Henry Of Navarre on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Henry IV (; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry (''le Bon Roi Henri'') or Henry the Great (''Henri le Grand''), was

Henry was born on the night of 12-to-13 December 1553 at Pau, the capital of the joint

Henry was born on the night of 12-to-13 December 1553 at Pau, the capital of the joint

During the First French War of Religion (1562–1563), Henry was moved to Montargis for his safety, where he was placed under the protection of

During the First French War of Religion (1562–1563), Henry was moved to Montargis for his safety, where he was placed under the protection of

When Cardinal de Bourbon died in 1590, the League could not agree on a new candidate at the Estates General called to settle the question, also attended by the envoys of Spain. While some supported various Guise candidates, the strongest candidate was probably the

When Cardinal de Bourbon died in 1590, the League could not agree on a new candidate at the Estates General called to settle the question, also attended by the envoys of Spain. While some supported various Guise candidates, the strongest candidate was probably the  The

The

On 25 July 1593, with the encouragement of his mistress, , Henry permanently renounced Protestantism and converted to Catholicism to secure his hold on the French crown, thereby earning the resentment of the

On 25 July 1593, with the encouragement of his mistress, , Henry permanently renounced Protestantism and converted to Catholicism to secure his hold on the French crown, thereby earning the resentment of the

gutenberg.org

/ref> although the attribution is doubtful. His acceptance of Catholicism secured the allegiance of the vast majority of his subjects.

Henry IV successfully ended the civil wars. He and his ministers appeased Catholic leaders using bribes of about 7 million écus, a sum greater than France's annual revenue. In combination with other fiscal problems, the king was faced with a financial crisis by the middle of the 1590s. In response to this crisis, Henry resolved to convene an Assembly of Notables in November 1596 that he hoped would approve the creation of new royal revenues. The assembly approved the creation of a new tax on goods entering towns that would be known as the ''pancarte'', however in 1597 the crown was again rocked by military crisis when the Spanish seized Amiens.

Huguenot leaders were placated by the

Henry IV successfully ended the civil wars. He and his ministers appeased Catholic leaders using bribes of about 7 million écus, a sum greater than France's annual revenue. In combination with other fiscal problems, the king was faced with a financial crisis by the middle of the 1590s. In response to this crisis, Henry resolved to convene an Assembly of Notables in November 1596 that he hoped would approve the creation of new royal revenues. The assembly approved the creation of a new tax on goods entering towns that would be known as the ''pancarte'', however in 1597 the crown was again rocked by military crisis when the Spanish seized Amiens.

Huguenot leaders were placated by the

Even before Henry's accession to the French throne, the French Huguenots were in contact with Aragonese

Even before Henry's accession to the French throne, the French Huguenots were in contact with Aragonese

/ref> Two ships, the ''Croissant'' and the ''Corbin'', were sent around the

File:Assassination of Henry IV by Gaspar Bouttats.jpg, ''Assassination of Henry IV'',

engraving by Gaspar Bouttats File:François Ravaillac.jpg, His assassin, François Ravaillac, brandishing his dagger File:Pierre Firens - Le Roi Est Mort continues at the Palace of Versailles - 1610.jpg, Pierre Firens - "Le Roi Est Mort continues at the Palace of Versailles". 1610 File:Henry IV of France as he lay in state after his murder in the year 1610, engraving after Quesnel - Gallica 2010 (adjusted).jpg, Lying in state at the

In 1614, four years after Henry IV's death, his

In 1614, four years after Henry IV's death, his

File:Armoiries Antoine de Bourbon.svg, From 1562,

as Prince of Béarn and Duke of Vendôme File:Henri de Bourbon Roi de Navarre.svg, From 1572,

as King of Navarre File:Arms of France and Navarre (1589-1790).svg, From 1589,

as King of France and Navarre (also used by his successors) File:Grand Royal Coat of Arms of France & Navarre.svg, Grand Royal Coat of Arms of Henry and the House of Bourbon as Kings of France and Navarre (1589–1789)

online

King of Navarre

This is a list of the kings and queens of kingdom of Pamplona, Pamplona, later kingdom of Navarre, Navarre. Pamplona was the primary name of the kingdom until its union with Kingdom of Aragon, Aragon (1076–1134). However, the territorial desig ...

(as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France

France was ruled by monarchs from the establishment of the kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I, king of the Fra ...

from 1589 to 1610. He was the first monarch of France from the House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a dynasty that originated in the Kingdom of France as a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Kingdom of Navarre, Navarre in the 16th century. A br ...

, a cadet branch

A cadet branch consists of the male-line descendants of a monarch's or patriarch's younger sons ( cadets). In the ruling dynasties and noble families of much of Europe and Asia, the family's major assets (realm, titles, fiefs, property and incom ...

of the Capetian dynasty. He pragmatically balanced the interests of the Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

parties in France, as well as among the European states. He was assassinated in Paris in 1610 by a Catholic zealot, and was succeeded by his son Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown.

...

.

Henry was baptised a Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

but raised as a Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

in the Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

faith by his mother, Queen Jeanne III of Navarre. He inherited the throne of Navarre in 1572 on his mother's death. As a Huguenot, Henry was involved in the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion were a series of civil wars between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants (called Huguenots) from 1562 to 1598. Between two and four million people died from violence, famine or disease di ...

, barely escaping assassination in the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre. He later led Protestant forces against the French royal army. Henry inherited the throne of France in 1589 upon the death of Henry III. Henry IV initially kept the Protestant faith (the only French king to do so) and had to fight against the Catholic League, which refused to accept a Protestant monarch. After four years of military stalemate, Henry converted to Catholicism, reportedly saying that "Paris is well worth a Mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

". As a pragmatic politician ('' politique''), he promulgated the Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was an edict signed in April 1598 by Henry IV of France, King Henry IV and granted the minority Calvinism, Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was predominantl ...

(1598), which guaranteed religious liberties to Protestants, thereby effectively ending the French Wars of Religion.

An active ruler, Henry worked to regularize state finance, promote agriculture, eliminate corruption, and encourage education. He began the first successful French colonization of the Americas

France began colonizing America in the 16th century and continued into the following centuries as it established a colonial empire in the Western Hemisphere. France established colonies in much of eastern North America, on several Caribbean is ...

. He promoted trade and industry, and prioritized the construction of roads, bridges, and canals to facilitate communication within France and strengthen the country's cohesion. These efforts stimulated economic growth and improved living standards.

While the Edict of Nantes brought religious peace to France, some hardline Catholics and Huguenots remained dissatisfied, leading to occasional outbreaks of violence and conspiracies. Henry IV also faced resistance from certain noble factions who opposed his centralization policies, leading to political instability. His main foreign policy success was the Peace of Vervins in 1598, which made peace in the long-running conflict with Spain. He formed a strategic alliance with England. He also forged alliances with Protestant states, such as the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

and several German states, to counter the Catholic powers. His policies contributed to the stability and prominence of France in European affairs.

Early life

Henry was born on the night of 12-to-13 December 1553 at Pau, the capital of the joint

Henry was born on the night of 12-to-13 December 1553 at Pau, the capital of the joint Kingdom of Navarre

The Kingdom of Navarre ( ), originally the Kingdom of Pamplona, occupied lands on both sides of the western Pyrenees, with its northernmost areas originally reaching the Atlantic Ocean (Bay of Biscay), between present-day Spain and France.

The me ...

with the sovereign Principality of Béarn, in his maternal grandfather King Henry II of Navarre

Henry II (Spanish: ''Enrique II''; Basque: ''Henrike II''; 18 April 1503 – 25 May 1555), nicknamed ''Sangüesino'' because he was born in Sangüesa, was the King of Navarre from 1517. The kingdom had been reduced to a small territory north of t ...

's estate, the Château de Pau. He was the son of Jeanne III of Navarre (Jeanne d'Albret) and her husband, Antoine de Bourbon, Duke of Vendôme. As the heir to the throne of Navarre, Henry received the title of Prince of Viana (''Prince de Viane''). He was baptized in the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

a few weeks after his birth, on 6 March 1554, at the chapel of the Château de Pau, by Cardinal Georges d'Armagnac. His godfathers were kings Henry II of France

Henry II (; 31 March 1519 – 10 July 1559) was List of French monarchs#House of Valois-Angoulême (1515–1589), King of France from 1547 until his death in 1559. The second son of Francis I of France, Francis I and Claude of France, Claude, Du ...

and Henry II of Navarre, and his godmothers the Queen of France Catherine de' Medici

Catherine de' Medici (, ; , ; 13 April 1519 – 5 January 1589) was an Italian Republic of Florence, Florentine noblewoman of the Medici family and Queen of France from 1547 to 1559 by marriage to Henry II of France, King Henry II. Sh ...

and Isabella of Navarre, Viscountess of Rohan. During the ceremony, King Henry II of France was represented by the Cardinal de Vendôme.

Henry spent part of his early childhood in the countryside of Béarn at the Château de Coarraze. He frequented the peasants during his hunting trips, and acquired the nickname of "miller of Barbaste" (''meunier de Barbaste''). Faithful to the spirit of Calvinism

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyteri ...

, Henry's mother Jeanne d'Albret raised him in its strict morality, according to the precepts of the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

. On the accession of Charles IX of France

Charles IX (Charles Maximilien; 27 June 1550 – 30 May 1574) was List of French monarchs, King of France from 1560 until his death in 1574. He ascended the French throne upon the death of his brother Francis II of France, Francis II in 1560, an ...

in 1561, Henry was brought to live at the French court in Paris by his father Antoine de Bourbon. Henry's parents disagreed on the choice of his religion, with his mother seeking to educate him in Calvinism, and his father in Catholicism.

Wars of Religion

During the First French War of Religion (1562–1563), Henry was moved to Montargis for his safety, where he was placed under the protection of

During the First French War of Religion (1562–1563), Henry was moved to Montargis for his safety, where he was placed under the protection of Renée of France

Renée of France (25 October 1510 – 12 June 1574), was List of Ferrarese consorts, Duchess of Ferrara from 31 October 1534 until 3 October 1559 by marriage to Ercole II d'Este, grandson of Pope Alexander VI. She was the younger surviving ch ...

. After his father's death and the end of the war, he was kept at the French court as a guarantor of the agreement between the monarchy and the Queen of Navarre. Jeanne d'Albret obtained control of his education from Catherine de' Medici and his appointment as governor of Guyenne

Guyenne or Guienne ( , ; ) was an old French province which corresponded roughly to the Roman province of '' Aquitania Secunda'' and the Catholic archdiocese of Bordeaux.

Name

The name "Guyenne" comes from ''Aguyenne'', a popular transform ...

in 1563. Between 1564 and 1566, Henry accompanied the French royal family in its grand tour of France, and on this occasion reencountered his mother, whom he had not seen for two years. In 1567, Jeanne d'Albret brought him back to live with her in Béarn.

In 1568, Henry took part as an observer in his first military campaign in Navarre, and continued his military instruction during the Third War of Religion (1568–1570). Under the tutelage of Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

leader Gaspard II de Coligny, he witnessed the battles of Jarnac, La Roche-l'Abeille, and Moncontour. He saw combat for the first time in 1570, at the .

King of Navarre

First marriage and Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre

On 9 June 1572, at the death of his mother Queen Jeanne, the 19-year-old Henry becameKing of Navarre

This is a list of the kings and queens of kingdom of Pamplona, Pamplona, later kingdom of Navarre, Navarre. Pamplona was the primary name of the kingdom until its union with Kingdom of Aragon, Aragon (1076–1134). However, the territorial desig ...

. Upon his accession, it was arranged for Henry to marry Margaret of Valois

Margaret of Valois (, 14 May 1553 – 27 March 1615), popularly known as , was List of Navarrese royal consorts, Queen of Navarre from 1572 to 1599 and Queen of France from 1589 to 1599 as the consort of Henry IV of France and III of Navarre.

Ma ...

, daughter of Henry II of France and Catherine de' Medici. The wedding took place in Paris on 18 August 1572 on the parvis

A parvis or parvise is the open space in front of and around a cathedral or Church (building) , church, especially when surrounded by either colonnades or porticoes, as at St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. It is thus a church-specific type of forec ...

of Notre Dame Cathedral

Notre-Dame de Paris ( ; meaning "Cathedral of Our Lady of Paris"), often referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the River Seine), in the 4th arrondissement of Paris, France. It ...

.

On 24 August, the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre began in Paris. Several thousand Protestants who had come to Paris for Henry's wedding were killed, as well as thousands more throughout the country in the days that followed. Henry narrowly escaped death thanks to the help of his wife and his promise to convert to Catholicism. He was forced to live at the court of France, but he escaped in early 1576. On 5 February of that year, he formally abjured Catholicism at Tours

Tours ( ; ) is the largest city in the region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Indre-et-Loire. The Communes of France, commune of Tours had 136,463 inhabita ...

and rejoined the Protestant forces in the military conflict. He named his 16-year-old sister, Catherine de Bourbon, regent of Béarn. Catherine held the regency for nearly thirty years.

Henry became heir presumptive

An heir presumptive is the person entitled to inherit a throne, peerage, or other hereditary honour, but whose position can be displaced by the birth of a person with a better claim to the position in question. This is in contrast to an heir app ...

to the French throne in 1584 upon the death of Francis, Duke of Anjou

''Monsieur'' François, Duke of Anjou and Alençon (; 18 March 1555 – 10 June 1584) was the youngest son of King Henry II of France and Catherine de' Medici.

Early years

He was scarred by smallpox at age eight, and his pitted face and s ...

, brother and heir to the Catholic Henry III, who had succeeded Charles IX in 1574. Given that Henry of Navarre was the next senior agnatic

Patrilineality, also known as the male line, the spear side or agnatic kinship, is a common kinship system in which an individual's family membership derives from and is recorded through their father's lineage. It generally involves the inheritanc ...

descendant of King Louis IX, King Henry III had no choice but to recognise him as the legitimate successor.

War of the Three Henrys (1587–1589)

A conflict for the throne of France then ensued, contested by these three men and their respective supporters: * KingHenry III of France

Henry III (; ; ; 19 September 1551 – 2 August 1589) was King of France from 1574 until his assassination in 1589, as well as King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1573 to 1575.

As the fourth son of King Henry II of France, he ...

, supported by the royalists and the politiques;

* King Henry of Navarre, heir presumptive to the French throne and leader of the Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

s, supported by Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

and the Protestant princes of Germany; and

* Henry I of Lorraine, Duke of Guise, leader of the Catholic League, funded and supported by Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

.

Salic law

The Salic law ( or ; ), also called the was the ancient Frankish Civil law (legal system), civil law code compiled around AD 500 by Clovis I, Clovis, the first Frankish King. The name may refer to the Salii, or "Salian Franks", but this is deba ...

barred inheritance by the king's sisters and all others who could claim descent through only the female line. However, since Henry of Navarre was a Huguenot, many Catholics refused to acknowledge the succession, and France was plunged into a phase of the Wars of Religion known as the War of the Three Henrys (1587–1589).

The Duke of Guise pushed for complete suppression of the Huguenots and had much support among Catholic loyalists. Political disagreements among the parties set off a series of campaigns and counter-campaigns that culminated in the Battle of Coutras.

In December 1588, King Henry III had the Duke of Guise murdered, along with his brother Louis, Cardinal of Guise, thinking the removal of the brothers would restore his authority. However, the populace was horrified and rose against him. The King was no longer recognized in several cities; his effective power was limited to Blois

Blois ( ; ) is a commune and the capital city of Loir-et-Cher Departments of France, department, in Centre-Val de Loire, France, on the banks of the lower Loire river between Orléans and Tours.

With 45,898 inhabitants by 2019, Blois is the mos ...

, Tours, and the surrounding districts.

In the general chaos, Henry III relied on Henry of Navarre and his Huguenots. The two kings were united by a common interest—to win France from the Catholic League. Henry III recognized the King of Navarre as a true subject and Frenchman, not a fanatic Huguenot aiming to subjugate Catholics, and Catholic royalist nobles also rallied to them. With this combined force, the two kings marched to Paris. The morale of the city was low, and even the Spanish ambassador believed the city could not hold out longer than a fortnight. However, on 2 August 1589, a monk infiltrated Henry III's camp and assassinated him.

King of France: Early reign

Succession (1589–1594)

When Henry III died, his ninth cousin once removed, Henry of Navarre, nominally became king of France. The Catholic League, however, strengthened by foreign support—especially from Spain—was strong enough to prevent a universal recognition of his new title.Pope Sixtus V

Pope Sixtus V (; 13 December 1521 – 27 August 1590), born Felice Piergentile, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 April 1585 to his death, in August 1590. As a youth, he joined the Franciscan order, where h ...

excommunicated Henry and declared him ineligible to inherit the crown. Most of the Catholic nobles who had joined Henry III for the siege of Paris also refused to recognize Henry of Navarre, and abandoned him. He set about winning his kingdom by force of arms, aided by English money and German troops. Henry's Catholic uncle Charles, Cardinal de Bourbon was proclaimed king by the League, but the Cardinal was Henry's prisoner at the time. Henry was victorious at the Battle of Arques and the Battle of Ivry

The Battle of Ivry was fought on 14 March 1590, during the French Wars of Religion. The battle was a decisive victory for Henry IV of France, leading French royal and English forces against the Catholic League by the Duc de Mayenne and Spani ...

, but failed to take Paris after besieging it in 1590.

When Cardinal de Bourbon died in 1590, the League could not agree on a new candidate at the Estates General called to settle the question, also attended by the envoys of Spain. While some supported various Guise candidates, the strongest candidate was probably the

When Cardinal de Bourbon died in 1590, the League could not agree on a new candidate at the Estates General called to settle the question, also attended by the envoys of Spain. While some supported various Guise candidates, the strongest candidate was probably the Infanta Isabella Clara Eugenia of Spain

Isabella Clara Eugenia (; 12 August 1566 – 1 December 1633), sometimes referred to as Clara Isabella Eugenia, was sovereign of the Spanish Netherlands, which comprised the Low Countries and the north of modern France, with her husband Archd ...

, daughter of Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

, whose mother Elisabeth had been the eldest daughter of Henry II of France

Henry II (; 31 March 1519 – 10 July 1559) was List of French monarchs#House of Valois-Angoulême (1515–1589), King of France from 1547 until his death in 1559. The second son of Francis I of France, Francis I and Claude of France, Claude, Du ...

. In the religious fervor of the time, the Infanta was considered a suitable queen, provided she married a suitable husband. The French overwhelmingly rejected Philip's first choice, Archduke Ernest of Austria

Archduke Ernest of Austria (; 15 June 1553 – 20 February 1595) was an Austrian prince, the son of Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor, and Maria of Spain.

Biography

Born in Vienna, he was educated with his brother Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emp ...

, the Emperor's brother, also a member of the House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful Dynasty, dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout ...

. In case of such opposition, Philip indicated that princes of the House of Lorraine would be acceptable to him: the Duke of Guise; a son of the Duke of Lorraine; and the son of the Duke of Mayenne. The Spanish ambassadors selected the Duke of Guise, to the joy of the League. However, at that moment of seeming victory, the envy of the Duke of Mayenne was aroused, and he blocked the proposed election of a king.

The

The Parlement

Under the French Ancien Régime, a ''parlement'' () was a provincial appellate court of the Kingdom of France. In 1789, France had 13 ''parlements'', the original and most important of which was the ''Parlement'' of Paris. Though both th ...

of Paris also upheld the Salic law. They argued that if the French accepted natural hereditary succession, as proposed by the Spaniards, and accepted a woman as their queen, then the ancient claims of the English kings would be confirmed, and the monarchy of centuries past would be rendered illegal. The Parlement admonished Mayenne, as lieutenant-general, that the kings of France had resisted the interference of the pope in political matters, and that he should not raise a foreign prince or princess to the throne of France under the pretext of religion. Mayenne was angered that he had not been consulted prior to this admonishment, but yielded, since their aim was not contrary to his present views. Despite these setbacks for the League, Henry remained unable to take control of Paris.

Conversion to Catholicism: "Paris is well worth a Mass" (1593)

On 25 July 1593, with the encouragement of his mistress, , Henry permanently renounced Protestantism and converted to Catholicism to secure his hold on the French crown, thereby earning the resentment of the

On 25 July 1593, with the encouragement of his mistress, , Henry permanently renounced Protestantism and converted to Catholicism to secure his hold on the French crown, thereby earning the resentment of the Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

and his ally Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

. He was said to have declared that ("Paris is well worth a Mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

"),Alistair Horne, ''Seven Ages of Paris'', Random House (2004)F.P.G. Guizot (1787–1874) ''A Popular History of France...''gutenberg.org

/ref> although the attribution is doubtful. His acceptance of Catholicism secured the allegiance of the vast majority of his subjects.

Coronation and recognition (1594–1595)

Reims

Reims ( ; ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French Departments of France, department of Marne (department), Marne, and the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, 12th most populous city in Fran ...

, traditional coronation place of French kings, was still occupied by the Catholic League, and thus Henry was crowned King of France at the Cathedral of Chartres on 27 February 1594. Pope Clement VIII

Pope Clement VIII (; ; 24 February 1536 – 3 March 1605), born Ippolito Aldobrandini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 30 January 1592 to his death in March 1605.

Born in Fano, Papal States to a prominen ...

lifted excommunication from Henry on 17 September 1595. He did not forget his former Calvinist coreligionists, however, and was known for his religious tolerance. In 1598 he issued the Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was an edict signed in April 1598 by Henry IV of France, King Henry IV and granted the minority Calvinism, Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was predominantl ...

, which granted circumscribed liberties to the Huguenots.

Civil war and the Edict of Nantes

Henry IV successfully ended the civil wars. He and his ministers appeased Catholic leaders using bribes of about 7 million écus, a sum greater than France's annual revenue. In combination with other fiscal problems, the king was faced with a financial crisis by the middle of the 1590s. In response to this crisis, Henry resolved to convene an Assembly of Notables in November 1596 that he hoped would approve the creation of new royal revenues. The assembly approved the creation of a new tax on goods entering towns that would be known as the ''pancarte'', however in 1597 the crown was again rocked by military crisis when the Spanish seized Amiens.

Huguenot leaders were placated by the

Henry IV successfully ended the civil wars. He and his ministers appeased Catholic leaders using bribes of about 7 million écus, a sum greater than France's annual revenue. In combination with other fiscal problems, the king was faced with a financial crisis by the middle of the 1590s. In response to this crisis, Henry resolved to convene an Assembly of Notables in November 1596 that he hoped would approve the creation of new royal revenues. The assembly approved the creation of a new tax on goods entering towns that would be known as the ''pancarte'', however in 1597 the crown was again rocked by military crisis when the Spanish seized Amiens.

Huguenot leaders were placated by the Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was an edict signed in April 1598 by Henry IV of France, King Henry IV and granted the minority Calvinism, Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was predominantl ...

, which had four separate sections. The articles laid down the tolerance which would be accorded to the Huguenots including the exact places where worship may or may not take place, the recognition of three Protestant universities, and the allowance of Protestant synods. The king also issued two personal documents (called ''brevets'') which recognized the Protestant establishment. The Edict of Nantes signed religious tolerance into law, and the brevets were an act of benevolence that created a Protestant state within France.

Despite this, it would take years to restore law and order to France. The Edict was met by opposition from the ''parlements'', which objected to the guarantees offered to Protestants. The Parlement de Rouen did not formally register the edict until 1609, although it begrudgingly observed its terms.

Later reign

Domestic policies

During his reign, Henry IV worked through the minister Maximilien de Béthune, Duke of Sully, to regularize state finance, promote agriculture, drain swamps, undertake public works, and encourage education. He established the ''Collège Royal Henri-le-Grand'' in La Flèche (today the Prytanée Militaire de la Flèche). He and Sully protected forests from further devastation, built a system of tree-lined highways, and constructed bridges and canals. He had a 1200-metre canal built in the park at the Château Fontainebleau (which may be fished today) and ordered the planting of pines, elms, and fruit trees. The King restored Paris as a great city, with the Pont Neuf, which still stands today, constructed over the riverSeine

The Seine ( , ) is a river in northern France. Its drainage basin is in the Paris Basin (a geological relative lowland) covering most of northern France. It rises at Source-Seine, northwest of Dijon in northeastern France in the Langres plat ...

to connect the Right

Rights are law, legal, social, or ethics, ethical principles of freedom or Entitlement (fair division), entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal sy ...

and Left Bank

In geography, a bank is the land alongside a body of water.

Different structures are referred to as ''banks'' in different fields of geography.

In limnology (the study of inland waters), a stream bank or river bank is the terrain alongsid ...

s of the city. Henry IV also built the ''Place Royale'' (known since 1800 as Place des Vosges), and added the ''Grande Galerie'' to the Louvre Palace

The Louvre Palace (, ), often referred to simply as the Louvre, is an iconic French palace located on the Right Bank of the Seine in Paris, occupying a vast expanse of land between the Tuileries Gardens and the church of Saint-Germain l'Auxe ...

. Stretching more than 400 metres along the Seine river bank, at the time it was the longest edifice of its kind in the world. He promoted the arts among all classes of people, and invited hundreds of artists and craftsmen to live and work on the building's lower floors. This tradition continued for another two hundred years, until ended by Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

. The art and architecture of his reign have become known as the Henry IV style.

Economically, Henry IV sought to reduce imports of foreign goods to support domestic manufacturing. To this end, new sumptuary laws limited the use of imported gold and silver cloth. He also built royal factories to produce luxuries such as crystal glass, silk, satin, and tapestries (at Gobelins Manufactory and Savonnerie manufactory workshops). The king re-established silk weaving in Tours and Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

, and increased linen

Linen () is a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant.

Linen is very strong and absorbent, and it dries faster than cotton. Because of these properties, linen is comfortable to wear in hot weather and is valued for use in garments. Lin ...

production in Picardy

Picardy (; Picard language, Picard and , , ) is a historical and cultural territory and a former regions of France, administrative region located in northern France. The first mentions of this province date back to the Middle Ages: it gained it ...

and Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

. He had distributed 16,000 free copies of the practical manual ''The Theatre of Agriculture'' by Olivier de Serres.

King Henry's vision extended beyond France, and he financed several expeditions of Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; 13 August 1574#Fichier]For a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see #Ritch, RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December ...

and Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Monts, to North America. France laid claim to New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

(now Canada).

International relations

During the reign of Henry IV, rivalry continued among France,Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

for the mastery of Western Europe. The conflict was not resolved until after the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

.

Spain and Italy

During Henry's struggle for the crown, Spain had been the principal backer of the Catholic League, and it tried to thwart Henry. Under the Duke of Parma, an army from theSpanish Netherlands

The Spanish Netherlands (; ; ; ) (historically in Spanish: , the name "Flanders" was used as a '' pars pro toto'') was the Habsburg Netherlands ruled by the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs from 1556 to 1714. They were a collection of States of t ...

intervened in 1590 against Henry and foiled his siege of Paris. Another Spanish army helped the Catholic League nobles opposing Henry to win the Battle of Craon

The battle of Craon took place during the Brittany campaign of the French Wars of Religion in Craon, Mayenne between 21–24 May 1592. It was fought between a Kingdom of France, French Crown army under Henri de Bourbon, Duke of Montpensier and Fr ...

in 1592. The Spanish war was not ended with Henry's coronation, but after his victory at the Siege of Amiens in September 1597, the Peace of Vervins was signed in 1598. This freed his armies to settle the dispute with the Duchy of Savoy

The Duchy of Savoy (; ) was a territorial entity of the Savoyard state that existed from 1416 until 1847 and was a possession of the House of Savoy.

It was created when Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, raised the County of Savoy into a duchy f ...

, ending with the Treaty of Lyon of 1601, which arranged territorial exchanges.

One of Henry's major problems was the Spanish Road

The Spanish Road was a military road and trade route linking Spanish territories in Flanders with those in Italy. It was in use from approximately 1567 to 1648.

The Road was created to support the Spanish war effort in the Eighty Years' War ag ...

which traversed Spanish territory through Savoy

Savoy (; ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps. Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south and west and to the Aosta Vall ...

to the Low Countries. His first opportunity to cut the Spanish Road was a dispute over the ownership of the Marquisate of Saluzzo. The last marquis left Saluzzo to the French crown in 1548 (when Savoy was occupied by France), but the territory became disputed during the chaos of the Wars of Religion. The pope was asked to arbitrate between the claims of France and the Duke of Savoy. The Duke offered to cede Bresse to France if he could retain Saluzzo. Henri IV accepted this, but Spain objected that Bresse was a vital part of the Spanish Road, and persuaded the Duke to reject the decision. Henry IV was already at Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

and had soldiers ready, and four days later he marched fifty thousand men against the duchy, occupying almost all of its area west of the Alps. In January 1601, Henry accepted another offer of papal arbitration and gained not only Bresse, but Bugey The Bugey (, ; Arpitan: ''Bugê'') is a historical region in the department of Ain, eastern France, located between Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saôn ...

and Gex. Savoy retained a narrow corridor through the Val de Chézery. This still allowed Spanish troops to cross from Lombardy

The Lombardy Region (; ) is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in northern Italy and has a population of about 10 million people, constituting more than one-sixth of Italy's population. Lombardy is ...

to Franche Comté without going through France, but it created a choke point where the Spanish Road was a single bridge across the Rhône River.

The Saluzzo conflict was Henry IV's last major military operation, but he continued to finance Spain's enemies. He generously assisted the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

with over 12 million livres between 1598 and 1610. In some years, the payment was 10% of France's total annual budget. France also sent subsidies to Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

after the Duke of Savoy attempted to capture the city in 1602.

Holy Roman Empire

In 1609, the death of the childless Johann William, Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg, meant that the succession of the wealthy Duchies was in dispute. Henry aimed to maintain peace among the Protestant princes of the Holy Roman Empire to present a united front against the Habsburgs. To achieve this, Henry encouraged a peaceful settlement over the succession between the two main Protestant claimants: Wolfgang Wilhelm of Palatinate-Neuburg and Johann Sigismund of Brandenburg. He communicated this withMaurice, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel

Maurice of Hesse-Kassel (; 25 May 1572 – 15 March 1632), also called Maurice the Learned or Moritz, was the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel (or Hesse-Cassel) in the Holy Roman Empire from 1592 to 1627.

Life

Maurice was born in Kassel as the son o ...

, a significant Protestant leader, who then sought to facilitate an agreement between Wolfgang and Johann Sigismund. When peace was negotiated in the Treaty of Dortmund, Henry sent congratulatory messages to the Protestant claimants, and voiced his support, particularly against the Habsburgs who were likely to challenge the treaty.

When Habsburg forces invaded Jülich, starting the War of the Jülich Succession

The War of the Jülich Succession, also known as the Jülich War or the Jülich-Cleves Succession Crises (German language, German: ''Jülich-Klevischer Erbfolgestreit''), was a war of succession in the United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg. The fi ...

, Henry decided to act. On 29 July, after consulting his advisors, Henry ordered a French army to support the Protestant claimants. Maximilien de Béthune, Duke of Sully, his financial advisor, was particularly keen on joining the war, as France's finances at the time were secure. Henry declared that he was defending the rights of the Imperial princes, and also that he was honoring his previously agreements to defend the Protestant claimants. Henry also was seeking to curb the power of the Habsburgs.

Henry's actions faced critique. Some saw him as a warmonger. The Papacy

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

in particular was concerned that Henry was supporting Protestant princes. Henry responded to the papacy declaring that he was keeping the peace. When Habsburg ambassadors told Henry that he was contributing to the decline of Catholicism by supporting the Protestant claimants, Henry declared that he was merely trying to contain the Habsburgs. He also warned the Papacy to keep religion out of succession affairs. France assured the Protestant princes of the Empire that despite being Catholic, the French would still provide aid. Henry also sought to gain the aid of the English and Dutch. Henry greatly pressured the Dutch for support, appealing directly to states-general.

Despite Henry's defense of the Protestant princes during the Jülich War, many of the German states distrusted him. Afterall, Henry had converted to Catholicism in 1593. Also, France owed debts to some German states, which France struggled to repay. There were also concerns that Henry sought to become Emperor. It was widely believed that in 1610 Henry was preparing to escalate the war against the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

, which was prevented by his assassination and the subsequent rapprochement with Spain under the regency of Marie de' Medici

Marie de' Medici (; ; 26 April 1575 – 3 July 1642) was Queen of France and Navarre as the second wife of King Henry IV. Marie served as regent of France between 1610 and 1617 during the minority of her son Louis XIII. Her mandate as rege ...

.

Ottoman Empire

Even before Henry's accession to the French throne, the French Huguenots were in contact with Aragonese

Even before Henry's accession to the French throne, the French Huguenots were in contact with Aragonese Moriscos

''Moriscos'' (, ; ; " Moorish") were former Muslims and their descendants whom the Catholic Church and Habsburg Spain commanded to forcibly convert to Christianity or face compulsory exile after Spain outlawed Islam. Spain had a sizeable M ...

in plans against the Habsburg government of Spain in the 1570s. Around 1575, plans were made for a combined attack of Aragonese Moriscos and Huguenots from Béarn

Béarn (; ; or ''Biarn''; or ''Biarno''; or ''Bearnia'') is one of the traditional provinces of France, located in the Pyrenees mountains and in the plain at their feet, in Southwestern France. Along with the three Northern Basque Country, ...

under Henry against Spanish Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and ; ) is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces of Spain, ...

, in agreement with the Dey of Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, but this project floundered with the arrival of John of Austria

John of Austria (, ; 24 February 1547 – 1 October 1578) was the illegitimate son of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. Charles V recognized him in a codicil to his will. John became a military leader in the service of his half-brother, King Phi ...

in Aragon and the disarmament of the Moriscos. In 1576, a three-pronged Ottoman fleet from Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

was planned to disembark between Murcia

Murcia ( , , ) is a city in south-eastern Spain, the Capital (political), capital and most populous city of the autonomous community of the Region of Murcia, and the Ranked lists of Spanish municipalities#By population, seventh largest city i ...

and Valencia

Valencia ( , ), formally València (), is the capital of the Province of Valencia, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, the same name in Spain. It is located on the banks of the Turia (r ...

while the French Huguenots would invade from the north and the Moriscos accomplish their uprising, but the fleet failed to arrive.

After his crowning, Henry continued the policy of a Franco-Ottoman alliance

The Franco-Ottoman alliance, also known as the Franco-Turkish alliance, was an alliance established in 1536 between Francis I of France, Francis I, King of France and Suleiman the Magnificent, Suleiman I of the Ottoman Empire. The strategic and s ...

and received an embassy from Sultan Mehmed III

Mehmed III (, ''Meḥmed-i sālis''; ; 26 May 1566 – 22 December 1603) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1595 until his death in 1603. Mehmed was known for ordering the execution of his brothers and leading the army in the Long Turkish ...

in 1601. In 1604, a "Peace Treaty and Capitulation" was signed between Henry IV and the Ottoman Sultan Ahmed I

Ahmed I ( '; ; 18 April 1590 – 22 November 1617) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1603 to 1617. Ahmed's reign is noteworthy for marking the first breach in the Ottoman tradition of royal fratricide; henceforth, Ottoman rulers would no ...

, granting France numerous advantages in the Ottoman Empire. In 1606–07, Henry IV sent Arnoult de Lisle as Ambassador to Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

to request the observance of past friendship treaties. An embassy was sent to Ottoman Tunisia

Ottoman Tunisia, also known as the Regency of Tunis, refers to a territory of Ottoman Empire that existed from the 16th to 19th century in what is largely modern-day Tunisia.

During the period of Ottoman Rule, Tunis was administratively inte ...

in 1608 led by François Savary de Brèves.

East Asia

Under Henry IV, various enterprises were set up to develop long-distance trade. In December 1600, a company was formed through the association ofSaint-Malo

Saint-Malo (, , ; Gallo language, Gallo: ; ) is a historic French port in Ille-et-Vilaine, Brittany (administrative region), Brittany.

The Fortification, walled city on the English Channel coast had a long history of piracy, earning much wealth ...

, Laval, and Vitré to trade with the Moluccas

The Maluku Islands ( ; , ) or the Moluccas ( ; ) are an archipelago in the eastern part of Indonesia. Tectonically they are located on the Halmahera Plate within the Molucca Sea Collision Zone. Geographically they are located in West Melanesi ...

and Japan.''Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume III: A Century of Advance. Book 1'', Donald F. Lach pp. 93–9/ref> Two ships, the ''Croissant'' and the ''Corbin'', were sent around the

Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

in May 1601. The ''Corbin'' was wrecked in the Maldives

The Maldives, officially the Republic of Maldives, and historically known as the Maldive Islands, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in South Asia located in the Indian Ocean. The Maldives is southwest of Sri Lanka and India, abou ...

, leading to the adventure of François Pyrard de Laval, who managed to return to France in 1611. The ''Croissant'', carrying François Martin de Vitré, reached Ceylon

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

and traded with Aceh

Aceh ( , ; , Jawi script, Jawoë: ; Van Ophuijsen Spelling System, Old Spelling: ''Atjeh'') is the westernmost Provinces of Indonesia, province of Indonesia. It is located on the northern end of Sumatra island, with Banda Aceh being its capit ...

in Sumatra

Sumatra () is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the list of islands by area, sixth-largest island in the world at 482,286.55 km2 (182,812 mi. ...

, but was captured by the Dutch on the return leg at Cape Finisterre. François Martin de Vitré was the first Frenchman to write an account of travels to the Far East in 1604, at the request of Henry IV.

From 1604 to 1609, following the return of François Martin de Vitré, Henry attempted to set up a French East India Company on the model of England and the Netherlands. On 1 June 1604, he issued letters patent to Dieppe

Dieppe (; ; or Old Norse ) is a coastal commune in the Seine-Maritime department, Normandy, northern France.

Dieppe is a seaport on the English Channel at the mouth of the river Arques. A regular ferry service runs to Newhaven in England ...

merchants to form the first French East Indies Company, giving them exclusive rights to Asian trade for 15 years, but no ships were sent until 1616. In 1609, another adventurer, Pierre-Olivier Malherbe, returned from a circumnavigation of the globe and informed Henry of his adventures. He had visited China and India, and met with Emperor Akbar

Akbar (Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar, – ), popularly known as Akbar the Great, was the third Mughal emperor, who reigned from 1556 to 1605. Akbar succeeded his father, Humayun, under a regent, Bairam Khan, who helped the young emperor expa ...

.

Religion

Historians have assessed that Henry IV was a convincedCalvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

, and only changed his formal religious confession to achieve his political goals. Henry IV was baptized as a Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

on 5 January 1554. He was raised in the Reformed Tradition by his mother Jeanne III of Navarre. In 1572, after the massacre of French Calvinists, he was forced by Catherine de' Medici

Catherine de' Medici (, ; , ; 13 April 1519 – 5 January 1589) was an Italian Republic of Florence, Florentine noblewoman of the Medici family and Queen of France from 1547 to 1559 by marriage to Henry II of France, King Henry II. Sh ...

and the royal court to convert. In 1576, after escaping from Paris, he abjured Catholicism and returned to Calvinism. In 1593, to gain recognition as King of France

France was ruled by monarchs from the establishment of the kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I, king of the Fra ...

, he converted again to Catholicism. Although a formal Catholic, he valued his Calvinist upbringing and was tolerant toward the Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

until his death in 1610, and issued the Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was an edict signed in April 1598 by Henry IV of France, King Henry IV and granted the minority Calvinism, Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was predominantl ...

which granted them many concessions.

Nicknames

Henry was nicknamed ''Henri'' ''le Grand'' (the Great), and in France is also called ''le bon roi Henri'' (good king Henry) and ''le vert galant'' (The Green Gallant) for his numerous mistresses. In English he is most often referred to as Henry of Navarre.Relationship with Charlotte Marguerite de Montmorency

In 1609, Henry had grown infatuated with Charlotte Marguerite de Montmorency, Princess of Condé, much to the chagrin of her husband, Henry II, Prince of Condé. On 28 November 1609, the Prince and Princess fled toBrussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

in the Spanish Netherlands

The Spanish Netherlands (; ; ; ) (historically in Spanish: , the name "Flanders" was used as a '' pars pro toto'') was the Habsburg Netherlands ruled by the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs from 1556 to 1714. They were a collection of States of t ...

. King Henry was furious, and believed that the Prince was conspiring against him, so he threatened to raise an army of 60,000 to capture him and bring back the princess. This corresponded with the War of the Jülich Succession, so it added to the tension, especially with Spain.

Assassination

Though generally well-liked, Henry was considered a heretical usurper by some Catholics and a traitor to their faith by some Protestants. Henry was the target of at least 12 assassination attempts, including byPierre Barrière

Pierre Barrière (born?, died August 31, 1593) was a would-be assassin of King Henry IV of France.

Barrière attempted an assassination of Henry IV on 27 August 1593. His assassination attempt failed when he was denounced by a Dominican priest t ...

in August 1593, and by Jean Châtel in December 1594.

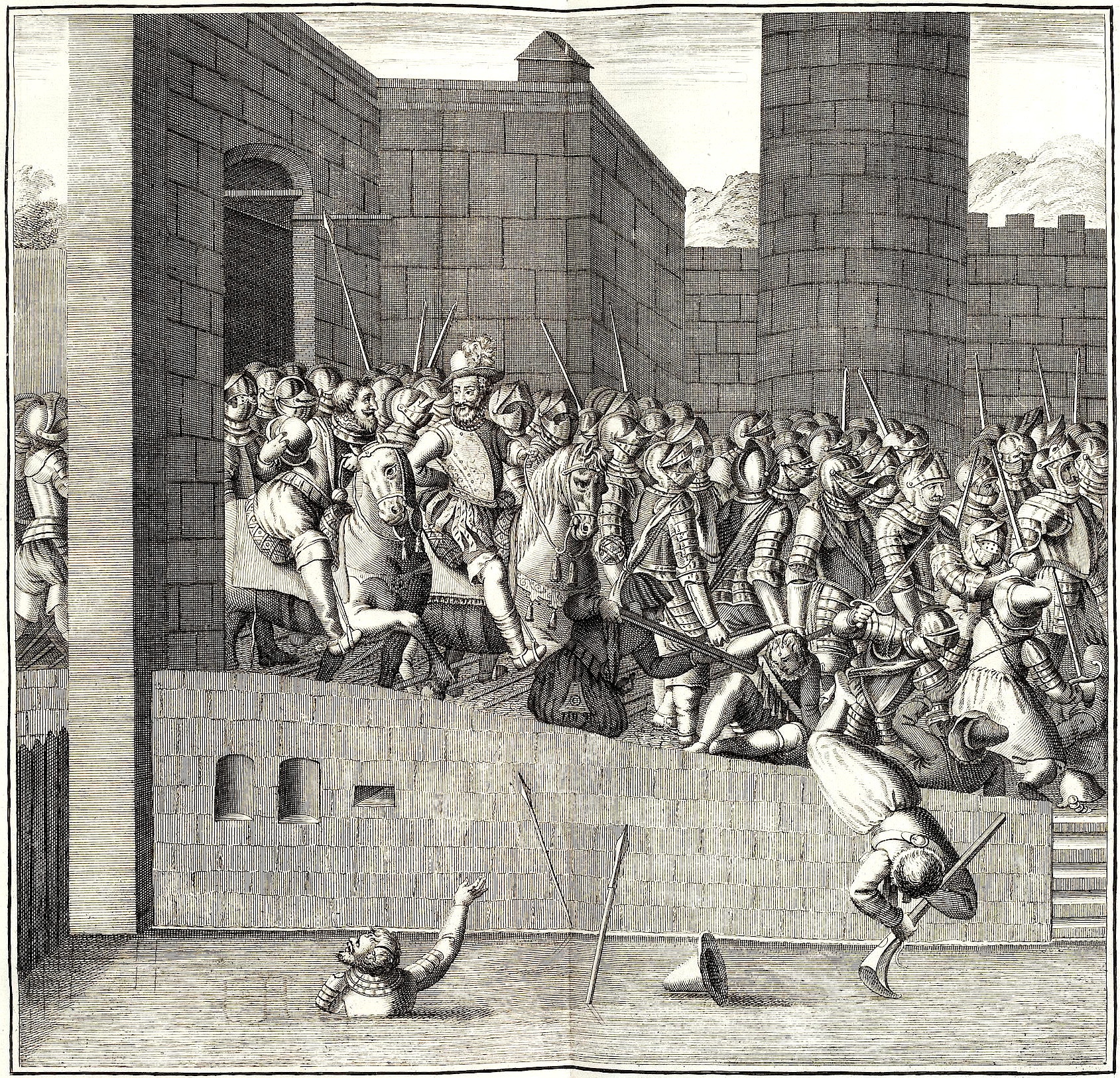

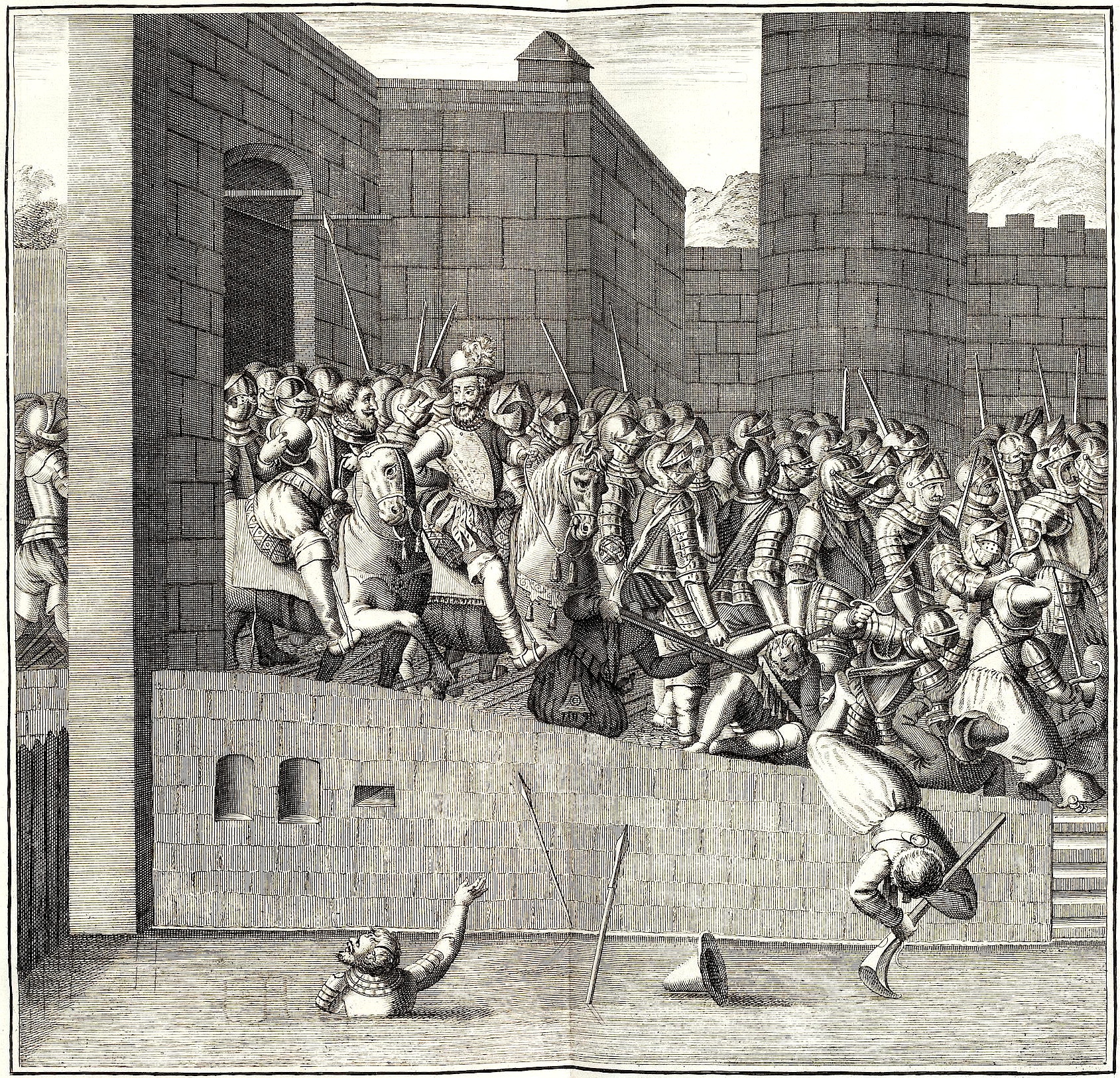

Henry was killed in Paris on 14 May 1610 by François Ravaillac, a Catholic zealot who stabbed him while his coach was stopped on Rue de la Ferronnerie. The carriage was stopped by traffic congestion associated with the Queen's coronation ceremony, as depicted in the engraving by Gaspar Bouttats. Hercule de Rohan, riding in the coach with the king, was wounded in the attack but survived. Ravaillac was immediately seized, and executed days later. Henry was buried at the Saint Denis Basilica. His widow, Marie de' Medici

Marie de' Medici (; ; 26 April 1575 – 3 July 1642) was Queen of France and Navarre as the second wife of King Henry IV. Marie served as regent of France between 1610 and 1617 during the minority of her son Louis XIII. Her mandate as rege ...

, served as regent for their nine-year-old son, Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown.

...

, until 1617.

engraving by Gaspar Bouttats File:François Ravaillac.jpg, His assassin, François Ravaillac, brandishing his dagger File:Pierre Firens - Le Roi Est Mort continues at the Palace of Versailles - 1610.jpg, Pierre Firens - "Le Roi Est Mort continues at the Palace of Versailles". 1610 File:Henry IV of France as he lay in state after his murder in the year 1610, engraving after Quesnel - Gallica 2010 (adjusted).jpg, Lying in state at the

Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is a national art museum in Paris, France, and one of the most famous museums in the world. It is located on the Rive Droite, Right Bank of the Seine in the city's 1st arrondissement of Paris, 1st arron ...

, engraving after François Quesnel

Legacy

In 1614, four years after Henry IV's death, his

In 1614, four years after Henry IV's death, his statue

A statue is a free-standing sculpture in which the realistic, full-length figures of persons or animals are carved or Casting (metalworking), cast in a durable material such as wood, metal or stone. Typical statues are life-sized or close to ...

was erected on the Pont Neuf. During the early phase of the French Revolution, when it aimed to create a constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

rather than a republic, Henry IV was held up as a model for King Louis XVI

Louis XVI (Louis-Auguste; ; 23 August 1754 – 21 January 1793) was the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. The son of Louis, Dauphin of France (1729–1765), Louis, Dauphin of France (son and heir- ...

. When the Revolution radicalized and came to reject monarchy altogether, Henry IV's statue was torn down along with other royal monuments. It was nevertheless the first to be rebuilt, in 1818, and it still stands on the Pont Neuf today.

Henry IV was much lauded during the Bourbon Restoration (1814–30), as the restored dynasty was keen to play down the controversial reigns of Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached maturity (then defi ...

and Louis XVI

Louis XVI (Louis-Auguste; ; 23 August 1754 – 21 January 1793) was the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. The son of Louis, Dauphin of France (1729–1765), Louis, Dauphin of France (son and heir- ...

in favor of Good King Henry. The song Marche Henri IV (Long Live Henry IV) was popular. After the assassination in 1820 of the dauphin Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry, by a Republican fanatic, his widow Princess Caroline gave birth seven months later to their son, heir to the throne of France, and conspicuously named him ''Henri'' after his royal forefather.

The boy was baptised with Jurançon wine and garlic in the tradition of Béarn and Navarre, as Henry IV had been baptised in Pau. Henry serves as a loose inspiration for the character Ferdinand, King of Navarre, in William Shakespeare's 1590s play ''Love's Labour's Lost

''Love's Labour's Lost'' is one of William Shakespeare's early comedies, believed to have been written in the mid-1590s for a performance at the Inns of Court before Queen Elizabeth I. It follows the King of Navarre and his three companions as ...

''.

A 1661 biography, ''Histoire du Roy Henry le Grand,'' was written by Hardouin de Péréfixe de Beaumont for the edification of Henry's grandson Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

. A 1663 English translation was published for another grandson, King Charles II of England

Charles II (29 May 1630 – 6 February 1685) was King of Scotland from 1649 until 1651 and King of England, Scotland, and King of Ireland, Ireland from the 1660 Restoration of the monarchy until his death in 1685.

Charles II was the eldest su ...

. On 14 September 1788, when anti-tax riots broke out during the incipient French Revolution, rioters stopped travellers and demanded they dismount to salute Henry IV's statue. Henry's minister Sully published his ''Royal Economies'' in 1611 after de Sully's fall from power, but subsequent research has shown that it exaggerates the economic accomplishments of Sully's ministry. Many of the official source documents were altered, or even forged to make them more impressive.

Genealogy

Ancestry

Marriages and legitimate children

On 18 August 1572, Henry married his second cousinMargaret of Valois

Margaret of Valois (, 14 May 1553 – 27 March 1615), popularly known as , was List of Navarrese royal consorts, Queen of Navarre from 1572 to 1599 and Queen of France from 1589 to 1599 as the consort of Henry IV of France and III of Navarre.

Ma ...

. The marriage was not a happy one, and the couple was childless. Henry and Margaret separated even before Henry acceded to the throne in August 1589; Margaret retired to the Château d'Usson in the Auvergne and lived there for many years. After Henry became king of France, it was of the utmost importance that he provide an heir to the crown to avoid the problem of a disputed succession.

Henry favoured the idea of obtaining an annulment of his marriage to Margaret and marrying his mistress Gabrielle d'Estrées, who had already borne him three children. Henry's councillors strongly opposed this idea, but the matter was resolved unexpectedly by Gabrielle's sudden death in the early hours of 10 April 1599, after she had given birth to a premature stillborn son. His marriage to Margaret was annulled in 1599. On 17 December 1600, Henry married Marie de' Medici

Marie de' Medici (; ; 26 April 1575 – 3 July 1642) was Queen of France and Navarre as the second wife of King Henry IV. Marie served as regent of France between 1610 and 1617 during the minority of her son Louis XIII. Her mandate as rege ...

, daughter of Francesco I de' Medici

Francesco I (25 March 1541 – 19 October 1587) was the second Grand Duke of Tuscany, ruling from 1574 until his death in 1587. He was a member of the House of Medici.

Biography

Born in Florence, Francesco was the son of Cosimo I de' Medi ...

, Grand Duke of Tuscany

Grand may refer to:

People with the name

* Grand (surname)

* Grand L. Bush (born 1955), American actor

Places

* Grand, Oklahoma, USA

* Grand, Vosges, village and commune in France with Gallo-Roman amphitheatre

* Grand County (disambiguation), se ...

, and Archduchess Joanna of Austria.

For the royal entry

The ceremonies and festivities accompanying a formal entry by a ruler or their representative into a city in the Middle Ages and early modern period in Europe were known as the royal entry, triumphal entry, or Joyous Entry. The entry centred on ...

of Marie into Avignon

Avignon (, , ; or , ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the Communes of France, commune had a ...

on 19 November 1600, the citizens bestowed on Henry the title of the ''Hercule Gaulois'' ("Gallic Hercules"), concocting a genealogy that traced the House of Navarre back to a nephew of Hercules

Hercules (, ) is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

The Romans adapted the Gr ...

' son Hispalus.The official account, ''Labyrinthe royal...'' quoted in Jean Seznec, ''The Survival of the Pagan Gods'', (B.F. Sessions, tr., 1995) p. 26 His marriage to Marie de' Medici produced six children:

Armorial

The arms of Henry IV changed throughout his lifetime:as Prince of Béarn and Duke of Vendôme File:Henri de Bourbon Roi de Navarre.svg, From 1572,

as King of Navarre File:Arms of France and Navarre (1589-1790).svg, From 1589,

as King of France and Navarre (also used by his successors) File:Grand Royal Coat of Arms of France & Navarre.svg, Grand Royal Coat of Arms of Henry and the House of Bourbon as Kings of France and Navarre (1589–1789)

References

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *online

Further reading

* * * * * Crawford, Katherine B. "The politics of promiscuity: Masculinity and heroic representation at the court of Henry IV." ''French Historical Studies'' 26.2 (2003): 225–252. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Wolfe, Michael (1993). ''The Conversion of Henri IV: Politics, Power, and Religious Belief in Early Modern France''. Cambridge, MA:Harvard University Press

Harvard University Press (HUP) is an academic publishing house established on January 13, 1913, as a division of Harvard University. It is a member of the Association of University Presses. Its director since 2017 is George Andreou.

The pres ...

.

Fiction

*George Chapman

George Chapman ( – 12 May 1634) was an English dramatist, translator and poet. He was a classical scholar whose work shows the influence of Stoicism. Chapman is seen as an anticipator of the metaphysical poets of the 17th century. He is ...

(1559?–1634), '' The Conspiracy and Tragedy of Charles, Duke of Byron'' (1608), éd. John Margeson (Manchester: Manchester University Press

Manchester University Press is the university press of the University of Manchester, England, and a publisher of academic books and journals. Manchester University Press has developed into an international publisher. It maintains its links with t ...

, 1988)

* Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas (born Alexandre Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie, 24 July 1802 – 5 December 1870), also known as Alexandre Dumas , was a French novelist and playwright.

His works have been translated into many languages and he is one of the mos ...

, '' La Reine Margot'' (''Queen Margot'') (1845)

* Heinrich Mann

Luiz Heinrich Mann (; March 27, 1871 – March 11, 1950), best known as simply Heinrich Mann, was a German writer known for his sociopolitical novels. From 1930 until 1933, he was president of the fine poetry division of the Prussian Academy ...

, ' (1935); ' (1938)

* Maynard, Katherine. ''Reveries of Community: French Epic in the Age of Henri IV, 1572–1616'' (Northwestern University Press, 2017).

* M. de Rozoy, ' (1774)

External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Henry 04 Of France 1553 births 1610 deaths 16th-century kings of France 17th-century kings of France 16th-century princes of Andorra 17th-century princes of Andorra 16th-century Navarrese monarchs 17th-century Navarrese monarchs Ancien Régime Assassinated French people Burials at the Basilica of Saint-Denis Converts to Roman Catholicism from Calvinism Counts of Armagnac Counts of Foix Deaths by stabbing in France Dukes of Vendôme French Calvinist and Reformed Christians French Roman Catholics Heirs presumptive to the French throne House of Bourbon Knights of the Garter Navarrese infantes Navarrese monarchs Nostradamus Occitan people People excommunicated by the Catholic Church People from Pau, Pyrénées-Atlantiques People murdered in Paris French people of the French Wars of Religion 17th-century murdered monarchs 16th-century peers of France 17th-century peers of France People murdered in 1610 Sons of kings Sons of queens regnant