Hiram Johnson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

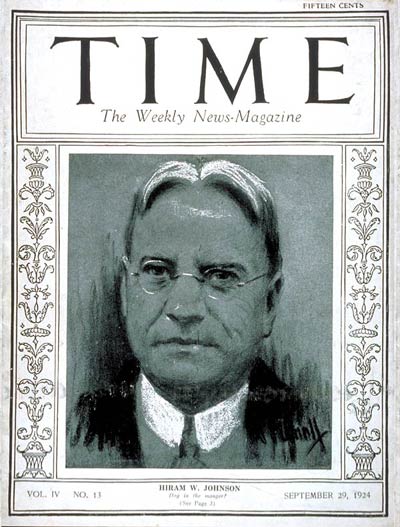

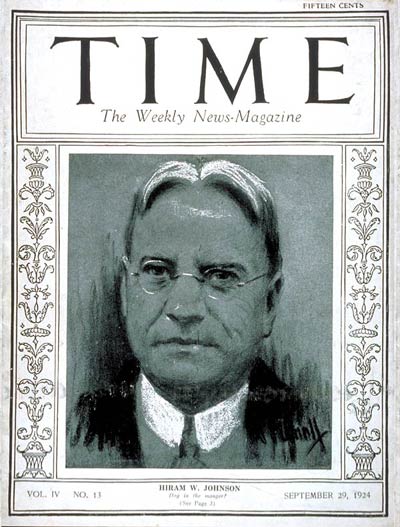

Hiram Warren Johnson (September 2, 1866August 6, 1945) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 23rd

In 1902, Johnson moved to

In 1902, Johnson moved to

In 1910, Johnson won the gubernatorial election as a member of the Lincoln–Roosevelt League, a Progressive Republican movement, running on a platform opposed to the

In 1910, Johnson won the gubernatorial election as a member of the Lincoln–Roosevelt League, a Progressive Republican movement, running on a platform opposed to the

In 1912, Johnson was a founder of the national Progressive Party and ran as the party's vice presidential candidate, sharing a ticket with former President

In 1912, Johnson was a founder of the national Progressive Party and ran as the party's vice presidential candidate, sharing a ticket with former President

Following Theodore Roosevelt's death in January 1919, Johnson was the most prominent leader in the surviving progressive movement; the Progressive Party of 1912 was dead. In 1920, he ran for the Republican nomination for president but was defeated by conservative Senator

Following Theodore Roosevelt's death in January 1919, Johnson was the most prominent leader in the surviving progressive movement; the Progressive Party of 1912 was dead. In 1920, he ran for the Republican nomination for president but was defeated by conservative Senator

Having served in the Senate for almost thirty years, Johnson died of a cerebral

Having served in the Senate for almost thirty years, Johnson died of a cerebral

Hiram Johnson papers, 1895–1945

/ref> Hiram Johnson High School in

in JSTOR

* McKee, Irving. "The Background and Early Career of Hiram Warren Johnson, 1866–1910." ''Pacific Historical Review'' (1950): 17–30

in JSTOR

* Miller, Karen A.J. ''Populist Nationalism: Republican Insurgency and American Foreign Policy Making, 1918–1925'' (Greenwood, 1999) * Olin, Spencer C. ''California's Prodigal Sons: Hiram Johnson and the Progressives, 1911–1917'' (University of California Press, 1968) * Olin, Spencer C. "Hiram Johnson, the California Progressives, and the Hughes Campaign of 1916." ''The Pacific Historical Review'' (1962): 403–412

in JSTOR

* Olin, Spencer C. "Hiram Johnson, the Lincoln-Roosevelt League, and the Election of 1910." ''California Historical Society Quarterly'' (1966): 225–240

in JSTOR

* Olin, Spencer C. "European Immigrant and Oriental Alien: Acceptance and Rejection by the California Legislature of 1913." ''Japanese Immigrants and American Law'' (Routledge, 2019) pp. 331–343

online

* Shover, John L. "The Progressives and the Working Class Vote in California." ''Labor History'' (1969) 10#4 pp: 584–601

online

* Weatherson, Michael A., and Hal Bochin. ''Hiram Johnson: Political Revivalist'' (University Press of America, 1995) * Weatherson, Michael A., and Hal Bochin. ''Hiram Johnson: A Bio-Bibliography'' (Greenwood Press, 1988)

Guide to the Hiram Johnson Papers

at the Bancroft Library *

California Progressive Campaign for 1914 Three Years of Progressive Administration in California Under Governor Hiram W. Johnson

Robert E. Burke Collection.

1892–1994. 60.43 cubic feet (68 boxes plus two oversize folders and one oversize vertical file). At th

Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Libraries Special Collections.

Contains materials collected by Burke on Hiram Johnson from 1910 to 1994. , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Johnson, Hiram Warren 1866 births 1912 United States vice-presidential candidates 1945 deaths 20th-century American Episcopalians American people of French descent American segregationists Anti-Japanese sentiment Articles containing video clips Burials at Cypress Lawn Memorial Park California Progressives (1912) Candidates in the 1920 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1924 United States presidential election Deaths from thrombosis Direct democracy activists District attorneys in California Republican Party governors of California Heald College alumni History of San Francisco Politicians from Sacramento, California Politicians from San Francisco Progressive Party (1912) state governors of the United States Republican Party United States senators from California University of California, Berkeley alumni 20th-century United States senators

governor of California

The governor of California is the head of government of the U.S. state of California. The Governor (United States), governor is the commander-in-chief of the California National Guard and the California State Guard.

Established in the Constit ...

from 1911 to 1917 and represented California in the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and House have the authority under Article One of the ...

for five terms from 1917 to 1945. Johnson achieved national prominence in the early 20th century as a leading progressive and ran for vice president on Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

's Progressive ticket in the 1912 presidential election. As a U.S. senator, Johnson voted for American entry into World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and was later a critic of the foreign policy of both Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

and Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

.

Johnson was born in 1866 and worked as a stenographer and reporter before embarking on a legal career in his hometown of Sacramento

Sacramento ( or ; ; ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of California and the seat of Sacramento County. Located at the confluence of the Sacramento and American Rivers in Northern California's Sacramento Valley, Sacramento's 2020 p ...

. After he moved to San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, he worked as an assistant district attorney

In the United States, a district attorney (DA), county attorney, county prosecutor, state attorney, state's attorney, prosecuting attorney, commonwealth's attorney, or solicitor is the chief prosecutor or chief law enforcement officer represen ...

and gained statewide renown for his prosecutions of public corruption. On the back of this popularity, Johnson won the 1910 California gubernatorial election with the backing of the progressive Lincoln–Roosevelt League. He instituted several progressive reforms, establishing a railroad commission and introducing aspects of direct democracy

Direct democracy or pure democracy is a form of democracy in which the Election#Electorate, electorate directly decides on policy initiatives, without legislator, elected representatives as proxies, as opposed to the representative democracy m ...

, such as the power to recall state officials. Having joined with Theodore Roosevelt and other progressives to form the Progressive Party, Johnson won the party's 1912 vice-presidential nomination. In one of the best third-party

Third party may refer to:

Business

* Third-party source, a supplier company not owned by the buyer or seller

* Third-party beneficiary, a person who could sue on a contract, despite not being an active party

* Third-party insurance, such as a veh ...

performances in U.S. history, the ticket finished second nationally in the popular and electoral votes.

Johnson was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1916

Events

Below, the events of the First World War have the "WWI" prefix.

January

* January 1 – The British Empire, British Royal Army Medical Corps carries out the first successful blood transfusion, using blood that has been stored ...

, becoming a leader of the chamber's Progressive Republicans. He made his biggest mark in the Senate as an early voice for isolationism

Isolationism is a term used to refer to a political philosophy advocating a foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality an ...

but voted for U.S. entry into World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. He opposed U.S. participation in the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

. He unsuccessfully sought the Republican presidential nomination in 1920

Events January

* January 1

** Polish–Soviet War: The Russian Red Army increases its troops along the Polish border from 4 divisions to 20.

** Kauniainen in Finland, completely surrounded by the city of Espoo, secedes from Espoo as its ow ...

and 1924. Although he supported Democratic nominee Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1932 presidential election and many of the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

programs, by November 1936 he had become hostile to Roosevelt, whom he viewed as a potential dictator. He remained in the Senate until his death in 1945.

Early years

Hiram Johnson was born inSacramento

Sacramento ( or ; ; ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of California and the seat of Sacramento County. Located at the confluence of the Sacramento and American Rivers in Northern California's Sacramento Valley, Sacramento's 2020 p ...

on September 2, 1866. His father, Grove Lawrence Johnson, was an attorney and Republican U.S. Representative

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

and a member of the California State Legislature

The California State Legislature is the bicameral state legislature of the U.S. state of California, consisting of the California State Assembly (lower house with 80 members) and the California State Senate (upper house with 40 members). ...

whose career was marred by accusations of election fraud and graft. His mother, Mabel Ann "Annie" Williamson De Montfredy, was a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution

The National Society Daughters of the American Revolution (often abbreviated as DAR or NSDAR) is a lineage-based membership service organization for women who are directly descended from a patriot of the American Revolutionary War.

A non-p ...

based on her descent from Pierre Van Cortlandt and Philip Van Cortlandt. Johnson had one brother and three sisters.

Johnson attended the public schools of Sacramento and was 16 when he graduated from Sacramento High School in 1882 as the class valedictorian. Too young to begin attending college, Johnson worked as a shorthand

Shorthand is an abbreviated symbolic writing method that increases speed and brevity of writing as compared to Cursive, longhand, a more common method of writing a language. The process of writing in shorthand is called stenography, from the Gr ...

reporter and stenographer in his father's law office and attended Heald's Business College. He studied law at the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

from 1884 to 1886, where he was a member of Chi Phi fraternity. After his admission to the bar in 1888, Johnson practiced in Sacramento with his brother Albert as the firm of Johnson & Johnson. When the State Bar of California

The State Bar of California is an administrative division of the Supreme Court of California which licenses attorneys and regulates the practice of law in California. It is responsible for managing the admission of lawyers to the practice of law ...

was organized in 1927, William H. Waste, the Chief Justice of the California Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of California is the highest and final court of appeals in the courts of the U.S. state of California. It is headquartered in San Francisco at the Earl Warren Building, but it regularly holds sessions in Los Angeles and Sac ...

, was given license number one and Johnson received number two. Both his son, Hiram Jr. and grandson, Hiram III, were later members of the California State Bar.

In addition to practicing law, Johnson was active in politics as a Republican, including supporting his father's campaigns. In 1899, Johnson backed the mayoral campaign of George H. Clark. Clark won, and when he took office in 1900, he named Johnson as city attorney.

In 1902, Johnson moved to

In 1902, Johnson moved to San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, where he quickly developed a reputation as a fearless litigator, primarily as a criminal defense lawyer, while becoming active in reform

Reform refers to the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The modern usage of the word emerged in the late 18th century and is believed to have originated from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement, which ...

politics. He attracted statewide attention in 1908 when he assisted District Attorney

In the United States, a district attorney (DA), county attorney, county prosecutor, state attorney, state's attorney, prosecuting attorney, commonwealth's attorney, or solicitor is the chief prosecutor or chief law enforcement officer represen ...

William H. Langdon and Assistant DA Francis J. Heney in the prosecution of Abe Ruef and Mayor Eugene Schmitz for graft. After Heney was shot in the courtroom during an attempted assassination, Johnson took the lead for the prosecution and won the case.

Governor of California (1911–1917)

In 1910, Johnson won the gubernatorial election as a member of the Lincoln–Roosevelt League, a Progressive Republican movement, running on a platform opposed to the

In 1910, Johnson won the gubernatorial election as a member of the Lincoln–Roosevelt League, a Progressive Republican movement, running on a platform opposed to the Southern Pacific Railroad

The Southern Pacific (or Espee from the railroad initials) was an American Railroad classes#Class I, Class I Rail transport, railroad network that existed from 1865 to 1996 and operated largely in the Western United States. The system was oper ...

. During his campaign, he toured the state in an open automobile, covering thousands of miles and visiting small communities throughout California that were inaccessible by rail. Johnson helped establish rules that made voting and the political process easier. For example, he established rules to facilitate recalls. This measure was used to remove Governor Gray Davis from office in 2003 and to enable an unsuccessful effort to remove Governor Gavin Newsom

Gavin Christopher Newsom ( ; born October 10, 1967) is an American politician and businessman serving since 2019 as the 40th governor of California. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served from 2011 to 201 ...

in 2021.

In office, Johnson was a populist

Populism is a contested concept used to refer to a variety of political stances that emphasize the idea of the " common people" and often position this group in opposition to a perceived elite. It is frequently associated with anti-establis ...

who promoted a number of democratic reforms: the election of U.S. Senators by direct popular vote rather than the state legislature (which was later ratified nationwide by a constitutional amendment), cross-filing

In United States, American politics, cross-filing (similar to the concept of electoral fusion) occurs when a candidate runs in the Partisan primary, primary election of not only their own party, but also that of one or more other parties, generall ...

, initiative

Popular initiative

A popular initiative (also citizens' initiative) is a form of direct democracy by which a petition meeting certain hurdles can force a legal procedure on a proposition.

In direct initiative, the proposition is put direct ...

, referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

, and recall elections

A recall election (also called a recall referendum, recall petition or representative recall) is a procedure by which voters can remove an elected official from office through a referendum before that official's term of office has ended. Recalls ...

. Johnson's reforms gave California a degree of direct democracy unmatched by any other U.S. state at the time. When he took office, amid rampant corruption, the Southern Pacific Railroad held so much power it was known as the fourth branch of government. "While I do not by any means believe the initiative, the referendum and the recall are the panacea for all our political ills," Johnson extolled in his 1911 inaugural address, "they do give to the electorate the power of action when desired, and they do place in the hands of the people the means by which they may protect themselves."

Johnson was also instrumental in reining in the power of the Southern Pacific Railroad

The Southern Pacific (or Espee from the railroad initials) was an American Railroad classes#Class I, Class I Rail transport, railroad network that existed from 1865 to 1996 and operated largely in the Western United States. The system was oper ...

through the establishment of a state railroad commission. On taking office, Johnson paroled Chris Evans, convicted as the Southern Pacific train bandit, but required that he leave California.

Although initially opposed to the bill, Johnson gave in to political pressure and supported the California Alien Land Law of 1913

The California Alien Land Law of 1913 (also known as the Webb–Haney Act) prohibited "aliens ineligible for citizenship" from owning agricultural land or possessing long-term leases over it, but permitted leases lasting up to three years. It affe ...

, which prevented Asian immigrants from owning land in the state (they were already excluded from naturalized citizenship because of their race).

1912 vice presidential campaign

In 1912, Johnson was a founder of the national Progressive Party and ran as the party's vice presidential candidate, sharing a ticket with former President

In 1912, Johnson was a founder of the national Progressive Party and ran as the party's vice presidential candidate, sharing a ticket with former President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

. Roosevelt and Johnson narrowly carried California but finished second nationally behind the Democratic ticket of Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

and Thomas R. Marshall. Their second-place finish, ahead of incumbent Republican President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

, remains among the strongest for any third party

Third party may refer to:

Business

* Third-party source, a supplier company not owned by the buyer or seller

* Third-party beneficiary, a person who could sue on a contract, despite not being an active party

* Third-party insurance, such as a veh ...

in American history.

Johnson was re-elected governor of California in 1914 as the Progressive Party candidate, gaining nearly twice the votes of his Republican opponent John D. Fredericks. In 1917, as one of his final acts as governor before ascending to the U.S. Senate, Johnson signed Senate Constitutional Amendment 26, providing health insurance for all in the Golden State. Then it was put on the ballot for ratification. A coalition of insurance companies took out an ad in The Chronicle, warning it "would spell social ruin to the United States." Every voter in the state, as recounted in a recent issue of the New Yorker, "received in the mail a pamphlet with a picture of the Kaiser and the words 'Born in Germany. Do you want it in California?'" The ballot measure failed, 27%-73%.

U.S. Senator (1917–1945)

In 1916, Johnson ran successfully for the U.S. Senate, defeating conservative Democrat George S. Patton Sr. and took office on March 16, 1917. Johnson was elected as a staunch opponent of American entry intoWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, but voted in favor of war after his election. He later voted against the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

. He allegedly said, "The first casualty when war comes is truth." However, this quote may be apocryphal.

During his Senate career, Johnson served as chairman of the Committees on Cuban Relations (Sixty-sixth Congress), Patents (Sixty-seventh Congress), Immigration (Sixty-eighth through Seventy-first Congresses), Territories and Insular Possessions (Sixty-eighth Congress), and Commerce (Seventy-first and Seventy-second Congresses).

In 1916, Representative John I. Nolan introduced H.R. 7625, which would have established a $3 per day minimum wage

A minimum wage is the lowest remuneration that employers can legally pay their employees—the price floor below which employees may not sell their labor. List of countries by minimum wage, Most countries had introduced minimum wage legislation b ...

for federal employees. It was endorsed by the AFL and the National Federation of Federal Employees

The National Federation of Federal Employees (NFFE) is an American labor union which represents about 100,000 public employees in the federal government.

NFFE has about 200 local unions, most of them agency-wide bargaining units. Its members wo ...

, but the bill's opponents in the House kept it from coming to a vote. In 1918, Senator Johnson co-sponsored the legislation, and it became known as the Johnson-Nolan Minimum Wage Bill. It passed the House that September, but was stalled in the Senate Committee on Education and Labor

The Committee on Education and Workforce is a Standing committee (United States Congress), standing committee of the United States House of Representatives. There are 45 members of this committee. Since 2025, the chair of the Education and Work ...

. It was reintroduced two years later and passed in both the House and Senate, but when it went to conference it was filibustered by Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats are members of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States.

Before the American Civil War, Southern Democrats mostly believed in Jacksonian democracy. In the 19th century, they defended slavery in the ...

who opposed it because it would have paid African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

employees the same as white employees.

In the Senate, Johnson helped push through the Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from every count ...

, having worked with Valentine S. McClatchy

Valentine Stuart McClatchy (August 29, 1857 – May 15, 1938) was an American newspaper owner and journalist. As publisher of ''The Sacramento Bee'' (now The McClatchy Company) from the time of his father's death in 1883, co-owning the paper with ...

and other anti-Japanese lobbyists

Lobbying is a form of advocacy, which lawfully attempts to directly influence legislators or government officials, such as regulatory agencies or judiciary. Lobbying involves direct, face-to-face contact and is carried out by various entities, in ...

to prohibit Japanese and other East Asian

East Asia is a geocultural region of Asia. It includes China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan, plus two special administrative regions of China, Hong Kong and Macau. The economies of Economy of China, China, Economy of Ja ...

immigrants from entering the United States.

In the early 1920s, the motion picture industry sought to establish a self-regulatory process to fend off official censorship. Senator Johnson was among three candidates identified to head a new group, alongside Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

and Will H. Hays. Hays, who had managed President Harding's 1920 campaign, was ultimately named to head the new Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America in early 1922.

As Senator, Johnson proved extremely popular. In 1934

Events

January–February

* January 1 – The International Telecommunication Union, a specialist agency of the League of Nations, is established.

* January 15 – The 8.0 1934 Nepal–Bihar earthquake, Nepal–Bihar earthquake strik ...

, he was re-elected with 94.5 percent of the popular vote; he was nominated by both the Republican and Democratic parties and his only opponent was Socialist George Ross Kirkpatrick.

Johnson was a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for authorizing and overseeing foreign a ...

continuously for 25 years, from the 66th Congress (1919–21) through the 78th Congress (1943–44) and one of its longest serving members. In 1943, a confidential analysis of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, made by British scholar Isaiah Berlin

Sir Isaiah Berlin (6 June 1909 – 5 November 1997) was a Russian-British social and political theorist, philosopher, and historian of ideas. Although he became increasingly averse to writing for publication, his improvised lectures and talks ...

for his Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* United ...

, stated that Johnson:

:is the Isolationists' elder statesman and the only surviving member of the illiam E. Borah- enry Cabot Lodge-Johnson combination which led the fight against the League in 1919 and 1920. He is an implacable and uncompromising Isolationist with immense prestige in California, of which he has twice been Governor. His election to the Senate has not been opposed for many years by either party. He is acutely Pacific-conscious and is a champion of a more adequate defence of the West Coast. He is a member of the Farm ''Bloc'' and is ''au fond'', against foreign affairs as such; his view of Europe as a sink of iniquity has not changed in any particular since 1912, when he founded a short-lived progressive party. His prestige in Congress is still great and his parliamentary skill should not be underestimated.

In 1945, Johnson was absent when the vote took place for ratification of the United Nations Charter

The Charter of the United Nations is the foundational treaty of the United Nations (UN). It establishes the purposes, governing structure, and overall framework of the United Nations System, UN system, including its United Nations System#Six ...

, but made it known that he would have voted against this outcome. Senators Henrik Shipstead

Henrik Shipstead (January 8, 1881June 26, 1960) was Norwegian-American dentist and politician who served in the United States Senate from 1923 to 1947, representing the state of Minnesota. He served first as a member of the Minnesota Farmer-Labor ...

and William Langer were the only ones to cast votes opposing ratification.

Presidential politics

Following Theodore Roosevelt's death in January 1919, Johnson was the most prominent leader in the surviving progressive movement; the Progressive Party of 1912 was dead. In 1920, he ran for the Republican nomination for president but was defeated by conservative Senator

Following Theodore Roosevelt's death in January 1919, Johnson was the most prominent leader in the surviving progressive movement; the Progressive Party of 1912 was dead. In 1920, he ran for the Republican nomination for president but was defeated by conservative Senator Warren Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents w ...

. Johnson did not get the support of Roosevelt's family, who instead supported Roosevelt's long-time friend Leonard Wood

Leonard Wood (October 9, 1860 – August 7, 1927) was a United States Army major general, physician, and public official. He served as the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, List of colonial governors of Cuba, Military Governor of Cuba, ...

. At the convention, Johnson was asked to serve as Harding's running mate but he declined. Johnson sought the 1924 Republican nomination against President Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States, serving from 1923 to 1929. A Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer from Massachusetts, he previously ...

; his campaign was derailed after he lost the California primary. Johnson declined to challenge Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

for the 1928 presidential nomination, instead choosing to seek re-election to the Senate.

In the 1932 United States presidential election

United States presidential election, Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 8, 1932. Against the backdrop of the Great Depression, the History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ticket of incumbent Pre ...

, Johnson broke with President Hoover. He was one of the most prominent Republicans to support Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

. During Roosevelt's first term, Johnson supported the president's New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

economic recovery package and frequently "crossed the floor

In some parliamentary systems (e.g., in Canada and the United Kingdom), politicians are said to cross the floor if they formally change their political affiliation to a political party different from the one they were initially elected under. I ...

" to aid the Democrats. By late 1936, he was convinced that Roosevelt was a dangerous would-be dictator. Although in poor health, Johnson attacked Roosevelt and the New Deal following the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937

The Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937, frequently called the "court-packing plan",Epstein, at 451. was a legislative initiative proposed by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt to add more justices to the U.S. Supreme Court in order ...

, the president's " court-packing" attempt.

Personal life

In January 1886, Johnson married Minne L. McNeal (1869–1947). The couple had two sons: Hiram W. "Jack" Johnson Jr. (1886–1959), and Archibald "Archie" McNeal Johnson (1890–1933). Both sons practiced law in California and served in the army. Hiram Jr. was a veteran ofWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, and attained the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Army Air Corps while stationed at Fort Mason

Fort Mason, in San Francisco, California is a former United States Army post located in the northern Marina District, alongside San Francisco Bay. Fort Mason served as an Army post for more than 100 years, initially as a coastal defense site a ...

in San Francisco during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Archie Johnson was a major of field artillery corps and was wounded in action during the First World War.

Death

Having served in the Senate for almost thirty years, Johnson died of a cerebral

Having served in the Senate for almost thirty years, Johnson died of a cerebral thrombosis

Thrombosis () is the formation of a Thrombus, blood clot inside a blood vessel, obstructing the flow of blood through the circulatory system. When a blood vessel (a vein or an artery) is injured, the body uses platelets (thrombocytes) and fib ...

at the Naval Hospital in Bethesda, Maryland

Bethesda () is an unincorporated, census-designated place in southern Montgomery County, Maryland, United States. Located just northwest of Washington, D.C., it is a major business and government center of the Washington metropolitan region ...

, on August 5, 1945, the day before the US- conducted atomic bombing of Hiroshima. He had been in failing health for several months. He was interred in a mausoleum

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the burial chamber of a deceased person or people. A mausoleum without the person's remains is called a cenotaph. A mausoleum may be considered a type o ...

at Cypress Lawn Memorial Park in Colma, California and his remains are interred with those of his wife, Minne, and two sons.

Legacy

During his first term gubernatorial inaugural address on January 3, 1911, Johnson declared that his first duty was "to eliminate every private interest from the government and to make the public service of the State responsive solely to the people." Committed to "arm the people to protect themselves" against such abuses, Johnson proposed amending the state Constitution with "the initiative, the referendum and the recall." All three of these progressive reforms were enacted during his governorship, forever guaranteeing Johnson's stature as the preeminent progressive reformer of California politics. His contribution as the driving force behind the direct democratic process for removal of elected officials was revisited in the media and by the general public during the successful 2003 California recall election of Democratic governor Gray Davis. RepublicanArnold Schwarzenegger

Arnold Alois Schwarzenegger (born July30, 1947) is an Austrian and American actor, businessman, former politician, and former professional bodybuilder, known for his roles in high-profile action films. Governorship of Arnold Schwarzenegger, ...

, the eventual winner, referred to Johnson's progressive legacy in his campaign speeches. Johnson's stature in fostering the California recall and ballot initiative direct democratic processes again surfaced in the media during the unsuccessful 2021 California recall election of Democratic governor Gavin Newsom

Gavin Christopher Newsom ( ; born October 10, 1967) is an American politician and businessman serving since 2019 as the 40th governor of California. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served from 2011 to 201 ...

.

On August 25, 2009, Governor Schwarzenegger and his wife, Maria Shriver

Maria Owings Shriver ( ; born November 6, 1955)

is an American journalist, author, a member of the prominent Shriver and Kennedy families, former First Lady of California, and the founder of the nonprofit organization The Women's Alzheimer's M ...

, announced that Johnson would be one of 13 inducted into the California Hall of Fame

The California Hall of Fame is an institution created in 2006 by Maria Shriver to honor important Californians. The award was designed by Californian artists Robert Graham (sculptor), Robert Graham. The hall is located in The California Museum i ...

that year.

Johnson held the record as California's longest-serving United States Senator for over 75 years, until it was broken by Democrat Dianne Feinstein

Dianne Emiel Feinstein (; June 22, 1933 – September 29, 2023) was an American politician who served as a United States senator from California from 1992 until her death in 2023. A member of the Democratic Party, she served as the 38th ...

on March 28, 2021. He remains the longest serving Republican senator and the longest serving male senator from California.

The Hiram Johnson papers, consisting primarily of hundreds of letters that Johnson wrote to his two sons over the course of decades, and that his son, Hiram Jr. donated in 1955, reside at the Bancroft Library

The Bancroft Library is the primary special-collections library of the University of California, Berkeley. It was acquired from its founder, Hubert Howe Bancroft, in 1905, with the proviso that it retain the name Bancroft Library in perpetuity. ...

at the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

./ref> Hiram Johnson High School in

Sacramento, California

Sacramento ( or ; ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of California and the county seat, seat of Sacramento County, California, Sacramento County. Located at the confluence of the Sacramento Rive ...

is named in his honor.

See also

*List of United States Congress members who died in office (1900–49)

There are several lists of United States Congress members who died in office. These include:

*List of United States Congress members who died in office (1790–1899)

*List of United States Congress members who died in office (1900–1949)

*List ...

Notes

References

Further reading

* Blackford, Mansel Griffiths. "Businessmen and the Regulation of Railroads and Public Utilities in California during the Progressive Era." ''Business History Review'' 44.03 (1970): 307–319. * Feinman, Ronald L. ''Twilight of Progressivism: the Western Republican Senators and the New Deal'' (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981) * Le Pore, Herbert P. "Prelude to Prejudice: Hiram Johnson, Woodrow Wilson, and the California Alien Land Law Controversy of 1913." ''Southern California Quarterly'' (1979): 99–110in JSTOR

* McKee, Irving. "The Background and Early Career of Hiram Warren Johnson, 1866–1910." ''Pacific Historical Review'' (1950): 17–30

in JSTOR

* Miller, Karen A.J. ''Populist Nationalism: Republican Insurgency and American Foreign Policy Making, 1918–1925'' (Greenwood, 1999) * Olin, Spencer C. ''California's Prodigal Sons: Hiram Johnson and the Progressives, 1911–1917'' (University of California Press, 1968) * Olin, Spencer C. "Hiram Johnson, the California Progressives, and the Hughes Campaign of 1916." ''The Pacific Historical Review'' (1962): 403–412

in JSTOR

* Olin, Spencer C. "Hiram Johnson, the Lincoln-Roosevelt League, and the Election of 1910." ''California Historical Society Quarterly'' (1966): 225–240

in JSTOR

* Olin, Spencer C. "European Immigrant and Oriental Alien: Acceptance and Rejection by the California Legislature of 1913." ''Japanese Immigrants and American Law'' (Routledge, 2019) pp. 331–343

online

* Shover, John L. "The Progressives and the Working Class Vote in California." ''Labor History'' (1969) 10#4 pp: 584–601

online

* Weatherson, Michael A., and Hal Bochin. ''Hiram Johnson: Political Revivalist'' (University Press of America, 1995) * Weatherson, Michael A., and Hal Bochin. ''Hiram Johnson: A Bio-Bibliography'' (Greenwood Press, 1988)

Unpublished PhD dissertations that are online

* Dewitt, Howard Arthur. "Hiram W. Johnson and American Foreign Policy, 1917-1941" (The University Of Arizona; Proquest Dissertations Publishing, 1972. 7215602). * Fitzpatrick, John James, III. "Senator Hiram W. Johnson: A Life History, 1866-1945." (University Of California, Berkeley; Proquest Dissertations Publishing, 1975. 7526691). * Liljekvist, Clifford B. "Senator Hiram Johnson" (University Of Southern California; Proquest Dissertations Publishing, 1953. Dp28687) * Nichols, Egbert R. Jr. "An Investigation Of The Contributions Of The Public Speaking Of Hiram W. Johnson To His Political Career" (University Of Southern California; Proquest Dissertations Publishing, 1948. 0154027). * Weatherson, Michael Allen. "A Political Revivalist: The Public Speaking Of Hiram W. Johnson, 1866-1945" (Indiana University; Proquest Dissertations Publishing, 1985. 8516663).Primary sources

* Johnson, Hiram. ''The Diary Letters of Hiram Johnson, 1917–1945'' (Vol. 1. Garland Publishing, 1983)External links

*Guide to the Hiram Johnson Papers

at the Bancroft Library *

California Progressive Campaign for 1914 Three Years of Progressive Administration in California Under Governor Hiram W. Johnson

Archives

Robert E. Burke Collection.

1892–1994. 60.43 cubic feet (68 boxes plus two oversize folders and one oversize vertical file). At th

Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Libraries Special Collections.

Contains materials collected by Burke on Hiram Johnson from 1910 to 1994. , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Johnson, Hiram Warren 1866 births 1912 United States vice-presidential candidates 1945 deaths 20th-century American Episcopalians American people of French descent American segregationists Anti-Japanese sentiment Articles containing video clips Burials at Cypress Lawn Memorial Park California Progressives (1912) Candidates in the 1920 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1924 United States presidential election Deaths from thrombosis Direct democracy activists District attorneys in California Republican Party governors of California Heald College alumni History of San Francisco Politicians from Sacramento, California Politicians from San Francisco Progressive Party (1912) state governors of the United States Republican Party United States senators from California University of California, Berkeley alumni 20th-century United States senators