Henry Wilson (architect And Designer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

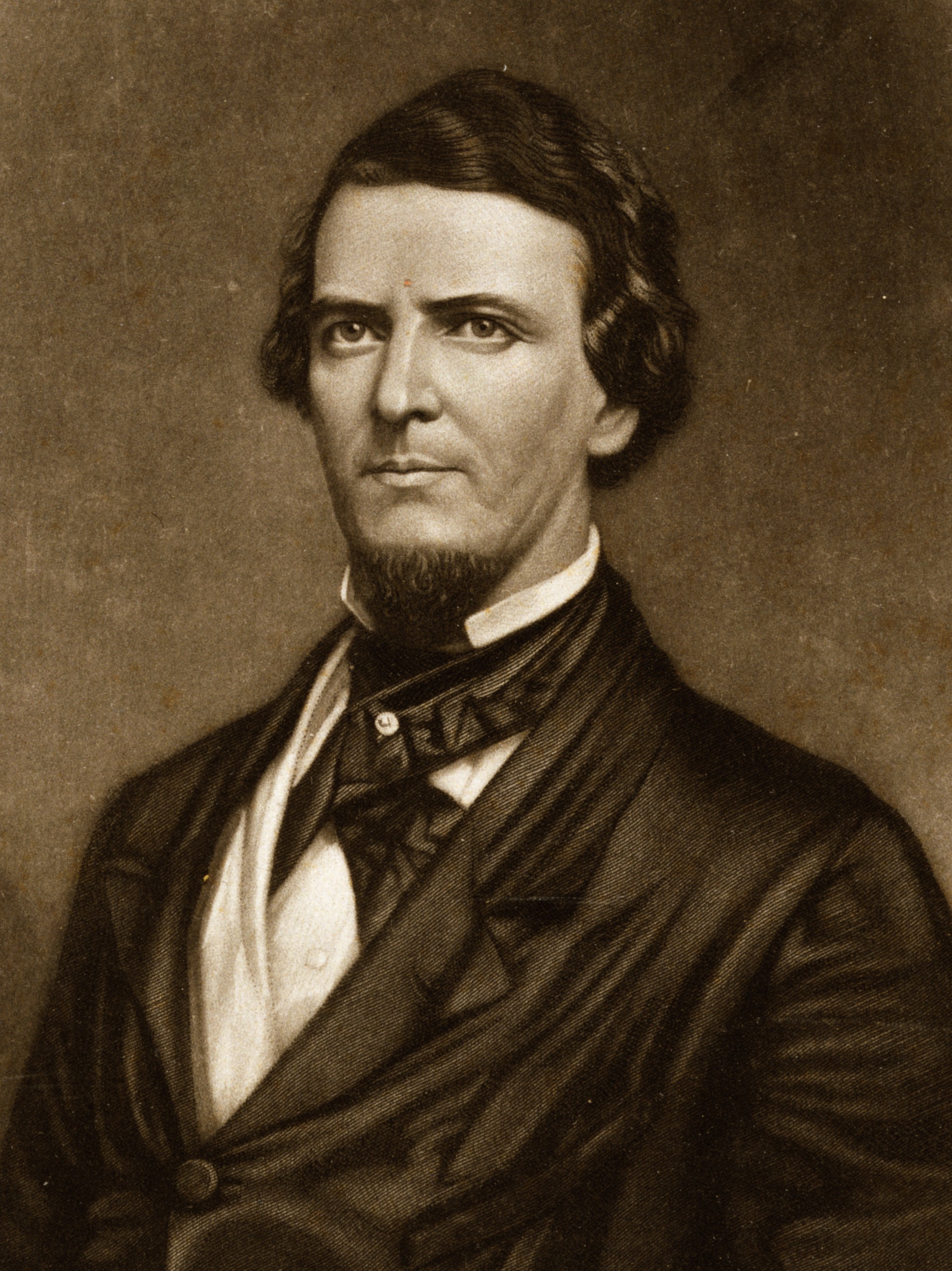

Henry Wilson (born Jeremiah Jones Colbath; February 16, 1812 – November 22, 1875) was the 18th

After trying and failing to find work in New Hampshire, in 1833 Wilson walked more than one hundred miles to

After trying and failing to find work in New Hampshire, in 1833 Wilson walked more than one hundred miles to

On May 22, 1856,

On May 22, 1856,  In June 1858 Wilson made a Senate speech in which he suggested corruption in the government of California and implied complicity on the part of Senator

In June 1858 Wilson made a Senate speech in which he suggested corruption in the government of California and implied complicity on the part of Senator

In the summer of 1861, after the congressional session ended, Wilson returned to Massachusetts and recruited and equipped nearly 2,300 men in forty days. They were mustered in as the

In the summer of 1861, after the congressional session ended, Wilson returned to Massachusetts and recruited and equipped nearly 2,300 men in forty days. They were mustered in as the

On July 8, 1862, Wilson drafted a measure that authorized the President to enlist African Americans who had been held in slavery and were deemed competent for military service, and employ them to construct fortifications and carry out other military-related manual labor, the first step towards allowing African Americans to serve as soldiers. President Lincoln signed the amendment into law on July 17. Wilson's law paid African Americans in the military $10 monthly, which was effectively $7 a month after deductions for food and clothing, while white soldiers were paid effectively $14 monthly.John G. Nicolay and John Hay (2009), ''Life of Abraham Lincoln'' Volume VI, pp. 441–442

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln's

On July 8, 1862, Wilson drafted a measure that authorized the President to enlist African Americans who had been held in slavery and were deemed competent for military service, and employ them to construct fortifications and carry out other military-related manual labor, the first step towards allowing African Americans to serve as soldiers. President Lincoln signed the amendment into law on July 17. Wilson's law paid African Americans in the military $10 monthly, which was effectively $7 a month after deductions for food and clothing, while white soldiers were paid effectively $14 monthly.John G. Nicolay and John Hay (2009), ''Life of Abraham Lincoln'' Volume VI, pp. 441–442

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln's  Wilson supported the right of black men to join the uniformed services. Once African Americans were permitted to serve in the military, Wilson advocated in the Senate for them to receive equal pay and other benefits. A Vermont newspaper portrayed Wilson's position and enhanced his nationwide reputation as an abolitionist by editorializing "Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, in a speech in the U.S. Senate on Friday, said he thought our treatment of the negro soldiers almost as bad as that of the rebels at Fort Pillow. This is hardly an exaggeration."

On June 15, 1864, Wilson succeeded in adding a provision to an appropriations bill which addressed the pay disparity between whites and blacks in the military by authorizing equal salaries and benefits for African American soldiers. Wilson's provision stated that "all persons of color who had been or might be mustered into the military service should receive the same uniform, clothing, rations, medical and hospital attendance, and pay" as white soldiers, to date from January 1864.

Wilson introduced a bill in Congress which would free in the Union's slave-holding states the still-enslaved families of former slaves serving in the Union Army. In advocating for passage, Wilson argued that allowing the family members of soldiers to remain in slavery was a "burning shame to this country ... Let us hasten the enactment ... that, on the forehead of the soldier's wife and the soldier's child, no man can write "Slave". President Lincoln signed the measure into law on March 3, 1865, and an estimated 75,000 African American women and children were freed in Kentucky alone.

Wilson supported the right of black men to join the uniformed services. Once African Americans were permitted to serve in the military, Wilson advocated in the Senate for them to receive equal pay and other benefits. A Vermont newspaper portrayed Wilson's position and enhanced his nationwide reputation as an abolitionist by editorializing "Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, in a speech in the U.S. Senate on Friday, said he thought our treatment of the negro soldiers almost as bad as that of the rebels at Fort Pillow. This is hardly an exaggeration."

On June 15, 1864, Wilson succeeded in adding a provision to an appropriations bill which addressed the pay disparity between whites and blacks in the military by authorizing equal salaries and benefits for African American soldiers. Wilson's provision stated that "all persons of color who had been or might be mustered into the military service should receive the same uniform, clothing, rations, medical and hospital attendance, and pay" as white soldiers, to date from January 1864.

Wilson introduced a bill in Congress which would free in the Union's slave-holding states the still-enslaved families of former slaves serving in the Union Army. In advocating for passage, Wilson argued that allowing the family members of soldiers to remain in slavery was a "burning shame to this country ... Let us hasten the enactment ... that, on the forehead of the soldier's wife and the soldier's child, no man can write "Slave". President Lincoln signed the measure into law on March 3, 1865, and an estimated 75,000 African American women and children were freed in Kentucky alone.

When

When

Wilson actually desired to be vice president. During his speech-making tour of the South, Wilson moderated his tougher Reconstruction ideology, advocating a biracial society, while urging African Americans and their white supporters to take a conciliatory and peaceful approach with Southern whites who had favored the Confederacy. Radicals, including Benjamin Wade, were stunned by Wilson's remarks, believing blacks should not be subject to their former white owners. At the 1868 Republican National Convention, Republican Convention, Wilson, Wade and others competed for the vice presidential nomination, and Wilson had support among Southern delegates, but he failed to win after five ballots. Wade was also unable to win the convention vote, and Wilson's delegates eventually switched their votes to Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax, who won the nomination and went on to win the general election with Grant at the head of the ticket. After Grant and Colfax won the 1868 election Wilson declined to serve as

Wilson actually desired to be vice president. During his speech-making tour of the South, Wilson moderated his tougher Reconstruction ideology, advocating a biracial society, while urging African Americans and their white supporters to take a conciliatory and peaceful approach with Southern whites who had favored the Confederacy. Radicals, including Benjamin Wade, were stunned by Wilson's remarks, believing blacks should not be subject to their former white owners. At the 1868 Republican National Convention, Republican Convention, Wilson, Wade and others competed for the vice presidential nomination, and Wilson had support among Southern delegates, but he failed to win after five ballots. Wade was also unable to win the convention vote, and Wilson's delegates eventually switched their votes to Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax, who won the nomination and went on to win the general election with Grant at the head of the ticket. After Grant and Colfax won the 1868 election Wilson declined to serve as

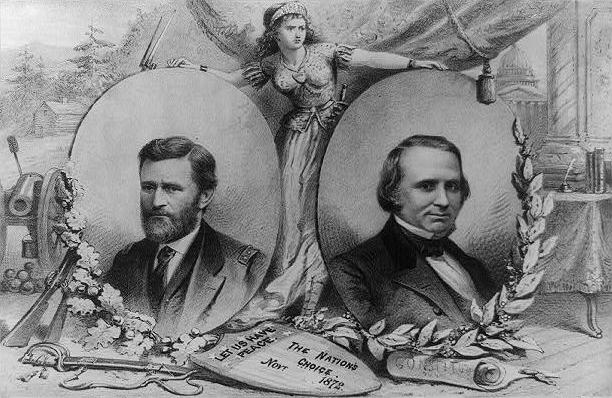

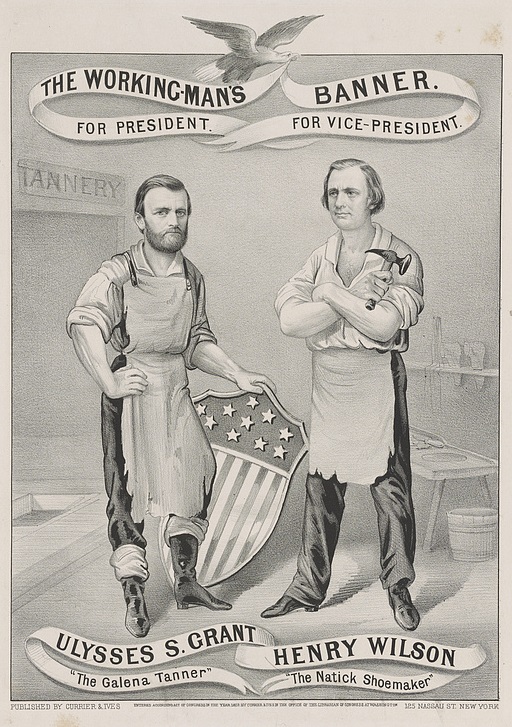

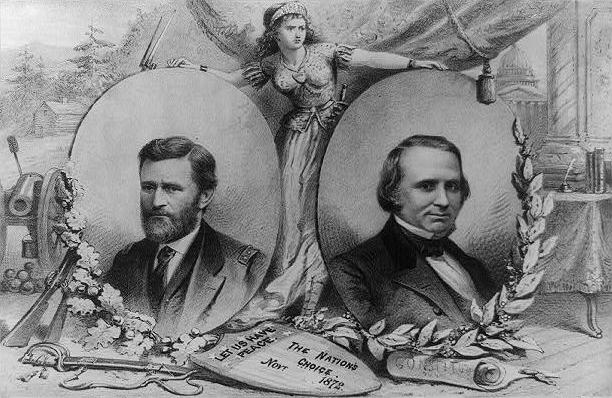

In 1872 Wilson had a strong reputation among Republicans as a principled but practical reformer who supported African American civil rights, voting rights for women, federal education aid, regulation of businesses, and prohibition of liquor. In 1870, incumbent Vice President Schuyler Colfax, said he would not run for another term, creating the possibility of a contested nomination. In addition, some Republicans, including Grant, desired another vice presidential nominee because they believed Colfax had presidential aspirations and might endanger Grant's reelection by bolting to the Liberal Republican Party (United States), Liberal Republican Party, which had formed because of opposition to charges of corruption in the Grant administration and Grant's attempted Proposed annexation of Santo Domingo, Santo Domingo annexation. The Liberal Republican convention, held in Cincinnati in April, and headed by Carl Schurz, desired to replace Grant because of corruption in his administration, end Reconstruction, and return Southern state governments to white rule. They nominated Horace Greeley for president and Benjamin Gratz Brown, B. Gratz Brown for vice president.

In 1872 Wilson had a strong reputation among Republicans as a principled but practical reformer who supported African American civil rights, voting rights for women, federal education aid, regulation of businesses, and prohibition of liquor. In 1870, incumbent Vice President Schuyler Colfax, said he would not run for another term, creating the possibility of a contested nomination. In addition, some Republicans, including Grant, desired another vice presidential nominee because they believed Colfax had presidential aspirations and might endanger Grant's reelection by bolting to the Liberal Republican Party (United States), Liberal Republican Party, which had formed because of opposition to charges of corruption in the Grant administration and Grant's attempted Proposed annexation of Santo Domingo, Santo Domingo annexation. The Liberal Republican convention, held in Cincinnati in April, and headed by Carl Schurz, desired to replace Grant because of corruption in his administration, end Reconstruction, and return Southern state governments to white rule. They nominated Horace Greeley for president and Benjamin Gratz Brown, B. Gratz Brown for vice president.

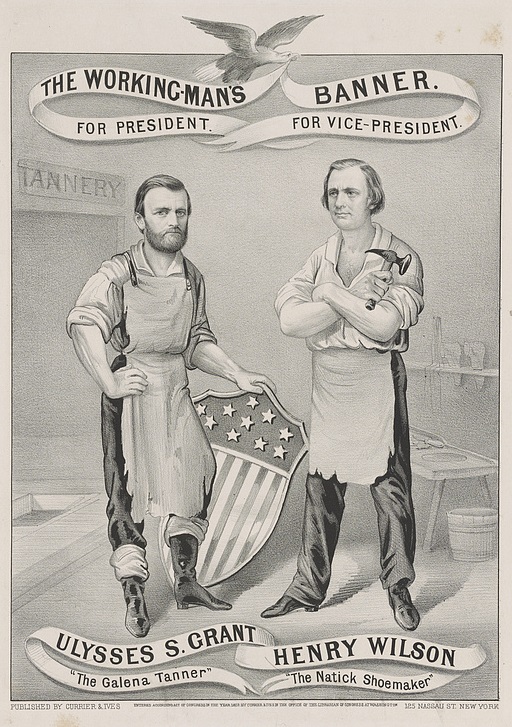

The Republican convention opened on June 5 in Philadelphia and the delegates were in an enthusiastic mood. For the first time in party convention history, telegraph operators communicated minute-by-minute proceedings to the nation. The Republican platform supported amnesty for former Confederates, low tariffs, civil service reform, Grant's Indian Peace policy, and civil rights for African Americans. Grant was unanimously renominated on the second day, to the loud cheers of the convention crowd. Wilson was popular among Republicans for the vice presidential nomination, with an appealing Rags to riches, rags-to-riches story that included his rise from indentured servant to owner and operator of a successful shoe making business. On the first ballot, he defeated Colfax, who by then had become an active candidate by renouncing his 1870 pledge and informing his supporters that he would accept renomination if it was offered. The Republicans believed Wilson's nomination, as a politician of integrity coming from the anti-slavery movement, would outflank the anti-corruption argument of the Liberal Republicans, who counted Sumner among their members. Both Grant and his new running mate Wilson were idealized by Republican posters, which depicted Grant "the Galena Tanning (leather), Tanner" and Wilson "the Natick Shoemaker" carrying tools and wearing workmen's aprons. (Grant's father operated a tanning and leather goods manufacturing business, and before the Civil War Grant had clerked in his father's Galena, Illinois, store.) In July, in an unprecedented political party fusion influenced by Schurz, the Democrats adopted the Liberal Republican platform and endorsed that party's candidates. Grant's personal popularity proved insurmountable in the general election, and Grant and Wilson went on to overwhelmingly defeat Greeley and Brown in both the popular and electoral college votes. Wilson's nomination for Vice President had been intended to strengthen the Republican ticket, and was seen as a success.

The Republican convention opened on June 5 in Philadelphia and the delegates were in an enthusiastic mood. For the first time in party convention history, telegraph operators communicated minute-by-minute proceedings to the nation. The Republican platform supported amnesty for former Confederates, low tariffs, civil service reform, Grant's Indian Peace policy, and civil rights for African Americans. Grant was unanimously renominated on the second day, to the loud cheers of the convention crowd. Wilson was popular among Republicans for the vice presidential nomination, with an appealing Rags to riches, rags-to-riches story that included his rise from indentured servant to owner and operator of a successful shoe making business. On the first ballot, he defeated Colfax, who by then had become an active candidate by renouncing his 1870 pledge and informing his supporters that he would accept renomination if it was offered. The Republicans believed Wilson's nomination, as a politician of integrity coming from the anti-slavery movement, would outflank the anti-corruption argument of the Liberal Republicans, who counted Sumner among their members. Both Grant and his new running mate Wilson were idealized by Republican posters, which depicted Grant "the Galena Tanning (leather), Tanner" and Wilson "the Natick Shoemaker" carrying tools and wearing workmen's aprons. (Grant's father operated a tanning and leather goods manufacturing business, and before the Civil War Grant had clerked in his father's Galena, Illinois, store.) In July, in an unprecedented political party fusion influenced by Schurz, the Democrats adopted the Liberal Republican platform and endorsed that party's candidates. Grant's personal popularity proved insurmountable in the general election, and Grant and Wilson went on to overwhelmingly defeat Greeley and Brown in both the popular and electoral college votes. Wilson's nomination for Vice President had been intended to strengthen the Republican ticket, and was seen as a success.

Wilson remained in occasional ill health into 1874, but was able to attend funeral services for Charles Sumner in March. Throughout his remaining tenure, Wilson's Senate attendance was irregular due to his continued poor health. During periods when he was not ill, Wilson was also able to resume some of his ceremonial duties, including participating in a White House party for the King of Hawaii, Kalākaua, David Kalākaua, in December 1874. When Free Soil and abolitionist colleague Gerrit Smith died in New York City on December 28, 1874, Wilson traveled there to view the body and take part in funeral services.

Wilson continued to go through bouts of ill health in 1875. While working at the

Wilson remained in occasional ill health into 1874, but was able to attend funeral services for Charles Sumner in March. Throughout his remaining tenure, Wilson's Senate attendance was irregular due to his continued poor health. During periods when he was not ill, Wilson was also able to resume some of his ceremonial duties, including participating in a White House party for the King of Hawaii, Kalākaua, David Kalākaua, in December 1874. When Free Soil and abolitionist colleague Gerrit Smith died in New York City on December 28, 1874, Wilson traveled there to view the body and take part in funeral services.

Wilson continued to go through bouts of ill health in 1875. While working at the

"Henry Wilson & The Civil War"

The series had over 22 episodes and was hosted by Lincoln Anniballi.

"The Writing of ''History of the Rise and Fall of the Slave Power in America,''"

''Civil War History,'' June 1985, Vol. 31, Issue 2, pp. 144–162. * * * * * * * * * * * Wilson, Henry (1872–1877). ''History of the Rise and Fall of the Slave Power in America'', 3 vols. (Boston: J. R. Osgood and Co.) * *

''History of the antislavery measures of the Thirty-seventh and Thirty-eighth United-States Congresses, 1861–64''

by Henry Wilson at archive.org

''History of the reconstruction measures of the Thirty-ninth and Fortieth Congresses, 1865–68''

by Henry Wilson at archive.org * ''History of the rise and fall of the slave power in America''

Vol 1Vol 2

an

Vol 3

by Henry Wilson at archive.org * * *

Memorial Addresses on the Life and Character of Henry Wilson, (Vice President of the United States)

'. 1876. U.S. Government Printing Office. *

The Life and Public Services of Henry Wilson, Late Vice President of the United States

'. 1876. Elias Nason and Thomas Russell. *

Tribute to the Memory of Henry Wilson, Late Vice President of the United States

'. 1876. Union League Club of New York. *

Henry Wilson Memorial Park

' *

Henry Wilson's Regiment: History of the Twenty-second Massachusetts Infantry, the Second Company Sharpshooters, and the Third Light Battery in the War of the Rebellion

'. 1887. John L. Parker and Robert G. Carter, authors. Rand Avery Company (Boston, MA), publisher. *

Memorial Addresses on the Life and Character of Henry Wilson

' (1876) Washington: Government Printing Office , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Wilson, Henry Henry Wilson, 1812 births 1875 deaths 19th-century American newspaper editors 19th-century vice presidents of the United States 19th-century American historians 19th-century American male writers 19th-century New Hampshire politicians 1872 United States vice-presidential candidates American abolitionists American Congregationalists American male journalists American male non-fiction writers American militia generals Congregationalist abolitionists Grant administration personnel Historians of the American Civil War American indentured servants Members of the Massachusetts House of Representatives Massachusetts Free Soilers Massachusetts Know Nothings Massachusetts Republicans Massachusetts state senators Massachusetts Whigs People from Farmington, New Hampshire People of Massachusetts in the American Civil War Presidents of the Massachusetts Senate Radical Republicans Republican Party (United States) vice presidential nominees Republican Party United States senators from Massachusetts Republican Party vice presidents of the United States Union army colonels Union (American Civil War) political leaders Vice presidents of the United States American workers' rights activists Writers from Massachusetts 19th-century members of the Massachusetts General Court 19th-century United States senators

vice president of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest ranking office in the Executive branch of the United States government, executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks f ...

, serving from 1873 until his death in 1875, and a senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or Legislative chamber, chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the Ancient Rome, ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior ...

from Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

from 1855 to 1873. Before and during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, he was a leading Republican, and a strong opponent of slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

. Wilson devoted his energies to the destruction of "Slave Power

The Slave Power, or Slavocracy, referred to the perceived political power held by American slaveholders in the federal government of the United States during the Antebellum period. Antislavery campaigners charged that this small group of wealth ...

", the faction of slave owners and their political allies which anti-slavery Americans saw as dominating the country.

Originally a Whig, Wilson was a founder of the Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party, also called the Free Democratic Party or the Free Democracy, was a political party in the United States from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party. The party was focused o ...

in 1848. He served as the party chairman before and during the 1852 presidential election. Wilson worked diligently to build an anti-slavery coalition, which came to include the Free Soil Party, anti-slavery Democrats, New York Barnburners

The Barnburners and Hunkers were the names of two opposing factions of the New York Democratic Party in the mid-19th century. The main issue dividing the two factions was that of slavery, with the Barnburners being the anti-slavery faction. Whil ...

, the Liberty Party, anti-slavery members of the Know Nothing

The American Party, known as the Native American Party before 1855 and colloquially referred to as the Know Nothings, or the Know Nothing Party, was an Old Stock Americans, Old Stock Nativism in United States politics, nativist political movem ...

s, and anti-slavery Whigs (called Conscience Whigs

The Whig Party was a mid-19th century political party in the United States. Alongside the Democratic Party, it was one of two major parties from the late 1830s until the early 1850s and part of the Second Party System. As well as four Whig p ...

). When the Free Soil party dissolved in the mid-1850s, Wilson joined the Republican Party, which he helped found, and which was organized largely in line with the anti-slavery coalition he had nurtured in the 1840s and 1850s.

While a senator during the Civil War, Wilson was considered a "Radical Republican

The Radical Republicans were a political faction within the Republican Party originating from the party's founding in 1854—some six years before the Civil War—until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reconstruction. They ca ...

", and his experience as a militia general, organizer and commander of a Union Army regiment, and chairman of the Senate military committees enabled him to assist the Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

administration in the organization and oversight of the Union Army and Union Navy. Wilson successfully authored bills that outlawed slavery in Washington, D.C., and incorporated African Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa ...

in the Union Civil War effort in 1862.

After the Civil War, he supported the Radical Republican program for Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

. In 1872, Wilson was elected vice president as the running mate of Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

, the incumbent president of the United States, who was running for a second term. The Grant and Wilson ticket was successful, and Wilson served as vice president from March 4, 1873, until his death on November 22, 1875. Wilson's effectiveness as vice president was limited after he suffered a debilitating stroke in May 1873, and his health continued to decline until he was the victim of a fatal stroke while working in the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called the Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the Seat of government, seat of the United States Congress, the United States Congress, legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, federal g ...

in late 1875.

Throughout his career, Wilson was known for championing causes that were unpopular, including workers' rights

Labor rights or workers' rights are both legal rights and human rights relating to labor relations between workers and employers. These rights are codified in national and international labor and employment law. In general, ...

for both blacks and whites and the abolition of slavery. Massachusetts politician George Frisbie Hoar

George Frisbie Hoar (August 29, 1826 – September 30, 1904) was an American attorney and politician, represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1877 until his death in 1904. He belonged to an extended family that became politic ...

, who served in the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

while Wilson was a senator and later served in the Senate himself, believed Wilson to be the most skilled political organizer in the country. However, Wilson's reputation for personal integrity and principled politics was somewhat damaged late in his Senate career by his involvement in the Crédit Mobilier scandal

The Crédit Mobilier scandal () was a two-part fraud conducted from 1864 to 1867 by the Union Pacific Railroad and the Crédit Mobilier of America construction company in the building of the eastern portion of the first transcontinental railroad f ...

.

Early life and education

Wilson was born inFarmington, New Hampshire

Farmington is a town in Strafford County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 6,722 at the 2020 census. Farmington is home to Blue Job State Forest, the Tebbetts Hill Reservation, and Baxter Lake.

The town center, where 3,824 peop ...

, on February 16, 1812, one of several children born to Winthrop and Abigail (Witham) Colbath. His father named him Jeremiah Jones Colbath after a wealthy neighbor who was a childless bachelor, vainly hoping that this gesture might result in an inheritance. Winthrop Colbath was a militia veteran of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

who worked as a day laborer and hired himself out to local farms and businesses, in addition to occasionally running a sawmill.

The Colbath family was impoverished; after a brief elementary education, at the age of 10 Wilson was indentured

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects an agreement between two parties. Although the term is most familiarly used to refer to a labor contract between an employer and a laborer with an indentured servant status, historically indentures we ...

to a neighboring farmer, where he worked as a laborer for the next 10 years. During this time two neighbors gave him books and Wilson enhanced his meager education by reading extensively on English history, American history and biographies of famous historical figures. At the end of his service he was given "six sheep and a yoke

A yoke is a wooden beam used between a pair of oxen or other animals to enable them to pull together on a load when working in pairs, as oxen usually do; some yokes are fitted to individual animals. There are several types of yoke, used in dif ...

of oxen

An ox (: oxen), also known as a bullock (in BrE, British, AusE, Australian, and IndE, Indian English), is a large bovine, trained and used as a draft animal. Oxen are commonly castration, castrated adult male cattle, because castration i ...

." Wilson immediately sold his animals for $85 (about $2,200 in 2021), which was the first money he had earned during his indenture.

Wilson apparently did not like his birth name, though the reasons given vary. Some sources indicate that he was not close to his family, or disliked his name because of his father's supposed intemperance and modest financial circumstances. Others indicate that he was called "Jed" and "Jerry," and disliked the nicknames so much that he resolved to change his name. Whatever the reason, when he turned 21 he successfully petitioned the New Hampshire General Court

The General Court of New Hampshire is the bicameral state legislature of the U.S. state of New Hampshire. The lower house is the New Hampshire House of Representatives with 400 members, and the upper house is the New Hampshire Senate with 24 me ...

to legally change it. He chose the name Henry Wilson, inspired either by a biography of a Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

teacher or a portrait from a book on English clergymen.

Career

After trying and failing to find work in New Hampshire, in 1833 Wilson walked more than one hundred miles to

After trying and failing to find work in New Hampshire, in 1833 Wilson walked more than one hundred miles to Natick, Massachusetts

Natick ( ) is a town in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. It is near the center of the MetroWest region of Massachusetts, with a population of 37,006 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. west of Boston, Natick is part o ...

, seeking employment or a trade. Having met William P. Legro, a shoemaker who was willing to train him, Wilson hired himself out for five months to learn to make leather shoes called brogans. Wilson learned the trade in a few weeks, bought out his employment contract for fifteen dollars, and opened his own shop, intending to save enough money to study law. Wilson had success as a shoemaker, and was able to save several hundred dollars in a relatively short time. This success gave rise to legends about Wilson's skill; according to one story that grew with retelling, he once attempted to make one hundred pairs of shoes without sleeping, and fell asleep with the one hundredth pair in his hand. Wilson's shoemaking

Shoemaking is the process of making footwear.

Originally, shoes were made one at a time by hand, often by groups of shoemakers, or '' cordwainers'' (sometimes misidentified as cobblers, who repair shoes rather than make them). In the 18th cen ...

experience led to the creation of the political nicknames his supporters later used to highlight his working class

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

roots—the "''Natick Cobbler''" and the "''Natick Shoemaker''".

During this time Wilson read extensively and joined the Natick Debating Society, where he developed into an accomplished speaker. Wilson's health suffered as the result of the long hours he worked making shoes, and he traveled to Virginia to recuperate. During a stop in Washington, D.C., he heard Congressional debates on slavery and abolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. ...

, and observed African American families being separated as they were bought and sold in the Washington slave trade. Wilson resolved to dedicate himself "to the cause of emancipation in America," and after regaining his health returned to New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

, where he furthered his education by attending several New Hampshire academies, including schools in Strafford, Wolfeboro, and Concord

Concord may refer to:

Meaning "agreement"

* Harmony, in music

* Agreement (linguistics), a change in the form of a word depending on grammatical features of other words

Arts and media

* ''Concord'' (video game), a defunct 2024 first-person sh ...

.

Having spent part of his savings on his traveling and schooling, and having lost some as the result of a loan that was not repaid, Wilson worked as a schoolteacher to get out of debt and begin saving money again, intending to start a business of his own. Beginning with an investment of only twelve dollars, Wilson started a shoe manufacturing company. This venture proved successful, and he eventually employed over 100 workers.

Political career

Wilson became active politically as a Whig, and campaigned forWilliam Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was the ninth president of the United States, serving from March 4 to April 4, 1841, the shortest presidency in U.S. history. He was also the first U.S. president to die in office, causin ...

in 1840. He had joined the Whigs out of disappointment with the fiscal policies of Democrats Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

and Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was the eighth president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as Attorney General o ...

, and like most Whigs blamed them for the Panic of 1837

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis in the United States that began a major depression (economics), depression which lasted until the mid-1840s. Profits, prices, and wages dropped, westward expansion was stalled, unemployment rose, and pes ...

. In 1840 he was also elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives

The Massachusetts House of Representatives is the lower house of the Massachusetts General Court, the State legislature (United States), state legislature of Massachusetts. It is composed of 160 members elected from 14 counties each divided into ...

, and served from 1841 to 1843.

Wilson was a member of the Massachusetts State Senate

The Massachusetts Senate is the upper house of the Massachusetts General Court, the bicameral state legislature of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The Senate comprises 40 elected members from 40 single-member senatorial districts in the s ...

from 1844 to 1846 and 1850 to 1852. From 1851 to 1852 he was the Senate's President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

.

As early as 1845, Wilson had started to become disenchanted with the Whigs as the party attempted to compromise on the slavery issue, and as a Conscience Whig he took steps including the organization of a convention in Concord

Concord may refer to:

Meaning "agreement"

* Harmony, in music

* Agreement (linguistics), a change in the form of a word depending on grammatical features of other words

Arts and media

* ''Concord'' (video game), a defunct 2024 first-person sh ...

opposed to the annexation of Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

because it would expand slavery. As a result of this effort, in late 1845 Wilson and abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier

John Greenleaf Whittier (December 17, 1807 – September 7, 1892) was an American Quaker poet and advocate of the abolition of slavery in the United States. Frequently listed as one of the fireside poets, he was influenced by the Scottish poet ...

were chosen to submit in person a petition to Congress containing the signatures of 65,000 Massachusetts residents opposed to Texas annexation.

Wilson was a delegate to the 1848 Whig National Convention

The 1848 Whig National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held from June 7 to 9 in Philadelphia. It nominated the Whig Party's candidates for president and vice president in the 1848 election. The convention selected General ...

, but left the party after it nominated slave owner Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military officer and politician who was the 12th president of the United States, serving from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States ...

for president and took no position on the Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful 1846 proposal in the United States Congress to ban slavery in territory acquired from Mexico in the Mexican–American War. The conflict over the Wilmot Proviso was one of the major events leading to the ...

, which would have prohibited slavery in territory acquired from Mexico in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

. Wilson and Charles Allen, another Massachusetts delegate, withdrew from the convention, and called for a new meeting of anti-slavery advocates in Buffalo

Buffalo most commonly refers to:

* True buffalo or Bubalina, a subtribe of wild cattle, including most "Old World" buffalo, such as water buffalo

* Bison, a genus of wild cattle, including the American buffalo

* Buffalo, New York, a city in the n ...

, which launched the Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party, also called the Free Democratic Party or the Free Democracy, was a political party in the United States from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party. The party was focused o ...

.

Having left the Whig Party, Wilson worked to build coalitions with others opposed to slavery, including Free Soilers, anti-slavery Democrats, Barnburners

The Barnburners and Hunkers were the names of two opposing factions of the New York Democratic Party in the mid-19th century. The main issue dividing the two factions was that of slavery, with the Barnburners being the anti-slavery faction. Whil ...

from New York's Democratic Party, the Liberty Party, the anti-slavery elements of the Whig Party, and anti-slavery members of the Know Nothing

The American Party, known as the Native American Party before 1855 and colloquially referred to as the Know Nothings, or the Know Nothing Party, was an Old Stock Americans, Old Stock Nativism in United States politics, nativist political movem ...

or Native American Party. Although Wilson's new political coalition was initially castigated by "straight party" adherents of the mainstream Democratic and Whig parties, Wilson was successful in an effort to broker an alliance between the minority Free Soil and Democratic parties in the state elections of 1850, notably resulting in the election of Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1851 until his death in 1874. Before and during the American Civil War, he was a leading American ...

to the Senate.

From 1848 to 1851 Wilson was the owner and editor of the ''Boston Republican'', which from 1841 to 1848 was a Whig outlet, and from 1848 to 1851 was the main Free Soil Party newspaper.

During his service in the Massachusetts legislature, Wilson took note that participation in the state militia had declined, and that it was not in a state of readiness. In addition to undertaking legislative efforts to provide uniforms and other equipment, in 1843 Wilson joined the militia himself, becoming a major in the 1st Artillery Regiment, which he later commanded with the rank of colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

. In 1846 Wilson was promoted to brigadier general as commander of the Massachusetts Militia's 3rd Brigade, a position he held until 1852.

Free Soil Party organizer

In 1852, Wilson was chairman of the Free Soil Party's national convention inPittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, second-most populous city in Pennsylvania (after Philadelphia) and the List of Un ...

, which nominated John P. Hale

John Parker Hale (March 31, 1806November 19, 1873) was an American politician and lawyer from New Hampshire. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1843 to 1845 and in the United States Senate from 1847 to 1853 and again fro ...

for president and George Washington Julian

George Washington Julian (May 5, 1817 – July 7, 1899) was a politician, lawyer, and writer from Indiana who served in the United States House of Representatives during the 19th century. A leading opponent of slavery, Julian was the Free Soi ...

for vice president. Later that year he was a Free Soil candidate for U.S. Representative

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

, and lost to Whig Tappan Wentworth

Theodore Trapplan "Tappan" Michael Wentworth (February 24, 1802 – June 12, 1875) was an American lawyer and politician who served one term as a U.S. Representative from Massachusetts from 1853 to 1855.

Early life and career

Wentworth was b ...

. He was a delegate to the state constitutional convention in 1853, which proposed a series of political and governmental reforms that were defeated by voters in a post-convention popular referendum. He ran unsuccessfully for Governor of Massachusetts

The governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the head of government of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The governor is the chief executive, head of the state cabinet and the commander-in-chief of the commonw ...

as a Free Soil candidate in 1853 and 1854, but declined to be a candidate again in 1855 because he had his sights set on the U.S. Senate.

U.S. Senator (1855–1873)

In 1855 Wilson was elected to theUnited States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

by a coalition of Free-Soilers, Know Nothing

The American Party, known as the Native American Party before 1855 and colloquially referred to as the Know Nothings, or the Know Nothing Party, was an Old Stock Americans, Old Stock Nativism in United States politics, nativist political movem ...

s, and anti-slavery Democrats, filling the vacancy caused by the resignation of Edward Everett

Edward Everett (April 11, 1794 – January 15, 1865) was an American politician, Unitarian pastor, educator, diplomat, and orator from Massachusetts. Everett, as a Whig, served as U.S. representative, U.S. senator, the 15th governor of Mas ...

. He had briefly joined the Know-Nothings in an attempt to strengthen their anti-slavery efforts, but aligned himself with the Republican Party at its creation, formed largely along the lines of the anti-slavery coalition Wilson had helped develop and nurture. Wilson was reelected as a Republican in 1859, 1865 and 1871, and served from January 31, 1855, to March 3, 1873, when he resigned in order to begin his vice presidential term on March 4.

In his first Senate speech in 1855, Wilson continued to align himself with the abolitionists, who wanted to immediately end slavery in the United States and its territories. In his speech, Wilson said he wanted to abolish slavery "wherever we are morally and legally responsible for its existence", including Washington, D.C., Wilson also demanded repeal of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was a law passed by the 31st United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers.

The Act was one ...

, believing the federal government should have no responsibility for enforcing slavery, and that once the act was repealed tensions between slavery proponents and opponents would abate, enabling those Southerners who opposed slavery to help end it in their own time.

On May 22, 1856,

On May 22, 1856, Preston Brooks

Preston Smith Brooks (August 5, 1819 – January 27, 1857) was an American slaver, politician, and member of the U.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina, serving as a member of the Democratic Party from 1853 until his resignation i ...

brutally assaulted Senator Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1851 until his death in 1874. Before and during the American Civil War, he was a leading American ...

on the Senate floor, leaving Sumner bloody and unconscious. Brooks had been upset over Sumner's ''Crimes Against Kansas'' speech that denounced the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law b ...

. After the beating, Sumner received medical treatment at the Capitol, following which Wilson and Nathaniel P. Banks

Nathaniel Prentice (or Prentiss) Banks (January 30, 1816 – September 1, 1894) was an American politician from Massachusetts and a Union Army, Union general during the American Civil War, Civil War. A millworker, Banks became prominent in local ...

, the Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hung ...

, aided Sumner to travel by carriage to his lodgings, where he received further medical attention. Wilson called the beating by Brooks "brutal, murderous, and cowardly". Brooks immediately challenged Wilson to a duel. Wilson declined, saying that he could not legally or by personal conviction participate. In reference to a rumor that Brooks might attack Wilson in the Senate as he had attacked Sumner, Wilson told the press "I have sought no controversy, and I seek none, but I shall go where duty requires, uninfluenced by threats of any kind." The rumors proved unfounded, and Wilson continued his Senate duties without incident.

The attack on Sumner took place just one day after pro-slavery Missourians killed one person in the burning and sacking of Lawrence, Kansas

Lawrence is a city in and the county seat of Douglas County, Kansas, United States, and the sixth-largest city in the state. It is in the northeastern sector of the state, astride Interstate 70 in Kansas, Interstate 70, between the Kansas River ...

. The attack on Sumner and the sacking of Lawrence were later viewed as two of the incidents which symbolized the "breakdown of reasoned discourse." This phrase came to describe the period when activists and politicians moved past the debate of anti-slavery and pro-slavery speeches and non-violent actions, and into the realm of physical violence, which in part hastened the onset of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

.

In June 1858 Wilson made a Senate speech in which he suggested corruption in the government of California and implied complicity on the part of Senator

In June 1858 Wilson made a Senate speech in which he suggested corruption in the government of California and implied complicity on the part of Senator William M. Gwin

William McKendree Gwin (October 9, 1805 – September 3, 1885) was an American medical doctor and politician who served in elected office in Mississippi and California. In California he shared the distinction, along with John C. Frémont, of bein ...

, a pro-slavery Democrat who had served as a member of Congress from Mississippi before moving to California. Gwin was backed by a powerful Southern coalition of pro-slavery Democrats called the Chivs, who had a monopoly on federal patronage in California. Gwin accused Wilson of demagoguery, and Wilson responded by saying he would rather be thought a demagogue

A demagogue (; ; ), or rabble-rouser, is a political leader in a democracy who gains popularity by arousing the common people against elites, especially through oratory that whips up the passions of crowds, Appeal to emotion, appealing to emo ...

than a thief. Gwin then challenged Wilson to a duel; Wilson declined in the same terms he used to decline a duel with Preston Brooks. In fact neither Gwin nor Wilson wanted to follow through, and commentary about the dispute broke down along partisan lines. One pro-Gwin editorial called the insinuation that Gwin was corrupt "a most malignant falsehood", while a pro-Wilson editorial called his reluctance to take part in a duel evidence that he was "honest" and "conscientious", and had "more respect for the laws of this country than his adversary". After several attempts to find a face-saving compromise, Gwin and Wilson agreed to refer their dispute to three senators who would serve as mediators. William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (; May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States senator. A determined opp ...

, John J. Crittenden

John Jordan Crittenden (September 10, 1787 – July 26, 1863) was an American statesman and politician from the U.S. state of Kentucky. He represented the state in the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate and twice served as Uni ...

and Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the only President of the Confederate States of America, president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the Unite ...

were chosen, and produced an acceptable solution. At their instigation, Wilson stated to the Senate that he had not meant to impugn Gwin's honor, and Gwin replied by saying that he had not meant to question Wilson's motives. In addition, the mediators caused to be removed from the Senate record both Gwin's remarks about demagoguery and Wilson's suggestion that Gwin was a thief.

Civil War

During theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, Wilson was Chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs and the Militia, and later the Committee on Military Affairs. In that capacity, he oversaw action on over 15,000 War and Navy Department nominations that Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

submitted during the course of the war, and worked closely with him on legislation affecting the Army and Navy.

In the summer of 1861, after the congressional session ended, Wilson returned to Massachusetts and recruited and equipped nearly 2,300 men in forty days. They were mustered in as the

In the summer of 1861, after the congressional session ended, Wilson returned to Massachusetts and recruited and equipped nearly 2,300 men in forty days. They were mustered in as the 22nd Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry

The 22nd Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry was an infantry regiment in the Union army during the American Civil War. The 22nd Massachusetts was organized by Senator Henry Wilson (future Vice-president during the Ulysses Grant administra ...

, which he commanded as a colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

from September 27 to October 29, an honor sometimes accorded to the individual responsible for raising and equipping a regiment. After the war, he became an early member of the Pennsylvania Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States

The Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), or, simply, the Loyal Legion, is a United States military order organized on April 15, 1865, by three veteran officers of the Union Army. The original membership was consisted ...

.

Wilson's experience in the militia, service with the 22nd Massachusetts, and chairmanship of the Military Affairs Committee provided him with more practical military knowledge and training than any other Senator. He made use of this experience throughout the war to frame, explain, defend and advocate for legislation on military matters, including enlistment of soldiers and sailors, and organizing and supplying the rapidly expanding Union Army and Union Navy.

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as Commanding General of the United States Army from 1841 to 1861, and was a veteran of the War of 1812, American Indian Wars, Mexica ...

, the Commanding General of the United States Army

Commanding General of the United States Army was the title given to the service chief and highest-ranking officer of the United States Army (and its predecessor the Continental Army), prior to the establishment of the Chief of Staff of the Unit ...

since 1841, said that during the session of Congress that ended in the Spring of 1861 Wilson had done more work "than all the chairmen of the military committees had done for the last 20 years." On January 27, 1862, Simon Cameron

Simon Cameron (March 8, 1799June 26, 1889) was an American businessman and politician who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate and served as United States Secretary of War under President Abraham Lincoln at the start of the Ameri ...

, the recently resigned Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

, echoed Scott's sentiments when he said that "no man, in my opinion, in the whole country, has done more to aid the war department in preparing the mighty nion

Nion (ᚅ) is the Irish name of the fifth letter ( Irish "letter": sing.''fid'', pl.''feda'') of the Ogham alphabet, with phonetic value The Old Irish letter name, Nin, may derive from Old Irish homonyms ''nin/ninach'' meaning "fork/forked" ...

army now under arms than yourself ilson

Ilson Wilians Rodrigues (born 12 March 1979) is a Brazilian former footballer

A football player or footballer is a sportsperson who plays one of the different types of football. The main types of football are association football, America ...

"

Greenhow controversy

In July 1861, Wilson was present for the Civil War's first major battle at Bull Run Creek inManassas, Virginia

Manassas (), formerly Manassas Junction, is an independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia, United States. The population was 42,772 at the 2020 Census. It is the county seat of ...

, an event which many senators, representatives, newspaper reporters, and Washington society elite traveled from the city to observe in anticipation of a quick Union victory. Riding out in a carriage in the early morning, Wilson brought a picnic hamper of sandwiches to feed Union troops. However, the battle turned into a Confederate rout, forcing Union troops to make a panicky retreat. Caught up in the chaos, Wilson was almost captured by the Confederates, while his carriage was crushed, and he had to make an embarrassing return to Washington on foot. The result of this battle had a sobering effect on many in the North, causing widespread realization that Union victory would not be won without a prolonged struggle.

In seeking to place blame for the Union defeat, some in Washington spread rumors that Wilson had revealed plans for the Union invasion of Virginia to Washington society figure and Southern spy Rose O'Neal Greenhow

Rose O'Neal Greenhow (1813– October 1, 1864) was a famous Confederate spy during the American Civil War. A socialite in Washington, D.C., during the period before the war, she moved in important political circles and cultivated friendship ...

. According to the story, although he was married, Wilson had seen a great deal of Mrs. Greenhow, and may have told her about the plans of Major General Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell (October 15, 1818 – May 4, 1885) was an American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War. In 1862, he was given command of the ...

, which Mrs. Greenhow then conveyed to Confederate forces under Major General P. G. T. Beauregard

Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard (May 28, 1818 – February 20, 1893) was an American military officer known as being the Confederate general who started the American Civil War at the battle of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Today, he is comm ...

. One Wilson biography suggests someone else—Wilson's Senate clerk Horace White—was also friendly with Mrs. Greenhow and could have leaked the invasion plan, although it is also possible that neither Wilson nor White did so.

Equal rights activism

On December 16, 1861, Wilson introduced a bill to abolish slavery in Washington, D.C., something he had desired to do since his visit to the nation's capital 25 years earlier. At this time fugitive slaves from the war were being held in prisons of Washington, D.C., and faced the possibility of return to their owners. Wilson said of his bill that it would "blot out slavery forever from the nation's capital". The measure met bitter opposition from the Democrats who remained in the Senate after those from the southern states vacated their seats to join the Confederacy, but it passed. After passage in the House, President Lincoln signed Wilson's bill into law on April 16, 1862. On July 8, 1862, Wilson drafted a measure that authorized the President to enlist African Americans who had been held in slavery and were deemed competent for military service, and employ them to construct fortifications and carry out other military-related manual labor, the first step towards allowing African Americans to serve as soldiers. President Lincoln signed the amendment into law on July 17. Wilson's law paid African Americans in the military $10 monthly, which was effectively $7 a month after deductions for food and clothing, while white soldiers were paid effectively $14 monthly.John G. Nicolay and John Hay (2009), ''Life of Abraham Lincoln'' Volume VI, pp. 441–442

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln's

On July 8, 1862, Wilson drafted a measure that authorized the President to enlist African Americans who had been held in slavery and were deemed competent for military service, and employ them to construct fortifications and carry out other military-related manual labor, the first step towards allowing African Americans to serve as soldiers. President Lincoln signed the amendment into law on July 17. Wilson's law paid African Americans in the military $10 monthly, which was effectively $7 a month after deductions for food and clothing, while white soldiers were paid effectively $14 monthly.John G. Nicolay and John Hay (2009), ''Life of Abraham Lincoln'' Volume VI, pp. 441–442

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the eff ...

freed all slaves held in bondage in the Southern states or territories then in rebellion against the federal government. On February 2, 1863, Congress built on Wilson's 1862 law by passing a bill authored by Pennsylvania Congressman Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was an American politician and lawyer who served as a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, being one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Histo ...

, which authorized the enlistment of 150,000 African Americans into the Union Army for service as uniformed soldiers.Allan C. Bogue (December 1987), "William Parker Cutler's Congressional Diary of 1862–63," ''Civil War History'', p. 329 (February 2, 1863)

On February 17, 1863, Wilson introduced a bill that would federally fund elementary education for African American youth in Washington, D.C. President Lincoln signed the bill into law on March 3, 1863.

Wilson added an amendment to the 1864 Enrollment Act

The Enrollment Act of 1863 (, enacted March 3, 1863) also known as the Civil War Military Draft Act, was an Act passed by the United States Congress during the American Civil War to provide fresh manpower for the Union Army. The Act was the fir ...

which provided that formerly enslaved African Americans from slave holding states remaining in the Union who enlisted in the Union Army would be considered permanently free by action of the federal government, rather than through individual emancipation by the states or their owners, thus preventing the possibility of their re-enslavement. President Lincoln signed this measure into law on February 24, 1864, freeing more than 20,000 slaves in Kentucky alone.

Wilson supported the right of black men to join the uniformed services. Once African Americans were permitted to serve in the military, Wilson advocated in the Senate for them to receive equal pay and other benefits. A Vermont newspaper portrayed Wilson's position and enhanced his nationwide reputation as an abolitionist by editorializing "Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, in a speech in the U.S. Senate on Friday, said he thought our treatment of the negro soldiers almost as bad as that of the rebels at Fort Pillow. This is hardly an exaggeration."

On June 15, 1864, Wilson succeeded in adding a provision to an appropriations bill which addressed the pay disparity between whites and blacks in the military by authorizing equal salaries and benefits for African American soldiers. Wilson's provision stated that "all persons of color who had been or might be mustered into the military service should receive the same uniform, clothing, rations, medical and hospital attendance, and pay" as white soldiers, to date from January 1864.

Wilson introduced a bill in Congress which would free in the Union's slave-holding states the still-enslaved families of former slaves serving in the Union Army. In advocating for passage, Wilson argued that allowing the family members of soldiers to remain in slavery was a "burning shame to this country ... Let us hasten the enactment ... that, on the forehead of the soldier's wife and the soldier's child, no man can write "Slave". President Lincoln signed the measure into law on March 3, 1865, and an estimated 75,000 African American women and children were freed in Kentucky alone.

Wilson supported the right of black men to join the uniformed services. Once African Americans were permitted to serve in the military, Wilson advocated in the Senate for them to receive equal pay and other benefits. A Vermont newspaper portrayed Wilson's position and enhanced his nationwide reputation as an abolitionist by editorializing "Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, in a speech in the U.S. Senate on Friday, said he thought our treatment of the negro soldiers almost as bad as that of the rebels at Fort Pillow. This is hardly an exaggeration."

On June 15, 1864, Wilson succeeded in adding a provision to an appropriations bill which addressed the pay disparity between whites and blacks in the military by authorizing equal salaries and benefits for African American soldiers. Wilson's provision stated that "all persons of color who had been or might be mustered into the military service should receive the same uniform, clothing, rations, medical and hospital attendance, and pay" as white soldiers, to date from January 1864.

Wilson introduced a bill in Congress which would free in the Union's slave-holding states the still-enslaved families of former slaves serving in the Union Army. In advocating for passage, Wilson argued that allowing the family members of soldiers to remain in slavery was a "burning shame to this country ... Let us hasten the enactment ... that, on the forehead of the soldier's wife and the soldier's child, no man can write "Slave". President Lincoln signed the measure into law on March 3, 1865, and an estimated 75,000 African American women and children were freed in Kentucky alone.

Creation of the National Academy of Sciences

In early 1863,Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz ( ; ) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

Spending his early life in Switzerland, he recei ...

, one of a group of Cambridge, Massachusetts scientists interested in establishing an academy of sciences modeled on the Royal Society and the French Institute, approached Wilson with the idea of establishing such an academy. On February 11, 1863, a Permanent Commission, which comprised Admiral Charles Henry Davis and the scientists Joseph Henry and Alexander Dallas Bache, was appointed within the Navy Department and given the task of evaluating and reporting on the inventions and other ideas submitted by citizens in order to aid the war effort. The establishment of the Permanent Commission prompted Davis to suggest that "the whole plan, so long entertained, of the Academy could be successfully carried out if an act of incorporation were boldly asked for in the name of some of the leading men of science, from different parts of the country." Just prior to the establishment of the Permanent Commission, Agassiz had written to Wilson suggesting that a "National Academy of Sciences" could be established and recommending that if Wilson were favorable, Bache, "to whom the scientific men of the country look as upon their leader…can draft in twenty four hours a complete plan for you…"

On February 19, Agassiz came to Washington from Cambridge to accept appointment, upon Wilson's nomination, to the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution. Agassiz went directly from the train to Bache's house, where he met with Bache, Wilson, and the scientists Benjamin Apthorp Gould and Benjamin Peirce. Working from plans laid out by Bache and Davis, the group drafted a bill for the establishment of a National Academy of Sciences, to be put before Congress.Cochrane, Rexmond, The National Academy of Sciences, the First Hundred Years 1863-1963 (Washington, DC, The National Academy of Sciences, 1978), p. 53.

On February 20, Wilson introduced the bill in the Senate. Just before adjournment on March 3, 1863, Wilson asked the Senate "to take up a bill…to incorporate the National Academy of Sciences." The Senate passed the bill by voice vote; later that day it was sent to the House of Representatives, which passed it without comment. President Lincoln signed it into law before midnight that same day.

Reconstruction and civil rights

When

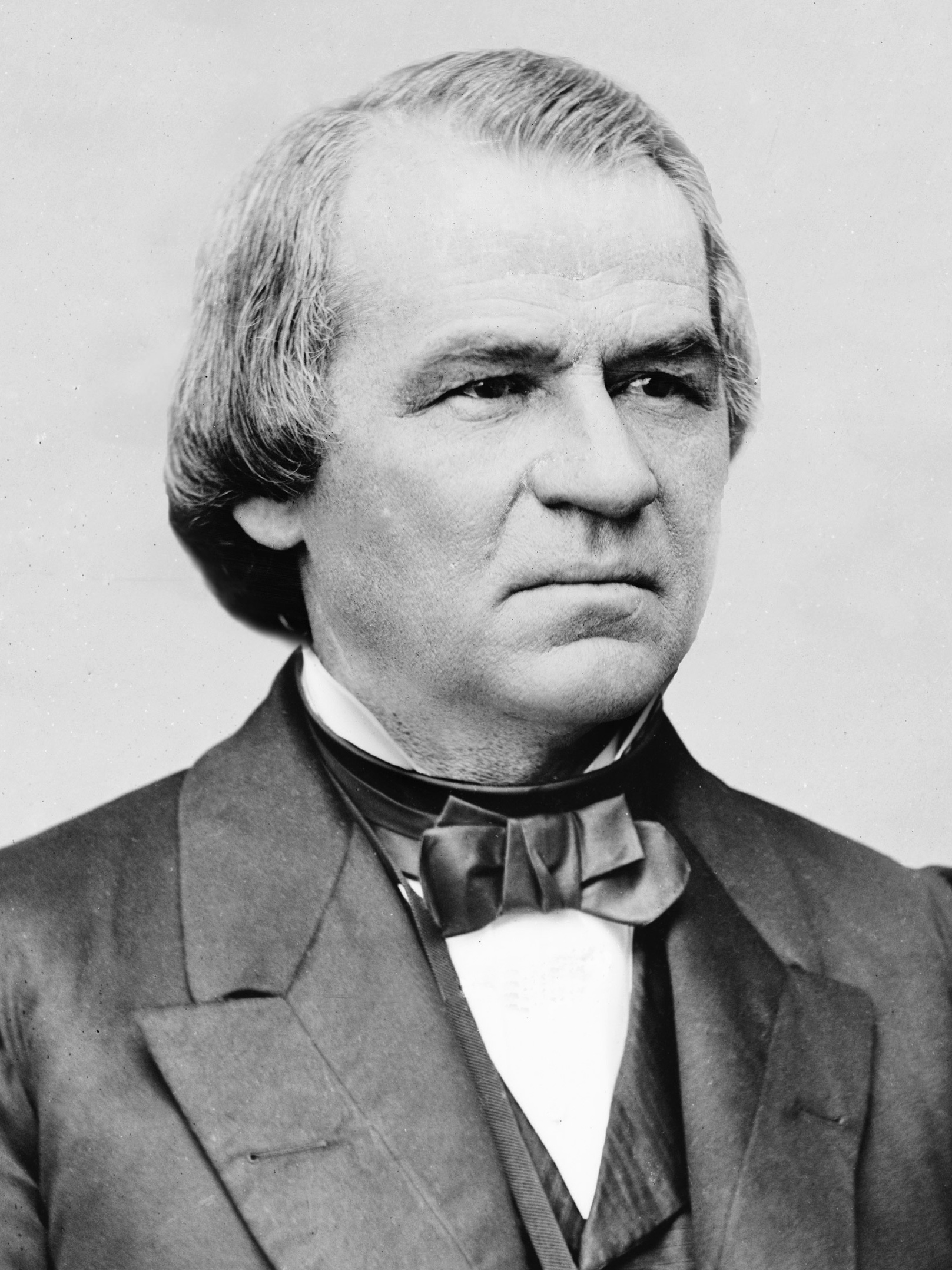

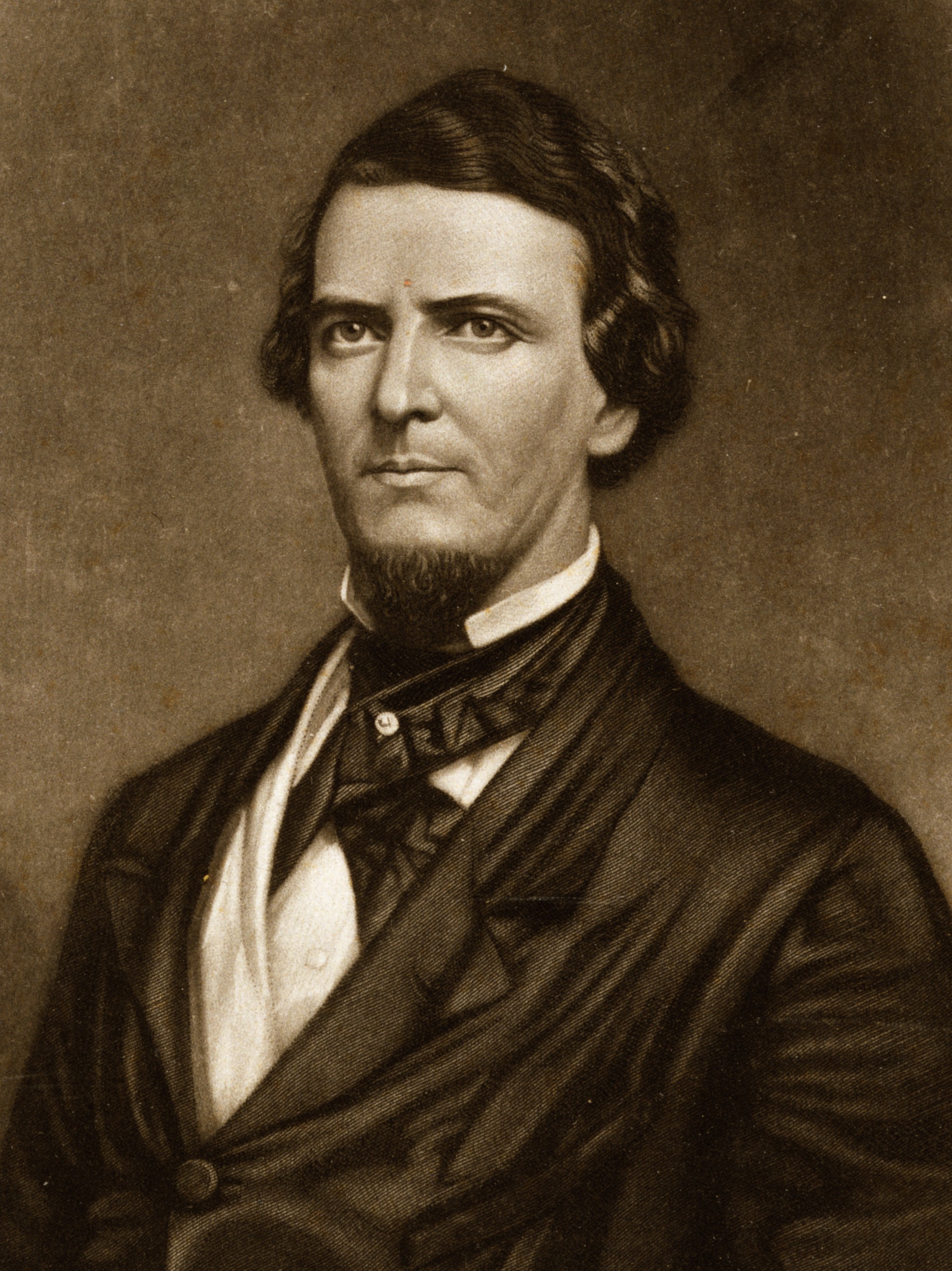

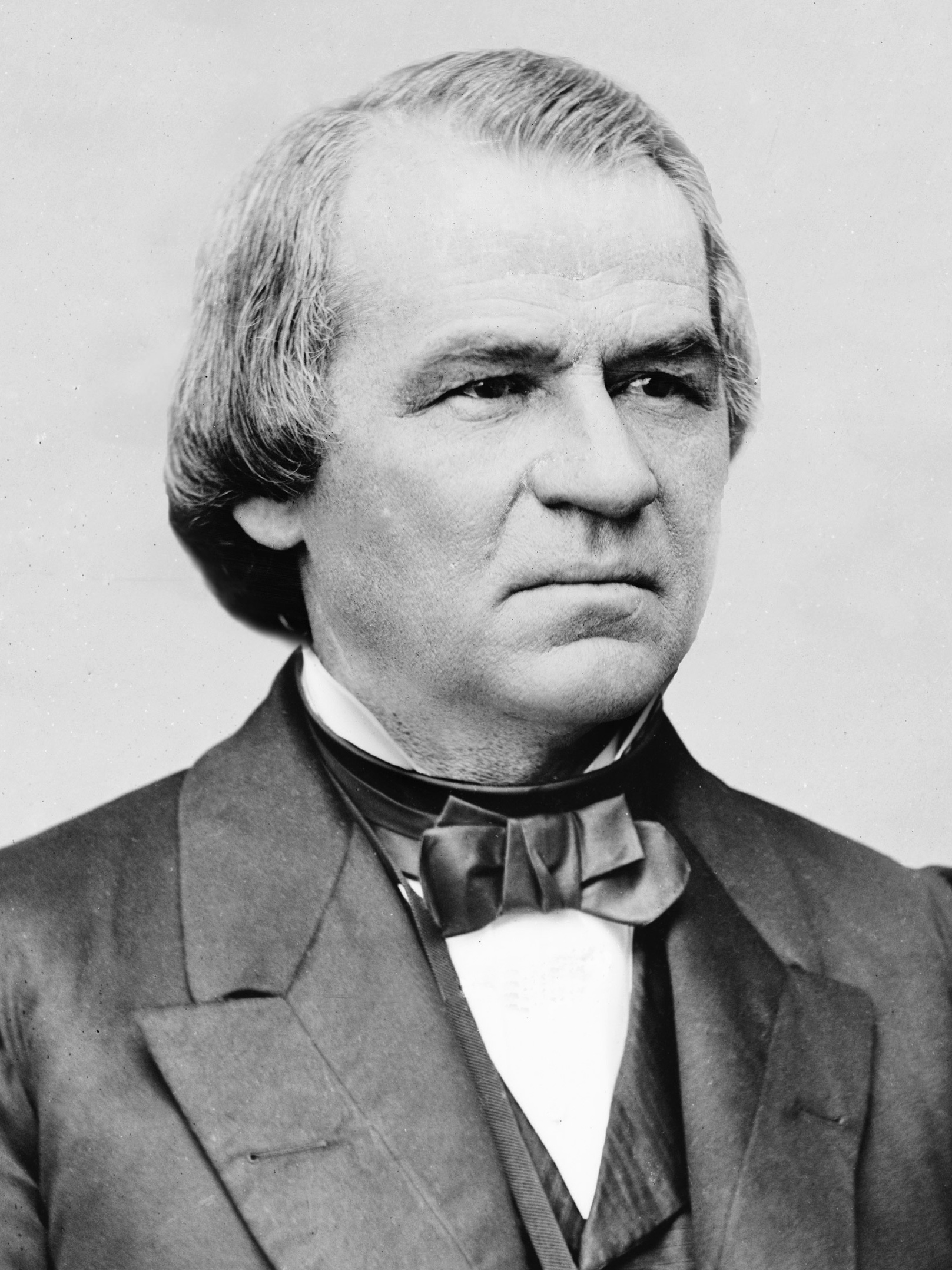

When Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

assumed the presidency after President Lincoln's assassination in April 1865, Senators Sumner and Wilson both hoped Johnson would support the policies of the Republican Party, since Johnson, a Democrat, had been elected with Lincoln on a pro-Union ticket. After the Civil War ended with a Union Victory in May 1865, the defeated former Confederacy was ruined. It had been devastated economically and politically, and much of its infrastructure had been destroyed during the war. The opportunity was ripe for Congress and Johnson to work together on terms for Southern restoration and reconstruction. Instead, Johnson launched his own reconstruction policy, which was seen as more lenient to former Confederates, and excluded African American citizenship. When Congress opened the session which began in December 1865, Johnson's policy included a demand for admission of Southern Senators and Representatives, nearly all Democrats, including many former Confederates. Congress, still in Republican hands, responded by refusing to allow the Southern Senators and Representatives to take their seats, beginning a rift between Republicans in Congress and the President. Wilson favored allowing only persons who had been loyal to the United States to serve in positions of political power in the former Confederacy, and believed that Congress, not the president, had the power to reconstruct the southern states. As a result, Wilson joined forces with the Congressmen and Senators known as Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans were a political faction within the Republican Party originating from the party's founding in 1854—some six years before the Civil War—until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reconstruction. They ca ...

, those most strongly opposed to Johnson.

On December 21, 1865, two days after the announcement that the states had ratified the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery, Wilson introduced a bill to protect the civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

of African Americans. Although Wilson's bill failed to pass Congress it was effectively the same bill as the Civil Rights Act of 1866 that passed Congress over Johnson's veto on April 9, 1866.

The rift between the Radicals, including Wilson, and President Johnson grew as Johnson attempted to implement his more lenient Reconstruction policies. Johnson vetoed the bill to establish the Freedmen's Bureau, as well as other Radical measures to protect African American civil rights—measures which Wilson supported. Wilson supported the effort to impeach Johnson, saying that Johnson was "unworthy, if not criminal" in his conduct by resisting Congressional Reconstruction measures, many of which were passed over his vetoes. At the 1868 Senate trial Wilson voted for Johnson's conviction, but Republicans fell one vote short of the two-thirds majority needed to remove Johnson from office. (With 36 "guilty" votes needed for removal, the Senate results were 35 to 19 on all three post-trial ballots.)

On May 27, 1868, Wilson spoke before the Senate to forcefully advocate the readmission of Arkansas. Taking the lead on this issue, Wilson urged immediate action, saying that the new state government was constitutional, and was composed of loyal Southerners, African Americans who were formerly enslaved, and Northerners who had moved south. Wilson said he would not agree to Congressional adjournment until all Southern states with reconstructed governments loyal to the United States that adopted new constitutions were readmitted. The ''New York Tribune'' called Wilson's speech "strong" and said that Wilson steered the Senate away from "legal hair-splitting". Within a month the Senate had acted, and Arkansas was readmitted on June 22, 1868. President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

, who succeeded Johnson in 1869, was more supportive of Congressional Reconstruction, and the remaining former Confederate states that had not rejoined the Union were readmitted during his first term. Federal troops continued to be based in the former Confederate states, allowing Republicans to control state governments, and African Americans to vote and hold federal office.

In 1870 Hiram Rhodes Revels, Hiram Revels was elected to the U.S. Senate by the reconstructed Mississippi Legislature. Revels was the first African American elected to the Senate, and Senate Democrats attempted to prevent him from being seated. Wilson defended Revels's election, and presented as evidence of its validity signatures from the clerks of the Mississippi House of Representatives and Mississippi State Senate, as well as that of Adelbert Ames, the military Governor of Mississippi. Wilson argued that Revels's skin color was not a bar to Senate service, and connected the role of the Senate to Christianity's Golden Rule#Christianity, Golden Rule of doing to others as one would have done to oneself. The Senate voted to seat Revels, and after he took the oath of office Wilson personally escorted him to his desk as journalists recorded the historic event.

1868 vice presidential campaign

Prior to the presidential election of 1868, Wilson toured the South giving political speeches. Many in the press believed Wilson was promoting himself to be the Republican presidential candidate. Wilson, however, supported the Civil War hero GeneralUlysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

. During Reconstruction Grant supported Republican Congressional initiatives rather than President Johnson's, and during the dispute over the Tenure of Office Act (1867), Tenure of Office Act which led to Johnson's impeachment, Grant served as temporary Secretary of War, but then returned the Department to Radical ally Edwin M. Stanton's control over Johnson's strong objection, making Grant a favorite to many Radicals.

Wilson actually desired to be vice president. During his speech-making tour of the South, Wilson moderated his tougher Reconstruction ideology, advocating a biracial society, while urging African Americans and their white supporters to take a conciliatory and peaceful approach with Southern whites who had favored the Confederacy. Radicals, including Benjamin Wade, were stunned by Wilson's remarks, believing blacks should not be subject to their former white owners. At the 1868 Republican National Convention, Republican Convention, Wilson, Wade and others competed for the vice presidential nomination, and Wilson had support among Southern delegates, but he failed to win after five ballots. Wade was also unable to win the convention vote, and Wilson's delegates eventually switched their votes to Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax, who won the nomination and went on to win the general election with Grant at the head of the ticket. After Grant and Colfax won the 1868 election Wilson declined to serve as