HMS Nelson (28) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Nelson'' (

The

The  The ''Nelson''s were built with two director-control towers fitted with

The ''Nelson''s were built with two director-control towers fitted with

The top of the armoured citadel of the ''Nelson''-class ships was protected by an armoured deck that rested on the top of the belt armour. Its non-cemented armour plates ranged in thickness from over the main-gun magazines to over the propulsion machinery spaces and the secondary magazines. Aft of the citadel was an armoured deck thick at the level of the lower edge of the belt armour that extended almost to the end of the

The top of the armoured citadel of the ''Nelson''-class ships was protected by an armoured deck that rested on the top of the belt armour. Its non-cemented armour plates ranged in thickness from over the main-gun magazines to over the propulsion machinery spaces and the secondary magazines. Aft of the citadel was an armoured deck thick at the level of the lower edge of the belt armour that extended almost to the end of the

On 11 July, the ship was assigned to escort Convoy WS.9C that consisted of merchantmen that were to pass into the Mediterranean to deliver troops and supplies to Malta. Once they passed

On 11 July, the ship was assigned to escort Convoy WS.9C that consisted of merchantmen that were to pass into the Mediterranean to deliver troops and supplies to Malta. Once they passed

''Nelson'' departed Gibraltar on 31 October for England to rejoin the Home Fleet. She provided naval gunfire support during the Normandy landings in June 1944, but was badly damaged after hitting two mines on the 18th. Temporarily repaired in Portsmouth, the ship was sent to the

''Nelson'' departed Gibraltar on 31 October for England to rejoin the Home Fleet. She provided naval gunfire support during the Normandy landings in June 1944, but was badly damaged after hitting two mines on the 18th. Temporarily repaired in Portsmouth, the ship was sent to the

Maritimequest HMS Nelson Photo Gallery

{{DEFAULTSORT:Nelson (28) Nelson-class battleships Ships built by Armstrong Whitworth Ships built on the River Tyne 1925 ships World War II battleships of the United Kingdom Maritime incidents in 1934

pennant number

In the Royal Navy and other navies of Europe and the Commonwealth of Nations, ships are identified by pennant number (an internationalisation of ''pendant number'', which it was called before 1948). Historically, naval ships flew a flag that iden ...

: 28) was the name ship of her class of two battleships built for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

in the 1920s. They were the first battleships built to meet the limitations of the Washington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting Navy, naval construction. It was negotiated at ...

of 1922. Entering service in 1927, the ship spent her peacetime career with the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

and Home Fleet

The Home Fleet was a fleet of the Royal Navy that operated from the United Kingdom's territorial waters from 1902 with intervals until 1967. In 1967, it was merged with the Mediterranean Fleet creating the new Western Fleet.

Before the First ...

s, usually as the fleet flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

. During the early stages of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, she searched for German commerce raider

Commerce raiding is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than engaging its combatants or enforcing a blockade against them. Privateering is a fo ...

s, missed participating in the Norwegian Campaign after she was badly damaged by a mine in late 1939, and escorted convoys in the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

.

In mid-1941 ''Nelson'' escorted several convoys to Malta before being torpedoed in September. After repairs she resumed doing so before supporting the British invasion of French Algeria

French Algeria ( until 1839, then afterwards; unofficially ; ), also known as Colonial Algeria, was the period of History of Algeria, Algerian history when the country was a colony and later an integral part of France. French rule lasted until ...

during Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8–16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa whil ...

in late 1942. The ship covered the invasions of Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

(Operation Husky

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Man ...

) and Italy (Operation Avalanche

Operation Avalanche was the codename for the Allied landings near the port of Salerno, executed on 9 September 1943, part of the Allied invasion of Italy during World War II. The Italians withdrew from the war the day before the invasion, but ...

) in mid-1943 while bombarding coastal defences during Operation Baytown

Operation Baytown was an Allied amphibious landing on the mainland of Italy that took place on 3 September 1943, part of the Allied invasion of Italy, itself part of the Italian Campaign, during the Second World War.

Planning

The attack wa ...

. During the Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on 6 June 1944 of the Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during the Second World War. Codenamed Operation Neptune and ...

in June 1944, ''Nelson'' provided naval gunfire support

Naval gunfire support (NGFS), also known as naval surface fire support (NSFS), or shore bombardment, is the use of naval artillery to provide fire support for amphibious assault and other troops operating within their range. NGFS is one of seve ...

before she struck a mine and spent the rest of the year under repair. The ship was transferred to the Eastern Fleet

Eastern or Easterns may refer to:

Transportation

Airlines

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

* Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 192 ...

in mid-1945 and returned home a few months after the Japanese surrender

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, ending the war. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) was incapable of condu ...

in September to serve as the flagship of the Home Fleet. She became a training ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old hulks used to house class ...

in early 1946 and was reduced to reserve in late 1947. ''Nelson'' was scrapped

Scrap consists of recyclable

Recycling is the process of converting waste materials into new materials and objects. This concept often includes the recovery of energy from waste materials. The recyclability of a material depends on i ...

two years later after being used as a target for bomb tests.

Background and description

The ''Nelson''-class battleship was essentially a smaller, battleship version of the G3 battlecruiser which had been cancelled for exceeding the constraints of the 1922Washington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting Navy, naval construction. It was negotiated at ...

. The design, which had been approved six months after the treaty was signed, had a main armament of guns to match the firepower of the American and Japanese es in the battleline in a ship displacing no more than .

''Nelson'' had a length between perpendiculars

Length between perpendiculars (often abbreviated as p/p, p.p., pp, LPP, LBP or Length BPP) is the length of a ship along the summer load line from the forward surface of the stem, or main bow perpendicular member, to the after surface of the ste ...

of and an overall length

The overall length (OAL) of an ammunition cartridge is a measurement from the base of the brass shell casing to the tip of the bullet, seated into the brass casing. Cartridge overall length, or "COL", is important to safe functioning of reloads i ...

of , a beam of , and a draught of at mean standard load. She displaced at standard load and at deep load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into weig ...

. Her crew numbered 1,361 officers and ratings when serving as a flagship and 1,314 as a private ship

Private ship is a term used in the Royal Navy to describe that status of a commissioned warship in active service that is not currently serving as the flagship of a flag officer (i.e., an admiral or commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Com ...

.Burt, p. 348 The ship was powered by two sets of Brown-Curtis geared steam turbine

A steam turbine or steam turbine engine is a machine or heat engine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work utilising a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Sir Charles Par ...

s, each driving one shaft, using steam from eight Admiralty 3-drum boilers. The turbines were rated at and intended to give the ship a maximum speed of 23 knots. During her sea trial

A sea trial or trial trip is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a "shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on op ...

s on 26 May 1927, ''Nelson'' reached a top speed of from . The ship carried enough fuel oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil (bunker fuel), marine f ...

to give her a range of at a cruising speed of .

Armament and fire control

The

The main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a naval gun or group of guns used in volleys, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, th ...

of the ''Nelson''-class ships consisted of nine breech-loading

A breechloader is a firearm in which the user loads the ammunition from the breech end of the barrel (i.e., from the rearward, open end of the gun's barrel), as opposed to a muzzleloader, in which the user loads the ammunition from the ( muzzle ...

(BL) 16-inch guns in three turrets forward of the superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

. Designated 'A', 'B' and 'C' from front to rear, 'B' turret superfired over the others. Their secondary armament

Secondary armaments are smaller, faster-firing weapons that are typically effective at a shorter range than the main battery, main (heavy) weapons on military systems, including battleship- and cruiser-type warships, tanks/armored personnel c ...

consisted of a dozen BL Mk XXII guns in twin-gun turrets aft of the superstructure, three turrets on each broadside. Their anti-aircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare (AAW) is the counter to aerial warfare and includes "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It encompasses surface-based, subsurface ( submarine-launched), and air-ba ...

(AA) armament consisted of six quick-firing (QF) Mk VIII guns in unshielded single mounts and eight QF 2-pounder () guns in single mounts. The ships were fitted with two submerged 24.5-inch (622 mm) torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, one on each broadside, angled 10° off the centreline.

The ''Nelson''s were built with two director-control towers fitted with

The ''Nelson''s were built with two director-control towers fitted with rangefinder

A rangefinder (also rangefinding telemeter, depending on the context) is a device used to Length measurement, measure distances to remote objects. Originally optical devices used in surveying, they soon found applications in other fields, suc ...

s to control the main guns. One was mounted above the bridge

A bridge is a structure built to Span (engineering), span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or railway) without blocking the path underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, whi ...

and the other was at the aft end of the superstructure. Each turret was also fitted with a rangefinder. A back-up director for the main armament was positioned on the roof of the conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armoured, from which an officer in charge can conn (nautical), conn (conduct or control) the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for t ...

in an armoured hood. The secondary armament was controlled by four directors equipped with rangefinders. One pair were mounted on each side of the main director on the bridge roof and the others were abreast the aft main director. The anti-aircraft directors were situated on a tower abaft the main-armament director with a 12-foot high-angle rangefinder in the middle of the tower. A pair of torpedo-control directors with 15-foot rangefinders were positioned abreast the funnel

A funnel is a tube or pipe that is wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, used for guiding liquid or powder into a small opening.

Funnels are usually made of stainless steel, aluminium, glass, or plastic. The material used in its constructi ...

.

Protection

The ships' waterline belt consisted ofKrupp cemented armour

Krupp armour was a type of steel naval armour used in the construction of capital ships starting shortly before the end of the nineteenth century. It was developed by Germany's Krupp Arms Works in 1893 and quickly replaced Harvey armour as the ...

(KC) that was thick between the main gun barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protection ...

s and thinned to over the engine

An engine or motor is a machine designed to convert one or more forms of energy into mechanical energy.

Available energy sources include potential energy (e.g. energy of the Earth's gravitational field as exploited in hydroelectric power ge ...

and boiler rooms as well as the six-inch magazines

A magazine is a periodical literature, periodical publication, print or digital, produced on a regular schedule, that contains any of a variety of subject-oriented textual and visual content (media), content forms. Magazines are generally fin ...

, but did not reach either the bow or the stern. To improve its ability to deflect plunging fire

Plunging fire is a form of indirect fire, where gunfire is fired at a trajectory to make it fall on its target from above. It is normal at the high trajectories used to attain long range, and can be used deliberately to attack a target not susce ...

, its upper edge was inclined 18° outward. The ends of the armoured citadel were closed off by transverse bulkheads of non-cemented armour thick at the forward end and thick at the aft end. The faces of the main-gun turrets were protected by 16-inch of KC armour while the turret sides were thick and the roof armour plates measured in thickness. The KC armour of the barbettes ranged in thickness from .Raven & Roberts, pp. 114, 123

The top of the armoured citadel of the ''Nelson''-class ships was protected by an armoured deck that rested on the top of the belt armour. Its non-cemented armour plates ranged in thickness from over the main-gun magazines to over the propulsion machinery spaces and the secondary magazines. Aft of the citadel was an armoured deck thick at the level of the lower edge of the belt armour that extended almost to the end of the

The top of the armoured citadel of the ''Nelson''-class ships was protected by an armoured deck that rested on the top of the belt armour. Its non-cemented armour plates ranged in thickness from over the main-gun magazines to over the propulsion machinery spaces and the secondary magazines. Aft of the citadel was an armoured deck thick at the level of the lower edge of the belt armour that extended almost to the end of the stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. O ...

to cover the steering gear. The conning tower's KC armour was thick with a roof. The secondary-gun turrets were protected by of non-cemented armour.

Underwater protection for the ''Nelson''s was provided by a double bottom

A double hull is a ship hull design and construction method where the bottom and sides of the ship have two complete layers of watertight hull surface: one outer layer forming the normal hull of the ship, and a second inner hull which is some di ...

deep and a torpedo protection system. It consisted of an empty outer watertight compartment

A compartment is a portion of the space within a ship defined vertically between Deck (ship), decks and horizontally between Bulkhead (partition), bulkheads. It is analogous to a room within a building, and may provide watertight subdivision of the ...

and an inner water-filled compartment. They had a total depth of and were backed by a torpedo bulkhead

A torpedo bulkhead is a type of naval armor common on the more heavily armored warships, especially battleships and battlecruisers of the early 20th century. It is designed to keep the ship afloat even if the hull is struck underneath the belt ...

1.5 inches thick.

Modifications

The high-angle directors and rangefinder and their platform were replaced by a new circular platform for theHigh Angle Control System

High Angle Control System (HACS) was a British anti-aircraft fire-control system employed by the Royal Navy from 1931 and used widely during World War II. HACS calculated the necessary Deflection (ballistics), deflection required to place an ex ...

(HACS) Mk I director in May–June 1930. By March 1934, the single two-pounder guns and the starboard torpedo director were removed and replaced by a single octuple two-pounder "pom-pom" mount on the starboard

Port and starboard are Glossary of nautical terms (M-Z), nautical terms for watercraft and spacecraft, referring respectively to the left and right sides of the vessel, when aboard and facing the Bow (watercraft), bow (front).

Vessels with bil ...

side of the funnel. It was provided with a Mk I director mounted on the bridge roof. In 1934–1935, ''Nelson'' was fitted with a pair of quadruple mounts for Vickers anti-aircraft machine guns that were positioned on the forward superstructure. The ship was also fitted with a crane to handle a Supermarine Seagull biplane

A biplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with two main wings stacked one above the other. The first powered, controlled aeroplane to fly, the Wright Flyer, used a biplane wing arrangement, as did many aircraft in the early years of aviation. While ...

amphibian aircraft

An amphibious aircraft, or amphibian, is an aircraft that can take off and land on both solid ground and water. These aircraft are typically fixed-wing, though amphibious helicopters do exist as well. Fixed-wing amphibious aircraft are seap ...

carried for test purposes; the crane was retained after the end of the trials. Sometime in 1936–1937, she received her portside "pom-pom" and its director. In addition gun shield

A U.S. Marine manning an M240 machine gun equipped with a gun shield

A gun shield is a flat (or sometimes curved) piece of armor designed to be mounted on a crew-served weapon such as a machine gun, automatic grenade launcher, or artillery pie ...

s were fitted to the 4.7-inch guns although they were removed by March 1938. During her refit from June 1937 to January 1938, ''Nelson'' had her high-angle director tower reinforced and enlarged to accommodate a pair of HACS Mk III directors and new non-cemented deck armour was installed. Like the aft deck armour, it was at the level of the bottom of the armour belt, and extended forward from the front of the citadel almost to the bow; ranging in thickness from close to the citadel to near the bow.

While under repair from January–August 1940 after being mined in December 1939, ''Nelson'' had her aft 6-inch directors replaced by a pair of octuple 2-pounder "pom-pom" mounts and another was added on the quarterdeck

The quarterdeck is a raised deck behind the main mast of a sailing ship. Traditionally it was where the captain commanded his vessel and where the ship's colours were kept. This led to its use as the main ceremonial and reception area on bo ...

. She was also fitted with a Type 279 early-warning radar

An early-warning radar is any radar system used primarily for the long-range detection of its targets, i.e., allowing defences to be alerted as ''early'' as possible before the intruder reaches its target, giving the air defences the maximum tim ...

. Gun shields were reinstalled on the 4.7-inch guns and a pair of four 20-tube UP rocket launchers were mounted on the roofs of 'B' and 'C' turrets. These changes increased the size of her crew to 1,452.

During her repairs after being torpedoed in October 1941, ''Nelson'' had her torpedo tubes and UP rocket launchers removed and an octuple 2-pounder "pom-pom" mount was installed on the roof of 'B' turret. A pair of Oerlikon AA guns were installed on the roof of 'C' turret and eleven more were mounted in various places on the superstructure; all of which were in single mounts. The existing "pom-pom" directors were replaced by Mk III models and three additional directors were fitted. Each of these directors was equipped with a Type 282 gunnery radar. The HACS directors received Type 285 gunnery radars while the forward main-armament director was fitted with a Type 284 gunnery radar. The ship was also equipped with a Type 273 surface-search radar

This is a list of different types of radar.

Detection and search radars

Search radars scan great volumes of space with pulses of short radio waves. They typically scan the volume two to four times a minute. The radio waves are usually less than a ...

and four Type 283 radars for using the 16- and 6-inch guns in barrage (anti-aircraft) fire. Another Oerlikon gun was added to the roof of 'C' turret during a refit in September–October 1942. The 0.5-inch Vickers machine guns were removed and 26 single Oerlikon guns were added in May–June 1943; five of which were on the roof of 'C' turret and the other were mounted on the deck and the superstructure.

While refitting in the United States in late 1944 to prepare her for operations in the Pacific Ocean, her anti-aircraft armament was augmented with 21 more Oerlikon guns for a total of 61 weapons. The back-up director and its armoured hood were replaced by a new platform for a pair of quadruple mounts for 40 mm Bofors AA guns; another pair of quadruple mounts were added abaft the funnel. Most of the "pom-pom" directors were replaced by four Mk 51 directors for the Bofors guns. These additions increased the ship's deep displacement to and her crew to 1,631–1,650 men.

Construction and career

''Nelson'', named afterVice-Admiral

Vice admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to lieutenant general and air marshal. A vice admiral is typically senior to a rear admiral and junior to an admiral.

Australia

In the Royal Australian Navy, the rank of vic ...

Horatio Nelson

Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte ( – 21 October 1805) was a Royal Navy officer whose leadership, grasp of strategy and unconventional tactics brought about a number of decisive British naval victories during the French ...

, was the third ship of her name to serve in the Royal Navy. She was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

on 28 December 1922 as part of the 1922 Naval Programme at Armstrong Whitworth

Sir W G Armstrong Whitworth & Co Ltd was a major British manufacturing company of the early years of the 20th century. With headquarters in Elswick, Tyne and Wear, Elswick, Newcastle upon Tyne, Armstrong Whitworth built armaments, ships, locomot ...

's Low Walker shipyard

A shipyard, also called a dockyard or boatyard, is a place where ships are shipbuilding, built and repaired. These can be yachts, military vessels, cruise liners or other cargo or passenger ships. Compared to shipyards, which are sometimes m ...

in North Tyneside

North Tyneside is a metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of Tyne and Wear, England. It forms part of the greater Tyneside conurbation. North Tyneside Council is headquartered at Cobalt Park, Wallsend.

North Tyneside is bordered by Ne ...

, Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne, or simply Newcastle ( , Received Pronunciation, RP: ), is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. It is England's northernmost metropolitan borough, located o ...

and was launched on 3 September 1925. After completing her preliminary sea trials, she was commissioned on 15 August 1927 at a cost of £7,504,055. The ''Nelson''-class ships received several nicknames: ''Nelsol'' and ''Rodnol'' after the Royal Fleet Auxiliary

The Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) is a naval auxiliary fleet owned by the UK's Ministry of Defence. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service and provides logistical and operational support to the Royal Navy and Royal Marines.

The RF ...

oil tanker

An oil tanker, also known as a petroleum tanker, is a ship designed for the bulk cargo, bulk transport of petroleum, oil or its products. There are two basic types of oil tankers: crude tankers and product tankers. Crude tankers move large quant ...

s with a prominent amidships superstructure and names ending in "ol", ''The Queen's Mansions'' after a resemblance between her superstructure and the Queen Anne's Mansions block of flats

An apartment (American English, Canadian English), flat (British English, Indian English, South African English), tenement ( Scots English), or unit (Australian English) is a self-contained housing unit (a type of residential real estate) th ...

, the ''pair of boots'', the ''ugly sisters'' and the ''Cherry Tree class'' as they were cut down by the Washington Naval Treaty. ''Nelson''s trials resumed after she was formally commissioned and continued in October; the ship entered service on 21 October as the flagship of the Atlantic Fleet (renamed as Home Fleet in March 1932) and remained so, aside from refits or repairs, until 1 April 1941. Prince George, the fourth son of King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

George w ...

and Queen Mary, served aboard her as a lieutenant on the Admiral's staff until his transfer to the light cruiser in 1928. In April 1928, the ship hosted King Amanullah of Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

during exercises off Portland

Portland most commonly refers to:

*Portland, Oregon, the most populous city in the U.S. state of Oregon

*Portland, Maine, the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maine

*Isle of Portland, a tied island in the English Channel

Portland may also r ...

.

On 29 March 1931, she collided with the steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

, of Cardiff

Cardiff (; ) is the capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of Wales. Cardiff had a population of in and forms a Principal areas of Wales, principal area officially known as the City and County of Ca ...

, Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

, in foggy conditions off Cape Gilano, Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, although neither vessel was badly damaged. ''Nelson''s damage was repaired in July. In mid-September, the crew of ''Nelson'' took part in the Invergordon Mutiny when they refused orders to go to sea for an exercise, although they relented after several days when the Admiralty reduced the severity of the pay cuts that prompted the mutiny. On 12 January 1934, she ran aground on Hamilton's Shoal, just off Southsea

Southsea is a seaside resort and a geographic area of Portsmouth, Portsea Island in the ceremonial county of Hampshire, England. Southsea is located 1.8 miles (2.8 km) to the south of Portsmouth's inner city-centre.

Southsea began as a f ...

, as she was about to depart with the Home Fleet for the spring cruise in the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

. After removing some supplies and equipment, the ship floated off during the next high tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ...

, undamaged. The subsequent investigation did not find any of the ship's officers at fault, attributing the incident to her poor handling at low speed. ''Nelson'' participated in King George V's Silver Jubilee Fleet Review in Spithead

Spithead is an eastern area of the Solent and a roadstead for vessels off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast, with the Isle of Wight lying to the south-west. Spithead and the ch ...

on 16 July 1935 and then King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until Death and state funeral of George VI, his death in 1952 ...

's Coronation Fleet Review on 20 May 1937. After a lengthy refit later that year, the ship visited Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

, Portugal, together with her sister in February 1938.

Second World War

When Great Britain declared war on Germany, on 3 September 1939, ''Nelson'' and the bulk of the Home Fleet were unsuccessfully patrolling the waters betweenIceland

Iceland is a Nordic countries, Nordic island country between the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Europe. It is culturally and politically linked with Europe and is the regi ...

, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

and Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

for German blockade runner

A blockade runner is a merchant vessel used for evading a naval blockade of a port or strait. It is usually light and fast, using stealth and speed rather than confronting the blockaders in order to break the blockade. Blockade runners usua ...

s and then did much the same off the Norwegian coast from 6–10 September. On 25–26 September, she helped to cover the salvage and rescue operations of the damaged submarine . A month later, the ship covered an iron ore

Iron ores are rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be economically extracted. The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty red. The iron is usually found in the f ...

convoy from Narvik

() is the third-largest List of municipalities of Norway, municipality in Nordland Counties of Norway, county, Norway, by population. The administrative centre of the municipality is the Narvik (town), town of Narvik. Some of the notable villag ...

, Norway. On 30 October, ''Nelson'' was unsuccessfully attacked by the near the Orkney Islands

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland ...

and was hit by two of the three torpedoes fired at a range of , none of which exploded. After the sinking of the armed merchant cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

off the coast of Iceland on 23 November by the German battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

s and , ''Nelson'' and her sister participated in the futile pursuit of them. On 4 December 1939, she detonated a magnetic mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive weapon placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Similar to anti-personnel and other land mines, and unlike purpose launched naval depth charges, they are deposited and left ...

(laid by ) at the entrance to Loch Ewe on the Scottish coast and was under repair in HM Dockyard, Portsmouth, until August 1940. The mine blew a hole in the hull forward of 'A' turret which flooded the torpedo compartment and some adjacent compartments. The flooding caused a small list

A list is a Set (mathematics), set of discrete items of information collected and set forth in some format for utility, entertainment, or other purposes. A list may be memorialized in any number of ways, including existing only in the mind of t ...

and caused the ship to trim down by the bow. No one was killed, but 74 sailors were wounded.

After returning to service in August, ''Nelson'', ''Rodney'' and the battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of att ...

were transferred from Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay and Hoy. Its sheltered waters have played an impor ...

to Rosyth

Rosyth () is a town and Garden City in Fife, Scotland, on the coast of the Firth of Forth.

Scotland's first Garden city movement, Garden City, Rosyth is part of the Greater Dunfermline Area and is located 3 miles south of Dunfermline city cen ...

, Scotland, in case of invasion. When the signal from the armed merchant cruiser that she was being attacked by the German heavy cruiser

A heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in calibre, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Treat ...

on 5 November was received by the Admiralty, ''Nelson'' and ''Rodney'' were deployed to block the gap between Iceland and the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ) (alt. the Faroes) are an archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. Located between Iceland, Norway, and the United Kingdom, the islands have a populat ...

, although ''Admiral Scheer'' headed for the South Atlantic afterwards. When the Admiralty learned that ''Gneisenau'' and ''Scharnhorst'' were attempting to break out into the North Atlantic to resume commerce raiding operations, ''Nelson'', ''Rodney'' and the battlecruiser were ordered on 25 January 1941 to assume a position south of Iceland where they could intercept them. After spotting a pair of British cruisers on 28 January, the German ships turned away and were not pursued.

''Nelson'' became a private ship on 1 AprilBurt, p. 381 and she was detached to escort Convoy WS.7 from the UK to South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

, visiting Freetown

Freetown () is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, e ...

, Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

, on the 4th. On the return voyage, she and the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

passed the at a range of during the night of 18 May in the South Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for ...

without spotting the German ship. After the Battle of the Denmark Strait

The Battle of the Denmark Strait was a naval engagement in the Second World War, which took place on 24 May 1941 between ships of the Royal Navy and the ''Kriegsmarine''. The British battleship and the battlecruiser fought the German battlesh ...

on 24 May, the was spotted two days later heading for France and ''Nelson'' and ''Eagle'' were ordered to join the pursuit from their position north of Freetown. ''Bismarck'' was sunk the following day well before ''Nelson'' and her consort could reach her. On 1 June, the battleship was assigned to escort Convoy SL.75 to the UK. After the German supply ship ''Gonzenheim'' was able to evade the armed merchant cruiser on 4 June, ''Nelson'' was detached to intercept the German ship, which was scuttled

Scuttling is the act of deliberately sinking a ship by allowing water to flow into the hull, typically by its crew opening holes in its hull.

Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vesse ...

by her crew when they spotted ''Nelson'' approaching later that day. After arriving in the UK, the ship rejoined the Home Fleet.

Mediterranean service

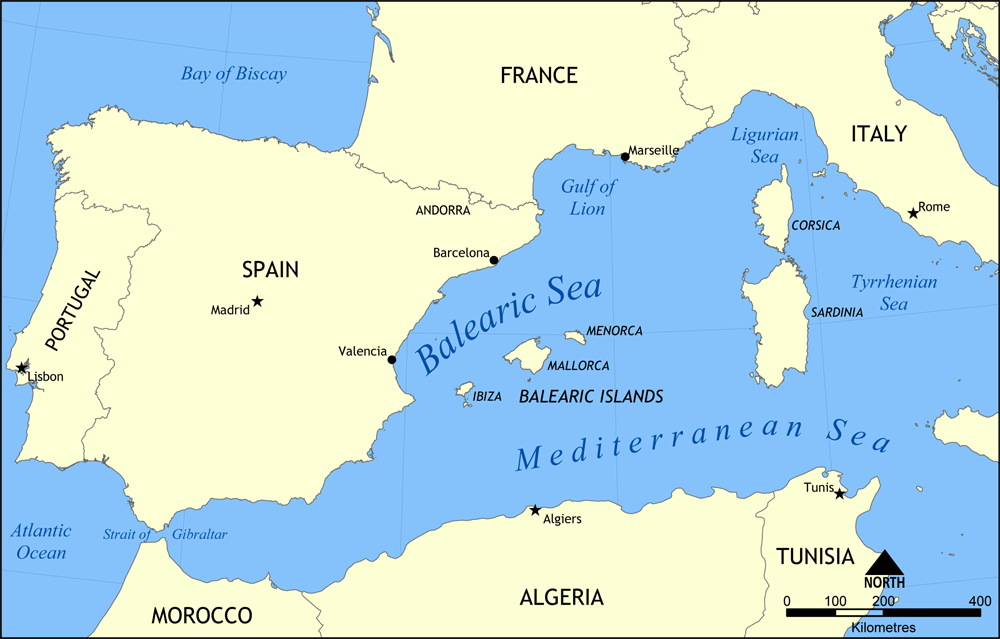

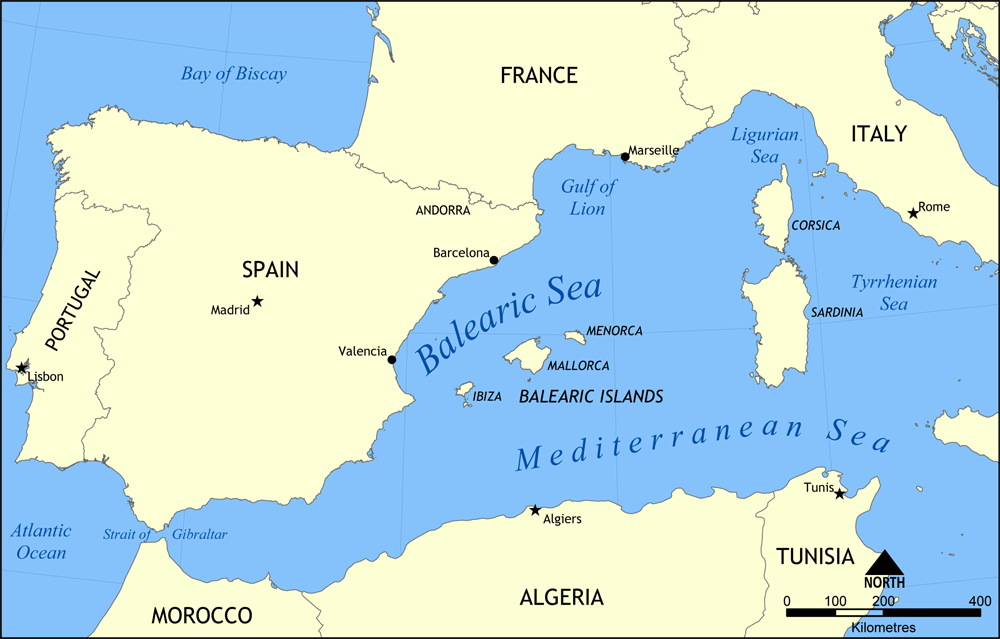

On 11 July, the ship was assigned to escort Convoy WS.9C that consisted of merchantmen that were to pass into the Mediterranean to deliver troops and supplies to Malta. Once they passed

On 11 July, the ship was assigned to escort Convoy WS.9C that consisted of merchantmen that were to pass into the Mediterranean to deliver troops and supplies to Malta. Once they passed Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

, the escorts were designated as Force X and they were to be reinforced by Force H while in the Western Mediterranean. The ships entered the Mediterranean on the night of 20/21 July and they were attacked by Italian aircraft beginning on the morning of the 23rd. ''Nelson'' was not engaged and joined Force H later that day as the merchantmen and their escort continued onwards to Malta. The cruisers from Force X rejoined them two days later and the combined force arrived back in Gibraltar on 27 July. On 31 July–4 August, Force H provided distant cover to another convoy to Malta (Operation Style). Vice-Admiral James Somerville, commander of Force H, transferred his flag to ''Nelson'' on 8 August. Several weeks later, the ship participated in Operation Mincemeat, during which Force H escorted a minelayer

A minelayer is any warship, submarine, military aircraft or land vehicle deploying explosive mines. Since World War I the term "minelayer" refers specifically to a naval ship used for deploying naval mines. "Mine planting" was the term for ins ...

to Livorno

Livorno () is a port city on the Ligurian Sea on the western coast of the Tuscany region of Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Livorno, having a population of 152,916 residents as of 2025. It is traditionally known in English as Leghorn ...

to lay its mines while s aircraft attacked Northern Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

as a diversion. On 13 September, Force H escorted ''Ark Royal'' and the aircraft carrier into the Western Mediterranean as they flew off 45 Hawker Hurricane

The Hawker Hurricane is a British single-seat fighter aircraft of the 1930s–40s which was designed and predominantly built by Hawker Aircraft Ltd. for service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was overshadowed in the public consciousness by ...

fighters to Malta.

As part of a deception operation when Operation Halberd, another mission to convey troops and supplies to Malta, began on 24 September, Somerville's flag was transferred to ''Rodney'' while ''Nelson'' and some escorting destroyers departed Gibraltar heading westwards as if the former ship had relieved the latter. ''Rodney'' and the rest of Force H headed eastwards with ''Nelson'' and her escorts joining the main body during the night. The British were spotted the following morning and attacked by (Royal Italian Air Force) aircraft the next day. A Savoia-Marchetti SM.84 torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the World War I, First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carryin ...

penetrated the screen and dropped a torpedo at a range of . It blew a hole in the bow, wrecked the torpedo compartment and caused extensive flooding; there were no casualties amongst the crew. Although she was down at the bow by and ultimately limited to a speed of to reduce the pressure on her bulkheads, ''Nelson'' remained with the fleet to so that the Italians would not know that she had been damaged. After emergency repairs were made in Gibraltar, the ship proceeded to Rosyth where she was under repair until May 1942.

''Nelson'' was assigned to the Eastern Fleet

Eastern or Easterns may refer to:

Transportation

Airlines

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

* Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 192 ...

after she finished working up and departed 31 May, escorting Convoy WS.19P from the Clyde to Freetown and its continuation WS.19PF to Durban

Durban ( ; , from meaning "bay, lagoon") is the third-most populous city in South Africa, after Johannesburg and Cape Town, and the largest city in the Provinces of South Africa, province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Situated on the east coast of South ...

, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

, en route. She was recalled on 26 June to participate in Operation Pedestal

Operation Pedestal (, Battle of mid-August), known in Malta as (), was a British operation to carry supplies to the island of Malta in August 1942, during the Second World War. British ships, submarines and aircraft from Malta attacked Axis p ...

, a major effort to resupply Malta. Reaching Scapa Flow exactly a month later, she became the flagship of Vice-Admiral Edward Syfret, commander of the operation, the following day. The convoy departed the Clyde on 3 August and conducted training before passing through the Strait of Gibraltar on the night of 9/10 August. The convoy was spotted later that morning and the Axis attacks began the following day with the sinking of ''Eagle'' by a German submarine. Despite repeated attacks by Axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

aircraft and submarines, ''Nelson'' was not damaged and made no claims to have shot down any aircraft before the convoy's capital ship

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they are generally the larger ships when compared to other warships in their respective fleet. A capital ship is generally a leading or a primary ship in a naval fleet.

Strategic i ...

s turned back before reaching the Skerki Banks between Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

and Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

late in the day on the 12th. The ship returned to Scapa Flow afterwards.

She was transferred to Force H in October to support Operation Torch, departing on the 30th and she arrived in Gibraltar on 6 November. Two days later, Force H provided cover against any interference by the for the invading forces in the Mediterranean as they began their landings. Syfret, now commander of Force H, hoisted his flag aboard ''Nelson'' on 15 November. Force H covered a troop convoy from Gibraltar to Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

, French Algeria, in January 1943. Syfret temporarily transferred his flag to the battleship in May as ''Nelson'' returned to Scapa Flow to train for Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily. The ship departed Scapa on 17 June and arrived at Gibraltar on the 23rd.

1943–1949

On 9 July, Force H, with ''Nelson'', ''Rodney'' and the carrier , rendezvoused in theGulf of Sirte

The Gulf of Sidra (), also known as the Gulf of Sirte (), is a body of water in the Mediterranean Sea on the northern coast of Libya, named after the oil port of Sidra or the city of Sirte. It was also historically known as the Great Sirte or G ...

with the battleships , and the carrier coming from Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, Egypt to form the covering force for the invasion. The following day, they began patrolling in the Ionian Sea

The Ionian Sea (, ; or , ; , ) is an elongated bay of the Mediterranean Sea. It is connected to the Adriatic Sea to the north, and is bounded by Southern Italy, including Basilicata, Calabria, Sicily, and the Salento peninsula to the west, ...

to deter any attempt by the to interfere with the landings in Sicily. On 31 August, ''Nelson'' and ''Rodney'' bombarded coastal artillery

Coastal artillery is the branch of the armed forces concerned with operating anti-ship artillery or fixed gun batteries in coastal fortifications.

From the Middle Ages until World War II, coastal artillery and naval artillery in the form of ...

positions between Reggio Calabria

Reggio di Calabria (; ), commonly and officially referred to as Reggio Calabria, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, is the List of cities in Italy, largest city in Calabria as well as the seat of the Metropolitan City of Reggio Calabria. As ...

and Pessaro in preparation for Operation Baytown, the amphibious invasion of Calabria

Calabria is a Regions of Italy, region in Southern Italy. It is a peninsula bordered by the region Basilicata to the north, the Ionian Sea to the east, the Strait of Messina to the southwest, which separates it from Sicily, and the Tyrrhenian S ...

, Italy. The sisters covered the amphibious landings at Salerno

Salerno (, ; ; ) is an ancient city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Campania, southwestern Italy, and is the capital of the namesake province, being the second largest city in the region by number of inhabitants, after Naples. It is located ...

(Operation Avalanche) on 9 September with ''Nelson'' using her main guns in "barrage" mode to deter attacking German torpedo bombers. The Italian surrender was signed between General Dwight Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

and Marshal Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino ( , ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regim ...

aboard the ship on 29 September.

''Nelson'' departed Gibraltar on 31 October for England to rejoin the Home Fleet. She provided naval gunfire support during the Normandy landings in June 1944, but was badly damaged after hitting two mines on the 18th. Temporarily repaired in Portsmouth, the ship was sent to the

''Nelson'' departed Gibraltar on 31 October for England to rejoin the Home Fleet. She provided naval gunfire support during the Normandy landings in June 1944, but was badly damaged after hitting two mines on the 18th. Temporarily repaired in Portsmouth, the ship was sent to the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard

The Philadelphia Naval Shipyard was the first United States Navy shipyard and was historically important for nearly two centuries.

Construction of the original Philadelphia Naval Shipyard began during the American Revolution in 1776 at Front ...

in the United States on 22 June for repairs. She returned to Britain in January 1945 and was then assigned to the Eastern Fleet, arriving in Colombo

Colombo, ( ; , ; , ), is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. The Colombo metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of 5.6 million, and 752,993 within the municipal limits. It is the ...

, Ceylon

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

, on 9 July. The ship became the fleet flagship three days later. ''Nelson'' was used on the western coast of the Malayan Peninsula

The Malay Peninsula is located in Mainland Southeast Asia. The landmass runs approximately north–south, and at its terminus, it is the southernmost point of the Asian continental mainland. The area contains Peninsular Malaysia, Southern Tha ...

for three months, taking part in Operation Livery. The Japanese forces there formally surrendered aboard her at George Town, Penang

George Town is the capital of the States and federal territories of Malaysia, Malaysian state of Penang. It is the core city of the George Town Conurbation, Malaysia's List of cities and towns in Malaysia by population#Largest metropolitan are ...

, on 2 September 1945. Ten days later, the ship was present when the Japanese forces in all of South-east Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Australian mainland, which is part of Oceania. Southeast Asia i ...

surrendered in Singapore.

''Nelson'' was relieved as flagship on 20 September and departed for home on 13 October. She arrived at Portsmouth on 17 November and became the flagship of the Home Fleet a week later. ''King George V'' replaced her as flagship on 9 April 1946 and ''Nelson'' became a training ship in July. When the Training Squadron was formed on 14 August, the ship became flagship of the Rear-Admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

that commanded the training battleships. She was relieved as flagship by the battleship in October and became a private ship. ''Nelson'' was slightly damaged by a collision with the submarine in Portland on 15 April 1947. The ship was placed in reserve on 20 October 1947 at Rosyth and was listed for disposal on 19 May 1948. From 4 June to 23 September, she was used as a target ship for armour-piercing aerial bomb

An aerial bomb is a type of Explosive weapon, explosive or Incendiary device, incendiary weapon intended to travel through the Atmosphere of Earth, air on a predictable trajectory. Engineers usually develop such bombs to be dropped from an aircra ...

s to evaluate their ability to penetrate the ship's armoured deck. ''Nelson'' was turned over to the British Iron & Steel Corporation on 5 January 1949 and was allocated to Thos. W. Ward

Thos. W. Ward Ltd was a Sheffield, Yorkshire, business primarily working steel, engineering and cement. It began as coal and coke merchants. It expanded into recycling metal for Sheffield's steel industry, and then the supply and manufacture ...

for scrapping. The ship arrived at Inverkeithing

Inverkeithing ( ; ) is a coastal town, parish and historic Royal burgh in Fife, Scotland. The town lies on the north shore of the Firth of Forth, northwest of Edinburgh city centre and south of Dunfermline.

A town of ancient origin, Inverke ...

on 15 March to begin demolition.Burt, pp. 377–382

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Maritimequest HMS Nelson Photo Gallery

{{DEFAULTSORT:Nelson (28) Nelson-class battleships Ships built by Armstrong Whitworth Ships built on the River Tyne 1925 ships World War II battleships of the United Kingdom Maritime incidents in 1934