Herbert Marcuse on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Herbert Marcuse ( ; ; July 19, 1898 – July 29, 1979) was a German–American

Marcuse began his teaching career as a political theorist at

Marcuse began his teaching career as a political theorist at

The Great Refusal: Herbert Marcuse and Contemporary Social Movements

'. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2017. * Kurt H. Wolff and Barrington Moore, Jr., eds (1967), ''The Critical Spirit. Essays in Honor of Herbert Marcuse''. Beacon Press, Boston. * J. Michael Tilley (2011). "Herbert Marcuse: Social Critique, Haecker and Kierkegaardian Individualism" in ''Kierkegaard's Influence on Social-Political Thought'' edited by Jon Stewart.

Comprehensive 'Official' Herbert Marcuse Website

by one of Marcuse's grandsons, with full bibliographies of primary and secondary works, and full texts of many important works

International Herbert Marcuse Society website

at the

Herbert Marcuse Archive

by Herbert Marcuse Association * A. Buick, from worldsocialism.org

(detailed biography and essays, by Douglas Kellner). * Douglas Kellner

"Herbert Marcuse"

*

"Spirit, Capitalism, and Superego"

Ars Industrialis, May 2006. *

"Pentsalaria eta eragina"

'' Jakin'', 35: 3–16. * David Widgery

"Goodbye Comrade M"

(obituary of Marcuse), '' Socialist Review'' (September 1979). * {{DEFAULTSORT:Marcuse, Herbert 1898 births 1979 deaths 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American non-fiction writers 20th-century German philosophers 20th-century German writers American anti-capitalists American anti-fascists American environmentalists American feminists American male non-fiction writers American Marxists American sociologists Anti-consumerists Anti-Stalinist left Brandeis University faculty Burials at the Dorotheenstadt Cemetery Columbia University faculty Communication scholars Critics of work and the work ethic Ecofeminists German anti-capitalists German anti-fascists German environmentalists German feminists German male writers German Marxists German philosophers of technology German socialists German sociologists Harvard University faculty Jewish American social scientists Jewish anti-fascists Jewish emigrants from Nazi Germany to the United States Jewish philosophers Jewish sociologists Left-libertarians Libertarian socialists American male feminists Marxist humanists Marxist theorists New Left People from the Province of Brandenburg People of the Office of Strategic Services People of the United States Office of War Information Revolution theorists University of California, San Diego faculty University of Freiburg alumni Utopian studies scholars Writers from Berlin Humboldt University of Berlin alumni Frankfurt School philosophers

philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, social critic

Social criticism is a form of academic or journalistic criticism focusing on social issues in contemporary society, in respect to perceived injustices and power relations in general.

Social criticism of the Enlightenment

The origin of modern ...

, and political theorist

A political theorist is someone who engages in constructing or evaluating political theory, including political philosophy. Theorists may be academics or independent scholars.

Ancient

* Aristotle

* Chanakya

* Cicero

* Confucius

* Mencius

* ...

, associated with the Frankfurt School

The Frankfurt School is a school of thought in sociology and critical theory. It is associated with the University of Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, Institute for Social Research founded in 1923 at the University of Frankfurt am Main ...

of critical theory

Critical theory is a social, historical, and political school of thought and philosophical perspective which centers on analyzing and challenging systemic power relations in society, arguing that knowledge, truth, and social structures are ...

. Born in Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

, Marcuse studied at Berlin's Friedrich Wilhelm University of Berlin and then at the University of Freiburg

The University of Freiburg (colloquially ), officially the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg (), is a public university, public research university located in Freiburg im Breisgau, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. The university was founded in 1 ...

, where he received his PhD

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, DPhil; or ) is a terminal degree that usually denotes the highest level of academic achievement in a given discipline and is awarded following a course of graduate study and original research. The name of the deg ...

.Lemert, Charles. ''Social Theory: The Multicultural and Classic Readings''. Westview Press, Boulder, CO. 2010. He was a prominent figure in the Frankfurt-based Institute for Social Research, which later became known as the Frankfurt School. In his written works, he criticized capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

, modern technology, Soviet Communism, and popular culture

Popular culture (also called pop culture or mass culture) is generally recognized by members of a society as a set of cultural practice, practices, beliefs, artistic output (also known as popular art

, arguing that they represent new forms of f. pop art

F is the sixth letter of the Latin alphabet.

F may also refer to:

Science and technology Mathematics

* F or f, the number 15 (number), 15 in hexadecimal and higher positional systems

* ''p'F'q'', the hypergeometric function

* F-distributi ...

or mass art, sometimes contraste ...social control

Social control is the regulations, sanctions, mechanisms, and systems that restrict the behaviour of individuals in accordance with social norms and orders. Through both informal and formal means, individuals and groups exercise social con ...

.

Between 1943 and 1950, Marcuse worked in U.S. government service for the Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the first intelligence agency of the United States, formed during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines ...

(predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

) where he criticized the ideology of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in the book '' Soviet Marxism: A Critical Analysis'' (1958). In the 1960s and the 1970s, he became known as the pre-eminent theorist of the New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement that emerged from the counterculture of the 1960s and continued through the 1970s. It consisted of activists in the Western world who, in reaction to the era's liberal establishment, campaigned for freer ...

and the student movements of West Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

, France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, and the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

; some consider him "the Father of the New Left".

His best-known works are '' Eros and Civilization'' (1955) and '' One-Dimensional Man'' (1964). His Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

scholarship inspired many radical intellectuals and political activists in the 1960s and 1970s, both in the United States and internationally.

Biography

Early years

Herbert Marcuse was born July 19, 1898, inBerlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

, to Carl Marcuse and Gertrud Kreslawsky. Marcuse's family was a German upper-middle-class Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

family that was well integrated into German society. Marcuse moved from Berlin to the suburb of Charlottenburg

Charlottenburg () is a Boroughs and localities of Berlin, locality of Berlin within the borough of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf. Established as a German town law, town in 1705 and named after Sophia Charlotte of Hanover, Queen consort of Kingdom ...

, the center of West Berlin. Marcuse's formal education began at Mommsen Gymnasium and continued at the Kaiserin-Augusta Gymnasium in Charlottenburg from 1911 to 1916. In 1916, he was drafted into the German Army

The German Army (, 'army') is the land component of the armed forces of Federal Republic of Germany, Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German together with the German Navy, ''Marine'' (G ...

, but only worked in horse stables in Berlin during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. He spent his entire military service in Germany. While in Berlin, he managed to secure permission to attend lectures at the university of Berlin while still on active duty. He then became a member of a Soldiers' Council that participated in the abortive socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

Spartacist uprising

The Spartacist uprising (German: ), also known as the January uprising () or, more rarely, Bloody Week, was an armed uprising that took place in Berlin from 5 to 12 January 1919. It occurred in connection with the German Revolution of 1918� ...

.

In 1919, he attended the Friedrich Wilhelm University of Berlin, taking classes for four semesters. In 1920, he transferred to the University of Freiburg

The University of Freiburg (colloquially ), officially the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg (), is a public university, public research university located in Freiburg im Breisgau, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. The university was founded in 1 ...

to concentrate on German literature, philosophy, politics, and economics. He completed his Ph.D. thesis at the University of Freiburg in 1922 on the German ''Künstlerroman

A ''Künstlerroman'' (; plural ''-ane''), meaning "artist's novel" in English, is a narrative about an artist's growth to maturity.Werlock, James P. (2010The Facts on File companion to the American short story Volume 2, p.387 It could be classifie ...

'', after which he moved back to Berlin, where he worked in publishing. Two years later, he married Sophie Wertheim, a mathematician.

He returned to Freiburg in 1928 to write a habilitation

Habilitation is the highest university degree, or the procedure by which it is achieved, in Germany, France, Italy, Poland and some other European and non-English-speaking countries. The candidate fulfills a university's set criteria of excelle ...

under Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (; 26 September 1889 – 26 May 1976) was a German philosopher known for contributions to Phenomenology (philosophy), phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. His work covers a range of topics including metaphysics, art ...

, which was published in 1932 as '' Hegel's Ontology and the Theory of Historicity'' (''Hegels Ontologie und die Theorie der Geschichtlichkeit''). This study was written in the context of the Hegel Renaissance that was taking place in Europe with an emphasis on Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political philosophy and t ...

's ontology of life and history, idealist theory of spirit and dialectic.

Institute for Social Research

In 1932, Marcuse stopped working with Heidegger, who joined theNazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

in 1933. Marcuse understood that he would not qualify as a professor under the Nazi regime

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictat ...

. Marcuse was then hired to work for the University of Frankfurt Institute for Social Research. The Institute deposited their endowment in Holland in anticipation of the Nazi takeover, so Marcuse never actually worked in the school there. Instead, he began his work with the Institute in Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

, where a branch office was formed, after leaving Nazi Germany in May 1933. While a member of the Frankfurt School, Marcuse developed a model for critical social theory, created a theory of the new stage of state and monopoly capitalism, described the relationships between philosophy, social theory, and cultural criticism, and provided an analysis and critique of German "National Socialism

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was frequ ...

". Marcuse worked closely with critical theorists while at the Institute.

Emigration to the United States

Marcuse emigrated to the United States in June 1934. He served at the Institute'sColumbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

branch from 1934 through 1942. He traveled to Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, in 1942, to work for the Office of War Information, and afterward the Office of Strategic Services. Marcuse went on to teach at Brandeis University

Brandeis University () is a Private university, private research university in Waltham, Massachusetts, United States. It is located within the Greater Boston area. Founded in 1948 as a nonsectarian, non-sectarian, coeducational university, Bra ...

and the University of California, San Diego

The University of California, San Diego (UC San Diego in communications material, formerly and colloquially UCSD) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in San Diego, California, United States. Es ...

, later in his career. In 1940, he became a US citizen and resided in the country until his death in 1979. Although he never returned to Germany to live, he remained one of the major theorists associated with the Frankfurt School, along with Max Horkheimer

Max Horkheimer ( ; ; 14 February 1895 – 7 July 1973) was a German philosopher and sociologist best known for his role in developing critical theory as director of the Institute for Social Research, commonly associated with the Frankfurt Schoo ...

and Theodor W. Adorno (among others). In 1940, Marcuse published '' Reason and Revolution'', a dialectical work studying G. W. F. Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealism, German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political phi ...

and Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

.

World War II

During World War II, Marcuse first worked for the USOffice of War Information

The United States Office of War Information (OWI) was a United States government agency created during World War II. The OWI operated from June 1942 until September 1945. Through radio broadcasts, newspapers, posters, photographs, films and other ...

(OWI) on anti-Nazi propaganda projects. In 1943, he transferred to the Research and Analysis Branch of the Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the first intelligence agency of the United States, formed during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines ...

(OSS), the precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

.

Directed by the Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher lear ...

historian William L. Langer, the Research and Analysis (R&A) Branch was the largest American research institution in the first half of the twentieth century. At its zenith between 1943 and 1945, it employed over twelve hundred, four hundred of whom were stationed abroad. In many respects, it was the site where post-World War II American social science was born, with protégés of some of the most esteemed American university professors, as well as numerous European intellectual émigrés, in its ranks.

In March 1943, Marcuse joined fellow Frankfurt School scholar Franz Neumann in R&A's Central European Section as senior analyst; there he rapidly established himself as "the leading analyst on Germany".

After the dissolution of the OSS in 1945, Marcuse was employed by the US Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or simply the State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs o ...

as head of the Central European section, becoming an intelligence analyst of Nazism. A compilation of Marcuse's reports was published in '' Secret Reports on Nazi Germany: The Frankfurt School Contribution to the War Effort'' (2013). He retired after the death of his first wife in 1951.

Post-war career

Marcuse began his teaching career as a political theorist at

Marcuse began his teaching career as a political theorist at Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

, then continued at Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

in 1952. Marcuse worked at Brandeis University

Brandeis University () is a Private university, private research university in Waltham, Massachusetts, United States. It is located within the Greater Boston area. Founded in 1948 as a nonsectarian, non-sectarian, coeducational university, Bra ...

from 1954 to 1965, then at the University of California, San Diego

The University of California, San Diego (UC San Diego in communications material, formerly and colloquially UCSD) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in San Diego, California, United States. Es ...

from 1965 to 1970. It was during his time at Brandeis that he wrote his most famous work, '' One-Dimensional Man'' (1964).

Marcuse was a friend and collaborator of the political sociologist Barrington Moore Jr. and of the political philosopher Robert Paul Wolff, and also a friend of the Columbia University sociology professor C. Wright Mills

Charles Wright Mills (August 28, 1916 – March 20, 1962) was an American Sociology, sociologist, and a professor of sociology at Columbia University from 1946 until his death in 1962. Mills published widely in both popular and intellectual jour ...

, one of the founders of the New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement that emerged from the counterculture of the 1960s and continued through the 1970s. It consisted of activists in the Western world who, in reaction to the era's liberal establishment, campaigned for freer ...

movement. In his "Introduction" to ''One-Dimensional Man'', Marcuse wrote: "I should like to emphasize the vital importance of the work of C. Wright Mills."

In the post-war period, Marcuse rejected the theory of class struggle

In political science, the term class conflict, class struggle, or class war refers to the economic antagonism and political tension that exist among social classes because of clashing interests, competition for limited resources, and inequali ...

and the Marxist concern with labor, instead claiming, according to Leszek Kołakowski

Leszek Kołakowski (; ; 23 October 1927 – 17 July 2009) was a Polish philosopher and historian of ideas. He is best known for his critical analysis of Marxism, Marxist thought, as in his three-volume history of Marxist philosophy ''Main Current ...

, that since "all questions of material existence have been solved, moral commands and prohibitions are no longer relevant." He regarded the realization of man's erotic nature as the true liberation of humanity, which inspired the utopias of Jerry Rubin and others.

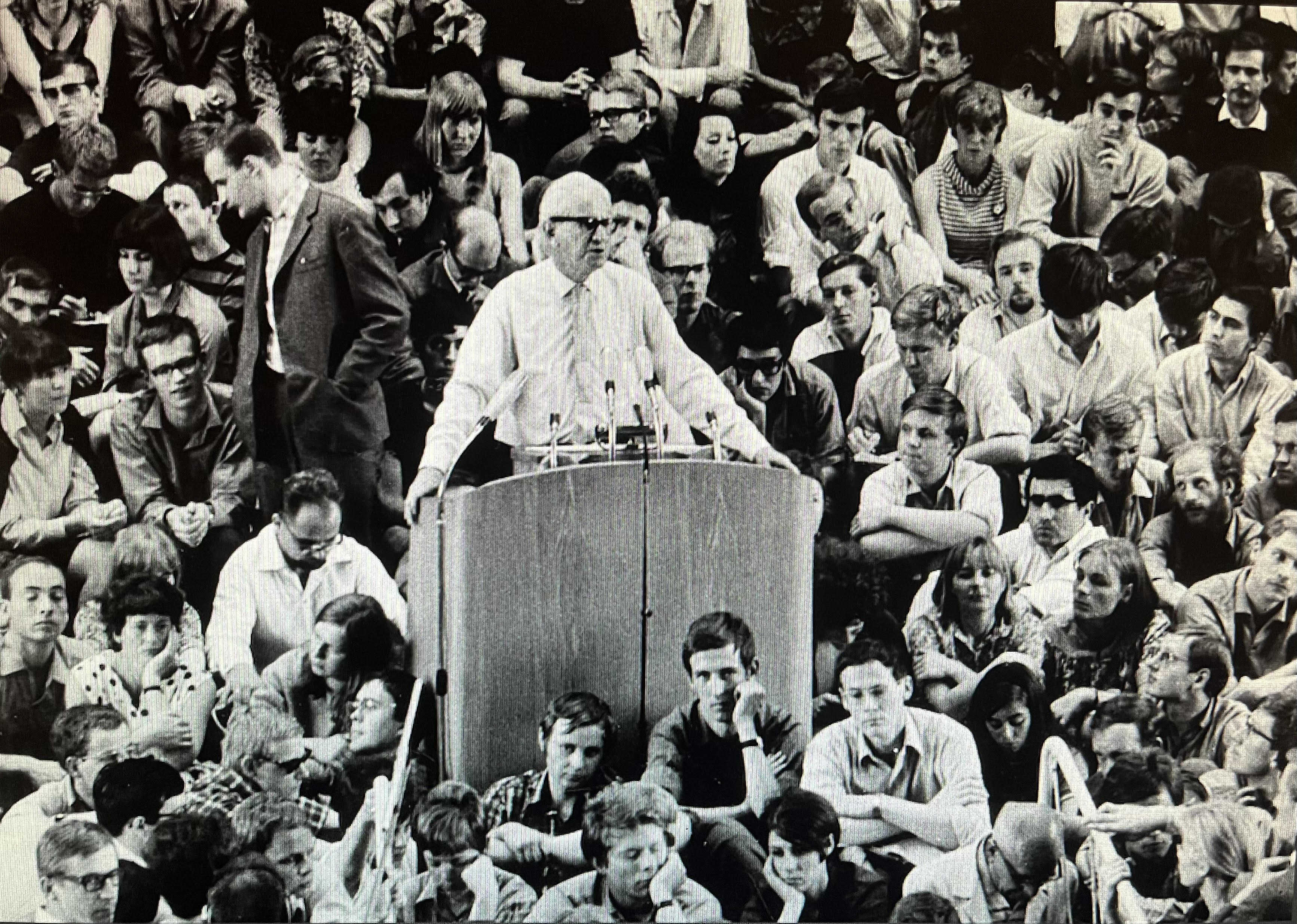

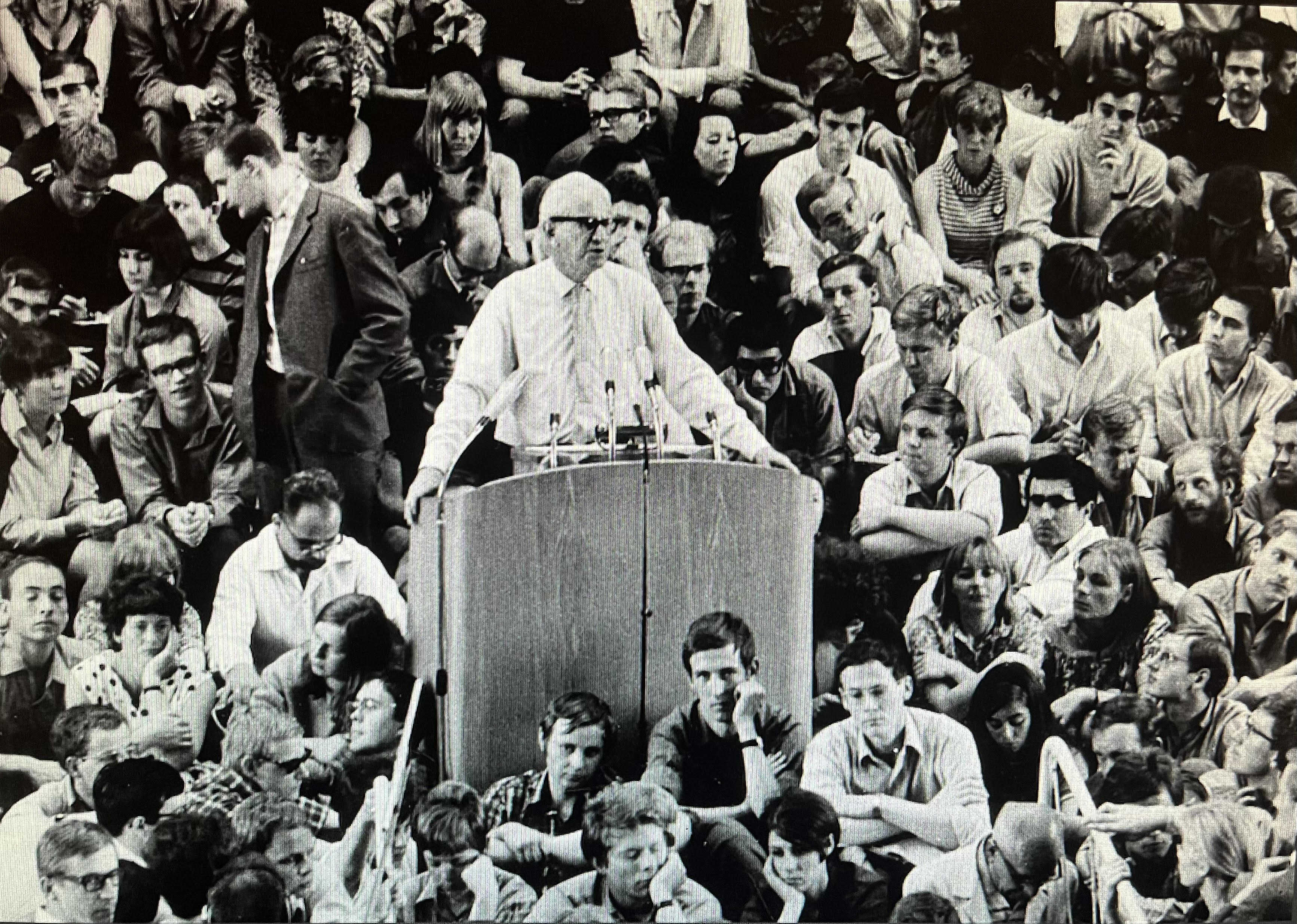

Marcuse's critiques of capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

society (especially his 1955 synthesis of Marx and Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( ; ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies seen as originating fro ...

, '' Eros and Civilization'', and his 1964 book '' One-Dimensional Man'') resonated with the concerns of the student movement in the 1960s because of his willingness to speak at student protests and his essay " Repressive Tolerance" (1965). He had been given the title "Philosopher of the New Left" for his rejection of the traditions of Western civilization. The New Left provided an attractive alternative to American society and Marcuse was able to appeal to many young individuals through his teachings of utopianism. His ideas critiqued contemporary liberalism and its conservative vestiges of nineteenth-century liberalism. Marcuse then soon became known in the media as "Father of the New Left." Contending that the students of the '60s were not waiting for the publication of his work to act, Marcuse brushed the media's branding of him as "Father of the New Left" aside lightly, saying: "It would have been better to call me not the father, but the grandfather, of the New Left." His work strongly influenced intellectual discourse on popular culture

Popular culture (also called pop culture or mass culture) is generally recognized by members of a society as a set of cultural practice, practices, beliefs, artistic output (also known as popular art

and scholarly f. pop art

F is the sixth letter of the Latin alphabet.

F may also refer to:

Science and technology Mathematics

* F or f, the number 15 (number), 15 in hexadecimal and higher positional systems

* ''p'F'q'', the hypergeometric function

* F-distributi ...

or mass art, sometimes contraste ...popular culture studies

Popular culture studies is the study of popular culture from a critical theory perspective combining communication studies and cultural studies

Cultural studies is an academic field that explores the dynamics of contemporary culture (includin ...

. In particular, he influenced youth because he "spoke their language." He understood the importance of rock and roll, for example, as a symbol for New Left activism. He had many speaking engagements in the US and Western Bloc

The Western Bloc, also known as the Capitalist Bloc, the Freedom Bloc, the Free Bloc, and the American Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of countries that were officially allied with the United States during the Cold War (1947–1991). While ...

in the late 1960s and 1970s. He became a close friend and inspirer of the French philosopher André Gorz

Gérard Horst (; , ; 9 February 1923 – 22 September 2007), more commonly known by his pen names André Gorz () and Michel Bosquet (), was an Austrian-French social philosopher and journalist and critic of work. He co-founded '' Le Nouvel Ob ...

.

Marcuse defended the arrested East German dissident Rudolf Bahro (author of ''Die Alternative: Zur Kritik des real existierenden Sozialismus'' rans., ''The Alternative in Eastern Europe'', discussing in a 1979 essay Bahro's theories of "change from within."

Marriages

Marcuse married three times. His first wife wasmathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems. Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, mathematical structure, structure, space, Mathematica ...

Sophie Wertheim (1901–1951), whom he married in 1924 and had his first son Peter with in 1928. Before emigrating to New York in 1934, they resided in Freiburg, Berlin, Geneva, and Paris. They lived in Los Angeles/Santa Monica and Washington, D.C., in the 1930s and 1940s. In 1951, Sophie Wertheim died due to cancer. Marcuse later married Inge Neumann (1914–1973), the widow of his close friend Franz Neumann (1900–1954). After his second wife Inge died in 1973, Marcuse married Erica Sherover (1938–1988), a former graduate student at the University of California, in 1976.

Children

In his first marriage with Sophie Wertheim, they had one son, Peter Marcuse, born in 1928. Peter Marcuse was a professor emeritus ofurban planning

Urban planning (also called city planning in some contexts) is the process of developing and designing land use and the built environment, including air, water, and the infrastructure passing into and out of urban areas, such as transportatio ...

at Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

in New York. Although Marcuse did not have any children with Inge Neumann Marcuse, he helped raise her two sons, Thomas Neumann and Michael Neumann. Thomas (now Osha) is a Berkeley-based writer, activist, lawyer, and muralist. Michael works as a philosophy professor at Trent University

Trent University is a public liberal arts university in Peterborough, Ontario, with a satellite campus in Oshawa, which serves the Regional Municipality of Durham. Founded in 1964, the university is known for its Oxbridge college system, sma ...

in Peterborough, Ontario, Canada.

Marcuse's granddaughter was the novelist Irene Marcuse

Irene Marcuse was an American author of mystery novels. She was a finalist for the Agatha Award in 2000. She died March 8, 2021.

Marcuse held a BA in Literature and Creative Writing and a Master of Social Work from Columbia University. She was ...

and his grandson, Harold Marcuse, is a professor of history at the University of California, Santa Barbara

The University of California, Santa Barbara (UC Santa Barbara or UCSB) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Santa Barbara County, California, United States. Tracing its roots back to 1891 as an ...

.

Death

On July 29, 1979, ten days after his eighty-first birthday, Marcuse died after suffering astroke

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to a part of the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemor ...

during his trip to Germany. He had just finished speaking at the Frankfurt ''Römerberggespräche'', and was on his way to the Max Planck Institute for the Study of the Scientific-Technical World in Starnberg (where he had delivered lectures and participated in discussions from 1974 to 1979) at the invitation of second-generation Frankfurt School theorist Jürgen Habermas

Jürgen Habermas ( , ; ; born 18 June 1929) is a German philosopher and social theorist in the tradition of critical theory and pragmatism. His work addresses communicative rationality and the public sphere.

Associated with the Frankfurt S ...

.

In 2003, after Marcuse's ashes were rediscovered in the United States, they were buried in the Dorotheenstädtischer cemetery in Berlin.

Philosophy and views

Marcuse's concept of repressive desublimation, which has become well-known, refers to his argument that postwar mass culture, with its profusion of sexual provocations, serves to reinforce political repression. If people are preoccupied with inauthentic sexual stimulation, their political energy will be "desublimated"; instead of acting constructively to change the world, they remain repressed and uncritical. Marcuse advanced the prewar thinking of critical theory toward a critical account of the "one-dimensional" nature of bourgeois life in Europe and America. His thinking has been seen as an advance of the concerns of earlier liberal critics such as David Riesman. Two aspects of Marcuse's work are of particular importance. First, his use of language more familiar from the critique of Soviet or Nazi regimes to characterize developments in the advanced industrial world. Second, his grounding of critical theory in a particular use of psychoanalytic thought.Marcuse's early Heideggerian Marxism

During his years in Freiburg, Marcuse wrote a series of essays that explored the possibility of synthesizing Marxism and Heidegger's fundamental ontology, as begun in the latter's work ''Being and Time'' (1927). This early interest in Heidegger followed Marcuse's demand for " concrete philosophy," which, he declared in 1928, "concerns itself with the truth of contemporaneous human existence." These words were directed against theneo-Kantianism

In late modern philosophy, neo-Kantianism () was a revival of the 18th-century philosophy of Immanuel Kant. The neo-Kantians sought to develop and clarify Kant's theories, particularly his concept of the thing-in-itself and his moral philosophy ...

of the mainstream, and against both the revisionist and orthodox Marxist alternatives, in which the subjectivity of the individual played little role. Though Marcuse quickly distanced himself from Heidegger following Heidegger's endorsement of Nazism, thinkers such as Jürgen Habermas

Jürgen Habermas ( , ; ; born 18 June 1929) is a German philosopher and social theorist in the tradition of critical theory and pragmatism. His work addresses communicative rationality and the public sphere.

Associated with the Frankfurt S ...

have suggested that an understanding of Marcuse's later thinking demands an appreciation of his early Heideggerian influence.

Marcuse and capitalism

Marcuse's analysis of capitalism derives partially from one of Karl Marx's main concepts: Objectification, which under capitalism becomes Alienation. Marx believed that capitalism was exploiting humans; that by producing objects of a certain character, laborers became alienated, and this ultimately dehumanized them into functional objects themselves. Marcuse took this belief and expanded it. He argued that capitalism and industrialization pushed laborers so hard that they began to see themselves as extensions of the objects they were producing. At the beginning of ''One-Dimensional Man'' Marcuse writes, "The people recognize themselves in their commodities; they find their soul in their automobile, hi-fi set, split-level home, kitchen equipment," meaning that under capitalism (in consumer society), humans become extensions of the commodities that they buy, thus making commodities extensions of people's minds and bodies. Affluent mass technological societies, he argues, are controlled and manipulated. In societies based upon mass production and mass distribution, the individual worker has become merely a consumer of its commodities and entire commodified way of life. Modern capitalism has created false needs and false consciousness geared to the consumption ofcommodities

In economics, a commodity is an economic good, usually a resource, that specifically has full or substantial fungibility: that is, the market treats instances of the good as equivalent or nearly so with no regard to who produced them.

Th ...

: it locks one-dimensional man into the one-dimensional society which produced the need for people to recognize themselves in their commodities.

The very mechanism that ties the individual to his society has changed, and social control is anchored in the new needs that it has produced. Most important of all, the pressure of consumerism has led to the total integration of the working class into the capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

system. Its political parties and trade unions have become thoroughly bureaucratized and the power of negative thinking or critical reflection has rapidly declined. The working class is no longer a potentially subversive force capable of bringing about revolutionary change.

Marcuse evolved a theory over the years that stated modern technology is repressive naturally. He believed that in both capitalist and communist societies, workers did not question the manner in which they lived due to the mechanism of repression of technological advances. The use of technology allowed people to not be aware of what is occurring around them such as the fact that they might soon be out of their jobs because these technologies are carrying out their same jobs quicker and cheaper. He claimed the modern-day workers were not as rebellious as before during the Karl Marx era (19th century). They just freely conformed to the system they were under for the sake of satisfying their needs and survival. Since they had conformed, the people's revolution that Marcuse felt was necessary never happened.

As a result, rather than looking to the workers as the revolutionary vanguard, Marcuse put his faith in an alliance between radical intellectuals and those groups not yet integrated into one-dimensional society: the socially marginalized, the substratum of the outcasts and outsiders, the exploited and persecuted of other ethnicities and other colors, the unemployed and the unemployable. These were the people whose standards of living demanded the ending of intolerable conditions and institutions and whose resistance to one-dimensional society would not be diverted by the system. Their opposition was revolutionary even if their consciousness was not.

The New Left and radical politics

Many radical scholars and activists were influenced by Marcuse, such as Norman O. Brown,Angela Davis

Angela Yvonne Davis (born January 26, 1944) is an American Marxist and feminist political activist, philosopher, academic, and author. She is Distinguished Professor Emerita of Feminist Studies and History of Consciousness at the University of ...

, Charles J. Moore, Abbie Hoffman

Abbot Howard Hoffman (November 30, 1936 – April 12, 1989) was an American political and social activist who co-founded the Youth International Party ("Yippies") and was a member of the Chicago Seven. He was also a leading proponent of the ...

, Rudi Dutschke

Alfred Willi Rudolf Dutschke (; 7 March 1940 – 24 December 1979) was a German sociologist and political activist who, until severely injured by an assassin in 1968, was a leading charismatic figure within the Socialist Students Union (SDS) in ...

, and Robert M. Young (see the List of Scholars and Activists link below). Among those who critiqued him from the left were Marxist-humanist Raya Dunayevskaya, fellow German emigre Paul Mattick, both of whom subjected ''One-Dimensional Man'' to a Marxist critique, and Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American professor and public intellectual known for his work in linguistics, political activism, and social criticism. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is also a ...

, who knew and liked Marcuse "but thought very little of his work." Marcuse's 1965 essay " Repressive Tolerance", in which he claimed capitalist democracies

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

can have totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely controls the public sph ...

aspects, has been criticized by conservatives. Marcuse argues that genuine tolerance does not permit support for "repression", since doing so ensures that marginalized voices will remain unheard. He characterizes tolerance of repressive speech as "inauthentic". Instead, he advocates a form of tolerance that is intolerant of repressive (namely right-wing) political movements:

Marcuse later expressed his radical ideas through three pieces of writing. He wrote '' An Essay on Liberation'' in 1969, in which he celebrated liberation movements such as those in Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

, which inspired many radicals. In 1972 he wrote '' Counterrevolution and Revolt'', which argues that the hopes of the 1960s were facing a counterrevolution from the right.

After Brandeis denied the renewal of his teaching contract in 1965, Marcuse taught at the University of California, San Diego

The University of California, San Diego (UC San Diego in communications material, formerly and colloquially UCSD) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in San Diego, California, United States. Es ...

. In 1968, California Governor Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

and other conservatives objected to his reappointment, but the university decided to let his contract run until 1970. He devoted the rest of his life to teaching, writing and giving lectures around the world. His efforts brought him attention from the media, which claimed that he openly advocated violence, although he often clarified that only "violence of defense" could be appropriate, not "violence of aggression". He continued to promote Marxian theory, with some of his students helping to spread his ideas. He published his final work '' The Aesthetic Dimension'' in 1977 on the role of art in the process of what he termed "emancipation" from bourgeois society.

Marcuse and feminism

Marcuse felt that societal reform may be found among the outcast of society, thus he supported movements such as the Feminist movement. Marcuse was particularly concerned with Feminism near the end of his life, for reasons he explained in a public lecture ''Marxism and Feminism'' in 1974, mentioning this in a Stanford lecture, "I believe the Women's Liberation Movement is perhaps the most important and potentially the most radical political movement that we have – even if the consciousness of this fact has not yet penetrated the Movement as a whole". Many themes and ambitions from Marcuse's work found embodiment in socialist feminism, especially ideas developed in ''Eros and Civilization''. It involved changes not only in the structural power relations of society, but in the instinctual drives of individual human beings. Although he regarded women's participation in the labor force as positive, and a necessary condition for women's liberation, Marcuse did not consider it sufficient for true freedom. He hoped for a shift in moral values away from aggressive and masculine qualities towards feminine ones. Jessica Benjamin and Nancy Chodorow believed that Marcuse's reliance on Freud'sdrive theory

In psychology, a drive theory, theory of drives or drive doctrine is a theory that attempts to analyze, classify or define the psychological drives. A drive is an instinctual need that has the power of influencing the behavior of an individual; ...

as the source of the desire for societal change is inadequate for both philosophers since he fails to account for the individual's intersubjective growth.

Criticism

Leszek Kołakowski

Leszek Kołakowski (; ; 23 October 1927 – 17 July 2009) was a Polish philosopher and historian of ideas. He is best known for his critical analysis of Marxism, Marxist thought, as in his three-volume history of Marxist philosophy ''Main Current ...

described Marcuse's views as essentially anti-Marxist, in that they ignored Marx's critique of Hegel and discarded the historical theory of class struggle

In political science, the term class conflict, class struggle, or class war refers to the economic antagonism and political tension that exist among social classes because of clashing interests, competition for limited resources, and inequali ...

entirely in favor of an inverted Freudian reading of human history where all social rules could and should be discarded to create a "New World of Happiness." Kołakowski concluded that Marcuse's ideal society "is to be ruled despotically by an enlightened group hohave realized in themselves the unity of ''Logos'' and Eros, and thrown off the vexatious authority of logic, mathematics, and the empirical sciences."

The philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre

Alasdair Chalmers MacIntyre (12 January 1929 – 21 May 2025) was a Scottish-American philosopher who contributed to moral and political philosophy as well as history of philosophy and theology. MacIntyre's '' After Virtue'' (1981) is one of ...

asserted that Marcuse falsely assumed consumers were completely passive, uncritically responding to corporate advertising. MacIntyre frankly opposed Marcuse. "It will be my crucial contention in this book," MacIntyre stated, "that almost all of Marcuse's key positions are false. For example, Marcuse was not an orthodox Marxist. Like many of the Frankfurt School, Marcuse wrote of "critical theory

Critical theory is a social, historical, and political school of thought and philosophical perspective which centers on analyzing and challenging systemic power relations in society, arguing that knowledge, truth, and social structures are ...

" not of "Marxism" and MacIntyre notes a similarity in this to the Right Hegelians, whom Marx attacked. Hence, MacIntyre proposed that Marcuse be regarded as "a pre-Marxist thinker". According to MacIntyre, Marcuse's assumptions about advanced industrial society

In sociology, an industrial society is a society driven by the use of technology and machinery to enable mass production, supporting a large population with a high capacity for division of labour. Such a structure developed in the Western world ...

were wrong in whole and in part. "Marcuse," concluded MacIntyre, "invokes the great names of freedom and reason while betraying their substance at every important point."

Legacy

Herbert Marcuse appealed to students of the New Left through his emphasis on the power of critical thought and his vision of total human emancipation and a non-repressive civilization. He supported students he felt were subject to the pressures of a commodifying system, and has been regarded as an inspirational intellectual leader. He is also considered among the most influential of the Frankfurt School critical theorists on American culture, due to his studies on student and counter-cultural movements on the 1960s. The legacy of the 1960s, of which Marcuse was a vital part, lives on, and the great refusal is still practiced by oppositional groups and individuals. ''Eros and Civilization'' is one of Marcuse's most notable works, and his insensitivity to human relatedness portrayed in this project is considered the key failure of this work. His insights of psychoanalytic object relations theory in this project have not been wedded or reinterpreted, without abandoning its core principles. Marcuse's thought remains influential in the 21st century. In the introduction to an issue of the journal ''New Political Science'' dedicated to Marcuse, Robert Kirsch and Sarah Surak described his influence as "alive and well, vibrant across multiple fields of inquiry across many areas of social relations". Marcuse's concept of repressive tolerance attracted renewed attention following the 9/11 attacks. Repressive tolerance is also relevant to 21st-century campus protests and theBlack Lives Matter

Black Lives Matter (BLM) is a Decentralization, decentralized political and social movement that aims to highlight racism, discrimination and Racial inequality in the United States, racial inequality experienced by black people, and to pro ...

movement.

Marcuse is not widely remembered outside of contexts where critical theory is taught or referenced. This theory, rooted in Marxist philosophy, remains as one of the main components of Marcuse's influence.

Bibliography

Books * ''Hegel's Ontology and the Theory of Historicity'' (1932), originally written in German, in English 1987. * ''Studie über Autorität und Familie'' (1936) in German, republished 1987, 2005. Marcuse wrote just over 100 pages in this 900-page study. * '' Reason and Revolution: Hegel and the Rise of Social Theory'' (1941) * '' Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud'' (1955) * '' Soviet Marxism: A Critical Analysis'' (1958) * '' One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society'' (1964) * '' A Critique of Pure Tolerance'' (1965) Essay "Repressive Tolerance," with additional essays by Robert Paul Wolff and Barrington Moore Jr. * ''Negations: Essays in Critical Theory'' (1968) * '' An Essay on Liberation'' (1969) * ''Five Lectures'' (1969) * '' Counterrevolution and Revolt'' (1972) * '' The Aesthetic Dimension: Toward a Critique of Marxist Aesthetics'' (1978) Essays * "Neue Quellen zur Grundlegung des Historischen Materialismus" (1932) * "Repressive Tolerance" (1965) * "Liberation" (1969) * "On the Problem of the Dialectic" (1976) * "Protosocialism and Late Capitalism: Toward a Theoretical Synthesis Based on Bahro's Analysis" (1980)See also

* '' Men of Ideas''References

Further reading

Herbert Marcuse

* John Abromeit and W. Mark Cobb, eds (2004), ''Herbert Marcuse: A Critical Reader'', New York, London: Routledge. * Andrew Feenberg and William Leiss (2007), ''The Essential Marcuse: Selected Writings of Philosopher and Social Critic Herbert Marcuse'', Boston: Beacon Press. * ''Technology, War and Fascism: Collected Papers of Herbert Marcuse, volume 1'' (London: Routledge 1998)Criticism and analysis

* C. Fred Alford (1985), ''Science and Revenge of Nature: Marcuse and Habermas'', Gainesville: University of Florida Press. * Harold Bleich (1977), ''The Philosophy of Herbert Marcuse'', Washington: University Press of America. * Paul Breines (1970), ''Critical Interruptions: New Left Perspectives on Herbert Marcuse'', New York: Herder and Herder. * Douglas Kellner (1984), ''Herbert Marcuse and the Crisis of Marxism''. London: Macmillan. . * Paul Mattick (1972), ''Critique of Marcuse: One-dimensional Man in Class Society'' Merlin Press * Alain Martineau (1986). ''Herbert Marcuse's Utopia,'' Harvest House, Montreal. * . * . * Eliseo Vivas (1971), ''Contra Marcuse'', Arlington House, New Rochelle. * Andrew T. Lamas, Todd Wolfson, and Peter N. Funke, eds (2017),The Great Refusal: Herbert Marcuse and Contemporary Social Movements

'. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2017. * Kurt H. Wolff and Barrington Moore, Jr., eds (1967), ''The Critical Spirit. Essays in Honor of Herbert Marcuse''. Beacon Press, Boston. * J. Michael Tilley (2011). "Herbert Marcuse: Social Critique, Haecker and Kierkegaardian Individualism" in ''Kierkegaard's Influence on Social-Political Thought'' edited by Jon Stewart.

General

* Anthony Elliott and Larry Ray (2003), ''Key Contemporary Social Theorists''. * Charles Lemert (2010), ''Social Theory: The Multicultural and Classic Readings''. * Douglas Mann (2008), ''A Survey of Modern Social Theory''. * Noel Parker and Stuart Sim (1997), ''A–Z Guide to Modern Social and Political Theorist''. * "Herbert Marcuse , American philosopher". ''Encyclopedia Britannica''. Retrieved 2021-10-23.External links

*Comprehensive 'Official' Herbert Marcuse Website

by one of Marcuse's grandsons, with full bibliographies of primary and secondary works, and full texts of many important works

International Herbert Marcuse Society website

at the

Marxists Internet Archive

Marxists Internet Archive, also known as MIA or Marxists.org, is a non-profit online encyclopedia that hosts a multilingual library (created in 1990) of the works of communist, anarchist, and socialist writers, such as Karl Marx, Friedrich Enge ...

Herbert Marcuse Archive

by Herbert Marcuse Association * A. Buick, from worldsocialism.org

(detailed biography and essays, by Douglas Kellner). * Douglas Kellner

"Herbert Marcuse"

*

Bernard Stiegler

Bernard Stiegler (; 1 April 1952 – 5 August 2020) was a French philosopher. He was head of the Institut de recherche et d'innovation (IRI), which he founded in 2006 at the Centre Georges-Pompidou. He was also founder of the political and c ...

"Spirit, Capitalism, and Superego"

Ars Industrialis, May 2006. *

Joxe Azurmendi

Joxe Azurmendi Otaegi (born 19 March 1941) is a Basque people, Basque writer, philosopher, essayist, and poet. He has published numerous articles and books on ethics, politics, the philosophy of language, Technology, technique, Basque literatur ...

1969"Pentsalaria eta eragina"

'' Jakin'', 35: 3–16. * David Widgery

"Goodbye Comrade M"

(obituary of Marcuse), '' Socialist Review'' (September 1979). * {{DEFAULTSORT:Marcuse, Herbert 1898 births 1979 deaths 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American non-fiction writers 20th-century German philosophers 20th-century German writers American anti-capitalists American anti-fascists American environmentalists American feminists American male non-fiction writers American Marxists American sociologists Anti-consumerists Anti-Stalinist left Brandeis University faculty Burials at the Dorotheenstadt Cemetery Columbia University faculty Communication scholars Critics of work and the work ethic Ecofeminists German anti-capitalists German anti-fascists German environmentalists German feminists German male writers German Marxists German philosophers of technology German socialists German sociologists Harvard University faculty Jewish American social scientists Jewish anti-fascists Jewish emigrants from Nazi Germany to the United States Jewish philosophers Jewish sociologists Left-libertarians Libertarian socialists American male feminists Marxist humanists Marxist theorists New Left People from the Province of Brandenburg People of the Office of Strategic Services People of the United States Office of War Information Revolution theorists University of California, San Diego faculty University of Freiburg alumni Utopian studies scholars Writers from Berlin Humboldt University of Berlin alumni Frankfurt School philosophers