The High Court of Australia is the

apex court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

of the

Australian legal system

The legal system of Australia has multiple forms. It includes a written Constitution of Australia, constitution, unwritten Constitutional convention (political custom)#Australia, constitutional conventions, statutes, Delegated legislation in the ...

. It exercises

original

Originality is the aspect of created or invented works that distinguish them from reproductions, clones, forgeries, or substantially derivative works. The modern idea of originality is according to some scholars tied to Romanticism, by a notion t ...

and

appellate jurisdiction

An appellate court, commonly called a court of appeal(s), appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear a case upon appeal from a trial court or other lower tribunal. Appellat ...

on matters specified in the

Constitution of Australia

The Constitution of Australia (also known as the Commonwealth Constitution) is the fundamental law that governs the political structure of Australia. It is a written constitution, which establishes the country as a Federation of Australia, ...

and supplementary legislation.

The High Court was established following the passage of the

''Judiciary Act 1903'' (Cth).

Its authority

derives from chapter III of the Australian Constitution, which vests it (and other courts the Parliament creates) with the

judicial power

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

of the Commonwealth. Its internal processes are governed by the ''High Court of Australia Act 1979'' (Cth).

The court consists of seven justices, including a

chief justice, currently

Stephen Gageler

Stephen John Gageler (; born 5 July 1958) is an Australian judge and former barrister. He has been a Justice of the High Court of Australia since 2012 and was appointed Chief Justice of Australia in 2023. He previously served as Solicitor-Gene ...

. Justices of the High Court are appointed by the

governor-general

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

on the formal

advice of the

attorney-general

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

following the approval of the

prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

and

Cabinet. They are appointed permanently until their mandatory retirement at age 70, unless they retire earlier.

Typically, the court operates by receiving applications for appeal from parties in a process called

special leave. If a party's application is accepted, the court will proceed to a full hearing, usually with oral and written submissions from both parties. After conclusion of the hearing, the result is decided by the court. The special leave process does not apply in situations where the court elects to exercise its original jurisdiction; however, the court typically delegates its original jurisdiction to Australia's inferior courts.

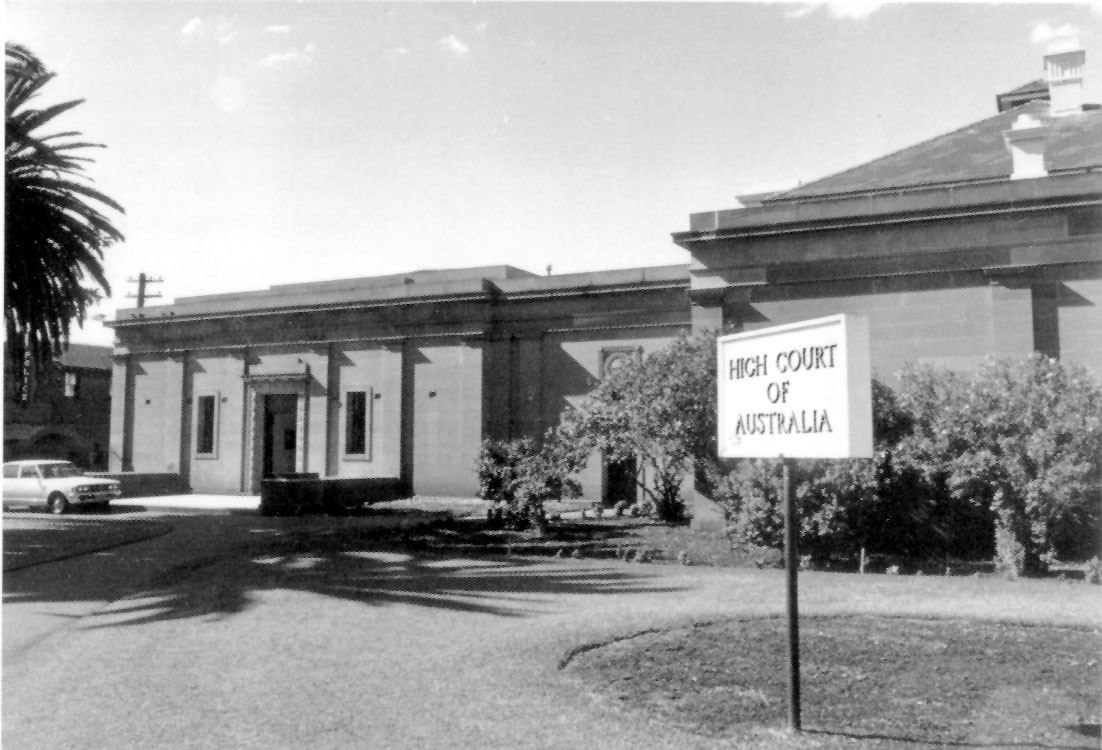

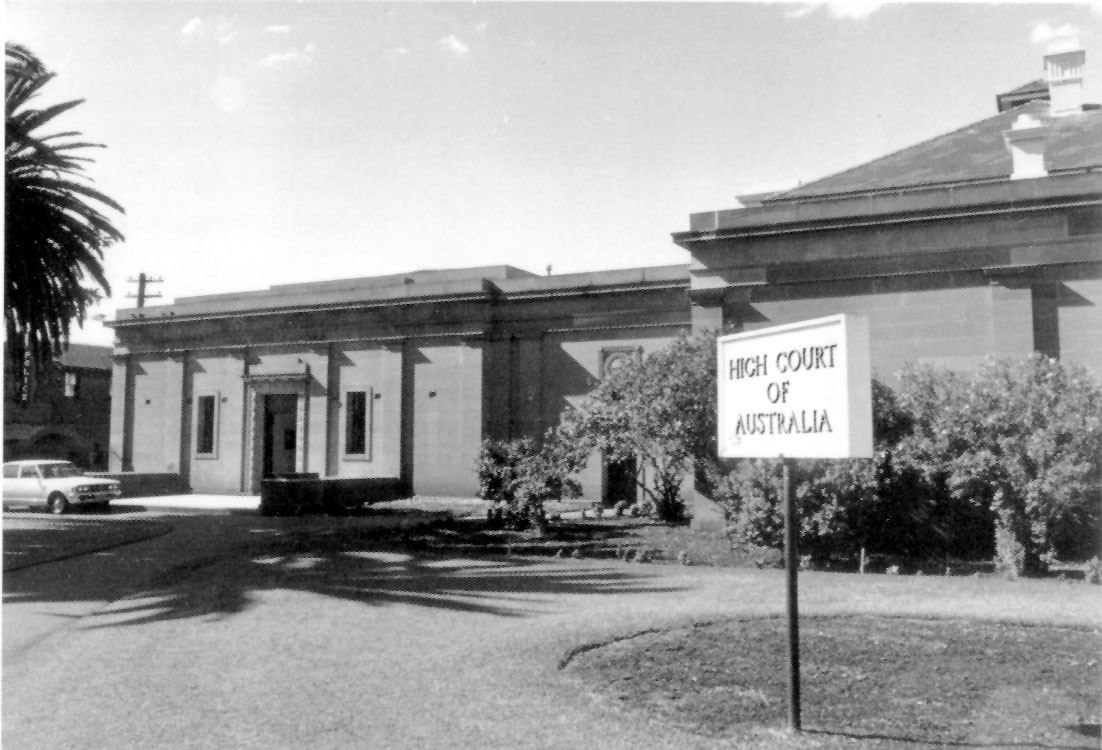

The court has resided in

Canberra

Canberra ( ; ) is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the Federation of Australia, federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's list of cities in Australia, largest in ...

since 1980, following the construction of a purpose-built

High Court building, located in the

Parliamentary Triangle

The National Triangle, also known as the Parliamentary Triangle, is the ceremonial precinct of Canberra, containing some of Australia's most significant buildings. The Triangle is formed by Commonwealth, Kings and Constitution Avenues. Buildin ...

and overlooking

Lake Burley Griffin

Lake Burley Griffin is an artificial lake in the centre of Canberra, the capital of Australia. It was created in 1963 by the damming of the Molonglo River, which formerly ran between the city centre and Parliamentary Triangle. The lake is na ...

.

[

] Sittings of the court previously rotated between state capitals, particularly

Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

and

Sydney

Sydney is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales and the List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city in Australia. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Syd ...

, and the court continues to regularly sit outside Canberra.

Role

The High Court exercises both

original

Originality is the aspect of created or invented works that distinguish them from reproductions, clones, forgeries, or substantially derivative works. The modern idea of originality is according to some scholars tied to Romanticism, by a notion t ...

and

appellate jurisdiction

An appellate court, commonly called a court of appeal(s), appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear a case upon appeal from a trial court or other lower tribunal. Appellat ...

.

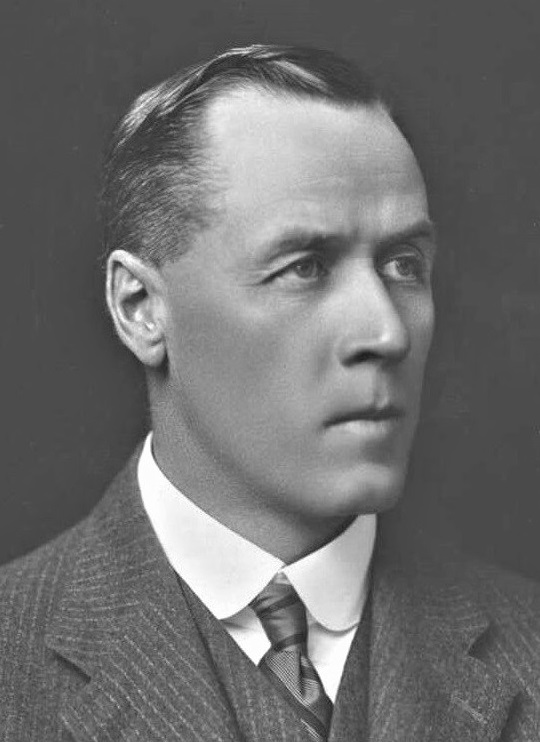

Sir

Owen Dixon

Sir Owen Dixon (28 April 1886 – 7 July 1972) was an Australian judge and diplomat who served as the sixth Chief Justice of Australia. Many consider him to be Australia's most prominent jurist.Graham Perkin �Its Most Eminent Symbol Hidde ...

said on his swearing in as Chief Justice of Australia in 1952:

[ Not online.]

The High Court's jurisdiction is divided in its exercise between constitutional and federal cases which loom so largely in the public eye, and the great body of litigation between man and man, or even man and government, which has nothing to do with the Constitution, and which is the principal preoccupation of the court

The broad jurisdiction of the High Court means that it has an important role in Australia's legal system.

Original jurisdiction

Its original jurisdiction is determined by sections 75 and 76 of Australia's Constitution. Section 75 confers original jurisdiction in all matters:

Section 76 provides that Parliament may confer original jurisdiction in relation to matters:

Constitutional matters, referred to in section 76(i), were conferred on the High Court by section 30 of the ''

Judiciary Act 1903''.

While the conferral of constitutional matters might be removed by amending the Judiciary Act, section 75(iii) (suing the Commonwealth) and section 75(iv) (conflicts between states) are broad enough that many constitutional matters would still be within original jurisdiction. The original constitutional jurisdiction of the High Court is now well established; the

Australian Law Reform Commission

The Australian Law Reform Commission (often abbreviated to ALRC) is an Australian independent statutory body established to conduct reviews into the law of Australia. The reviews, also called inquiries or references, are referred to the ALRC by ...

has described the reference to constitutional matters in section 76 rather than in section 75 as "an odd fact of history".

The

1998 Constitutional Convention

The 1998 Australian Constitutional Convention, also known as the Con Con, was a constitutional convention which gathered at Old Parliament House, Canberra from 2 to 13 February 1998. It was called by the Howard government to discuss whether A ...

recommended an amendment to the constitution to prevent the possibility of the jurisdiction being removed by Parliament.

The word "matter" in sections 75 and 76 has been understood to mean that the High Court is unable to give

advisory opinion

An advisory opinion of a court or other government authority, such as an election commission, is a decision or opinion of the body but which is non-binding in law and does not have the effect of adjudicating a specific legal case, but which merely ...

s.

Appellate jurisdiction

The court is empowered by section 73 of the Constitution to hear appeals from the supreme courts of the states and territories; as well as any court exercising federal jurisdiction.

[Examples of courts exercising federal jurisdiction include the ]Federal Court of Australia

The Federal Court of Australia is an Australian superior court which has jurisdiction to deal with most civil disputes governed by federal law (with the exception of family law matters), along with some summary (less serious) and indictable (mo ...

, and the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia

The Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia is an Australian court formed in September 2021 from the merger of the Federal Circuit Court of Australia and the Family Court of Australia. It has jurisdiction over family law in Australia, ap ...

It may also hear appeals of decisions made in an exercise of its own original jurisdiction.

[e.g. such as a decision made by a single justice of the High Court exercising its original jurisdiction]

The High Court's appellate jurisdiction is limited by the ''

Judiciary Act'', which requires special leave to be granted before the hearing of an appeal.

Special leave may only be granted where a question of law is raised which is of public importance, involves a conflict between courts or "is in the interests of the administration of justice".

Since November 2023, the High Court has adopted the practice of deciding the majority of special leave applications on the basis of written submissions only. In adopting this practice, the High Court also made the decision to publish decisions in special leave applications on its public website rather than in open court.

Appeals to the Privy Council

Appeals to the United Kingdom's

Privy Council were a notable controversy when the Constitution was drafted. Section 74 of the Constitution as it was put to voters, stated that there would be no appeals to the Privy Council in any matter involving the interpretation of the Constitution or state constitutions.

[Excepting for situations in which the controversy involved the interests of some other dominion]

The section as enacted by the Imperial Parliament was different. It only prohibited appeals on constitutional disputes regarding the respective powers of the states and the Commonwealth ("''inter se''" matters), except where the High Court certified it appropriate for the appeal to be determined by Privy Council. This occurred only once,

[In '']Colonial Sugar Refining Co Ltd v Attorney-General (Cth)

''Colonial Sugar Refining Co Ltd v Attorney-General (Cth)'',. is the only case in which the High Court issued a certificate under section 74 of the Constitution to permit an appeal to the Privy Council on a constitutional question. The Priv ...

'' 912HCA 94, (1912) 15 CLR 182. The High Court was equally divided prior to certification being granted and the High Court has said it would never again grant a certificate of appeal.

[.] No certificate was required to appeal constitutional cases not involving ''inter se'' matters, such as in the interpretation of section 92 (the freedom of inter-state commerce section).

On non-''inter se'' matters, the Privy Council regularly heard appeals against High Court decisions. In some cases the Council acknowledged that the Australian common law had developed differently from English law and thus did not apply its own principles.

[.][.] Other times it followed English authority, and overruled decisions of the High Court.

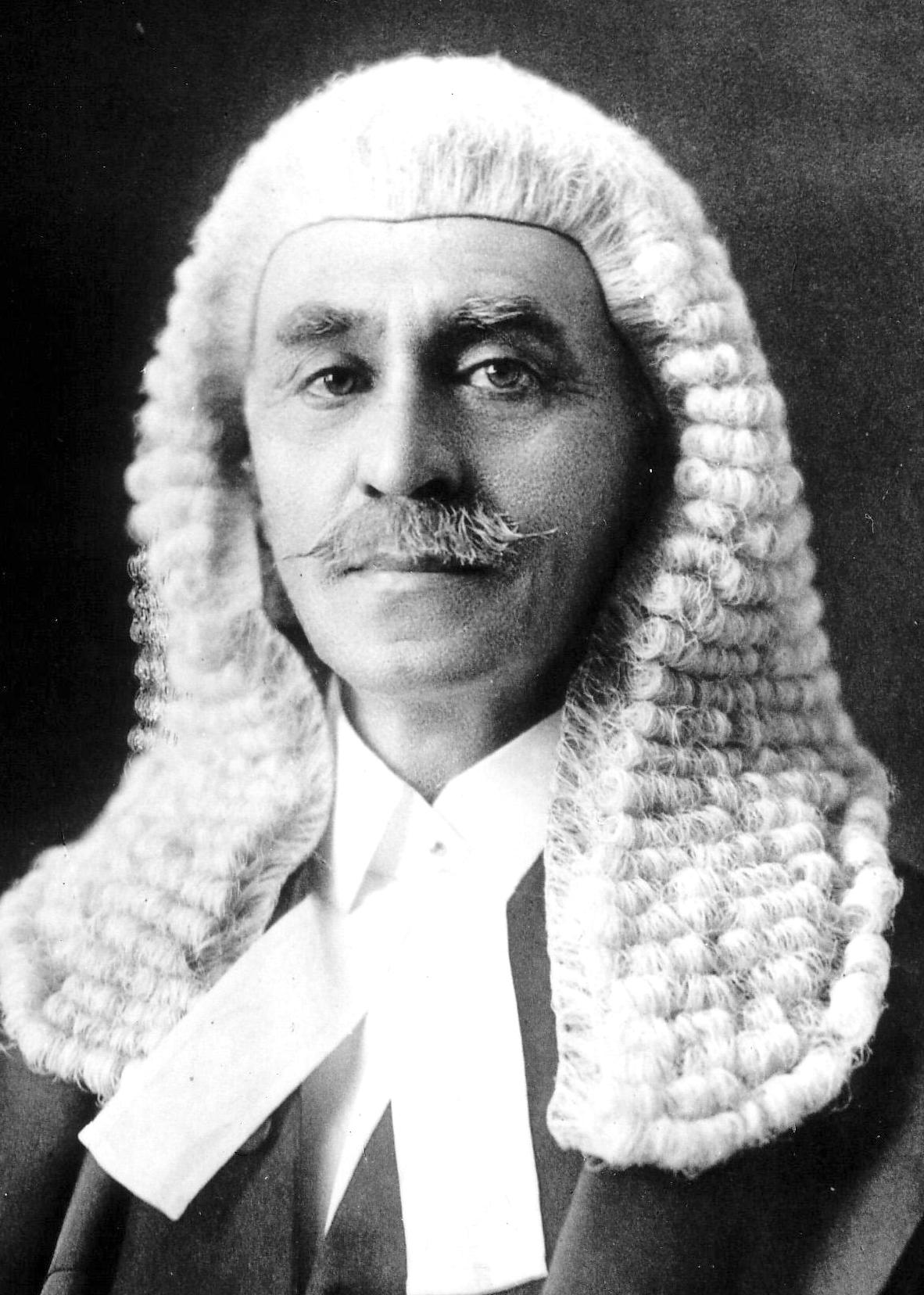

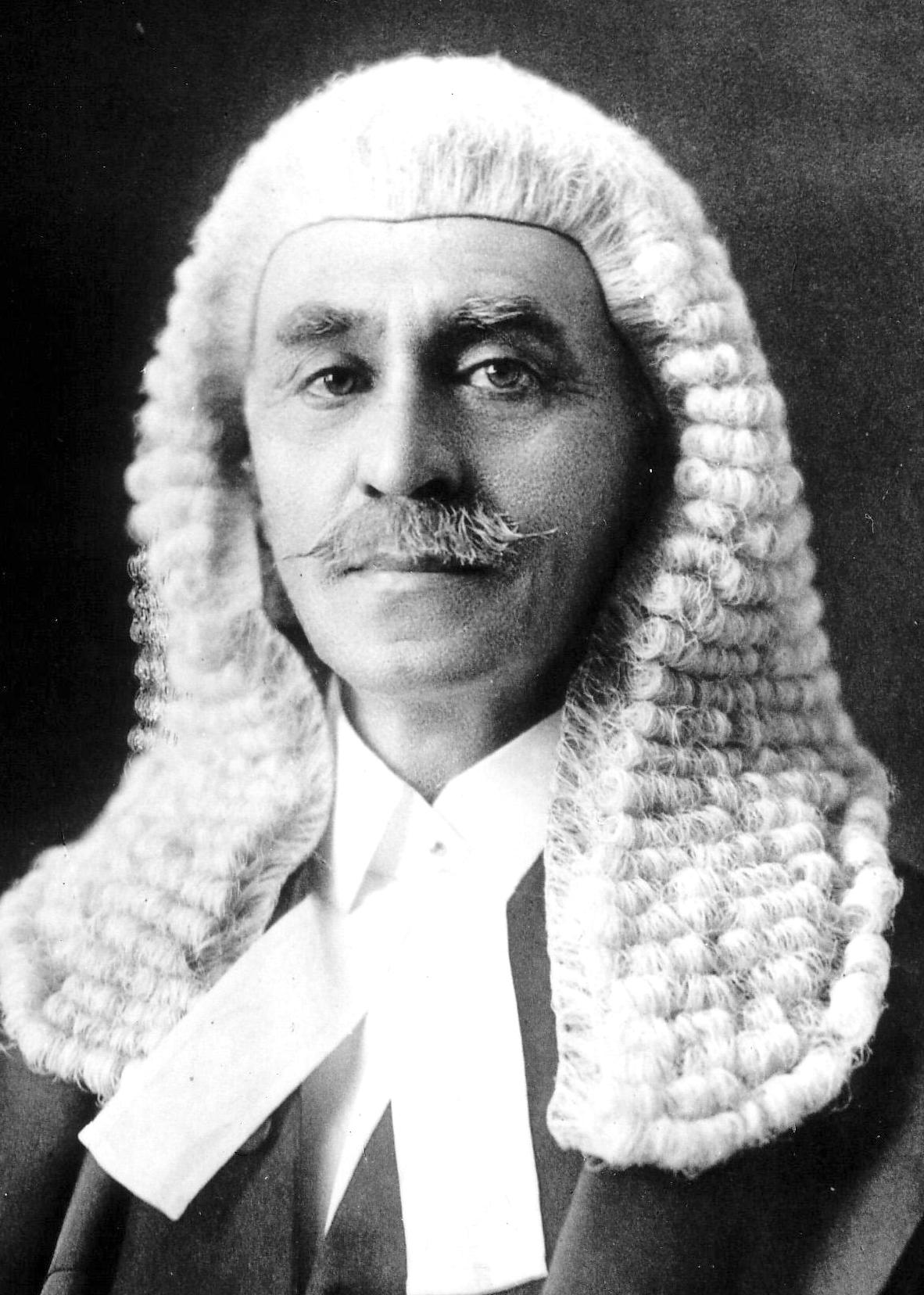

This arrangement led to tensions between the High Court and the Privy Council. In ''Parker v The Queen'' (1964), Chief Justice Sir

Owen Dixon

Sir Owen Dixon (28 April 1886 – 7 July 1972) was an Australian judge and diplomat who served as the sixth Chief Justice of Australia. Many consider him to be Australia's most prominent jurist.Graham Perkin �Its Most Eminent Symbol Hidde ...

led a unanimous judgment rejecting the authority of the

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

decision in ''

DPP v Smith'', writing, "I shall not depart from the law on this matter as we have long since laid it down in this Court and I think that Smith's case should not be used in Australia as authority at all."

[.] The Privy Council overturned this by enforcing the UK precedent upon the High Court the following year.

[; .]

Thirteen High Court judges have heard cases as part of the Privy Council.

Sir Isaac Isaacs is the only judge to have sat on an appeal from the High Court, in 1936 after his retirement as

Governor-General of Australia.

insisted on an amendment to Privy Council procedure to allow dissent; however, he exercised that capacity only once. The appeals mostly related to decisions from other Commonwealth countries, although they occasionally included appeals from the supreme court of an Australian state.

Abolition of Privy Council appeals

Section 74 allowed parliament to prevent appeals to the Privy Council. It did so in 1968 with the ''

Privy Council (Limitation of Appeals) Act 1968'', which closed off all appeals to the Privy Council in matters involving federal legislation. In 1975, the ''

Privy Council (Appeals from the High Court) Act 1975'' closed all routes of appeal from the High Court; excepting for those in which a certificate of appeal would be granted by the High Court.

In 1986, with the passing of the ''

Australia Act'' by both the

UK Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of ...

and the Commonwealth Parliament (with the request and consent of the states' Parliaments), appeals to the Privy Council from state supreme courts were closed off, leaving the High Court as the only avenue of appeal. In 2002,

Chief Justice Murray Gleeson

Anthony Murray Gleeson (born 30 August 1938) is an Australian former judge who served as the 11th Chief Justice of Australia, in office from 1998 to 2008.

Gleeson was born in Wingham, New South Wales, and studied law at the University of Sydn ...

said that the "combined effect" of the legislation and the announcement in ''Kirmani'' "has been that s 74 has become a dead letter, and what remains of s 74 after the legislation limiting appeals to the Privy Council will have no further effect".

Appellate jurisdiction for Nauru

On 6 September 1976, Australia and

Nauru

Nauru, officially the Republic of Nauru, formerly known as Pleasant Island, is an island country and microstate in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies within the Micronesia subregion of Oceania, with its nearest neighbour being Banaba (part of ...

, which was newly-independent from Australia, signed an agreement for the High Court to become Nauru's apex court.

[an amendment to Nauru's constitution was made to allow this (section 57)] It was empowered to hear appeals from the

Supreme Court of Nauru

The Supreme Court of Nauru was the highest court in the judicial system of the Republic of Nauru until the establishment of the Nauruan Court of Appeal in 2018.

Constitutional establishment

It was established by part V of the Constitution, ...

in both criminal and civil cases, but not constitutional matters. There were a total of five appeals to the High Court under this agreement in the first 40 years of its operation. In 2017, however, this jumped to 13 appeals, most relating to asylum seekers.

At the time some legal commentators argued that this appellate jurisdiction sat awkwardly with the High Court's other responsibilities, and ought be renegotiated or repealed. Anomalies included the need to apply Nauruan law and customary practice, and that special leave hearings were not required.

Nauruan politicians

[such as the former Justice Minister Matthew Batsiua] had said publicly that the Nauru government was unhappy about these arrangements.

Of particular concern was a decision of the High Court in October 2017, which quashed an increase in sentence imposed upon political protestors by the Supreme Court of Nauru.

The High Court had remitted the case to the Supreme Court "differently constituted, for hearing according to law".

On Nauru's 50th anniversary of independence,

Baron Waqa

Baron Divavesi Waqa (; born 31 December 1959) is a Nauruan politician who currently serves as the Secretary General of the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, secretary-general of the Pacific Islands Forum. He was the President of Nauru from 11 Ju ...

declared to parliament that "

verance of ties to Australia's highest court is a logical step towards full nationhood and an expression of confidence in Nauru's ability to determine its own destiny".

Justice Minister

David Adeang

David Ranibok Waiau Adeang (born 24 November 1969) is a Nauruan politician, currently serving as President of Nauru. Adeang is the former Speaker of the Parliament of Nauru, and Nauru's Minister of Finance and Justice, as well as the Minist ...

said that an additional reason for cutting ties was the cost of appeals to the High Court. Nauru then exercised an option under its agreement with Australia to end its appellate arrangement with 90 days notice. The option was exercised on 12 December 2017 and the High Court's jurisdiction ended on 12 March 2018.

The termination did not become publicly known until after the Supreme Court had reheard the case of the protesters and had again imposed increased sentences.

In 2022, Australia passed legislation which removed the possibility for reinstatement of the appeal pathway.

History

Pre-establishment

Following

Earl Grey

Earl Grey is a title in the peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1806 for General Charles Grey, 1st Baron Grey. In 1801, he was given the title Baron Grey of Howick in the County of Northumberland, and in 1806 he was created Viscoun ...

's 1846 proposal to federate the colonies, an 1849 report from the Privy Council suggested a national court be created.

In 1856, the

Governor of South Australia

The governor of South Australia is the representative in South Australia of the monarch, currently King Charles III. The governor performs the same constitutional and ceremonial functions at the state level as does the governor-general of Aust ...

,

Richard MacDonnell, suggested to the

Government of South Australia

The Government of South Australia, also referred to as the South Australian Government or the SA Government, is the executive branch of the state government, state of South Australia. It is modelled on the Westminster system, meaning that the h ...

that they consider establishing a court to hear appeals from the Supreme Courts in each colony. In 1860 the

South Australian Parliament passed legislation encouraging MacDonnell to put the idea to the other colonies. However, only

Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Queen Victoria (1819–1901), Queen of the United Kingdom and Empress of India

* Victoria (state), a state of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, a provincial capital

* Victoria, Seychelles, the capi ...

considered the proposal.

At a

Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

inter-colonial conference held in 1870, the idea of an inter-colonial court was again raised. A

royal commission

A royal commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue in some monarchies. They have been held in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Norway, Malaysia, Mauritius and Saudi Arabia. In republics an equi ...

was established in Victoria to investigate options for establishing such a court, and a draft bill was put forward. This draft bill, however, completely excluded appeals to the Privy Council, causing a reaction in London which prevented any serious attempt to implement the bill through the

British Imperial Parliament.

Another draft bill was proposed in 1880 for the establishment of an Australasian court of appeal. The proposed court would consist of one judge from each of the colonial supreme courts, who would serve one-year terms.

[New Zealand, which was at the time also considering joining the Australian colonies in federation, was also to be a participant in the new court.] However, the proposed court allowed for appeals to the Privy Council, which was disliked by some of the colonies, and the bill was abandoned.

Constitutional conventions

The idea of a federal supreme court was raised during the

Constitutional Conventions of the 1890s. A proposal for a supreme court of Australia was included in an 1891 draft. It was proposed to enable the court to hear appeals from the state supreme courts, with appeals to the Privy Council only occurring on assent from the

British monarch

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with their powers regulated by the British con ...

. It was proposed that the Privy Council be prevented from hearing appeals on constitutional matters.

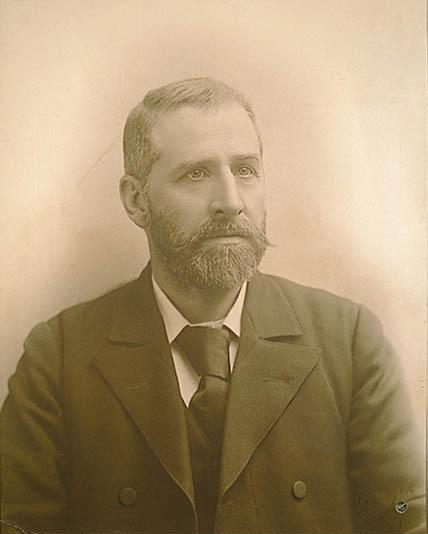

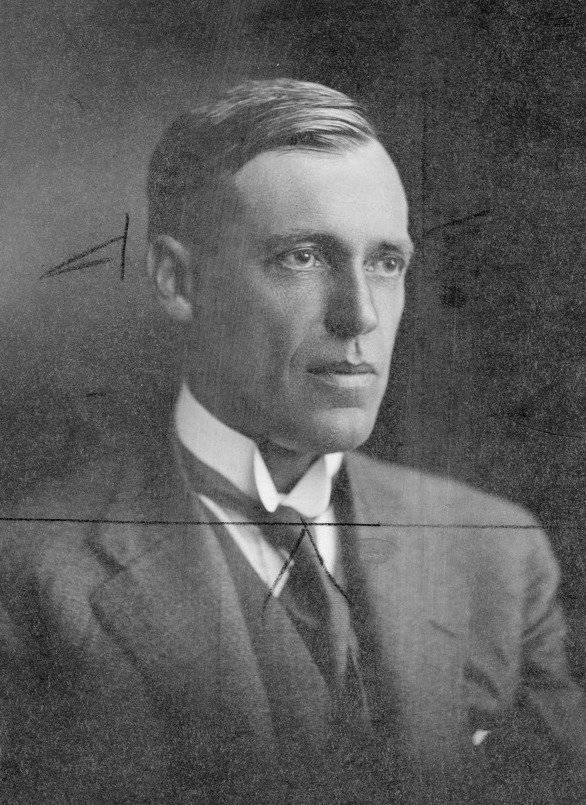

This draft was largely the work of

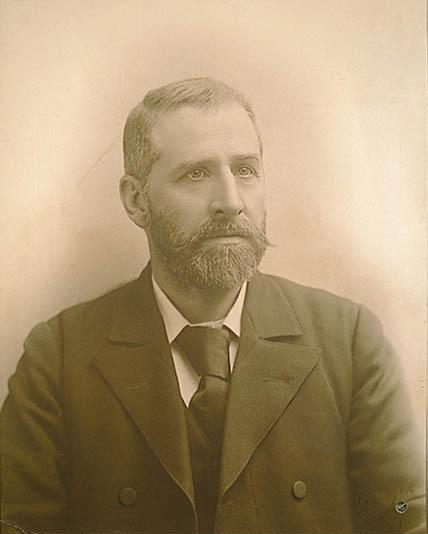

Sir Samuel Griffith

Sir Samuel Walker Griffith (21 June 1845 – 9 August 1920) was an Australian judge and politician who served as the inaugural Chief Justice of Australia, in office from 1903 to 1919. He also served a term as Chief Justice of Queensland and t ...

,

then the

Premier of Queensland

The premier of Queensland is the head of government in the Australian state of Queensland.

By convention the premier is the leader of the party with a parliamentary majority in the Legislative Assembly of Queensland. The premier is appointed ...

. The attorney-general of Tasmania

Andrew Inglis Clark

Andrew Inglis Clark (24 February 1848 – 14 November 1907) was an Australian founding father and co-author of the Australian Constitution; he was also an engineer, barrister, politician, electoral reformer and jurist. He initially qualified as ...

also contributed to the constitution's judicial clauses. Clark's most significant contribution was to give the court its own constitutional authority, ensuring a

separation of powers

The separation of powers principle functionally differentiates several types of state (polity), state power (usually Legislature#Legislation, law-making, adjudication, and Executive (government)#Function, execution) and requires these operat ...

. The original formulation of Griffith,

Barton and

Kingston

Kingston may refer to:

Places

* List of places called Kingston, including the six most populated:

** Kingston, Jamaica

** Kingston upon Hull, England

** City of Kingston, Victoria, Australia

** Kingston, Ontario, Canada

** Kingston upon Thames, ...

provided only that the parliament could establish a court.

The draft was later amended at various conventions.

[In ]Adelaide

Adelaide ( , ; ) is the list of Australian capital cities, capital and most populous city of South Australia, as well as the list of cities in Australia by population, fifth-most populous city in Australia. The name "Adelaide" may refer to ei ...

in 1897, in Sydney

Sydney is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales and the List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city in Australia. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Syd ...

later the same year and in Melbourne in early 1898 In Adelaide the court's proposed name was changed to be the "High Court of Australia".

Many people opposed the idea of the new court completely replacing the Privy Council. Commercial interests, particularly subsidiaries of British companies, preferred to operate under the unified jurisdiction of the British courts, and petitioned the conventions to that effect.

Others argued that Australian judges were of a poorer quality than British, and that the inevitable divergence in law that would occur without the oversight of the Privy Council would put the legal system at risk.

Some politicians (e.g.

George Dibbs

Sir George Richard Dibbs KCMG (12 October 1834 – 5 August 1904) was an Australian politician who was Premier of New South Wales on three occasions.

Early years

Dibbs was born in Sydney, son of Captain John Dibbs, who 'disappeared' in the ...

) supported a retention of Privy Council supervision; whereas others, including

Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin (3 August 1856 – 7 October 1919) was an Australian politician who served as the second Prime Minister of Australia, prime minister of Australia from 1903 to 1904, 1905 to 1908, and 1909 to 1910. He held office as the leader of th ...

, supported the design of the court as it was.

Inglis Clark took the view that the possibility of divergence was a good thing, for the law could adapt appropriately to Australian circumstances.

Despite this debate, the draft's judicial sections remained largely unchanged.

After the draft had been approved by the electors of the colonies, it was taken to London in 1899 for the assent of the British Imperial Parliament. The issue of Privy Council appeals remained a sticking point however; with objections made by

Secretary of State for the Colonies

The secretary of state for the colonies or colonial secretary was the Cabinet of the United Kingdom's government minister, minister in charge of managing certain parts of the British Empire.

The colonial secretary never had responsibility for t ...

,

Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal Party (UK), Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually was a leading New Imperialism, imperial ...

, the Chief Justice of South Australia,

Sir Samuel Way, and

Samuel Griffith

Sir Samuel Walker Griffith (21 June 1845 – 9 August 1920) was an Australian judge and politician who served as the inaugural Chief Justice of Australia, in office from 1903 to 1919. He also served a term as Chief Justice of Queensland and ...

, among others.

In October 1899, Griffith made representations to Chamberlain soliciting suggestions from British ministers for alterations to the draft, and offered alterations of his own.

Indeed, such was the effect of these and other representations that Chamberlain called for delegates from the colonies to come to London to assist with the approval process, with a view to their approving any alterations that the British government might see fit to make; delegates were sent, including Deakin, Barton and

Charles Kingston

Charles Cameron Kingston (22 October 1850 – 11 May 1908) was an Australian politician. From 1893 to 1899 he was a radical liberal Premier of South Australia, occupying this office with the support of Labor, which in the House of Assembly ...

, although they were under instructions that they would never agree to changes.

After intense lobbying both in Australia and in the United Kingdom, the Imperial Parliament finally approved the draft constitution. The draft as passed included an alteration to section 74, in a compromise between the two sides. It allowed for a general right of appeal from the High Court to the Privy Council, but the Parliament of Australia could make laws restricting this avenue. In addition, appeals in ''inter se''

[(matters concerning the boundary between and limits of the powers of the Commonwealth and the powers of the states)] matters were not as of right, but had to be certified by the High Court.

Formation of the court

The High Court was not immediately established after Australia came into being. Some

members of the first Parliament, including

Sir John Quick, then one of the leading legal experts in Australia, opposed legislation to set up the court. Even

H. B. Higgins, who was himself later appointed to the court, objected to setting it up, on the grounds that it would be impotent while Privy Council appeals remained, and that in any event there was not enough work for a federal court to make it viable.

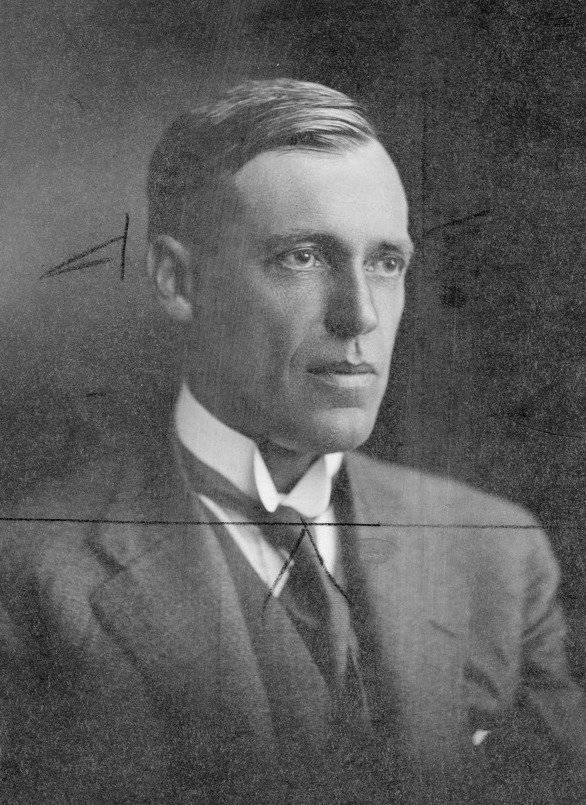

The then

Attorney-General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

Alfred Deakin introduced the ''Judiciary Bill'' to the

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

in 1902. Prior efforts had been continually delayed by opponents in the parliament, and the success of the bill is generally attributed to Deakin's passion and persistence.

Deakin proposed that the court be composed of five judges, specially selected to the court. Opponents instead proposed that the court should be made up of state supreme court justices, taking turns to sit on the High Court on a rotation basis, as had been mooted at the Constitutional Conventions a decade before.

Deakin eventually negotiated amendments with the

opposition, reducing the number of judges from five to three, and eliminating financial benefits such as pensions.

At one point, Deakin threatened to resign as Attorney-General due to the difficulties he faced.

In his three and a half hour

second reading

A reading of a bill is a stage of debate on the bill held by a general body of a legislature.

In the Westminster system, developed in the United Kingdom, there are generally three readings of a bill as it passes through the stages of becoming ...

speech to the

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

, Deakin said,

The federation is constituted by distribution of powers, and it is this court which decides the orbit and boundary of every power... It is properly termed the keystone of the federal arch... The statute stands and will stand on the statute-book just as in the hour in which it was assented to. But the nation lives, grows and expands. Its circumstances change, its needs alter, and its problems present themselves with new faces. he High Courtenables the Constitution to grow and be adapted to the changeful necessities and circumstances of generation after generation that the High Court operates.

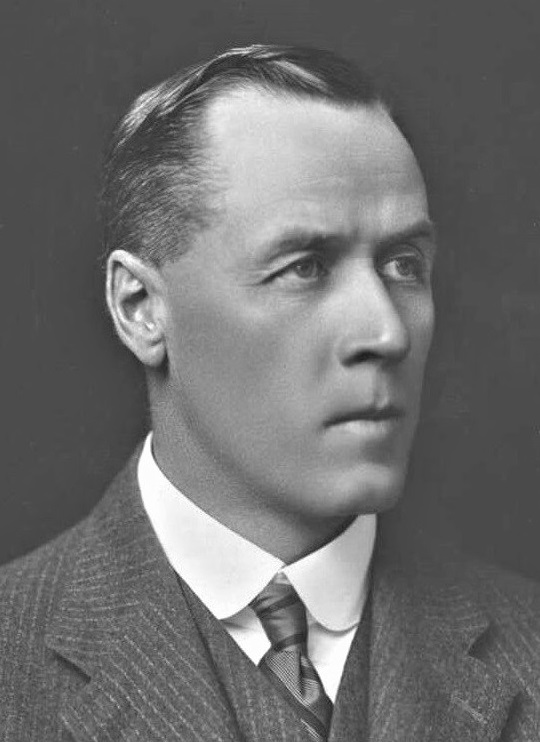

Deakin's friend, painter

Tom Roberts

Thomas William Roberts (8 March 185614 September 1931) was an English-born Australian artist and a key member of the Heidelberg School art movement, also known as Australian impressionism.

After studying in Melbourne, he travelled to Europe i ...

, who viewed the speech from the public gallery, declared it Deakin's "''magnum opus''".

The Judiciary Act 1903 was finally passed on 25 August 1903, and the first three justices, Chief Justice Sir Samuel Griffith and justices

Sir Edmund Barton

''Sir'' is a formal honorific address in English for men, derived from Sire in the High Middle Ages. Both are derived from the old French "" (Lord), brought to England by the French-speaking Normans, and which now exist in French only as part ...

and

Richard O'Connor

General (United Kingdom), General Sir Richard Nugent O'Connor, (21 August 1889 – 17 June 1981) was a senior British Army Officer (armed forces), officer who fought in both the First World War, First and Second World Wars, and commanded the ...

, were appointed on 5 October of that year. On 6 October, the court held its first sitting in the

Banco Court in the

Supreme Court of Victoria

The Supreme Court of Victoria is the highest court in the Australian state of Victoria. Founded in 1852, it is a superior court of common law and equity, with unlimited and inherent jurisdiction within the state.

The Supreme Court compri ...

.

Early years

On 12 October 1906, the size of the High Court was increased to five justices, and Deakin appointed

H. B. Higgins and

Isaac Isaacs

Sir Isaac Alfred Isaacs, (6 August 1855 – 11 February 1948) was an Australian lawyer, politician, and judge who served as the ninth Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1931 to 1936. He had previously served on the High Court of Au ...

to the High Court. Following a court-packing attempt by the Labor Prime Minister

Andrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher (29 August 186222 October 1928) was an Australian politician and trade unionist who served as the fifth prime minister of Australia from 1908 to 1909, 1910 to 1913 and 1914 to 1915. He held office as the leader of the Australian ...

In February 1913, the bench was increased again to a total to seven.

Charles Powers

Sir Charles Powers (3 March 1853 – 24 April 1939) was an Australian politician and judge who served as Justice of the High Court of Australia from 1913 to 1929.

Early life

Powers was born in 1853 in Brisbane, Colony of New South Wales. ...

and

Albert Bathurst Piddington were appointed. These appointments generated an outcry, however, and Piddington resigned on 5 April 1913 after serving only one month as High Court justice.

The High Court continued its Banco location in

Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

until 1928, until a dedicated courtroom was built in

Little Bourke Street

Little Bourke Street in the Melbourne central business district runs roughly east–west within the Hoddle Grid. It is a one-way street heading in a westward direction. The street intersects with Spencer Street at its western end and Spring S ...

, next to the

Supreme Court of Victoria

The Supreme Court of Victoria is the highest court in the Australian state of Victoria. Founded in 1852, it is a superior court of common law and equity, with unlimited and inherent jurisdiction within the state.

The Supreme Court compri ...

. That space provided the court's Melbourne sitting place and housed the court's principal

registry until 1980.

The court also sat regularly in Sydney, sharing space in the criminal courts of

Darlinghurst Courthouse

The Darlinghurst Courthouse is a heritage register, heritage-listed courthouse building located adjacent to Taylor Square, Sydney, Taylor Square on Oxford Street, Sydney, Oxford Street in the inner city Sydney suburb of Darlinghurst, New South Wa ...

, before a dedicated courtroom was constructed next door in 1923.

The court travelled to other cities across the country, where it would use facilities of the respective supreme courts. Deakin had envisaged that the court would sit in many different locations, so as to truly be a federal court. Shortly after the court's creation, Chief Justice Griffith established a schedule for sittings in state capitals:

Hobart

Hobart ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the island state of Tasmania, Australia. Located in Tasmania's south-east on the estuary of the River Derwent, it is the southernmost capital city in Australia. Despite containing nearly hal ...

in February,

Brisbane

Brisbane ( ; ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and largest city of the States and territories of Australia, state of Queensland and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia, with a ...

in June,

Perth

Perth () is the list of Australian capital cities, capital city of Western Australia. It is the list of cities in Australia by population, fourth-most-populous city in Australia, with a population of over 2.3 million within Greater Perth . The ...

in September, and Adelaide in October. It has been said that Griffith established this schedule because those were the times of year he found the weather most pleasant in each city.

The tradition of special sittings remains to this day, although they are dependent on the court's caseload. There are annual sittings in Perth, Adelaide and Brisbane for up to a week each year, and sittings in Hobart occur once every few years. Sittings outside of these special occurrences are conducted in Canberra.

The court's operations were marked by various anomalies during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. The Chief Justice,

Sir John Latham, served from 1940 to 1941 as Australia's first ambassador to Japan; however, his activities in that role were limited by a pact Japan had entered with the

Axis powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

prior to his arrival in

Tokyo

Tokyo, officially the Tokyo Metropolis, is the capital of Japan, capital and List of cities in Japan, most populous city in Japan. With a population of over 14 million in the city proper in 2023, it is List of largest cities, one of the most ...

.

Owen Dixon was also absent for several years of his appointment, while serving as Australia's minister to the United States in

Washington

Washington most commonly refers to:

* George Washington (1732–1799), the first president of the United States

* Washington (state), a state in the Pacific Northwest of the United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A ...

.

acted as chief justice during Latham's absence.

Post-war period

From 1952, with the appointment of Sir Owen Dixon as chief justice, the court entered a period of stability. After World War II, the court's workload continued to grow, particularly from the 1960s onwards, putting pressures on the court.

, who was

attorney-general

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

from 1958 to 1964, and from then until 1981 chief justice, proposed that more federal courts be established, as permitted under the Constitution. In 1976 the

Federal Court of Australia

The Federal Court of Australia is an Australian superior court which has jurisdiction to deal with most civil disputes governed by federal law (with the exception of family law matters), along with some summary (less serious) and indictable (mo ...

was established, with a general federal jurisdiction, and in more recent years the

Family Court

Family courts were originally created to be a Court of Equity convened to decide matters and make orders in relation to family law, including custody of children, and could disregard certain legal requirements as long as the petitioner/plaintif ...

and

Federal Magistrates Court

The Federal Circuit Court of Australia, formerly known as the Federal Magistrates Court of Australia or the Federal Magistrates Service, was an Australian court with jurisdiction over matters broadly relating to family law and child support, a ...

have been set up to reduce the court's workload in specific areas.

In 1968, appeals to the Privy Council in matters involving federal legislation were barred. In 1986, with the passage of the

Australia Acts direct appeals to the Privy Council from state Supreme Courts were also closed off.

The life tenure of High Court justices ended in 1977. A national referendum in May 1977 approved the ''

Constitution Alteration (Retirement of Judges) 1977'', which upon its commencement on 29 July 1977 amended section 72 of the Constitution so as require that all justices appointed from then on must retire on attaining the age of 70 years.

The ''High Court of Australia Act 1979'' (Cth), which commenced on 21 April 1980, gave the High Court power to administer its own affairs and prescribed the qualifications for, and method of appointment of, its Justices.

Legal history

Historical periods of the High Court are commonly denoted by reference to the chief justice of the time. However, the chief justice is not always the most influential figure on the Court.

[For example; Isaacs J was the primary force in the Knox Court, while his own tenure as Chief Justice saw Dixon J emerge as the Court's leading jurist]

Griffith court: 1903–1919

The first court under Chief Justice Griffith laid the foundations of Australia's constitutional law. The court was conscious of its position as Australia's new court of appeal, and made efforts to establish its authority at the top of Australia's court hierarchy. In ''

Deakin v Webb'' (1904)

[.] It criticised the

Victorian Supreme Court for following a Privy Council decision about the

Constitution of Canada

The Constitution of Canada () is the supreme law in Canada. It outlines Canada's system of government and the civil and human rights of those who are citizens of Canada and non-citizens in Canada. Its contents are an amalgamation of various ...

instead of its own authority.

In its early years Griffith and other federalists on the bench were dominant. Their decisions were occasionally at odds with nationalist judges such as

Sir Isaac Isaacs and

H. B. Higgins in 1906. With the death of Justice

Richard O'Connor

General (United Kingdom), General Sir Richard Nugent O'Connor, (21 August 1889 – 17 June 1981) was a senior British Army Officer (armed forces), officer who fought in both the First World War, First and Second World Wars, and commanded the ...

, in 1912; the nationalists achieved majority and Griffith's influence began to decline.

The early constitutional law decisions of the Griffith court was influenced by

US constitutional law.

[e.g. In the case of '']D'Emden v Pedder

''D'Emden v Pedder''. was a significant Australian court case decided in the High Court of Australia on 26 April 1904. It directly concerned the question of whether salary receipts of federal government employees were subject to state stamp du ...

'', which involved the application of Tasmanian stamp duty

Stamp duty is a tax that is levied on single property purchases or documents (including, historically, the majority of legal documents such as cheques, receipts, military commissions, marriage licences and land transactions). Historically, a ...

to a federal official's salary, the court adopted the doctrine of implied immunity of instrumentalities which had been established in the United States Supreme Court case of ''McCulloch v. Maryland

''McCulloch v. Maryland'', 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 316 (1819), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision that defined the scope of the U.S. Congress's legislative power and how it relates to the powers of American state legislatures. The dispute in ...

''

An important doctrine peculiar to the Griffith court was that of the

reserved state powers

The reserved powers doctrine was a principle used by the inaugural High Court of Australia in the interpretation of the Constitution of Australia, that emphasised the context of the Constitution, drawing on principles of federalism, what the Cour ...

.

[The concept was developed in such cases as '' Peterswald v Bartley'' (1904), '']R v Barger

R, or r, is the eighteenth letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ar'' (pronounced ), plural ''ars''.

The lette ...

'' (1908) and the Union Label case (1908). Under this doctrine, the Commonwealth parliament's legislative powers were to be interpreted narrowly; so as to avoid intruding on areas of power traditionally exercised by the state Parliaments prior to federation.

[.] Anthony Mason has noted that this doctrine probably helped smooth the transition to a federal system of government and "by preserving a balance between the constituent elements of the Australian federation, probably conformed to community sentiment, which at that stage was by no means adjusted to the exercise of central power".

Griffith and Sir Edmund Barton were frequently consulted by governors-general, including on the exercise of the

reserve powers

Reserve or reserves may refer to:

Places

* Reserve, Kansas, a US city

* Reserve, Louisiana, a census-designated place in St. John the Baptist Parish

* Reserve, Montana, a census-designated place in Sheridan County

* Reserve, New Mexico, a US ...

.

Knox, Isaacs and Gavan Duffy courts: 1919–1935

Knox court

Adrian Knox

Sir Adrian Knox (29 November 186327 April 1932) was an Australian lawyer and judge who served as the second Chief Justice of Australia, in office from 1919 to 1930.

Knox was born in Sydney, the son of businessman Sir Edward Knox. He studied ...

became chief justice on 18 October 1919. Justice Edmund Barton died soon after, leaving no original members. During the Knox court, Justice Isaacs Isaacs had strong influence.

Under the Knox court the

Engineers case was decided, ending the reserved state powers doctrine. The decision had lasting significance for the federal balance in Australia's political arrangements. Another significant decision was ''

Roche v Kronheimer'', in which the court relied upon the

defence power to uphold federal legislation seeking to implement Australia's obligations under the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

.

[Higgins opted to rely upon the ]external affairs power

Section 51(xxix) of the Australian Constitution is a subsection of Section 51 of the Australian Constitution that gives the Commonwealth Parliament of Australia the right to legislate with respect to "external affairs".

In recent years, most at ...

; making this the first instance where a judge attempted to rely upon the external affairs power to implement an international treaty in Australia

Isaacs court

Sir Isaac Isaacs was Chief Justice for only forty-two weeks; he left the court to be appointed

governor-general

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

. He was ill for most of his term, and few significant cases were decided in this time.

Duffy court

Sir Frank Gavan Duffy was Chief Justice for four years from 1931; but he was already 78 when appointed to the position. He was not influential, and only participated in 40% of the cases during his tenure. For the most part he gave short judgements, or joined in the judgements of his colleagues. His frequent absence resulted in many tied decisions which have no lasting value as

precedent

Precedent is a judicial decision that serves as an authority for courts when deciding subsequent identical or similar cases. Fundamental to common law legal systems, precedent operates under the principle of ''stare decisis'' ("to stand by thin ...

.

Important cases of this time include:

*''

Attorney-General (New South Wales) v Trethowan

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

''

[which considered The NSW Premier Jack Lang's attempt at abolishing the ]NSW Legislative Council

The New South Wales Legislative Council, often referred to as the upper house, is one of the two chambers of the Parliament of New South Wales, parliament of the Australian state of New South Wales. Along with the New South Wales Legislative As ...

*The

First State Garnishee case[which upheld federal legislation compelling the Lang government to repay its loans]

*''

Tuckiar v The King''

[which examined legal ethics and the treatment of Indigenous people before the Australian ]justice system

The contemporary national legal systems are generally based on one of four major legal traditions: civil law, common law, customary law, religious law or combinations of these. However, the legal system of each country is shaped by its unique hi ...

Latham court: 1935–1952

John Latham was elevated to Chief Justice in 1935. His tenure is most notable for the court's interpretation of wartime legislation, and the subsequent transition back to peace.

Most legislation was upheld as enabled by the

defence power.

[e.g. '']Andrews v Howell Andrews may refer to:

Places Australia

*Andrews, Queensland

* Andrews, South Australia

United States

* Andrews, Florida (disambiguation), various places

* Andrews, Indiana

* Andrews, Nebraska

*Andrews, North Carolina

* Andrews, Oregon

* Andrews, ...

'' (1941) and '' de Mestre v Chisholm'' (1944). The

Curtin Curtin may refer to:

Places

*Curtin, Australian Capital Territory

* Curtin, Oregon, U.S.

*Curtin Township, Centre County, Pennsylvania, U.S.

*Curtin, Nicholas County, West Virginia, U.S.

*Curtin, Webster County, West Virginia, U.S.

* RAAF Base Curt ...

Labor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

government's legislation was rarely successfully challenged, with the court recognizing a necessity that the defence power permit the federal government to govern strongly.

The court allowed for the establishment of a national

income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Tax ...

scheme in the

''First Uniform Tax case'', and upheld legislation declaring the

pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ''a ...

Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a Christian denomination that is an outgrowth of the Bible Student movement founded by Charles Taze Russell in the nineteenth century. The denomination is nontrinitarian, millenarian, and restorationist. Russell co-fou ...

denomination to be a subversive organisation.

[see: ''Jehovah's Witnesses case'']

Following the war, the court reigned in the scope of the defence power. It struck down several key planks of the

Chifley Labor government's reconstruction program, notably an attempt to

nationalise

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English)

is the process of transforming privately owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization contrasts with priv ...

the banks in the

Bank Nationalisation case (1948),

[.] and an attempt to establish a comprehensive medical benefits scheme in the

First Pharmaceutical Benefits case (1945).

[.]

Other notable cases of the era include:

*The

Communist Party case[In which the court struck down ]Menzies

Menzies is a Scottish surname, with Gaelic forms being Méinnearach and Méinn, and other variant forms being Menigees, Mennes, Mengzes, Menzeys, Mengies, and Minges.

Derivation and history

The name and its Gaelic form are probably derived f ...

Liberal government legislation banning the Communist Party of Australia

The Communist Party of Australia (CPA), known as the Australian Communist Party (ACP) from 1944 to 1951, was an Australian communist party founded in 1920. The party existed until roughly 1991, with its membership and influence having been ...

*''

Proudman v Dayman''

[which developed the ]criminal

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a State (polity), state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definiti ...

defence of honest and reasonable mistake of fact

*''

R v Burgess; Ex parte Henry

''R v Burgess; Ex parte Henry'' is a 1936 High Court of Australia case where the majority took a broad view of the external affairs power in the Constitution but held that the interstate trade and commerce power delineated trade and commerc ...

''

[presaged an expansive interpretation of the external affairs power, by upholding the implementation of an air navigation treaty]

Dixon court: 1952–1964

Owen Dixon was appointed Chief Justice in 1952, after 23 years as a Justice on the court.

During his tenure the court experienced what some have described as a "Golden Age". Dixon had strong influence on the court during this period. The court experienced a marked increase in the number of joint judgements, many of which were led by Dixon. The era has also been noted for the presence of generally good relations among the court's judges.

Notable decisions of the Dixon court include:

*The

''Boilermakers' case''[In which the applicability of the ]separation of powers

The separation of powers principle functionally differentiates several types of state (polity), state power (usually Legislature#Legislation, law-making, adjudication, and Executive (government)#Function, execution) and requires these operat ...

in protecting the judiciary

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

from interference was firmly asserted

*

''Second Uniform Tax case''[In which the continued existence of the federal government's wartime income tax scheme was upheld as constitutional]

During Dixon's time, the court came to adopt by majority several of the views he had expressed in minority years prior.

Barwick court: 1964–1981

Garfield Barwick

Sir Garfield Edward John Barwick (22 June 190313 July 1997) was an Australian judge who was the seventh and longest serving Chief Justice of Australia, in office from 1964 to 1981. He had earlier been a Liberal Party politician, serving as a ...

was appointed Chief Justice in 1964.

Among other things, the Barwick court is known for controversially deciding several cases on

tax avoidance and tax evasion

Tax noncompliance is a range of activities that are unfavorable to a government's tax system. This may include tax avoidance, which is tax reduction by legal means, and tax evasion which is the illegal non-payment of tax liabilities. The use of th ...

, almost always deciding against the taxation office. Led by Barwick himself in most judgments, the court distinguished between avoidance (legitimately minimising one's tax obligations) and evasion (illegally evading obligations). The decisions effectively nullified the anti-avoidance legislation and led to the proliferation of avoidance schemes in the 1970s, a result which drew much criticism upon the court.

Notable decisions of the Barwick court include:

*

''Bradley v Commonwealth''

*The

Concrete Pipes case[a case that marked the beginning of the modern interpretation of the ]corporations power

Section 51(00) of the Australian Constitution is a subsection of Section 51 of the Australian Constitution that gives the Commonwealth Parliament the power to legislate with respect to "foreign corporations, and trading or financial corporations f ...

; which had been interpreted narrowly since 1909. It established that the federal parliament could exercise the power to regulate at least the trading activities of corporations. Earlier interpretations had allowed only the regulation of conduct or transactions with the public

*The

Seas and Submerged Lands case[.][upholding legislation asserting sovereignty over the ]territorial sea

Territorial waters are informally an area of water where a sovereign state has jurisdiction, including internal waters, the territorial sea, the contiguous zone, the exclusive economic zone, and potentially the extended continental shelf ( ...

*The

First

First most commonly refers to:

* First, the ordinal form of the number 1

First or 1st may also refer to:

Acronyms

* Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty-Centimeters, an astronomical survey carried out by the Very Large Array

* Far Infrared a ...

and

Second

The second (symbol: s) is a unit of time derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes, and finally to 60 seconds each (24 × 60 × 60 = 86400). The current and formal definition in the International System of U ...

Territory Senators' cases

[.][.][Which concerned whether legislation allowing for the mainland territories to be represented in the Parliament of Australia was valid]

*''

Russell v Russell

The Russell case, also called the Ampthill baby case, was a series of proceedings related to the conception of Geoffrey Russell. It covered two divorce cases and the claim to the British peerage title Baron Ampthill, and the possibility of ...

''

[concerning the validity of the '']Family Law Act 1975

The ''Family Law Act 1975'' (Cth) is an Act of the Parliament of Australia. It has 15 parts and is the primary piece of legislation dealing with divorce, parenting arrangements between separated parents (whether married or not), property separ ...

''

*''

Cormack v Cope''

[a case relating to the historic 1974 joint sitting of the Parliament of Australia]

*

''Victoria v Commonwealth''

Gibbs court: 1981–1987

Sir Harry Gibbs was appointed as Chief Justice in 1981.

Among the Gibbs court's notable jurisprudence is an interpretive expansion of the Commonwealth's legislative powers.

Scholars have also noted a tendency away from the traditions of legalism and conservatism that characterised the Dixon and Barwick courts.

Notable decisions of the court include:

*''

Koowarta v Bjelke-Petersen

''Koowarta v Bjelke-Petersen'',. was a significant court case decided in the High Court of Australia on 11 May 1982. It concerned the constitutional validity of parts of the ''Racial Discrimination Act 1975'', and the discriminatory acts of th ...

''

[In which the court held 4:3 that the '']Racial Discrimination Act 1975

The ''Racial Discrimination Act 1975'' (Cth). is an Act of the Australian Parliament, which was enacted on 11 June 1975 and passed by the Whitlam government. The Act makes racial discrimination in certain contexts unlawful in Australia, and al ...

'' was validly supported by s51(xxix)

*The

Tasmanian Dams case[In which the court held that federal environmental legislation interfering with a Tasmanian dam construction was validly supported by s51(xxix)]

*''

Kioa v West

''Kioa v West'',. was a notable case decided in the High Court of Australia regarding the extent and requirements of natural justice and procedural fairness in administrative decision making. The case was also a significant factor in Australi ...

''

[In which the court expanded on the doctrines of ]natural justice

In English law, natural justice is technical terminology for the rule against bias (''nemo iudex in causa sua'') and the right to a fair hearing (''audi alteram partem''). While the term ''natural justice'' is often retained as a general conc ...

and procedural fairness

*The

Chamberlain case

*''

A v Hayden''

[concerning the botched ASIS exercise at the Sheraton Hotel in Melbourne]

Mason court: 1987–1995

Sir Anthony Mason became Chief Justice in 1987.

The Mason court is known for being one of the most legally liberal benches of the court. It was a notably stable court, with the only change in its bench being the appointment of

McHugh following

Wilson's retirement.

Some of the decisions of the court in this time were politically controversial.

[Especially ''Mabo''] Scholars have noted that the Mason court has tended to receive "high praise and stringent criticism in equal measure".

Notable decisions of the court include:

*''

Cole v Whitfield

''Cole v Whitfield'',. is a decision of the High Court of Australia. At issue was the interpretation of section 92 of the Australian Constitution, a provision which relevantly states:... trade, commerce, and intercourse among the States, whethe ...

''

[Known for resolving an interpretive controversy regarding s92 of the Constitution; a section pertaining to free trade. Prior to ''Cole v Whitfield'', the High Court was plagued with litigation on this section.]

*''

Dietrich v The Queen

''Dietrich v The Queen'' is a 1992 High Court of Australia constitutional case which established that a person accused of serious criminal charges must be granted an adjournment until appropriate legal representation is provided if they are un ...

''

[In which the court established a de facto constitutional requirement that ]legal aid

Legal aid is the provision of assistance to people who are unable to afford legal representation and access to the court system. Legal aid is regarded as central in providing access to justice by ensuring equality before the law, the right ...

be provided to defendants in serious criminal trials

*''

Mabo v Queensland (No 2)

''Mabo v Queensland (No 2)'' (commonly known as the ''Mabo case'' or simply ''Mabo''; ) is a landmark decision of the High Court of Australia that recognised the existence of Native Title in Australia.. It was brought by Eddie Mabo and othe ...

''

[In which it was found that ]native title

Aboriginal title is a common law doctrine that the land rights of indigenous peoples to customary tenure persist after the assumption of sovereignty to that land by another colonising state. The requirements of proof for the recognition of ab ...

was recognized by Australia's common law

*''

Polyukhovich v Commonwealth

''Polyukhovich v Commonwealth'' (1991) 172 CLR 501; 991HCA 32, commonly referred to as the ''War Crimes Act Case'', was a significant case decided in the High Court of Australia regarding the scope of the external affairs power in section 51( ...

''

[regarding the validity of the ''War Crimes Act 1945'']

*''

Sykes v Cleary

''Sykes v Cleary''.The Case Stated (by Dawson J), and then the individual judgments, are separately paragraph-numbered. was a significant decision of the High Court of Australia sitting as the Court of Disputed Returns on 25 November 1992. The ...

''

[regarding the disputed election of ]Phil Cleary

Philip Ronald Cleary (born 8 December 1952) is an Australian political and sport commentator. He is a former Australian rules footballer who played 205 games at the Coburg Football Club, before serving as the member for Division of Wills, Wills ...

*''

Waltons Stores v Maher''

This era is also notable for originating Australia's

implied freedom of political communication

Within Australian law, there is no freedom of speech. Instead, the Australian Constitution implies a freedom of political communication through an interpretation of Sections 7 and 24 of the Constitution.

Background

History

Related High Cou ...

jurisprudence; through the cases ''

Australian Capital Television Pty Ltd v Commonwealth

''Australian Capital Television v Commonwealth'',. is a decision of the High Court of Australia.

The case is notable in Australian Constitutional Law as one of the first cases within Australia's implied freedom of political communication jur ...

'' and

''Theophanous''.

Brennan court: 1995–1998

Gerard Brennan

Sir Francis Gerard Brennan (22 May 1928 – 1 June 2022) was an Australian lawyer and jurist who served as the 10th Chief Justice of Australia. As a judge in the High Court of Australia, he wrote the lead judgement on the Mabo decision, which ...

succeeded Mason in 1995.

The court experienced many changes in members and significant cases in this three year period.

Notable decisions of the court include:

*''

Ha v New South Wales''

[In which the court invalidated a ]New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

tobacco licensing scheme, reining in the licensing scheme exception to the prohibition on states levying excise

file:Lincoln Beer Stamp 1871.JPG, upright=1.2, 1871 U.S. Revenue stamp for 1/6 barrel of beer. Brewers would receive the stamp sheets, cut them into individual stamps, cancel them, and paste them over the Bunghole, bung of the beer barrel so when ...

duties, contained in Section 90 of the Constitution

*''

Grollo v Palmer''

[Known for the ]persona designata

The ''persona designata'' doctrine is a doctrine in law, particularly in Canadian and Australian constitutional law which states that, although it is generally impermissible for a federal judge to exercise non-judicial power, it is permissible fo ...

doctrine

*

''Kable v DPP''[Known for establishing the 'Kable Doctrine']

*''

Lange v ABC''

[An important case within Australia's ]implied freedom of political communication

Within Australian law, there is no freedom of speech. Instead, the Australian Constitution implies a freedom of political communication through an interpretation of Sections 7 and 24 of the Constitution.

Background

History

Related High Cou ...

jurisprudence

*The

Wik case[on whether statutory leases extinguish ]native title

Aboriginal title is a common law doctrine that the land rights of indigenous peoples to customary tenure persist after the assumption of sovereignty to that land by another colonising state. The requirements of proof for the recognition of ab ...

rights

Gleeson court: 1998–2008

Murray Gleeson

Anthony Murray Gleeson (born 30 August 1938) is an Australian former judge who served as the 11th Chief Justice of Australia, in office from 1998 to 2008.

Gleeson was born in Wingham, New South Wales, and studied law at the University of Sydn ...

was appointed Chief Justice in 1998. The Gleeson Court has been regarded as a relatively conservative period of the court's history.

Notable decisions of the court include:

*''

Al-Kateb v Godwin

''Al-Kateb v Godwin'' was a decision of the High Court of Australia, which ruled on 6 August 2004 that the indefinite detention of a stateless person was lawful. The case concerned Ahmed Al-Kateb, a Palestinian man born in Kuwait, who moved t ...

''

*''

Egan v Willis''

*

''New South Wales v Commonwealth'' (Workchoices Case)

*''

R v Tang''

*''

Re Wakim; Ex parte McNally

''Re Wakim; Ex parte McNally''. was a significant case decided in the High Court of Australia on 17 June 1999. The case concerned the constitutional validity of cross-vesting of jurisdiction, in particular, the vesting of state companies law ju ...

''

[In which the court struck down legislation vesting state jurisdiction in the Federal Court]

*''

Sue v Hill

''Sue v Hill'' was an Australian court case decided in the High Court of Australia on 23 June 1999. It concerned a dispute over the apparent return of a candidate, Heather Hill, to the Australian Senate in the 1998 federal election. The resul ...

''

*''

Western Australia v Ward

Native title is the set of rights, recognised by Australian law, held by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups or individuals to land that derive from their maintenance of their traditional laws and customs. These Aboriginal title right ...

''

*The

''Yorta Yorta case''

French court: 2008–2017

Robert French

Robert Shenton French (born 1947) is a former judge of the Federal Court of Australia and was Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia from 2008 to 2017. From 2017 to 2024, he was chancellor of the University of Western Australia, of whi ...

was appointed Chief Justice in September 2008.

Notable decisions of the French court include:

*''

Pape v Commissioner of Taxation

''Pape v Federal Commissioner of Taxation'' is an Australian court case concerning the constitutional validity of the ''Tax Bonus for Working Australians Act (No 2) 2009'' (Cth) which sought to give one-off payments of up to $900 to Australian ...

''

[.]

*''

Plaintiff M70''

*''

Williams v Commonwealth

''Williams v Commonwealth of Australia''. (also known as the "School chaplains case") is a landmark judgment of the High Court. The matter related to the power of the Commonwealth executive government to enter into contracts and spend public ...

''

Kiefel court: 2017–2023

Susan Kiefel

Susan Mary Kiefel (; born 1954) is an Australian lawyer and barrister who was the 13th Chief Justice of Australia from 2017 to 2023. She concurrently served on the High Court of Australia from 2007 to 2023, previously being a judge of both the ...

was appointed Chief Justice in January 2017.

Legal scholars have noted a shift in judicial style within the Kiefel court to one that attempts broad consensus.

The frequency of dissenting judgements has decreased; and there have been relatively fewer decisions with a 4:3 split. Extrajudicially, Kiefel has expressed sympathy for judicial practices that maximise consensus and minimise dissent.

Additionally, it has been noted that Kiefel, Keane, and Bell frequently deliver a joint judgement when a unanimous consensus is not reached; often resulting in their decisions being determinative of the majority. This recent practice of the court has been criticised by the scholar

Jeremy Gans

Jeremy Gans is an Australian author and academic. He is currently Professor of Law at Melbourne Law School.

His expertise is in the criminal justice system, and has particular expertise on the law of evidence, the jury system, human rights, as w ...

, with comparisons drawn to the

Four Horsemen era of the US Supreme Court.

Notable decisions of the Kiefel court include:

*''

Re Canavan

''Re Canavan; Re Ludlam; Re Waters; Re Roberts o 2 Re Joyce; Re Nash; Re Xenophon'' (commonly referred to as the "Citizenship Seven case") is a set of cases, heard together by the High Court of Australia sitting as the Court of Disputed Retur ...

''

[See: ]2017–18 Australian parliamentary eligibility crisis

Starting in July 2017, the eligibility of several members of the Parliament of Australia was questioned. Referred to by some as a "constitutional crisis", fifteen sitting politicians were ruled ineligible by the High Court of Australia (sittin ...

''

[. ]''

*''

Wilkie v Commonwealth''

[In which the Court held that expenditure for the ]Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey

The Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey was a national survey by the Australian Government designed to gauge support for legalising same-sex marriage in Australia. The survey was held via the Australia Post, postal service between 12 Septe ...

had been approved by Parliament and was the collection of "statistical information" that could be conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) is an List of Australian Government entities, Australian Government agency that collects and analyses statistics on economic, population, Natural environment, environmental, and social issues to advi ...

.[. ]

*

''AB v CD; EF v CD''[Release of this decision revealed the 'Lawyer X' scandal and the use of the criminal barrister ]Nicola Gobbo

Nicola Maree Gobbo, sometimes known as Nikki Gobbo, (born 16 November 1972) is an Australian former criminal defence barrister and police informant.

Drug charge at law school

In 1993, while she was a law student, police raided a house owned b ...

as a secret informant by the Victorian Police to the Australian public which lead to a Royal Commission

*

''Pell v The Queen'''

*''

Love v Commonwealth

''Love v Commonwealth; Thoms v Commonwealth'' is a decision of the High Court of Australia. It is an important case in Australian constitutional law, deciding that Aboriginal Australians are not " aliens" for the purposes of section 51(xix) of ...

''

[In which the court decided that ]Aboriginal Australians

Aboriginal Australians are the various indigenous peoples of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland and many of its islands, excluding the ethnically distinct people of the Torres Strait Islands.

Humans first migrated to Australia (co ...

and Torres Strait Islander

Torres Strait Islanders ( ) are the Indigenous Melanesians, Melanesian people of the Torres Strait Islands, which are part of the state of Queensland, Australia. Ethnically distinct from the Aboriginal Australians, Aboriginal peoples of the res ...

s could not be considered "alien" to Australia, and so the Commonwealth Government's power to deport "aliens" under Constitution section 51(xix) did not apply to them.

*''

Palmer v Western Australia''

* ''

Vanderstock v Victoria''

Gageler court: November 2023 – Present

Stephen Gageler

Stephen John Gageler (; born 5 July 1958) is an Australian judge and former barrister. He has been a Justice of the High Court of Australia since 2012 and was appointed Chief Justice of Australia in 2023. He previously served as Solicitor-Gene ...

was appointed Chief Justice in November 2023.

Notable decisions of the Gageler court include:

* ''

NZYQ v Minister for Immigration

''NZYQ v Minister for Immigration'' is a 2023 decision of the High Court of Australia. It is a landmark case in Australian constitutional law, concerning the separation of powers under the Australian Constitution. It was the first judgment of th ...

''

Appointment process, composition, and working conditions

Appointment and tenure

High Court Justices are appointed by the

Governor-General in Council