Henry Fielding on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Henry Fielding (22 April 1707 – 8 October 1754) was an English writer and magistrate known for the use of humour and satire in his works. His 1749 comic novel ''

Fielding never stopped writing political satire and satires of current arts and letters. '' The Tragedy of Tragedies'' (for which Hogarth designed the frontispiece) was, for example, quite successful as a printed play. Based on his earlier ''

Fielding never stopped writing political satire and satires of current arts and letters. '' The Tragedy of Tragedies'' (for which Hogarth designed the frontispiece) was, for example, quite successful as a printed play. Based on his earlier ''

Despite the scandal, Fielding's consistent anti-Jacobitism and support for the

Despite the scandal, Fielding's consistent anti-Jacobitism and support for the  In January 1752 Fielding started a fortnightly, '' The Covent-Garden Journal'', published under the pseudonym "Sir Alexander Drawcansir, Knt., Censor of Great Britain" until November of that year. Here Fielding challenged the "armies of Grub Street" and periodical writers of the day in a conflict that became the Paper War of 1752–1753.

Fielding then published ''Examples of the Interposition of Providence in the Detection and Punishment of Murder'' (1752), a treatise rejecting deistic and materialistic visions of the world in favour of belief in God's presence and divine judgement, arguing that the murder rate was rising due to neglect of the Christian religion.Claire Valier, 2005. ''Crime and Punishment in Contemporary Culture''. Routledge. p. 20. In 1753 he wrote ''Proposals for Making an Effectual Provision for the Poor''.

In January 1752 Fielding started a fortnightly, '' The Covent-Garden Journal'', published under the pseudonym "Sir Alexander Drawcansir, Knt., Censor of Great Britain" until November of that year. Here Fielding challenged the "armies of Grub Street" and periodical writers of the day in a conflict that became the Paper War of 1752–1753.

Fielding then published ''Examples of the Interposition of Providence in the Detection and Punishment of Murder'' (1752), a treatise rejecting deistic and materialistic visions of the world in favour of belief in God's presence and divine judgement, arguing that the murder rate was rising due to neglect of the Christian religion.Claire Valier, 2005. ''Crime and Punishment in Contemporary Culture''. Routledge. p. 20. In 1753 he wrote ''Proposals for Making an Effectual Provision for the Poor''.

Examples of the interposition of Providence in the Detection and Punishment of Murder containing above thirty cases in which this dreadful crime has been brought to light in the most extraordinary and miraculous manner; collected from various authors, ancient and modern

'' (1752) *'' The Covent-Garden Journal'' – periodical, 1752 *'' The Journal of a Voyage to Lisbon'' – travel narrative, 1755

Famous Quotes by Henry Fielding

* *

Henry Fielding

at th

Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fielding, Henry 1707 births 1754 deaths 18th-century English novelists 18th-century English male writers Burials at the British Cemetery, Lisbon 18th-century English dramatists and playwrights 18th-century English judges English satirists English satirical novelists English Christians Henry People educated at Eton College People from Mendip District Writers from Somerset English male dramatists and playwrights English male novelists

The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling

''The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling'', often known simply as ''Tom Jones'', is a comic novel by English playwright and novelist Henry Fielding. It is a ''Bildungsroman'' and a picaresque novel. It was first published on 28 February 1749 in ...

'' was a seminal work in the genre. Along with Samuel Richardson

Samuel Richardson (baptised 19 August 1689 – 4 July 1761) was an English writer and printer known for three epistolary novels: '' Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded'' (1740), '' Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady'' (1748) and '' The Histo ...

, Fielding is seen as the founder of the traditional English novel. He also played an important role in the history of law enforcement in the United Kingdom, using his authority as a magistrate to found the Bow Street Runners

The Bow Street Runners were the law enforcement officers of the Bow Street Magistrates' Court in the City of Westminster. They have been called London's first professional police force. The force originally numbered six men and was founded in 1 ...

, London's first professional police force.

Early life

Henry Fielding was born on 22 April 1707 at Sharpham Park, the seat of his mother's family in Sharpham, Somerset. He was the son of Lt.-Gen. Edmund Fielding and Sarah Gould, daughter of Sir Henry Gould. A scion of theEarl of Denbigh

Earl of Denbigh (pronounced 'Denby') is a title in the Peerage of England. It was created in 1622 for William Feilding, 1st Earl of Denbigh, William Feilding, Viscount Feilding, a courtier, admiral, and brother-in-law of the powerful George Vill ...

, his father was nephew of William Fielding, 3rd Earl of Denbigh.

Educated at Eton College

Eton College ( ) is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school providing boarding school, boarding education for boys aged 13–18, in the small town of Eton, Berkshire, Eton, in Berkshire, in the United Kingdom. It has educated Prime Mini ...

, Fielding began a lifelong friendship with William Pitt the Elder

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham (15 November 170811 May 1778) was a British Whig statesman who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1766 to 1768. Historians call him "Chatham" or "Pitt the Elder" to distinguish him from his son ...

. His mother died when he was 11. A suit for custody was brought by his grandmother against his charming but irresponsible father, Lt Gen. Edmund Fielding. The settlement placed Henry in his grandmother's care, but he continued to see his father in London.

In 1725, Henry tried to abduct his cousin Sarah Andrews (with whom he was infatuated) while she was on her way to church. He fled to avoid prosecution.

In 1728, Fielding travelled to Leiden

Leiden ( ; ; in English language, English and Archaism, archaic Dutch language, Dutch also Leyden) is a List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality in the Provinces of the Nethe ...

to study classics and law at the university. However, penury forced him back to London, where he began writing for the theatre. Some of his work savagely criticised the government of Prime Minister Sir Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford (; 26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745), known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole, was a British Whigs (British political party), Whig statesman who is generally regarded as the ''de facto'' first Prim ...

.

Dramatist and novelist

According to George R. Levine, Henry Fielding, in his first writings used two forms of "rhetorical poses" that were popular during the eighteenth century. Henry Fielding would construct "the non-ironic pseudonym such as Addison and Steele used in the ''Spectator,'' and the ironic mask or ''Persona'', such as Swift used in A Modest Proposal." The Theatrical Licensing Act 1737 is said to be a direct response to his activities in writing for the theatre. Although the play that triggered the act was the unproduced, anonymously authored '' The Golden Rump'', Fielding's dramatic satires had set the tone. Once it was passed, political satire on stage became all but impossible. Fielding retired from the theatre and resumed his legal career to support his wife Charlotte Craddock and two children by becoming abarrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include arguing cases in courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, jurisprud ...

, joining the Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court entitled to Call to the bar, call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple (with whi ...

in 1737 and being called to the bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

there in 1740.

Fielding's lack of financial acumen meant the family often endured periods of poverty, but they were helped by Ralph Allen, a wealthy benefactor, on whom Squire Allworthy in ''Tom Jones'' would be based. Allen went on to provide for the education and support of Fielding's children after the writer's death.

Fielding never stopped writing political satire and satires of current arts and letters. '' The Tragedy of Tragedies'' (for which Hogarth designed the frontispiece) was, for example, quite successful as a printed play. Based on his earlier ''

Fielding never stopped writing political satire and satires of current arts and letters. '' The Tragedy of Tragedies'' (for which Hogarth designed the frontispiece) was, for example, quite successful as a printed play. Based on his earlier ''Tom Thumb

Tom Thumb is a character of English folklore. ''The History of Tom Thumb'' was published in 1621 and was the first known fairy tale printed in English. Tom is no bigger than his father's thumb, and his adventures include being swallowed by a cow, ...

'', this was another of Fielding's irregular plays published under the name of H. Scriblerus Secundus, a pseudonym intended to link himself ideally with the Scriblerus Club of literary satirists founded by Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish writer, essayist, satirist, and Anglican cleric. In 1713, he became the Dean (Christianity), dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin, and was given the sobriquet "Dean Swi ...

, Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early ...

and John Gay

John Gay (30 June 1685 – 4 December 1732) was an English poet and dramatist and member of the Scriblerus Club. He is best remembered for ''The Beggar's Opera'' (1728), a ballad opera. The characters, including Captain Macheath and Polly Peach ...

. He also contributed several works to journals.

From 1734 to 1739, Fielding wrote anonymously for the leading Tory

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The To ...

periodical, ''The Craftsman'', against the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford (; 26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745), known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole, was a British Whigs (British political party), Whig statesman who is generally regarded as the ''de facto'' first Prim ...

., p. xvi His patron was the opposition Whig MP George Lyttelton, a boyhood friend from Eton to whom he later dedicated '' Tom Jones''. Lyttelton followed his leader Lord Cobham in forming a Whig opposition to Walpole's government called the Cobhamites, which included another of Fielding's Eton friends, William Pitt. In ''The Craftsman'', Fielding voiced an opposition attack on bribery and corruption in British politics. Despite writing for the opposition to Walpole, which included Tories as well as Whigs, Fielding was "unshakably a Whig" and often praised Whig heroes such as the Duke of Marlborough and Gilbert Burnet.

Fielding dedicated his play ''Don Quixote in England'' to the opposition Whig leader Lord Chesterfield. It appeared on 17 April 1734, the same day writs were issued for the general election

A general election is an electoral process to choose most or all members of a governing body at the same time. They are distinct from By-election, by-elections, which fill individual seats that have become vacant between general elections. Gener ...

. He dedicated his 1735 play '' The Universal Gallant'' to Charles Spencer, 3rd Duke of Marlborough, a political follower of Chesterfield. The other prominent opposition paper, ''Common Sense'', founded by Chesterfield and Lyttelton, was named after a character in Fielding's '' Pasquin'' (1736). Fielding wrote at least two articles for it in 1737 and 1738.

Fielding continued to air political views in satirical articles and newspapers in the late 1730s and early 1740s. He was the main writer and editor from 1739 to 1740 for the satirical paper ''The Champion'', which was sharply critical of Walpole's government and of pro-government literary and political writers. He sought to evade libel charges by making its political attacks so funny or embarrassing to the victim that a publicized court case would seem even worse. He later became chief writer for the Whig government of Henry Pelham.

Fielding took to novel writing in 1741, angered by Samuel Richardson

Samuel Richardson (baptised 19 August 1689 – 4 July 1761) was an English writer and printer known for three epistolary novels: '' Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded'' (1740), '' Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady'' (1748) and '' The Histo ...

's success with '' Pamela''. His first success was an anonymous parody of that novel, called '' Shamela''. This follows the model of Tory satirists of the previous generation, notably Swift and Gay.

Fielding followed this with '' Joseph Andrews'' (1742), an original work supposedly dealing with Pamela's brother, Joseph. His purpose, however, was more than parody, for as stated in the preface, he intended a "kind of writing which I do not remember to have seen hitherto attempted in our language." In what Fielding called a "comic epic poem in prouse", he blended two classical traditions: that of the epic, which had been poetic, and that of the drama, but emphasizing the comic rather than the tragic. Another distinction of ''Joseph Andrews'' and the novels to come was use of everyday reality of character and action, as opposed to the fables of the past. While begun as a parody, it developed into an accomplished novel in its own right and is seen as Fielding's debut as a serious novelist. In 1743, he published a novel in the ''Miscellanies'' volume III (which was the first volume of the Miscellanies): '' The Life and Death of Jonathan Wild, the Great'', which is sometimes counted as his first, as he almost certainly began it before he wrote ''Shamela'' and ''Joseph Andrews''. It is a satire of Walpole equating him and Jonathan Wild

Jonathan Wild, also spelled Wilde (1682 or 1683 – 24 May 1725), was an English thief-taker and a major figure in London's criminal underworld, notable for operating on both sides of the law, posing as a public-spirited vigilante entitled th ...

, the gang leader and highwayman. He implicitly compares the Whig party in Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

with a gang of thieves run by Walpole, whose constant desire to be a "Great Man" (a common epithet with Walpole) ought to culminate in the antithesis of greatness: hanging.

Fielding's anonymous '' The Female Husband'' (1746) fictionalizes a case in which a female transvestite was tried for duping another woman into marriage; this was one of several small pamphlets costing sixpence. Though a minor piece in his life's work, it reflects his preoccupation with fraud, shamming and masks.

His greatest work is ''The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling'' (1749), a meticulous comic novel with elements of the picaresque and the Bildungsroman

In literary criticism, a bildungsroman () is a literary genre that focuses on the psychological and moral growth and change of the protagonist from childhood to adulthood (coming of age). The term comes from the German words ('formation' or 'edu ...

, telling a convoluted tale of how a foundling came into a fortune. The novel tells of Tom's alienation from his foster father, Squire Allworthy, and his sweetheart, Sophia Western, and his reconciliation with them after lively and dangerous adventures on the road and in London. It triumphs as a presentation of English life and character in the mid-18th century. Every social type is represented and through them every shade of moral behaviour. Fielding's varied style tempers the basic seriousness of the novel and his authorial comment before each chapter adds a dimension to a conventional, straightforward narrative.

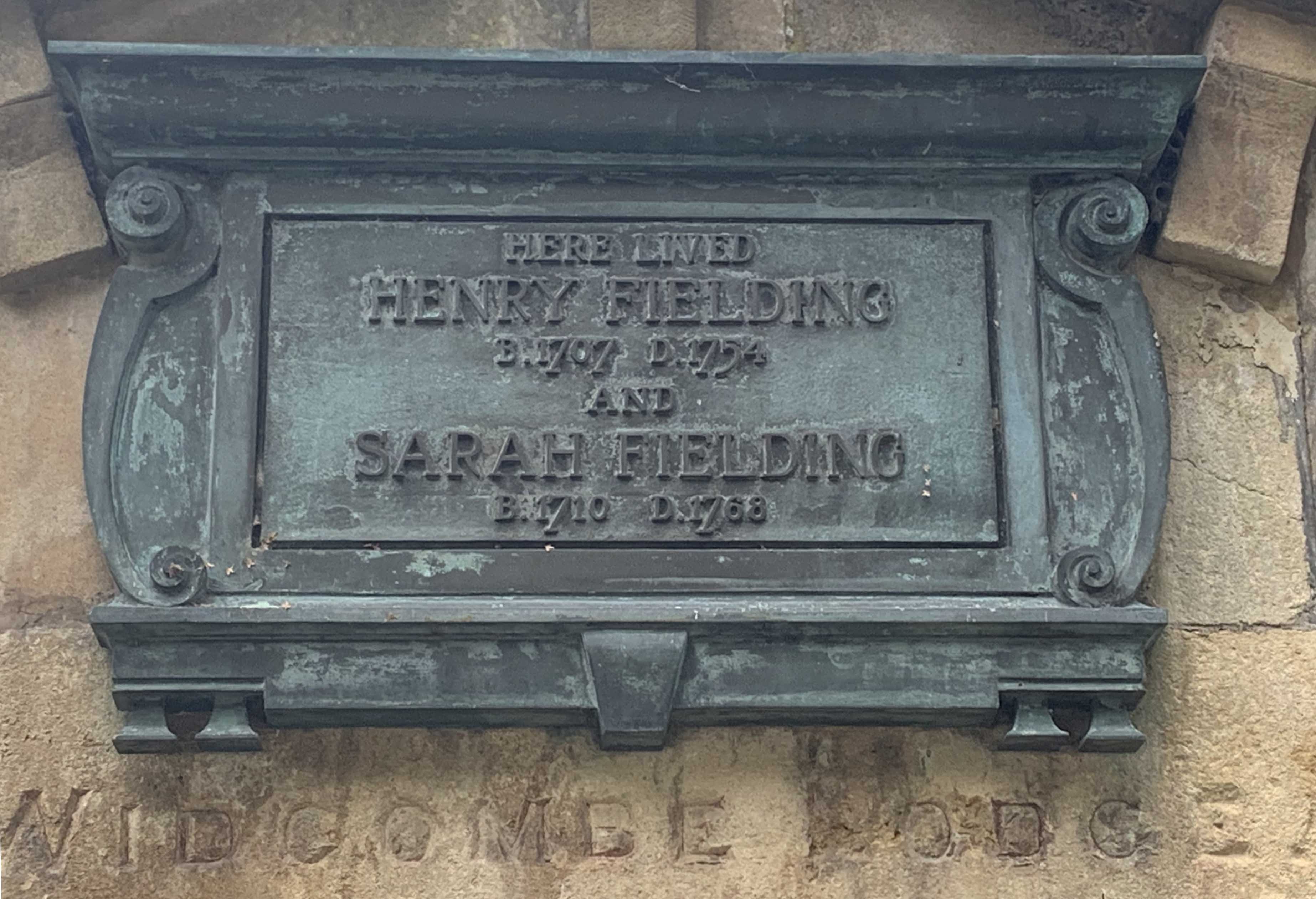

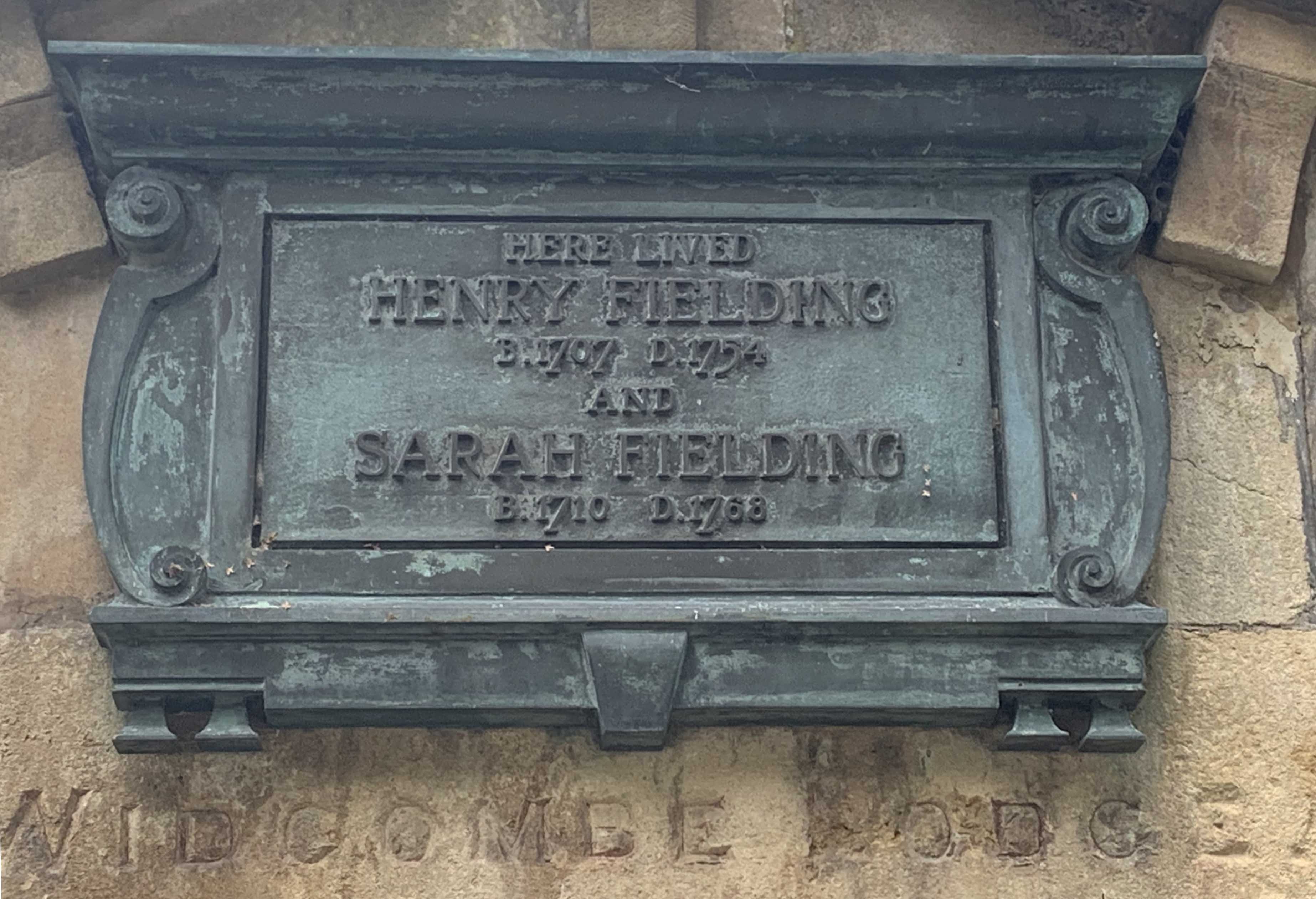

Sister

Fielding's younger sister,Sarah

Sarah (born Sarai) is a biblical matriarch, prophet, and major figure in Abrahamic religions. While different Abrahamic faiths portray her differently, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all depict her character similarly, as that of a pious woma ...

, also became a successful writer. Her novel ''The Governess, or The Little Female Academy

''The Governess; or, The Little Female Academy'' (published 1749) by Sarah Fielding is the first full-length novel written for children. As such and in itself it is a significant work of List of 18th-century British children's literature titles ...

'' (1749) is thought to be the first in English aimed expressly at children.

Marriages

Fielding married Charlotte Craddock in 1734 at the Church of St Mary in Charlcombe, Somerset. She died in 1744, and he later modelled the heroines of ''Tom Jones'' and of ''Amelia'' on her. They had five children; their only daughter Henrietta died at the age of 23, having already been "in deep decline" when she married a military engineer, James Gabriel Montresor, some months before. Three years after Charlotte's death, Fielding disregarded public opinion by marrying her former maid Mary Daniel, who was pregnant. Mary bore five children: three daughters who died young, and two sons, William and Allen.Jurist and magistrate

Despite the scandal, Fielding's consistent anti-Jacobitism and support for the

Despite the scandal, Fielding's consistent anti-Jacobitism and support for the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

led to his appointment a year later as Westminster's chief magistrate, while his literary career went from strength to strength. Most of his work concerned London's criminal population of thieves, informers, gamblers and prostitutes. Though living in a corrupt and callous society, he became noted for impartial judgements, incorruptibility and compassion for those whom social inequities led into crime. The income from his office ("the dirtiest money upon earth") dwindled as he refused to take money from the very poor. Joined by his younger half-brother John, he helped found what some call London's first police force, the Bow Street Runners

The Bow Street Runners were the law enforcement officers of the Bow Street Magistrates' Court in the City of Westminster. They have been called London's first professional police force. The force originally numbered six men and was founded in 1 ...

, in 1749.

According to the historian G. M. Trevelyan, the Fieldings were two of the best magistrates in 18th-century London, who did much to enhance judicial reform and improve prison conditions. Fielding's influential pamphlets and enquiries included a proposal for abolishing public hangings. This did not, however, imply opposition to capital punishment as such – as is evident, for example, in his presiding in 1751 over the trial of the notorious criminal James Field, finding him guilty in a robbery and sentencing him to hang. John Fielding, despite being blind by then, succeeded his older brother as chief magistrate, becoming known as the "Blind Beak of Bow Street" for his ability to recognise criminals by their voices alone..

In January 1752 Fielding started a fortnightly, '' The Covent-Garden Journal'', published under the pseudonym "Sir Alexander Drawcansir, Knt., Censor of Great Britain" until November of that year. Here Fielding challenged the "armies of Grub Street" and periodical writers of the day in a conflict that became the Paper War of 1752–1753.

Fielding then published ''Examples of the Interposition of Providence in the Detection and Punishment of Murder'' (1752), a treatise rejecting deistic and materialistic visions of the world in favour of belief in God's presence and divine judgement, arguing that the murder rate was rising due to neglect of the Christian religion.Claire Valier, 2005. ''Crime and Punishment in Contemporary Culture''. Routledge. p. 20. In 1753 he wrote ''Proposals for Making an Effectual Provision for the Poor''.

In January 1752 Fielding started a fortnightly, '' The Covent-Garden Journal'', published under the pseudonym "Sir Alexander Drawcansir, Knt., Censor of Great Britain" until November of that year. Here Fielding challenged the "armies of Grub Street" and periodical writers of the day in a conflict that became the Paper War of 1752–1753.

Fielding then published ''Examples of the Interposition of Providence in the Detection and Punishment of Murder'' (1752), a treatise rejecting deistic and materialistic visions of the world in favour of belief in God's presence and divine judgement, arguing that the murder rate was rising due to neglect of the Christian religion.Claire Valier, 2005. ''Crime and Punishment in Contemporary Culture''. Routledge. p. 20. In 1753 he wrote ''Proposals for Making an Effectual Provision for the Poor''.

Death

Fielding's humanitarian commitment to justice in the 1750s (for instance in support of Elizabeth Canning) coincided with rapid deterioration in his health.Gout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of pain in a red, tender, hot, and Joint effusion, swollen joint, caused by the deposition of needle-like crystals of uric acid known as monosodium urate crysta ...

, asthma

Asthma is a common long-term inflammatory disease of the airways of the lungs. It is characterized by variable and recurring symptoms, reversible airflow obstruction, and easily triggered bronchospasms. Symptoms include episodes of wh ...

and cirrhosis

Cirrhosis, also known as liver cirrhosis or hepatic cirrhosis, chronic liver failure or chronic hepatic failure and end-stage liver disease, is a chronic condition of the liver in which the normal functioning tissue, or parenchyma, is replaced ...

of the liver left him on crutches, and with other afflictions sent him to Portugal in 1754 to seek a cure, only to die two months later in Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

, reportedly in pain and mental distress. His tomb there is in the British Cemetery (''Cemitério Inglês''), the graveyard of St. George's Church, Lisbon.

List of works

Novels

*'' An Apology for the Life of Mrs. Shamela Andrews'' – novella, 1741 *'' The History of the Adventures of Joseph Andrews and his Friend, Mr. Abraham Adams'' – 1742 *'' The Life and Death of Jonathan Wild, the Great'' – 1743, ironic treatment ofJonathan Wild

Jonathan Wild, also spelled Wilde (1682 or 1683 – 24 May 1725), was an English thief-taker and a major figure in London's criminal underworld, notable for operating on both sides of the law, posing as a public-spirited vigilante entitled th ...

, a notorious underworld figure of the time. Published as Volume 3 of ''Miscellanies''

*''The Female Husband or the Surprising History of Mrs Mary alias Mr George Hamilton, who was convicted of having married a young woman of Wells and lived with her as her husband, taken from her own mouth since her confinement'' – pamphlet, fictionalized report, 1746

*''The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling

''The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling'', often known simply as ''Tom Jones'', is a comic novel by English playwright and novelist Henry Fielding. It is a ''Bildungsroman'' and a picaresque novel. It was first published on 28 February 1749 in ...

'' – 1749

*''A Journey from this World to the Next'' – 1749

*'' Amelia'' – 1751

Partial list of poems

*''The Masquerade'' – (Fielding's first publication) *''Part of Juvenal's Sixth Satire, Modernized in Burlesque Verse''Plays

* '' Love in Several Masques'' (1728) * '' Rape upon Rape; or, The Justice Caught in his own Trap'' (1730), also known as ''The Coffee-House Politician,'' played in rep with ''Tom Thumb the Great'' * ''Tom Thumb the Great: A Burlesque Tragedy'' (1730) * '' The Temple Beau'' (1730) * '' The Author's Farce; and The Pleasures of the Town'' (1730) * '' The Letter Writers, or A New Way to Keep a Wife at Home: A Farce'' (1731), originally an afterpiece to ''The Tragedy of Tragedies'' * '' The Tragedy of Tragedies: or the Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great'' (1731), a revision of ''Tom Thumb the Great'' * ''The Coffee-House Politician,'' ''or The Justice Caught in his own Trap, A Comedy'' (1730–31), a reworking of ''Rape upon Rape. '' In 1730, another act was added to the play, titled ''The Battle of the Poets'' (author unknown). * '' The Old Debauchees'' (1732), originally titled ''The Despairing Debauchee''. Later revived as ''The Becauchees; or, The Jesuit Caught'' * '' The Covent-Garden Tragedy'' (1732), originally appeared in rep with ''The Old Debauchees,'' but only played one night. Eventually revived in rep with ''Don Quixote in England'' * '' The Mock Doctor: or The Dumb Lady Cur'd'' (1732), adapted from Molière's '' Le Médecin malgré lui,'' played in rep with ''The Old Debauchees,'' as a replacement for ''The Covent-Garden Tragedy'' * '' The Welsh Opera'' (1731), originally a companion piece to ''The Tragedy of Tragedies'' * '' The Grub Street Opera'' (1731), Fieldings only closet drama, expanded from his play ''The Welsh Opera'' * '' The Modern Husband'' (1732) * '' The Lottery'' (1732), played in rep with Joseph Addison's ''Cato. '' A ballad opera with music from "Mr. Seedo." * ''The Intriguing Chambermaid'' (1734), after Jean-François Regnard * ''An Old Man Taught Wisdom, or The Virgin Unmasked, A Farce'' (1734), ballad opera * ''Don Quixote in England'' (1734), ballad opera * ''The Miser'' (1735), incidental music by Thomas Arne, based on the Molière and Plautus * '' The Universal Gallant, or The Different Husbands'' (1735) * '' Pasquin'' (1736) * ''Eurydice, A Farce'' (1737) * ''Eurydice Hiss'd, or A Word to the Wise'' (1737) * '' The Historical Register for the Year 1736'' – 1737 * ''Miss Lucy in Town'', ballad farce librettist (1742), composer Thomas Arne, revived in 1770 as ''The Country Madcap'' * ''Tumbledown Dick or Phaeton in the Suds'' (1744), ballad opera * ''The Wedding-Day. A Comedy.'' (1743) * ''The Fathers'' (1778), published posthumously with Oliver Goldsmith's '' The Good-Natur'd Man'' Further Adaptations * ''The Opera of Operas; Or, Tom Thumb the Great Alter’d from the Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great and Set to Musick after the Italian Manner. As It Is Performing at the New Theatre in the Hay-Market'', (1733) written byEliza Haywood

Eliza Haywood (c. 1693 – 25 February 1756), born Elizabeth Fowler, was an English writer, actress and publisher. An increase in interest and recognition of Haywood's literary works began in the 1980s. Described as "prolific even by the standar ...

and William Hatchett, music by Thomas Arne, adapted from the Fielding

* ''Tom Thumb the Great: A Burlesque Tragedy from Fielding'' (1805–1810), written by Kane O’Hara Esq., adapted from Fielding

* ''Squire Badger: A burletta in two acts'', Thomas Arne composer and librettist (1772), after Henry Fielding's ''Don Quixote in England'' (1729). The work was revived under the name ''The Sot'' in 1775.

* ''The Rival Queens'' (1794)'','' adapted by William Holcroft from Fielding's ''The Covent-Garden Tragedy''

* '' Lock Up Your Daughters'' (1959), musical based on ''Rape Upon Rape'', book by Bernard Miles, lyrics by Lionel Bart

Lionel Bart (1 August 1930 – 3 April 1999) was an English writer and composer of pop music and musicals. He wrote Tommy Steele's "Rock with the Caveman" and was the sole creator of the musical ''Oliver!'' (1960). With ''Oliver!'' and his work ...

, music by Laurie Johnson. Made into a non-musical film (1969).

Miscellaneous writings

*''Miscellanies'' – collection of works, 1743, contained the poem "Part of Juvenal's Sixth Satire, Modernized in Burlesque Verse" *'Examples of the interposition of Providence in the Detection and Punishment of Murder containing above thirty cases in which this dreadful crime has been brought to light in the most extraordinary and miraculous manner; collected from various authors, ancient and modern

'' (1752) *'' The Covent-Garden Journal'' – periodical, 1752 *'' The Journal of a Voyage to Lisbon'' – travel narrative, 1755

References

Further reading

*Battestin, Martin C. & Battestin, Ruthe R., ''Henry Fielding. A Life'' (Routledge, 1989) *Dircks, Richard J., ''Henry Fielding. Twayne's English Authors'' (Twayne, 1983) *Hunter, J. Paul, ''Occasional Form: Henry Fielding and the Chains of Circumstance'' (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985) *Pagliaro, Harold, ''Henry Fielding: A Literary Life'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 1998) *Pringle, Patrick, ''Hue and Cry: The Birth of the British Police'' (Museum Press, 1955) *Rawson, C. J., ''Henry Fielding and the Augustan Ideal Under Stress'' (Routledge, Kegan & Paul, 1972) *Rogers, Pat, ''Henry Fielding. A Biography'' (Paul Elek, 1979) * Thomas, Donald, ''Henry Fielding'' (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1990) *Simpson, K. G., ''Henry Fielding: Justice Observed'' (Vision Press, 1985) *William, Ioan (ed.), ''The Criticism of Henry Fielding'' (Routledge, Kegan & Paul, 1970)External links

* * * *Famous Quotes by Henry Fielding

* *

Henry Fielding

at th

Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fielding, Henry 1707 births 1754 deaths 18th-century English novelists 18th-century English male writers Burials at the British Cemetery, Lisbon 18th-century English dramatists and playwrights 18th-century English judges English satirists English satirical novelists English Christians Henry People educated at Eton College People from Mendip District Writers from Somerset English male dramatists and playwrights English male novelists

Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding (22 April 1707 – 8 October 1754) was an English writer and magistrate known for the use of humour and satire in his works. His 1749 comic novel ''The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling'' was a seminal work in the genre. Along wi ...

British parodists

Parody novelists