Helen Beatrix Potter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Helen Beatrix Heelis (; 28 July 186622 December 1943), usually known as Beatrix Potter ( ), was an English writer,

Potter's family on both sides were from the

Potter's family on both sides were from the  Potter's parents lived comfortably at 2 Bolton Gardens,

Potter's parents lived comfortably at 2 Bolton Gardens,

In the

In the

Potter's artistic and literary interests were deeply influenced by fairy tales and fantasy. She was a student of the classic fairy tales of Western Europe as well as stories from the

Potter's artistic and literary interests were deeply influenced by fairy tales and fantasy. She was a student of the classic fairy tales of Western Europe as well as stories from the  In 1900, Potter revised her tale about the four little rabbits, and fashioned a dummy book of it – it has been suggested, in imitation of

In 1900, Potter revised her tale about the four little rabbits, and fashioned a dummy book of it – it has been suggested, in imitation of  On 2 October 1902, ''

On 2 October 1902, ''

The tenant farmer John Cannon and his family agreed to stay on to manage the farm for her while she made physical improvements and learned the techniques of fell farming and of raising livestock, including pigs, cows and chickens; the following year she added sheep. Realising she needed to protect her boundaries, she sought advice from W.H. Heelis & Son, a local firm of solicitors with offices in nearby

The tenant farmer John Cannon and his family agreed to stay on to manage the farm for her while she made physical improvements and learned the techniques of fell farming and of raising livestock, including pigs, cows and chickens; the following year she added sheep. Realising she needed to protect her boundaries, she sought advice from W.H. Heelis & Son, a local firm of solicitors with offices in nearby

Potter continued to write stories and to draw, although mostly for her own pleasure. In 1922, ''

Potter continued to write stories and to draw, although mostly for her own pleasure. In 1922, ''

Potter left almost all the original illustrations for her books to the National Trust. The copyright to her stories and merchandise was then given to her publisher Frederick Warne & Co, now a division of the

Potter left almost all the original illustrations for her books to the National Trust. The copyright to her stories and merchandise was then given to her publisher Frederick Warne & Co, now a division of the

Beatrix Potter's fossils and her interest in geology – B. G. Gardiner

* * * *

Beatrix Potter

at the

Collection of Potter materials

at

Beatrix Potter online feature

at the University of Pittsburgh School of Information Sciences

Beatrix Potter Society, UK

Exhibition of Beatrix Potter's Picture Letters at the Morgan Library

Beatrix Potter Collection

(digitized images from the

illustrator

An illustrator is an artist who specializes in enhancing writing or elucidating concepts by providing a visual representation that corresponds to the content of the associated text or idea. The illustration may be intended to clarify complicate ...

, natural scientist

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

, and conservationist. She is best known for her children's books

A child () is a human being between the stages of birth and puberty, or between the developmental period of infancy and puberty. The term may also refer to an unborn human being. In English-speaking countries, the legal definition of ''chi ...

featuring animals, such as ''The Tale of Peter Rabbit

''The Tale of Peter Rabbit'' is a children's book written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter that follows mischievous and disobedient young Peter Rabbit as he gets into, and is chased around, the garden of Mr. McGregor. He escapes and returns h ...

'', which was her first commercially published work in 1902. Her books, including '' The Tale of Jemima Puddle Duck'' and ''The Tale of Tom Kitten

''The Tale of Tom Kitten'' is a children's book, written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter. It was released by Frederick Warne & Co. in September 1907. The tale is about manners and how children react to them. Tabitha Twitchit, a cat, invites f ...

'', have sold more than 250 million copies. An entrepreneur, Potter was a pioneer of character merchandising. In 1903, Peter Rabbit

Peter Rabbit is a fictional animal character in various children's stories by English author Beatrix Potter.

A mischievous, adventurous young rabbit who wears a blue jacket, he first appeared in ''The Tale of Peter Rabbit'' in 1902, and subseq ...

was the first fictional character to be made into a patented stuffed toy

A stuffed toy is a toy with an outer fabric sewn from a textile and stuffed with flexible material. They are known by many names, such as plush toys, plushies, lovies and stuffies; in Britain and Australia, they may also be called soft toys ...

, making him the oldest licensed character.

Born into an upper-middle-class household, Potter was educated by governess

A governess is a woman employed as a private tutor, who teaches and trains a child or children in their home. A governess often lives in the same residence as the children she is teaching; depending on terms of their employment, they may or ma ...

es and grew up isolated from other children. She had numerous pets and spent holidays in Scotland and the Lake District

The Lake District, also known as ''the Lakes'' or ''Lakeland'', is a mountainous region and National parks of the United Kingdom, national park in Cumbria, North West England. It is famous for its landscape, including its lakes, coast, and mou ...

, developing a love of landscape, flora and fauna, all of which she closely observed and painted. Potter's study and watercolours of fungi led to her being widely respected in the field of mycology

Mycology is the branch of biology concerned with the study of fungus, fungi, including their Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy, genetics, biochemistry, biochemical properties, and ethnomycology, use by humans. Fungi can be a source of tinder, Edible ...

. In her thirties, Potter self-published the highly successful children's book ''The Tale of Peter Rabbit''. Following this, Potter began writing and illustrating children's books full-time.

Potter wrote over sixty books, with the best known being her twenty-three children's tales. In 1905, using the proceeds from her books and a legacy from an aunt, Potter bought Hill Top Farm

Hill Top is a 17th-century house in Near Sawrey near Hawkshead, in the English county of Cumbria. It is an example of Lakeland vernacular architecture with random stone walls and slate roof. The house was once the home of children's author and ...

in Near Sawrey

Near Sawrey and Far Sawrey are two neighbouring villages in the Furness area of Cumbria, England. Within the boundaries of the historic county of Lancashire, both are located in the Lake District between the village of Hawkshead and the lake ...

, a village in the Lake District. Over the following decades, she purchased additional farms to preserve the unique hill country landscape. In 1913, at the age of 47, she married William Heelis (1871–1945), a respected local solicitor with an office in Hawkshead

Hawkshead is a village and civil parish in Westmorland and Furness, Cumbria, England. It lies within the Lake District National Park and was historically part of Lancashire. The parish includes the hamlets of Hawkshead Hill, to the north west, ...

. Potter was also a prize-winning breeder of Herdwick sheep and a prosperous farmer keenly interested in land preservation. She continued to write, illustrate, and design merchandise based on her children's books for British publisher Warne until the duties of land management and her diminishing eyesight made it difficult to continue.

Potter died of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

and heart disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is any disease involving the heart or blood vessels. CVDs constitute a class of diseases that includes: coronary artery diseases (e.g. angina pectoris, angina, myocardial infarction, heart attack), heart failure, ...

on 22 December 1943 at her home in Near Sawrey at the age of 77, leaving almost all her property to the National Trust

The National Trust () is a heritage and nature conservation charity and membership organisation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Trust was founded in 1895 by Octavia Hill, Sir Robert Hunter and Hardwicke Rawnsley to "promote the ...

. She is credited with preserving much of the land that now constitutes the Lake District National Park

The Lake District, also known as ''the Lakes'' or ''Lakeland'', is a mountainous region and National parks of the United Kingdom, national park in Cumbria, North West England. It is famous for its landscape, including its lakes, coast, and mou ...

. Potter's books continue to sell throughout the world in many languages with her stories being retold in songs, films, ballet, and animations, and her life is depicted in two films – ''The Tales of Beatrix Potter

''The Tales of Beatrix Potter'' (US title: ''Peter Rabbit and Tales of Beatrix Potter'') is a 1971 ballet film based on the children's stories of English author and illustrator Beatrix Potter. The film was directed by Reginald Mills, choreograph ...

'' (1983) and ''Miss Potter

''Miss Potter'' is a 2006 biographical drama film directed by Chris Noonan. It is based on the life of children's author and illustrator Beatrix Potter, and combines stories from her own life with animated sequences featuring characters from her ...

'' (2006).

Biography

Early life

Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

area. They were English Unitarians

Unitarian or Unitarianism may refer to:

Christian and Christian-derived theologies

A Unitarian is a follower of, or a member of an organisation that follows, any of several theologies referred to as Unitarianism:

* Unitarianism (1565–present) ...

, associated with dissenting Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

congregations, influential in 19th-century Britain, that affirmed the oneness of God and that rejected the doctrine of the Trinity. Potter's paternal grandfather, Edmund Potter

Edmund Potter (1802–1883) was an English politician and industrialist from Derbyshire. He was a businessman in Manchester, a Member of Parliament (MP) and a grandfather of the author Beatrix Potter.

He was a unitarian and, from 1861 to 1874 ...

, from Glossop

Glossop is a market town in the borough of High Peak (borough), High Peak, Derbyshire, England, east of Manchester, north-west of Sheffield and north of Matlock, Derbyshire, Matlock. Near Derbyshire's borders with Cheshire, Greater Mancheste ...

in Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It borders Greater Manchester, West Yorkshire, and South Yorkshire to the north, Nottinghamshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south-east, Staffordshire to the south a ...

, owned what was then the largest calico

Calico (; in British usage since 1505) is a heavy plain-woven textile made from unbleached, and often not fully processed, cotton. It may also contain unseparated husk parts. The fabric is far coarser than muslin, but less coarse and thick than ...

printing works in England, and later served as a Member of Parliament.

Potter's father, Rupert William Potter (1832–1914), was educated at Manchester College by the Unitarian philosopher James Martineau

James Martineau (; 21 April 1805 – 11 January 1900) was a British Christian philosophy, religious philosopher influential in the history of Unitarianism.

He was the brother of the atheist social theory, social theorist, abolitionist Harriet M ...

. He then trained as a barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include arguing cases in courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, jurisprud ...

in London. Rupert practiced law, specialising in equity law and conveyancing

In law, conveyancing is the transfer of legal title of real property from one person to another, or the granting of an encumbrance such as a mortgage or a lien. A typical conveyancing transaction has two major phases: the exchange of contract ...

. He married Helen Leech (1839–1932) on 8 August 1863 at Hyde Unitarian Chapel, Gee Cross

Gee Cross is a village and suburb of Hyde within Tameside Metropolitan Borough, in Greater Manchester, England.

History

Gee Cross village centre dates back to the times of the Domesday Book. Originally, Gee Cross was the larger village in t ...

. Helen was the daughter of Jane Ashton (1806–1884) and John Leech, a wealthy cotton merchant and shipbuilder from Stalybridge

Stalybridge () is a town in Tameside, Greater Manchester, England. At the 2021 United Kingdom census, 2021 census, it had a population of 26,830.

Historic counties of England, Historically divided between Cheshire and Lancashire, it is east o ...

. Helen's first cousins were siblings Harriet Lupton (''née'' Ashton) and Thomas Ashton, 1st Baron Ashton of Hyde

Thomas Gair Ashton, 1st Baron Ashton of Hyde (5 February 1855 – 1 May 1933), was a British industrialist, philanthropist, Liberal politician and peer.

Early life and career

Ashton was born at Fallowfield, Manchester, Lancashire, the son of ...

. It was reported in July 2014 that Potter had personally given a number of her own original hand-painted illustrations to the two daughters of Arthur and Harriet Lupton, who were cousins to both Beatrix Potter and Catherine, Princess of Wales

Catherine, Princess of Wales (born Catherine Elizabeth Middleton; 9 January 1982), is a member of the British royal family. She is married to William, Prince of Wales, heir apparent to the British throne.

Born in Reading, Catherine grew ...

.

Potter's parents lived comfortably at 2 Bolton Gardens,

Potter's parents lived comfortably at 2 Bolton Gardens, West Brompton

West Brompton is an area of west London, England, that straddles the boundary between the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham and Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. The centuries-old boundary traced by Counter's Creek, probably marke ...

, London, where Helen Beatrix was born on 28 July 1866 and her brother Walter Bertram on 14 March 1872. The house was destroyed in the Blitz

The Blitz (English: "flash") was a Nazi Germany, German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom, for eight months, from 7 September 1940 to 11 May 1941, during the Second World War.

Towards the end of the Battle of Britain in 1940, a co ...

. Bousfield Primary School now stands where the house once was. A blue plaque on the school building testifies to the former site of the Potter home. Both parents were artistically talented, and Rupert was an adept amateur photographer. Rupert had invested in the stock market, and by the early 1890s, he was extremely wealthy.

Beatrix Potter was educated by three governesses, the last of whom was Annie Moore (''née'' Carter), just three years older than Potter, who tutored Potter in German as well as acting as lady's companion

A lady's companion was a woman of genteel birth who lived with a woman of rank or wealth as Affinity (medieval), retainer. The term was in use in the United Kingdom from at least the 18th century to the mid-20th century but it is now archaism, arc ...

. She and Potter remained friends throughout their lives, and Annie's eight children were the recipients of many of Potter's picture letters. It was Annie who later suggested that these letters might make good children's books.

She and her younger brother Walter Bertram (1872–1918) grew up with few friends outside their large extended family. Her parents were artistic, interested in nature, and enjoyed the countryside. As children, Potter and Bertram had numerous small animals as pets which they observed closely and drew endlessly. In their schoolroom, Potter and Bertram kept a variety of small pets—mice, rabbits, a hedgehog and some bats, along with collections of butterflies and other insects—which they drew and studied. Potter was devoted to the care of her small animals, often taking them with her on long holidays. In most of the first fifteen years of her life, Potter spent summer holidays at Dalguise

Dalguise (Scottish Gaelic Dàil Ghiuthais) is a settlement in Perth and Kinross, Scotland. It is situated on the western side of the River Tay on the B898 road, north of Dunkeld. Located there is Dalguise House, a place where, from the age of f ...

, an estate on the River Tay

The River Tay (, ; probably from the conjectured Brythonic ''Tausa'', possibly meaning 'silent one' or 'strong one' or, simply, 'flowing' David Ross, ''Scottish Place-names'', p. 209. Birlinn Ltd., Edinburgh, 2001.) is the longest river in Sc ...

in Perthshire, Scotland

Perthshire (locally: ; ), officially the County of Perth, is a historic county and registration county in central Scotland. Geographically it extends from Strathmore in the east, to the Pass of Drumochter in the north, Rannoch Moor and Ben ...

. There she sketched and explored an area that nourished her imagination and her observation. Her first sketchbook from those holidays, kept at age 8 and dated 1875, is held at and has been digitised by the Victoria & Albert Museum, London. Potter and her brother were allowed great freedom in the country, and both children became adept students of natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

. In 1882, when Dalguise was no longer available, the Potters took their first summer holiday in the Lake District

The Lake District, also known as ''the Lakes'' or ''Lakeland'', is a mountainous region and National parks of the United Kingdom, national park in Cumbria, North West England. It is famous for its landscape, including its lakes, coast, and mou ...

, at Wray Castle

Wray Castle is a Victorian Gothic Revival architecture, neo-gothic building at Claife in Cumbria within the boundaries of the Historic counties of England, historic county of Lancashire. The house and grounds have belonged to the National Trust ...

near Lake Windermere

Windermere (historically Winder Mere) is a ribbon lake in Cumbria, England, and part of the Lake District. It is the largest lake in England by length, area, and volume, but considerably smaller than the largest Scottish lochs and Northern Iri ...

. Here Potter met Hardwicke Rawnsley

Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley (29 September 1851 – 28 May 1920) was an Anglican priest, poet, local politician and conservationist. He became nationally and internationally known as one of the three founders of the National Trust for Places of H ...

, vicar of Wray and later the founding secretary of the National Trust

The National Trust () is a heritage and nature conservation charity and membership organisation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Trust was founded in 1895 by Octavia Hill, Sir Robert Hunter and Hardwicke Rawnsley to "promote the ...

, whose interest in the countryside and country life inspired the same in Potter and who was to have a lasting impact on her life.

At about the age of 14, Potter began to keep a diary, written in a simple substitution cipher

In cryptography, a substitution cipher is a method of encrypting in which units of plaintext are replaced with the ciphertext, in a defined manner, with the help of a key; the "units" may be single letters (the most common), pairs of letters, t ...

of her own devising. Her ''Journal'' was important to the development of her creativity, serving as both sketchbook and literary experiment. In tiny handwriting, she reported on society, recorded her impressions of art and artists, recounted stories and observed life around her. The ''Journal'', deciphered and transcribed by Leslie Linder in 1958, does not provide an intimate record of her personal life, but it is an invaluable source for understanding a vibrant part of British society in the late 19th century. It describes Potter's maturing artistic and intellectual interests, her often amusing insights into the places she visited, and her unusual ability to observe nature and to describe it. Started in 1881, her journal ends in 1897 when her artistic and intellectual energies were absorbed in scientific study and in efforts to publish her drawings. Precocious but reserved and often bored, she was searching for more independent activities and wished to earn some money of her own while dutifully taking care of her parents, dealing with her especially demanding mother, and managing their various households.

Scientific illustrations and work in mycology

In the

In the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the reign of Queen Victoria, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed the ...

, women of her class were privately educated and rarely went to university. Potter's parents encouraged her higher education, but the social norms of the time limited her academic career within Britain's institutions.

Beatrix Potter was interested in every branch of natural science except astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

. Botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

was a passion for most Victorians

Victorian or Victorians may refer to:

19th century

* Victorian era, British history during Queen Victoria's 19th-century reign

** Victorian architecture

** Victorian house

** Victorian decorative arts

** Victorian fashion

** Victorian litera ...

, and nature study

The nature study movement (alternatively, Nature Study or nature-study) was a popular education movement that originated in the United States and spread throughout the English-speaking world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Nature study ...

was a popular enthusiasm. She collected fossils, studied archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

artefacts from London excavations, and was interested in entomology

Entomology (from Ancient Greek ἔντομον (''éntomon''), meaning "insect", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study") is the branch of zoology that focuses on insects. Those who study entomology are known as entomologists. In ...

. In all these areas, she drew and painted her specimens with increasing skill. By the 1890s, her scientific interests centred on mycology

Mycology is the branch of biology concerned with the study of fungus, fungi, including their Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy, genetics, biochemistry, biochemical properties, and ethnomycology, use by humans. Fungi can be a source of tinder, Edible ...

. First drawn to fungi because of their colours and evanescence in nature and her delight in painting them, her interest deepened after meeting Charles McIntosh, a revered naturalist and amateur mycologist, during a summer holiday in Dunkeld in Perthshire

Perthshire (Scottish English, locally: ; ), officially the County of Perth, is a Shires of Scotland, historic county and registration county in central Scotland. Geographically it extends from Strathmore, Angus and Perth & Kinross, Strathmore ...

in 1892. He helped improve the accuracy of her illustrations, taught her taxonomy

image:Hierarchical clustering diagram.png, 280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme o ...

, and supplied her with live specimens to paint during the winter. Linnean Society

The Linnean Society of London is a learned society dedicated to the study and dissemination of information concerning natural history, evolution, and taxonomy. It possesses several important biological specimen, manuscript and literature collec ...

in 1897. It was introduced by Massee because, as a woman, Potter could not attend proceedings nor read her paper. She subsequently withdrew it, realising that some of her samples were contaminated, but continued her microscopic studies for several more years. Her work is only now being properly evaluated. Potter later gave her other mycological and scientific drawings to the Armitt Museum and Library in Ambleside, where mycologists still refer to them to identify fungi. There is also a collection of her fungus paintings at the Perth Museum and Art Gallery

Perth Art Gallery is the principal art gallery and exhibition space in the city of Perth, Scotland. It is located partly in the Marshall Monument, named in memory of Thomas Hay Marshall, a former provost of Perth.

The building was formerly know ...

in Perth, Scotland, donated by Charles McIntosh. In 1967, the mycologist W. P. K. Findlay included many of Potter's beautifully accurate fungus drawings in his ''Wayside & Woodland Fungi'', thereby fulfilling her desire to one day have her fungus drawings published in a book. In 1997, the Linnean Society issued a posthumous apology to Potter for the sexism displayed in its handling of her research.

Artistic and literary career

Potter's artistic and literary interests were deeply influenced by fairy tales and fantasy. She was a student of the classic fairy tales of Western Europe as well as stories from the

Potter's artistic and literary interests were deeply influenced by fairy tales and fantasy. She was a student of the classic fairy tales of Western Europe as well as stories from the Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

, John Bunyan

John Bunyan (; 1628 – 31 August 1688) was an English writer and preacher. He is best remembered as the author of the Christian allegory ''The Pilgrim's Progress'', which also became an influential literary model. In addition to ''The Pilgrim' ...

's ''The Pilgrim's Progress

''The Pilgrim's Progress from This World, to That Which Is to Come'' is a 1678 Christian allegory written by John Bunyan. It is commonly regarded as one of the most significant works of Protestant devotional literature and of wider early moder ...

'' and Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe (; June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) was an American author and Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and wrote the popular novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (185 ...

's ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two Volume (bibliography), volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans ...

''. She grew up with ''Aesop's Fables

Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a Slavery in ancient Greece, slave and storyteller who lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 Before the Common Era, BCE. Of varied and unclear origins, the stor ...

'', the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm

The Brothers Grimm ( or ), Jacob Grimm, Jacob (1785–1863) and Wilhelm Grimm, Wilhelm (1786–1859), were Germans, German academics who together collected and published folklore. The brothers are among the best-known storytellers of Oral tradit ...

and Hans Christian Andersen

Hans Christian Andersen ( , ; 2 April 1805 – 4 August 1875) was a Danish author. Although a prolific writer of plays, travelogue (literature), travelogues, novels, and poems, he is best remembered for his literary fairy tales.

Andersen's fai ...

, Charles Kingsley

Charles Kingsley (12 June 1819 – 23 January 1875) was a broad church priest of the Church of England, a university professor, social reformer, historian, novelist and poet. He is particularly associated with Christian socialism, the workin ...

's '' The Water Babies'', the folk tales and mythology of Scotland, the German Romantics

German Romanticism () was the dominant intellectual movement of German-speaking countries in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, influencing philosophy, aesthetics, literature, and criticism. Compared to English Romanticism, the German var ...

, Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

, and the romances of Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

. As a young child, before the age of eight, Edward Lear

Edward Lear (12 May 1812 – 29 January 1888) was an English artist, illustrator, musician, author and poet, who is known mostly for his literary nonsense in poetry and prose and especially his limerick (poetry), limericks, a form he popularised. ...

's '' A Book of Nonsense'', including the much-loved ''The Owl and the Pussycat

"The Owl and the Pussy-Cat" is a nonsense verse, nonsense poem by Edward Lear, first published in 1870 in the American magazine ''Our Young Folks'' and again the following year in Lear's own book ''Nonsense Songs, Stories, Botany, and Alphabets ...

'', and Lewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet, mathematician, photographer and reluctant Anglicanism, Anglican deacon. His most notable works are ''Alice ...

's ''Alice in Wonderland

''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (also known as ''Alice in Wonderland'') is an 1865 English Children's literature, children's novel by Lewis Carroll, a mathematics university don, don at the University of Oxford. It details the story of a ...

'' had made their impression, although she later said of ''Alice'' that she was more interested in Tenniel's illustrations than what they were about.

The ''Brer Rabbit

Br'er Rabbit ( ; an abbreviation of ''Brother Rabbit'', also spelled Brer Rabbit) is a central figure in an oral tradition passed down by African-Americans of the Southern United States and African descendants in the Caribbean, notably Afro-Baha ...

'' stories of Joel Chandler Harris

Joel Chandler Harris (December 9, 1848 – July 3, 1908) was an American journalist and folklorist best known for his collection of Uncle Remus stories. Born in Eatonton, Georgia, where he served as an apprentice on a plantation during his t ...

had been family favourites, and she later studied his ''Uncle Remus

Uncle Remus is the fictional title character and narrator of a collection of African American folktales compiled and adapted by Joel Chandler Harris and published in book form in 1881. Harris was a journalist in post–Reconstruction era Atlant ...

'' stories and illustrated them. She studied book illustration from a young age and developed her own tastes, but the work of the picture book triumvirate Walter Crane

Walter Crane (15 August 184514 March 1915) was an English artist and book illustrator. He is considered to be the most influential, and among the most prolific, children's book creators of his generation and, along with Randolph Caldecott and Ka ...

, Kate Greenaway

Catherine Greenaway (17 March 18466 November 1901) was an English Victorian artist and writer, known for her

children's book illustrations. She received her education in graphic design and art between 1858 and 1871 from the Finsbury School of ...

and Randolph Caldecott

Randolph Caldecott ( ; 22 March 1846 – 12 February 1886) was a British artist and illustrator, born in Chester. The Caldecott Medal was named in his honour. He exercised his art chiefly in book illustrations. His abilities as an artist were pr ...

, the last an illustrator whose work was later collected by her father, was a great influence. Her earliest illustrations focused on traditional rhymes and stories like ''Cinderella

"Cinderella", or "The Little Glass Slipper", is a Folklore, folk tale with thousands of variants that are told throughout the world.Dundes, Alan. Cinderella, a Casebook. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988. The protagonist is a you ...

'', ''Sleeping Beauty

"Sleeping Beauty" (, or ''The Beauty Sleeping in the Wood''; , or ''Little Briar Rose''), also titled in English as ''The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods'', is a fairy tale about a princess curse, cursed by an evil fairy to suspended animation in fi ...

'', ''Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves

"Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves" () is a folk tale in Arabic added to the ''One Thousand and One Nights'' in the 18th century by its French translator Antoine Galland, who heard it from Syrian storyteller Hanna Diyab. As one of the most popul ...

'', ''Puss in Boots

"Puss in Boots" (; ; ; ) is a European fairy tale about an anthropomorphic cat who uses trickery and deceit to gain power, wealth, and the hand in marriage of a princess for his penniless and low-born master.

The oldest written telling version ...

'', and ''Little Red Riding Hood

"Little Red Riding Hood" () is a fairy tale by Charles Perrault about a young girl and a Big Bad Wolf. Its origins can be traced back to several pre-17th-century European Fable, folk tales. It was later retold in the 19th-century by the Broth ...

''. However, most often her illustrations were fantasies featuring her own pets: mice, rabbits, kittens, and guinea pigs.

In her teenage years, Potter was a regular visitor to the art galleries of London, particularly enjoying the summer and winter exhibitions at the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House in Piccadilly London, England. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its ...

in London. Her ''Journal'' reveals her growing sophistication as a critic as well as the influence of her father's friend, the artist Sir John Everett Millais

Sir John Everett Millais, 1st Baronet ( , ; 8 June 1829 – 13 August 1896) was an English painter and illustrator who was one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. He was a child prodigy who, aged eleven, became the youngest st ...

, who recognised Potter's talent of observation. Although Potter was aware of art and artistic trends, her drawing and her prose style were uniquely her own.

As a way to earn money in the 1890s, Potter printed Christmas cards of her own design, as well as cards for special occasions. These were her first commercially successful works as an illustrator. Mice and rabbits were the most frequent subject of her fantasy paintings. In 1890, the firm of Hildesheimer and Faulkner bought several of the drawings of her rabbit Benjamin Bunny

Benjamin ( ''Bīnyāmīn''; "Son of (the) right") blue letter bible: https://www.blueletterbible.org/lexicon/h3225/kjv/wlc/0-1/ H3225 - yāmîn - Strong's Hebrew Lexicon (kjv) was the younger of the two sons of Jacob and Rachel, and Jacob's twe ...

to illustrate verses by Frederic Weatherly

Frederic Edward Weatherly, KC (4 October 1848 – 7 September 1929) was an English lawyer, author, lyricist and broadcaster. He was christened and brought up using the name Frederick Edward Weatherly, and appears to have adopted the spelling 'F ...

titled ''A Happy Pair''. In 1893, the same printer bought several more drawings for Weatherly's ''Our Dear Relations'', another book of rhymes, and the following year Potter sold a series of frog illustrations and verses for ''Changing Pictures'', a popular annual offered by the art publisher Ernest Nister. Potter was pleased by this success and determined to publish her own illustrated stories.

Whenever Potter went on holiday to the Lake District

The Lake District, also known as ''the Lakes'' or ''Lakeland'', is a mountainous region and National parks of the United Kingdom, national park in Cumbria, North West England. It is famous for its landscape, including its lakes, coast, and mou ...

or Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, she sent letters to young friends, illustrating them with quick sketches. Many of these letters were written to the children of her former governess Annie Carter Moore, particularly to Moore's eldest son Noel, who was often ill. In September 1893, Potter was on holiday at Eastwood in Dunkeld

Dunkeld (, , from , "fort of the Caledonians") is a town in Perth and Kinross, Scotland. The location of a historic cathedral, it lies on the north bank of the River Tay, opposite Birnam. Dunkeld lies close to the geological Highland Boundar ...

, Perthshire. She had run out of things to say to Noel, and so she told him a story about "four little rabbits whose names were Flopsy, Mopsy, Cottontail, and Peter". It became one of the most famous children's letters ever written and the basis of Potter's future career as a writer-artist-storyteller.

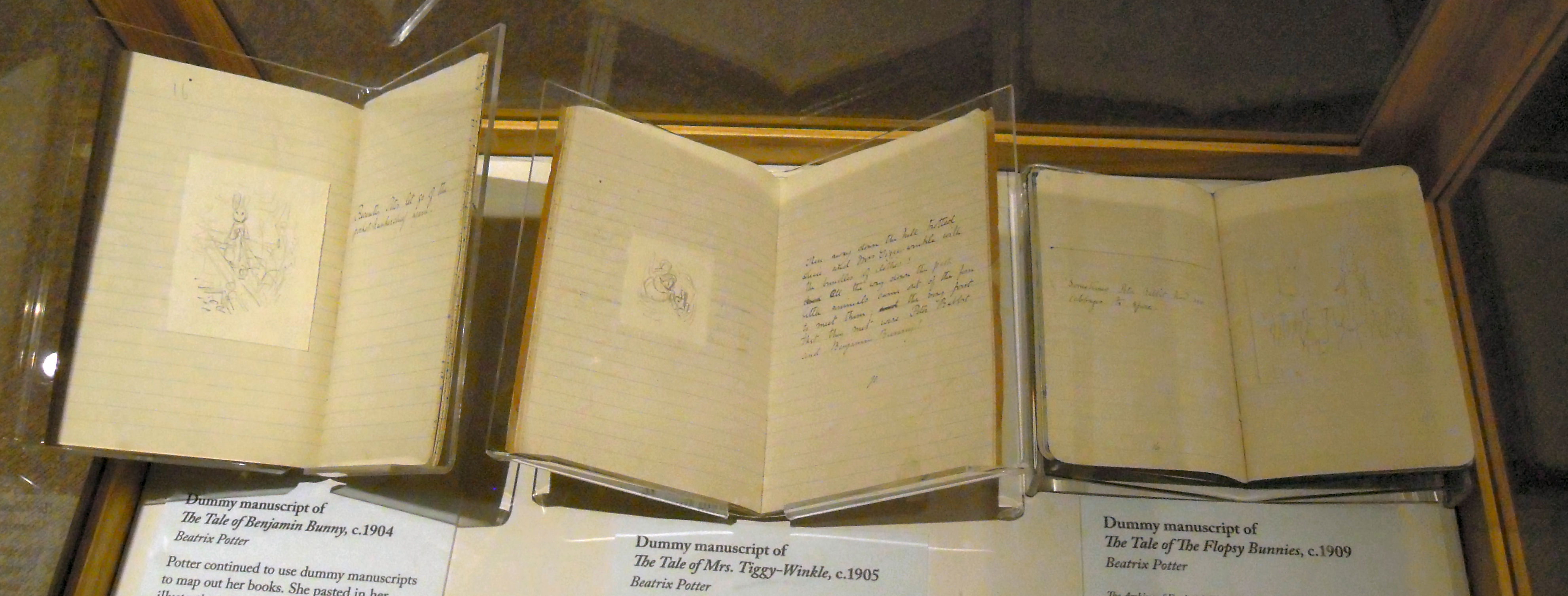

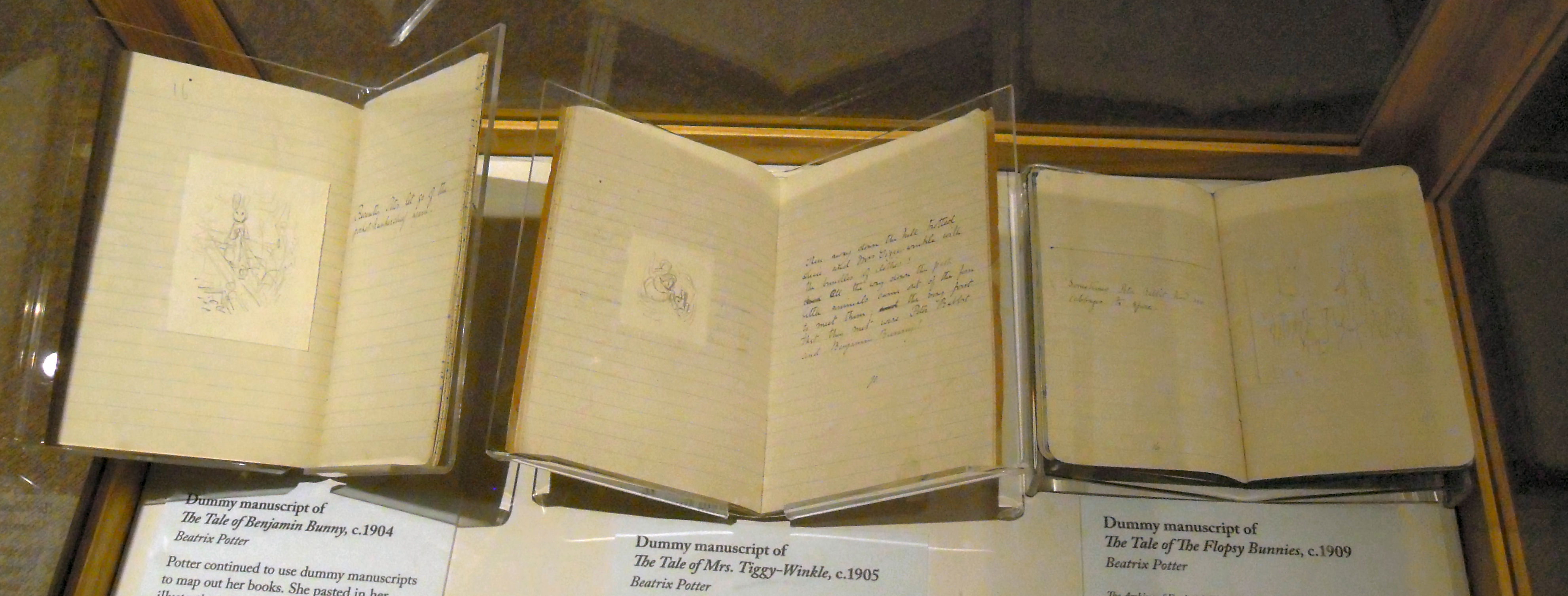

In 1900, Potter revised her tale about the four little rabbits, and fashioned a dummy book of it – it has been suggested, in imitation of

In 1900, Potter revised her tale about the four little rabbits, and fashioned a dummy book of it – it has been suggested, in imitation of Helen Bannerman

Helen Brodie Cowan Bannerman (' Watson; 25 February 1862 – 13 October 1946) was a Scottish children's writer. She is best known for her first book, '' Little Black Sambo'' (1899).

Life

Bannerman was born at 35 Royal Terrace, Edinburgh. She ...

's 1899 bestseller ''The Story of Little Black Sambo

''The Story of Little Black Sambo'' is a children's book written and illustrated by Scottish author Helen Bannerman and published by Grant Richards (publishing house), Grant Richards in October 1899. As one in a series of small-format books ca ...

''. Unable to find a buyer for the work, she published it for family and friends at her own expense in December 1901. It was drawn in black and white with a coloured frontispiece. Rawnsley had great faith in Potter's tale, recast it in didactic verse, and made the rounds of the London publishing houses. Frederick Warne & Co

Frederick Warne & Co. is a British publisher founded in 1865. It is known for children's books, particularly those of Beatrix Potter, and for its Observer's Books.

Warne is an imprint of Random House Children's Books and Penguin Random House, ...

had previously rejected the tale but, eager to compete in the booming small format children's book market, reconsidered and accepted the "bunny book" (as the firm called it) following the recommendation of their prominent children's book artist L. Leslie Brooke. The firm declined Rawnsley's verse in favour of Potter's original prose, and Potter agreed to colour her pen and ink illustrations, choosing the new Hentschel three-colour process to reproduce her watercolours.Hobbs 1989, p. 15

On 2 October 1902, ''

On 2 October 1902, ''The Tale of Peter Rabbit

''The Tale of Peter Rabbit'' is a children's book written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter that follows mischievous and disobedient young Peter Rabbit as he gets into, and is chased around, the garden of Mr. McGregor. He escapes and returns h ...

'' was published and became an immediate success. It was followed the next year by ''The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin

''The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin'' is a children's book written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter and first published by Frederick Warne & Co. in August 1903. The story is about an impertinent red squirrel named Nutkin and his narrow escape from ...

'' and ''The Tailor of Gloucester

''The Tailor of Gloucester'' is a Christmas Children's literature, children's book written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter, privately printed by the author in 1902, and published in a trade edition by Frederick Warne & Co. in October 1903. The ...

'', which had also first been written as picture letters to the Moore children. Working with Norman Warne

Norman Dalziel Warne (6 July 1868 – 25 August 1905) was the third son of publisher Frederick Warne, and joined his father's firm Frederick Warne & Co as an editor. In 1900, the company rejected Beatrix Potter's ''The Tale of Peter Rabbit' ...

as her editor, Potter published two or three little books each year: 23 books in all. The last book in this format was ''Cecily Parsley's Nursery Rhymes

''Cecily Parsley's Nursery Rhymes'' is a children's book written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter, and published by Frederick Warne & Co. in December 1922. The book is a compilation of traditional English nursery rhymes such as " Goosey Goosey ...

'' in 1922, a collection of favourite rhymes. Although ''The Tale of Little Pig Robinson

''The Tale of Little Pig Robinson'' is a children's book written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter as part of the Peter Rabbit series. The book contains eight chapters and numerous illustrations. Though the book was one of Potter's last public ...

'' was not published until 1930, it had been written much earlier. Potter continued creating her little books until after the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

when her energies were increasingly directed toward her farming, sheep-breeding, and land conservation.

The immense popularity of Potter's books was based on the lively quality of her illustrations, the non-didactic nature of her stories, the depiction of the rural countryside, and the imaginative qualities she lent to her animal characters.

Potter was also a canny businesswoman. As early as 1903, she made and patented a Peter Rabbit

Peter Rabbit is a fictional animal character in various children's stories by English author Beatrix Potter.

A mischievous, adventurous young rabbit who wears a blue jacket, he first appeared in ''The Tale of Peter Rabbit'' in 1902, and subseq ...

doll. It was followed by other merchandise over the years, including painting books, board games, wall-paper, figurines, baby blankets and china tea-sets. All were licensed by Frederick Warne & Co

Frederick Warne & Co. is a British publisher founded in 1865. It is known for children's books, particularly those of Beatrix Potter, and for its Observer's Books.

Warne is an imprint of Random House Children's Books and Penguin Random House, ...

and earned Potter an independent income, as well as immense profits for her publisher.

In 1905, Potter and Norman Warne

Norman Dalziel Warne (6 July 1868 – 25 August 1905) was the third son of publisher Frederick Warne, and joined his father's firm Frederick Warne & Co as an editor. In 1900, the company rejected Beatrix Potter's ''The Tale of Peter Rabbit' ...

became unofficially engaged. Potter's parents objected to the match because Warne was "in trade" and thus not socially suitable. The engagement lasted only one month—Warne died of pernicious anaemia

Pernicious anemia is a disease where not enough red blood cells are produced due to a deficiency of vitamin B12. Those affected often have a gradual onset. The most common initial symptoms are feeling tired and weak. Other symptoms may includ ...

at age 37. That same year, Potter used some of her income and a small inheritance from an aunt to buy Hill Top Farm

Hill Top is a 17th-century house in Near Sawrey near Hawkshead, in the English county of Cumbria. It is an example of Lakeland vernacular architecture with random stone walls and slate roof. The house was once the home of children's author and ...

in Near Sawrey

Near Sawrey and Far Sawrey are two neighbouring villages in the Furness area of Cumbria, England. Within the boundaries of the historic county of Lancashire, both are located in the Lake District between the village of Hawkshead and the lake ...

, located west of Lake Windermere

Windermere (historically Winder Mere) is a ribbon lake in Cumbria, England, and part of the Lake District. It is the largest lake in England by length, area, and volume, but considerably smaller than the List of lakes and lochs of the United Ki ...

in the English Lake District

The Lake District, also known as ''the Lakes'' or ''Lakeland'', is a mountainous region and National parks of the United Kingdom, national park in Cumbria, North West England. It is famous for its landscape, including its lakes, coast, and mou ...

. Potter and Warne may have hoped that Hill Top Farm would be their holiday home, but after Warne's death, Potter went ahead with its purchase as she had always wanted to own that farm and live in "that charming village".

Country life and marriage

The tenant farmer John Cannon and his family agreed to stay on to manage the farm for her while she made physical improvements and learned the techniques of fell farming and of raising livestock, including pigs, cows and chickens; the following year she added sheep. Realising she needed to protect her boundaries, she sought advice from W.H. Heelis & Son, a local firm of solicitors with offices in nearby

The tenant farmer John Cannon and his family agreed to stay on to manage the farm for her while she made physical improvements and learned the techniques of fell farming and of raising livestock, including pigs, cows and chickens; the following year she added sheep. Realising she needed to protect her boundaries, she sought advice from W.H. Heelis & Son, a local firm of solicitors with offices in nearby Hawkshead

Hawkshead is a village and civil parish in Westmorland and Furness, Cumbria, England. It lies within the Lake District National Park and was historically part of Lancashire. The parish includes the hamlets of Hawkshead Hill, to the north west, ...

. With William Heelis acting for her, she bought contiguous pasture, and in 1909 the Castle Farm across the road from Hill Top Farm. She visited Hill Top at every opportunity, and her books written during this period (such as ''The Tale of Ginger and Pickles

''The Tale of Ginger and Pickles'' (originally, ''Ginger and Pickles'') is a children's book written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter, and first published by Frederick Warne & Co. in 1909. The book tells of two shopkeepers who extend unlimited ...

'', about the local shop in Near Sawrey and '' The Tale of Mrs. Tittlemouse'', a wood mouse) reflect her increasing participation in village life and her delight in country living.

Owning and managing these working farms required routine collaboration with the widely respected William Heelis. By the summer of 1912, Heelis had proposed marriage and Potter had accepted; although she did not immediately tell her parents, who once again disapproved because Heelis was only a country solicitor. Potter and Heelis were married on 15 October 1913 in London at St Mary Abbots

St Mary Abbots is a Church (building), church located on Kensington High Street and the corner of Kensington Church Street in London W8.

The present church structure was built in 1872 to the designs of Sir George Gilbert Scott, who combined ne ...

in Kensington

Kensington is an area of London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, around west of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up by Kensingt ...

. The couple moved immediately to Near Sawrey

Near Sawrey and Far Sawrey are two neighbouring villages in the Furness area of Cumbria, England. Within the boundaries of the historic county of Lancashire, both are located in the Lake District between the village of Hawkshead and the lake ...

, residing at Castle Cottage, the renovated farmhouse on Castle Farm, which was large. Hill Top remained a working farm but was now remodelled to allow for the tenant family and Potter's private studio and workshop. At last her own woman, Potter settled into the partnerships that shaped the rest of her life: her country solicitor husband and his large family, her farms, the Sawrey community and the predictable rounds of country life. ''The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck

''The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck'' is a children's book written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter and first published by Frederick Warne & Co. in 1908. The protagonist Jemima Puddle-Duck first appeared in '' The Tale of Tom Kitten''.

Origins

...

'' and ''The Tale of Tom Kitten

''The Tale of Tom Kitten'' is a children's book, written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter. It was released by Frederick Warne & Co. in September 1907. The tale is about manners and how children react to them. Tabitha Twitchit, a cat, invites f ...

'' are representative of Hill Top Farm and her farming life and reflect her happiness with her country life.

Her father, Rupert Potter, died in 1914, and with the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Potter persuaded her mother to move to the Lake District, renting her a property in Sawrey. Finding life in Sawrey dull, Helen Potter soon moved to Lindeth Howe (now a 34-bedroomed hotel), a large house the Potters had previously rented for the summer in Bowness, on the other side of Lake Windermere. Potter continued to write stories for Frederick Warne & Co and fully participated in country life. She established a nursing trust for local villages and served on various committees and councils responsible for footpaths and other rural issues.

Sheep farming

Soon after acquiring Hill Top Farm, Potter became keenly interested in the breeding and raising of Herdwick sheep, the indigenous fell sheep. In 1923 she bought a large sheep farm in the Troutbeck Valley called Troutbeck Park Farm, formerly a deer park, restoring its land with thousands of Herdwick sheep. This established her as one of the major Herdwick sheep farmers in the county. She was admired by her shepherds and farm managers for her willingness to experiment with the latest biological remedies for the common diseases of sheep, and for her employment of the best shepherds, sheep breeders, and farm managers. By the late 1920s, Potter and her Hill Top farm manager Tom Storey had made a name for their prize-winning Herdwick flock, which took many prizes at the local agricultural shows, where Potter was often asked to serve as a judge. In 1942 she became President-elect of the Herdwick Sheepbreeders' Association, the first time a woman had been elected, but died before taking office.Welsh language

In one of her diary entries whilst travelling through Wales, Potter complained about theWelsh language

Welsh ( or ) is a Celtic languages, Celtic language of the Brittonic languages, Brittonic subgroup that is native to the Welsh people. Welsh is spoken natively in Wales by about 18% of the population, by some in England, and in (the Welsh c ...

. She wrote "Machynlleth

Machynlleth () is a market town, community and electoral ward in Powys, Wales and within the historic boundaries of Montgomeryshire. It is in the Dyfi Valley at the intersection of the A487 and the A489 roads. At the 2001 Census it had a po ...

, wretched town, hardly a person could speak English", continuing "Welsh seem a pleasant intelligent race, but I should think awkward to live with... the language is past description."

Lake District conservation

Potter had been a disciple of the land conservation and preservation ideals of her long-time friend and mentor, Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley, the first secretary and founding member of theNational Trust

The National Trust () is a heritage and nature conservation charity and membership organisation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Trust was founded in 1895 by Octavia Hill, Sir Robert Hunter and Hardwicke Rawnsley to "promote the ...

. According to the National Trust, "she supported the efforts of the National Trust to preserve not just the places of extraordinary beauty but also those heads of valleys and low grazing lands that would be irreparably ruined by development." Potter was also an authority on the traditional Lakeland crafts and period furniture, as well as local stonework. She restored and preserved the farms that she bought or managed, making sure that each farm house had in it a piece of antique Lakeland furniture. Potter was interested in preserving not only the Herdwick sheep but also the way of life of fell farming. In 1930 the Heelises became partners with the National Trust in buying and managing the fell farms included in the large Monk Coniston Estate.

The estate was composed of many farms spread over a wide area of north-western Lancashire, including the Tarn Hows

Tarn Hows is an area of the Lake District National Park in North West England, It contains a picturesque tarn, approximately northeast of Coniston and about northwest of Hawkshead. It is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the ...

. Potter was the ''de facto'' estate manager for the Trust for seven years until the National Trust could afford to repurchase most of the property from her. Potter's stewardship of these farms earned her full regard, but she was not without her critics, not the least of which were her contemporaries who felt she used her wealth and the position of her husband to acquire properties in advance of their being made public. She was notable in observing the problems of afforestation

Afforestation is the establishment of a forest or stand of trees in an area where there was no recent tree cover. There are three types of afforestation: natural Regeneration (biology), regeneration, agroforestry and Tree plantation, tree plan ...

, preserving the intact grazing lands, and husbanding the quarries and timber on these farms. All her farms were stocked with Herdwick sheep and frequently with Galloway cattle

The Galloway is a Scottish breed of beef cattle, named after the Galloway region of Scotland, where it originated during the seventeenth century.

It is usually black, is of average size, is naturally polled and has a thick coat suitable for ...

.

Later life

Potter continued to write stories and to draw, although mostly for her own pleasure. In 1922, ''

Potter continued to write stories and to draw, although mostly for her own pleasure. In 1922, ''Cecily Parsley's Nursery Rhymes

''Cecily Parsley's Nursery Rhymes'' is a children's book written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter, and published by Frederick Warne & Co. in December 1922. The book is a compilation of traditional English nursery rhymes such as " Goosey Goosey ...

'', a collection of traditional English nursery rhyme

A nursery rhyme is a traditional poem or song for children in Britain and other European countries, but usage of the term dates only from the late 18th/early 19th century. The term Mother Goose rhymes is interchangeable with nursery rhymes.

Fr ...

s, was published. Her books in the late 1920s included the semi-autobiographical ''The Fairy Caravan

''The Fairy Caravan'' is a children's book written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter and first published in 1929 by Alexander McKay in Philadelphia. As noted by Leslie Linder, "Potter did not wish for an English edition of ''The Fairy Caravan'' ...

'', a fanciful tale set in her beloved Troutbeck fells. It was published only in the US during Potter's lifetime, and not until 1952 in the UK. ''Sister Anne'', Potter's version of the story of Bluebeard

"Bluebeard" ( ) is a French Folklore, folktale, the most famous surviving version of which was written by Charles Perrault and first published by Barbin in Paris in 1697 in . The tale is about a wealthy man in the habit of murdering his wives an ...

, was written for her American readers, but illustrated by Katharine Sturges. A final folktale, ''Wag by Wall'', was published posthumously by ''The Horn Book Magazine

''The Horn Book Magazine'', founded in Boston in 1924, is the oldest bimonthly magazine dedicated to reviewing children's literature. It began as a "suggestive purchase list" prepared by Bertha Mahony and Elinor Whitney Field, proprietors of t ...

'' in 1944. Potter was a generous patron of the Girl Guides

Girl Guides (or Girl Scouts in the United States and some other countries) are organisations within the Scout Movement originally and largely still for girls and women only. The Girl Guides began in 1910 with the formation of Girlguiding, The ...

, whose troops she allowed to make their summer encampments on her land, and whose company she enjoyed as an older woman.

Potter and William Heelis enjoyed a happy marriage of thirty years, continuing their farming and preservation efforts throughout the hard days of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Although they were childless, Potter played an important role in William's large family, particularly enjoying her relationship with several nieces whom she helped educate, and giving comfort and aid to her husband's brothers and sisters.

Potter died of complications from pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

and heart disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is any disease involving the heart or blood vessels. CVDs constitute a class of diseases that includes: coronary artery diseases (e.g. angina pectoris, angina, myocardial infarction, heart attack), heart failure, ...

on 22 December 1943 at Castle Cottage, and her remains were cremated at Carleton Crematorium, Blackpool. She left nearly all her property to the National Trust, including over of land, sixteen farms, cottages and herds of cattle and Herdwick sheep. Hers was the largest gift at that time to the National Trust, and it enabled the preservation of the land now included in the Lake District National Park

The Lake District, also known as ''the Lakes'' or ''Lakeland'', is a mountainous region and National parks of the United Kingdom, national park in Cumbria, North West England. It is famous for its landscape, including its lakes, coast, and mou ...

and the continuation of fell farming. The central office of the National Trust in Swindon

Swindon () is a town in Wiltshire, England. At the time of the 2021 Census the population of the built-up area was 183,638, making it the largest settlement in the county. Located at the northeastern edge of the South West England region, Swi ...

was named "Heelis" in 2005 in her memory. William Heelis continued his stewardship of their properties and of her literary and artistic work for the twenty months he survived her. When he died in August 1945, he left the remainder to the National Trust.

Legacy

Potter left almost all the original illustrations for her books to the National Trust. The copyright to her stories and merchandise was then given to her publisher Frederick Warne & Co, now a division of the

Potter left almost all the original illustrations for her books to the National Trust. The copyright to her stories and merchandise was then given to her publisher Frederick Warne & Co, now a division of the Penguin Group

Penguin Group is a British trade book publisher and part of Penguin Random House, which is owned by the German media company, media Conglomerate (company), conglomerate Bertelsmann. The new company was created by a Mergers and acquisitions, mer ...

. On 1 January 2014, the copyright expired in the UK and other countries with a 70-years-after-death limit. Hill Top Farm was opened to the public by the National Trust in 1946; her artwork was displayed there until 1985 when it was moved to William Heelis's former law offices in Hawkshead

Hawkshead is a village and civil parish in Westmorland and Furness, Cumbria, England. It lies within the Lake District National Park and was historically part of Lancashire. The parish includes the hamlets of Hawkshead Hill, to the north west, ...

, also owned by the National Trust as the Beatrix Potter Gallery.

Potter gave her folios of mycological drawings to the Armitt Library and Museum in Ambleside

Ambleside is a town in the civil parish of Lakes and the Westmorland and Furness district of Cumbria, England. Within the boundaries of the historic county of Westmorland and located in the Lake District National Park, the town sits at the ...

before her death. ''The Tale of Peter Rabbit'' is owned by Warne, ''The Tailor of Gloucester'' by the Tate Gallery

Tate is an institution that houses, in a network of four art galleries, the United Kingdom's national collection of British art, and international modern and contemporary art. It is not a government institution, but its main sponsor is the UK ...

, and ''The Tale of the Flopsy Bunnies'' by the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

.

In 1903, Potter created the first Peter Rabbit

Peter Rabbit is a fictional animal character in various children's stories by English author Beatrix Potter.

A mischievous, adventurous young rabbit who wears a blue jacket, he first appeared in ''The Tale of Peter Rabbit'' in 1902, and subseq ...

soft toy

A stuffed toy is a toy with an outer fabric sewn from a textile and stuffed with flexible material. They are known by many names, such as plush toys, plushies, lovies and stuffies; in Britain and Australia, they may also be called soft toys ...

and registered him at the Patent Office

A patent office is a governmental or intergovernmental organization which controls the issue of patents. In other words, "patent offices are government bodies that may grant a patent or reject the patent application based on whether the applicati ...

in London, making Peter the oldest licensed fictional character. Merchandise of Peter and other Potter characters have been sold at Harrods

Harrods is a Listed building, Grade II listed luxury department store on Brompton Road in Knightsbridge, London, England. It was designed by C. W. Stephens for Charles Digby Harrod, and opened in 1905; it replaced the first store on the ground ...

department store in London since at least 1910 when the range first appeared in their catalogues. Along with her writing Potter would continue to oversee merchandising and licensing opportunities for her characters. On her legacy, Nicholas Tucker in ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'' writes, "she was the first author to license fictional characters to a range of toys and household objects still on sale today". In an article by the '' Smithsonian'' magazine titled, ''How Beatrix Potter Invented Character Merchandising'', Joy Lanzendorfer writes, "Potter was also an entrepreneur and a pioneer in licensing and merchandising literary characters. Potter built a retail empire out of her “bunny book” that is worth $500 million today. In the process, she created a system that continues to benefit all licensed characters, from Mickey Mouse to Harry Potter."

The largest public collection of her letters and drawings is the Leslie Linder Bequest and Leslie Linder Collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum

The Victoria and Albert Museum (abbreviated V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.8 million objects. It was founded in 1852 and named after Queen ...

in London. (Linder was the collector who—after five years of work—finally transcribed Potter's early journal, originally written in code.) In the United States, the largest public collections are those in the Rare Book Department of the Free Library of Philadelphia

The Free Library of Philadelphia is the public library system that serves the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is the 16th-largest public library system in the United States. The Free Library of Philadelphia is a non-Mayoral agency of the ...

, and the Cotsen Children's Library at Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial ...

.

In 2015, a manuscript for an unpublished book was discovered by Jo Hanks, a publisher at Penguin Random House Children's Books, in the Victoria and Albert Museum archive. The book '' The Tale of Kitty-in-Boots'', with illustrations by Quentin Blake

Sir Quentin Saxby Blake (born 16 December 1932) is an English cartoonist, caricaturist, illustrator and children's writer. He has illustrated over 300 books, including 18 written by Roald Dahl, which are among his most popular works. For his l ...

, was published 1 September 2016, to mark the 150th anniversary of Potter's birth. Also in 2016, Peter Rabbit was depicted on the reverse of a British fifty pence coin, and Peter along with other Potter characters featured on a series of UK postage stamps issued by the Royal Mail

Royal Mail Group Limited, trading as Royal Mail, is a British postal service and courier company. It is owned by International Distribution Services. It operates the brands Royal Mail (letters and parcels) and Parcelforce Worldwide (parcels) ...

.

In 2017, ''The Art of Beatrix Potter: Sketches, Paintings, and Illustrations'' by Emily Zach was published after San Francisco publisher Chronicle Books

Chronicle Books is a San Francisco–based American publishing company that publishes books for both adults and children.

History

The company was established in 1967 by Phelps Dewey, an executive with Chronicle Publishing Company, then-publish ...

decided to mark the 150th anniversary of Beatrix Potter's birth by showing that she was "far more than a 19th-century weekend painter. She was an artist of astonishing range."

In December 2017, the asteroid 13975 Beatrixpotter, discovered by Belgian astronomer Eric Elst

Eric Walter Elst (30 November 1936 – 2 January 2022) was a Belgian astronomer at the Royal Observatory of Belgium in Uccle and a prolific discoverer of asteroids. The Minor Planet Center ranks him among the top 10 discoverers of minor planets wi ...

in 1992, was renamed in her memory. In 2022, an exhibition, ''Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature'', was held at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Research for the exhibition identified the man's court waistcoat c. 1780s, which inspired Potter's sketch in ''The Tailor of Gloucester''.

Analysis

There are many interpretations of Potter's literary work, the sources of her art, and her life and times. These include critical evaluations of her corpus of children's literature andModernist

Modernism was an early 20th-century movement in literature, visual arts, and music that emphasized experimentation, abstraction, and Subjectivity and objectivity (philosophy), subjective experience. Philosophy, politics, architecture, and soc ...

interpretations of Humphrey Carpenter

Humphrey William Bouverie Carpenter (29 April 1946 – 4 January 2005) was an English biographer, writer, and radio broadcaster. He is known especially for his biographies of J. R. R. Tolkien and other members of the literary society the Inkli ...

and Katherine Chandler. Judy Taylor, ''That Naughty Rabbit: Beatrix Potter and Peter Rabbit'' (rev. 2002) tells the story of the first publication and many editions.

Potter's country life, her farming and role as a landscape preservationist are discussed in the work of Matthew Kelly, ''The Women Who Saved the English Countryside'' (2022). See also Susan Denyer and authors in the publications of The National Trust

The National Trust () is a heritage and nature conservation charity and membership organisation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Trust was founded in 1895 by Octavia Hill, Sir Robert Hunter and Hardwicke Rawnsley to "promote the ...

, such as ''Beatrix Potter at Home in the Lake District'' (2004).

Potter's work as a scientific illustrator and her work in mycology are discussed in Linda Lear

Linda Jane Lear (born February 16, 1940) is an American historian of science and biographer.

Life and career

A native of Pittsburgh, Lear received her A.B. from Connecticut College in 1962, following with an A.M. from Columbia University in 1964; ...

's books ''Beatrix Potter: A Life in Nature'' (2006) and ''Beatrix Potter: The Extraordinary Life of a Victorian Genius'' (2008).

Adaptations

In 1971, a ballet film was released, ''The Tales of Beatrix Potter

''The Tales of Beatrix Potter'' (US title: ''Peter Rabbit and Tales of Beatrix Potter'') is a 1971 ballet film based on the children's stories of English author and illustrator Beatrix Potter. The film was directed by Reginald Mills, choreograph ...

'', directed by Reginald Mills, set to music by John Lanchbery

John Arthur Lanchbery OBE (15 May 1923 – 27 February 2003) was an English-Australian composer and conductor, famous for his ballet arrangements. He served as the Principal Conductor of the Royal Ballet from 1959 to 1972, Principal Conductor o ...

with choreography by Frederick Ashton

Sir Frederick William Mallandaine Ashton (17 September 190418 August 1988) was a British ballet dancer and choreographer. He also worked as a director and choreographer in opera, film and revue.

Determined to be a dancer despite the oppositio ...

, and performed in character costume by members of the Royal Ballet

The Royal Ballet is a British internationally renowned classical ballet company, based at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, London, England. The largest of the five major ballet companies in Great Britain, the Royal Ballet was founded ...

and the Royal Opera House

The Royal Opera House (ROH) is a theatre in Covent Garden, central London. The building is often referred to as simply Covent Garden, after a previous use of the site. The ROH is the main home of The Royal Opera, The Royal Ballet, and the Orch ...

orchestra. The ballet of the same name has been performed by other dance companies around the world.

In 1992, Potter's children's book ''The Tale of Benjamin Bunny

''The Tale of Benjamin Bunny'' is a children's book written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter, and first published by Frederick Warne & Co. in September 1904. The book is a sequel to ''The Tale of Peter Rabbit'' (1902), and tells of Peter's retur ...

'' was featured in the film ''Lorenzo's Oil

''Lorenzo's Oil'' is a 1992 drama film directed and co-written by George Miller. It is based on the true story of Augusto and Michaela Odone, parents who search for a cure for their son Lorenzo's adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), leading to the d ...

''.

Potter is also featured in Susan Wittig Albert

Susan Wittig Albert, also known by the pen names Robin Paige and Carolyn Keene, is an American mystery writer from Vermilion County, Illinois, United States. Albert was an academic and the first female vice president of Southwest Texas State U ...

's series of light mysteries called ''The Cottage Tales of Beatrix Potter''. The first of the eight-book series is ''Tale of Hill Top Farm'' (2004), which deals with Potter's life in the Lake District

The Lake District, also known as ''the Lakes'' or ''Lakeland'', is a mountainous region and National parks of the United Kingdom, national park in Cumbria, North West England. It is famous for its landscape, including its lakes, coast, and mou ...

and the village of Near Sawrey

Near Sawrey and Far Sawrey are two neighbouring villages in the Furness area of Cumbria, England. Within the boundaries of the historic county of Lancashire, both are located in the Lake District between the village of Hawkshead and the lake ...

between 1905 and 1913.

In film

In 1982, theBBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

produced ''The Tale of Beatrix Potter''. This dramatization of her life was written by John Hawkesworth, directed by Bill Hayes, and starred Holly Aird

Imogen Holly Aird (born 18 May 1969) is an English television actress. She was born in Aldershot, Hampshire.

Career

Aird was spotted by a casting director at age nine whilst at Bush Davies Ballet School and starred in the 1980 dramatisation o ...

and Penelope Wilton

Dame Penelope Alice Wilton (born 3 June 1946) is an English actress. She was formerly married to fellow actor Sir Ian Holm and, as she has not remarried, retains her married style of Lady Holm.

Wilton is known for starring opposite Richard ...

as the young and adult Potter, respectively. ''The World of Peter Rabbit and Friends

''The World of Peter Rabbit and Friends'' is a British animated anthology television series based on the works of Beatrix Potter, featuring Peter Rabbit and other anthropomorphic animal characters created by Potter. 14 of Potter's stories were a ...

'', a TV series based on nine of her twenty-four stories, starred actress Niamh Cusack

Niamh Cusack ( ; born 20 October 1959) is an Irish actress. Born into a family with deep roots in the performing arts, she has performed extensively with the Royal Shakespeare Company, the Royal National Theatre, and other prominent theatre ens ...

as Beatrix Potter.

In 1993, Weston Woods Studios

Weston Woods Studios (or simply Weston Woods) is an American production company that makes audio and short films based on well-known books for children.

It was founded in 1953 by Morton Schindel in Weston, Connecticut, and named after the wooded ...

made an almost hour non-story film called "Beatrix Potter: Artist, Storyteller, and Countrywoman" with narration by Lynn Redgrave

Lynn Rachel Redgrave (8 March 1943 – 2 May 2010) was a British and American actress. During a career that spanned five decades, she won two Golden Globe Awards and was nominated for two Academy Awards, four British Academy Film Awards, two Em ...

. In 2006, Chris Noonan

Chris Noonan (born 14 November 1952) is an Australian filmmaker and actor. He is best known for the family film '' Babe'' (1995), for which he was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director and Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay. ...

directed ''Miss Potter

''Miss Potter'' is a 2006 biographical drama film directed by Chris Noonan. It is based on the life of children's author and illustrator Beatrix Potter, and combines stories from her own life with animated sequences featuring characters from her ...