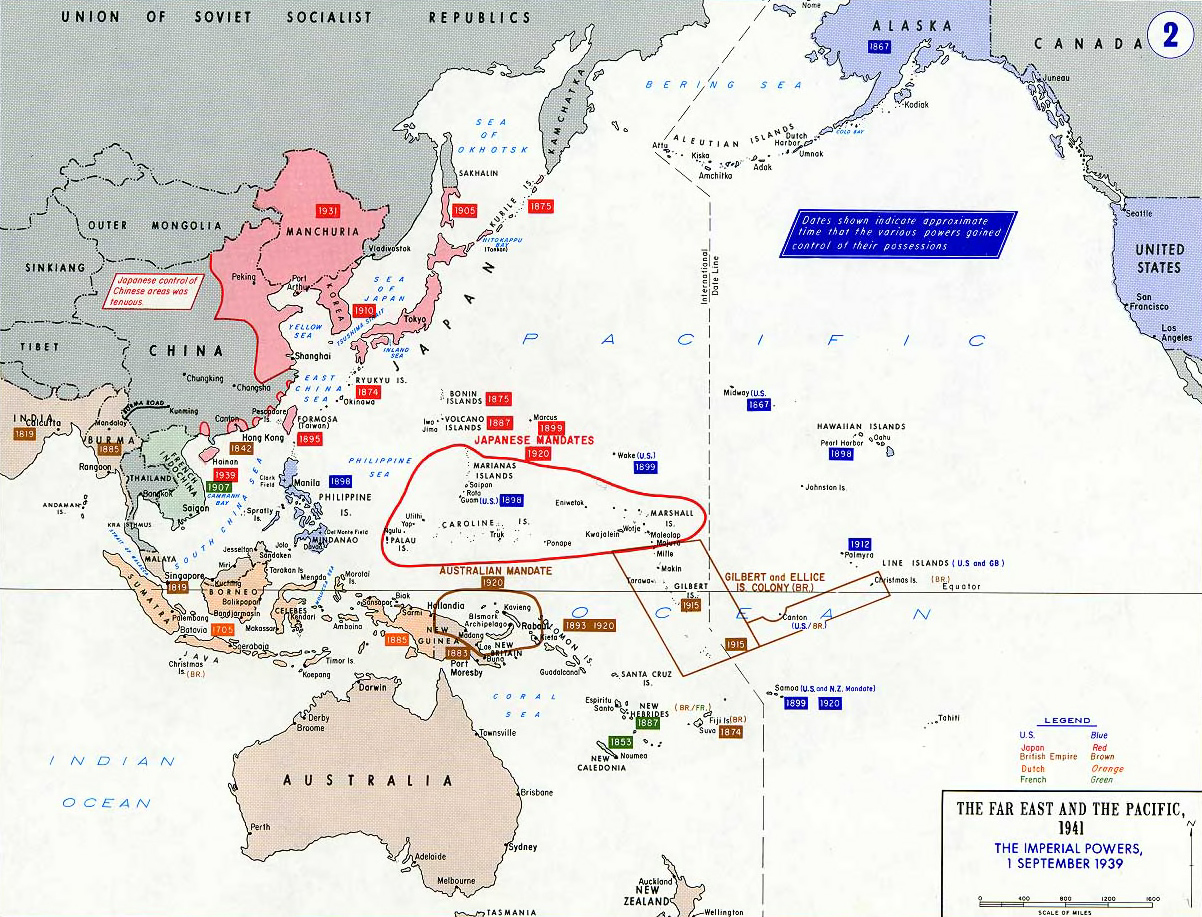

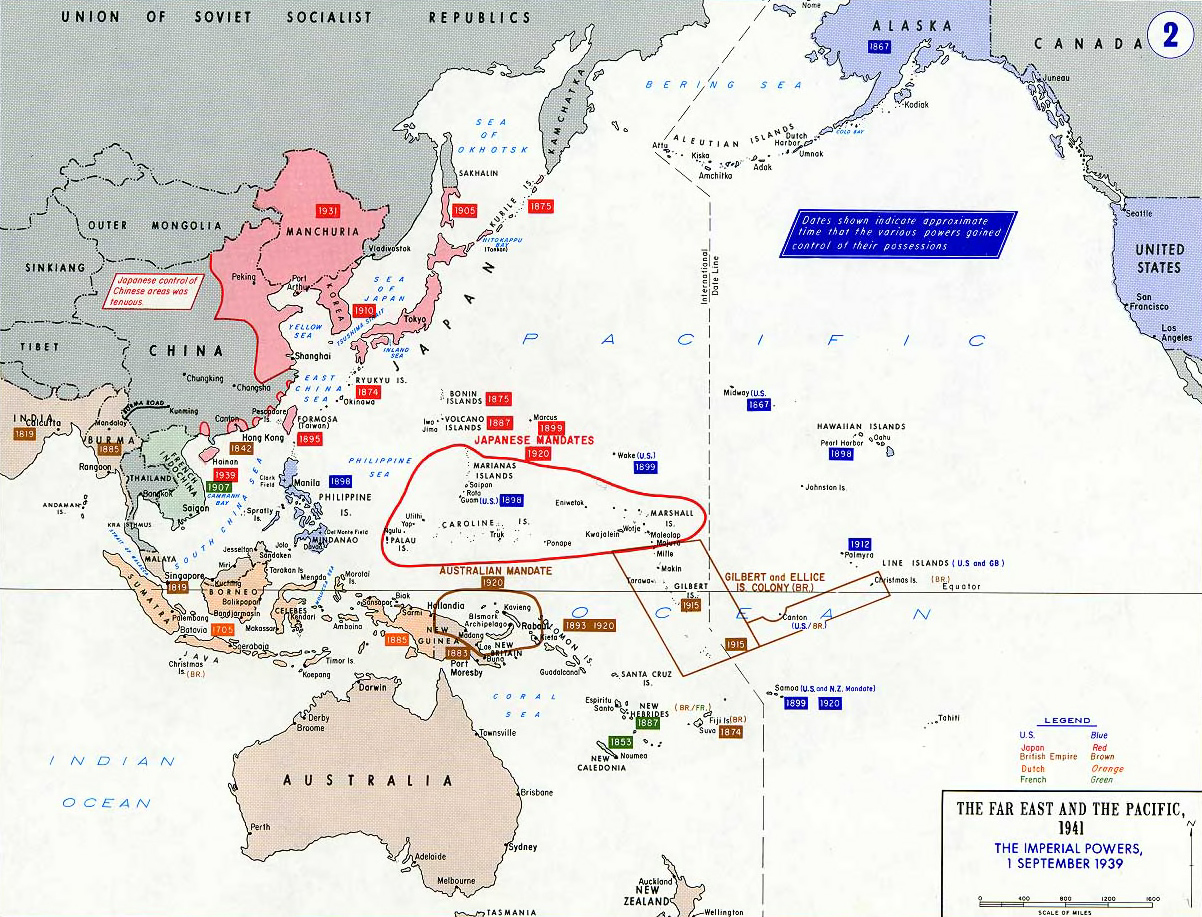

World War II

Preparations

In July 1939, Hirohito quarrelled with his brother, Yasuhito, Prince Chichibu, Prince Chichibu, over whether to support the Anti-Comintern Pact, and reprimanded the army minister, Seishirō Itagaki. But after the success of the Wehrmacht in Europe, Hirohito consented to the alliance. On 27 September 1940, ostensibly under Hirohito's leadership, Japan became a contracting partner of the Tripartite Pact with Nazi Germany, Germany and

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

forming the Axis powers.

The objectives to be obtained were clearly defined: a free hand to continue with the conquest of China and Southeast Asia, no increase in U.S. or British military forces in the region, and cooperation by the West "in the acquisition of goods needed by our Empire."

On 5 September, Prime Minister Konoe informally submitted a draft of the decision to Hirohito, just one day in advance of the Imperial Conference at which it would be formally implemented. On this evening, Hirohito had a meeting with the chief of staff of the army, Sugiyama, chief of staff of the navy, Osami Nagano, and Prime Minister Konoe. Hirohito questioned Sugiyama about the chances of success of an open war with Western world, the Occident. As Sugiyama answered positively, Hirohito scolded him:

Chief of Naval General Staff Admiral Nagano, a former Navy Minister and vastly experienced, later told a trusted colleague, "I have never seen the Emperor reprimand us in such a manner, his face turning red and raising his voice."

Nevertheless, all speakers at the Imperial Conference were united in favor of war rather than diplomacy. Baron Yoshimichi Hara, President of the Imperial Council and Hirohito's representative, then questioned them closely, producing replies to the effect that war would be considered only as a last resort from some, and silence from others.

On 8 October, Sugiyama signed a 47-page report to the Emperor (sōjōan) outlining in minute detail plans for the advance into Southeast Asia. During the third week of October, Sugiyama gave Hirohito a 51-page document, "Materials in Reply to the Throne," about the operational outlook for the war.

As war preparations continued, Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe found himself increasingly isolated, and he resigned on 16 October. He justified himself to his chief cabinet secretary, Kenji Tomita, by stating:

The army and the navy recommended the appointment of Prince Naruhiko Higashikuni, one of Hirohito's uncles, as prime minister. According to the Shōwa "Monologue", written after the war, Hirohito then said that if the war were to begin while a member of the imperial house was prime minister, the imperial house would have to carry the responsibility and he was opposed to this. Instead, Hirohito chose the hard-line General Hideki Tojo, Hideki Tōjō, who was known for his devotion to the imperial institution, and asked him to make a policy review of what had been sanctioned by the Imperial Conferences.

On 2 November Tōjō, Sugiyama, and Nagano reported to Hirohito that the review of eleven points had been in vain. Emperor Hirohito gave his consent to the war and then asked: "Are you going to provide justification for the war?" The decision for war against the United States was presented for approval to Hirohito by General Tōjō, Naval Minister Admiral Shigetarō Shimada, and Japanese Foreign Minister Shigenori Tōgō.

On 3 November, Nagano explained in detail the plan of the

attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

to Hirohito. On 5 November Emperor Hirohito approved in imperial conference the operations plan for a war against the Western world and had many meetings with the military and Tōjō until the end of the month. He initially showed hesitance towards engaging in war, but eventually approved the decision to strike Pearl Harbor despite opposition from certain advisors.

In the period leading up to Pearl Harbor, he expanded his control over military matters and participated in the Conference of Military Councillors, which was considered unusual of him. Additionally, he sought additional information regarding the attack plans.

An aide reported that he openly showed joy upon learning of the success of the surprise attacks.

On 25 November Henry L. Stimson, United States Secretary of War, noted in his diary that he had discussed with U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt the severe likelihood that Japan was about to launch a surprise attack and that the question had been "how we should maneuver them [the Japanese] into the position of firing the first shot without allowing too much danger to ourselves."

On the following day, 26 November 1941, U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull presented the Japanese ambassador with the Hull note, which as one of its conditions demanded the complete withdrawal of all Japanese troops from French Indochina and China. Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Tojo said to his cabinet, "This is an ultimatum." On 1 December an Imperial Conference sanctioned the "War against the United States, United Kingdom and the Kingdom of the Netherlands."

War: advance and retreat

On 8 December (7 December in Hawaii), 1941, in simultaneous attacks, Japanese forces Battle of Hong Kong, struck at the British Forces Overseas Hong Kong, Hong Kong Garrison, the United States Fleet in Attack on Pearl Harbor, Pearl Harbor and in the Commonwealth of the Philippines, Philippines, and began the Malayan campaign, invasion of Malaya.

With the nation fully committed to the war, Hirohito took a keen interest in military progress and sought to boost morale. According to Akira Yamada and Akira Fujiwara, Hirohito made major interventions in some military operations. For example, he pressed Sugiyama four times, on 13 and 21 January and 9 and 26 February, to increase troop strength and launch an attack on Bataan. On 9 February 19 March, and 29 May, Hirohito ordered the Army Chief of staff to examine the possibilities for an attack on Chongqing in China, which led to Operation Gogo.

While some authors, like journalists Peter Jennings and Todd Brewster, say that throughout the war, Hirohito was "outraged" at Japanese war crimes and the political dysfunction of many societal institutions that proclaimed their loyalty to him, and sometimes spoke up against them,

others, such as historians Herbert P. Bix and Mark Felton, as well as the expert on China's international relations Michael Tai, point out that Hirohito personally sanctioned the "Three Alls policy" (Sankō Sakusen), a scorched earth strategy implemented in China from 1942 to 1945 and which was both directly and indirectly responsible for the deaths of "more than 2.7 million" Chinese civilians.

As the tide of war began to turn against Japan (around late 1942 and early 1943), the flow of information to the palace gradually began to bear less and less relation to reality, while others suggest that Hirohito worked closely with Prime Minister Hideki Tojo, continued to be well and accurately briefed by the military, and knew Japan's military position precisely right up to the point of surrender. The chief of staff of the General Affairs section of the Prime Minister's office, Shuichi Inada, remarked to Tōjō's private secretary, Sadao Akamatsu:

In the first six months of war, all the major engagements had been victories. Japanese advances were stopped in the summer of 1942 with the Battle of Midway and the landing of the American forces on Guadalcanal and Tulagi in August. Hirohito played an increasingly influential role in the war; in eleven major episodes he was deeply involved in supervising the actual conduct of war operations. Hirohito pressured the High Command to order an early attack on the Philippines in 1941–42, including the fortified Bataan peninsula. He secured the deployment of army air power in the Guadalcanal campaign. Following Japan's withdrawal from Guadalcanal he demanded a new offensive in New Guinea, which was duly carried out but failed badly. Unhappy with the navy's conduct of the war, he criticized its withdrawal from the central Solomon Islands (archipelago), Solomon Islands and demanded naval battles against the Americans for the losses they had inflicted in the Aleutians. The battles were disasters. Finally, it was at his insistence that plans were drafted for the recapture of Saipan and, later, for an offensive in the Battle of Okinawa. With the Army and Navy bitterly feuding, he settled disputes over the allocation of resources. He helped plan military offenses.

In September 1944, Hirohito declared that it must be his citizens' resolve to smash the evil purposes of the Westerners so that their imperial destiny might continue, but all along, it is just a mask for the urgent need of Japan to scratch a victory against the counter-offensive campaign of the Allied Forces.

On 18 October 1944, the Imperial headquarters had resolved that the Japanese must make a stand in the vicinity of Leyte to prevent the Americans from landing in the Philippines. This view was widely frowned upon and disgruntled the policymakers from both the army and navy sectors. Hirohito was quoted that he approved of such since if they won in that campaign, they would be finally having a room to negotiate with the Americans. As high as their spirits could go, the reality check for the Japanese would also come into play since the forces they have sent in Leyte, was practically the ones that would efficiently defend the island of Luzon, hence the Japanese had struck a huge blow in their own military planning.

The media, under tight government control, repeatedly portrayed him as lifting the popular morale even as the Japanese cities came under heavy air attack in 1944–45 and food and housing shortages mounted. Japanese retreats and defeats were celebrated by the media as successes that portended "Certain Victory." Only gradually did it become apparent to the Japanese people that the situation was very grim owing to growing shortages of food, medicine, and fuel as U.S. submarines began wiping out Japanese shipping. Starting in mid 1944, American raids on the major cities of Japan made a mockery of the unending tales of victory. Later that year, with the downfall of Tojo's government, two other prime ministers were appointed to continue the war effort, Kuniaki Koiso and Kantarō Suzuki—each with the formal approval of Hirohito. Both were unsuccessful and Japan was nearing disaster.

Surrender

In early 1945, in the wake of the losses in the Battle of Leyte, Emperor Hirohito began a series of individual meetings with senior government officials to consider the progress of the war. All but ex-Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe advised continuing the war. Konoe feared a communist revolution even more than defeat in war and urged a negotiated surrender. In February 1945, during the first private audience with Hirohito he had been allowed in three years, Konoe advised Hirohito to begin negotiations to end the war. According to Grand Chamberlain Hisanori Fujita, Hirohito, still looking for a ''tennozan'' (a great victory) in order to provide a stronger bargaining position, firmly rejected Konoe's recommendation.

With each passing week victory became less likely. In April, the Soviet Union issued notice that it would not renew its neutrality agreement. Japan's ally Germany surrendered in early May 1945. In June, the cabinet reassessed the war strategy, only to decide more firmly than ever on a fight to the last man. This strategy was officially affirmed at a brief Imperial Council meeting, at which, as was normal, Hirohito did not speak.

The following day, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal of Japan, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal Kōichi Kido prepared a draft document which summarized the hopeless military situation and proposed a negotiated settlement. Extremists in Japan were also calling for a death-before-dishonor mass suicide, modeled on the "Forty-seven rōnin, 47 Ronin" incident. By mid-June 1945, the cabinet had agreed to approach the Soviet Union to act as a mediator for a negotiated surrender but not before Japan's bargaining position had been improved by repulse of the anticipated Allied invasion of mainland Japan.

On 22 June, Hirohito met with his ministers saying, "I desire that concrete plans to end the war, unhampered by existing policy, be speedily studied and that efforts be made to implement them." The attempt to negotiate a peace via the Soviet Union came to nothing. There was always the threat that extremists would carry out a coup or foment other violence. On 26 July 1945, the Allies issued the Potsdam Declaration demanding unconditional surrender. The Japanese government council, the Big Six, considered that option and recommended to Hirohito that it be accepted only if one to four conditions were agreed upon, including a guarantee of Hirohito's continued position in Culture of Japan, Japanese society.

That changed after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Soviet declaration of war. On 9 August, Emperor Hirohito told Kōichi Kido: "The Soviet Union has declared war and today began hostilities against us." On 10 August, the cabinet drafted an "Imperial Rescript ending the War" following Hirohito's indications that the declaration did not comprise any demand which prejudiced his prerogatives as a sovereign ruler.

On 12 August 1945, Hirohito informed the imperial family of his decision to surrender. One of his uncles, Prince Yasuhiko Asaka, asked whether the war would be continued if the ''kokutai'' (national polity) could not be preserved. Hirohito simply replied "Of course." On 14 August, Hirohito made the decision to surrender "unconditionally" and the Suzuki government notified the Allies that it had accepted the Potsdam Declaration.

On 15 August, a recording of Hirohito surrender broadcast, Hirohito's surrender speech was broadcast over the radio (the first time Hirohito was heard on the radio by the Japanese people) announcing Japan's acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration. During the historic broadcast Hirohito stated: "Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should we continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization." The speech also noted that "the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan's advantage" and ordered the Japanese to "endure the unendurable." The speech, using formal, archaic Japanese, was not readily understood by many commoners. According to historian Richard Storry in ''A History of Modern Japan'', Hirohito typically used "a form of language familiar only to the well-educated" and to the more traditional samurai families.

A faction of the army opposed to the surrender attempted a

coup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

on the evening of 14 August, prior to the broadcast. They seized the Imperial Palace (the Kyūjō incident), but the physical recording of Hirohito's speech was hidden and preserved overnight. The coup failed, and the speech was broadcast the next morning.

In his first ever press conference given in Tokyo in 1975, when he was asked what he thought of the bombing of Hiroshima, Hirohito answered: "It's very regrettable that nuclear bombs were dropped and I feel sorry for the citizens of Hiroshima but it couldn't be helped because that happened in wartime" (''shikata ga nai'', meaning "it cannot be helped").

Postwar reign

After the Japanese surrender in August 1945, there was a large amount of pressure that came from both Allied countries and Japanese leftists that demanded Hirohito step down and be indicted as a war criminal.

[, pp. 125–126] Australia, Britain and 70 percent of the American public wanted Hirohito tried as a Class-A war criminal. General

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

did not like the idea, as he thought that an ostensibly cooperating emperor would help establish a peaceful allied occupation regime in Japan.

MacArthur saw Hirohito as a symbol of the continuity and cohesion of the Japanese people. To avoid the possibility of civil unrest in Japan, any possible evidence that would incriminate Hirohito and his family were excluded from the International Military Tribunal for the Far East.

MacArthur created a plan that separated Hirohito from the militarists, retained Hirohito as a constitutional monarch but only as a figurehead, and used Hirohito to retain control over Japan to help achieve American postwar objectives in Japan.

As Hirohito appointed his uncle and daughter's father-in-law, Prince Naruhiko Higashikuni as the Prime Minister to replace Kantarō Suzuki, who resigned owing to responsibility for the surrender, to assist the American occupation, there were attempts by numerous leaders to have him put on trial for alleged war crimes. Many members of the imperial family, such as Yasuhito, Prince Chichibu, Princes Chichibu, Nobuhito, Prince Takamatsu, Takamatsu, and Higashikuni, pressured Hirohito to abdicate so that one of the Princes could serve as regent until his eldest son, Crown Prince

Akihito

Akihito (born 23 December 1933) is a member of the Imperial House of Japan who reigned as the 125th emperor of Japan from 1989 until 2019 Japanese imperial transition, his abdication in 2019. The era of his rule was named the Heisei era, Hei ...

came of age. On 27 February 1946, Hirohito's youngest brother, Prince Mikasa, even stood up in the privy council and indirectly urged Hirohito to step down and accept responsibility for Japan's defeat. According to Minister of Welfare Ashida's diary, "Everyone seemed to ponder Mikasa's words. Never have I seen His Majesty's face so pale."

Before the war crime trials actually convened, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, its International Prosecution Section (IPS) and Japanese officials worked behind the scenes not only to prevent the Imperial family from being indicted, but also to influence the testimony of the defendants to ensure that no one implicated Hirohito. High officials in court circles and the Japanese government collaborated with Allied General Headquarters in compiling lists of prospective war criminals, while the individuals arrested as ''Class A'' suspects and incarcerated solemnly vowed to protect their sovereign against any possible taint of war responsibility. Thus, "months before the Tokyo tribunal commenced, MacArthur's highest subordinates were working to attribute ultimate responsibility for Pearl Harbor to Hideki Tōjō" by allowing "the major criminal suspects to coordinate their stories so that Hirohito would be spared from indictment." According to John W. Dower, "This successful campaign to absolve Hirohito of war responsibility knew no bounds. Hirohito was not merely presented as being innocent of any formal acts that might make him culpable to indictment as a war criminal, he was turned into an almost saintly figure who did not even bear moral responsibility for the war." According to Bix, "MacArthur's truly extraordinary measures to save Hirohito from trial as a war criminal had a lasting and profoundly distorting impact on Japanese understanding of the lost war."

Historian Gary J. Bass presented evidence supporting Hirohito's responsibility in the war, noting that had he been prosecuted as some judges and others advocated, a compelling case could have been constructed against him. However, the Americans were apprehensive that removing the emperor from power and subjecting him to trial could trigger widespread chaos and collapse of Japan, given his revered status among the Japanese populace.

Additionally, the advent of the Cold War brought about harsh political circumstances. Chiang Kai-shek's Chinese Kuomintang, nationalists were losing the Chinese Civil War to Mao Zedong's Chinese Communist Party, prompting the Truman administration to consider the potential loss of China as an ally and strategic partner. As a result, ensuring Japan's strength and stability became imperative for securing a reliable postwar ally.

Imperial status

Hirohito was not put on trial, but he was forced to Humanity Declaration, explicitly reject the quasi-official claim that Hirohito of Japan was an ''arahitogami'', i.e., an incarnate divinity. This was motivated by the fact that, according to the Meiji Constitution, Japanese constitution of 1889, Hirohito had a divine power over his country which was derived from the Shinto belief that the Japanese Imperial Family were the descendants of the sun goddess Amaterasu. Hirohito was however persistent in the idea that the Emperor of Japan should be considered a descendant of the gods. In December 1945, he told his vice-grand-chamberlain Michio Kinoshita: "It is permissible to say that the idea that the Japanese are descendants of the gods is a false conception; but it is absolutely impermissible to call wikt:chimerical, chimerical the idea that the Emperor is a descendant of the gods." In any case, the "renunciation of divinity" was noted more by foreigners than by Japanese, and seems to have been intended for the consumption of the former. The theory of a constitutional monarchy had already had some proponents in Japan. In 1935, when Tatsukichi Minobe advocated the theory that sovereignty resides in the state, of which the Emperor is just an organ (the ''tennō kikan setsu''), it caused a furor. He was forced to resign from the House of Peers and his post at the Tokyo Imperial University, his books were banned, and an attempt was made on his life. Not until 1946 was the tremendous step made to alter the Emperor's title from "imperial sovereign" to "constitutional monarch."

Although the Emperor had supposedly repudiated claims to divinity, his public position was deliberately left vague, partly because General MacArthur thought him probable to be a useful partner to get the Japanese to accept the occupation and partly owing to behind-the-scenes maneuvering by Shigeru Yoshida to thwart attempts to cast him as a European-style monarch.

Nevertheless, Hirohito's status as a limited constitutional monarch was formalized with the enactment of the Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitution–officially, an amendment to the Meiji Constitution. It defined the Emperor as "the symbol of the state and the unity of the people." His role was redefined as entirely ceremonial and representative, without even nominal governmental powers. He was limited to performing matters of state as delineated in the Constitution, and in most cases his actions in that realm were carried out in accordance with the binding instructions of the Cabinet. In 1947, Hirohito became the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people under the nation's Constitution of Japan, new constitution, which was written by the United States.

Following the Iranian Revolution and the end of the short-lived Central African Empire, both in 1979, Hirohito found himself the last monarch in the world to bear any variation of the highest royal title "emperor."

Public figure

He was not only the first reigning Japanese emperor to visit foreign countries, but also the first to meet an American president. His status and image became strongly positive in the United States.

Visit to Europe

The talks between Emperor Hirohito and President Nixon were not planned at the outset, because initially the stop in the United States was only for refueling to visit Europe. However, the meeting was decided in a hurry at the request of the United States. Although the Japanese side accepted the request, Minister for Foreign Affairs (Japan), Minister for Foreign Affairs Takeo Fukuda made a public telephone call to the Japanese ambassador to the United States Nobuhiko Ushiba, who promoted talks, saying, "that will cause me a great deal of trouble. We want to correct the perceptions of the other party." At that time, Foreign Minister Fukuda was worried that President Nixon's talks with Hirohito would be used to repair the deteriorating Japan–U.S. relations, and he was concerned that the premise of the symbolic emperor system could fluctuate.

There was an early visit with deep royal exchanges in Denmark and Belgium. In France, Hirohito was warmly welcomed, and reunited with Edward VIII, who had Abdication of Edward VIII, abdicated in 1936 and was virtually in exile, and they chatted for a while. However, protests were held in Britain and the Netherlands by veterans who had served in the South-East Asian theatre of World War II and civilian victims of the brutal occupation there. In the Netherlands, raw eggs and vacuum flasks were thrown. The protest was so severe that Empress Nagako, who accompanied the Emperor, was exhausted. In the United Kingdom, protestors stood in silence and turned their backs when Hirohito's carriage passed them while others wore red gloves to symbolize the dead. The satirical magazine ''Private Eye'' used a racist double entendre to refer to Hirohito's visit ("nasty Nip in the air"). In West Germany, the Japanese monarch's visit was met with hostile far-left protests, participants of which viewed Hirohito as the East Asian equivalent of Adolf Hitler and referred to him as "Hirohitler", and prompted a wider comparative discussion of the memory and perception of Axis war crimes. The protests against Hirohito's visit also condemned and highlighted what they perceived as mutual Japanese and West German complicity in and enabling of the American Vietnam War, war effort against communism in Vietnam.

Regarding these protests and opposition, Emperor Hirohito was not surprised to have received a report in advance at a press conference on 12 November after returning to Japan and said that "I do not think that welcome can be ignored" from each country.

Also, at a press conference following their golden wedding anniversary three years later, along with the Empress, he mentioned this visit to Europe as his most enjoyable memory in 50 years.

[#陛下、お尋ね申し上げます 1988, 陛下、お尋ね申し上げます 1988 p. 193]

Visit to the United States